1. Introduction

Infertility is defined as the failure to achieve pregnancy after at least 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. It affects about 70 million people worldwide and female factors account for about 37% of cases [

1,

2]. Infertility is caused by identifiable abnormalities or underlying disease in 85% of infertile couples. The remaining 15% are reported as affected by “unexplained infertility” [

1]. Environmental chemicals may have a huge impact on human and animal fertility. According to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), some pollutants are classified as Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): ‘‘Exogenous agents that interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, metabolism, binding action, or elimination of natural blood-borne hormones that are present in the body and are responsible for homeostasis, reproduction and developmental processes’’ [

3]. EDC production has enormously increased during the last decades because they are widely used in society. Indeed, they become ubiquitous and are commonly found in natural settings as they are in a wide range of products, and many of them have a prominent role in food chain since they can easily contaminate fish, meat, dairy and poultry products [

4]. Humans and animals are exposed to a broad range of EDCs mainly through inhalation, dermal and dietary uptake. It is increasingly recognized that they may be harmful to human and animal health causing reproductive disorders [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] and other diseases [

10,

11,

12]. Phtalates, including Diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), and heavy metals such as Cadmium (Cd), are widely diffused EDCs reported as affecting female reproductive system.

DEHP is one of the most used industrial chemicals known as “plasticizer” to make the plastic material harder, flexible and durable. It is present in a wide range of products, such as packaging for food and beverages, pharmaceutical products for personal care, children's toys and medical equipment [

4]. After sunlight exposure or food package treatments, DEHP may leach out of the plastic material into food chain [

13,

14,

15] and it is able to enter the body by oral ingestion [

16], inhalation (house dust; [

17,

18,

19]) or dermal contact (through using personal care products or handling medical devices; [

20,

21]). DEHP has been detected in a wide variety of human specimens, such as serum [

22,

23], urine [

24,

25], semen [

24,

26] and breast milk [

27]. DEHP has been reported also in animal biological samples such as in bovine milk [

28], in ovine [

29] and in swine [

30] tissue. Recent studies have highlighted the presence of DEHP also in human follicular fluid and established a direct correlation between exposure to this compound and detrimental effects on ovaries [

19,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. These findings confirm previous studies performed in animal models providing evidence that exposure to DEHP can impair folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation and adversely affect embryo development [

8,

9,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

Additional dangerous pollutants include Cd, a toxic non-essential transition metal widely used in consumer products including cigarettes, batteries, jewels, and as colorant of plastics, ceramics, glassware goods and paints [

49]. So, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/cadmium/Who-Is-at-Risk.html) specific professional categories or smokers are particularly exposed to Cd. Moreover, exposure to Cd takes place mainly through oral ingestion of contaminated water and food such as rice, potatoes, wheat, leafy salad vegetables and other cereal crops, mollusks and crustaceans, oilseeds, offal [

50,

51]. In areas with contaminated soils, house dust is also a potential route for Cd exposure [

52,

53]. Cd is known to have a long half-life and once absorbed by the body, it is transported into the bloodstream via erythrocytes and albumin to be irreversibly accumulated in the liver, gut and kidneys [

54,

55]. Cd can also accumulate in the ovaries and in follicular fluid adversely influencing the likelihood of pregnancy and live birth [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Cadmium acts by perturbating the process of folliculogenesis, causing developmental disorders of primordial follicles and increasing the number of atretic follicles [

61]. Moreover, it impairs the oocyte quality and meiotic maturation rate leading to a decrease in female fertility as reported in in-vivo [

60,

62,

63] and in-vitro [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68] studies.

Given the occurrence of Cd and DEHP in food packaging materials, humans and animals have a high probability to be exposed to mixture of these chemicals rather than to a single contaminant. These two plastic additives are not covalently bound but simply mixed with plastic polymers, so that inappropriate plastic use, disposal and recycling may leach to their undesirable release from food packaging materials into food and feed [

69]. To date, to the best of our knowledge, the joint effects (i.e. additive, synergistic or attenuative) on oocyte maturation of Cd and DEHP have never been studied and most of currently performed toxicological research so far focused on evaluating the effects of individual compounds. However, in an innovative perspective, it is recognized the importance of moving from a research paradigm based on a single pollutant to assessing the potential risks of human and animal exposure to chemical mixtures defined by EFSA as “any combination of two or more chemicals that may contribute to effects on a receptor (human or environmental) regardless of source and spatial or temporal proximity” [

70]. Evaluating the effects of combined exposure to multiple chemicals on reproductive cells is still a challenge since few in vivo reproductive toxicity studies have investigated mixtures of chemicals [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

In this context, the aim of the present study was to evaluate, in the sheep model, the effects of in vitro exposure to a DEHP and Cd mixture on nuclear maturation and bioenergetic aspects of developmental potential of cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) in comparison with individual contaminants.

2. Results

In this study, the nuclear chromatin configuration at metaphase II with the first polar body extruded (MII+PB) was the endpoint aimed at evaluating the effects of contaminants on oocyte maturation whereas bioenergetic parameters of expanded CCs and matured (MII+PB) oocytes were the endpoints aimed at evaluating the effects of contaminants on oocyte developmental potential.

2.1. Results

Preliminarily, DEHP toxicity was tested at the concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5 µM. Control oocytes were cultured in IVM medium supplemented with/without DEHP vehicle. DEHP concentrations were selected based on previous studies carried out on horse oocytes [

38,

44]. In this experimental part, denuded oocytes were analyzed for nuclear chromatin. Since no effects on nuclear maturation were found, we wanted to analyze any cytoplasmic toxicity effects of DEPH. Therefore, mature oocytes were analyzed for cytoplasmic bioenergetic parameters.

2.1. DEHP Altered the Bioenergetic/Oxidative Status of Ovine Oocytes Matured In Vitro

Cumulus-oocyte complexes (n = 301 COCs in three independent replicates) were exposed to 0.1µM and 0.5µM DEHP during IVM. As shown in

Table 1, no difference was noted between the maturation rates of oocytes cultured in control conditions (CTRL) versus those cultured in vehicle, thus subsequent experiments were performed by using only vehicle as control. DEHP exposure during IVM did not alter the percentage of oocytes that reached the MII stage compared with control oocytes (

Table 1). Similarly, no statistically significant difference was observed between treated and control oocytes in the percentage of oocytes remaining at the stage of GV, MI or showing abnormal nuclear chromatin configurations (

Table 1).

In order to determine the effects of DEHP on oocyte bioenergetic/oxidative status, we used fluorescent labelling confocal microscopy in single matured ones obtained after IVM to analyze a set of energy/redox ooplasmic parameters, such as mitochondrial distribution pattern, mitochondrial membrane potential, intracellular ROS localization and levels. As shown in

Table 2, mitochondrial distribution pattern did not vary in Vehicle CTRL oocytes compared with CTRL. In the group of oocytes exposed to 0.5μM DEHP, the percentage of oocytes showing healthy heterogeneous perinuclear and subplasmalemmal mitochondrial distribution pattern was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) and a corresponding increase in the percentage of oocytes showing small aggregates mitochondrial pattern (P < 0.05) was observed compared to control conditions. The increased trend in unhealthy mitochondria distribution pattern was also observed at 0.1 µM DEHP, even if it was not statistically significant (P=0.0537).

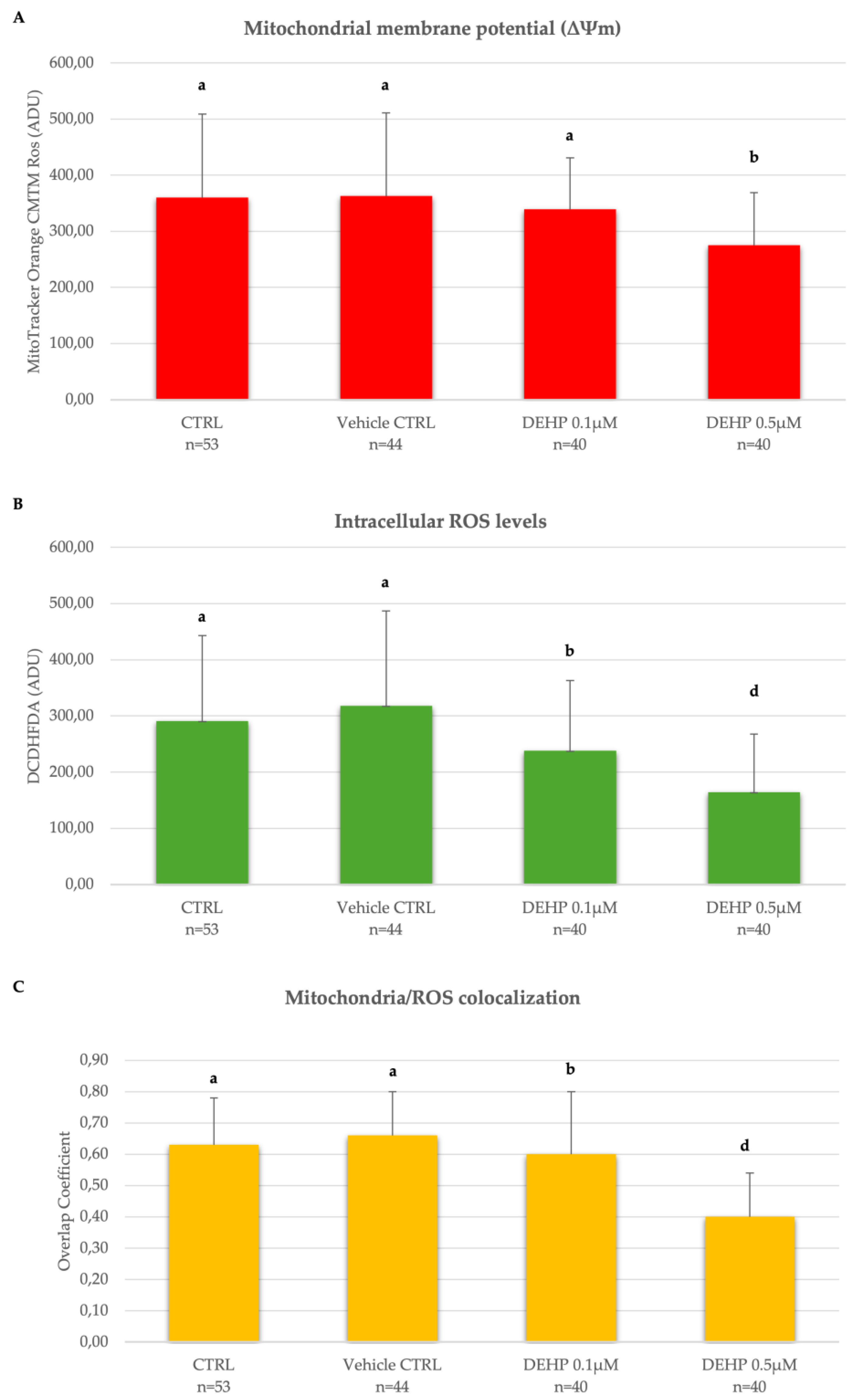

As shown in

Figure 1A-C, displaying Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros and DCF fluorescence intensity, and Overlap coefficient which indicate oocyte mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondria/ROS co-localization respectively, these parameters did not vary between CTRL and vehicle CTRL groups. However, ΔΨm was significantly reduced in the group of mature oocytes exposed to DEHP 0.5µM compared with oocytes cultured under control conditions (P<0.05,

Figure 1A). In addition, intracellular ROS levels and the degree of mitochondria/ROS co-localization were significantly reduced at both tested DEHP concentrations, as shown by the reduced levels of DCF intensity and coefficient of overlap in DEHP-exposed oocytes compared with oocytes cultured under CTRL conditions (

Figure 1B-C). Given the results obtained, the concentration of DEHP 0.5 µM was identified as the most toxic to ovine oocytes and selected for experiments 2.

2.2. Results

Based on the observation of the DEHP dose-dependence curve, the concentration of 0.5µM DEHP was selected for the mixture. Cadmium chloride (CdCl

2) concentration at 0.1µM was identified based on previous studies [

64,

80]. The effects of DEHP/Cd mixture were tested and compared with those of 0.5µM DEHP and 0.1µM CdCl

2 individually. In this experimental part, cells from healthy, expanded cumulus oophores, presumably derived from COCs containing mature oocytes, were collected and analyzed. Subsequently, the denuded oocytes were analyzed for nuclear chromatin and only the mature ones were analyzed for cytoplasmic bioenergetic parameters.

2.2.1. The DEHP/Cd Mixture and Individual Compounds Similarly Affected Oocyte Bioenergetic/Oxidative Status

A total of 484 oocytes were analyzed in 5 replicates for nuclear maturation and bioenergetic/oxidative status. As shown in

Table 3, any treatment (DEHP/Cd mixture, DEHP and Cd) had no significant effect on the percentages of oocytes that were able to reach the MII+PB stage.

Mature (MII) oocytes from 4 out of 5 replicates were also assessed for their bioenergetic/oxidative status. Both the DEHP/Cd mixture and Cd and DEHP in single altered the bioenergetic/oxidative status of mature oocytes compared to controls.

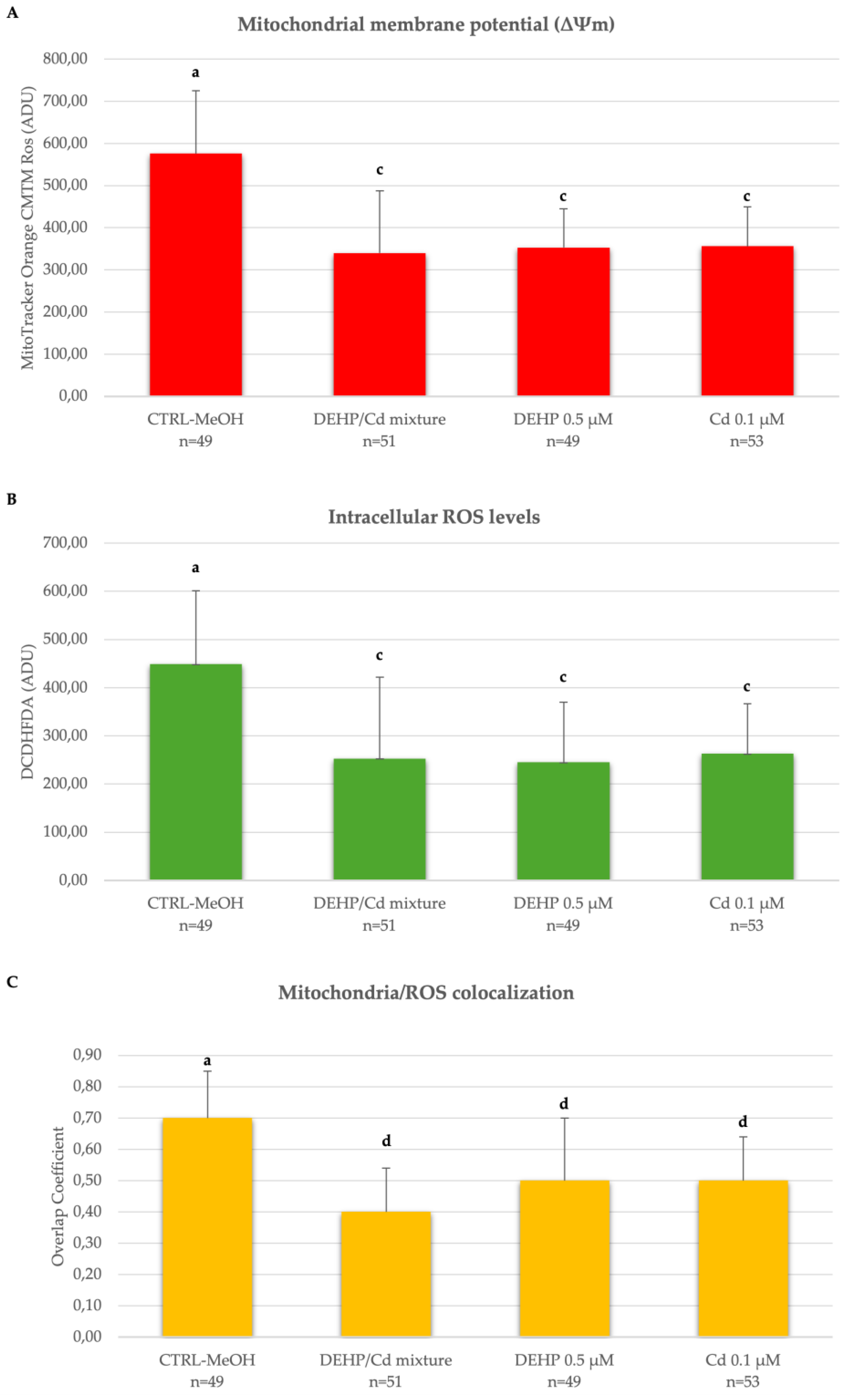

In detail (

Table 4), DEHP/Cd mixture as well as both single compounds significantly reduced the percentage of matured oocytes with healthy mitochondrial P/S distribution pattern. In the presence of the DEHP/Cd mixture the damage was more pronounced as can be seen from the very low percentage of mature oocytes with a healthy mitochondrial distribution pattern (P<0.001;

Table 4).

In addition, oocytes matured in the presence of DEHP/Cd mixture, DEHP or Cd showed significantly lower ΔΨm, intracellular ROS levels and degree of co-localization mitochondria/ROS compared to CTRL (

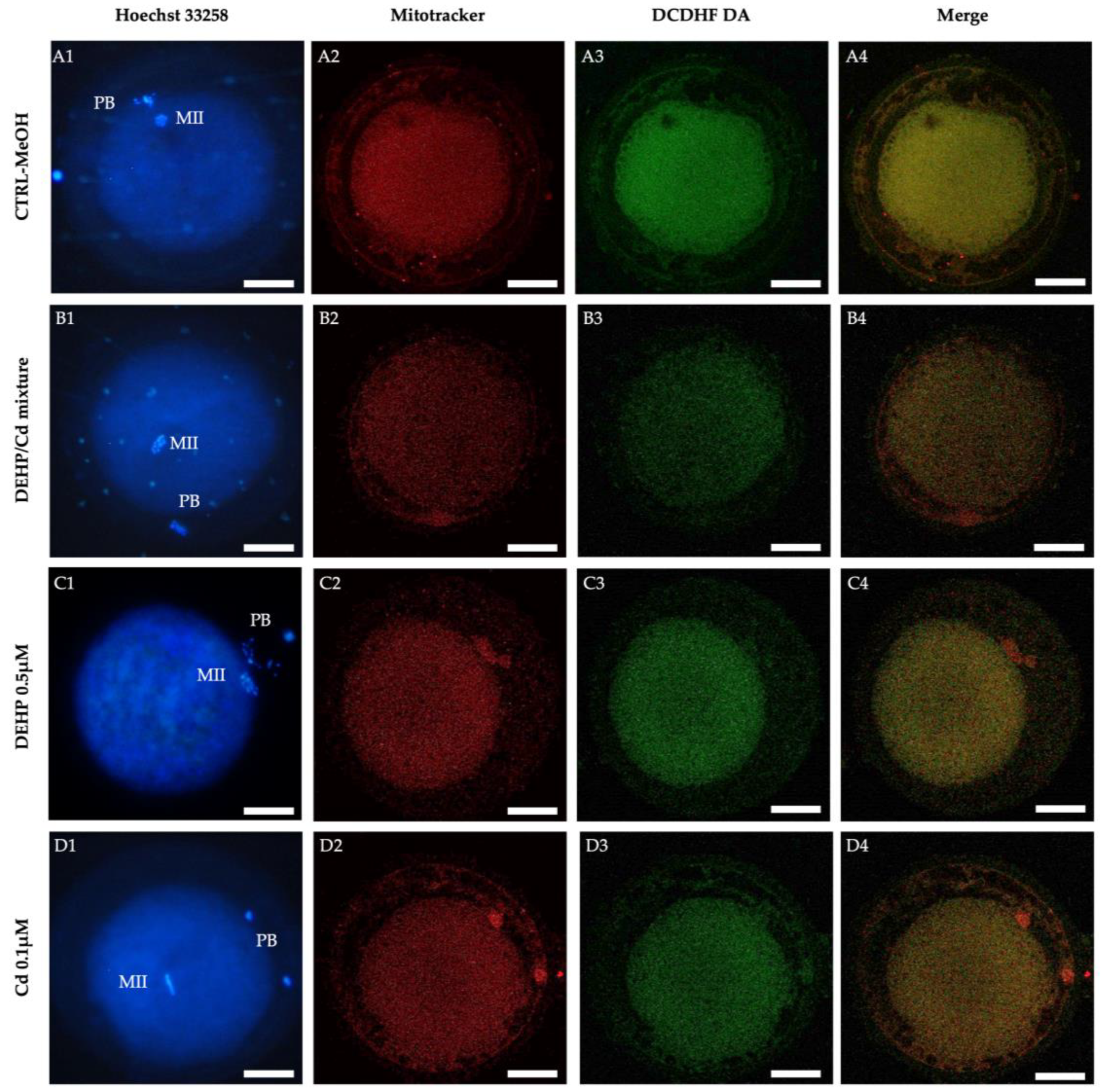

Figure 2). The bioenergetic damage induced in oocytes by DEHP/Cd mixture, DEHP or Cd is also evident looking at confocal microscopy images shown in

Figure 3. Whereas CTRL oocytes display a healthy P/S mitochondrial distribution pattern (

Figure 3, A2), oocytes exposed to the contaminants show a homogeneous mitochondrial distribution pattern typical of cytoplasmic immature oocytes (

Figure 3, B2, C2 and D2). In addition, the marked decrease of the fluorescence signal in the oocytes exposed to the contaminants (

Figure 3, B, C, D) indicates the reduction of the bioenergetic/oxidative parameters compared to CTRL (

Figure 3, A).

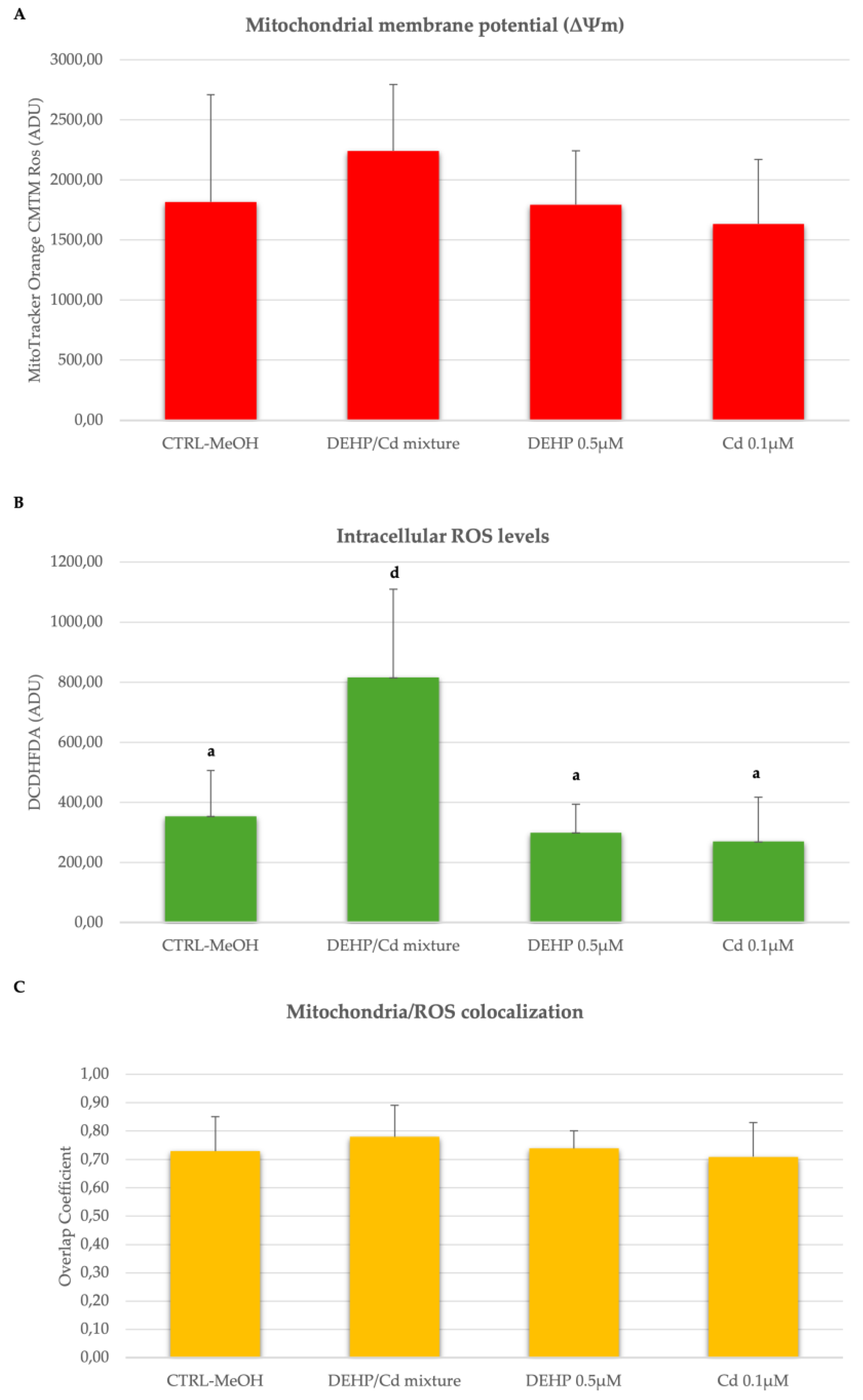

2.2.2. DEHP/Cd Mixture Altered the Bioenergetic/Oxidative Status of Cumulus Cells

In three out of the described 5 replicated, we isolated and analyzed CCs from in vitro cultured COCs. Cumulus cells from 68, 64, 74 and 57 COCs cultured under CTRL, DEHP/Cd mixture, 0.5µM DEHP and 0.1µM Cd, respectively, were assessed for bioenergetic parameters. Per each condition, 10 fields of about 20 cells were observed for a total of approximately 200 CCs per condition. The diagrams of the analyzed parameters are shown in

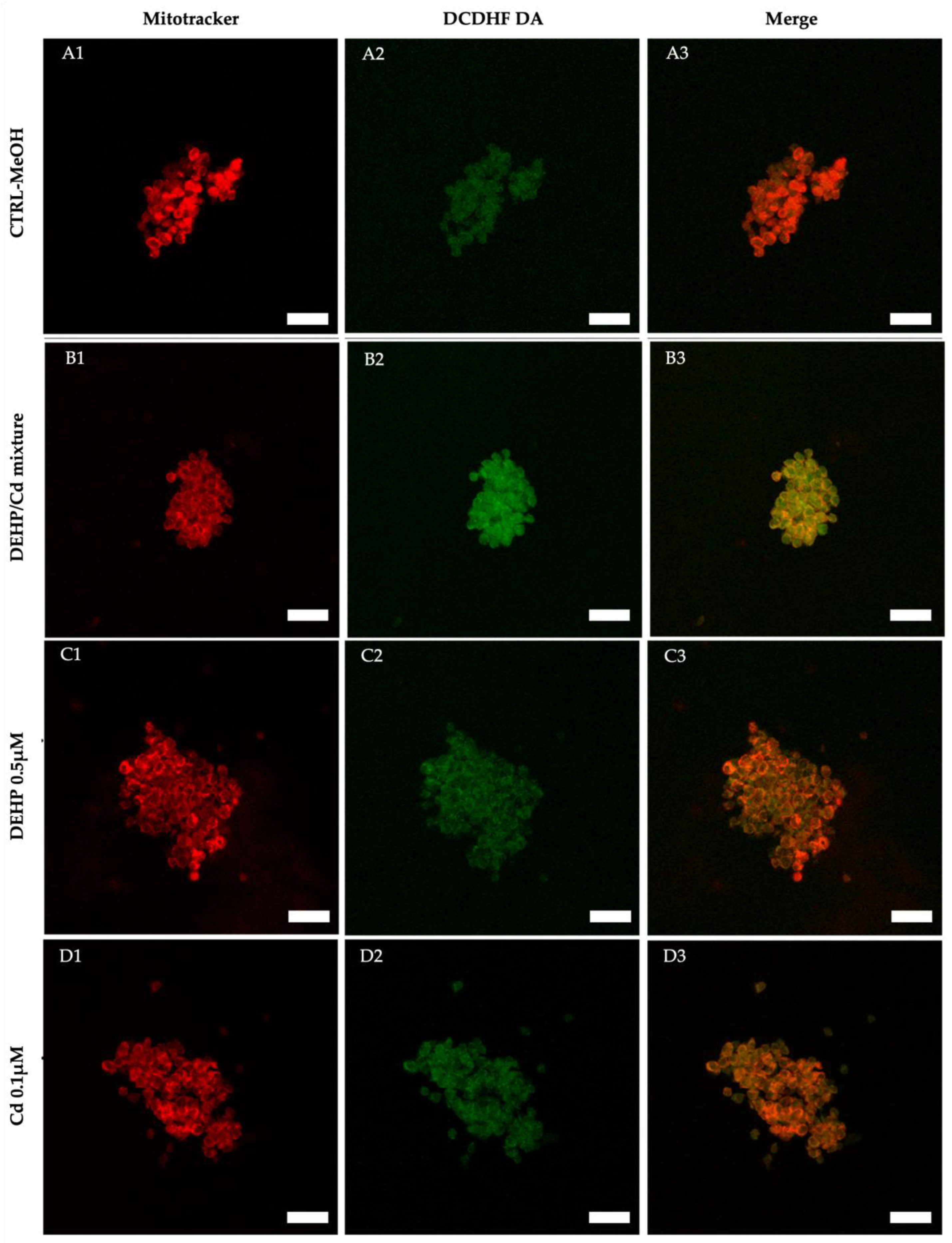

Figure 4. The experimental data shows that intracellular ROS levels stained with DCDHFDA were significantly increased in the CCs of ovine oocytes in vitro matured in the presence of DEHP/Cd mixture compared to those matured under the other conditions (

Figure 4B; p<0.001).

Figure 5 shows representative photomicrographs of a control CCs (A) and CCs exposed to DEHP/Cd mixture (B), DEHP (C) and Cd (D). Increased intracellular ROS levels in CCs exposed to the mixture (B2) can be observed.

3. Discussion

The novelty of this study is to analyze the effects of exposing COCs to a DEHP/Cd mixture during IVM on both COC somatic and germinal compartments (cumulus cells and the oocyte respectively) and to compare them with those of each individual compound. It is well known that DEHP and Cd are included in the list of EDCs, exogenous compound that may interfere with hormonal signals influencing reproductive functions [

7]. DEHP and Cd have similar sources and exposure routes for both humans and animals that can be often exposed to their mixtures. Extensive research has revealed the effects of individual pollutants while a significant gap persists in understanding combined effects of their mixtures.

In this study, the prepubertal sheep model has been used which, besides being economically important worldwide for animal productions, is also useful for studying potential effects of chemicals on oocyte maturation [

81,

82] and is a relevant translational animal model for human reproductive medicine [

81,

82,

83].

We preliminarily analyzed the effects of two DEHP concentrations to identify an effective concentration on COCs of the animal model species used in this study. We found that 0.1 and 0.5 µM DEHP did not compromise oocyte nuclear maturation rates. This result is in line with data of studies performed in pig [

84] and equine oocytes exposed to DEHP [

44]. Despite a lack of effect on oocyte nuclear maturation, our findings indicated that DEHP exposure, at the highest tested concentration (0.5µM), was associated with oocyte mitochondrial dysfunction, as demonstrated by a significant reduction of matured oocytes with healthy perinuclear/subplasmalemmal mitochondrial distribution pattern and decreased quantitative mitochondrial parameters. Similar results were previously reported in mice oocytes in which DEHP impaired mitochondrial function and membrane potential [

85].

After having selected 0.5µM as toxic concentration of DEHP, our aim was to test the effects of the DEHP/Cd mixture on sheep COCs compared with those of each individual compound. The Cd concentration was selected based on previous studies [

64,

80]. Our findings indicated that exposing COCs to the mixture versus each single contaminant did not alter in vitro oocyte nuclear maturation but significantly impaired their cytoplasmic maturation demonstrated by oocyte inability to properly direct mitochondria migration at perinuclear and subplasmalemmal cytoplasmic compartments and by mitochondrial dysfunctions, such as decreased membrane potential, ROS production and mitochondria/ROS co-localization. In oocytes, the DEHP/Cd mixture did not display significantly different effects compared to single contaminants. In a certain sense this result is not surprising as tt has been reported that combined effects are generally nonlinear when the chemical concentrations are low even if the modes of action of the chemicals are similar [

86]. It could therefore be hypothesized that the two contaminants, in single, have already determined maximum levels of toxicity in sheep oocytes, so that exposure to the mixture did not cause more pronounced damage.

However, interestingly, when the effect of the contaminants was tested on the CCs derived from COCs cultured in vitro, we found that the DEHP/Cd mixture, but not each single contaminant, significantly increased ROS levels. It is well known that in single DEHP [

87] and Cd [

88] positively correlated with the level of oxidative stress and increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes in granulosa cells. This damage was not associated with CC mitochondrial damage, supporting previous findings that CC activity plays a major role in protecting the oocyte against environmental contaminants [

89,

90,

91]. Therefore, it could be assumed that the effect of the mixture is blocked at CC level, not causing greater damage at oocyte level which therefore shows damage similar to that caused by the single contaminant.

To date, to the best of our knowledge, the availability of studies evaluating the impact of simultaneous exposure to DEHP and Cd mixture is limited. In previously published papers, some mostly the detrimental effects of co-exposure to contaminants belonging to the same class of contaminants on reproductive cell functions have been studied (heavy metals [

92,

93]; phthalate [

94,

95,

96]). Only one study [

63] focused on analyzing the effects of vivo exposure to Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP - the primary and the most toxic metabolite of DEHP) and Cd, individually and their binary mixture, on some target organs, such as liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys of mice. The results of this study are in line with our ones, as it demonstrated that the toxic effects of environmental contaminants, both in single and in mixture, resulted in the suppression of tissue cell proliferation, but mainly in the destruction of the structure, integrity permeability and fluidity of the cell membrane increasing the cell susceptibility to oxidative stress.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

All chemicals for in vitro cultures and analyses were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy) unless otherwise indicated. For in vitro culture, DEHP was diluted in methanol (MeOH) at the concentration of 12.8mM. The stock solution was stored at +4°C until the day of use. A 100mM stock solution of Cd chloride (CdCl2) was prepared by dissolving CdCl2 in distilled water. The stock solution was stored at room temperature until the day of use.

4.2. Collection of Ovaries

Ovaries were recovered at a local slaughterhouse (Siciliani s.r.l.; Palo del Colle, Bari) from juvenile ewes (less than 6 months of age) subjected to routine veterinary inspection in accordance with the specific health requirements stated. Ovaries were transported to the laboratory at room temperature within 4 hours from slaughter.

4.3. COC Retrieval and Selection

Ovaries were processed by the slicing procedure for immature COC retrieval [

64]. Follicular contents were released in sterile Petri dishes containing phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Only undamaged COCs displaying oocytes with homogeneous cytoplasm and surrounded by at least three intact cumulus cells (CCs) layers were selected for in vitro culture under a Nikon SMZ18 stereomicroscope equipped with a transparent heating stage set up at 37°C (Okolab S.r.l., Napoli, Italy) [

77].

4.4. In Vitro Maturation (IVM)

COCs were in vitro cultured as previously reported [

78]. Briefly, in vitro maturation (IVM) medium was prepared from TCM199 with Earle’s salts, buffered with 5.87mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 33.09mM sodium bicarbonate and supplemented with 200mM L-glutamine solution, 2.27mM sodium pyruvate, 2.92mM calcium- L-lactate pentahydrate (1.62mM Ca

2+, 3.9mM Lactate), 50μg/ml gentamicin, 20% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS), gonadotropins (10μg/mL of porcine follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone (FSH/LH; Pluset®, Calier, Barcelona, Spain) and 1μg/ml 17β estradiol. The medium was pre-equilibrated for 1hour under 5% CO

2 in air atmosphere at 38.5°C, then transferred (400µL/well) in a 4-well dish (Nunc Intermed, Roskilde, Denmark) and covered with pre-equilibrated lightweight paraffin oil. In each experiment, approximately 20–25 COCs per condition were placed in a well of the four-well dish. IVM culture was performed for 24 hours at 38.5°C under 5% CO2 in air. During culture, COCs were alternatively exposed to 0.1µM or 0.5µM DEHP or a mixture with 0.1µM CdCl

2 and 0.5µM DEHP/0.1µM in IVM medium. Medium with 0.0005% MeOH, as DEHP vehicle was used as control. The working solutions were prepared by diluting the respective stock solutions in IVM medium on the day of experiment [

38,

44,

64].

4.5. Cumulus Cell Isolation and Collection

After IVM culture, CCs were removed from COCs by denuding procedure. In detail, CCs were mechanically stripped from oocytes under stereomicroscopy using Gilson micropipettes. COCs were gently pipetted up and down in TCM199 with 20% FCS and 80IU hyaluronidase/mL. Denuded oocytes were collected and processed for further evaluations as described below. Isolated CCs were collected in 0.5mL RNAse-free tubes and washed 3 times in TCM199 with 20% FCS by centrifugation at 300 x g for 2 min.

4.6. Oocyte and CC Staining for Mitochondrial and Intracellular ROS

In order to localize ooplasmic mitochondria and reactive oxygen species (ROS), ovine oocytes and CCs underwent a staining procedure with MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and H

2DCF-DA as previously described [

78,

79]. Oocytes and CCs were washed three times in PBS with 3% BSA. CCs were centrifuged at 300 x g for 2 min each time. After washing, oocytes and CC pellet were incubated for 30 min in the same medium containing 280nM MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos at 38.5°C under 5% CO

2. The cells were gently shaken a few times during the incubation. Following incubation with MitoTracker, oocytes and CCs were washed thrice in PBS with 0.3% BSA and incubated for 15 min, at 38.5°C under 5% CO

2, in the same medium containing 10µM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H

2DCF-DA) to detect the dichlorofluorescein (DCF) and localize intracellular sources of ROS. Oocytes and CC pellet were then washed in PBS without BSA and fixed overnight at 4°C with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution in PBS [

38]. Particular attention was paid to avoid sample exposure to the light during staining and fixing procedures to reduce photobleaching. After fixation, CCs were centrifuged, and their pellet was resuspended in 7μL PFA solution and subsequently added to a glass slide and covered with a cover glass that was sealed with nail polish. Microscope slides were kept at 4°C in the dark until observation

4.7. Oocyte Nuclear Chromatin Evaluation

Oocyte nuclear chromatin configuration was evaluated after fixation by oocyte staining with 2.5μg/ml Hoechst 33258 in 3:1 (vol/vol) glycerol/PBS and mounting on microscope slides maintained at 4°C in the dark until observation. Slides were examined under an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse 600; ×400 magnification) equipped with a B-2A (346 nm excitation/ 460 nm emission) filter. Oocytes were evaluated in relation to their meiotic stage and classified as germinal vesicle (GV), metaphase to telophase I (MI to TI), MII with the 1

st polar body (PB) extruded, or as degenerated for either multipolar meiotic spindle, irregular chromatin clumps or absence of chromatin [

78].

4.8. Assessment of Oocyte Mitochondria Distribution Pattern and Intracellular ROS Localization

MII Oocytes were observed using a Nikon C1/TE2000-U laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, Firenze, Italy) at ×600 magnification in oil immersion. A 543nm helium/neon laser and G-2A filter (551nm excitation and 576nm emission) were used to point out the MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos. A 488nm argon ion laser and the B-2A filter (495nm excitation and 519nm emission) were used to detect the DCF. To perform a 3D mitochondrial and ROS distribution analysis, oocytes were observed in 25 optical sections from the top to the bottom with a step size of 0.45μm. The mitochondrial distribution pattern was evaluated based on previous reported criteria [

78]. Thus, (a) perinuclear and subplasmalemmal distribution (P/S; with mitochondria more concentrated in the oocyte hemisphere where the meiotic spindle is located and forming large granules in the cortical region) was considered as characteristic of healthy cytoplasmic condition; (b) homogeneous distribution (with small mitochondria aggregates throughout the cytoplasm) was considered as an indication of low energy cytoplasmic condition; (c) irregular distribution of mitochondria forming large mitochondrial clusters was considered as abnormal distribution. Concerning intracellular ROS localization, healthy oocytes were considered those with intracellular ROS distributed throughout the cytoplasm, together with areas/sites of mitochondria/ROS overlapping.

4.9. Quantification of Oocyte and CC Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (m), Intracellular ROS Levels, and Mitochondria-ROS co-Localization

In each individual MII oocyte and CCs, MitoTracker and DCF fluorescence intensities, and overlap coefficient, were measured using the EZ-C1 Gold Version 3.70 image analysis software platform for Nikon C1 confocal microscope. The quantification analysis of the oocyte was performed at its equatorial plane. For CCs analysis, ten fields of groups of cells per condition per trial were analyzed. The analysis was performed by drawing a circle area to select and analyze only oocyte and CC regions including cell cytoplasm. The fluorescence intensity encountered within the programmed scan area (512 x 512 pixels) was recorded and 16-bit images were obtained. Mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular ROS levels were recorded as the fluorescence intensity emitted by MitoTracker and DCF probe, respectively, and expressed in arbitrary densitometric units (ADUs). Variables related to fluorescence intensity, such as laser energy, signal detection (gain), and pinhole size values were held constant for all measurements. The degree of mitochondria/ROS colocalization was recorded as overlap coefficient, indicating the overlap degree between MitoTraker Orange CMTMRos and DCF fluorescence signals. For mitochondria-ROS co-localization analysis, threshold levels were kept constant at 10% of the maximum pixel intensity.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

The proportions of oocytes showing the different chromatin configurations and mitochondria distribution patterns were compared among groups by Chi-square Test without or with Yates’ correction for contingency tables with small cell counts. The fluorescence intensity data of the MitoTracker CMTM Ros and DCF for quantitative analysis of the activity mitochondrial and intracellular ROS levels, respectively and the co-localization mitochondria/ROS (overlap coefficient) data were compared between the treated groups and the controls by one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test (GraphPad software 5.03, San Diego, CA). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences with p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we evaluated the toxic effects of DEHP and Cd mixture on the two cell types of the female gamete. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the effects of the DEHP/Cd mixture on oocyte meiotic competence in vitro. The toxicity of the mixture was comparable to that found in the individual contaminants at oocyte level. Cumulus cells appear to be more sensitive to mixture-induced oxidative damage, suggesting their protective role towards the oocyte and their possible role as biomarkers of DEHP/Cd mixture-induced COC damage. Overall, these data suggest that these chemicals may interfere with ovarian function. Further studies are needed to identify possible protection mechanisms of the CCs from the action of these contaminants on the oocyte and to identify the possible activities of EDC mixtures and the resulting risks for reproductive health of humans and animals considering the substantial use of plastic products for wider applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., N.A.M. and M.E.D.A.; Methodology, A.M. and M.E.D.A. ; Validation, A.M.; Formal Analysis, A.M. L.T. and V.V.; Investigation, A.M. and V.V.; Resources, A.M., N.A.M. and M.E.D.A.; Data Curation, A.M., M.E.D.A. and V.V.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.M., N.A.M. L.T., S.C. and M.E.D.A.; Supervision, N.A.M. and M.E.D.A.; Project Administration, A.M., N.A.M. and M.E.D.A.; Funding Acquisition, A.M., N.A.M. and M.E.D.A.

Funding

This research was funded by European Union Next-Generation EU-Italian PRIN 2022 PNRR n. P2022PRFM7 "Bio3versity", Bando ERC Seeds Uniba cod prog 2023-UNBACLE-0243987 "New challenges on FEmale Reproductive Toxicity testing: 3D in vitro oocyte maturation systems for contaminant mixtures toxicity evaluation” and Italian Ministry for Education, University, and Research; Unione europea – FSE-REACT-EU, PON Ricerca e Innovazione 2014-2020 DM1062/2021. The funding body played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carson, S.A.; Kallen, A.N. Diagnosis and Management of Infertility. JAMA 2021, 326, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization WH Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021; 2023.

- Sayles, G.D. Environmental Engineering and Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals. In ASCE Journal of Environmental Engineering; Arnold, R.G., Ed.; ASCE: Reston, VA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Thacharodi, A.; Priya, A.; Meenatchi, R.; Hegde, T.A.; R, T.; Nguyen, H.; Pugazhendhi, A. Endocrine Disruptors: Unravelling the Link between Chemical Exposure and Women’s Reproductive Health. Environ Res 2024, 241, 117385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev 2015, 36, E1–E150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. JAMA Intern Med 2016, 176, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, L.G.; Philippat, C.; Nakayama, S.F.; Slama, R.; Trasande, L. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Implications for Human Health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020, 8, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, T.; Zhou, L.; He, J.; Ye, L. Di-(2-Ethylhcxyl) Phthalate Reduces Progesterone Levels and Induces Apoptosis of Ovarian Granulosa Cell in Adult Female ICR Mice. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2012, 34, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, N.; Zhu, J.; Yu, G.; Guo, K.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, D.; Qu, X.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Effects of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis in Adult Female Rats. Reproductive Toxicology 2014, 46, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, R.; Benevento, E.; Colao, A. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) and Cancer: New Perspectives on an Old Relationship. J Endocrinol Invest 2022, 46, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, A.A.; Wheeler, H.B.; Blumberg, B. Obesity and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Connect 2021, 10, R87–R105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinault, C.; Caroli-Bosc, P.; Bost, F.; Chevalier, N. Critical Overview on Endocrine Disruptors in Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Bošnir; D. Puntarić; A. Galić; I. Škes; T. Dijanić; M. Klarić; M. Grgić; M.Čurković; Z. Šmit Migration of Phthalates from Plastic Containers into Soft Drinks and Mineral Water. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2007, 45, 91–95.

- Keresztes, S.; Tatár, E.; Czégény, Z.; Záray, G.; Mihucz, V.G. Study on the Leaching of Phthalates from Polyethylene Terephthalate Bottles into Mineral Water. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 458–460, 451–458. [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.-Y.; Lin, S.; Que, D.E.; Tayo, L.L.; Lin, D.-Y.; Chen, K.-C.; Chen, F.-A.; Chiang, P.-C.; Wang, G.-S.; Hsu, Y.-C.; et al. Estrogenic Effects in the Influents and Effluents of the Drinking Water Treatment Plants. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 8518–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, S.E.; Braun, J.; Trasande, L.; Dills, R.; Sathyanarayana, S. Phthalates and Diet: A Review of the Food Monitoring and Epidemiology Data. Environmental Health 2014, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promtes, K.; Kaewboonchoo, O.; Kawai, T.; Miyashita, K.; Panyapinyopol, B.; Kwonpongsagoon, S.; Takemura, S. Human Exposure to Phthalates from House Dust in Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 2019, 54, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H.; Xiao, H. Pollution Characteristics, Sources, and Health Risks of Phthalate Esters in Ambient Air: A Daily Continuous Monitoring Study in the Central Chinese City of Nanchang. Chemosphere 2024, 353, 141564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, B.; Yu, Y.; Dong, W. A Systematic Review of Global Distribution, Sources and Exposure Risk of Phthalate Esters (PAEs) in Indoor Dust. J Hazard Mater 2024, 471, 134423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, N.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, S.; Song, X. Exposure of Childbearing-Aged Female to Phthalates through the Use of Personal Care Products in China: An Assessment of Absorption via Dermal and Its Risk Characterization. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 807, 150980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, E.; Kuhlmann, L.; Göen, T.; Münch, F. Assessment of the Plasticizer Exposure of Hospital Workers Regularly Handling Medical Devices: A Pilot Study. Environ Res 2023, 237, 117028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, G.; De Felice, C.; Presta, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; Paris, I.; Ruggieri, F.; Mazzeo, P. In Utero Exposure to Di-(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate and Duration of Human Pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 2003, 111, 1783–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Qin, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, L. Distribution of Phthalate Metabolites between Paired Maternal–Fetal Samples. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 6626–6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, H.; Jorgensen, N.; Andersson, A.-M. Correlations Between Phthalate Metabolites in Urine, Serum, and Seminal Plasma from Young Danish Men Determined by Isotope Dilution Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol 2010, 34, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Zou, Z.; Lu, R.; Sun, C.; Wang, H.; et al. Associations of Urinary Phthalate Metabolites with Residential Characteristics, Lifestyles, and Dietary Habits among Young Children in Shanghai, China. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 616–617, 1288–1297. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-X.; Zeng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.; You, L.; Huang, Y.-H.; Wang, C.; et al. Semen Phthalate Metabolites, Semen Quality Parameters and Serum Reproductive Hormones: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Environmental Pollution 2016, 211, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.; Moon, S.-M.; Yang, E.J. Associations of Lifestyle Factors with Phthalate Metabolites, Bisphenol A, Parabens, and Triclosan Concentrations in Breast Milk of Korean Mothers. Chemosphere 2020, 249, 126149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krejčíková, M.; Jarošová, A. Phthalate in Cow Milk Depending on the Method of Milking.

- Rhind, S.M.; Kyle, C.E.; Telfer, G.; Duff, E.I.; Smith, A. Alkyl Phenols and Diethylhexyl Phthalate in Tissues of Sheep Grazing Pastures Fertilized with Sewage Sludge or Inorganic Fertilizer. Environ Health Perspect 2005, 113, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljungvall, K.; Tienpont, B.; David, F.; Magnusson, U.; Trneke, K. Kinetics of Orally Administered Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate and Its Metabolite, Mono(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate, in Male Pigs. Arch Toxicol 2004, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Guo, N.; Wang, Y.; Teng, X.; Hua, X.; Deng, T.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Li, Y. Follicular Fluid Concentrations of Phthalate Metabolites Are Associated with Altered Intrafollicular Reproductive Hormones in Women Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization. Fertil Steril 2019, 111, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Knapp, S.; Avraham, C.; Racowsky, C.; Hauser, R.; Bollati, V.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Machtinger, R. Association between Follicular Fluid Phthalate Concentrations and Extracellular Vesicle MicroRNAs Expression. Human Reproduction 2021, 36, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Jeon, J.H.; Jeong, K.; Chung, H.W.; Lee, H.; Sung, Y.-A.; Ye, S.; Ha, E.-H. The Association of Ovarian Reserve with Exposure to Bisphenol A and Phthalate in Reproductive-Aged Women. J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, I.; Björvang, R.D.; Hadziosmanovic, N.; Koekkoekk, J.; Pikki, A.; van Duursen, M.; Lenters, V.; Sjunnesson, Y.; Holte, J.; Berglund, L.; et al. Associations between Lifestyle Factors and Levels of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs), Phthalates and Parabens in Follicular Fluid in Women Undergoing Fertility Treatment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2023, 33, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.L.; Rehfeld, A.; Mortensen, L.J.; Lorenzen, M.; Andersson, A.-M.; Juul, A.; Bentin-Ley, U.; Krog, H.; Frederiksen, H.; Petersen, J.H.; et al. Ovarian Follicular Fluid Levels of Phthalates and Benzophenones in Relation to Fertility Outcomes. Environ Int 2024, 183, 108383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokyer, D.; Laws, M.J.; Kleinhans, A.; Riley, J.K.; Flaws, J.A.; Babayev, E. Phthalates Are Detected in the Follicular Fluid of Adolescents and Oocyte Donors with Associated Changes in the Cumulus Cell Transcriptome. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Svechnikova, I.; Svechnikov, K.; Söder, O. The Influence of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on Steroidogenesis by the Ovarian Granulosa Cells of Immature Female Rats. Journal of Endocrinology 2007, 194, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambruosi, B.; Filioli Uranio, M.; Sardanelli, A.M.; Pocar, P.; Martino, N.A.; Paternoster, M.S.; Amati, F.; Dell’Aquila, M.E. In Vitro Acute Exposure to DEHP Affects Oocyte Meiotic Maturation, Energy and Oxidative Stress Parameters in a Large Animal Model. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.; Kalo, D.; Gendelman, M.; Roth, Z. Effect of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate and Mono-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on in Vitro Developmental Competence of Bovine Oocytes. Cell Biol Toxicol 2012, 28, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, P.R.; Brannick, K.E.; Wang, W.; Gupta, R.K.; Flaws, J.A. Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Inhibits Antral Follicle Growth, Induces Atresia, and Inhibits Steroid Hormone Production in Cultured Mouse Antral Follicles. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2015, 284, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalo, D.; Hadas, R.; Furman, O.; Ben-Ari, J.; Maor, Y.; Patterson, D.G.; Tomey, C.; Roth, Z. Carryover Effects of Acute DEHP Exposure on Ovarian Function and Oocyte Developmental Competence in Lactating Cows. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0130896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.; Martinez–Arguelles, D.B.; Campioli, E.; Lee, S.; Papadopoulos, V. In Utero Exposure to the Endocrine Disruptor Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Targets Ovarian Theca Cells and Steroidogenesis in the Adult Female Rat. Reproductive Toxicology 2015, 51, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shen, W.; De Felici, M.; Zhang, X. Di(2-ethylhexyl)Phthalate: Adverse Effects on Folliculogenesis That Cannot Be Neglected. Environ Mol Mutagen 2016, 57, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, G.; Mastrorocco, A.; Zianni, R.; Mangiacotti, M.; Chiaravalle, A.E.; Lacalandra, G.M.; Minervini, F.; Cardinali, A.; Macciocca, M.; Vicenti, R.; et al. Altered Morphokinetics in Equine Embryos from Oocytes Exposed to DEHP during IVM. Mol Reprod Dev 2019, 86, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, S.; Beers, H.K.; Kannan, A.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Brehm, E.; Bagchi, I.; Irudayaraj, J.M.K.; Flaws, J.A. Prenatal and Ancestral Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Gene Expression and DNA Methylation in Mouse Ovaries. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2019, 379, 114629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-C.; Yan, Z.-H.; Li, B.; Yan, H.-C.; De Felici, M.; Shen, W. Di (2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Impairs Primordial Follicle Assembly by Increasing PDE3A Expression in Oocytes. Environmental Pollution 2021, 270, 116088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-J.; Tian, Y.; Li, M.-H.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Kong, L.; Zhang, F.-L.; Shen, W. Single-Cell Transcriptome Dissection of the Toxic Impact of Di (2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on Primordial Follicle Assembly. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4992–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laws, M.J.; Meling, D.D.; Deviney, A.R.K.; Santacruz-Márquez, R.; Flaws, J.A. Long-Term Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate, Diisononyl Phthalate, and a Mixture of Phthalates Alters Estrous Cyclicity and/or Impairs Gestational Index and Birth Rate in Mice. Toxicological Sciences 2023, 193, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A. Cadmium Pigments in Consumer Products and Their Health Risks. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 657, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S. Dietary Cadmium Intake and Its Effects on Kidneys. Toxics 2018, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, M.A.; Sens, D.A. Cadmium, Environmental Exposure, and Health Outcomes. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogervorst, J.; Plusquin, M.; Vangronsveld, J.; Nawrot, T.; Cuypers, A.; Van Hecke, E.; Roels, H.A.; Carleer, R.; Staessen, J.A. House Dust as Possible Route of Environmental Exposure to Cadmium and Lead in the Adult General Population. Environ Res 2007, 103, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chen, L.-J.; Li, H.-H.; Lin, J.-Q.; Yang, Z.-B.; Yang, Y.-X.; Xu, X.-X.; Xian, J.-R.; Shao, J.-R.; Zhu, X.-M. Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals Exposure via Household Dust from Urban Area in Chengdu, China. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 619–620, 621–629. [CrossRef]

- Tinkov, A.A.; Gritsenko, V.A.; Skalnaya, M.G.; Cherkasov, S. V.; Aaseth, J.; Skalny, A. V. Gut as a Target for Cadmium Toxicity. Environmental Pollution 2018, 235, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, W.; Hong, D.; Huang, L.; Li, Y. A Review on Cadmium Exposure in the Population and Intervention Strategies Against Cadmium Toxicity. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2021, 106, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, C.D.; Bloom, M.S.; McGough, A.; Lenhart, N.; Wong, R.; Mok-Lin, E.; Parsons, P.J.; Galusha, A.L.; Browne, R.W.; Yucel, R.M.; et al. Toxic Elements in Follicular Fluid Adversely Influence the Likelihood of Pregnancy and Live Birth in Women Undergoing IVF. Hum Reprod Open 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, S.J.S.; Agrawal, S. Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead. In Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 537–566.

- THOMPSON, J.; BANNIGAN, J. Cadmium: Toxic Effects on the Reproductive System and the Embryo. Reproductive Toxicology 2008, 25, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taupeau, C.; Poupon, J.; Nomé, F.; Lefèvre, B. Lead Accumulation in the Mouse Ovary after Treatment-Induced Follicular Atresia. Reproductive Toxicology 2001, 15, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglietta, S.; Cristiano, L.; Battaglione, E.; Macchiarelli, G.; Nottola, S.A.; De Marco, M.P.; Costanzi, F.; Schimberni, M.; Colacurci, N.; Caserta, D.; et al. Heavy Metals in Follicular Fluid Affect the Ultrastructure of the Human Mature Cumulus-Oocyte Complex. Cells 2023, 12, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Ru, Y.; Liu, M.; Tang, J.; Zheng, J.; Wu, B.; Gu, Y.; Shi, H. Reproductive Effects of Cadmium on Sperm Function and Early Embryonic Development in Vitro. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0186727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Liang, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, T.; Su, X.; Yin, T.; Zou, W.; Wang, X.; et al. The Association between Exposure to Multiple Toxic Metals and the Risk of Endometriosis: Evidence from the Results of Blood and Follicular Fluid. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 855, 158882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Duan, P.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wan, J.; Dai, M.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Tan, Y. Exposure to Cadmium and Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Induce Biochemical Changes in Rat Liver, Spleen, Lung and Kidney as Determined by Attenuated Total Reflection-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2019, 39, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, N.A.; Marzano, G.; Mangiacotti, M.; Miedico, O.; Sardanelli, A.M.; Gnoni, A.; Lacalandra, G.M.; Chiaravalle, A.E.; Ciani, E.; Bogliolo, L.; et al. Exposure to Cadmium during in Vitro Maturation at Environmental Nanomolar Levels Impairs Oocyte Fertilization through Oxidative Damage: A Large Animal Model Study. Reproductive Toxicology 2017, 69, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Khalıd, M. The Effect of Cadmium on the Bovine in Vitro Oocyte Maturation and Early Embryo Development. Int J Vet Sci Med 2018, 6, S73–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, B. Glutathione Alleviates the Cadmium Exposure-Caused Porcine Oocyte Meiotic Defects via Eliminating the Excessive ROS. Environmental Pollution 2019, 255, 113194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Xin, X.; Chang, H.-M.; Leung, P.C.K.; Yu, C.; Lian, F.; Wu, H. Expression of Long Noncoding RNAs in the Ovarian Granulosa Cells of Women with Diminished Ovarian Reserve Using High-Throughput Sequencing. J Ovarian Res 2022, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Li, J.; Lei, W.-L.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, Y.-C.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Z.-B.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.-Y. Chronic Cadmium Exposure Causes Oocyte Meiotic Arrest by Disrupting Spindle Assembly Checkpoint and Maturation Promoting Factor. Reproductive Toxicology 2020, 96, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An Overview of Chemical Additives Present in Plastics: Migration, Release, Fate and Environmental Impact during Their Use, Disposal and Recycling. J Hazard Mater 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, S.J.; Bampidis, V.; Benford, D.; Bennekou, S.H.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Hernández-Jerez, A.F.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Naegeli, H.; Schlatter, J.R.; et al. Guidance on Harmonised Methodologies for Human Health, Animal Health and Ecological Risk Assessment of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals. EFSA Journal 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fouikar, S.; Van Acker, N.; Héliès, V.; Frenois, F.-X.; Giton, F.; Gayrard, V.; Dauwe, Y.; Mselli-Lakhal, L.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D.; Fournier, N.; et al. Folliculogenesis and Steroidogenesis Alterations after Chronic Exposure to a Human-Relevant Mixture of Environmental Toxicants Spare the Ovarian Reserve in the Rabbit Model. J Ovarian Res 2024, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsioroski, A. V; Aquino, A.M.; Alonso-Costa, L.G.; Barbisan, L.F.; Scarano, W.R.; Flaws, J.A. Multigenerational Effects of an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture on Reproductive Parameters and Ovarian MiRNA Expression in Female Rats. Toxicological Sciences 2022, 189, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Brehm, E.; Leon, K.; Chiu, J.; Meling, D.D.; Flaws, J.A. Prenatal Exposure to an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture Alters Ovarian Steroidogenesis and Folliculogenesis in the F1 Generation of Adult Female Mice. Reproductive Toxicology 2021, 106, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, E.; Zhou, C.; Gao, L.; Flaws, J.A. Prenatal Exposure to an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture Accelerates Biomarkers of Reproductive Aging in a Multiple and Transgenerational Manner in Female Mice. Reproductive Toxicology 2020, 98, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, R.G.; Amezaga, M.R.; Loup, B.; Mandon-Pépin, B.; Stefansdottir, A.; Filis, P.; Kyle, C.; Zhang, Z.; Allen, C.; Purdie, L.; et al. The Fetal Ovary Exhibits Temporal Sensitivity to a ‘Real-Life’ Mixture of Environmental Chemicals. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.A.; Dora, N.J.; McFerran, H.; Amezaga, M.R.; Miller, D.W.; Lea, R.G.; Cash, P.; McNeilly, A.S.; Evans, N.P.; Cotinot, C.; et al. In Utero Exposure to Low Doses of Environmental Pollutants Disrupts Fetal Ovarian Development in Sheep. Mol Hum Reprod 2008, 14, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrorocco, A.; Cacopardo, L.; Lamanna, D.; Temerario, L.; Brunetti, G.; Carluccio, A.; Robbe, D.; Dell’Aquila, M.E. Bioengineering Approaches to Improve In Vitro Performance of Prepubertal Lamb Oocytes. Cells 2021, 10, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrorocco, A.; Martino, N.A.; Marzano, G.; Lacalandra, G.M.; Ciani, E.; Roelen, B.A.J.; Dell’Aquila, M.E.; Minervini, F. The Mycotoxin Beauvericin Induces Oocyte Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Affects Embryo Development in the Juvenile Sheep. Mol Reprod Dev 2019, 86, 1430–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, D.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Dong, X.; Shi, H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cumulus Cells Is Related to Decreased Reproductive Capacity in Advanced-Age Women. Fertil Steril 2022, 118, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, N.A.; Picardi, E.; Ciani, E.; D’Erchia, A.M.; Bogliolo, L.; Ariu, F.; Mastrorocco, A.; Temerario, L.; Mansi, L.; Palumbo, V.; et al. Cumulus Cell Transcriptome after Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Exposure to Nanomolar Cadmium in an In Vitro Animal Model of Prepubertal and Adult Age. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, M.; Harris, S.E.; Collado Fernandez, E.; Lu, J.; Huntriss, J.D.; Campbell, B.K.; Picton, H.M. The Activity and Copy Number of Mitochondrial DNA in Ovine Oocytes throughout Oogenesis in Vivo and during Oocyte Maturation in Vitro. MHR: Basic science of reproductive medicine 2013, 19, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leoni, G.G.; Palmerini, M.G.; Satta, V.; Succu, S.; Pasciu, V.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Macchiarelli, G.; Nottola, S.A.; Naitana, S.; et al. Differences in the Kinetic of the First Meiotic Division and in Active Mitochondrial Distribution between Prepubertal and Adult Oocytes Mirror Differences in Their Developmental Competence in a Sheep Model. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.K.; Souza, C.; Gong, J.; Webb, R.; Kendall, N.; Marsters, P.; Robinson, G.; Mitchell, A.; Telfer, E.E.; Baird, D.T. Domestic Ruminants as Models for the Elucidation of the Mechanisms Controlling Ovarian Follicle Development in Humans. Reprod Suppl 2003, 61, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarčíková, A.; Nagyová, E.; Ficková, M.; Scsuková, S. Effects of Selected Endocrine Disruptors on Meiotic Maturation, Cumulus Expansion, Synthesis of Hyaluronan and Progesterone by Porcine Oocyte–Cumulus Complexes. Toxicology in Vitro 2009, 23, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Deng, T.; Du, Y.; Yao, W.; Tian, W.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, W.; Li, Y. Impact of DEHP on Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes and Reproductive Toxicity in Ovary. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2024, 282, 116679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamo, M.; Yokomizo, H. Explanation of Non-Additive Effects in Mixtures of Similar Mode of Action Chemicals. Toxicology 2015, 335, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, V.; Sahu, A.N.; Singh, A.; Dubey, P.K. Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) Inhibits Steroidogenesis and Induces Mitochondria-ROS Mediated Apoptosis in Rat Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2019, 8, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, S.; Huang, M.; Jiang, X.; Yang, M. Cadmium Induces Apoptosis of Human Granulosa Cell Line KGN via Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Mediated Pathways. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 220, 112341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campen, K.A.; McNatty, K.P.; Pitman, J.L. A Protective Role of Cumulus Cells after Short-Term Exposure of Rat Cumulus Cell-Oocyte Complexes to Lifestyle or Environmental Contaminants. Reproductive Toxicology 2017, 69, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaeib, F.; Khan, S.N.; Ali, I.; Thakur, M.; Saed, G.; Dai, J.; Awonuga, A.O.; Banerjee, J.; Abu-Soud, H.M. The Defensive Role of Cumulus Cells Against Reactive Oxygen Species Insult in Metaphase II Mouse Oocytes. Reproductive Sciences 2016, 23, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Takeo, S.; Monji, Y.; Kuwayama, T.; Iwata, H. Maternal Liver Damage Delays Meiotic Resumption in Bovine Oocytes through Impairment of Signalling Cascades Originated from Low P38MAPK Activity in Cumulus Cells. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2014, 49, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.N.; Patel, U.D.; Khadayata, A. V.; Vaja, R.K.; Modi, C.M.; Patel, H.B. Long-Term Exposure of the Binary Mixture of Cadmium and Mercury Damages the Developed Ovary of Adult Zebrafish. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 44928–44938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liang, C.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Li, D.; Zou, W.; Wang, J.; Zong, K.; Liang, D.; et al. The Association between Essential Trace Element (Copper, Zinc, Selenium, and Cobalt) Status and the Risk of Early Embryonic Arrest among Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Techniques. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Flaws, J.A. Effects of an Environmentally Relevant Phthalate Mixture on Cultured Mouse Antral Follicles. Toxicological Sciences 2016, kfw245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Liu, C.; Qin, D.-Y.; Yuan, X.-Q.; Yao, Q.-Y.; Li, N.-J.; Huang, Y.; Rao, W.-T.; Li, Y.-Y.; Deng, Y.-L.; et al. Associations between Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations in Follicular Fluid and Reproductive Outcomes among Women Undergoing in Vitro Fertilization/Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Treatment. Environ Health Perspect 2023, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, H.; Martinez, S.; Farrell, R.; Bikienga, R.; Arinzeh, N.; Potts, C.; Li, Z.; Warner, G.R. Mixtures of Phthalates Disrupt Expression of Genes Related to Lipid Metabolism and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Signaling in Mouse Granulosa Cells 2024.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependence curve of the in vitro effects of DEHP on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in single metaphase II stage oocytes expressed as Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (A) and DCF (B) fluorescence intensities. Values are expressed as arbitrary densitometric units (ADU). Overlap coefficients of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros and DCF fluorescent labelling in oocytes cultured in presence of DEHP (C). Numbers of analyzed oocytes per group are indicated on the bottom of each histogram. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test, comparisons DEHP-exposed versus control; a,b P< 0.05 and a,d P < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependence curve of the in vitro effects of DEHP on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in single metaphase II stage oocytes expressed as Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (A) and DCF (B) fluorescence intensities. Values are expressed as arbitrary densitometric units (ADU). Overlap coefficients of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros and DCF fluorescent labelling in oocytes cultured in presence of DEHP (C). Numbers of analyzed oocytes per group are indicated on the bottom of each histogram. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test, comparisons DEHP-exposed versus control; a,b P< 0.05 and a,d P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of DEHP/Cd mixture on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in single metaphase II stage oocytes. Values are presented as means and standard deviations of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (A) and DCF (B) fluorescence intensities in arbitrary densitometric units (ADU). Means and standard deviations of overlap coefficients of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros and DCF fluorescent labelling in oocytes cultured are also presented (C). Numbers of analyzed oocytes per experimental condition are indicated at the bottom of each bar. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test, different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences: a, c P< 0.01 and a, d P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of DEHP/Cd mixture on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in single metaphase II stage oocytes. Values are presented as means and standard deviations of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (A) and DCF (B) fluorescence intensities in arbitrary densitometric units (ADU). Means and standard deviations of overlap coefficients of Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros and DCF fluorescent labelling in oocytes cultured are also presented (C). Numbers of analyzed oocytes per experimental condition are indicated at the bottom of each bar. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test, different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences: a, c P< 0.01 and a, d P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial distribution pattern and ROS localization in sheep matured oocytes exposed to DEHP/Cd mixture, DEHP and Cd. For each oocyte, corresponding UV light (A1, B1, C1, D1) and confocal laser scanning images showing mitochondrial distribution pattern (A2, B2, C2, D2), intracellular ROS localization (A3, B3, C3, D3) and mitochondria/ROS merge (A4, B4, C4, D4) are shown. Oocytes are representative of heterogeneous (perinuclear/subplasmalemmal; A) and homogeneous (B, C, D) mitochondrial distribution pattern, respectively. Scale bar represents 40 mm.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial distribution pattern and ROS localization in sheep matured oocytes exposed to DEHP/Cd mixture, DEHP and Cd. For each oocyte, corresponding UV light (A1, B1, C1, D1) and confocal laser scanning images showing mitochondrial distribution pattern (A2, B2, C2, D2), intracellular ROS localization (A3, B3, C3, D3) and mitochondria/ROS merge (A4, B4, C4, D4) are shown. Oocytes are representative of heterogeneous (perinuclear/subplasmalemmal; A) and homogeneous (B, C, D) mitochondrial distribution pattern, respectively. Scale bar represents 40 mm.

Figure 4.

Effects of DEHP/Cd mixture on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in CCs from sheep COCs expressed as Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (panel A) and DCF (panel B) fluorescence intensities in arbitrary densitometric units (ADU), overlap coefficient of mitochondria/ROS co-localization (panel C). Around 200 CCs per experimental condition were analyzed by LSCM. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test; different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences: a, d P<0.001.

Figure 4.

Effects of DEHP/Cd mixture on mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), intracellular ROS levels and mitochondrial/ROS co-localization in CCs from sheep COCs expressed as Mitotracker Orange CMTM Ros (panel A) and DCF (panel B) fluorescence intensities in arbitrary densitometric units (ADU), overlap coefficient of mitochondria/ROS co-localization (panel C). Around 200 CCs per experimental condition were analyzed by LSCM. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's post hoc test; different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences: a, d P<0.001.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of representative CCs from COCs of juvenile ewes, matured in vitro in presence/absence of DEHP and Cd. Lanes show representative CC fields taken, by laser scanning confocal microscopy, at the equatorial plane. In each field, all CCs included in the yellow defined boundary underwent quantification analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS levels and mt/ROS co-localization, whose results are presented in

Figure 4. In columns 1 and 2, cells stained with MitoTracker Orange and DCF are shown, respectively whereas column 3 shows the mitochondrial /ROS merge. Increased intracellular ROS levels (expressed as DCF fluorescent intensity) can be seen in the CCs exposed to DEHP/Cd mixture (B2) compared with the controls (A2). Scale bars represent 40 µm.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of representative CCs from COCs of juvenile ewes, matured in vitro in presence/absence of DEHP and Cd. Lanes show representative CC fields taken, by laser scanning confocal microscopy, at the equatorial plane. In each field, all CCs included in the yellow defined boundary underwent quantification analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS levels and mt/ROS co-localization, whose results are presented in

Figure 4. In columns 1 and 2, cells stained with MitoTracker Orange and DCF are shown, respectively whereas column 3 shows the mitochondrial /ROS merge. Increased intracellular ROS levels (expressed as DCF fluorescent intensity) can be seen in the CCs exposed to DEHP/Cd mixture (B2) compared with the controls (A2). Scale bars represent 40 µm.

Table 1.

In vitro effects of DEHP on oocyte nuclear chromatin configuration.

Table 1.

In vitro effects of DEHP on oocyte nuclear chromatin configuration.

| DEHP (µM) |

Total oocyte number |

Oocyte number (%) |

| Germinal Vesicle |

Metaphase I to

Telophase I |

Metaphase II and

1st Polar Body |

Abnormal |

| 0 (CTRL) |

78 |

9 (11) |

2 (3) |

53 (68) |

14 (18) |

| 0 (Vehicle CTRL) |

72 |

6 (8) |

5 (7) |

44 (61) |

17 (24) |

| 0.1 |

75 |

2 (3) |

6 (8) |

40 (53) |

27 (36) |

| 0.5 |

76 |

9 (12) |

10 (13) |

40 (53) |

17 (22) |

Table 2.

In vitro effects of DEHP on oocyte mitochondrial distribution pattern.

Table 2.

In vitro effects of DEHP on oocyte mitochondrial distribution pattern.

| DEHP (µM) |

Number of oocytes found at the MII

stage and evaluated |

Oocyte number (%) |

Perinuclear and

subplasmalemmal |

Small aggregates |

Abnormal |

| 0 (CTRL) |

53 |

27 (51) |

26 (49) |

0 (0) |

| 0 (Vehicle CTRL) |

44 |

21 (48) a

|

23 (52) a

|

0 (0) |

| 0.1 |

40 |

10 (25) #

|

27 (68) |

3 (7) |

| 0.5 |

40 |

8 (20) b

|

32 (80) b

|

0 (0) |

Table 3.

In vitro effects of DEHP/Cd mixture and individual compounds on oocyte meiotic maturation.

Table 3.

In vitro effects of DEHP/Cd mixture and individual compounds on oocyte meiotic maturation.

| Condition |

Total number of evaluated

oocytes |

Oocytes number (%) |

Germinal

Vesicle |

Metaphase I to

Telophase I |

Metaphase II and

1st Polar Body |

Abnormal |

| 0 (CTRL) |

121 |

11 (9) |

12 (10) |

73 (60) |

25 (21) |

| DEHP/Cd mixture |

120 |

9 (7) |

13 (11) |

73 (61) |

25 (21) |

| DEHP 0.5µM |

124 |

11 (9) |

17 (14) |

64 (52) |

32 (26) |

| Cd 0.1µM |

119 |

13 (11) |

8 (7) |

76 (64) |

22 (18) |

Table 4.

In vitro effects of DEHP/Cd mixture and individual compounds on oocyte mitochondrial distribution pattern.

Table 4.

In vitro effects of DEHP/Cd mixture and individual compounds on oocyte mitochondrial distribution pattern.

| Condition |

Number of MII

evaluated oocytes |

Oocyte number (%) |

Perinuclear and

subplasmalemmal |

Small

aggregates |

Abnormal |

| 0 (CTRL) |

49 |

22 (45) a

|

27 (55) a

|

0 (0) |

| DEHP/Cd mixture |

51 |

5 (10) d

|

42 (82) c

|

4 (8) |

| DEHP 0.5µM |

49 |

11 (22) b

|

38 (78) b

|

0 (0) |

| Cd 0.1µM |

53 |

12 (23) b

|

41 (77) b

|

0 (0) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).