1. Introduction

Foodborne diseases (FBD) represent a significant public health challenge globally, with implications in food safety, the economy, and social development [

1,

2]. While the human body naturally harbors a variety of microorganisms, it remains vulnerable to pathogens capable of causing foodborne diseases and intoxication [

3,

4]. Such diseases can lead to acute symptoms like diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain, but can also include severe complications such as neurological damage, organ failure, and in extreme cases, death [

5,

6]. The economic and social repercussions are equally profound, imposing both direct and indirect financial costs on individuals and businesses. FBD strain public healthcare systems, impacting labor productivity by triggering an increase on the amount of sick days taken by employees, while encompassing substantial economic losses due to healthcare costs [

5,

7]. When it comes to businesses and food brands, bacterial infections related to food can also create a negative impact following an outbreak. For instance, the State of Georgia lost almost

$14 million dollars on its tomato industry in 2008, due to a

Salmonella saintpaul outbreak that was mistakenly linked to tomatoes [

8].

Additionally, these infections can affect vulnerable populations, such as infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, exacerbating the social impact and underscoring the need for strengthened food safety measures, particularly in regions where regulations may be less rigorous [

9,

10]. Authors previously reported several cases of infections with

Salmonella enterica (SE), where 17% patients stated having an underlying illness such as sickle cell anemia, septicemia, HIV, and multiple myeloma before onset of bacterial infection. It was also mentioned that young children are more susceptible to Salmonella infection at lower inoculum than adults, and the ones under five were also shown to be at greater risk for SE infection from the consumption of raw or undercooked eggs [

11].

Addressing these issues requires understanding the scope of the problem to develop effective public health measures targeting food safety. The burden of these diseases is reflected in the numbers of infections reported annually worldwide, where studies have identified the presence of pathogens such

Escherichia, Arcobacter, Listeria, Staphylococcus, Shigella, Campylobacter, and

Pseudomonas in various food products [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. In general, diarrheal diseases make up approximately 95% of cases of food illnesses in Central America and more than 50% of those reported internationally, while the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that unsafe food causes about 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths globally each year, with children under five being most affected [

17,

18]. For instance,

Campylobacter spp. is responsible for approximately 500 million infections each year, while

Salmonella spp. are estimated to cause over 90 million diarrhea-associated illnesses annually, with 85% of these cases being food-related [

19].

In order to prevent illnesses and outbreaks, continuous pathogen monitoring and detection must be supported by education in possible causes of foodborne diseases, sanitation, and good manufacturing practices [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Despite the developing surveillance system for FBD, and guidelines provided by Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in food handling practices for Central America and the Caribbean (CAC), it was evidenced in a survey that a systemic lack of understanding in national regulations was still present among food safety professionals in government, academia, and private sectors in the region [

24]. In the same way, several researchers state a lack of resources and ability to collect and analyze outbreaks information and detection of pathogens, due to the existence of a significant technical gap in third world countries, regarding data interpretation using bioinformatics [

25]. Other studies state lack of economic support in this region, to carry out investigations regarding FBD [

8,

26]. This results, subsequently, highlight the need for improved documentation of diseases related to food, their epidemiological importance and risk analysis practices in CAC [

7,

24].

As stated previously, knowledge on the incidence and strategies of surveillance and detection of bacterial foodborne diseases in the region is crucial for the management and prevention of possible outbreaks. With little to no documentation found in the matter of FBD in countries belonging to CAC, and therefore, difficulties to find summarized research on the subject, the need for literature reviews is highlighted. For this reason, this document aims to address critical knowledge gaps by analyzing FBD in Central America and the Caribbean over the past two decades. By compiling recent documentation, we intend to assess the literature on food-related bacterial illnesses and their prevalence in countries from Central America and The Caribbean, the existing challenges regarding their management and surveillance, along with current strategies to prevent and control outbreaks in the region. For this objective, we will assess the primary bacterial pathogens, their sources, detection methods, and affected populations. On this manner, we intend to underscore the need for enhanced surveillance, improved documentation, and enhanced food safety education to prevent future outbreaks, identifying opportunities for further research in the process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

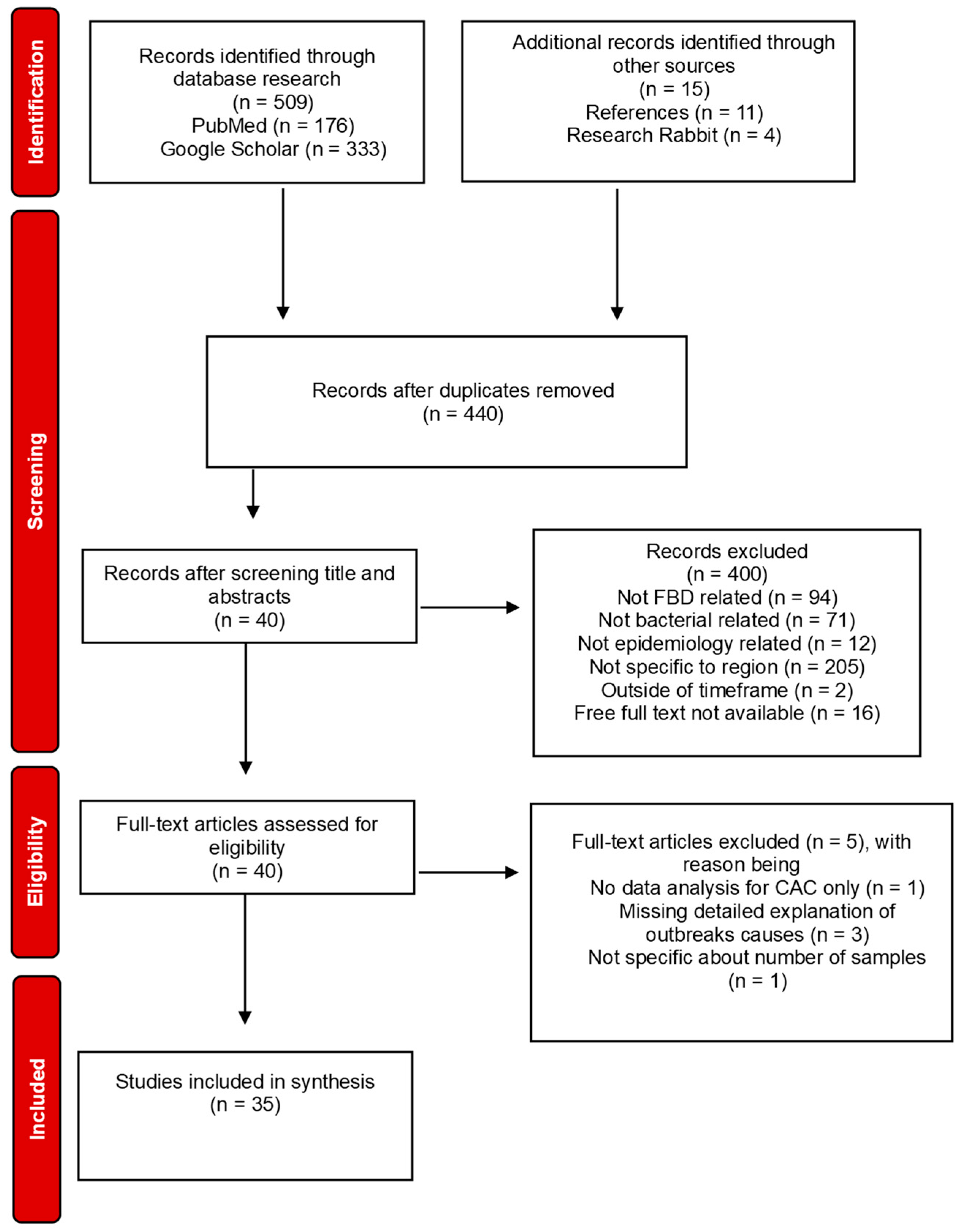

This systematic review was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [

27]. The purpose of the search was to identify relevant studies on the incidence of bacterial foodborne diseases in Central America and the Caribbean, along with possible seasonal patterns, its primary causative agents, risk factors, challenges in surveillance, and strategies on the prevention and management of outbreaks.

2.2. Search Strategy

PubMed was used as the primary database to locate relevant investigations, while Google Scholar was utilized as a secondary one to find records that could possibly not be found in the previous platform. Search settings prioritized articles published between January 1st 2000 and September 15th 2024. Clinical Trials, Meta-Analysis, Randomized Controlled Trials, Surveys, Reviews and Systematic Reviews were included to ensure thorough research. To ensure comprehensive coverage, a combination of general and specific keywords and phrases was employed, using Boolean research method.

2.3. Identification of Studies

The literature review was conducted to identify relevant studies on bacterial foodborne diseases in Central America and the Caribbean. Clinical Trials, Meta-Analysis, Randomized Controlled Trials, Surveys, Reviews and Systematic Reviews were included to ensure thorough research.

To ensure comprehensive coverage, a combination of general and specific keywords and phrases was employed, using Boolean research method. As shown in

Table 1, the terms were divided into blocks, each one related to a specific topic: (1) Foodborne Diseases, (2) Microbiological terms, (3) Prevalence and Epidemiology, (4) Challenges in controlling FBD, (5) Control Systems & Public Health, (6) Strategies to prevent and control FBD, (7) Geographic Scope. Then, in order to find documentation about the scope of the review, the blocks were combined using Boolean Operator “AND” in between each block, and “OR” in between each term belonging to the same block.

For PubMed, three searches were conducted; for the purpose of finding documentation about the prevalence and epidemiology of FBD in CAC, blocks 1, 2, 3 and 7 were combined; and to find out the main challenges regarding the control of this burden in the region, a combination of the blocks 1, 2, 4, 5 and 7 was used. While on the lookout for strategies for its prevention and management, a search using blocks 1, 5, 6 and 7 was conducted.

On the other hand, a combination of the search entries belonging to blocks 1, 2, 3 and 7 was used on Google Scholar to find any possible record that was not retrieved from the primary database used on this review.

2.4. Selection Process and Quality Assessment

In the screening process, we first reviewed the titles to check if selected articles were appropriate. Then all abstracts were screened, and if relevant, the full text article was evaluated.

Studies regarding the incidence of bacterial foodborne diseases, with seasonal patterns, primary causative agents, risk factors, challenges in surveillance, and strategies on prevention and management of outbreaks in Central America and the Caribbean were included. Reference lists in included studies and reviews were also contemplated, ensuring that the review captured both current and foundational insights of the topics.

On the other hand, literature regarding parasitic, viral, fungal, animal or plants related FBD were discarded, as the scope of the review was FBD caused by bacteria. In the same manner, studies reporting on the incidence of food-related illnesses of countries outside the region were also excluded. We excluded duplicate publications, and articles without available abstracts or full texts.

The articles were categorized into good, medium, and poor quality. Good-quality articles were those with an unbiased selection of subjects, scientifically valid methods, and appropriate data analysis, with complete and accurate results. Medium-quality articles recognized and addressed selection bias, had some limitations in data analysis, used clear methods, and produced valid results. Poor-quality articles, which did not acknowledge selection bias, had flawed or incomplete methods, inappropriate data analysis, and incomplete results, were excluded from the study, and no data was extracted from them.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the process of identification, screening, assessment for eligibility and inclusion of articles.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the process of identification, screening, assessment for eligibility and inclusion of articles.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Data of bacterial-related foodborne disease was collected based on the available information in current literature, including year of outbreak, pathogen, food incriminated, reason for infection, number of cases, number of hospitalizations, deaths, and location. The variables were descriptively compared using mainly figures and tables.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

During the manual research through PubMed and Google Scholar, 176 and 333 records were identified, respectively. Research Rabbit was used as an artificial intelligence to discover more articles that we could have missed in the manual search, adding 4 more records with full-text available. Additionally, 11 papers were also discovered through the references of articles in which the full text was screened. After duplicates were removed using Mendeley Reference Manager, the total of articles available for screening was 440. The latest were evaluated based on their titles and abstracts, following the selection criteria mentioned above, resulting in 400 excluded articles and 40 full-text papers ready for assessment of eligibility. After revision of the full texts, 5 of them were excluded based on the quality assessment created regarding the scope of the review. Subsequent to eligibility assessment and exclusion of full-text articles, we were left with 35 included papers that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and could be used for data extraction and synthesis.

3.2. Data Extraction

Data of bacterial-related foodborne disease included, if available in each study, the responsible pathogens, source of food incriminated, reason for infection, number of cases, number of hospitalizations, deaths, and location. Additionally, information regarding the current methods for detection and isolation of serovars was included. Furthermore, the implemented surveillance systems, existing limitations and knowledge gaps in the previous topics were also retrieved from the included literature and discussed in this review.

3.3. Foodborne Disease Caused by Bacteria in CAC

3.3.1. Salmonella spp.

A series of studies conducted across the Caribbean region investigated the prevalence and serotypes of

Salmonella spp., highlighting significant findings related to both animal reservoirs and food products. In Suriname, 9% of pig farms tested positive, with serovars such as

S. Ohio and

S. Brandenburg, though no contamination was found in pork samples [

28]. In Grenada, 17% of blue land crabs carried

Salmonella, with

S. Saintpaul,

S. Montevideo, and

S. Newport identified, indicating that crustaceans could act as reservoirs [

29]. In Guatemala,

Salmonella was found in 34.3% of retail chicken carcasses, with

S. Paratyphi B and

S. Heidelberg being prevalent serovars, and higher contamination rates were linked to ambient storage in municipal markets [

30]. In Dominican Republic,

Salmonella enterica was a prominent pathogen reported in travel-related cases. The most common serotype was

S. Enteritidis, with 16% of cases leading to hospitalization [

31,

32,

33]. Similarly, in Jamaica, Bahamas and Costa Rica, Guatemala, El Salvador

S. Enteritidis was the predominant serotype, and for each country, 12%, 19% and 14% of travelers were hospitalized, respectively [

32,

33].

In Trinidad and Tobago (T&T), contamination was reported in 14.2% of dressed chicken, with

S. Javiana prevalent in cottage processors and

S. Kentucky in supermarkets [

34]. Chilled broiler carcasses had a 60% contamination rate, with serovars such as

S. Enteritidis,

S. Javiana, and

S. Infantis [

35]. Another poultry research reported a 6.1% contamination rate in cecal samples, with

S. molade, as the most identified serovar [

36]. Additionally, in broiler farms and hatcheries, 3.5% of samples tested positive, with

S. Westhampton and

S. Kentucky detected in hatcheries [

37]. Likewise, 13% of table eggs tested positive, with

S. Enteritidis accounting for 58.3% of positive samples, indicating trans-ovarian infection in farm-sourced eggs [

38,

39]. Cross-contamination during poultry processing was also significant, with contamination rates of 60% during bleeding and 40% during evisceration [

40,

41].

3.3.2. Escherichia coli

One study in T&T investigating the prevalence of Escherichia coli in table eggs demonstrated that out of 184 samples collected from various sources, including retail outlets and farms, 68 samples (37.0%) tested positive for the bacterium. The highest prevalence was observed in composite egg samples from farms, where 71.7% were positive, followed by samples from malls (41.9%) and other retail outlets (20.6%) [

38]. Furthermore, a study evaluating the occurrence of selected foodborne pathogens in poultry and poultry giblets from small retail processing operations in the same country, found that E. coli was present in 100% of the six fresh chicken carcasses sampled from 16 pluck shops over a six-week period [

41].

3.3.3. Campylobacter spp.

The same investigation evaluating bacterial contamination in table eggs in T&T found that out the 184 samples collected, only two samples (1.1%) tested positive for

Campylobacter coli [

38]. In contrast, a separate investigation about foodborne pathogens in poultry from small retail processing operations reported a high prevalence of

Campylobacter in chicken carcasses, with 89.6% (86/96) of the whole carcasses testing positive [

41].

3.3.4. Shigella spp.

A healthcare facility-based surveillance system in Guatemala, monitored cases of shigellosis from 2007 to 2012. During this period, 5399 stool samples yielded 261 confirmed

Shigella infections. A significant majority (58%) of these cases involved children five years of age, and 57% were female, with

Shigella flexneri (59%) and

Shigella sonnei (36%) being the most frequently isolated serotypes. Environmental factors, such as the warm and rainy season were associated with increased transmission. Social determinants, including overcrowding and low education levels, also compounded the risk of infection [

42].

3.3.5. Staphylococcus spp.

In a study where poultry and giblets from small retail processing operations were examined over a six week period, Staphylococci were detected in 100% of the collected samples, indicating widespread contamination in these retail operations [

41].

3.3.6. Listeria spp.

In Costa Rica, while assessing the prevalence of

L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) meat products, including bologna, sausages, chorizo, salami, queso de cerdo, and mortadella, a total of 190 samples were collected from 70 retail stores.

Listeria spp. was detected in 37.4% of the samples, with a higher prevalence in products cut with a knife (44.2%) compared to those sliced by machine (30.5%). Among the isolates,

L. innocua was found in 32.1% of samples, while

L. monocytogenes was present in only 2.6%. The study highlighted that

L. monocytogenes can proliferate during refrigerated storage of RTE meats, posing a contamination risk during post-cooking processes like slicing and packaging [

43].

3.3.7. Aliarcobacter spp.

Three studies in Costa Rica investigated the prevalence of

Aliarcobacter spp., previously known as

Arcobacter spp., in chicken and vegetables. In one study, 56% of 50 raw chicken breast samples from retail markets tested positive, with

A. butzleri (59%) as the dominant species, followed by

A. cryaerophilus (19%). Multiple strains were detected in the samples, emphasizing the need for standardized protocols, especially for emerging pathogens similar to the latest [

44]. Another research found 17.3% of 150 chicken viscera samples tested positive for

Aliarcobacter spp., with

A. butzleri (66.7%) and

A. cryaerophilus (24.2%) prevalent, along with rare detections of

A. skirrowii (3.1%) [

45].

Contamination was also observed in vegetables, with

Aliarcobacter spp. present in 21.1% of fresh samples and 2.2% of pre-cut vegetables. Arugula showed the highest contamination rate (40%), followed by lettuce (16%) and spinach (13%). Among pre-cut samples, lettuce and arugula both had 3% contamination. Pathogenic species identified included

A. skirrowii and

A. butzleri. The findings highlight a higher contamination risk in fresh vegetables despite processing efforts [

46].

3.3.8. Clostridium difficile

This study investigated the presence of

C. difficile in 200 retail meat samples from Costa Rica, including 67 beef, 66 pork, and 67 poultry samples. A total of four isolates (2%) were identified: one from beef, two from pork, and one from poultry. Identification of the isolates was confirmed through chromatography, biochemical profiling, and detection of the

tpi gene. The study suggests that the presence of

C. difficile in meat may result from contamination with intestinal contents or environmental factors [

47].

Figure 2.

Countries from Central America and the Caribbean reporting bacterial foodborne diseases [

48].

Figure 2.

Countries from Central America and the Caribbean reporting bacterial foodborne diseases [

48].

3.4. Main Challenges in Controlling FBD in CAC

For a bacterial foodborne illness to occur, the pathogen must be present in a sufficient quantity to cause an infection or produce toxins, the food and temperature must support the growth of the pathogen, and the amount of contaminated food ingested must be sufficient to overcome the individual's natural defenses. These conditions, although someway specific, can be met easily without proper handling and comprehension on food safety systems [

49,

50].

The studies conducted in Central America and the Caribbean (CAC) reveal significant challenges in controlling foodborne diseases (FBD) that are crucial for public health and the tourism-dependent economy of the region. A comprehensive survey indicated that many food establishments, particularly smaller hotels, struggle with implementing effective food safety systems, notably the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) framework. Over one-third of the hotels assessed did not employ a team approach to food safety management and lacked documented HACCP plans. Staff members in these establishments displayed a limited understanding of HACCP principles, underscoring a knowledge gap that hinders proper food safety practices [

51]. This situation is exacerbated by a lack of policy and legislation to ensure compliance, especially in smaller properties where adherence to safety measures is often driven more by customer demand than by regulatory requirements [

50].

Inadequate foodborne disease surveillance further complicates the control of FBD in the CAC. Studies reveal a critical shortage of data on the morbidity and mortality associated with foodborne illnesses, primarily because diagnostic testing is typically conducted only during outbreaks. This reliance on outbreak data leads to widespread underreporting of sporadic cases, limiting public health authorities' understanding of the prevalence and sources of pathogens in the food supply [

8]. For instance, while Salmonella has been identified as the most frequently reported pathogen, the variability in reporting across countries creates a fragmented picture of food safety in the region [

29]. Moreover, research on outbreaks and studies regarding identification of bacteria causing FBD in CAC countries are severely lacking, with much of the existing literature being outdated by at least 15 years. This is concerning, as changes in animal genetics, nutrition, and management practices over the years may have affected the exposure potential and susceptibility of different livestock species to pathogens. Studies highlight a significant gap in research regarding pathogens like

Salmonella and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in animals such as goats and sheep, which are often slaughtered in unsanitary conditions [

52]. Researchers have emphasized the existing gaps in data across the region, pointing out that some available information only reflects certain countries rather than the entire area. This discrepancy is particularly evident in the variability of reporting, especially regarding the most commonly identified pathogens [

53]. The lack of economic support for conducting FBD research in CAC is further emphasized by [

8]. These findings make it clear that institutional and governmental funding is essential to improve the documentation of foodborne diseases, understand their epidemiological significance, and enhance risk analysis practices in the region

Emerging pathogens and antimicrobial resistance present additional challenges in ensuring food safety. The identification of Arcobacter species as potential foodborne pathogens raises concerns about hygiene practices in food preparation and handling. The studies indicate that high levels of Arcobacter may signal poor sanitation, which complicates the overall food safety landscape in the region [

44,

45].

To prioritize food safety interventions effectively, it is essential to identify the primary sources of human illness, available mitigation options, and their associated costs. Recent methods for attributing foodborne illnesses include microbiological, epidemiological, expert solicitation, and intervention studies. Epidemiological methods analyze outbreak data to estimate the contributions of various foods to disease. However, this approach assumes that outbreak sources are the same as those causing sporadic illnesses. While summarizing outbreak results can help identify common food vehicles linked to illness, it may overlook more complex food sources [

54].

Table 3.

Main challenges for surveillance of FBD in CAC.

Table 3.

Main challenges for surveillance of FBD in CAC.

| Main challenge |

Description |

References |

| Inadequate FBD surveillance |

Underreporting of foodborne diseases due to limited diagnostic testing during sporadic cases. |

[8] |

| Lack of updated research |

Outdated research on outbreaks and bacteria in food, especially for non-poultry livestock. |

[52] |

| Lack of comprehensive data |

Inconsistent and incomplete reporting of FBD data across the region hinders comprehensive disease monitoring. |

[52] |

| Emerging pathogens |

Detection of emerging pathogens such as Arcobacter highlights poor hygiene practices in food handling. |

[44] |

| Lack of HACCP implementation |

Smaller establishments struggle with adopting and implementing effective HACCP protocols, causing poor food handling practices. |

[51] |

| Knowledge gaps among staff |

Insufficient understanding of risk prevention analysis principles among food establishment staff members. |

[51] |

3.5. Strategies to Prevent and Control FBD in CAC

Examining the strategies to prevent and control foodborne diseases (FBD) in Central America and the Caribbean (CAC), several studies highlight critical gaps in understanding and managing food safety within the region, emphasizing that the epidemiology of microbial and parasitic food pathogens has not been adequately addressed, leading to insufficient focus on the Caribbean food supply chains. There is a pressing need to improve food safety measures while simultaneously enhancing food production to tackle the region's food security challenges [

8]. For this purpose, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has operated in Central America since the 1960s, opening a regional office in Guatemala in 2003 to support Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Panama, as well as select activities in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Peru. CDC is also working closely with health ministries and partners, focusing on public health surveillance, laboratory strengthening, emergency preparedness, border and migrant health, antimicrobial resistance, and climate-health initiatives, including One Health. Since 2018, CDC has strengthened disease and antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Belize, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, and Guatemala, and, over the past two decades, has supported regional disease surveillance and detection of emerging pathogens through One Health workshops [

55,

56]. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) also works to prevent foodborne diseases (FBD) in the Americas by promoting risk-based food safety frameworks, supporting food safety education, and enhancing surveillance of food contamination. It builds laboratory and inspection capacities, fosters cooperation among health sectors, and strengthens communication on FBD risks. PAHO also coordinates with networks like INFOSAN for emergency responses and supports legal framework development to improve health outcomes related to FBD across the region [

49,

57].

Efforts to enhance foodborne disease surveillance have been spearheaded by initiatives such as PulseNet Latin America and the Caribbean (PNLAC), established in 2003 to strengthen laboratory-based surveillance and enable the early detection of outbreaks. Through standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) protocols, countries within the network can compile a national database of foodborne pathogens and contribute to a regional database maintained by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). This collaborative approach allows for the sharing of data among 24 reference laboratories across 16 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, fostering improved communication and coordination in outbreak investigations and public health responses [

58].

Recent technological advancements in next-generation sequencing tools, particularly whole-genome sequencing (WGS), have greatly increased the efficiency of detecting and characterizing infectious pathogens critical to public health. The Global Microbial Identifier (GMI) initiative has been established to create a shared database of genomes, facilitating the identification of microorganisms in various contexts, including food and the environment. By promoting the sharing of sequencing data, GMI supports public health institutions and the One Health concept, enabling early recognition of international outbreaks and providing essential information to clinicians and policymakers. However, challenges persist in building appropriate informatics systems to manage and harmonize data with laboratory operations. Moreover, while WGS is a promising advancement, organizational hurdles remain in adopting this technology, especially in developing countries [

59]

.

Across members of PulseNet International, differences in the maturity and complexity of laboratory surveillance networks, funding, human resources, and the importance of foodborne infections compared to other infectious diseases contribute to variations in WGS implementation strategies. To address the need for real-time surveillance, PulseNet International aims to standardize WGS-based subtyping using extended MLST-based approaches, specifically wgMLST, which offers optimal resolution and epidemiological concordance. Standardized protocols, validation studies, quality control programs, and training materials are essential for implementing and decentralizing new techniques. Recent evaluations indicate that in the United States, PulseNet prevents approximately 270,000 illnesses and saves

$500 million annually in medical costs and lost productivity, with an economic return on investment of about

$70 for every

$1 invested by public health agencies [

60].

WGS has offered high-resolution pathogen characterization in several studies in the region. For instance, in Trinidad and Tobago, for 146

Salmonella isolates from hatcheries, farms, processing plants, and retail outlets, 23 serovars were identified, with Kentucky (20.5%), Javiana (19.2%), Infantis (13.7%), and Albany (8.9%) being the most prevalent [

61]. This level of precision allows for better tracking of contamination sources along the production chain.

Similarly,

Aliarcobacter,

Listeria monocytogenes, and

Salmonella spp. have been identified using PCR-based methods across studies in the region, demonstrating the growing role of molecular techniques in pathogen detection [

34,

43,

46]. Furthermore, whole-genome sequencing of

Shigella sonnei isolates in Latin America, including isolates from Costa Rica and Guatemala, has revealed new genetic lineages and sublineages, indicating significant public health relevance and the potential for international transmission of foodborne pathogens [

62]. The findings highlight the importance of integrating surveillance systems across public health, animal health, and food production sectors to effectively detect and respond to foodborne infections.

Despite these advancements, significant challenges remain. For instance, Adesiyun et al., (2000) noted that the lack of routine investigation and reporting of foodborne outbreaks in the Caribbean hinders effective monitoring and response. Their study on

Salmonella enteritidis isolates revealed the difficulties in tracing the origins of outbreaks, highlighting the need for systematic surveillance mechanisms [

39].

Syndromic surveillance has emerged as a method to enhance food safety monitoring by combining traditional health data with non-traditional sources such as over-the-counter drug sales and environmental data. While this approach allows for quicker outbreak recognition, it also presents challenges, including the need for compatible infrastructure and increased human resources to manage the data effectively [

8]. Increased education for local farmers and food producers is essential to develop national and regional food industries and improve food safety practices throughout the supply chain.

Table 4.

Main strategies for prevention and control of FBD in CAC.

Table 4.

Main strategies for prevention and control of FBD in CAC.

| Strategy |

Description |

Outcomes |

Challenges |

References |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

Since the 1960s, CDC has operated in Central America, strengthening public health systems. A regional office opened in Guatemala in 2003 to coordinate disease surveillance, lab capacity, emergency response, and One Health initiatives. |

Improved disease detection and antimicrobial resistance tracking in the region. |

Coordination across multiple countries and health systems. |

[55,56] |

| Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). |

PAHO promotes risk-based food safety frameworks, education, and contamination surveillance in the Americas, strengthening lab capacities and emergency response with partners like INFOSAN. |

Enhanced FBD risk communication and response capacity in Latin American health systems. |

Varying levels of infrastructure and legal frameworks. |

[49,57] |

| PulseNet Latin America and the Caribbean (PNLAC) |

Established in 2003 to strengthen laboratory-based surveillance using standardized PFGE protocols. Countries contribute to a regional pathogen database maintained by PAHO, enhancing early outbreak detection and investigation. |

Improved coordination in outbreak detection and response across 16 countries. |

Variations in laboratory capacity, funding, and priority given to FBD compared to other infectious diseases. |

[58] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Tools |

Technologies like Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) allow more efficient pathogen detection and characterization, facilitating the early recognition of international outbreaks. Supports the One Health concept through shared genome databases. |

High-resolution pathogen tracking, including identification of serovars. Increased ability to detect genetic lineages. |

Organizational challenges, especially in developing countries. Data management and harmonization challenges due to inadequate informatics systems. |

[59,60] |

| Molecular Detection Methods |

Techniques such as PCR-based method, which have been used to identify pathogens like Aliarcobacter spp., Listeria spp., and Salmonella spp. across studies in the region. |

Improved detection of pathogens, allowing for quicker responses and more effective control strategies. |

Need for expanded access to molecular detection tools and trained personnel across the region. |

[46,46] |

| Global Microbial Identifier (GMI) |

A shared database for genome sequencing data, allowing identification of microorganisms in food, clinical, and environmental samples. |

Enhanced sharing of sequencing data. Supports early outbreak recognition and provides critical information for public health institutions and policymakers. |

Building and managing appropriate data informatics systems, particularly for developing countries. |

[59] |

4. Discussion

This systematic review consolidates evidence on bacterial foodborne diseases in Central America and the Caribbean, reflecting both pathogen prevalence and food source attribution. The findings align with earlier studies, although some discrepancies emerge in relation to pathogen frequency, key food sources, and outbreak reporting across the region.

Salmonella spp.,

Escherichia coli,

Campylobacter spp., and

Aliarcobacter spp., were the most reported bacteria regarding foodborne illnesses in CAC. For example, Pires et al., 2012 reported that

Salmonella spp. and

E. coli remained significant across decades, with the addition of

Shigella spp. and

Vibrio parahaemolyticus in later years [

54]. Similarly, Guerra et al., 2016 noted that non-typhoidal

Salmonella caused the majority of foodborne outbreaks between 2005-2014, followed by

Campylobacter and

Shigella [

53]. However, while

Campylobacter infections were substantial in some areas, Hull-Jackson & Adesiyun, (2019) found no significant

Campylobacter outbreaks in Barbados. The observed variance may be attributed to differences in surveillance, data collection, and underreporting practices across countries [

63].

As observed, a consistent theme across studies is the attribution of bacterial infections to animal-based foods. Eggs, poultry, and dairy products emerged as primary vehicles in both this review and earlier literature. Indar-Harrinauth et al., (2001) highlighted the association between

Salmonella Enteritidis and raw or undercooked eggs in Trinidad and Tobago, a finding that aligns with the region’s reliance on poultry products [

11]. Pires et al., (2012) also noted a shift in food source importance over time, with grains and beans gaining prominence by the 2000s, while the contribution of meat and water declined [

54]. In this review, poultry and egg-related outbreaks were consistently reported, emphasizing the significance of these sources. Similarly, studies from Trinidad and Tobago found widespread contamination of retail poultry and eggs with

Salmonella, indicating that food safety practices remain a concern.

Several studies, including this review, underscore the challenge of underreporting and the limited scope of laboratory-confirmed outbreak investigations, with much of the available research being outdated by more than 15 years. This is alarming because advancements in animal genetics, nutrition, and management practices over time may have altered livestock species' vulnerability to pathogens and their exposure risks [

25,

52]. The prevalence data from CAC countries shows significant variability, with Costa Rica, Trinidad & Tobago, and Guatemala taking the lead in pathogen surveillance. Costa Rica’s research on chicken and vegetables, as well as Trinidad & Tobago’s extensive monitoring of poultry and eggs, highlight proactive efforts in food safety. However, many other countries in the region show underreporting, likely due to limited resources or infrastructure. For instance, all the reports found regarding Dominican Republic, were made by alien countries and by extensive research of globally available data based on laboratory reported cases. These reports included other countries, such as Jamaica, Costa Rica, The Bahamas and Guatemala, but lacked specificity on the prevalence of each pathogen regarding each region, and some did not identify a source of infection, as they only displayed an overview for bacterial foodborne infections in CAC. In relation to this, Pires et al., (2012) observed that 80% of the reported outbreaks in the 2000s lacked identified food sources, potentially skewing the results [

54]. Similarly, Hull-Jackson & Adesiyun, (2019) reported under-detection of outbreaks in Barbados, suggesting deficiencies in outbreak investigations and laboratory testing [

63]. These challenges highlight the need for improved surveillance infrastructure to enhance food safety management across the region, as low reporting of prevalence, means a lack of representation of the actual epidemiological status of a country [

25].

The findings of this review, when contextualized within prior studies, emphasize the persistent burden of foodborne bacterial pathogens and the importance of monitoring specific foods like poultry, eggs, pork, beef and fresh vegetables. Variations across countries, such as the significance of

Campylobacter in some but not all regions, highlight the need for tailored public health strategies for different regions. Enhanced surveillance, better reporting mechanisms, and stricter food handling practices are essential for mitigating foodborne disease risks [

26]. Investments in monitoring and controlling food safety throughout the supply chain, especially in informal markets, could also address some of the risks identified in this review and prior investigations.

5. Conclusions

This investigation highlights the significant burden of bacterial foodborne diseases (FBD) in Central America and the Caribbean (CAC), emphasizing the prevalence of key pathogens in poultry, eggs, and vegetables. The findings reveal a consistent association between animal-based food products and FBD outbreaks, aligning with previous literature, though regional variations in pathogen prevalence and underreporting practices remain evident. The review also underscores the need for improved surveillance and reporting mechanisms to address underreporting and laboratory-confirmed outbreak investigations, as other nations in the region face challenges due to limited resources and infrastructure, making it difficult to assess the true epidemiological landscape. Investments in surveillance infrastructure, food safety measures, and education programs across the food supply chain, particularly in informal markets, are essential for mitigating the risks associated with bacterial foodborne illnesses.

Moreover, the economic impact of FBD on public health systems and tourism-dependent economies in these regions cannot be overlooked. Enhancing food safety by improving hygiene practices will be critical to reducing the transmission of foodborne pathogens. Further research and data collection, particularly through advanced technologies like WGS are necessary to build a comprehensive food safety management framework. This multifaceted approach, involving research, policy development, and public education, will be fundamental in tackling the public health challenge of foodborne diseases in CAC.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, L.O.M. and E.F.F; methodology, N.S, C.R, Y.F, R.TR, E.F.F and L.O M.; validation, L.O.M. and E.F.F.; formal analysis, N.S, C.R, Y.F, E.F.F and J.A.; investigation, N.S, C.R, Y.F, R.TR, E.F.F, and L.O.M.; resources, L.O.M., R.T.R, V.A.C.A and E.F.F.; data curation, N.S, C.R, E.F.F and L.O.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S, E.F.F. and L.O.M.; writing—review and editing, C.R, Y.F, L.O.M., L.E.F, R.T.R, V.A.C.A and E.F.F; supervision, L.O.M., R.T.R, L.E.F, V.A.C.A and E.F.F; project administration, L.O.M., R.T.R, V.A.C.A and E.F.F.; funding acquisition, L.O.M., L.E.F, R.T.R, V.A.C.A and E.F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Eduacion Supeior Ciencia y Tecnologia (MESCYT) through Fondo Nacional de Innovación y Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDOCYT), grant number 2022-2A4-204: Una Sola Salud-Inocuidad Alimentaria. Evaluación De Riesgos Microbiológicos Patogénicos En Carnes De Cerdo Y Pollo, Y Subproductos.

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Acknowledgments

This research project was successfully conducted thanks to the support provided by the Research Vice-Rectory and the Deanship of Basic and Environmental Sciences at Instituto Tecnologico de Santo Domingo (INTEC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Barnes, J.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.; Smith, J. Defining Food Safety Inspection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.M.M.; de Almeida, A.M.; Willingham, A.L. An Overview of Food Safety and Bacterial Foodborne Zoonoses in Food Production Animals in the Caribbean Region. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moye, Z.D.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage Applications for Food Production and Processing. Viruses 2018, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bintsis, T. Foodborne Pathogens. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, A.R.; Manzoor, M.; Hussain, A.; Altaf, J.; Rehman, S.U.; Javed, Z.; Afzal, I.; Noor, A.; Noor, F. Prospect of Microbial Food Borne Diseases in Pakistan: A Review. Brazilian J. Biol. 2021, 81, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvar, A.A.; Ahari, H.; Ataee, M. Antimicrobial Properties of Food Nanopackaging: A New Focus on Foodborne Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Foodborne Disease and the Need for Greater Foodborne Disease Surveillance in the Caribbean. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Foodborne Disease and the Need for Greater Foodborne Disease Surveillance in the Caribbean. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Thye, T.; Muñoz-Vargas, L.; Zamora-Sanabria, R.; Chercos, D.H.; Hernández-Rojas, R.; Robles, N.; Aguilar, D.; May, J.; Dekker, D. Molecular Characterization of Antibiotic Resistant Salmonella Enterica across the Poultry Production Chain in Costa Rica: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeda, Y. Food Safety and Infectious Diseases. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo). 2015, 61, S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indar-Harrinauth, L.; Daniels, N.; Prabhakar, P.; Brown, C.; Baccus-Taylor, G.; Comissiong, E.; Hospedales, J. C: of Salmonella Enteritidis Phage Type 4 in the Caribbean: Case-Control Study in Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies, 2001.

- Teshome, E.; Forsido, S.F.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Olika Keyata, E. Potentials of Natural Preservatives to Enhance Food Safety and Shelf Life: A Review. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’angelantonio, D.; Scattolini, S.; Boni, A.; Neri, D.; Di Serafino, G.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I.; Pomilio, F.; Di Giannatale, E.; Migliorati, G.; et al. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Colonization of Campylobacter Jejuni in Broiler Chickens before Slaughter. Viruses 2021, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo-Lascarez, S.; Gutierrez, L.Z.; Duarte-Martínez, F.; Zuniga, J.J.R.; Echandi, M.L.A.; Munoz-Vargas, L. Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Diversity of Campylobacter Spp. Isolated from Broiler Chicken at Three Levels of the Poultry Production Chain in Costa Rica. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariza, T.; Cho, M.J. Food Safety in Latin American Informal Food Establishments. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases: Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group 2007-2015. 2015.

- López, A.; Burgos, T.; Diáz, M.; Mejía, R.; Quinteros, E. Contaminación Microbiológica de La Carne de Pollo En 43 Supermercados de El Salvador. ALERTA Rev. Científica del Inst. Nac. Salud 2018, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebicz, A.; Śliżewska, K. Campylobacteriosis, Salmonellosis, Yersiniosis, and Listeriosis as Zoonotic Foodborne Diseases: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, M.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.; Dilbaghi, N.; Kumar, S. Current Scenario of Pathogen Detection Techniques in Agro-Food Sector. Biosensors 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, J.; Shi, Z.; Cao, A.; Fang, W.; Yan, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Molecular Methods for Identification and Quantification of Foodborne Pathogens. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.E.; Garman, K.N.; Hedberg, C.; Pennell-Huth, P.; Smith, K.E.; Sillence, E.; Baseman, J.; Scallan Walter, E. Improving Foodborne Disease Surveillance and Outbreak Detection and Response Using Peer Networks - The Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence. J. Public Heal. Manag. Pract. 2023, 29, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmate, D.; Onarinde, B.A. Food Safety Incidents in the Red Meat Industry: A Review of Foodborne Disease Outbreaks Linked to the Consumption of Red Meat and Its Products, 1991 to 2021. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 398, 110240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, C.; Mohr, A.H.; Lindsay, T.; Diez-Gonzalez, F.; Hueston, W.; Sampedro, F. Knowledge and Perceived Implementation of Food Safety Risk Analysis Framework in Latin America and the Caribbean Region. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apruzzese, I.; Song, E.; Bonah, E.; Sanidad, V.S.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Medardus, J.J.; Abdalla, N.; Hosseini, H.; Takeuchi, M. Investing in Food Safety for Developing Countries: Opportunities and Challenges in Applying Whole-Genome Sequencing for Food Safety Management. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, D.; Bianchini, A.; Chaves, B.D. A Review of Salmonella Prevalence and Salmonellosis Burden in the Caribbean Community Member Countries. Food Prot. Trends 2022, 42, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butaye, P.; Halliday-Simmonds, I.; Van Sauers, A. Salmonella in Pig Farms and on Pig Meat in Suriname. Antibiotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Hariharan, H.; Matthew, V.; Chappell, S.; Davies, R.; Parker, R.; Sharma, R. Prevalence, Serovars, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Salmonella Isolated from Blue Land Crabs (Cardisoma Guanhumi) in Grenada, West Indies. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarquin, C.; Alvarez, D.; Morales, O.; Morales, A.J.; López, B.; Donado, P.; Valencia, M.F.; Arévalo, A.; Muñoz, F.; Walls, I.; et al. Salmonella on Raw Poultry in Retail Markets in Guatemala: Levels, Antibiotic Susceptibility, and Serovar Distribution. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Tagg, K.A.; Kapsak, C.J.; Tobolowsky, F.; Birhane, M.G.; Francois Watkins, L.; Folster, J.P. Fourteen Mcr -1-Positive Salmonella Enterica Isolates Recovered from Travelers Returning to the United States from the Dominican Republic. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.R.; Gould, L.H.; Dunn, J.R.; Berkelman, R.; Mahon, B.E. Salmonella Infections Associated with International Travel: A Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) Study. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.E.; Crim, S.; Fullerton, K.; Han, P. V.; Cronquist, A.B.; Shiferaw, B.; Ingram, L.A.; Rounds, J.; Mintz, E.D.; Mahon, B.E. Travel-Associated Enteric Infections Diagnosed after Return to the United States, Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), 2004-2009. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 2004–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.S.; Georges, K.; Rahaman, S.; Abdela, W.; Adesiyun, A.A. Prevalence and Serotypes of Salmonella Spp. on Chickens Sold at Retail Outlets in Trinidad. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.S.; Georges, K.; Rahaman, S.; Abebe, W.; Adesiyun, A.A. Characterization of Salmonella Isolates Recovered from Stages of the Processing Lines at Four Broiler Processing Plants in Trinidad and Tobago. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Mohan, K.; Georges, K.; Dziva, F.; Adesiyun, A.A. Prevalence, Serovars, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella in Cecal Samples of Chickens Slaughtered in Pluck Shops in Trinidad. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Georges, K.; Rahaman, S.; Abebe, W.; Adesiyun, A.A. Occurrence, Risk Factors, Serotypes, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella Strains Isolated from Imported Fertile Hatching Eggs, Hatcheries, and Broiler Farms in Trinidad and Tobago. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesiyun, A.; Offiah, N.; Seepersadsingh, N.; Rodrigo, S.; Lashley, V.; Musai, L.; Georges, K. Microbial Health Risk Posed by Table Eggs in Trinidad. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesiyun, A.; Carson, A.; Mcadoo, K.; Bailey, C. Molecular Analysis of Salmonella Enteritidis Isolates from the Caribbean by Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis; 2000; Vol. 8;

- Rivera-Pérez, W.; Barquero-Calvo, E.; Zamora-Sanabria, R. Salmonella Contamination Risk Points in Broiler Carcasses during Slaughter Line Processing. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 2031–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, S.; Adesiyun, A.; Asgarali, Z.; Swanston, W. Occurrence of Selected Foodborne Pathogens on Poultry and Poultry Giblets from Small Retail Processing Operations in Trinidad; 2006; Vol. 69;

- Hegde, S.; Benoit, S.R.; Arvelo, W.; Lindblade, K.; López, B.; McCracken, J.P.; Bernart, C.; Roldan, A.; Bryan, J.P. Burden of Laboratory-Confirmed Shigellosis Infections in Guatemala 2007-2012: Results from a Population-Based Surveillance System. BMC Public Health 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Arrieta, K.; Matamoros-Montoya, K.; Arias-Echandi, M.L.; Huete-Soto, A.; Redondo-Solano, M. Presence of Listeria Monocytogenes in Ready-to-Eat Meat Products Sold at Retail Stores in Costa Rica and Analysis of Contributing Factors. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallas-Padilla, K.L.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.E.; Jaramillo, H.F.; Echandi, M.L.A. Arcobacter: Comparison of Isolation Methods, Diversity, and Potential Pathogenic Factors in Commercially Retailed Chicken Breast Meat from Costa Rica. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, E.G.; Jaramillo, H.F.; Ulate, C.C.; Echandi, M.L.A. Isolation and Identification of Zoonotic Species of Genus Arcobacter from Chicken Viscera Obtained from Retail Distributors of the Metropolitan Area of San José, Costa Rica. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias Echandi, M.L.; Huete Soto, A.; Castillo Blanco, J.M.; Fernández, F.; Fernandez Jaramillo, H. Occurrence of Aliarcobacter Spp. in Fresh and Pre-Cut Vegetables of Common Use in San José, Costa Rica. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Gómez, C.; Mulvey, M.R.; Vargas, P.; Del Mar Gamboa-Coronado, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Rodríguez-Cavillini, E. Isolation of a Toxigenic and Clinical Genotype of Clostridium Difficile in Retail Meats in Costa Rica. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Bacterial Foodborne Diseases Reported in Countries from Central America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1NOQWhh7EQrWnol8jsEr8Yv9G7K5nYtw&usp=sharing (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Pan American Health Organization WHO Food Handler Manual-Student; 2017; ISBN 9789253097739.

- Maroto Martín, L.O.; Franco de Los Santos, E.F.; Rodriguez de Francisco, L.E. Situación de La Inocuidad Alimentaria En República Dominicana. INTEC 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, S.M.; Maharaj, S.R.; James, K. Description of the Food Safety System in Hotels and How It Compares with HACCP Standards. J. Travel Med. 2009, 16, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persad, A.K.; LeJeune, J. A Review of Current Research and Knowledge Gaps in the Epidemiology of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli and Salmonella Spp. in Trinidad and Tobago. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.M.M.; de Almeida, A.M.; Willingham, A.L. An Overview of Food Safety and Bacterial Foodborne Zoonoses in Food Production Animals in the Caribbean Region. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2016, 48, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.M.; Vieira, A.R.; Perez, E.; Wong, D.L.F.; Hald, T. Attributing Human Foodborne Illness to Food Sources and Water in Latin America and the Caribbean Using Data from Outbreak Investigations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 152, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC in Central America. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/global-health/countries/central-america.html (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- CDC in the Dominican Republic. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/global-health/countries/dominican-republic.html (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Pan American Health Organization Pan American Commission on Food Safety (COPAIA 6). In Proceedings of the 6th Meeting of the Pan American Commission on Food Safety; 2012.

- Chinen, I.; Campos, J.; Dorji, T.; Pérez Gutiérrez, E. PulseNet Latin America and the Caribbean Network: Present and Future. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Pierneef, R.E.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Maguire, M.; Georges, K.; Abebe, W.; Adesiyun, A.A. Phylogenetic Analyses of Salmonella Detected along the Broiler Production Chain in Trinidad and Tobago. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadon, C.; Van Walle, I.; Gerner-Smidt, P.; Campos, J.; Chinen, I.; Concepcion-Acevedo, J.; Gilpin, B.; Smith, A.M.; Kam, K.M.; Perez, E.; et al. Pulsenet International: Vision for the Implementation of Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for Global Foodborne Disease Surveillance. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.S.; Pierneef, R.E.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Maguire, M.; Li, C.; Tyson, G.H.; Ayers, S.; Georges, K.; Abebe, W.; Adesiyun, A.A. Molecular Characterization of Salmonella Detected along the Broiler Production Chain in Trinidad and Tobago. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, K.S.; Campos, J.; Pichel, M.; Della Gaspera, A.; Duarte-Martínez, F.; Campos-Chacón, E.; Bolaños-Acuña, H.M.; Guzmán-Verri, C.; Mather, A.E.; Diaz Velasco, S.; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing of Shigella Sonnei through PulseNet Latin America and Caribbean: Advancing Global Surveillance of Foodborne Illnesses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull-Jackson, C.; Adesiyun, A.A. Foodborne Disease Outbreaks in Barbados (1998-2009): A 12-Year Review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).