Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Due to the bio-inert nature of titanium (Ti) and subsequent accompanying chronic inflammatory response, the implant’s stability and function can be significantly affected, leading in time to a poor osseointegration process. To overcome this challenge and improve the overall performance of Ti implants, various surface modifications have been employed, amongst them the deposition of titanium oxide (TiO2) nanotubes (TNTs) onto the native surface through the anodic oxidation method. While numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have already reported the importance of nanotube diameter on cell behaviour and osteogenesis, information regarding the effects of nanotube lateral spacing on the in vivo osseointegration process is insufficient and hard to find. Considering this, in the present study two types of TNTs with different lateral spacing, e.g. 25 nm (TNTs) and 92 nm (spTNTs) were fabricated and comparatively investigated in terms of their effect on the early peri-implant new bone formation. The microscopic examination at 1-month post-implantation revealed that both nanotubular surfaces, particularly spTNTs, were capable of inducing new bone formation without a significant bone destruction. Overall, our results indicate that the lateral spacing of the TNT-coated Ti surfaces can influence the in vivo outcome, thus representing a significant factor in implant design.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Implant preparation and characterization

2.2. Animals

2.3. Surgical procedure and post-operative care

2.4. Post-operative tissue harvesting

2.5. Histological examination

3. Results

3.1. TiO2 nanotubes

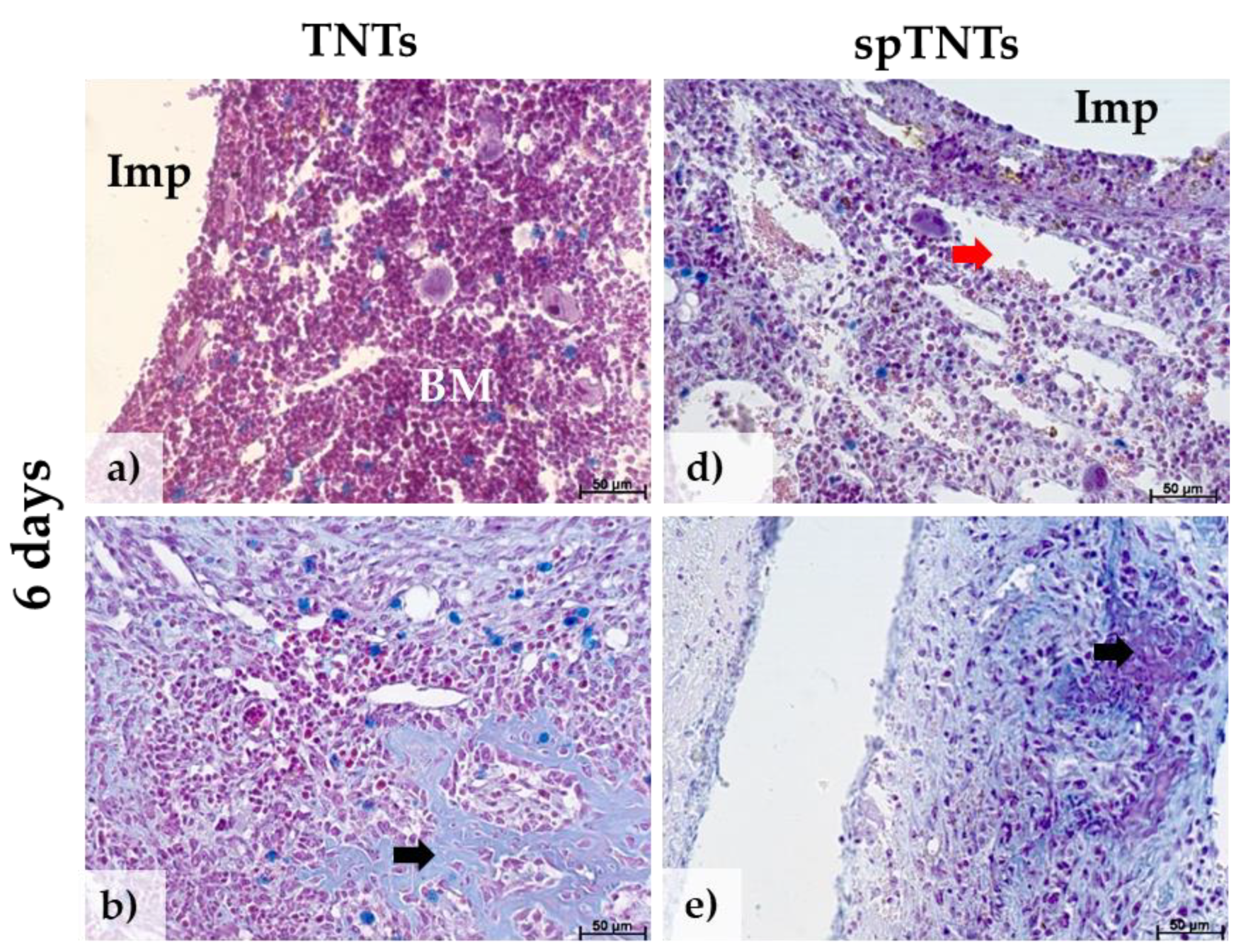

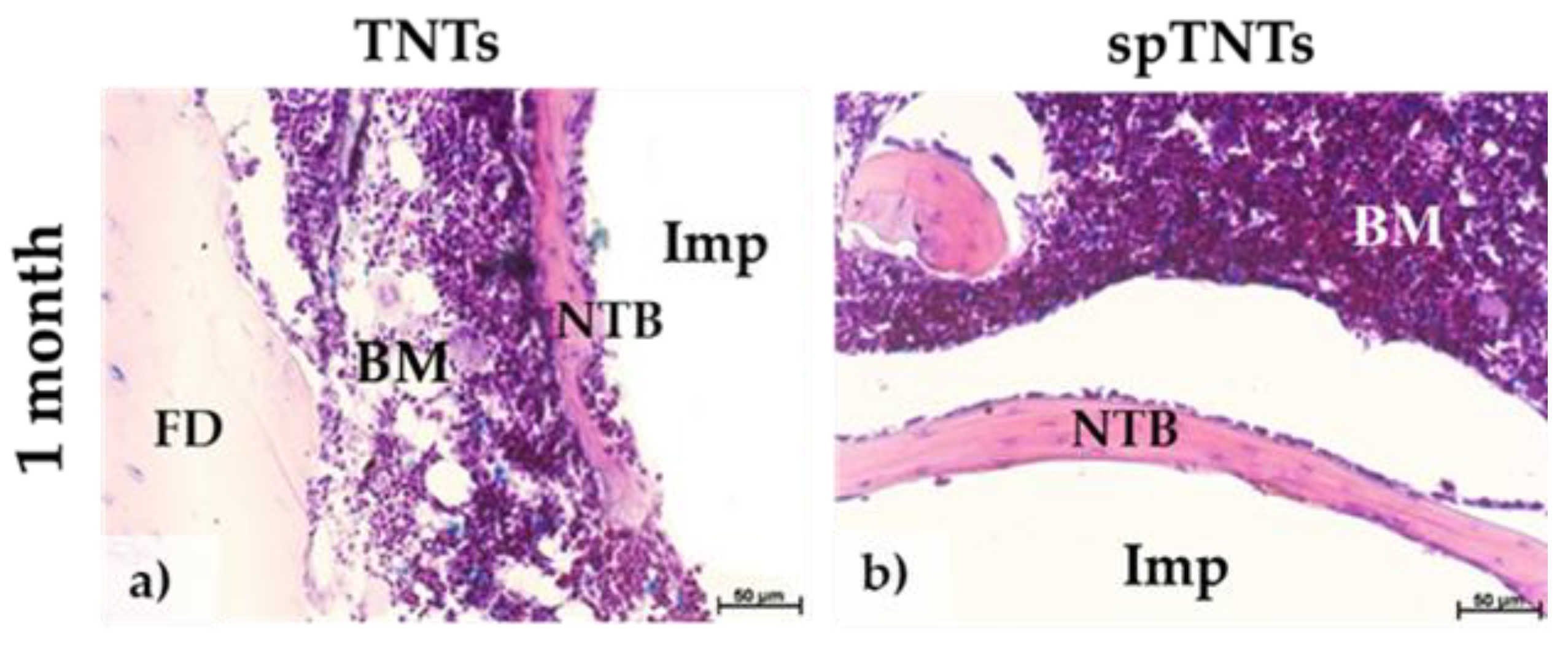

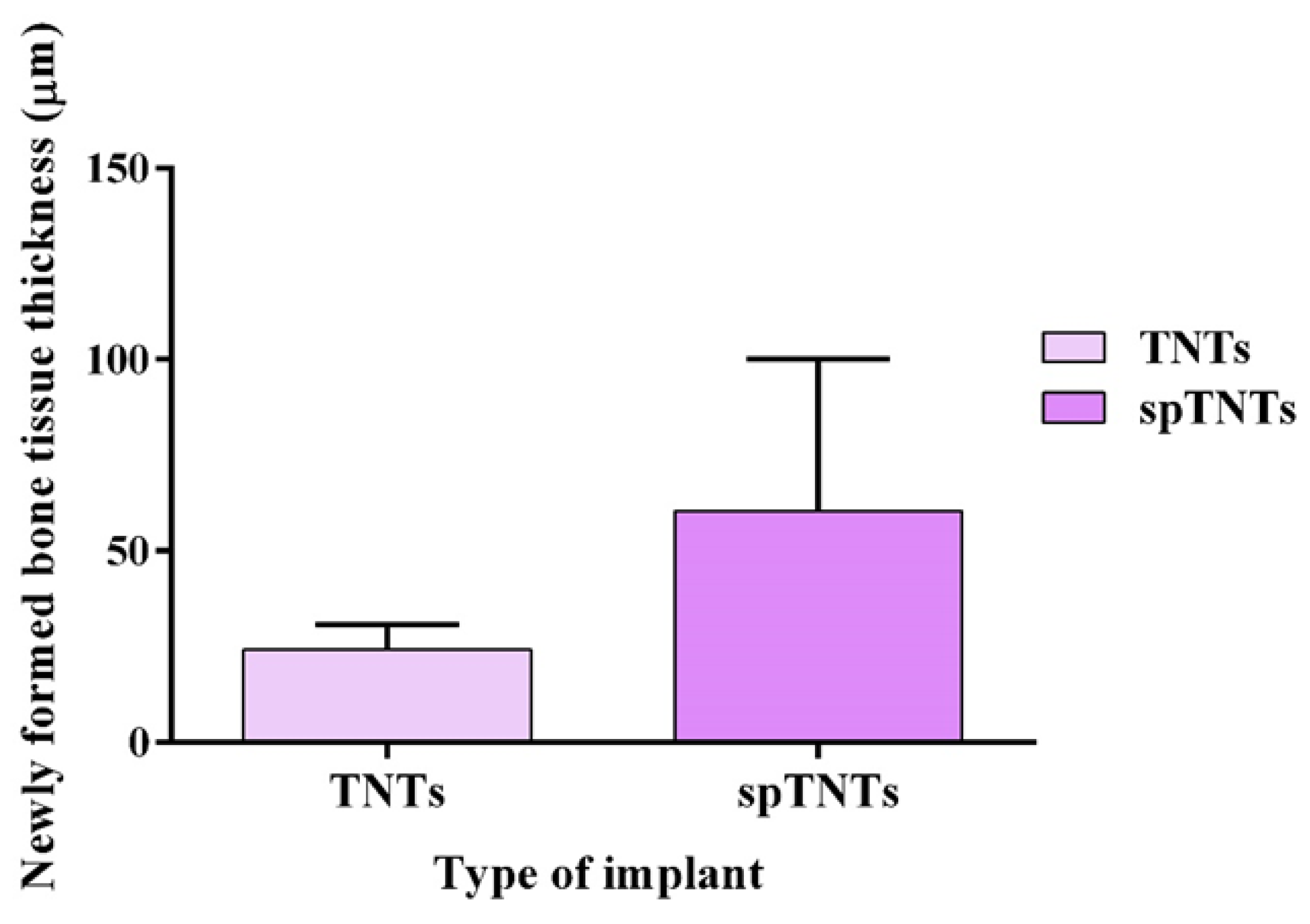

3.2. The histological appearance of the post-implant tissue

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, B.; Lan, H.; Zhou, X.; Lin, C.; Qin, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, A.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Jiao, Y.; Yi, W. Regulation of TiO2 nanotubes on titanium implants to orchestrate osteo/angio-genesis and osteo-immunomodulation for boosted osseointegration. Mater. Des. 2023, 233, 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, A.; Nicolau, P.; Guerra, F. Titanium dental implants with different collar design and surface modifications: a systemic review on survival rates and marginal bone levels. Clin. Oral Implan. Res. 2019, 30, 20–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, A.; Shang, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, B.; You, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. ; Li, C Icariin-Functionalised Coating on TiO2 Nanotubes Surface to Improve Osteoblast activity in Vitro and Osteogenesis Ability in Vivo. Coatings 2019, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, P.K.; Ding, C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2004, 47, 49–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, J.S.; Bowen, C.R.; Cartmell, S.H. Effect of TiO2 Nanotube Pore Diameter on human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Human Osteoblasts. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, H.; Ni, M.; Rui, Y.; Cheng, T.; Cheng, C.; Pan, X.; Li, G.; Lin, C. Enhanced osteointegration of medical titanium implant with surface modifications in micro/nanostructures. J. Orthop. Transl. 2014, 2, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmir, M.; Ercan, B. Anodization of titanium alloys for orthopedic applications. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2019, 13, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Berger, S.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 nanotubes: Synthesis and applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 2904–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necula, M.G.; Mazare, A.; Ion, R.N.; Ozkan, S.; Park, J.; Schmuki, P.; Cimpean, A. Lateral Spacing of TiO2 Nanotubes Modulates Osteoblast Behavior. Materials 2019, 12, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjursten, L.M.; Rasmusson, L.; Oh, S.; Smith, G.C.; Brammer, K.S.; Jin, S. Titanium dioxide nanotubes enhance bone bonding in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wilmowsky, C.; Bauer, S.; Lutz, R.; Meisel, M.; Neukam, F.W.; Toyoshima, T.; Schmuki, P.; Nkenke, E.; Schlegel, K.A. In Vivo Evaluation of Anodic TiO2 Nanotubes: An experimental Study in the Pig. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2009, 89, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.-G.; Park, Y.-B.; Choi, H.; Oh, S.; Lee, K.-W.; Choi, S.-H.; Shim, J.-S. Osseointegration of Implants Surface-treated with Various Diameters of TiO2 Nanotubes in Rabbit. Journal of Nanomaterials 2015, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, H.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Effects of TiO2 nanotubes with different diameters on gene expression and osseointegration of implants in minipigs. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6900–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, I.; Shim, S.-C.; Choi, D.-S.; Cha, B.-K.; Lee, J.-K.; Choe, B.-H.; Choi, W.-Y. Effect of TiO2 nanotubes arrays on osseointegration of orthodontic miniscrew. Biomed. Microdevices 2015, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Bauer, S.; Von Der Mark, K.; Schmuki, P. ; Nanosized and Vitality: TiO2 Nanotube Diameter Directs Cell Fate. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bauer, S.; Schlegel, K.A.; Neukam, F.M. Von Der Mark, K.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 nanotube surfaces: a 15nm-an optimal length scale of surface topography for cell adhesion and differentiation. Small 2009, 5, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, X.Q.; Zhan, F.Q.; Yu, W.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F. The effect of anatase TiO2 nanotube layers on MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts adhesion, proliferation and differentiation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 94, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Wang, J.; Guo, W. Effect of TiO2 Nanotubes on Biological Activity of Osteoblasts and Focal Adhesion Kinase/Osteopontin Level. J. Biomed. Technol. 2024, 20, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, K.S.; Oh, S.; Cobb, C.J.; Bjursten, L.M.; van der Heyde, H.; Jin, S. Improved bone-forming functionality of diameter-controlled TiO2 nanotube surface. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 3215–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Park, Y.; Choi, H.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Oh, S.; Shim, J. The Evaluation of Ossoeintegration of Dental Implant Surface with Different Size of TiO2 Nanotube in Rats. Journal of Nanomaterials 2015, 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wilmowsky, C.; Bauer, S.; Roedl, S.; Neukam, F.W.; Schmuki, P.; Schlegel, K.A. The diameter of anodic TiO2 nanotubes affects bone formation and correlates with the bone morphogenic protein-2 expression in vivo. Clin, Oral Implants Res. 2011, 23, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Necula, M.G.; Mazare, A.; Negrescu, A.M.; Mitran, V.; Ozkan, S.; Trusca, R.; Park, J.; Schmuki, P.; Cimpean, A. Macrophage-like Cells Are Responsive to Titania Nanotube Intertube Spacing – An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkan, S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P. Controlled spacing of self-organized anodic TiO2 nanotubes. Electrochem. Commun. 2016, 69, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Mazare, A.; Hahn, R.; Cerri, I.; Schmuki, P. Fast growth of TiO2 nanotube arrays with controlled tube spacing based on a self-ordering process at two different scales. Electrochem. Commun. 2017, 77, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Ozkan, S.; Hwang, I.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 nanotubes with laterally spaced ordering enable optimized hierarchical structures with significantly enhanced photocatalytic H2 generation. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 16868–16873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Cha, G.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 nanotubes with different spacing, Fe2O3 decoration and their evaluation for Li-ion battery application. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 195402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Valle, F.; Mazare, A.; Hwang, I.; Taccardi, N.; Zazpe, R.; Macak, J.M.; Cerri, I.; Schmuki, P. Optimized Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Electrode Using TiO2 Nanotube Arrays with Well-Defined Spacing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 4157–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P. Critical parameters and factors in the formation of spaced TiO2 nanotubes by self-organizing anodization. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 268, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.N.; Liu, M.N.; Wang, M.C.; Oloyede, A.; Bell, J.M.; Yan, C. Nnaoindentation study of the mechanical behavior of the TiO2 nanotube arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 118, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.B.; Silva, N.; Marques, J.F.; Mata, A.; Silva, F.S.; Carames, J. Biomimetic Implant Surfaces and Their Role in Biological Integration – A Concise Review. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Garcia, A.J. Biomaterial strategies for engineering implants for enhanced osseointegration and bone repair. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 2015, 94, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves-Rezende, M.C.; Capalbo, L.C.; De Oliveira Limirio, J.P.J.; Capalbo, B.C.; Limirio, P.H.J.O.; Rosa, J.L. The role of TiO2 nanotube surface on osseointegration of titanium implants: Biomechanical and histological study in rats. Micros. Res. Tech. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gao, S.; Lu, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, S. In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes with Superhydrophilic Surfaces during Early Osseointegration. Cells 2022, 11, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Kankala, R.K.; Lin, Q.; Shi, J.; Chen, C.; Luo, K.; Chen, A.; Zhong, Q. Surface-modified titanium and titanium-based alloys for improved osteogenesis: A critical review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; You, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Ding, L.; Li, J.; Xiao, C.; Han, F.; Li, B. Enhanced Ossoeintegration of Titanium Implants by Surface Modification with Silicon-doped Titania Nanotubes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 8583–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Al-Bishari, A.M.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Sheng, L.; Wu, G.; Lu, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, J. Ossoeintegration and anti-infection of dental implant under osteoporotic conditions promoted by gallium oxide nano-layer coated titanium dioxide nanotube arrays. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 22961–22969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.-S.; Bae, J.-M.; Park, Y.-B.; Choi, E.-J.; Oh, S.-H. Photobiomodulation-Based Synergic Effects of Pt-Coated TiO2 Nanotubes and 850nm Near-Infrared Irradiation on the Ossoeintegration Enhancement: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Shen, M.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X. A comparative study of Sr-loaded nano-textured Ti and TiO2 nanotube implants on osseointegration immediately after tooth extraction in Beagle dogs. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1213163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlekhan, A.; Takoudis, C.; Sukotjo, C.; Mathew, M.T.; Virdi, A.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Shokuhfar, T. Recent progress toward surface modification of bone/Dental implants with titanium and zirconia dioxide nanotubes fabrication of TiO2 nanotubes. J. Nanotechnol. Smart Mater. 2014, 1, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, R.J.; Bohner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bosshardth, D.D. Ostoeinduction and osteoimmunology: Emerging concepts. Periodontology 2000 2024, 94, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Du, Z.; Du, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, J.; Weng, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Yao, X.; Crawford, R.; Hang, R.; Huang, D.; Tang, B.; Xiao, Y. A multifaceted coating on titanium dictates osteoimmunomodulation and osteo/angio-genesis towards ameliorative osseointegration. Biomaterials 2018, 162, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonca, G.; Mendonca, D.B.; Simoes, L.G.; Araujo, A.L.; Leite, E.R.; Duarte, W.R.; Aragao, F.J.L.; Cooper, L.F. The effects of implant surface nanoscale features of osteoblast specific gene expression. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4053–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekaran, A.; Garcia, A.J. Nanoscale engineering of extracellular matrix-mimetic bioadhesive surfaces and implants for tissue engineering. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2011, 1810, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Li, H.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Effects of TiO2 nanotubes with different diameters on gene expression and osseointegration of implants in minipigs. Biomtaterials 2011, 32, 6900–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of implant | Newly formed bone tissue thickness (µm) |

|---|---|

| TNTs | 18.08 |

| spTNTS | 32.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).