Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

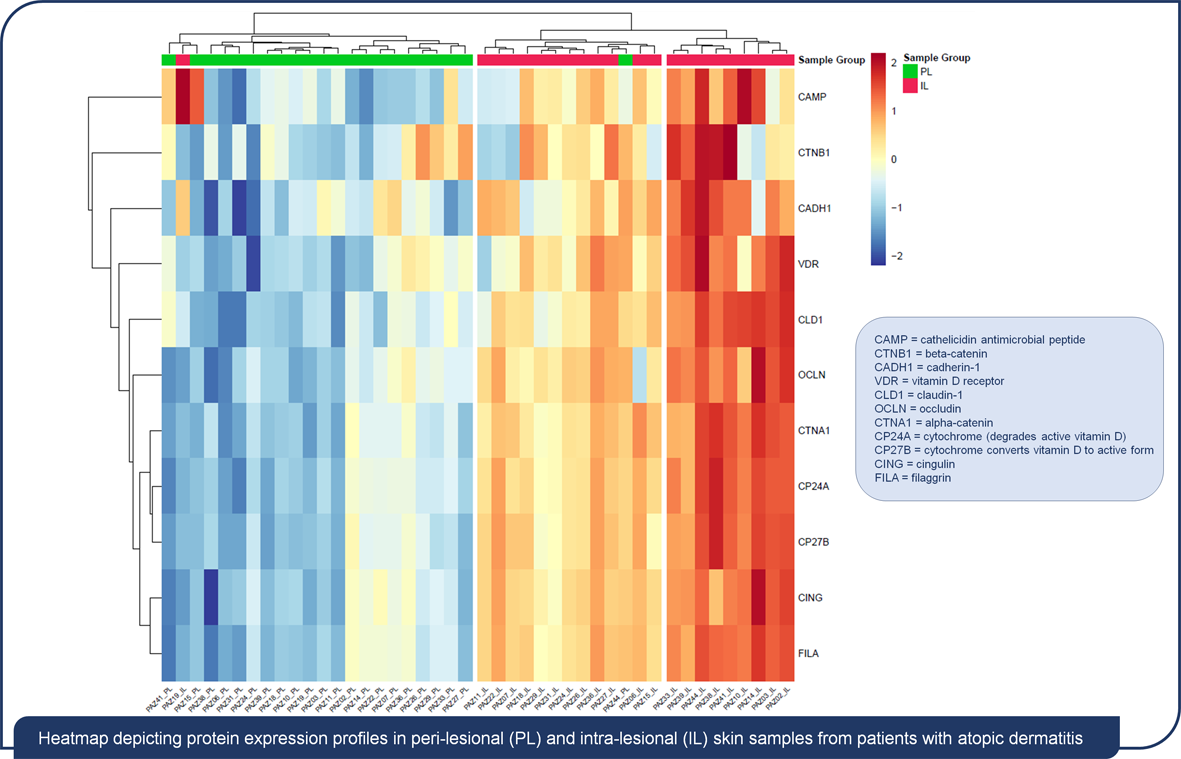

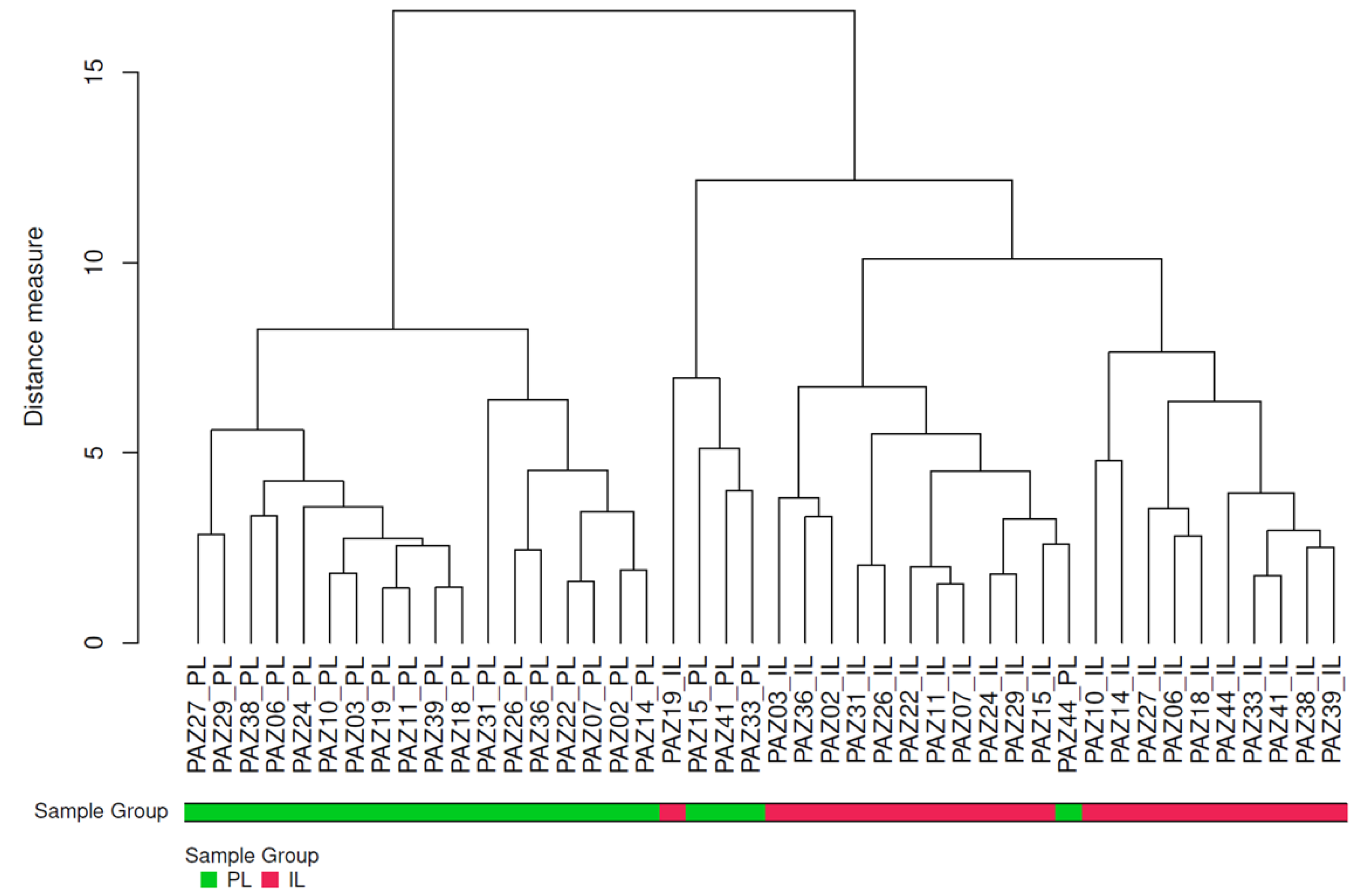

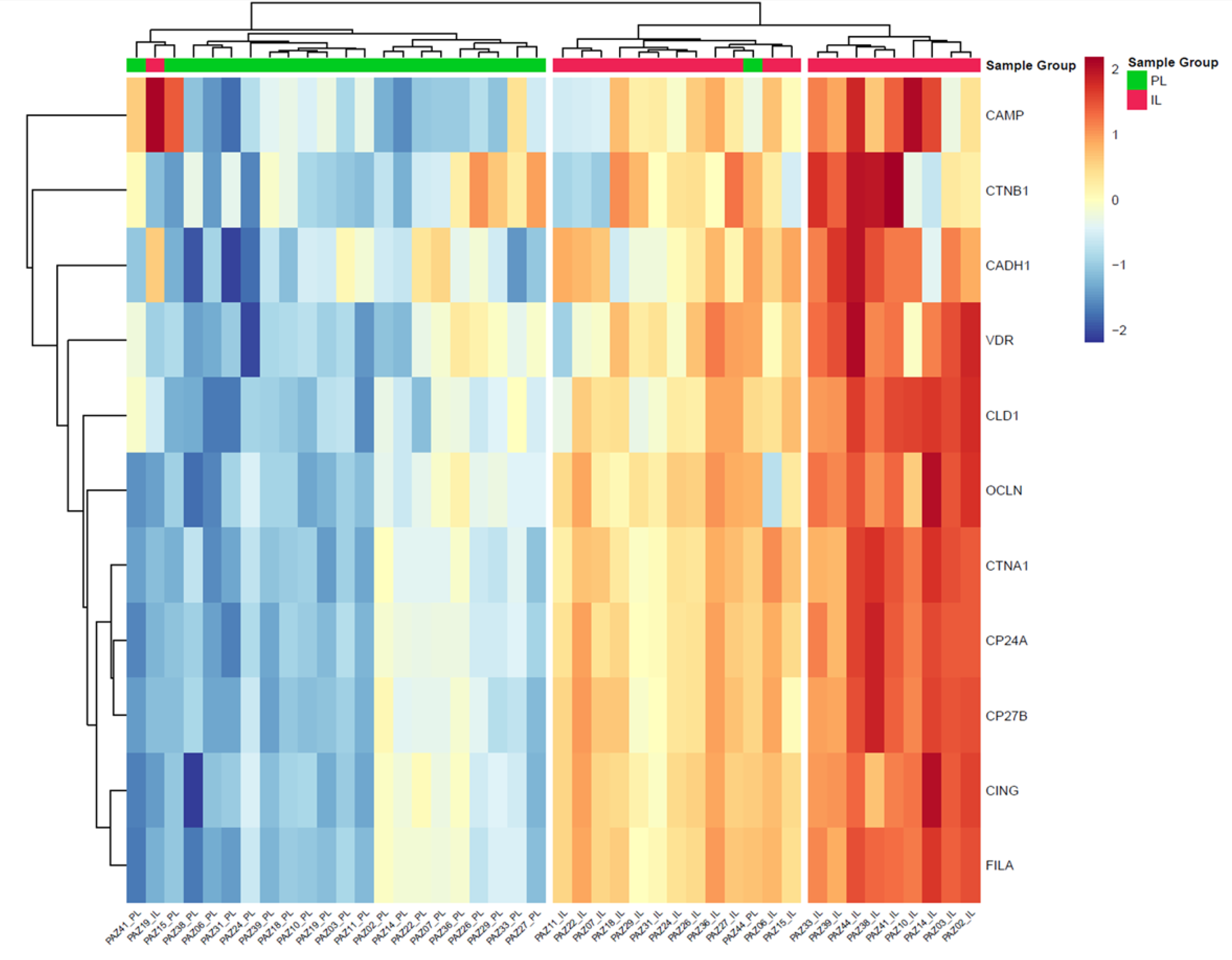

2.2. Comparison of Protein Concentrations in Intra and Peri-lesional Biopsies

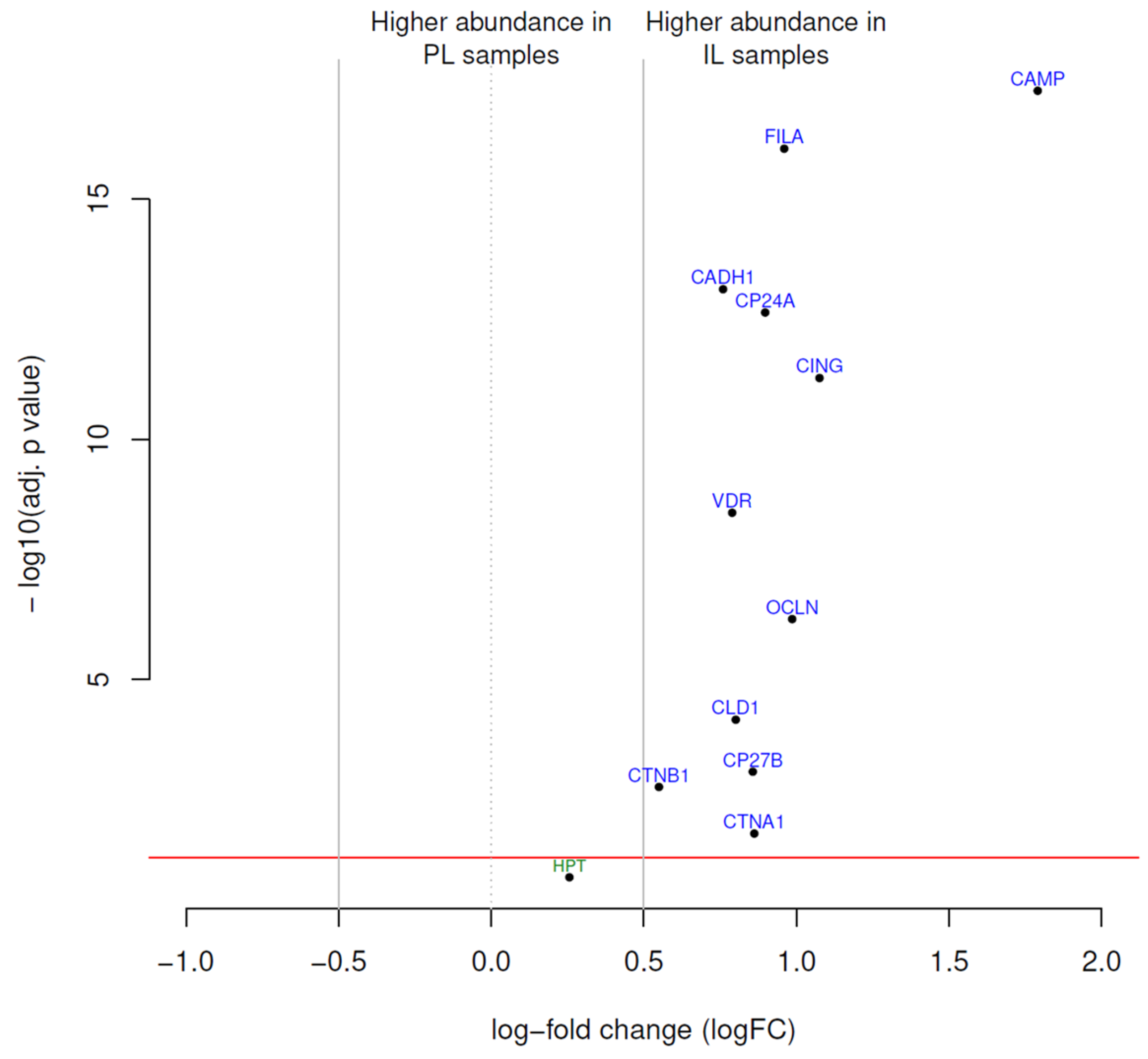

2.3. Differential Protein Expression

2.4. Association Between Clinical Characteristics and Protein Expression from Intra- and Peri-Lesional Areas

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Patients

4.2. Biopsy Sampling

4.3. Protein Extraction

4.4. Sample Labelling and Data Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Stripling, S.; Fung, S.; Cha, A.; O’Brien, A.; Schachner, L.A. Recent Developments and Advances in Atopic Dermatitis: A Focus on Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment in the Pediatric Setting. Paediatr Drugs 2022, 24, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieber, T. Atopic Dermatitis. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 358, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bylund, S.; Kobyletzki, L.B.; Svalstedt, M.; Svensson, Å. Prevalence and Incidence of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Acta Derm Venereol 2020, 100, adv00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, H.; Nishikawa, M.; Yamada, S. Development of Tight Junction-Strengthening Compounds Using a High-Throughput Screening System to Evaluate Cell Surface-Localized Claudin-1 in Keratinocytes. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Ishida, A.; Kubo, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Ochiai, S.; Nakayama, M.; Koseki, H.; Amagai, M.; Okada, T. Homeostatic Pruning and Activity of Epidermal Nerves Are Dysregulated in Barrier-Impaired Skin during Chronic Itch Development. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Manousaki, D.; Rosen, C.; Trajanoska, K.; Rivadeneira, F.; Richards, J.B. The Health Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation: Evidence from Human Studies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S.; Giusti, A.; Minisola, S.; Napoli, N.; Passeri, G.; Rossini, M.; Sinigaglia, L. The Immunologic Profile of Vitamin D and Its Role in Different Immune-Mediated Diseases: An Expert Opinion. Nutrients 2022, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenngam, N. Vitamin D and Rheumatic Diseases: A Review of Clinical Evidence. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsbak, M.; Levring, T.; Geisler, C.; von Essen, M. The Vitamin D Receptor and T Cell Function. Frontiers in Immunology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Sastry, K.S.; Al Ali, F.; Al-Khulaifi, M.; Wang, E.; Chouchane, A.I. Vitamin D and the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2018, 31, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauber, J.; Dorschner, R.A.; Coda, A.B.; Büchau, A.S.; Liu, P.T.; Kiken, D.; Helfrich, Y.R.; Kang, S.; Elalieh, H.Z.; Steinmeyer, A.; et al. Injury Enhances TLR2 Function and Antimicrobial Peptide Expression through a Vitamin D-Dependent Mechanism. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhaylov, D.; Del Duca, E.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Proteomic Signatures of Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Focus on Atopic Dermatitis. Expert Rev Proteomics 2021, 18, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitamura, Y.; Reiger, M.; Kim, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhakparov, D.; Tan, G.; Rückert, B.; Rinaldi, A.O.; Baerenfaller, K.; Akdis, M.; et al. Spatial Transcriptomics Combined with Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing Unravels the Complex Inflammatory Cell Network in Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy 2023, 78, 2215–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotas, M.; Schleusener, J.; Lademann, J.; Meinke, M.C.; Kokolakis, G.; Darvin, M.E. Atopic Dermatitis: Molecular Alterations between Lesional and Non-Lesional Skin Determined Noninvasively by In Vivo Confocal Raman Microspectroscopy. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, A.B.; Zhou, L.; Diaz, A.; Ungar, B.; Dan, J.; He, H.; Estrada, Y.D.; Xu, H.; Fernandes, M.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; et al. The Proteomic Skin Profile of Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis Patients Shows an Inflammatory Signature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020, 82, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, T.; Moliterni, E.; Paolino, G.; Chello, C.; Sernicola, A.; Egan, C.G.; Nannipieri, F.; Battaglia, S.; Accoto, M.; Tirotta, E.; et al. Association between Vitamin D Receptor Polymorphisms, Tight Junction Proteins and Clinical Features of Adult Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol Pract Concept 2024, 14, e2024214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Kishibe, M.; Murakami, M.; Honma, M.; Takahashi, H.; Iizuka, H. Lamellar Granule Secretion Starts before the Establishment of Tight Junction Barrier for Paracellular Tracers in Mammalian Epidermis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, N.; Houdek, P.; Fromm, M.; Moll, I.; Brandner, J.M. Tight Junctions Form a Barrier in Human Epidermis. Eur J Cell Biol 2010, 89, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yokouchi, M.; Nagao, K.; Ishii, K.; Amagai, M.; Kubo, A. Functional Tight Junction Barrier Localizes in the Second Layer of the Stratum Granulosum of Human Epidermis. J Dermatol Sci 2013, 71, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, A.D.; Rafaels, N.M.; McGirt, L.Y.; Ivanov, A.I.; Georas, S.N.; Cheadle, C.; Berger, A.E.; Zhang, K.; Vidyasagar, S.; Yoshida, T.; et al. Tight Junction Defects in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2011, 127, 773–786.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, S.; Makris, M.; Vakirlis, E.; Gregoriou, S. The Role of Tight Junctions in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, R.; Börnchen, C.; Rose, K.; Daubmann, A.; Volksdorf, T.; Wladykowski, E.; Vidal-y-Sy, S.; Peters, E.M.; Danso, M.; Bouwstra, J.A.; et al. Diverse Regulation of Claudin-1 and Claudin-4 in Atopic Dermatitis. The American Journal of Pathology 2015, 185, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, S.; von Buenau, B.; Vidal-y-Sy, S.; Haftek, M.; Wladykowski, E.; Houdek, P.; Lezius, S.; Duplan, H.; Bäsler, K.; Dähnhardt-Pfeiffer, S.; et al. Claudin-1 Decrease Impacts Epidermal Barrier Function in Atopic Dermatitis Lesions Dose-Dependently. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuki, T.; Tobiishi, M.; Kusaka-Kikushima, A.; Ota, Y.; Tokura, Y. Impaired Tight Junctions in Atopic Dermatitis Skin and in a Skin-Equivalent Model Treated with Interleukin-17. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.J. Regulation of Cell–Cell Adhesion by the Cadherin–Catenin Complex. Biochem Soc Trans 2008, 36, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drislane, C.; Irvine, A.D. The Role of Filaggrin in Atopic Dermatitis and Allergic Disease. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2020, 124, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.M.B.; Sherenian, M.G.; kyzy, A.B.; Alarcon, R.; An, A.; Flege, Z.; Morgan, D.; Gonzalez, T.; Stevens, M.L.; He, H.; et al. Events in Normal Skin Promote Early-Life Atopic Dermatitis - the MPAACH Cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020, 8, 2285–2293.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, C.J.; Mahaffey, S.; Schwarz, J.; Wruck, L.; David, G.; Schlievert, P.M.; Reisdorph, N.A.; Leung, D.Y.M. Comparative Proteomic Profiling of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis Based on History of Eczema Herpeticum Infection and Staphylococcus Aureus Colonization. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011, 127, 186–193, 193.e1-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, S.; K, K.; H, Y.; S, I.; T, S.; M, A.; K, T.; T, F.; M, S.; T, Y.; et al. Proteome Analysis of Stratum Corneum from Atopic Dermatitis Patients by Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2014, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T, K.; A, M.-F.; A, M. Stratum Corneum Hydration and Skin Surface pH in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC 2011, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Nograles, K.E.; Krueger, J.G. Contrasting Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis--Part II: Immune Cell Subsets and Therapeutic Concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011, 127, 1420–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Barrier Epithelial Cells and the Control of Type 2 Immunity. Immunity 2015, 43, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Rodriguez, E.; Degenhardt, F.; Baurecht, H.; Wehkamp, U.; Volks, N.; Szymczak, S.; Swindell, W.R.; Sarkar, M.K.; Raja, K.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis Is an IL-13-Dominant Disease with Greater Molecular Heterogeneity Compared to Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2019, 139, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokouchi, M.; Kubo, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Yoshida, K.; Ishii, K.; Furuse, M.; Amagai, M. Epidermal Tight Junction Barrier Function Is Altered by Skin Inflammation, but Not by Filaggrin-Deficient Stratum Corneum. J Dermatol Sci 2015, 77, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weise Christin ; Worm Margitta and Rühl Ralph Increased Vitamin D Signalling Markers in the Skin of Atopic Dermatitis Patients. JOJDC 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Charman, C.R.; Venn, A.J.; Ravenscroft, J.C.; Williams, H.C. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) Scores into Clinical Practice by Suggesting Severity Strata Derived Using Anchor-Based Methods. Br J Dermatol 2013, 169, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalín, C.; Pérez-Mateluna, G.; Iturriaga, C.; Camargo, C.A.; Borzutzky, A. Oral Vitamin D Modulates the Epidermal Expression of the Vitamin D Receptor and Cathelicidin in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res 2023, 315, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stio, M.; Retico, L.; V, A.; Ag, B. Vitamin D Regulates the Tight-Junction Protein Expression in Active Ulcerative Colitis. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 2016, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifin, J.M.; Thurston, M.; Omoto, M.; Cherill, R.; Tofte, S.J.; Graeber, M. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): Assessment of Reliability in Atopic Dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol 2001, 10, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 13 (59.1) |

| Female | 9 (40.9) |

| Age | |

| <60 years | 19 (86.4) |

| ≥60 years | 3 (13.6) |

| EASI score | |

| Mild (EASI <16) | 5 (22.7) |

| Moderate-to-severe (EASI ≥16 or <16 with face/hand involvement) |

17 (77.3) |

| Phenotype (localisation), n (%) | |

| Generalised | 8 (36.4) |

| Head/neck | 7 (31.8) |

| Flexural sites | 6 (27.3) |

| Hands | 1 (4.5) |

| Age of disease onset, n (%) | |

| Childhood | 13 (59.1) |

| Adulthood | 9 (40.9) |

| Asthma, n (%) | |

| Present | 20 (90.9) |

| Absent | 2 (9.1%) |

| Rhino conjunctivitis, n (%) | |

| Present | 15 (68.2) |

| Absent | 7 (31.8) |

| Skin prick test, n (%) | |

| Present | 12 (54.5) |

| Absent | 10 (45.5) |

| Total IgE (IU/ml), n (%) | |

| ≥100 IU/ml | 12 (54.5) |

| <100 IU/ml | 10 (45.5) |

| 25(OH)D vitamin D | |

| ≥30 ng/ml | 6 (27.3) |

| <30 ng/ml | 16 (72.7) |

| Protein | Antibody ID | Uniprot Entry* | HGNC | logFC | AveExp | p-adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMP | ab1184 | P49913 | CAMP | 1.79 | 12.82 | 5.50×10−18 |

| CING | ab1193 | Q9P2M7 | CGN | 1.08 | 10.11 | 5.30×10−12 |

| OCLN | ab1169 | Q16625 | OCLN | 0.99 | 10.48 | 5.50×10−7 |

| FILA | ab1199 | P20930 | FLG | 0.96 | 10.46 | 8.90×10−17 |

| CP24A | ab1156 | Q07973 | CYP24A1 | 0.9 | 10.82 | 2.30×10−13 |

| CTNA1 | ab1187 | P35221 | CTNNA1 | 0.86 | 10.66 | 0.016 |

| CP27B | ab1185 | O15528 | CYP27B1 | 0.86 | 10.7 | 8.30×10−4 |

| CLD1 | ab1158 | O95832 | CLDN1 | 0.8 | 10.35 | 6.90×10−5 |

| VDR | ab1080 | P11473 | VDR | 0.79 | 11.12 | 3.40×10−9 |

| CADH1 | ab1182 | P12830 | CDH1 | 0.76 | 14.71 | 7.50×10−14 |

| CTNB1 | ab1183 | P35222 | CTNNB1 | 0.55 | 13.24 | 0.0017 |

| HPT | ab1194 | P00738 | HP | 0.26 | 14.77 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin D metabolism | Epithelial barrier | Immune response and inflammation | ||||||||||||

| n | VDR | CYP24A | CPY27B | FILA | CLD1 | OCLN | CADH1 | CTNB1 | CTNA1 | CING | HPT | CAMP | ||

| Gender | male | 13 | 0.5(0.5) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.6(0.7) | 0.7(0.3) | 0.4(0.6) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.9(0.6) | 0.4(0.9) | 0.9(1.2) |

| female | 9 | 0.5(0.6) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.9(0.5) | 1(0.7) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.9) | 1.2(1.2) | |

| p-value | 0.343 | 0.366 | 0.392 | 0.414 | 0.477 | 0.275 | 0.100 | 0.034 | 0.469 | 0.454 | 0.082 | 0.278 | ||

| Localizzation | not flexural | 16 | 0.5(0.5) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.7(0.8) | 1(0.3) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.8(0.8) | 1.1(1.1) |

| flexural | 6 | 0.5(0.6) | 0.7(0.6) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.7(0.6) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.6(0.8) | 0.7(0.3) | 0.4(0.6) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.8(0.8) | 0.2(1.1) | 0.8(1.3) | |

| p-value | 0.431 | 0.215 | 0.287 | 0.233 | 0.363 | 0.289 | 0.262 | 0.156 | 0.147 | 0.264 | 0.087 | 0.342 | ||

| 25(OH)D levels | ≥30 ng/ml | 6 | 0.4(0.6) | 0.6(0.5) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.6(0.6) | 0.6(0.5) | 0.4(0.7) | 0.6(0.4) | 0.4(0.5) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.6(0.8) | 0(1.3) | 1.6(1.2) |

| < 30 ng/ml | 16 | 0.5(0.5) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.7(0.8) | 1(0.3) | 1(0.3) | 0.8(0.7) | 0.8(1.1) | |

| p-value | 0.241 | 0.054 | 0.065 | 0.072 | 0.215 | 0.068 | 0.101 | 0.178 | 0.043 | 0.075 | 0.033 | 0.078 | ||

| ≥20 ng/ml | 16 | 0.5(0.6) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.7(0.6) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.5(0.7) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.9(0.6) | 0.4(0.9) | 1.1(1.2) | |

| < 20 ng/ml | 6 | 0.4(0.4) | 0.9(0.3) | 1(0.3) | 0.9(0.2) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.8(0.3) | 1(0.8) | 1(0.3) | 0.9(0.2) | 1.2(0.6) | 0.7(1) | |

| p-value | 0.326 | 0.179 | 0.152 | 0.307 | 0.392 | 0.446 | 0.491 | 0.094 | 0.167 | 0.466 | 0.021 | 0.209 | ||

| Skin Prick Test | negative | 10 | 0.2(0.5) | 0.6(0.4) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.6(0.5) | 0.6(0.4) | 0.5(0.5) | 0.7(0.3) | 0.4(0.6) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.7(0.6) | 0.9(0.6) | 0.7(1.4) |

| positive | 12 | 0.7(0.4) | 1(0.3) | 1(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.9(0.8) | 1.1(0.3) | 1(0.4) | 0.4(1.1) | 1.3(0.9) | |

| p-value | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.061 | 0.065 | 0.122 | 0.060 | 0.022 | 0.052 | 0.090 | 0.118 | ||

| IgG levels | <100 IU/mL | 11 | 0.2(0.5) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.7(0.4) | 0.6(0.4) | 0.4(0.6) | 0.8(0.3) | 0.4(0.8) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.7(0.5) | 0.8(0.7) | 1(1.4) |

| ≥100 IU/mL | 11 | 0.8(0.4) | 0.9(0.4) | 1(0.4) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.6) | 1(0.4) | 1(0.5) | 0.4(1.1) | 1(0.9) | |

| p-value | 0.007 | 0.113 | 0.133 | 0.120 | 0.168 | 0.011 | 0.393 | 0.041 | 0.143 | 0.106 | 0.142 | 0.440 | ||

| EASI | <16 | 5 | 0.2(0.5) | 0.5(0.5) | 0.6(0.5) | 0.5(0.5) | 0.5(0.3) | 0.3(0.7) | 0.6(0.3) | 0.5(0.8) | 0.6(0.4) | 0.5(0.7) | 0.7(1.4) | 1(1.4) |

| ≥16 | 17 | 0.6(0.5) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.9(0.3) | 0.8(0.4) | 0.8(0.5) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.7(0.7) | 1(0.3) | 1(0.4) | 0.6(0.8) | 1(1.1) | |

| p-value | 0.111 | 0.024 | 0.044 | 0.027 | 0.059 | 0.049 | 0.052 | 0.294 | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.393 | 0.490 | ||

| Vitamin D metabolism | Epithelial barrier | Immune response and Inflammation |

|||||||||||

| CYP24A | CYP27B | VDR | OCLN | CING | CLD1 | FILA | CADH1 | CTNA1 | CTNB1 | CAMP | HPT | ||

| Age of onset (childhood) |

β (95% CI) |

-0.56 (-6.28,5.16) |

0.46 (-2.63,3.55) |

0.34 (-0.74,1.42) |

-0.52 (-1.51,0.48) |

-0.54 (-3.36,2.29) |

1.14 (-0.99,3.26) |

-1.34 (-8.62,5.93) |

-0.04 (-0.74,0.65) |

2.06 (-1.26,5.38) |

-0.04 (-0.70,0.62) |

-0.26 (-0.51,-0.02) |

-0.05 (-0.41,0.31) |

| S.E. | 2.53 | 1.37 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.94 | 3.22 | 0.31 | 1.47 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.16 | |

| T | -0.22 | 0.34 | 0.72 | -1.17 | -0.43 | 1.21 | -0.42 | -0.15 | 1.41 | -0.15 | -2.40 | -0.31 | |

| p-value | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.039 | 0.76 | |

| Phenotype (Flexural site) |

β (95% CI) |

3.53 (-1.96,9.03) |

2.46 (-0.51,5.43) |

0.44 (-0.60,1.47) |

-0.85 (-1.81,0.11) |

1.37 (-1.35,4.09) |

2.06 (0.02,4.10) |

-4.56 (-11.55,2.43) |

-0.16 (-0.83,0.51) |

-4.16 (-7.34,-0.97) |

-0.17 (-0.81,0.46) |

-0.15 (-0.38,0.09) |

-0.19 (-0.54,0.15) |

| S.E. | 2.43 | 1.31 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 1.20 | 0.90 | 3.09 | 0.29 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.15 | |

| T | 1.45 | 1.87 | 0.95 | -2.00 | 1.14 | 2.28 | -1.48 | -0.55 | -2.95 | -0.62 | -1.38 | -1.28 | |

| p-value | 0.18 | 0.094 | 0.37 | 0.077 | 0.28 | 0.048 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.016 | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.23 | |

| Asthma or Rhino conjunctivitis (present) |

β (95% CI) |

-0.76 (-6.95,5.54) |

1.24 (-2.11,4.59) |

0.23 (-0.94,1.40) |

-0.13 (-1.21,0.95) |

1.56 (-1.50,4.62) |

-0.26 (-2.56,2.04) |

-2.68 (-10.56,5.21) |

0.42 (-0.33,1.18) |

-0.06 (-3.65,3.53) |

0.40 (-0.32,1.11) |

-0.02 (-0.29,0.25) |

-0.39 (-0.77,-0.00) |

| S.E. | 2.74 | 1.48 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1.35 | 1.02 | 3.48 | 0.33 | 1.59 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.17 | |

| T | -0.28 | 0.84 | 0.45 | -0.27 | 1.15 | -0.25 | -0.77 | 1.28 | -0.04 | 1.26 | -0.19 | -2.26 | |

| p-value | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 0.86 | 0.05 | |

| Skin prick test (positive) |

β (95% CI) |

-2.69 (-7.75,2.37) |

1.87 (-0.87,4.60) |

0.60 (-0.35,1.56) |

-0.00 (-0.88,0.88) |

-0.23 (-2.73,2.27) |

-1.93 (-3.81,-0.05) |

0.04 (-6.40,6.48) |

0.40 (-0.21,1.02) |

2.61 (-0.32,5.55) |

0.09 (-0.49,0.68) |

0.26 (0.04,0.47) |

-0.33 (-0.64,-0.01) |

| S.E. | 2.24 | 1.21 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 2.85 | 0.27 | 1.30 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.14 | |

| T | -1.20 | 1.54 | 1.43 | -0.01 | -0.21 | -2.32 | 0.01 | 1.48 | 2.01 | 0.35 | 2.64 | -2.35 | |

| p-value | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.046 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.075 | 0.73 | 0.027 | 0.044 | |

|

25(OH)D (< 30 ng/ml) |

β (95% CI) |

0.97 (-2.68 ,4.61) |

-1.20 (-3.17,0.77) |

0.32 (-0.37,1.00) |

0.70 (0.07,1.34) |

0.53 (-1.27, 2.33) |

-2.04 (-3.39,-0.69) |

-0.91 (-5.54,3.72) |

0.26 (-0.18 ,0.70) |

1.81 (-0.30,3.92) |

-0.30 (-0.72, 0.12) |

-0.06 (-0.22, 0.10) |

0.43 (0.20,0.66) |

| S.E. | 1.61 | 0.87 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 2.05 | 0.2 | 0.93 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.1 | |

| T | 0.6 | -1.38 | 1.04 | 2.5 | 0.67 | -3.41 | -0.44 | 1.33 | 1.94 | -1.62 | -0.88 | 4.28 | |

| p-value | 0.56 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.034 | 0.52 | 0.0077 | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.084 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).