Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analyzes and Reagents

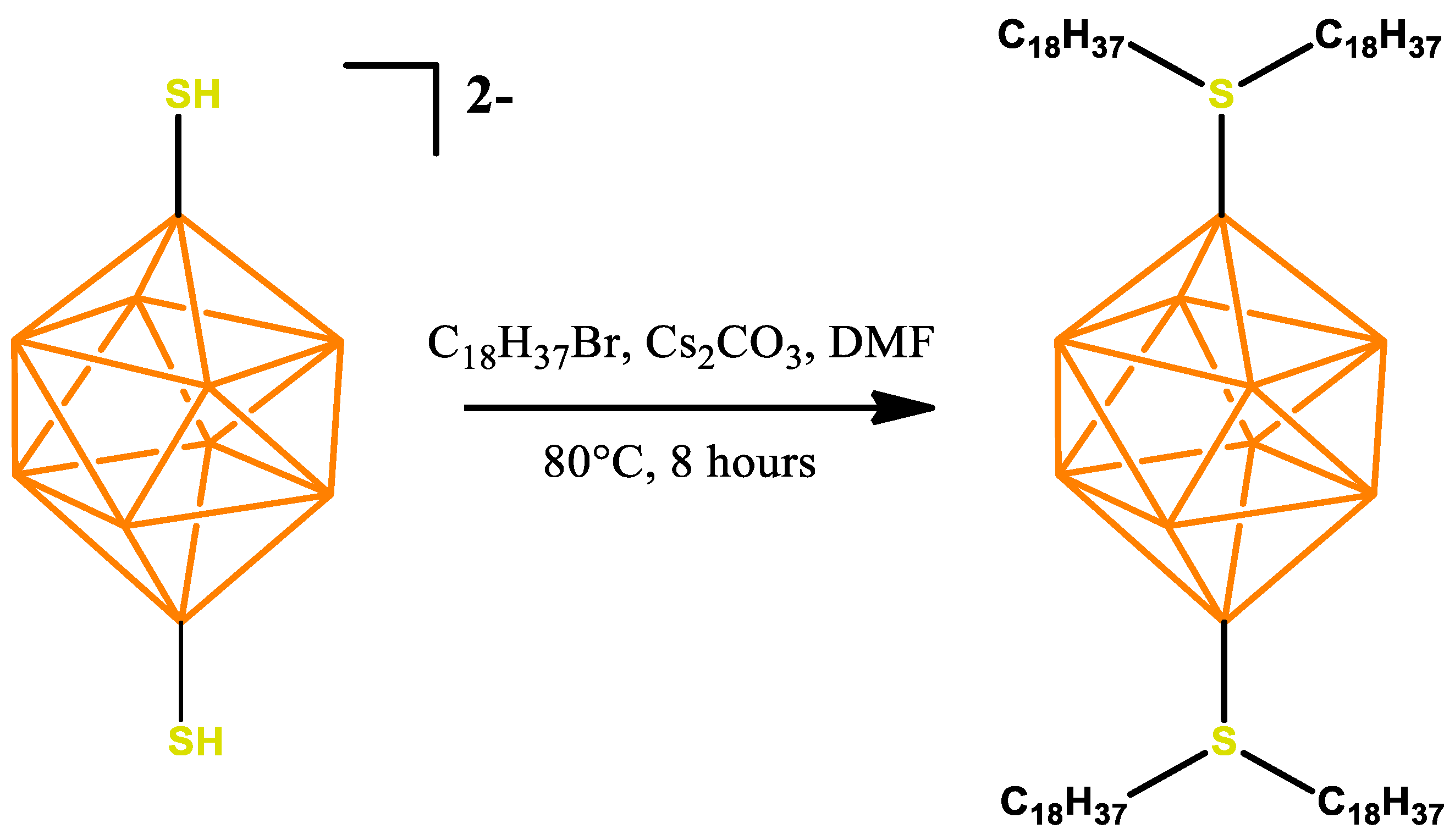

2.2. Synthesis of 1,10-B10H8(S(n-C18H37)2)2

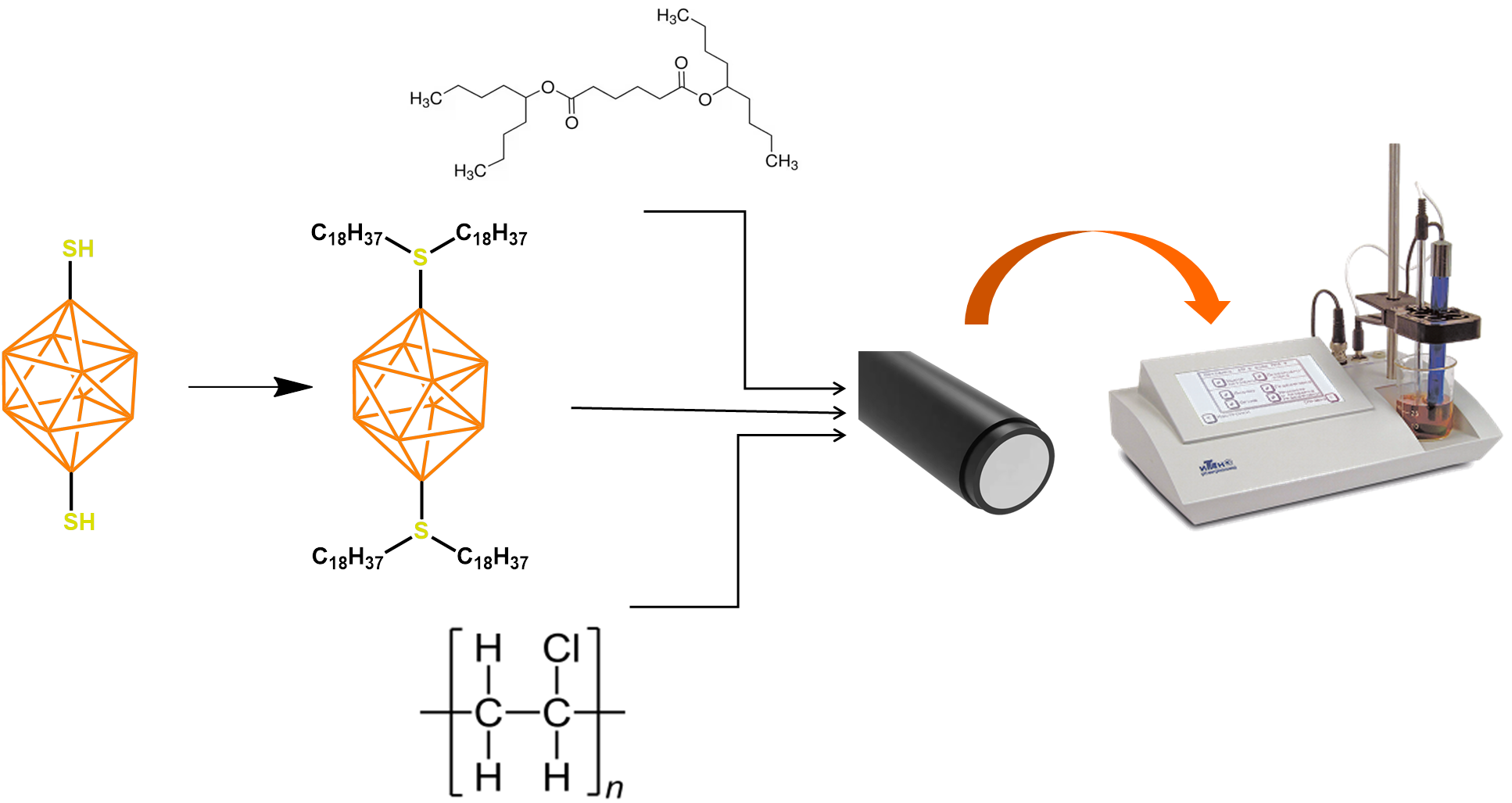

2.3. Manufacturing Membranes

2.4. Potentiometric Measurements

| Ag/AgCl | 1.0 mM terbinafine hydrochloride | PVC-membrane | Sample solution | AgClsatd, 3M KCl | AgCl/Ag |

3. Results

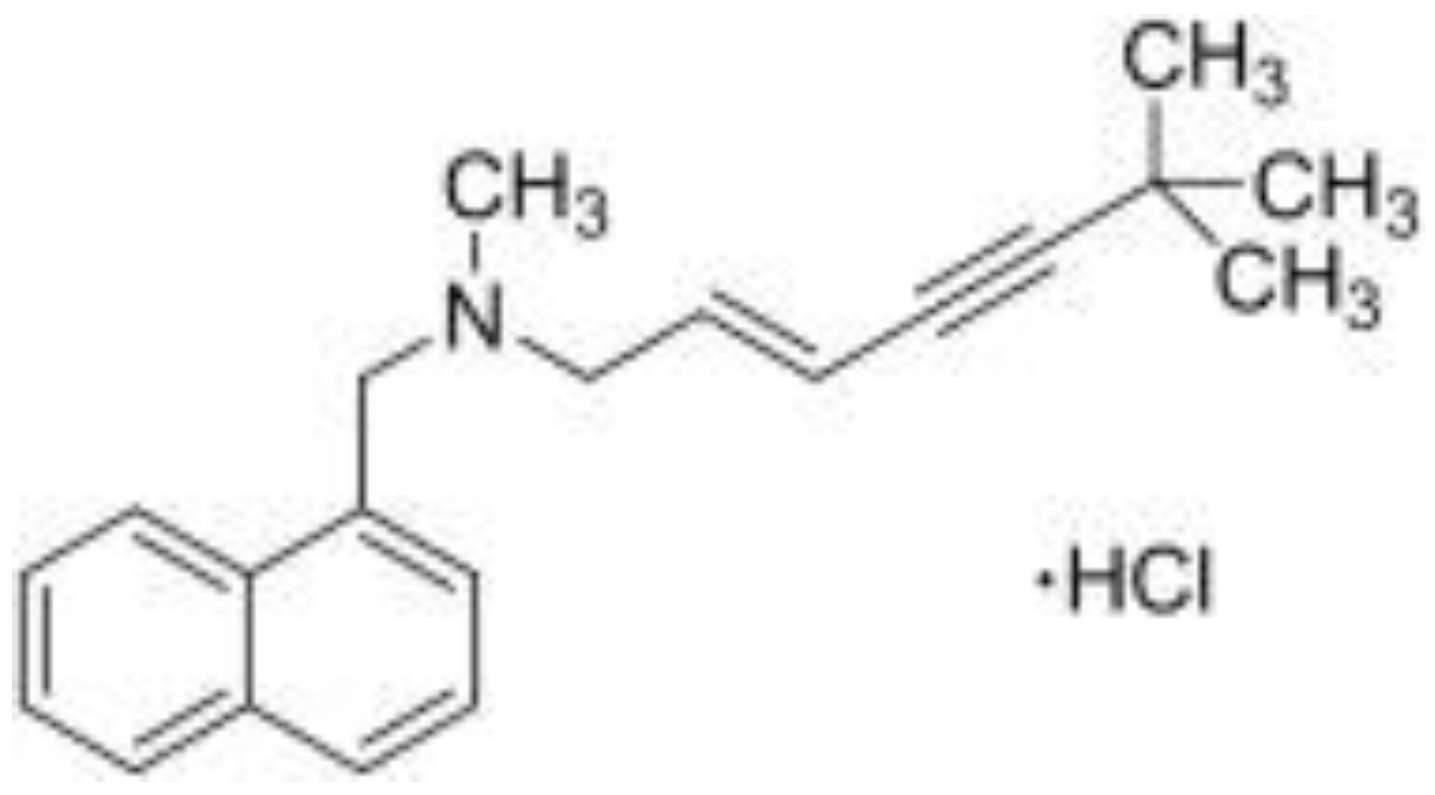

3.1. Synthesis of the Active Ingredient

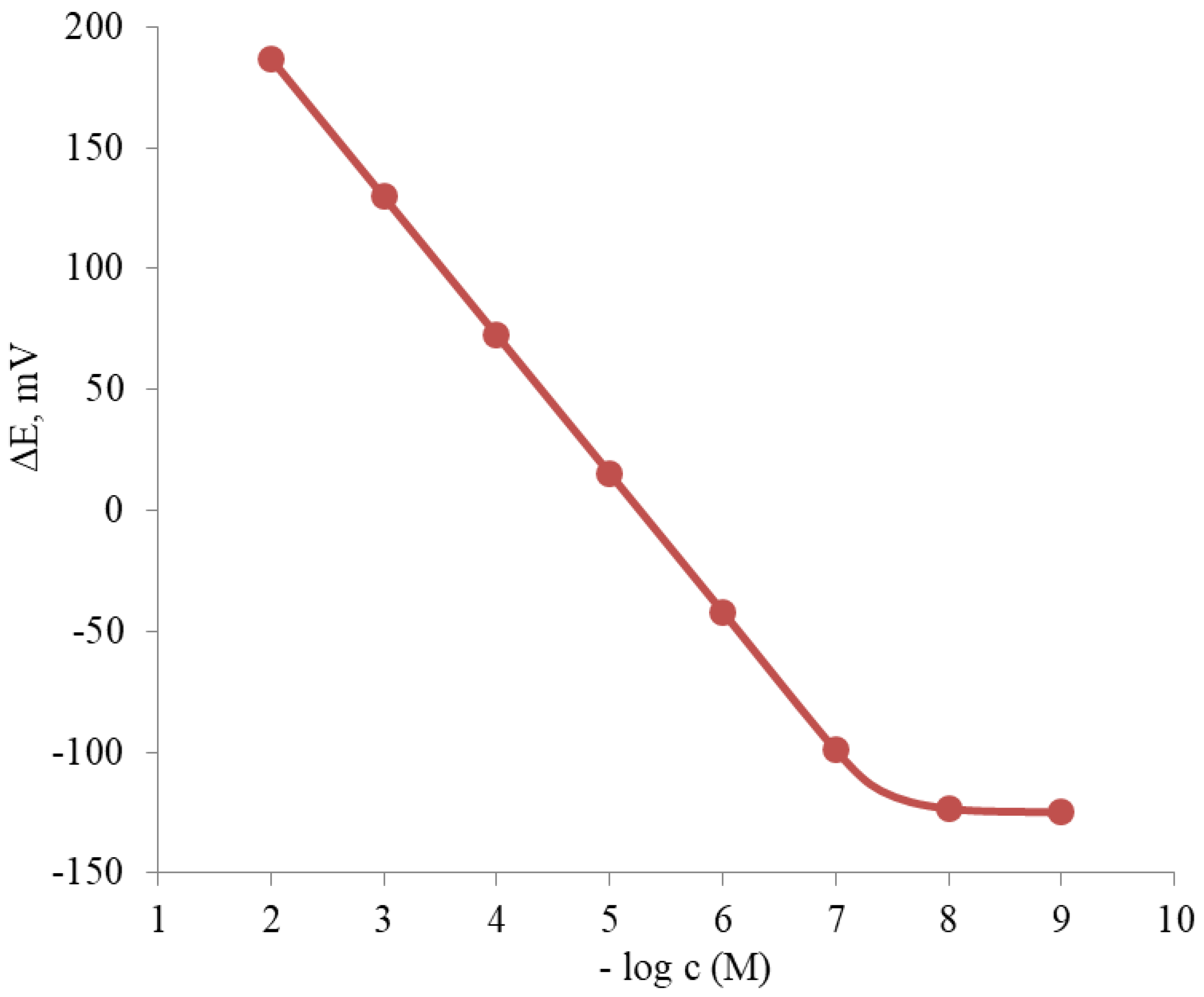

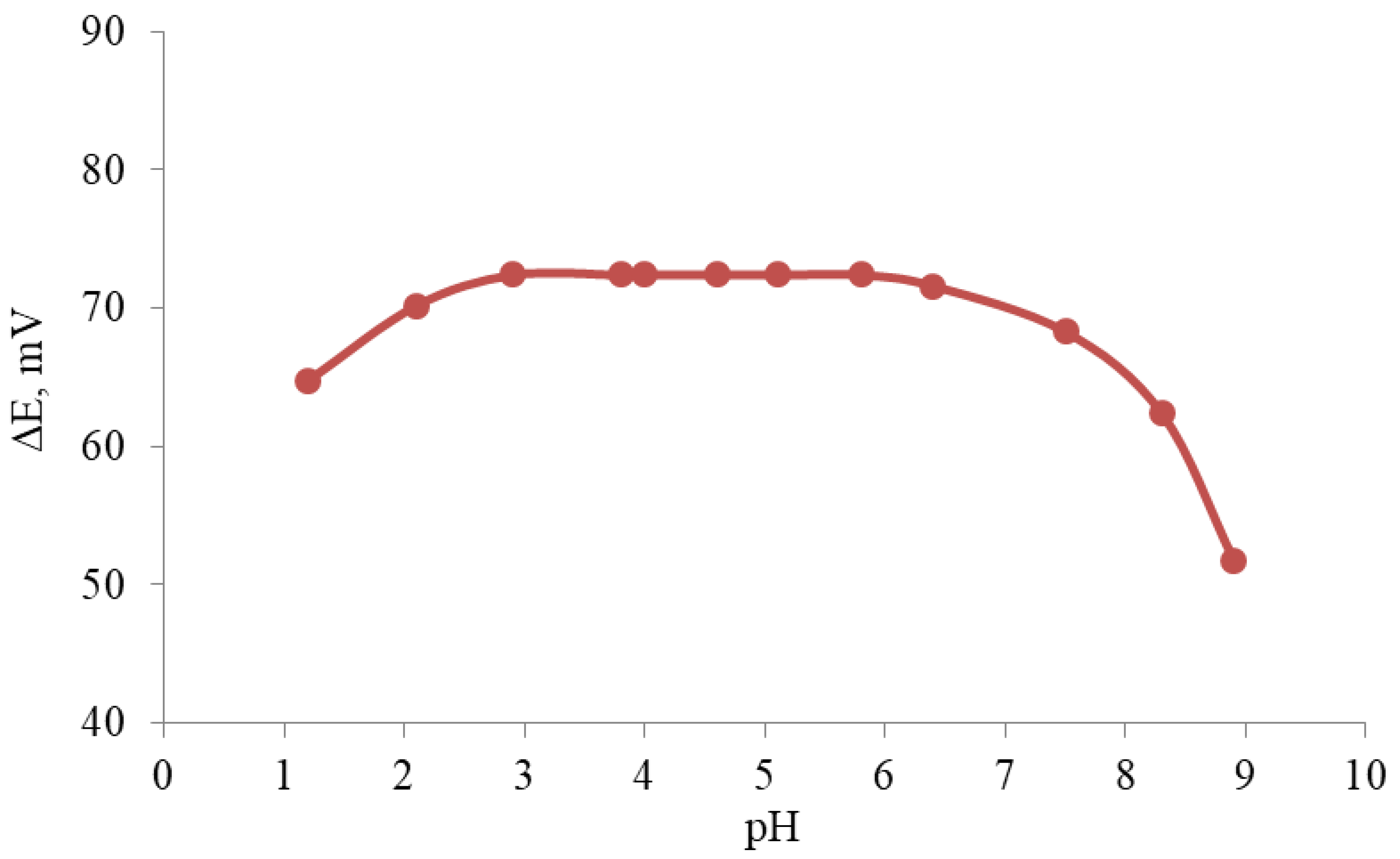

3.2. Ion Sensor Development

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- https://www.un.org/ru/global-issues/water.

- Agnew, C.; Anderson, E. Water Resources in the Arid Realm; Routledge: London, 2024; ISBN 9781003463917. [Google Scholar]

- Abramova, I.O. The Population of Africa under the Conditions of Transformation of the World Order. Her Russ Acad Sci 2022, 92, S1306–S1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, I.O.; Sharova, A.Yu. Geostrategic Risks in the Transition to Green Energies (Using the Example of Africa). Geology of Ore Deposits 2023, 65, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xia, Y.; Ti, C.; Shan, J.; Wu, Y.; Yan, X. Thirty Years of Experience in Water Pollution Control in Taihu Lake: A Review. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 914, 169821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Gao, G. Eutrophication Control of Large Shallow Lakes in China. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 881, 163494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Du, X.; Lei, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, H. Long-Term Variations of Water Quality and Nutrient Load Inputs in a Large Shallow Lake of Yellow River Basin: Implications for Lake Water Quality Improvements. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 900, 165776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrachek, E.; Bakker, E. Potentiometric Sensing. Anal Chem 2021, 93, 72–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartero, M.; Colozza, N.; Fernández-Pérez, B.M.; Crespo, G.A. Why Ammonium Detection Is Particularly Challenging but Insightful with Ionophore-Based Potentiometric Sensors – an Overview of the Progress in the Last 20 Years. Analyst 2020, 145, 3188–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Qin, W. Recent Advances in Potentiometric Biosensors. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 124, 115803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, R.L.; Amorim, C.G.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M.; Araújo, A.N. HPLC-Potentiometric Method for Determination of Biogenic Amines in Alcoholic Beverages: A Reliable Approach for Food Quality Control. Food Chem 2022, 372, 131288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyshev, E.S.; Kopytin, A. V.; Zhizhin, K.Y.; Kubasov, A.S.; Shpigun, L.K.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Potentiometric Quantitation of General Local Anesthetics with a New Highly Sensitive Membrane Sensor. Talanta 2022, 241, 123239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyshev, E.S.; Kubasov, A.S.; Golubev, A. V.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Potentiometric Method for Determining Biologically Non-Degradable Antimicrobial Substances. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2023, 68, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuetz, A.; Petranyi, G. Synthesis and Antifungal Activity of (E)-N-(6,6-Dimethyl-2-Hepten-4-Ynyl)-N-Methyl-1-Naphthalenemethanamine (SF 86-327) and Related Allylamine Derivatives with Enhanced Oral Activity. J Med Chem 1984, 27, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOODFIELD, M.J.D.; ROWELL, N.R.; FORSTER, R.A.; EVANS, E.G.V.; RAVEN, A. Treatment of Dermatophyte Infection of the Finger- and Toe-Nails with Terbinafine (SF 86-327, Lamisil), an Orally Active Fungicidal Agent. British Journal of Dermatology 1989, 121, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petranyi, G.; Ryder, N.S.; Stütz, A. Allylamine Derivatives: New Class of Synthetic Antifungal Agents Inhibiting Fungal Squalene Epoxidase. Science (1979) 1984, 224, 1239–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, N.S. Specific Inhibition of Fungal Sterol Biosynthesis by SF 86-327, a New Allylamine Antimycotic Agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985, 27, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly-Tonetti, N.; Legouffe, R.; Tomezyk, A.; Gumez, C.; Gaudin, M.; Bonnel, D.; Schaller, M. Penetration Profile of Terbinafine Compared to Amorolfine in Mycotic Human Toenails Quantified by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Imaging. Infect Dis Ther 2024, 13, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Yoshinouchi, T.; Okumura, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Mori, D.; Nakata, H.; Yasunaga, J.; Tanaka, Y. Antifungal Potency of Terbinafine as a Therapeutic Agent against Exophiala Dermatitidis in Vitro 2024.

- Viana, P.G.; Figueiredo, A.B.F.; Gremião, I.D.F.; de Miranda, L.H.M.; da Silva Antonio, I.M.; Boechat, J.S.; de Sá Machado, A.C.; de Oliveira, M.M.E.; Pereira, S.A. Successful Treatment of Canine Sporotrichosis with Terbinafine: Case Reports and Literature Review. Mycopathologia 2018, 183, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, Â.V.; Oliveira, J.C.; Costa de Medeiros, C.A.; Silva, S.L.; Pereira, F.O. Potentiation of Antifungal Activity of Terbinafine by Dihydrojasmone and Terpinolene against Dermatophytes. Lett Appl Microbiol 2021, 72, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, X.; Su, X.; Gao, W. The Preparation and Evaluation of a Hydrochloride Hydrogel Patch with an Iontophoresis-Assisted Release of Terbinafine for Transdermal Delivery. Gels 2024, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Hayes, J.; Hamill, M.; Martin, A.; Pistole, N.; Yarbrough, J.; Souza, M. Determining Terbinafine in Plasma and Saline Using HPLC. J Liq Chromatogr Relat Technol 2015, 38, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysová, L.; Solich, P.; Marek, P.; Havlíková, L.; Nováková, L.; Šícha, J. Separation and Determination of Terbinafine and Its Four Impurities of Similar Structure Using Simple RP-HPLC Method. Talanta 2006, 68, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Separovic, L.; Lourenço, F.R. Measurement Uncertainty Evaluation of an Analytical Procedure for Determination of Terbinafine Hydrochloride in Creams by HPLC and Optimization Strategies Using Analytical Quality by Design. Microchemical Journal 2022, 178, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Https://Www.Ijnrd.Org/Papers/IJNRD2401092.Pdf.

- Faridbod, F.; Ganjali, M.R.; Norouzi, P. Potentiometric PVC Membrane Sensor for the Determination of Terbinafine. Int J Electrochem Sci 2013, 8, 6107–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beshlawy, M.; Arida, H. Modified Screen-Printed Microchip for Potentiometric Detection of Terbinafine Drugs. J Chem 2022, 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rahman, M.K.A.; Sayed, R.A.; El-Masry, M.S.; Hassan, W.S.; Shalaby, A. Development of Potentiometric Method for In Situ Testing of Terbinafine HCl Dissolution Behavior Using Liquid Inner Contact Ion-Selective Electrode Membrane. J Electrochem Soc 2018, 165, B143–B149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterary, S.S.; Mostafa, G.A.E.; El-Tohamy, M.F.; Elhadi, A.M.; AlRabiah, H. A Novel Potentiometric Coated Wire Sensor Based on Functionalized Polymeric CaO/ZnO Nanocomposite Synthesized by Lavandula Spica Mediated Extract for Terbinafine Determination. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubasov, A.S.; Turishev, E.S.; Kopytin, A.V.; Shpigun, L.K.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Sulfonium Closo-Hydridodecaborate Anions as Active Components of a Potentiometric Membrane Sensor for Lidocaine Hydrochloride. Inorganica Chim Acta 2021, 514, 119992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, A. V.; Baltovskaya, D. V.; Kubasov, A.S.; Bykov, A.Yu.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Synthesis of 1,10-Disulfanyl-Closo-Decaborate Anion and Its Disulfonium Tetraacetylamide Derivative. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.P.; Lindner, E. Recommendations for Nomenclature of Ionselective Electrodes (IUPAC Recommendations 1994). Pure and Applied Chemistry 1994, 66, 2527–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzekpo, V.P.Y.; Christian, G.D. Determination of Selectivity Coefficients of Ion-Selective Electrodes by a Matched-Potential Method. Anal Chim Acta 1984, 164, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubasov, A.S.; Turishev, E.S.; Polyakova, I.N.; Matveev, E.Yu.; Zhizhin, K.Yu.; Kuznetsov, N.T. The Method for Synthesis of 2-Sulfanyl Closo -Decaborate Anion and Its S -Alkyl and S -Acyl Derivatives. J Organomet Chem 2017, 828, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion-Selective Electrodes in Analytical Chemistry; Freiser, H. , Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1978; ISBN 978-1-4684-2594-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bobacka, J.; Ivaska, A.; Lewenstam, A. Potentiometric Ion Sensors. Chem Rev 2008, 108, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Gordon Organic Chemistry of Electrolytes Solutions; Mir: Moscow, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Morf, W.E.; Lindner, Ernoe. ; Simon, Wilhelm. Theoretical Treatment of the Dynamic Response of Ion-Selective Membrane Electrodes. Anal Chem 1975, 47, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Active membrane ingredient | Linear range, M | LOD, M | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terbinafine screen-printed microchip modified with MWCNTs | 1.0 × 10-2 – 1.0 × 10-8 | 5.0 × 10-9 | [28] |

| Ion-pair Terbinafine and tetraphenyl borate functionalised CaO/ZnO | 1.0 × 10-2 – 7.0 × 10-6 | 6.5 × 10-6 | [27] |

| Sodium tetraphenylborate | 1.0 × 10-2 – 1.0 × 10-6 | 7.9 × 10−7 | [29] |

| Ion-pair Terbinafine and tetraphenyl borate functionalised CaO/ZnO | 1.0 × 10−2 – 5.0 × 10−9 | 2.5 × 10−10 | [30] |

| № | Membrane composition, % wt | Linear range, mol/L | Lower detection limit, mol/L | Slope, mV/decade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,10-B10H8(S(n-C18H37)2)2 | BBPA | PVC | ||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 70.0 | 29.0 | ≈10-8 – 10-2 | ≈5.0 × 10-9 | 60 ± 2 |

| 2 | 1.2 | 69.8 | 29.0 | ≈10-8 – 10-2 | ≈6.0 × 10-9 | 59 ± 1 |

| 3 | 1.4 | 69.6 | 29.0 | ≈2.0 × 10-8 – 10-2 | ≈7.0 × 10-9 | 58.2 ± 0.5 |

| 4 | 1.6 | 69.4 | 29.0 | ≈3.0 × 10-8 – 10-2 | ≈8.0 × 10-9 | 57.7 ± 0.3 |

| 5 | 1.8 | 69.2 | 29.0 | 4.0 × 10-8 – 10-2 | 1.0 × 10-8 | 57.2 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 69.0 | 29.0 | 8.0 × 10-8 – 10-2 | 3.0 × 10-8 | 55.9 ± 0.2 |

| 7 | 2.2 | 68.8 | 29.0 | 10-7 – 10-2 | 5.0 × 10-8 | 53.6 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | 2.4 | 68.6 | 29.0 | 3.0 × 10-7 – 10-2 | 7.0 × 10-8 | 52.3 ± 0.2 |

| Interfering cation | lgKpot Terbinafine/cation |

|---|---|

| Li+ | -4.12 |

| Na+ | -3.85 |

| K+ | -3.91 |

| Rb+ | -3.96 |

| Cs+ | -4.18 |

| Ca2+ | -4.64 |

| Sr2+ | -4.73 |

| Ba2+ | -5.02 |

| NH4+ | -3.29 |

| Glycine | -3.72 |

| Valine | -3.68 |

| β-Alanine | -3.52 |

| L, D- Tyrosine | -3.21 |

| tetrabutylammonium+ (TBA+) | -3.01 |

| Glucose | -4.75 |

| Fructose | -4.78 |

| Sucrose | -4.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).