1. Introduction

For patients with terminal liver disease, liver transplantation (LT) significantly improves survival and quality of life [

1]. Post-transplant health, both physical and mental, is influenced by various factors. Nurses play a vital role in coordinating care and providing education [

2]. Nursing interventions should focus on enhancing outcomes by identifying sources of motivation and coping, like support groups and spirituality [

3]. Both chronic liver disease and the LT procedure can be traumatic. Studies report patients find diagnosis and intensive care traumatic [

4]. Resilience, the ability to stay focused despite adversity, is linked to social support, depression, quality of life, anxiety, cognitive ability, and age [

5,

6].

Post-traumatic Growth (PTG) suggests that stressful events can activate personal resources, enhancing functionality and serving as a protective factor to turn threats into challenges [

7]. Pérez-San-Gregorio et al., (2017) found that PTG after LT is linked to quality of life, indicating its importance in ensuring long-term well-being [

8]. Funuyet-Salas et al., (2019) observed differences in PTG among LT patients based on perceived health and vitality [

9]. PTG benefits recipients as they recover, with support being crucial for eligibility and outcomes [

10]. Higher PTG levels in LT recipients are linked to more adaptive coping strategies [

11]. Pérez-San-Gregorio et al., (2018) found that adherence to treatment was positively associated with social disclosure and negatively with guilt [

12].

Incorporating a gender perspective in research is good practice [

13]. Race and gender impact the chances of receiving a LT [

14]. Women’s health outcomes are particularly affected by gender bias in healthcare, suggesting disparities in the transplant system [

15]. Melk et al., (2019) highlight gender differences in access and outcomes of transplants, with 35% women and 65% men. Social determinants of health are key to health inequities, and gender is often overlooked in studies [

16]. Listabarth et al., (2022) identified inequalities in access and management of liver transplants in patients with alcohol-related liver disease, concluding that more research with a gender perspective is needed [

17]. There are previous studies that have considered gender as significant in behaviors as important as adherence to immunosuppressive treatment [

18,

19,

20]. The recent study by Chen et al., (2021) studied the differences in gender and roles in the experience after LT, revealing differences based on their gender and roles between the main beneficiaries and caregivers, whose claims were based on the potential influences of tradition, culture and modern medicine [

21]. The contributions of the gender perspective promote equity, improve health, can strengthen policies, create opportunities for innovation and improve solutions aimed at meeting the needs of society [

22]. PTG is one of the important factors affecting the psychological status, negative growth may lead to the physical and mental health of the patient and then affect the adherence. However, there have been no studies found linking general mental health, posttraumatic growth, and gender disparities in resilience after LT.

This study’s main aim was to analyze differences between gender in psychological resilience, psychological post-traumatic growth, and transplant effects after liver transplantation. The secondary aims were: 1) to examine the relationship between resilience levels and health outcomes following liver transplantation; and 2) to explore how resilience mediates and moderates the relationship between post-traumatic growth and the effects of organ transplantation in liver transplant patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A descriptive cross-sectional single-center study was carried out at the Liver Transplant Unit at Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital. Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital is a low-medium volume transplant center with a mean of 46.5 LT per year [

23]. Nursing has a specific process within the process map of the liver transplant unit. Nursing coordinates the post-transplant consultation, taking care of prevention and health promotion during the first year. During the first six months, the nurse performs weekly or biweekly checkups, reaching monthly visits until the first year.

2.2. Study Participants and Setting

The inclusion criteria were adult liver transplant patients under follow-up at the Liver Transplant Unit at Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital, with no age limit and with the ability to understand and complete the questionnaires provided for the study. The exclusion criteria were patients who have received an organ transplant other than the liver, those patients with known acute psychiatric pathology were excluded; the clinical history had previously been reviewed, and patients who, due to some health condition, could not complete the questionnaires. Overall, no patients were excluded due to acute psychiatric disorders, including diagnoses of schizophrenia, unstable bipolar disorder, and other active psychotic conditions. It is important to note that no patients with stable alcohol dependence were excluded, or that there were no patients with these characteristics, since, as you rightly mention, this does not constitute a formal limitation for liver transplantation in Spain.

2.3. Data Quality Assurance

Pretest of the data collection instrument was conducted on 5% of patients at the same hospital before the actual data collection to check the applicability of the instrument and make necessary adjustments. These samples were not included in the final analysis. The collected data were checked for completeness, accuracy, and clarity. Incomplete data was discarded and counted as non-responses.

2.4. Data Collection

Data was collected during May-July 2021. All liver transplant patients under follow-up in the liver transplant service of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital, a total of n=297 patients, were invited to participate. The patients were contacted by telephone and the purpose of the study was explained to them. Those patients who decided to participate voluntarily went to the nurse's office at the Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital, having previously agreed on a time for the meeting. The nurse provided the information and informed consent sheet for the participants and later hand-delivered the paper questionnaires for the participants to fill out. The participants returned the completed questionnaires to the liver transplant nurse practitioner. Sociodemographic variables were collected including age, gender, and date of LT. Multiple data collection instruments were used. Instruments were freely available. The questionnaires were provided on paper and handed personally by the research nurse to the participants. The questionnaires were self-completed by the patients, who returned them by hand to the research nurse.

2.5. Study Instruments

To establish the degree of resilience, the instrument used was the Connor-Davidson 10 Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [

24], and it was validated previously in Spanish population [

25], and also it has previously been used in LT patients [

6]. We have considered the resilience score as a health conditioner that can impact the effects of transplantation. CD-RISC-10 is a 10-item unifactorial scale. The participant responds to each of the items (“Not at all”, “Rarely”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, “Almost always”) assigning a value between 0-4 to each response respectively, being the final value the sum of the scores of the 10 items. The cut-off value for a normal resilience is between 28-35 points. The CD-RISC-10 reliability, Cronbach's alpha, was 0.81 in its validation study in the Spanish population [

26].

The evaluation of Post Traumatic Growth was carried out with the 21-item Post Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) scale [

7]. The PTGI is a 21-item self-report measure designed for assessing positive outcomes reported by people who have experienced adverse life events including bereavement. The full-scale Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. The factors which emerged also showed substantial internal consistency ranged from 0.67 to 0.85: New Possibilities; Relating to Others; Personal Strength; Spiritual Change; Appreciation of Life. The PTGI scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“I did not experience this change because of my loss”) to 5 (“I experienced this change to a very great degree because of my loss”). Greater positive changes after the loss are suggested with higher sum score of all items [

7]. The Spanish version has demonstrated good psychometric properties [

27].

Finally, Transplant Effects Questionnaire (TxEQ-Spanish) is important to be able to assess and compare these effects and can help to optimize treatment. It consists of 22 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, was used. It contains five subscales that assess worry about the transplant, guilt regarding the donor, disclosure, adherence, and responsibility (items, e.g., “I am worried about damaging my transplant”). The score for each subscale is calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items. Higher scores show a higher degree of the dimension in question. All five subscales' Cronbach's alpha values—worry 0.82, guilt 0.77, disclosure 0.91, adherence 0.82, and responsibility 0.83—were satisfactory as a measure of reliability [

12].

The explanation of how the scoring of the studied scales was carried out is described in the supplementary file 1.

2.6. Data Analysis

An exploratory analysis was carried out. Data analysis using descriptive statistics, means, standard deviation (SD), minima and maxima, and frequencies (as appropriate) were given of all variables. An exploratory analysis of the data was performed to identify outliers or extreme values and characterize differences between groups of cases. The most appropriate statistical techniques were identified, and it was checked whether the data followed a Gaussian distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. The student's t-test and the chi-square test were used to compare the different variables. For those non-parametric samples, the Wilcoxon sign, Mann-Whitney U, and Kruskal-Wallis’s test with time grouped into four categories were used. We performed homogeneity tests on age, time of LT, and resilience scale score that allowed us to confirm that variability between gender subpopulations did not significantly affect the interpretation of the data. The independent variables were those that showed statistical significance in the bivariate analysis or were considered relevant in the conceptual framework of the study. To assess the mediating effect of resilience between PTG and TxEQ-Spanish, we conducted the Sobel-Goodman mediation test, adjusting for the control variables: age, years since LT, and gender. To determine the correlation between the different instruments used, Spearman's rho coefficient was calculated. An explanatory linear regression model was developed separately for men and women to examine the factors associated with resilience. The dependent variable was resilience, measured by the total score on the CD-RISC-10 questionnaire. The analyses were performed with STATA v.16.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This study, and its written consent form, was approved by Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital Ethical Committee (code IMPACT_TH of the 02/2021 minutes) and was conducted in accordance with the principles articulated in the Declaration of Helsinki [

28]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study followed the STROBE criteria for quantitative studies [

29]. An information page and informed consent was handed to each participant.

3. Results

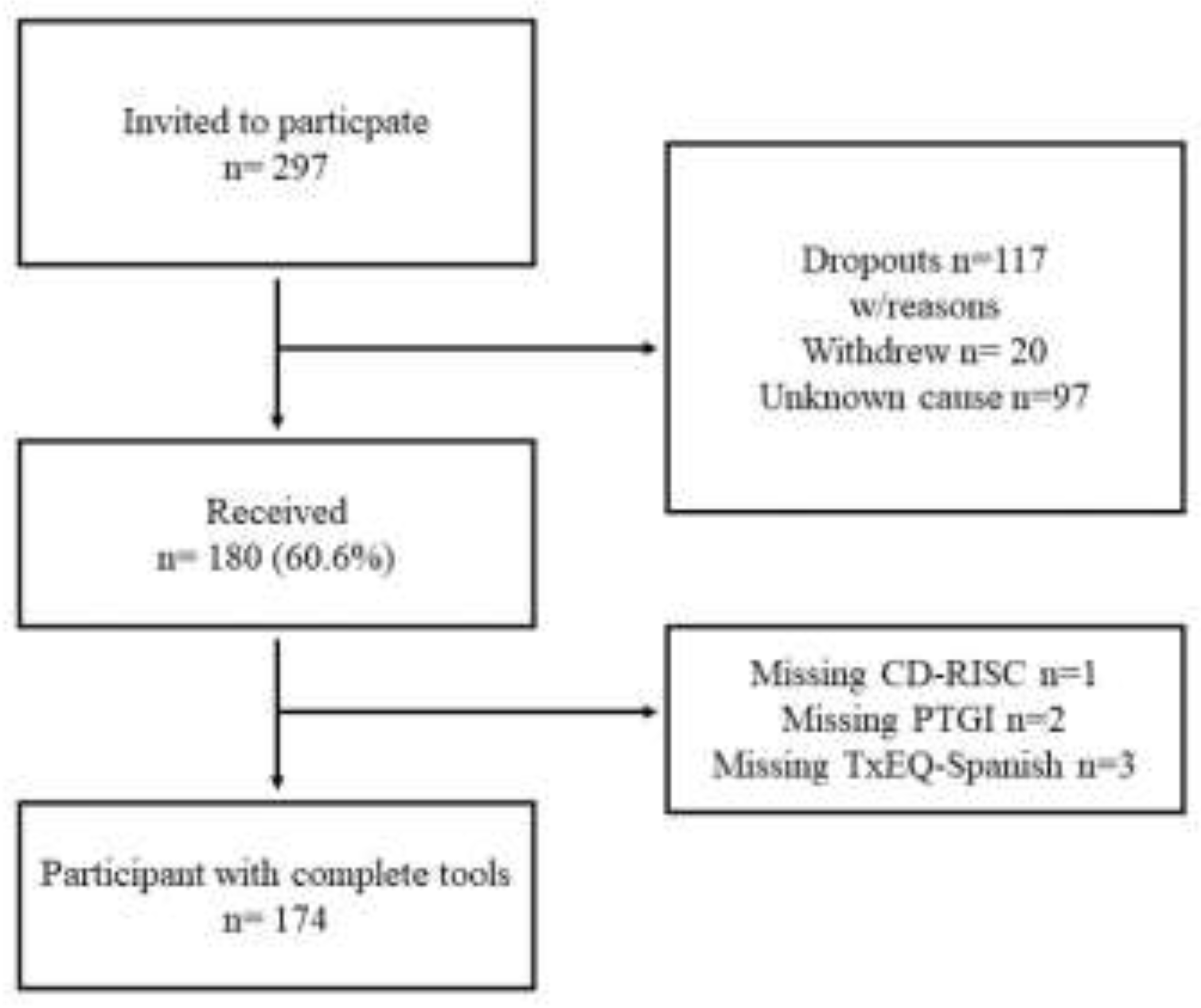

From a total cohort of 297 LT patients invited to participate int the study, 180 (60.6%) handed in the questionnaires. Of these, 174 (58.6%) fully responded to all items of all questionnaires (

Figure 1).

Of the n= 174 LT patients who answered, the average study age was 61.06 (SD 11.33) years, with a minimum value of 24 and a maximum of 86 years old. The average LT age was 51.05 (SD 11.54). A total of 24.1% (N=42) were women. The stratification of the female sample by age was 35 years old or younger N=2 (4.8%), 36 to 49 years old N=5 (11.9%), 50 to 64 N=13 (31%), and 65 years old or older N=22 (52.4%). Following the same stratification, the male sample by age was N=5 (3.8%), N=10 (7.6%), N=68 (51.5%), and N=49 (37.1%). The average numbers of years from LT were 10.01 years (SD 7.73) (

Table 1).

Participants surveyed level of resilience (N=174) had an average value of 30.83 (SD 6.53) been 44.3% (N=77) normal resilience level, 27% (N=47) high resilience level, and 28.7% (N=50) low resilience level. Male participants had a median value of 32 [IQR 27-36], while female participants had 32 [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], no statistically significant relationships have been found between genders (p=0.525).

On the other hand, the PTG after LT, the results of the bivariate analysis have shown that women experience higher growth than men in all the inventory dimensions. It’s been statistically significant within the new possibilities, the spiritual change, and the personal strength dimensions. Regarding our results of the effects of transplantation with the Tx-EQ Spanish, we performed an analysis of two independent samples by gender where our results do not show significant differences in this regard (

Table 2).

Further analysis was taken according to our secondary study aim. Our results described a significant relationship between resilience in all the dimensions post traumatic growth inventory, and with the score of adherences to immunosuppressive treatment after liver transplantation (

Table 3).

3.1. Multivariable Analysis

A multiple linear regression analysis of resilience adjusted by gender was carried out (

Table 4). In the regression model by male gender, the variable that had a specific weight in affecting resilience after liver transplantation was personal strength (R-squared = 0.189). In contrast, in the regression model by female gender, the variable with the highest specific weight in affecting resilience after liver transplantation was relationship with others, followed by adherence to immunosuppressive treatment (R-squared = 0.484).

3.2. Mediation and Moderation Analysis of Resilience

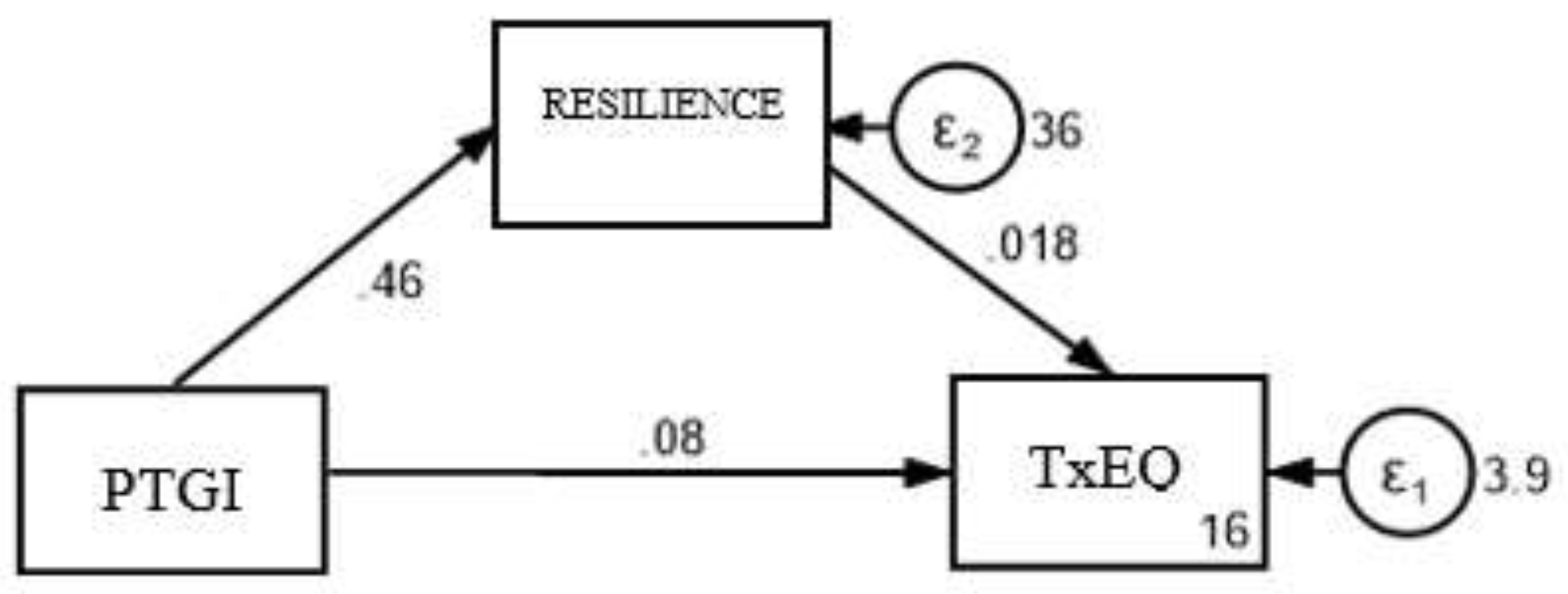

Mediation analysis was performed to determine whether the effect of the independent variable (PTG) on the dependent variable (TxEQ-Spanish) could be mediated by a change in the mediating variable (resilience, CD-RISC).

As shown in

Figure 2, the direct effect (c’) refers to the path from PTG to TxEQ-Spanish while controlling for the mediating variable; the indirect effect (ab) refers to the effect of PTG on TxEQ-Spanish through the mediating variable, and the total effect (c) refers to the sum of the direct and indirect effects of PTG on TxEQ-Spanish. This total effect occurs when the mediating variable is excluded. The results show significant results in the direct (c’ = 0.086, p = 0.005) and total (c = 0.095, p = 0.001) effect of the PTG on the TxEQ-Spanish, as shown in

Table 5. The indirect effect of the model is not significant (ab = 0.009, p = 0.478), since the zero value is included in the 95% confidence interval (LI = -0,015, LS = 0,033) and since the Sobel test described not statistically significant values for partial mediation (z = 0.789, p = 0.478). Proportion of total effect that is mediated: 0.092: This indicates the proportion of the total effect that is explained through the mediating variable resilience.

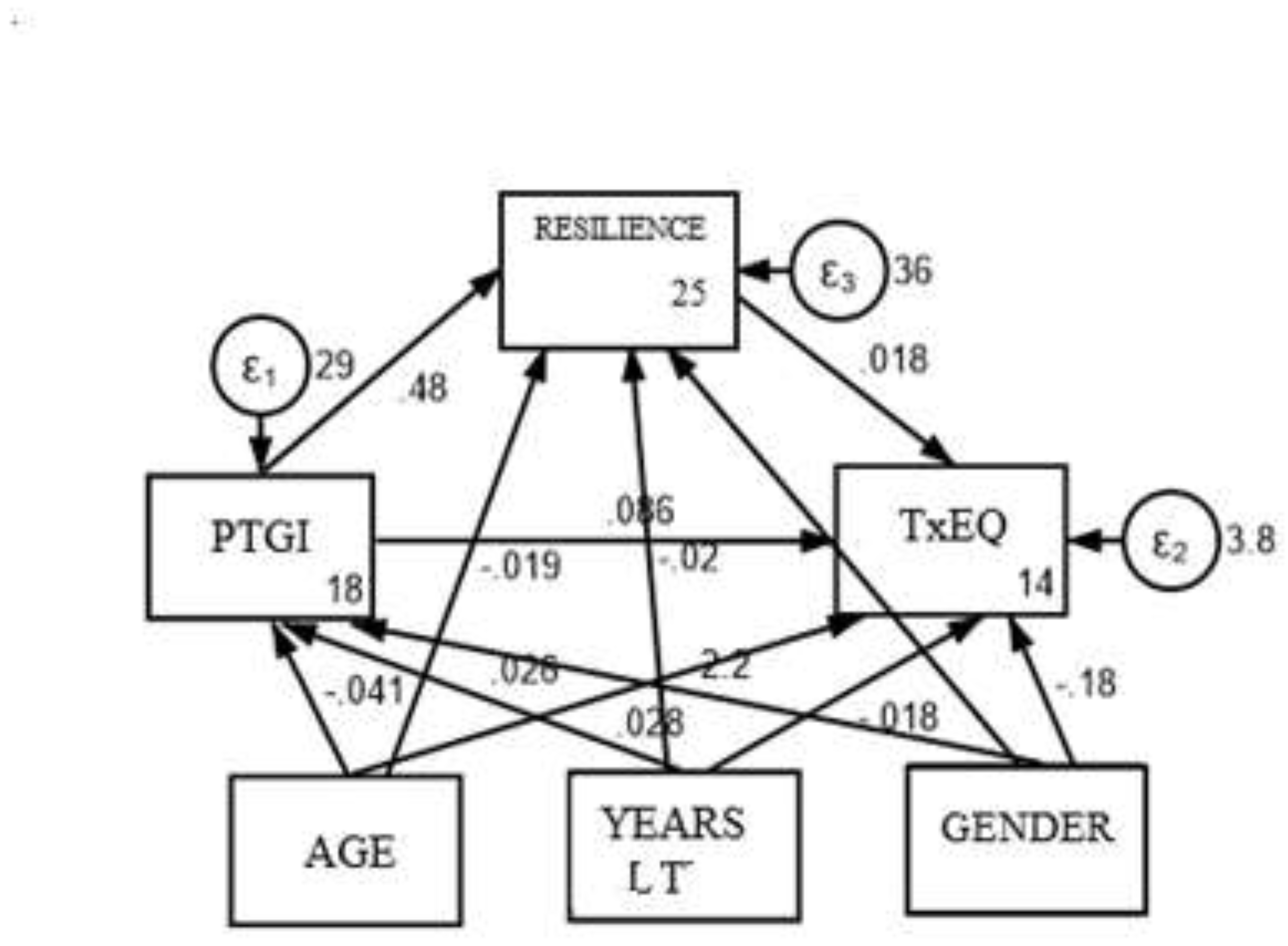

Additionally, a moderated mediation analysis was conducted to determine whether the mediation results from the previous analysis were independent of certain contextual variables. The contextual variables examined included gender, age, and years since liver transplantation (LT). The conceptual and statistical framework for this analysis is illustrated in

Figure 3. The results of the moderated mediation analysis indicated that gender (95% CI: LI = −0.882, LS = 0.534), age (95% CI: LI = −0.074, LS = 0.045; LI = −0.001, LS = 0.058), and years since LT (95% CI: LI = −0.057, LS = 0.021) were not significant moderators of the relationship between the two variables.

The results suggest that there is no significant mediated effect through the variable resilience. The proportion of total mediated effect is 9.2%%, indicating that about 9.2% of the total effect of PTG on TxEQ-Spanish is explained through resilience. The ratio of indirect to direct effect and the ratio of total to direct effect provide additional information on the relative magnitude of these effects.

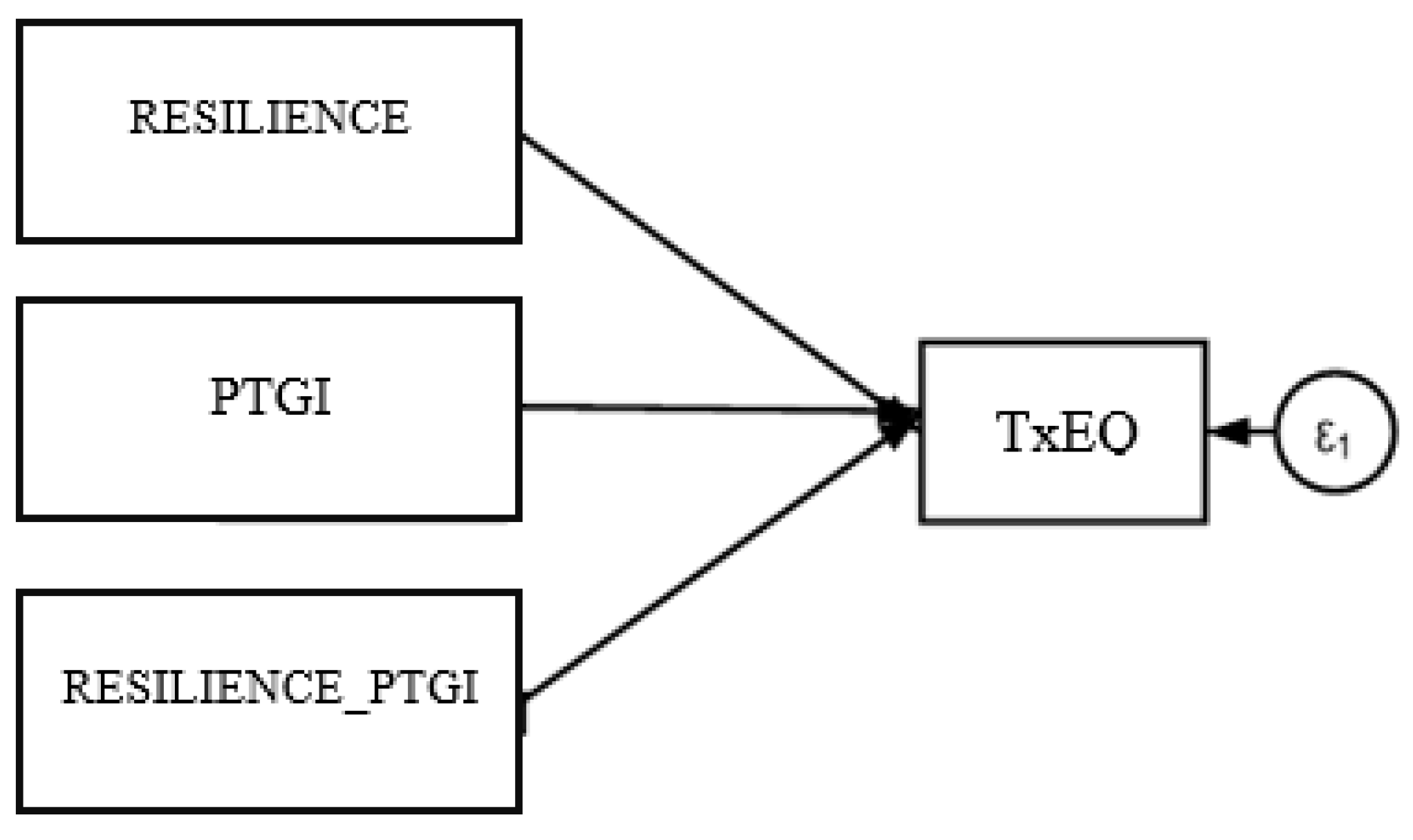

The moderation analysis was conducted to assess whether the strength of the relationship between PTG and TxEQ-Spanish is influenced by resilience levels in liver transplant patients. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the analysis considered PTG as the predictor variable, TxEQ-Spanish as the dependent variable, and resilience as the moderating variable. The results indicated that resilience does not have a moderating or modifying effect on TxEQ-Spanish (−0.001, p=0.799). This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

There are gender differences that deserve careful consideration in treatment adherence in LT patients to improve drug safety and optimize transplanted organ survival. Our results do not describe a mediating and moderating effect of resilience on PTG, not on the psycho-emotional effects of transplantation. A better understanding of sex- and gender-related differences in this field provides the opportunity for a personalized therapeutic approach and follow-up for the management of these patients.

Our results show that LT women patients score higher in all dimensions of post-traumatic growth (PTG), especially in "relationship with others" and "spiritual changes." PTG significantly contributes to resilience, differing by gender: men in “personal strength” and women in “relationship with others.” Pérez-San Gregorio et al., (2017) found no gender differences, differing from our findings. Both studies found no significant difference between time since transplantation and PTG [

8]. Martín-Rodríguez et al., (2018) found that those who frequently thought about their donor experienced greater PTG, especially in spiritual growth, new life appreciation, and new possibilities post-transplant [

30]. Although we did not analyze the impact of thinking about the donor, considering our gender-based findings, it may be beneficial to explore both factors in future studies. Our results suggest men, who exhibited less PTG, might benefit from the psychological integration of donor thoughts to enhance PTG through increased gratitude [

7].

Our study aligns with Burra et al., (2013) that understanding gender in liver transplants requires moving beyond a binary view, recognizing more complex processes influenced by hormones, social, and age factors [

31]. In heart transplants, men and women exhibit different coping styles and stress responses [

32]. Pérez-San-Gregorio et al., (2017) found liver transplant patients use more adaptive coping strategies, linked to greater post-traumatic growth [

11]. Our findings indicate women score higher in all PTG dimensions, suggesting they have more effective coping strategies, a hypothesis for future studies. Another study found men needed to enhance dignity and family roles, while women sought positive experiences and psychological support [

21]. Our results highlight gender differences, necessitating gender-specific strategies and interventions.

Tomaszek et al., (2021) found resilience predicts PTG in kidney transplant recipients [

33]. Despite gender differences in PTG in our study, we found no gender differences in resilience post-liver transplantation or in relation to time since transplantation. Fallon et al., (2020) noted that resilience pathways differ between sexes, with women experiencing more stress-related disorders [

34]. Our study found resilience correlates with all dimensions of PTG and better adherence to treatment. Hence, nursing should focus on enhancing resilience in transplant patients. For men, this involves boosting personal strength and motivation. For women, it involves strengthening family trust and support groups. A study has analyzed liver transplant patients using the TxEQ-Spanish questionnaire. Tarabeih et al., (2020) studied Israeli liver transplant recipients with a mean of 7 years post-LT and a maximum age of 55 years, finding scores for worry (5), guilt (2.45), disclosure (4.65), adherence (1.25), and responsibility (3.2) [

35]. Our results, with a mean patient age of 61 years and an average of 10 years since LT, differ significantly. A recent study on young adult transplant recipients noted gender differences in therapeutic adherence [

36]. While our results do not show gender differences, they do reveal a negative correlation between resilience, and both worry and guilt. Treatment adherence significantly correlates with resilience, particularly in women, likely influenced by the close follow-up from a liver transplant nurse practitioner at our hospital.

Finally, the study about quality of life after liver transplantation by Onghena et al., (2016) concluded that multidisciplinary interventions of psychological and biosocial treatment are needed to improve quality of life [

37]. Guilt, responsibility, and worries are linked to limited mental health, while higher mental health is associated with disclosure about transplantation [

38]. Our results showed a strong correlation between different scales and questionnaires. Resilience is crucial for patients undergoing liver transplantation to face possible adversities. Reducing guilt and worry and improving adherence to immunosuppressive treatment will enhance resilience. Nursing should promote disclosure and adherence to immunosuppressive treatment, guiding and empowering patients to cope with transplantation challenges. This involves focusing on personal strength for men and relationships with others for women. Despite limitations, our results highlight the need for gender-specific interventions to improve patients' quality of life after liver transplantation. Future studies should consider age and time since transplantation in mental health analyses. The lack of a mediating or moderating effect on resilience between PTG and the TxEQ-Spanish opens new avenues for psychological research. Future studies should explore additional contributing variables (Supplementary file 2).

We have found several limitations in our study. We did not consider analyzing further clinical variables as the liver disease etiology nor personality variables, nor other socioeconomic data (socioeconomic status, ethnicity/immigration background, etc.) which may contribute to diminished quality of life, self-management abilities, etc. We share the hypothesis that patients may have different psychological states depending on the etiology of the disease, such as patients with liver disease due to alcohol consumption. For this reason, we encourage future studies to consider etiology as an important variable to consider. Long-term post-transplant health parameters as rehospitalization, infections, or other complications were assessed. The validity of findings may be limited as we only recruited patients from a single site. The women/men ratio in the sample was just 1:4, due to be a low-medium liver transplant center. Future study should be performed multicentrally aiming to recruit bigger and more balanced samples by gender. The study has had a high dropout rate among those invited to participate. The data was collected during the year 2021 when the COVID-19 pandemic continued to affect the Spanish population and there were social restrictions. We want to include this situation as a possible determining factor of the results obtained. Future studies should provide data based on a longitudinal design that allows a better understanding of resilience and PTG. We understand and share that a longitudinal design would be more appropriate to understand resilience and PTG.

On the contrary, a major strength of this study is the large sample size and the analysis of recipients.

5. Conclusions

There are significant differences between men and women in terms of post-traumatic growth since liver transplantation. Furthermore, the level of resilience is correlated differently between men and women. In one hand, resilience in men is correlated with personal strength, in the other hand, resilience in women is correlated with relationships with others. Resilience does not have a mediator or modulate effect in PTG and the TxEQ-Spanish. These differences will help us to better understand the psychological events suffered by patients during their follow-up.

The results provide us with the necessary knowledge to validate and improve our intervention with the patient's gender perspective within this process. Nursing should focus its interventions differently on men and women. To improve resilience in men, you must focus on aspects of personality, motivation, abilities, and self-esteem. On the other hand, in women it should focus on their family and social relationships. We must incorporate a gender perspective in our nursing interventions to deepen our knowledge of the determinants of emotional changes and the ability to deal with them. Future studies should use a mixed methodology (quantitative-qualitative) that expands the information on gender differences and roles in society.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.F.A., A.M.H.M. and M.N.M.T.; methodology, V.F.A. and M.P.G.; software, M.N.M.T, M.L.C. and V.F.A.; validation, M.P.G. and M.N.M.T.; formal analysis, M.N.M.T. and V.F.A; investigation, V.F.A. and A.M.H.M.; resources, V.F.A. and A.M.H.M.; data curation, M.L.C and M.N.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.F.A., M.P.G. and A.M.H.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.C. and M.N.M.T.; visualization, V.F.A. and M.N.M.T.; supervision, M.P.G. and A.M.H.M.; project administration, V.F.A.; funding acquisition, M.N.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the General University Gregorio Marañón Hospital Ethical Committee (code IMPACT_TH on the 02/2021 act).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon contact and authorization from the authors of the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nursing Research Support Unit from the Gregorio Maranon Sanitary Research Institute for supporting this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Júnior, R.F.M.; Salvalaggio, P.; de Rezende, M.B.; Evangelista, A.S.; Della Guardia, B.; Matielo, C.E.L.; Neves, D.B.; Pandullo, F.L.; Felga, G.E.G.; Alves, J.A.d.S.; et al. Liver transplantation: history, outcomes and perspectives. Einstein-Sao Paulo 2015, 13, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrellas, N.; Carol, M.; Palacio, E.; Aban, M.; Lanzillotti, T.; Nicolao, G.; Chiappa, M.T.; Esnault, V.; Graf-Dirmeier, S.; Helder, J.; et al. Nursing Care of Patients With Cirrhosis: The LiverHope Nursing Project. Hepatology 2020, 71, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, S.R.; Kim, H.P.; Baldelli, L.; Nash, R.; Teal, R.; Magee, G.; Loiselle, M.M.; Desai, C.S.; Lee, S.C.; Singal, A.G.; et al. What Survivorship Means to Liver Transplant Recipients: Qualitative Groundwork for a Survivorship Conceptual Model. Liver Transplant. 2021, 27, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paslakis, G.; Beckmann, M.; Beckebaum, S.; Klein, C.; Gräf, J.; Erim, Y. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Quality of Life, and the Subjective Experience in Liver Transplant Recipients. Prog. Transplant. 2017, 28, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Campanozzi, L.L.; Ricci, G.; Tartaglini, D.; Tambone, V. Towards a Transversal Definition of Psychological Resilience: A Literature Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.C.; Fehon, D.C.; Treloar, H.; Ng, R.; Sledge, W.H. Resilience in Organ Transplantation: An Application of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD–RISC) With Liver Transplant Candidates. J. Pers. Assess. 2015, 97, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. .; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Borda-Mas, M.; Avargues-Navarro, M.L.; Pérez-Bernal, J.; Conrad, R.; Gómez-Bravo, M.. Post-traumatic growth and its relationship to quality of life up to 9 years after liver transplantation: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017455–e017455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funuyet-Salas, J.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Borda-Mas, M.; Avargues-Navarro, M.L.; Gómez-Bravo, M. .; Romero-Gómez, M.; Conrad, R.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.. Relationship Between Self-Perceived Health, Vitality, and Posttraumatic Growth in Liver Transplant Recipients. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruckenberg, K.M.; Shenai, N.; Dew, M.A.; Switzer, G.; Hughes, C.; DiMartini, A.F. Transplant-related trauma, personal growth and alcohol use outcomes in a cohort of patients receiving transplants for alcohol associated liver disease. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 72, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. .; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Borda-Mas, M.; Avargues-Navarro, M.L.; Pérez-Bernal, J.; Gómez-Bravo, M.. Coping Strategies in Liver Transplant Recipients and Caregivers According to Patient Posttraumatic Growth. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.Á.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez-Martín, M.; Borda-Mas, M.; Avargues-Navarro, M.L.; Gómez-Bravo, M.Á.; et al. Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Transplant Effects Questionnaire (TxEQ-Spanish) in Liver Transplant Recipients and Its Relationship to Posttraumatic Growth and Quality of Life. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 18;9.

- Jiménez-Picón, N.; Romero-Martín, M. Necesidad de incluir la perspectiva de género en la investigación. Gac Sanit. 2020, 34, 628–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, M.M.; Fard, D.; Basida, S.D.; Obeidat, A.E.; Darweesh, M.; Mahfouz, R.; Ahmad, A. Disparities in Social Determinants of Health Among Patients Receiving Liver Transplant: Analysis of the National Inpatient Sample From 2016 to 2019. Cureus 2022, 14, e26567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.C.; Pomfret, E.A.; Verna, E.C. Implicit bias and the gender inequity in liver transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melk, A.; Babitsch, B.; Borchert-Mörlins, B.; Claas, F.; Dipchand, A.I.; Eifert, S.; Eiz-Vesper, B.; Epping, J.; Falk, C.S.; Foster, B.; et al. Equally Interchangeable? How Sex and Gender Affect Transplantation. Transplantation 2019, 103, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listabarth, S.; König, D.; Berlakovich, G.; Munda, P.; Ferenci, P.; Kollmann, D.; Gyöeri, G.; Waldhoer, T.; Groemer, M.; van Enckevort, A.; et al. Sex Disparities in Outcome of Patients with Alcohol-Related Liver Cirrhosis within the Eurotransplant Network—A Competing Risk Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendall, M.S.; Weden, M.M.; Favreault, M.M.; Waldron, H. The Protective Effect of Marriage for Survival: A Review and Update. Demography 2011, 48, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, J.T.; Gorman, B.K.; Barrera, C.B. Families, Resources, and Adult Health. J Health Soc Behav. 2013, 54, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucquemont, J.; Pai, A.L.; Dharnidharka, V.R.; Hebert, D.; Furth, S.L.; Foster, B.J. Gender Differences in Medication Adherence Among Adolescent and Young Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2019, 103, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Shih, F.-J.; Hu, R.-H.; Sheu, S.-J. Comparing the different viewpoints on overseas transplantation demands between genders and roles. Medicine 2021, 100, e23650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Equidad según sexo y de género en la investigación: justificación de las guías SAGER y recomendaciones para su uso. Gac Sanit. 2019, 33, 203–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Nacional de Trasplantes. Memoria actividad donación y trasplante hepático. España 2021. Madrid, España.; 2021. Available from: http://www.ont.es/infesp/Memorias/ACTIVIDAD DE DONACIÓN Y TRASPLANTE HEPÁTICO ESPAÑA 2021.

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García León, M.Á.; González-Gomez, A.; Robles-Ortega, H.; Padilla, J.L.; Peralta-Ramirez, I. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Resiliencia de Connor y Davidson (CD-RISC) en población española. An Psicol. 2018, 35, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broche-p, Y.; Abreu, M.; Villas, L.; Rodríguez, B.C.; Abreu, M.V.L. Escala de Resiliencia de Connor-Davidson (CD-RISC). Feijoo. 2012, 1, 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, T.; Berger, R. Reliability and Validity of a Spanish Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Res. Soc. Work. Pr. 2006, 16, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13 (Suppl. 1), 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M.; Avargues-Navarro, M.; Borda-Mas, M.; Pérez-Bernal, J.; Gómez-Bravo, M. How Thinking About the Donor Influences Post-traumatic Growth in Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burra, P.; De Martin, E.; Gitto, S.; Villa, E. Influence of Age and Gender Before and After Liver Transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2013, 19, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, K.L.; Andrei, A.-C.; Li, Z.; Rybarczyk, B.; White-Williams, C.; Gordon, R.; McGee, E.C. Gender differences in appraisal of stress and coping 5 years after heart transplantation. Hear. Lung 2015, 45, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszek, A.; Wróblewska, A.; Zdankiewicz-Ścigała, E.; Rzońca, P.; Gałązkowski, R.; Gozdowska, J.; Lewandowska, D.; Kosson, D.; Kosieradzki, M.; Danielewicz, R. Post-Traumatic Growth among Patients after Living and Cadaveric Donor Kidney Transplantation: The Role of Resilience and Alexithymia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, I.P.; Tanner, M.K.; Greenwood, B.N.; Baratta, M.V. Sex differences in resilience: Experiential factors and their mechanisms. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 52, 2530–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabeih, M.; Bokek-Cohen, Y.; Azuri, P. Health-related quality of life of transplant recipients: a comparison between lung, kidney, heart, and liver recipients. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaisbourd, Y.; Dahhou, M.; Zhang, X.; Sapir-Pichhadze, R.; Cardinal, H.; Johnston, O.; Blydt-Hansen, T.D.; Tibbles, L.A.; Hamiwka, L.; Urschel, S.; et al. Differences in medication adherence by sex and organ type among adolescent and young adult solid organ transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 2022, 27, e14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onghena, L.; Develtere, W.; Poppe, C.; Geerts, A.; Troisi, R.; Vanlander, A.; Berrevoet, F.; Rogiers, X.; Van Vlierberghe, H.; Verhelst, X. Quality of life after liver transplantation: State of the art. World J. Hepatol. 2016, 8, 749–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, J.; Schieber, K.; Reber, S.; Jank, S.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Grundmann, F.; Vitinius, F.; de Zwaan, M.; Bertram, A.; Erim, Y. Psychological processing of a kidney transplantation, perceived quality of life, and immunosuppressant medication adherence. Patient Preference Adherence 2019, 13, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).