Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Modification and Improvement in Polymeric Membranes

3. Global Market

4. Modules of the Membranes

5. Mechanisms of Membranes

| Companies | Type /polymer material | Solute | Rejection % | Pressure | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TriSep | UA60/ Polypiperazine amide, SB90/ Cellulose Acetate | MgSO4 | 70, 97 | 8 bar | [54,55] |

| GE | CK/ Cellulose Acetate, HL/ Polyamide, | Na2SO4 MgSO4 | 92 | 15 bar, 8 bar | [55] |

| Dow | NF, NF90, NF270/ Polyamide | MgSO4 | 99 | 9 bar | [55,56] |

| Veolia | DK, RL/ Polyamide | MgSO4 | 96, 98 | 7 bar | [57] |

| Synder | NFX, NFW/ Polyamide | MgSO4 | 97, 99 | 8 bar, 7 bar | [55,57] |

| Microdyn Nadir | NP010, NP030/ Polyethersulfone | Na2SO4 | 35-75 | 40 bar | [55,57] |

| Alfa | NF, NF99HF, RO90, RO99/ Polyester | MgSO4 | 99, 99, 90, 98 | 5 bar, 9 bar | [58] |

6. Polymeric Membranes Materials

6.1. Polyethersulfone (PES)

6.2. Polysulfone (PSf)

6.3. Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)

6.4. Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF)

6.5. Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)

6.6. Cellulose Acetate (CA)

6.7. Polyamide (PA)

7. Fabrication Techniques

7.1. Phase Inversion (PI)

7.2. Surface Modification Membranes

7.2.1. Physical Surface Modification

7.2.1.1. Dip Coating

7.2.1.2. Dip Coating

7.2.2. Chemical Surface Modification

7.2.2.1. Thin Film Composite (TFC)

7.2.2.2. Thin Film Nanocomposite (TFN)

8. Flux and Rejection

9. Membrane Fouling and Cleaning

10. Conclusion and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL2O3 | Nano-sized alumina |

| Ag | Silver |

| AMD | Acid mine drainage |

| Au | Gold |

| BaSO4 | Barium sulfate |

| BDSA | Benzidinedisulfonic acid |

| BHTTM | Bis(1-hydroxyl-1-trifluoromethyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-4,4′-methylenedianiline |

| CA | Cellulose acetate |

| CaSO4 | Calcium sulfate |

| CdSO4 | Cadmium sulfate |

| CFFO | Carboxyl functionalized ferroferric oxide |

| CFV | Cross flow velocity |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl chitosan |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| CuSO4 | Copper sulfate |

| DMAc | Dimethylacetamide |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| Fe2O3 | Ferric oxide |

| GE | General electric |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| HACC | Hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan |

| HNT | Halloysite nanotubes |

| HPEI | Hyperbranched polyethyleneimine |

| IP | interfacial polymerization |

| K2SO4 | Potassium sulfate |

| KOH/HNO3/H3PO4 | Potassium hydroxide+ Nitric+ Phosphoric acids |

| KDa | Kilodalton |

| LIPS | liquid-induced phase inversion |

| LMH | Permeate flux |

| MF | Microfiltration |

| MgSO4 | Magnesium sulfate |

| MMMs | Mixed matrix membranes |

| MOF | Metal-organic frameworks |

| MPD | Meta-phenylenediamine |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| NaSO4 | Sodium sulphate |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| NIPS | Non-solvent-induced phase inversion |

| NMP | N-methyl pyrrolidone |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| PFPT | Periodic feed pressure technique |

| PI | Polyimide |

| PIP | Piperazine |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PPEA | Poly (ethylene glycol) phenyl ether acrylate |

| PS | Phase separation |

| PSf | Polysulfone |

| PTMP | Periodic transmembrane pressure technique |

| PTP | Periodic transmembrane pressure |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| PWF | Pure water flux |

| RO | Reverse osmosis |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SPES | Sulfonated polyether sulfone |

| SPSU | Sulfonated polysulfone |

| SWCNTs | Single-walled carbon nanotubes |

| TEA | Triethylamine |

| TFC | Thin-film composite |

| TFN | Thin-film nanocomposite |

| TiO2 | Titanium dioxide |

| TIPS | Thermal-induced phase inversion |

| TMC | Trimesoyl chloride |

| TMP | Transmembrane pressure |

| UF | Ultrafiltration |

| VIPS | Vapor-induced phase inversion |

| WHO | World health organization |

| ZnO | Zinc oxide |

References

- Boretti, A., Rosa, L.: Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. npj Clean Water. 2, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.M.A., Kargari, A., Shirazi, M.J.A.: Direct contact membrane distillation for seawater desalination. Desalin. Water Treat. 49, 368–375 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Runtti, H., Tynjälä, P., Tuomikoski, S., Kangas, T., Hu, T., Rämö, J., Lassi, U.: Utilisation of barium-modified analcime in sulphate removal: Isotherms, file:///C:/Users/Jamal/Desktop/Reference/Jensen, 2017.pdfkinetics and thermodynamics studies. J. Water Process Eng. 16, 319–328 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Quist-Jensen, C.A., Macedonio, F., Horbez, D., Drioli, E.: Reclamation of sodium sulfate from industrial wastewater by using membrane distillation and membrane crystallization. Desalination. 401, 112–119 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Firdous, S., Jin, W., Shahid, N., Bhatti, Z.A., Iqbal, A., Abbasi, U., Mahmood, Q., Ali, A.: The performance of microbial fuel cells treating vegetable oil industrial wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 10, 143–151 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cao, W., Dang, Z., Zhou, X.Q., Yi, X.Y., Wu, P.X., Zhu, N.W., Lu, G.N.: Removal of sulphate from aqueous solution using modified rice straw: Preparation, characterization and adsorption performance. Carbohydr. Polym. 85, 571–577 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Badmus, S.O., Oyehan, T.A., Saleh, T.A.: Synthesis of a Novel Polymer-Assisted AlNiMn Nanomaterial for Efficient Removal of Sulfate Ions from Contaminated Water. J. Polym. Environ. 29, 2840–2854 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, M.: Advanced functional polymer membranes. Polymer (Guildf). 47, 2217–2262 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Fakhru’l-Razi, A., Pendashteh, A., Abdullah, L.C., Biak, D.R.A., Madaeni, S.S., Abidin, Z.Z.: Review of technologies for oil and gas produced water treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 170, 530–551 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Echakouri, M., Salama, A., Henni, A.: Experimental and Computational Fluid Dynamics Investigation of the Deterioration of the Rejection Capacity of the Membranes Used in the Filtration of Oily Water Systems. ACS ES T Water. 1, 728–744 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dickhout, J.M., Moreno, J., Biesheuvel, P.M., Boels, L., Lammertink, R.G.H., de Vos, W.M.: Produced water treatment by membranes: A review from a colloidal perspective. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 487, 523–534 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Seung- Yeop; Kim, Sung Ho; Kim, S.S.: Hybrid Organic / Inorganic Reverse Osmosis ( RO ) Membrane for Preparation and Characterization of TiO 2 Nanoparticle Self-Assembled Aromatic Polyamide Membrane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 2388–2394 (2001).

- Rahimpour, A., Jahanshahi, M., Mollahosseini, A., Rajaeian, B.: Structural and performance properties of UV-assisted TiO 2 deposited nano-composite PVDF/SPES membranes. Desalination. 285, 31–38 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Yu, T., Zhou, J., Liu, F., Xu, B.M., Pan, Y.: Recent Progress of Adsorptive Ultrafiltration Membranes in Water Treatment—A Mini Review. Membranes (Basel). 12, 1–10 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D., Borges, A., Simões, M.: Staphylococcus aureus toxins and their molecular activity in infectious diseases. Toxins (Basel). 10, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.S., Sabirova, T.M., Tretyakova, N.A., Alsalhy, Q.F., Figoli, A., Salih, I.K.: A mini-review of enhancing ultrafiltration membranes (Uf) for wastewater treatment: Performance and stability. ChemEngineering. 5, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Moslehyani, A., Mobaraki, M., Ismail, A.F., Matsuura, T., Hashemifard, S.A., Othman, M.H.D., Mayahi, A., Rezaei Dashtarzhandi, M., Soheilmoghaddam, M., Shamsaei, E.: Effect of HNTs modification in nanocomposite membrane enhancement for bacterial removal by cross-flow ultrafiltration system. React. Funct. Polym. 95, 80–87 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R.: t f c CRC handbook of chemistry and physics : a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. (2009).

- Elphick, J.R., Davies, M., Gilron, G., Canaria, E.C., Lo, B., Bailey, H.C.: An aquatic toxicological evaluation of sulfate: The case for considering hardness as a modifying factor in setting water quality guidelines. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 30, 247–253 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Curtis, P.J.: Effects of hydrogen ion and sulphate on the phosphorus cycle of a Precambrian Shield lake. Nature. 337, 156–158 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Hamingerova, M., Borunsky, L., Beckmann, M.: Membrane Technologies for Water and Wastewater Treatment on the European and Indian Market. Techview Membr. (2015).

- Roy, Y., Warsinger, D.M., Lienhard, J.H.: Effect of temperature on ion transport in nanofiltration membranes: Diffusion, convection and electromigration. Desalination. 420, 241–257 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bolong, N., Ismail, A.F., Salim, M.R., Matsuura, T.: A review of the effects of emerging contaminants in wastewater and options for their removal. Desalination. 239, 229–246 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Van Der Bruggen, B.: The use of nanoparticles in polymeric and ceramic membrane structures: Review of manufacturing procedures and performance improvement for water treatment. Environ. Pollut. 158, 2335–2349 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, J.H., Murthy, Z.V.P.: A comprehensive review on anti-fouling nanocomposite membranes for pressure driven membrane separation processes. Desalination. 379, 137–154 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ba-Abbad, M.M., Mahmud, N., Benamor, A., Mahmoudi, E., Takriff, M.S., Mohammad, A.W.: Improved properties and salt rejection of polysulfone membrane by incorporation of hydrophilic cobalt-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Emergent Mater. 7, 509–519 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Tang, B., Wu, P.: Optimizing polyamide thin film composite membrane covalently bonded with modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J. Memb. Sci. 428, 341–348 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Agboola, O., Mokrani, T., Sadiku, E.R., Kolesnikov, A., Olukunle, O.I., Maree, J.P.: Characterization of Two Nanofiltration Membranes for the Separation of Ions from Acid Mine Water. Mine Water Environ. 36, 401–408 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Juholin, P., Kääriäinen, M.L., Riihimäki, M., Sliz, R., Aguirre, J.L., Pirilä, M., Fabritius, T., Cameron, D., Keiski, R.L.: Comparison of ALD coated nanofiltration membranes to unmodified commercial membranes in mine wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 192, 69–77 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Al-Nahari, A., Li, S., Su, B.: Negatively charged nanofiltration membrane with high performance via the synergetic effect of benzidinedisulfonic acid and trimethylamine during interfacial polymerization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 291, 120947 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Song, X., Wang, T., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Gao, C.: Fabrication and characterization of polyethersulfone/carbon nanotubes (PES/CNTs) based mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) for nanofiltration application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 330, 118–125 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Qu, S., Dilenschneider, T., Phillip, W.A.: Preparation of Chemically-Tailored Copolymer Membranes with Tunable Ion Transport Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7, 19746–19754 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Javed Alam,1 Lawrence Arockiasamy Dass,1 Mostafa Ghasemi,2 Mansour Alhoshan1, 3: Synthesis and Optimization of PES-Fe3O4 Mixed Matrix Nanocomposite Membrane: Application Studies in Water Purification. Polym. Compos. 16, 101–113 (2013).

- Kong, Q., Xu, H., Liu, C., Yang, G., Ding, M., Yang, W., Lin, T., Chen, W., Gray, S., Xie, Z.: Fabrication of high performance TFN membrane containing NH2-SWCNTs: Via interfacial regulation. RSC Adv. 10, 25186–25199 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zoubeik, M., Ismail, M., Salama, A., Henni, A.: New Developments in Membrane Technologies Used in the Treatment of Produced Water: A Review. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 43, 2093–2118 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Rajindar Singh: Membrane Technology and Engineering for Water Purification Application, Systems Design and Operation. Butterworth-Heinemann (2014).

- Singh, R.: Membrane Technology and Engineering for Water Purification (2015).

- BCC Research: Membrane Technology for Liquid and Gas Separations. https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/membrane-and-separation-technology/membrane-technology-liquid-gas-separations.html.

- BCC Research: Global Market for Membrane Microfiltration. https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/membrane-and-separation-technology/membrane-microfiltration.html.

- BCC Reseach: Technologies for Nanofiltration Global Markets and Technologies for Nanofiltration, www.bccre search.com/market-research/nanotech nology/global- markets-and-technologie s-for-nanofibers.html.

- BCC Research: Ultrafiltration Membranes: Technologies and Global Markets. https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/membrane-and-separation-technology/ultrafiltration-membranes-techs-markets-report.html.

- https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/nanotechnology/nanofiltration.html.

- BCC Research: Water Filtration: Global Markets.

- Richard W. Baker: Membrane technologies and applications (2004).

- Zirehpour, A., Rahimpour, A.: Membranes for Wastewater Treatment (2016).

- Singh, R.: Hybrid Membrane Systems for Water Purification: Technology, Systems Design and Operations. (2006).

- Cheryan, M.: Ultrafiltration and microfiltration handbook. CRC Press (1998).

- Warsinger, D.M., Chakraborty, S., Tow, E.W., Plumlee, M.H., Bellona, C., Loutatidou, S., Karimi, L., Mikelonis, A.M., Achilli, A., Ghassemi, A., Padhye, L.P., Snyder, S.A., Curcio, S., Vecitis, C.D., Arafat, H.A., Lienhard, J.H.: A review of polymeric membranes and processes for potable water reuse. Prog. Polym. Sci. 81, 209–237 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fatah, M.A.: Nanofiltration systems and applications in wastewater treatment: Review article. Ain Shams Eng. J. 9, 3077–3092 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Abdelrasoul, A.: Advances in Membrane Technologies (2020).

- Bellona, C., Drewes, J.E., Xu, P., Amy, G.: Factors affecting the rejection of organic solutes during NF/RO treatment - A literature review. Water Res. 38, 2795–2809 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Bellona, C., Drewes, J.E.: The role of membrane surface charge and solute physico-chemical properties in the rejection of organic acids by NF membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 249, 227–234 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Van Der Bruggen, B., Schaep, J., Wilms, D., Vandecasteele, C.: Influence of molecular size, polarity and charge on the retention of organic molecules by nanofiltration. J. Memb. Sci. 156, 29–41 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Bulletin, T.: TRISEP ® & NADIR ® Membrane Products. 3–5 (2021.).

- Sterlitech Corporation: Crossflow Filtration Handbook. 21 (2018).

- The Dow Chemical Company: FILMTEC Membranes. Basics of RO and NF: Element Performance. 2–3 (2008).

- Membranes, F.S.: Flat sheet membranes ultrafiltration membranes. 10, (2002.).

- Alfa Laval Corporate AB: Alfa Laval NF and RO flat sheet membranes (2022).

- Paugam, L., Diawara, C.K., Schlumpf, J.P., Jaouen, P., Quéméneur, F.: Transfer of monovalent anions and nitrates especially through nanofiltration membranes in brackish water conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 40, 237–242 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J., Reig, M., Gibert, O., Valderrama, C., Cortina, J.L.: Evaluation of NF membranes as treatment technology of acid mine drainage: metals and sulfate removal. Desalination. 440, 122–134 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Gozálvez-Zafrilla, J.M., Sanz-Escribano, D., Lora-García, J., León Hidalgo, M.C.: Nanofiltration of secondary effluent for wastewater reuse in the textile industry. Desalination. 222, 272–279 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S. V., Marathe, K. V., Rathod, V.K.: A pilot scale concurrent removal of fluoride, arsenic, sulfate and nitrate by using nanofiltration: Competing ion interaction and modelling approach. J. Water Process Eng. 13, 153–167 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hilal, N., Al-Zoubi, H., Darwish, N.A., Mohammad, A.W.: Performance of nanofiltration membranes in the treatment of synthetic and real seawater. Sep. Sci. Technol. 42, 493–515 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Krieg, H.M., Modise, S.J., Keizer, K., Neomagus, H.W.J.P.: Salt rejection in nanofiltration for single and binary salt mixtures in view of sulphate removal. Desalination. 171, 205–215 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Bowen, W.R., Jones, M.G., Welfoot, J.S., Yousef, H.N.S.: Predicting salt rejections at nanofiltration membranes using artificial neural networks (2000).

- Ağtas, M., Ormancı-Acar, T., Keskin, B., Türken, T., Kouncu, I.: Nanofiltration membranes for salt and dye filtration: effect of membrane properties on performances. Water Sci. Technol. (2021).

- Ng, L. Y., Leo C. P, Mohammad A. W.: Optimizing the Incorporation of Silica Nanoparticles in Polysulfone/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Membranes with Response Surface Methodology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 116, 2658–2667 (2011).

- Lee, H.S., Im, S.J., Kim, J.H., Kim, H.J., Kim, J.P., Min, B.R.: Polyamide thin-film nanofiltration membranes containing TiO2 nanoparticles. Desalination. 219, 48–56 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Seung, Y. L., Hee,J. K., Patel, R., Im, S.J., Kim, J.H. and Min, B.R.: Silver nanoparticles immobilized on thin film composite polyamide membrane: characterization, nanofiltration, antifouling properties. Polym. Adv. Technol. 229–236 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Murthy, Z.V.P., Gaikwad, M.S.: Preparation of chitosan-multiwalled carbon nanotubes blended membranes: Characterization and performance in the separation of sodium and magnesium ions. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 17, 245–262 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, B.M., Isloor, A.M., Ismail, A.F.: Enhanced hydrophilicity and salt rejection study of graphene oxide-polysulfone mixed matrix membrane. Desalination. 313, 199–207 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S., Hwang, G., Gamal El-Din, M., Liu, Y.: Development of nanosilver and multi-walled carbon nanotubes thin-film nanocomposite membrane for enhanced water treatment. J. Memb. Sci. 394–395, 37–48 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, L.B., Murthy, Z.V.P.: Preparation, Characterization, and Performance of Sulfated Chitosan/Polyacrylonitrile Composite Nanofiltration Membranes. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 34, 389–399 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., Chen, G., Sun, M., Gao, C.: Preparation and characterization of quaterinized chitosan/poly(acrylonitrile) composite nanofiltration membrane from anhydride mixture cross-linking. Sep. Purif. Technol. 58, 393–399 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, D., Xie, Z., Peng, W., Song, Y., Hu, R., Chen, D., Kang, J., Xu, R., Cao, Y., Xiang, M.: Polyamide membrane with nanoscale stripes and internal voids for high-performance nanofiltration. J. Memb. Sci. 671, 121406 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ekambaram, K., Doraisamy, M.: Surface modification of PVDF nanofiltration membrane using Carboxymethylchitosan-Zinc oxide bionanocomposite for the removal of inorganic salts and humic acid. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 525, 49–63 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Zhang, S., Yang, F., Yan, C., Jian, X.: Preparation and performance of novel thermal stable composite nanofiltration membrane. Front. Chem. Eng. China. 2, 402–406 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ormanci-Acar, T., Celebi, F., Keskin, B., Mutlu-Salmanlı, O., Agtas, M., Turken, T., Tufani, A., Imer, D.Y., Ince, G.O., Demir, T.U., Menceloglu, Y.Z., Unal, S., Koyuncu, I.: Fabrication and characterization of temperature and pH resistant thin film nanocomposite membranes embedded with halloysite nanotubes for dye rejection. Desalination. 429, 20–32 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hu, D., Xu, Z.L., Wei, Y.M.: A high performance silica-fluoropolyamide nanofiltration membrane prepared by interfacial polymerization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 110, 31–38 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, A., Madaeni, S.S., Mehdipour-Ataei, S.: Synthesis of a novel poly(amide-imide) (PAI) and preparation and characterization of PAI blended polyethersulfone (PES) membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 311, 349–359 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Yung, L., Ma, H., Wang, X., Yoon, K., Wang, R., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: Fabrication of thin-film nanofibrous composite membranes by interfacial polymerization using ionic liquids as additives. J. Memb. Sci. 365, 52–58 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Peng, J., Su, Y., Zheng, L., Wang, L., Jiang, Z.: Separation of oil/water emulsion using Pluronic F127 modified polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 66, 591–597 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Mansourizadeh, A., Javadi Azad, A.: Preparation of blend polyethersulfone/cellulose acetate/polyethylene glycol asymmetric membranes for oil-water separation. J. Polym. Res. 21, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Salahi, A., Mohammadi, T., Mosayebi Behbahani, R., Hemmati, M.: Asymmetric polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes for oily wastewater treatment: Synthesis, characterization, ANFIS modeling, and performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 3, 170–178 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, J.F., Xu, Z.L., Yang, H., Yu, L.Y., Liu, M.: Effect of TiO 2 nanoparticles on the surface morphology and performance of microporous PES membrane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 255, 4725–4732 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Liu, J., Liu, Y., Xu, Y., Li, R., Hong, H., Shen, L., Lin, H., Liao, B.Q.: Enhanced permeability and antifouling performance of polyether sulfone (PES) membrane via elevating magnetic Ni@MXene nanoparticles to upper layer in phase inversion process. J. Memb. Sci. 623, 119080 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Guillen, G.R., Pan, Y., Li, M., Hoek, E.M.V.: Preparation and characterization of membranes formed by nonsolvent induced phase separation: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 3798–3817 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, I., Aroujalian, A., Raisi, A., Dabir, B., Fathizadeh, M.: Surface modification of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes by corona air plasma for separation of oil/water emulsions. J. Memb. Sci. 430, 24–36 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Machodi, M.J., Daramola, M.O.: Synthesis of pes and pes/chitosan membranes for synthetic acid mine drainage treatment. Water SA. 46, 114–122 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lipp, P., Lee, C.H., Fane, A.G., Fell, C.J.D.: A fundamental study of the ultrafiltration of oil-water emulsions. J. Memb. Sci. 36, 161–177 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, B., Ghoshal, A.K., Purkait, M.K.: Ultrafiltration of stable oil-in-water emulsion by polysulfone membrane. J. Memb. Sci. 325, 427–437 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Amin, I.N.H.M., Mohammad, A.W., Markom, M., Peng, L.C., Hilal, N.: Flux decline study during ultrafiltration of glycerin-rich fatty acid solutions. J. Memb. Sci. 351, 75–86 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S., Ibrar, I., Samal, A.K., Altaee, A., Déon, S., Zhou, J., Ghaffour, N.: Preparation of fouling resistant and highly perm-selective novel PSf/GO-vanillin nanofiltration membrane for efficient water purification. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z., Chen, S., Peng, X., Zhang, L., Gao, C.: Polyamide membranes with nanoscale Turing structures for water purification. Water Purif. 521, 518–521 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.S., Lau, W.J., Goh, P.S., Ismail, A.F., Yusof, N., Tan, Y.H.: Graphene oxide incorporated thin film nanocomposite nanofiltration membrane for enhanced salt removal performance. Desalination. 387, 14–24 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Moradi, G., Zinadini, S., Rajabi, L., Dadari, S.: Fabrication of high flux and antifouling mixed matrix fumarate-alumoxane/PAN membranes via electrospinning for application in membrane bioreactors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 427, 830–842 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K., Kim, K., Wang, X., Fang, D., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: High flux ultrafiltration membranes based on electrospun nanofibrous PAN scaffolds and chitosan coating. Polymer (Guildf). 47, 2434–2441 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Carraher Jr., C. E.: Carraher’s Polymer Chemistry. Taylor & Francis Group (2018).

- Musale, D.A., Kumar, A., Pleizier, G.: Formation and characterization of poly(acrylonitrile)/Chitosan composite ultrafiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 154, 163–173 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Asano, T., Burton, F. Water Reuse Issues: Technologies and Applications (Metcalf&Eddy/AECOM) (2007).

- Makaremi, M., Lim, C.X., Pasbakhsh, P., Lee, S.M., Goh, K.L., Chang, H., Chan, E.S.: Electrospun functionalized polyacrylonitrile-chitosan Bi-layer membranes for water filtration applications. RSC Adv. 6, 53882–53893 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: High flux ultrafiltration nanofibrous membranes based on polyacrylonitrile electrospun scaffolds and crosslinked polyvinyl alcohol coating. J. Memb. Sci. 338, 145–152 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Reyhani, A., Sepehrinia, K., Seyed Shahabadi, S.M., Rekabdar, F., Gheshlaghi, A.: Optimization of operating conditions in ultrafiltration process for produced water treatment via Taguchi methodology. Desalin. Water Treat. 54, 2669–2680 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Xu, Z., Liu, C., Zhao, Y., Xia, Q., Fang, M., Min, X., Huang, Z., Liu, Y., Wu, X.: Polydopamine nanocluster embedded nanofibrous membrane via blow spinning for separation of oil/water emulsions. Molecules. 26, 1–11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M., Wang, Z., Mahajan, D., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: High flux ethanol dehydration using nanofibrous membranes containing graphene oxide barrier layers. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 12998–13003 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, H.R., Hosseini, S.S.: Experimental and statistical investigation on fabrication and performance evaluation of structurally tailored PAN nanofiltration membranes for produced water treatment. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 147, 107766 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.E., Zhenova, A., Roberts, S., Petchey, T., Zhu, P., Dancer, C.E.J., McElroy, C.R., Kendrick, E., Goodship, V.: On the solubility and stability of polyvinylidene fluoride. Polymers (Basel). 13, 1–31 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.L., Wan, C.C., Wang, Y.Y.: Microporous PVdF-HFP based gel polymer electrolytes reinforced by PEGDMA network. Electrochem. commun. 6, 531–535 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y., Liu, R.J., Hsu, C.H., Kuo, P.L.: High thermal and electrochemical stability of PVDF-graft-PAN copolymer hybrid PEO membrane for safety reinforced lithium-ion battery. RSC Adv. 6, 18082–18088 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.R., Choi, S.W., Jo, S.M., Lee, W.S., Kim, B.C.: Electrospun PVdF-based fibrous polymer electrolytes for lithium ion polymer batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 50, 69–75 (2004). [CrossRef]

- ElGharbi, H., Henni, A., Salama, A., Zoubeik, M., Kallel, M.: Toward an Understanding of the Role of Fabrication Conditions During Polymeric Membranes Modification: A Review of the Effect of Titanium, Aluminum, and Silica Nanoparticles on Performance. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 8253–8285 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Hashim, N.A., Liu, Y., Abed, M.R.M., Li, K.: Progress in the production and modification of PVDF membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 375, 1–27 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Li, Y.S., Xiang, C.B.: Preparation of poly(vinylidene fluoride)(pvdf) ultrafiltration membrane modified by nano-sized alumina (Al2O3) and its antifouling research. Polymer (Guildf). 46, 7701–7706 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wu, L., Zhang, C., Chen, W., Luo, S.: Surface hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by trace amounts of tannin and polyethyleneimine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 457, 695–704 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Zhang, Y., Sadam, H., Ma, J., Bai, Y., Shen, X., Kim, J.K., Shao, L.: Novel mussel-inspired zwitterionic hydrophilic polymer to boost membrane water-treatment performance. J. Memb. Sci. 582, 1–8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sukitpaneenit, P., Chung, T.S.: Molecular elucidation of morphology and mechanical properties of PVDF hollow fiber membranes from aspects of phase inversion, crystallization, and rheology. Hollow Fiber Membr. Fabr. Appl. 333–360 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.H., Qian, Y.L., Zhu, B.K., Xu, Y.Y.: Modification of porous poly(vinylidene fluoride) membrane using amphiphilic polymers with different structures in phase inversion process. J. Memb. Sci. 310, 567–576 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Singh, A.K., Singh, J.K.: Ferrous sulfide and carboxyl-functionalized ferroferric oxide incorporated PVDF-based nanocomposite membranes for simultaneous removal of highly toxic heavy-metal ions from industrial ground water. J. Memb. Sci. 593, 117422 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sapalidis, A., Sideratou, Z., Panagiotaki, K.N., Sakellis, E., Kouvelos, E.P., Papageorgiou, S., Katsaros, F.: Fabrication of antibacterial poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite films containing dendritic polymer functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Front. Mater. 5, 1–10 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Fang, D., Yoon, K., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: High performance ultrafiltration composite membranes based on poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel coating on crosslinked nanofibrous poly(vinyl alcohol) scaffold. J. Memb. Sci. 278, 261–268 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Sapalidis, A.A.: Porous Polyvinyl alcohol membranes: Preparation methSapalidis, A. A. (2020). Porous Polyvinyl alcohol membranes: Preparation methods and applications. Symmetry, 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.R., Tak, T.M., Kwon, Y.N.: Preparation and applications of poly vinyl alcohol (PVA) modified cellulose acetate (CA) membranes for forward osmosis (FO) processes. Desalin. Water Treat. 53, 1–7 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstein, E., Liang, L.: Poly(acry1ic acid)-Poly(viny1 alcohol) Semi- and Interpenetrating Polymer Network Pervaporation Membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 62 (7), 973–987 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, R.D., Immelman, E., Bezuidenhout, D., Jacobs, E.P., Van Reenen, A.J.: Polyvinyl alcohol and modified polyvinyl alcohol reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination. 90, 15–29 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Immelman, E., Sanderson, R. D., Jacobs, E.P., van Reenen, A.J. : Poly( vinyl alcohol) Gel Sublayers for Reverse Osmosis Membranes. I. lnsolubilization by Acid-Catalyzed Dehydration. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 50, 1013–1034 (1993).

- Gao, Z., Yue, Y., Li, W.: Application of Zeolite-filled Pervaporation Membrane. Zeolites. 16, 70–74 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J., Park, S.H., So, W.W., Moon, S.J.: Pervaporation separation of aqueous organic mixtures through sulfated zirconia-poly(vinyl alcohol) membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 79, 1450–1455 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Guo, M., Pan, G., Yan, H., Xu, J., Shi, Y., Shi, H., Liu, Y.: Preparation and properties of novel pH-stable TFC membrane based on organic-inorganic hybrid composite materials for nanofiltration. J. Memb. Sci. 476, 500–507 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Bolto, B., Zhang, J., Wu, X., Xie, Z.: A review on current development of membranes for oil removal from wastewaters. Membranes (Basel). 10, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ma, H., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: Thin-film nanofibrous composite membranes containing cellulose or chitin barrier layers fabricated by ionic liquids. Polymer (Guildf). 52, 2594–2599 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Ma, H., Chu, B., Hsiao, B.S.: Fabrication of cellulose nanofiber-based ultrafiltration membranes by spray coating approach. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134, 1–6 (2017).

- Ma, H., Burger, C., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: Fabrication and characterization of cellulose nanofiber based thin-film nanofibrous composite membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 454, 272–282 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Lu, A., Zhang, L.: Recent advances in regenerated cellulose materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 53, 169–206 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Ma, H., Hsiao, B.S., Chu, B.: Nanofibrous ultrafiltration membranes containing cross-linked poly(ethylene glycol) and cellulose nanofiber composite barrier layer. Polymer (Guildf). 55, 366–372 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S., Celebioglu, A., Uyar, T.: Surface modification of electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers via RAFT polymerization for DNA adsorption. Carbohydr. Polym. 113, 200–207 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M., Mohan, D.R., Rangarajan, R.: Studies on cellulose acetate-polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes: II. Effect of additive concentration. J. Memb. Sci. 268, 208–219 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Ounifi, I., Ursino, C., Santoro, S., Chekir, J., Hafiane, A., Figoli, A., Ferjani, E.: Cellulose acetate nanofiltration membranes for cadmium remediation. J. Membr. Sci. Res. 6, 226–234 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B., Zhao, S., Hu, P., Cui, J., Niu, Q.J.: Asymmetric polyamide nanofilms with highly ordered nanovoids for water purification. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., Fei, Z., Hou, Y.: High-Performance Polyamide Reverse Osmosis Membrane Containing Flexible Aliphatic Ring for Water Purification. Polymers (Basel). 15, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Baig, U., Waheed, A., Salih, H.A., Matin, A., Alshami, A., Aljundi, I.H.: Facile modification of nf membrane by multi-layer deposition of polyelectrolytes for enhanced fouling resistance. Polymers (Basel). 13, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, A., Dilek, F.B., Yılmaz, L., Kitis, M., Yetis, U.: Sulfate removal from drinking water by commercially available nanofiltration membranes: A parametric study. Desalin. Water Treat. 205, 296–307 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Loeb, S., Sourirajan, S.: Sea Water Demineralization by Means of an Osmotic Membrane. Environ. Sci. Chem. 117–132 (1963). [CrossRef]

- Hołda, A.K., Vankelecom, I.F.J.: Understanding and guiding the phase inversion process for synthesis of solvent resistant nanofiltration membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132, 1–17 (2015).

- Xia, L., Zhang, Q., Zhuang, X., Zhang, S., Duan, C., Wang, X., Cheng, B.: Hot-pressed wet-laid polyethylene terephthalate nonwoven as support for separation membranes. Polymers (Basel). 11, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zsigmondy, R., Bachmann, W.: Über neue Filter. Zeitschrift für Anorg. und Allg. Chemie. 103, 119–128 (1918). [CrossRef]

- Elford, W.J.: Principles governing the preparation of membranes having graded porosities. The properties of “gradocol” membranes as ultrafilters. Trans. Faraday Soc. 33, 1094–1104 (1937). [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N., Venault, A., Mikkola, J.P., Bouyer, D., Drioli, E., Tavajohi Hassan Kiadeh, N.: Investigating the potential of membranes formed by the vapor induced phase separation process. J. Memb. Sci. 597, 117601 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J., Jung, B., Kang, Y.S., Lee, H.: Phase separation of polymer casting solution by nonsolvent vapor. J. Memb. Sci. 245, 103–112 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Kerr-Phillips, T., Schon, B., Barker, D.: Polymeric Materials and Microfabrication Techniques for Liquid Filtration Membranes, (2022).

- Zare, S., Kargari, A.: Membrane properties in membrane distillation. Emerg. Technol. Sustain. Desalin. Handb. 107–156 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Geleta, T.A., Maggay, I.V., Chang, Y., Venault, A.: Recent Advances on the Fabrication of Antifouling Phase-Inversion Membranes by Physical Blending Modification Method. Membranes (Basel). 13, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Alkandari, S.H., Castro-Dominguez, B.: Advanced and sustainable manufacturing methods of polymer-based membranes for gas separation: a review. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 3, 1–26 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K., Hoek, E.M.V.: Impacts of support membrane structure and chemistry on polyamide-polysulfone interfacial composite membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 336, 140–148 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Flynn, D. j.: The Nalco Water Handbook (2009).

- Giwa, A., Dufour, V., Al Marzooqi, F., Al Kaabi, M., Hasan, S.W.: Brine management methods: Recent innovations and current status. Desalination. 407, 1–23 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Sagle, A., Freeman, B.: Fundamentals of membranes for water treatment. Futur. Desalin. Texas. 1–17 (2004).

- Lau, W.J., Ismail, A.F., Misdan, N., Kassim, M.A.: A recent progress in thin film composite membrane: A review. Desalination. 287, 190–199 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Wang, H.: Recent developments in reverse osmosis desalination membranes. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 4551–4566 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Hermans, S., Bernstein, R., Volodin, A., Vankelecom, I.F.J.: Study of synthesis parameters and active layer morphology of interfacially polymerized polyamide-polysulfone membranes. React. Funct. Polym. 86, 199–208 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.H., Hoek, E.M.V., Yan, Y., Subramani, A., Huang, X., Hurwitz, G., Ghosh, A.K., Jawor, A.: Interfacial polymerization of thin film nanocomposites: A new concept for reverse osmosis membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 294, 1–7 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J.M.M., Boom, J.P., Mulder, M.H.V., Strathmann, H.: Retention measurements of nanofiltration membranes with electrolyte solutions. J. Memb. Sci. 145, 199–209 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, D., Lau, W.J., Rahbari-Sisakht, M., Ilbeygi, H., Rana, D., Matsuura, T., Ismail, A.F.: Synthesis, modification and optimization of titanate nanotubes-polyamide thin film nanocomposite (TFN) membrane for forward osmosis (FO) application. Chem. Eng. J. 281, 243–251 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Baroña, G.N.B., Lim, J., Choi, M., Jung, B.: Interfacial polymerization of polyamide-aluminosilicate SWNT nanocomposite membranes for reverse osmosis. Desalination. 325, 138–147 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M., Emadzadeh, D., Lau, W.J., Lai, S.O., Matsuura, T., Ismail, A.F.: Synthesis and characterization of novel thin film nanocomposite (TFN) membranes embedded with halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) for water desalination. Desalination. 358, 33–41 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sasson, M., Lu, X., Bar-Zeev, E., Zodrow, K.R., Nejati, S., Qi, G., Giannelis, E.P., Elimelech, M.: In situ formation of silver nanoparticles on thin-film composite reverse osmosis membranes for biofouling mitigation. Water Res. 62, 260–270 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Hu, D., Xu, Z.L., Chen, C.: Polypiperazine-amide nanofiltration membrane containing silica nanoparticles prepared by interfacial polymerization. Desalination. 301, 75–81 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Seung Yun Lee, Hee Jin Kim, Rajkumar Patel, S.J.I., Min*, J.H.K. and B.R.: Silver nanoparticles immobilized on thin film composite polyamide membrane: characterization, nanofiltration, antifouling properties. Polym. Adv. Technol. 229–236 (2007).

- Lech, M., Gala, O., Helińska, K., Kołodzińska, K., Konczak, H., Mroczyński, Ł., Siarka, E.: Membrane Separation in the Nickel-Contaminated Wastewater Treatment. Waste. 1, 482–496 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Rameetse, M.S., Aberefa, O., Daramola, M.O.: Effect of loading and functionalization of carbon nanotube on the performance of blended polysulfone/polyethersulfone membrane during treatment of wastewater containing phenol and benzene. Membranes (Basel). 10, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Di Crescenzo, A., Ettorre, V., Fontana, A.: Non-covalent and reversible functionalization of carbon nanotubes. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 5, 1675–1690 (2014). [CrossRef]

- 2017; 53.

- Giorno, L.: Encyclopedia of Membranes. Encycl. Membr. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Schaep, J., Vandecasteele, C.: Evaluating the charge of nanofiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 188, 129–136 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Childress, A.E., Elimelech, M.: Effect of solution chemistry on the surface charge of polymeric reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 86, 24–31 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Braghetta, B.A., Digiano, F. a, Member, W.P.B.: Nanofiltration of Natural Organic Matter: pH and Ionic Strength Effects. J. Environ. Eng. 123, 628–641 (1994).

- Nghiem, L.D., Schäfer, A.I., Elimelech, M.: Pharmaceutical retention mechanisms by nanofiltration membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 7698–7705 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Hong, S., Elimelech, M.: Chemical and physical aspects of natural organic matter (NOM) fouling of nanofiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 132, 159–181 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Kiso, Y., Sugiura, Y., Kitao, T., Nishimura, K.: Effects of hydrophobicity and molecular size on rejection of aromatic pesticides with nanofiltration membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 192, 1–10 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S., Lau, W.J., Othman, M.H.D., Ismail, A.F.: Membrane fouling in desalination and its mitigation strategies. Desalination. 425, 130–155 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vrouwenvelder, J.S., Kappelhof, J.W.N.M., Heijman, S.G.J., Schippers, J.C., van der Kooij, D.: Tools for fouling diagnosis of NF and RO membranes and assessment of the fouling potential of feed water. Desalination. 157, 361–365 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Vrouwenvelder, H.S., van Paassen, J.A.M., Folmer, H.C., Hofman, J.A.M.H., Nederlof, M.M., van der Kooij, D.: Biofouling of membranes for drinking water production. Water Supply. 17, 225–234 (1999).

- Al-Amoudi, A.S., Farooque, A.M.: Performance restoration and autopsy of NF membranes used in seawater pretreatment. Desalination. 178, 261–271 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Tran-Ha, M.H., Wiley, D.E.: The relationship between membrane cleaning efficiency and water quality. J. Memb. Sci. 145, 99–110 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Zoubeik, M., Henni, A.: Ultrafiltration of oil-in-water emulsion using a 0.04-µm silicon carbide membrane: Taguchi experimental design approach. Desalin. Water Treat. 62, 108–119 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zoubeik, M., Salama, A., Henni, A.: A novel antifouling technique for the crossflow filtration using porous membranes: Experimental and CFD investigations of the periodic feed pressure technique. Water Res. 146, 159–176 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Echakouri, M., Salama, A., Henni, A.: A comparative study between three of the physical antifouling techniques for oily wastewater filtration using ceramic membranes: Namely; the novel periodic transmembrane pressure technique, pulsatile flow, and backflushing. J. Water Process Eng. 54, 103921 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wan Azelee, I., Goh, P.S., Lau, W.J., Ismail, A.F., Rezaei-DashtArzhandi, M., Wong, K.C., Subramaniam, M.N.: Enhanced desalination of polyamide thin film nanocomposite incorporated with acid treated multiwalled carbon nanotube-titania nanotube hybrid. Desalination. 409, 163–170 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y., Naddeo, V., Banat, F., Hasan, S.W.: Preparation of novel polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-Tin(IV) oxide (SnO2) ion exchange mixed matrix membranes for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 250, 117250 (2020). [CrossRef]

| Global market, topic | Objective | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Global markets for microfiltration membranes (MF) | The microfiltration membranes market was worth $3.9 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow to $6 billion by 2027, with a compound annual growth rate of 8.8%. | [39] |

| Global markets and technologies for reverse osmosis (RO) systems for water treatment | The market for essential parts of RO water treatment systems is expected to grow from $11.7 billion in 2020 to $19.1 billion by 2025, with an annual growth rate of 10.3%. | [40] |

| Global markets and technologies for Ultrafiltration membranes (UF) | The ultrafiltration membranes market is projected to increase from $4.4 billion in 2021 to $5.9 billion by 2026, at an annual growth rate of 5.9% from 2021 to 2026. | [41] |

| Global markets and technologies for nanofiltration (NF) | The NF membranes market is set to grow significantly, increasing from $518 million in 2019 to $1.2 billion by 2024, with a robust annual growth rate of 18.2%. | [42] |

| Global markets and water filtration: | The global water filtration systems market was worth $6.0 billion in 2021. It is expected to increase to $12.1 billion by 2027, with an annual growth rate of 12.9% from 2022 to 2027. | [43] |

| Property | Spiral/wound | Flat/plate | Tubular | Hollow/fiber |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packing Density (m2/m3) | 500-1000 | 200-500 | 70-100 | 500-5000 |

| Manufacturing cost | Moderate | High | High | low |

| Ease of cleaning | Poor to good | Good | Excellent | Poor |

| Energy demanding | Moderate | Low to moderate | High | Low |

| Fouling potential | High | Moderate | low | Very high |

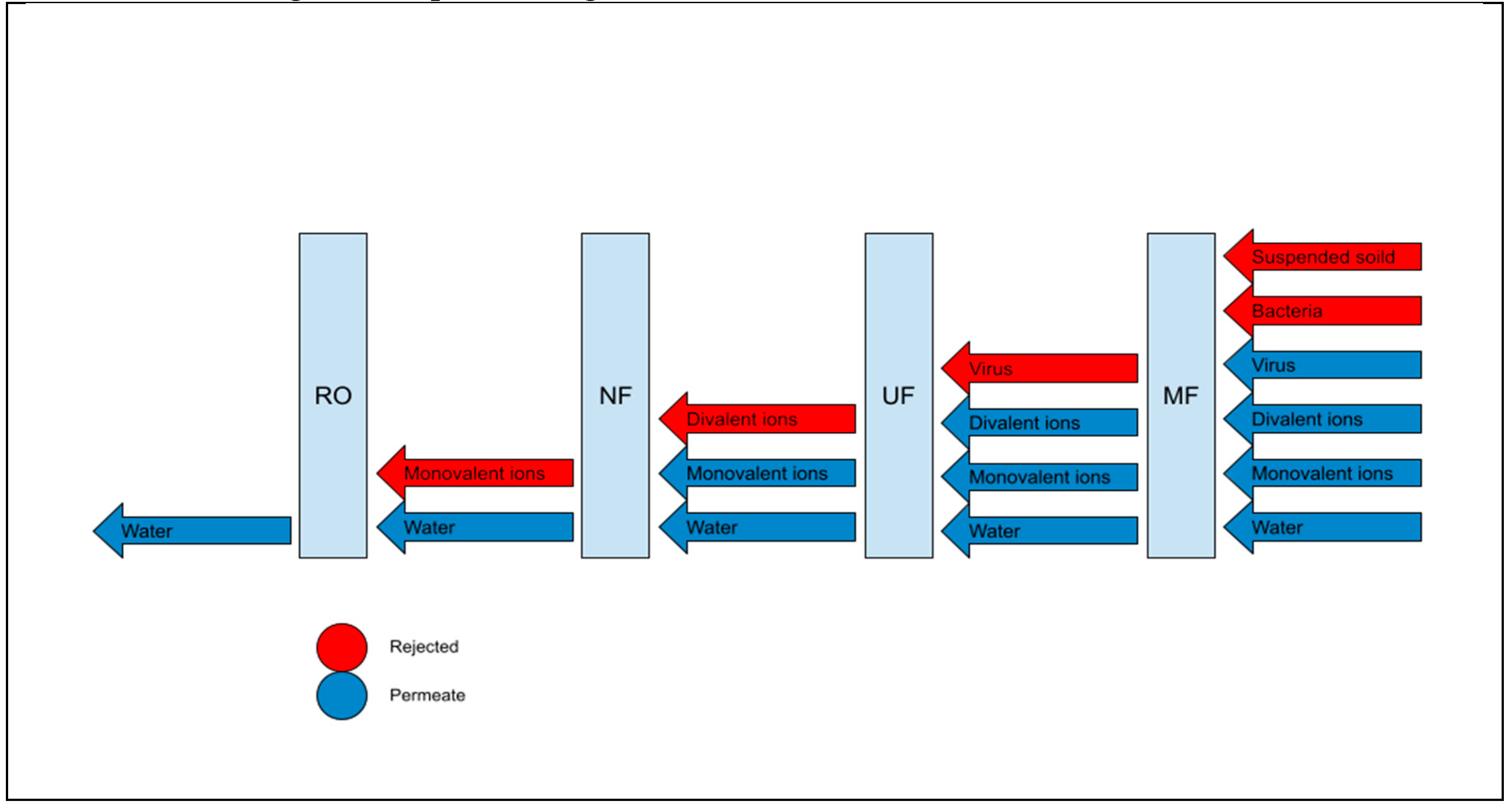

| Membrane process |

MF | UF | NF | RO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pore size | 50-10000 nm | 5-100 nm | 1-10 nm | <2 nm |

| Membrane structure | Asymmetric or symmetric, porous | Asymmetric, Microporous | Asymmetric, thin film composite, tight porous | Asymmetric, thin film composite, semi-porous |

| MWCO | >200000 Da | 1000-200000 Da | 200-1000 Da | >100 Da |

| Retained | Bacteria, colloids, organics, suspended solids | Virus, proteins, oils, lactose, vitamins, organic | Divalent: anions and cations, organics | Monovalent ions, all contaminants |

| Thickness surface film | 10-150 µm | 150-250 µm | 150 µm | 150 µm |

| Average permeability | 500 (L/m2 h bar) | 150 (L/m2 h bar) | 10-20 (L/m2 h bar) | 5-10 (L/m2h bar) |

| Filtration mechanism | Molecular sieve | Molecular sieve | Solution diffusion | Solution diffusion |

| Membrane materials | PES, PSf, PA, PP | PVDF, PES, PP, PAN | CA, PA, PI, SPSU | CA, PA, PI, SPSU |

| Pressure | 0.1-3 bar | 2-4 bar | 5-40 bar | 7-100 bar |

| Membranes | Materials | Operation conditions | Solution type | Rejection% | Flux LMH |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPS44 NF70 DESAL | Org.Selro PA PA | 8 bar, 20 oC, 5-200 mg/l, pH 6 | Na2SO4 & Nitrates | 85–66 94–91 60–45 | 8 71 50.5 | [59] |

| Hydr70p TNF270 |

SPES PA |

8.3-20 bar, 25 oC, flow 14.3 l/min., pH 2-2.8 | Na2SO4 | 89 75 |

2.8-3.6 2.9-4.1 |

[60] |

| NF90 NF200 NF270 | PA | 6-22 bar, 25 oC, 340 l/hr, 1780 mg/l, | Secondary effluent | 75 60 65 |

8 22 35 |

[61] |

| NF90 NF270 | PA | 5-20 bar, 28˚C, pH 7 | Na2SO4 |

96 88 |

- | [62] |

| NF90 NF270 |

PA | 4-9 bar, 25˚C | Na2SO4 | 66.586.5 | 2.2 41.5 |

[63] |

| TFC-SR NF70 NF90 |

PA | 5-20 bar, 25 oC | Na2SO4 |

96 99 93 |

12.3 2.6 3.6 |

[64] |

| NF Desal DK | PA | 1-25 bar, 25 oC, flowrate 1800 l/hr |

MgSO4 Na2SO4 |

98 99 |

- | [65] |

| Toray T610, NF 270 NF Desal 5 L |

PA | 6-15 bar, 2000 mg/l | MgSO4 | 94 91 94 |

205 143 80 |

[66] |

| Membrane materials | Operation condition | Solution type | PWF or Flux (LMH) | Rejection% | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSf+PVA+silica | 10 bar, 23 oC | NaSO4 | 61.9 | 97.5 | [67] |

| PES+PA + TiO | 6 bar, 25 oC | MgSO4 | 9.1 | 95 | [68] |

| PES+PA+Ag | 14 bar, 25 oC | Na2SO4 | 92 | 97 | [69] |

| PES + chitosan + multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) | 2-10 bar, flow rate 16 l/min pH 6.4, | NaSO4 MgSO4 NaCl |

15.50 | 89.05 66.74 50.89 |

[70] |

| PSf+GO | 4 bar, pH 2-12 | Na2SO4 | - | 72% | [71] |

| PSf,+MWCNT+Ag | 14 bar, 23 oC, pH 7 | Na2SO4 NaCl |

- | 95.6 88.1 |

[72] |

| PAN+ Chitosan | 2–12 bar, 30 oC | Na2SO4 ZnSO4 CuSO4 |

18.35 | 97.2 ~ 92 ~ 89 |

[73] |

| PAN+ HACC | 5–14 bar, 25 oC | Na2SO4 MgSO4 K2SO4 |

13.6 | ~ 28 ~ 35 ~ 20 |

[74] |

| PSf+ PA+SPES | 5 bar, 25 oC, Flow feed rate 7 L/min | Na2SO4 MgSO4 |

128.8 115.2 |

99.4 96.5 |

[75] |

| PVDF+CMC+ZnO | 10 bar pH 6 |

Na2SO4 MgSO4 |

139.7 | 95.01 90 |

[76] |

| PPEA+TFC | 10 bar, 80 oC, 2000 mg/L | Na2SO4 |

400 | 96 | [77] |

| PSf+HNT | 9 bar, 2000 mg/L | MgSO4 | 30 | 94.4 | [78] |

| PES+Silica+ BHTTM | 6 bar, 25 oC, 2000 mg/L, Na2SO4, MgSO4 , pH 7 | Na2SO4 MgSO4 |

15.21 | 85 ~ 57 |

[79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).