Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Review of Euler-Bernoulli Beam Theory and Its Applications

2.1. The Euler-Bernoulli Beam Theory

2.2. Application in Global Longitudinal Strength Estimation of Ships

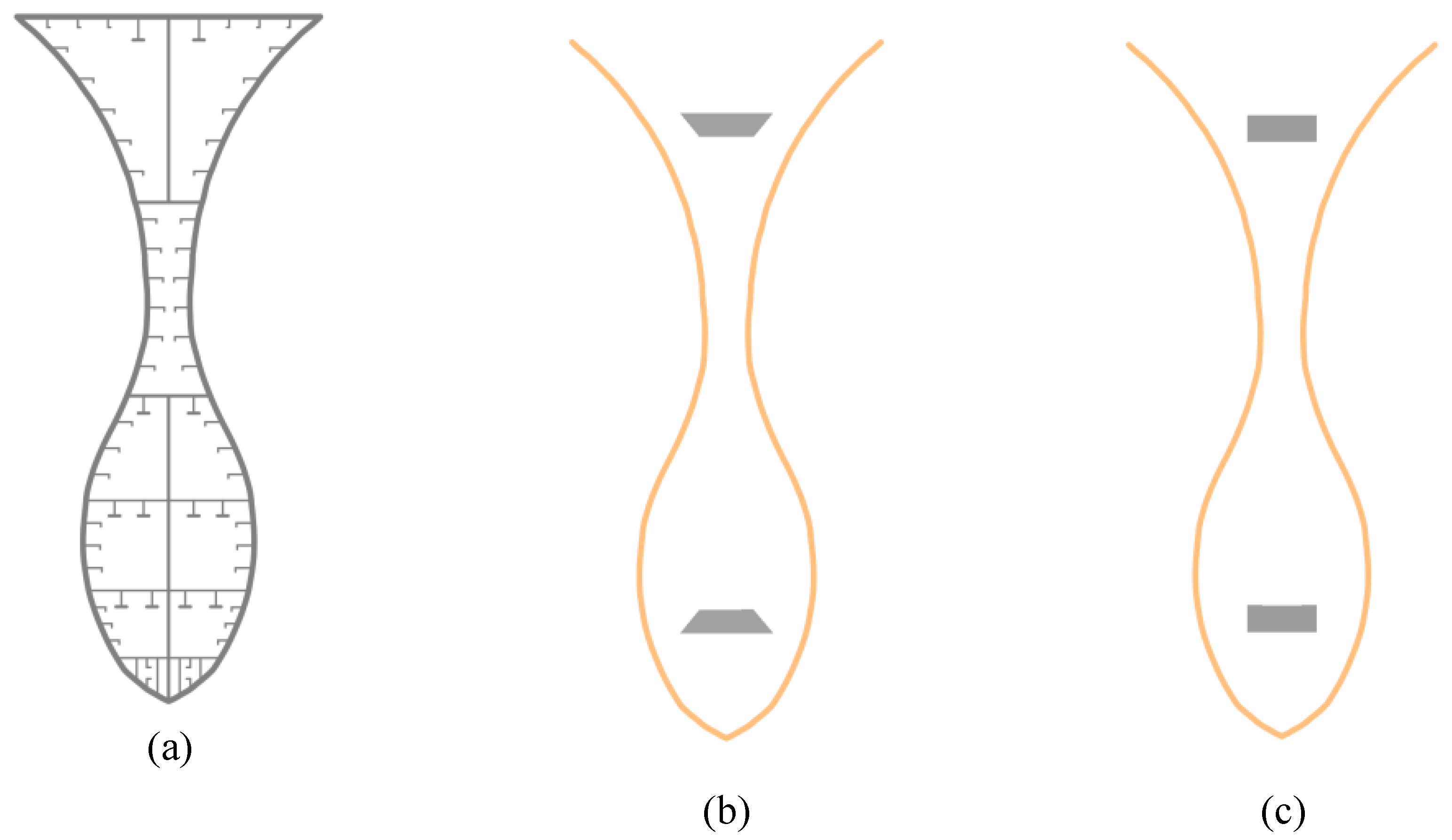

2.3. Application in Design of Scaled Hydroelastic Ship Models

3. A Novel Hull Girder Design Methodology

3.1. Design of the Sub-Cross-Sections of Ship Hull Girder Components

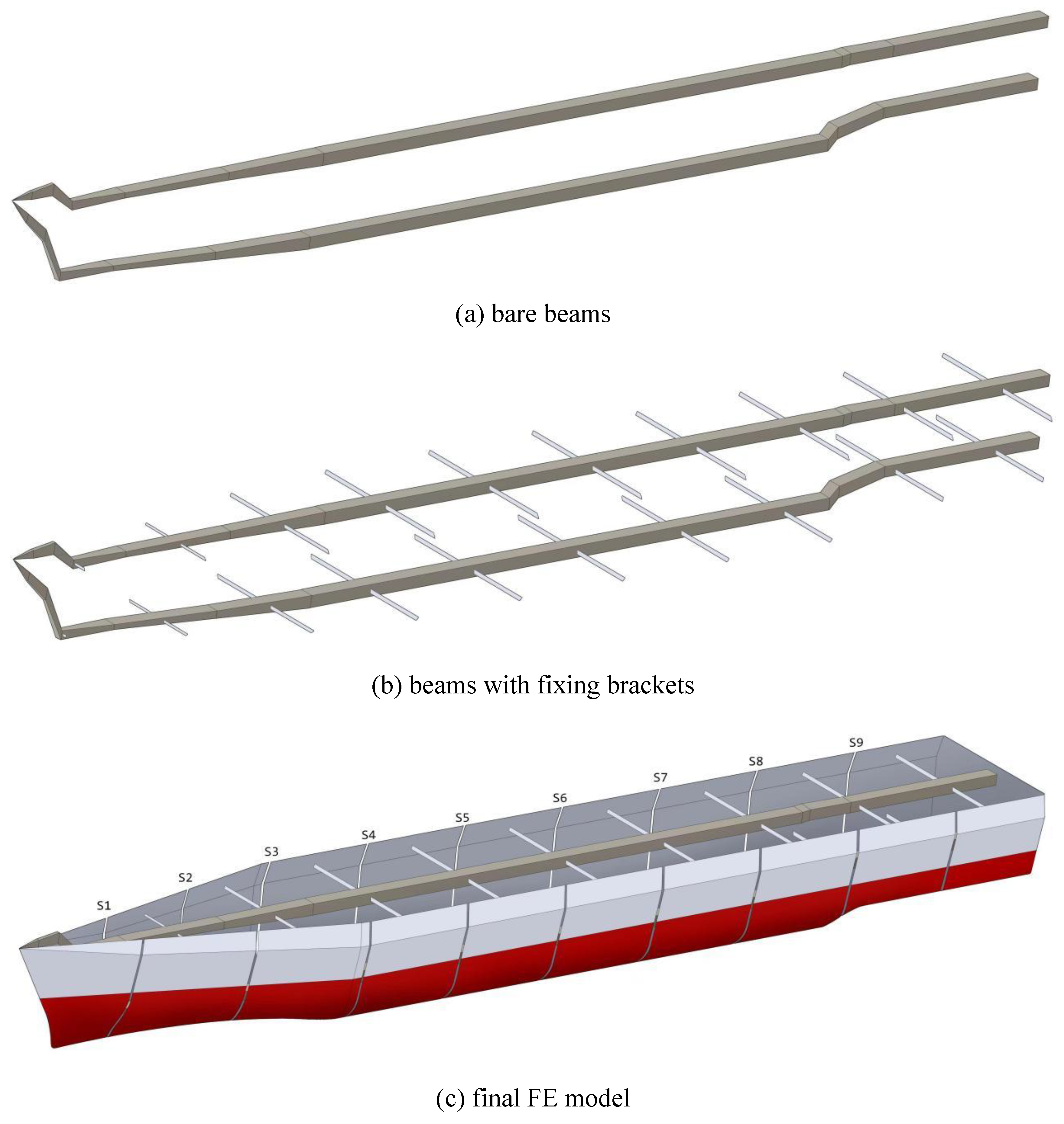

3.2. Formulation of a Calculable Ship Hull Girder FE Model

4. A Upgrade to the Classical Structural Strength Estimation Method

5. Verification of the Proposed Beam Cross-Section Design Method

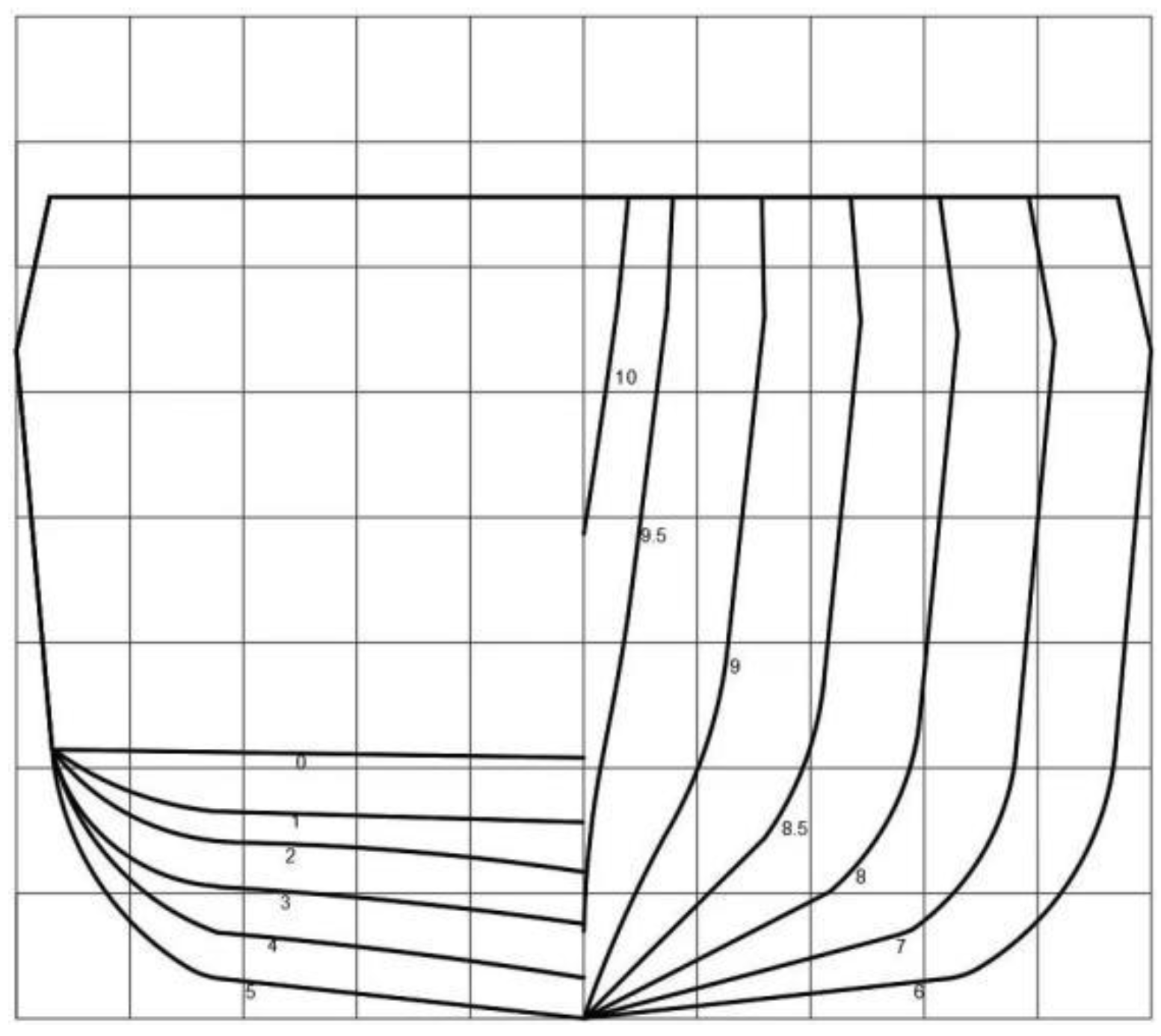

6. Application of the Proposed Method to a Real Ship

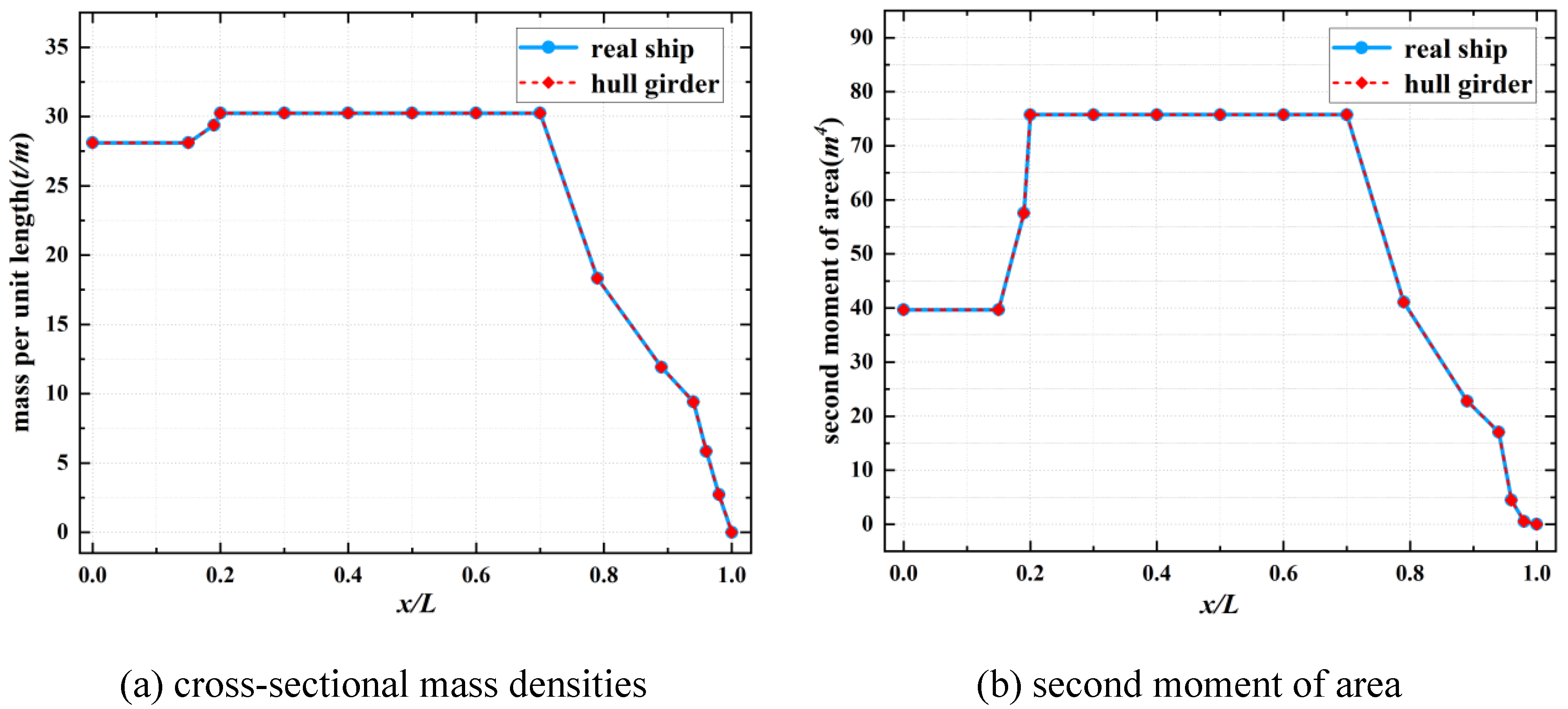

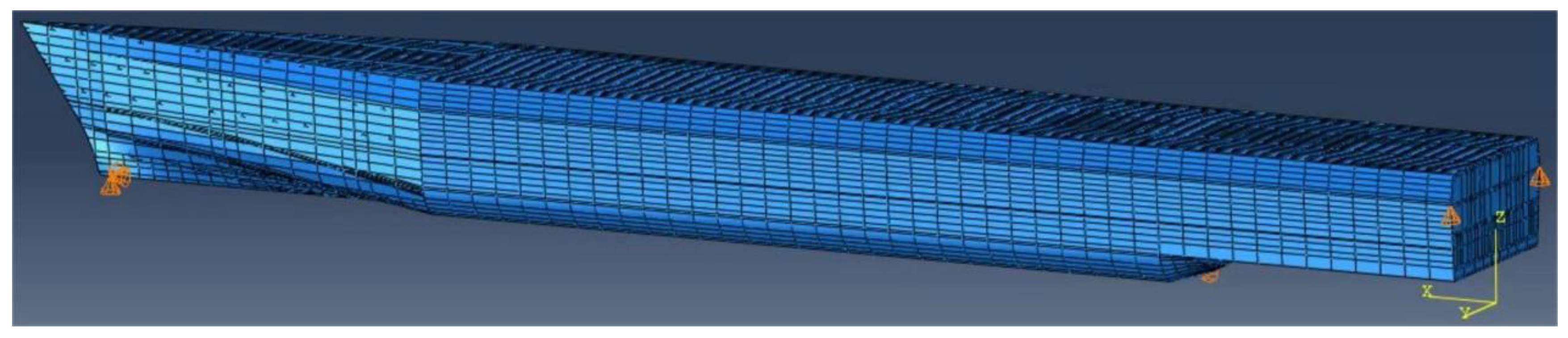

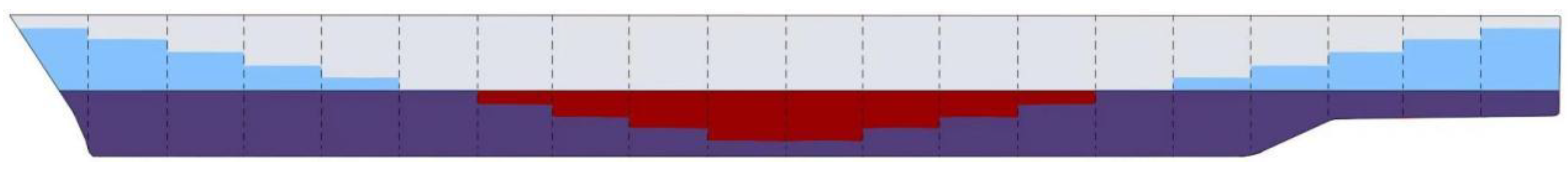

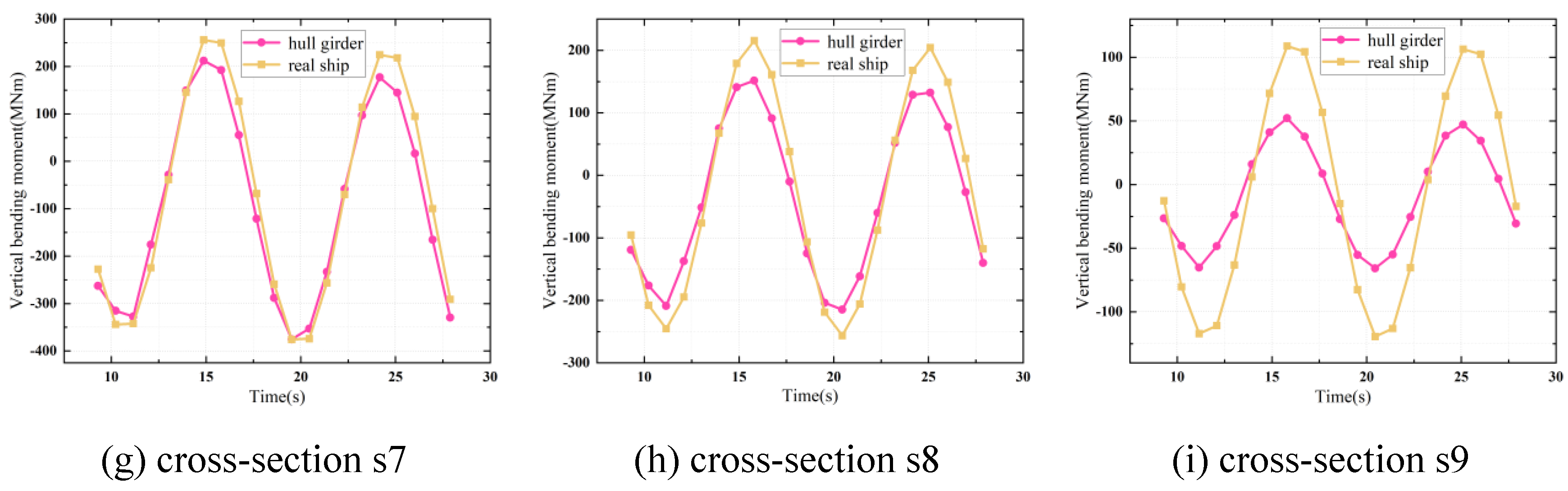

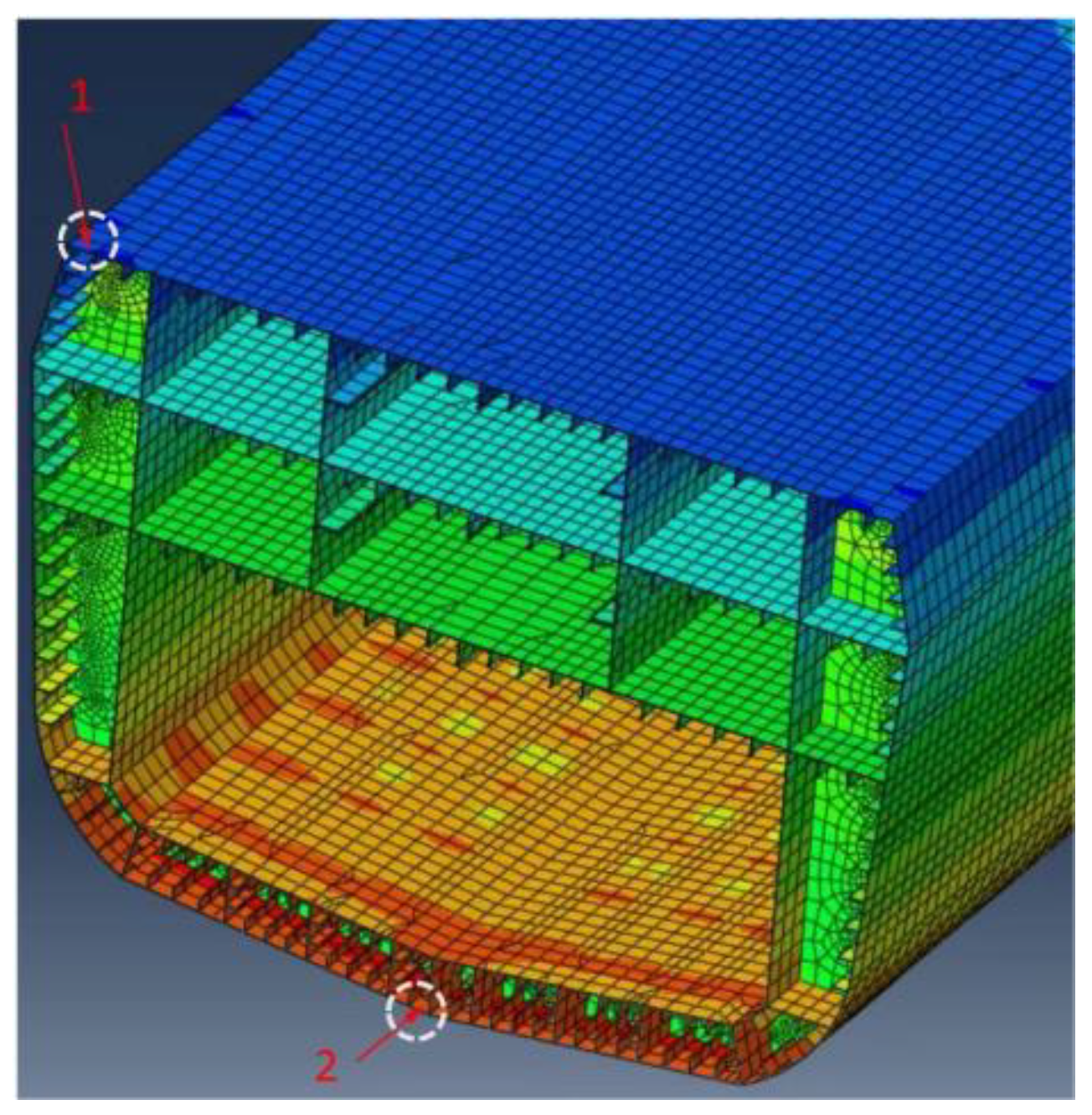

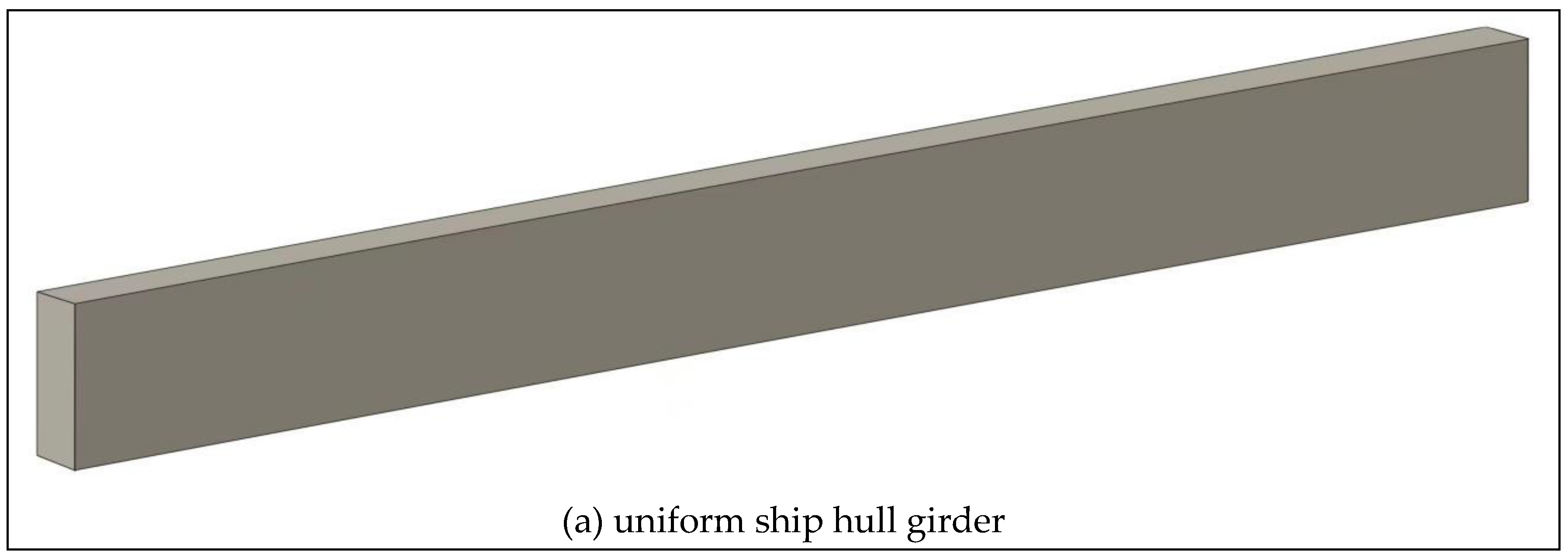

6.1. Formulation of the Full-Scale Ship Hull Girder System

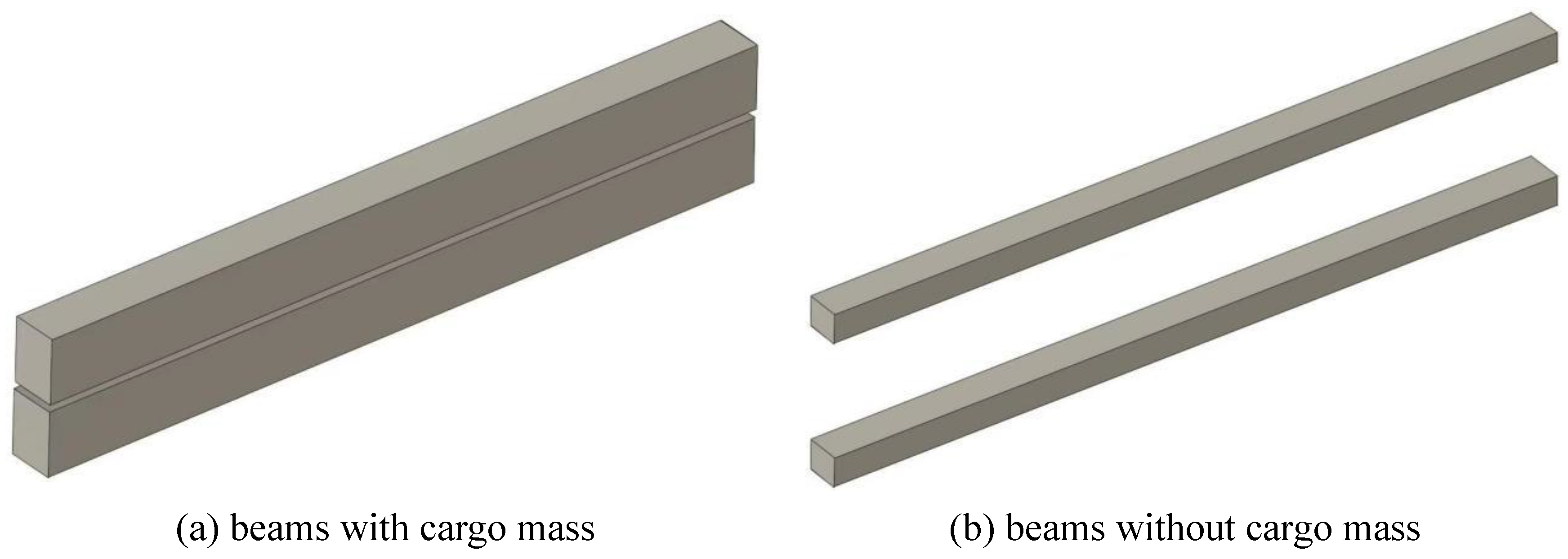

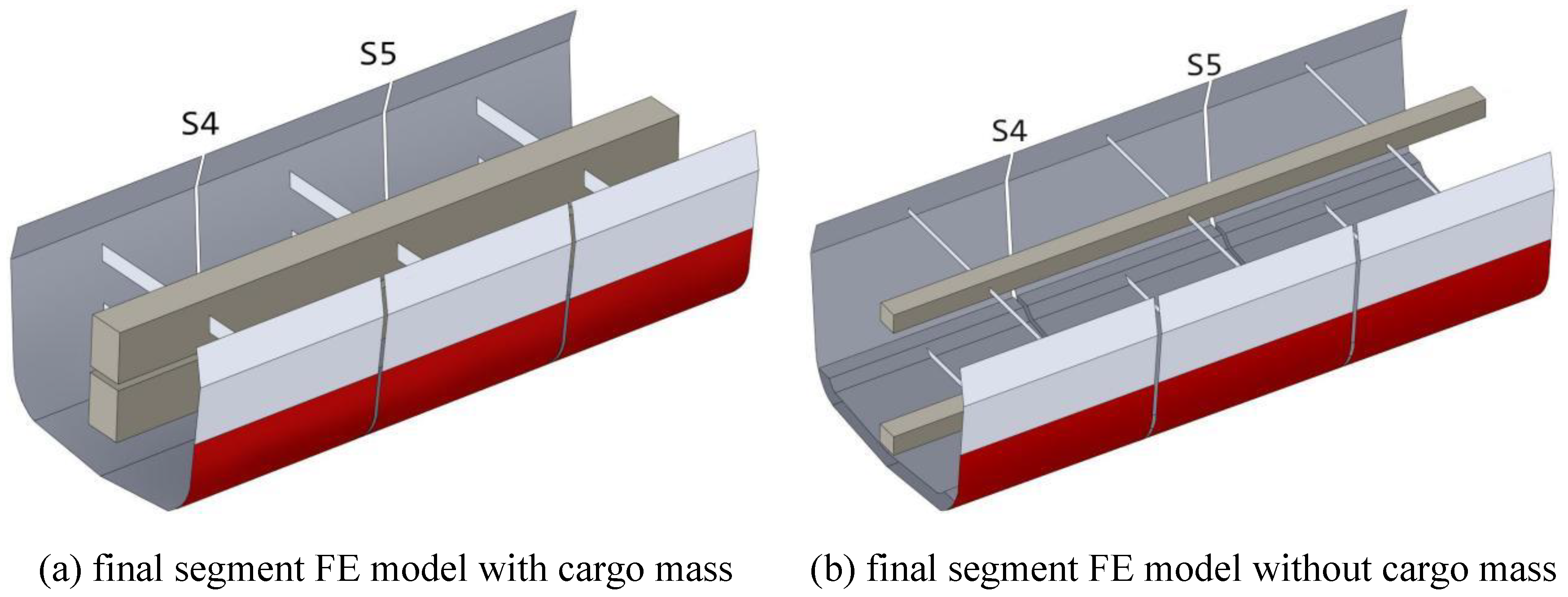

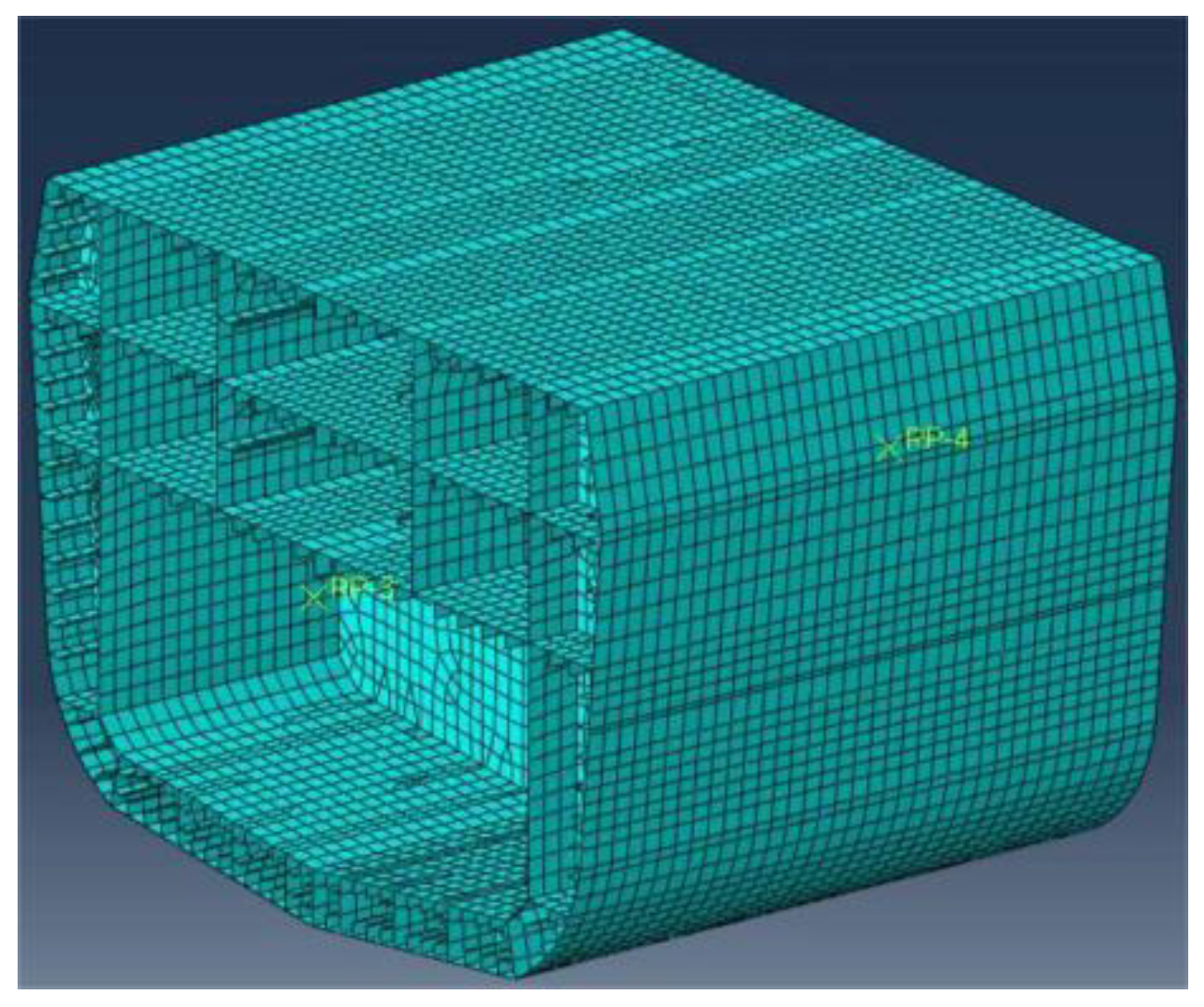

6.2. Analysis on Effects of Cargo Modeling Methods

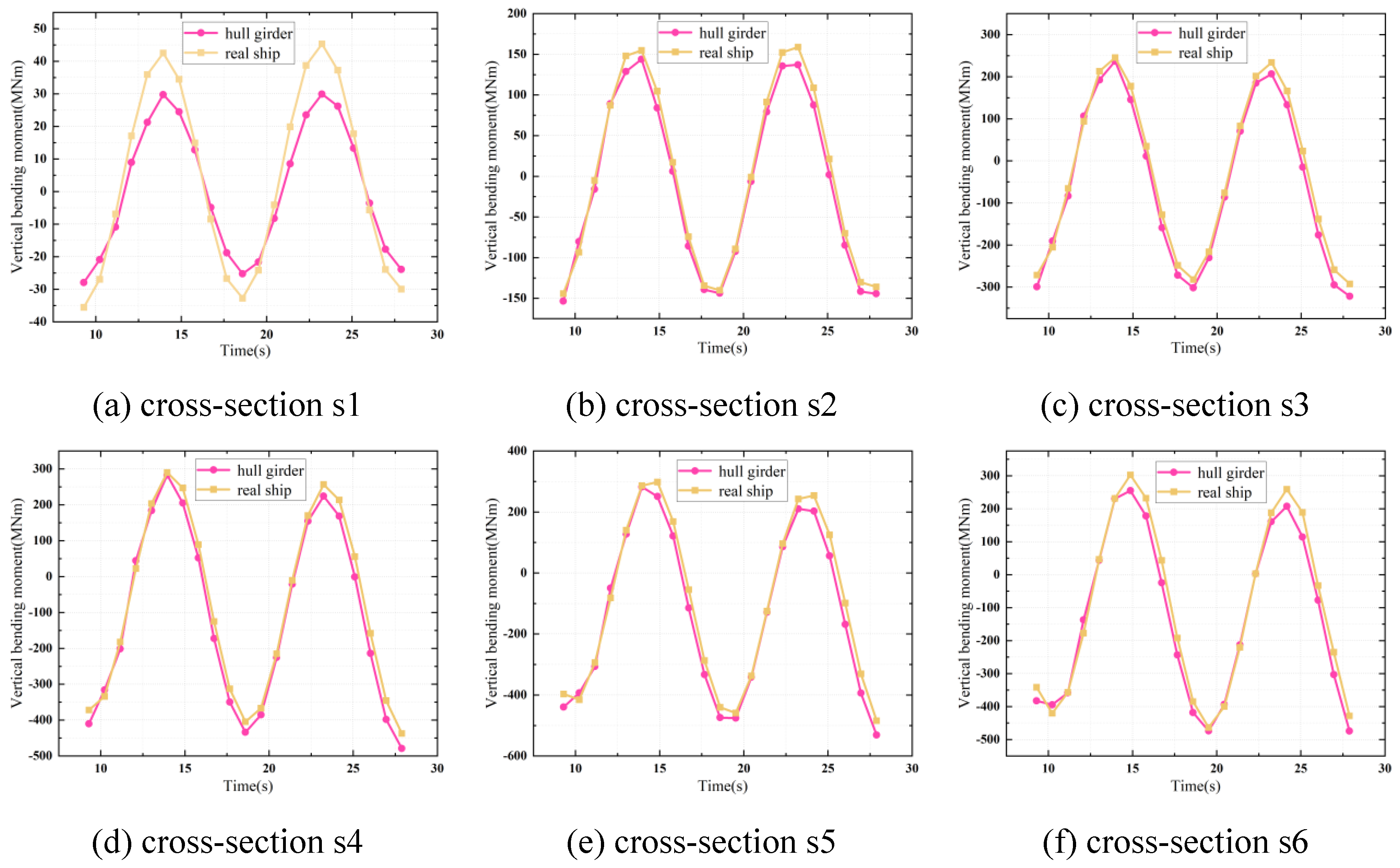

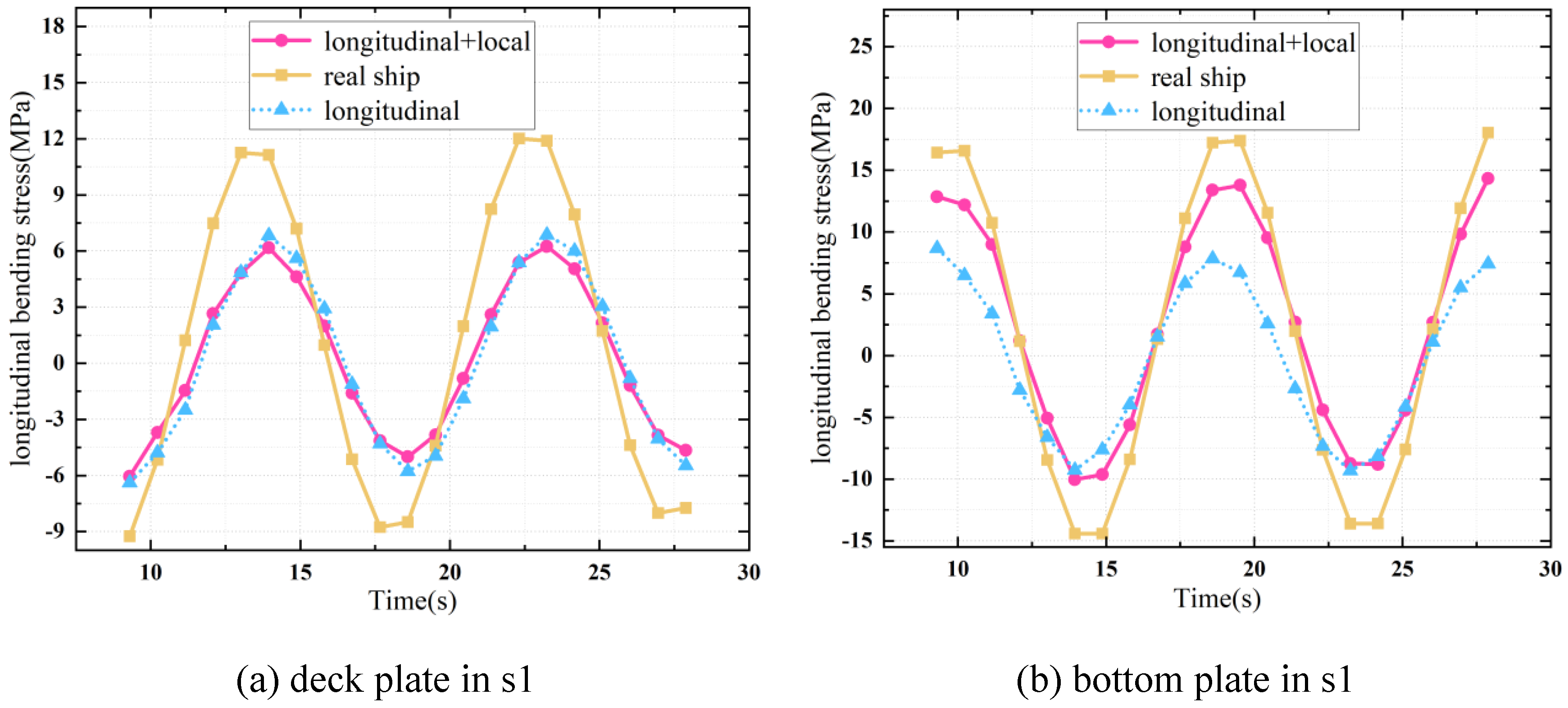

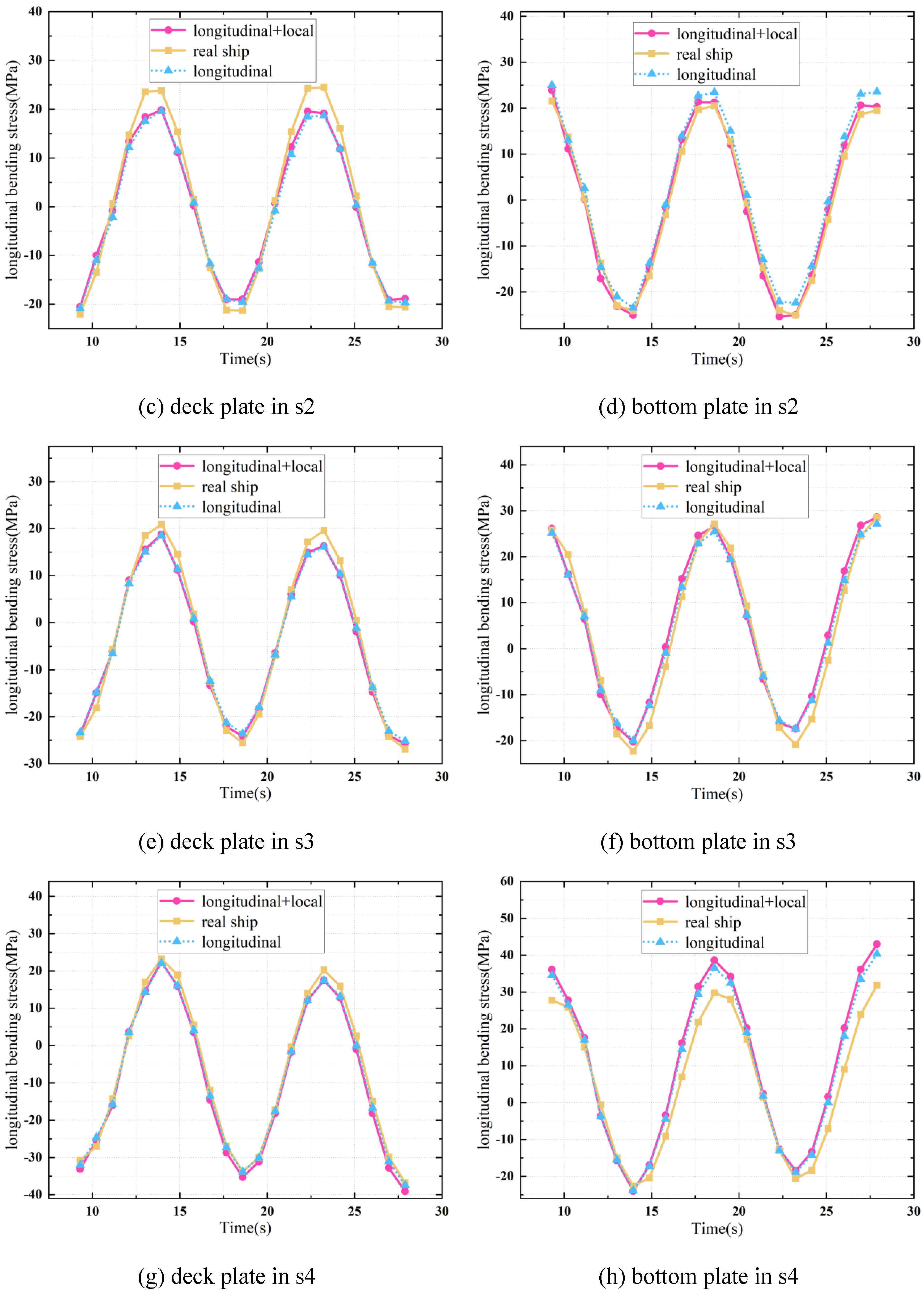

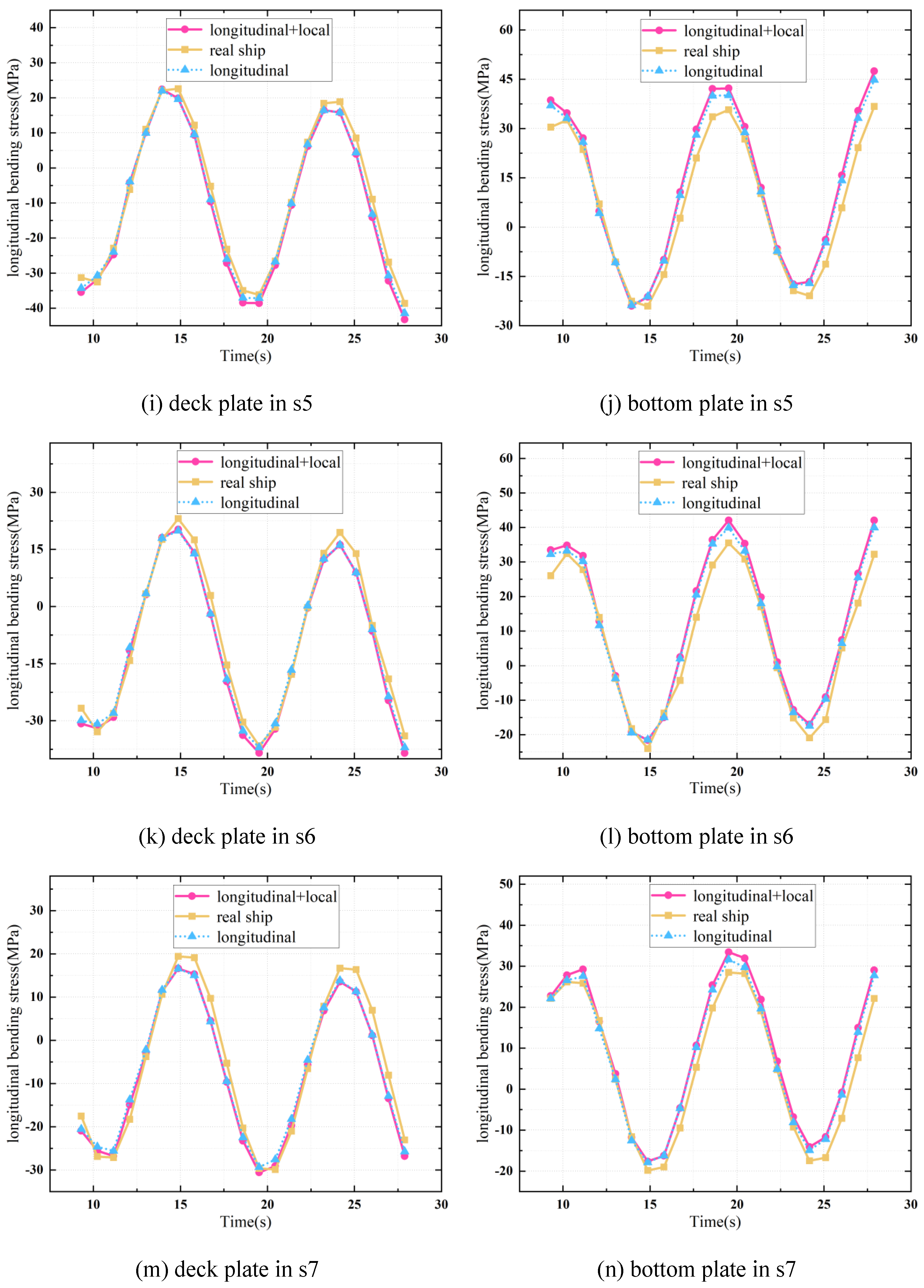

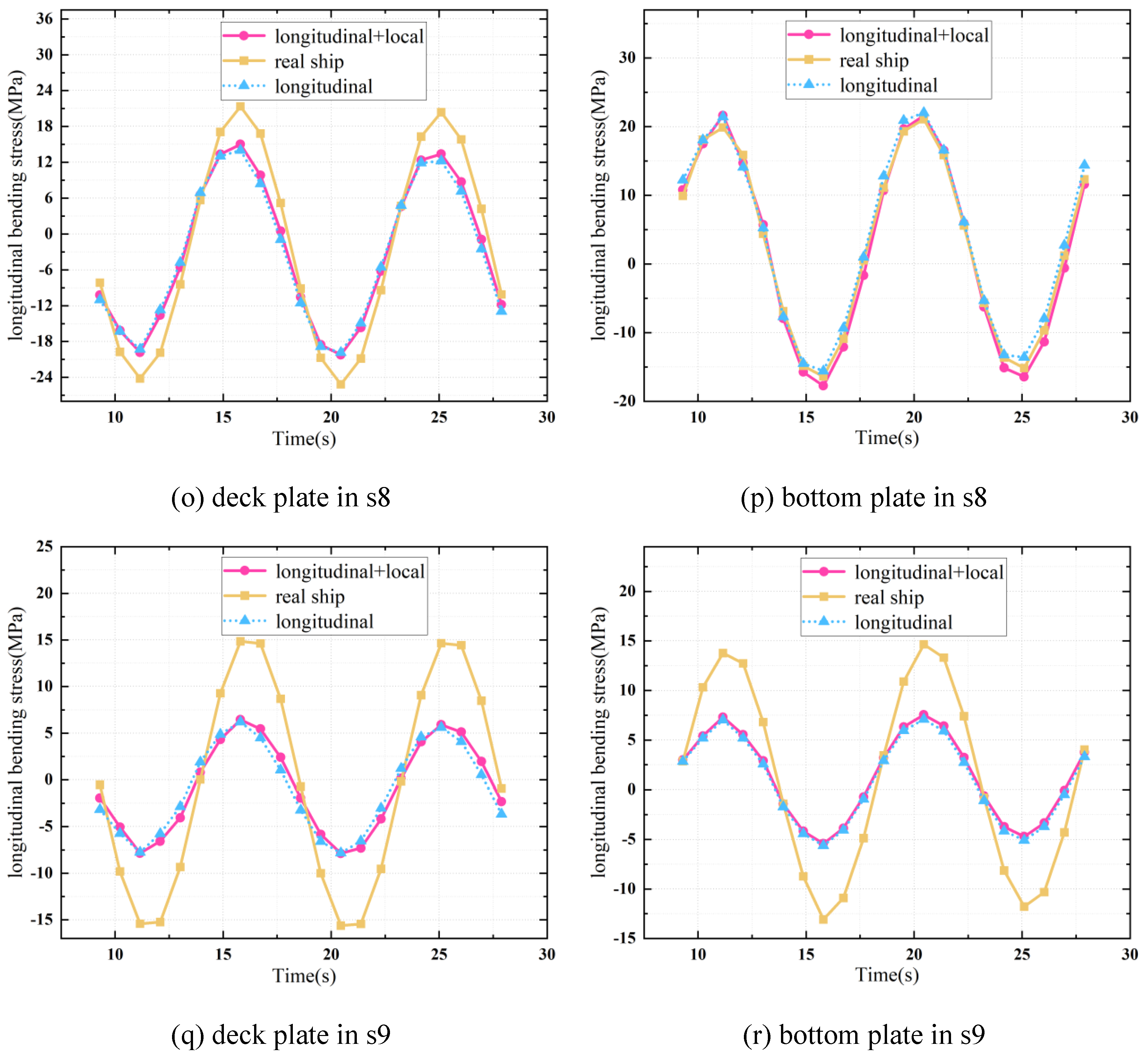

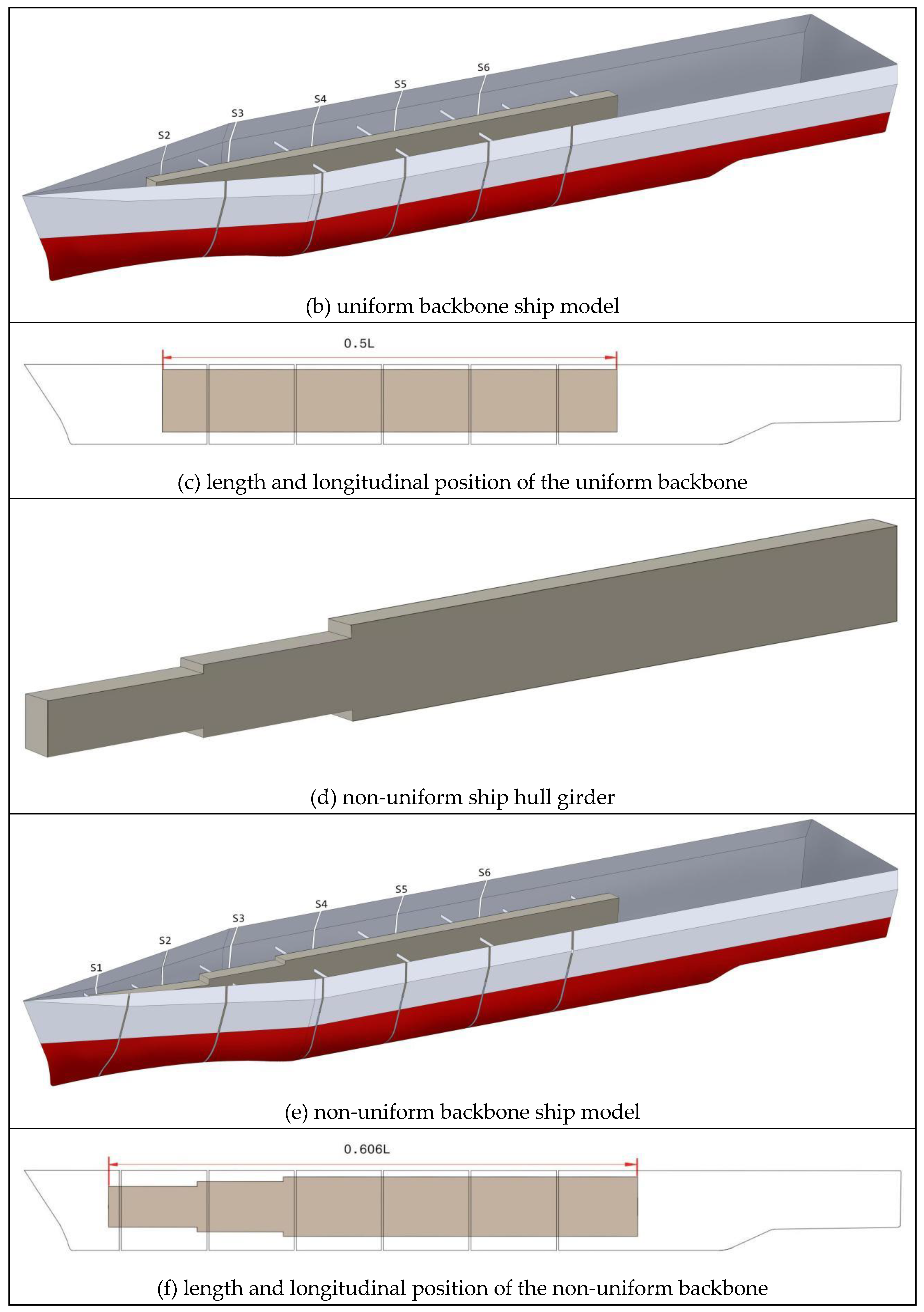

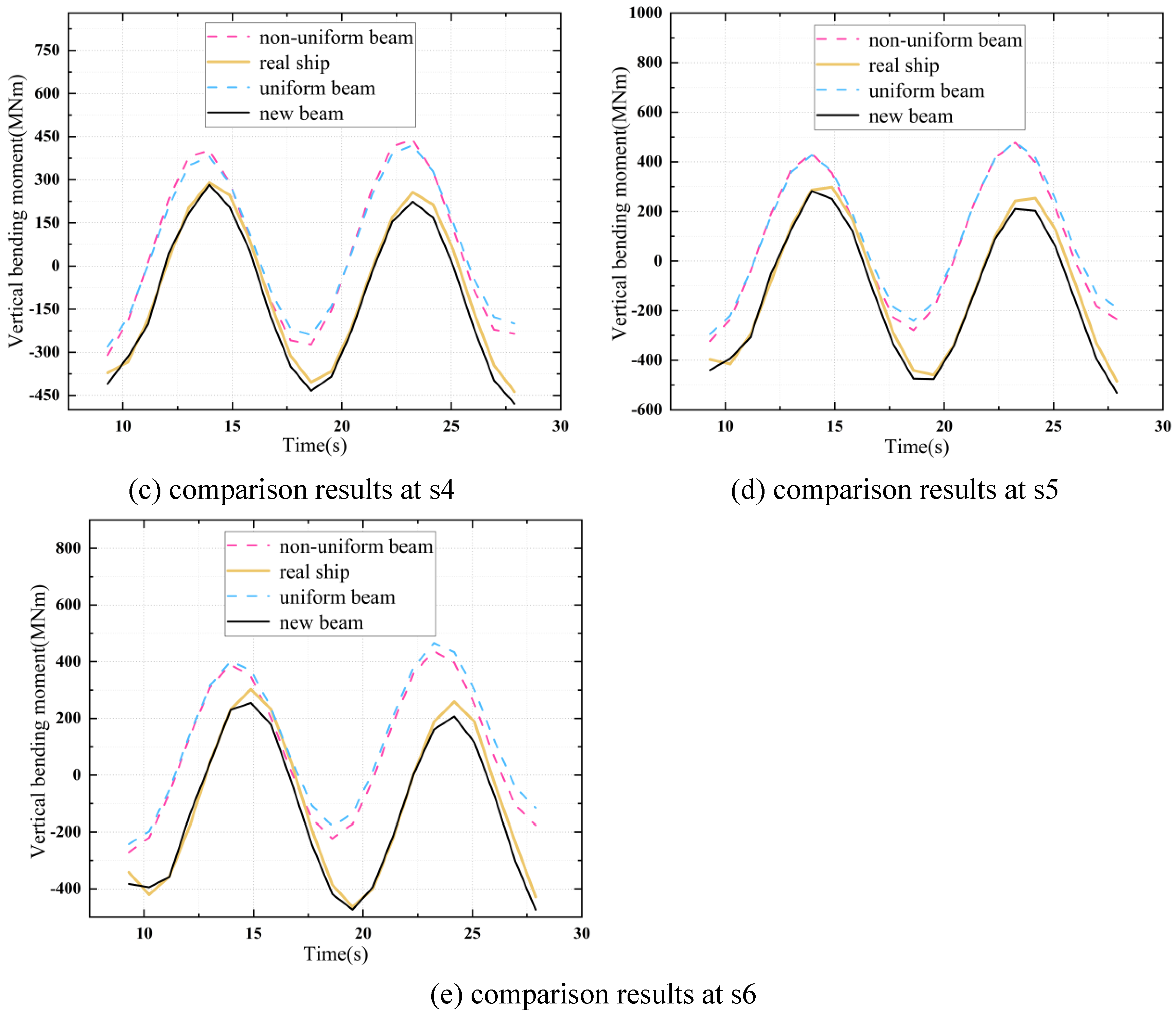

6.3. Comparison of Structural Responses

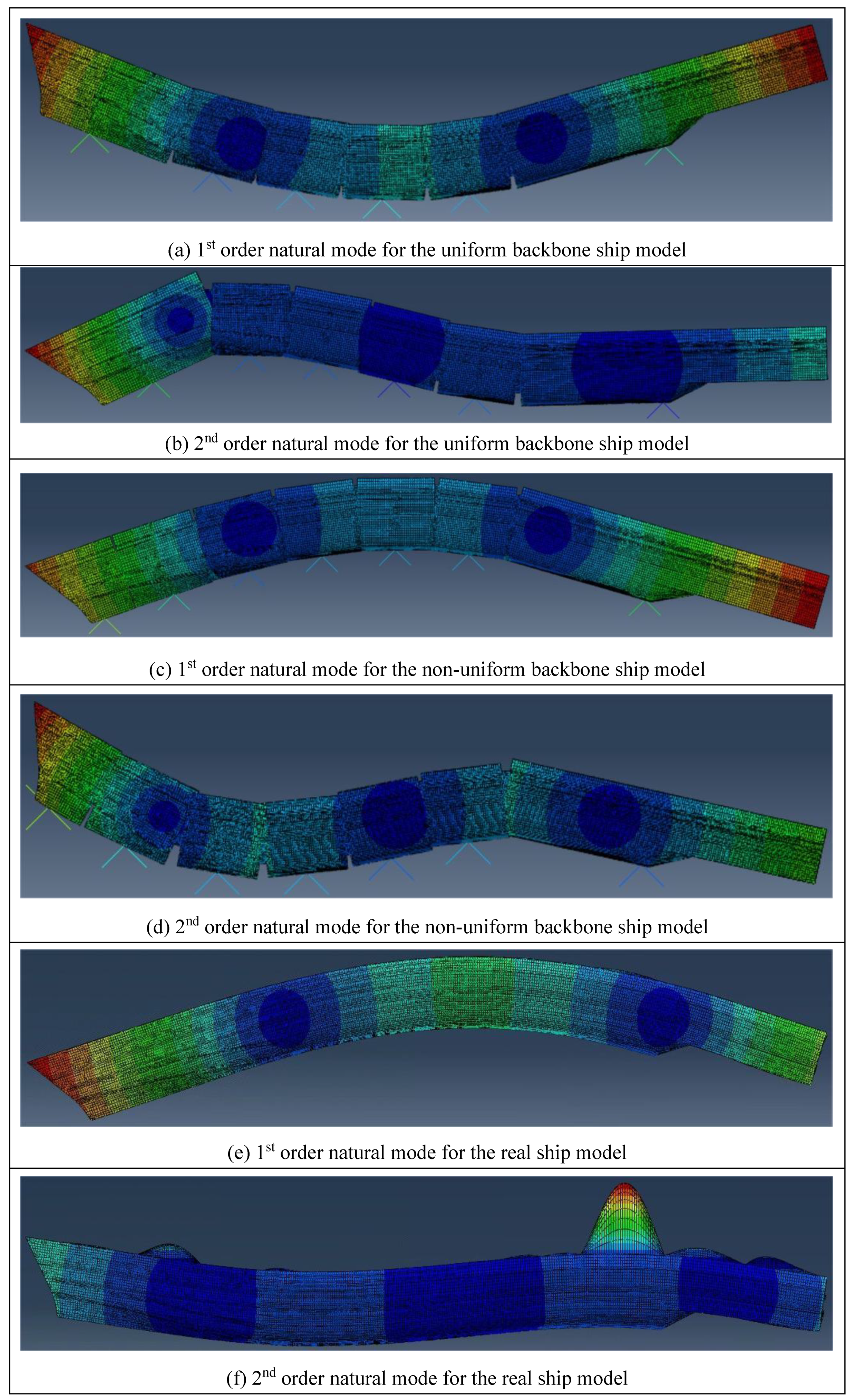

7. Comparison of the Proposed Method and Current Popular Method

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Q.; Wen, L.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X. Springing loads analysis of large-scale container ships in regular waves. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, P.; Chang, X.; Fan, G.; He, G. Research on the bow-flared slamming load identification method of a large container ship. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Paik, J.K. Ultimate strength characteristics of as-built ultra-large containership hull structures under combined vertical bending and torsion. Ships Offshore Struct. 2021, 15, S143–S160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, Y. Fatigue damage estimation of icebreaker ARAON colliding with level ice. Ocean Eng. 2022, 257, 111707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L.; Guo, C.; Wang, C. Experimental research on propeller-ice contact process and prediction of extreme ice load. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, W. Research on ship-ice collision model and ship-bow fatigue failure mechanism based on elastic-plastic ice constitutive relation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. , Wu, J. and Li, J., Design of ship structures, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, Shanghai, China, 2011[in Chinese].

- Chen, T. and Chen, B., Ship structural mechanics, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, Shanghai, China, 1991[in Chinese].

- Han, S.M.; Benaroya, H.; Wei, T. DYNAMICS OF TRANSVERSELY VIBRATING BEAMS USING FOUR ENGINEERING THEORIES. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 225, 935–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elishakoff, I. Who developed the so-called Timoshenko beam theory? Math. Mech. Solids 2019, 25, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, M.A.; Elkhodary, K.I.; Liu, W.K.; Belytschko, T.; Moran, B. Nonlinear Finite Elements for Continua and Structures, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.D. , Malkus, D.S., Plesha, M.E. and Witt, R.J., Concepts and applications of finite element analysis, 4th Edition, Wiley, 2001.

- Bathe, K.J. , Finite element procedures, 2nd Edition, Pearson Education, 2016.

- American Bureau of Shipping, Part 3: Hull construction and equipment, Rules for building and classing marine vessels, 2024.

- Lloyd’s Register, Common structural rules for bulk carriers and oil tankers, 2024.

- Bureau Veritas, Part B: Hull and stability, Rules for the classification of steel ships, 2024.

- Det Norske Veritas AS, Hull structural design: Ships with length 100 metres and above, Rules for classification of ships, 2016.

- China Classification Society, Chapter 5: Hull girder strength, Rules for structures of container ships, 2022.

- Zhao, W.; Leira, B.J.; Høyland, K.V.; Kim, E.; Feng, G.; Ren, H. A Framework for Structural Analysis of Icebreakers during Ramming of First-Year Ice Ridges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, W.; Bu, S.; Zhang, P. Asymmetric water entry of a wedged grillage structure investigated by CFD-FEM co-simulation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Huang, S.; Tezdogan, T.; Terziev, M.; Soares, C.G. Slamming and green water loads on a ship sailing in regular waves predicted by a coupled CFD–FEA approach. Ocean Eng. 2021, 241, 110107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y. , Shen, J. and Song, J. Ship wave loads, National Defense Industry Press, China, 2007[in Chinese].

- Hu, Y.; Ren, B.; Ni, K.; Li, S. Meshfree simulations of large scale ductile fracture of stiffened ship hull plates during ship stranding. Meccanica 2020, 55, 833–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.K. , Li, S. and Belytschko, T., Moving least square reproducing kernel method. (I) Methodology and convergence, Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 143, 1997, 113-154.

- Liu, W.K.; Jun, S.; Li, S.; Adee, J.; Belytschko, T. Reproducing kernel particle methods for structural dynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1995, 38, 1655–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Hu, Y.; Feng, G.; Li, C. Experimental and numerical study on the penetration of the inclined stiffened plate. Ocean Eng. 2022, 258, 111792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Yang, Z.; Xia, W.; Oterkus, S.; Oterkus, E. Buckling analysis of cracked plates using peridynamics. Ocean Eng. 2020, 214, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Oterkus, S. Investigating the effect of brittle crack propagation on the strength of ship structures by using peridynamics. Ocean Eng. 2020, 209, 107472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Oterkus, S. Peridynamics for the thermomechanical behavior of shell structures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2019, 219, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, S. Ultimate longitudinal strength of midship cross-section. Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering 1984, 22, 200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y. and Wang, C.M., Structural vibration: exact solutions for strings, membranes, beams and plates, CRC Press, 2013.

- Yao, X. , Ship hull vibration, Harbin Engineering University Press, 2004[in Chinese].

- Ramos, J.; Incecik, A.; Soares, C. Experimental study of slam-induced stresses in a containership. Mar. Struct. 2000, 13, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storhaug, G. , Choi, B.K., Moan, T. and Hermundstad, O.A., Consequences of whipping and springing on fatigue for a 8600TEU container vessel in different trades based on model tests, 11th International Symposium on Practical Design of Ships and Other Floating Structures, 2, PRADS 2010, 1180-1189.

- Zhu, S.; Wu, M.; Moan, T. Experimental investigation of hull girder vibrations of a flexible backbone model in bending and torsion. Appl. Ocean Res. 2011, 33, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Moan, T. Nonlinear effects from wave-induced maximum vertical bending moment on a flexible ultra-large containership model in severe head and oblique seas. Mar. Struct. 2014, 35, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kim, B.W.; Hong, S.Y. Experimental investigations on extreme bow-flare slamming loads of 10,000-TEU containership. Ocean Eng. 2018, 171, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Deng, B.; Ren, H.; Sun, S. Investigation on the nonlinear effects of the vertical motions and vertical bending moment for a wave-piercing tumblehome vessel based on a hydro-elastic segmented model test. Mar. Struct. 2020, 72, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Sun, S.-L.; Yang, R.-S.; Ren, H.-L.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, J.-L. Nonlinear bending moments of an ultra large container ship in extreme waves based on a segmented model test. Ocean Eng. 2021, 243, 110335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zou, J.; Deng, B.; Liu, R.; Sun, S. Experimental study of stern slamming and global response of a large cruise ship in regular waves. Mar. Struct. 2022, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguen, J.F. and Frechou, D., Large scale seakeeping experiments in the new, large towing tank B600, In: 10th International Symposium on Practical Design of Ships and other Floating Structures, 2, 2007, 790-798.

- Jiao, J.; Ren, H.; Soares, C.G. Vertical and horizontal bending moments on the hydroelastic response of a large-scale segmented model in a seaway. Mar. Struct. 2021, 79, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Large scale model experimental study on wave load of ultra-large container ships, Master Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, 2019[in Chinese].

- China Classification Society, Chapter 9: Rules for classification of sea-going steel ships, 2024.

- Rajendran, S.; Fonseca, N.; Soares, C.G. A numerical investigation of the flexible vertical response of an ultra large containership in high seas compared with experiments. Ocean Eng. 2016, 122, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, T.; Shimada, K. Time-domain strip method with memory-effect function considering the body nonlinearity of ships in large waves. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2006, 11, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F. , Time domain prediction of hydroelasticity of floating bodies, Applied Ocean Research, 51, 2015, 1-13.

- Dong, Y. Ship wave loads and hydroelasticity, Tianjin University Press, China, 1991[in Chinese].

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Density ρ(kg/m3) | 7800 |

| Area A(m2) | 2.304 |

| Height of COG ZG(m) | 9.016 |

| Second moment of area IZG(m4) | 85.461 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Length of the upper parallel side WΩu(m) | 2.400 |

| Length of the lower parallel side WΩl(m) | 1.400 |

| Length of the upper parallel side WBu(m) | 1.400 |

| Length of the lower parallel side WBl(m) | 2.400 |

| Heights dΩl-dΩu, dBu-dBl(m) | 0.606 |

| Vertical distances TΩ, TB(m) | 6.088 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Length wU(m) | 1.800 |

| Length hU(m) | 0.640 |

| Length wD(m) | 1.800 |

| Length hD(m) | 0.640 |

| Vertical distances dU, dD(m) | 6.023 |

| Items | Value |

|---|---|

| Length overall Loa(m) Breadth B(m) Depth D(m) Design draft T(m) Displacement Δ(t) Block coefficient CB(m) |

135.00 17.00 12.30 6.00 8642.56 0.66 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density ρ(kg/m3) | 7800 |

| Young’s modulus E(GPa) | 2.11 |

| Poisson’s ratio μ | 0.3 |

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Length wU(m) | 2.500 |

| Length hU(m) | 3.377 |

| Length wD(m) | 2.500 |

| Length hD(m) | 3.377 |

| Vertical distances dU, dD(m) | 1.881 |

| Cross-section ID | First model(peak values) | Second model(peak values) | Relative error | Relative error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBM(MNm) | VSF(kN) | VBM(MNm) | VSF(kN) | VBM | VSF | |

| s4 | -182.7 | -1360.0 | -155.7 | -3000.0 | 17.3% | -54.7% |

| s5 | -200.0 | 698.0 | -172.9 | 1960.0 | 15.7% | -64.4% |

| item | real ship | uniform girder model | non-uniform girder model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | relative error | value | relative error | |||

| natural frequency(Hz) | 1st | 0.74 | 0.71 | 4.1% | 0.72 | 2.7% |

| 2nd | 1.53 | 1.57 | 2.6% | 1.63 | 6.5% | |

| COG(m) | vertical | 6.68 | 6.56 | 1.8% | 6.40 | 4.2% |

| longitudinal | 60.76 | 60.76 | 0.0% | 60.76 | 0.0% | |

| moment of inertia(t×mm2;×1012) | 4.71 | 4.57 | 3.0% | 4.77 | 1.3% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).