1. Introduction

This involves incorporating vaccination into the study of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease transmission dynamics to understand the effects of different immunization strategies on outbreaks within populations. Vaccination has the potential to significantly lower the basic reproduction number (

), the number of secondary infections produced by the average infected person. The immunization of a large part of the population susceptible to infection breaks the chain of transmission, which will slow or reduce the spread of the virus. In communities where vaccination is highly prevalent, HFMD outbreaks may remain impressively low due to fewer people susceptible to the virus [

1,

2]. Besides, vaccination may assist in herd immunity, whereby the unvaccinated populations tend to benefit from the reduced virus circulation. In addition, vaccine efficacy and coverage rates, and even age distribution among the vaccinated population [

3], might be other factors influencing the effectiveness of vaccination in HFMD control. This can be accomplished using mathematical modeling and epidemiological studies to determine what different vaccination scenarios would yield an effect on, thereby assisting program designers in developing specific immunization programs that would limit the burden of HFMD in at-risk populations.

The modes of transmission of infectious diseases represent a variety of mechanisms, generally classified into two broad categories: direct and indirect. Direct transmission may occur through actual physical contact, respiratory droplets, or several body fluids to permit the transfer of infectious agents from one host to another. Indirect transmission involves intermediate agents such as fomites (inanimate infected objects), vectors like mosquitoes, and air particles [

4,

5]. Mathematical modeling further elucidates the complex nature of disease spread and provides critical tools for describing and predicting transmission dynamics. The basic notions include the basic reproduction number,

, defined as the average number of secondary infections produced by one infected individual in a wholly susceptible population, indicating a pathogen’s contagiousness. SIR and SEIR compartment models have been one of the most used compartment models to simulate dynamics of diseases within populations by partitioning individuals into different compartments depending on their disease status [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Agent-based models explicitly simulate the individual-to-individual interactions within a population and hence provide yet further detail, and are thus much better suited to capturing heterogeneous mixing patterns and individual behavior. Stochastic models incorporate randomness in the transmission process; this is appropriate for modeling the natural variability and, in particular, the unpredictability of real-world disease transmission. The network model approaches that explicitly represent populations as interconnected networks of individuals offer insight into how the structure of social interactions drives disease dynamics. Besides these mathematical methods, a significant contribution is seen in modern epidemiology in data-driven approaches. Using data around surveillance analysis and genomic epidemiology, model-based approaches use real-time data and large datasets to track disease spread, identify risk factors, and optimize intervention strategies.

Another key aspect involves intervention modeling, such as different vaccination scenarios, simulations for quarantine and isolation policies, and social distancing measures. These models enable the modeling of the potential impacts of various interventions on disease containment and control. In reality, such models are used in planning pandemic responses, and governments and health agencies use them to forecast outbreaks, assess the effectiveness of interventions, and inform resource allocation. But once again, such models are hostage to the quality of data, the accuracy of assumptions behind them, and their ability to capture uncertainty and behavior changes in the population. Nonetheless, model techniques will remain invaluable for scientific insight and management of infectious disease spread.

2. Preliminaries

This section presents basic definitions, theorems, and results connected with the stability, existence, and uniqueness of the model developed based on the Caputo fractional derivative. Such a mathematical toolkit will provide a complete setting where the dynamic behavior of the model will be scrutinized. Moreover, we start by recalling some relevant definitions of the Caputo fractional derivatives, fixed point theorems, and stability criteria. These are critical elements to help validate the robustness and reliability of our model for capturing the dynamics of HFMD.

Definition 1 ([

16]).

The integral formula for the Caputo-fractional derivative of order for a function that is -differentiable is given by:

Theorem 1 ([

17]).

Any contractive operator that maps a complete metric space onto itself has a unique fixed point . Furthermore, satisfies the following condition:

Definition 2 ([

18]).

For integrable function and , the fractional-integral for the function f of order α is given by

Lemma 1 ([

19]).

Representing the Laplace transform associated with the Caputo fractional derivative:

Theorem 2 ([

20]).

The equilibrium solutions of the Caputo-fractional differential equations system The Jacobian matrix evaluated at equilibrium points ensures local asymptotic stability (LAS) if its eigenvalues satisfy

Theorem 3 ([

21]).

Let be a continuous and derivable function. If and , then for any time instant , we have

Theorem 4 ([

22]).

Let be the equilibrium point of , where is a domain containing . By defining , and assuming U is a continuously differentiable (Lyapunov candidate) map such that:

, for all nonnegative and for all ,

for given continuous positive definite functions on . Then is globally asymptotically stable.

Our article is organized as follows: We begin with the proposed model, introducing the fractional model and the proofs of existence and uniqueness. This is followed by a section dedicated to Equilibrium Stability Analysis. Next, we include a section on Endemic Equilibrium. Finally, we conclude with a section on Discussion and Numerical Results.

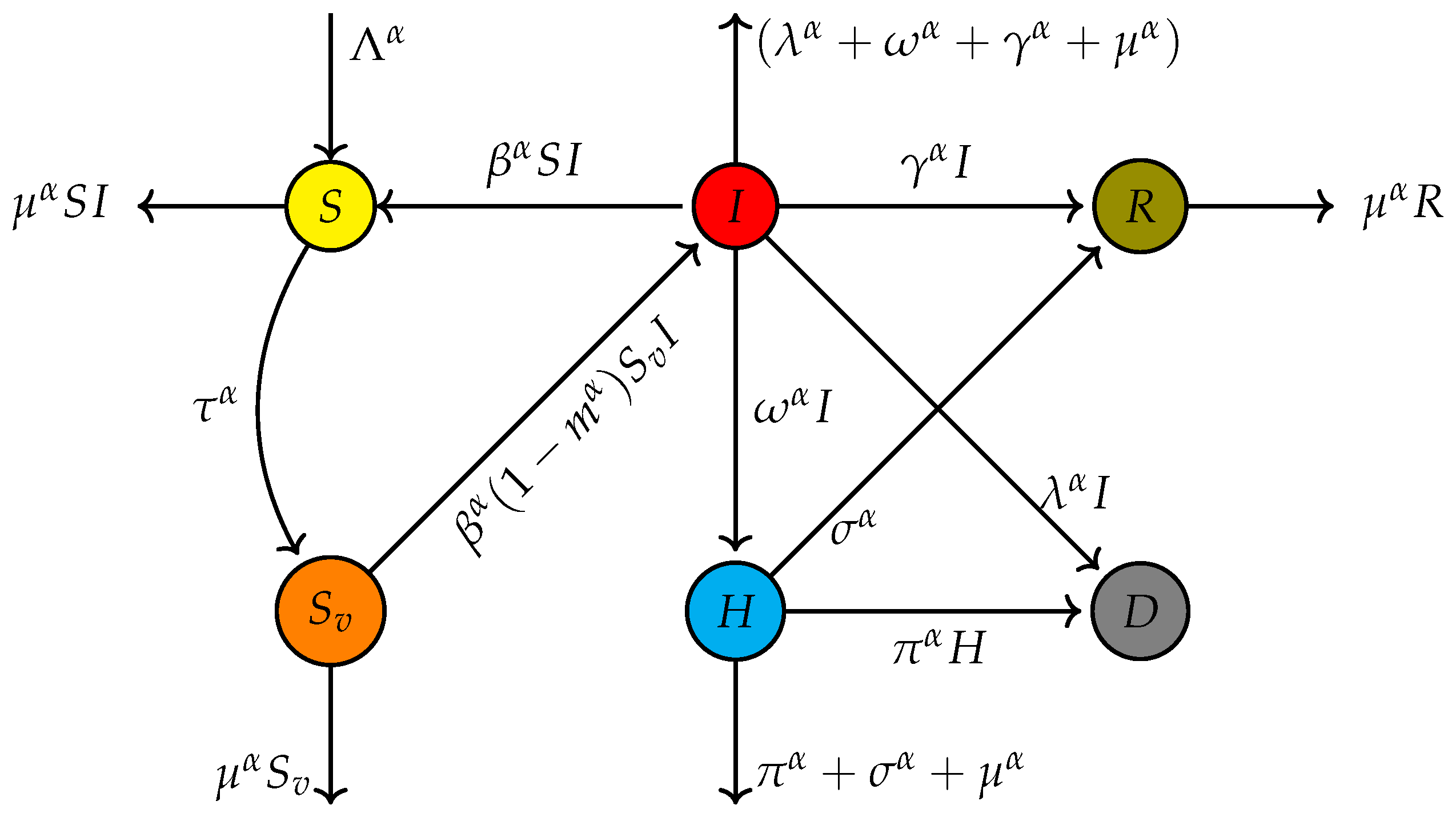

3. Proposed Model for HFMD Dynamical Spreading

In this section, we introduce a system of differential equations incorporating fractional derivatives to model the dynamical spreading of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD). Using fractional derivatives allows for a more accurate representation of memory and hereditary properties in the disease transmission process. This approach captures the complex dynamics of HFMD more effectively than traditional integer-order models. The equations presented here reflect these advanced modeling techniques, providing a robust framework for analyzing the spread of HFMD under various realistic scenarios, including vaccination efficiency. Figure

1 illustrates the interconnections between compartments, with all parameters clearly defined, while the system of equations

1 mathematically describes the dynamic behavior depicted in

Figure 1.

With the initial conditions:

Table 1 summarizes the detailed descriptions of the variables and parameters used in the proposed model. The model tracks different groups of the population based on their health state.

S is the class of the susceptible population, and

accounts for the vaccinated susceptible individuals.

I denotes the proportion of those infected,

H - those hospitalized, and

R - those recovered. The parameters describe basic model dynamics:

describes new inflows into the population,

describes the mortality rate, and

describes the rate at which an infection spreads in the population. The vaccination efforts are described through

, while through

and

, the recovery rate models describe the infected and hospitalized populations. Hospitalization and death rates are described through

,

, and

. Finally,

describes the efficiency of the vaccine to impede the infection. The above variables and parameters define the dynamics of infection, recovery, hospitalization, and population mortality.

3.1. Positivity and Boundedness

In a mathematical model for epidemiology, positivity and boundedness are the two major features that guarantee the model operates in a way that shows real population dynamics. Positivity guarantees that no model variable, representing the number of susceptible, infected, or recovered individuals at any given time, assumes a negative value, which does not make biological sense. Boundability means that the model variables do not grow boundless but rather stay within the confines of the total size of a finite population. These characteristics are crucial for ensuring the model’s validity and reliability in accurately portraying the dissemination and management of diseases.

Define the region . Where is the Mittag-Leffler function. The following theorem shows that is positively invariant.

Theorem 5. The non-negative region Ω that includes the solutions of the model’s (1) equations is positively invariant for .

Proof. Write the total population

to be the sum of the model’s components i.e.

. Then

Therefore, we conclude that

To proceed with the proof we, Let

be the Laplace transform of

with the initial condition

. By the application of the Laplace transform on Equation (

2), we have

To find

, we take Laplace inverse of both sides of Equation (

3), to get:

Thus, , which completes the proof.

□

3.2. Existence and Uniqueness

We can prove the existence and uniqueness of the solution for the fractional epidemic model of foot, hand, and mouth disease by applying mathematical methodologies, mainly fixed-point theorems. The accent is on the Banach fixed-point theorem. This model, which combines fractional derivatives, better describes the dynamics of the disease due to the presence of memory in the population. The existence of a solution guarantees a well-defined trajectory of the disease spread for any given set of initial conditions. On the other hand, uniqueness guarantees that the behavior is deterministic; the course of the disease progression can thus be predicted and is not dependent on arbitrary choices. These properties are usually demonstrated by converting the system to an appropriate integral form and showing that the associated operator satisfies the fixed-point theorem conditions to guarantee the solution’s existence and uniqueness. The conclusion here is that the model produces a reliable prediction about the dynamics of the epidemic over time.

Theorem 6. Equations of System (1) are satisfying the Lipschitz continuous for

Proof. Rewrite the equations of System (

1) in a steady-state mode as follows:

Upon applying Theorem 1, we obtain:

Where .

Similarly, the following results can be obtained:

Where,

,

,

, which completes the proof. □

Lemma 2. A Volterra-integral equations form can represent the system of equations of the model (1).

Proof. Consider the system of equations of the Model (

1)

By the application of Definition (2) to both sides of the Equation (

4), we get:

The left-hand side reduced to

and hence Equation (

5) becomes

Thus, the proof is completed, and the system of equations of the Model (

1) is converted to the following equivalent system of Volterra-integral equations:

□

Theorem 7 ([

28]).

For and . Let be Lipschitz condition and continuous bounded , where . If , then ∃ only one solution for the initial value problem (1), namely, , where . .

Proof. Let , . Since every sequence in X converges to with respect to infinity norm, , and x is continuous and , then . Thus, X is closed and hence a complete metric space.

Define such that

, where

then

Therefore, , and hence, maps X onto itself.

To show that

is a contraction operator, we assume that

, such that

Therefore,

. Thus, by the assumption

,

is a contraction mapping. Therefore, it possesses a unique fixed point. The system (

1) has a unique solution. □

4. Equilibrium Stability Analysis

4.1. Basic Reproduction Number

The reproduction number, referred to as

, is an essential threshold parameter that defines the stability of the foot, hand, and mouth disease epidemic model. This parameter quantifies the mean number of secondary infections that result from one infected individual within a completely susceptible population. If

, then the disease-free equilibrium is stable, and the disease will die out eventually; otherwise, if

, then the disease will spread in the population, and the endemic equilibrium becomes stable. The reproduction number can be obtained by the next-generation matrix method, which involves linearizing the differential equations around the disease-free equilibrium system and then analyzing the transmission and recovery rates. The principal eigenvalue of the resultant matrix yields

, offering valuable information regarding the likelihood of disease outbreaks and guiding control measures [

29]. Following [

30], the infection states are divided into transmission and transition matrices as follows:

By the application of theorem (2) in [

30], the basic reproduction number is defined to be the spectral radius of the matrix

, i.e.,

. Therefore, the basic reproduction number can be given by the following expression:

4.2. Existence of Equilibria

To find the Hand, foot, and mouth-free equilibrium point (HFMEEP), we set the right-hand side of the model’s (

1) equations to Zero. to get

The solution of the system (

9) is given by:

4.3. Local Stability Analysis

This section investigates local stability analysis of the fractional mathematical model of hand, foot, and mouth disease. The system’s behavior around its equilibrium points, particularly the disease-free equilibrium, is dealt with. Considering the nonlinear system of fractional differential equations, a linear system is considered around the approximate equilibrium solution. Then, the stability of such an equilibrium can be determined by the eigenvalue analysis of the Jacobian matrix of the system. In most cases, a fractional-order model’s Jacobian matrix characteristic equation involves the fractional powers of the eigenvalues and the integer-order classical models. When viewed in the context of fractional derivatives, if all the eigenvalues have negative real parts, then the equilibrium point is locally stable; small perturbations will decay in time and lead the system back to the equilibrium point. This, in turn, gives such an analysis a high degree of importance because understanding the dynamics of initial outbreaks and under what conditions this disease can be controlled or even eradicated is a must. Thus, the Jacobian matrix for the Model (

1) is given by

Theorem 8. The hand, foot, and mouth disease-free equilibrium point, , is locally asymptotically stable.

Proof. At the HFMD free equilibrium point,

, the Jacobian matrix is given as follows:

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix at the HFMD free equilibrium point,

, are the solutions of the characteristic equation of the

, i.e.,

. Namely,

. Since all the eigenvalues of

are negative real numbers, then

for

.

Thus, by theorem (2), the HFMD free equilibrium point, is locally asymptotically stable. □

5. Endemic Equilibrium

Endemic equilibrium of hand, foot, and mouth disease can be defined as a steady-state condition whereby the disease persists within a population at a constant level over time. This, in other words, means that the number of infected individuals at this equilibrium remains the same, neither increasing nor decreasing significantly, since the rates of new infections and recoveries balance out one another. Mathematical models of the disease use parameters on transmission rates and recovery rates for population dynamics in analyzing the endemic equilibrium. The endemic equilibrium is helpful for a long-term understanding of the disease and for assessing control strategies. This equilibrium is hugely important because the stability analysis will show whether small perturbations will cause the disease prevalence to go back to its steady state or give rise to outbreaks, and it may thus be central to informing public health interventions.

5.1. Existence of the HFMD Endemic Equilibrium

Let

be an equilibrium point of the Model (

1). Thus, the following theorem follows.

Theorem 9. The proposed Model (1) has a unique endemic equilibrium point , whenever .

Proof. By solving the equations of the steady-state model (

9) at the endemic equilibrium point

, we get

It is readily seen that all the compartments are positive whenever

. Moreover,

iff

.

which implies that

. That is

since

a is always positive. Thus,

which implies that

Therefore,

. Which completes the proof. □

5.2. Global Stability Analysis

Global stability analysis of a fractional mathematical model of hand, foot, and mouth disease deals with the system’s long-term behavior over the entire state space, so it goes beyond the local neighborhood of equilibrium points. This is important because it explains whether the system will always end in a disease-free or endemic equilibrium, regardless of initial conditions. Specifically, the global stability analysis in fractional models is often carried out with a specially constructed Lyapunov function, where the analysis demonstrates that the system’s total energy or "distance" from equilibrium decays monotonically. This means that a model is globally stable with a Lyapunov function being positive definite and its fractional derivative along the trajectories of the system being negative definite. The existence of such a function would ensure global convergence to a stable equilibrium of the system; otherwise, it would spread uniformly in the population or die out. Thus, this analysis plays a vital role in the design of control strategies, giving information on how the system behaves regarding its robustness and interventions. Thus, the following theorem was obtained:

Theorem 10. The hand, foot, and mouth endemic equilibrium point, , is global asymptotically stable if .

Proof. Let

, then by Theorem (9) the Model (

1) has a unique disease-present equilibrium point,

. To proceed with the proof, we define the following Lyapunov function:

By taking the Caputo derivative for both sides of Equation (

10), we get:

Applying theorem (3) on Equation (

11), yields

Substituting the Caputo derivatives from Model (

1) into Equation (

12), we get:

Therefore,

Similarly, we will have the following:

Upon adding Equations (

13) to (16) and by the application of the Arithmetic-Geometric mean inequality, which is the geometric mean is less than or equal to the arithmetic mean, we conclude that

Therefore, by theorem (10), the hand, foot, and mouth endemic equilibrium point, , is globally asymptotically stable, and the proof is completed. □

6. Discussion and Numerical results

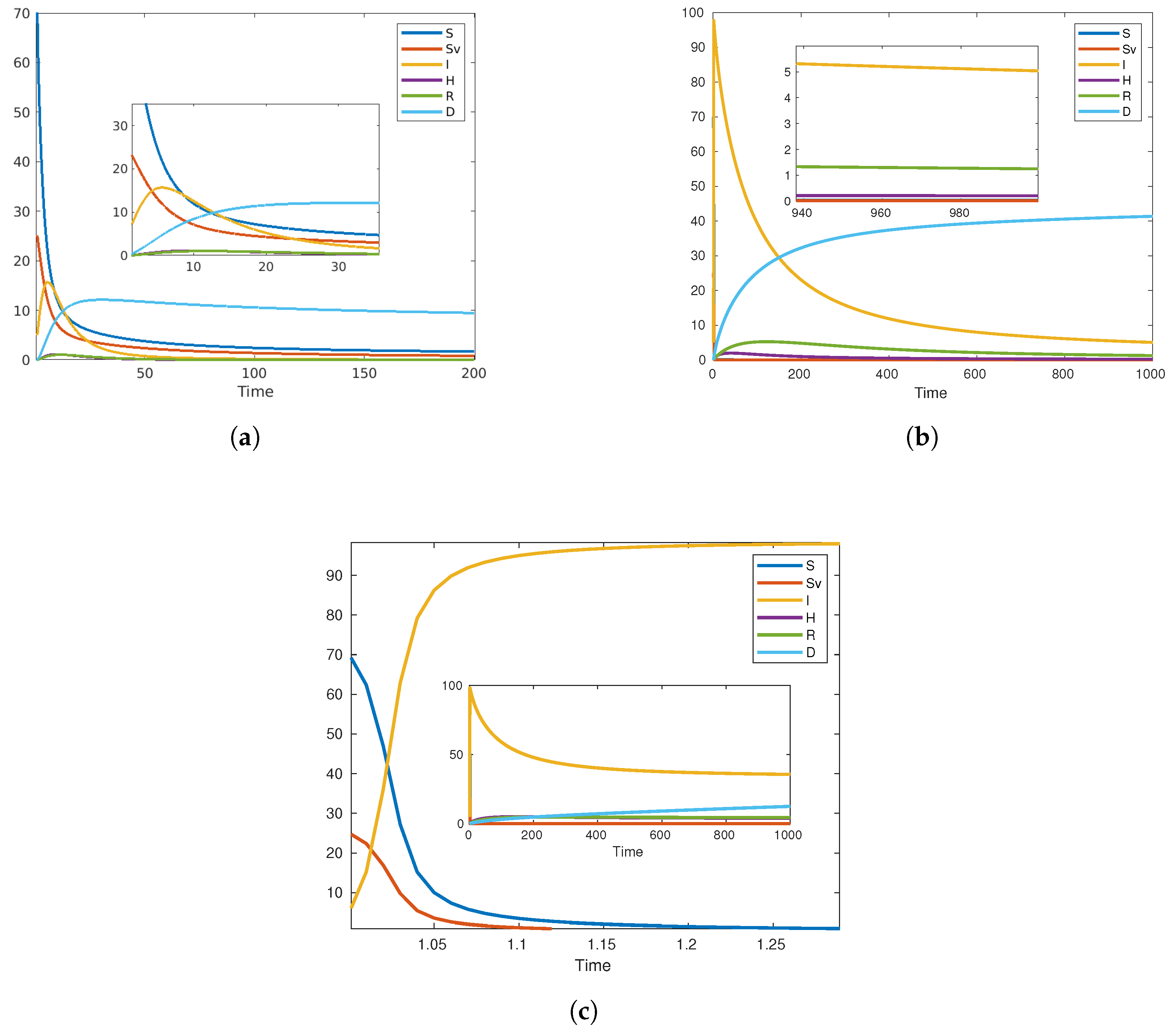

In this section, we validate the proposed model and the theorems presented in the previous section. Our results demonstrate the alignment between the theoretical analysis and the observed dynamics of both pandemic and endemic scenarios, particularly focusing on the reproduction number threshold. Using MATLAB, we simulate the model to visualize the results and analyze the sensitivity of the reproduction number. This allows us to observe the effects of various parameters on the spread of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD). The simulations provide insights into how changes in specific parameters can influence the disease dynamics, offering valuable information for effective disease management and control strategies.

Figure 2a,b showcases two scenarios of disease progression with varying levels of fractional derivatives—alpha at

and

, illustrating how changes in this parameter can impact the long-term behavior of an endemic illness. Each sub-figure represents a fractional derivative value, and an inset focuses on the long-term disease life cycle.

Figure 2c illustrates the dynamics of Foot, Hand, and Mouth Disease using an alpha fractional derivative of

. Notably, the basic reproduction number (

) is calculated to be

, which exceeds the threshold of 1, indicating pandemic potential. Additionally, the inset figure focuses on the long-term behavior of disease progression.

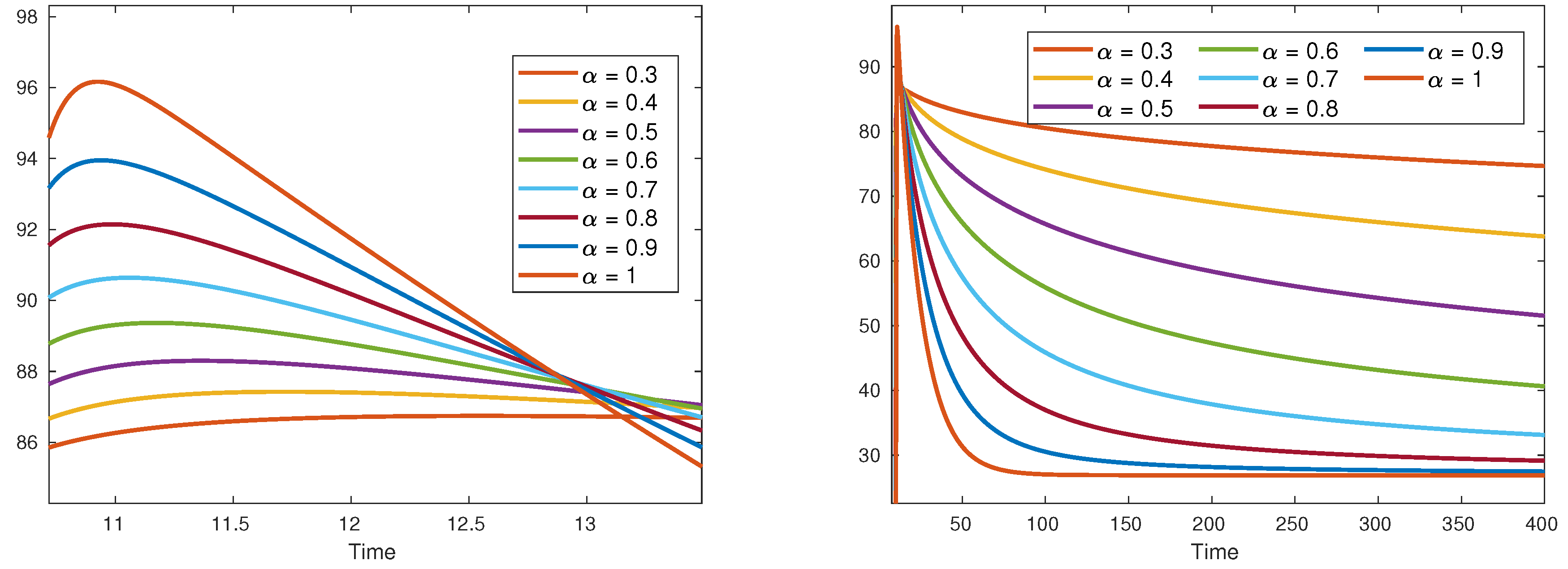

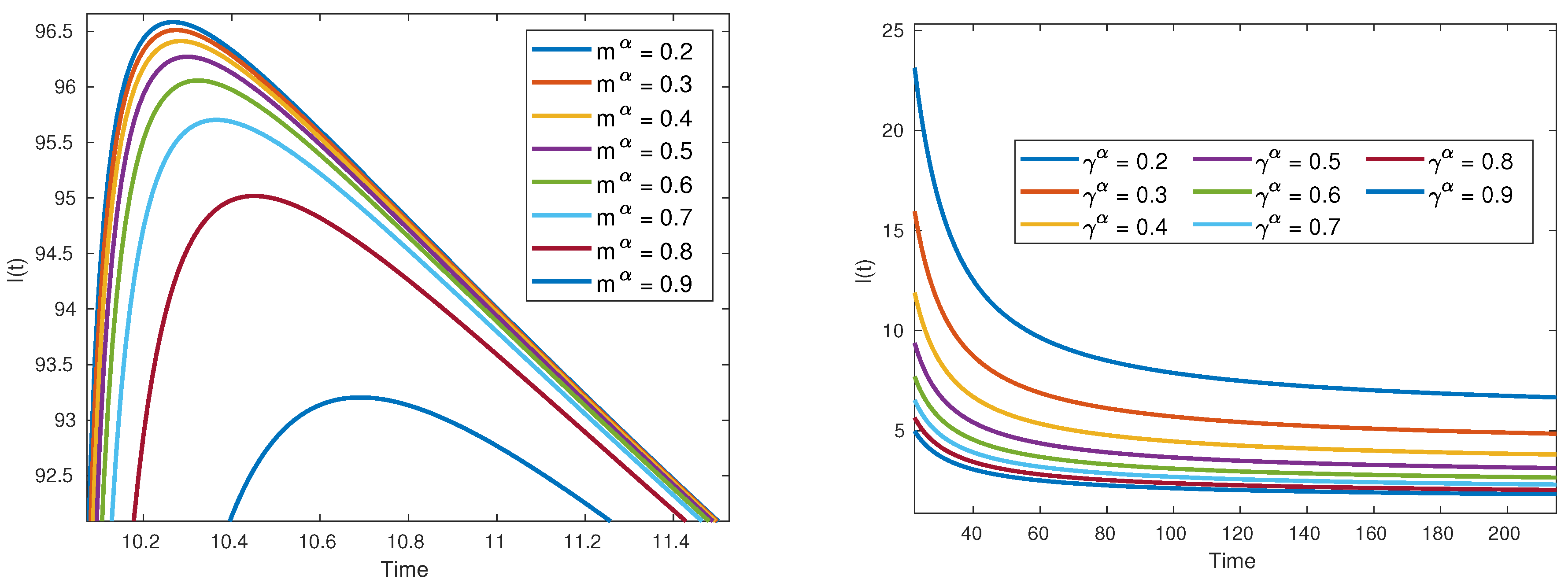

Figure 3 illustrates the dynamics of Foot, Hand, and Mouth Disease using varying alpha fractional derivatives. The left figure represents short-term trends, while the right figure focuses on long-term behavior. In the short term, infection cases peak around

, declining sharply with higher alpha values. In the long term, all infection cases are gradually decreased over time.

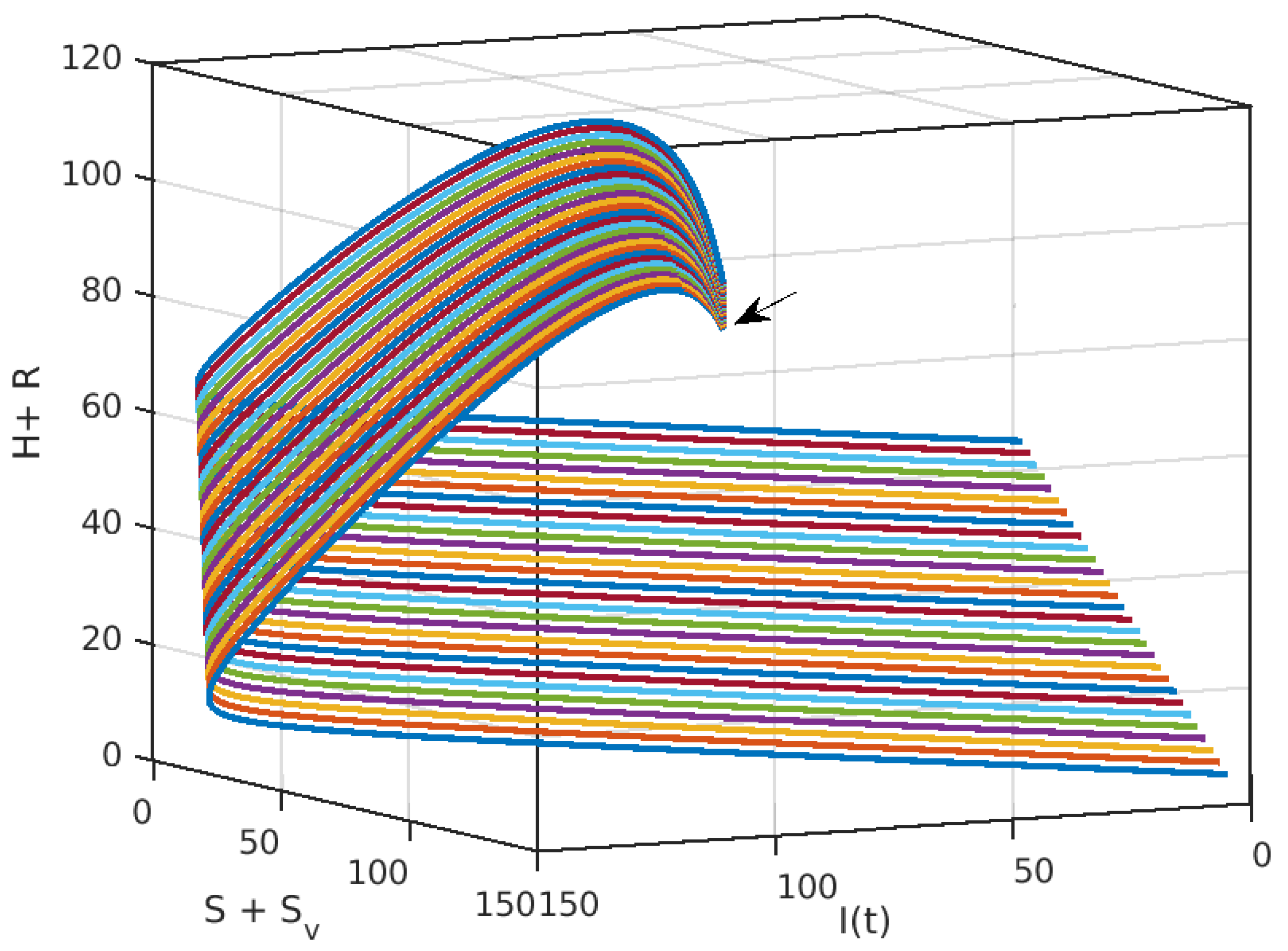

The three-dimensional

Figure 4 depicts the dynamics of Foot, Hand, and Mouth Disease using varying alpha fractional derivatives (specifically,

). The axes are labeled as x-axis:

(representing susceptible vaccinated individuals). y-axis:

(indicating the number of infected individuals over time). z-axis:

(likely referring to hospitalized plus recovered individuals). Notably, all trajectories converge to a common point during the pandemic. This convergence occurs regardless of initial conditions, emphasizing that any initial disease discovery eventually leads to a consistent outcome.

Figure 5 consists of two graphs related to Foot, Hand, and Mouth Disease dynamics. The right graph illustrates the impact of varying recovery rates (

) on infection cases, while the left graph focuses on vaccination efficiency (

m). Increasing recovery rates and vaccination efforts contribute to reducing infection cases and controlling disease spread.”

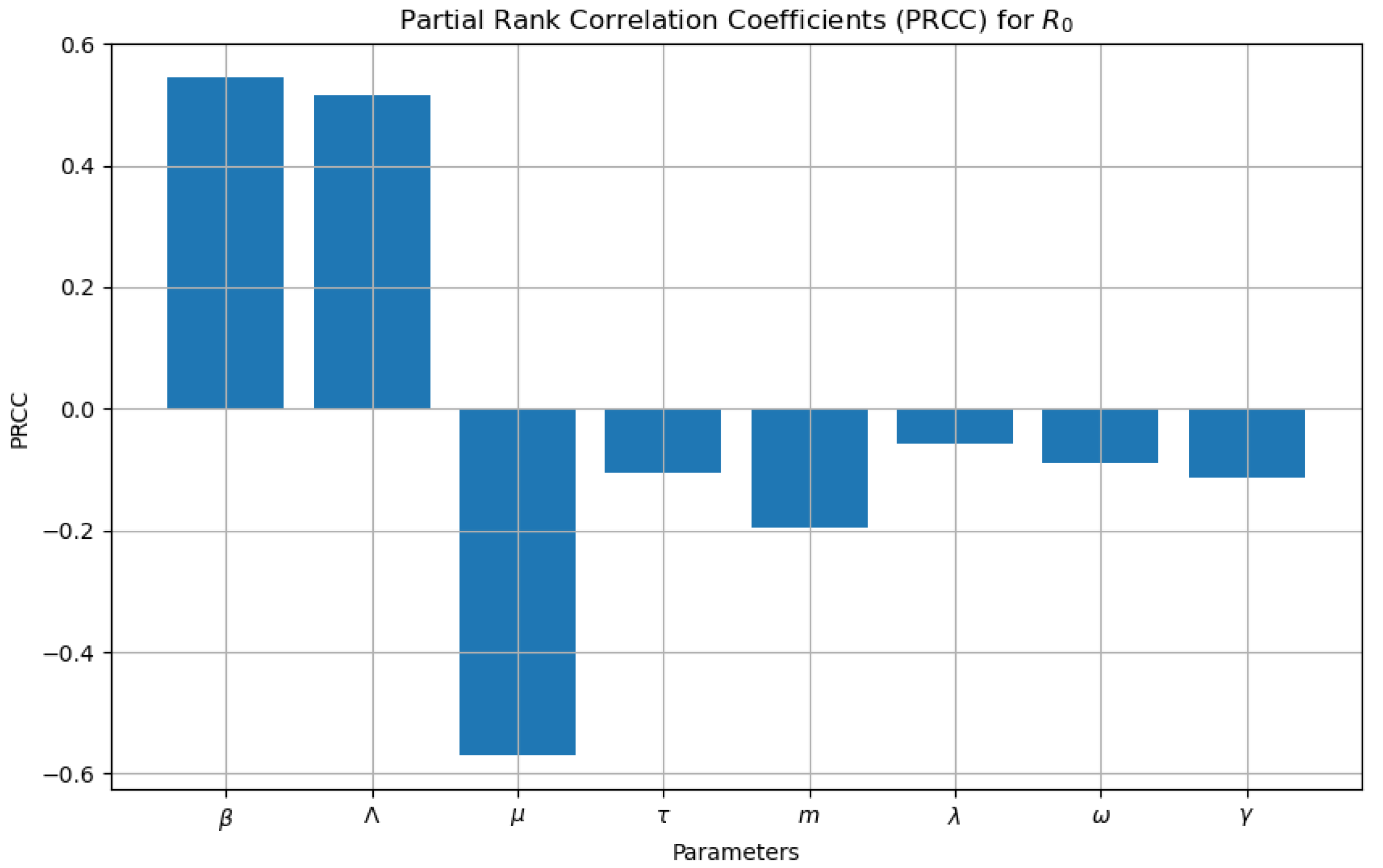

Figure 6 represents Partial Rank Correlation Coefficients (PRCC) for the basic reproduction number, denoted as

. The graph displays vertical bars above and below a horizontal axis (which represents zero). The bars above the axis indicate positive PRCC values, while those below represent negative PRCC values. Each bar is labeled with a different Greek letter or symbol (such as

,

,

,

,

m,

,

, and

). This visualization shows how different variables correlate with

when other variables are held constant. PRCC is relevant in fields like epidemiology, where

represents the basic reproduction number of an infection. It helps us understand how changes in specific factors impact disease spread. Our simulations validate the theoretical model, showing the importance of the reproduction number in HFMD dynamics. Sensitivity analysis reveals how parameter changes affect disease spread, aiding effective intervention strategies.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of vaccination on the transmission dynamics of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD) using a fractional-order derivative model. The mathematical analysis section established the proposed model’s existence, uniqueness, and stability. Numerical simulations, implemented using MATLAB, were conducted to validate the model’s behavior under various scenarios. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing disease prevalence. Sensitivity analysis using the Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) identified key parameters influencing disease transmission. Overall, this research provides valuable insights into the dynamics of HFMD and underscores the importance of vaccination strategies for disease control.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R518), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Klein, M.; Chong, P. Is a multivalent hand, foot, and mouth disease vaccine feasible? Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2015, 11, 2688–2704. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T.; Huang, Y.; Yu, S.; Gu, J.; Huang, C.; Xiao, G.; Hao, Y. Spatial-temporal clusters and risk factors of hand, foot, and mouth disease at the district level in Guangdong Province, China. PloS one 2013, 8, e56943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathyraj, S.; Arunkumar, G.; Alidjinou, E.; Hober, D. Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD): emerging epidemiology and the need for a vaccine strategy. Medical microbiology and immunology 2016, 205, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.L. Ecology and infectious disease. Ecosystem change and public health: a global perspective 2001, 283, 324. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovics, J.; Wilson, A.J.; Forbes, M.R.; Hauffe, H.C.; Kallio, E.R.; Leggett, H.C.; Longdon, B.; Okamura, B.; Sait, S.M.; Webster, J.P. The evolution of transmission mode. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 372, 20160083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.C.; DarAssi, M.H.; Alfwzan, W.F.; Khan, M.A.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alshahrani, S.S.; Muhammad, T. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 with vaccination using fractional derivative: a case study. Fractal and Fractional 2023, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DarAssi, M.H.; Safi, M.A. Analysis of an SIRS epidemic model for a disease geographic spread. Nonlinear Dynam. Syst. Theory 2021, 21, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- DarAssi, M.H.; Shatnawi, T.A.; Safi, M.A. Mathematical analysis of a MERS-Cov coronavirus model. Demonstratio Mathematica 2022, 55, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma. ; Yousaf, M.; Afzaal, M.; DarAssi, M.H.; Khan, M.A.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Suliman, M. A mathematical model of vaccinations using new fractional order derivative. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DarAssi, M.H.; Safi, M.A.; Ahmad, M. Global dynamics of a discrete-time MERS-Cov model. Mathematics 2021, 9, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DarAssi, M.H.; Ahmad, I.; Meetei, M.Z.; Alsulami, M.; Khan, M.A.; Tag-eldin, E.M. The impact of the face mask on SARS-CoV-2 disease: Mathematical modeling with a case study. Results in Physics 2023, 51, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DarAssi, M.H.; Damrah, S.; AbuHour, Y. A mathematical study of the omicron variant in a discrete-time Covid-19 model. The European Physical Journal Plus 2023, 138, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.U.A.; DarAssi, M.H.; Ahmad, I.; Assiri, T.A.; Meetei, M.Z.; Khan, M.A.; Hassan, A.M. Numerical simulation and analysis of the stochastic hiv/aids model in fractional order. Results in Physics 2023, 53, 106995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meetei, M.Z.; DarAssi, M.H.; Altaf Khan, M.; Koam, A.N.; Alzahrani, E.; Ali, H. Ahmadini, A. Analysis and simulation study of the HIV/AIDS model using the real cases. Plos one 2024, 19, e0304735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfwzan, W.F.; DarAssi, M.H.; Allehiany, F.; Khan, M.A.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Tag-eldin, E.M. A novel mathematical study to understand the Lumpy skin disease (LSD) using modified parameterized approach. Results in Physics 2023, 51, 106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubnv, I. Fractional differential equations academic press. San Diego, Boston 1999, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, M. Lectures on seismology and rheological tectonics; 1992.

- Samko, S.G. Fractional integrals and derivatives. Theory and applications 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and applications of fractional differential equations; Vol. 204, elsevier, 2006.

- Matignon, D. Stability results for fractional differential equations with applications to control processing. Computational engineering in systems applications. Citeseer, 1996, Vol. 2, pp. 963–968.

- Vargas-De-León, C. Volterra-type Lyapunov functions for fractional-order epidemic systems. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 2015, 24, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, H.; Baleanu, D.; Sadati, J. Stability analysis of Caputo fractional-order nonlinear systems revisited. Nonlinear Dynamics 2012, 67, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.M.; Bogich, T.; Siegel, K.; Jin, J.; Chong, E.Y.; Tan, C.Y.; Chen, M.I.; Horby, P.; Cook, A.R. The epidemiology of hand, foot and mouth disease in Asia: a systematic review and analysis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2016, 35, e285–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ou, R.; Zhu, H.; Gan, L.; Zeng, Z.; Yuan, R.; Yu, H.; Ye, M. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of severe hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) among children: a 6-year population-based study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; He, W.; Zheng, Z.; Pan, P.; Ju, Y.; Lu, Z.; Liao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; others. Factors related to the mortality risk of severe hand, foot, and mouth diseases (HFMD): a 5-year hospital-based survey in Guangxi, Southern China. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Xiong, Q.; Xie, B.; Wang, L.; Peng, Y.; Li, X. Risk factors for death from hand–foot–mouth disease: a meta-analysis. Epidemiology & Infection 2020, 148, e44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Xu, W.; Xia, J.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, L.; Mao, Q.; Wu, J.; others. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an enterovirus 71 vaccine in China. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 370, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.M.; Hernández, L.R. The theorem existence and uniqueness of the solution of a fractional differential equation. Acta Universitaria 2013, 23, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.; Roberts, M.G. The construction of next-generation matrices for compartmental epidemic models. Journal of the royal society interface 2010, 7, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical biosciences 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).