Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology of the Literature Search

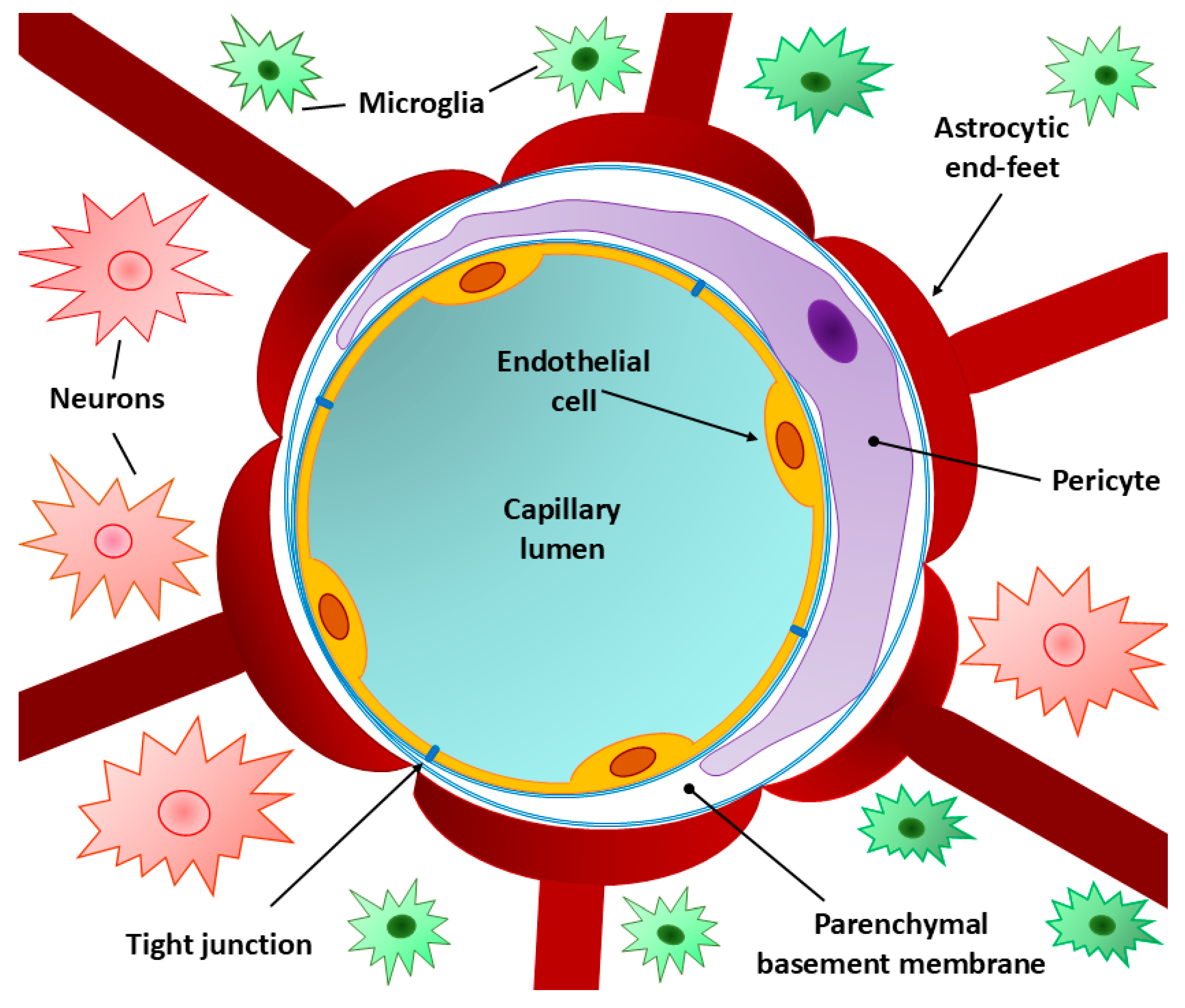

3. Normal BBB Structure

3.1. Endothelial Cells

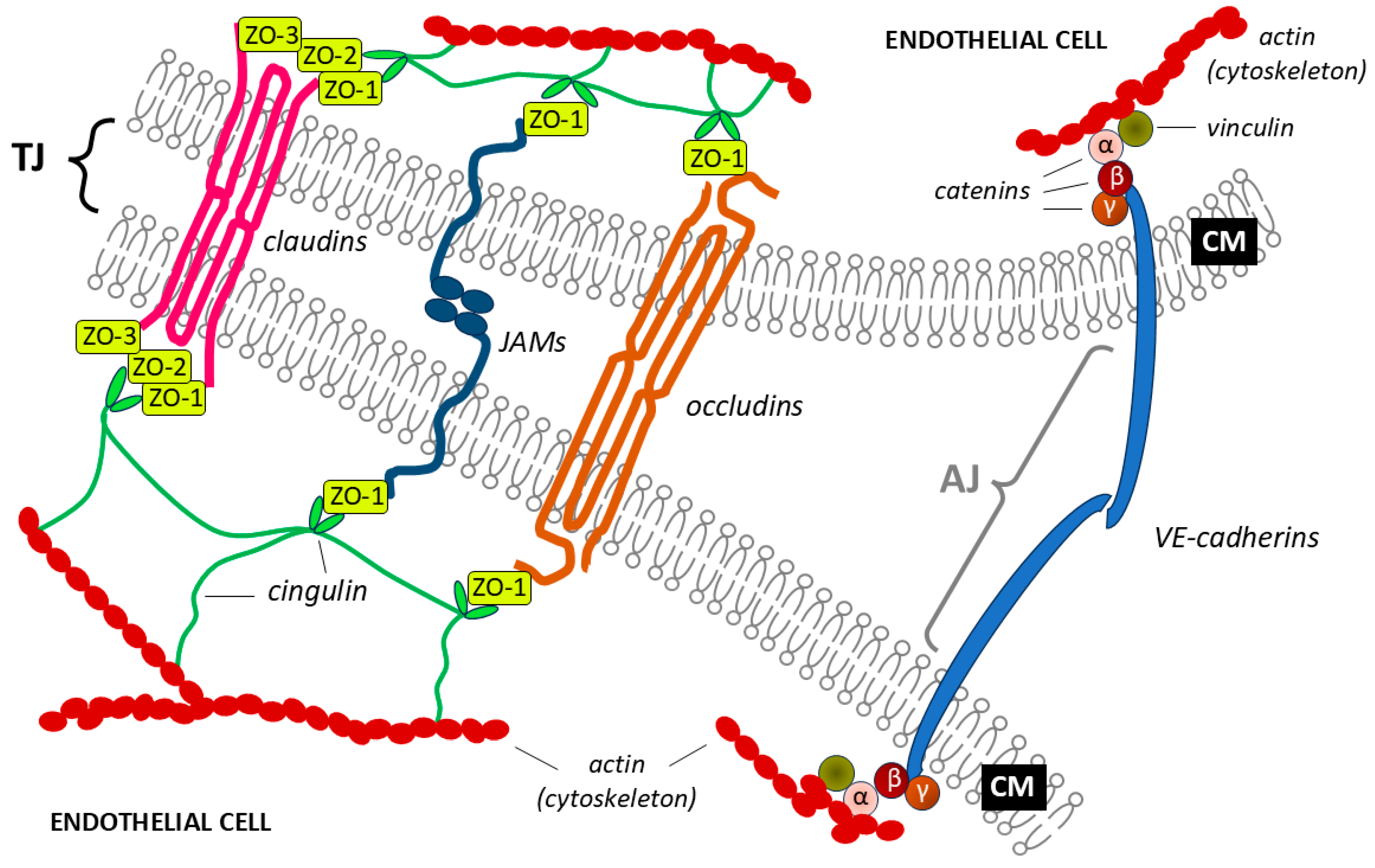

3.2. Tight Junctions

3.3. Pericytes

3.4. Basement Membrane

3.5. Perivascular Membrane

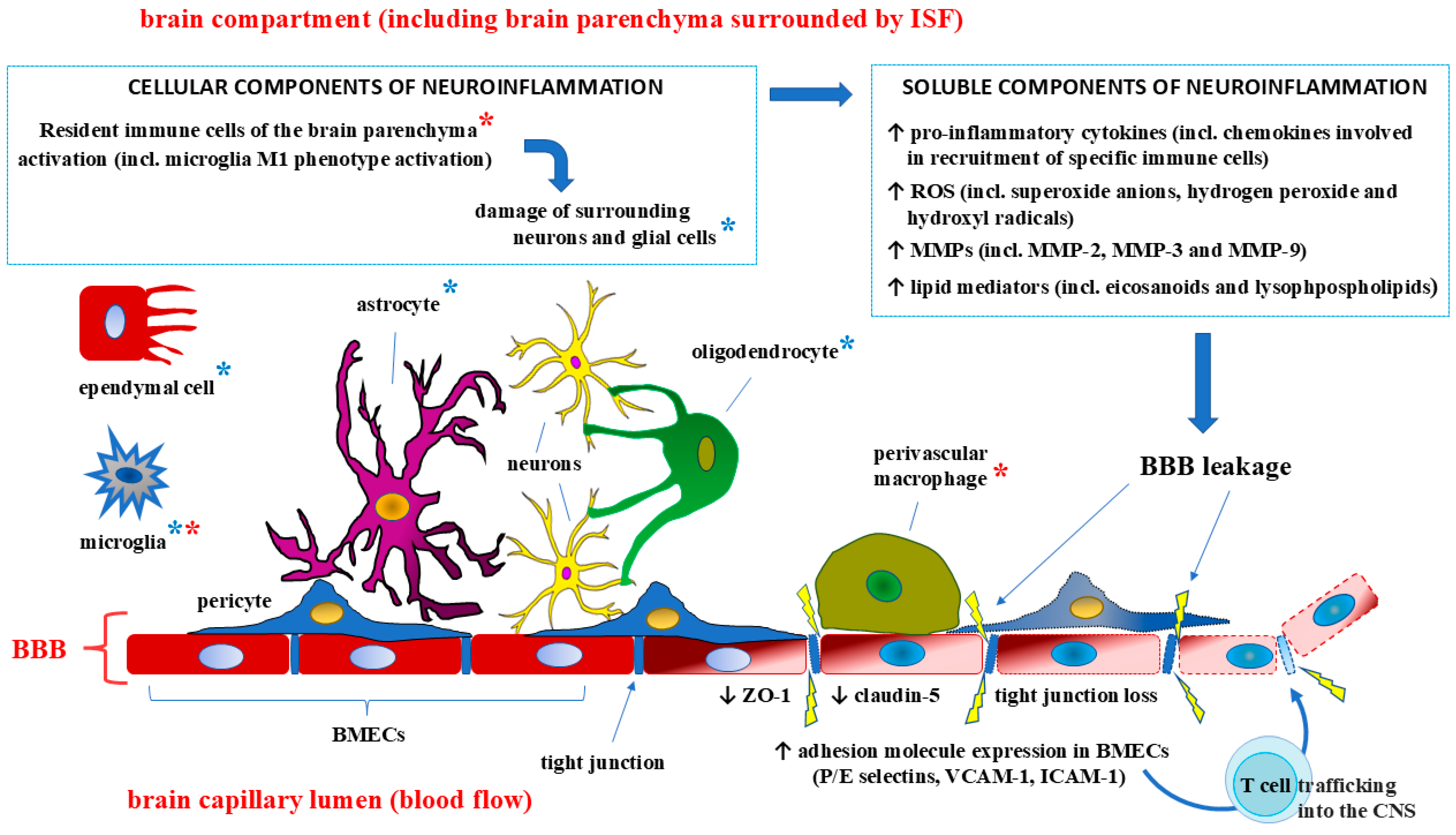

4. Influence of Proinflammatory Cytokines on the Disruption of the BBB Structure

5. Proinflammatory Cytokines Within the BBB: Clinical Approaches and Potential Therapies

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBB | blood‒brain barrier |

| BMECs | brain microvascular endothelial cells |

| CCL2 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 2, also known as monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) |

| CCL19 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 19, also known as macrophage inflammatory protein-3 beta (MIP-3β) |

| CCL20 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 |

| CCL21 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 21 |

| CD13 | cluster of differentiation 13, also known as aminopeptidase N (APN) or alanyl aminopeptidase |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CVOs | circumventricular organs |

| CX3CL1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1, also known as fractalkine |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12, also known as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) |

| e-τ | extracellular tau aggregates |

| GBM | glioblastoma multiforme |

| GLUT1 | glucose transporter 1 |

| HDC | histidine decarboxylase |

| HSPG | heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| ICAM-1 | intercellular adhesion molecule-1, also known as cluster of differentiation 54 (CD54) |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-1, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18 | interleukins: interleukin 1, interleukin 1-alpha, interleukin 1-beta, interleukin 2, interleukin 4, interleukin 6; interleukin 10, interleukin 12, interleukin 15, interleukin 17, interleukin 18, respectively |

| JAMs | junctional adhesion molecules |

| kDa | kilodalton (a non-SI unit of mass) |

| MAPT | microtubule-associated protein tau |

| MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9 | matrix metalloproteinases 2, 3 and 9, respectively |

| NGR-TNF | a drug created by fusing a peptide Cys-Asn-Gly-Arg-Cys-Gly (CNGRCG), denoted as NGR, with a TNF-α molecule |

| NK cells | natural killer cells |

| NMO-IgG | neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulin G |

| PCs | pericytes |

| P/E selectins | platelet/endothelial selectins, also known as CD62P/CD62E, respectively |

| RNAs | ribonucleic acids |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| S100B | S100 calcium-binding protein beta |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SHH | sonic hedgehog homolog (protein) |

| SIT | saturated influx transport |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| TIMP-1, TIMP-2 | tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 1 and 2, respectively |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TSP-2 | thrombospondin-2 |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, also known as cluster of differentiation 106 (CD106) |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 | zonula occludens proteins 1, 2, and 3, respectively |

References

- Dyrna F, Hanske S, Krueger M, Bechmann I. The blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013; 8(4):763-73. [CrossRef]

- Khan E. An examination of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(9):509-13. [CrossRef]

- Benz F, Liebner S. Structure and Function of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;273:3-31. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Byun HM, Chung EC, Chung HY, Bae ON. Loss of Integrity: Impairment of the Blood-brain Barrier in Heavy Metal-associated Ischemic Stroke. Toxicol Res. 2013;29(3):157-64. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Hawkins KE, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;316(2):C135-C153. [CrossRef]

- Takata F, Nakagawa S, Matsumoto J, Dohgu S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021; 15:661838. [CrossRef]

- Zhao B, Yin Q, Fei Y, Zhu J, Qiu Y, Fang W, Li Y. Research progress of mechanisms for tight junction damage on blood-brain barrier inflammation. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2022;128(6):1579-1590. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Cai Y, Zhang Z, Zhou J. Glial and Vascular Cell Regulation of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46(2):222-238. [CrossRef]

- Cai Z, Qiao PF, Wan CQ, Cai M, Zhou NK, Li Q. Role of Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(4):1223-1234. [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos D, Manolakou T, Polissidis A, Filia A, Bertsias G, Koutmani Y, Boumpas DT. Microglia activation in the presence of intact blood-brain barrier and disruption of hippocampal neurogenesis via IL-6 and IL-18 mediate early diffuse neuropsychiatric lupus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(5):646-657. [CrossRef]

- Wątroba M, Grabowska AD, Szukiewicz D. Effects of Diabetes Mellitus-Related Dysglycemia on the Functions of Blood-Brain Barrier and the Risk of Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):10069. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Li G, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yao L, Wang F, Liu S, Yin J, Ling EA, Wang L, Hao A. High glucose-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species in cultured astrocytes. Neuroscience. 2012;202:58-68. [CrossRef]

- Lesniak A, Poznański P, Religa P, Nawrocka A, Bujalska-Zadrozny M, Sacharczuk M. Loss of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Resulting From Congenital- Or Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Correlates With Depressive-Like Behaviour. Neuroscience. 2021;458:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Małkiewicz MA, Małecki A, Toborek M, Szarmach A, Winklewski PJ. Substances of abuse and the blood brain barrier: Interactions with physical exercise. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;119:204-216. [CrossRef]

- Bronisz E, Cudna A, Wierzbicka A, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I. Blood-Brain Barrier-Associated Proteins Are Elevated in Serum of Epilepsy Patients. Cells. 2023;12(3):368. [CrossRef]

- Łach A, Wnuk A, Wójtowicz AK. Experimental Models to Study the Functions of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023;10(5):519. [CrossRef]

- Patel JP, Frey BN. Disruption in the Blood-Brain Barrier: The Missing Link between Brain and Body Inflammation in Bipolar Disorder? Neural Plast. 2015;2015:708306. [CrossRef]

- Yarlagadda A, Alfson E, Clayton AH. The blood brain barrier and the role of cytokines in neuropsychiatry. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(11):18-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 2801.

- Haley MJ, Lawrence CB. The blood-brain barrier after stroke: Structural studies and the role of transcytotic vesicles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(2):456-470. [CrossRef]

- Mayer MG, Fischer T. Microglia at the blood brain barrier in health and disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024;18:1360195. [CrossRef]

- Lim SH, Yee GT, Khang D. Nanoparticle-Based Combinational Strategies for Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier and Blood-Tumor Barrier. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024;19:2529-2552. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y. The blood-brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):217. [CrossRef]

- McCabe SM, Zhao N. The Potential Roles of Blood-Brain Barrier and Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier in Maintaining Brain Manganese Homeostasis. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):1833. [CrossRef]

- Patabendige A, Janigro D. The role of the blood-brain barrier during neurological disease and infection. Biochem Soc Trans. 2023;51(2):613-626. [CrossRef]

- Dotiwala AK, McCausland C, Samra NS. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Blood Brain Barrier. [Updated 2023 Apr 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5195.

- Ganong WF. Circumventricular organs: definition and role in the regulation of endocrine and autonomic function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27(5-6):422-7. [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky A, Pivoriūnas A. Astroglia support, regulate and reinforce brain barriers. Neurobiol Dis. 2023;179:106054. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Nirwane A, Yao Y. Basement membrane and blood-brain barrier. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2018; 4(2):78-82. [CrossRef]

- Erickson MA, Banks WA. Transcellular routes of blood-brain barrier disruption. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2022;247(9):788-796. [CrossRef]

- Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Haorah J, Kanmogne GD. Blood-brain barrier: structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1(3):223-36. [CrossRef]

- Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Apr;1788(4):842-57. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, He L, Lugano R, Zhang Y, Cao H, He Q, Chao M, Liu B, Cao Q, Wang J, Jiao Y, Hu Y, Han L, Zhang Y, Huang H, Uhrbom L, Betsholtz C, Wang L, Dimberg A, Zhang L. Key molecular alterations in endothelial cells in human glioblastoma uncovered through single-cell RNA sequencing. JCI Insight. 2021;6(15):e150861. [CrossRef]

- Langen UH, Ayloo S, Gu C. Development and Cell Biology of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2019;35:591-613. [CrossRef]

- Ozgür B, Helms HCC, Tornabene E, Brodin B. Hypoxia increases expression of selected blood-brain barrier transporters GLUT-1, P-gp, SLC7A5 and TFRC, while maintaining barrier integrity, in brain capillary endothelial monolayers. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022;19(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick S, D'Mello V, Caruso D, Wallerstein A, Abdul-Muneer PM. Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2019;317:260-270. [CrossRef]

- Kakava S, Schlumpf E, Panteloglou G, Tellenbach F, von Eckardstein A, Robert J. Brain Endothelial Cells in Contrary to the Aortic Do Not Transport but Degrade Low-Density Lipoproteins via Both LDLR and ALK1. Cells. 2022;11(19):3044. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Zhong L, Luo Y. Endothelial glycocalyx as an important factor in composition of blood-brain barrier. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(1):26-35. Erratum in: CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27(7):862. [CrossRef]

- Kadry H, Noorani B, Cucullo L. A blood-brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2020;17(1):69. [CrossRef]

- Kniesel U, Wolburg H. Tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20(1): 57-76. [CrossRef]

- Feng S, Zou L, Wang H, He R, Liu K, Zhu H. RhoA/ROCK-2 Pathway Inhibition and Tight Junction Protein Upregulation by Catalpol Suppresses Lipopolysaccaride-Induced Disruption of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability. Molecules. 2018;23(9):2371. [CrossRef]

- Haseloff RF, Dithmer S, Winkler L, Wolburg H, Blasig IE. Transmembrane proteins of the tight junctions at the blood-brain barrier: structural and functional aspects. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015; 38:16-25. [CrossRef]

- Koumangoye R, Penny P, Delpire E. Loss of NKCC1 function increases epithelial tight junction permeability by upregulating claudin-2 expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;323(4):C1251-C1263. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto TM, Webb PG, Davis DM, Baumgartner HK, Woodruff ER, Guntupalli SR, Neville M, Behbakht K, Bitler BG. Loss of Claudin-4 Reduces DNA Damage Repair and Increases Sensitivity to PARP Inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21(4):647-657. [CrossRef]

- Kim NY, Pyo JS, Kang DW, Yoo SM. Loss of claudin-1 expression induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through nuclear factor-κB activation in colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(3):580-585. [CrossRef]

- Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Claudin-5: gatekeeper of neurological function. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2019;16(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Günzel D, Fromm M. Claudins and other tight junction proteins. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(3):1819-52. [CrossRef]

- Komarova YA, Kruse K, Mehta D, Malik AB. Protein Interactions at Endothelial Junctions and Signaling Mechanisms Regulating Endothelial Permeability. Circ Res. 2017;120(1):179-206. [CrossRef]

- Liu WY, Wang ZB, Zhang LC, Wei X, Li L. Tight junction in blood-brain barrier: an overview of structure, regulation, and regulator substances. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(8):609-15. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann S, Lawler SE, Qu Y, Fadzen CM, Wolfe JM, Regan MS, Pentelute BL, Agar NYR, Cho CF. Blood-brain-barrier organoids for investigating the permeability of CNS therapeutics. Nat Protoc. 2018;13(12):2827-2843. [CrossRef]

- Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778(3):660-9. [CrossRef]

- Kuo WT, Odenwald MA, Turner JR, Zuo L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2022;1514(1):21-33. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Huang X, Su Y, Yin G, Wang S, Yu B, Li H, Qi J, Chen H, Zeng W, Zhang K, Verkhratsky A, Niu J, Yi C. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway mitigates blood-brain barrier dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2022;145(12):4474-4488. [CrossRef]

- Liebner S, Gerhardt H, Wolburg H. Differential expression of endothelial beta-catenin and plakoglobin during development and maturation of the blood-brain and blood-retina barrier in the chicken. Dev Dyn. 2000;217(1):86-98. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Martinez L, Yemisci M, Dalkara T. Pericyte morphology and function. Histol Histopathol. 2021;36(6):633-643. [CrossRef]

- Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97(6):512-23. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead B, Karelina K, Weil ZM. Pericyte dysfunction is a key mediator of the risk of cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2023;101(12):1840-1848. [CrossRef]

- Kamouchi M, Ago T, Kitazono T. Brain pericytes: emerging concepts and functional roles in brain homeostasis. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31(2):175-93. [CrossRef]

- Sá-Pereira I, Brites D, Brito MA. Neurovascular unit: a focus on pericytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2012; 45(2):327-47. [CrossRef]

- Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010; 468(7323):557-61. [CrossRef]

- Dudvarski Stankovic N, Teodorczyk M, Ploen R, Zipp F, Schmidt MHH. Microglia-blood vessel interactions: a double-edged sword in brain pathologies. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(3):347-63. [CrossRef]

- Fu J, Liang H, Yuan P, Wei Z, Zhong P. Brain pericyte biology: from physiopathological mechanisms to potential therapeutic applications in ischemic stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1267785. [CrossRef]

- Su X, Huang L, Qu Y, Xiao D, Mu D. Pericytes in Cerebrovascular Diseases: An Emerging Therapeutic Target. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:519. [CrossRef]

- Brown LS, Foster CG, Courtney JM, King NE, Howells DW, Sutherland BA. Pericytes and Neurovascular Function in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:282. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Yang Y, Fan X. Microvascular pericytes in brain-associated vascular disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109633. [CrossRef]

- Anwar MM, Özkan E, Gürsoy-Özdemir Y. The role of extracellular matrix alterations in mediating astrocyte damage and pericyte dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: A comprehensive review. Eur J Neurosci. 2022;56(9):5453-5475. [CrossRef]

- Rivera FJ, Hinrichsen B, Silva ME. Pericytes in Multiple Sclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1147:167-187. [CrossRef]

- Benarroch E. What Are the Roles of Pericytes in the Neurovascular Unit and Its Disorders? Neurology. 2023;100(20):970-977. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon DG, Long D, Kim WK. Understanding the Heterogeneity of Human Pericyte Subsets in Blood-Brain Barrier Homeostasis and Neurological Diseases. Cells. 2021;10(4):890. [CrossRef]

- Nwadozi E, Rudnicki M, Haas TL. Metabolic Coordination of Pericyte Phenotypes: Therapeutic Implications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:77. [CrossRef]

- Khalilgharibi N, Mao Y. To form and function: on the role of basement membrane mechanics in tissue development, homeostasis and disease. Open Biol. 2021;11(2):200360. [CrossRef]

- Halder SK, Sapkota A, Milner R. The importance of laminin at the blood-brain barrier. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18(12):2557-2563. [CrossRef]

- Boudko SP, Danylevych N, Hudson BG, Pedchenko VK. Basement membrane collagen IV: Isolation of functional domains. Methods Cell Biol. 2018;143:171-185. [CrossRef]

- Biswas S, Bachay G, Chu J, Hunter DD, Brunken WJ. Laminin-Dependent Interaction between Astrocytes and Microglia: A Role in Retinal Angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2017;187(9):2112-2127. [CrossRef]

- Gautam J, Zhang X, Yao Y. The role of pericytic laminin in blood brain barrier integrity maintenance. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36450. [CrossRef]

- Töpfer U, Holz A. Nidogen in development and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1380542. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen MS, Routhe LJ, Moos T. The vascular basement membrane in the healthy and pathological brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(10):3300-3317. [CrossRef]

- Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood-brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282(21):4067-79. [CrossRef]

- Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(1):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Töpfer, U. Basement membrane dynamics and mechanics in tissue morphogenesis. Biol Open. 2023;12(8):bio059980. [CrossRef]

- Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(5):311-21. [CrossRef]

- Fong H, Zhou B, Feng H, Luo C, Bai B, Zhang J, Wang Y. Recapitulation of Structure-Function-Regulation of Blood-Brain Barrier under (Patho)Physiological Conditions. Cells. 2024;13(3):260. [CrossRef]

- Manu DR, Slevin M, Barcutean L, Forro T, Boghitoiu T, Balasa R. Astrocyte Involvement in Blood-Brain Barrier Function: A Critical Update Highlighting Novel, Complex, Neurovascular Interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(24):17146. [CrossRef]

- Schiera G, Di Liegro CM, Schirò G, Sorbello G, Di Liegro I. Involvement of Astrocytes in the Formation, Maintenance, and Function of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Cells. 2024;13(2):150. [CrossRef]

- Naveed M, Zhou QG, Han F. Cerebrovascular inflammation: A critical trigger for neurovascular injury? Neurochem Int. 2019;126:165-177. [CrossRef]

- Quan N. Immune-to-brain signaling: how important are the blood-brain barrier-independent pathways? Mol Neurobiol. 2008;37(2-3):142-52. [CrossRef]

- Miyata S. Glial functions in the blood-brain communication at the circumventricular organs. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:991779. [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj A, Galea I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2017; 60:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Ran M, Li H, Lin Y, Ma K, Yang Y, Fu X, Yang S. New insight into neurological degeneration: Inflammatory cytokines and blood-brain barrier. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022;15:1013933. [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff RM, Schafer D, Vincent A, Blachère NE, Bar-Or A. Neuroinflammation: Ways in Which the Immune System Affects the Brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(4):896-909. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh G, MacLean AG, Philipp MT. Cytokines and chemokines at the crossroads of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:480739. [CrossRef]

- Liu LR, Liu JC, Bao JS, Bai QQ, Wang GQ. Interaction of Microglia and Astrocytes in the Neurovascular Unit. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1024. [CrossRef]

- Rawat M, Nighot M, Al-Sadi R, Gupta Y, Viszwapriya D, Yochum G, Koltun W, Ma TY. IL1B Increases Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability by Up-regulation of MIR200C-3p, Which Degrades Occludin mRNA. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(4):1375-1389. [CrossRef]

- Versele R, Sevin E, Gosselet F, Fenart L, Candela P. TNF-α and IL-1β Modulate Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability and Decrease Amyloid-β Peptide Efflux in a Human Blood-Brain Barrier Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10235. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko N, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Morikawa S, Masumoto J. The role of interleukin-1 in general pathology. Inflamm Regen. 2019;39:12. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Jin S, Sonobe Y, Cheng Y, Horiuchi H, Parajuli B, Kawanokuchi J, Mizuno T, Takeuchi H, Suzumura A. Interleukin-1β induces blood-brain barrier disruption by downregulating Sonic hedgehog in astrocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110024. [CrossRef]

- Gajtkó A, Bakk E, Hegedűs K, Ducza L, Holló K. IL-1β Induced Cytokine Expression by Spinal Astrocytes Can Play a Role in the Maintenance of Chronic Inflammatory Pain. Front Physiol. 2020; 11:543331. [CrossRef]

- Sjöström EO, Culot M, Leickt L, Åstrand M, Nordling E, Gosselet F, Kaiser C. Transport study of interleukin-1 inhibitors using a human in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100307. [CrossRef]

- Fahey E, Doyle SL. IL-1 Family Cytokine Regulation of Vascular Permeability and Angiogenesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1426. [CrossRef]

- Souza PS, Gonçalves ED, Pedroso GS, Farias HR, Junqueira SC, Marcon R, Tuon T, Cola M, Silveira PCL, Santos AR, Calixto JB, Souza CT, de Pinho RA, Dutra RC. Physical Exercise Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Inhibiting Peripheral Immune Response and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(6):4723-4737. [CrossRef]

- Balzano T, Dadsetan S, Forteza J, Cabrera-Pastor A, Taoro-Gonzalez L, Malaguarnera M, Gil-Perotin S, Cubas-Nuñez L, Casanova B, Castro-Quintas A, Ponce-Mora A, Arenas YM, Leone P, Erceg S, Llansola M, Felipo V. Chronic hyperammonemia induces peripheral inflammation that leads to cognitive impairment in rats: Reversed by anti-TNF-α treatment. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3):582-592. [CrossRef]

- Wylezinski LS, Hawiger J. Interleukin 2 Activates Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Resulting in Destabilization of Adherens Junctions. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(44):22913-22923. [CrossRef]

- Waguespack PJ, Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Interleukin-2 does not cross the blood-brain barrier by a saturable transport system. Brain Res Bull. 1994;34(2):103-9. [CrossRef]

- Gao W, Li F, Zhou Z, Xu X, Wu Y, Zhou S, Yin D, Sun D, Xiong J, Jiang R, Zhang J. IL-2/Anti-IL-2 Complex Attenuates Inflammation and BBB Disruption in Mice Subjected to Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurol. 2017;8:281. [CrossRef]

- Yshii L, Pasciuto E, Bielefeld P, Mascali L, Lemaitre P, Marino M, Dooley J, Kouser L, Verschoren S, Lagou V, Kemps H, Gervois P, de Boer A, Burton OT, Wahis J, Verhaert J, Tareen SHK, Roca CP, Singh K, Whyte CE, Kerstens A, Callaerts-Vegh Z, Poovathingal S, Prezzemolo T, Wierda K, Dashwood A, Xie J, Van Wonterghem E, Creemers E, Aloulou M, Gsell W, Abiega O, Munck S, Vandenbroucke RE, Bronckaers A, Lemmens R, De Strooper B, Van Den Bosch L, Himmelreich U, Fitzsimons CP, Holt MG, Liston A. Astrocyte-targeted gene delivery of interleukin 2 specifically increases brain-resident regulatory T cell numbers and protects against pathological neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol. 2022; 23(6):878-891. [CrossRef]

- Furutama D, Matsuda S, Yamawaki Y, Hatano S, Okanobu A, Memida T, Oue H, Fujita T, Ouhara K, Kajiya M, Mizuno N, Kanematsu T, Tsuga K, Kurihara H. IL-6 Induced by Periodontal Inflammation Causes Neuroinflammation and Disrupts the Blood-Brain Barrier. Brain Sci. 2020;10(10):679. [CrossRef]

- Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(5):878-88. [CrossRef]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Broadwell RD. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1995;2(4):241-8. [CrossRef]

- Natesh K, Bhosale D, Desai A, Chandrika G, Pujari R, Jagtap J, Chugh A, Ranade D, Shastry P. Oncostatin-M differentially regulates mesenchymal and proneural signature genes in gliomas via STAT3 signaling. Neoplasia. 2015;17(2):225-37. [CrossRef]

- Serna-Rodríguez MF, Bernal-Vega S, de la Barquera JAO, Camacho-Morales A, Pérez-Maya AA. The role of damage associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs) and permeability of the blood-brain barrier in depression and neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;371:577951. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Tian Y, Wei J, Xiang Y. Relationship of Serum IL-12 to Inflammation, Hematoma Volume, and Prognosis in Patients With Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Emerg Med Int. 2022;2022:8688413. [CrossRef]

- Andreadou M, Ingelfinger F, De Feo D, Cramer TLM, Tuzlak S, Friebel E, Schreiner B, Eede P, Schneeberger S, Geesdorf M, Ridder F, Welsh CA, Power L, Kirschenbaum D, Tyagarajan SK, Greter M, Heppner FL, Mundt S, Becher B. IL-12 sensing in neurons induces neuroprotective CNS tissue adaptation and attenuates neuroinflammation in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26(10):1701-1712. [CrossRef]

- Pan W, Wu X, He Y, Hsuchou H, Huang EY, Mishra PK, Kastin AJ. Brain interleukin-15 in neuroinflammation and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(2):184-92. [CrossRef]

- Pan W, Hsuchou H, Yu C, Kastin AJ. Permeation of blood-borne IL15 across the blood-brain barrier and the effect of LPS. J Neurochem. 2008;106(1):313-9. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Han J, Ren H, Ma CG, Shi FD, Liu Q, Li M. Astrocytic Interleukin-15 Reduces Pathology of Neuromyelitis Optica in Mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:523. [CrossRef]

- Burrack KS, Huggins MA, Taras E, Dougherty P, Henzler CM, Yang R, Alter S, Jeng EK, Wong HC, Felices M, Cichocki F, Miller JS, Hart GT, Johnson AJ, Jameson SC, Hamilton SE. Interleukin-15 Complex Treatment Protects Mice from Cerebral Malaria by Inducing Interleukin-10-Producing Natural Killer Cells. Immunity. 2018;48(4):760-772.e4. [CrossRef]

- Huppert J, Closhen D, Croxford A, White R, Kulig P, Pietrowski E, Bechmann I, Becher B, Luhmann HJ, Waisman A, Kuhlmann CR. Cellular mechanisms of IL-17-induced blood-brain barrier disruption. FASEB J. 2010;24(4):1023-34. [CrossRef]

- Jung HK, Ryu HJ, Kim MJ, Kim WI, Choi HK, Choi HC, Song HK, Jo SM, Kang TC. Interleukin-18 attenuates disruption of brain-blood barrier induced by status epilepticus within the rat piriform cortex in interferon-γ independent pathway. Brain Res. 2012;1447:126-34. [CrossRef]

- Clark PR, Kim RK, Pober JS, Kluger MS. Tumor necrosis factor disrupts claudin-5 endothelial tight junction barriers in two distinct NF-κB-dependent phases. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120075. [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Basset EM, Rao MS, Alshawaf SM, Ashkanani HK, Kabli AH. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) induces astrogliosis, microgliosis and promotes survival of cortical neurons. AIMS Neurosci. 2021;8(4):558-584. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad M. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha: A Major Cytokine of Brain Neuroinflammation [Internet]. Cytokines. IntechOpen; 2020. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Chen AQ, Fang Z, Chen XL, Yang S, Zhou YF, Mao L, Xia YP, Jin HJ, Li YN, You MF, Wang XX, Lei H, He QW, Hu B. Microglia-derived TNF-α mediates endothelial necroptosis aggravating blood brain-barrier disruption after ischemic stroke. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(7):487. [CrossRef]

- Han EC, Choi SY, Lee Y, Park JW, Hong SH, Lee HJ. Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-α production in human macrophages and cross the blood-brain barrier in mice. FASEB J. 2019;33(12):13412-13422. [CrossRef]

- Ng CT, Fong LY, Abdullah MNH. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ): Reviewing its mechanisms and signaling pathways on the regulation of endothelial barrier function. Cytokine. 2023;166:156208. [CrossRef]

- Sonar SA, Shaikh S, Joshi N, Atre AN, Lal G. IFN-γ promotes transendothelial migration of CD4+ T cells across the blood-brain barrier. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95(9):843-853. [CrossRef]

- Youakim A, Ahdieh M. Interferon-gamma decreases barrier function in T84 cells by reducing ZO-1 levels and disrupting apical actin. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5):G1279-88. [CrossRef]

- Rahman MT, Ghosh C, Hossain M, Linfield D, Rezaee F, Janigro D, Marchi N, van Boxel-Dezaire AHH. IFN-γ, IL-17A, or zonulin rapidly increase the permeability of the blood-brain and small intestinal epithelial barriers: Relevance for neuro-inflammatory diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018; 507(1-4):274-279. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Xiao D, Mao Q, Xia H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):267. [CrossRef]

- Rochfort KD, Cummins PM. The blood-brain barrier endothelium: a target for pro-inflammatory cytokines. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(4):702-6. [CrossRef]

- Lee JI, Choi JH, Kwon TW, Jo HS, Kim DG, Ko SG, Song GJ, Cho IH. Neuroprotective effects of bornyl acetate on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via anti-inflammatory effects and maintaining blood-brain-barrier integrity. Phytomedicine. 2023;112:154569. [CrossRef]

- Pawluk H, Woźniak A, Grześk G, Kołodziejska R, Kozakiewicz M, Kopkowska E, Grzechowiak E, Kozera G. The Role of Selected Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Pathogenesis of Ischemic Stroke. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:469-484. [CrossRef]

- Soltani Khaboushan A, Yazdanpanah N, Rezaei N. Neuroinflammation and Proinflammatory Cytokines in Epileptogenesis. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59(3):1724-1743. [CrossRef]

- Granata T, Fusco L, Matricardi S, Tozzo A, Janigro D, Nabbout R. Inflammation in pediatric epilepsies: Update on clinical features and treatment options. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;131(Pt B):107959. [CrossRef]

- Savotchenko А. В. Blood-brain barrier disfunction and development of epileptic seizures: According to the materials of scientific report at the meeting of the Presidium of the NAS of Ukraine, December 23, 2020. Visn. Nac. Akad. Nauk Ukr. 2021;1:53–61. [CrossRef]

- Kamali AN, Zian Z, Bautista JM, Hamedifar H, Hossein-Khannazer N, Hosseinzadeh R, Yazdani R, Azizi G. The Potential Role of Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Epilepsy Pathogenesis. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(10):1760-1774. [CrossRef]

- Martin SP, Leeman-Markowski BA. Proposed mechanisms of tau: relationships to traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2024;14:1287545. [CrossRef]

- Langerscheidt F, Wied T, Al Kabbani MA, van Eimeren T, Wunderlich G, Zempel H. Genetic forms of tauopathies: inherited causes and implications of Alzheimer's disease-like TAU pathology in primary and secondary tauopathies. J Neurol. 2024 Mar 30. [CrossRef]

- Michalicova A, Majerova P, Kovac A. Tau Protein and Its Role in Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:570045. [CrossRef]

- Diener HC, Gaul C, Holle-Lee D, Jürgens TP, Kraya T, Kurth T, Nägel S, Neeb L, Straube A. Kopfschmerzen – Update 2018 [Headache - an Update 2018]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2019;98(3):192-217. German. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Ding J, Wang X, Gu C, He Y, Li Y, Fan H, Xie Q, Qi X, Wang Z, Qiu P. Transfer of neuron-derived α-synuclein to astrocytes induces neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier damage after methamphetamine exposure: Involving the regulation of nuclear receptor-associated protein 1. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;106:247-261. [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi S, Daiwile AP, Cadet JL. Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine: Main effects and mechanisms. Exp Neurol. 2021;344:113795. [CrossRef]

- Zareifopoulos N, Skaltsa M, Dimitriou A, Karveli M, Efthimiou P, Lagadinou M, Tsigkou A, Velissaris D. Converging dopaminergic neurotoxicity mechanisms of antipsychotics, methamphetamine and levodopa. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(13):4514-4519. [CrossRef]

- Thangam EB, Jemima EA, Singh H, Baig MS, Khan M, Mathias CB, Church MK, Saluja R. The Role of Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Mast Cell-Mediated Allergy and Inflammation: The Hunt for New Therapeutic Targets. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1873. [CrossRef]

- van der Vorst EP, Döring Y, Weber C. Chemokines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(11):e52-6. [CrossRef]

- Miller MC, Mayo KH. Chemokines from a Structural Perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(10):2088. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Jiang L, Bian C, Liang Y, Xing R, Yishakea M, Dong J. Role of CX3CL1 in Diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2016;64(5):371-83. [CrossRef]

- Vérité J, Janet T, Chassaing D, Fauconneau B, Rabeony H, Page G. Longitudinal chemokine profile expression in a blood-brain barrier model from Alzheimer transgenic versus wild-type mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):182. [CrossRef]

- Bachstetter AD, Morganti JM, Jernberg J, Schlunk A, Mitchell SH, Brewster KW, Hudson CE, Cole MJ, Harrison JK, Bickford PC, Gemma C. Fractalkine and CX 3 CR1 regulate hippocampal neurogenesis in adult and aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(11):2030-44. [CrossRef]

- Rogers JT, Morganti JM, Bachstetter AD, Hudson CE, Peters MM, Grimmig BA, Weeber EJ, Bickford PC, Gemma C. CX3CR1 deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2011;31(45):16241-50. [CrossRef]

- Williams JL, Holman DW, Klein RS. Chemokines in the balance: maintenance of homeostasis and protection at CNS barriers. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:154. [CrossRef]

- Legler DF, Thelen M. Chemokines: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biological Function. Chimia (Aarau). 2016;70(12):856-859. [CrossRef]

- Ancuta P, Moses A, Gabuzda D. Transendothelial migration of CD16+ monocytes in response to fractalkine under constitutive and inflammatory conditions. Immunobiology. 2004;209(1-2):11-20. [CrossRef]

- Bertin J, Jalaguier P, Barat C, Roy MA, Tremblay MJ. Exposure of human astrocytes to leukotriene C4 promotes a CX3CL1/fractalkine-mediated transmigration of HIV-1-infected CD4⁺ T cells across an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. Virology. 2014;454-455:128-38. [CrossRef]

- Curtaz CJ, Schmitt C, Herbert SL, Feldheim J, Schlegel N, Gosselet F, Hagemann C, Roewer N, Meybohm P, Wöckel A, Burek M. Serum-derived factors of breast cancer patients with brain metastases alter permeability of a human blood-brain barrier model. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2020;17(1): 31. [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos-Cabrera I, Valle-Dorado MG, Aldana BI, Orozco-Suárez SA, Rocha L. Role of histaminergic system in blood-brain barrier dysfunction associated with neurological disorders. Arch Med Res. 2014;45(8):677-86. [CrossRef]

- Alstadhaug KB. Histamine in migraine and brain. Headache. 2014;54(2):246-59. [CrossRef]

- Abbott NJ. Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20(2):131-47. [CrossRef]

- Sharma HS, Vannemreddy P, Patnaik R, Patnaik S, Mohanty S. Histamine receptors influence blood-spinal cord barrier permeability, edema formation, and spinal cord blood flow following trauma to the rat spinal cord. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006;96:316-21. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Cai XJ, Qin J, Xie FJ, Han N, Lu HY. The role of histamine in opening blood-tumor barrier. Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):31299-310. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Diehl SA, Noubade R, Ledoux J, Nelson MT, Spach K, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP, Teuscher C. Endothelial histamine H1 receptor signaling reduces blood-brain barrier permeability and susceptibility to autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(44):18967-72. [CrossRef]

- Scammell TE, Jackson AC, Franks NP, Wisden W, Dauvilliers Y. Histamine: neural circuits and new medications. Sleep. 2019;42(1):zsy183. [CrossRef]

- Brown RE, Stevens DR, Haas HL. The physiology of brain histamine. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63(6): 637-72. [CrossRef]

- Saxton RA, Glassman CR, Garcia KC. Emerging principles of cytokine pharmacology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(1):21-37. [CrossRef]

- Holder PG, Lim SA, Huang CS, Sharma P, Dagdas YS, Bulutoglu B, Sockolosky JT. Engineering interferons and interleukins for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;182:114112. [CrossRef]

- Pignataro G, Cataldi M, Taglialatela M. Neurological risks and benefits of cytokine-based treatments in coronavirus disease 2019: from preclinical to clinical evidence. Br J Pharmacol. 2022; 179(10):2149-2174. [CrossRef]

- Ge Y, Wu J, Zhang L, Huang N, Luo Y. A New Strategy for the Regulation of Neuroinflammation: Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2024;44(1):24. [CrossRef]

- Klein RS, Hunter CA. Protective and Pathological Immunity during Central Nervous System Infections. Immunity. 2017;46(6):891-909. [CrossRef]

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis - a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):27-40. [CrossRef]

- Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2021;397(10280):1214-1228. [CrossRef]

- Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1023-36. [CrossRef]

- Younger DS. The Blood-Brain Barrier: Implications for Vasculitis. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(2):235-248. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz GG, Pacheco-Moisés FP, Macías-Islas MÁ, Flores-Alvarado LJ, Mireles-Ramírez MA, González-Renovato ED, Hernández-Navarro VE, Sánchez-López AL, Alatorre-Jiménez MA. Role of the blood-brain barrier in multiple sclerosis. Arch Med Res. 2014;45(8):687-97. [CrossRef]

- Khan AW, Farooq M, Hwang MJ, Haseeb M, Choi S. Autoimmune Neuroinflammatory Diseases: Role of Interleukins. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):7960. [CrossRef]

- Takeshita Y, Fujikawa S, Serizawa K, Fujisawa M, Matsuo K, Nemoto J, Shimizu F, Sano Y, Tomizawa-Shinohara H, Miyake S, Ransohoff RM, Kanda T. New BBB Model Reveals That IL-6 Blockade Suppressed the BBB Disorder, Preventing Onset of NMOSD. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(6):e1076. [CrossRef]

- Corti A, Calimeri T, Curnis F, Ferreri AJM. Targeting the Blood-Brain Tumor Barrier with Tumor Necrosis Factor-α. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(7):1414. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Alvarado G, Becerril-Villanueva E, Contis-Montes de Oca A, Domínguez-Salazar E, Salinas-Jazmín N, Pérez-Tapia SM, Pavon L, Velázquez-Moctezuma J, Gómez-González B. The yin/yang of inflammatory status: Blood-brain barrier regulation during sleep. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;69: 154-166. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhou L, Bao L, Liu J, Zhu H, Lv Q, Liu R, Chen W, Tong W, Wei Q, Xu Y, Deng W, Gao H, Xue J, Song Z, Yu P, Han Y, Zhang Y, Sun X, Yu X, Qin C. SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier accompanied with basement membrane disruption without tight junctions alteration. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):337. [CrossRef]

- Montazersaheb S, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, Hejazi MS, Tarhriz V, Farjami A, Ghasemian Sorbeni F, Farahzadi R, Ghasemnejad T. COVID-19 infection: an overview on cytokine storm and related interventions. Virol J. 2022;19(1):92. [CrossRef]

- Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020; 39(7):2085-2094. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Parra H, Reyes-Hernández OD, Figueroa-González G, González-Del Carmen M, González-Torres M, Peña-Corona SI, Florán B, Cortés H, Leyva-Gómez G. Alteration of the blood-brain barrier by COVID-19 and its implication in the permeation of drugs into the brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1125109. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Tang X, Li J, Hu B, Yang W, Zhan M, Ma T, Xu S. IL-17 crosses the blood-brain barrier to trigger neuroinflammation: a novel mechanism in nitroglycerin-induced chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):1. [CrossRef]

| Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Impact on the structural elements of the BBB | References |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1 |

|

[92,93] [94] [95] [96] [93,97,98] |

| IL-1β |

|

[95,99] [95] [96,100] |

| IL-2 |

|

[101] [102] [103] [104] |

| IL-6 |

|

[105] [88] [106] [107,108] |

| IL-12 |

|

[109,110] [111] |

| IL-15 |

|

[112,113] [114] [115] |

| IL-17 |

|

[116] |

| IL-18 |

|

[117] |

| TNF-α |

|

[118] [119] [120] [121,122] |

| IFN-γ |

|

[123] [124] [125,126] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).