Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solid Waste Classification

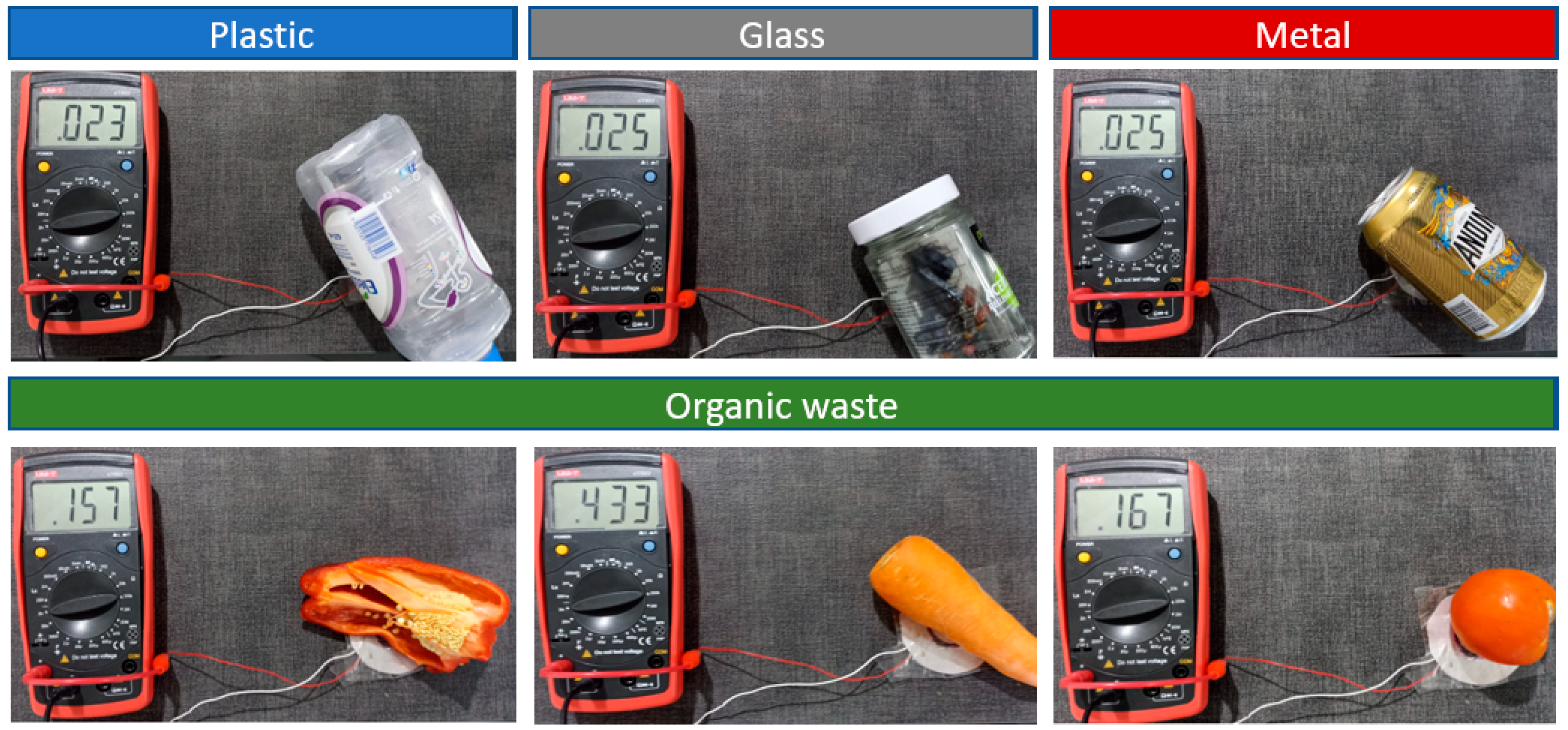

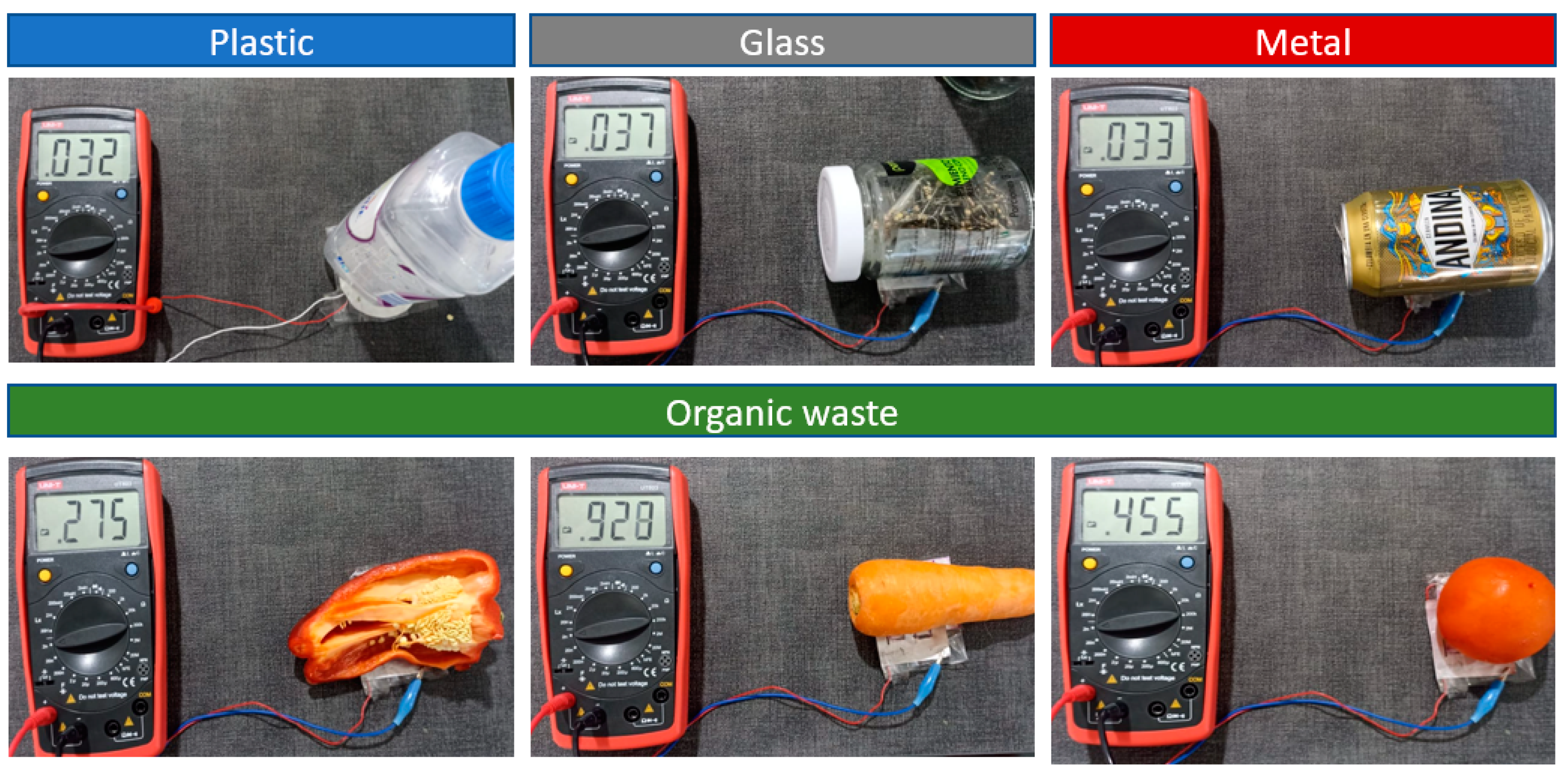

2.2. Sensors

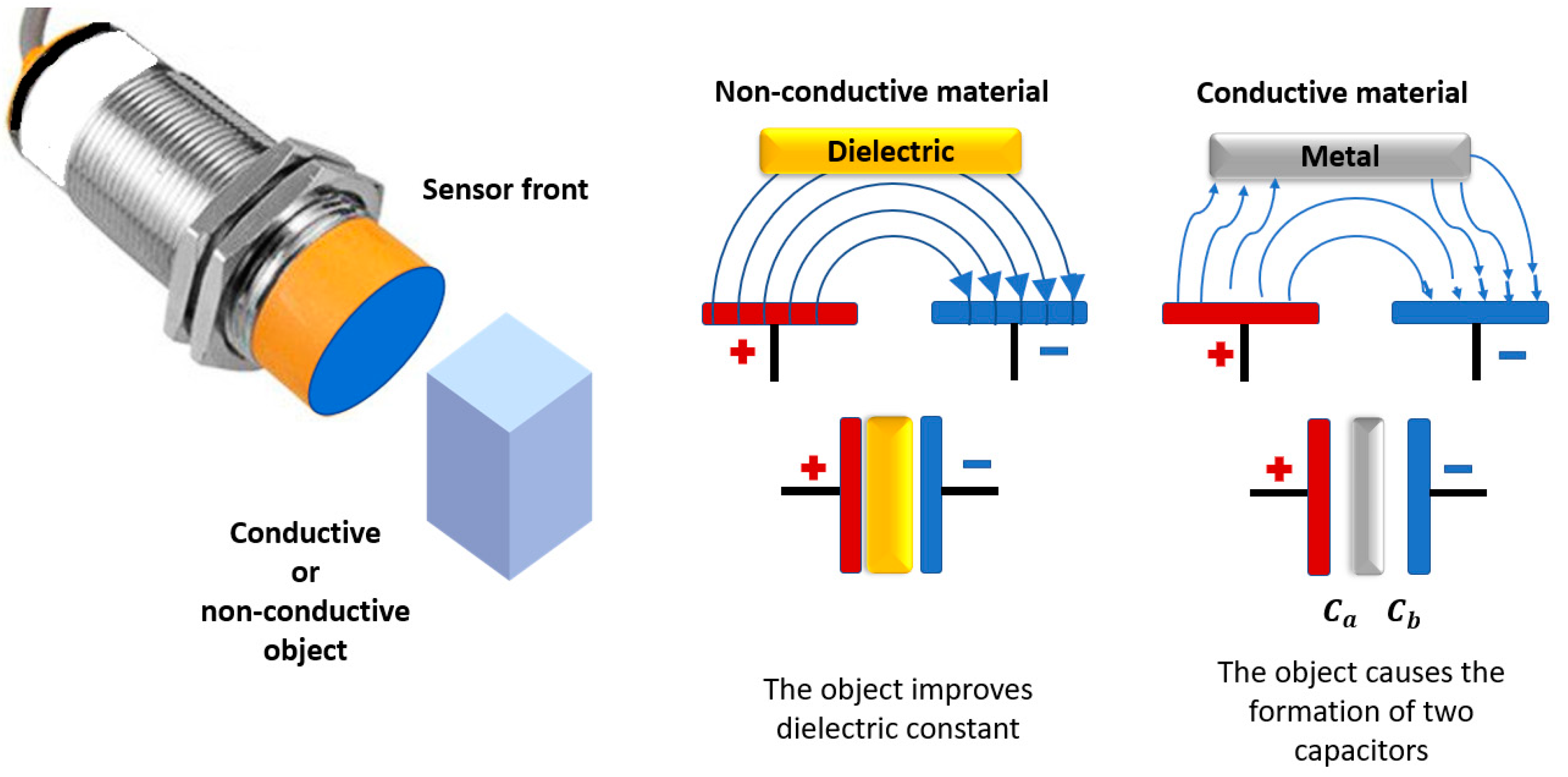

2.3. Capacitive Sensor

2.4. Design of the Proposed Capacitive Sensors

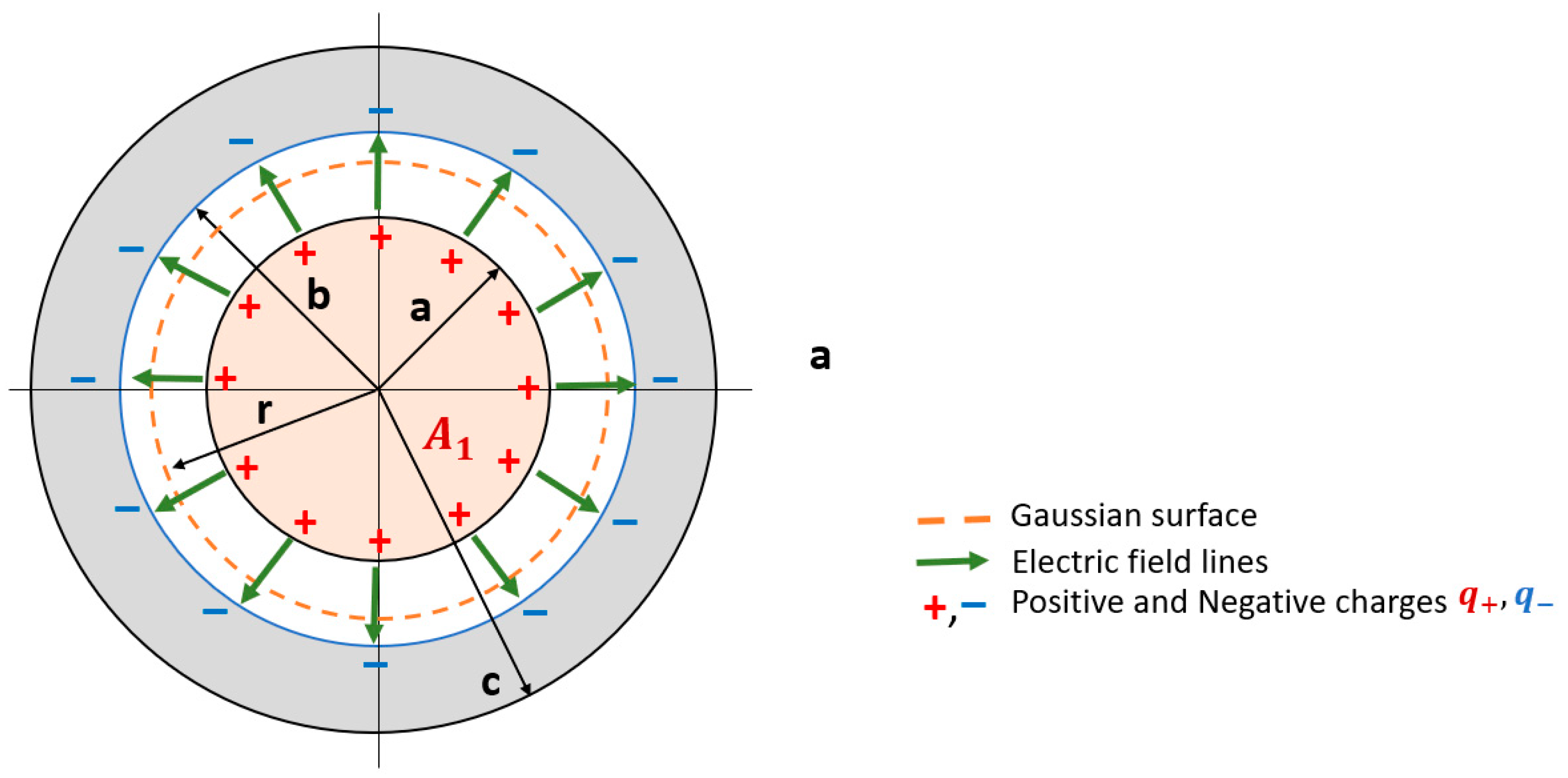

2.4.1. Sensor Design MT

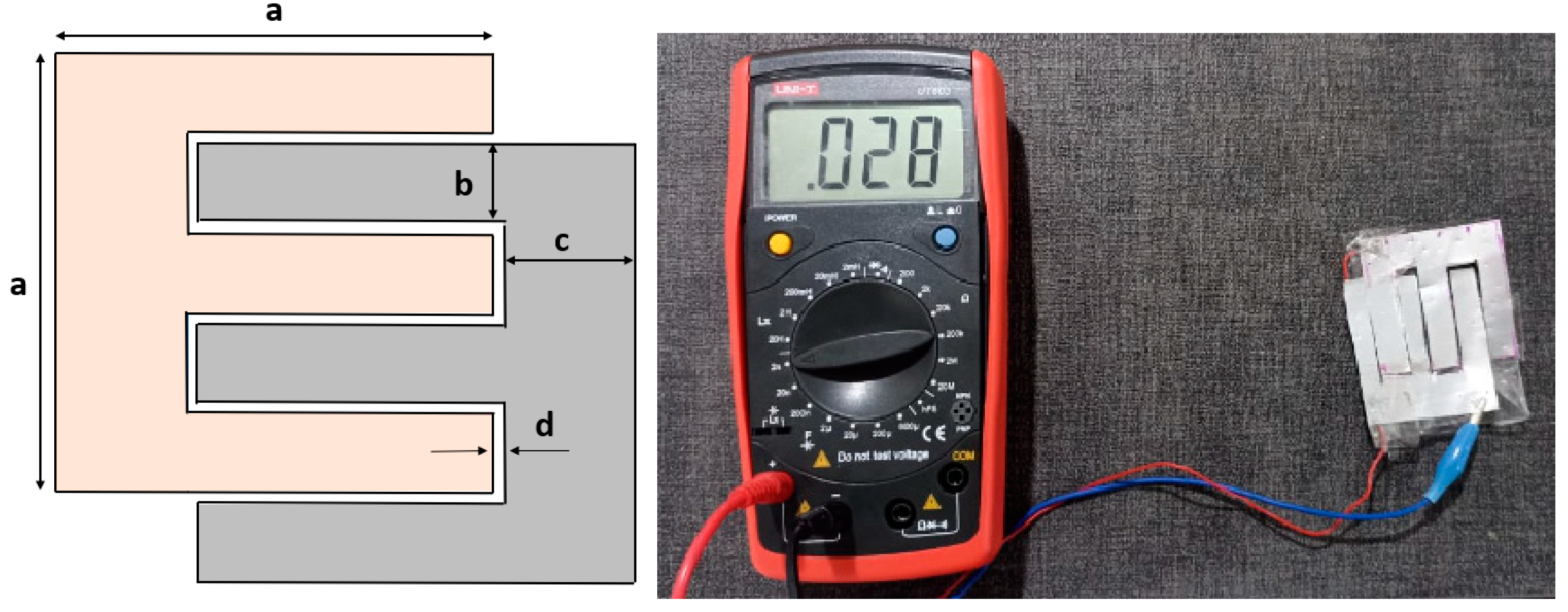

2.4.2. MNT Sensor Design

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Capacitance for MT and MNT Sensors

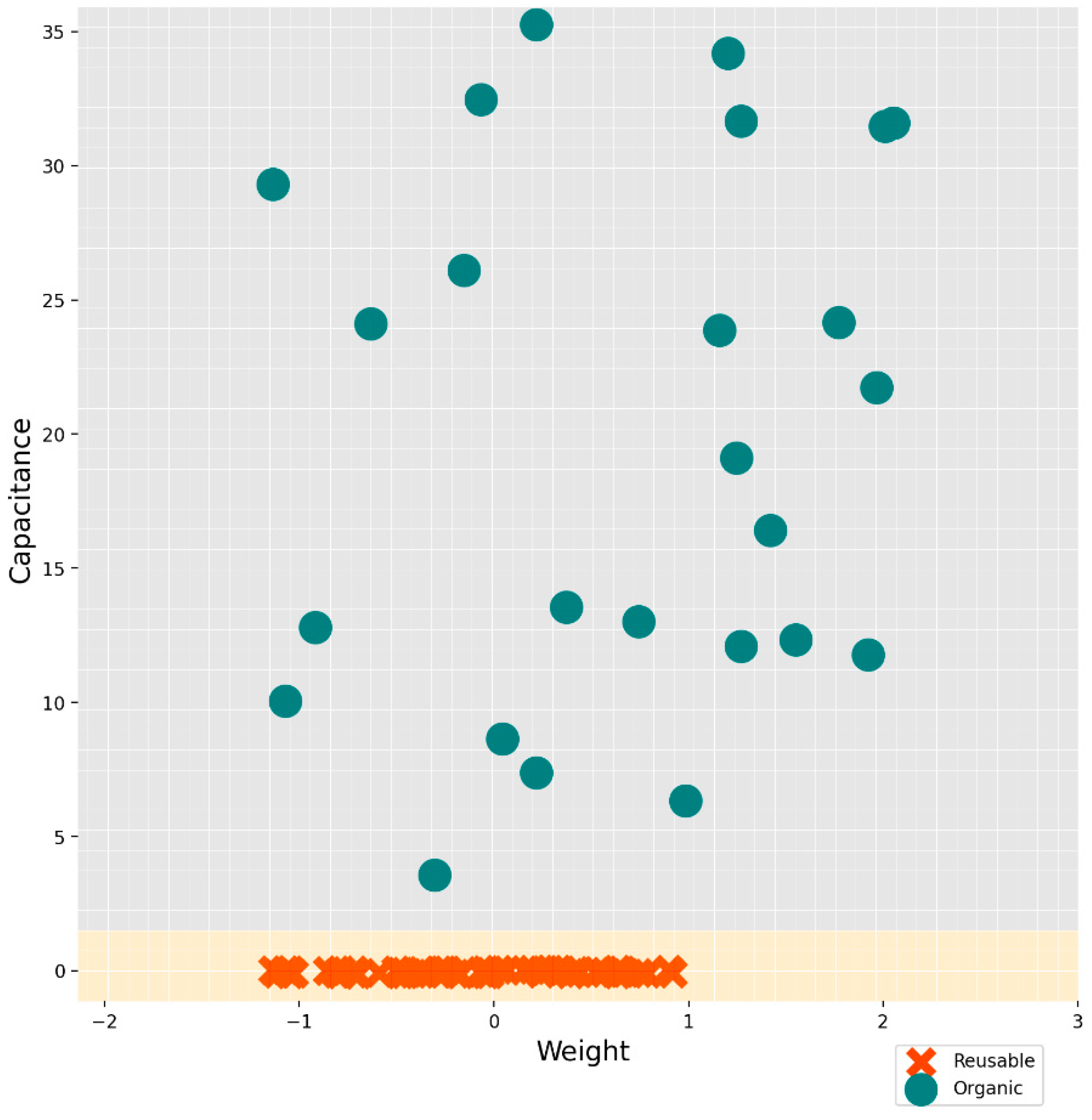

3.2. Estimation of the Number of Samples and Analysis of the Information

| Material | Capacitance [pF] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Confidence interval (95%) | |

| Plastic | 24.680 | 1.519 | (24.084, 25.275) |

| Glass | 25.080 | 1.394 | (24.538, 25.622) |

| Metal | 25.120 | 1.394 | (24.573, 25.666) |

| Organic | 251.120 | 120.823 | (203.757, 298.482) |

| Material | Capacitance [pF] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Confidence interval (95%) | |

| Plastic | 34.680 | 1.574 | (34.063, 35.297) |

| Glass | 34.880 | 1.666 | (34.227, 35.533) |

| Metal | 31.960 | 0.934 | (31.593, 32.326) |

| Organic | 680.960 | 324.396 | (553.799, 808.120) |

3.3. Comparison of MT vs. MNT Treatments

- Step 1: A new random variable is defined and the mean value and standard deviation for the variable are calculated. The result of this process yielded the values of and for and respectively. On the other hand, when defining a new variable Z, it is necessary to make an adjustment in the hypotheses as follows:

- Step 2: We proceed to calculate the value of the statistic established for the test by using the following expression:

- Step 3: Establish the acceptance range of the for at 5% significance (and degrees of freedom. For the particular case, the value of , defining the range of acceptance of the between . When evaluating the value of the d statistic, it is observed that it is within the acceptance interval, which is why is not rejected. In view of the above, it is concluded that the sensor supported in the MNT model is better than the MT sensor for the proposed scenario, with 95% confidence. Additionally, the MNT sensor describes a higher variance (greater response sensitivity, in the presence of different types of materials and even of the same type) compared to the MT sensor, which is very favorable for the identification and classification of waste or materials.

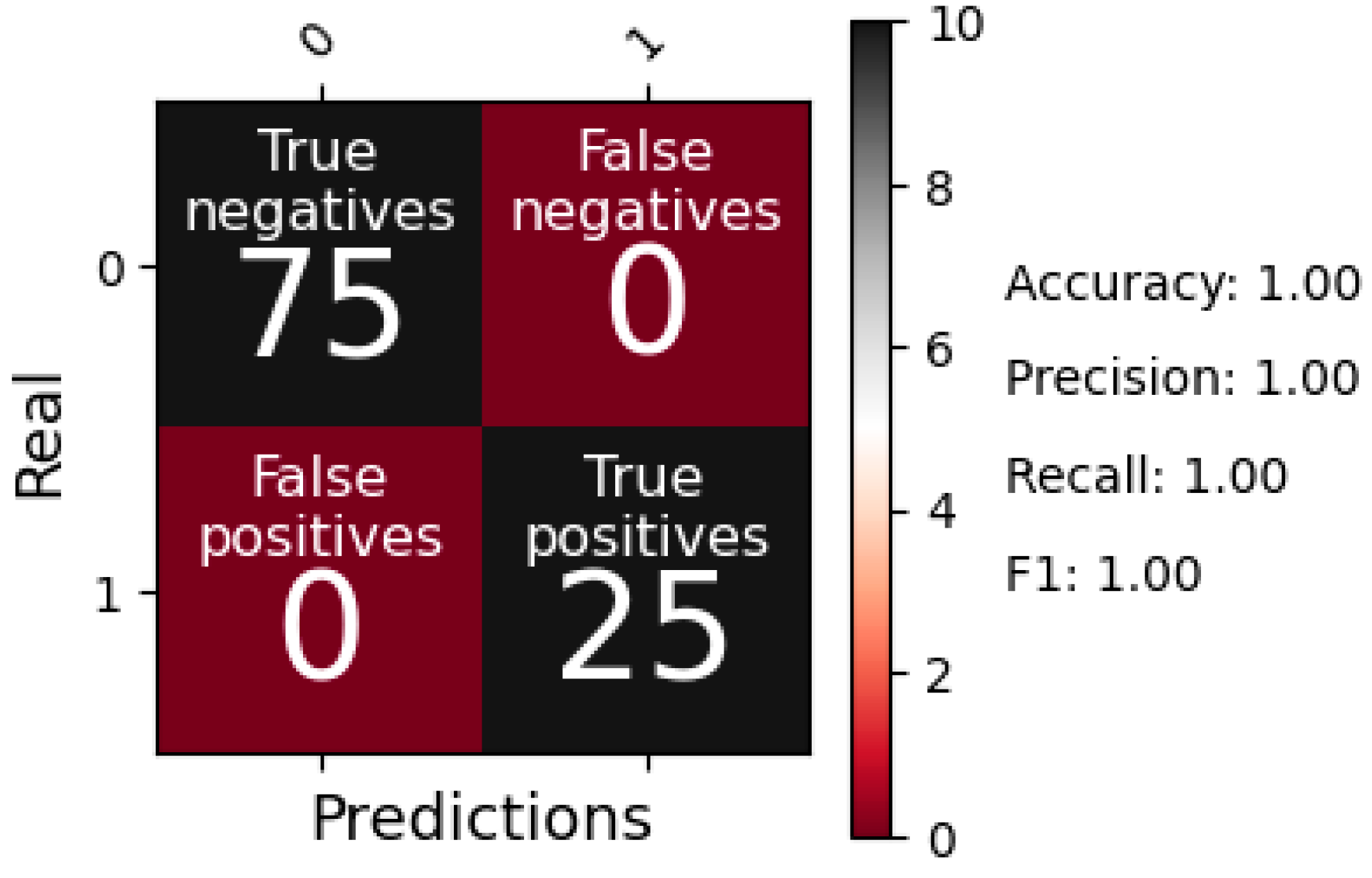

3.4. Classification of Solid Waste with MNT Sensor Using Machine Learning Algorithms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, Z.; Sun, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Microalgae at Variable Mixing Ratios: Enhanced Performance, Kinetic Analysis, and Microbial Community Dynamics Investigation. Appl Sci 2024, Vol 14, Page 4387. 2024;14(11):4387. [CrossRef]

- Gan, B.; Zhang, C. Research on the algorithm of urban waste classification and recycling based on deep learning technology. In: Proceedings - 2020 International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning, CVIDL 2020. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2020:232-236. [CrossRef]

- Kokoulin, A.N.; Uzhakov, A.A.; Tur, A.I. The Automated Sorting Methods Modernization of Municipal Solid Waste Processing System. In: Proceedings - 2020 International Russian Automation Conference, RusAutoCon 2020. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2020:1074-1078. [CrossRef]

- Dadic, B.; Ivankovic, T.; Spelic, K.; Hrenovic, J.; Jurisic, V. Natural Materials as Carriers of Microbial Consortium for Bioaugmentation of Anaerobic Digesters. Appl Sci 2024, Vol 14, Page 6883. 2024;14(16):6883. [CrossRef]

- Colasante, A.; D’Adamo, I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: Emergence of a “sustainability bias.” J Clean Prod. 2021;329. [CrossRef]

- Blumberga, D.; Ozarska, A.; Indzere, Z.; Chen, B.; Lauka, D. Energy, Bioeconomy, Climate Changes and Environment Nexus. 2019;23(3):370-392. [CrossRef]

- Saranya, M. A Survey on Health Monitoring System by using IOT. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2018;6(3):778-782. [CrossRef]

- Dhulekar, P.; Gandhe, S.T.; Mahajan, U.P. Development of Bottle Recycling Machine Using Machine Learning Algorithm. In: 2018 International Conference On Advances in Communication and Computing Technology, ICACCT 2018. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2018:515-519. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. YOLO-Green: A Real-Time Classification and Object Detection Model Optimized for Waste Management. Proc - 2021 IEEE Int Conf Big Data, Big Data 2021. Published online 2021:51-57. [CrossRef]

- Saranya, A.; Bhambri, M.; Ganesan, V. A Cost-Effective Smart E-Bin System for Garbage Management Using Convolutional Neural Network. 2021 Int Conf Syst Comput Autom Networking, ICSCAN 2021. Published online July 30, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, X. Recycling Material Classification using Convolutional Neural Networks. Proc - 21st IEEE Int Conf Mach Learn Appl ICMLA 2022. Published online 2022:83-88. [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.; Ahmed, F.; Das, A.; Dey, A. Classification of Organic and Solid Waste Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Reg 10 Humanit Technol Conf R10-HTC. 2021;2021-September. [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, D.; Ali, S.A.; Jyothi, V.; Chinthapalli, P. Intelligent Waste Segregation Technique Using CNN. 2023 2nd Int Conf Innov Technol INOCON 2023. Published online 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, W.; Shen, S. Garbage classification and environmental monitoring based on internet of things. In: Proceedings of 2018 IEEE 4th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference, ITOEC 2018. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2018:1762-1766. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Jawahar, T. Smart city solid waste management leveraging semantic based collaboration. In: ICCIDS 2017 - International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Data Science, Proceedings. Vol 2018-January. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2018:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Rismiyati; Endah, S.N.; Khadijah; Shiddiq, I.N. Xception Architecture Transfer Learning for Garbage Classification. In: ICICoS 2020 - Proceeding: 4th International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2020:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Vesga Ferreira, J.C.; Sepulveda, F.A.A.; Perez Waltero, H.E. Smart Ecological Points, a Strategy to Face the New Challenges in Solid Waste Management in Colombia. Sustain 2024, Vol 16, Page 5300. 2024;16(13):5300. [CrossRef]

- Vesga, J.C.; Barrera, J.A.; Sierra, J.E. Design of a prototype remote medical monitoring system for measuring blood pressure and glucose measurement. Indian J Sci Technol. 2018;11(22):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Harlacher, B.L.; Stewart, R.W. Common mode voltage measurements comparison for CISPR 22 conducted emissions measurements. In: 2001 IEEE EMC International Symposium. Symposium Record. International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (Cat. No.01CH37161). Vol 1. IEEE; 2001:26-30. [CrossRef]

- Shyam, G.K.; Manvi, S.S.; Bharti, P. Smart waste management using Internet-of-Things (IoT). In: Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Computing and Communications Technologies, ICCCT 2017. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.; 2017:199-203. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, G.P.; Acosta, A.M. Migración de aluminio a los alimentos provenientes de envases y utensilios de cocina nacionales e importados, comercializados en nuestro país. Semin difusión Result del Proy Investig. Published online 2020. Accessed August 18, 2023.

- Cardona, L.; Jiménez, J.; Vanegas, N. Caracterización de materiales empleados en la fabricación de artefactos explosivos improvisados. Rev Colomb Mater. 2014;(5):13-19. [CrossRef]

- Shikha, U.S.; James, R.K.; Pradeep, A.; Baby, S.; Jacob, J. Threshold Voltage Modeling of Negative Capacitance Double Gate TFET. Proc - 2022 35th Int Conf VLSI Des VLSID 2022 - held Concurr with 2022 21st Int Conf Embed Syst ES 2022. Published online 2022:287-291. [CrossRef]

- González Manteiga, M.T.; Pérez de Vargas, A. Estadística Aplicada Una Visión Instrumental. Ediciones Díaz de Santos; 2010. Accessed December 11, 2017. https://books.google.com.co/books?id=8tocMTUkICkC&printsec=frontcover.

- Domínguez, J.; Castaño, E. Diseño de Experimentos - Estrategias y Análisis En Ciencias e Ingeniería. Alfaomega; 2016.

- Walpole, R.; Myers, R.; Myers, S. Probabilidad y Estadística Para Ingeniería y Ciencias. 9th ed. Pearson; 2012.

- Rico Martínez, M.; Vesga Ferreira, J.C.; Carroll Vargas, J.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Toro, A.A.; Cuevas Carrero, W.A. Shapley’s Value as a Resource Optimization Strategy for Digital Radio Transmission over IBOC FM. Appl Sci. 2024;14(7):2704. [CrossRef]

| Plastic Type | |

|---|---|

| Polyethylene | 2.3 |

| Polystyrene | 2.6 |

| Polypropylene | 2.2 a 2.6 |

| PVC | 2.9 |

| Polyethylene Terephthalate PET | 2.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).