Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of PS/CNT Composites

2.1. Structure of Polystyrene (PS)

2.2. Properties of Carbon Nanotubes (CNT)

2.3. Interaction Mechanisms between Polystyrene (PS) and Carbon Nanotubes (CNT)

2.3.1. Van der Waals Forces

2.3.2. π-π. Stacking Interactions

2.3.3. Covalent Bonding

2.3.4. Dispersion and Entanglement

2.3.5. Interfacial Polarization

3. PS/CNT Composite Preparation Methods

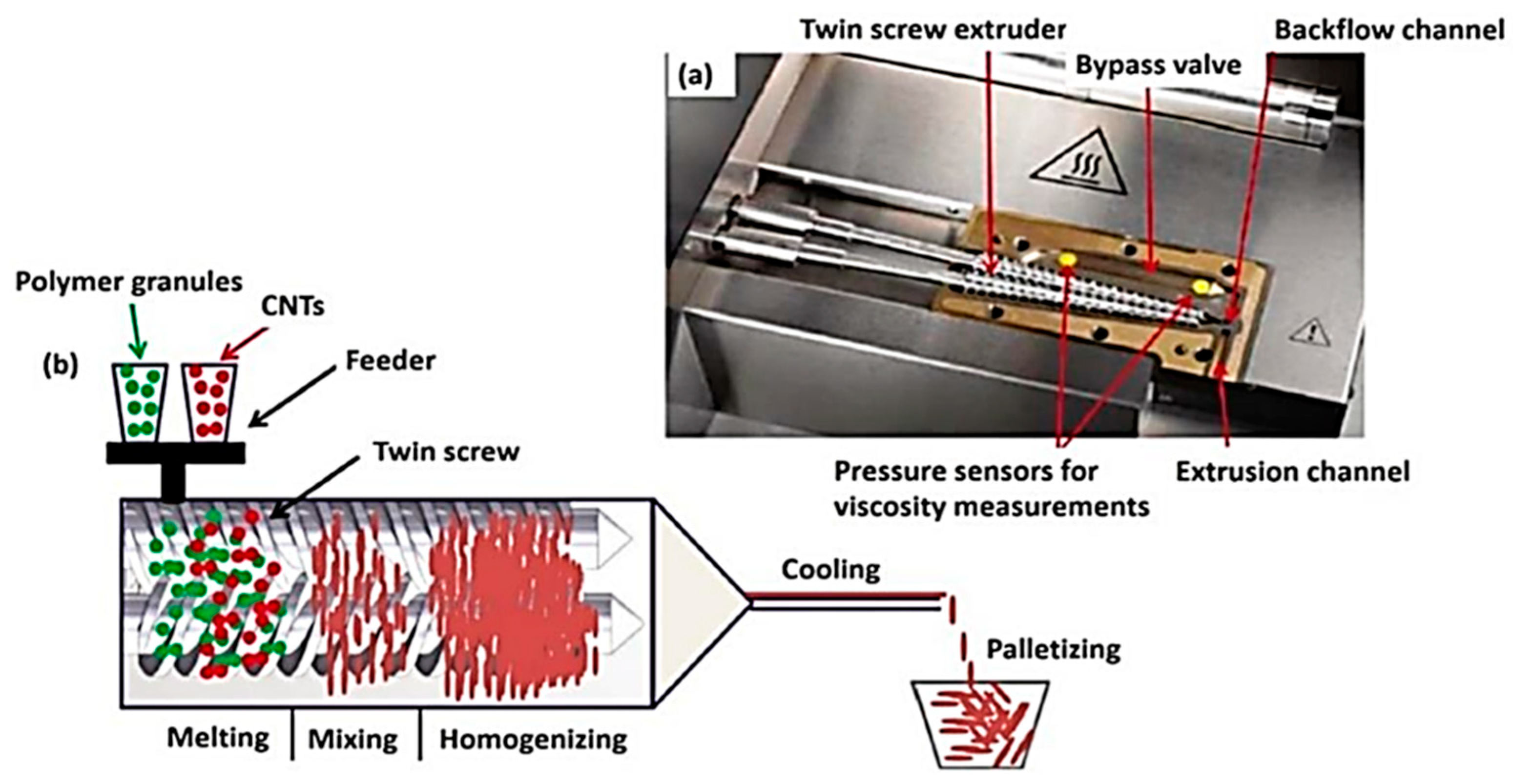

3.1. Melt Mixing

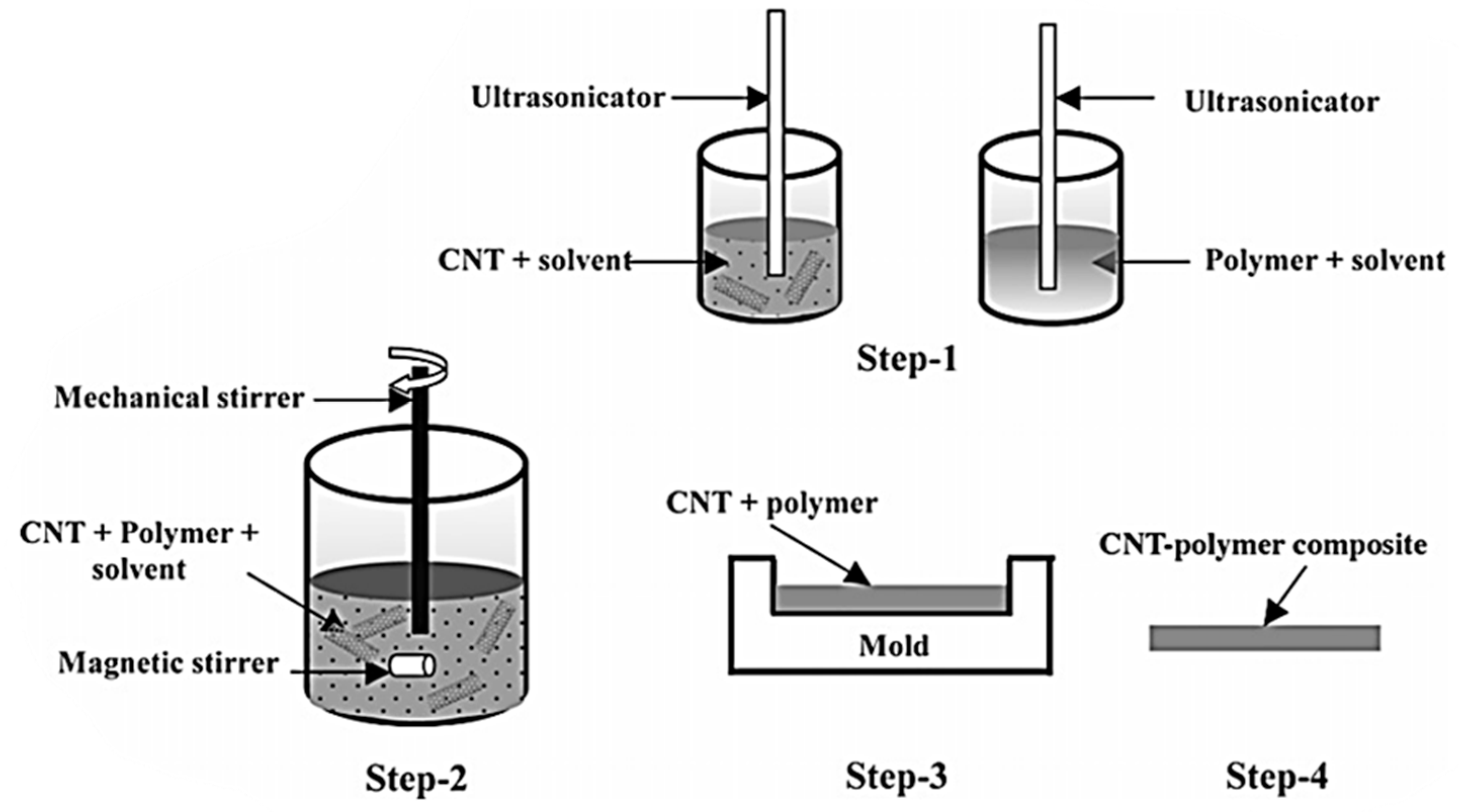

3.2. Solution Mixing

3.3. In-Situ Polymerization

3.4. Wet Spinning

3.5. Spray Drying

3.6. Electrospinning

3.7. Self-Assembly Techniques

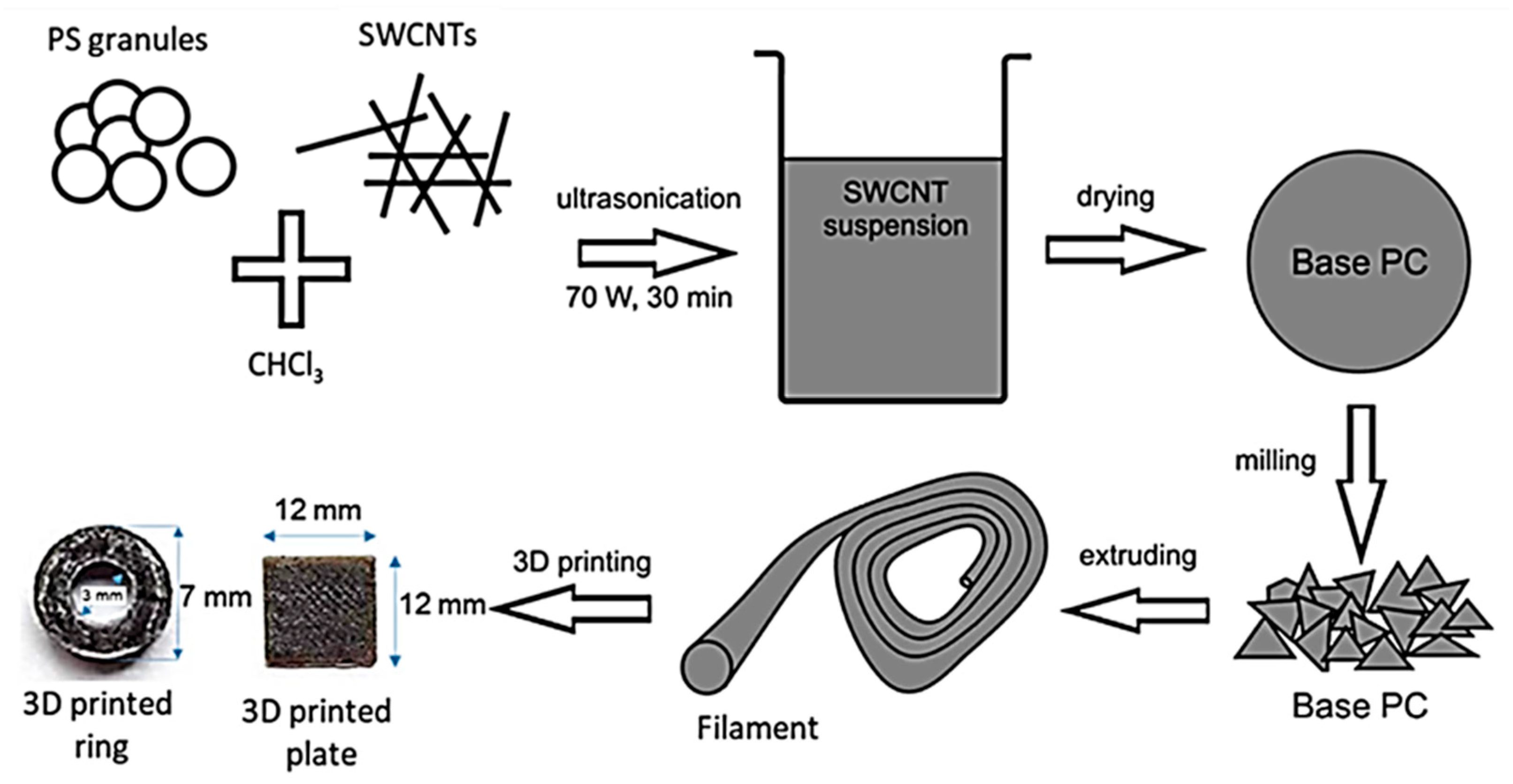

3.8.3. D Printing (Additive Manufacturing)

3.9. Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly

3.10. Co-Solvent Method

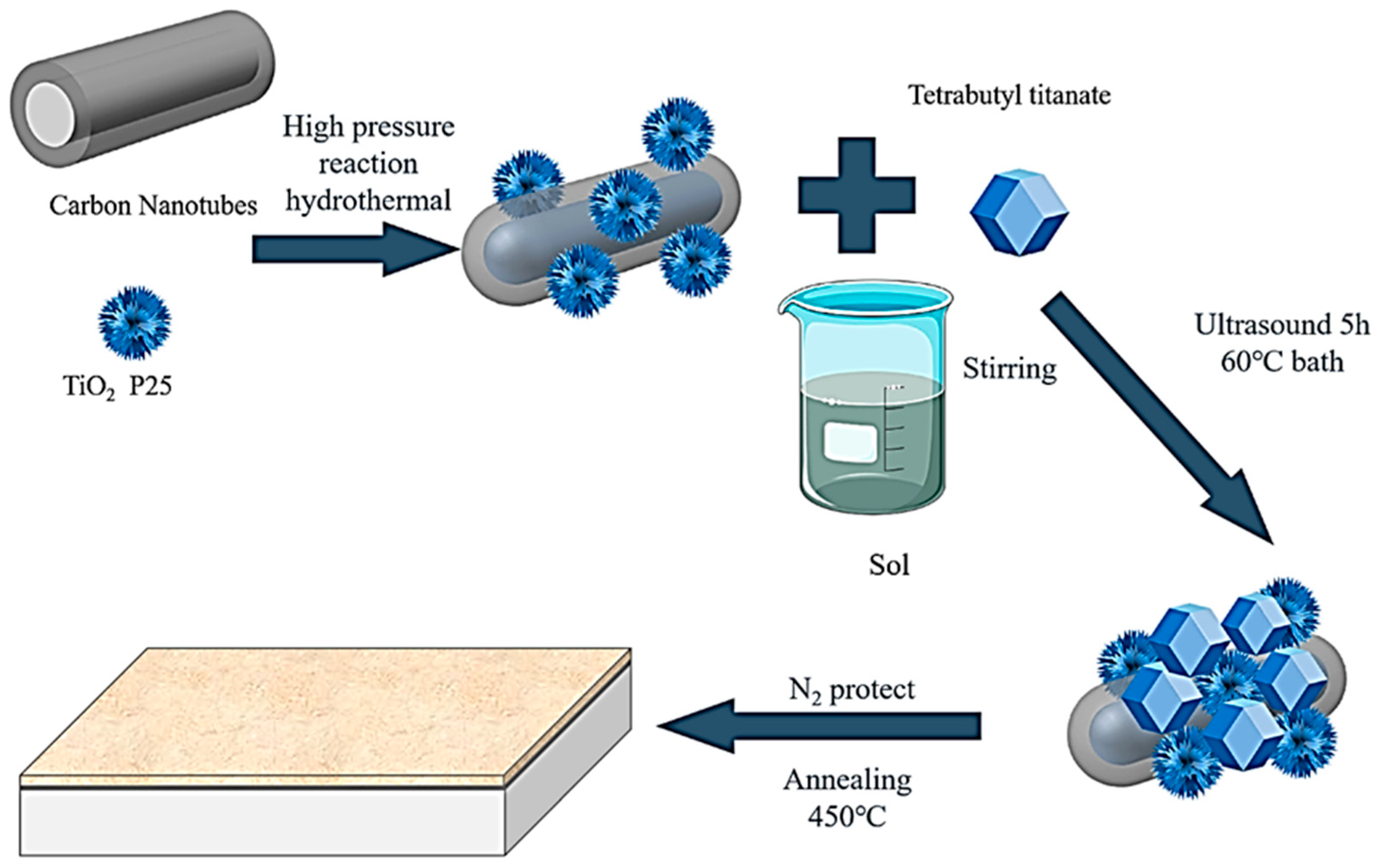

3.11. Sol-Gel Method

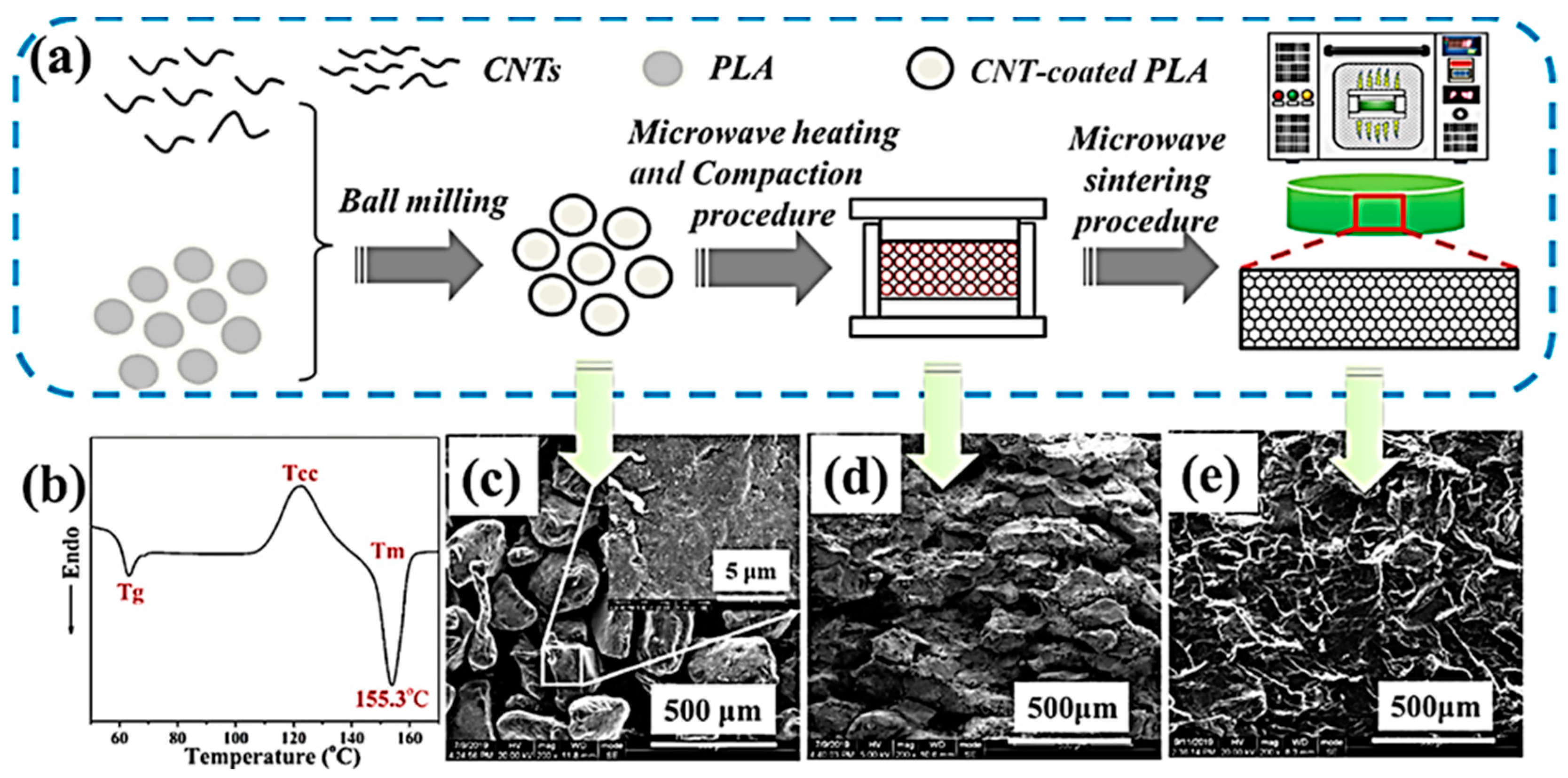

3.12. Microwave-Assisted Processing

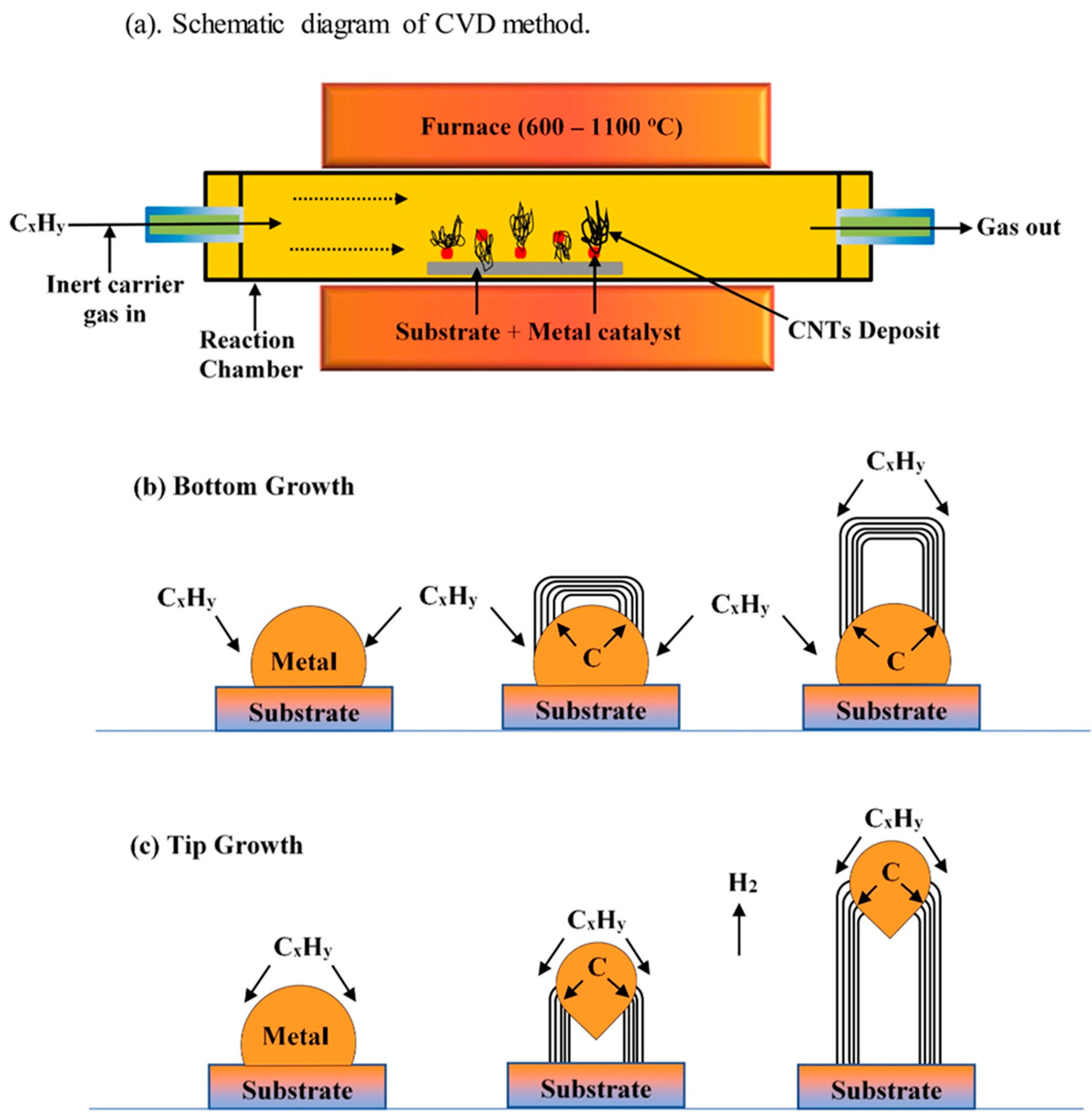

3.13. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) with PS Deposition

4. Rheological Properties of PS/CNT Composites

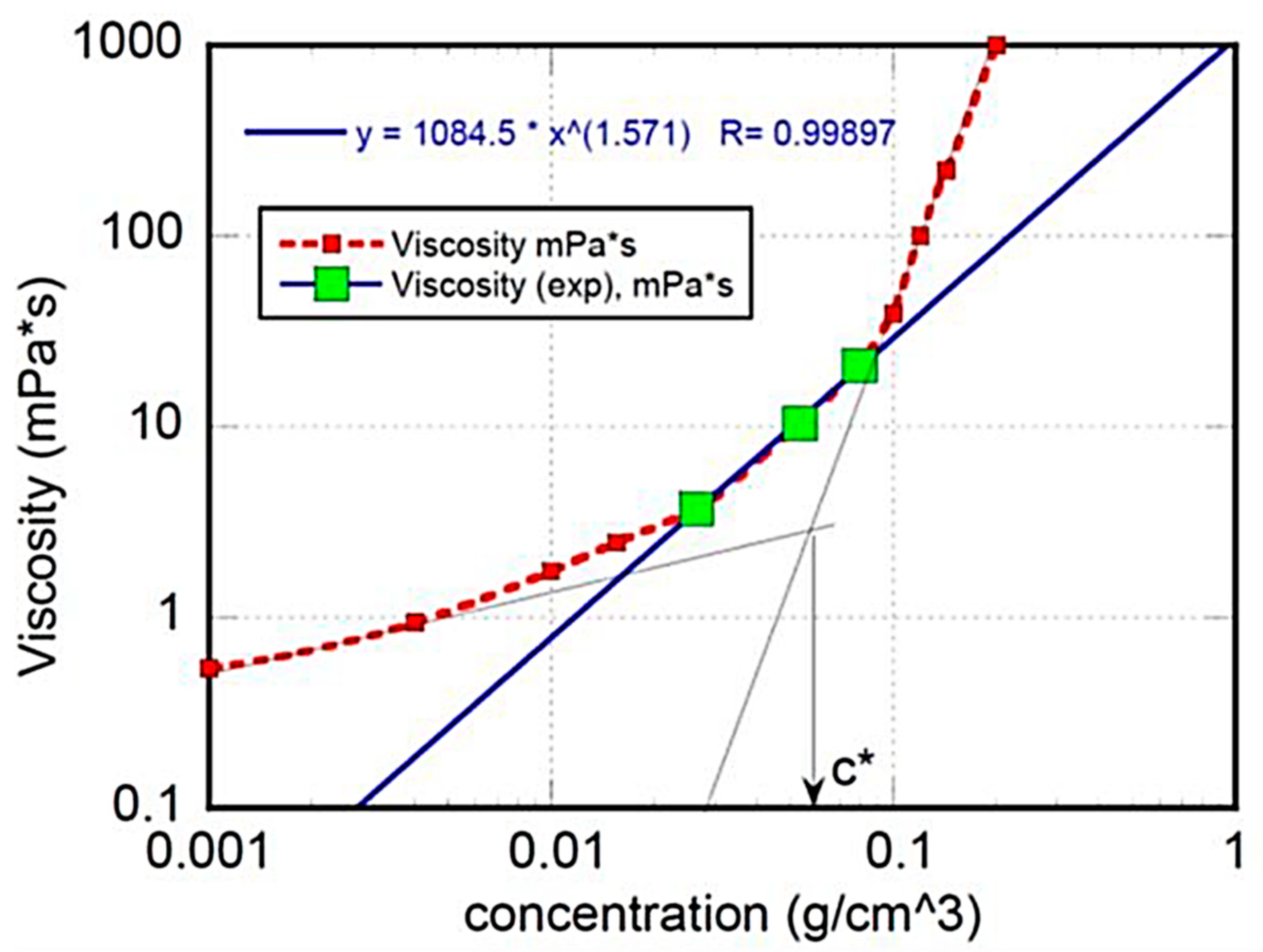

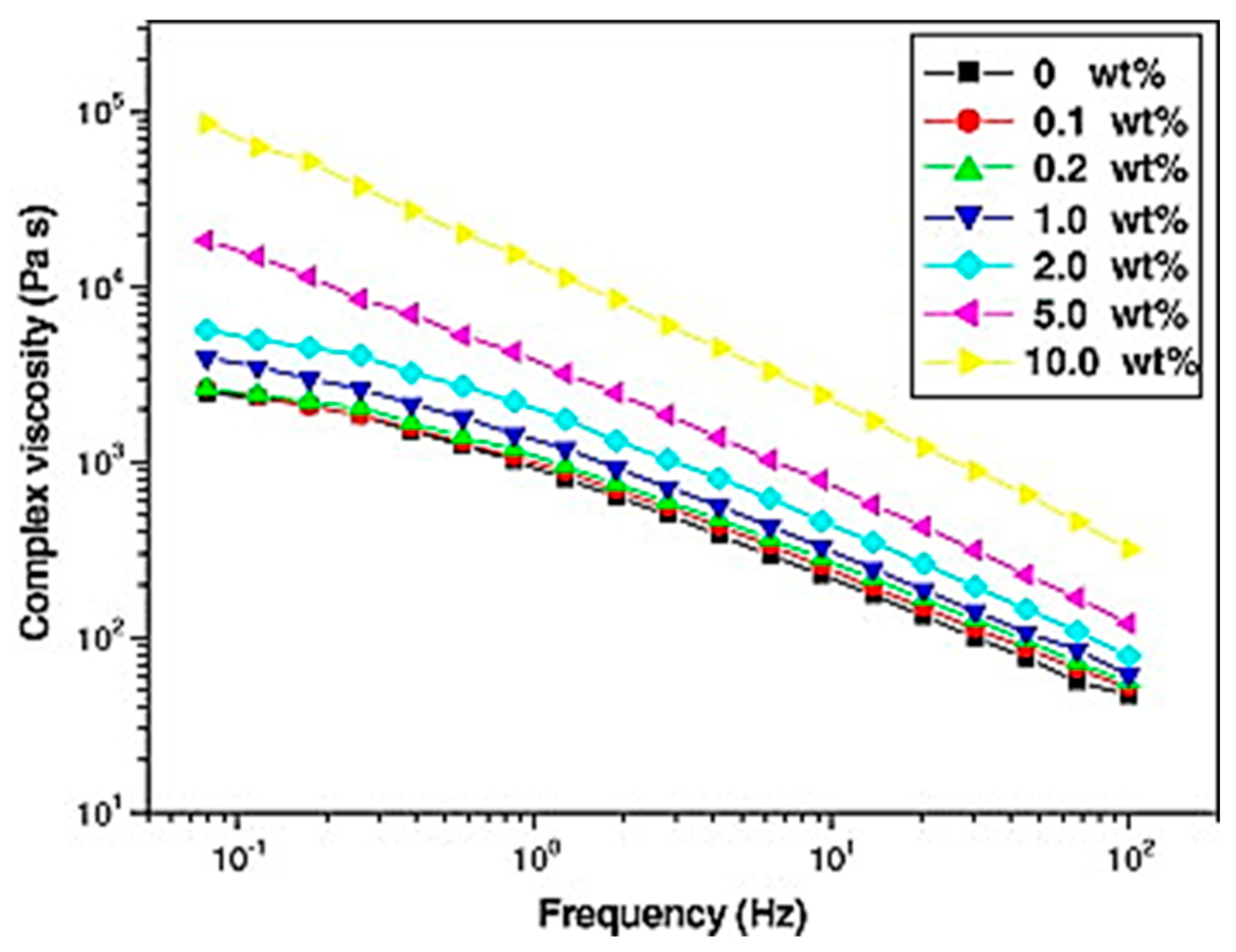

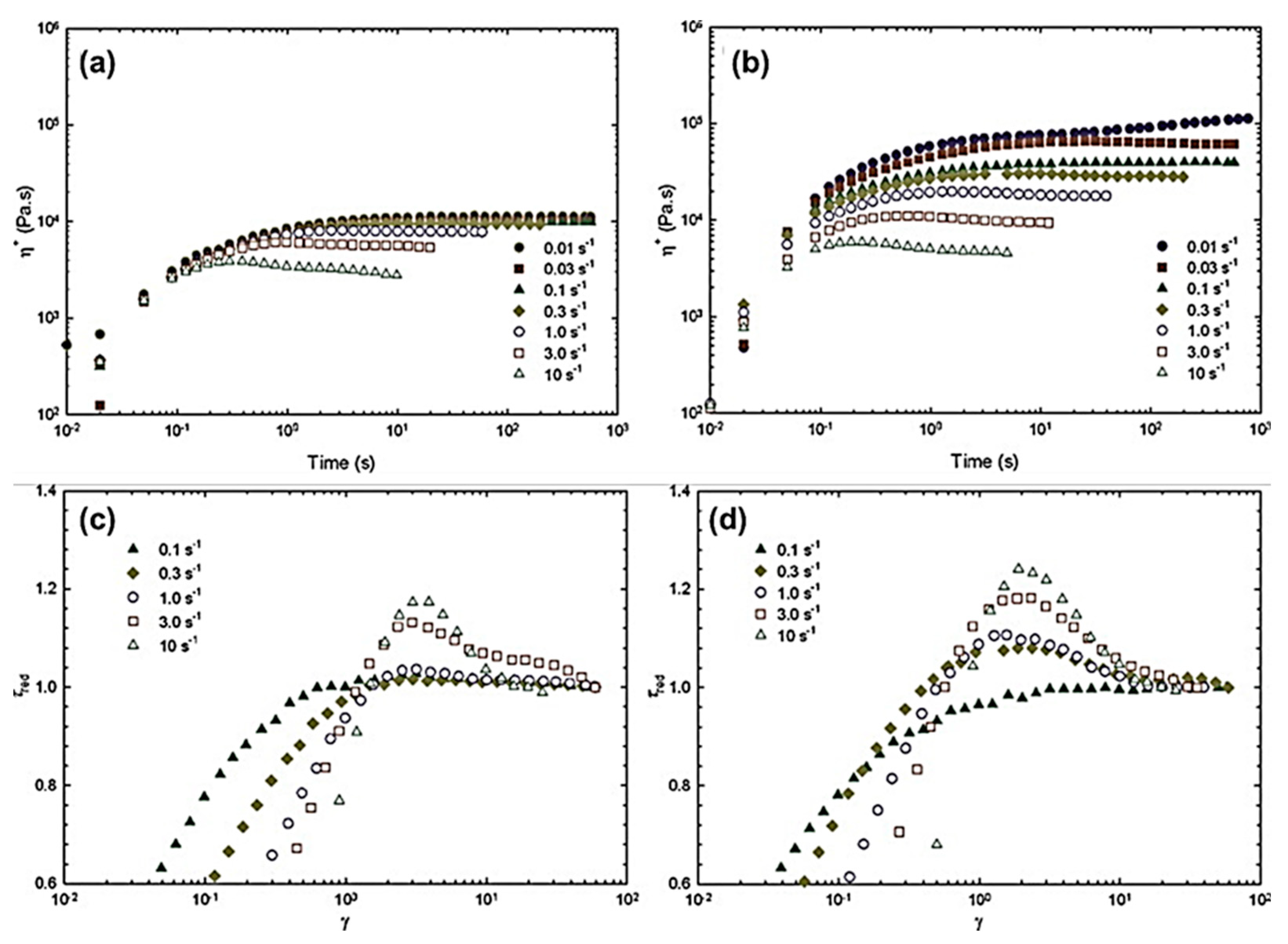

4.1. Relative and Complex Viscosity

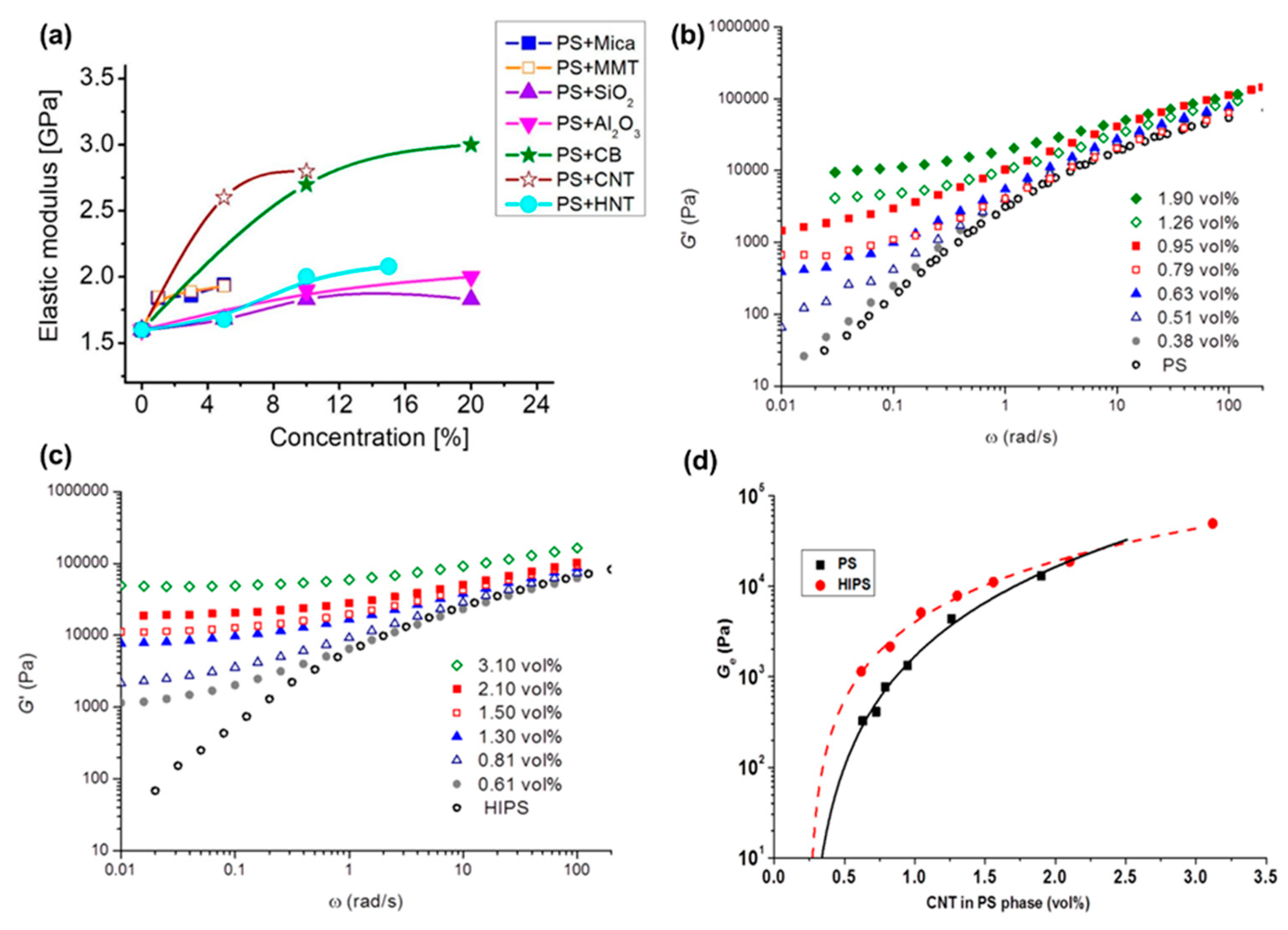

4.2. Elasticity

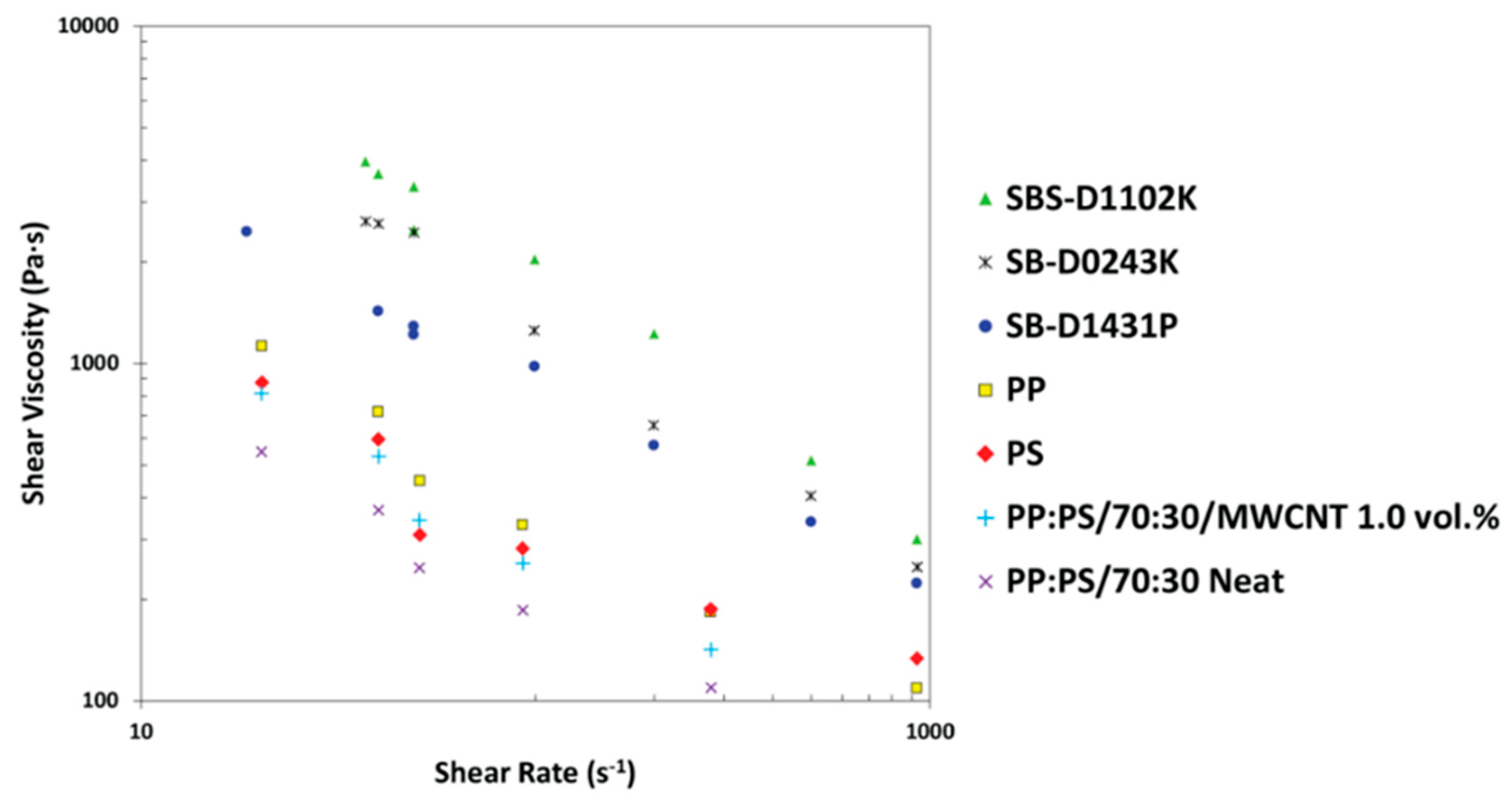

4.3. Shear Thinning and Flow Behavior

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oladele, I.O.; Omotosho, T.F.; Adediran, A.A. Polymer-based composites: an indispensable material for present and future applications. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 2020, 8834518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashfipour, M.A.; Mehra, N.; Zhu, J. A review on the role of interface in mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of polymer composites. Adv. Compos. Mater. 2018, 1, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergen, Ö.B.; Arda, E.; Evingür, G.A. Electrical, optical, and mechanical percolations of multi-walled carbon nanotube and carbon mesoporous-doped polystyrene composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2020, 54, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, A. Mechanical properties of CNT/polymer. In Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Polymers; Elsevier: 2018; pp. 201–232.

- Li, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Niu, K. Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes in Polystyrene and Properties of Their Composites: A Review. J. Polym. 2024, 16, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

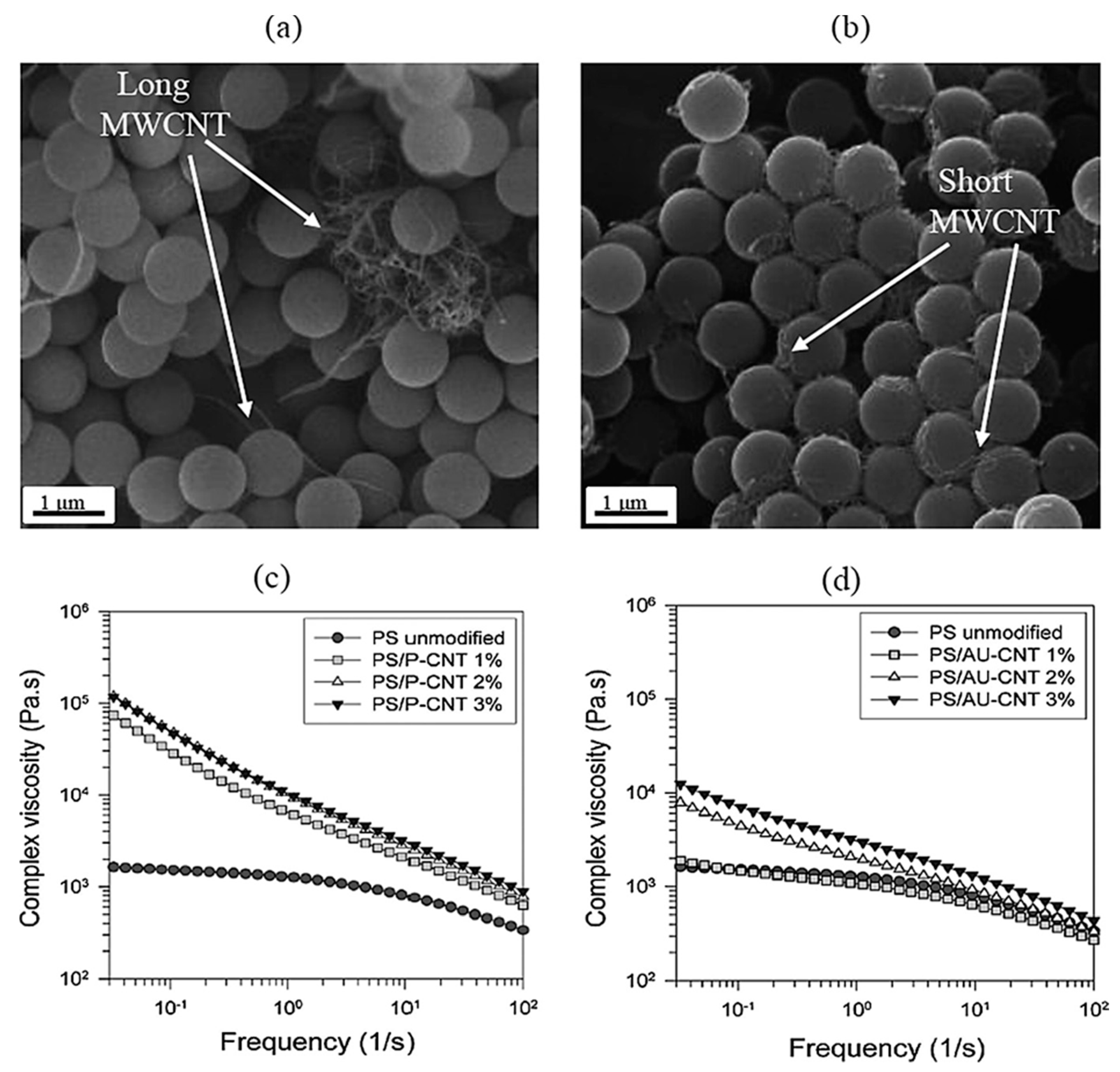

- Park, J.S.; An, J.H.; Jang, K.-S.; Lee, S.J. Rheological and electrical properties of polystyrene nanocomposites via incorporation of polymer-wrapped carbon nanotubes. KARJ 2019, 31, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H. Rheological properties and phase structure of polypropylene/polystyrene/multiwalled carbon nanotube composites. KARJ 2020, 32, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksar, M.-R.; Ghazi-Khansari, M. Determination of migration monomer styrene from GPPS (general purpose polystyrene) and HIPS (high impact polystyrene) cups to hot drinks. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2009, 19, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarraj, A.; Nauman, E.B. Super HIPS: improved high impact polystyrene with two sources of rubber particles. Polym. J. 2004, 45, 8435–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli Sulong, N.H.; Mustapa, S.A.S.; Abdul Rashid, M.K. Application of expanded polystyrene (EPS) in buildings and constructions: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksit, M.; Zhao, C.; Klose, B.; Kreger, K.; Schmidt, H.-W.; Altstädt, V. Extruded polystyrene foams with enhanced insulation and mechanical properties by a benzene-trisamide-based additive. Polym. J. 2019, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, L.S.; Schulz, D.N. Discovery of syndiotactic polystyrene: its synthesis and impact. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 3627–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Yaqoob, S.; Yu, J.; D'Amore, A. Critical review on the characterization, preparation, and enhanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of carbon nanotubes and their hybrid filler polymer composites for various applications. JCOMC 2024, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishi, E.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Saini, V.; Biris, A.R.; Lupu, D.; Biris, A.S. Carbon nanotubes: synthesis, properties, and applications. JPST 2009, 27, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Hamad, K.; Ko, Y.G. Fabrication and materials properties of polystyrene/carbon nanotube (PS/CNT) composites: a review. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 79, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnian, P.; D’Amore, A. Investigating the Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Polystyrene (PS)/Untreated SWCNT Nanocomposite Films. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, A.H.A.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U.; Trifkovic, M. Significance of interfacial interaction and agglomerates on electrical properties of polymer-carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2017, 125, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, N.; Ren, K.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Q. Exploring interfacial enhancement in polystyrene/multiwalled carbon nanotube monofilament induced by stretching. Compos. - A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 61, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmiri, N.; Hoseini, A.H.A.; Najmi, P.; Liu, J.; Milani, A.S.; Arjmand, M. Highly conductive polystyrene/carbon nanotube/PEDOT: PSS nanocomposite with segregated structure for electromagnetic interference shielding. Carbon 2023, 212, 118104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Gomes, V.G.; Altarawneh, I.S. Synthesizing polystyrene/carbon nanotube composites by emulsion polymerization with non-covalent and covalent functionalization. Carbon 2010, 48, 2925–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, B. Polystyrene-based and carbon fabrİc-reİnforced polymer composİtes containing carbon nanotubes: preparation, modification and characterization. 2020.

- Navas, I.O.; Kamkar, M.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U. Morphology evolution, molecular simulation, electrical properties, and rheology of carbon nanotube/polypropylene/polystyrene blend nanocomposites: Effect of molecular interaction between styrene-butadiene block copolymer and carbon nanotube. J. Polym. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, K.A.; Higgins, L.J.; Nahil, M.A.; Mishra, B.; Williams, P.T. Structural comparison of multi-walled carbon nanotubes produced from polypropylene and polystyrene waste plastics. JAAP 2022, 161, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, N.K.; Khatua, B. Development of electrical conductivity with minimum possible percolation threshold in multi-wall carbon nanotube/polystyrene composites. Carbon 2011, 49, 4571–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, N.; Maiti, S.; Suin, S.; Khatua, B. Influence of selective dispersion of MWCNT on electrical percolation of in-situ polymerized high-impact polystyrene/MWCNT nanocomposites. EXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nurazzi, N.; Asyraf, M.M.; Khalina, A.; Abdullah, N.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; Kamarudin, S.H.; Ahmad, S.b.; Mahat, A.M.; Lee, C.L.; Aisyah, H. Fabrication, functionalization, and application of carbon nanotube-reinforced polymer composite: An overview. J. Polym. 2021, 13, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, M.; Alix, S.; Lebeau, M.; Soulestin, J.; Lacrampe, M.-F.; Krawczak, P. Evaluation of rheological properties of non-Newtonian fluids in micro rheology compounder: Experimental procedures for a reliable polymer melt viscosity measurement. Polym. Test. 2014, 40, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

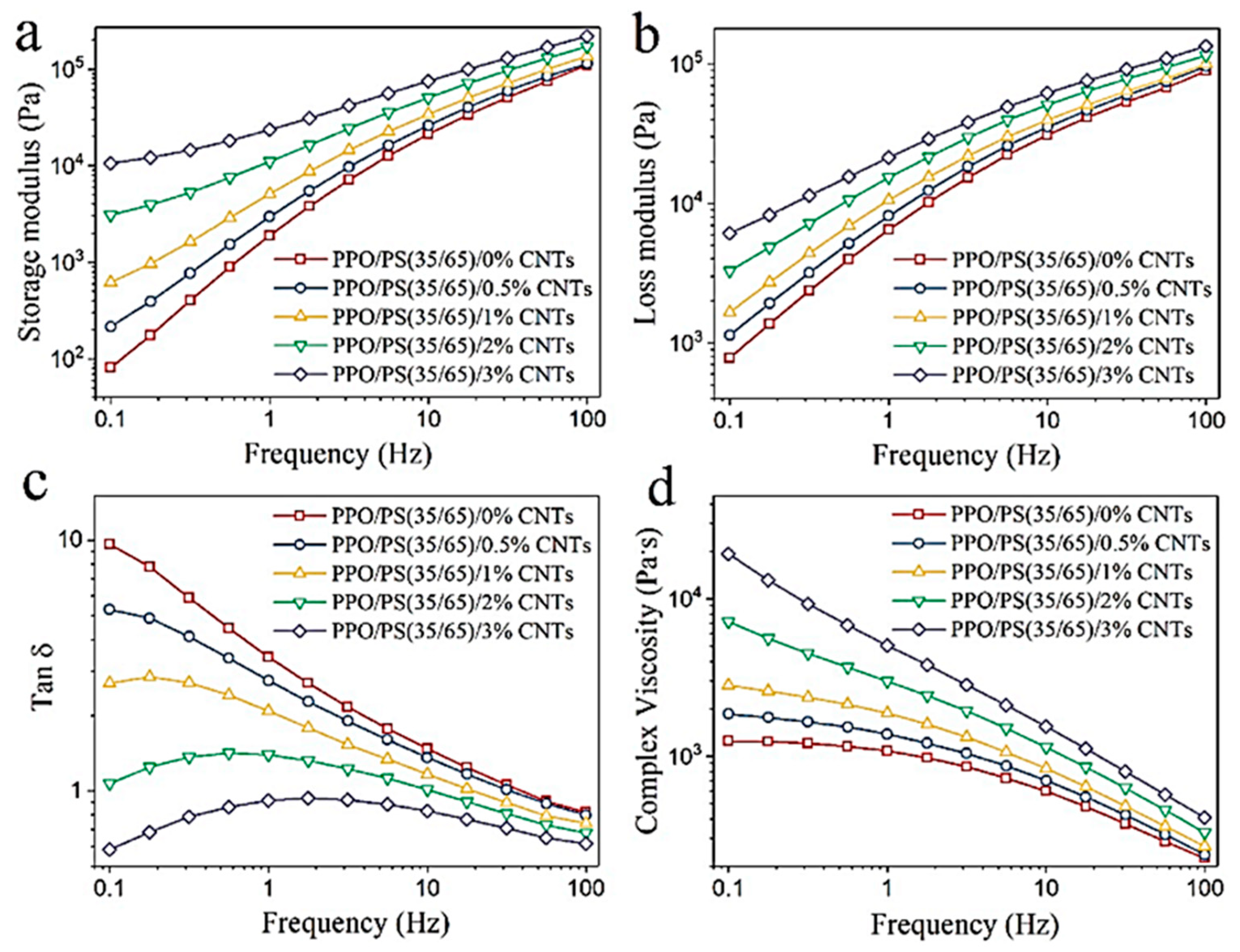

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Guo, B.-H.; Guo, Z.-X.; Yu, J. Electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube-filled miscible poly (phenylene oxide)/polystyrene blends prepared by melt compounding. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 176, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.G.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Mechanisms of mechanical reinforcement by graphene and carbon nanotubes in polymer nanocomposites. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2228–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, B.; Bayram, G. Influence of nanocomposite preparation techniques on the multifunctional properties of carbon fabric-reinforced polystyrene-based composites with carbon nanotubes. SPE Polymers 2022, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Suresh, K.; Kumar, R.V.; Kumar, M.; Pugazhenthi, G. A simple solvent blending coupled sonication technique for synthesis of polystyrene (PS)/multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) nanocomposites: effect of modified MWCNT content. Journal of Science: JS: AMD s 2016, 1, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolo, D.; Piazza, A.; Cottini, C.; Serafini, M.; Lutero, E.; Cuoghi, E.; Gasparini, L.; Botturi, D.; Marino, I.G.; Aliatis, I. Raman spectroscopy as a PAT for pharmaceutical blending: Advantages and disadvantages. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 149, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, L.; Sundararaj, U. Interface strengthening of ps/apa polymer blend nanocomposites via in situ compatibilization: Enhancement of electrical and rheological properties. J. Mater 2021, 14, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patole, A.S.; Patole, S.; Yoo, J.B.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, T.H. Effective in situ synthesis and characteristics of polystyrene nanoparticle-covered multiwall carbon nanotube composite. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2009, 47, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, A.V.; Kanny, K.; Abitha, V.; Thomas, S. Methods for synthesis of nanoparticles and fabrication of nanocomposites. In Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials; Elsevier: 2018; pp. 121–139.

- Quijano, J.R.B. Mechanical, electrical and sensing properties of melt-spun polymer fibers filled with carbon nanoparticles. TUD, 2018.

- Farha, F.I.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, L.; Xu, F. Microstructural Tuning of Twisted Carbon Nanotube Yarns through the Wet-Compression Process: Implications for Multifunctional Textiles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 11071–11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Kong, D.; Tao, J.; Kong, N.; Mota-Santiago, P.; Lynch, P.A.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, J. Wet Twisting in Spinning for Rapid and Cost-Effective Fabrication of Superior Carbon Nanotube Yarns. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 2400197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.; Chakradhar, R.; Bera, P.; Anand Prabu, A. UV and thermally stable polystyrene-MWCNT superhydrophobic coatings. SIA 2017, 49, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, J.; Yu, S. New fabrication of Styrene-Butadiene Rubber/Carbon Nanotubes nanocomposite and corresponding mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, S.; Jain, D.; Meruva, S.K.; Rongala, G.; Juluri, A.; Nihalani, G.; Mamidi, H.K.; Nukala, P.K.; Bolla, P.K. Recent advances in amorphous solid dispersions: preformulation, formulation strategies, technological advancements and characterization. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozmen, L.; Langrish, T. A study of the limitations to spray dryer outlet performance. Dry. Technol. 2003, 21, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Jeong, S. Reusable carbon nanotube-embedded polystyrene/polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous sorbent for managing oil spills. Desalination 2022, 537, 115865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parangusan, H.; Ponnamma, D.; Hassan, M.K.; Adham, S.; Al-Maadeed, M.A.A. Designing carbon nanotube-based oil absorbing membranes from gamma irradiated and electrospun polystyrene nanocomposites. J. Mater. 2019, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.Y.; Bode, R.; Escárcega-Bobadilla, M.V.; Zelada-Guillén, G.A.; Maier, G. Polymer nanocomposites from self-assembled polystyrene-grafted carbon nanotubes. New J Chem 2016, 40, 4625–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, G.-J. A novel method for well-organized polystyrene-grafted multi-walled carbon nanotube bundles via self-assembly in tetrahydrofuran. Fibers Polym. 2013, 14, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Lu, X. Facile fabrication of polystyrene/carbon nanotube composite nanospheres with core-shell structure via self-assembly. Polym. J. 2010, 51, 3715–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Ning, B.; Harp, M.G.; Culp, S.H.; Hu, S.; Huang, P.; Nie, L.; Chen, J. Gold nanoparticle coated carbon nanotube ring with enhanced raman scattering and photothermal conversion property for theranostic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7005–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Tao, X.; Shi, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, N. From materials to components: 3D-printed architected honeycombs toward high-performance and tunable electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos B Eng 2022, 230, 109500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskakova, K.I.; Okotrub, A.V.; Bulusheva, L.G.; Sedelnikova, O.V. Manufacturing of carbon nanotube-polystyrene filament for 3D printing: nanoparticle dispersion and electromagnetic properties. J. Nanoeng. Nanomanuf. 2022, 2, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. A review of conductive carbon materials for 3D printing: Materials, technologies, properties, and applications. J. Mater. 2021, 14, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Han, J.Y.; Yoon, H.; Joo, P.; Lee, T.; Seo, E.; Char, K.; Kim, B.-S. Carbon-based layer-by-layer nanostructures: from films to hollow capsules. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4515–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Kotov, N.A. Composite layer-by-layer (LBL) assembly with inorganic nanoparticles and nanowires. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H. Layer-by-layer assembly: from conventional to unconventional methods. ChemComm 2007, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, M. Processing and study of carbon nanotube/polymer nanocomposites and polymer electrolyte materials. 2007.

- Lubineau, G.; Rahaman, A. A review of strategies for improving the degradation properties of laminated continuous-fiber/epoxy composites with carbon-based nanoreinforcements. Carbon 2012, 50, 2377–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-H.; Hung, P.-S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, P.-W. Combination of microspheres and sol-gel electrophoresis for the formation of large-area ordered macroporous SiO2. Electrochem. commun. 2017, 85, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Chen, G.Z.; Puma, G.L. Carbon nanotubes/titanium dioxide (CNTs/TiO2) nanocomposites prepared by conventional and novel surfactant wrapping sol–gel methods exhibiting enhanced photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal., B 2009, 89, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, N.; Takahashi, T.; Terui, N.; Furukawa, S. Synthesis of polystyrene@ TiO2 core–shell particles and their photocatalytic activity for the decomposition of methylene blue. Inorganics 2023, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, W.; Lin, Y.; Feng, Z. Physicochemical and Antibacterial Evaluation of TiO2/CNT Mesoporous Nanomaterials Prepared by High-Pressure Hydrothermal Sol–Gel Method under an Ultrasonic Composite Environment. Molecules 2023, 28, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modan, E.M.; PLĂIAȘU, A.G. Advantages and disadvantages of chemical methods in the elaboration of nanomaterials. The Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati. Fascicle IX, Metallurgy and Materials Science 2020, 43, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, P.; Chen, W.; Liu, P.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z. Microwave-assisted foaming and sintering to prepare lightweight high-strength polystyrene/carbon nanotube composite foams with an ultralow percolation threshold. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 9702–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Tang, J.; Ye, F.; Liu, P. Microwave-assisted sintering to rapidly construct a segregated structure in low-melt-viscosity poly (lactic acid) for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS omega 2020, 5, 26116–26124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Aghvami-Panah, M.; Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Seraji, A.A.; Zeraatkar, A.; Ghaffarian Anbaran, R.; Xiao, X. Fabricating bimodal microcellular structure in polystyrene/carbon nanotube/glass-fiber hybrid nanocomposite foam by microwave-assisted heating: a proof-of-concept study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 52125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, P.; Sakhiya, A.K.; Kaushal, P. Ultrafast growth of carbon nanotubes using microwave irradiation: characterization and its potential applications. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Martínez, F.G.; Domratcheva-Lvova, L.; Flores-Ramírez, N.; García-González, L.; Zamora-Peredo, L.; Mondragón-Sánchez, M.d.L. Composite films from polystyrene with hydroxyl end groups and carbon nanotubes. Mater. Res. 2017, 19, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzenko, N.; Godzierz, M.; Kurtyka, K.; Hercog, A.; Nocoń-Szmajda, K.; Gawron, A.; Szeluga, U.; Trzebicka, B.; Yang, R.; Rümmeli, M.H. Flexible Piezoresistive Polystyrene Composite Sensors Filled with Hollow 3D Graphitic Shells. J. Polym. 2023, 15, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodnik, V.V.; Dzunuzovic, E.; Dzunuzovic, J. Synthesis and characterization of polystyrene based nanocomposites. Polystyrene: Synthesis, Characteristics and Applications, 1st ed.; Lynwood, C., Ed 2014, 201-240.

- CARREAU, P.J. RHEOLOGY OF POLYMERS WITH NANOFILLERS. 2010.

- Park, S.-D.; Han, D.-H.; Teng, D.; Kwon, Y. Rheological properties and dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) in polystyrene matrix. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2008, 8, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarali, C.S.; Patil, S.F.; Pilli, S.C.; Lu, Y.C. Modeling the effective elastic properties of nanocomposites with circular straight CNT fibers reinforced in the epoxy matrix. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 3160–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

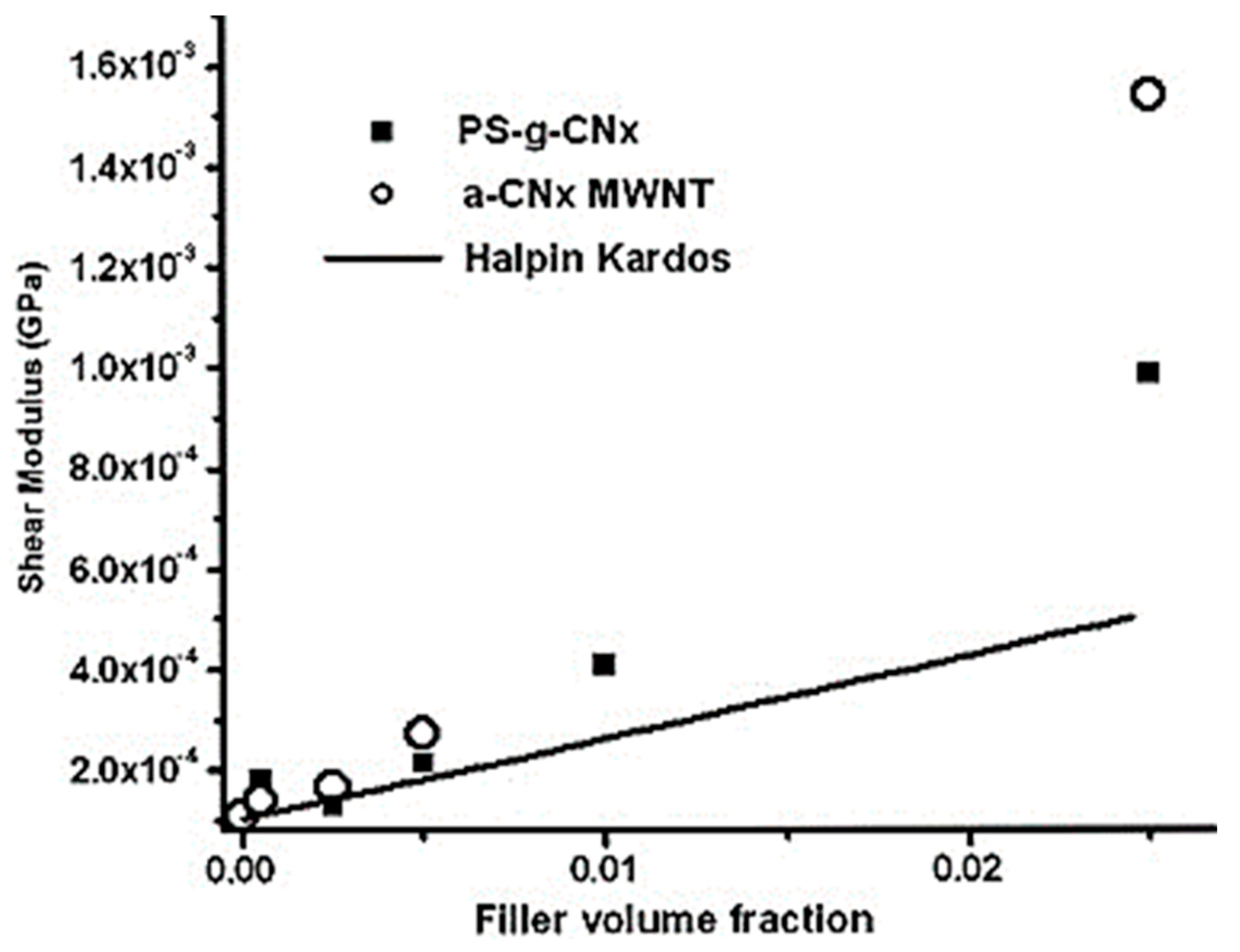

- Fragneaud, B.; Masenelli-Varlot, K.; Gonzalez-Montiel, A.; Terrones, M.; Cavaille, J.-Y. Mechanical behavior of polystyrene grafted carbon nanotubes/polystyrene nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 3265–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

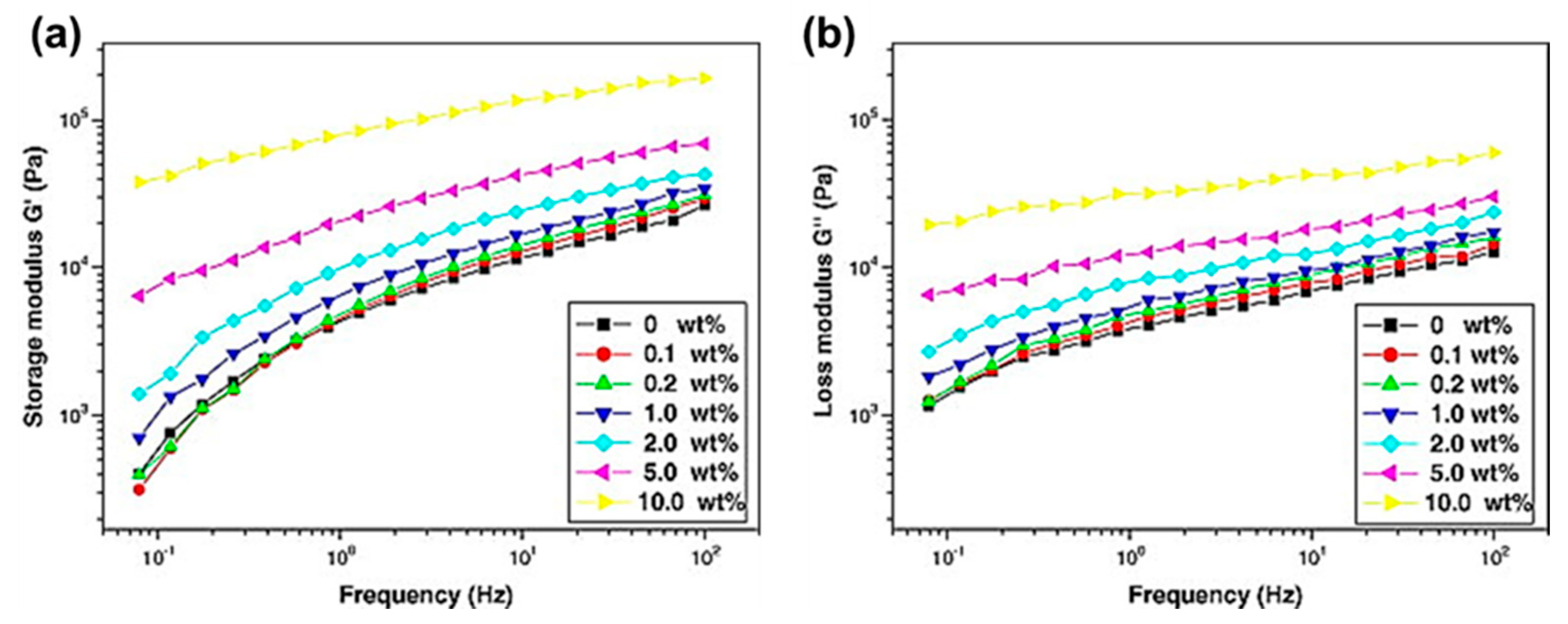

- Moskalyuk, O.A.; Belashov, A.V.; Beltukov, Y.M.; Ivan’kova, E.M.; Popova, E.N.; Semenova, I.V.; Yelokhovsky, V.Y.; Yudin, V.E. Polystyrene-based nanocomposites with different fillers: Fabrication and mechanical properties. J. Polym. 2020, 12, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcourt, M.; Cassagnau, P.; Fulchiron, R.; Rousseaux, D.; Lhost, O.; Karam, S. High Impact Polystyrene/CNT nanocomposites: Application of volume segregation strategy and behavior under extensional deformation. J. Polym. 2018, 157, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoudi, M.; Phuoc, T.X. Remarks on constitutive modeling of nanofluids. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2012, 4, 927580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagarise, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Mahboob, M.; Koelling, K.W.; Bechtel, S.E. Transient shear rheology of carbon nanofiber/polystyrene melt composites. J. Nonnewton. Fluid Mech. 2010, 165, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).