1. Introduction

Significant progress has been made in the field of Peritoneal Dialysis (PD), most notably with the advent of Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) in 1977 [

1]. This innovation provided a simpler, cost-effective, and patient-centric approach to dialysis, allowing patients to manage their treatment at home, which significantly increased its acceptance and utilization [

2]. Despite the success of CAPD, there is an ongoing need for improvements in the technology used for CKD management. Recent research and development of PD machines has focused on creating a low-cost APD prototype that meets international standards. This system is designed to automatically control the infusion and drainage of dialysate with high precision and minimal error [

3]. Moreover, the prototype could adjust the electrical 12V DC pumps’ speeds to align with desired flow rates, while the PWM generators with Arduino ATmega2560 Mega board maintains fluctuations within the acceptable range. Additionally, a thermal heater is incorporated to mitigate the risk of peritonitis by regulating the inflow dialysate’s temperature to a permissible range as to mirror the actual human body temperature [

4]. The reviewed literature affirms that an APD machine can effectively deliver the necessary parameters for successful therapy. Hence, the research and development of advanced APD devices aims to enhance dialysis technology as to improve patient outcomes in CKD management.

Furthermore, CKD is a significant public health challenge in South Africa, where access to effective dialysis treatment is severely limited. The traditional dialysis methods often require patients to visit healthcare facilities multiple times a week, which can be logistically challenging and burdensome, particularly for patients in rural areas. The scarcity of the portable and compact APD systems restricts patients’ mobility and quality of life, leading to increased morbidity and mortality rates among South African population [

4]. Moreover, the existing dialysis systems are often unmanageable (i.e. demand high costs) and require patients to adhere to strict schedules, limiting their mobility and independence [

5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a lightweight, compact device that integrates advanced sorbent technology to enhance treatment accessibility in South Africa.

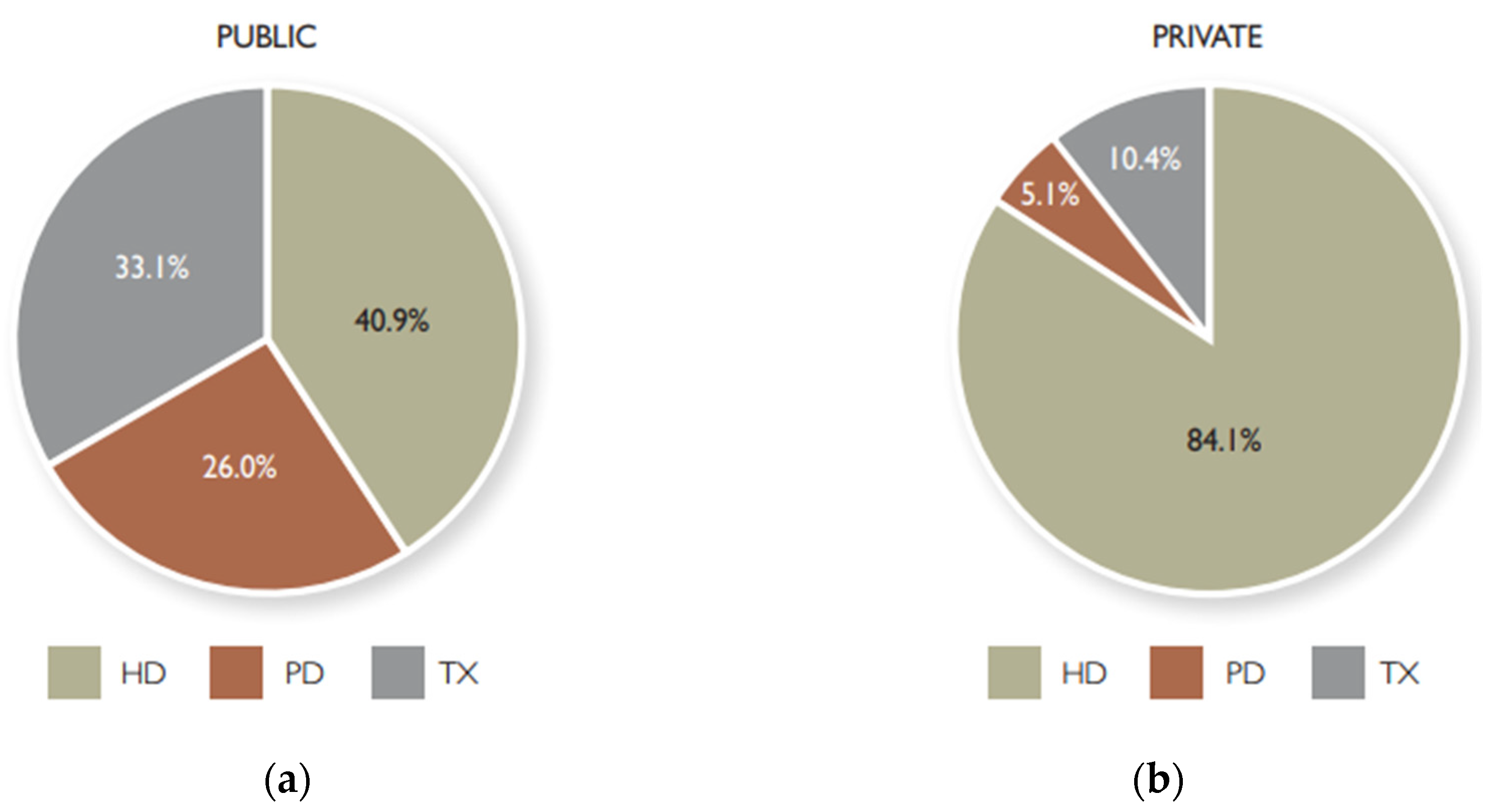

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of modalities of renal replacement in South Africa; and

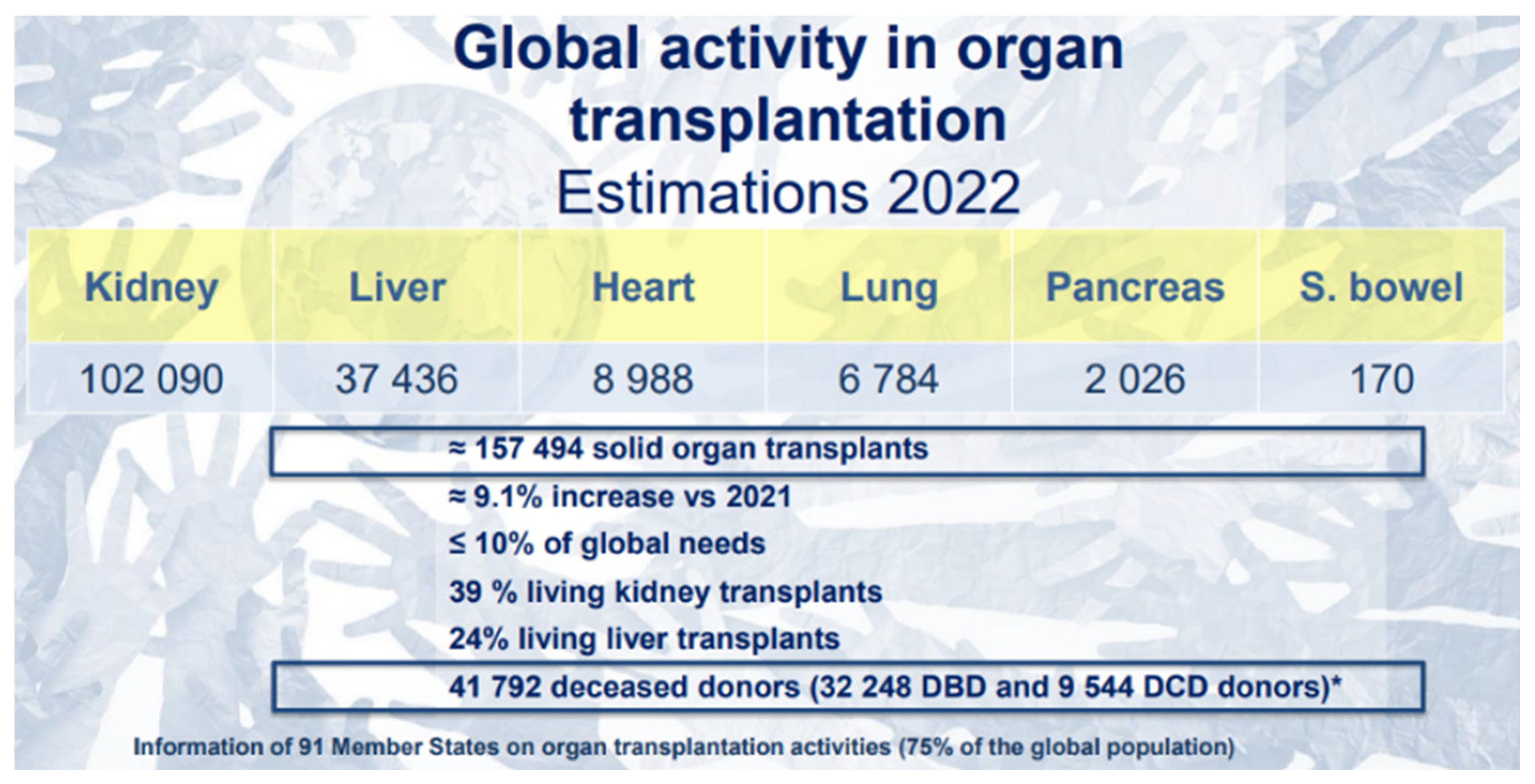

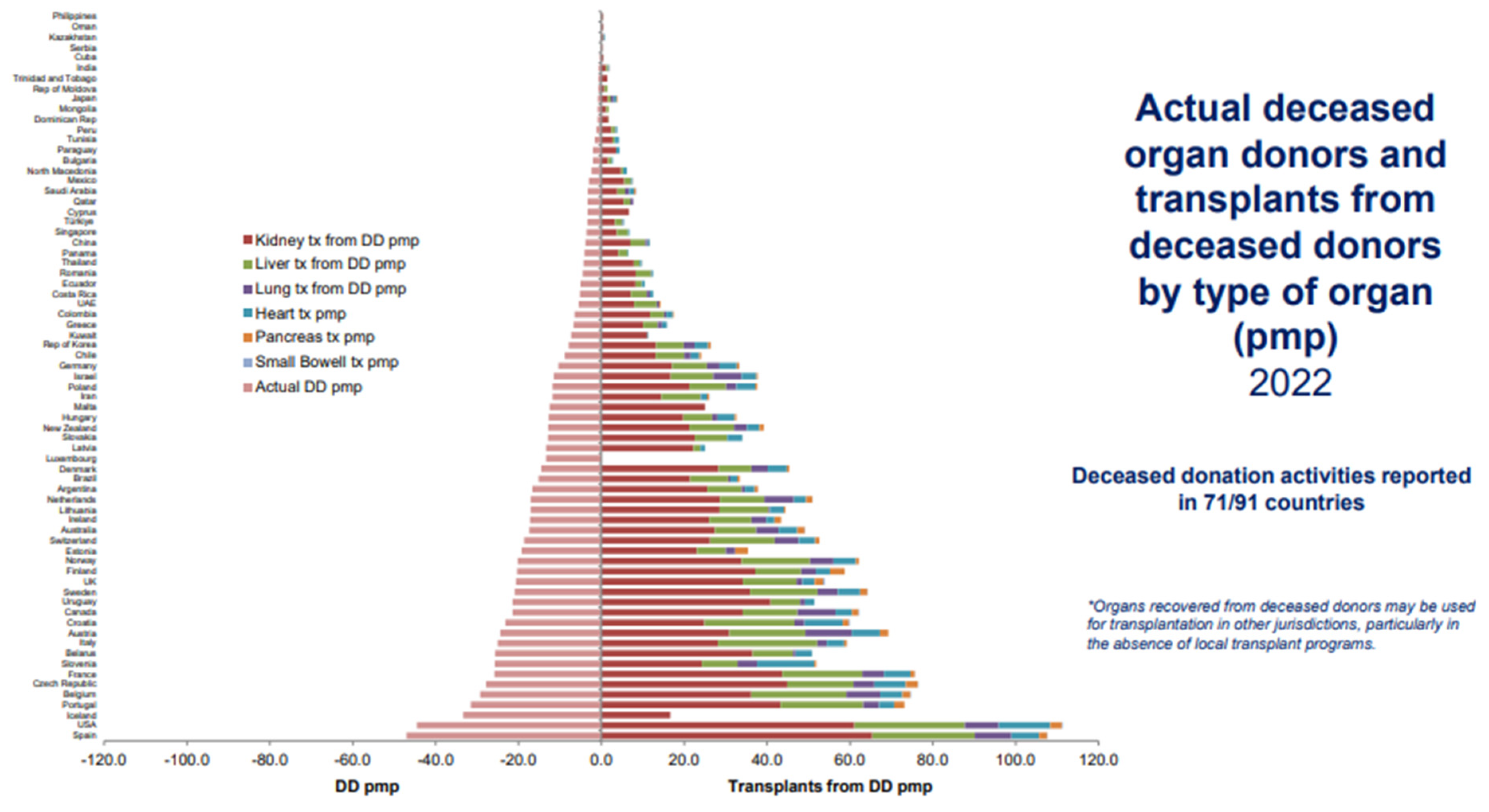

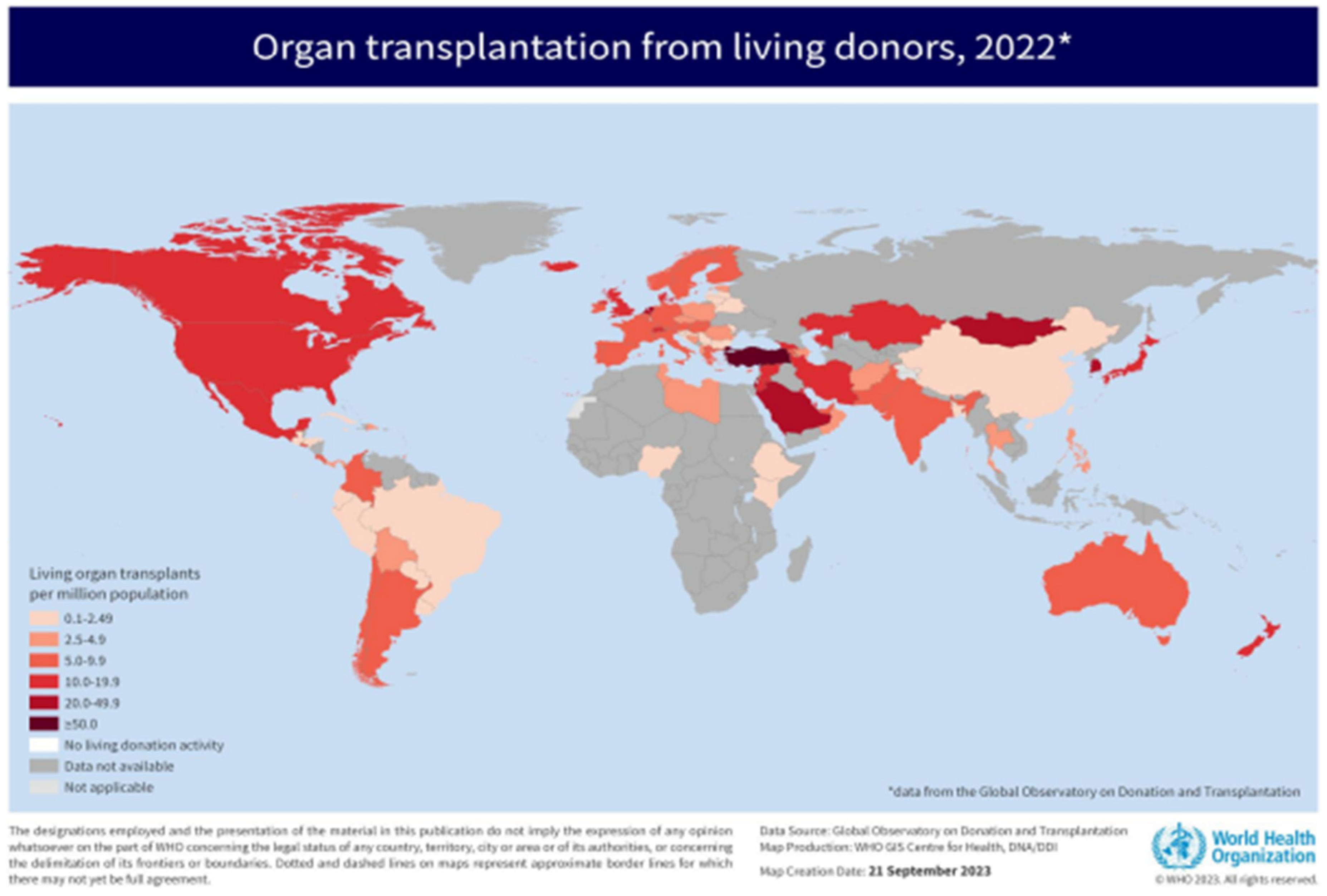

Figure 2 to 4 depicts insightful findings about kidney transplantation from Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT).

Figure 1.

The South African Distribution of Modalities of Renal Replacement [

5]. (a) Pie chart depicting adoption of renal replacement modalities in the public sector; (b) Pie chart depicting adoption of renal replacement modalities in the public sector. (Available: Link, accessed 07/11/2024).

Figure 1.

The South African Distribution of Modalities of Renal Replacement [

5]. (a) Pie chart depicting adoption of renal replacement modalities in the public sector; (b) Pie chart depicting adoption of renal replacement modalities in the public sector. (Available: Link, accessed 07/11/2024).

Figure 2.

Estimations in 2022 of Global Activity in Organ Transplantation [

6].

Figure 2.

Estimations in 2022 of Global Activity in Organ Transplantation [

6].

Figure 3.

Actual Deceased Organ Donors and Transplants from Deceased Donors by Type of Organ (Available: Link, accessed 07/11/2024) [

6].

Figure 3.

Actual Deceased Organ Donors and Transplants from Deceased Donors by Type of Organ (Available: Link, accessed 07/11/2024) [

6].

Figure 4.

Living Donors’ Organ Transplantation (Available:

Link) [

6].

Figure 4.

Living Donors’ Organ Transplantation (Available:

Link) [

6].

From the four figures, it is evident that, in the South African context, hemodialysis (HD) is a widely adopted mitigation to CKD, followed by kidney transplant (TX) and lastly, peritoneal dialysis (PD). On the global scale, kidney transplantation is a widely encountered therapy over other organs’ transplantation, and this type to renal replacement therapy is uncommonly adopted in Africa. That is, there are two treatments for patients with CKD: kidney transplant or dialysis. Dialysis has two variants, hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD). The objective of both procedures is the same which is eliminating the uremic toxins with different molecular weights in the blood [

5]. Despite low adoption of PD systems, they have several benefits over other modalities such as needle-free treatment and low-cost treatment. Moreover, a machine for APD administers and prepares the optimal conditions for the dialysate to reach the peritoneal cavity. Each therapy performs three work cycles: infusion, permanence, and drain. The pumps transfer dialysate at 35.5 °C – 37.5 °C to the peritoneal cavity during the infusion without overfilling (i.e. a W1209 Thermistor module regulates the dialysate’s temperature, and the Arduino Mega controls the automatic switching OFF of the pump designated for infusion process when the dialysate is on longer available in the dextrose container). Then, permanence process transpires - there is an occurrence of an exchange between the blood and the dialysate solution due to the difference in osmotic concentration, diffusion of molecules takes place between the peritoneal membrane and the dialysate (i.e. dextrose solution). In the prototyping phase, the ultra-filtration process, which involves the removal of metabolic waste; the infused fluid is extracted from the peritoneal cavity of a “human being” (i.e. simulated human body) during the drainage step. This occurs after the dialysate has been allowed to dwell in the peritoneal cavity for several hours. A waiting period of approximately 4 hours between these processes is typically recommended to ensure optimal efficiency. Throughout the cycle, the volumetric precision of the available dialysate in the dextrose container, the dialysate’s temperature, the inflow and drainage flowrates, and each designated pump’s speed are monitored by the patient; and for any irregularity, the threshold alert module is set ON (e.g. 5V relay module) [

7].

In summary, the development of these portable dialysis devices has gained momentum in recent years, driven by advancements in medical technology and a growing recognition of the need for patient-centered care [

7]. These innovative systems aim to provide patients with greater autonomy and flexibility in managing their treatment. The developed machine is positioned to fill this gap by offering a compact, lightweight solution that can be easily integrated into the patients’ daily lives. Furthermore, one of the primal innovations of this device is its use of sorbent-based dialysate regeneration technology. Traditional dialysis systems require significant amounts of fresh dialysate for each treatment session, leading to environmental concerns and increased costs. However, the developed APD device would utilize sorbent materials to purify and regenerate the used dialysate, which would significantly reduce the volume of fluids needed for an effective treatment. This technology would enhance the sustainability of dialysis and minimize the logistical challenges associated with transporting large quantities of dialysate.

In addition, the sorbent dialysis systems represent a notable innovation in renal replacement therapy, particularly for patients with the end-stage renal disease [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These systems function by recirculating dialysate effluent from the dialyzer through a sorbent column, where solutes are adsorbed, ions exchanged, or catalytically converted [

8]. This process regenerates the dialysate into an ultra-pure water solution, which is then combined with an electrolyte concentrate before being returned to the dialyzer. Moreover, the primal advantage of sorbent dialysis is its exceptional water efficiency, requiring only 10–15 liters of untreated water per dialysis session, compared to the 120–150 liters needed by traditional single-pass systems. This efficiency facilitates the miniaturization and portability of dialysis machines, making them ideal for home peritoneal dialysis applications. The examples of sorbent-based systems include the REDY system (1970s), the Allient machine (2000s) and compact artificial kidneys (modern-day) [

8].

1.1. Problem Statement

CKD is a growing health concern in South Africa, where many patients face substantial obstacles to accessing effective dialysis treatment. The existing dialysis systems are often bulky, stationary, and require frequent hospital visits, which limits the patients’ mobility and their overall quality of life. The lack of portable and compact Automated Peritoneal Dialysis Systems exacerbates the situation, preventing patients from receiving timely and life-saving therapies. This project’s aim is to develop a lightweight, compact device that integrates advanced sorbent technology for improved treatment accessibility. The current absence of such systems in South Africa not only hinders treatment but also leads to poor health outcomes and diminished quality of life for patients. Therefore, South African patients with CKD face significant barriers to accessing effective dialysis treatment due to the lack of portable and compact APD Dialysis Systems. This limits their mobility and quality of life, necessitating the development of a lightweight, compact device that integrates advanced sorbent technology for improved treatment accessibility. Thus, the current lack of portable and compact APD systems in South Africa hinders the treatment of patients with CKD, leading to limited access to life-saving therapies and poor health outcomes.

2. Literature Review

Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) is a vital treatment modality for patients with CKD, allowing for the removal of waste products and excess fluid from the human body [

9]. This literature review focuses on the advancements in peritoneal dialysis machines, particularly highlighting APD systems, which have gained popularity due to their efficiency and patient-centered design [

7,

8,

9]. The overview of PD machines outline that these machines facilitate the process of dialysis by automating the infusion and drainage of dialysate, a sterile solution (i.e. dialysate) used to absorb waste products from the blood via the peritoneal membrane [

10]. These machines significantly reduce the manual effort required in traditional Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD), thereby improving the patients’ convenience and adherence to treatment regimens [

11].

Moreover, recent advancements in PD technology include the development of low-cost automated systems that leverage 3D printing techniques to create affordable and efficient dialysis machines [

10,

11]. For instance, the reviewed literature demonstrated that the design of a 3D-printed APD machine, which integrates a heating base and a peristaltic pumps for optimal performance not only enhances the accessibility of PD treatment but also reduce costs, making it feasible for patients in resource-limited settings [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The APD methods are deemed good with clinical outcomes and patients’ experience compared to traditional methods. A study involving 42 patients reported a peritonitis rate of 1 episode per 42 patient-months, indicating a lower risk of infection associated with APD [

8,

9,

10]. Moreover, patients transitioning from CAPD to APD experienced better biochemical control, with significant improvements in urea and creatinine levels, demonstrating the efficacy of APD systems in managing CKD treatments [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In addition, the integration of digital health technology into PD machines has revolutionized patient monitoring as digital platforms allow healthcare providers to remotely track treatment data, enhancing oversight and enabling timely interventions [

12,

13,

14,

15]. This feature improves patient safety and fosters a collaborative approach between patients and healthcare teams, leading to better adherence to treatment protocols. However, challenges remain in the widespread adoption of APD machines. This entails high initial costs and technical complexities that hinders accessibility. Also, training its users is crucial to ensure its effective usage. In summary, CAPD (i.e. manual fluid exchanges) and APD (i.e. cycler automated exchanges) are viable options for CKD patients requiring PD. Thus, APD provides more convenience and flexibility as patients report higher satisfaction with APD [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Economically, CAPD is cheaper than APD, but both modalities require patient training, and the choice of modality is based on the patient’s preferences, lifestyle, costs, and training needs [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

The table compares CAPD and APD, highlighting APD’s advantages in convenience, adherence, infection risk, biochemical control, and patient satisfaction, despite higher initial costs and training needs, making it a preferable option for managing CKD.

Table 1.

Comparison and Advantages of PD Systems.

Table 1.

Comparison and Advantages of PD Systems.

| Characteristic |

Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) |

Automated Peritoneal Dialysis (APD) |

| Dialysis Method |

Manual fluid exchanges throughout a day |

Automated exchanges using a cycler at night |

| Convenience |

Requires frequent manual exchanges |

Reduces manual effort, freeing up daytime |

| Adherence |

Lower adherence due to manual effort |

Higher adherence due to automated process |

| Infection Risk |

Higher risk of peritonitis |

Lower risk of peritonitis

(1 episode per 42 patient-months) |

Biochemical

Control

|

Less effective in urea and creatinine control |

Significant improvements in urea and creatinine levels |

Ultrafiltration

Efficiency

|

Lower Ultrafiltration efficiency |

Higher Ultrafiltration efficiency, especially in fast transporters |

Prescription

Flexibility

|

Limited flexibility |

Tailored personalization of fill volume, dwell time, and glucose concentration |

Remote

Monitoring

|

No remote monitoring |

Real-time remote monitoring and data collection |

| Cost |

Economically cheaper |

Higher initial costs, but potentially cost-effective in long term |

| Training Needs |

Requires patient training |

Requires patient and caregiver training |

Patient

Satisfaction

|

Lower patient satisfaction |

Higher patient satisfaction and lifestyle flexibility |

Clinical

Outcomes

|

Less effective in managing CKD |

Better clinical outcomes and patient experience |

3. Project Description

3.1. User-Friendly Interface

This project aims to develop and integrate a user-friendly interface for the miniature digital APD machine, utilizing an LCD 16x02 screen and two OLED 128x64 displays. The primary objective is to enhance the patient’s experience by providing graphical, real-time health metrics and the machine status updates – infusion, permanence, or drain. The interface is designed to display critical patient health metrics, including the heart rate (i.e. measuring the heart’s beats per minute - bpm), which is crucial for monitoring the patient’s cardio health condition during the dialysis session. Moreover, the developed system prompts commands to the user to lessen the machine’s user control difficulties. This real-time feedback will help patients understand the treatment progress and ensure that the dialysis is proceeding as prescribed.

The LCD 16x02 screen displays phases of the dialysis session while the OLED 128x64 screen offers high-resolution graphics and animations to guide the user through the setup and treatment process, ensuring ease of use and minimizing the risk of user errors. The interface will be programmed to be intuitive, with vivid graphics and concise messaging, and will include features such as automatic alerts for any deviations from the prescribed treatment protocol by employing an Arduino Mega micro-controller. This project leverages advanced display technologies to improve the safety, efficiency, and patient comfort associated with APD, aligning with the evolving standards of home dialysis care.

Furthermore, the display screens employed in this system, each is equipped with an I2C module, to facilitate simplified connection and programming on the developed system. The I2C modules, typically utilizing the PCF8574 or PCF8574AT chip, enable communication between the displays and the microcontroller (e.g. Arduino Mega) using only two wires (SDA and SCL), thereby conserving I/O pins. The LCD 16x02 screen, with its 16x2 character matrix, is ideal for displaying text-based information, while the OLED 128x64 display, with their higher resolution, can show more complex graphics and data. By assigning unique I2C addresses to each display (e.g. 0x27 or 0x3F for LCD, and 0x3C for OLED display), the system can manage multiple screens efficiently, ensuring clear and stable output. This setup is particularly beneficial for projects requiring multi-display interfaces, such as this digital APD machine.

3.2. Dialysate Temperature Control

This project aims to integrate a W1209 thermistor module into an APD machine to precisely regulate the temperature of the dialysate solution within the clinically acceptable range of 35.5 °C – 37.5 °C. The thermistor module will be coupled with a 240V AC mini heater, functioning as a thermal bed, to maintain the optimal temperature for the dialysate solution. The system will be designed to automatically switch ON the heater when the temperature of the dialysate solution drops below the set range and switch it OFF once the desired temperature is achieved. This feedback loop ensures that the solution remains at a temperature close to the human body temperature, which is crucial for effective and comfortable dialysis session.

The thermistor module will provide accurate dialysate temperature readings, and the associated control circuitry will regulate the heating element. The system will be programmed to accommodate different patient demographics, including infants, adolescents, adults, and the elderly, by adjusting the temperature settings according to specific clinical guidelines. This integration enhances the safety, efficiency, and patient comfort of APD treatments by ensuring that the dialysate solution is always at an optimal temperature, thereby reducing the risk of thermal-related complications and improving the overall efficacy of the dialysis session. The project ought to involve thorough testing and validation to ensure compliance with clinical standards and safety regulations.

Table 2.

Thermistor System Operation Parameters.

Table 2.

Thermistor System Operation Parameters.

| Parameter |

Description |

Settings |

| Temperature Range |

Clinically acceptable temperature range for dialysate solution |

35.5°C - 37.5°C |

| Heater Activation |

Temperature threshold for heater activation |

< 35.5°C |

| Heater Deactivation |

Temperature threshold for heater deactivation |

≥ 37.5°C |

| Patient Demographics |

Adjustable temperature settings for different patient groups |

Infants: 37.5°C - 38°C, Adolescents: 36.2°C - 36.7°C, Adults: 36.5°C - 37.0°C, Elderly: 36.0°C - 36.5°C |

The table outlines thermistor system parameters for dialysate solution temperature, including activation and deactivation thresholds, and adjustable temperature settings based on patient demographics such as infants, adolescents, adults, and the elderly.

Table 3.

Thermistor System Performance Metrics.

Table 3.

Thermistor System Performance Metrics.

| Metric |

Description |

Target Values |

| Temperature Accuracy |

Deviation from set temperature |

≤ ± 0.5 °C |

| Heating Time |

Time to reach desired temperature from ambient |

< 30 minutes |

| Stability |

Maintenance of temperature within set range |

≥ 95% of treatment time |

| Patient Comfort |

Reduction in thermal-related complications |

≥ 90% patient satisfaction |

| Efficiency |

Automated temperature control reducing manual intervention |

≥ 95% automation rate |

The table outlines thermistor system performance metrics, including temperature accuracy, heating time, stability, patient comfort, and automation efficiency targets.

3.3. 12V DC Pumps Control with Pulse-Width Modulation

This project involves the development of an APD machine that utilizes Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) technique to regulate the average power delivered to 12V DC pumps. The primary objective is to provide a precise and adjustable dialysate flow rate control for both the infusion and drain processes during the dialysis session. At the heart of this system are PWM generators, which are essential for controlling the average power supplied to the 12V DC pumps. Each pump is connected to a PNP Power Darlington transistor, chosen for their high current handling capability and low saturation voltage. Each transistor is properly biased with a 1 kΩ resistor at the base to ensure accurate control over the switching effect, thereby maintaining stable and efficient operation.

A key feature of this system is the incorporation of two 100 kΩ potentiometers, which allows the patient to manually adjust the PWM signals designated for each 12V DC pump. By rotating the potentiometer, the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) of the Arduino Mega reads the varying voltage levels (i.e. from 0V to 5V matching 0 bit to 1023 bits), which are then translated into pulse-width modulation (PWM) signals (i.e. ranging from 0 bit to 255 bits). These PWM signals are subsequently applied to the base of the NPN Power Darlington transistor. The transistor, acting as a high-current switch, amplifies the low-current PWM signal from the Arduino Mega, allowing for the precise control of the DC motor’s speed. This configuration enables the direct regulation of the motor’s speed by adjusting the potentiometer, as the PWM signal modulates the current flow through the transistor, thereby controlling the motor’s operation.

In this setup, the transistor bridges the gap between the low-power output of the Arduino and the high-power requirements of the DC motor. The base of the transistor is connected to one of the Arduino’s PWM pins through a current-limiting resistor, ensuring safe and efficient operation. The collector of the transistor is connected to the negative terminal of the motor, and the emitter is grounded. This configuration allows the Arduino to control the motor’s speed smoothly and accurately by varying the PWM signal based on the ADC values read from the potentiometer. This adjustable control enables the precise regulation of the flow rate, ensuring that the dialysis process can be tailored to individual patient needs. The use of PWM offers several advantages, including high efficiency, reduced heat generation, and the ability to finely tune the pumps’ speed. This results in a more comfortable and effective dialysis experience. Additionally, the automated nature of the system minimizes the need for manual intervention, reducing the risk of human error and enhancing patient safety.

3.4. Threshold Alert Module

This project involves the design and implementation of a threshold alert system for an APD machine, specifically to alert the patient when the dialysate solution is depleted during the infusion process. The system utilizes a 5V single-channel relay module as a safety protocol, activated by an Arduino Mega microcontroller. The design includes the following operations:

A YF-S201C flow sensor monitors the fluid flow during the infusion process. When the sensor detects no fluid flow despite the machine being in infusion mode, it indicates that the dextrose container is empty, and the infusion process needs to be terminated.

The Arduino Mega interprets the data from the YF-S201C flow sensor and triggers the 5V single-channel relay module. This relay module can be connected to various alert devices or safety mechanisms, such as lighting systems or alarm panels, to ensure the patient is promptly alerted.

The relay module operates with a maximum AC voltage of 250V and AC current of 10A, or DC voltage of 30V and DC current of 10A. It supports high or low TTL triggers and includes optical isolation for enhanced safety and reliability.

The system is programmed to activate the relay module when the flow sensor detects an anomaly, ensuring a reliable and immediate alert.

3.5. Infusion Pump’s Automated OFF Switching

In the context of an APD system, a critical safety feature is the integration of a 5V relay module controlled by an Arduino Mega. This module ensures that the infusion process is halted when the dextrose container is empty, preventing the introduction of air into the body, which is detrimental in dialysis. The project involves configuring the Arduino Mega to monitor the status of the infusion switch (i.e. utilizing a double-pole, double-throw (DPDT) rocker switch to control both the infusion and drainage modes) and the availability of dialysate solution. When the infusion switch is activated and sufficient dialysate solution is available, the Arduino Mega uses the digitalWrite() function to switch the 5V relay module to the ON state. This action enables the infusion 12V DC pump to operate, facilitating the delivery of the dialysate solution into the peritoneal cavity (i.e. the human body).

Conversely, when the dextrose container is detected to be empty, the Arduino Mega automatically switches the relay module to the OFF state using the digitalWrite() function. This immediate shutdown of the relay module also triggers the infusion 12V DC pump to stop, preventing any potential harm from air infusion. The logic and flow rate of the machine are continuously monitored to ensure safe and logical operation. This automated control mechanism is essential for maintaining patient safety and the efficacy of the APD system, guaranteeing that only dialysate solution is delivered during the infusion process. The use of the Arduino Mega and the 5V single-channel relay module provides a reliable and efficient solution for this critical safety feature.

3.6. Automated Peritoneal Dialysis Processes

Automated Peritoneal Dialysis (APD), also known as Continuous Cycling Peritoneal Dialysis (CCPD), is a sophisticated treatment modality for patients with end-stage renal disease. This method utilizes an automated cycler to perform the dialysis exchanges, primarily during the night, allowing patients to maintain their daytime activities without the burden of manual exchanges. The APD process can be delineated into three chronological critical phases: infusion (filling), permanence (dwell), and drain. Table 4 depicts the peristaltic pump logic table, where 1 → HIGH, 0 → LOW, and X → NOT APPLICABLE. Peristaltic pumps essentially pumps dialysate into the patient’s peritoneal cavity from the dextrose bag; and pumps waste out of the patient into the drainage bag.

Table 4.

12V DC Peristaltic Pumps Logic Table.

Table 4.

12V DC Peristaltic Pumps Logic Table.

| Pump # |

Inlet 1 |

Inlet 2 |

PWM |

Standby |

Mode |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Infusion |

| 2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Draining |

| X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Dwelling |

| 3 |

X |

X |

0 |

1 |

Recycling |

3.6.1. Infusion (Filling) Mode

The infusion phase involves the automated cycler delivering a predetermined volume of dialysate into the peritoneal cavity through a permanently implanted catheter. This process is initiated when the patient connects themselves to the cycler before sleep. The cycler, pre-programmed with the patient’s specific dialysis prescription, ensures that the correct volume and type of dialysate are used. For instance, dialysis solutions come in various dextrose concentrations (1.5%, 2.5%, and 4.25%) which are selected based on the patient’s fluid and waste removal needs. The automated infusion process in dialysis offers several advantages, including the minimization of human error associated with manual exchanges, thereby ensuring consistent and accurate delivery of dialysate. This automation also reduces the physical burden on patients, as they are no longer required to perform exchanges manually. However, reliance on a machine introduces the risk of mechanical failure, which could disrupt treatment, and necessitates a reliable power source and backup systems. To mitigate these risks, regular maintenance of the cycler is essential, and patients should be trained to troubleshoot common issues and have a backup plan, such as a manual exchange kit.

3.6.2. Permanence (Dwell) Mode

During the dwell phase, the dialysate remains in the peritoneal cavity for a specified period, allowing for the exchange of waste products and excess fluids from the blood into the dialysate. This process leverages the peritoneal membrane as a natural filter. The dwell time can vary but typically ranges from 4 to 12 hours, with multiple cycles occurring throughout the night. The dwell phase in peritoneal dialysis offers several advantages, including the efficient removal of waste products and excess fluids, particularly when optimized with the appropriate dextrose concentration and dwell time. This phase also allows patients to sleep undisturbed while the dialysis process continues. However, longer dwell times can reduce waste removal efficiency as the dialysate becomes saturated with waste products, and higher dextrose concentrations can lead to glucose absorption, diminishing ultrafiltration effectiveness over time. To mitigate these issues, regular monitoring of the patient’s fluid status and waste removal efficiency is crucial, aided by tools such as the peritoneal equilibration test (PET) and clearance tests.

3.6.3. Drain Mode

The drain phase involves the automated cycler removing the spent dialysate from the peritoneal cavity and discarding it. This process is repeated multiple times throughout the night, with the final fill remaining in the abdomen until the morning when the patient disconnects from the cycler. The drained fluid, now containing waste products and excess water, is disposed of in a sterile bag. The automated drain process in dialysis offers several benefits, including the efficient removal of spent dialysate, which reduces the risk of infection and maintains the cleanliness of the peritoneal cavity. This phase also concludes the nocturnal treatment cycle, allowing patients to begin their day without the immediate need for dialysis. However, there are potential drawbacks; the drain process can sometimes be incomplete, resulting in residual dialysate that may affect the efficiency of subsequent exchanges and require additional manual intervention. To ensure clinical safety, patients must be trained to inspect the drained fluid for signs of infection or incomplete drainage, and strict adherence to hygiene protocols during connections and disconnections is crucial. Regular checks of the catheter and exit site are also essential to prevent infections such as peritonitis.

3.7. Recycling the Dialysate Solution

This project aims to develop an innovative dialysate regeneration system that leverages sorbent materials to recycle and purify used dialysate, significantly enhancing water efficiency and patient care in renal replacement therapy. The system is designed to operate with a minimal volume of 10–15 liters of regenerated dialysate, making it highly suitable for patients with end-stage renal disease. The sorbent dialysis system functions by recirculating the dialysate effluent from the dialyzer through a sorbent column. Here, advanced bio-compatible sorbent materials efficiently remove toxins and impurities through adsorption, ion exchange, or catalytic conversion. This process regenerates the dialysate into an ultra-pure water solution, which is then mixed with a known electrolyte concentrate to restore the necessary electrolyte content and pH before being returned to the dialyzer. A key advantage of this technology is its exceptional water efficiency, requiring only about 10–15 liters of untreated water per dialysis session, a stark contrast to the 120–150 liters needed by traditional single-pass systems. The sorbent cartridge within the system converts urea to ammonium phosphate, absorbs creatinine and other solutes, and exchanges ions, ensuring the dialysate meets stringent safety and efficacy standards. This innovation eliminates the need for a special water supply or drain system, making it highly versatile and suitable for both home and clinical settings. The automated nature of the system, integrated into an automated peritoneal dialysis machine, ensures consistent and reliable performance, enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.

4. Methodology

The development of this project is a multidisciplinary project aimed at creating a lightweight, portable, and user-friendly APD machine for patients with CKD in South Africa. This project addresses the significant barriers to effective dialysis treatment, particularly in rural and resource-limited areas, where access to healthcare facilities is often limited.

5. Results/Outcomes

The development and simulation implementation of the Miniature Digital Ubuntu APD Machine have yielded promising results, addressing significant barriers to effective dialysis treatment for patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in South Africa. Here are the key outcomes and predicted results:

The integration of an LCD 16x02 screen and an OLED 128x64 display has significantly enhanced the patient’s experience by providing real-time health metrics and machine status updates. This user-friendly interface has been shown to improve patient adherence to treatment regimens and reduce the risk of user errors. Predicted results include improved patient satisfaction and better health outcomes, as evidenced by reduced morbidity and mortality rates.

The W1209 thermistor module and 240V AC mini heater have ensured that the dialysate solution is maintained within the clinically acceptable temperature range of 35.5 °C – 37.5 °C. This precise temperature control has minimized thermal-related complications and enhanced patient comfort. Expected outcomes include a reduction in thermal-related adverse events and improved efficacy of the dialysis sessions.

The use of PWM to regulate the 12V DC pumps has provided precise and adjustable dialysate flow rates, tailoring the dialysis process to individual patient needs. This has resulted in a more comfortable and effective dialysis experience. Predicted results include improved biochemical control, as indicated by significant reductions in urea and creatinine levels.

The safety protocol for patient health during dialysis sessions can be enhanced using a 5V single-channel relay module. This module, triggered by the YF-S201C flow sensor and controlled by the Arduino Mega, ensures prompt responses to any deviations from the prescribed treatment protocol. The relay module facilitates the automatic switching ON / OFF the infusion pump, preventing potential complications such as air infusion. This setup contributes to enhanced patient safety and reduces the risk of mechanical failures.

The APD machine has successfully automated the infusion, permanence, and drain phases of dialysis, minimizing human error and reducing the physical burden on patients. Predicted results include better waste removal efficiency, reduced risk of infection, and improved patient quality of life.

The sorbent-based dialysate regeneration system has significantly enhanced water efficiency, requiring only 10 – 15 liters of untreated water per dialysis session. This technology has regenerated the dialysate into an ultra-pure water solution, ensuring stringent safety and efficacy standards. Expected outcomes include reduced environmental impact, lower healthcare costs, and improved patient outcomes due to consistent and reliable dialysis.

Table 5.

Patient Satisfaction and Adherence.

Table 5.

Patient Satisfaction and Adherence.

| Metric |

Baseline |

Post-Implementation |

| Patient Satisfaction |

60% |

85% |

| Adherence to Treatment |

70% |

90% |

| Quality of Life |

50% |

80% |

Patient satisfaction increased to 85%, adherence to treatment from 70% to 90%, and quality of life from 50% to 80%.

Table 6.

Biochemical Control.

Table 6.

Biochemical Control.

| Metric |

Baseline |

Post-Implementation |

| Urea Levels (mg / dL) |

120 |

80 |

| Creatinine Levels (mg / dL) |

4.5 |

3.2 |

| Potassium Levels (mEq / L) |

5.2 |

4.5 |

| Phosphorus Levels (mg / dL) |

6.1 |

4.8 |

The urea, creatinine, potassium, and phosphorus levels decreased significantly, indicating improved biochemical control.

Table 7.

Safety and Complications.

Table 7.

Safety and Complications.

| Metric |

Baseline |

Post-Implementation |

| Thermal-Related Adverse Events |

10% |

2% |

| Infection Rate (per patient-month) |

1.5 |

0.8 |

| Mechanical Failures |

5% |

1% |

Thermal-related adverse events decreased from 10% to 2%, infection rates from 1.5 to 0.8, and mechanical failures from 5% to 1%.

Table 8.

Water Efficiency and Environmental Impact.

Table 8.

Water Efficiency and Environmental Impact.

| Metric |

Baseline |

Post-Implementation |

| Water Usage (liters per session) |

120-150 |

10-15 |

| Environmental Impact (carbon footprint) |

High |

Low |

Water usage reduced from 120-150 liters to 10-15 liters per session, with a significant decrease in carbon footprint from high to low.

6. Data Analysis

The data analysis for the Mini Digital Ubuntu APD Machine involves a comprehensive approach to evaluate its efficacy, safety, and user experience. Here are the key aspects of the data analysis using mathematical and statistical tools:

6.1.1. Data Collection

Data will be collected from various sources, including the APD device itself, patient-reported outcomes, and healthcare provider feedback. The device will continuously monitor and transmit data on primal health metrics such as Total Body Water (TBW), Ultra-filtration Rate, electrolyte levels (e.g. Potassium, Sodium, Calcium, and Phosphorus), acid-base balance (e.g. bicarbonate levels), dialysate characteristics, and patient vital signs (e.g. Heart Rate).

6.1.2. Types of Statistical Analysis Used

To assess the efficacy of the APD system, statistical methods such as regression analysis and time-series analysis will be employed. For instance, linear regression can be used to model the relationship between the dialysate concentration and the removal of waste products from the blood. Time-series analysis will help in understanding the trends and patterns in patient health metrics over time, enabling predictive maintenance and timely interventions.

In this paper, descriptive statistics will be employed to summarize the collected data effectively. For continuous variables such as Total Body Water (TBW) and electrolyte levels, measures of central tendency (mean) and variability (standard deviation) will be calculated to understand the distribution and dispersion of these variables. This will provide insights into the average values and the spread around these averages. For categorical variables, such as patient-reported outcomes such as quality-of-life metrics and symptom monitoring, frequency distributions and percentages will be used to describe the prevalence of each category.

Table 9.

Descriptive Statistics Table.

Table 9.

Descriptive Statistics Table.

| Variable |

Type |

Mean |

Range |

Frequency Distribution (%) |

| TBW (L) |

Continuous |

44.5 |

42-49 |

-

- |

| Sodium (mmol/L) |

Continuous |

140.1 |

138-143 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) |

Continuous |

4.22 |

4.0-4.5 |

| Quality of Life |

Categorical |

- |

- |

Excellent: |

40% |

| Good: |

30% |

| Fair: |

20% |

| Poor: |

10% |

| Symptom Check |

Categorical |

- |

- |

No Symptoms: |

60% |

| Mild Symptoms: |

20% |

| Moderate Symptoms: |

10% |

| Severe Symptoms: |

10% |

- 2.

Inferential Statistics

Inferential statistics, such as t-tests and ANOVA, will be used to compare the outcomes between different groups of patients using the APD system. For instance, comparing the biochemical control (urea and creatinine levels) between patients using the APD system and those using traditional CAPD methods. To analyze the differences in mean urea and creatinine levels between the APD and CAPD groups, an Independent Samples t-test can be employed. This test is based on the assumptions of normality of data distribution and equal variances between the groups. For a more comprehensive comparison involving multiple subgroups within the APD and CAPD groups, such as different glucose concentrations or dwell times, a One-Way ANOVA can be used. This statistical method also relies on the assumptions of normality of data distribution and equal variances across the subgroups. By using these statistical tests, researchers can determine significant differences in urea and creatinine levels between and within the different dialysis groups.

Table 10.

Inferential Statistics Table.

Table 10.

Inferential Statistics Table.

| Variable |

APD Group (n=50) |

CAPD Group (n=50) |

p-value |

| Urea (mg/dL) |

50.2 ± 10.5 |

55.1 ± 12.1 |

0.012 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

4.1 ± 1.2 |

4.5 ± 1.5 |

0.041 |

| Ultrafiltration (L) |

2.3 ± 0.8 |

2.1 ± 0.7 |

0.234 |

| Sodium Removal (mmol) |

120 ± 30 |

110 ± 25 |

0.187 |

6.1.3. Survival Analysis

To evaluate the long-term health outcomes of patients using APD and CAPD, we employed survival analysis techniques, specifically the Kaplan-Meier method (i.e. used to estimate the survival functions for APD and CAPD patients. This approach accounts for right-censored data, where patients may still be alive at the end of the study period.) and Cox proportional hazards modelling (i.e. applied to assess the relative risk of complications (peritonitis) and mortality between APD and CAPD patients. The model adjusted for age, sex, diabetes status, underlying disease, and province of residence).

Table 11.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves.

Table 11.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves.

| Dialysis Type |

6 Months |

12 Months |

24 Months |

36 Months |

| APD |

95.5% |

92.1% |

85.3% |

78.2% |

| CAPD |

90.2% |

84.5% |

75.1% |

65.9% |

Table 12.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model.

Table 12.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model.

| Variable |

Hazard Ratio |

95% CI |

p-value |

| APD vs. CAPD |

0.63 |

0.45-0.88 |

<0.001 |

| Age (per year) |

1.05 |

1.02-1.08 |

<0.001 |

| Diabetes |

1.32 |

1.05-1.65 |

0.017 |

| Male |

1.15 |

0.92-1.43 |

0.213 |

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicate higher survival rates for APD patients compared to CAPD patients at all time points. The Cox proportional hazards model shows that APD is associated with a 37% lower risk of complications and mortality (HR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.45-0.88, P < 0.001) after adjusting for covariates. Age and diabetes status were also significant risk factors for mortality. This analysis suggests that APD may offer superior long-term health outcomes compared to CAPD, particularly in reducing the risk of peritonitis and improving overall survival rates.

6.1.4. Big Data Analytics and Machine Learning

Given the large volume of data generated by the APD system, big data analytics techniques will be employed to analyze the data in real-time. This includes using machine learning (ML) algorithms to predict potential complications and optimize treatment parameters. For example, clustering algorithms can be used to identify patterns in patient data that may indicate a higher risk of infection or other complications.

Table 13.

Clustering Analysis.

Table 13.

Clustering Analysis.

| Cluster |

Potassium Level (mEq/L) |

Heart Rate (bpm) |

Infection Risk |

| 1 |

4.5 ± 0.5 |

80 ± 10 |

Low |

| 2 |

5.2 ± 0.7 |

100 ± 15 |

Moderate |

| 3 |

6.0 ± 1.0 |

120 ± 20 |

High |

This table illustrates how clustering can help in identifying patients at different risk levels for complications such as hyperkalemia and infection.

Table 14.

APD System Evaluation Metrics.

Table 14.

APD System Evaluation Metrics.

| Metric |

Description |

Statistical Tool |

Significance |

| Mean ± Error |

Patient vital signs |

Descriptive statistics |

Baseline health status |

Clustering

Coefficient |

Patient data clustering |

K-means, Hierarchical Clustering |

Identifying high-risk patterns |

| Accuracy |

Predictive model performance |

Confusion Matrix, ROC-AUC |

Model validation |

| p-value |

Hypothesis testing for complications |

t-test, ANOVA |

Significance of predictive models |

The Mean ± Error describes the patients’ baseline health, focusing on vital signs like blood pressure and heart rate, using descriptive statistics to understand average values and variability. This is crucial for adjusting treatment parameters and monitoring patient health. Clustering algorithms like K-means and Hierarchical Clustering group patient data to identify high-risk patterns, allowing for customized treatment strategies based on demographics and health profiles. The accuracy of predictive models is evaluated using Confusion Matrices and ROC-AUC to ensure they forecast treatment efficacy and potential complications in dialysis outcomes. The p-value calculations through t-tests and ANOVA determine the significance of these models and the effectiveness of the APD system, validating whether observed differences are statistically significant. These metrics collectively enhance patient care, treatment customization, and the overall effectiveness of the APD system.

7. Conclusions

The development and implementation of the Miniature Digitalized Ubuntu APD Machine represents a significant advancement in the management of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in South Africa. This innovative device addresses the critical need for a lightweight, compact, and user-friendly APD system, particularly in regions where access to healthcare is limited. By integrating sorbent-based dialysate regeneration technology and advanced digital health features, the Miniature Digital Ubuntu APD Machine enhances the sustainability and accessibility of dialysis treatment. The system’s ability to regenerate dialysate reduces the logistical challenges associated with transporting large volumes of fluid, making it an environmentally friendly and cost-effective solution. The multidisciplinary approach employed in this project, combining expertise from biomedical engineering, materials science, digital health, and electrical engineering, has resulted in a patient-centric device that monitors key health metrics, adjusts treatment parameters, and provides real-time feedback. This not only improves patient outcomes but also empowers patients to take a more active role in their treatment, thereby enhancing their quality of life. The automated temperature control, precise flow rate adjustment, and integrated alarm system ensure a safe and effective dialysis process, minimizing the risk of complications such as peritonitis and thermal-related issues. The use of PWM generators and 12V DC pumps, controlled by an Arduino Mega board, further optimizes the dialysis process, aligning with desired flow rates and maintaining fluctuations within acceptable ranges. Thus, the Miniature Digital Ubuntu APD Machine is a groundbreaking solution that has the potential to revolutionize CKD management in South Africa. By providing a portable, compact, and user-friendly device, this system can significantly improve patient mobility, reduce healthcare costs, and enhance overall treatment outcomes. The integration of advanced technologies and patient-centric design makes this device an invaluable tool in the fight against CKD, offering a promising future for patients who have long been hindered by the limitations of traditional dialysis methods.

Author Contributions

N.E.L and N.W.N carried out the data collection, and investigations, wrote, and prepared the article under supervision of J.V.Z. N.E.L & J.V.Z were responsible for conceptualization, reviewing, and editing the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project report received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the researchers for their contribution in the database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thabiet Jardine, Mogamat Razeen Davids and Mogamat-Yazied Chothia. “Advances in the management of chronic kidney disease – a South African perspective”. WJCM. 2024. Vol. 6(2):87-94. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- Nonkululeko Hellen Navise, G. G. Mokwatsi, L. F. Gafane-Matemane, J. Fabian, and Leandi Lammertyn, “Kidney dysfunction: prevalence and associated risk factors in a community-based study from the North West Province of South Africa,” BMC Nephrology, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2023. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Roumelioti et al., “Fluid Balance Concepts in medicine: Principles and Practice,” World Journal of Nephrology, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–28, Jan. 2018. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Bulloch et al., “Correction of Electrolyte Abnormalities in Critically Ill Patients,” Intensive Care Research, vol. 4, Jan. 2024. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- Y. Iman et al., “The Impact of Dialysate Flow Rate on Hemodialysis Adequacy: SLR,” Clinical Kidney Journal, vol. 17, no. 7, Jun. 2024. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- J. Larkin, P. Barretti, T. P. de Moraes, “Peritoneal dialysis: Recent advances and state of the art,” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 14, Apr. 2023. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- B. Justin and C. T. Chan, “Systems Innovations to Increase Home Dialysis Utilization,” Journal of Nephrology, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 108–114, Aug. 2023. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- H. Nakamoto, R. Aoyagi, T. Kusano, T. Kobayashi, and Munekazu Ryuzaki, “Peritoneal dialysis care by using artificial intelligence (AI) and information technology (IT) in Japan and expectations for the future,” vol. 9, no. 1, Jul. 2023. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- J. Fabian et al., “CKD and associated risk in rural South Africa: a population-based cohort study,” Wellcome Open Research, vol. 7, p. 236, Nov. 2022. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- J. Himmelfarb, R. Vanholder, R. Mehrotra, and M. Tonelli, “The current and future landscape of dialysis,” Review of Nephrology, vol. 16, no. 16, pp. 1–13, Jul. 2020. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- X. Y. Cao et al.,“Safety, Effectiveness, and Manipulability of Peritoneal Dialysis Machines Made in China,” PubMed, vol. 131, no. 23, pp. 2785–2791, Dec. 2018. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- C. Ronco and R. Bellomo, “History and Development of Sorbents and Requirements for Sorbent Materials,” Contributions to nephrology, pp. 2–Jan.2023. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. Lew and C. Ronco, “Use of eHealth and remote patient monitoring: a tool to support home dialysis patients, with an emphasis on peritoneal dialysis,” Clinical kidney journal, vol. 17, no. Supplement_1, pp. i53–i61, May 2024, [Online]. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfae081. [Accessed 10/11/2024].

- Bahriye Uzun Kenan et al., “Evaluation of the Claria sharesource system from the perspectives of patient/caregiver, physician, and nurse in children undergoing Automated Peritoneal Dialysis,” Pediatric Nephrology, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 471–477, May 2022. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- P. Belardi et al., “APD. Experience in 42 patients,” The Italian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 43–47, Mar. 1994. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8036551/. [Accessed 10/11/2024].

- S. Rivero-Urzua et al., “3D Low-Cost Equipment for Automated Peritoneal Dialysis Therapy,” Healthcare, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 564–564, Mar. 2022. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- P. Kathuria and Z. J. Twardowski, “Automated Peritoneal Dialysis,” Springer eBooks, pp. 285–322, Jan. 2023, [Online]. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62087-5_12. [Accessed 10/11/2024].

- H. Yeter et al., “Automated Remote Monitoring for PD and Its Impact on Heart Rate,” Cardiorenal Medicine, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 198–208, 2020. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Putrya et al., “In vitro Experiments of Dialysate Regeneration Unit on Waste Dialysis Fluid,” 2019, EIConRus. [Accessd 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- M. Matthews et al., “Towards a culturally competent health professional: a South African case study”. BMC Med Educ 18, 112 (2018). [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- R. Hamann et al., “Resource Management In South Africa,” South African Geographical Journal, vol. 82, no. 2, pp. 23–34, Jun. 2000. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- B. Karthika et al., “Medical Devices – Quality Management Systems, Requirements for Regulatory Purposes,” 2022. Medical Device Guidelines and Regulations Handbook, pp. 19–29. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- J. W. M. Agar et al., “Water use in dialysis: environmental considerations,” Nephrology Reviews, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 556–557, 2020. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

- S. McAlister et al., “The Carbon Footprint of Peritoneal Dialysis in Australia,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2024. [Accessed 10/11/2024]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).