Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

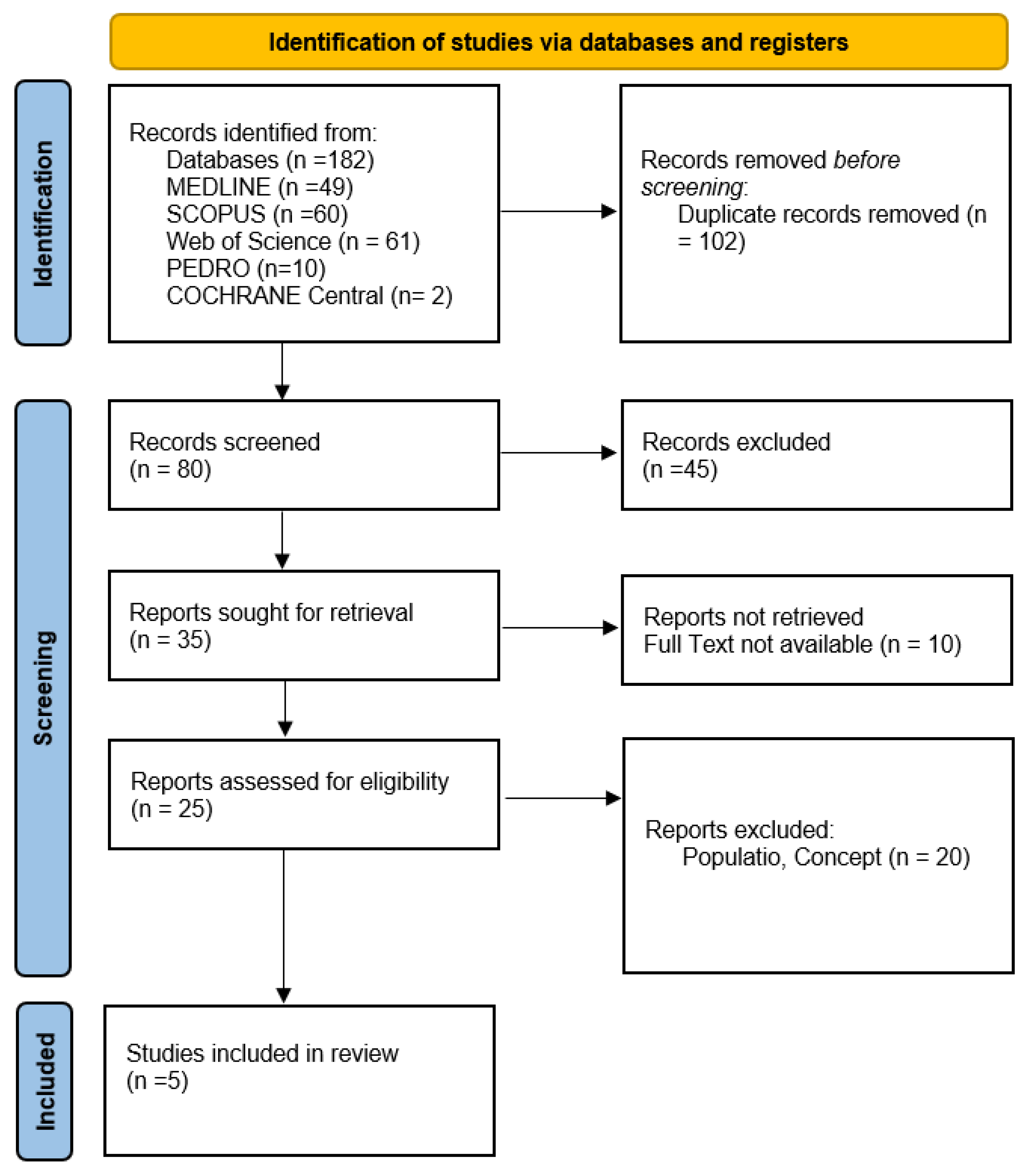

Background: The Apple Watch is increasingly used in rehabilitation to monitor physical activity, cardiovascular health, and other physiological parameters. This review evaluates its effectiveness and accuracy in various rehabilitation settings, examining its potential to enhance patient adherence and clinical outcomes. Methods: A comprehensive search was conducted across databases including MEDLINE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, PEDro, and Web of Science, alongside grey literature. Studies were included based on the PCC criteria (Population, Concept, Context), focusing on the use of the Apple Watch in rehabilitation programs. Bias risk was assessed using RoB 2 for RCTs and ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies. Results: Five studies were reviewed. The Apple Watch showed po-tential in improving physical activity levels and functional outcomes, particularly when combined with behavioral interventions. It demonstrated effectiveness in detecting atrial fibrillation in large-scale screening but presented variability in heart rate and energy expenditure accuracy, es-pecially during high-intensity activities. The studies highlighted that integrating cognitive support with the device enhances adherence and health outcomes. However, limitations in measurement accuracy and the need for hybrid monitoring approaches were noted. Conlusions: The Apple Watch is a valuable tool in rehabilitation when used alongside behavioral support and validated clinical methods. Its effectiveness is enhanced when integrated into a multidisciplinary approach, but its limitations in accuracy necessitate further calibration and hybrid use with traditional tools. Future research should focus on long-term impacts and algorithm improvements to optimize its clinical utility in diverse rehabilitation contexts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- 1.

- Population

- ●

- Description: The population considered in this review includes individuals undergoing rehabilitation programs, such as:

- ○

- Patients recovering from cardiovascular events (e.g., myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery) participating in cardiac rehabilitation.

- ○

- Individuals with musculoskeletal conditions, including those recovering from orthopedic surgeries (e.g., joint replacement, tendon repairs) or managing chronic conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis).

- ○

- Patients with neurological conditions undergoing rehabilitation for stroke recovery, multiple sclerosis, or other neurological impairments.

- ○

- Older adults or individuals with mobility limitations participating in programs aimed at improving balance, strength, and overall physical activity levels to reduce the risk of falls or frailty.

- ●

- Age Range: The studies should include adults aged 18 years and older. Studies focusing specifically on pediatric populations are excluded due to the differences in rehabilitation protocols and physiological monitoring needs in children.

- ●

- Health Status: Both chronic and post-acute conditions are included, as long as the rehabilitation involves structured physical activity or exercise monitoring.

- 2.

- Concept

- ●

- Main Focus: The primary concept of this review is the use of the Apple Watch as a wearable technology to monitor and support rehabilitation activities. The studies must focus on the following aspects:

- ○

- Monitoring Capabilities: Assessment of the Apple Watch’s accuracy in tracking physiological parameters such as heart rate, energy expenditure, ECG, and physical activity (e.g., step count, exercise duration).

- ○

- Behavioral Support and Adherence: Evaluation of how the Apple Watch, through its interactive features (e.g., notifications, activity reminders, goal setting), influences patient adherence to rehabilitation protocols and promotes physical activity.

- ○

- Clinical Outcomes: Examination of the impact of the Apple Watch on clinical outcomes, such as improvement in cardiovascular fitness, recovery of functional mobility, reduction in pain levels, and enhancement of overall quality of life.

- ●

- Additional Considerations: Studies exploring the integration of the Apple Watch within broader rehabilitation frameworks (e.g., tele-rehabilitation, remote patient monitoring programs) are also considered, as they provide insight into its applicability and scalability in clinical settings.

- 3.

- Context

- ●

- Rehabilitation Settings: The context includes various rehabilitation environments where the Apple Watch is utilized, such as:

- ○

- Clinical Rehabilitation Centers: Studies conducted in hospitals, rehabilitation clinics, or outpatient centers where patients use the Apple Watch as part of a supervised program.

- ○

- Home-based Rehabilitation: Studies focusing on remote or unsupervised rehabilitation programs where patients use the Apple Watch independently or with periodic telehealth support.

- ○

- Community Programs: Programs offered through community health centers or fitness facilities aimed at supporting rehabilitation and physical activity among individuals with chronic conditions or post-surgical recovery needs.

- ●

- Geographical Context: The review includes studies from diverse geographical locations to provide a global perspective on the use and effectiveness of the Apple Watch in different healthcare systems.

- ●

- Time Frame: The review considers studies published in the last decade, given the rapid evolution of wearable technology and the specific updates in the capabilities of recent Apple Watch models.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Physical Activity and Functional Capacity

- ●

- Jeganathan et al., 2022[6]:

- ○

- The intervention using the Apple Watch 4, which included a Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention (JITAI) system, showed a significant improvement in participants' functional capacity as measured by the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Participants in the intervention group recorded an average increase of 54 meters compared to baseline, while the control group showed minimal change. Additionally, the daily step count increased by an average of 32% in the intervention group, suggesting improved adherence to rehabilitation programs.

- ○

- Implications: These results indicate that the use of the Apple Watch as an adaptive monitoring tool can significantly enhance physical activity levels and functional capacity in patients with moderate-risk cardiovascular conditions.

3.2. Arrhythmia Monitoring and Cardiac Health

- ●

- Turakhia et al., 2019[8]:

- ○

- The study evaluated the effectiveness of the Apple Watch in detecting arrhythmias, specifically atrial fibrillation (AF). Among participants who received an irregular pulse notification, 34% had confirmed AF through subsequent ambulatory ECG monitoring. Implementing such large-scale screening demonstrated potential effectiveness in uncovering previously undiagnosed AF cases, allowing for early intervention.

- ○

- Implications: This study supports the use of the Apple Watch as a non-invasive screening tool for cardiac health, suggesting that it could be integrated into cardiac rehabilitation programs to monitor patients in real-time.

3.3. Energy Expenditure Accuracy and Activity Monitoring

- ●

- Sun et al., 2023[2]:

- ○

- The Apple Watch 6 was tested for its accuracy in measuring energy expenditure compared to direct calorimetric analysis during treadmill and ground running exercises. The results showed an average discrepancy of 20% compared to the reference values, with higher errors observed during high-intensity activities. Compared to the benchmark device (Polar A370), the Apple Watch tended to overestimate energy expenditure.

- ○

- Implications: While the Apple Watch offers accessible, real-time monitoring, the discrepancy in data suggests the need for further calibration or algorithmic improvements to ensure more accurate measurements, which is crucial in rehabilitation settings where energy expenditure accuracy is vital for exercise prescription.

3.4. Perceived Activity Adequacy and Behavioral Outcomes

- ●

- Zahrt et al., 2023[4]:

- ○

- Participants who received accurate physical activity feedback via the Apple Watch reported improved perception of their activity as adequate, along with improvements in mental health metrics such as reduced anxiety (assessed using PROMIS-29). The group that received accurate feedback combined with a meta-mindset intervention showed further enhancements, not only in activity perception but also in dietary habits and overall behavior compared to the accurate feedback group alone.

- ○

- Implications: These results indicate that the Apple Watch, when integrated with targeted cognitive interventions, can positively influence perception and adherence to physical activity, with beneficial effects on behavioral and psychological health outcomes for patients in rehabilitation.

3.5. Heart Rate Monitoring Accuracy

- ●

- Gillinov et al., 2017[9]:

- ○

- The study assessed the accuracy of the Apple Watch during various aerobic activities (treadmill, cycling, and elliptical) by comparing it to ECG as the gold standard. The Apple Watch showed high accuracy during treadmill exercise (concordance correlation coefficient rc = 0.92), but its accuracy was variable during elliptical use, especially when using arm levers.

- ○

- Implications: These findings highlight that while the Apple Watch can be reliable for heart rate monitoring in certain exercise types, caution is necessary in contexts where accuracy is critical, such as during the early stages of cardiac rehabilitation programs.

| Study | Design | Risk of Bias Tool | Domains Assessed | Overall Risk of Bias |

| Jeganathan et al., 2022[6] | Prospective, Randomized-Controlled Trial (RCT) | RoB 2 | - Randomization process | Moderate (Risk in randomization process due to lack of concealment) |

| - Deviations from intended interventions | ||||

| - Measurement of outcomes | ||||

| - Incomplete outcome data | ||||

| - Selection of the reported result | ||||

| Turakhia et al., 2019[8] | Prospective, Single-Arm Pragmatic Study | ROBINS-I | - Confounding | High (Significant confounding and selection bias) |

| - Participant selection | ||||

| - Intervention classification | ||||

| - Measurement of outcomes | ||||

| - Missing data | ||||

| - Selection of the reported result | ||||

| Sun et al., 2023[2] | Randomized Cross-Over Trial | RoB 2 (Crossover) | - Randomization sequence | Low (Proper randomization and washout period) |

| - Carryover effect | ||||

| - Measurement of outcomes | ||||

| - Incomplete data management | ||||

| Zahrt et al., 2023[4] | Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Trial | RoB 2 | - Randomization process | Moderate (Risk in outcome measurement due to lack of blinding) |

| - Deviations from intended interventions | ||||

| - Measurement of outcomes | ||||

| - Incomplete outcome data | ||||

| - Selection of the reported result | ||||

| Gillinov et al., 2017[9] | Prospective Study | ROBINS-I | - Confounding | Moderate (Confounding and measurement bias present) |

| - Participant selection | ||||

| - Intervention classification | ||||

| - Measurement of outcomes | ||||

| - Missing data | ||||

| - Selection of the reported result |

- Jeganathan et al., 2022[6]: The randomization process presented some issues, specifically with allocation concealment, which may have led to a moderate risk of bias. However, outcome measurements and adherence to protocol were consistent.

- Turakhia et al., 2019[8]: Being a single-arm study, the primary risk was confounding and participant selection bias. The absence of a control group and potential unmeasured variables contributed to a high overall risk of bias.

- Sun et al., 2023[2]: The crossover design was well-implemented, with proper randomization and washout periods to minimize carryover effects. Thus, it was rated as having a low risk of bias.

- Zahrt et al., 2023[4]: While randomization was performed, the outcome measurement lacked blinding, introducing moderate bias in the results.

- Gillinov et al., 2017[9]: Confounding factors and measurement biases, particularly in how interventions were classified and outcomes measured, led to a moderate risk of bias.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Activity and Functional Outcomes

4.2. Cardiovascular Monitoring and Health Outcomes

4.3. Accuracy in Physiological Monitoring

4.4. Implications for Rehabilitation Programs

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

4.6. Clinical Practice Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Declaration of Patient Consent

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Jr, G.; J, S.; K, G.; R, S.; Vse, J.; E, L.; T, B.; B, M.; S, K.; V, T.; et al. Text Messages to Promote Physical Activity in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Micro-Randomized Trial of a Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X, S.; Z, W.; X, F.; C, Z.; F, W.; H, H. Validity of Apple Watch 6 and Polar A370 for Monitoring Energy Expenditure While Resting or Performing Light to Vigorous Physical Activity. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Se, E.; Dj, T.; D, G.; Mm, S.; Dm, R.; Sm, N.; M, R.; A, H.; M, M.; A, G.; et al. A Non-Pharmacological Multi-Modal Therapy to Improve Sleep and Cognition and Reduce Mild Cognitive Impairment Risk: Design and Methodology of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Contemporary clinical trials 2023, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrt, O.H.; Evans, K.; Murnane, E.; Santoro, E.; Baiocchi, M.; Landay, J.; Delp, S.; Crum, A. Effects of Wearable Fitness Trackers and Activity Adequacy Mindsets on Affect, Behavior, and Health: Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e40529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.M.; Steinhubl, S.; Lakkireddy, D.; Turakhia, M.P.; Passman, R.; Jones, W.S.; Bunch, T.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Peterson, E.D.; Ruskin, J.; et al. Does Early Detection of Atrial Fibrillation Reduce the Risk of Thromboembolic Events? Rationale and Design of the Heartline Study. Am Heart J 2023, 259, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, V.S.; Golbus, J.R.; Gupta, K.; Luff, E.; Dempsey, W.; Boyden, T.; Rubenfire, M.; Mukherjee, B.; Klasnja, P.; Kheterpal, S.; et al. Virtual AppLication-Supported Environment To INcrease Exercise (VALENTINE) during Cardiac Rehabilitation Study: Rationale and Design. Am Heart J 2022, 248, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMunion, S.R.; Blythe, A.L.; Hibbing, P.R.; Kaplan, A.S.; Clendenin, B.J.; Crouter, S.E. Use of Consumer Monitors for Estimating Energy Expenditure in Youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2020, 45, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turakhia, M.P.; Desai, M.; Hedlin, H.; Rajmane, A.; Talati, N.; Ferris, T.; Desai, S.; Nag, D.; Patel, M.; Kowey, P.; et al. Rationale and Design of a Large-Scale, App-Based Study to Identify Cardiac Arrhythmias Using a Smartwatch: The Apple Heart Study. Am Heart J 2019, 207, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillinov, S.; Etiwy, M.; Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, A.M.; Houghtaling, P.; Javadikasgari, H.; Desai, M.Y. Variable Accuracy of Wearable Heart Rate Monitors during Aerobic Exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017, 49, 1697–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Burns, R.; Ma, C.; Curl, A.; Hudziak, J.; Copeland, W.E. Tracking Well-Being: A Comprehensive Analysis of Physical Activity and Mental Health in College Students Across COVID-19 Phases Using Ecological Momentary Assessment. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2024, 34, e14738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, B.; Lambe, R.; Baldwin, M.; Acheson, T.; Doherty, C. The Validity of Apple Watch Series 9 and Ultra 2 for Serial Measurements of Heart Rate Variability and Resting Heart Rate. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, A.; Leroy, M.; Jux, C.; Rupp, S.; Backhoff, D. Oxygen Saturation Measurement in Cyanotic Heart Disease with the Apple Watch. Cardiol Young 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. Exploring the Potential of iPhone Applications in Podiatry: A Comprehensive Review. Egyptian Rheumatology and Rehabilitation 2024, 51, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, R.; Jain, S.; Thakre, A.; Thotamgari, S.R.; Raina, S.; Brar, V.; Sengupta, P.; Agrawal, P. Smart Watch Applications in Atrial Fibrillation Detection: Current State and Future Directions. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Park, J.; Shapiro, I.; Fisher-Colbrie, T.; Baird, D.D.; Suharwardy, S.; Zhang, S.; Jukic, A.M.Z.; Curry, C.L. Trends in Sensor-Based Health Metrics during and after Pregnancy: Descriptive Data from the Apple Women’s Health Study. AJOG Glob Rep 2024, 4, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L.; Kangarloo, T.; Gong, Y.; Khachadourian, V.; Tracey, B.; Volfson, D.; Latzman, R.D.; Cosman, J.; Edgerton, J.; Anderson, D.; et al. Using a Smartwatch and Smartphone to Assess Early Parkinson’s Disease in the WATCH-PD Study over 12 Months. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, M.-K. Sixty Seconds on... Apple Watch. BMJ 2024, 385, q1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreki, A.; Sado, M.; Mitsukura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Kubota, A.; Kanamori, Y.; Uchibori, M.; Usune, S.; Ninomiya, A.; Shirahama, R.; et al. The Association between Salivary IL-6 and Poor Sleep Quality Assessed Using Apple Watches in Stressed Workers in Japan. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 22620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorina, L.; Chemaly, P.; Cellier, J.; Said, M.A.; Coquard, C.; Younsi, S.; Salerno, F.; Horvilleur, J.; Lacotte, J.; Manenti, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Electrocardiogram Analysis Improves Atrial Arrhythmia Detection from a Smartwatch Electrocardiogram. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2024, 5, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami Rad, A.; Kirsch, M.; Li, Q.; Xue, J.; Sameni, R.; Albert, D.; Clifford, G.D. A Crowdsourced AI Framework for Atrial Fibrillation Detection in Apple Watch and Kardia Mobile ECGs. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farì, G.; Mancini, R.; Dell’Anna, L.; Ricci, V.; Della Tommasa, S.; Bianchi, F.P.; Ladisa, I.; De Serio, C.; Fiore, S.; Donati, D.; et al. Medial or Lateral, That Is the Question: A Retrospective Study to Compare Two Injection Techniques in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis Pain with Hyaluronic Acid. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V.; Mezian, K.; Cocco, G.; Donati, D.; Naňka, O.; Farì, G.; Özçakar, L. Anatomy and Ultrasound Imaging of the Tibial Collateral Ligament: A Narrative Review. Clinical Anatomy 2022, 35, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truslow, J.; Spillane, A.; Lin, H.; Cyr, K.; Ullal, A.; Arnold, E.; Huang, R.; Rhodes, L.; Block, J.; Stark, J.; et al. Understanding Activity and Physiology at Scale: The Apple Heart & Movement Study. NPJ Digit Med 2024, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.; Labanca, L.; Platano, D.; Benedetti, M.G. Assessment of Balance During a Single-Limb Stance Task in Healthy Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Percept Mot Skills 2024, 315125241277250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artese, A.L.; Winthrop, H.M.; Bohannon, L.; Lew, M.V.; Johnson, E.; MacDonald, G.; Ren, Y.; Pastva, A.M.; Hall, K.S.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; et al. A Pilot Study to Assess the Feasibility of a Remotely Monitored High-Intensity Interval Training Program Prior to Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0293171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.A.; Phillips, B.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Wilson, D.; Deal, A.M.; Bailey, C.; Meeneghan, M.; Reeve, B.B.; Basch, E.M.; Bennett, A.V.; et al. Personalized Home-Based Interval Exercise Training May Improve Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Cancer Patients Preparing to Undergo Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016, 51, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.K.; Virk, R.; Kaiser, K.; Hoffman, K.E.; Goodman, C.R.; Mitchell, M.; Shaitelman, S.; Schlembach, P.; Reed, V.; Wu, C.-F.; et al. Automated, Real-Time Integration of Biometric Data From Wearable Devices With Electronic Medical Records: A Feasibility Study. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2024, 8, e2400040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserman, P.; Yum, S.; Göbel, S.; Reif, A.; Matura, S. Assessing the Accuracy of Smartwatch-Based Estimation of Maximum Oxygen Uptake Using the Apple Watch Series 7: Validation Study. JMIR Biomed Eng 2024, 9, e59459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Kantartjis, M.; Severson, J.; Dorsey, R.; Adams, J.L.; Kangarloo, T.; Kostrzebski, M.A.; Best, A.; Merickel, M.; Amato, D.; et al. Wearable Sensor-Based Assessments for Remotely Screening Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafyllidis, A.; Kondylakis, H.; Katehakis, D.; Kouroubali, A.; Alexiadis, A.; Segkouli, S.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D. Smartwatch Interventions in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int J Med Inform 2024, 190, 105560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R. Exploring the Efficacy of Plantar Reflexology as a Complementary Approach for Headache Management: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 2024, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, D.; Park, E.J. Nonlinear Heart Rate Variability Analysis for Sleep Stage Classification Using Integration of Ballistocardiogram and Apple Watch. Nat Sci Sleep 2024, 16, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spartano, N.L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chernofsky, A.; Lin, H.; Trinquart, L.; Borrelli, B.; Pathiravasan, C.H.; Kheterpal, V.; Nowak, C.; et al. Agreement Between Apple Watch and Actical Step Counts in a Community Setting: Cross-Sectional Investigation From the Framingham Heart Study. JMIR Biomed Eng 2024, 9, e54631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooner, P.; Baskaran, S.; Gibbs, V.; Wein, S.; Dimentberg, R.; Albers, A. Commercially Available Activity Monitors Such as the Fitbit Charge and Apple Watch Show Poor Validity in Patients with Gait Aids after Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res 2024, 19, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccolari, P.; Tedeschi, R.; Platano, D.; Donati, D. “Review of Contemporary Non-Surgical Management Techniques for Metacarpal Fractures: Anatomy and Rehabilitation Strategies”. Orthoplastic Surgery 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, JBI - Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar-google-com.ezproxy.unibo.it/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=2020&author=MDJ+Peters&author=C+Godfrey&author=P+McInerney&author=Z+Munn&author=AC+Tricco&author=H+Khalil&title=Joanna+Briggs+Institute+Reviewer%27s+Manual%2C+JBI (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmovitsky, P.E.; Alencar, P.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Cowan, D.; Morita, P.P. Application of a Mobile Health Data Platform for Public Health Surveillance: A Case Study in Stress Monitoring and Prediction. Digit Health 2024, 10, 20552076241249931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, R.H.; Foroutan, F.; De Luca, E.; Albertini, L.; Rac, V.E.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Hershman, S.G.; Duero Posada, J.G.; Ross, H.J.; Moayedi, Y. Feasibility of Single-Lead Apple Watch Electrocardiogram in Atrial Fibrillation Detection Among Heart Failure Patients. JACC Adv 2024, 3, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, N.; Glinskii, V.; Anderson, R.; Del Rosario, P.; Hedlin, H.; Lee, J.; Hess, J.; Van Wormer, S.; Lopez, A.; Hershman, S.G.; et al. Safety, Feasibility, and Utility of Digital Mobile Six-Minute Walk Testing in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: The DynAMITE Study. medRxiv 2024, 2024.08.08.24311687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunchay, S.; Linden-Carmichael, A.N.; Abdullah, S. Using a Smartwatch App to Understand Young Adult Substance Use: Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. JMIR Hum Factors 2024, 11, e50795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, M.L.; Vergeer, M.; Plasqui, G.; Baumgart, J.K. Accuracy of the Apple Watch Series 4 and Fitbit Versa for Assessing Energy Expenditure and Heart Rate of Wheelchair Users During Treadmill Wheelchair Propulsion: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form Res 2024, 8, e52312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminorroaya, A.; Dhingra, L.S.; Camargos, A.P.; Shankar, S.V.; Khunte, A.; Sangha, V.; Sen, S.; McNamara, R.L.; Haynes, N.; Oikonomou, E.K.; et al. Study Protocol for the Artificial Intelligence-Driven Evaluation of Structural Heart Diseases Using Wearable Electrocardiogram (ID-SHD). medRxiv 2024, 2024.03.18.24304477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.W.; Finnegan, O.L.; Tindall, N.; Nelakuditi, S.; Brown, D.E.; Pate, R.R.; Welk, G.J.; de Zambotti, M.; Ghosal, R.; Wang, Y.; et al. Comparison of Raw Accelerometry Data from ActiGraph, Apple Watch, Garmin, and Fitbit Using a Mechanical Shaker Table. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0286898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khushhal, A.A.; Mohamed, A.A.; Elsayed, M.E. Accuracy of Apple Watch to Measure Cardiovascular Indices in Patients with Chronic Diseases: A Cross Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2024, 17, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, M.; Atiq, I.; Younus, S. Effectiveness of the Apple Watch as a Mental Health Tracker. J Glob Health 2024, 14, 03010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstiens, S.; Gleason, L.J.; Huisingh-Scheetz, M.; Landi, A.J.; Rubin, D.; Ferguson, M.K.; Quinn, M.T.; Holl, J.L.; Madariaga, M.L.L. Barriers and Facilitators to Smartwatch-Based Prehabilitation Participation among Frail Surgery Patients: A Qualitative Study. BMC Geriatr 2024, 24, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, S.; Alkalthem, D.; Alenazi, S.; Alsowinea, M.; Alanazi, N.; Al Fagih, A. The Reliability of the Apple Watch’s Electrocardiogram. Cureus 2023, 15, e49786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedivash, A.; Chubb, H.; Giacone, H.; Boramanand, N.K.; Dubin, A.M.; Trela, A.; Lencioni, E.; Motonaga, K.S.; Goodyer, W.; Navarre, B.; et al. Utility of Smart Watches for Identifying Arrhythmias in Children. Commun Med (Lond) 2023, 3, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Study Design | Country | Sample Size and Participant Characteristics | Intervention and Control | Outcomes and Follow-Up |

| Jeganathan et al., 2022[6] | Prospective, Randomized-Controlled Trial | USA | 150 participants with cardiovascular disease (aged 45-70), classified as low to moderate risk based on the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation criteria. | Intervention: Participants received an Apple Watch 4 with a Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention (JITAI) for physical activity monitoring and personalized notifications. Control: Usual care with no additional device. | Primary outcomes: 6-minute walk test distance and daily step count. Follow-up: 6 months. Significant improvement in physical activity levels and functional capacity in the intervention group. |

| Turakhia et al., 2019[8] | Prospective, Single-Arm Pragmatic Study | USA | 419,093 participants aged ≥22, all users of the Apple Watch Series 1 or later with no prior history of atrial fibrillation (AF). | All participants received the Apple Watch irregular pulse notification algorithm. Those notified of an irregular pulse received ambulatory ECG patch monitoring as follow-up. | Primary outcome: Detection rate of AF based on ECG confirmation following a notification. Follow-up: 3 months. The study demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale AF screening using wearables. |

| Sun et al., 2023[2] | Randomized Cross-Over Trial | China | 11 male adults (aged 22.5 ± 1.8 years) with regular physical activity habits (3+ sessions per week) and a BMI ≤ 25. | Intervention: Participants wore both the Apple Watch 6 and Polar A370 while performing treadmill and ground running exercises. Control: Calorimetric analysis as a reference. | Outcomes: Energy expenditure accuracy compared to calorimetric measurements during rest and various physical activity levels. Follow-up: Immediate comparison; higher mean error observed for Apple Watch. |

| Zahrt et al., 2023[4] | Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Trial | USA | 162 adults aged 25-55 recruited through online platforms, divided into four groups based on the type of step count feedback provided via Apple Watch. | Groups: Accurate step count; 40% deflated; 40% inflated; accurate step count + meta-mindset intervention. Control: Accurate step count only. | Outcomes: Perception of physical activity adequacy, dietary habits, and mental health. Follow-up: 5 weeks. Meta-mindset intervention group showed improved self-perception and physical health metrics. |

| Gillinov et al., 2017[9] | Prospective Study | USA | 50 healthy adult volunteers (aged 38 ± 12 years, 54% female) with no known cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, capable of performing aerobic exercise. | Intervention: Participants wore Apple Watch, Fitbit Blaze, Garmin, and Polar HR monitors during various exercises. Control: ECG monitoring as the gold standard. | Outcomes: Accuracy of heart rate measurement compared to ECG during treadmill, cycling, and elliptical exercises. Follow-up: Immediate during exercise. Apple Watch showed variable accuracy across activities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).