Introduction

Japan has been widely acknowledged for its cultural vibrancy and technological progress but at the same time, numerous rural and island communities face significant demographic challenges such as aging populations and depopulations. These issues are more prominent on the smaller peripheral islands, where the effects of depopulation are intensified by geographical isolation (Qu et. al, 2024). To address these challenges, Japan has initiated various sustainability and revitalization efforts in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Funck, 2020). These efforts include strategies within the framework of SDG 3 - Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4 - Quality Education and SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities, with a rising emphasis on cultural initiatives such as community art and music festivals to also boost local and regional tourism (Qu & Cheer, 2021, Qu, 2020). These goals emphasize the importance of promoting healthy lives and well-being at all ages, and making human settlement inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable (United Nations General Assembly, 2015). One of such cultural initiatives are small-scaled community music festivals mainly featuring Western classical music, or simply classical music, and can be found in the rural and island communities in Japan. Western classical music is popular in Japan, largely because of the adoption and fascination with Western music during the modernization process beginning with the Meiji era (1868-1912), the incorporation of classical music into the education system to contribute to the physical, moral, and aesthetic education of Japanese citizens, and active promotion by the government (Mehl, 2013).

Studies have revealed that apart from the entertainment and education value, music festivals foster a sense of pride and belonging, promote social interaction, community interaction and well-being, and also improve community infrastructure (Chiya, 2024b; Ferranti, 2002; Lopes et al., 2017, Keyes et al., 2002; Ballantyne et al., 2014; Hull, 2012; Johnson, 2004; Rossetti & Quinn, 2021, Dodds et al., 2020). The contribution of music festivals to the well-being of local residents through cultural engagement and community participation aligns with SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being, and the contribution to tourism and establishment of collaborative production supports the objectives of SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities (Gibson, 2007; Dujmović, 2012). These social and cultural impact of music festivals underscore the potential of music festivals to contribute to the sustainability and resilience of rural communities (Quinn & Wilks, 2017).

Culture is often overlooked as the “fourth pillar” of sustainability that coexists alongside economic, social and environmental dimensions (Pop et al., 2019; James, 2014). It can also function as a resource or a tool to enhance sustainable development and achieve sustainable outcomes, and as a foundation to sustainability while encompassing all other sustainable practices (Soini & Dessein, 2016). By embracing these cultural dimensions, music festivals can foster sustainable and resilient rural communities.

This paper focuses on the impact of a rural island community music festival on three specific SDGs: 3, 4, and 11, on Kurahashi Island. The island festival is unique, as it was created as part of action research with a single goal of revitalizing Kurahashi Island through music (Kurahashi East-West Music Festival Executive Committee, 2023). It is also the only island community music festival in Japan which features a line-up of local and visiting performers, and amateur and professional musicians, and collaborative performances featuring both local and visiting performers.

Social Exchange Theory and SDGs

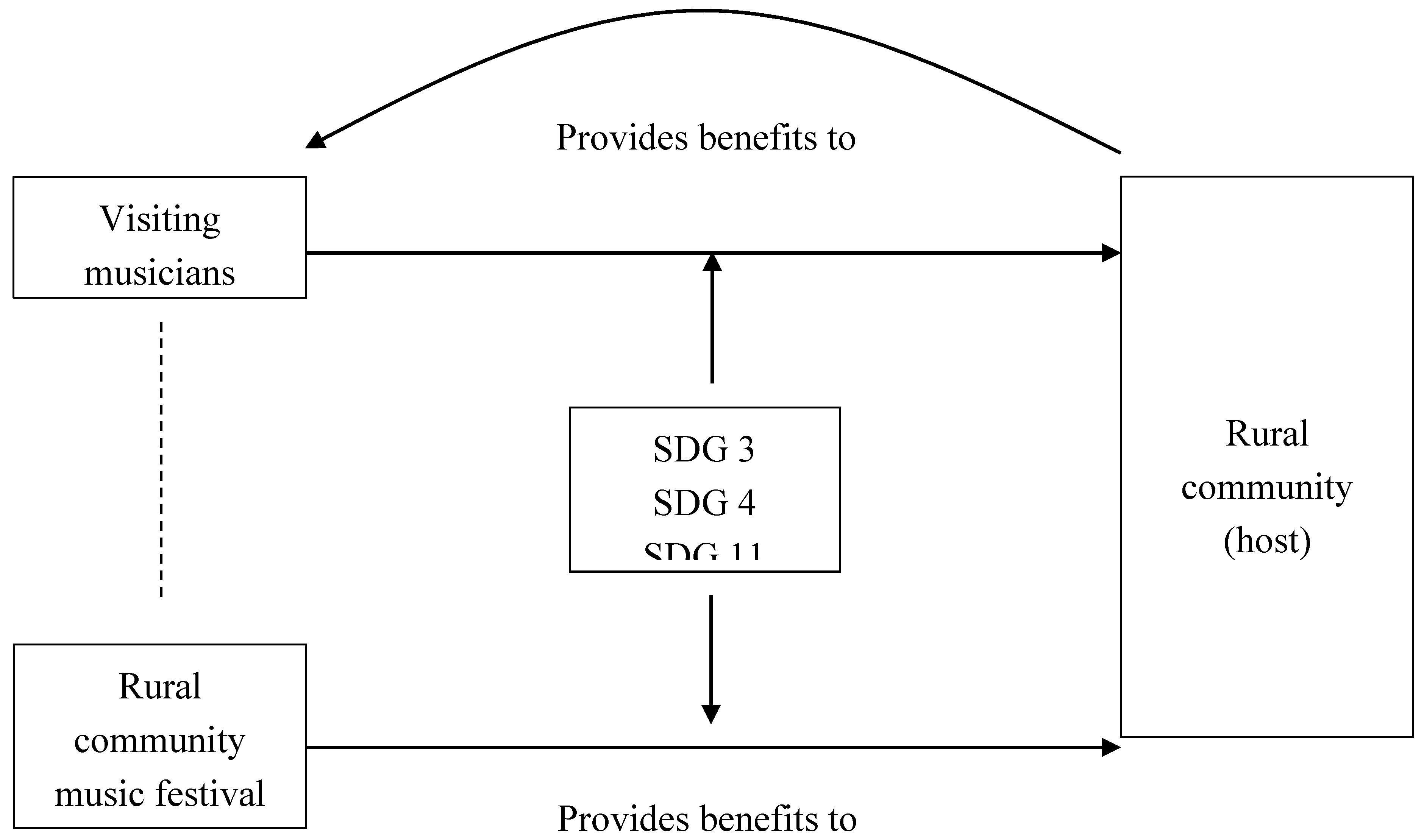

While the existing literature has examined and presented data on the social and cultural impact of music festivals on their host communities, there is a lack of social theories used to examine the social and cultural processes between the involved parties, particularly in rural and island communities. Defined as a concept of reciprocal exchange of material, social, or psychological resources among the involves parties (Ap, 1992), the social exchange theory (SET) provides a useful framework as an analytical lens together with the SDGs to examine the dynamics of relationships and interactions between a music festival and the host community. This theory presents a process consisting of four stages, beginning with the initial motivation to interact based on fulfilling specific needs, and progressing to the evaluation of the benefits, potential rewards, and consequences of such interactions (Ap, 1992). The flexibility of this process provides a unique focus on the exchanges among individuals and groups and how the benefits are aligned with the SDGs targets and indicators (Brinberg & Castell, 1982).

Although SET has been used in the field of tourism to assess residents’ perceptions in terms of cost, benefits, and motivations (Moyle et al., 2010; Kayat, 2002; Nunkoo & Gursoy, 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2017; Dillette et al., 2017; Nunkoo et al., 201; Long et al., 1990), the theory has not been used to explore the benefits of music festivals in the context of SDGs and sustainable community development of rural communities. Based on the literature employing SET to examine social exchanges in rural and island communities, research has revealed that such exchanges significantly contribute to regional development, community interaction, cultural identity, and well-being (Chiya, 2024; Dillette et al., 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2017; Moyle et al., 2010). However, the concepts of equity and reciprocity in SET suggests that relationships are more satisfying when there is a perceived fairness in exchange. This reciprocity do not adequately reflect cultural processes (Molm, 1997). What is considered equitable or reciprocal can vary significantly across different cultural contexts, challenging the universality of SET, and may not fully represent the depth of cultural engagements at music festivals (Molm, 1997).

One primary criticism is the theory’s overemphasis on rationality, assuming that individuals consistently engage in rational decision-making to maximize benefits and minimize costs (Homans, 1958). SET does not adequately account for the decisions which people often make while influenced by emotions, cultural norms, and psychological biases, and neglects the complexity of human emotions and irrational behaviors (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). SET also neglects altruism and unselfish behaviors, and predominantly considers social interactions as transactions where individuals seek personal gain. The theory fails to explain why people sometimes act selflessly, even at a personal cost (Clark & Mills, 1979). It also struggles to accommodate prosocial behaviors driven by intrinsic rewards such as when visiting performers perform for personal satisfaction or moral obligations to provide a cultural experience to a community (Hess 2010; Kennedy, 2002; Parkes & Jones, 2011; Leck, 2012; Molm, 2003; Gouldner, 1960). The theory assumes that individuals have access to complete information and can predict the outcomes of their interactions, oversimplifying complex human motivational factors into basic cost-benefit terms, and is unable to capture the full range of the multi-faceted, psychological, social, and existential dimensions of human motivations (Lawler & Thye, 1999; Blau, 1986; Emerson, 1976).

SET’s emphasis on individualistic, calculated exchanges and cultural and contextual insensitivity may not hold in collectivists cultures such as in rural and island communities, where communal values and collective harmony often take precedence over individual benefits (Gudykunst & Nishida, 1983). Furthermore, SET does not always account for the complex social and power dynamics and resource disparities present in different social and cultural settings, potentially leading to an incomplete understanding of social and cultural interactions (Molm, 1997). The theory acknowledges that power imbalances can affect exchanges with those possessing greater resources wielding more influence (Emerson, 1976), and SET’s cost-benefit analysis is often unable to predict certain outcomes with factors affecting the fairness and reciprocity of interactions (Cook & Rice, 2006).

With its limitations, SET would be more useful as a theoretical lens with the SDGs to enrich its applicability in analyzing the contributions of a music festival to a rural island community’s social and cultural sustainability. These SDGs, particularly SDG 3 - Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4 - Quality Education and SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities, provide a comprehensive framework through its targets and indicators that extends SET’s focus on cost-benefit analysis to include broader consideration of well-being, community resilience, and cultural vitality (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Music Festival and Rural Island Community Exchange with SDGs.

Figure 1.

Music Festival and Rural Island Community Exchange with SDGs.

SDG 3 aims to ensure health and well-being, with Target 3.4 that include the promotion of mental health and well-being. However, the indicators currently associated with Target 3.4 does not evaluate and track other factors of mental health and well-being, apart from Indicator 3.4.2 which measures the rate of mortality from suicides. Incorporating SDG 3 into SET can help to better analyze how a rural music festival might contribute to the community’s health and well-being through cultural events and leisure activities. These events are known to have significant positive impact on mental health, well-being, and social cohesion by providing communal experiences that potentially reduce feelings of isolation, which is a factor in suicide rates (Batt-Rawden & DeNora, 2005; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Evaluating how these events contributes to mental health also provides a more comprehensive understanding of the intrinsic benefits, such as increased community well-being, that the community members might perceive against any potential costs.

SDG 4 aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote not only lifelong learning opportunities for all but also broader developmental skills such as cultural appreciation (United Nations, 2015). Integrating SDG 4 into SET can allow us to examine the exchanges between visiting musicians and local communities in terms of educational benefits. Music festivals often provide unique, non-formal education opportunities that are not available in traditional school settings. This includes opportunities for practical skill development from visiting artists, and cultural education by understanding and appreciating different music narratives and hence, can contribute to lifelong learning and community inclusion (Qu et al., 2024; Castro-Martínez et. al, 2022). However, while Target 4.7 aims to promote appreciation of cultural diversity and culture’s contribution to sustainable development, none of the current targets and indicators of SDG 4 are aligned with arts education such as music, which is underscored by its role in enhancing overall educational achievements, psychological development, and other related skills. Linking SDG 4 with SET also provide insights to the intrinsic rewards to individuals and extrinsic benefits to the community such as cultural awareness and educational attainment, and how the reciprocity in these exchanges can foster sustainable outcomes for the rural communities.

SDG 11 focuses on sustainable cities and inclusive and resilient communities, with Targets 11.3, 11.4, 11.a and 11.b relevant to the social and cultural impact of music festivals. Target 11.3 seeks to enhance inclusive and sustainable settlement planning and management, Target 11.4 aims to increase efforts to preserve cultural and natural heritage, Target 11.a supports positive social connections between urban and rural areas, and Target 11.b aims to increase the number of communities adopting policies which promotes inclusion and resilience. For rural island communities hosting music festivals, integrating these targets into SET analysis can help to better assess how cultural exchange at such events contribute to the social and cultural sustainability of the community as there is currently an absence of relevant indicators that effectively measure or track social inclusion, preservation of local cultural heritage and the enhancement of local spaces (Chatterton & Hollands, 2003). Even though Indicator 11.4.1 tracks the preservation of cultural and natural heritage, it only does so by the total expenditure by source, type, and level of funding. There are no specific indicators to measure the preservation of intangible cultural heritage in a community, such as local music practices. There are also no indicators monitoring social inclusion on the community level, with only 11.b.1 and 11.b.2 tracking the total number of countries and local governments implementing policies which promotes resilience and inclusion.

By integrating three SDGs into an adapted version of SET, this paper aims to analyze the exchanges associated with a music festival in a rural island community, and explore its sustainability goals and challenges.

Methodological Framework

This paper uses Participatory Action Research to create and organize a three-day music festival in the town of Kurahashi (Kurahashi-cho) on Kurahashi Island to explore its impact on sustainability. Kurahashi Island is located off the coast of Kure City in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. It is known as the hometown of the envoys sent to Tang China, for its shipbuilding industry, and for its specialty goods such as oysters, tomato, and mandarin oranges. Facing severe depopulation and aging population in the last 25 years, its current population is 4454 people and an elderly percentage of 54%, compared to Japan’s total percentage of 28.9% (Kure City Civic Affairs Division, 2024). To create new appeal and bring vitality back to the region (Kurahashi East-West Music Festival Executive Committee, 2023), the Town Development Council on the island formed a partnership with Hiroshima University to plan and implement a music festival. The music festival consisted of three major events: a music workshop, a concert, and an opera performance. Each event was held on one day, and did not overlap with each other.

I was first approached by a member of a Hiroshima non-governmental organization focusing on revitalization projects in rural areas in April 2023 as a cultural advisor. The initial proposed project was to revive a series of classical music events at the old quarry in Kurahashi, which used to be held in the 1980s. After doing a feasibility study and follow-up consultations with the committee, it was decided that accessibility to the old quarry, which is located up a hill, is limited, and the benefits does not outweigh the cost of creating new infrastructure at the quarry to accommodate a performance space and audience. Hence the multi-purpose hall of the local onsen (hot spring bath) resort and at the local middle and high school were decided as venues of the music festival. After converting the hall into a performance space, the hall was able to accommodate up to 150 guests. The seating plan of the performance hall was also more intimate, as there was no stage and attendees were seated closer to the performance. I officially joined the festival committee in August 2023 as an advisor and sustainability researcher, and my work was pro bono. Subsequent field trips were conducted between August and September 2023 to consider about the SDGs which are most relevant to revitalization in the rural island community context. The SDGs were narrowed down to SDG 3 - Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4 - Quality Education, and SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities. Focusing on the targets of these SDGs, I planned and conducted a musical clinic and conducting workshop, and a performance with invited guests and local musicians at the music festival on two separate days in the first weekend of October 2023 (

Table 1). An opera performance was held on the last day, and it was separately planned and organized by another unrelated team at Hiroshima University.

The musical clinic and conducting workshop was conducted at the music room in the local combined middle and high school (

Figure 1). I was first invited to visit the middle and high school on 19 September 2023, and a workshop was decided after consultations with the school’s sole music teacher and vice-principal. The goal of the workshop was to provide a music experience and training from a professional musician, which the rural middle and high school has limited access to. A total of 28 high school students with an average age of 13 years old participated in this event. I first spent 10 to 15 minutes introducing my background as a professional conductor and researcher and sharing some insights to my profession. I then shared some of my own professional conducting videos as well as other professional conductors to demonstrate certain conducting techniques and musical expression for the students to observe and learn. The workshop continued with an introduction to Alexander Technique for all the participating students, which lasted about 15 minutes. A choir conducting masterclass continued next, with only one participating student conductor. The student conductor was a male senior high school student, and was first asked to conduct a short piece with the choir, made up of the other students of the workshop, while the school’s music teacher accompanied the choir on the grand piano. The music piece was approximately 4 minutes long, and sung entirely in Japanese. After the student’s conducting, I analysed his techniques and gave the student conductor instruction and comments on how to improve his conducting technique, based on the Ilya Musin manual technique of conducting. This section of the workshop lasted approximately 30 minutes. I spent the next 15 minutes conducting the choir, giving advice on how to improve their singing in the art of Bel Canto, also known as an Italian style of operatic singing, and to increase their skills and abilities for an upcoming choir competition. The workshop ended with the students providing their reflections and feedback on the activities during the event. These feedback statements and informal conversations were collected as data for analysis.

Figure 1.

The music clinic and workshop. Kurahashi Middle and High School (2023).

Figure 1.

The music clinic and workshop. Kurahashi Middle and High School (2023).

The concert in the performance hall of the local onsen resort facility involved members of the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra from Hiroshima City, and local musicians of Kurahashi. The Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra is the oldest community orchestra in Hiroshima City and consists of both amateur and professional musicians, and hence is classified as a semi-professional community orchestra. The orchestra does not receive any financial support from any public or private organizations, and the members of the orchestra pay a fee whenever they perform a concert. Since the orchestra is a non-profit organization, the fees contribute to the rental of rehearsal spaces, the performance venue, and other promotional materials for the concerts they perform. The Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra was chosen as a guest ensemble after consultations with the festival committee, due to it being the most feasible option while bringing a high level of music performance to the island. However, due to the space constraints at the performance venue, the full orchestra was not invited to the festival. Only 26 members of the orchestra forming a chamber orchestra participated and performed at the music festival. All the visiting musicians, was not paid a fee for their performance at the music festival.

As the concert focused on SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities as a framework with SET for community revitalization and sustainability, local performing groups were also chosen and invited to the music festival. A taiko (Japanese drum) and shinobue (Japanese flute) pair comprising of a local father and son, and an amateur wind ensemble called the Blue Marine Ensemble comprising of local community residents were invited to perform at the festival. Both performed in the first half of the concert, with the taiko and shinobue pair performing the opening act, and the Blue Marine Ensemble performing a few pieces of popular Japanese music next. The Blue Marine Ensemble was also invited to rehearse and perform in a combined performance with the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra at the end of the concert. This aligns with the targets for inclusion and preservation of local culture under SDG 11. Apart from the taiko and shinobue music, I made all decisions on the repertoire for the concert. The most popular excerpts from the autumn concert of the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra and popular Japanese music for the Blue Marine Ensemble were chosen after deliberations with the musicians as they would provide the best experience for the audience. Data of the study was collected through informal conversations during the music festival and semi-structured interviews with the members of the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra after the music festival. The interviews involved 20 participants of the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra who gave their consent to participate. The other 6 members of the orchestra did not participate in any interviews nor conversations. The interviews were conducted in Japanese and followed the SET framework with questions on the perceived cost and benefits from the musicians’ participation and performance at the music festival.

Additional qualitative data for the study was also collected through surveys and report documents. A survey with both Likert-scale and open-ended questions was given to the audience at the performance. A total of 89 responses were collected. The festival committee also convened after the music festival for an evaluation and to start planning for the next festival, and the discussion culminated in a evaluation report as well as a presentation of some preliminary observation. The types of data collected for this study are illustrated in

Table 2. These data were all collated, translated and transcribed by a native speaker for content and thematic analysis, and thematically coded into their costs and benefits in the framework of SET and the targets of the aligned SDGs.

The Festival and SDG 3

The role of music festivals in promoting well-being is increasingly discussed. Keyes et al. (2002) and Packer et al. (2011) suggests that participation in music festivals leads to a significant increase in well-being, and contributes to personal growth and emotional enrichment. Attending music festivals also enables individuals to form new social connections, enhance emotional well-being, and foster personal development (Chiya, in press).

The impact of festival events extends beyond the ephemeral experience of the concert itself. While interacting in conversations with the local residents post-concert, many of them expressed their gratitude for the opportunity to experience professional performances intimately, which was rare in their rural community:

“I am very grateful for the opportunity to attend a concert, which is not often available in the countryside.”

“It’s great to hear this kind of music in the community.”

“The music of the orchestra, we don’t usually get to hear them in this community.”

“I was surprised to hear a real concert in Kurahashi.”

“It was great to hear a professional performance, as we don’t get to hear such performances on the island.”

They also expressed how therapeutic it was to have live performances in their rural community. Many attendees described the live music having a healing effect and deep impact on their emotional expression. These emotional resonance from the performance is illustrated in the following quotes:

A Likert-scale audience survey conducted during the festival also reflected a high degree of satisfaction among the attendees who are local residents (n=89). 94.3% (n=84) reported being “extremely satisfied” with the concert experience, while 5.6% (n=5) indicated they were “somewhat satisfied.” There were no neutral or negative responses. This satisfaction from the fulfilment of desire for entertainment and pleasure suggests a significant positive emotional impact such as joy and happiness (Packer & Ballantyne, 2011).

The visiting musicians also expressed a deep sense of fulfillment and purpose in exchange for their participation in the festival. Some of the visiting musicians noted personal and professional benefits from participating and performing at the music festival:

“I benefited from the experience and fulfilment in performing.” (Male, 55)

“I had a fulfilling experience and interaction with people while sharing music.” (Female, 32)

“I had an enjoyable and great time with the audience and my fellow performers.” (Male, 38)

These quotes highlight the reciprocal nature of joy and satisfaction experienced at the music festival between audience and performer, and underscores how the social interaction between musicians who share similar artistic ideals and passions fosters social well-being (Ballantyne et al., 2014). Furthermore, the festival atmosphere offers opportunities for learning and cultural exposure, which are key factors in enhancing subjective well-being (Chiciudean et al., 2021). The satisfaction of desires for entertainment and emotional engagement, emotional healing, social interaction, and cultural enrichment demonstrates how participating at music festivals can enhance individual and communal well-being through a mutually beneficial exchange between the local community and visiting performers.

The Festival and SDG 4

Participating in a rural music festival presents an intersection of cultural engagement and educational development, which impacts both visiting musicians and the local community in the context of SDG 4 - Quality education. Through performances, workshops, and collaborative experiences, musicians and students participating in the festival workshop engage in educational exchange that benefits both parties. As a visiting musician and workshop facilitator at the festival, my role encompassed both entertainment and education, or “edutainment”. I provided an educational space where the students can have a deeper understanding of the intricacies of music professions, the demystification of roles such as orchestra conductors, and offered students hands-on experiences that are rarely available in their usual educational settings, as their teacher stated:

By facilitating a deeper cultural exchange and providing educational enrichment at the festival workshop, I fostered practical skills and artistic insights in the participating students. This is illustrated in the students’ feedback:

“I thought conducting looked easy, but I realized it is very difficult, and I learnt a lot today.”

“It is rare for us to learn from a professional musician in Kurahashi.”

Such experiences not only enhance their understanding of music, but also foster critical skills like emotional expression and leadership (Creech et al., 2016; Hall, 2008). In exchange, it enabled me to adapt and refine my teaching approaches to meet the specific needs of this rural student population. These skills, such as adaptability and the development of heuristic teaching methods, are vital for educators working in diverse and dynamic environments (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

Visiting musicians also exchange their cultural knowledge through edutainment for human capital. By engaging with diverse audiences and collaborating with fellow artists, musicians enhance their professional skills and personal growth. These experiences can be invaluable as they extend beyond traditional performance environments. The amateur musicians invited benefitted from the collaboration with other professional artists, an experience which they would not necessarily have at major festivals where only internationally well-known performers are invited (Chiya, 2024). Some of the musicians reflected that:

“There are positive changes to the way I perform, such as better presentation, better stage presence.” (Female, 43 years old)

“I benefitted from being able to learn from and perform with a well-known and excellent world-class musician at the festival.” (Female, 56 years old)

“I gained valuable experience while sharing music” (Female, 32 years old)

“I am glad I had the opportunity to perform with other professional musicians” (Male, 38 years old)

The orchestra also performed the repertoire in a more exciting and vibrant interpretation in alignment with the theme of a festival. The tempo of the music was a little faster, the articulation was more pronounced, and the dynamics were in wider contrast to appeal to the local rural community. This liberal approach at the festival differs from the more formal and historically accurate performances in concert halls in larger cities, where the audience are more informed and usually expect a respectful approach to the music. Hence, performing at the festival also broadened the adaptability of visiting musicians, preparing them to meet the different demands of their artistry across various contexts.

The Festival and SDG 11

Music festivals play a role in fostering community resilience through inclusion and pride, aligning with SDG 11 - Sustainable cities and communities (Chiya, in press). In exchange for providing resources such as the venue, local promotion, and audience from the community, festival in Kurahashi offered cultural enrichment and fostered a sense of belonging and identity among residents through the integration of cultural diversity and community inclusion. This aligns with Target 11.3 and 11.b which involves inclusivity planning and promotion. Local residents who participated in the festival expressed significant appreciation for the blend of local Japanese and Western, and local pride for the inclusion of their own music ensembles:

“Japanese and Western music, each was very good to listen to.”

“It was wonderful to include the local wind ensemble, and to perform with the visiting musicians.”

“It was good to see some Kurahashi tradition integrated with the festival, and I would like to see more.”

“It was good to include the local people and perform with them.”

The inclusion of two local performance groups, in particular the Japanese taiko and shinobue, not only preserved local cultural heritage but also enhanced community pride in local cultural representation. The local Japanese traditional performing groups on the island are currently facing extinction due to the lack of any successors and opportunities to perform to a wider audience. Integration of these groups into music festivals is not only crucial in maintaining cultural diversity but also the cultural sustainability of the community. Local residents also expressed interest in seeing and listening to more local tradition during both festival and non-festival events on the island, meeting Target 11.4 to increase efforts in the preservation of cultural and natural heritage.

Content and textual analysis of the festival reports reveal that local businesses such as the local cafes and onsen resort, and other community volunteers were involved in the planning and execution of the festival. While the inclusion and involvement of the local community supported local economy and encouraged collaboration among the various stakeholders, one of the festival committee members noted that:

As the festival was organized by a local non-governmental organization, the promotion campaign was carried out by local volunteers, which was significantly difficult in the rural area of Kurahashi. However, the festival planning and management by the community not only strengthened the resilience and resourcefulness of the community but also contributed to local tourism, further aligning with Target 11.3 (Chiya, in press; Norris et al., 2008). As I walked around the town during the festival, I saw different groups of visiting musicians and festival tourists in different local establishments, enjoying the local cuisine and purchasing souvenirs, walking along the beach, and using the hot springs at the resort. Through my conversations with the visiting musicians (n=20), 95% (n=19) expressed a wish to return to explore the island before the next festival, emphasizing that they want to visit the hot springs again, try more local cuisine, purchase the local produce, enjoy the sea and the beach, and discover other local attractions. 5% (n=1) would not want to visit the island for tourism due to the distance to the city in the mainland, and the lack of frequent public transport. However, all the visiting musicians with whom I spoke to share the same wish to participate and perform at the festival again without any moral obligation to reciprocate exchanging their cultural knowledge for the provision of resources such as venue and tourism and personal satisfaction (Chiya, 2024). In these exchanges, the local community also develops positive social and cultural connections with the urban areas through the musicians, aligning with Target 11.4.

Conclusion

This study attempts to explore how the impact of a rural island community music festival can be closely aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals for the revitalization of their community. This paper also attempts to fill the gap between community music, sociology, sustainable development, and rural revitalization by exploring the impacts through an adaptation of the Social Exchange Theory framework and three specific SDGs: SDG 3 - Good health and well-being, SDG 4 - Quality education and SDG 11 - sustainable cities and communities. By using a Participatory Action Research approach and a qualitative analysis of the festival’s activities, this paper has identified key benefits in terms of community engagement, educational opportunities, and community resilience. Together with a more intimate music performance setting and recognizable music, the festival created an environment that promoted well-being and emotional enrichment among the community through the enhancement of the attendees’ social connections and emotional health. The educational workshop which was part of the festival offered the students who participated practical skill development and cultural education, and the performances also fostered a deeper understanding of music in the attendees. These unique learning experiences contribute significantly to quality education. The festival also promoted inclusivity and resilience through its programming and involvement of local stakeholders, reinforcing community pride, fostering inclusion, and contributing to sustainable planning and management.

For future rural music festivals aiming to leverage activities and events for sustainable development of the host community, it is essential to integrate the SDG frameworks more actively into festival planning to align with the specific needs and sustainability goals of the community. Such diverse and inclusive programming will not only enhance more purposeful community engagement and educational outreach but also foster more resilient and vibrant communities.

However, while the findings of this study illustrates the potential of rural music festivals in sustainable development and revitalization of rural communities, the specific focus on a rural Japanese setting limits the generalizability of findings to other geographical and cultural contexts, such as Europe, Australia, or even other parts of Asia like China. The different social and cultural landscapes may influence the efficacy and impact of other similarly designed music festivals.

Future studies should explore the nature of social and cultural exchanges, such as personally generalized exchanges (Sintas et al., 2012) in the context of music festivals in more detail to understand the broader impact on the host community. Additionally, examining the integration of other SDGs into the framework of the production process of a music festival can provide comprehensive insights into the benefits of music festivals in community revitalization strategies.

Acknowledgment

This research was assisted by Jenny Yamamoto and supported by the Kurahashi Exchange Hub Initiative Promotion Council, Kurahashi East-West Festival Executive Committee, Regional Quality of Life Institute (Hiroshima), the Kurahashi community, Taufik Hidaya, and the Hiroshima Tafel Orchestra.

References

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, J., Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. (2014). Designing and managing music festival experiences to enhance attendees’ psychological and social benefits. Musicae Scientiae, 18(1), 65–83. [CrossRef]

- Batt-Rawden, K. B., & DeNora, T. (2005). Music and informal learning in everyday life. Music Education Research, 7(3), 289-304. [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. (1986). Exchange and Power in Social Life (2nd ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Brinberg, D. and Castell, P. (1982), ‘‘A resource exchange theory approach to interpersonal interactions: a test of Foa’s theory’’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 43 No. 2, pp. 260-9.

- Castro-Martínez, E. , Recasens, A., & Fernández-de-Lucio, I. (2022). Innovation in early music festivals: Domains, strategies and outcomes. In E. Salvador & J. Strandgaard Pedersen (Eds.), Managing cultural festivals: Tradition and innovation in Europe (pp. 74-86). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, P. , & Hollands, R. (2003). Urban nightscapes: Youth cultures, pleasure spaces and corporate power. London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Chiciudean, D.I. , Harun, R., Mureșan, I.C., Arion, F.H., & Chiciudean, G.O. (2021). Rural Community-Perceived Benefits of a Music Festival.

- Chiya, A. (2024a). The role of rural music festivals in community resilience, resourcefulness, and well-being. The International Journal of Social Sustainability in Economic, Social, and Cultural Context.

- Chiya, A. (2024b). Harmonizing visiting performers’ motivations and community revitalization at a rural island music festival. International Journal of Event and Festival Management. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (1979). Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(1), 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S. , Rice, E. (2006). Social Exchange Theory. In: Delamater, J. (eds) Handbook of Social Psychology. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Creech, A., Hallam, S., McQueen, H., & Varvarigou, M. (2016). The power of music in the lives of older adults. Research Studies in Music Education, 35(1), 87-102. [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874-900. [CrossRef]

- Dillette, A. , Douglas, A., Martin, D.S., & O'Neill, M. (2017). Resident perceptions on cross-cultural understanding as an outcome of volunteer tourism programs: the Bahamian Family Island perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25, 1222 - 1239.

- Dodds, R. , Novonty, M., & Harper, S. (2020). Shaping our perception of reality: Sustainability communication by Canadian festivals. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 11(4), 473–492. [CrossRef]

- Dujmović, Mauro and Vitasović, Aljoša (2012) Festivals, local communities and tourism. In: Conference Proceedings Soundtracks: Music, Tourism and Travel Conference. Leeds: International Centre for Research in Events, Tourism and Hospitality (ICRETH), Leeds Metropolitan University, UK, Liverpool. ISBN 978-1-907240-31-7.

- Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335-362. [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, H.D. (2002). ‘Japanese music’ can be popular. Popular Music, 21, 195 - 208.

- Funck, C. (2020). Has the island lure reached Japan?: Remote islands between tourism boom, new residents, and fatal depopulation. In Japan’s new ruralities (pp. 177-195). Routledge.

- Gibson, C.R. (2007). Music Festivals: Transformations in Non-Metropolitan Places, and in Creative Work. Media International Australia, 123, 65 - 81.

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161-178. [CrossRef]

- Gudykunst, W. B., & Nishida, T. (1983). Social penetration theory and self-disclosure in cross-cultural contexts. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 7(2), 241-267. [CrossRef]

- Hall, J. L. (2008). The sound of leadership: Transformational leadership in music.

- Hess, J. (2010) "The Sankofa drum and dance ensemble: Motivations for student participation in a school world music ensemble”. Research Studies in Music Education, 32, 23-42.

- Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597-606. [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.S. , & Sassenberg, U. (2012). Creating new cultural visitor experiences on islands: Challenges and opportunities.

- James, P. (2014). Urban sustainability in theory and practice: circles of sustainability. Routledge.

- Johnson, H. (2004). To and from an Island periphery: Tradition, travel and transforming identity in the music of Ogasawara, Japan. World of Music, 46, 79-98.

- Kayat, K. (2002), ‘‘Power, social exchanges and tourism in Langkawi – rethinking residents’ perceptions’’, International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 171-91.

- Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimising well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022.

- Kennedy, M.A. (2002) "‘It’s cool because we like to sing’: Junior high school boys’ experience of choral music as an elective”. Research Studies in Music Education, 18, 24–34.

- Kurahashi East-West Music Festival Executive Committee. (2023). [Implementation plan of the Kurahashi East-West Music Festival]. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- Kure City Civic Affairs Division. (2024). Population and household numbers in Kure City as of April 2024 [Reiwa 6]. Retrieved from https://www.city.kure.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/92909.pdf.

- Kure City Government. (2021). [Kure City Depopulated Area Sustainable Development Plan]. Retrieved November 5, 2023, from https://www.city.kure.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/66246.pdf.

- Lawler, E. J., & Thye, S. R. (1999). Bringing emotions into social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 217-244. [CrossRef]

- Leck, K. (2012). Playing Traditional Folk Music in Rural America. Music and Arts in Action, 4(1), 22-37.

- Long, P.T. , Perdue, R.R. and Allen, L. (1990), ‘‘Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism’’, Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 3-9.

- Lopes, A. C., Farinha, J., & Amado, M. (2017). Sustainability through art. Energy Procedia, 119, 752–766. [CrossRef]

- Mehl, M. D. (2013). Introduction: Western Music in Japan: A Success Story? Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 10(2), 211-222. [CrossRef]

- Molm, L. D. (1997). Coercive power in social exchange. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Molm, L. D. (2003). Theoretical comparisons of forms of exchange. Sociological Theory, 21(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D. , Weiler, B., & Croy, G. (2013). Visitors’ Perceptions of Tourism Impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 52, 392 - 406.

- Moyle, B.D. , Croy, W.G., & Weiler, B. (2010). Tourism interaction on islands: the community and visitor social exchange. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4, 96-107.

- Norris, F. H. , Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1-2), 127-150. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. , Gursoy, D., & Juwaheer, T.D. (2010). Island residents' identities and their support for tourism: an integration of two theories. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18, 675 - 693.

- Nunkoo, R. , & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism: An Identity Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 39, 243-268.

- Packer, J. , & Ballantyne, J. (2011). The impact of music festival attendance on young people’s psychological and social well-being. Psychology of Music, 39(2), 164–181. [CrossRef]

- Parkes, K. , and Jones, B.D. (2011) "Students’ motivations for considering a career in music performance”. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 29, 20-28.

- Pop, I. L. , Borza, A., Buiga, A., Ighian, D., & Toader, R. (2019). Achieving cultural sustainability in museums: A step toward sustainable development. Sustainability, 11(4), 970.

- Qu, M. (2020). Teshima — From Island Art to the Art Island: Art on/for a previously declining Japanese Inland Sea Island. International Journal of Research, 14.

- Qu, M. , Cheer, J.M., (2021). Community art festivals and sustainable rural revitalisation.

- Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29, (11–12), 1756–1775.

- Qu, M. , Zollet, S., & Chiya, A. (2024). Island Art Sustainability Education: A case study of Osakikamijima, Japan. Shima, 18(1), 68-88. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B. , & Wilks, L. (2017). Festival heterotopias: Spatial and temporal transformations in two small-scale settlements. Journal of Rural Studies, 53, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A. , Pinto, P., Silva, J.A., & Woosnam, K.M. (2017). Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tourism Management, 61, 523-537.

- Rossetti, G. , & Quinn, B. (2021). Understanding the cultural potential of rural festivals: A conceptual framework of cultural capital development. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. , & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. [CrossRef]

- Sintas, J. L. , Zerva, K., & García-Álvarez, E. (2012). Accessing recorded music: Interpreting a contemporary social exchange system. Acta Sociologica, 55(2), 179-194. [CrossRef]

- Soini, K. , & Dessein, J. (2016). Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability (Switzerland), 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Takarajima Kurahashi Town Development Council. (2019) [Kurahashi District Town Development Plan]. Retrieved November 6, 2023, from https://www.city.kure.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/37821.pdf.

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). United Nations. https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1.

- Wiggins, G. , & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).