1. Introduction

In Western democratic societies, women’s sexuality continues to be assessed against a standard that distinguishes between virtue, embodied by sexual abstinence and shyness (i.e., the “virtuous” woman), and promiscuity, marked by hypersexuality and activity (i.e., the “promiscuous” woman) [

1]. Gender norms influence the expected behaviors of men and women, particularly in relation to sexual conduct [

2,

3]. When a young Western woman has to decide what the most appropriate sexual behavior is or what her attitude toward sexual consent should be, she faces a complex regulatory environment.

First, this framework promotes expectations that women (compared to men) should demonstrate greater passivity, submission, and less sexual agency [

4,

5]. Studies conducted with samples of Spanish speakers have shown that a gender double standard is associated with sexual behavior, both regarding the open expression of sexuality (i.e., sexual freedom) and modesty in sexuality (i.e., sexual shyness) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. At the same time, young Western women are encouraged to exercise agency—to become assertive initiators who challenge traditional gendered sexual norms. Within this context, sexual agency should be understood as a new normative dimension, promoting liberation from external constraints (e.g., submission to traditional gender roles) and encouraging the exercise of free will and personal responsibility [

1,

11].

It has been suggested that the agency norm and the norm regarding gendered sexual behaviors (sexual activity vs. abstinence-modesty) are independent dimensions that maintain an orthogonal relationship [

1]. This normative environment, with its contradictory expectations—e.g., abstain-act, reject-initiate, be sexually receptive-become an agent of one’s sexuality [

12,

13]—is believed to induce concern in women about being judged according to stereotypes associated with their social group [

14].

A threat to one’s sexual reputation may emerge when others (i.e., society at large) negatively evaluate a woman’s behavior [

15,

16]. The ambiguity within the normative context can undermine a woman’s reputation if she exhibits uninhibited sexual attitudes and behaviors, or alternatively, if she favors sexual abstinence. Research indicates that women who are assertive and sexually active may be viewed both as desirable sexual partners [

17] and as promiscuous, easy, or selfish [

5,

18]. The central aim of this research is to examine the impact of this normative environment, typical of contemporary Western societies, on young women’s self-image and their attitude toward sexual consent. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that examines, using a quasi-experimental methodology, the combined effect of sexual norms on young women's identification with stereotypical traits and their attitude toward sexual consent.

The fear of confirming negative stereotypes may lead to the internalization of stereotypical expectations and roles, which can adversely affect women’s self-image [

19,

20]. Society’s evaluation of a particular group is reflected in the ascription of characteristics that shape that group’s stereotype. In this regard, the traits that form the content of stereotypes are organized into dimensions with varying social values, such as competence and sociability [

18,

21], culture and nature [

22], as well as feelings and emotions [

23]. Within this framework, we propose:

Hypothesis 1. When a woman’s sexual activity is devalued or negatively judged by others, it can detrimentally affect her self-image [

19,

20]. Specifically, it may influence her tendency to identify with positive and negative traits associated with competence, sociability, nature, culture, feelings, and emotions.

Furthermore, the perception that women have that their sexual behavior may be devalued by the context, can make heterosexual intimate encounters a threat to gender identity [

14,

24]. In this regard, the normative context can influence a woman’s attitude toward sexual consent (SC), which represents the conscious willingness to engage in a specific sexual behavior with a specific person and within a specific context [

25]. We propose:

Hypothesis 2. When a woman’s sexual activity is devalued or viewed negatively by others, it may influence her attitude toward sexual consent.

It has been suggested that situations involving stereotype threat [

20] induce dissonance in individuals, as they experience an imbalance among various elements: the stereotype of their social group (e.g., “women are not expected to be sexually assertive”), the area of capability in question (e.g., “I am a sexually assertive woman”), and self-concept (“I am a woman”) [

26]. According to this model, interventions to counter stereotype threat aim to foster beliefs that can alter the imbalance among these dissonant elements, for instance, by changing one’s beliefs about the stereotype [

27]. As previously noted, the norm of agency promotes freedom from external restrictions (i.e., traditional gender sexual roles) [

1]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the threat to sexual reputation arising from social evaluation may have a different effect depending on whether a woman believes her degree of agency is high (e.g., “sexual behavior depends on individual personality”) or, conversely, believes her agency is limited (e.g., “as a woman, I am expected to meet certain expectations”). In this context, it is worth asking (RQ1) to what extent beliefs about agency (i.e., high-agency vs. low-agency) may moderate the threat to a woman’s sexual reputation. In developing our hypotheses, we first consider that the agency norm reinforces the belief in free will and personal responsibility [

1]. Second, that the nature of the cause (i.e., external to the individual vs. internal, or related to a personal trait) to which an outcome is attributed produces different affective responses, which in turn influence self-esteem and behavior [

28]. For instance, the negative evaluation of one’s sexual behavior by others can be attributed either to a personal trait or to gender stereotypes. Based on this approach, we propose:

Hypothesis 3. When the belief in ample freedom to exercise free will is reinforced—High-agency beliefs (vs. when one believes that sexual behavior is regulated by expectations or gender norms: low-agency beliefs)—self-image will be more negatively affected.

Hypothesis 4. When the belief in ample freedom to exercise free will is reinforced—High-agency beliefs (vs. when one believes that sexual behavior is regulated by expectations or gender norms: low-agency beliefs)—the attitude toward sexual consent will be more negatively affected.

Hypothesis 5. An interaction effect is expected to be found between threat to personal reputation and beliefs about agency [

26].

Finally, certain personal characteristics may influence an individual’s response when faced with a situation that threatens one’s sexual reputation due to gender norms and stereotypes. Firstly, the more a person identifies with the group that is negatively evaluated, or the more they expect to be perceived as a member of that group, the greater the stereotype threat they will experience in situations where a negative stereotype is applied [

14]. In this regard, we ask two questions: what role does the centrality of gender identity play in women’s responses? (RQ2) and what role does their gender self-esteem play? (RQ3). Secondly, individuals who hold a neoliberal ideology are more likely to support and conform to the agency norm [

29]. From this framework, we ask: What role does women’s adherence to neoliberal ideology play? (RQ4). Lastly, an individual’s perception of norms, such as those related to gendered sexual behaviors and the sexual double standard (SDS) [

30], directly influences the willingness to endorse stereotypes [

31,

32]. Therefore, it is important to analyze the role that perceived social support for gendered sexual norms and the SDS plays in women’s responses when they perceive their sexual reputation to be devalued (RQ5).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The study followed a quasi-experimental, between-groups design (2 x 2) with two independent variables. The first manipulated variable was Threat to Personal Reputation (due to sexual activity vs. sexual abstinence), and the second was Affirmation in Agency Beliefs (High-Agency Beliefs vs. Low-Agency Beliefs). The dependent variables included identification with 32 characteristics corresponding to eight dimensions (i.e., competence, sociability, sentiment, emotion, nature, culture, collectivism, individualism) and attitude toward sexual consent. Covariates considered in the manipulation included gender identity centrality, gender-based self-esteem, neoliberal beliefs and values, and perceived societal support for gendered sexual norms and the sexual double standard.

2.2. Participants

A total of 202 participants accessed the questionnaire link. Thirty participants were excluded because they did not affirmatively respond to the experimental manipulation check regarding Threat to Personal Reputation (see the “Procedure” section). An additional 18 participants were excluded for not responding to the manipulation check question on Affirmation in Agency Beliefs (see the “Procedure” section). The final sample consisted of 154 adult female Spanish undergraduates (Mage = 19.69 years; SD = 2.23). Among them, 43.5% reported being in a romantic relationship, and 79.1% of those identified as heterosexual. The distribution of participants across experimental conditions for multivariate analyses was as follows: Threat for Sexual Activity – Low-agency Beliefs (N = 34), Threat for Sexual Activity – High-agency Beliefs (N = 44), Threat for Sexual Abstinence – Low-agency Beliefs (N = 40), and Threat for Sexual Abstinence – High-agency Beliefs (N = 36). In cases where specific items were left unanswered, data was not extrapolated. Instead, missing responses were excluded from the analyses affected.

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of [blinded] (reference n. [blinded]). Data collection took place in a classroom setting. Each experimental session included up to 25 participants, who were welcomed by a female researcher trained in administering the study protocol. Participants were informed that the study aimed to understand how self-perceptions or self-images are shaped when individuals receive information about their sexual profiles or behaviors. To enhance the credibility of the experimental manipulation, participants were told that their responses would contribute to databases used by Artificial Intelligence (AI) programs to develop personal profiles.

Participants completed the assessment using the LimeSurvey platform, accessed via a QR code. Four distinct QR codes were created, one for each set of questions corresponding to the four experimental conditions. Using incidental non-probability sampling, each participant was assigned one of the QR codes. Upon accessing the application, participants signed an informed consent form before responding to the study measures. The sequence of instrument presentation and manipulations was structured as follows: first, participants completed scales measuring variables treated as covariates in the analyses.

Subsequently, the manipulation of Threat to Personal Reputation was introduced. Participants were provided with hypothetical sexual profiles based on their responses to the survey up to that point. Half of the participants were informed that their responses aligned with the profile of a sexually active and assertive woman (condition: Threat to Personal Reputation for Sexual Activity), while the other half were informed that their responses aligned with the profile of a sexually reserved and abstinent woman (condition: Threat to Personal Reputation for Sexual Abstinence). In both cases, participants were told that society generally holds a negative view of the corresponding sexual profile. To ensure that participants had read the provided information about their assigned sexual profile, a verification question was included.

Following this, was introduced the manipulation of the second independent variable (Affirmation in Agency Beliefs). Half of the participants were asked to write beliefs affirming the existence of sexual agency for women (High-agency Beliefs), while the other half were asked to write beliefs denying sexual agency for women (Low-agency Beliefs). In this case, manipulation verification was ensured by participants providing any written response. Finally, participants completed scales measuring the dependent variables.

2.4. Materials

Socio-demographic Questionnaire. This section included questions about gender, age, nationality, sexual orientation, education, and relationship status, among others.

Identity Subscale of the Collective Self-Esteem Scale (ISE-CSES). Adapted from Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) [

33], this scale measures the centrality of gender identity. Its four items are answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (

strongly agree) to 7 (

strongly disagree). In this study’s sample, the internal consistency reliability was α = .74.

Gender Self-Esteem Scale (GSES). Based on the work of Falomir-Pichastor and Mugny (2009) [

34] and Falomir-Pichastor et al. (2017) [

35], this scale evaluates the extent to which participants possess positive gender self-esteem. It comprises three items (e.g., "In general, I have a very high self-esteem as a woman"), answered on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (

strongly disagree) to 7 (

strongly agree). In this study’s sample, the internal consistency reliability was α = .60.

Neoliberal Beliefs and Values Questionnaire

, based on the

Neoliberal Beliefs Inventory (NBI) [

29], this instrument used 14 items rated on a Likert scale from 1 (

strongly disagree) to 6 (

strongly agree). These items correspond to two factors from the original scale: Competition (NBI1) (e.g., “Competitiveness is a good way to discover and motivate the most talented people”) and Personal Wherewithal (NBI2) (e.g., “A person’s success in life is more determined by their personal effort than by society”). Higher scores indicate a stronger endorsement of neoliberal beliefs. In this study’s sample, internal consistency reliability was α = .59 for NBI1 and α = .87 for NBI2.

Spanish Hetero-referred Version of the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS-H). Adapted from Muehlenhard and Quackenbush (2011) [

36] and Gómez-Berrocal et al. (2019) [

30], this scale measures perceived normativity, specifically the extent to which participants believe society accepts certain gender norms regarding sexual behavior. The scale comprises 18 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree), divided into three factors: Social Acceptance of Male Sexual Shyness (SAMSS), Social Acceptance of Female Sexual Freedom (SAFSF), and Social Acceptance of Sexual Double Standard (SASDS). In this study’s sample, internal consistency reliability was α = .65, α = .50, and α = .88 for SAMSS, SAFSF, and SASDS, respectively.

Self-Perception Measure. This measure consists of a list of 32 characteristics that assess the extent to which participants believe these traits describe them, rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 6 (completely). These characteristics are grouped into eight theoretical dimensions. Six dimensions are based on the Stereotype Content Model [

18,

21] and procedures used by Gómez-Berrocal et al. (2011) [

37]:

Competence (e.g., intelligence) and

Sociability (e.g., generosity);

Feeling (e.g., optimism) and

Emotion (e.g., suffering) [

38];

Nature (e.g., intuition) and

Culture (e.g., creativity) [

22]. Additionally, two extra dimensions were included: Individualism (e.g., autonomy) and Collectivism (e.g., solidarity). Each dimension included four characteristics, half with a positive connotation (e.g., Feeling: optimism) and half with a negative connotation (e.g., Feeling: remorse). Based on participants’ responses, eight Self-Assessment Indices (SAI) were calculated to measure the tendency to identify with positive or negative traits within each dimension (COM: Competence, SOC: Sociability, CUL: Culture, NAT: Nature, FEEL: Feeling, EMO: Emotion, IND: Individualism, and COLL: Collectivism). For each index (e.g., Self-Assessment Index for Competence: SAI-COM), the sum of responses to positive traits within a dimension (e.g., positive competence) was subtracted from the sum of responses to negative traits within the same dimension (e.g., negative competence). Higher positive SAI scores indicate a stronger tendency to identify with positive traits over negative ones within a given dimension. Independent of dimension, additional scores were calculated for the overall tendency to identify with positive traits (POSIT) and negative traits (NEGAT).

Spanish Adaptation of the Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R). Adapted from Humphreys and Brousseau (2010) [

39] by Moyano et al. (2023) [

40], the Spanish version consists of 26 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 =

completely disagree to 7 =

completely agree). The scale includes four factors: Perceived Lack of Behavioral Control, Positive Attitude Toward Establishing Consent, Indirect Behavioral Approach, and Sexual Consent Norms. For this study, only two factors were analyzed: Perceived Lack of Behavioral Control (F1) and Attitude in Favor of Establishing Sexual Consent (F2). Internal consistency reliability for this study’s sample was α = .92 for F1 and α = .89 for F2.

2.5. Data Analysis

Three Multivariate Analyses of Covariance (MANCOVA) were conducted. In each analysis, two fixed factors were included: (1) Threat to Personal Reputation (with two levels: Sexual Activity and Sexual Abstinence) and (2) Affirmation in Agency Beliefs (with two levels: High-agency Beliefs and Low-agency Beliefs). Covariates included scores on the ISE-CSES, GSES, NBI1, and NBI2 scales, as well as perceptions of societal support for gendered sexual norms (i.e., Social Acceptance of Male Sexual Shyness (SAMSS), Social Acceptance of Female Sexual Freedom (SAFSF), and Social Acceptance of the Sexual Double Standard (SASDS).

Regarding the dependent variables, the first MANCOVA included POSIT and NEG. In the second MANCOVA, the dependent variables were the eight Self-Assessment Indices (SAI) corresponding to each dimension (COM: Competence, SOC: Sociability, CUL: Culture, NAT: Nature, FEEL: Feeling, EMO: Emotion, IND: Individualism, and COLL: Collectivism). In the third MANCOVA, the dependent variables were the two factors of the sexual consent scale: Perceived Lack of Behavioral Control and Attitude in Favor of Establishing Sexual Consent. Partial eta-squared (ηp2) was used to quantify effect sizes.

The normality of distributions was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test to ensure the suitability of parametric analyses.All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 28.

4. Discussion

This study assumes that in contemporary Western societies, women’s sexual behavior and attitudes are regulated by a complex normative context resulting from two normative dimensions. On the one hand, the norm derived from the sexual double standard (SDS), which governs behaviors related to sexual activity and abstinence, promotes a negative evaluation of women who are assertive and sexually active [

4,

5,

7,

10]. On the other hand, the norm of sexual agency, more recent in Western democratic societies, encourages young women to assertively express their own sexuality, opposing submission to traditional gender roles [

1,

11].

From this framework, and using a quasi-experimental design, we manipulated two factors [Threat to personal reputation: for sexual activity vs. for sexual abstinence, and Affirmation in Agency Beliefs: High-agency Beliefs vs. Low-agency Beliefs] to study, first, the effect on participants' identification with positive and negative traits that constitute the dimensions of stereotypes content [

18]. Secondly, we examined the effect of this complex normative context on young women’s attitude toward sexual consent [

25].

How Did Threat to Personal Reputation Affect Participants?

We hypothesized that fear of confirming negative stereotypes might lead to the internalization of stereotypical expectations and roles, and thus, inducing a threat to personal reputation could negatively impact women’s self-image [

19,

20]. Specifically, we questioned how young women would be affected when exposed to a threat to their personal reputation via negative evaluation of their supposed sexual profile (i.e., characterized by sexual activity or sexual abstinence). We expected this situation to affect both their tendency to identify with positive and negative characteristics related to the dimensions of stereotype content [

18] (H1), and their attitude toward sexual consent [

25] (H2).

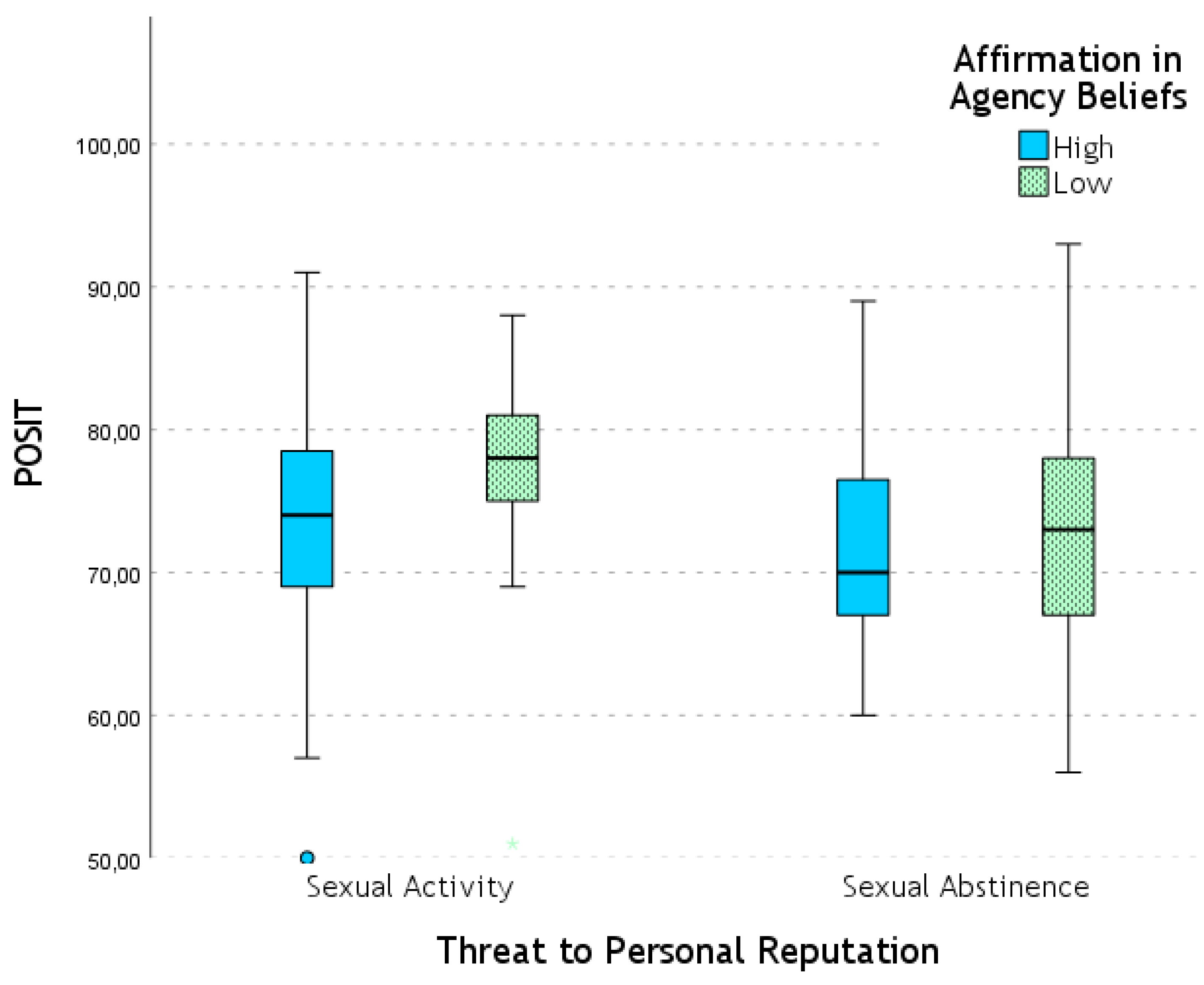

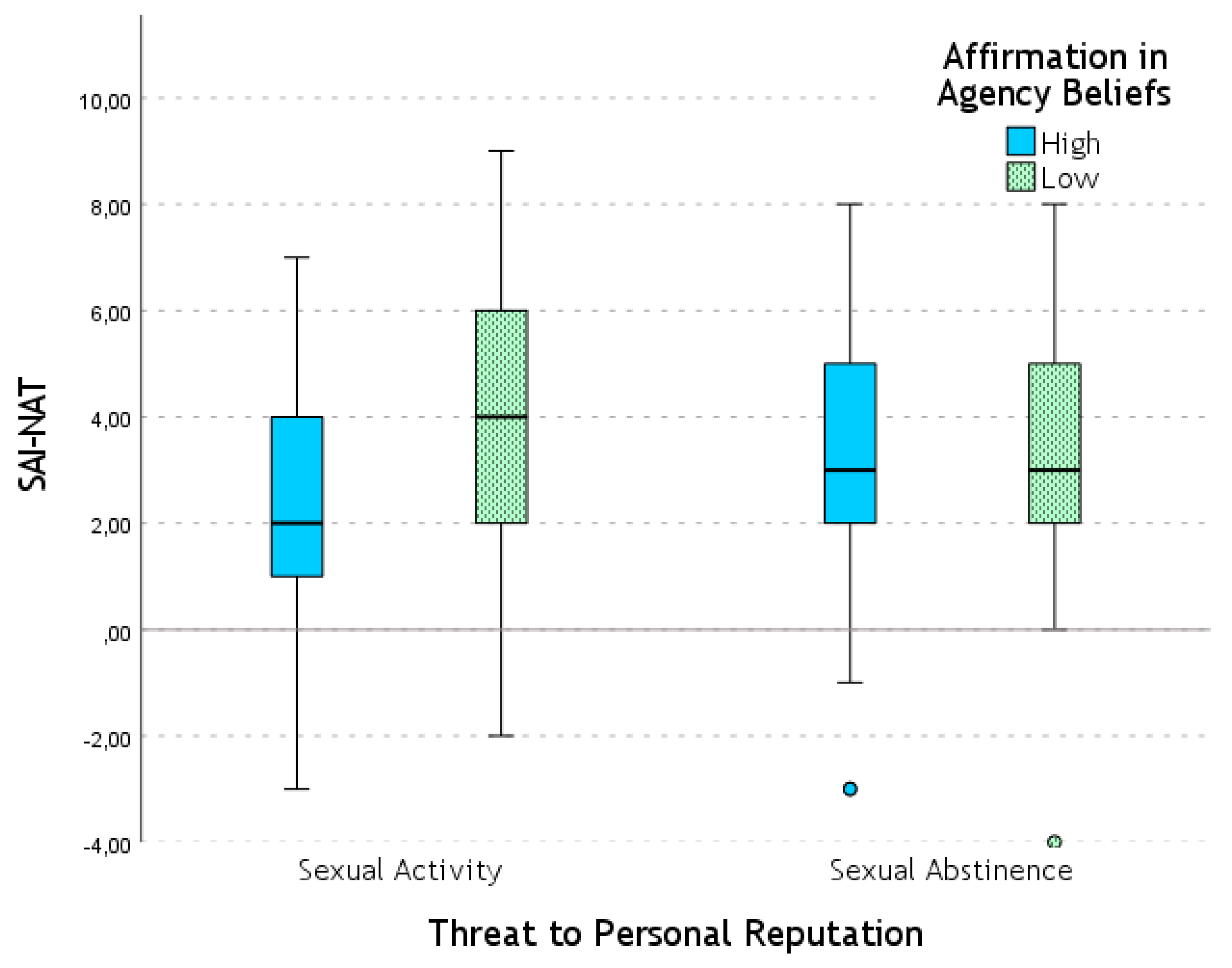

The first hypothesis is partially confirmed. We found that Threat to personal reputation has a significant effect on the tendency of participants to identify with positive traits across all dimensions, with this tendency being more pronounced when the Threat to personal reputation is for sexual activity (vs. sexual abstinence). At the limit of significance, girls’ participants whose reputation was threatened due to sexual activity, compared to those whose reputation was devalued due to sexual abstinence, tended to identify more with positive traits than with negative traits corresponding to the competence and collectivism dimensions.

The competence dimension, also referred to as "masculinity" or "instrumentality" [

18,

41], involves qualities relevant for achieving individual goals and objectives [

42]. Previous studies have shown that self-perception in terms of positively valence traits and competence is related to self-enhancement motives [

41] and contributes to projecting an image of being capable of overcoming challenges [

43]. Additionally, within the framework of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) [

18,

21,

44], groups are perceived as more competent when they have high status and power. Thus, these findings suggest that the devaluation of young women’s personal reputation due to sexual activity prompts a tendency to emphasize their competence-related agency [

42], potentially as a strategy to reaffirm their social status [

18,

44].

Self-descriptions in terms of collectivism-individualism are culturally influenced, with people in Western cultures having an independent self-view, emphasizing separation from others [

45]. The sample in this study consisted of young Spanish women, belonging to a Western society. Nonetheless, albeit at the border of statistical significance, girl’s participant whose reputation was devalued due to sexual activity (vs. sexual abstinence) tended to describe themselves in collectivist terms, highlighting their connection to others and an interdependent self-concept.

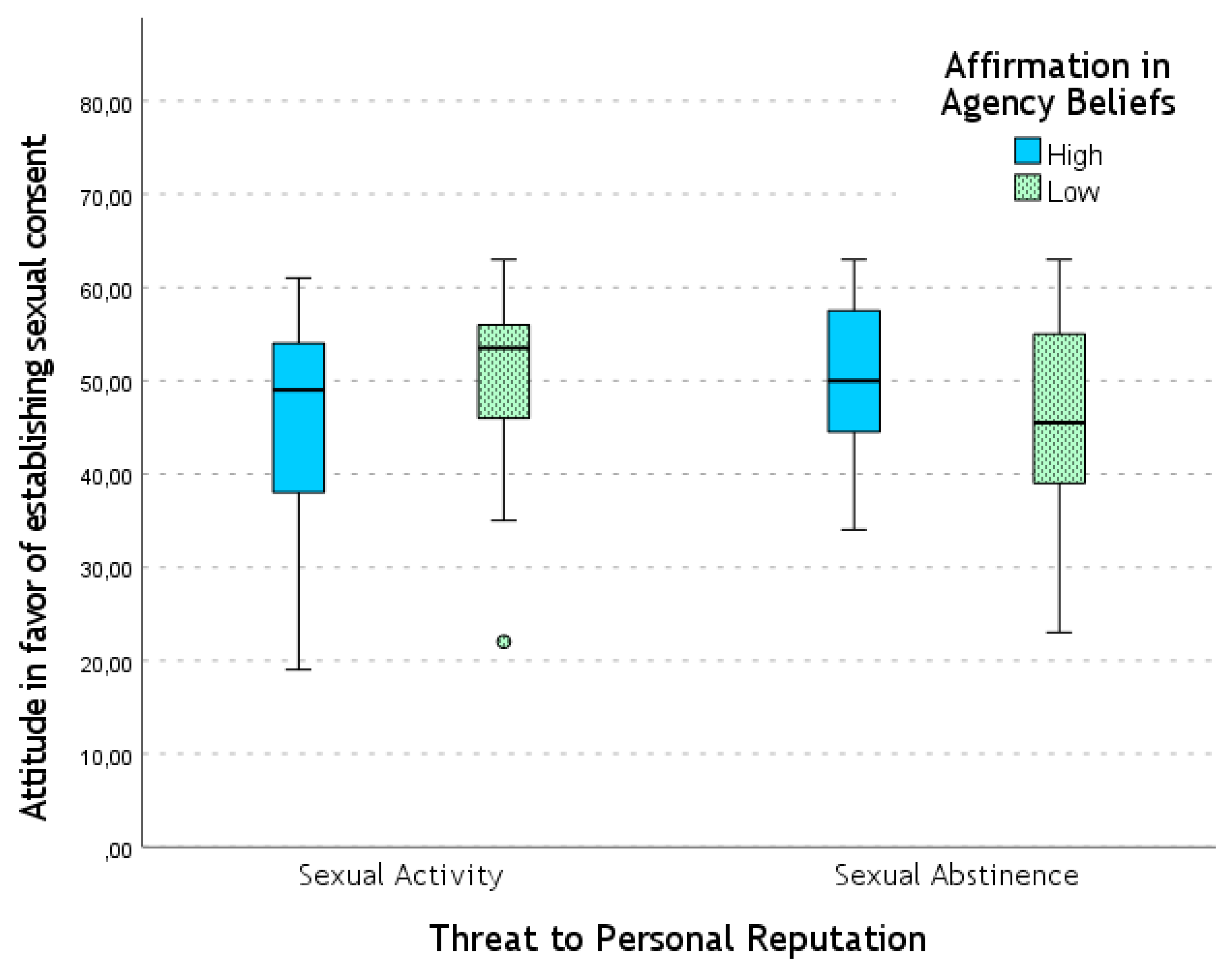

We found no support for our H2, as no significant main effect of Threat to personal reputation was observed on attitudes toward sexual consent.

How Did Affirmation in Agency Beliefs Affect Participants?

The agency norm reinforces the belief in free will and personal responsibility [

1]. We hypothesized that affirming agency beliefs might enhance expectations of control and responsibility over the consequences of one’s behavior [

28].

Our results partially support H3. We found that participants who affirmed that women’s range of sexual freedom is low (i.e., Low-agency beliefs) were more likely than those who affirmed high-agency beliefs, to identify with positive traits across all dimensions of the stereotype, and especially with positive rather than negative traits in the dimensions of sociability, individualism, and culture.

The sociability dimension, also referred to as "communion," "warmth," "femininity," or "morality" [

18,

41], involves qualities relevant to social group belonging [

42]. Sociable individuals create an impression of warmth and morality in others [

18,

43].

The

nature-culture dimension underpins a social classification where certain minority groups are excluded from the social map (ontologization) [

22]. While culture defines human identity, nature is associated with animal identity. Evidence suggests that women may be undervalued by being attributed traits less relevant in power contexts, such as nature-related traits over cultural ones [

22,

37] (e.g., maternal, intuitive).

Women participants reaffirmed in low-agency beliefs also expressed a greater tendency, than those reaffirmed in high-agency beliefs, to identify with positive individualistic traits. Given the common national and cultural background of the sample, it seemed logical to expect no differential effect of manipulated factors on self-descriptions in terms of collectivism-individualism [

45]. However, the study design does not allow for conclusions beyond the obvious: when participants are reaffirmed in low-agency beliefs and thus made aware of the pressure of gender norms and stereotypes, they emphasize separation from others and traits of uniqueness.

How Do Threat to Personal Reputation and Affirmation in Agency Beliefs Interact?

To what extent can agency beliefs (i.e., Low-agency vs. High-agency) moderate the threat to a woman’s sexual reputation? If stereotype-threatening situations [

14] induce dissonance, can the effects of the threat to personal reputation be reduced by inducing beliefs that alter the balance between dissonant elements or ideas? [

26] (H5). The tendency of the participating women to describe themselves with positive traits in any of the dimensions was greater when the threat to their personal reputation was due to sexual activity (vs. sexual abstinence) only in the condition in which they were induced to write low-agency beliefs, but this difference was not found when participants reaffirmed their beliefs in favor of high-agency. Furthermore, women participant who affirmed low-agency beliefs, compared to the group that affirmed high-agency, showed a greater tendency to identify with positive traits of the dimensions corresponding to nature and culture, but this effect was only found in threat to reputation due to sexual activity condition, but not in the condition "threat to reputation due to sexual abstinence (H5).

Finally, we found an interaction effect between the manipulated factors on attitude in favor of establishing sexual consent (H5). Specifically, attitude toward sexual consent were more favorable when personal reputation was threatened due to sexual activity compared to abstinence, but only when participants were reaffirmed in low-agency beliefs. Similarly, attitudes toward sexual consent were more favorable when participants affirmed Low-agency beliefs (vs. High-agency beliefs) only if their personal reputation was threatened or devalued due to sexual activity.

Limitations and Perspectives

There is still work to be done to understand how women's self-concept and sexual attitudes may be influenced by the conflicting expectations stemming from the sexual double standard norm and the agency norm, which shape the normative gender context in many democratic Western societies.

The present study utilized a threat to personal reputation based on the assumed sexual profile of the female participants. Consequently, our findings do not address the effects that stereotype threat might have on women's gender self-concept. Nor have we addressed the effect of disregarding personal sexual reputation on the perception of women as a collective. Therefore, future research should explore how information regarding both agency and sexual activity of women under evaluation impacts society's (comprising both men and women) collective perception of women. Additionally, it is necessary to investigate to what extent the expectations derived from the sexual double standard norm and the agency norm influence women's awareness of stigma.

Some limitations of this research concern generalizability. The participants were mostly university students in their twenties, who generally have a different mindset compared to older adults, as the latter were socialized in a society with different gender values and norms. As a result, these findings may be limited to the population of university students. Further studies with more heterogeneous samples are needed, not only in terms of age but also by including non-heteronormative samples.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the influence of normative contexts related to sexual gender norms on young women's self-perceptions and on their attitude toward sexual consent. Our results indicate that normative contexts related to the Sexual Double Standard and the Sexual Agency Norm significantly shape both the valence and the nature of the attributes and characteristics that young women use to define themselves. Furthermore, the interaction between these two normative dimensions influences young women's attitudes toward sexual consent. Several conclusions can be drawn from our results.

First, the tendency to reinforce a positive self-image is stronger when threats to personal reputation arise from sexual activity or assertiveness than when they originate from a profile of sexual abstinence or shyness. That is, expectations derived from the traditional version of the sexual double standard that regulates the dominio of sexual freedom, rather than the version that regulates the dominio of sexual abstinence, seem to activate the need for positive self-presentation in young women.

Second, this inclination toward positive self-description is more pronounced among young women who reaffirm the belief that women's range of freedom is constrained by gender stereotypes, compared to those who reaffirm high-agency beliefs. Therefore, it seems that the sexual agency norm can hinder awareness or perception of the sociostructural and psychosocial barriers that continue to regulate gender roles.

Third, we found that norms derived from the sexual double standard and agency norms interact with each other. Specifically, when reputation is threatened by sexual activity, the tendency to describe oneself favorably is more pronounced than when reputation is devalued for being abstinent. However, this tendency to self-enhancement only occurs when young women reinforce the belief that their sexual activity does not depend on their dispositional characteristics, but is regulated by gender stereotypes and norms. This effect was observed specifically in the tendency to self-ascribe more positive than negative traits of the nature and culture domains. We found a similar interaction effect on favorable attitude toward sexual consent. Women participating in this study showed a more favorable attitude toward sexual consent when their reputation was devalued for being sexually assertive rather than abstinent, but this effect depended on the reinforcement of low-agency beliefs. Attitudes toward sexual consent were also found to be more favorable among participants who reported a belief in low-agency compared to those who reported a belief in high-agency, but only when their reputation was undermined due to sexual activity.

Fourth, the results regarding the interaction between SDS-derived norms and the sexual agency norm seem to indicate that if a young woman's sexual reputation is devalued for being assertive, she needs to be aware of the ongoing psychosocial asymmetry in relation to gender in order to deploy strategies that safeguard their self-concept, as well as to maintain a consistent and favorable attitude towards sexual consent.

The importance of these findings lies in their potential to inform interventions aimed at addressing the identity conflicts and inconsistent sexual attitudes that young women may experience in the complex normative contexts that characterize Western societies today. We hope that in future research we can deepen our understanding of these processes. We believe that this line of research may be useful for designing psychosocial intervention strategies capable of reinforcing a positive self-concept in women, as well as a consistent, non-ambivalent attitude towards situations that require sexual consent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G-B..; methodology, A.R.H.M; C.G-B., and M.M.S.F; software, CG-B., M.M.S.F and A.R.H.M.; validation, C.G-B., A.R.H.M; M.M.S.F., and N.M.; formal analysis, C.G-B., A.R.H.M and M.M.S.F; investigation, C.G-B., A.R.H.M and M.M.S.F; resources, C.G-B., A.R.H.M., and M.M.S.F., and N.M; data curation, A.R.H.M; C.G-B. and M.M.S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G-B., A.R.H.M., and M.M.S.F.; writing—review and editing, C.G-B., A.R.H.M; M.M.S.F., and N.M.; visualization, C.G-B., A.R.H.M. and M.M.S.F.; supervision, C.G-B.; A.R.H.M., and M.M.S.F.; project administration, C.G-B.; funding acquisition, C.G-B. and M.M.S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.