Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

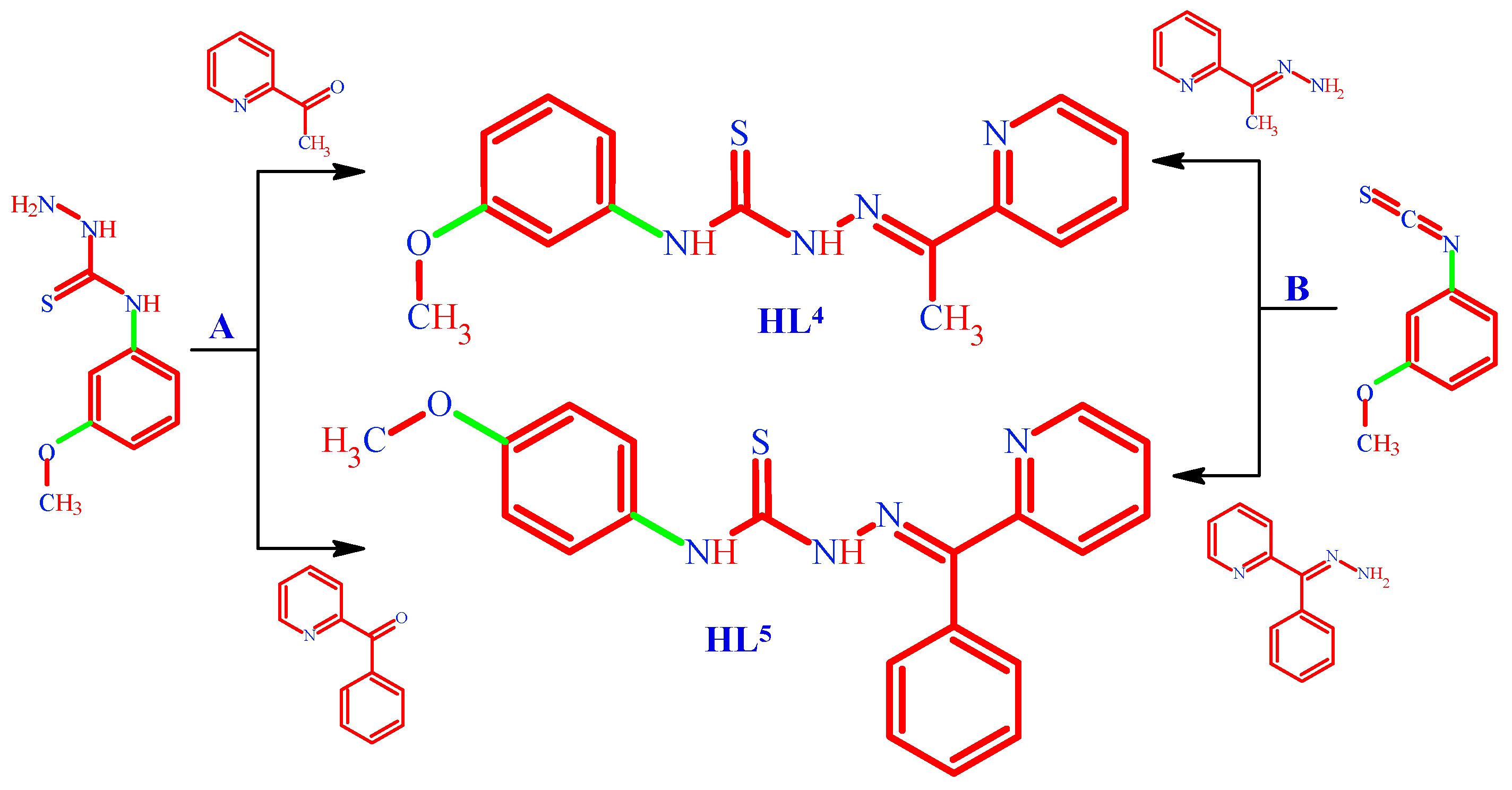

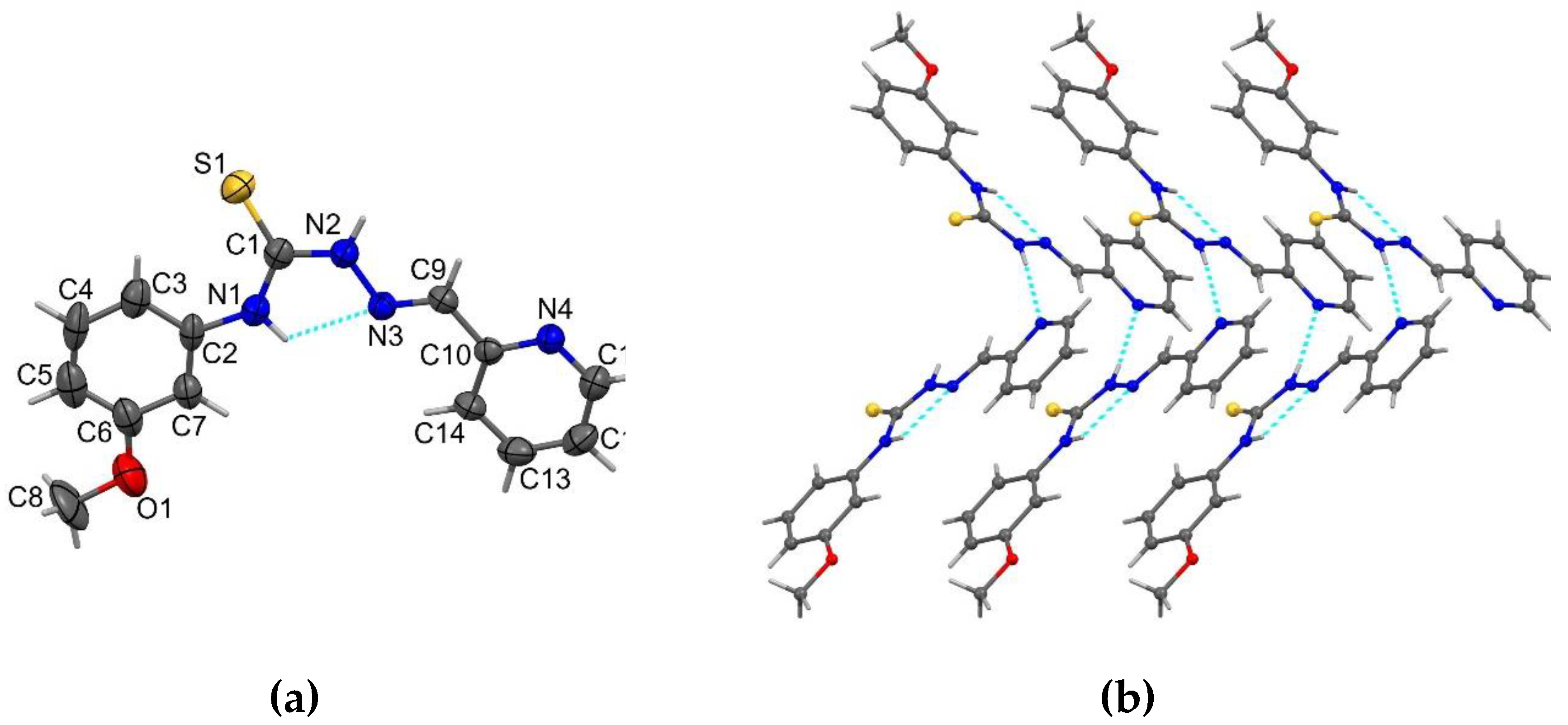

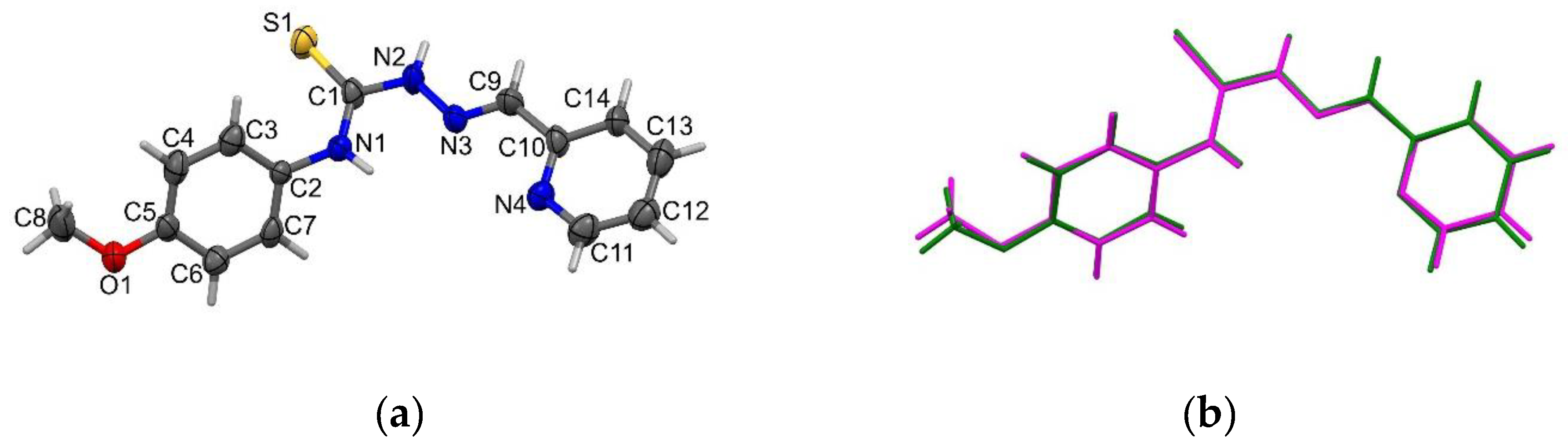

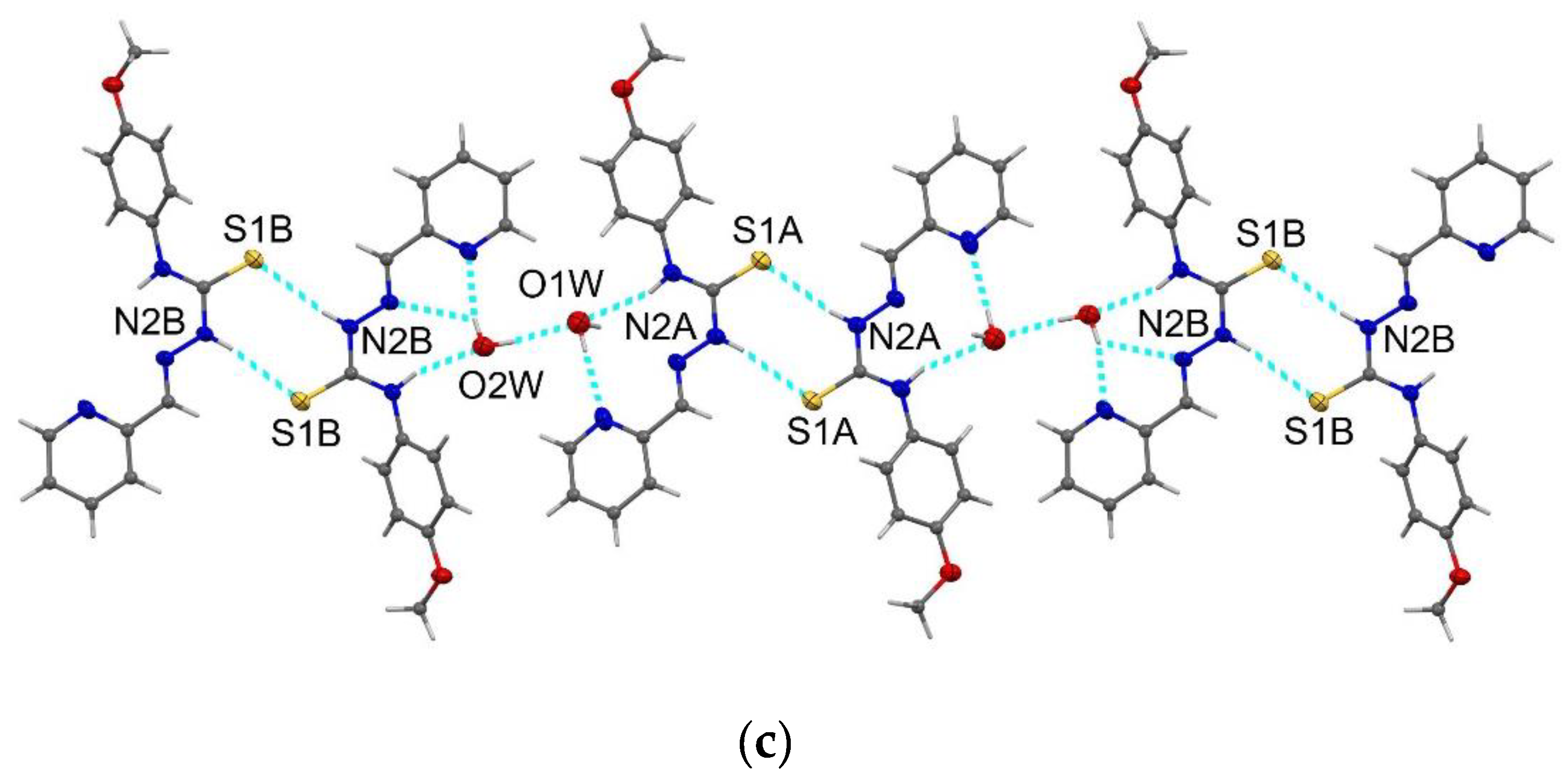

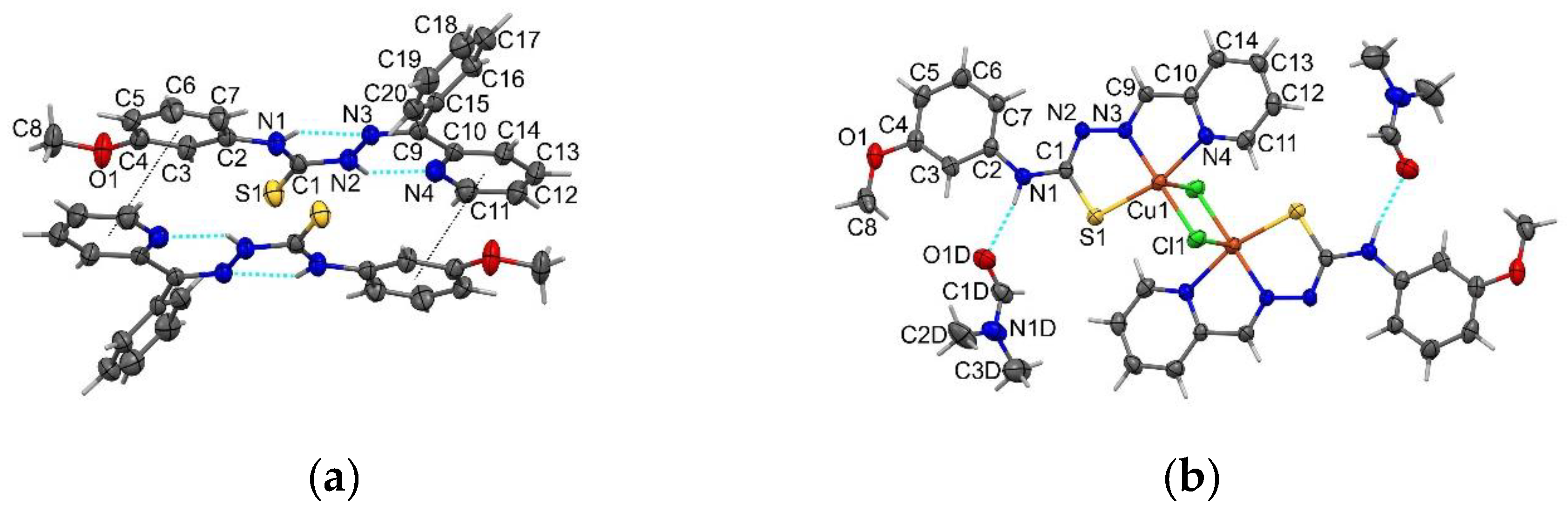

2.1. Structure Description of HL2, HL3, HL5 and Complex C3a

2.2. Biological Activity

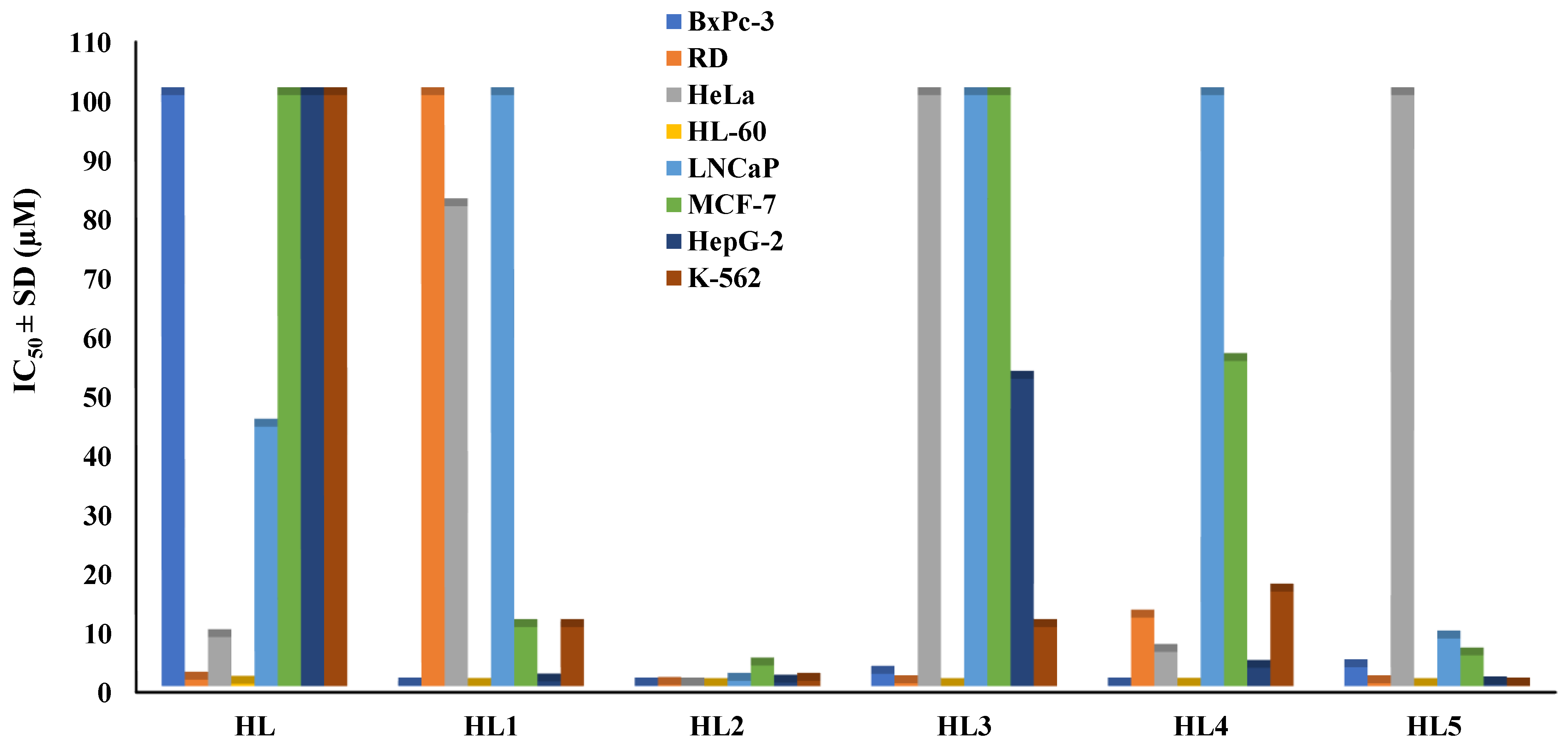

2.2.1. Anticancer Activity and Selectivity

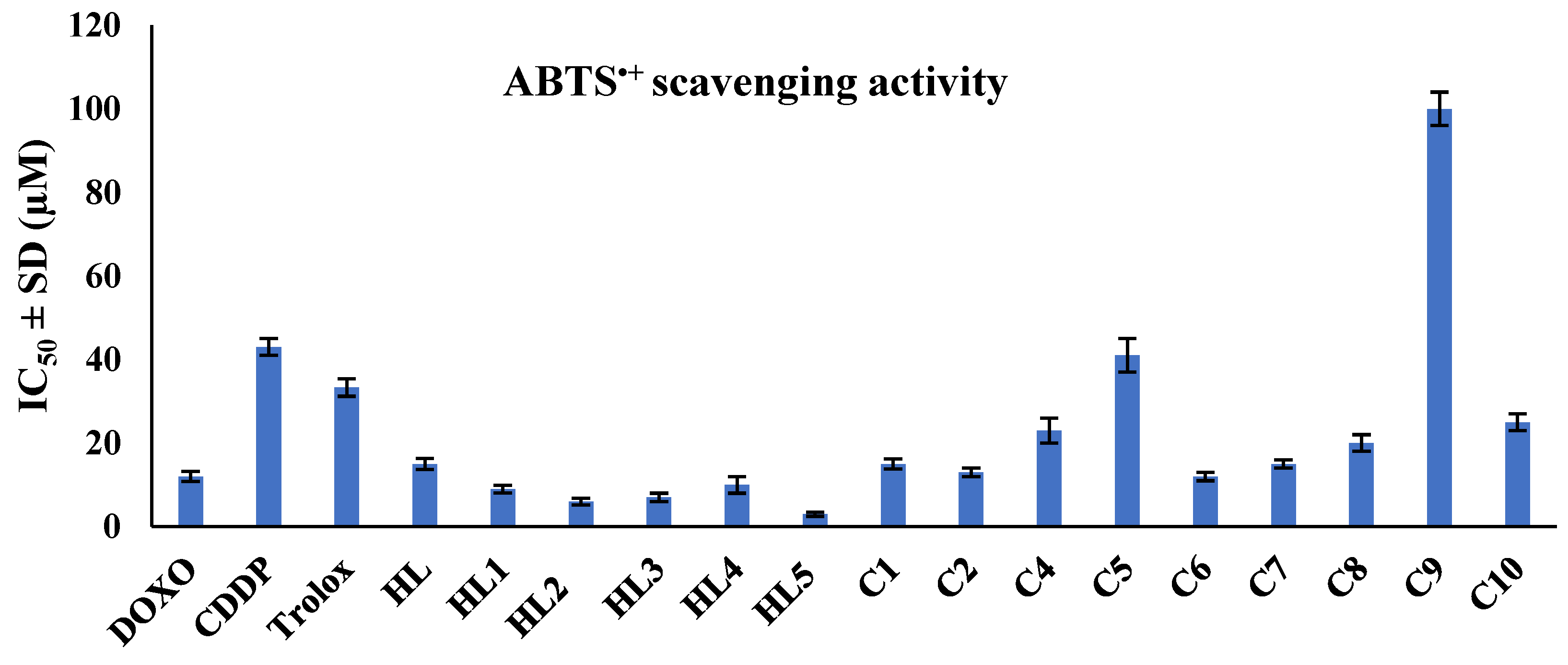

2.2.2. Antioxidant Activity

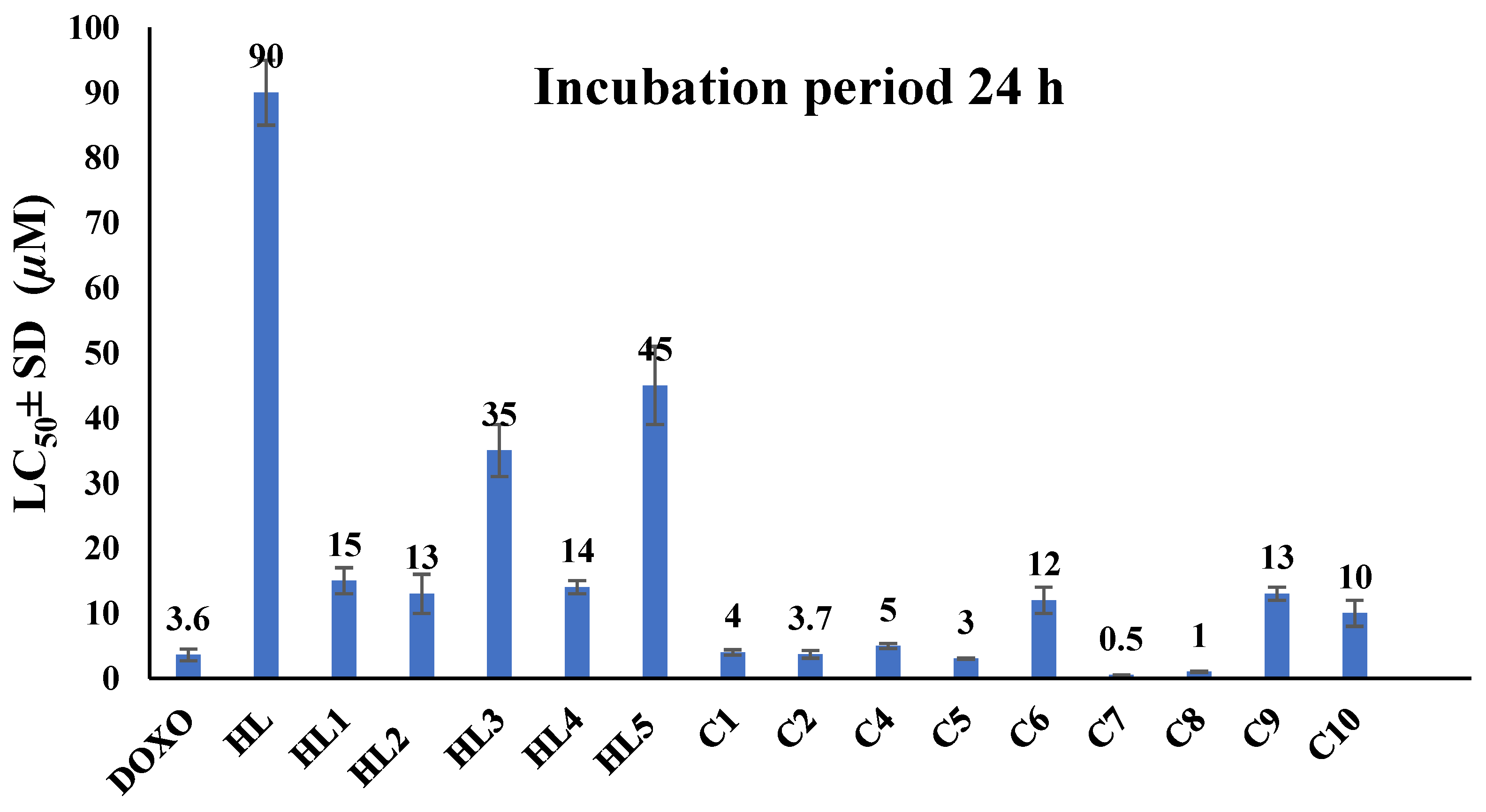

2.2.3. In Vivo Toxicity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

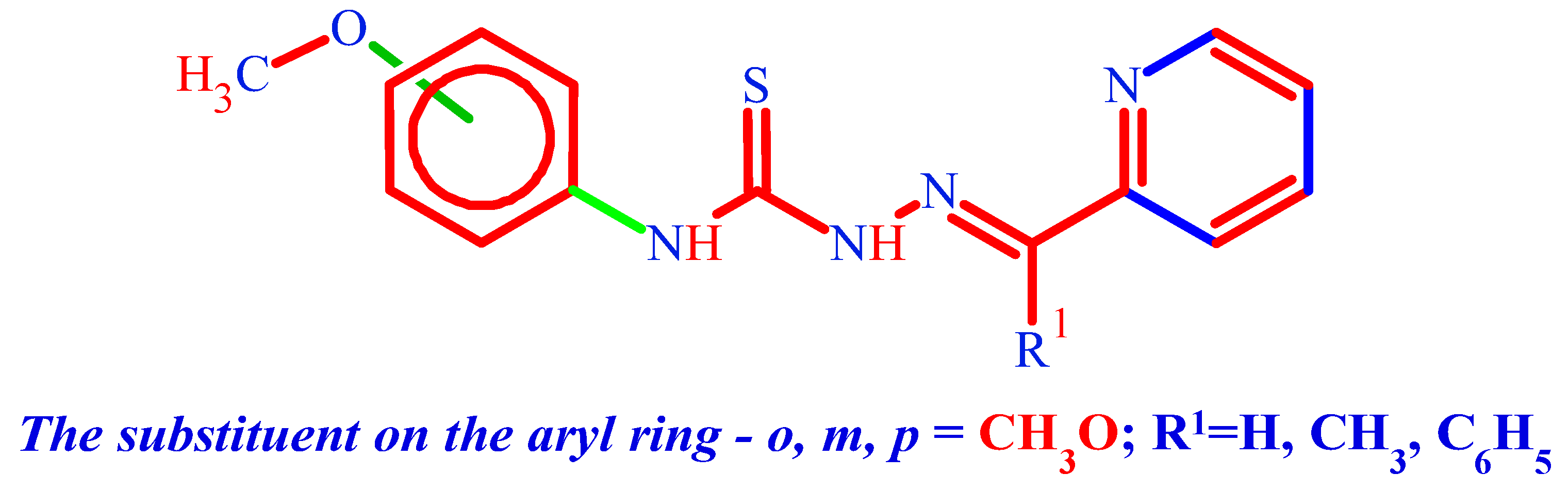

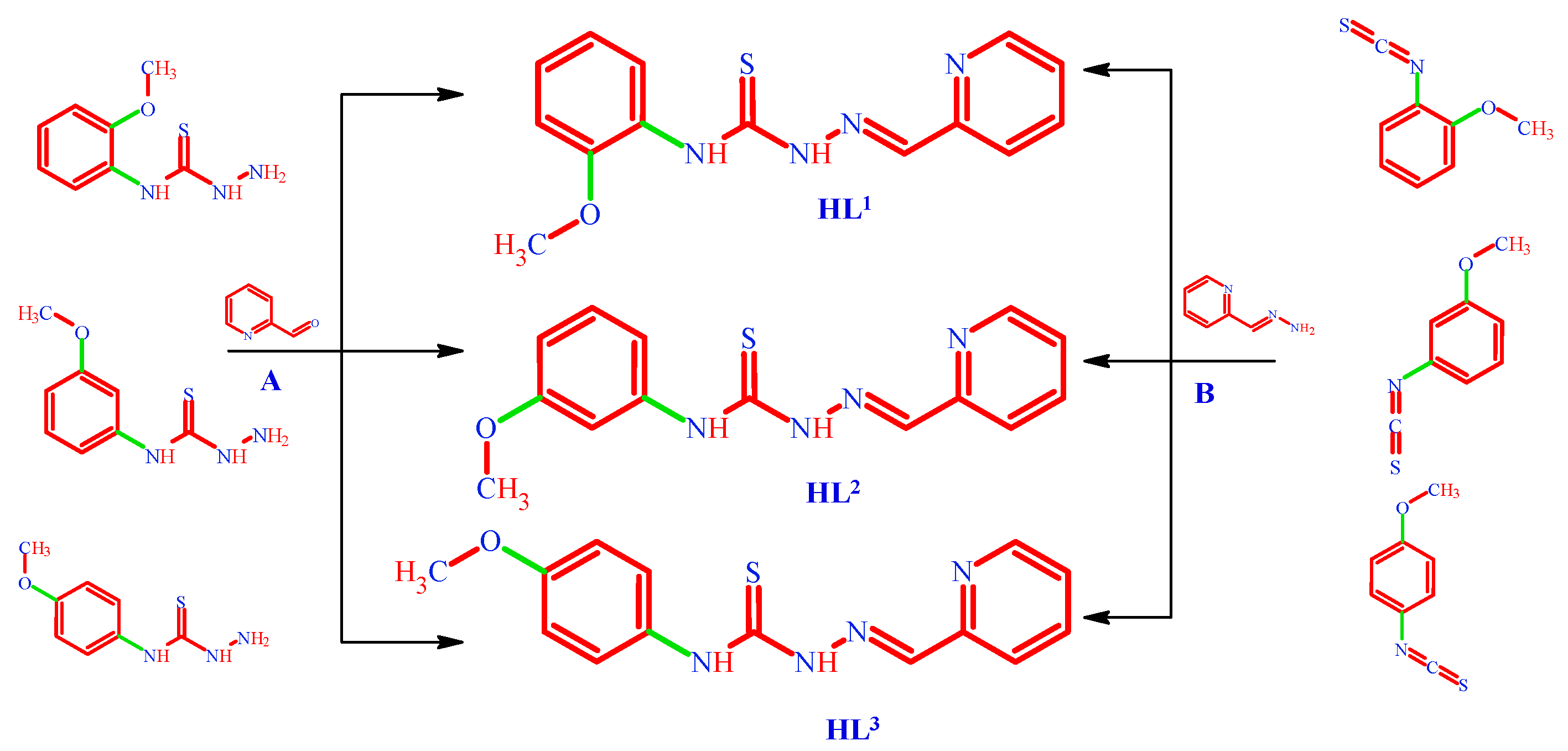

3.1.1. (. HL1) N-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2-[(pyridin-2-yl)methylidene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide

3.1.2. (. HL2) N-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-[(pyridin-2-yl)methylidene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide

3.1.3. (. HL3) N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-[(pyridin-2-yl)methylidene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide

3.1.4. (. HL4) N-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-[1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide

3.1.5. (HL5) N-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2-[phenyl(pyridin-2-yl)methylidene]hydrazine-1-carbothioamide

3.2. Synthesis of copper(II) complexes (C1-10)

3.3. FT-IR Spectroscopy

3.4. NMR Spectroscopy

3.5. Molar Conductivity

3.6. Melting Point

3.7. Thin Layer Chromatographic

3.8. X-Ray Crystallography

| Compound | HL2 | HL3 | HL5 | C3a |

| CCDC | 2400994 | 2400995 | 2400996 | 2400997 |

| Empirical formula | C14H14N4O1S1 | C14H16N4O2S1 | C20H18N4O1S1 | C34H40Cl2Cu2N10O4S2 |

| Formula weight | 286.35 | 304.37 | 362.44 | 914.86 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c | P-1 | P21/n | P21/c |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||||

| a (Å) | 14.6756(16) | 9.5549(18) | 9.7269(6) | 7.1034(5) |

| b (Å) | 5.3717(5) | 12.804(3) | 16.9246(8) | 23.3341(19) |

| c (Å) | 18.506(2) | 14.078(3) | 11.1893(6) | 12.2189(10) |

| α (°) | 90 | 109.966(18) | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 102.331(10) | 97.625(15) | 96.043(5) | 102.395(7) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 108.195(19) | 90 | 90.895(7) |

| V (Å3) | 1425.2(3) | 1481.6(6) | 1831.8(2) | 90 |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| ρcalc (g cm-3) | 1.335 | 1.365 | 1.314 | 1.536 |

| μMo (mm-1) | 0.228 | 0.229 | 0.193 | 0.928 |

| F(000) | 600 | 640 | 760 | 940 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.80x0.05x0.03 | 0.15x0.07x0.05 | 0.60x0.17x0.08 | 0.60x0.10x0.03 |

| θ Range (°) | 3.228 – 25.05 | 2.968–24.499 | 2.932 – 25.044 | 3.063 – 25.05 |

| Index range | –17 ≤ h ≤ 10, –6 ≤ k ≤ 3, –16 ≤ l ≤ 22 |

–11 ≤ h ≤ 11, –14 ≤ k ≤ 14, –16 ≤ l ≤ 142 |

–11≤ h ≤ 11, –20 ≤ k ≤ 19, –13 ≤ l ≤ 6 |

–8 ≤ h ≤ 8, –16 ≤ k ≤ 27, –14 ≤ l ≤ 14 |

| Reflections collected / unique | 2519 / 2519 (Rint = 0.0297) |

8287 / 4909 (Rint = 0.0699) |

5970 / 3238 (Rint = 0.0236) |

10960 / 3506 (Rint = 0.0672) |

| Reflections with I > 2σ(I) |

1351 | 1800 | 2230 | 2636 |

| Number of refined parameters | 182 | 393 | 236 | 247 |

| Goodness-of-fit (GOF) | 0.998 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.003 |

| R (for I > 2σ(I)) |

R1 = 0.0561, wR2 = 0.1001 |

R1 = 0.0860, wR2 = 0.1240 |

R1 = 0.0463, wR2 = 0.1081 |

R1 = 0.0629, wR2 = 0.1668 |

| R (for all reflections) |

R1 = 0.1227, wR2 = 0.1242 |

R1 = 0.2230, wR2 = 0.1610 |

R1 = 0.0763, wR2 = 0.1236 |

R1 = 0.0864, wR2 = 0.1897 |

| Δρmax/Δρmin (e⋅Å-3) | 0.206 / -0.181 | 0.499 / –0.266 | 0.179 / –0.199 | 0.922 / –0.515 |

3.9. Cell Proliferation Resazurin Assay

3.10. Cell Proliferation MTT Assay

3.11. ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging assay

3.12. Acute Toxicity Assay Against Daphnia Magna

3.13. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, M.B.; Islam, M.I.; Nath, N.; Emran, T. Bin; Rahman, M.R.; Sharma, R.; Matin, M.M. Recent Advances in Pyridine Scaffold: Focus on Chemistry, Synthesis, and Antibacterial Activities. Biomed Res. Int. 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fuior, A.; Cebotari, D.; Haouas, M.; Marrot, J.; Espallargas, G.M.; Guérineau, V.; Touboul, D.; Rusnac, R. V.; Gulea, A.; Floquet, S. Synthesis, Structures, and Solution Studies of a New Class of [Mo 2 O 2 S 2 ]-Based Thiosemicarbazone Coordination Complexes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16547–16560. [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.A.; Lessa, J.A.; Mendes, I.C.; Da Silva, J.G.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Salum, L.B.; Daghestani, H.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Day, B.W.; Vogt, A.; et al. N 4-Phenyl-Substituted 2-Acetylpyridine Thiosemicarbazones: Cytotoxicity against Human Tumor Cells, Structure-Activity Relationship Studies and Investigation on the Mechanism of Action. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3396–3409. [CrossRef]

- Biot, C.; Pradines, B.; Sergeant, M.H.; Gut, J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Chibale, K. Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Activity of Structural Chimeras of Thiosemicarbazone and Ferroquine Analogues. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6434–6438. [CrossRef]

- Klenc, J.; Raux, E.; Barnes, S.; Sullivan, S.; Duszynska, B.; Bojarski, A.J.; Strekowski, L. Synthesis of 4-Substituted 2- ( 4-Methylpiperazino ) Pyrimidines and Quinazoline Analogs as Serotonin 5-HT 2A Receptor Ligands. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009, 46, 1259–1265. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S.; Silva, T.L. da One-Pot and Catalyst-Free Synthesis of Thiosemicarbazones via Multicomponent Coupling Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 2090–2093. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Bo-Wang; Tao, Y.-Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, H.-J.; He, Z.-X.; Wu, H.-P.; Li, Y.-H.; Zhao, B.; Ma, L.-Y.; et al. Thiosemicarbazone-Based Lead Optimization to Discover High-Efficiency and Low-Toxicity Anti-Gastric Cancer Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 199, 112349. [CrossRef]

- Ilies, D.C.; Pahontu, E.; Shova, S.; Georgescu, R.; Stanica, N.; Olar, R.; Gulea, A.; Rosu, T. Synthesis, Characterization, Crystal Structure and Antimicrobial Activity of Copper(II) Complexes with a Thiosemicarbazone Derived from 3-Formyl-6-Methylchromone. Polyhedron 2014, 81, 123–131. [CrossRef]

- Gulea, A.; Poirier, D.; Roy, J.; Stavila, V.; Bulimestru, I.; Tapcov, V.; Birca, M.; Popovschi, L. In Vitro Antileukemia, Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Some 3d Metal Complexes: Chemical Synthesis and Structure - Activity Relationships. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2008, 23, 806–818. [CrossRef]

- Pahontu, E.; Julea, F.; Rosu, T.; Purcarea, V.; Chumakov, Y.; Petrenco, P.; Gulea, A. Antibacterial, Antifungal and in Vitro Antileukaemia Activity of Metal Complexes with Thiosemicarbazones. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 865–878. [CrossRef]

- Bacher, F.; Dömötör, O.; Enyedy, É.A.; Filipović, L.; Radulović, S.; Smith, G.S.; Arion, V.B. Complex Formation Reactions of Gallium(III) and Iron(III/II) with L-Proline-Thiosemicarbazone Hybrids: A Comparative Study. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2017, 455, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, A.; Fesenko, A.; Yankov, A.; Stepanenko, I.; Darvasiová, D.; Breza, M.; Rapta, P.; Martins, L.M.D.R.S.; Pombeiro, A.J.L.; Shutalev, A.; et al. Nickel(II), Copper(II) and Palladium(II) Complexes with Bis-Semicarbazide Hexaazamacrocycles: Redox-Noninnocent Behavior and Catalytic Activity in Oxidation and C–C Coupling Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 10650–10664. [CrossRef]

- Kowol, C.R.; Berger, R.; Eichinger, R.; Roller, A.; Jakupec, M.A.; Schmidt, P.P.; Arion, V.B.; Keppler, B.K. Gallium(III) and Iron(III) Complexes of α-N-Heterocyclic Thiosemicarbazones: Synthesis, Characterization, Cytotoxicity, and Interaction with Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1254–1265. [CrossRef]

- Patel, E.N.; Lin, L.; Park, H.; Sneller, M.M.; Eubanks, L.M.; Tepp, W.H.; Pellet, S.; Janda, K.D. Investigations of Thiosemicarbazides as Botulinum Toxin Active-Site Inhibitors: Enzyme, Cellular, and Rodent Intoxication Studies. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S.C.; Wiese, M. HM30181 Derivatives as Novel Potent and Selective Inhibitors of the Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2). J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3910–3921. [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J.M.; Perez-Ramirez, B.; Gorbunoff, M.J.; Ayala, D.; Timasheff, S.N. Role of the Colchicine Ring A and Its Methoxy Groups in the Binding to Tubulin and Microtubule Inhibition. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 8356–8368. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Sun, Q.; Shi, X.; Yin, Z.; Zeng, B.; Huang, Z.; Li, X. Co-Modification of Engineered Cellulose Surfaces Using Antibacterial Copper-Thiosemicarbazone Complexes and Flame Retardants. Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 51, 104688. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Abser, M.N.; Kumer, A.; Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Akter, P.; Hossain, M.E.; Chakma, U. Synthesis, Characterization, Antibacterial Activity of Thiosemicarbazones Derivatives and Their Computational Approaches: Quantum Calculation, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamic, ADMET, QSAR. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16222. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Hansda, A.; Chandra, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Sithambaresan, M.; Faizi, M.S.H.; Kumar, V.; John, R.P. Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) Complexes of Acenaphthoquinone 3-(4-Benzylpiperidyl)Thiosemicarbazone: Synthesis, Structural, Electrochemical and Antibacterial Studies. Polyhedron 2017, 134, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, W.; Hussain, M.; Ali, A.; Shafiq, N.; Chughtai, A.H.; Shakoor, B.; Moveed, A.; Shoukat, M.N.; Milošević, M.; Mohany, M. Design, Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Screening of Novel Thiosemicarbazones and Their Derivatives with Potent Antibacterial and Antidiabetic Activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1320. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dhingra, N.; Singh, H.L. Design, Spectral, Antibacterial and in-Silico Studies of New Thiosemicarbazones and Semicarbazones Derived from Symmetrical Chalcones. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1307, 138000. [CrossRef]

- Terenti, N.; Lazarescu, A.; Shova, S.; Bourosh, P.; Nedelko, N.; Ślawska-Waniewska, A.; Zariciuc, E.; Lozan, V. Synthesis, X-Ray and Antibacterial Activity of New Copper(II) Thiosemicarbazone Complexes Derived from 4-Formyl-3-Hydroxy-2-Naphthoic Acid. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2024, 571. [CrossRef]

- Damit, N.S.H.H.; Hamid, M.H.S.A.; Rahman, N.S.R.H.A.; Ilias, S.N.H.H.; Keasberry, N.A. Synthesis, Structural Characterisation and Antibacterial Activities of Lead(II) and Some Transition Metal Complexes Derived from Quinoline-2-Carboxaldehyde 4-Methyl-3-Thiosemicarbazone. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2021, 527, 120557. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shi, Z.; Liu, M.; Liu, X. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis and in Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Novel Steroidal Thiosemicarbazone Derivatives. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7730–7734. [CrossRef]

- Soraires Santacruz, M.C.; Fabiani, M.; Castro, E.F.; Cavallaro, L. V.; Finkielsztein, L.M. Synthesis, Antiviral Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of N4-Aryl Substituted/Unsubstituted Thiosemicarbazones Derived from 1-Indanones as Potent Anti-Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 4055–4063. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.S.; Chigan, J.Z.; Li, J.Q.; Ding, H.H.; Sun, L.Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, Z.; Yang, K.W. Hydroxamate and Thiosemicarbazone: Two Highly Promising Scaffolds for the Development of SARS-CoV-2 Antivirals. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 124, 105799. [CrossRef]

- Atasever-Arslan, B.; Kaya, B.; Şahin, O.; Ülküseven, B. A Square Planar Cobalt(II)-Thiosemicarbazone Complex. Synthesis, Characterization, Antiviral and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Huang, K.; Pan, W.; Wu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Ma, L.; Gou, Y. Thiosemicarbazone Mixed-Valence Cu(I/II) Complex against Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells through Multiple Pathways Involving Cuproptosis. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9091–9103. [CrossRef]

- Cebotari, D.; Calancea, S.; Garbuz, O.; Balan, G.; Marrot, J.; Shova, S.; Guérineau, V.; Touboul, D.; Tsapkov, V.; Gulea, A.; et al. Synthesis, Structure and Biological Properties of a Series of Dicopper(Bis-Thiosemicarbazone) Complexes. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 12043–12053. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, L.; Leach, C.; Williams, A.; Lighter, B.; Heiden, Z.; Roll, M.F.; Moberly, J.G.; Cornell, K.A.; Waynant, K. V. Binding Mechanisms and Therapeutic Activity of Heterocyclic Substituted Arylazothioformamide Ligands and Their Cu(I) Coordination Complexes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37141–37154. [CrossRef]

- Matsa, R.; Makam, P.; Kaushik, M.; Hoti, S.L.; Kannan, T. Thiosemicarbazone Derivatives: Design, Synthesis and in Vitro Antimalarial Activity Studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 137, 104986. [CrossRef]

- Savir, S.; Liew, J.W.K.; Vythilingam, I.; Lim, Y.A.L.; Tan, C.H.; Sim, K.S.; Lee, V.S.; Maah, M.J.; Tan, K.W. Nickel(II) Complexes with Polyhydroxybenzaldehyde and O,N,S Tridentate Thiosemicarbazone Ligands: Synthesis, Cytotoxicity, Antimalarial Activity, and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1242, 130815. [CrossRef]

- Subhashree, G.R.; Haribabu, J.; Saranya, S.; Yuvaraj, P.; Anantha Krishnan, D.; Karvembu, R.; Gayathri, D. In Vitro Antioxidant, Antiinflammatory and in Silico Molecular Docking Studies of Thiosemicarbazones. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1145, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.A.; Abdallah, E.M.; Ahmed, S.A.; Rabee, M.M.; Bräse, S. Transition Metal Complexes of Thiosemicarbazides, Thiocarbohydrazides, and Their Corresponding Carbazones with Cu(I), Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Pd(II), and Ag(I)—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Piri, Z.; Moradi-Shoeili, Z.; Assoud, A. New Copper(II) Complex with Bioactive 2–Acetylpyridine-4N-p-Chlorophenylthiosemicarbazone Ligand: Synthesis, X-Ray Structure, and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2017, 84, 122–126. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.A.; Franco, L.L.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Perdigão, G.M.C.; Da Silva, J.G.; Souza-Fagundes, E.M.; Beraldo, H. Neutron Activation of In(III) Complexes with Thiosemicarbazones Leads to the Production of Potential Radiopharmaceuticals for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9041–9050. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Gholam Azad, M.; Suleymanoglu, M.; Harmer, J.R.; Wijesinghe, T.P.; Richardson, V.; Zhao, X.; Bernhardt, P. V.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, D.R. Isosteric Replacement of Sulfur to Selenium in a Thiosemicarbazone: Promotion of Zn(II) Complex Dissociation and Transmetalation to Augment Anticancer Efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12155–12183. [CrossRef]

- Porte, V.; Milunovic, M.N.M.; Knof, U.; Leischner, T.; Danzl, T.; Kaiser, D.; Gruene, T.; Zalibera, M.; Jelemenska, I.; Bucinsky, L.; et al. Chemical and Redox Noninnocence of Pentane-2,4-Dione Bis(S-Methylisothiosemicarbazone) in Cobalt Complexes and Their Application in Wacker-Type Oxidation. JACS Au 2024, 4, 1166–1183. [CrossRef]

- Milunovic, M.N.M.; Ohui, K.; Besleaga, I.; Petrasheuskaya, T. V.; Dömötör, O.; Enyedy, É.A.; Darvasiova, D.; Rapta, P.; Barbieriková, Z.; Vegh, D.; et al. Copper(II) Complexes with Isomeric Morpholine-Substituted 2-Formylpyridine Thiosemicarbazone Hybrids as Potential Anticancer Drugs Inhibiting Both Ribonucleotide Reductase and Tubulin Polymerization: The Morpholine Position Matters. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9069–9090. [CrossRef]

- Lukmantara, A.Y.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Kumar, N.; Richardson, D.R. Structure-Activity Studies of 4-Phenyl-Substituted 2′-Benzoylpyridine Thiosemicarbazones with Potent and Selective Anti-Tumour Activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6414–6425. [CrossRef]

- Cebotari, D.; Calancea, S.; Garbuz, O.; Balan, G.; Marrot, J.; Shova, S.; Guérineau, V.; Touboul, D.; Tsapkov, V.; Gulea, A.; et al. Synthesis, Structure and Biological Properties of a Series of Dicopper(Bis-Thiosemicarbazone) Complexes. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 12043–12053. [CrossRef]

- Lighvan, Z.M.; Ramezanpour, A.; Pirani, S.; Akbari, A.; Jahromi, M.D.; Kermagoret, A.; Heydari, A. Synthesis of Tetranuclear Cyclopalladated Complex Using Thiosemicarbazone Derivative Ligand: Spectral, Biological and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 139932. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, K.R.; Viana, J.R.; Oliveira Neto, J.G.; Dias, T.G.; Reis, A.S.; Lage, M.R.; da Silva, L.M.; de Sousa, F.F.; dos Santos, A.O. Exploring Thermal Stability, Vibrational Properties, and Biological Assessments of Dichloro(l-Histidine)Copper(II): A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Study. ACS Omega 2024. [CrossRef]

- Beraldo, H.; Nacif, W.F.; West, D.X. Spectral Studies of Semicarbazones Derived from 3- and 4-Formylpyridine and 3- and 4-Acetylpyridine: Crystal and Molecular Structure of 3-Formylpyridine Semicarbazone. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 1847–1854. [CrossRef]

- West, D.X.; Iii, J.J.I.; Kozub, N.M.; Bain, G.A.; Liberta, A.E. Douglas X. West*, Jack J. Ingram III, Nicole M. Kozub, Gordon A. Bain and Anthony E. Liberta Department of Chemistry, Illinois State University, Normal, IL 67690, USA. 1996, 218, 213–214.

- Ketcham, K.A.; Swearingen, J.K.; Castieiras, A.; Garcia, I.; Bermejo, E.; West, D.X. Iron(III), Cobalt(II,III), Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes of 2-Pyridineformamide 3-Piperidylthiosemicarbazone. Polyhedron 2001, 20, 3265–3273. [CrossRef]

- Muğlu, H. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, DFT Studies and Antioxidant Activity of New 5-Substituted Isatin/Thiosemicarbazones. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1322, 140406. [CrossRef]

- Arion, V.B. Coordination Chemistry of S-Substituted Isothiosemicarbazides and Isothiosemicarbazones. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 387, 348–397. [CrossRef]

- Farzaliyeva, A.; Şenol, H.; Taslimi, P.; Çakır, F.; Farzaliyev, V.; Sadeghian, N.; Mamedov, I.; Sujayev, A.; Maharramov, A.; Alwasel, S.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Studies of Acetophenone-Based Novel Chalcone, Semicarbazone, Thiosemicarbazone and Indolone Derivatives: Structure-Activity Relationship, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics, and Kinetic Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 140197. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Zhang, J.; Honbo, N.; Karliner, J.S. Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115, 155–162. [CrossRef]

- Reszka, K.J.; Britigan, B.E. Doxorubicin Inhibits Oxidation of 2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonate) (ABTS) by a Lactoperoxidase/H2O2 System by Reacting with ABTS-Derived Radical. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 466, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Kruidering, M.; Van De Water, B.; De Heer, E.; Mulder, G.J.; Nagelkerke, J.F. Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Porcine Proximal Tubular Cells: Mitochondrial Dysfunction by Inhibition of Complexes I to IV of the Respiratory Chain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 280.

- Zhang, J.G.; Lindup, W.E. Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity: Decreases in Mitochondrial Protein Sulphydryl Concentration and Calcium Uptake by Mitochondria from Rat Renal Cortical Slices. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 47, 1127–1135. [CrossRef]

- Kaiafa, G.D.; Saouli, Z.; Diamantidis, M.D.; Kontoninas, Z.; Voulgaridou, V.; Raptaki, M.; Arampatzi, S.; Chatzidimitriou, M.; Perifanis, V. Copper Levels in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 23, 738–741. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Kleer, C.G.; Van Golen, K.L.; Irani, J.; Bottema, K.M.; Bias, C.; De Carvalho, M.; Mesri, E.A.; Robins, D.M.; Dick, R.D.; et al. Copper Deficiency Induced by Tetrathiomolybdate Suppresses Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4854–4859.

- Garbuz, O.; Graur, V.; Graur, I.; Railean, N.; Toderas, I.; Pahontu, E.; Ceban, I.; Jinga, V.; Istrati, D.; Ceban, E.; et al. Biological Activity of Copper(II) Complex (2-((2-(Prop-2-En-1-Ylcarbamothioyl)Hydrazinylidene)Methyl)Phenolato)-Chloro-Copper(II) Monohydrate. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Ther. 2024, 8, 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Garbuz O., Gudumac V., Toderas I., Gulea A. Antioxidant properties of synthetic compounds and natural products. Action mechanisms. Monograph. Chisinau, 2023; ISBN 978-9975-62-516-6.

- Fujikawa, F.; Hirai, K.; Naito, M.; Tsukuma, S. Studies on Chemotherapeutics for Micobacterium Tuberculosis. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity on Micobucterium Tuberculosis of Pyridinealdehyde Thiosemicarbazones. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 1959, 79, 1231–1234. [CrossRef]

- Gaber, A.; Refat, M.S.; Belal, A.A.M.; El-deen, I.M.; Hassan, N.; Zakaria, R.; Alhomrani, M.; Alamri, A.S.; Alsanie, W.F.; Saied, E.M. Biological Activity : Antimicrobial and Molecular Docking Study. 2021, 26, 1–18.

- Joseph, M.; Sreekanth, A.; Suni, V.; Kurup, M.R.P. Spectral Characterization of Iron(III) Complexes of 2-Benzoylpyridine N(4)-Substituted Thiosemicarbazones. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006, 64, 637–641. [CrossRef]

- Touchstone, J.C. Thin-Layer Chromatographic Procedures for Lipid Separation. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1995, 671, 169–195. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX . Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. urn:issn:2053-2296 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0 – New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. oflmmunological Methods 1983, 65, 55–63.

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Graur, V.; Chumakov, Y.; Garbuz, O.; Hureau, C.; Tsapkov, V.; Gulea, A. Synthesis, Structure, and Biologic Activity of Some Copper, Nickel, Cobalt, and Zinc Complexes with 2-Formylpyridine N 4 -Allylthiosemicarbazone. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Compound |

MDCK | BxPc-3 | RD | HeLa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50, µM | IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | |

| DOXO | 10.8 | 6 | 1.8 | 16.2 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 1.7 |

| CDDP | 1.5 | 11.2 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 30.9 | 0.04 |

| HL | 100 | 100 | 1 | 1.1 | 90.9 | 8.3 | 12.0 |

| HL1 | 10.1 | 0.1 | 101 | 100 | 0.1 | 81.2 | 0.1 |

| HL2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| HL3 | 100 | 2.1 | 48 | 0.5 | 200 | 100 | 1.0 |

| HL4 | 14.9 | 0.1 | 149 | 11.6 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 2.6 |

| HL5 | 100 | 3.2 | 31 | 0.5 | 200 | 100 | 1.0 |

| [Cu(L1)Cl] (C1) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| [Cu(L1)NO3] (C2) | 0.6 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.1 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| [Cu(L2)NO3] (C4) | 1.3 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.1 | 13.0 |

| [Cu(L3)Cl] (C5) | 26.6 | 9.4 | 3 | 19.7 | 1.4 | 26.1 | 1.0 |

| [Cu(L3)NO3] (C6) | 2.1 | 0.11 | 19 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| [Cu(L4)NO3] (C7) | 0.9 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 9.0 |

| [Cu(L4)Cl] (C8) | 1.1 | 0.1 | 11 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 11.0 |

| [Cu(L5)Cl] (C9) | 13.1 | 0.1 | 131 | 0.2 | 65.5 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| [Cu(L5)NO3] (C10) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 2.9 |

| Compound |

HL-60 | LNCaP | MCF-7 | HepG-2 | K-562 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | IC50, µM | SI | |

| DOXO | 1 | 11 | 1,1 | 0,1 | 14,0 | 0,8 | 2,8 | 3,9 | 0,4 | 27 |

| HL | 0,04 | 2500 | 43,9 | 0,4 | 100 | 1,0 | 100 | 1,0 | 100 | 1,0 |

| HL1 | 0,04 | 253 | 100 | 9,9 | 10 | 1,0 | 0,8 | 12,6 | 10 | 1,0 |

| HL2 | 0,01 | 40 | 0,9 | 2,3 | 3,5 | 0,1 | 0,6 | 0,7 | 0,9 | 0,4 |

| HL3 | 0,01 | 10000 | 100 | 1,0 | 100 | 1,0 | 52 | 1,9 | 10 | 10 |

| HL4 | 0,06 | 248 | 100 | 6,7 | 55 | 0,3 | 3,1 | 4,8 | 16 | 0,9 |

| HL5 | 0,02 | 5000 | 8,07 | 0,1 | 5,2 | 19,2 | 0,3 | 333,3 | 0,1 | 1000 |

| [Cu(L1)Cl] (C1) | 35 | 0,01 | 45 | 150 | 100 | 0,003 | 68 | 0,04 | 64 | 0,005 |

| [Cu(L1)NO3] (C2) | 0,03 | 20 | 0,8 | 1,3 | 0,1 | 6,0 | 0,4 | 1,5 | 0,5 | 1,2 |

| [Cu(L3)NO3] (C6) | 0,03 | 70 | 0,3 | 0,1 | 0,6 | 3,5 | 0,6 | 3,5 | 0,03 | 70 |

| [Cu(L5)Cl] (C9) | 0,2 | 66 | 10 | 0,8 | 9,4 | 1,4 | 14 | 0,9 | 19 | 0,7 |

| [Cu(L5)NO3] (C10) | 10 | 0,02 | 1 | 5,0 | 0,1 | 2,0 | 16 | 0,01 | 10 | 0,02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).