II. Materials and Methods

The plant material used in this study includes Herniaria hirsuta and Plantago albicans, which were harvested from the Tessala region, located approximately 15 km from the city of Sidi Bel Abbès in western Algeria. The Tessala forest spans the area between Djebel Sbaa Chioukh, Ain Temouchent, and Tlemcen to the west, and Benichougrane in Mascara to the east. Known for its rich flora, this region provides diverse medicinal plants traditionally used for various therapeutic applications.

The harvested plants were initially identified using standard botanical methods, including macroscopic and microscopic examinations of the powdered material. Microscopic analysis was conducted using Gazet’s reagent to reveal specific cellular structures and elements characteristic of each plant species, such as trichomes. This microscopic examination enables identification of the different plant materials within the powder, assessment of powder quality and purity, and detection of potential adulterants or contaminants. A small quantity of plant powder was mounted on a microscope slide using glycerin or Canada balsam as a mounting fluid, covered with a coverslip, and observed under a microscope. Characteristic cellular structures were noted, including the thick cell walls and small cell size of Herniaria hirsuta and the large, thin-walled cells of Plantago albicans.

Four kidney stones were collected for the dissolution test from the Urology Department of the University Hospital of Oran (CHU-Oran). These stones were washed and stored in physiological saline solution until further processing. Before conducting the dissolution test, each stone was rinsed with distilled water and air-dried on filter paper for two hours. The morphological characteristics, size, and weight of each stone were recorded, providing a detailed identity profile for each sample.

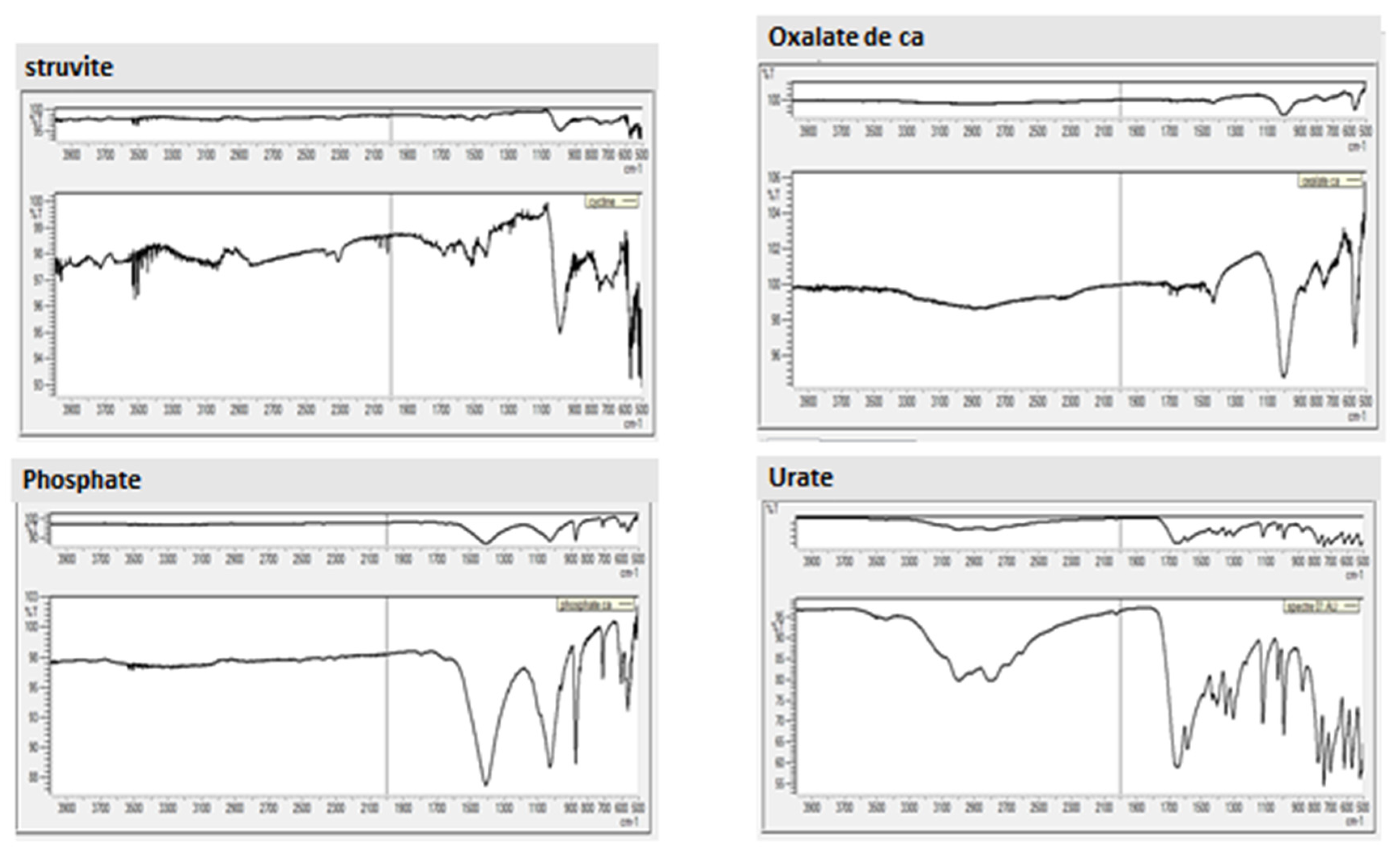

To characterize the composition of the kidney stones, Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrophotometry was performed using a SHIMADZU® FTIR-IRAffinity-1S spectrophotometer, with a spectral range from 4000 to 500 cm⁻¹. The analysis was carried out using the attenuated total reflection (ATR) technique, which allows for direct examination of crystalline and non-crystalline substances in the stones. This spectroscopic approach enables precise identification and quantification of the various crystalline species and molecular components present, preserving the structural integrity of the samples for a thorough morpho-constitutional analysis.[

8]

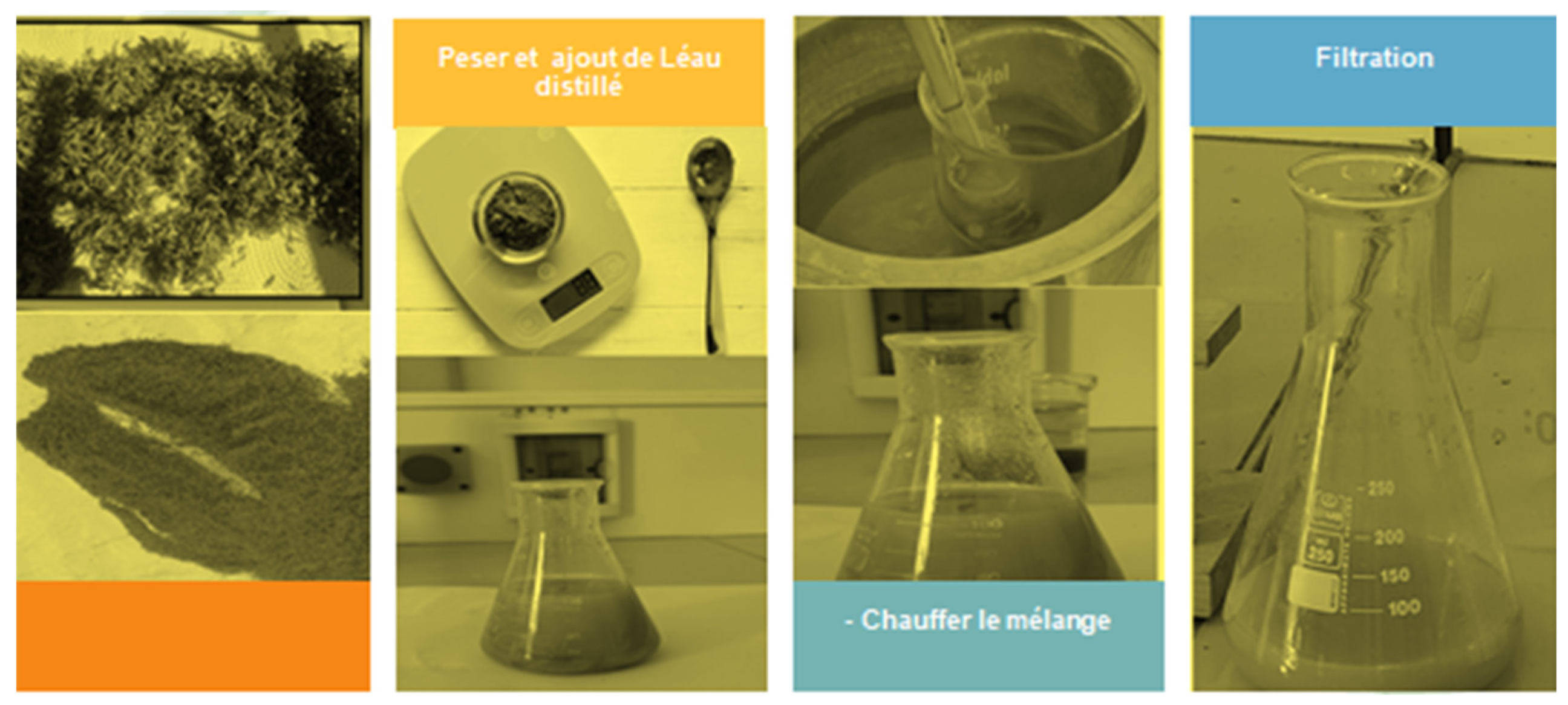

The extraction of bioactive compounds from the plant material was performed by decoction, a process suitable for extracting water-soluble compounds like tannins, flavonoids, and mucilages. Decoction was chosen for its efficiency in obtaining concentrated extracts and its stability over time, making it ideal for further analysis and testing. The dried and pulverized plant material was boiled in water to release the active compounds, yielding a solution ready for testing.

The analysis of active secondary metabolites was conducted through phytochemical screening, which involves the qualitative detection of key bioactive compounds. This analysis focused on identifying the presence of polyphenols, including flavonoids, tannins, coumarins also saponin terpen according to trease and evans [

9]

The dissolution activity of the plant extracts on kidney stones was evaluated using four stones. Each stone was measured for morphology, size, and weight before testing. Following the preparation of the plant decoctions, the stones were submerged in the extract solutions, and dissolution was monitored over time.

After a one-week incubation period, the kidney stones were carefully retrieved using filter paper and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water. The washed stones were then placed in a glass container and dried at 40°C for 16 hours to ensure complete dehydration. Following the drying process, each stone was weighed using a precision balance to obtain an accurate measurement of its mass. This protocol enables the assessment of any mass reduction as an indicator of the dissolution effectiveness of the tested plant extracts. This method assesses the antilithiasic potential of the plant extracts based on their ability to break down and reduce the mass of kidney stones.[

10]

The dissolution activity of urinary stones by each plant extract was assessed by calculating the dissolution rate of the stones after exposure to the experimental medium. This was achieved by comparing the residual weight of the stones after incubation with their initial weight prior to treatment with the extract. The percentage of dissolution was calculated using the following formula:

where

A% represents the dissolution rate of the stone, and

W initial and

W final are the weights of the stone before and after incubation with each plant extract, respectively. This formula provides a quantitative measure of the efficacy of each extract in reducing the stone mass.

III. Results

Figure 1.

description of two species.

Figure 1.

description of two species.

The microscopic examination of the powdered aerial parts of Herniaria hirsuta and Plantago albicans revealed distinct morphological characteristics essential for identification and quality assessment.

- -

Herniaria hirsuta Powder

Under 400x magnification, the powder from Herniaria hirsuta showed:

Epidermal fragments with distinctly sinuous-walled cells, contributing to its structural integrity,

Thick-walled, small cells containing rosette-shaped crystals,

A smooth cuticle layer,

Anomocytic stomata, indicative of characteristic stomatal organization in this species.

These specific features aid in distinguishing Herniaria hirsuta and serve as markers for its quality control.

Figure 2.

Microscopic Analysis of Powdered Herniaria hirsuta.

Figure 2.

Microscopic Analysis of Powdered Herniaria hirsuta.

- -

Plantago albicans Powder

Microscopic evaluation of Plantago albicans powder at 400x magnification highlighted:

Epidermal fragments with sinuous-walled cells similar in structure,

Thin-walled, large cells with mucilage presence, which aligns with the plant's functional morphology,

A smooth cuticle layer,

Anomocytic stomata,

Uniserial trichomes, which serve as an identifying trait of Plantago albicans.

These microscopic characteristics collectively support the reliable identification and purity assessment of Plantago albicans.

Figure 4.

Extraction process.

Figure 4.

Extraction process.

- 3.

Screening Results:

The phytochemical screening revealed the presence of flavonoids, tannins, and coumarins in both plant extracts, while saponins were notably dominant in the extract of

Herniaria hirsuta. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

The foam test indicated a significant presence of saponins in Herniaria hirsuta, as evidenced by the formation of foam in all 10 tubes, with foam heights ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 cm. This resulted in a saponification index (Im) of 200. Conversely, Plantago albicans exhibited a low level of saponins, as reflected by the foam heights in the 10 tubes, which ranged from 0.2 to 0.9 cm, indicating a low saponification index (Im < 100).

The results of the morphological typing and calcination tests of the analyzed kidney stones are presented in

Table 2.

The results of the FT-IR (ATR Diamond) analysis for these five calculi are presented in

Figure 5 and Figure 6

This spectrum displays a broad band between 2300 and 3800 cm⁻¹, along with multiple medium-intensity peaks within the 570–1670 cm⁻¹ range and another prominent peak at 570 cm⁻¹ in the 1005–570 cm⁻¹ region. Comparison with reference spectra (Appendix 1,

Figure 01) confirms similarity to the reference spectrum for STRUVITE (hexahydrated ammonium magnesium phosphate).

This spectrum features two primary bands: one with a single maximum-intensity peak at 996 cm⁻¹, and another with dual peaks at 570 cm⁻¹ and 500 cm⁻¹. Additionally, there are broad bands with a maximum intensity at 3010 cm⁻¹ and lower-intensity peaks between 1410 and 1680 cm⁻¹. These findings closely match the reference spectrum for cystine.

The spectrum displays two major bands: a single peak at 1010 cm⁻¹ and a second at 570 cm⁻¹. Broader bands appear with maximum intensity at 2878 cm⁻¹ and additional lower-intensity peaks between 1430 and 1680 cm⁻¹. Comparison with the reference spectrum confirms similarity to calcium oxalate.

This spectrum includes a broad band from 2600 to 3010 cm⁻¹ and several medium-intensity peaks within the 520–1660 cm⁻¹ range. Another notable peak appears at 740 cm⁻¹ within the 740–520 cm⁻¹ range. This spectrum matches the reference spectrum for uric acid dihydrate crystals

The spectrum displays four primary bands with peak intensities at 560 cm⁻¹, 870 cm⁻¹, 1030 cm⁻¹, and 1410 cm⁻¹. A broad band also appears between 3460 and 3580 cm⁻¹ with lower intensities. Comparison with reference spectra (

Figure 5) shows similarity to weddellite and carbapatite, indicating a type Ia (Whewellite) + type IVa (Carbapatite) composition. Thus, this kidney stone consists of calcium oxalate with calcium and/or magnesium phosphate.

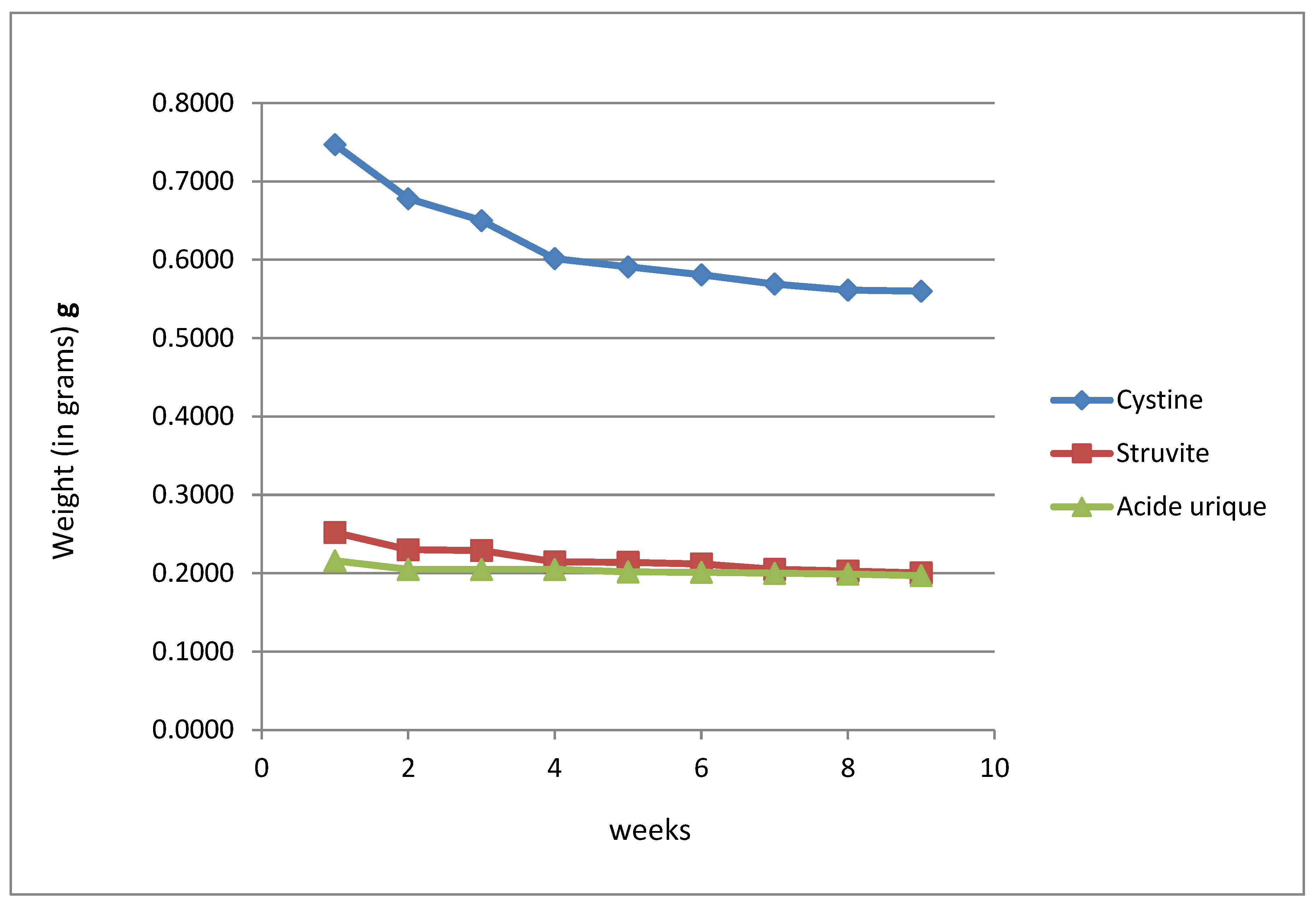

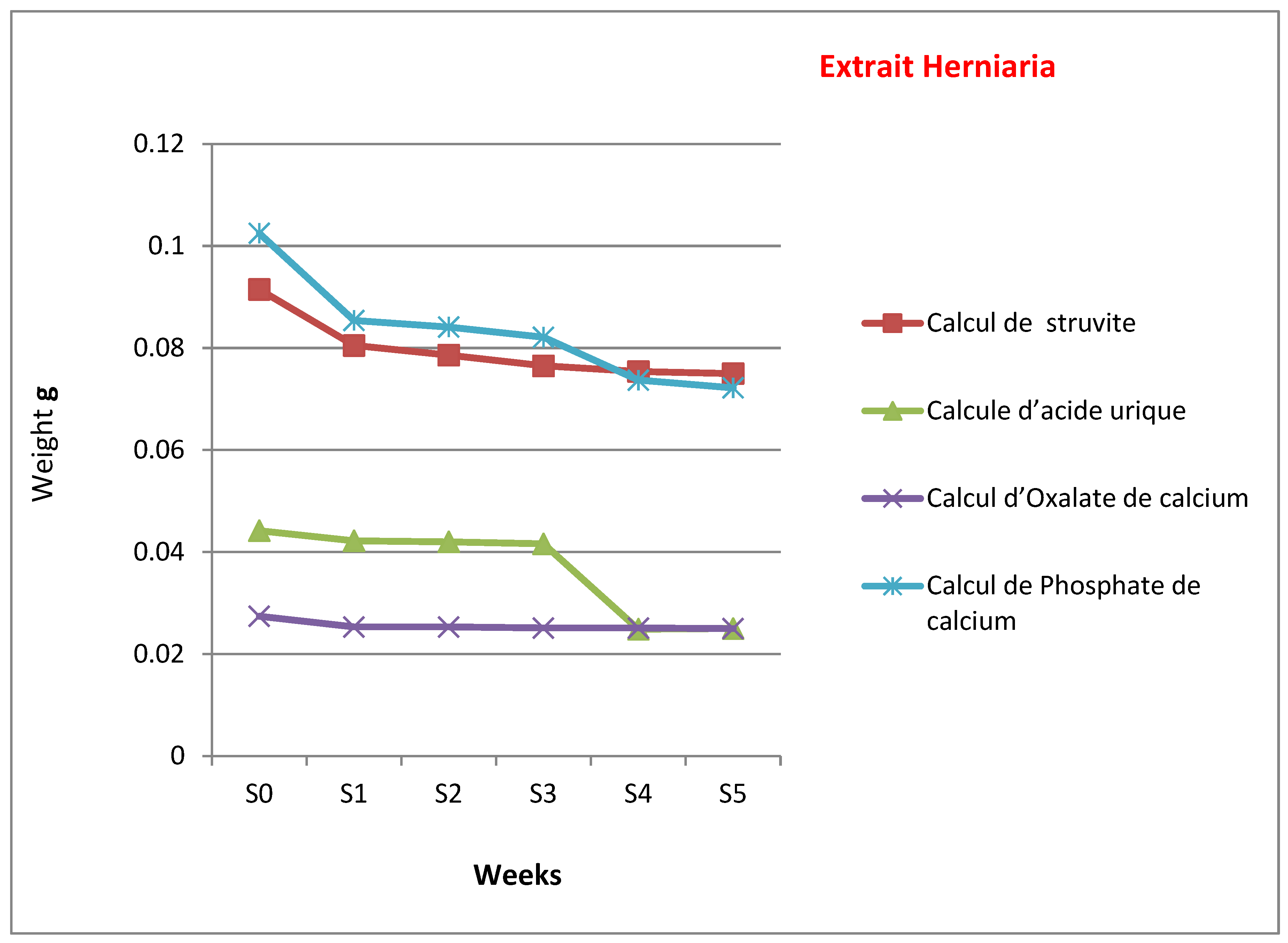

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the weight changes in five types of kidney stones when exposed to alcoholic extracts from

Plantago albicans (for three stone types: cystine, struvite, and uric acid) and

Herniaria hirsuta (for five stone types: cystine, struvite, uric acid, calcium oxalate, and calcium phosphate). Control samples were incubated in physiological saline for each stone type. Stone weights were measured with a precision electronic scale (in grams).

The weight evolution graphs demonstrate a significant reduction in the weight of the cystine stone in the alcoholic extract of Plantago albicans, with an initial weight of 0.74 g reduced to 0.56 g over the eight-week experiment, accompanied by a decrease in size from 1.20 x 0.46 cm to 0.90 x 0.40 cm.

Figure 7.

Weight evolution of three stones in Plantago albicans extract over eight weeks (in grams).

Figure 7.

Weight evolution of three stones in Plantago albicans extract over eight weeks (in grams).

Figure 8.

Weight evolution of five stones over four weeks (in grams).

Figure 8.

Weight evolution of five stones over four weeks (in grams).

The current study demonstrates a significant litholytic effect of Herniaria hirsuta extract, particularly on cystine, uric acid, and, to a lesser extent, calcium oxalate stones. These findings corroborate previous studies that report the potential of various medicinal plants in the management and dissolution of urinary stones. For instance, Crescenti et al. observed an antiurolithiasic effect using a combination of Herniaria glabra, Agropyron repens, Equisetum arvense, and Sambucus nigra. Their findings, similar to ours, highlighted Herniaria species as effective in the dissolution of certain kidney stone types, particularly those soluble in aqueous solutions.[

11]

Moreover, Hannache et al. demonstrated that certain medicinal plant extracts can effectively dissolve cystine stones in vitro. This aligns closely with our observations of Herniaria hirsuta’s strong effect on cystine stones, supporting its traditional use for urinary health. Additionally, Meiouet et al. reported that multiple medicinal plants show litholytic activity against cystine stones, underscoring Herniaria hirsuta’s promising role within this group.[

6,

12]

The high saponoside content in Herniaria hirsuta, confirmed by a saponification index (Im) of 200, may be a crucial factor in its litholytic action. Vincken et al noted that oleanane-type saponins—prevalent in the Caryophyllaceae family—contribute to foaming properties that may facilitate the breakdown of stone components. In contrast, Plantago albicans, with a lower saponification index (<100), exhibited only moderate activity, highlighting the importance of saponosides in stone dissolution. This difference could explain why Herniaria hirsuta demonstrates greater efficacy in vitro. [

13,

14]

In addition to their saponoside content, both plants’ bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, tannins, and coumarins, may contribute to their antilithiasic activity. These metabolites are known for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which may mitigate factors that exacerbate kidney stone formation. Comparative studies suggest that the synergistic effects of these compounds, particularly in Herniaria hirsuta, enhance its litholytic potential.[

15,

16]

For struvite stones incubated in Plantago albicans methanolic extract and uric acid stones dissolved in the same extract, a weight reduction of 0.05 g and 0.019 g was noted during the first week, after which weight stabilized over the following seven weeks. The uric acid stone showed a minimal weight reduction over eight weeks, suggesting that Plantago albicans has a stronger dissolving effect on cystine stones compared to uric acid stones.

Conversely, Herniaria hirsuta exhibited a more potent dissolving effect on cystine and uric acid stones, but no effect on calcium oxalate stones. Therefore, Plantago albicans appears more effective on cystine stones than uric acid stones, while Herniaria hirsuta showed limited efficacy on calcium phosphate and struvite stones and no effect on calcium oxalate stones.

The average mass loss of cystine stones in Plantago albicans extract was significant over eight weeks, at 0.17 g (74.96%). For uric acid stones, a 0.05 g mass loss (83.33%) was observed in the first week. In contrast, average mass losses in Herniaria hirsuta extract were 34.14% for cystine stones, 56.56% for uric acid stones, and 70.43% for calcium phosphate stones, with negligible mass loss observed for struvite and calcium oxalate stones throughout the experiment.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 depict the dissolution rate of stones in aqueous extracts of

Plantago albicans L. and

Herniaria hirsuta L. over the eight-week experiment.

The mass loss results correlated strongly with the dissolution rates observed for

Plantago albicans extract. For cystine stones, a high dissolution rate (25.04%) was recorded. Struvite stones showed a dissolution rate of 20.44%, while uric acid stones had a low rate of 8.8% over the eight weeks. This suggests that

Plantago albicans methanolic extract has a greater capacity for dissolving cystine stones, with negligible effect on uric acid stones. In contrast,

Herniaria hirsuta demonstrated a remarkably high dissolution rate for cystine stones (65.86%) and uric acid stones (43.44%) compared to struvite stones (18.04%). This greater effect on cystine and uric acid stones may be attributed to the higher saponoside content in

Herniaria hirsuta compared to

Plantago albicans.The Saponin test results reveal a notably high presence of saponosides in

Herniaria hirsuta, with a saponification index (Im) of 200, indicating a strong foaming capability. In contrast,

Plantago albicans exhibits a much lower saponoside content, evidenced by the modest moss height in the 10 test tubes (0.2–0.9 cm), and a saponification index below 100. [

17,

18]

These findings align with those of Vincken et al., who identified oleanane-type saponins as the predominant saponin class in the Caryophyllaceae family, to which

Herniaria belongs. This high saponoside content in

Herniaria hirsuta contributes to its dissolution efficacy in vitro by facilitating the formation of foaming solutions that interact with the crystalline components of water-soluble kidney stones [

10,

13]. Consequently,

Herniaria hirsuta demonstrates a stronger potential as a natural litholytic agent compared to

Plantago albicans, due to its elevated saponoside levels.

This study underscores the efficacy of Herniaria hirsuta as a promising natural agent in dissolving cystine and uric acid kidney stones, with moderate activity observed for calcium oxalate stones. The plant’s rich saponoside content is likely central to its dissolution capabilities, reinforcing findings from prior studies on the Caryophyllaceae family’s antilithiasic activity.

In comparison, Plantago albicans demonstrated a weaker effect, suggesting it may be less effective alone but still potentially beneficial as part of a combined treatment with other litholytic agents. The study’s strength lies in its detailed comparative analysis of two plants with different saponoside profiles and in demonstrating a potential application of Herniaria hirsuta in alternative therapies for urolithiasis.