1. Introduction

Sustainable water management in agriculture is a pressing global concern as water scarcity, environmental degradation, and food security challenges escalate. The need for effective water management practices is particularly pronounced in East Africa, a region grappling with a complex interplay of climate variability, population growth, and economic constraints [

1]. Globally, scholars emphasize adopting sustainable water management practices to ensure long-term agricultural productivity and resilience [

2]. This framework encompasses strategies, including efficient irrigation technologies, rainwater harvesting, and integrated water resource management [

3].

Globally, water scarcity poses a significant threat to agricultural sustainability, with a growing population intensifying the demand for water resources. Scholars emphasize adopting sustainable water management practices to ensure long-term farm productivity and resilience [

2]. The framework for sustainable water management encompasses a range of strategies, including efficient irrigation technologies, rainwater harvesting, and integrated water resource management [

3]. Sustainable water management in agriculture has arisen as a major global concern, particularly in East Africa, where water shortages, climate change, and population increase all offer substantial challenges to agricultural production and food security. Effective water management strategies are urgently required to ensure agricultural systems' long-term viability and community well-being. In East Africa, consisting of countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Rwanda, the challenges in managing water resources for agriculture are distinct. The region faces susceptibility to climate change-induced droughts and erratic rainfall patterns, aggravating water scarcity and impacting crop yields and livelihoods [

4,

5]. Rapid population growth and competing demands for water from various sectors further intensify the pressure on available water resources [

6].

East Africa is facing a complicated combination of causes that exacerbates water constraint. Climate variability, such as unexpected rainfall patterns and long-term droughts, has a considerable impact on agricultural water supply. Rapid population expansion and urbanization put additional strain on water resources, resulting in rivalry among sectors such as agriculture, home consumption, and industry. Furthermore, the region's sensitivity to climate change-induced effects, such as rising temperatures and changed precipitation regimes, exacerbates the issues of water management.

Sustainable water management practices play a pivotal role in addressing the complex challenges associated with water scarcity, environmental degradation, and the increasing demands of agriculture in East Africa. This section provides a comprehensive overview of key sustainable water management practices, drawing insights from various studies and research findings to illuminate the multifaceted nature of these strategies. A. Efficient water use is fundamental to sustainable water management. Precision irrigation, rainwater harvesting, and soil moisture management are integral to optimizing water use efficiency in agriculture [

7,

8,

9]. These strategies enhance crop productivity and contribute to water resource conservation, ensuring a reasonable utilization of this precious commodity. B. Innovative and eco-friendly irrigation techniques, including drip and sprinkler irrigation, are gaining prominence for reducing water wastage and minimizing environmental impact [

8,

10,

11,

12]. These technologies enhance precision in water delivery, promoting a more sustainable approach to irrigation that aligns with the principles of resource conservation and environmental stewardship. C. Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) emphasizes a holistic approach that considers the interconnectedness of water sources, land use, and ecosystem health [

7,

13,

14]. IWRM frameworks facilitate coordinated decision-making, recognizing the interdependencies between different water uses and ensuring a balanced and sustainable allocation of water resources [

14]. D. Given the increasing impacts of climate change, incorporating climate-resilient strategies is crucial for sustainable water management [

15,

16,

17]. This includes adaptive measures considering changing precipitation patterns, temperature variations, and evolving climatic conditions. Climate-resilient water management practices contribute to the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems in the face of environmental uncertainties. E. Inclusive and participatory approaches involving local communities are essential for successful sustainable water management practices [

18,

19,

20]. Engaging stakeholders in decision-making processes, acknowledging indigenous knowledge, and fostering community-led initiatives contribute to the social acceptability and effectiveness of water management interventions. F. A holistic approach to sustainable water management necessitates focusing on water quality and quantity considerations [

21,

22,

23]. Monitoring and protecting water quality involves assessing the potential impacts of agricultural activities on water bodies, mitigating contamination risks, and ensuring that water resources remain safe for both ecosystems and human consumption. G. Effective governance and policy integration are critical for sustainable water management practices [

19,

24,

25]. Coordinated efforts at local, national, and regional levels, coupled with formulating adaptive policies that consider socio-economic and environmental dynamics, are essential for fostering a supportive and enabling environment for sustainable water management.

2. Materials and Methods

This review examines at the current status of research on sustainable water management strategies in East African agriculture. It identifies six critical gaps that must be addressed to ensure the development and implementation of effective and equitable policies.

Limited focus on socioeconomic impacts: Existing research frequently stresses technical issues while ignoring the larger social and economic ramifications of water management strategies. A better knowledge of how these methods impact farmers' livelihoods, income, and well-being is critical for their broad adoption. Interventions should be evaluated for cost-effectiveness and social equality in order to enhance both agricultural productivity and local communities.

Insufficient attention to gender dynamics: Women's roles in water management are frequently disregarded, despite their significant involvement in water-related activities. Research should investigate how practices affect men and women differently, addressing gender-specific obstacles and possibilities. Strategies for ensuring equitable access to water resources and involvement in decision-making processes are critical to successful implementation.

Lack of Long-Term Impact Assessment: Most studies concentrate on short-term results, ignoring the long-term viability and potential unintended consequences of interventions. Longitudinal research is required to examine the sustainability of activities, their impact on ecosystems over time, and potential trade-offs. This understanding enables the development of resilient methods that can respond to changing environmental and socioeconomic conditions.

Limited integration of Indigenous knowledge: Indigenous groups have unique knowledge about local ecosystems and water dynamics, which is often disregarded in modern techniques. Research should look into how to incorporate this knowledge into long-term water management plans to improve their effectiveness and cultural sensitivity. Collaborative and participatory research methodologies that empower local populations while respecting their traditional wisdom are critical.

Insufficient Consideration of Climate Change Adaptation: The emphasis on reducing climate change impacts overshadows water management methods' ability to develop resilience. Research should look into how these methods can help with climate change adaptation and improve the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems. Understanding the interplay between water management and climate adaptation is critical for establishing effective treatments to address changing climatic trends.

Inadequate investigation of policy implementation challenges: While policy frameworks exist, there has been little research on the obstacles of applying them at the local level. A sophisticated understanding of how policies are perceived, interpreted, and implemented in various socioeconomic and cultural situations is required. Researchers should look at the social, economic, and political elements that influence policy implementation, such as stakeholder interests and institutional capacities.

Incomplete Assessment of Water Quality Implications: The emphasis on water quantity frequently overlooks the possible water quality concerns linked with agricultural operations. Water management strategies should be evaluated for their impact on nutrient runoff, soil erosion, and water source contamination. A comprehensive approach is required to guarantee that actions address both water quantity and quality issues while protecting human health and aquatic ecosystems.

These limitations indicate the need for a broader approach to studying sustainable water management in East African agriculture. Addressing these concerns allows researchers to contribute to the creation of equitable, effective, and long-term solutions that benefit farmers, communities, and the environment.

2.1. Methodology

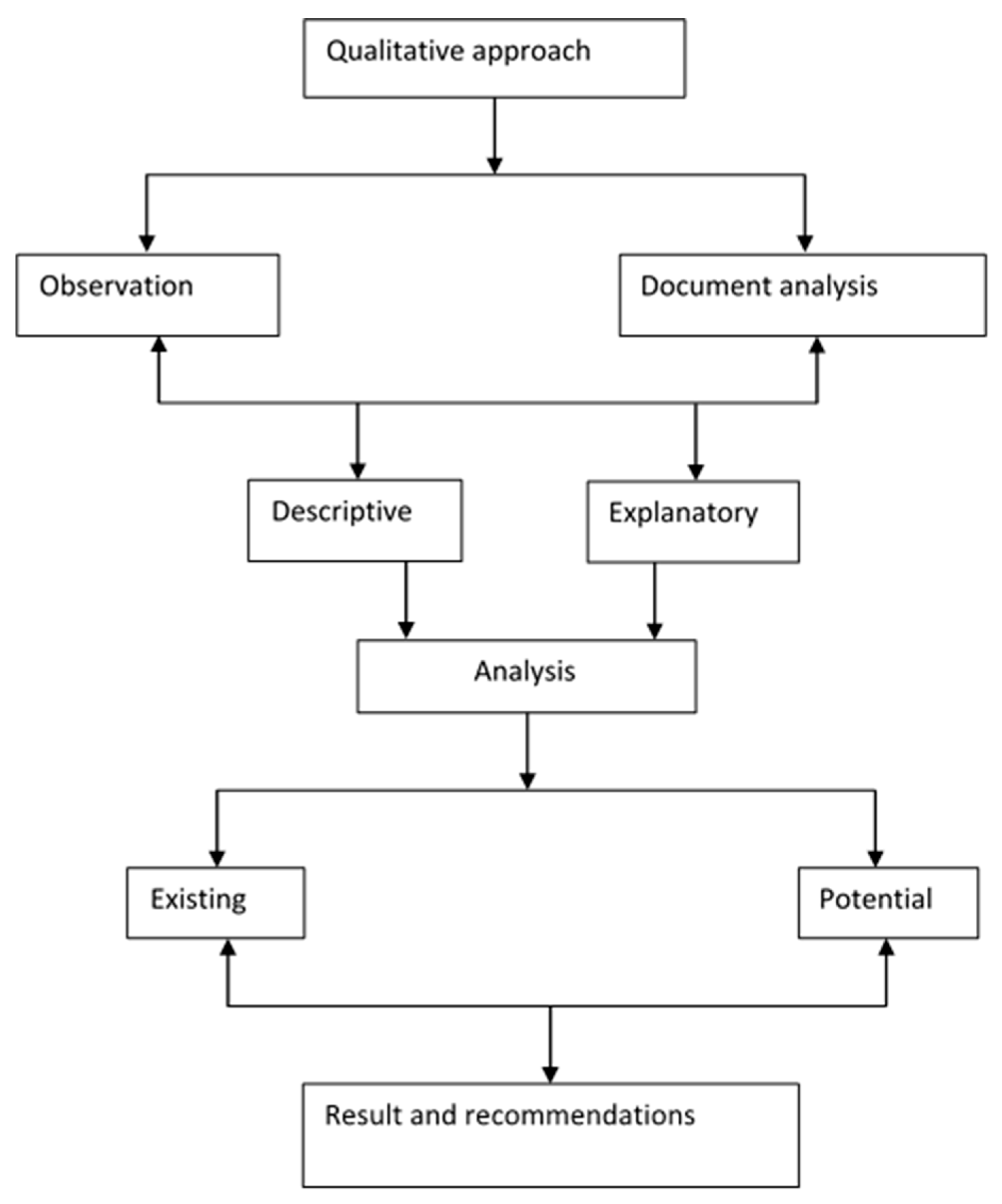

The study used a two-pronged methodology to identify key water management concerns in East Africa. The first component involved a systematic literature review, which consisted of three stages. First, relevant research publications were found using academic databases. Second, these publications were thoroughly reviewed against pre-determined exclusion criteria to confirm their relevance to the study's objectives. Finally, the chosen publications were thoroughly examined to extract crucial information and insights.

The methodology's second component focuses on secondary data analysis. This method entailed extracting important indicators from these sources and assessing the trends in water management techniques over time. By combining these two techniques, the study attempted to provide a thorough understanding of East Africa's complicated water management concerns.

2.1.1. Literature Selection Process

To ensure the relevance and quality of the included studies, a thorough screening process was used. Articles were initially evaluated based on their relevance to the study's special emphasis on water management methods and concerns in East Africa. This entailed determining the geographical extent of the study area in order to confirm its relevance to the region of interest. Furthermore, the conceptual scope of each article was assessed to see if it provided insights into sustainable water management techniques and their components in the East African setting. Studies that went beyond the scope of water management practices were eliminated from further evaluation.

A second layer of screening was used to improve the selection of articles. This step focused on the extent to which the research took into account diverse water management techniques. The goal was to find articles that investigated the interconnection of various water management components, such as water supply, sanitation, and irrigation. Studies that focused only on a particular water management component were judged insufficient for the purposes of this study.

2.1.2. Data Extraction and Curation

Database construction was a two-step approach that entailed extracting biometric data from Scopus and manually characterizing research using the Nexus framework. The first phase, biometric data extraction, used Scopus' automatic metadata characterization tool. This allowed for the export of a saved list of studies into a CSV file, capturing important metadata such as author names, publication year, journal title, and abstract. The second phase, study characterization, required manual curation based on a specified data registration template. Each study received a unique ID based on its Scopus metadata. Relevant data was then properly documented in designated columns of the template. This includes information about water management strategies, specific indicators, and research methodologies.

2.1.3. A Bibliometric and Post-Bibliometric Analysis of Water Management Research

A bibliometric analytic strategy was used in this systematic review to thoroughly evaluate the corpus of research on water management techniques. Metadata taken from one of the top academic research platforms, the Scopus database, was analyzed. During this first stage, a comprehensive review of the publication environment was conducted, covering important elements like the publication history, temporal trends, and the most popular author-selected keywords. This data gave important insights into how this field of study has developed and what the main areas of scientific inquiry are. A more thorough post-bibliometric investigation was conducted in order to build on this fundamental understanding. During this step, the methodological approaches used in each study on water management practices were painstakingly extracted by hand. In order to provide a structured repository for additional research and synthesis, the retrieved data was methodically arranged into an Excel database. A thorough analysis of the various methodological frameworks employed by researchers in this field was made possible by the granular level of data collecting (

Figure 1).

This systematic review sought to offer a thorough and nuanced grasp of the current state of knowledge on water management methods by integrating these two analytical methodologies. A macro-level viewpoint was provided by the bibliometric study, which identified broad trends and patterns in the field of research. However, by delving into the specifics of individual research, the post-bibliometric analysis allowed for a critical evaluation of the field's methodological diversity, strengths, and shortcomings. These two complimentary methods worked well together to give a strong basis for the results' later synthesis and interpretation.

2.2. Study Area

The rapidly growing population in East Africa has led to a surge in water demand, placing immense pressure on the region's already strained water resources. While countries in the region are focused on meeting immediate needs, long-term challenges like climate change, inadequate water storage, and vulnerability to extreme weather events remain largely unaddressed. Agriculture serves as the backbone of many East African economies, with irrigated agriculture and energy production identified as key drivers for enhancing food and nutritional security. However, the region's water scarcity poses significant challenges to the development of these sectors. As countries strive to expand their agricultural and energy capabilities, the insufficient water supply threatens to undermine these efforts and exacerbate existing water scarcity issues.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Identifying Gaps in Research on Sustainable Water Management in East African Agriculture

The field of sustainable water management in East African agriculture presents a significant knowledge gap, particularly regarding the socio-economic impacts of implemented practices. While extensive research exists on the technical aspects of water management, there is a notable lack of studies focusing on the broader implications for farmers' livelihoods, income, and well-being. [

26,

27]. This oversight hinders a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of sustainable water management and its potential repercussions on local communities. To promote the widespread adoption of sustainable water management strategies, it is crucial to investigate how these interventions affect farmers' lives. This includes assessing their economic viability and social equity implications, ensuring that they contribute positively to agricultural productivity and the welfare of local communities. By addressing this research gap, we can gain valuable insights into the real-world impact of sustainable water management practices and develop more effective strategies to support both agricultural sustainability and rural development in East Africa.

Understanding the socio-economic dynamics is pivotal for evaluating the success and acceptance of sustainable water management strategies within East African agricultural settings. Farmers, as key stakeholders, are directly affected by these interventions, and an in-depth analysis of how such practices influence their economic viability and social well-being is imperative [

28,

29,

30]. A study by [

28,

31,

32] underscores the significance of considering the broader socio-economic context, emphasizing the need for a holistic evaluation that extends beyond technical efficiency to encompass the socio-economic landscape. In addition, the economic viability of sustainable water management practices is closely tied to their adoption and long-term success. A thorough investigation into the financial implications would shed light on the cost-effectiveness of these strategies, aiding policymakers and practitioners in designing interventions that are not only environmentally sustainable but also financially viable for farmers [

7,

32]. Moreover, it would contribute to the identification of potential barriers or challenges that may hinder the widespread adoption of sustainable water management practices across diverse socio-economic contexts within East Africa.

Social equity considerations further amplify the need for research in this domain. An in-depth exploration of the social distribution of benefits and burdens associated with sustainable water management practices is essential to ensure that these interventions contribute positively to the welfare of local communities [

25,

33]. Inclusive practices considering different social groups' diverse needs and capacities, including marginalized populations, are critical for fostering equitable outcomes. Moreover, a nuanced understanding of the socio-economic impacts can unveil potential trade-offs and synergies between agricultural productivity and community welfare. For instance, a sustainable water management practice that enhances crop yields might positively impact farmers' income but may also have unintended consequences on other aspects of community well-being. Only through a comprehensive analysis of the socio-economic dimensions can researchers and policymakers develop strategies that optimize agricultural productivity and local communities' overall welfare.

3.1.1. Insufficient Attention to Gender Dynamics

An evident oversight exists within sustainable water management in East African agriculture, as gender considerations are largely neglected in the existing literature. While women's roles in crucial water-related activities, such as irrigation and water fetching, are acknowledged, their specific needs, challenges, and contributions remain marginalized in scholarly discussions [

34,

35,

36,

37]. This lack of attention to gender dynamics poses significant implications for the region's effectiveness and equity of sustainable water management practices. Women's roles in water-related tasks are often integral to agricultural processes, as highlighted by [

37]. However, the gendered dimensions of these roles, including their impact on women's time, health, and overall well-being, are frequently overshadowed in the existing discourse. Ignoring these dynamics can perpetuate gender inequalities and hinder the potential success of sustainable water management interventions.

Understanding how sustainable water management practices impact men and women differently is essential for developing inclusive and effective strategies. Women may face unique challenges related to access to water resources, time constraints, and the burden of multiple responsibilities. Conversely, they may also possess valuable insights into local water dynamics and contribute innovative solutions that remain untapped due to the prevailing oversight [

33,

37]. Acknowledging and addressing these gender-specific distinctions is a matter of social justice and a fundamental aspect of ensuring the sustainability and acceptance of water management practices.

Thus, to rectify this gap, future research endeavours should intentionally incorporate a gender lens in studying sustainable water management in East African agriculture. This involves exploring how water management practices intersect with existing gender roles, norms, and power structures. Such research should go beyond tokenistic inclusion and actively seek women's perspectives in the community, ensuring their voices are heard, and their experiences inform policy and practice. Strategies to provide equitable access to water resources must be identified and implemented. This could involve the development of targeted interventions that consider the specific needs of women, recognizing the diversity of their roles in agriculture and water management. Moreover, promoting women's participation in decision-making processes related to water governance can contribute to more inclusive and effective policies [

37].

3.1.2. Lack of Long-Term Impact Assessment:

While numerous studies contribute valuable insights into the short-term impacts of sustainable water management practices, a notable gap exists in assessing their long-term effects on agricultural landscapes and ecosystems. Most existing literature tends to focus on immediate outcomes, such as changes in crop yields or water use efficiency, providing a limited understanding of the enduring consequences of these interventions. Comprehensive longitudinal studies are imperative to unravel sustainable water management practices' sustained benefits and potential drawbacks over extended periods [

7,

26,

28,

38]. [

7,

39] underscored the importance of longitudinal studies, which advocate for a more holistic evaluation of sustainable water management practices that extend beyond short-term gains. Such studies allow researchers to trace the evolution of impacts, addressing questions related to the persistence of positive outcomes and the emergence of potential negative consequences over time. [

10,

40] further emphasize the need for extended timeframes in research, noting that ecological processes and adaptations to sustainable practices may unfold gradually and become apparent only in the long run.

By assessing the durability of interventions, researchers can provide nuanced recommendations beyond immediate effectiveness. Longitudinal studies enable a more robust understanding of the adaptive capacity of agricultural ecosystems to sustainable water management practices. This, in turn, aids policymakers and practitioners in formulating resilient strategies that can withstand dynamic environmental and socio-economic changes [

28]. Furthermore, a comprehensive long-term assessment allows for the identification of potential trade-offs and unintended consequences. For instance, a sustainable water management practice that initially enhances crop yields may lead to shifts in land use or alterations in nutrient cycling that have adverse effects in the long run[

10,

38]. Understanding these complexities is vital for devising sustainable interventions that optimize agricultural productivity and environmental health. In light of these considerations, future research in sustainable water management should prioritize longitudinal studies that span multiple growing seasons and account for variations in climate and other contextual factors. Integrating such temporal dimensions into research designs will provide a more accurate depiction of the dynamic relationships between water management practices, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem health. This, in turn, will contribute to developing robust policies and practices that stand the test of time, ensuring sustainable outcomes in East African agriculture.

3.1.3. Limited Integration of Indigenous Knowledge:

Integrating indigenous knowledge systems into sustainable water management practices remains a critical but frequently overlooked aspect in the current research landscape. Indigenous communities across East Africa possess unique and valuable insights into local ecosystems, water dynamics, and sustainable agricultural practices [

41,

42,

43]. Despite this, there is a pervasive gap in acknowledging and incorporating this wealth of traditional wisdom into modern water management strategies, hindering the development of more holistic and culturally sensitive approaches to sustainability [

44,

45,

46]. [

34,

45] highlight the potential benefits of integrating indigenous knowledge, emphasizing that local communities often deeply understand their environments, including seasonal patterns, soil characteristics, and water availability. Indigenous knowledge can provide valuable insights into sustainable water management practices, offering context-specific solutions rooted in the community's socio-cultural fabric [

43]. However, the current lack of integration often results in disconnect between formal water management strategies and the lived experiences of indigenous communities.

Exploring ways to bridge this gap is essential for fostering more inclusive and effective sustainable water management practices. Future studies should actively engage with indigenous communities, recognizing their role as land stewards and repositories of valuable ecological knowledge [

47]. This engagement should go beyond tokenistic inclusion, involving collaborative and participatory research approaches that empower local communities to contribute actively to the design and implementation of sustainable water management strategies [

46]. Moreover, building partnerships between indigenous communities and external stakeholders, including researchers, policymakers, and non-governmental organizations, is crucial. Such partnerships can facilitate the co-creation of knowledge, ensuring that traditional wisdom is acknowledged and integrated into broader water management frameworks [

43]. This collaborative approach respects the autonomy of indigenous communities and recognizes their agency in shaping sustainable water practices.

Culturally sensitive water management practices enhance the effectiveness of interventions and contribute to communities' resilience and adaptive capacity in the face of environmental changes [

47]. Recognizing the interconnectedness of indigenous knowledge with ecological sustainability can lead to more sustainable and contextually appropriate water management strategies that align with the values and aspirations of local communities [

46].

3.1.4. Inadequate Consideration of Climate Change Adaptation:

The vulnerability of East Africa to climate change poses a pressing challenge for agricultural sustainability, making it imperative to understand how sustainable water management practices contribute to climate change adaptation in the region. However, a significant gap exists in the current literature, where the emphasis on mitigating the impacts of climate change overshadows the potential of these practices to build resilience within farming communities [

7,

16,

48]. While many studies focus on short-term strategies to mitigate the immediate impacts of climate change, there is insufficient attention to the long-term adaptation measures that can enhance the resilience of agricultural systems in the face of evolving climatic conditions. Sustainable water management practices have the potential to address current challenges and contribute significantly to building adaptive capacity within farming communities.

Understanding the synergies between sustainable water management and climate change adaptation is crucial for developing actionable insights to inform policies and practices. [

7,

49] advocate for a more integrated approach, considering the intricate connections between water management, agriculture, and climate resilience. Such an approach involves optimizing water use efficiency and incorporating adaptive strategies that anticipate and respond to changing climate patterns. This integrated perspective is essential for developing comprehensive and context-specific solutions that account for the complex interactions between water availability, agricultural productivity, and climate variability. Moreover, research should explore the socio-economic dimensions of climate change adaptation through sustainable water management. [

16], argue that understanding adaptation's social and economic aspects is as crucial as technical solutions. Examining how these practices influence farmers' adaptive capacity, income stability, and overall well-being is essential for designing strategies that are not only environmentally sustainable but also socially and economically inclusive.

Future studies should, therefore, delve into the specific mechanisms through which sustainable water management practices contribute to climate change adaptation in East African agriculture. This includes evaluating the role of water-efficient irrigation technologies, rainwater harvesting, and integrated water resource management in enhancing the resilience of farming systems [

16]. Additionally, research should explore the potential trade-offs and co-benefits between climate change adaptation and other sustainability goals, ensuring that interventions contribute positively to multiple dimensions of agricultural and environmental well-being [

7].

3.1.5. Sparse Exploration of Policy Implementation Challenges:

Although various studies acknowledge policy frameworks concerning water management, there remains a conspicuous dearth in the literature regarding an in-depth exploration of challenges associated with policy implementation, especially at the grassroots level. While the importance of robust policy frameworks is evident, understanding the practical hurdles and barriers hindering the seamless translation of these policies into actionable practices is paramount for designing effective and sustainable interventions [

18,

19,

25]. Policy implementation challenges often manifest in discrepancies between theoretical frameworks and on-the-ground realities. Research by [

50] emphasizes the need for a more nuanced understanding of how policies are received, interpreted, and executed locally. This includes considerations of the socio-economic, cultural, and political contexts that shape the reception and effectiveness of water management policies. Without addressing these contextual factors, policies may encounter resistance or fail to resonate with local communities' diverse needs and circumstances.

Moreover, the complexities of policy implementation go beyond the technical aspects and involve intricate social dynamics. [

25,

51] argue for a comprehensive exploration of the social, economic, and political factors that influence the successful implementation of water management policies. This involves understanding the power relations, stakeholder interests, and institutional capacities that play a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of policy implementation. Research should, therefore, scrutinize how these factors influence the acceptance, compliance, and adaptation of water management policies by diverse stakeholders. Hence, future research should adopt a multi-dimensional approach to overcome the challenges associated with policy implementation. [

19], underscores the importance of engaging with stakeholders at various levels, including local communities, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations. Such engagement is essential for identifying the obstacles that impede the effective translation of policies into practice and formulating context-specific strategies to address these challenges.

Furthermore, research should assess the role of capacity-building initiatives in enhancing the implementation of water management policies. Capacity-building involves improving individuals' technical skills and strengthening institutional capacities for policy enforcement and community engagement [

18,

27,

52]. Understanding how capacity-building interventions can be tailored to local needs and how they contribute to overcoming implementation challenges is crucial for fostering sustainable water management practices.

3.1.6. Incomplete Assessment of Water Quality Implications

The existing literature on sustainable water management in agriculture often prioritizes concerns related to water quantity, leaving a noticeable gap in the comprehensive assessment of water quality implications associated with sustainable practices. While the focus on water quantity is essential, a thorough understanding of water quality is equally crucial, considering the potential contamination risks posed by agricultural inputs like fertilizers and pesticides [

21,

22,

53]. Studies have shown that agricultural activities can contribute to water quality degradation, with the runoff of agrochemicals and nutrients into water bodies adversely affecting human health and aquatic ecosystems [

54,

55]. Neglecting the assessment of water quality implications can result in unforeseen environmental and health consequences. Therefore, a more holistic approach is needed to ensure that sustainable water management practices address quantity concerns and uphold the integrity of local water sources.

[

20,

56], research highlights the need for an integrated assessment that considers the intricate connections between agricultural practices and water quality. This involves evaluating the impact of sustainable water management practices on nutrient runoff, soil erosion, and the introduction of contaminants into water bodies. Adams et al. (2019) further stress the importance of monitoring and modelling approaches to understand the dynamic interactions between agricultural activities and water quality over time. Future research endeavours should incorporate advanced analytical techniques to assess water quality, including identifying emerging contaminants and evaluating potential cumulative impacts on aquatic ecosystems [

30,

54,

57]. Additionally, studies should consider the socio-economic implications of compromised water quality, as it directly affects communities dependent on these water sources for drinking and agriculture [

21,

58,

59]. This socio-ecological perspective is essential for formulating effective and socially equitable water management strategies.

Furthermore, the assessment of water quality implications should extend beyond traditional agricultural pollutants to encompass broader environmental considerations, such as the impact of climate change on water quality parameters [

57,

60]. Changes in precipitation patterns, temperature, and land use can influence the transport and fate of contaminants in water bodies, adding another layer of complexity to the relationship between agricultural practices and water quality.

Table 1.

Case studies Addressing Gaps in Sustainable water management research in East Africa.

Table 1.

Case studies Addressing Gaps in Sustainable water management research in East Africa.

| Case Study |

Description |

Key Practices |

Reference |

| 1.Socio-economic Impact Assessment in Uganda |

A comprehensive study evaluating the socio-economic impacts of sustainable water management practices. Assessing effects on farmers' livelihoods, income, and overall well-being |

-Socio-economic impact assessment

-Community engagement and participatory approaches |

[18,61,62,63] |

| 2.Gender-inclusive water management in Kenya |

In-depth exploration of gender dynamics in water management, highlighting women's roles in water-related activities. Identifying strategies for equitable access to water resources. |

-Gender-sensitive water management

-Community participation and empowerment |

[18,37] |

| 3.Long-term Impact Assessment in Ethiopia |

Longitudinal study assessing sustainable water management practices' sustained benefits and drawbacks over extended periods, providing nuanced recommendations for policymakers. |

-Long-term impact assessment

-Adaptive management strategies |

[7,16] |

| 4.Integration of indigenous knowledge in Tanzania |

Exploration of ways to integrate indigenous knowledge systems into sustainable water management practices. Enhancing the relevance and effectiveness of interventions. |

-Integration of indigenous knowledge

-Collaborative approaches with local communities |

[18,45] |

| 5.Climate resilient water management in Rwanda |

Investigating the synergies between sustainable water management and climate change adaptation. Providing actionable insights for policymakers addressing climate-related shocks. |

-Climate-resilient water management

-Adaptive strategies for climate change |

[16,48] |

| 6.Policy implementation challenges in Kenya and Uganda |

In-depth exploration of challenges associated with policy implementation at the ground level. Identifying barriers and strategies for effective policy translation into actionable practices. |

-Policy implementation challenges

-Stakeholder engagement and context-specific strategies |

[19,25] |

3.2. Economic Implications: Analyze the Economic Aspects of Sustainable Water Management in Agriculture

3.2.1. The Cost-Effectiveness and Benefits for Farmers and Communities

Sustainable water management practices in agriculture have profound economic implications, impacting the cost-effectiveness of farming operations and the overall well-being of farmers and communities. Adopting technologies and strategies geared towards sustainable water use can yield economic benefits by enhancing efficiency and mitigating risks associated with water scarcity. Research by [

64,

65] emphasizes that sustainable water management practices, such as precision irrigation and efficient water delivery systems, contribute to cost savings for farmers. The long-term gains often outweigh the upfront investment in these technologies through improved water use efficiency and increased crop yields. This cost-effectiveness benefits individual farmers and strengthens the economic resilience of entire communities reliant on agriculture.

Furthermore, the economic benefits extend beyond direct cost savings. Sustainable water management practices contribute to agricultural systems' overall health and productivity, promoting long-term sustainability. Studies by [

7] highlight the potential for sustainable intensification of agriculture, where judicious water use leads to higher yields per unit of water input. This supports food security and contributes to the economic viability of farming communities.

3.3. Social and Environmental Impact: Explore Sustainable Water Management's Social and Environmental Implications

3.3.1. Discussion on How Water Management Practices Contribute to Community Well-Being and Ecological Conservation

Sustainable water management practices carry economic benefits and play a pivotal role in shaping social dynamics and environmental well-being. Adopting these practices contributes to community welfare and environmental conservation, fostering a holistic approach to agriculture. In the social context, sustainable water management practices often involve community participation and engagement. Studies by [

25] emphasize the importance of inclusive water governance, where local communities are actively involved in decision-making processes. This empowers communities and ensures that water management strategies align with their needs and priorities.

Moreover, sustainable water management practices contribute to environmental conservation by mitigating the negative impacts of water use on ecosystems. [

22], highlight practices that can reduce the risk of water contamination and preserve the integrity of local water sources. Protecting water quality, alongside efficient water use, ensures the availability of clean water for both agricultural and domestic purposes, positively influencing community health. In summary, sustainable water management practices' social and environmental impact extends far beyond the immediate agricultural context. These practices promote a more sustainable and harmonious relationship between agriculture and its broader socio-environmental context by fostering community engagement and contributing to environmental conservation.

3.4. Opportunities for Improvement:

3.4.1. Enhanced Socio-Economic Integration:

Future interventions should focus on integrating socio-economic considerations into sustainable water management strategies. [

28,

66] suggest the need for comprehensive studies that assess these practices' economic viability and social equity implications, ensuring they positively impact both agricultural productivity and local communities. [

28], highlight the necessity for comprehensive economic studies that delve into the multifaceted impacts of sustainable water management practices. These assessments should go beyond the traditional focus on agricultural productivity, extending to evaluate the broader economic viability of interventions. Examining the economic implications of these practices ensures that they align with the financial realities of farmers and contribute positively to the overall economic landscape.

Sustainable water management strategies should be designed to promote social equity within local communities. Research by [

37,

67] underscores the importance of understanding how these practices may impact different demographic groups, particularly concerning gender dynamics. Implementing gender-sensitive approaches ensures that the benefits and burdens of sustainable water management are distributed equitably, contributing to the community's overall well-being. In addition to economic assessments, incorporating participatory approaches in research and implementation is crucial. Engaging with local communities ensures that the unique social contexts and needs are considered. This approach aligns with the findings of [

45], who emphasize the importance of community involvement in decision-making processes. Participatory approaches enhance the social acceptance and effectiveness of sustainable water management practices.

3.4.2. Gender-Inclusive Approaches:

The studies address and overlook gender dynamics; thus, research efforts should be directed towards understanding how sustainable water management practices impact men and women differently. [

37], emphasizes the importance of gender-sensitive approaches in water management, requiring a deeper exploration of gender dimensions and strategies to ensure equitable access to water resources. [

37], advocates for a comprehensive understanding of how sustainable water management practices affect men and women differently. Such an understanding requires an exploration of the diverse roles and responsibilities that men and women play in water-related activities. Recognizing these differences is crucial for tailoring interventions, considering both genders' unique needs and challenges.

Women often play pivotal roles in water-related activities, such as irrigation and water fetching. However, their specific needs and challenges are frequently ignored in the design and implementation of water management strategies. [

37], emphasizes the importance of recognizing and addressing these disparities, highlighting the need for interventions that alleviate the burden on women and ensure their equitable participation in decision-making processes related to water use. Achieving gender equity in water management involves understanding existing disparities and implementing strategies to rectify them. Future research should explore and propose actionable solutions to bridge the gender gap in access to water resources. Strategies might include the development of gender-sensitive policies, capacity-building programs, and initiatives that empower women in water-related decision-making.

3.4.3. Long-Term Impact Assessment:

A critical gap exists in understanding the long-term effects of sustainable water management practices. Longitudinal studies, as advocated by [

7], are essential for assessing the durability of interventions and providing nuanced recommendations for policymakers and practitioners. This can ensure that solutions work initially and remain resilient over time. [

7], advocate for longitudinal studies to delve into sustainable water management practices' sustained benefits and potential drawbacks. Such studies would provide insights into how interventions evolve over time, allowing for identifying factors that contribute to their long-term success or challenges that may emerge after initial implementation.

Evaluating the durability of interventions is essential to ensure their resilience over time. As highlighted by [

22], sustainable water management practices should be effective initially and resilient in the face of changing environmental conditions and societal dynamics. Longitudinal assessments enable researchers to track the adaptive capacity of these practices and recommend adjustments to enhance their long-term efficacy. Longitudinal studies contribute to the development of holistic recommendations for policymakers and practitioners. By understanding the long-term effects of sustainable water management, researchers can offer nuanced guidance beyond immediate outcomes. This is in line with the findings of [

39], who emphasizes the need for comprehensive assessments to inform policy decisions and ensure the sustained success of water management strategies.

3.4.4. Integration of Indigenous Knowledge:

Bridging the gap between traditional wisdom and modern water management strategies is crucial for a holistic approach. [

45], highlight the importance of incorporating indigenous knowledge systems, suggesting that future studies should explore ways to integrate these valuable insights to enhance the relevance and effectiveness of interventions. Indigenous communities possess valuable insights into local ecosystems and water dynamics. The study by [

45] emphasizes that these insights, accumulated over generations, offer a unique understanding of the intricacies of the environment. Integrating such knowledge into sustainable water management practices can enhance the contextual relevance of interventions, ensuring they align with the specific needs and conditions of the region.

The importance of cultural sensitivity in water management is highlighted by [

13], who argues that indigenous knowledge reflects the cultural context of a community. Recognizing and respecting this cultural context is crucial for the success of water management interventions. Future studies should explore ways to seamlessly integrate traditional wisdom with contemporary strategies, fostering a more holistic and culturally sensitive approach to sustainability. The incorporation of indigenous knowledge is not only about extracting insights but also about empowering local communities. Research by [

22] suggests that involving communities in decision-making processes based on their traditional knowledge enhances their sense of ownership and responsibility. This participatory approach contributes to the sustainable implementation of water management practices, aligning them with the cultural values and practices of the community.

3.4.5. Climate Change Adaptation:

Given East Africa's susceptibility to climate change, research should delve into the synergies between sustainable water management and climate change adaptation. Studies by [

48] emphasize the need to explore how these practices contribute to building resilience within farming communities, providing actionable insights for policymakers to address climate-related shocks. The susceptibility of East Africa to climate change necessitates a comprehensive exploration of sustainable water management practices and their role in climate change adaptation. [

48], stress the importance of understanding how these practices build resilience within farming communities. Integrating sustainable water management strategies with climate adaptation efforts can enhance the capacity of communities to withstand and recover from climate-related shocks, ensuring the continued productivity of agricultural systems.

The work of [

7] underscores the significance of sustainable water management in enhancing adaptive capacity. By efficiently managing water resources, communities can mitigate the impacts of changing climate patterns. As recommended by [

22], longitudinal studies are essential for assessing the effectiveness of sustainable practices in providing long-term adaptive solutions. This approach allows for a dynamic understanding of how these strategies evolve in response to changing climate conditions. Examining the synergies between sustainable water management and climate adaptation aligns with the broader concept of climate-resilient farming. [

16], highlight the need for strategies that address immediate climate challenges and build adaptive capacity over the long term. When integrated into climate-resilient farming practices, sustainable water management offers a multifaceted approach to addressing the complex challenges posed by climate change in East Africa. Insights derived from these studies have direct policy implications. Policies informed by research on the synergies between sustainable water management and climate adaptation, as suggested by [

48], can guide policymakers in developing strategies that strengthen the resilience of farming communities. This involves aligning national and regional policies with sustainable water management practices to ensure a coherent and effective response to climate-related shocks.

4. Conclusions

The study identifies major gaps in research on sustainable water management in East African agriculture. These gaps limit the creation and implementation of effective and equitable policies. One important shortcoming is the lack of emphasis on the socioeconomic implications of water management measures. While research frequently focuses on technical elements, it often ignores the larger social and economic ramifications, notably for farmers' livelihoods and well-being. A greater knowledge of these effects is critical for increasing the adoption of sustainable methods. Another shortcoming is insufficient attention to gender relations. Women's contributions to water management are typically neglected, despite their major involvement in water-related activities. Research should look into how practices influence men and women differently, addressing gender-specific challenges and opportunities.

Additionally, the absence of long-term effect assessments is a big concern. Most studies focus on short-term outcomes, disregarding the long-term viability and potential unintended consequences of interventions. Longitudinal study is required to investigate practice sustainability, long-term ecosystem impact, and potential trade-offs. On the other hand, the insufficient incorporation of indigenous knowledge represents a severe deficit. Indigenous tribes have unique understanding of local ecosystems and water dynamics, which is sometimes overlooked in modern methodologies. Research should look into ways to apply this knowledge into long-term water management plans to improve their effectiveness and cultural sensitivity.

Subsequently poor discussion of climate change adaptation and insufficient study of policy implementation issues are critical gaps that must be addressed. The focus of research should be on how water management methods can help agricultural systems adapt to climate change and increase resilience. Furthermore, a better understanding of the challenges of policy implementation at the local level is required for creating effective interventions. Addressing these disparities is critical to creating equitable, effective, and long-term solutions that benefit farmers, communities, and the environment.

In conclusion, the review of sustainable water management practices in East Africa has shed light on critical dimensions that demand immediate attention for the holistic development of effective strategies. As advocated by [

28], the integrated approach emphasizes the need for policies that intertwine technical considerations with socioeconomic dimensions. Understanding the long-term impact, as suggested by [

7,

22], is crucial for ensuring the durability and resilience of interventions over time. Gender inclusivity, a theme underscored by [

37,

68], calls for strategies that recognize and address women's specific needs and challenges in water-related activities. Furthermore, as highlighted by [

45,

51,

69], incorporating indigenous knowledge systems emerges as an essential aspect of a holistic and culturally sensitive approach to sustainability.

The synergies between sustainable water management and climate change adaptation, emphasized by [

7,

48,

70], underscore the need to develop climate-resilient farming practices. As East Africa faces increasing climate variability and change, integrating water management with adaptive strategies becomes paramount for building resilience within farming communities. As we move forward, policymakers, researchers, and practitioners must heed the recommendations derived from this review. Policies should integrate socio-economic considerations, gender-inclusive strategies, and indigenous knowledge to ensure sustainable water management practices' effectiveness and social equity. Future research directions should explore innovative technologies, cross-regional comparative studies, ecosystem-based approaches, and the dynamics of policy implementation.

5. Recommendations

In addressing the multifaceted challenges of sustainable water management in East Africa, a comprehensive set of recommendations emerges from the existing literature. Policymakers are urged to adopt an integrative approach incorporating socio-economic considerations, ensuring water management practices' economic viability and social equity implications. Active community engagement, as advocated by [

45], is crucial, necessitating participatory approaches to enhance policy effectiveness. Recognizing and rectifying gender imbalances in water management is paramount, focusing on gender-sensitive strategies to ensure equitable access and alleviate the disproportionate burden on women, as highlighted by [

37]. Longitudinal studies, inspired by [

7] and [

22], should be prioritized to assess the durability of interventions and inform the development of enduring strategies for sustained agricultural productivity.

Additionally, integrating indigenous knowledge, as proposed by [

45] and [

22], will enrich the relevance and effectiveness of water management practices by incorporating valuable insights from local communities. Policymakers must also prioritize climate-resilient farming practices, building on the work of [

18] and [

48], to align sustainable water management with climate adaptation efforts, thereby enhancing the overall resilience of farming communities. In moving forward, a coherent strategy must embrace these recommendations, fostering an integrated and adaptive approach to sustainable water management in East Africa.

6. The Way Forward

There are exciting avenues for future research and development in sustainable water management. Future research can explore emerging technologies, such as precision irrigation and smart water management systems, to optimize water use efficiency and reduce wastage. As suggested by [

71], conducting comparative analyses across different regions can provide a broader understanding of sustainable water management practices, allowing for identifying region-specific patterns and successes. Future research can delve into ecosystem-based approaches, incorporating insights from [

22] study to ensure a holistic and integrated management of water resources. In line with [

25], future research should focus on understanding the complexities of policy implementation. Exploring the challenges of translating policies into actionable practices will contribute to more effective interventions.

Author Contributions

A short paragraph specifying their contributions must be provided for research articles with several authors. Thus, M.D worked on Conceptualization, M.D.; methodology, M.O.; validation, M.D. and M.O.; formal analysis, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D and M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.D.; visualization, M.O.; supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data used were indicated in the study and further information will be available upon need.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the SG-NAPI award, generously supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through UNESCO-TWAS, under the financial agreement number FR3240330995. The authors also extend their thanks to the University of Johannesburg for providing a conducive research environment and access to a wealth of literature review papers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Masese, M.A.; Mukhebi, A.; Gor, C. Analysis of Agricultural Extension Service Agents Information Sources and Sorghum Production in Bondo Sub County, Kenya. 2018.

- Russo, M.A.; Santarelli, D.M.; O’Rourke, D. The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe 2017, 13, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO, S., Country Gender Assessment. ETHIOPIA. 2019.

- Conway, D.; Schipper, E.L.F. Adaptation to climate change in Africa: Challenges and opportunities identified from Ethiopia. Global Environmental Change 2011, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, D.; Van Garderen, E.A.; Deryng, D.; Dorling, S.; Krueger, T.; Landman, W.; Lankford, B.; Lebek, K.; Osborn, T.; Ringler, C. Climate and southern Africa's water–energy–food nexus. Nature Climate Change 2015, 5, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, M.K.; Dawa, J.; Nanyingi, M.; Gachohi, J.; Ngere, I.; Letko, M.; Otieno, C.; Gunn, B.M.; Osoro, E. Why is there low morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 in Africa? The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2020, 103, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Williams, J.; Daily, G.; Noble, A.; Matthews, N.; Gordon, L.; Wetterstrand, H.; DeClerck, F.; Shah, M.; Steduto, P. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Román-Sánchez, I.M. Sustainable water use in agriculture: A review of worldwide research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, C.; Sun, D.; Yang, J. Optimization allocation of irrigation water resources based on crop water requirement under considering effective precipitation and uncertainty. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 239, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, T.; Spangenberg, J.H.; Siegmund-Schultze, M.; Kobbe, S.; Feike, T.; Kuebler, D.; Settele, J.; Vorlaufer, T. Identifying governance challenges in ecosystem services management–Conceptual considerations and comparison of global forest cases. Ecosystem services 2018, 32, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sophocleous, M. Two-way coupling of unsaturated-saturated flow by integrating the SWAT and MODFLOW models with application in an irrigation district in arid region of West China. Journal of Arid Land 2011, 3, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Schmidt, S.; Gao, H.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; Chadwick, D.; Tian, J.; Dou, Z.; Zhang, W. A precision compost strategy aligning composts and application methods with target crops and growth environments can increase global food production. Nature Food 2022, 3, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.K. Integrated water resources management: a reassessment: a water forum contribution. Water international 2004, 29, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidanemaraim, J. Participatory integrated water resources management (IWRM) planning: lessons from Berki Catchment, Ethiopia. In Proceedings of Water, sanitation and hygiene: sustainable development and multisectoral approaches. Proceedings of the 34th WEDC International Conference, United Nations Conference Centre, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 18-22 May 2009; pp. 326-333.

- Wada, Y.; Bierkens, M.F.; Roo, A.d.; Dirmeyer, P.A.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Hanasaki, N.; Konar, M.; Liu, J.; Müller Schmied, H.; Oki, T. Human–water interface in hydrological modelling: current status and future directions. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2017, 21, 4169–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; Whitbread, A.; Baedeker, T.; Cairns, J.; Claessens, L.; Baethgen, W.; Bunn, C.; Friedmann, M.; Giller, K.E.; Herrero, M. A framework for priority-setting in climate smart agriculture research. Agricultural Systems 2018, 167, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Flörke, M.; Hanasaki, N.; Eisner, S.; Fischer, G.; Tramberend, S.; Satoh, Y.; Van Vliet, M.; Yillia, P.; Ringler, C. Modeling global water use for the 21st century: The Water Futures and Solutions (WFaS) initiative and its approaches. Geoscientific Model Development 2016, 9, 175–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madajewicz, M.; Pfaff, A.; van Geen, A.; Graziano, J.; Hussein, I.; Momotaj, H.; Sylvi, R.; Ahsan, H. Can information alone both improve awareness and change behavior? Arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Economics 2005.

- Mollinga, P.P. Boundary work and the complexity of natural resources management. Crop Science 2010, 50, S-1–S-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S.; Roobavannan, M.; Kandasamy, J.; Sivapalan, M.; Hombing, D.; Lyu, H.; Rietveld, L. A Socio-Hydrological Perspective on the Economics of Water Resources Development and Management. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science, 2020.

- Adams, S.; Acheampong, A.O. Reducing carbon emissions: the role of renewable energy and democracy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 240, 118245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meter, K.; Van Cappellen, P.; Basu, N. Legacy nitrogen may prevent achievement of water quality goals in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 2018, 360, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masscheleyn, P.H.; Patrick Jr, W.H. Biogeochemical processes affecting selenium cycling in wetlands. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry: An International Journal 1993, 12, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Providoli, I.; Zeleke, G.; Kiteme, B.; Heinimann, A.; von Dach, S.W. From Fragmented to Integrated Knowledge for Sustainable Water and Land Management and Governance in Highland–Lowland Contexts. Mountain Research and Development 2017, 37, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, A.; Adkins, K.G.; Madfis, E. Are the deadliest mass shootings preventable? An assessment of leakage, information reported to law enforcement, and firearms acquisition prior to attacks in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 2019, 35, 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonen, A.; Awualchew, S. Assessment of the performance of selected irrigation schemes in Ethiopia. Zeitschrift für Bewässerungswirtschaft 2009, 44, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ani, K.J.; Jungudo, M.M.; Ojakorotu, V.J.J.o.A.U.S. Aqua-conflicts and hydro-politics in Africa: unfolding the role of African Union water management interventions. 2018, 7, 5-29.

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Gerbens-Leenes, W. The water footprint of global food production. Water 2020, 12, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, M. A socio-hydrological approach for assessing the Eco-system sustainability of water resource development; Abbay/Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. In Proceedings of EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts; p. 5173.

- Zewdie, M.C.; Van Passel, S.; Moretti, M.; Annys, S.; Tenessa, D.B.; Ayele, Z.A.; Tsegaye, E.A.; Cools, J.; Minale, A.S.; Nyssen, J. Pathways how irrigation water affects crop revenue of smallholder farmers in northwest Ethiopia: A mixed approach. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 233, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, M.; Dinka, M.O.; Leta, O.T.; Muluneh, F.B. Impact of Climate Change on Land Suitability for the Optimization of the Irrigation System in the Anger River Basin, Ethiopia. Climate 2020, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teweldebrihan, M.D.; Pande, S.; McClain, M. The dynamics of farmer migration and resettlement in the Dhidhessa River Basin, Ethiopia. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, M.; Dinka, M.O.; Leta, O.T. Implications of Adopting Drip Irrigation System on Crop Yield and Gender-Sensitive Issues: The Case of Haramaya District, Ethiopia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2020, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawit, M.; Dinka, M. Farmer’s Perception of Climate Change with Gender-Sensitive for Optimized Irrigation in a Compound Surface-Groundwater System. Available at SSRN 3399686 2019.

- Ambaw, G.; Tadesse, M.; Mungai, C.; Kuma, S.; Radeny, M.; Tamene, L.; Solomon, D. Gender assessment for women’s economic empowerment in Doyogena climate-smart landscape in Southern Ethiopia. 2019.

- Ogato, G.S.; Boon, E.K.; Subramani, J. Improving access to productive resources and agricultural services through gender empowerment: A case study of three rural communities in Ambo District, Ethiopia. Journal of human Ecology 2009, 27, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R. Women and agricultural productivity: Reframing the Issues. Development policy review 2018, 36, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Falkenmark, M. Agriculture: increase water harvesting in Africa. Nature 2015, 519, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Khan, I.H.; Suman, R. Understanding the potential applications of Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture Sector. Advanced Agrochem 2023, 2, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M.; Rockström, J.; Karlberg, L. Present and future water requirements for feeding humanity. Food security 2009, 1, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermot, E.; Agdas, D.; Rodríguez Díaz, C.R.; Rose, T.; Forcael, E. Improving performance of infrastructure projects in developing countries: An Ecuadorian case study. International Journal of Construction Management 2022, 22, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, Z.; Berkes, F. Role of traditional ecological knowledge in linking cultural and natural capital in cultural landscapes. Reconnecting Natural and Cultural Capital: Contributions from Science and Policy; Paracchini, ML, Zingari, PC, Blasi, C., Eds 2018, 183-193.

- Berkes, F. Sacred ecology; Routledge: 2017.

- Reid, R.S.; Nkedianye, D.; Said, M.Y.; Kaelo, D.; Neselle, M.; Makui, O.; Onetu, L.; Kiruswa, S.; Kamuaro, N.O.; Kristjanson, P. Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 4579–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, A.J.; Carlson, A.K.; Creed, I.F.; Eliason, E.J.; Gell, P.A.; Johnson, P.T.; Kidd, K.A.; MacCormack, T.J.; Olden, J.D.; Ormerod, S.J. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews 2019, 94, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.A.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Maskarinec, S.A.; Eichenberger, E.M.; Shah, P.P.; Carugati, M.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler Jr, V.G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—connecting nature and people. Current opinion in environmental sustainability 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makate, C. Local institutions and indigenous knowledge in adoption and scaling of climate-smart agricultural innovations among sub-Saharan smallholder farmers. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2020, 12, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariom, T.O.; Dimon, E.; Nambeye, E.; Diouf, N.S.; Adelusi, O.O.; Boudalia, S. Climate-smart agriculture in African countries: A Review of strategies and impacts on smallholder farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiwal, D.; Jha, M.K. Hydrologic time series analysis: theory and practice; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012.

- Bernards, N. The World Bank, Agricultural Credit, and the Rise of Neoliberalism in Global Development. New Political Economy 2022, 27, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, M.; Karahan, F.; Manovskii, I.; Mitman, K. Unemployment benefits and unemployment in the great recession: the role of macro effects; National Bureau of Economic Research: 2013.

- Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Xu, Y.J.; Tan, Z. Integrating the JRC Monthly Water History Dataset and Geostatistical Analysis Approach to Quantify Surface Hydrological Connectivity Dynamics in an Ungauged Multi-Lake System. Water 2021, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Lane, C.R.; Li, X.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Clinton, N.; DeVries, B.; Golden, H.E.; Lang, M.W. Integrating LiDAR data and multi-temporal aerial imagery to map wetland inundation dynamics using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 228, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoun, A.J.; Mushet, D.M.; Bell, K.P.; Boix, D.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Isselin-Nondedeu, F. Temporary wetlands: challenges and solutions to conserving a ‘disappearing’ecosystem. Biological Conservation 2017, 211, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, T.; Li, Z.; Sivapalan, M.; Pande, S.; Kandasamy, J.; Savenije, H.; Chanan, A.; Vigneswaran, S. Socio-hydrologic modeling to understand and mediate the competition for water between agriculture development and environmental health: Murrumbidgee River basin, Australia. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2014, 18, 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Sun, S.; Fu, G.; Hall, J.W.; Ni, Y.; He, L.; Yi, J.; Zhao, N.; Du, Y.; Pei, T. Pollution exacerbates China’s water scarcity and its regional inequality. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awulachew, S.B. Irrigation potential in Ethiopia: Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the system. Gates Open Res 2019, 3, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Aldababseh, A., Temimi, M., Maghelal, P., Branch, O. and Wulfmeyer, V.,. Multi-criteria evaluation of irrigated agriculture suitability to achieve food security in an arid environment. Sustainability, 2018, 1-33.

- Adgolign, T.B.; Rao, G.S.; Abbulu, Y. Evaluation of Existing Environmental Protection Policies and Practices vis-à-vis Sustainable Water Resources Development in Didessa Sub-basin, West Ethiopia. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology 2016, 15, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Guido, Z.; Finan, T.; Rhiney, K.; Madajewicz, M.; Rountree, V.; Johnson, E.; McCook, G. The stresses and dynamics of smallholder coffee systems in Jamaica’s Blue Mountains: a case for the potential role of climate services. Climatic Change 2018, 147, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A. Economic costs of climate change and climate finance with a focus on Africa. Journal of African Economies 2014, 23, ii50–ii82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.S.-Y.; Nigatu, L.; Mekonnen, E. Tree Species Diversity in Smallholder Coffee Farms of Bedeno District, Eastern Hararghe Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. European Journal of Biophysics 2021, 9, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Mieno, T.; Brozović, N. Satellite-based monitoring of irrigation water use: Assessing measurement errors and their implications for agricultural water management policy. Water Resources Research 2020, 56, e2020WR028378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.J.; Hayashi, M.; Batelaan, O. Ecohydrology and Its Relation to Integrated Groundwater Management. In Integrated Groundwater Management, Springer: 2016; pp. 297-312.

- Mekonnen, Z.; Sintayehu, G.; Hibu, A.; Andualem, Y. Performance Evaluation of Small-Scale Irrigation Scheme: a Case Study of Golina Small-Scale Irrigation Scheme, North Wollo, Ethiopia. Water Conservation Science and Engineering 2022, 7, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, J.; Page, S.; Kennan, J. Climate change and developing country agriculture. International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development. Geneva …: 2009.

- Bannor, F. Agriculture, climate change and technical efficiency: The case of sub-Saharan Africa. University of Johannesburg, 2022.

- Noszczyk, T.; Cegielska, K.; Rogatka, K.; Starczewski, T. Exploring green areas in Polish cities in context of anthropogenic land use changes. The Anthropocene Review 2022, 20530196221112137.

- World Bank. Total Estimated Population of Major Towns. 202.

- White, S.; Robinson, J.; Cordell, D.; Jha, M.; Milne, G. Urban water demand forecasting and demand management: Research needs review and recommendations. 2003.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).