Introduction

As we age, the arterial wall progressively stiffens [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Arterial stiffness is a major risk factor for the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and arterial aneurysms or dissections [

4,

5,

6]. The destruction of elastic fibers (EFs) and the elastic lamina (EL, predominantly composed of contracted EFs), along with vascular inflammatory remodeling processes such as fibro-calcification, are critical tissue events contributing to arterial stiffening and endothelial dysfunction [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In healthy elastic arteries, intact elastic fibers create an elastic meshwork that not only provides arterial wall elasticity but also creates a quiescent niche for endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and fibroblasts (FBs), which may help prevent the onset of inflammation [

4,

11,

12,

13].

However, with advancing age, both EFs and EL in the arterial wall undergo post-translational modifications, such as carbamylation and calcification, leading to their eventual degeneration or fragmentation. This process releases elastin-derived peptides (EDPs), which create an inflammatory niche that significantly influences the phenotypes and behaviors of ECs, SMCs, macrophages, FBs, and mast cells [

4,

7,

9,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. The degeneration of EFs and EL, along with the release of EDPs, initiates vascular cellular events such as secretion, migration, proliferation, and calcification through the elastin receptor complex (ERC) [

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These EF/ELs degeneration-associated cellular events are commonly observed in older, stiffened arteries [

2,

11,

24,

25,

26,

27].

These findings suggest that the destruction of the above-mentioned elastic meshwork is a fundamental event underlying arterial inflammation with advancing age. Consequently, preserving intact EFs and blocking EDP/ERC signaling may offer promising therapeutic strategies for slowing age-related arterial remodeling and associated diseases.

Arterial Elastic fibers /Laminae

Elastic Fibers

EFs are a key determinant to the resilience and elasticity of arterial walls [

1,

4,

9,

12,

28]. During the cardiac systolic-diastolic cycle, EFs alternate between stretched and relaxed states approximately 3 billion times over the course of a human lifetime (~70 years). EFs are primarily composed of the protein tropoelastin (TE), encoded by the elastin (ELN) gene, along with its supporting microfibril framework (Figure 1) [

5,

29,

30]. TE, the core protein of EFs, has a half-life of around 70 years, with only 1% of it being renewed per decade [

31]. Intact EFs exhibit a very low Young's modulus (an index of stiffness) ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 MPa and can be stretched linearly to approximately 1.5 times their original length before tearing [

28]. In contrast, collagen fibers have a much higher Young's modulus, around 1 GPa, making arteries approximately 1,000 times stiffer when age-associated collagen fibers replace the elastic fibers [

32]. As a result, arteries become approximately 1,000 times stiffer when collagen fibers predominate, as often seen in older arteries, compared to when elastic fibers are dominant in youth.

Figure 1.

Illustration of assembly and degradation of elastic fibers. Elastic fiber formation and degradation, modified from Kim SH et al [

29] and created with BioRender.com. EBP=elastin binding protein; ECs= Endothelial cells; EDP=elastin derived peptides; ELN=elastin gene; ERC=Elastin receptor complex; FBs=fibroblasts; SMCs=vascular smooth muscle cells; LTBP-1=latent TGF beta-1; NEU-1= membrane-bound neuraminidase Neu-1; PPCA= protective protein cathepsin A; PM=Plasma membrane.

Elastic Laminae

The EL is the predominant compact microstructure of EFs found in elastic arteries, muscular arteries, and some small resistance arteries. The intact meshwork formed by the ELs and EFs imparts elasticity to SMCs, which is crucial for maintaining their structural integrity and functional capacity under healthy, youthful conditions in both rats and humans (Figure 2, left panels; Table 1) [

1,

12,

33]. This elasticity allows arterial cells to efficiently expand and recoil in response to blood pressure fluctuations during the cardiac cycle, ensuring stable and continuous blood flow throughout the body

.

Figure 2.

The meshwork of aortic elastic fibers/laminae. Scanning electronic micrograms of health and degenerated aortic in humans (

A) and rats

(B), which modified from Nakashima Y [

12] and created with BioRender.com. Note: contractile-like SMC encapsulated in the black enclosure with intact EL/EFs (left panels) and synthetic -like cells embedded in destructed EL/EFs (right panels). SMCs=vascular smooth muscle cells.

Two distinct EL layers are recognized: the internal elastic lamina (IEL), which separates the tunica intima from the tunica media, and the external elastic lamina (EEL), which separates the tunica adventitia from the tunica media in large elastic and muscular arteries (Table 1). Clearly defined IEL, ELs, and EEL structures are observed in elastic arteries such as the aorta (Figure 3, left panels), and the IEL is also dominantly present in small muscular arteries, such as epicardial coronary arteries, particular in young rats (Figure 4, left panels) [

34,

35]. In contrast, stiffer type I collagen (as indicated by the increase in yellow & red fibers under polarizing microscope) begin to accumulate, seemingly replacing the lost elastic fibers in older animals (Figure 3 & Figure 4, right lower panels) [

34,

35].

Figure 3.

Age-related large arterial remodeling: Illustration of aortic wall

(A) and the arterial elastic laminae/ fibers (dark blue) were stained via Elastic van Gieson, (left panels) in the large aortic walls of rats which change with age (from 2-months, to 8-months, to 30-months)

(B), adapted from Wang M et al [

34]. Increased collagen deposition with age is demonstrated by collagen that is stained with Picrosirius Red dye showing red color under conventional light microscope (middle panels); and under a polarizing microscope, type I collagen shows red or yellow and type III shows green color (right panels). IEL=Internal elastic laminae; EEL=External elastic laminae.

Figure 4.

Age-related small arterial remodeling. Illustration of wall

(A) and epicardial coronary arteries at 2-months, 8-months, and 30-months of age in rats

(B), adapted from Wang M et al [

35]. Changes in elastic laminae-stained dark blue by Elastic van Gieson; Increased collagen stained with Picrosirius Red dye shows red color under conventional light microscope; and under a polarizing microscope type I collagen shows red or yellow and type III shows green color (right panels). IEL=internal elastic laminae.

Arteries are categorized into two types: elastic arteries and muscular arteries, which differ primarily in the composition of the tunica media. The tunica media of elastic arteries consists predominantly of EFs, while that of muscular arteries is mainly composed of SMCs. Muscular arteries may contain two defined elastic layers within the tunica media: the IEL and EEL, as seen in arteries such as the mesenteric, internal and external carotid, and tibial arteries. The EEL, situated between the collagen fibers/sheets of the adventitia and the muscle layers of the media, is a well-defined structure in elastic and some muscular arteries.

Notably, both the IEL and EEL play crucial roles in preserving the arterial media's structural integrity and function and preventing arterial diseases [

33,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. These elastic layers not only provide mechanical, structural, and functional support to the arterial medial wall but also act as protective barriers for medial SMCs. By limiting these cells' exposure to inflammatory molecules originating from both the intima (inside-out) and the adventitia (outside-in), the IEL and EEL help maintain cellular quiescence [

33,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. This dual role underscores the importance of the IEL and EEL in maintaining normal vascular cell function, promoting vascular health, and potentially preventing vascular diseases.

Arterial Elastic fibers /Elastin Laminae with Aging

Young arteries

Under young and healthy conditions, intact EFs and ELs (Table 1) play critical structural, functional, and physiological roles in the arterial wall. Together with associated elements such as microfibrils and latent transforming growth factor (TGF) binding protein 1 (LTBP-1), these intact EFs and ELs create a quiescent microenvironment that is essential for maintaining the anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic properties of ECs and preserving the contractile phenotype of vascular SMCs within the arterial wall [

13,

19,

28]. Additionally, the intact EFs and ELs provide a stable, resilient, and elastic niche that protects SMCs from injury, thereby supporting arterial homeostasis [

13,

29].

The IEL, primarily generated from both ECs and SMCs, serves a dual function (Table 1) [

39]. First, it acts as a buffer or cushion, orienting both ECs and SMCs to withstand the circumferential and longitudinal strains experienced during the cardiac cycle [

13,

45]. Second, the IEL forms a physical barrier that prevents the migration and invasion of SMCs and monocytes into the intima-media; and mediates direct communication between ECs and SMCs through fenestrations. This barrier function is crucial for preventing endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, intimal thickening, and medial weakening [

13,

39,

40,

42,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

The EEL, primarily produced by SMCs, likely plays a key role in limiting medial expansion and inflammation [

37,

38,

39,

41,

53]. Along with other ELs, the EEL organizes arterial components and prevents excessive arterial wall expansion during the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle [

44,

54,

55]. Additionally, the EEL may restrict the migration and invasion of adventitial fibroblasts, thereby counteracting both medial and intimal thickening [

36,

44,

54,

56,

57].

Furthermore, the EEL may act as a physical barrier that confines adventitial fibroblasts to the adventitia, where they contribute to the production of extracellular matrix (ECM) components and interact with immune cells such as leukocytes, mast cells, and macrophages [

16,

36,

43,

44,

56,

58]. This barrier function may help maintain immune quiescence within the intima and medial wall, preventing the infiltration of immune cells via the adventitial vasa vasorum or lymphatic vessels [

38,

41,

44,

58].

Old arteries

As aging progresses, EFs and ELs undergo erosion and even breakdown, with insufficient repair mechanisms in place to restore them (Figure 2, Table 1, Figure 3 & Figure 4) [

2,

7,

29,

34,

35,

54]. The degradation of the elastic meshwork leads to a loss of elasticity and resilience, resulting in the generation of EDPs and releasing latent transforming growth factor 1 (LTBP-1) (Figure 1). This is a major molecular event that promotes inflammatory remodeling, including cellular phenotypic shifts and extracellular matrix restructuring, such as fibrosis, calcification, and carbamylation, that ultimately contributes to arterial stiffening [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

29].

The degradation of EFs and ELs releases inflammatory EDPs (Table 2), which belong to the matrikine family and are primarily located in the intima and media [

21]. The most typical EDP is a hexapeptide repeat, VGVAPG. Notably, EDPs are potent pro-inflammatory ligands that interact with ECs and SMCs as well as other vascular inflammatory cells by binding to the ECR (Figure 1), an unusual cell surface receptor [

29]. The ECR is a heterotrimeric structure composed of an elastin-binding protein, the membrane-associated protective protein cathepsin A (PPCA), and the membrane-bound neuraminidase Neu-1 (NEU-1) (Figure 1). Notably, ERC activation can be inhibited by galactolatin/galactosugars via induction of EDPs release and dissociation of this complex. Other potential EDP receptors include integrin αvβ3 and galectin-3 in various cell types [

20,

59].

Upon activation by EDPs, the ECR on the plasma membrane of vascular cells triggers alterations in cellular phenotypes, leading to changes such as increased migration, invasion, proliferation, and calcification (Figure 1) [

23,

29]. Of note, these inflammatory phenotypic shifts and microenvironmental changes facilitate the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and arterial aneurysms or dissections [

8,

14,

16,

23,

29,

46]. Additionally, post translational modifications (PTMs), such as the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidation, and calcification, further exacerbate inflammation and stiffening, making the arterial structures more prone to fragility or degeneration [

23,

29,

45,

60,

61,

62].

Effect of Age-Associated Elastic Degeneration on Phenotypic Shifts of Arterial Cells

Aging or disease accelerates the destruction of EF and EL (Figures2 and Table 1). As aging progresses, the arterial wall's intima and media thicken, and the adventitia expands, leading to an increased presence of EDPs in these regions [

21,

53,

63]. The degradation of elastin and the resulting EDPs serve as potent signaling molecules, driving the inflammatory response in various vascular cells, including ECs, SMCs, FBs, macrophages, and mast cells (Table 2). This process contributes to the initiation and progression of age-related vascular remodeling and associated diseases (Table 3; Figure 5).

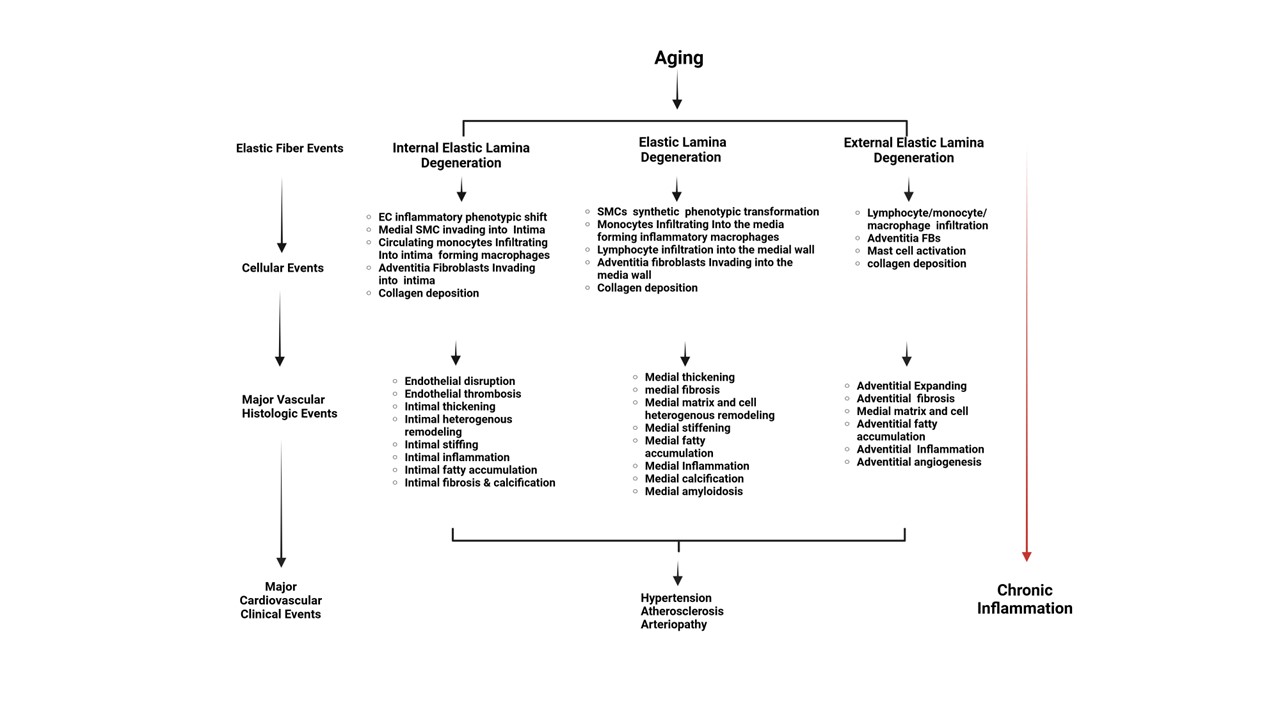

Figure 5.

Cellular, histological, and clinical events derived from EF/EL degeneration in the arterial wall with aging. The schematic representation illustrates the pathophysiological processes involved in vascular aging. It highlights the transition from EF/EL degeneration events to chronic inflammation through various cellular and histologic changes within the arterial wall. Key components include EL degeneration, endothelial and smooth muscle inflammatory phenotypic transformation, monocytes infiltrating into macrophages, fibroblasts, and major vascular histologic events. These changes contribute to chronic inflammation and cardiovascular clinical events. This illustration is created with BioRender.com. EC=endothelial cell; SMC=vascular smooth muscle cells.

Endothelial Cells

Under normal conditions, arterial ECs are positioned over the IEL via a basement membrane [

39]. ECs interact with the IEL, covering its fenestrae, and communicate with medial SMCs and adventitial FBs through direct contact, gap junctions, or paracrine signaling via extracellular vesicles [

13,

40,

52,

64]. These cellular interactions are crucial for maintaining the physiological functions of the endothelium, such as reendothelialization, anti-vasoconstriction, and anti-inflammation, as well as for regulating the contractile state of SMCs. This coordination ensures normal vascular tone and blood pressure, both of which are essential for vascular homeostasis and health [

13,

40,

52,

64].

Conversely, damage to the IEL and the accompanying release of EDPs generate inflammatory signals [

14,

16,

23]. In human aortic ECs, treatment with EDPs triggers the release of proteinases, such as matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) [

18]. Critically, damage to elastin compromises the endothelium's ability to release nitric oxide, a gas molecule that plays a key role in promoting SMC relaxation and exerting anti-inflammatory effects, thereby significantly impacting vascular tone and blood flow [

65]. Additionally, EDPs promote the oxidation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), enhance monocyte adhesion, and contribute to the development of atherosclerosis [

15,

24]. Notably, an intact elastin microstructure is essential for EC adhesion, spreading, and cell cycle entry, which are vital for the active repair of endothelial damage throughout life [

13,

48].

Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

Aging alters the phenotype of SMCs, characterized by a decline in α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and an increase in cellular stiffness, which leads to a higher proliferative capacity in older versus younger SMCs (Figure 6) [

27]. The degeneration of ELs and the release of EDPs significantly influence SMC behavior, including inflammatory responses, extracellular matrix secretion, proliferation, migration, and invasion [

2,

19,

22,

27,

30,

39,

40,

42,

46,

49].

The EDP/ERC signaling promotes the migration and invasion of SMCs into the intima through the enlarged fenestrae of the IEL, primarily due to the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and an increase in the chemoattractant platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-β) [

40]. These molecular and structural changes are crucial in facilitating the migration, invasion, and proliferation of medial SMCs into the intima, ultimately leading to arterial stenosis. Additionally, EDPs induce SMC trans-differentiation into osteo-chondrogenic cells, marked by increased MMP-2 activation, runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), which contribute to calcification and elastin biomineralization [

19,

62,

66].

Fibroblasts

Arterial FBs are a predominant cell type in the tunica adventitia [

67]. Adventitial FBs play a significant role in age-associated adverse remodeling, particularly in adventitial remodeling, which includes senescence, inflammation, and stiffening [

2,

11,

68]. FBs are crucial in responding to the degeneration of EFs and ELs, contributing to the production of senescence markers, oxidative stress, inflammation, and collagen deposition within the arterial wall, especially in the adventitial region [

2,

11,

36,

56,

57,

68]. Additionally, as the EL/EF degenerates, the arterial intima and media thicken and become infiltrated by adventitial FBs, leading to inflammatory changes, increased collagen deposition, and calcification [

36,

57,

69,

70,

71].

Mast Cells

Mast cells are a type of immune cell predominantly found in the arterial adventitia and thickened intima [

43,

72,

73]. These cells have been observed to infiltrate aortic aneurysm lesions through fragmented ELs via chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) [

74]. Both the degradation of EFs and ELs and the presence of mast cells have been implicated in inflammatory responses and arterial remodeling [

43,

72].

Mast cells are activated by various stimuli, including aging, which triggers signaling cascades that lead to the release of inflammatory molecules such as chymase and MMP-2 and MMP-9, as well as chemoattractant molecules like CCR2 [

14,

16,

43,

73]. Upon activation, mast cells release granules containing these substances, which not only promote inflammation but also attract and activate other inflammatory molecules, such as angiotensin II, and other cell types, including macrophages. These processes contribute to further degradation of EFs and ELs in the arterial wall, exacerbating arterial damage and remodeling [

43,

72,

73].

Macrophages

Macrophages are immune cells within the arterial wall that differentiate from circulating monocytes and perform various functions, including phagocytosis of pathogens and cellular debris, regulation of inflammation, tissue repair, and modulation of immune responses. EDPs induce circulating monocytes to adhere to the endothelium, migrate into the subendothelial space, and differentiate into macrophages. These macrophages produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which facilitate the oxidation of LDL [

15,

24].

Resident macrophages are observed in the adventitia of aged arteries [

75]. These adventitial macrophages secrete proteinases such as MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-12, which degrade EFs and ELs, thus releasing EDPs. This process promotes the recruitment of macrophages to sites of infection or injury within the intima, media, or adventitia through the enlarged fenestrations or breaks in the elastic meshwork of arteries [

17,

58].

The life cycle of macrophages, including their inflammatory responses, chemotaxis, and M1/M2 polarization, can be modulated by EDPs, influencing their behavior and function [

14,

16,

17,

55,

57,

76,

77]. At sites of arterial inflammation, macrophages phagocytose foreign particles, debris, and pathogens while releasing cytokines, MMP-2, MMP-9, and other signaling molecules that coordinate and enhance the migration and immune responses of other macrophages [

57,

58].

The degradation of EFs and ELs, the release of EDPs, and the formation of foam cells are critical steps in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis, a condition characterized by the accumulation of fatty deposits and inflammation within the arterial wall [

14,

16,

55]. Foam cells, typically derived from macrophages, are immune cells that have engulfed large amounts of lipids, mainly oxidized LDL cholesterol [

78]. The accumulation of foam cells within arterial plaques contributes to the formation of fatty deposits and the progression of atherosclerotic lesions [

78]. The destruction of EFs and ELs promote atherosclerosis by inducing phenotypic changes in macrophages, making them more prone to foam cell formation [

16,

57,

77]. The formation of foam cells and the release of inflammatory signals from these cells create a pro-inflammatory environment, establishing a feedback loop that sustains the progression of atherosclerosis.

While the exact mechanisms linking elastin degeneration to foam cell formation are still under investigation, studies suggest that changes in macrophage behavior—such as increased infiltration and inflammation within the arterial wall—due to elastin degeneration play a significant role in the processes leading to foam cell formation, arterial stenosis, and atherosclerosis [

14,

16,

55,

57,

60,

76,

77].

Arterial Diseases Associated with Elastic Fiber Degeneration

The reduced elastin production, fragmented ELs/EFs, and loss of elastin are closely associated with several vascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and arteriopathy such as aneurysms or dissections (Figure 5 and Table 3). Impaired endothelial function and weakened vessels become less resistant to pressure, contributing to chronically high blood pressure; fragments damage other arterial components, contributing to foam cell aggregation, plaque buildup and narrowing; and loss of elasticity weakens vessel walls, leading to ballooning and potential rupture. These changes result in vessel stiffening, reducing the ability of arteries to adapt to fluctuations in blood pressure and flow, and lowering the threshold for harmful stimuli such as increased pressure, hyperlipidemia, and hypercalcemia [

4,

6,

8,

12,

14,

15,

41,

43,

47,

55,

60,

63,

74,

77,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. Consequently, the loss of elasticity and the promotion of inflammation are primary risk factors for several other vascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and aneurysms/dissections.

Hypertension

Aging significantly increases the incidence of hypertension, particularly advanced hypertension, and is closely linked to the degeneration of arterial elastin or EFs [

4,

8,

34,

47,

83,

84]. In a mouse model deficient in elastin (Eln-/-), arterial development is comparable to wild-type (WT) mice until approximately day 17.5 of gestation [

85]. Beyond this point, a marked increase in the number of SMCs obstructing the arterial lumen is observed [

85]. Postnatally, the systolic blood pressure (SBP) in Eln-/- mice is double that of WT mice, with a significant increase in arterial stiffness [

85]. At the cellular level, SMCs become disorganized and proliferate abnormally [

85]. The arteries of Eln-/- mice exhibit local dilation and narrowing, leading to early postnatal death, although these abnormalities can be successfully rescued through the introduction of human elastin [

85]. In addition, heterozygous Eln+/- mice exhibit characteristics of hypertension, aortic stenosis, and heart dysfunction [

8,

47,

84].

The bioavailability of TGF-β, modulated by emilin-1, a protein associated with EFs, also influences SBP in mice, suggesting that EF integrity and TGF-β signaling play important roles in hypertension [

5]. In these mice, vascular stiffening is detectable seven days after birth, but hypertension does not manifest until around the 14th day [

5,

83]. These findings suggest that changes in mechanical properties may precede changes in SBP.

An elegant study involving a mouse model expressing human elastin mice produced a spectrum of elastin expression levels ranging from 30% to 100% of normal [

86]. The level of elastin was found to be inversely related to arterial stiffness and SBP [

30,

84,

87]. Eln+/- mice exhibit higher blood pressure (20-30 mmHg more) than their WT counterparts [

47,

86]. These findings further underscore the pivotal role of elastin in the development of hypertension [

54] .

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is an arterial metabolic disorder closely associated with the degeneration of EFs and can be observed under the microscope [

25,

88]. The degradation of EFs and ELs permits the deep infiltration of lipids and immune cells, such as monocytes, into the aortic wall, leading to the formation of macrophage foam cells, activation of MMP-2 and MMP-9, all of which contribute to the formation and disruption of atherosclerotic plaques [

25,

38,

41].

The role of EF degradation in atherosclerosis has been substantiated by animal models, particularly through the crossbreeding of mice deficient in MMP-2 and MMP-9 with atherogenic models (LDLR-/- and ApoE-/-) [

89,

90]. These findings clearly demonstrate that the degradation of EFs and ELs is a prerequisite for the development of atherosclerosis. In LDLR-/- mice fed an atherogenic diet and in obese mice, the degradation of EFs and ELs correlates with the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [

4,

15]. Notably, chronic treatment with EDPs in a mouse model of atherosclerosis has been shown to directly increase the size of atherosclerotic plaques [

15]. Similar effects were observed following the injection of the VGVAPG peptide, suggesting that these effects are mediated by ERC [

15].

Moreover, the absence of phosphoinositide-3-kinase gamma (PI3Kγ) in bone marrow-derived cells prevented EDP-induced atherosclerosis development, demonstrating that PI3Kγ is crucial for EDP-induced arterial lesions [

15].

In vitro studies have shown that PI3Kγ is required for EDP-induced monocyte migration and ROS production, and that this effect is dependent on NEU-1 activity [

15]. Furthermore, the absence of the PPCA-NEU-1 complex in hematopoietic lineage cells abolished the progression of atheroma plaque size and decreased leukocyte infiltration, clearly demonstrating the role of this complex in atherogenesis and suggesting the involvement of endogenous EDPs [

15]. This research identifies EDPs as enhancers of atherogenesis and defines the NEU-1/PI3Kγ signaling pathway as a key mediator of this process both

in vitro and

in vivo [

15].

Arteriopathy

An aneurysm is a bulge or weakened area in the wall of an artery, which can occur in any artery in the body, such as those in the brain, but is most common in the aorta. Dissection occurs when a tear forms within the aortic wall and causes blood to flow between the laminal layers of the media, thereby creating a false lumen. This can further weaken and expand the artery, significantly increasing the risk of rupture. Dissections most commonly occur in the aorta but can also affect other arteries, such as the coronary arteries. Histologically, both aneurysms and dissections are associated with the degeneration or destruction of EFs and ELs, conditions collectively known as elastin arteriopathy [

14,

23,

55,

58,

63,

80,

91].

The EDPs play a significant role in polarizing macrophage-induced inflammation, promoting SMC calcification, and activating matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 within SMCs and the arterial wall [

14,

19]. These activated MMPs are potent elastolytic enzymes that effectively cleave EFs both

ex vivo and

in vivo [

92]. The incidence of aneurysms, along with EF degradation, is markedly reduced in genetic models of MMP-2 and MMP-9 knockout (KO) mice compared to WT models. Furthermore, the use of an antibody targeting the EDP peptide, VGVAPG, significantly reduces aortic MMP-2/-9 activation, EF/EL fragmentation, macrophage infiltration, and TGF-β1 activity, ultimately mitigating the development of aortic aneurysms in this mouse model [

91]. Therefore, preserving the integrity of EFs and ELs is crucial in counteracting age-associated arterial aneurysms and dissections [

55,

60,

65,

80,

82] [

91].

The degradation and cleavage of EFs and ELs can be mitigated through both non-pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical approaches [

55,

60,

65,

80,

82,

93]. Pharmaceutical treatments include compounds such as resveratrol and glucagon-like peptides [

60,

65]. Non-pharmaceutical strategies involve maintaining a healthy diet and regular exercise, which contribute to overall vascular health [

80,

93]. Additionally, pharmaceutical regimens or gene therapy could be developed to enhance EF/EL repair, reduce their degradation, and suppress the inflammatory signaling induced by released EDPs [

55,

60,

65,

82].

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This review highlights the pivotal role of EF and EL degradation in the progression of arterial aging and the subsequent development of various cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and aneurysms (Figure 6). The degradation of EFs and ELs leads to the release of EDPs, which act as potent signaling molecules driving inflammatory responses and adverse vascular remodeling. These molecular and cellular changes contribute to the stiffening of arteries, loss of elasticity, and increased vulnerability to harmful stimuli, ultimately leading to the onset and progression of age-related arterial diseases.

Future research should focus on developing and refining therapeutic strategies that target the molecular mechanisms underlying EF/EL degradation and the associated inflammatory responses. One important avenue for investigation is the development of pharmacological interventions. Specifically, drugs that inhibit EDP production, block ERC signaling, or enhance elastin synthesis and repair are crucial [

15,

29]. Ensuring these compounds' efficacy and safety in preclinical and clinical settings will be essential for translating these findings into effective therapies.

Gene therapies also hold promise for the future, particularly in cases where elastin insufficiency underlies arterial diseases. Advances in gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, could enable the precise correction of genetic defects responsible for impaired elastin production, thus offering a potential avenue for restoring elastin levels in affected individuals [

86].

In addition to pharmacological and gene-based approaches, non-pharmaceutical interventions merit further exploration. In this regard, lifestyle modifications, such as dietary interventions and regular exercise, have been shown to positively impact vascular health [

55,

80]. Fully understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the assembly and disassembly of EL/EFs could help develop optimized lifestyle recommendations for preserving vascular health.

Furthermore, the identification of reliable biomarkers for EF/EL degradation and EDP activity could facilitate early detection of arterial diseases and enable better monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy [

15]. Proteomic and metabolomic approaches may provide valuable insights into the molecular changes associated with elastin degradation.

Finally, while significant progress has been made in understanding elastin degradation's role in arterial aging, more research is needed to elucidate the precise molecular and cellular mechanisms involved [

14,

16,

55,

57,

60,

76,

77]. Understanding the interactions between elastin degradation, inflammation, and vascular remodeling is critical for developing targeted therapies that address the root causes of arterial aging and its associated diseases.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Berquand, A. , et al., Revealing the elasticity of an individual aortic fiber during ageing at nanoscale by in situ atomic force microscopy. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleenor, B.S.; Marshall, K.D.; Durrant, J.R.; Lesniewski, L.A.; Seals, D.R. Arterial stiffening with ageing is associated with transforming growth factor-β1-related changes in adventitial collagen: reversal by aerobic exercise. J. Physiol. 2010, 588 Pt 20, 3971–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, H.K.; Akhtar, R.; Kridiotis, C.; Derby, B.; Kundu, T.; Trafford, A.W.; Sherratt, M.J. Localised micro-mechanical stiffening in the ageing aorta. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011, 132, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanalderwiert, L.; Henry, A.; Wahart, A.; Berrio, D.A.C.; Brauchle, E.M.; El Kaakour, L.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Brinckmann, J.; Steenbock, H.; Debelle, L.; et al. Metabolic syndrome-associated murine aortic wall stiffening is associated with premature elastic fibers aging. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2024, 327, C698–C715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocciolone, A.J. , et al., Elastin, arterial mechanics, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018, 315, H189–H205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, K.J.; Stolz, D.; Watkins, S.C.; Ahearn, J.M. Complement Proteins C3 and C4 Bind to Collagen and Elastin in the Vascular Wall: A Potential Role in Vascular Stiffness and Atherosclerosis. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011, 4, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenskiy, A.; Poulson, W.; Sim, S.; Reilly, A.; Luo, J.; MacTaggart, J. Prevalence of Calcification in Human Femoropopliteal Arteries and its Association with Demographics, Risk Factors, and Arterial Stiffness. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, e48–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brengle, B.M.; Lin, M.; Roth, R.A.; Jones, K.D.; Wagenseil, J.E.; Mecham, R.P.; Halabi, C.M. A new mouse model of elastin haploinsufficiency highlights the importance of elastin to vascular development and blood pressure regulation. Matrix Biol. 2023, 117, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doué, M.; Okwieka, A.; Berquand, A.; Gorisse, L.; Maurice, P.; Velard, F.; Terryn, C.; Molinari, M.; Duca, L.; Piétrement, C.; et al. Carbamylation of elastic fibers is a molecular substratum of aortic stiffness. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.P.; Cheng, J.K.; Kim, J.; Staiculescu, M.C.; Ficker, S.W.; Sheth, S.C.; Bhayani, S.A.; Mecham, R.P.; Yanagisawa, H.; Wagenseil, J.E. Mechanical factors direct mouse aortic remodelling during early maturation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2015, 12, 20141350–20141350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , et al., Sirtuin 6 attenuates angiotensin II-induced vascular adventitial aging in rat aortae by suppressing the NF-κB pathway. Hypertens Res. 2021, 44, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, Y. Pathogenesis of Aortic Dissection: Elastic Fiber Abnormalities and Aortic Medial Weakness. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2010, 3, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.D.; Gibson, C.C.; Sorensen, L.K.; Guilhermier, M.Y.; Clinger, M.; Kelley, L.L.; Shiu, Y.-T.E.; Li, D.Y. Novel Approach for Endothelializing Vascular Devices: Understanding and Exploiting Elastin–Endothelial Interactions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 39, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, M.A. , et al., Elastin-Derived Peptides Promote Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Formation by Modulating M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization. J Immunol. 2016, 196, 4536–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayral, S. , et al., Elastin-derived peptides potentiate atherosclerosis through the immune Neu1-PI3Kgamma pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2014, 102, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawecki, C.; Bocquet, O.; Schmelzer, C.E.H.; Heinz, A.; Ihling, C.; Wahart, A.; Romier, B.; Bennasroune, A.; Blaise, S.; Terryn, C.; et al. Identification of CD36 as a new interaction partner of membrane NEU1: potential implication in the pro-atherogenic effects of the elastin receptor complex. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 76, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, I.; Mizoiri, N.; Briones, M.P.P.; Okamoto, K. Induction of macrophage migration through lactose-insensitive receptor by elastin-derived nonapeptides and their analog. J. Pept. Sci. 2007, 13, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemianowicz, K.; Gminski, J.; Goss, M.; Francuz, T.; Likus, W.; Jurczak, T.; Garczorz, W. Influence of elastin-derived peptides on metalloprotease production in endothelial cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2010, 1, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, A., K. Philips, and N. Vyavahare, Elastin-derived peptides and TGF-beta1 induce osteogenic responses in smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 334, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocza, P.; Süli-Vargha, H.; Darvas, Z.; Falus, A. Locally generated VGVAPG and VAPG elastin-derived peptides amplify melanoma invasion via the galectin-3 receptor. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, I.; Kishita, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Arima, K.; Ideta, K.; Meng, J.; Sakata, N.; Okamoto, K. Immunochemical and Immunohistochemical Studies on Distribution of Elastin Fibres in Human Atherosclerotic Lesions using a Polyclonal Antibody to Elastin-derived Hexapeptide Repeat. J. Biochem. 2007, 142, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochizuki, S.; Brassart, B.; Hinek, A. Signaling Pathways Transduced through the Elastin Receptor Facilitate Proliferation of Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 44854–44863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanga, S.; Hibender, S.; Ridwan, Y.; van Roomen, C.; Vos, M.; van der Made, I.; van Vliet, N.; Franken, R.; van Riel, L.A.; Groenink, M.; et al. Aortic microcalcification is associated with elastin fragmentation in Marfan syndrome. J. Pathol. 2017, 243, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Fortun, A.; Robert, L.; Khalil, A. Elastin peptides induced oxidation of LDL by phagocytic cells. Pathol. Biol. 2005, 53, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Donckt, C. , et al., Elastin fragmentation in atherosclerotic mice leads to intraplaque neovascularization, plaque rupture, myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death. Eur Heart J. 2015, 36, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkovic, K.; Larroque-Cardoso, P.; Pucelle, M.; Salvayre, R.; Waeg, G.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Zarkovic, N. Elastin aging and lipid oxidation products in human aorta. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Kim, B.C.; Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Isak, A.; Bexiga, N.M.; Monticone, R.; Ha, T.; Lakatta, E.G.; An, S.S. TGFβ1 reinforces arterial aging in the vascular smooth muscle cell through a long-range regulation of the cytoskeletal stiffness. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenders, M.M.; Yang, L.; Wismans, R.G.; van der Werf, K.O.; Reinhardt, D.P.; Daamen, W.; Bennink, M.L.; Dijkstra, P.J.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Feijen, J. Microscale mechanical properties of single elastic fibers: The role of fibrillin–microfibrils. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Monticone, R.E.; McGraw, K.R.; Wang, M. Age-associated proinflammatory elastic fiber remodeling in large arteries. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 196, 111490–111490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Brooke, B.; Davis, E.C.; Mecham, R.P.; Sorensen, L.K.; Boak, B.B.; Eichwald, E.; Keating, M.T. Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature 1998, 393, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.D.; Endicott, S.K.; A Province, M.; A Pierce, J.; Campbell, E.J. Marked longevity of human lung parenchymal elastic fibers deduced from prevalence of D-aspartate and nuclear weapons-related radiocarbon. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 87, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, S.; Suzumura, T.; Nakamura, A.; Tsukiji, S.; Ujihara, Y.; Nakamura, M. Second harmonic generation light quantifies the ratio of type III to total (I + III) collagen in a bundle of collagen fiber. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Wang, S.; Seo, H.; Kurotaki, T.; Ueki, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Ultrastructure of Aortic Elastic Fibers in Copper-Deficient Sika Deer(Cervus nippon Temminck). J. Veter- Med Sci. 2001, 63, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Lakatta, E.G. Altered Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 in Aortic Remodeling During Aging. Hypertension 2002, 39, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Walker, S.J.; Dworakowski, R.; Lakatta, E.G.; Shah, A.M. Involvement of NADPH oxidase in age-associated cardiac remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wu, A.; Wang, J.; Chang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Lou, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. Activation and Migration of Adventitial Fibroblasts Contributes to Vascular Remodeling. Anat. Rec. 2018, 301, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.A.; Nourian, Z.; Ho, I.-L.; Clifford, P.S.; Martinez-Lemus, L.; Meininger, G.A. Small Artery Elastin Distribution and Architecture-Focus on Three Dimensional Organization. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.M.; Kang, S.; Hong, B.K.; Kim, D.; Park, H.Y.; Shin, M.S.; Byun, K.H. Ultrastructural changes of the external elastic lamina in experimental hypercholesterolemic porcine coronary arteries. Yonsei Med J. 1999, 40, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J. , et al., Heterogeneous Cellular Contributions to Elastic Laminae Formation in Arterial Wall Development. Circ Res. 2019, 125, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.W.; Lowery, A.M.; Sun, L.-Y.; Singer, H.A.; Dai, G.; Adam, A.P.; Vincent, P.A.; Schwarz, J.J. Endothelial Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2c Inhibits Migration of Smooth Muscle Cells Through Fenestrations in the Internal Elastic Lamina. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuoka, T.; Hayashi, N.; Hori, E.; Kuwayama, N.; Ohtani, O.; Endo, S. Distribution of Internal Elastic Lamina and External Elastic Lamina in the Internal Carotid Artery: Possible Relationship With Atherosclerosis. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010, 50, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, J.; Dave, J.M.; Lau, F.D.; Greif, D.M. Presenilin-1 in smooth muscle cells facilitates hypermuscularization in elastin aortopathy. iScience 2023, 27, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruda, T.; Kato, J.; Hatakeyama, K.; Kojima, K.; Yano, M.; Yano, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Nakamura-Uchiyama, F.; Matsushima, Y.; Imamura, T.; et al. Adventitial Mast Cells Contribute to Pathogenesis in the Progression of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pérez, M.; Camasão, D.B.; Mantovani, D.; Alonso, M.; Rodríguez-Cabello, J.C. Biocasting of an elastin-like recombinamer and collagen bi-layered model of the tunica adventitia and external elastic lamina of the vascular wall. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 3860–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.S.; Adio, A.O.; Pitt, A.; Hayman, L.; Thorn, C.E.; Shore, A.C.; Whatmore, J.L.; Winlove, C.P. Microstructural Characterization of Resistance Artery Remodelling in Diabetes Mellitus. J. Vasc. Res. 2021, 59, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J. , et al., Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Subpopulations and Neointimal Formation in Mouse Models of Elastin Insufficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021, 41, 2890–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faury, G.; Pezet, M.; Knutsen, R.H.; A Boyle, W.; Heximer, S.P.; E McLean, S.; Minkes, R.K.; Blumer, K.J.; Kovacs, A.; Kelly, D.P.; et al. Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, S.S. Integration and Modulation of Intercellular Signaling Underlying Blood Flow Control. J. Vasc. Res. 2015, 52, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H.; Putta, P.; Driscoll, E.C.; Chaudhuri, P.; Birnbaumer, L.; Rosenbaum, M.A.; Graham, L.M. Canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel deficiency promotes smooth muscle cells dedifferentiation and increased proliferation after arterial injury. JVS: Vasc. Sci. 2020, 1, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, H.; Katsumata, Y.; Higashi, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Morgan, S.; Lee, L.H.; Singh, S.A.; Chen, J.Z.; Franklin, M.K.; et al. Second Heart Field–Derived Cells Contribute to Angiotensin II–Mediated Ascending Aortopathies. Circulation 2022, 145, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, S.; Tarbell, J.M. Interstitial flow through the internal elastic lamina affects shear stress on arterial smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2000, 278, H1589–H1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, B.S.; Bruhl, A.; Sullivan, M.N.; Francis, M.; Dinenno, F.A.; Earley, S. Robust Internal Elastic Lamina Fenestration in Skeletal Muscle Arteries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, P.S. , et al., Spatial distribution and mechanical function of elastin in resistance arteries: a role in bearing longitudinal stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011, 31, 2889–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, A.J.; Osei-Owusu, P. Elastin haploinsufficiency accelerates age-related structural and functional changes in the renal microvasculature and impairment of renal hemodynamics in female mice. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, S.; Rice, C.D.; Vyavahare, N.R. Reversal of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm following the delivery of nanoparticle-based pentagalloyl glucose (PGG) is associated with reduced inflammatory and immune markers. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 910, 174487–174487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, J.T. and M.D. Tallquist, Tracking Adventitial Fibroblast Contribution to Disease: A Review of Current Methods to Identify Resident Fibroblasts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017, 37, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiellaro, K.; Taylor, W.R. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 75, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Kitajima, S.; Quan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liu, E.; Lai, L.; Yan, H.; Fan, J. Macrophage elastase derived from adventitial macrophages modulates aortic remodeling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 10, 1097137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D. , et al., Synergistic activity of alphavbeta3 integrins and the elastin binding protein enhance cell-matrix interactions on bioactive hydrogel surfaces. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Ye, P.; Zhang, K.; Ma, X.; Wu, Q. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Inhibits the Progression of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Mice: The Earlier, the Better. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2023, 38, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Z.; Sawada, H.; Ye, D.; Katsumata, Y.; Kukida, M.; Ohno-Urabe, S.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Franklin, M.K.; Howatt, D.A.; Sheppard, M.B.; et al. Deletion of AT1a (Angiotensin II Type 1a) Receptor or Inhibition of Angiotensinogen Synthesis Attenuates Thoracic Aortopathies in Fibrillin1 C1041G/+ Mice. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, A.; Gourgas, O.; Lau, K.; Li, J.; Muiznieks, L.; Sharpe, S.; Davis, E.; Cerruti, M.; Murshed, M. Elastin calcification in in vitro models and its prevention by MGP’s N-terminal peptide. J. Struct. Biol. 2020, 213, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satta, J.; Laurila, A.; Pääkkö, P.; Haukipuro, K.; Sormunen, R.; Parkkila, S.; Juvonen, T. Chronic inflammation and elastin degradation in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 1998, 15, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, H.; Zhuang, Y.-J.; Singh, T.M.; Kawamura, K.; Murakami, M.; Zarins, C.K.; Glagov, S. Adaptive Remodeling of Internal Elastic Lamina and Endothelial Lining During Flow-Induced Arterial Enlargement. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mieremet, A.; van der Stoel, M.; Li, S.; Coskun, E.; van Krimpen, T.; Huveneers, S.; de Waard, V. Endothelial dysfunction in Marfan syndrome mice is restored by resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Vyavahare, N.R. High-glucose levels and elastin degradation products accelerate osteogenesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2013, 10, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majesky, M.W. , et al., The Adventitia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarad, K.; Jankowska, U.; Skupien-Rabian, B.; Babler, A.; Kramann, R.; Dulak, J.; Jaźwa-Kusior, A. Senescence of endothelial cells promotes phenotypic changes in adventitial fibroblasts: possible implications for vascular aging. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majesky, M.W. , et al., The adventitia: a dynamic interface containing resident progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011, 31, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Liu, L.-Z.; He, Z.-H.; Ding, K.-H.; Xue, F. Phenotypic transformation and migration of adventitial cells following angioplasty. Exp. Ther. Med. 2012, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simionescu, A., D. T. Simionescu, and N.R. Vyavahare, Osteogenic responses in fibroblasts activated by elastin degradation products and transforming growth factor-beta1: role of myofibroblasts in vascular calcification. Am J Pathol. 2007, 171, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, P.; Naukkarinen, A.; Heikkilä, L.; Penttilä, A.; Kovanen, P.T. Adventitial Mast Cells Connect With Sensory Nerve Fibers in Atherosclerotic Coronary Arteries. Circulation 2000, 101, 1665–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Takagi, G.; Asai, K.; Resuello, R.G.; Natividad, F.F.; Vatner, D.E.; Vatner, S.F.; Lakatta, E.G. Aging Increases Aortic MMP-2 Activity and Angiotensin II in Nonhuman Primates. Hypertension 2003, 41, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Shi, M.A.; Sukhova, G.K.; Shi, G.-P. Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 mediates mast cell migration to abdominal aortic aneurysm lesions in mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 96, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. , et al., Matrix metalloproteinase 2 activation of transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) and TGF-beta1-type II receptor signaling within the aged arterial wall. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006, 26, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.D. , et al., Macrophage-Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Signaling in Carotid Artery Stenosis. Am J Pathol. 2021, 191, 1118–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedding, D.G.; Boyle, E.C.; Demandt, J.A.F.; Sluimer, J.C.; Dutzmann, J.; Haverich, A.; Bauersachs, J. Vasa Vasorum Angiogenesis: Key Player in the Initiation and Progression of Atherosclerosis and Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.M.; Pearce, S.W.; Xiao, Q. Foam cell formation: A new target for fighting atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 112, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Liu, H.; Zhan, W.; Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Tian, S.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Tian, X. Chronological attenuation of NPRA/PKG/AMPK signaling promotes vascular aging and elevates blood pressure. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicher, B.O.; Zhang, J.; Muratoglu, S.C.; Galisteo, R.; Arai, A.L.; Gray, V.L.; Lal, B.K.; Strickland, D.K.; Ucuzian, A.A. Moderate aerobic exercise prevents matrix degradation and death in a mouse model of aortic dissection and aneurysm. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1786–H1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, G.; Ujihara, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Sugita, S. Delamination Strength and Elastin Interlaminar Fibers Decrease with the Development of Aortic Dissection in Model Rats. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Cai, D.; Dong, K.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.-Y. DOCK2 Deficiency Attenuates Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Formation—Brief Report. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, E210–E217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, V.P.; Knutsen, R.H.; Mecham, R.P.; Wagenseil, J.E.; Ogola, B.O.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Clark, G.L.; Abshire, C.M.; Gentry, K.M.; Miller, K.S.; et al. Decreased aortic diameter and compliance precedes blood pressure increases in postnatal development of elastin-insufficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H221–H229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, J.Z.; Cocciolone, A.J.; Cui, A.H.; Griffin, D.B.; Staiculescu, M.C.; Mecham, R.P.; Wagenseil, J.E. Elastin haploinsufficiency in mice has divergent effects on arterial remodeling with aging depending on sex. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2020, 319, H1398–H1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, E. , et al., Functional rescue of elastin insufficiency in mice by the human elastin gene: implications for mouse models of human disease. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenseil, J.E.; Nerurkar, N.L.; Knutsen, R.H.; Okamoto, R.J.; Li, D.Y.; Mecham, R.P. Effects of elastin haploinsufficiency on the mechanical behavior of mouse arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H1209–H1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Faury, G.; Taylor, D.G.; Davis, E.C.; Boyle, W.A.; Mecham, R.P.; Stenzel, P.; Boak, B.; Keating, M.T. Novel arterial pathology in mice and humans hemizygous for elastin. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Sakata, N.; Meng, J.; Sakamoto, M.; Noma, A.; Maeda, I.; Okamoto, K.; Takebayashi, S. Possible involvement of increased glycoxidation and lipid peroxidation of elastin in atherogenesis in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, A.C. , Do metalloproteinases destabilize vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques? Curr Opin Lipidol 2006, 17, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momi, S.; Falcinelli, E.; Petito, E.; Taranta, G.C.; Ossoli, A.; Gresele, P. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 on activated platelets triggers endothelial PAR-1 initiating atherosclerosis. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 43, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Muñoz-García, B.; Ott, C.-E.; Grünhagen, J.; Mousa, S.A.; Pletschacher, A.; von Kodolitsch, Y.; Knaus, P.; Robinson, P.N. Antagonism of GxxPG fragments ameliorates manifestations of aortic disease in Marfan syndrome mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 22, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doren, S.R. , Matrix metalloproteinase interactions with collagen and elastin. Matrix Biol 2015, 44, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. , et al., Calorie Restriction Curbs Proinflammation That Accompanies Arterial Aging, Preserving a Youthful Phenotype. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7, e009112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).