Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

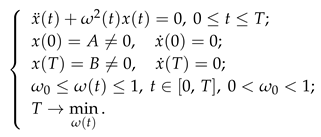

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

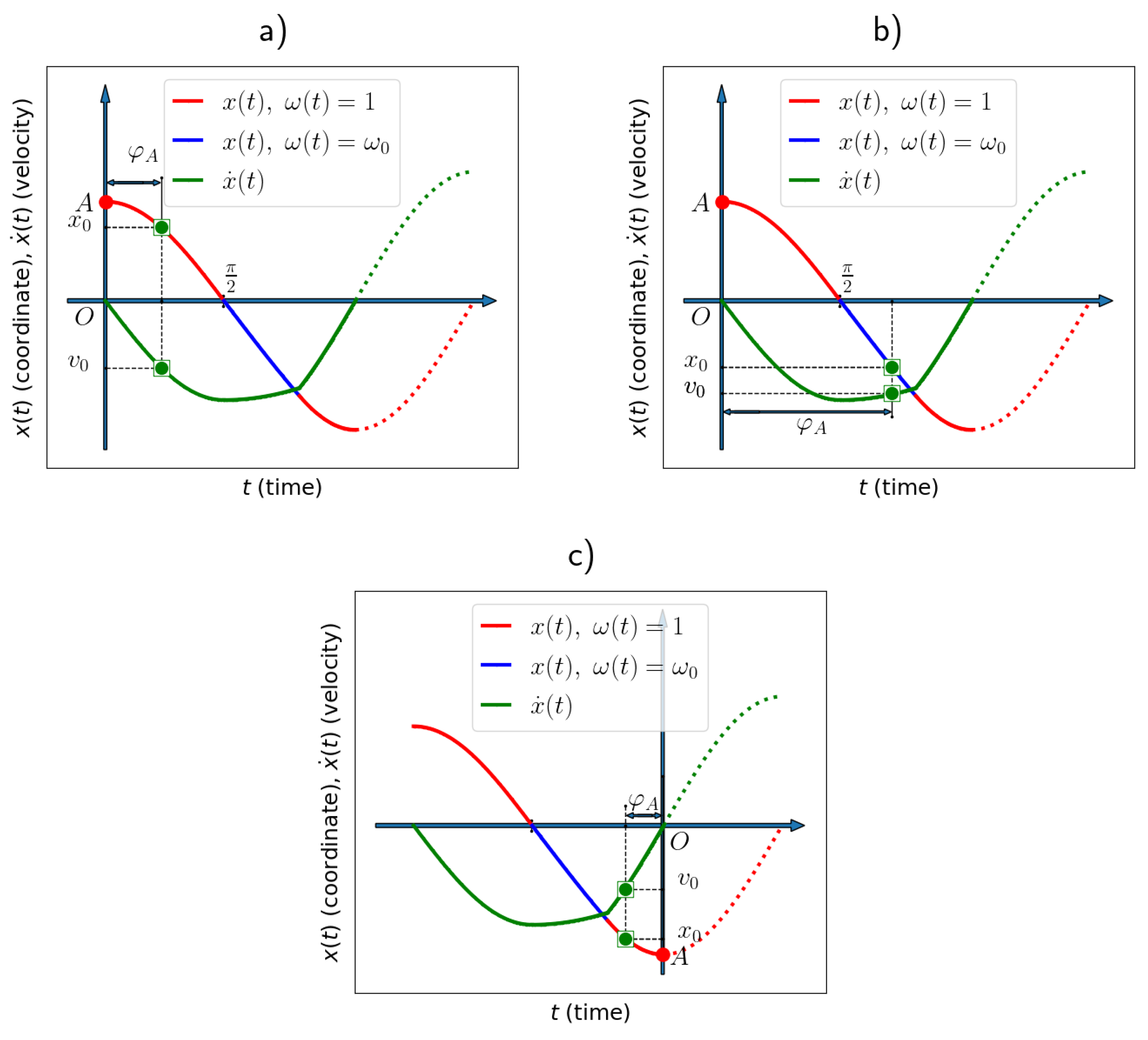

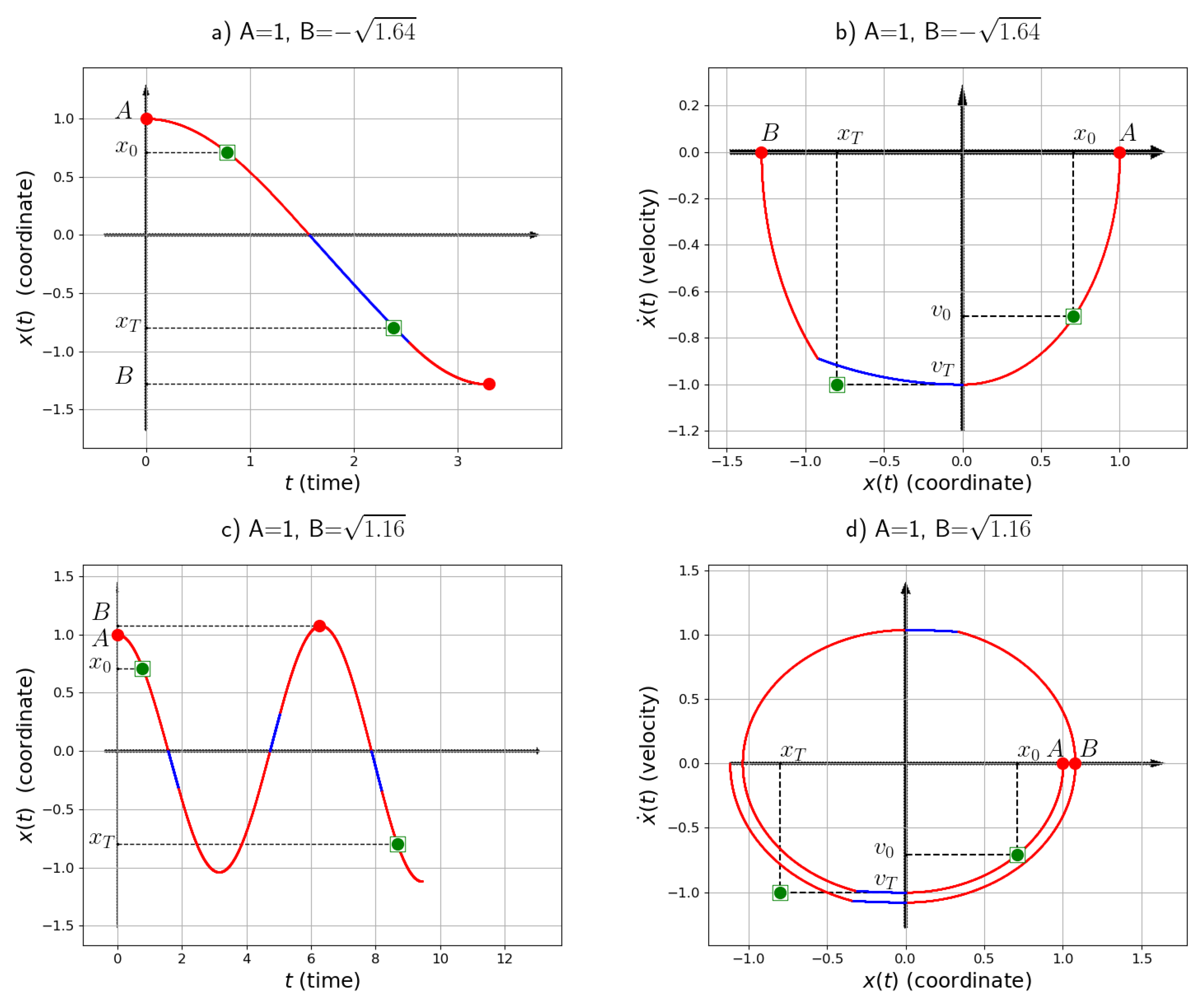

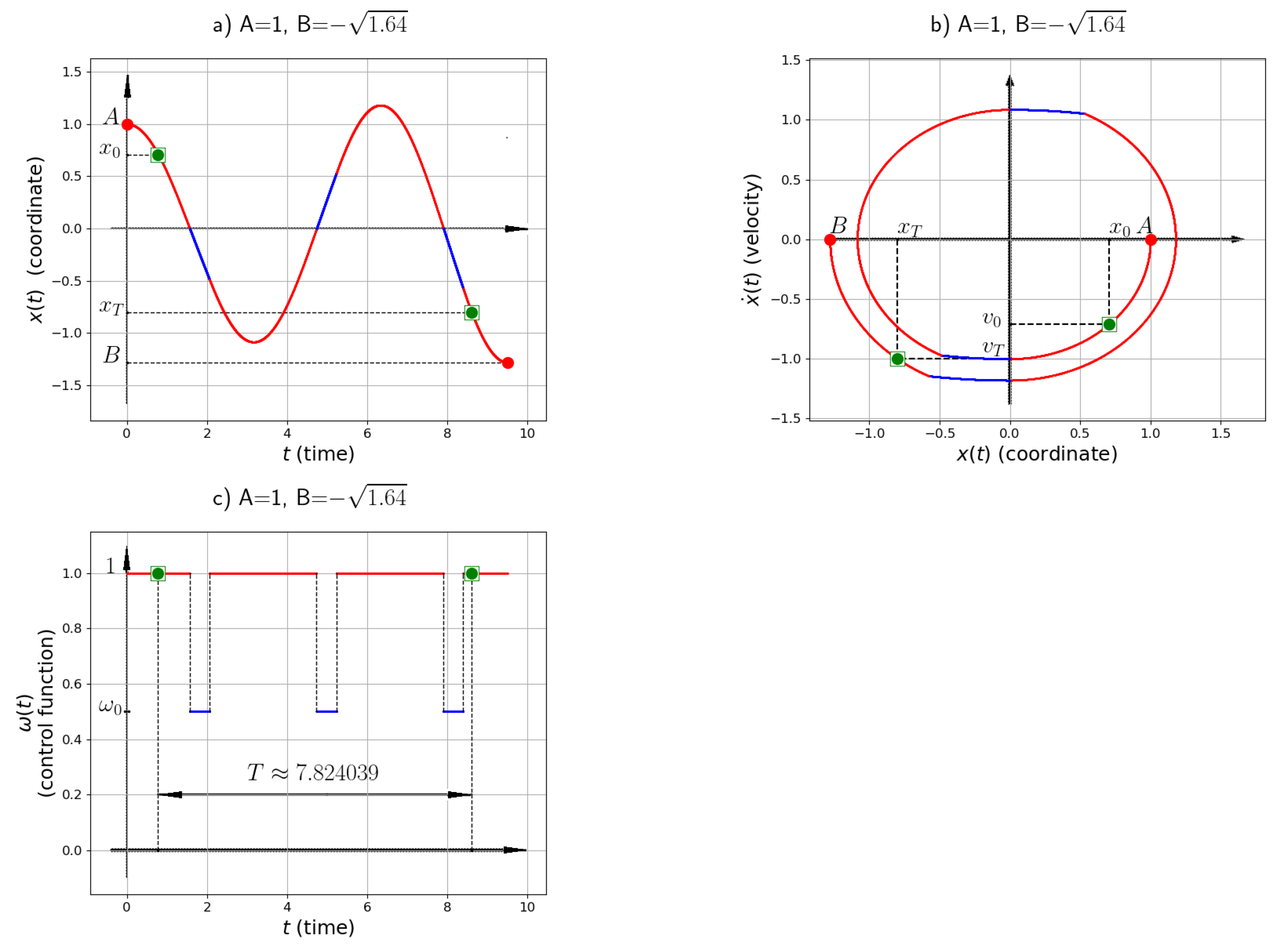

3. Solution of the Problem (1): Theoretical Analysis

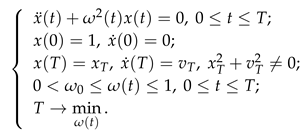

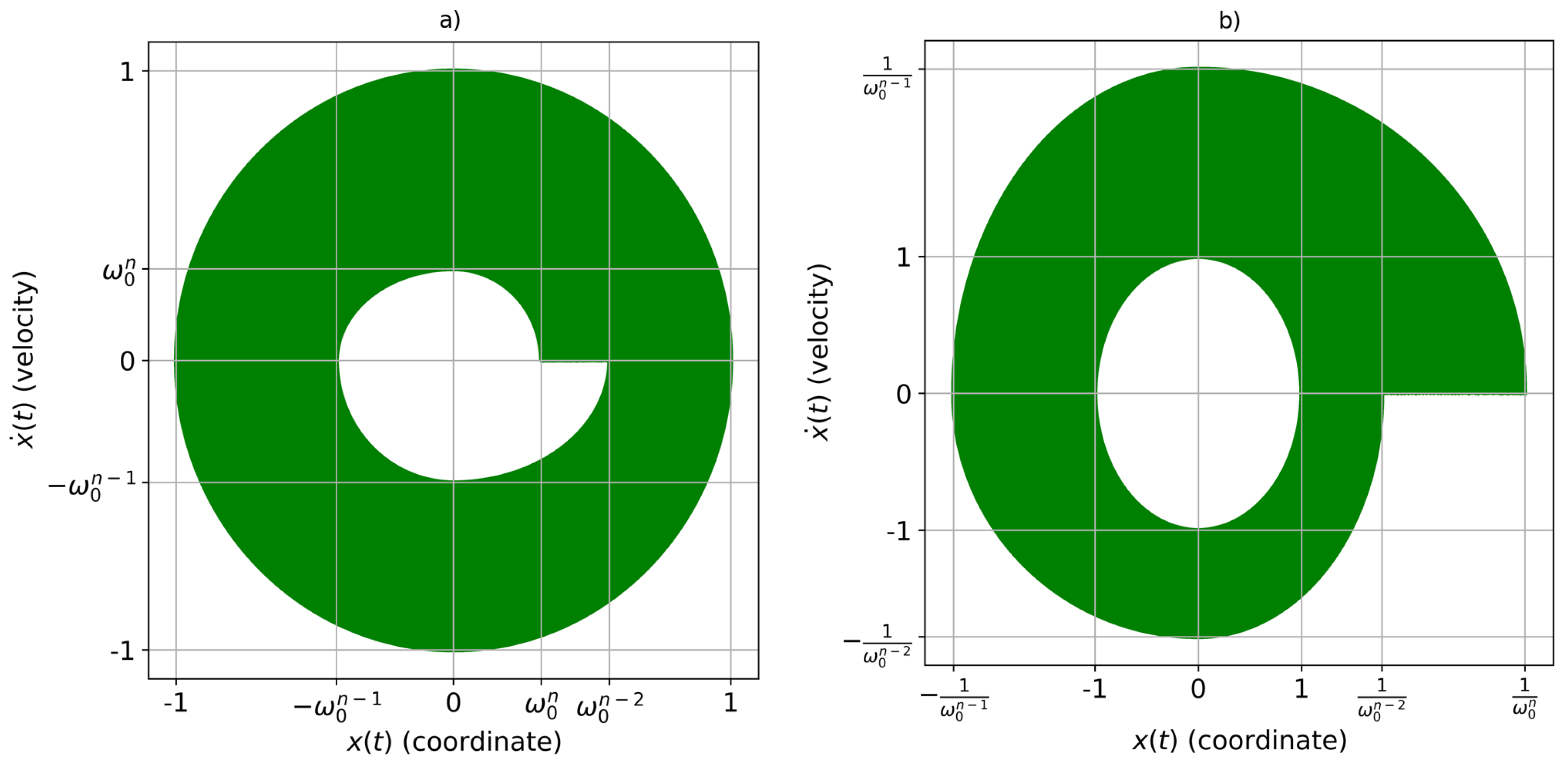

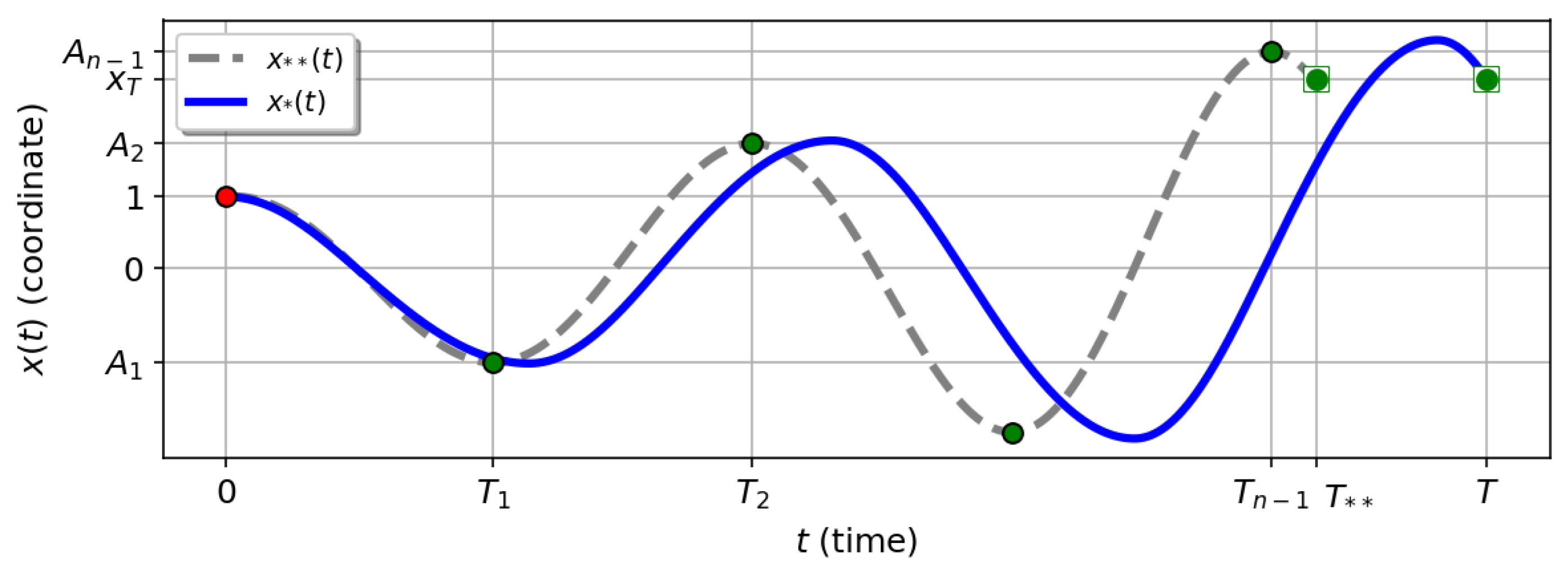

4. Algorithm for Constructing the Solution to Problem (1) via Reduction to a Problem with Zero Derivatives

5. Simulation

6. Main Results

- The problem of optimal control of an oscillatory process is considered in a general setting with non-zero boundary conditions for position and velocity (arbitrary boundary conditions).

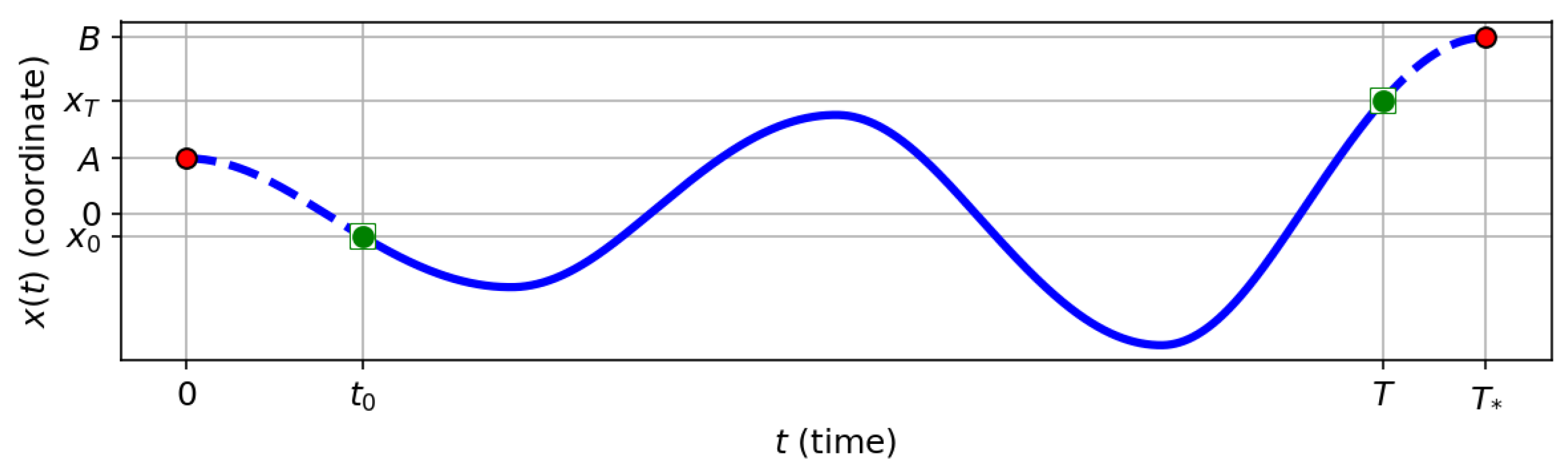

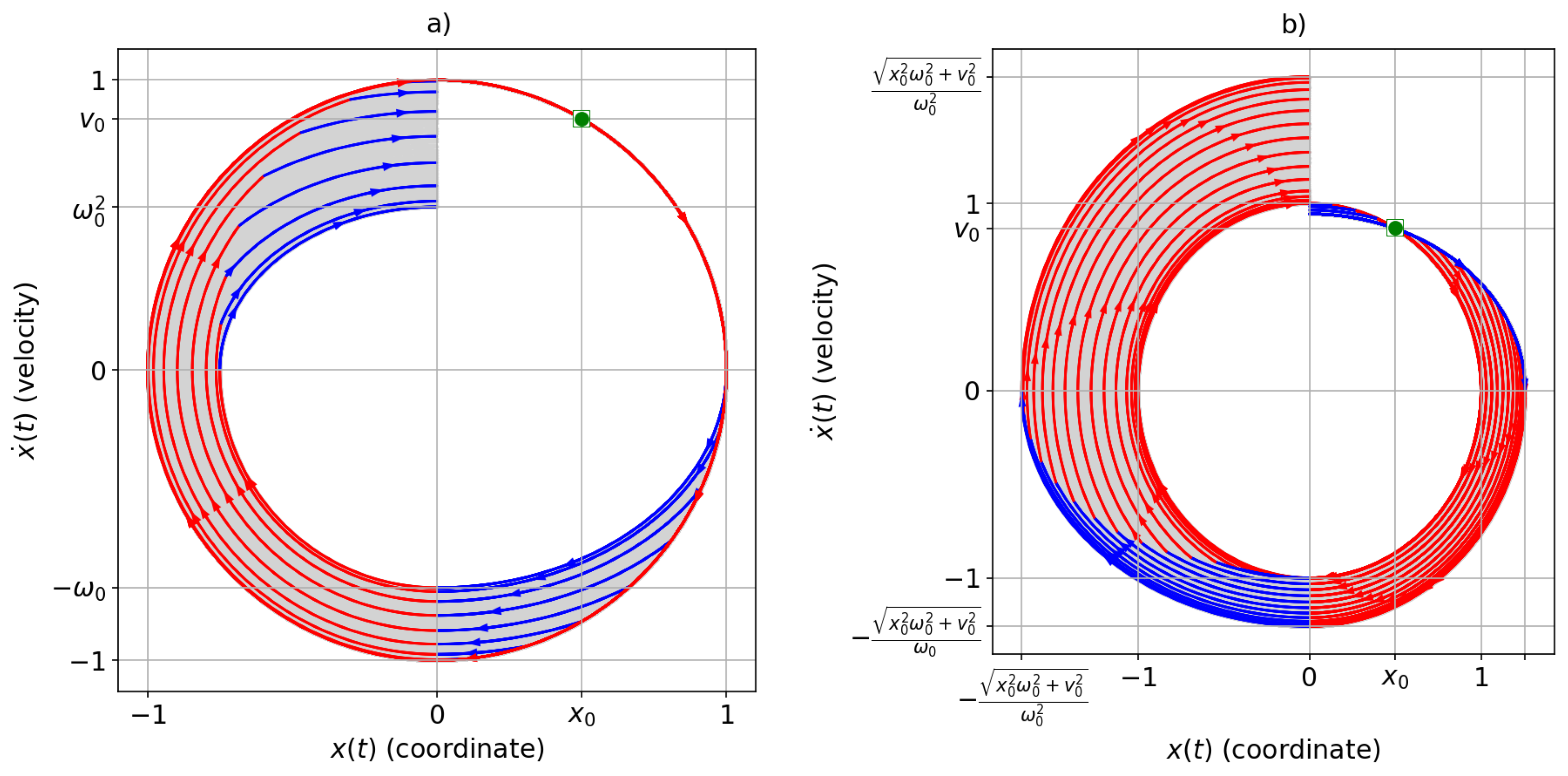

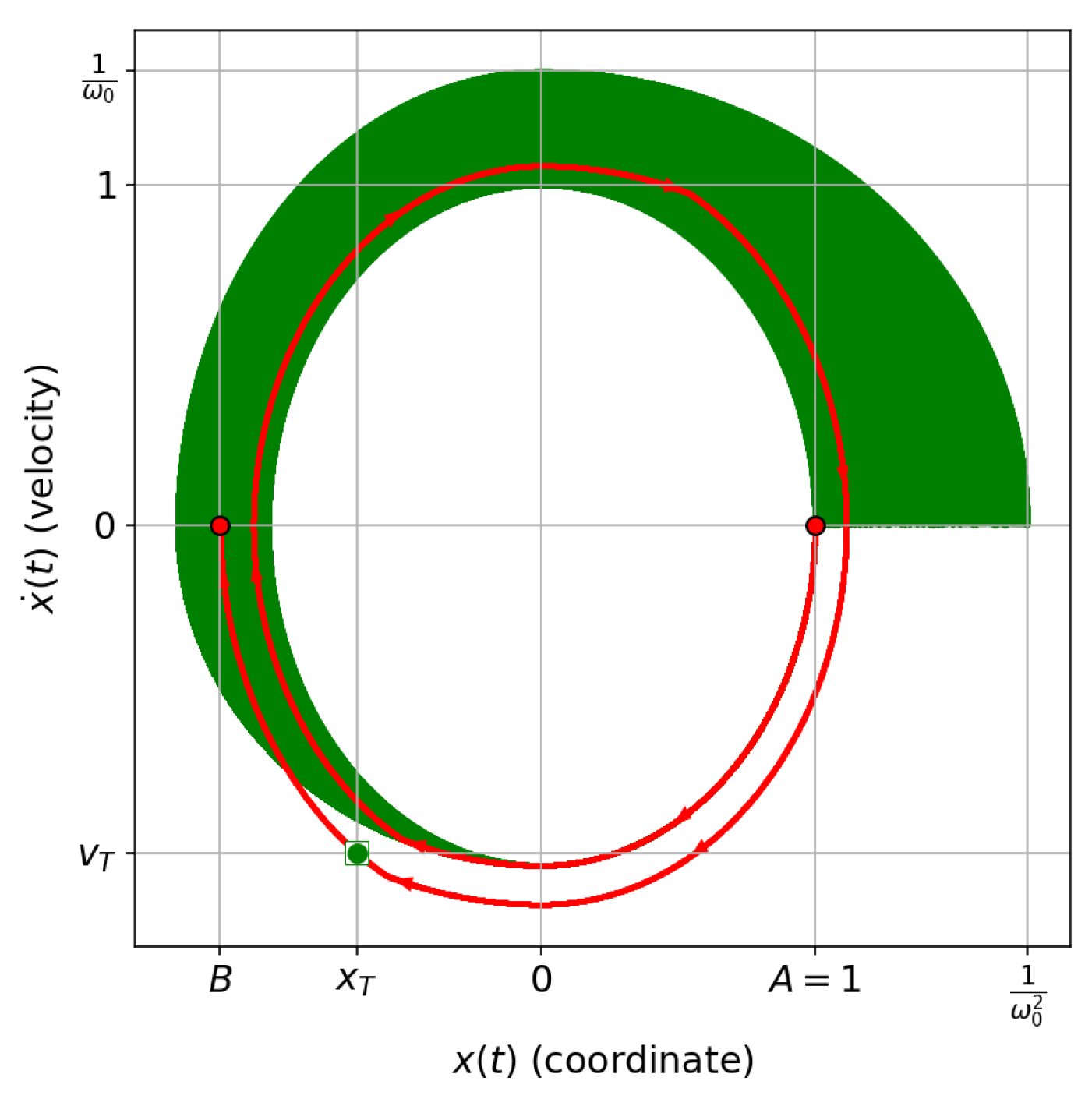

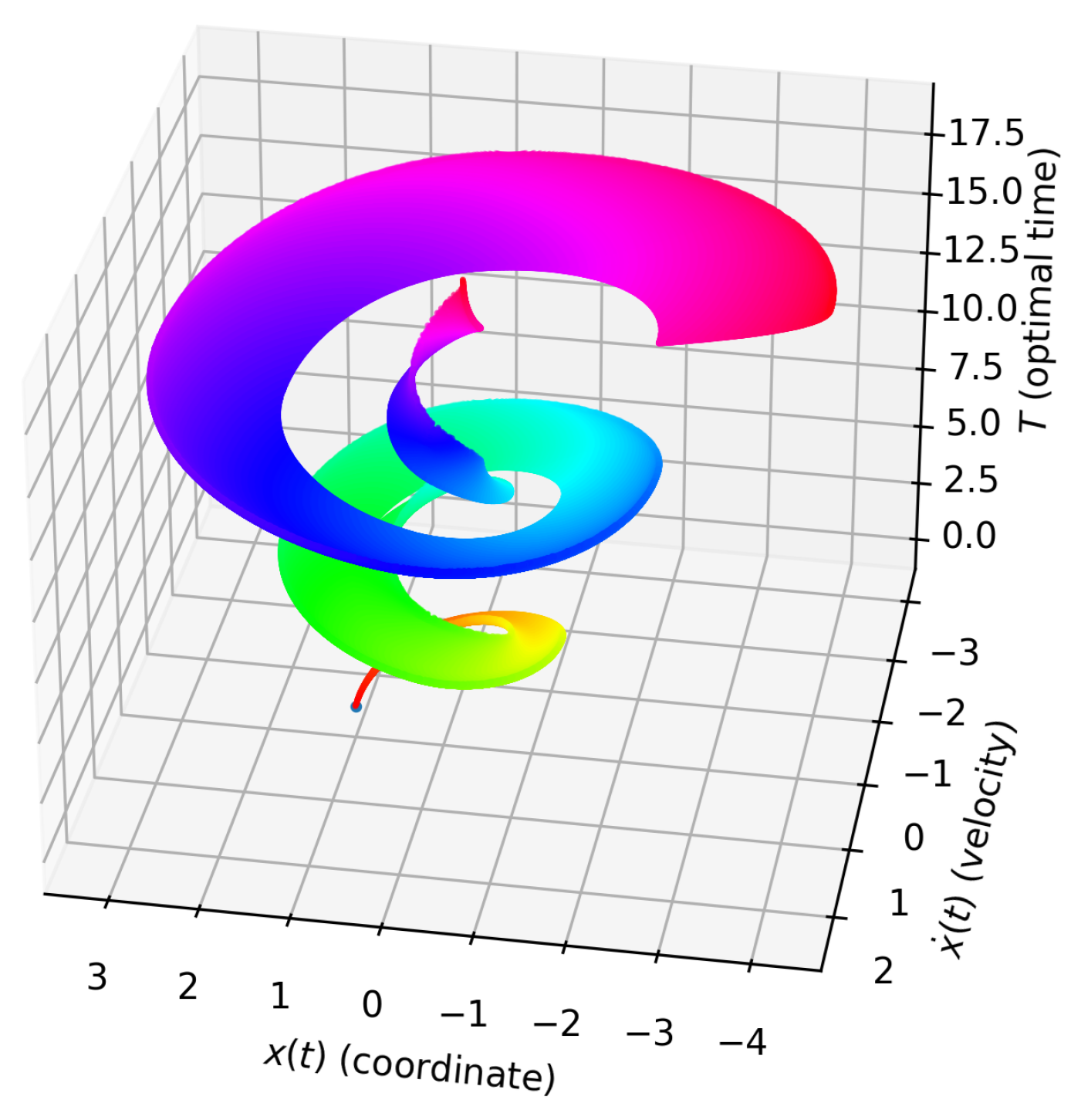

- The existence and optimality of a solution to this problem is proven for any permissible boundary conditions. It is shown that the optimal trajectory is always a part of some trajectory that connects two points with zero velocities and is obtained using periodic control of a specific type.

- A method for solving the problem is proposed, based on extending the solution from the case of zero velocities.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

- Robustness to Uncertainties: A rigorous examination of the robustness of optimal control strategies in the presence of system uncertainties, parameter variations, or external disturbances is warranted.

- Optimal Control with State Constraints: Extending the problem to incorporate state constraints such as limitations on the oscillator’s amplitude or velocity.

- Investigation of Multi-Input Control Systems: Expanding the analysis to encompass systems with multiple control inputs or coupled oscillators, which may exhibit more complex dynamics and control interactions, represents another avenue for research.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Notation | Description |

| t | Time variable |

| , | Coordinate function, Velocity, Acceleration |

| Boundary conditions | |

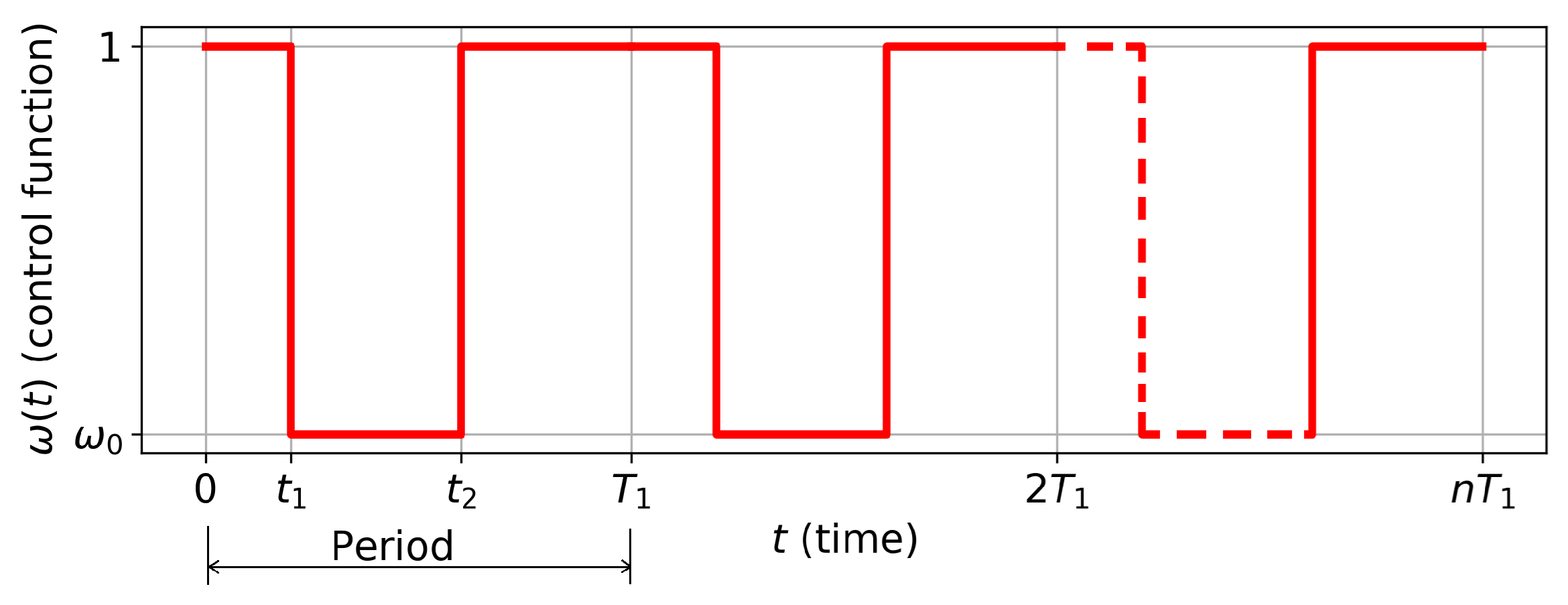

| Control function | |

| Lower limit of the control function | |

| T | Optimal time |

| Duration of one semi-oscillation | |

| Switching points |

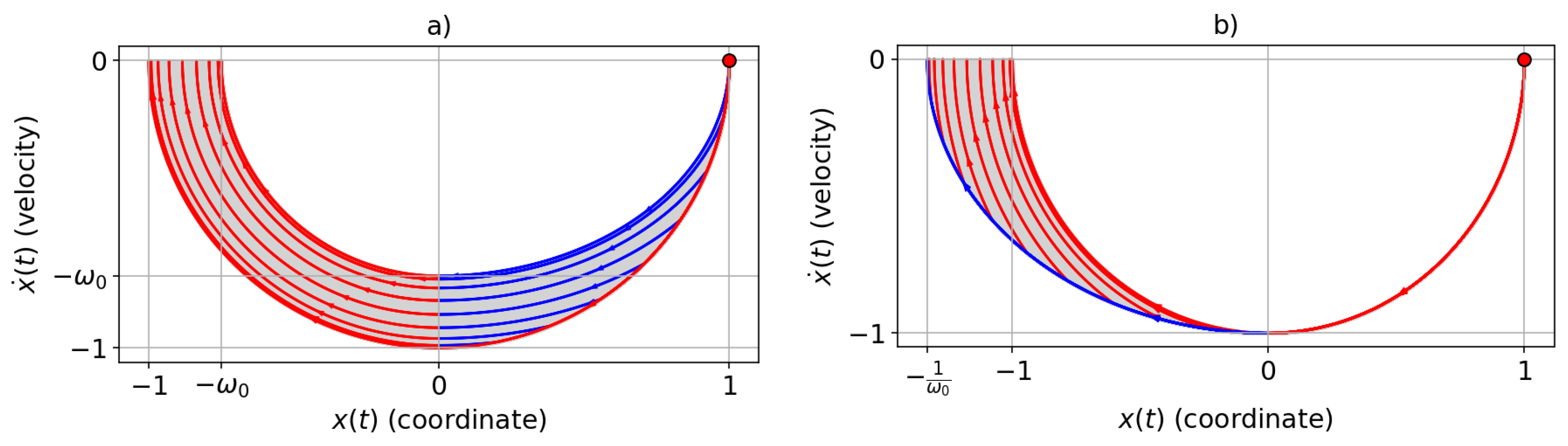

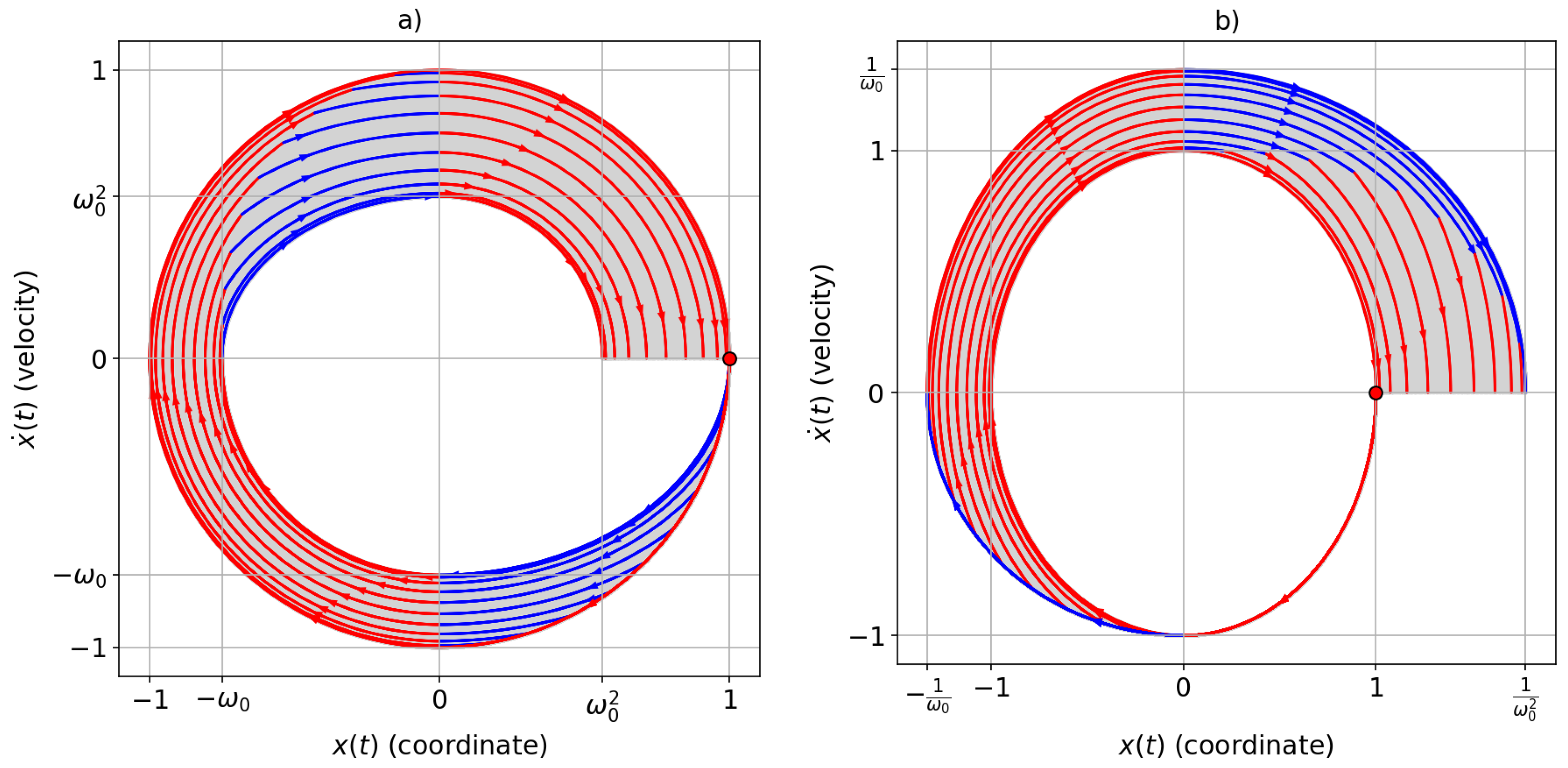

Appendix A. Solution for the Case with v0 = vT = 0

-

Determine the geometric progression with a common ratio q and the number of semi-oscillations n based on the following conditions:The values represent the amplitudes of the semi-oscillations.

- Determine the one semi-oscillation duration and switching points , for the first semi-oscillation:

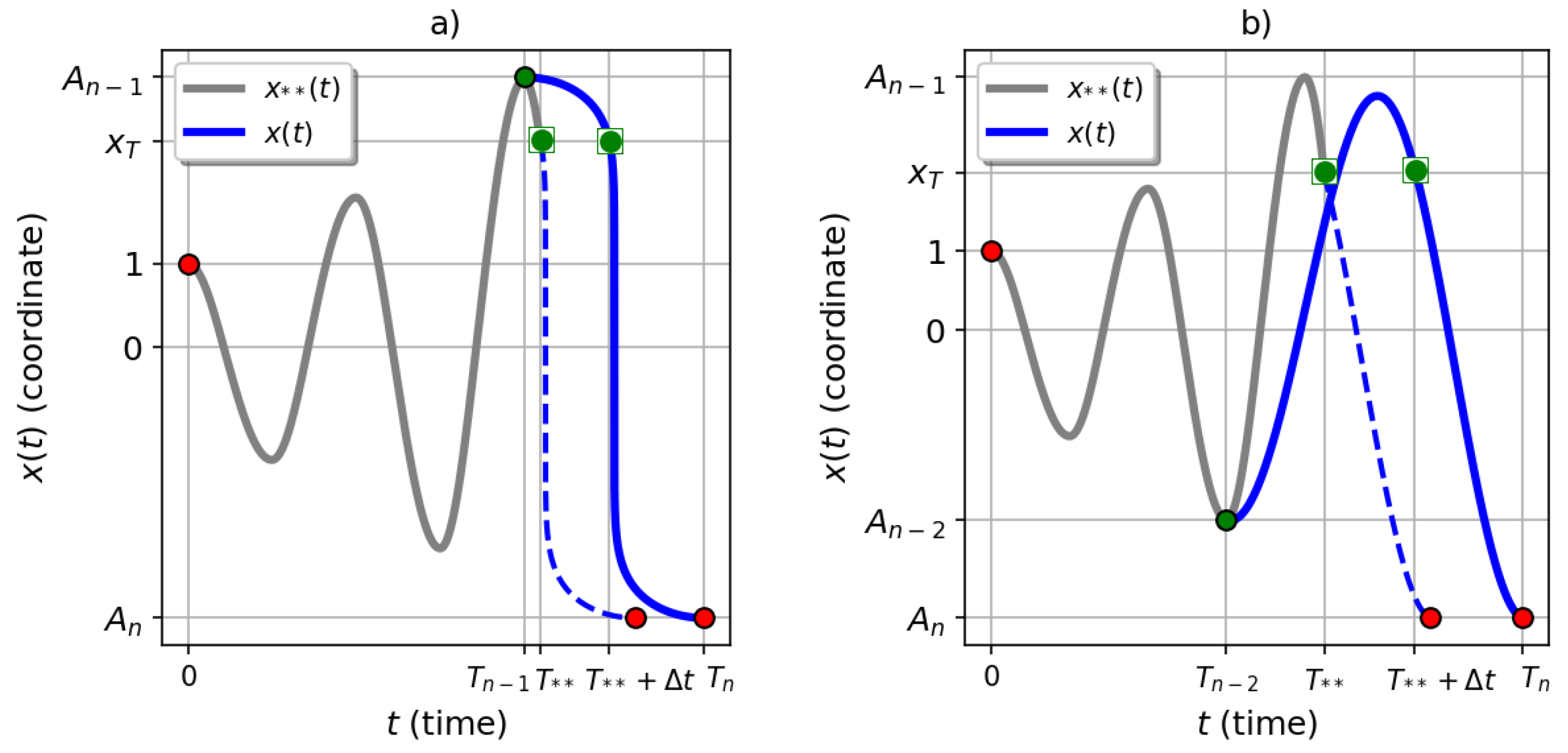

- Find the solution for each semi-oscillation where :

- Determine the final time: the total optimal time for the process is where n is the number of semi-oscillations, and is the duration of one semi-oscillation.

-

Find the switching points for the i-th semi-oscillation:The switching points are given as pairs , where t corresponds to the time of each control switch, and is the trajectory value at that time.

References

- Pontryagin, L.S. Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes (1st ed.). Routledge, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Bryson, A.E. Applied Optimal Control: Optimization, Estimation and Control (1st ed.). Routledge, 1975. [CrossRef]

- Ternovski, V.; Ilyutko, V. Control the Coefficient of a Differential Equation as an Inverse Problem in Time. Mathematics 2024, 12(2), 329. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/12/2/329.

- Hatvani, L. On the parametrically excited pendulum equa- tion with a step function coefficient.Int 5 Non Linear Mech 2015, 77, pp. 172-–182. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Mi; Verriest, Erik; Abdallah, Chaouki. Energy Optimal Control of a Harmonic Oscillator with a State Inequality Constraint. American Control Conference (ACC) 2024, 3662–3667. [CrossRef]

- Kamzolkin, D.; Ternovski, V. Time-Optimal Motions of a Mechanical System with Viscous Friction. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1485. [CrossRef]

- Chengwu, Duan; Rajendra, Singh. Forced vibrations of a torsional oscillator with Coulomb friction under a periodically varying normal load. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2009, Volume 325, Issue 3, pp. 499–506. [CrossRef]

- Andresen, Bjarne; Hoffmann, K.; Nulton, J.; Tsirlin, Anatoliy; Salamon, Peter. Optimal control of the parametric oscillator. Eur. J. Phys. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICS Eur. J. Phys. 3249 2011, pp. 827–843. [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, C Hegerfeldt. Time-optimal transport of a harmonic oscillator: analytic solution. Physica Scripta 2023, Volume 98, Number 9. [CrossRef]

- Milan, Anderle; Pieter, Appeltans; Sergej, Čelikovský; Wim, Michiels; Tomáš, Vyhlídal. Controlling the variable length pendulum: Analysis and Lyapunov based design methods. Journal of the Franklin Institute 2022, Volume 359, Issue 3, pp. 1382-1406. [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, Godiya; Olejnik, Paweł; Awrejcewicz, Jan. On the Modeling and Simulation of Variable-Length Pendulum Systems: A Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2022. [CrossRef]

- Braker, R. A.; Pao, L. Y. Proximate Time-Optimal Control of a Harmonic Oscillator. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control June 2018, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 1676–1691. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, R.; Ilic, R. et al. Fundamental limits and optimal estimation of the resonance frequency of a linear harmonic oscillator. Commun Phys 2021, 4, 207. [CrossRef]

- Xingbao, Huang; Bintang, Yang. Towards novel energy shunt inspired vibration suppression techniques: Principles, designs and applications, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, Volume 182. [CrossRef]

- Meerkov, S.M. Principle of Vibrational Control: Theory and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1980, 25, pp. 755–762. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1980.1102426.

- Andreani, Pietro; Bevilacqua, Andrea. Harmonic Oscillators in CMOS – A Tutorial Overview. IEEE Open Journal of the Solid-State Circuits Society 2021, 1, pp. 2–17. [CrossRef]

- Fares, Abu-Dakka; Matteo, Saveriano; Luka, Peternel. Learning periodic skills for robotic manipulation: Insights on orientation and impedance. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2024, Volume 180. [CrossRef]

- He, Suqin; Hu, Chuxiong; Lin, Shize; Zhu, Yu; Tomizuka, Masayoshi. Real-time time-optimal continuous multi-axis trajectory planning using the trajectory index coordination method. ISA Transactions 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sana, F.; Azad, N.L.; Raahemifar, K. Autonomous Vehicle Decision-Making and Control in Complex and Unconventional Scenarios—A Review. Machines 2023, 11, 676. [CrossRef]

- Eiji, Mizutani; Stuart, Dreyfus. A tutorial on the art of dynamic programming for some issues concerning Bellman’s principle of optimality, ICT Express 2023, Volume 9, Issue 6, pp. 1144–1161. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).