Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

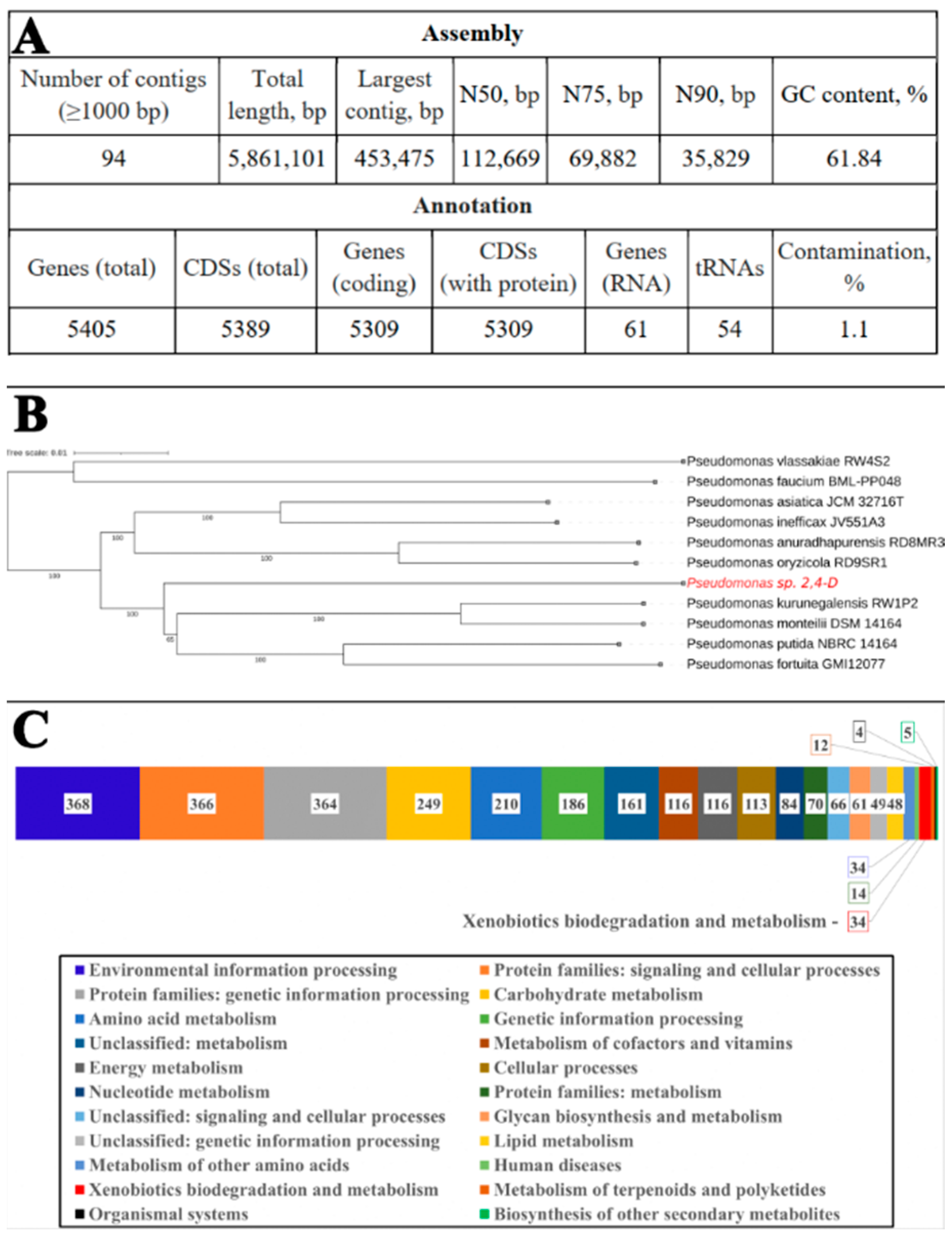

3.1. Identification of the Strain 2,4-D and Functional Annotation of Its Genome

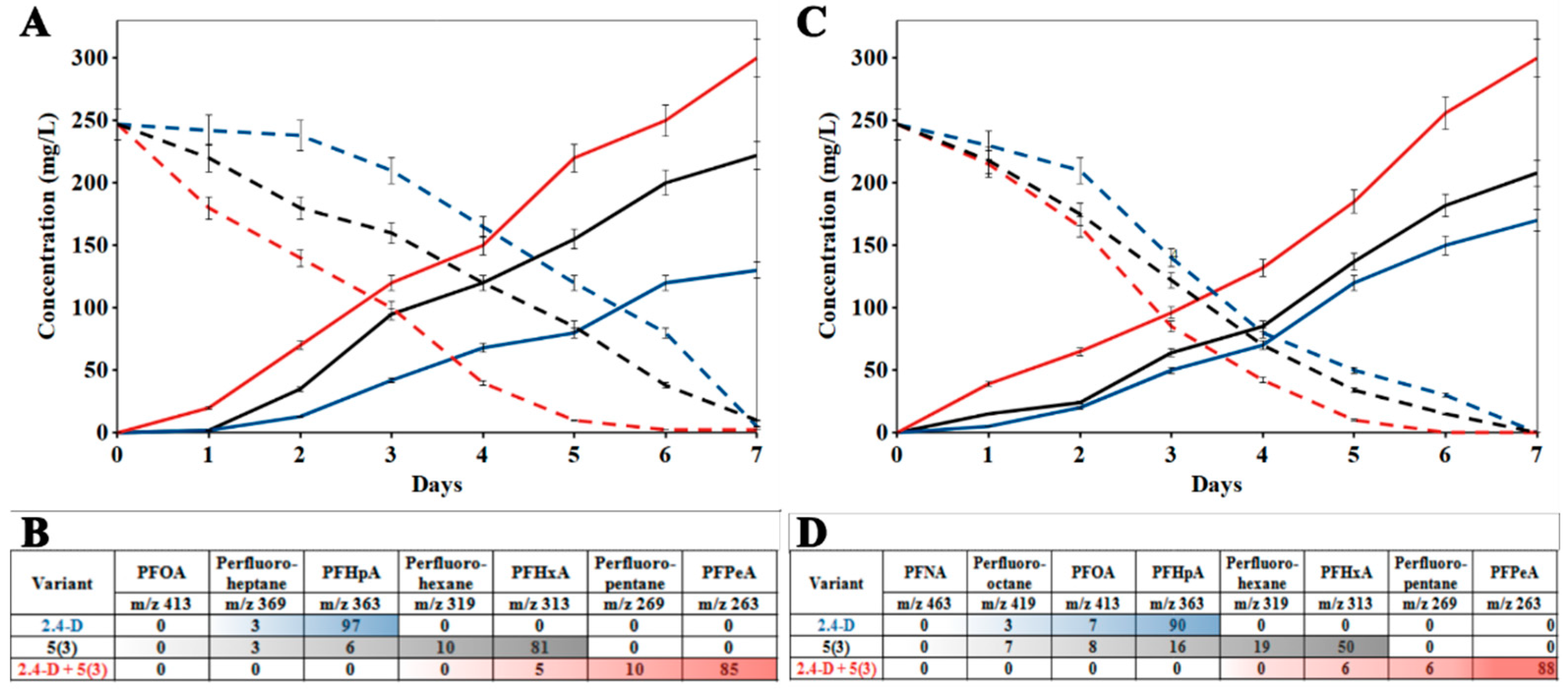

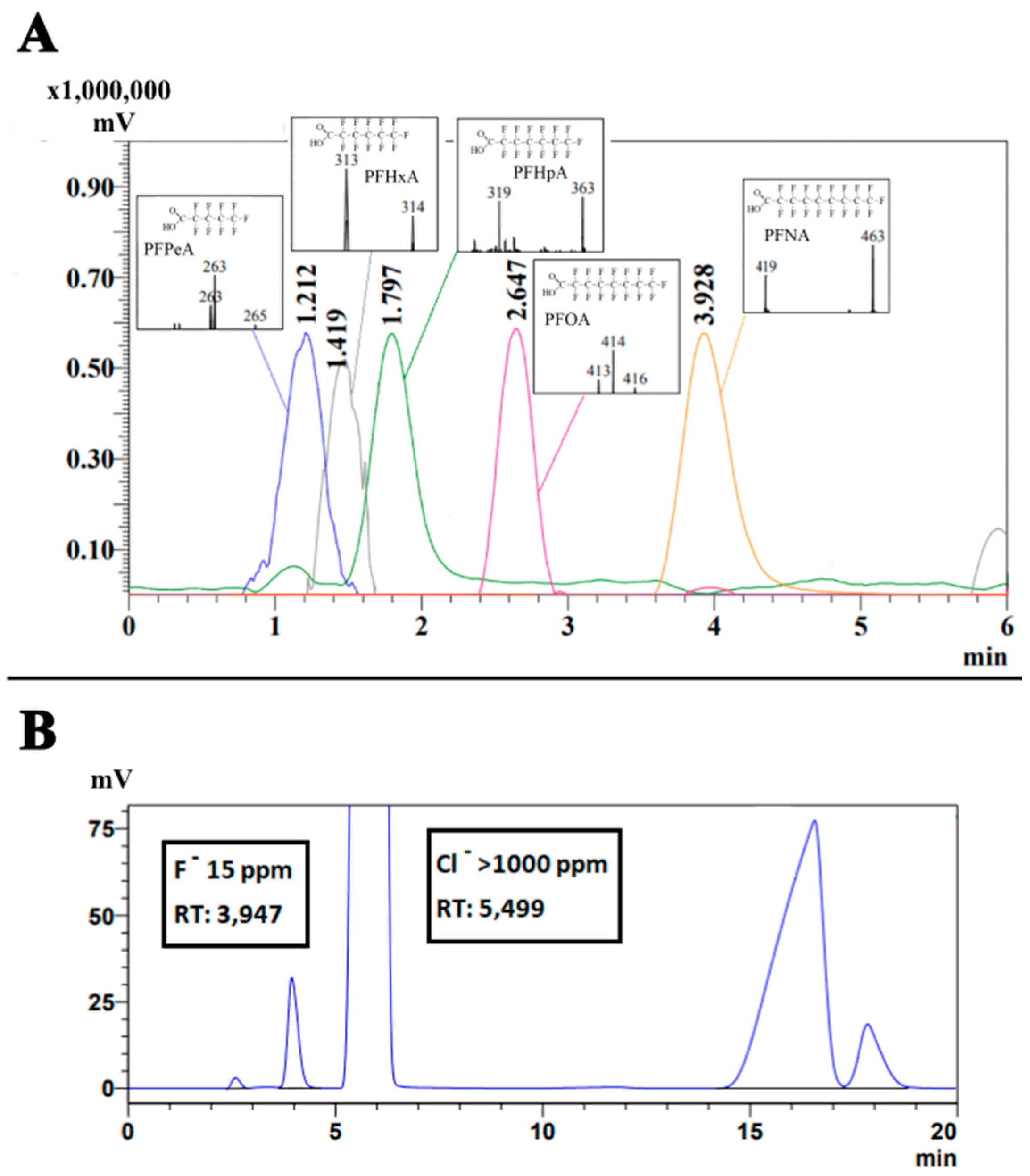

3.2. Biodegradation and Defluorination of PFCA

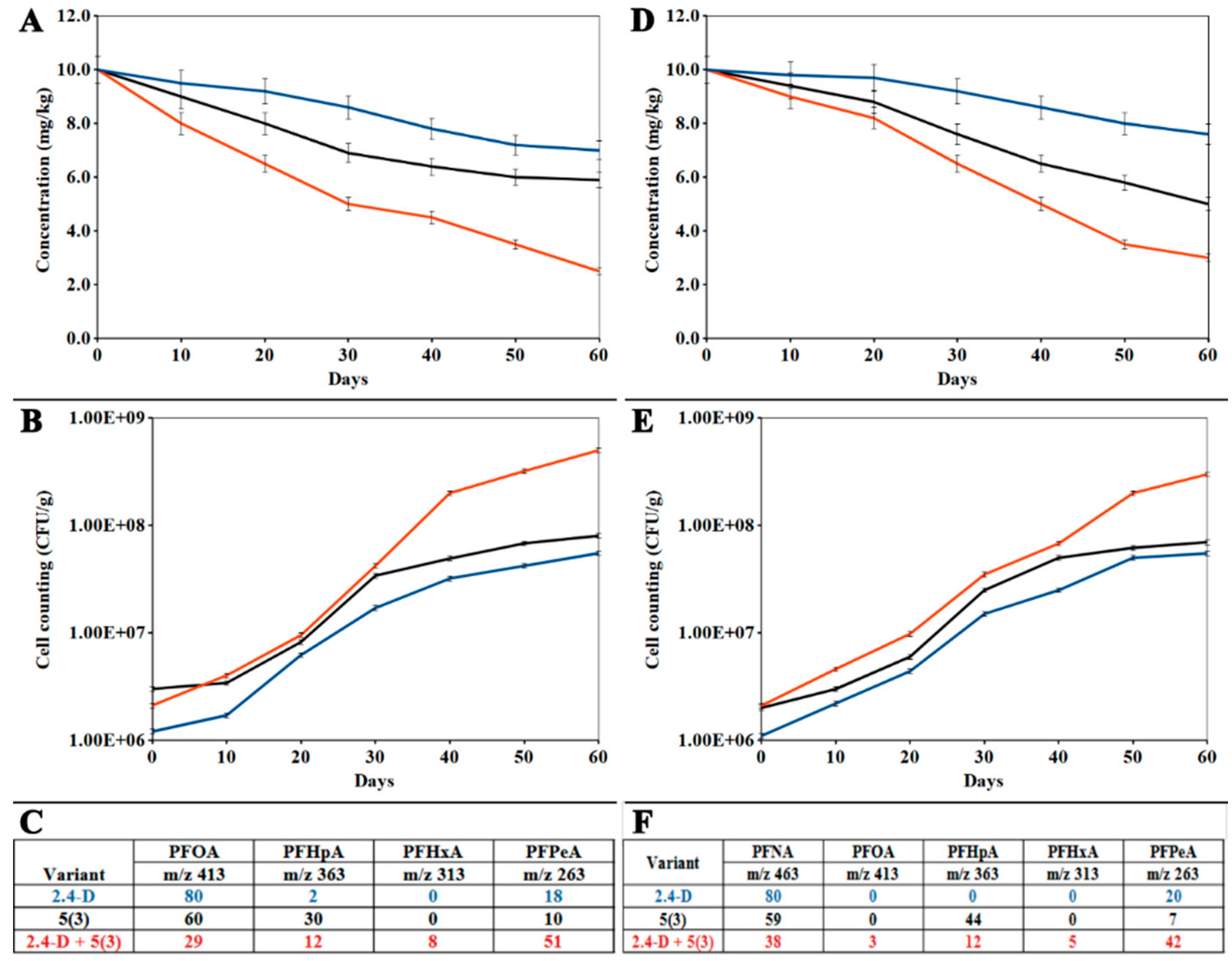

3.3. Model Experiment on Bioaugmentation of PFCA-Contaminated Soil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baggi, G.; Bernasconi, S.; Zangrossi, M.; Cavalca, L.; Andreoni, V. Co-metabolism of di- and trichlorobenzoates in a 2-chlorobenzoate-degrading bacterial culture: Effect of the position and number of halo-substituents. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2008, 62, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Groffen, T.; Wepener, V.; Malherbe, W.; Bervoets, L. Distribution of perfluorinated compounds (PFASs) in the aquatic environment of the industrially polluted Vaal River, South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1334–1344. [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.-M.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liang-Ying, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, F.; Zeng, E.Y. Global distribution of perfluorochemicals (PFCs) in potential human exposure source–A review. Environ. Int. 2017, 108, 51–62. [CrossRef]

- Toms, L.M.L.; Br€aunig, J.; Vijayasarathy, S.; Phillips, S.; Hobson, P.; Aylward, L.L.; Kirk, M.D.; Mueller, J.F. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Australia: current levels and estimated population reference values for selected compounds. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2019, 222, 387–394. [CrossRef]

- Prevedouros, K.; Cousins, I.T.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H. Sources, fate and transport of perfluorocarboxylates. Environ Sci Technol. 2006, 40 (1), 32–44. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, J. Immunotoxic effects of perfluorononanoic acid on BALB/c mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 105(2), 312–21. [CrossRef]

- Coperchini, F.; Croce, L.; Ricci, G.; Magri, F.; Rotondi, M.; Imbriani, M.; Chiovato, L. Thyroid Disrupting Effects of Old and New Generation PFAS. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 612320. [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Human exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) through drinking water: A review of the recent scientific literature. Environ Res. 2019, 177, 108648. [CrossRef]

- Peritore, A.F.; Gugliandolo, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Crupi, R.; Britti, D. Current Review of Increasing Animal Health Threat of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Harms, Limitations, and Alternatives to Manage Their Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(14), 11707. [CrossRef]

- Post, G.B.; Cohn, P.D.; Cooper, K.R. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), an emerging drinking water contaminant: a critical review of recent literature. Environ Res. 2012, 116, 93-117. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Q.; Sheng, N.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Dai, J. Worldwide Distribution of Novel Perfluoroether Carboxylic and Sulfonic Acids in Surface Water. Environ Sci Technol. 2018, 52(14), 7621-7629. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Qian, J.; Huang, S.; Li, Q.; Guo, L.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Yang, J. Occurrence, distribution, and input pathways of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in soils near different sources in Shanghai. Environ Pollut. 2022, 308, 119620. [CrossRef]

- Sim, W.; Park, H.; Yoon, J.K.; Kim, J.I.; Oh, J.E. Characteristic distribution patterns of perfluoroalkyl substances in soils according to land-use types. Chemosphere. 2021, 276, 130167. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, J.; Li, P. Exposure routes, bioaccumulation and toxic effects of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) on plants: A critical review. Environ Int. 2022, 158, 106891. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, D.; Hu, G.; Li, Y.; Ni, Z.; Lin, Q.; Wang, S.; Qiu, R. Crop Contamination and Human Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances around a Fluorochemical Industrial Park in China. Toxics. 2024, 12(4), 269. [CrossRef]

- Report of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants on the Work of Its Fourth Meeting, 4–8 May//UNEP/POPS/COP.4/38; Stockholm Convention Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 66–69.

- Cheng, J.; Vecitis, C.D.; Park, H.; Mader, B.T.; Hoffmann, M.R. Sonochemical degradation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in landfill groundwater: environmental matrix effects. Env. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8057–8063. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shih, K.; Lu, X.; Liu, C. Mineralization behavior of fluorine in perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) during thermal treatment of lime-conditioned sludge. Env. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2621–2627. [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, S.; Navarro, D.A.; Hamad, S.A.; Grimison, C.; Higgins, C.P.; Mueller, J.F.; Kookana, R.S.; McLaughlin, M.J. Physical and chemical properties of carbon-based sorbents that affect the removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from solution and soil. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162653. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.S.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. A review on the advancement in photocatalytic degradation of poly/perfluoroalkyl substances in water: Insights into the mechanisms and structure-function relationship. Sci Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174137. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, He S, Yang Y, Yao B, Tang Y, Luo L, Zhi D, Wan Z, Wang L, Zhou Y. A review on percarbonate-based advanced oxidation processes for remediation of organic compounds in water. Environ Res. 2021, 200, 111371. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, L.; Xue, J.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Z.; Wu, L.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Z. Persulfate-based degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in aqueous solution: Review on influences, mechanisms and prospective. J Hazard Mater. 2020, 393, 122405. [CrossRef]

- Marquínez-Marquínez, A.N.; Loor-Molina, N.S.; Quiroz-Fernández, L.S.; Maddela, N.R.; Luque, R.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M. Recent advances in the remediation of perfluoroalkylated and polyfluoroalkylated contaminated sites. Environmental Research. 2023, 219, 115152. [CrossRef]

- Wackett, L.P.; McMahon, K. Why Is the biodegradation of polyfluorinated compounds so rare? mSphere. 2021, 6(5): Article e00721–21. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Urigüen, M.; Shuai, W.; Huang, S.; Jaffé, P.R. Biodegradation of PFOA in microbial electrolysis cells by Acidimicrobiaceae sp. strain A6. Chem. 2022, 292, 133506. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Jaffé, P.R. Defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) by Acidimicrobium sp. Strain A6. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53(19), 11410–11419. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Ren, C.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Liu, J.; Men, Y. Microbial cleavage of C-F bonds in two C6 Per- and polyfluorinated compounds via reductive defluorination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54(22), 14393–14402. [CrossRef]

- Chetverikov, S.P.; Sharipov, D.A.; Korshunova, T.Y.; Loginov, O.N. Degradation of perfluorooctanyl sulfonate by strain Pseudomonas plecoglossicida 2.4-D. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2017, 53 (5), 533–538. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sarkar, D.; Biswas, J.K.; Datta, R. Biodegradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126223. [CrossRef]

- Chetverikov, S.; Hkudaygulov, G.; Sharipov, D.; Starikov, S.; Chetverikova, D. Biodegradation Potential of C7-C10 Perfluorocarboxylic Acids and Data from the Genome of a New Strain of Pseudomonas mosselii 5(3). Toxics. 2023, 11(12), 1001. [CrossRef]

- Mothersole, R.G.; Mothersole, M.K, Goddard, H.G.; Liu, J.; Van Hamme, J.D. Enzyme Catalyzed Formation of CoA Adducts of Fluorinated Hexanoic Acid Analogues using a Long-Chain acyl-CoA Synthetase from Gordonia sp. Strain NB4-1Y. Biochemistry. 2024, 63(17), 2153–2165. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B.G.; Lim, H-J.; Na, S-H.; Choi, B-I.; Shin, D-S.; Chung, S-Y. Biodegradation of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) as an emerging contaminant. Chemosphere. 2014, 109, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Tang, C.; Peng, Q.; Peng, Q.; Chai, L. Draft genome sequence of perfluorooctane acid-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas parafulva YAB-1. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00935–e00915. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Gross, M.; Kemball, J.; Farajollahi, S.; Dennis, P.; Sitko, J.; Steel, J.J.; Almand, E.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Varaljay, V.A. Draft Genome Sequence of the Bacterium Delftia acidovorans Strain D4B, Isolated from Soil. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2021, 10(44), e0063521. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Scott, C. Toward the development of a molecular toolkit for the microbial remediation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024, 90(4), e0015724. [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, A.; Mutanda, I.; Taolin, J.; Qaria, M.A.; Yang, B.; Zhu, D. A review of microbial degradation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Biotransformation routes and enzymes. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 859(Pt 1), 160010. [CrossRef]

- Khusnutdinova, A.N.; Batyrova, K.A.; Brown, G.; Fedorchuk, T.; Chai, Y.S.; Skarina, T.; Flick, R.; Petit, A.P.; Savchenko, A.; Stogios, P.; Yakunin, A.F. Structural insights into hydrolytic defluorination of difluoroacetate by microbial fluoroacetate dehalogenases. FEBS J. 2023, 290(20), 4966–4983. [CrossRef]

- Farajollahi, S.; Lombardo, N.V.; Crenshaw, M.D.; Guo, H.B.; Doherty, M.E.; Davison, T.R.; Steel, J.J.; Almand, E.A.; Varaljay, V.A.; Suei-Hung, C.; Mirau, P.A.; Berry, R.J.; Kelley-Loughnane, N.; Dennis, P.B. Defluorination of Organofluorine Compounds Using Dehalogenase Enzymes from Delftia acidovorans (D4B). ACS Omega. 2024, 9(26), 28546–28555. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.D.; Coon, C.M.; Doherty, M.E.; McHugh, E.A.; Warner, M.C.; Walters, C.L.; Orahood, O.M.; Loesch, A.E.; Hatfield, D.C.; Sitko, J.C.; Almand, E.A.; Steel, J.J. Engineering and characterization of dehalogenase enzymes from Delftia acidovorans in bioremediation of perfluorinated compounds. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2022, 7(2), 671–676. [CrossRef]

- Jaffé, P.R.; Huang, S.; Park, J.; Ruiz-Urigüen, M.; Shuai, W.; Sima, M. Defluorination of PFAS by Acidimicrobium sp. strain A6 and potential applications for remediation. Methods Enzymol. 2024, 696, 287–320. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, R.L. Microbial oxidation of n-paraffinic hydrocarbons. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 1961, 2, 23–54.

- Bertani, G. Studies on lysogenesis I. J. Bacteriol. 1951, 62, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol:chloroform. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2006, 2006(1), pdb.prot4455. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, F.; Wu, J.; Zou, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, B. HTQC: A fast quality control toolkit for Illumina sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 33. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30(15), 2114–20. [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.; Nikolenko, S.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.; Pyshkin, A.; Sirotkin, A.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M.A.; Pevzner, P.A. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J.; Young, S.K.; Earl, A.M. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e112963. eCollection 2014. [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012, 9, 357–359. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Lim, J.M.; Kwon, S.J.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2017, 110(10), 1281–1286. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: a database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acid Res. 2022, 50(D1), D801–D807. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Desper, R.; Gascuel, O. FastME 2.0: A Comprehensive, Accurate, and Fast Distance-Based Phylogeny Inference Program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015; 32: 2798–2800. DOI:.

- Farris, J.S. Estimating phylogenetic trees from distance matrices. Am. Nat. 1972, 6, 645–667.

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Goker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Hahnke, R.L.; Petersen, J.; Scheuner, C.; Michael, V.; Fiebig, A.; Rohde, C.; Rohde, M.; Fartmann, B.; Goodwin, L.A.; Chertkov, O.; Reddy, T.; Pati, A.; Ivanova, N.N.; Markowitz, V.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Woyke, T.; Göker, M.; Klenk, H-P. Complete genome sequence of DSM 30083(T), the type strain (U5/41(T)) of Escherichia coli, and a proposal for delineating subspecies in microbial taxonomy. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2014, 9, 2. eCollection 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ouk Kim, Y.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. OrthoANI: An improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1100–1103. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.; Mabury, S.A.; Jenkins, T.M.; Washington, J.W. A North American and global survey of perfluoroalkyl substances in surface soils: Distribution patterns and mode of occurrence. Chemosphere. 2016, 161, 333-341. [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A.; Christensen, H.; Arahal, D.R.; da Costa, M.S.; Rooney, A.P.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.W.; De Meyer, S.; Trujillo, M.E. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 461–466. [CrossRef]

- Wackett, L.P. Pseudomonas: versatile biocatalysts for PFAS. Environ Microbiol. 2022, 24 (7), 2882-2889. [CrossRef]

- Calero, P.; Gurdo, N.; Nikel, P.I. Role of the CrcB transporter of Pseudomonas putida in the multi-level stress response elicited by mineral fluoride. Env Microbiol. 2022, 24(11), 5082–5104. [CrossRef]

- Haak, B.; Fetzner, S.; Lingens, F. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the plasmid-encoded genes for the two-component 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177(3), 667-75. [CrossRef]

- Eady, R.R. The vanadium-containing nitrogenase of Azotobacter. Biofactors. 1988, 1(2), 111-6.

- Llamas, A.; Leon-Miranda, E.; Tejada-Jimenez, M. Microalgal and Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterial Consortia: From Interaction to Biotechnological Potential. Plants. 2023, 12(13), 2476. [CrossRef]

- Beškoski, V.P., Yamamoto, A., Nakano, T., Yamamoto, K., Matsumura, C., Motegi, M., Beškoski, L.S., Inui, H. Defluorination of perfluoroalkyl acids is followed by production of monofluorinated fatty acids. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 636, 355-359. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z., Vogel, T.M., Wang, Q., Wei, C., Ali, M., Song, X. Microbial defluorination of TFA, PFOA, and HFPO-DA by a native microbial consortium under anoxic conditions. J Hazard Mater. 2024, 465, 133217. [CrossRef]

- Starikov, S.N., Hkudaygulov, G.G., Chetverikov, S.P. Isolation of perfluorocarboxylic acid dehalogenases from Pseudomonas plecoglossicida 2,4-D and Pseudomonas mosselii 5(3). Èkobioteh. 2024, 7 (3), 204-210. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M., da Fonseca, M.M., de Carvalho, C.C. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation strategies to improve the effectiveness of bioremediation processes. Biodegradation. 2011, 22(2), 231-41. [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.O., Pillay, D., Pillay, B. Biostimulation and bioaugmentation enhances aerobic biodegradation of dichloroethenes. Chemosphere. 2006, 63(4), 600-8. [CrossRef]

- Willmann, A., Trautmann, A.L., Kushmaro, A., Tiehm, A. Intrinsic and bioaugmented aerobic trichloroethene degradation at seven sites. Heliyon. 2023, 9(2), e13485. [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N., Sarkar, B., Yan, Y., Li, Q., Wijesekara, H., Kannan, K., Tsang, D.C.W., Schauerte, M., Bosch, J., Noll, H., Ok, Y.S., Scheckel, K., Kumpiene, J., Gobindlal, K., Kah, M., Sperry, J., Kirkham, M.B., Wang, H., Tsang. Y.F., Hou, D., Rinklebe, J. Remediation of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contaminated soils - To mobilize or to immobilize or to degrade? J Hazard Mater. 2021, 401, 123892. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).