1. Introduction

The brainstem nucleus Locus Coeruleus (LC) is involved in wide range of functions, including sensory processing, motor behavior, and cognition [

1,

2]. It contains one of the largest populations of norepinephrine (NE) neurons from different brain areas [

3]. The LC noradrenergic system provides widespread innervation to many brain structures of the CNS and affect cognitive processes in several key regions [

4]. It has been shown that LC activity is low during routine behaviors such as grooming or feeding, whereas its neurons respond with a phasic burst of activity to stimuli in all sensory modalities when they are novel. This type of activity leads to behavioral adaptation to the new context [

5,

6]. The reciprocal relationship between LC and prefrontal cortex (PFC) is thought to support this behavioral reorganization [

7,

8].

Catecholamines play an important role in human and animal behavior. Their wide distribution in the brain areas provides for a vast functional diversity. Studies of the interactions between the dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine systems in the CNS suggest that these systems may act in an overlapping and parallel manner [

9]. The correct balance of catecholamines in the brain is important for the proper organization of many types of behavior. The absence of this balance can lead to the development of various psychiatric disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [

10,

11,

12,

13].

It is believed that ADHD development mainly arise due to the dysfunction of the DA system [

14,

15]. Some cases of ADHD are linked to DNA damage in genes encoding protein transporters of dopamine (DAT) and norepinephrine (NET), which are located in the synaptic membrane and ensure the reuptake of released molecules for their next use [

16]. It was proposed that abnormalities in the DA and the NE systems may play the key role in ADHD development [

17,

18].

The rats with deletion of DAT gene (DAT-KO rats) were created as a valuable model for ADHD with emphasis on various aspects of DA system dysfunctions [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Rats lacking

SLC6A3, the DAT coding gene, were generated using zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) technology. DAT-KO rats are an animal model of persistently elevated extracellular DA levels [

22]. The knockout rats show marked behavioral abnormalities: impulsivity, stereotypy and reduced learning ability [

20,

23,

24,

25]. Such hyperdopaminergia is thought to be one of the causes of disorders such as schizophrenia, mania and ADHD [

21].

Chemogenetic tools have been widely used to explore brain function and connections between brain regions [

26,

27,

28]. This method relies on cell-specific viral delivery to express designer receptors that are exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD). This tool can activate specific neuronal pathways by applying the specific molecular ligand. Now, chemogenetic modulation of LC activity has been used to study sensorimotor integration and selective modulation of LC-PFC functional connectivity [

29,

30].

In this study, we evaluated the effect of activation of NE release in the PFC on the performance of a spatial behavior task in DAT-KO rats. An increase in NE levels was achieved by chemogenetic modulation of LC neuronal activity using the viral vector CAV-2. We used canine adenovirus type 2 (CAV2) – the viral vector carrying the noradrenergic cell-specific promoter, activated DREADDs (Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) to selectively activate LC-NA neurons in DAT-KO and wild-type (WT) rats. CAV2 (CAV-PRS-hM3Dq-mCherry) was injected into the PFC to retrogradely transduce LC neurons projecting to the PFC. After transduction, the neurons acquire DREADDs, and an increase in NE was achieved by chemogenetic modulation of LC neuronal activity using the specific ligand clozapine (Clz). After activation of LC NE neurons, the impact of NE enhancing on spatial task learning in the Hebb-Williams maze by DAT-KO and WT rats was investigated. We suggest that chemogenetic modulation causing an increase of NE levels in the PFC may alleviate hyperactivity and cognitive deficits of hyperdopaminergic DAT-KO rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

32 DAT-KO and 32 WT littermate rats, males and females of the age 4 months, were used in the experiments. Our observations have shown that there are no significant differences in behavior between the sexes. Therefore, due to the limited number of DAT-KO males, 3 female rats of both genotypes were added to each group. To analyze the effects of chemogenetic modulation of LC neurons, a group of DREADD-expressing animals (8 DAT-KO and 8 WT) and a control group of rats that did not receive CAV2 microinjection (8 DAT-KO and 8 WT) were formed.

All experimental procedures were conducted in compliance with requirements regarding the care and treatment of laboratory animals and the Ethics committee of Saint Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia (protocol No. 131-03-10 of 22 November 2021). Before the experiments, rats were maintained in IVC cages (RAIR IsoSystem World Cage 500; Lab Products, Inc.) with free access to food (BioPro, Russia) and water, at a temperature of 22±1 degrees C, 50–70% relative humidity and a 12 h light/dark cycle (light from 9 am). Experiments were carried out between 1 pm and 5 pm.

2.2. Viral Vector Microinjection

For transduction of LC noradrenergic neurons, microinjection of viral vector into PFC was performed. Microinjection of viral vectors into the PFC was used for transduction of LC NE neurons. The CAV-2-carrying DREADD coupled to the mCherry sequence (CAV PRS hM3D(Gq)-mCherry, 2.5 x 10^12 particles/ml; PVM, Montpellier) was used. To ensure the vitality of virus particles they were stored at -80 °C and were defrosted only immediately before injection.

8 DAT-KO and 8 WT rats were anaesthetized using Isoflurane gas anesthesia (1000 mg/g Innalation vapor, Chemical Iberica Produktos Veterinarios, Croatia). CAV PRS hM3D(Gq)-mCherry was injected 600nl each into the left and right PFC. Microinjection coordinates were AP: +3.0 mm, ML: ± 0.8 mm. The virus dose was divided into three depth points: -3.6, -3.4, -3.2. The vector-containing substance was delivered using a microsyringe pump (UMC4 MicroSyringe Pump Controller, World Precision Instruments) at 150 nl/min. A syringe (Hamilton 701 RN Syringe, 10mcl) with a glass microcapillary nozzle made on a puller (Narishige PC-100) was placed in the pump. The glass microcapillary was lowered to -3.6 and then raised to the next injection point, pumping in 200 nL at a time.

After surgery, the animals were given the necessary post-operative care. Over the next 6 weeks, the rats recovered and the viral vector retrogradely transduced via NE neurons into the LC. The control groups of rats (8 DAT-KO and 8 WT) did not receive virus microinjection.

2.3. Hebb-Williams Maze Apparatus and Experimental Setup

The Hebb-Williams maze, which consists of a set of internal walls to create different maze configurations within an enclosed arena, was chosen for behavioral testing [

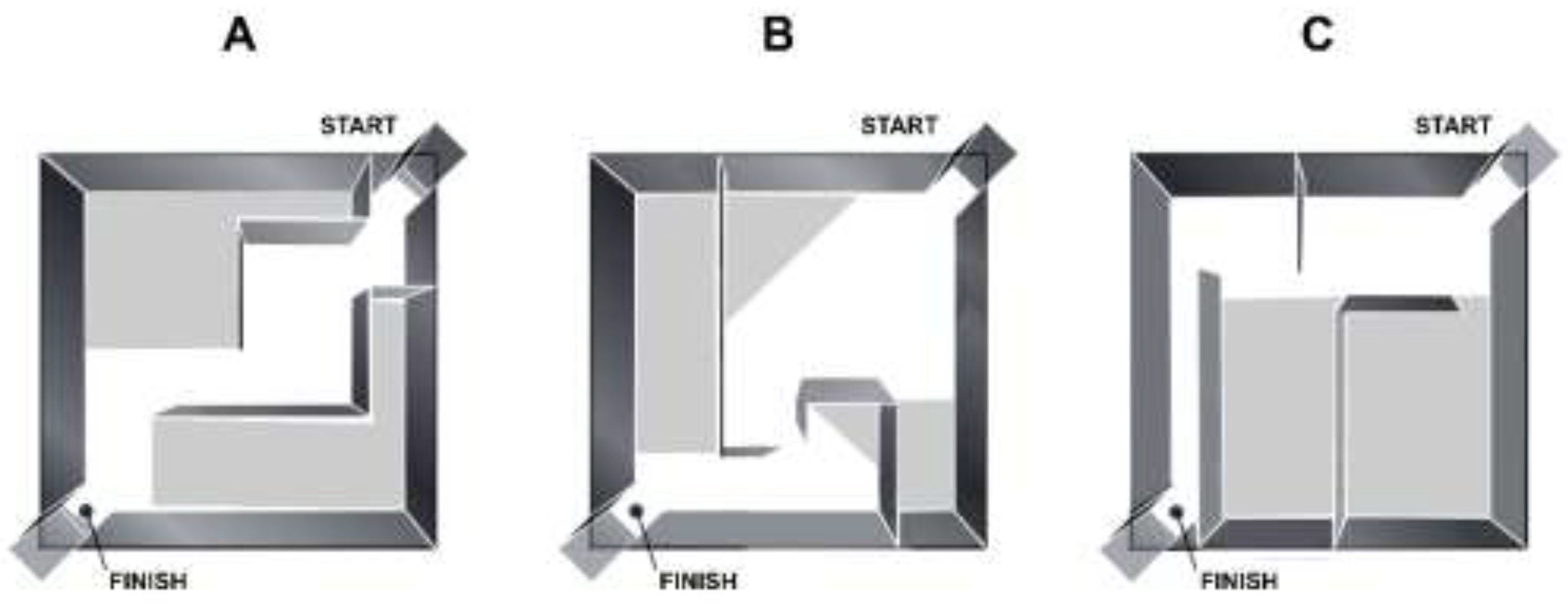

31]. The arena represents a 75x75 cm square platform surrounded by 25cm walls. The start and finish chambers were located at opposite corners. The inner walls can be placed in different configurations to create the correct path as well as the error zones. Animals need to learn to find the way through the maze from start to finish to obtain a food reward (

Figure 1). For 5 days prior to training and throughout the experiment, the rats were given food at 90% of their normal diet to create food motivation. Popcorn loops (Nestlé, S.A., weight 0.2 g) were used as a reward. Each animal was weighed daily before and throughout the experiment. Animals were handled in the experimental room to habituate them to experiment conditions.

The behavior of two groups of rats was accessed: rats expressing DREADD (8 KO + 8 WT) and control group of rats without DREADD (8 KO + 8 WT). For female rats (3 females in each group), the estrous cycle was monitored, and behavioral testing was not performed on days of the proestrus phase.

On the first day animals were placed into the arena without inner walls to familiarize them with the setup. Then rats were trained in the “learning” arena configuration for three days (

Figure 1A). Each day animals were given three trials to complete the task. On the fourth experimental day, the arena configuration was changed, and the animals began receiving intraperitoneal injections 30 min before the experimental session. In the new maze configuration (

Figure 1B), rats were trained after vehicle i.p. injection. After three days, the animals were tested in the following maze configuration (

Figure 1C) after i.p. injection of Clz (1mg/kg in 0,0001M HCL solution).

Video was acquired from the camera mounted above the maze and the behavioral variables were analyzed with software EthoVision XT11.5 (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA). Following characteristics were chosen to analyze: distance travelled, time spent on task completion, number of errors, and return runs.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Neurons transduced by a viral vector had a DREADD receptor on their membrane coupled to mCherry, a fluorescent reporter protein. At the end of the experiment, we verified accuracy of virus injections and evaluated the number of neurons transduction in LC. Animals were deeply anesthetized with a mix of 200 mg/kg Zoletil with 16 mg/kg Xylazine, then transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl (100ml) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, 100 ml) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Extracted brain tissue was placed for 24 hours in PFA for post-fixation at room temperature (RT). The brains were placed in increasing concentration sucrose solutions for cryoprotection. Then, 50 μm frontal free-floating sections of LC were prepared on a cryostat Leica CM-3050S. The sections were stored in 0,1% NaN3 at +4 °C.

To assess the number of NE neurons transduced by viral vector we performed the procedure of double immunostaining. After being washed in PBS, the sections were processed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval and blocked with 5% Normal Goat Blocking Buffer (Elabscience, E-IR-R111) for 1,5 h at RT. Then, the sections were incubated in the primary antibodies: mouse anti-DβH antibody (1:2000, MAB308, Chemicon) and rabbit anti-mCherry antibody (1:1000 Cat#632496, Takara Bio, USA) [

32] for 24h at RT, and the secondary antibody: donkey anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500, abcam, ab150105, UK) and CyTM3 AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:800, AB_2307443, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, USA) for 2 h at 37 °C. Finally, the sections were mounted in aqueous medium Fluoroshield with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat # F6057, United States).

Stained sections were imaged on fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI6000 objective 10x) with a build-in 8MP CCD color digital camera. mCherry- and DβH-positive neurons were counted manually with Fiji ImageJ software [

33]. To evaluate the scale in which virus had transduced LC neurons, the percentage of mCherry+ neurons to DβH+ neurons was calculated.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All values were averaged over all trials for 3 days per animal, and then groups of rats were compared. The recorded parameters were averaged over all trials for 3 days for each animal and then the groups of rats were compared. The normality of the distribution was preliminarily assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We used a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), analyzing the genotype factor (DAT-KO or WT) and the treatment factor (saline of Clz administration) with Fisher’s LSD post-test for groups comparison. The t-test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used for the comparison of the mean values. All calculations were performed in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Hebb-Williams Maze

The rats in the experimental group received the microinjection of the virus carried artificial receptors (DREADD+ group) on the membrane of LC neurons that were only activated by the specific ligand Clz. The i.p. injection of vehicle did not affect their activity. Therefore, we compared the behavioral parameters of rats in the Hebb-Williams maze after i.p. injection of vehicle or Clz (DREADD activator). A control group of animals did not receive CAV2 microinjection (DREADD- group). In this group of rats, we also compared the behavioral parameters of the rats after i.p. injection of vehicle or Clz to verify that the differences found were not due to the effect of Clz per se.

The hyperactive behavior of DAT-KO rats has been shown in a large number of publications [

22,

23,

24,

34,

35,

36,

37]. A comparison of the behavior of DAT-KO and WT rats in the present study also supports this observation. The results of the experiments showed that the distance travelled by DAT-KO rats was significantly greater than in WT rats (911,6±198,1 in DAT-KO versus 297,7±23,4; p<0.001, Mann Whitney test,

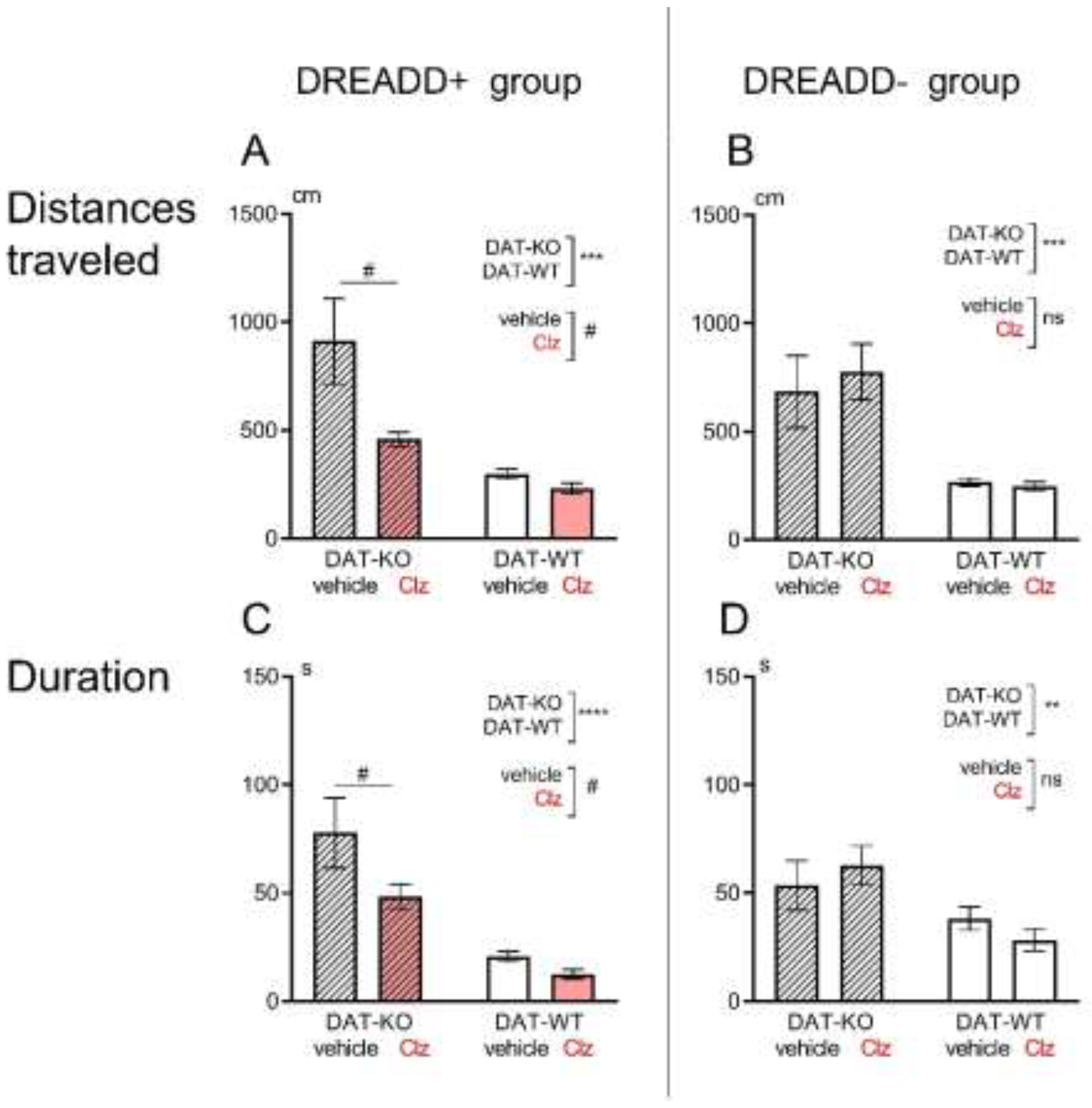

Figure 2A,B). The knockout rats also spent significantly more time performing the test (77,7±16,2 versus 20,8±2,4; p<0.001, Mann Whitney test,

Figure 2C,D). This fact indicates a pronounced hyperlocomotion in DAT-KO rats compared to WT animals.

For the DREADD+ group of DAT-KO rats, two-way ANOVA analysis of the "distance" parameter shows a significant difference (on the factor genotype, p<0.001, on the factor vehicle-Clz, p<0.05;

Figure 2A). Similarly, i.p. administration of Clz in DAT-KO rats resulted in a significant reduction in duration of test performance (two-way ANOVA analysis, the factor vehicle-Clz, p<0.05;

Figure 2C). Thus, activation of LC noradrenergic neurons in the DREADD+ group of rats by Clz resulted in a significant decrease in the distance travelled and the time spent in Hebb-Williams maze by DAT-KO rats. In WT rats, i.p. administration of Clz and activation of DREADD caused no change.

In the DREADD- groups of rats, i.p. Clz administration did not cause any significant changes in the distance traveled by the animals (

Figure 2B) and in the time needed to complete the test (

Figure 2D). We can conclude that i.p. administration of Clz alone at the chosen dose (1mg/kg) did not cause any significant changes in the parameters 'distance' and 'test performance time' in either knockout rats or WT animals (two-way ANOVA, the treatment factor, p>0.05).

Previous studies of the behavior of DAT-KO rats in spatial orientation tests have convincingly shown that they are less successful in achieving a goal compared to WT rats [

23,

24,

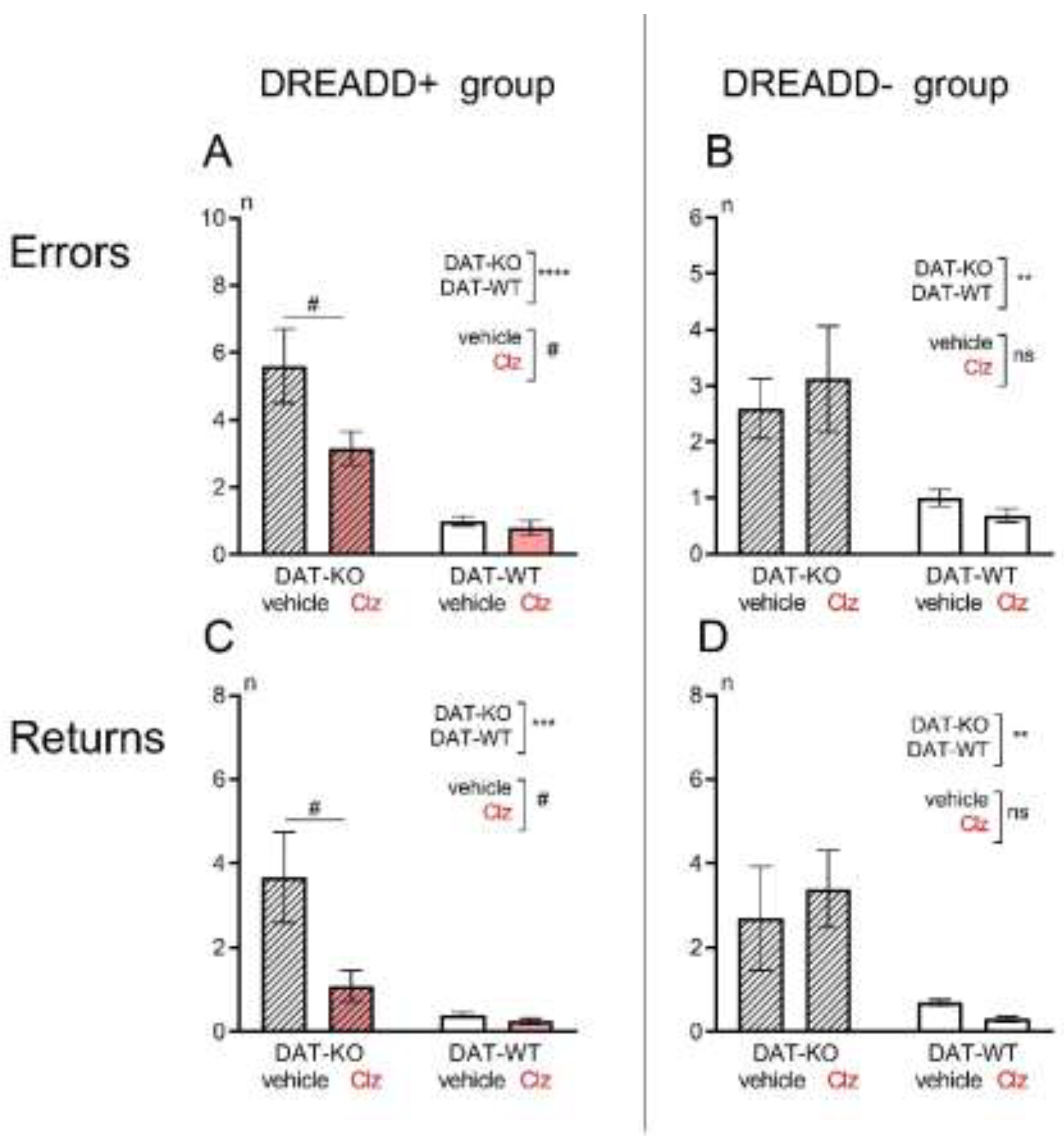

36]. The present study also confirmed these findings. The number of error zone visits was significantly higher in DAT-KO rats compared to WT animals (5,6±1,1 in DAT-KO versus 1,0±0.2; p<0.001, Mann Whitney test,

Figure 3A,B).

DAT-KO rats are also characterized by marked stereotypy and a tendency to perform inefficient repetitive motor acts [

25]. In the present experiment, we observed multiple returns to the start chamber of the maze in each experimental session without reaching the goal and without food reinforcement in DAT-KO rats. The level of such perseverative activity in DAT-KO rats was significantly higher than in WT rats (3,7±1,1 in DAT-KO versus 0,4±0.1; p<0.001, Mann Whitney test,

Figure 3C,D).

In the DREADD+ group of DAT-KO rats, the number of error zone visits and the number of the return runs significantly reduced after Clz injections (two-way ANOVA, the treatment factor, p<0.05;

Figure 3A,C). In WT rats, i.p. administration of Clz and activation of DREADD caused no change. In WT rats, i.p. administration of Clz and activation of DREADD did not alter the efficiency of test performance (number of error zone entries,

Figure 3A) or the number of returns to the start chamber (

Figure 3C).

In the DREADD- groups of rats, i.p. administration of Clz caused no changes in the number of rats’s visits the error zones or the number of return escapes (

Figure 3B,D). In both DAT-KO and WT rats, the i.p. administration of Clz did not alter the efficiency of the test performance (

Figure 3B) or the level of perseverative reactions (

Figure 3D).

3.2. Immunohistochemistry

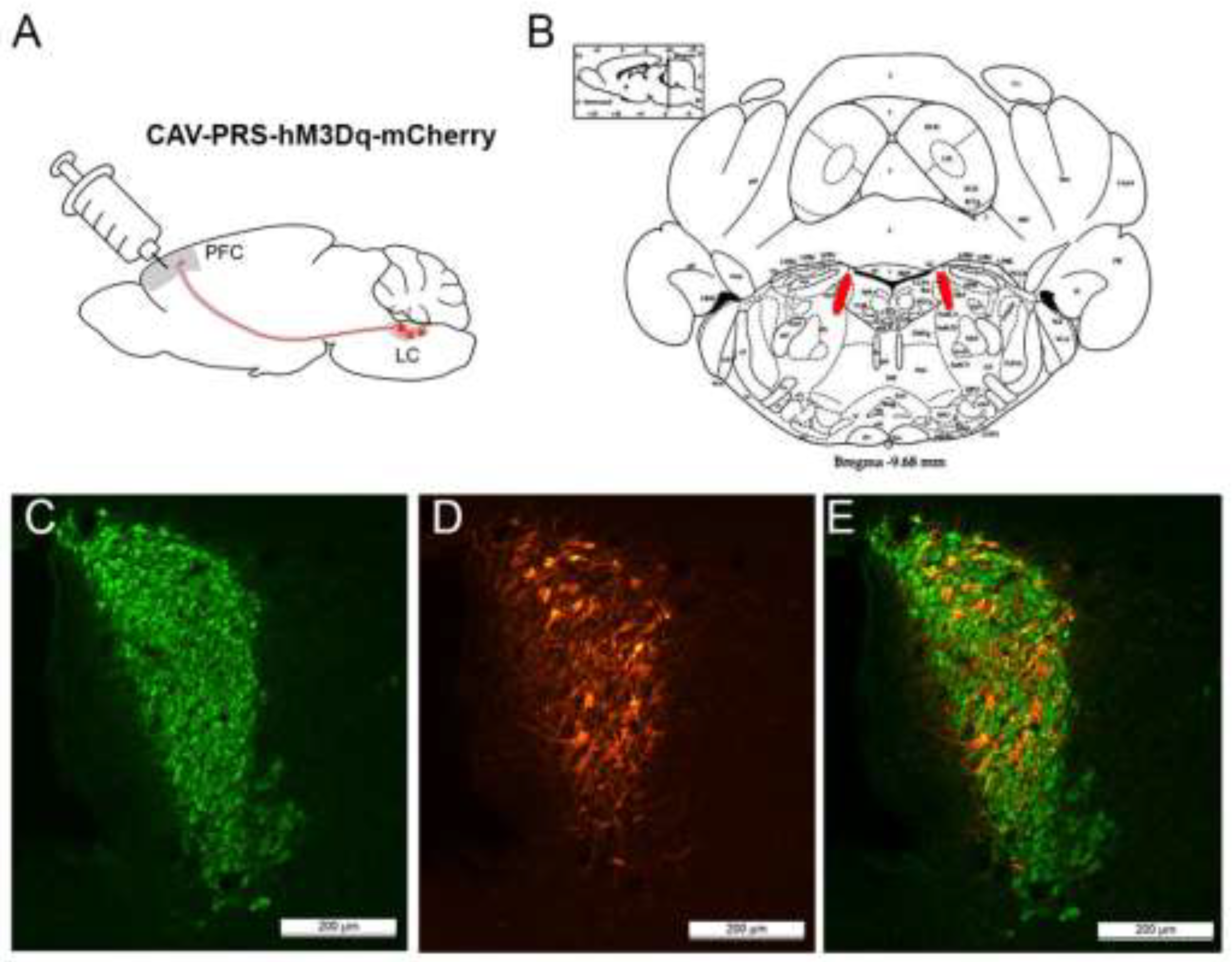

An immunohistochemical morphological control of the viral vector transduction was performed at the end of the experiment (

Figure 4). Together with the DREADD expression cassette, the fluorescent marker mCherry was delivered to the PFC of rats in the experimental DREADD+ group (

Figure 4A). This allowed to visualize the transducted neurons. The degree of transduction was assessed by double immunofluorescence staining using antibodies against dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DβH) (

Figure 4C) and mCherry (

Figure 4D).

It was found that in WT rats 24.5±1.7% of all DβH-positive neurons were transduced with the CAV2 PRS hM3D(Gq)-mCherry viral vector, whereas in DAT-KO rats the transduction rate was only 8.7±1.2%; significance of differences by Manni-Whitney test p<0.0001. Thus, we have shown that microinjection of CAV2 into the rat PFC results in efficient retrograde penetration of the viral vector into LC neurons and stable transduction of the NE neurons of this brain structure. In analyzing the data, it should be taken into account that in the LC of DAT-KO rats there are significantly fewer neurons carrying the artificial DREADD receptor, which may reduce the efficiency of chemogenetic activation of these neurons.

4. Discussion

The Locus Coeruleus is the main source of NE in the PFC [

38]. LC is described as very important for implementing many behavioral functions such as arousal, attention and spatial memory [

39]. Using chemogenetic and optogenetic methods, it has been shown that the LC is involved in the modulation of wakefulness [

40,

41], cognitive function [

42] and stress-related behavior [

43,

44].

The coexistence of DA and NE terminals in the PFC has been described previously [

45]. It is proposed that their interactions may play a key role in the realization of complex behavior, and a lack of balance between DA and NE may lead to the development of pathophysiological processes, including ADHD symptoms [

46,

47]. The overlapping functions of the neuromodulators can provide a new approach to the mechanisms of neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression [

48], schizophrenia [

46,

47], and ADHD [

49,

50].

The DAT-KO rats and mice are valuable animal models of ADHD [

22,

51]. Mutant rats lacking the dopamine transporter protein DAT, exhibit hyperdopaminergic and motor hyperactivity due to critically high levels of extracellular DA levels in the striatum [

20,

21,

22,

52]. DAT-KO rats and mice are characterized not only by pronounced hyperactivity, but also by a tendency to rigid and stereotyped reactions [

20,

22,

25,

53]. Nevertheless, they are able to perform orientation tasks in mazes [

23,

35], although they are required significantly more time to reach a similar level of learning as WT rats. DAT-KO rats are able to perform spatial and non-spatial behavioral tasks and create their own tactical approaches to obtain rewards [

23,

35,

36,

37]. They are most successful in an object recognition task: rats can learn to move an object and retrieve food from the rewarded familiar objects and not to move the non-rewarded novel objects [

35]. Interestingly, the knockout animals' tendency to react stereotypically made them perform this task with fewer errors compared to WT rats, and the learned skill could be retrieved from the memory over the long time, up to three months after training [

35]. Another characteristic feature of the behavior of DAT-KO rats is their almost complete inability to modify a learned skill due to rigidity and low flexibility in task performance [

25].

In the present work, we have demonstrated how chemogenetic activation of LC neurons can improve the behavioral performance of DAT-KO rats in the Hebb-Williams maze by reducing the number of errors and perseverative reactions. Similar results have previously been obtained in DAT-KO rats following administration of noradrenergic drugs [

24,

36].

Acute or repeated administration of the α2A-adrenoceptor agonist guanfacine significantly improved their perseverative activity pattern and reduced the time spent in the maze error zones [

36]. It is known that guanfacine, the agonist of α2A-adrenoceptor improves numerous PFC functions [

54]. The beneficial effects of guanfacine may arise via strengthening PFC network connectivity as a consequence of NE actions on postsynaptic α2A-adrenoceptors dendrite spines in PFC [

54,

55]. In contrast, the α2A-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine increased the number of perseverative responses [

24]. This observation is consistent with the results of chemogenetic suppression of NE transmission from LC neurons to the PFC, which led to the development of perseverative behavior in WT rats [

29].

In studies using chemogenetic DREADD-induced connectivity, activation of the LC-NE system was found to interrupt ongoing behavior and activate responses to silent stimuli [

56]. It has been shown that in working memory tasks, DA is mainly associated with reward expectancy, whereas NE provides memories about the goal and ways to achieve it [

57]. The data obtained in our study indicate that increase of NE release from LC to PFC reduced hyperactive behavioral patterns of DAT-KO rats with hyperdopaminergy. A decrease of perseverative activity and visits of erroneous zones were also found.

There are also some limitations to the application of chemogenetics to the study of behavioral patterns. Firstly, viral transduction of target neurons may not ensure that the genetic material reaches all cells of the structure under investigation. Therefore, the effects of chemogenetic stimulation, which do not affect all LC neurons, may not be expressed as strongly at the systemic level [

30]. Our work shows that the efficiency of transduction of noradrenergic LC neurons is significantly lower in DAT-KO than in WT rats. Nevertheless, we have shown that even under these conditions, chemogenetic activation of the LC-to-PFC connections reliably leads to marked changes in expressed behavioral parameters specifically in DAT knockout animals. DAT-KO rats show a decrease in perseverative activity and a reduction in the number of incorrect zones visited in the maze.

5. Conclusions

Thus, the results obtained in this study support an important modulatory role of NE system in hyperactivity and goal-directed spatial cognitive behavior in hyperdopaminergic DAT-KO rats. We may suggest that the interaction between DA and NE plays a leading role in this modulation, and chemogenetic activation of NE neurotransmission in hyperdopaminergic DAT-KO rats can significantly improve the performance of the spatial learning task.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.G., N.K., and A.V.; methodology, T.Sh. and N.K., E.P.; investigation, A.G., T.Sh., and M.Kh.; formal analysis, A.G. and T.Sh.., E.P.; resources, A.B. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K., A.G., and A.V.; writing—review and editing, N.K., M.Kh., R.R.G., and A.V.; funding acquisition, R.R.G. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number № 21-75-20069; the authors N.K. and R.R.G. acknowledge Saint Petersburg State University for a research project grant, 103825000, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics committee of St Petersburg University, Saint Petersburg, Russia, resolution No. 131-03-10 of 22 November 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented during this study are included in this published article. The raw data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The breeding of knockout animals were performed at the Research Resource Center “Vivarium” of the Research Park of the St Petersburg University; the genotyping of knockout animals and immunohistichemical analysis were performed at the “Centre for Molecular and Cell Technologies” of the Research Park of the St Petersburg University; the viral vector microinjection and control of transduction by immunohistochemistry were performed at the “Center for Cell Technologies” of the Institute of Cytology RAS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bari, B.A.; Chokshi, V.; Schmidt, K. Locus Coeruleus-Norepinephrine: Basic Functions and Insights into Parkinson’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poe, G.R.; Foote, S.; Eschenko, O.; Johansen, J.P.; Bouret, S.; Aston-Jones, G.; Harley, C.W.; Manahan-Vaughan, D.; Weinshenker, D.; Valentino, R.; et al. Locus Coeruleus: A New Look at the Blue Spot. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020 2111 2020, 21, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara, S.J. The Locus Coeruleus and Noradrenergic Modulation of Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009 103 2009, 10, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radley, J.J.; Williams, B.; Sawchenko, P.E. Noradrenergic Innervation of the Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex Modulates Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Responses to Acute Emotional Stress. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouret, S.; Sara, S.J. Network Reset: A Simplified Overarching Theory of Locus Coeruleus Noradrenaline Function. Trends Neurosci. 2005, 28, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, C.W.; Waterhouse, B.D. The Locus Coeruleus–Noradrenergic System: Modulation of Behavioral State and State-Dependent Cognitive Processes. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 42, 33–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, N.N.; Mack, N.R.; Gao, W.J. Prefrontal Modulation of Anxiety through a Lens of Noradrenergic Signaling. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1173326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agster, K.L.; Mejias-Aponte, C.A.; Clark, B.D.; Waterhouse, B.D. Evidence for a Regional Specificity in the Density and Distribution of Noradrenergic Varicosities in Rat Cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 521, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar-Slamloo, Y.; Fazlali, Z. Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Brain; Overlapping or Dissociate Functions? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 12, 504957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, V.A. Overview of Animal Models of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Tripp, G.; Wickens, J. Reinforcement, Dopamine and Rodent Models in Drug Development for ADHD. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, I.G.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, T.W.; Ji, E.S.; Shin, M.S.; Kim, C.J.; Hong, M.H.; Bahn, G.H. Swimming Exercise Alleviates the Symptoms of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 8, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsheh, J.Y.; Shiflett, M.W. Dopaminergic Modulation of Goal-Directed Behavior in a Rodent Model of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Zhen, J.; Meyer, E.; Erreger, K.; Li, Y.; Kakar, N.; Ahmad, J.; Thiele, H.; Kubisch, C.; Rider, N.L.; et al. Dopamine Transporter Deficiency Syndrome: Phenotypic Spectrum from Infancy to Adulthood. Brain 2014, 137, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiano, D.; Vallone, D.; Sadile, A. Dysfunctions in Dopamine Systems and ADHD: Evidence from Animals and Modeling. Neural Plast. 2004, 11, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, K.; Chen, A.L.C.; Braverman, E.R.; Comings, D.E.; Chen, T.J.H.; Arcuri, V.; Blum, S.H.; Downs, B.W.; Waite, R.L.; Notaro, A.; et al. Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder and Reward Deficiency Syndrome. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nikolaus, S.; Antke, C.; Beu, M.; Müller, H.W.; Nikolaus, S. Cortical GABA, Striatal Dopamine and Midbrain Serotonin as the Key Players in Compulsiveand Anxiety Disorders - Results from in Vivo Imaging Studies. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 21, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, N.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Sahakian, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. The Roles of Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Vengeliene, V.; Bespalov, A.; Robmanith, M.; Horschitz, S.; Berger, S.; Relo, A.L.; Noori, H.R.; Schneider, P.; Enkel, T.; Bartsch, D.; et al. Towards Trans-Diagnostic Mechanisms in Psychiatry: Neurobehavioral Profile of Rats with a Loss-of-Function Point Mutation in the Dopamine Transporter Gene. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhanov, I.; Leo, D.; Tur, M.A.; Belozertseva, I. V.; Savchenko, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R. Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats as the New Preclinical Model of Hyper- and Hypo-Dopaminergic Disorders. V.M. BEKHTEREV Rev. PSYCHIATRY Med. Psychol. 2019, 0, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.; Targa, G.; Fesenko, Z.; Leo, D.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Sukhanov, I. Dopamine Transporter Deficient Rodents: Perspectives and Limitations for Neuroscience. Biomol. 2023, Vol. 13, Page 806 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, D.; Sukhanov, I.; Zoratto, F.; Illiano, P.; Caffino, L.; Sanna, F.; Messa, G.; Emanuele, M.; Esposito, A.; Dorofeikova, M.; et al. Pronounced Hyperactivity, Cognitive Dysfunctions, and BDNF Dysregulation in Dopamine Transporter Knock-out Rats. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzina, N.; Aristova, I.; Volnova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R. Deficit in Working Memory and Abnormal Behavioral Tactics in Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats during Training in the 8-Arm Maze. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzina, N.; Belskaya, A.; Gromova, A.; Ignashchenkova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Volnova, A. Modulation of Spatial Memory Deficit and Hyperactivity in Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats via A2A-Adrenoceptors. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belskaya, A.; Kurzina, N.; Savchenko, A.; Sukhanov, I.; Gromova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Volnova, A. Rats Lacking the Dopamine Transporter Display Inflexibility in Innate and Learned Behavior. Biomed. 2024, Vol. 12, Page 1270 2024, 12, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.S.; Bucci, D.J.; Luikart, B.W.; Mahler, S. V. Dreadds: Use and Application in Behavioral Neuroscience. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 135, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, B.L. DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron 2016, 89, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.J.; Marchant, N.J. The Use of Chemogenetics in Behavioural Neuroscience: Receptor Variants, Targeting Approaches and Caveats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanova, A.; Fedorov, L.; Eschenko, O. The Projection-Specific Noradrenergic Modulation of Perseverative Spatial Behavior in Adult Male Rats. eNeuro 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanova, A.; Yang, M.; Logothetis, N.K.; Eschenko, O. Partial Chemogenetic Inhibition of the Locus Coeruleus Due to Heterogeneous Transduction of Noradrenergic Neurons Preserved Auditory Salience Processing in Wild-Type Rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, K.; Mulder, G.B. Operant Conditioning. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2004, 43, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Falcy, B.A.; Mohr, M.A.; Micevych, P.E. Immunohistochemical Amplification of MCherry Fusion Protein Is Necessary for Proper Visualization. MethodsX 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012 97 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi, A.; Zelli, S.; Leo, D.; Carbone, C.; Mus, L.; Illiano, P.; Alleva, E.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Adriani, W. Behavioral Characterization of DAT-KO Rats and Evidence of Asocial-like Phenotypes in DAT-HET Rats: The Potential Involvement of Norepinephrine System. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 359, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzina, N.; Volnova, A.; Aristova, I.; Gainetdinov, R.R. A New Paradigm for Training Hyperactive Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats: Influence of Novel Stimuli on Object Recognition. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 654469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volnova, A.; Kurzina, N.; Belskaya, A.; Gromova, A.; Pelevin, A.; Ptukha, M.; Fesenko, Z.; Ignashchenkova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R. Noradrenergic Modulation of Learned and Innate Behaviors in Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats by Guanfacine. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.; Müller, C.; Lubec, J.; Leo, D.; Korz, V.; Afjehi-Sadat, L.; Malikovic, J.; Sialana, F.J.; Lubec, G.; Sukhanov, I. The Lack of Dopamine Transporter Is Associated With Conditional Associative Learning Impairments and Striatal Proteomic Changes. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E.E. Locus Coeruleus. Cell Tissue Res. 2017 3731 2017, 373, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton-Provencher, V.; Drummond, G.T.; Sur, M. Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine in Learned Behavior: Anatomical Modularity and Spatiotemporal Integration in Targets. Front. Neural Circuits 2021, 15, 638007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.E.; Yizhar, O.; Chikahisa, S.; Nguyen, H.; Adamantidis, A.; Nishino, S.; Deisseroth, K.; De Lecea, L. Tuning Arousal with Optogenetic Modulation of Locus Coeruleus Neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2010 1312 2010, 13, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, F.; Nakamura, T.; Kuroyanagi, H.; Tanaka, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yanai, K.; Okamura, N. Chemogenetic Modulation of Histaminergic Neurons in the Tuberomamillary Nucleus Alters Territorial Aggression and Wakefulness. Sci. Reports 2021 111 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, A.; Tan, B.Z.; Ycu, E.A.; Cuevas, J.S.; Koivumaa, J.; Junyent, F.; Kremer, E.J.; Witten, I.B.; Deisseroth, K.; Johansen, J.P. Modular Organization of the Brainstem Noradrenaline System Coordinates Opposing Learning States. Nat. Neurosci. 2017 2011 2017, 20, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberg, S.; Li, Y.; Randall, A.; Kremer, E.J.; Pickering, A.E. Functional Dichotomy in Spinal-vs Prefrontal-Projecting Locus Coeruleus Modules Splits Descending Noradrenergic Analgesia from Ascending Aversion and Anxiety in Rats. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, J.G.; Siuda, E.R.; Bhatti, D.L.; Lawson, L.A.; McElligott, Z.A.; Stuber, G.D.; Bruchas, M.R. Locus Coeruleus to Basolateral Amygdala Noradrenergic Projections Promote Anxiety-like Behavior. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, T.W.; Arnsten, A.F.T. The Neuropsychopharmacology of Fronto-Executive Function: Monoaminergic Modulation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, O.D.; McCutcheon, R.; Owen, M.J.; Murray, R.M. The Role of Genes, Stress, and Dopamine in the Development of Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd-Gurvich, C.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N.; Bradshaw, J.L.; White, O.B. Negative Symptoms: A Review of Schizophrenia, Melancholic Depression and Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2006, 70, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.J. Relationship of Neurotransmitters to the Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 17337. [Google Scholar]

- Kessi, M.; Duan, H.; Xiong, J.; Chen, B.; He, F.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y.; Bamgbade, O.A.; Peng, J.; Yin, F. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder Updates. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 925049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, S.; Grimsrud, G.; Mooney, M.A.; Larsen, B.; Feczko, E.; Elison, J.T.; Nelson, S.M.; Nigg, J.T.; Tervo-Clemmens, B.; Fair, D.A. Neurobiology of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Historical Challenges and Emerging Frontiers. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024 2512 2024, 25, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainetdinov, R.R.; Wetsel, W.C.; Jones, S.R.; Levin, E.D.; Jaber, M.; Caron, M.G. Role of Serotonin in the Paradoxical Calming Effect of Psychostimulants on Hyperactivity. Science (80-. ). 1999, 283, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, S.; Zoratto, F.; Poleggi, A.; Leo, D.; Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Tambelli, R.; Alleva, E.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Laviola, G.; et al. Behavioral Phenotyping of Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats: Compulsive Traits, Motor Stereotypies, and Anhedonia. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorelov, V.M.; Rodriguiz, R.M.; Insco, M.L.; Caron, M.G.; Wetsel, W.C. Novelty Seeking and Stereotypic Activation of Behavior in Mice with Disruption of the Dat1 Gene. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 1818–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnsten, A.F.T. Guanfacine’s Mechanism of Action in Treating Prefrontal Cortical Disorders: Successful Translation across Species. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2020, 176, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, T.; Yamamuro, K.; Okazaki, K.; Kishimoto, T. Evaluating Guanfacine Hydrochloride in the Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd) in Adult Patients: Design, Development and Place in Therapy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbi, V.; Floriou-Servou, A.; Markicevic, M.; Vermeiren, Y.; Sturman, O.; Privitera, M.; von Ziegler, L.; Ferrari, K.D.; Weber, B.; De Deyn, P.P.; et al. Rapid Reconfiguration of the Functional Connectome after Chemogenetic Locus Coeruleus Activation. Neuron 2019, 103, 702–718.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, Z.L.; Carboni, S. Noradrenaline and Dopamine Elevations in the Rat Prefrontal Cortex in Spatial Working Memory. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 2322–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).