Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Rift Valley fever (RVF) disease, a climate-sensitive zoonosis, causes 100% abortions and death in infected animals. This shock has an immediate impact on food prices, particularly for animal-sourced foods. This study used an Interrupted Time Series (ITS) approach and an Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model to assess the effects of economic disruptions, specifically the RVF outbreak on Kenya's food price index during two consecutive RVF outbreaks in 2018 and 2021. Data from several Kenyan cities, including Nairobi, Kisumu, Eldoret, and Mombasa, were analyzed to identify inflation trends across different markets. The findings show significant price index fluctuations, with inflation escalating following critical intervention periods, particularly during the outbreak. The ARIMA model successfully identified these changes, highlighting the distinct effects across all regions, with some areas exhibiting significant forecasting inaccuracies. This analysis generates new knowledge, provides critical insights into market dynamics, and presents a predictive framework for dealing with future economic disruptions in Kenya and elsewhere. Policymakers can use these findings to create targeted strategies for stabilizing food prices and ensuring economic resilience.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Preparation

2.2. Stationarity Testing

2.3. ARIMA Model Specification and Estimation

2.4. Intervention Analysis

2.5. Forecasting

2.6. Model Validation

3. Results

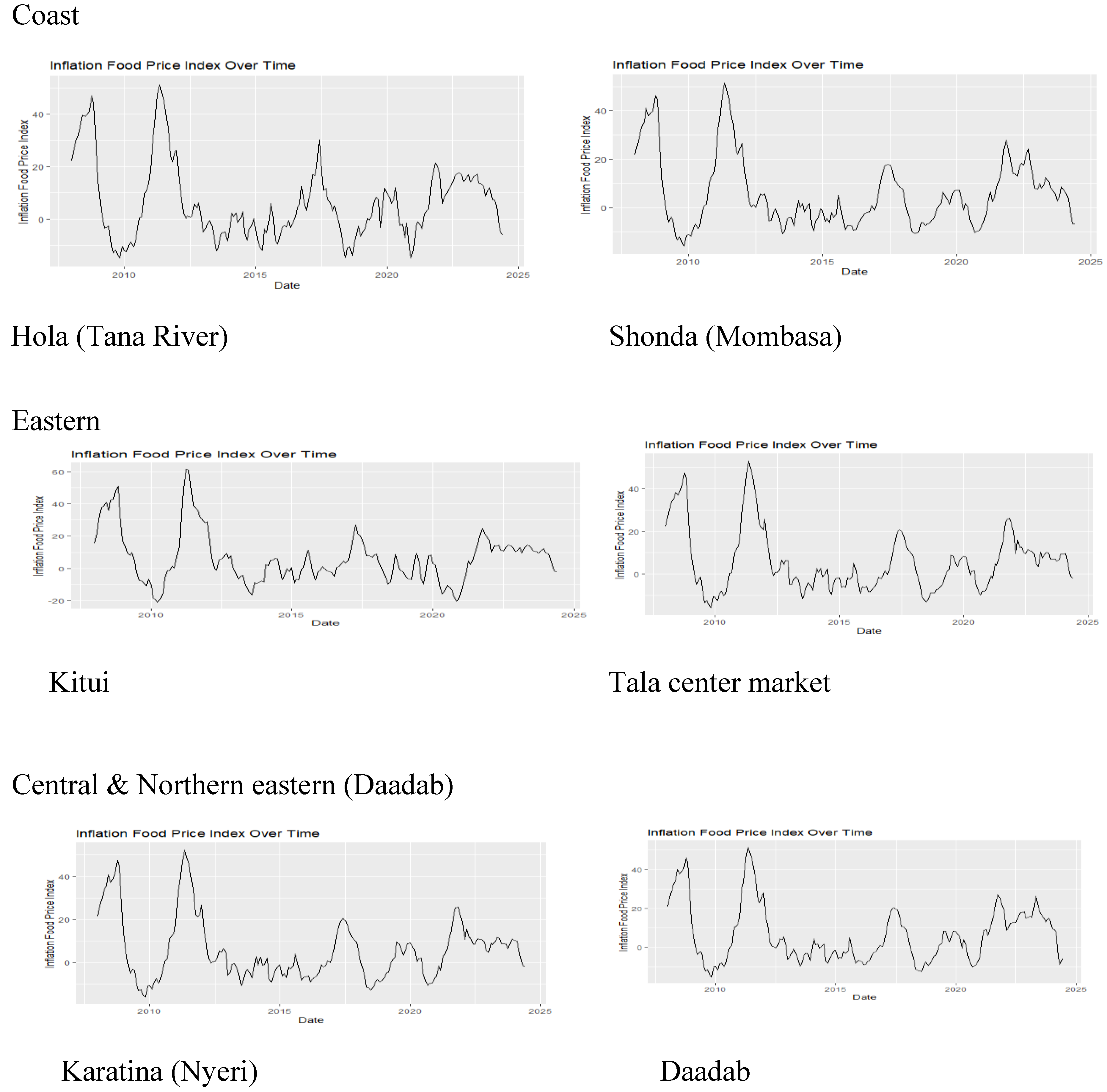

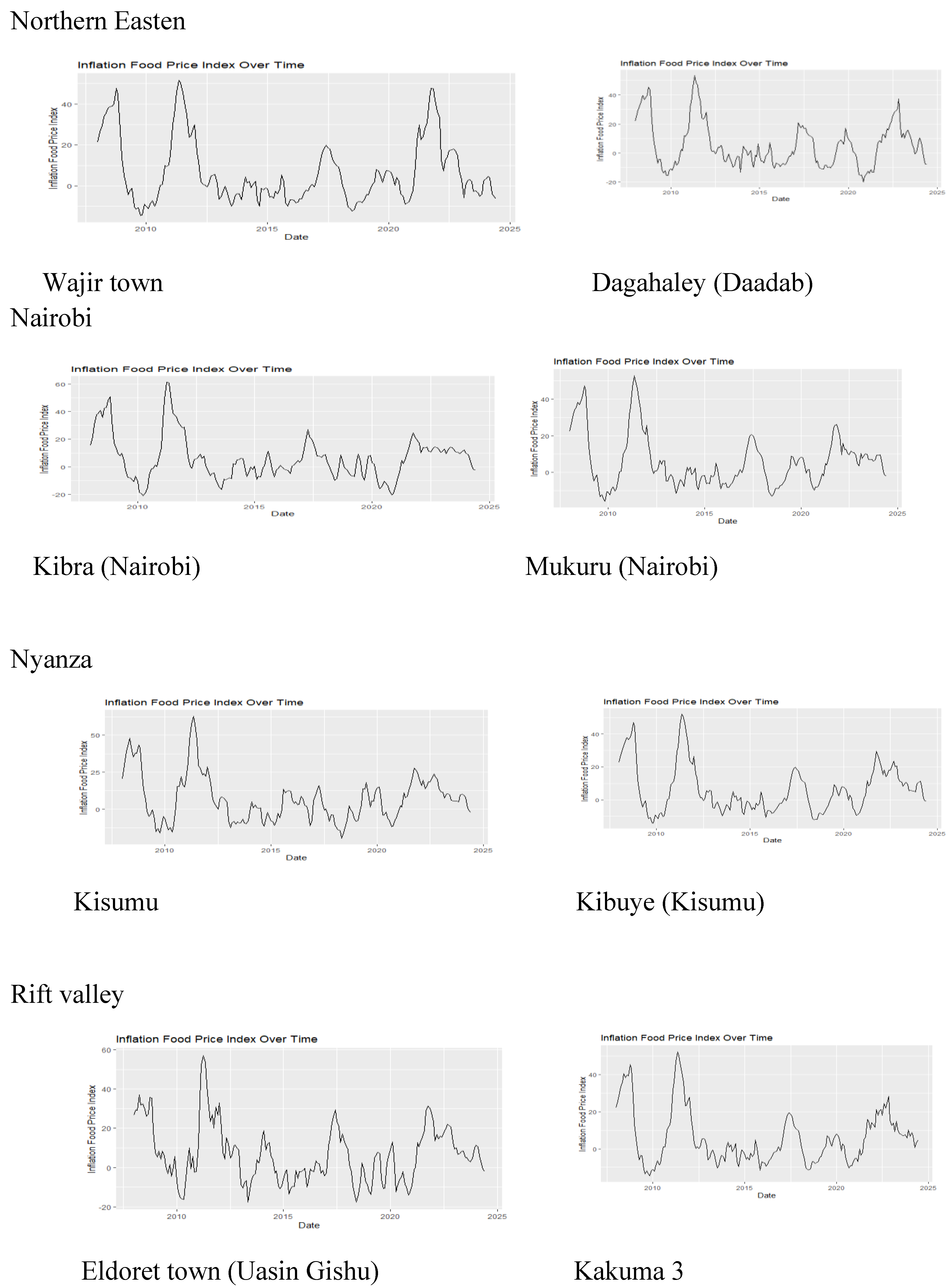

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Test for Stationarity

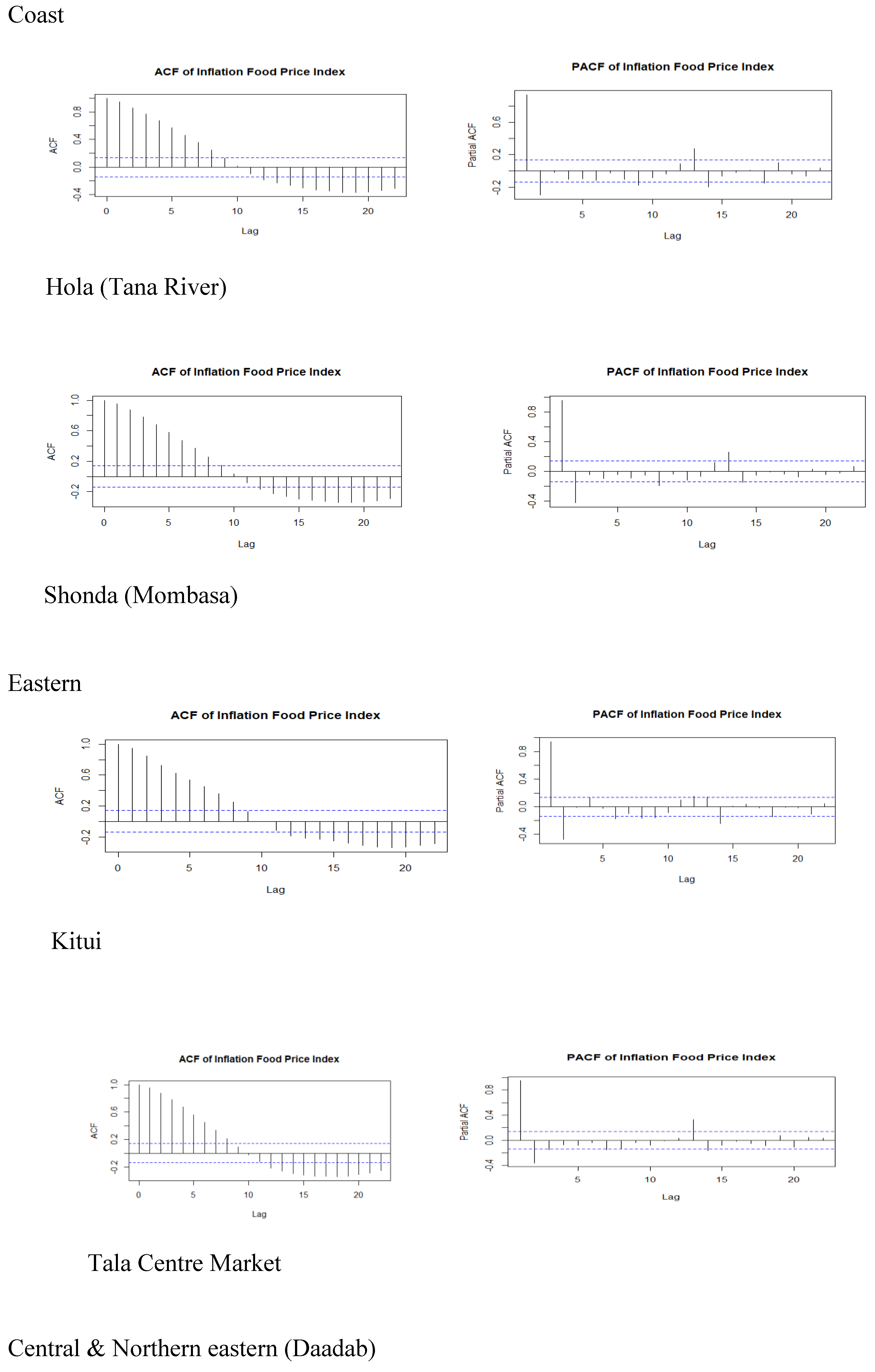

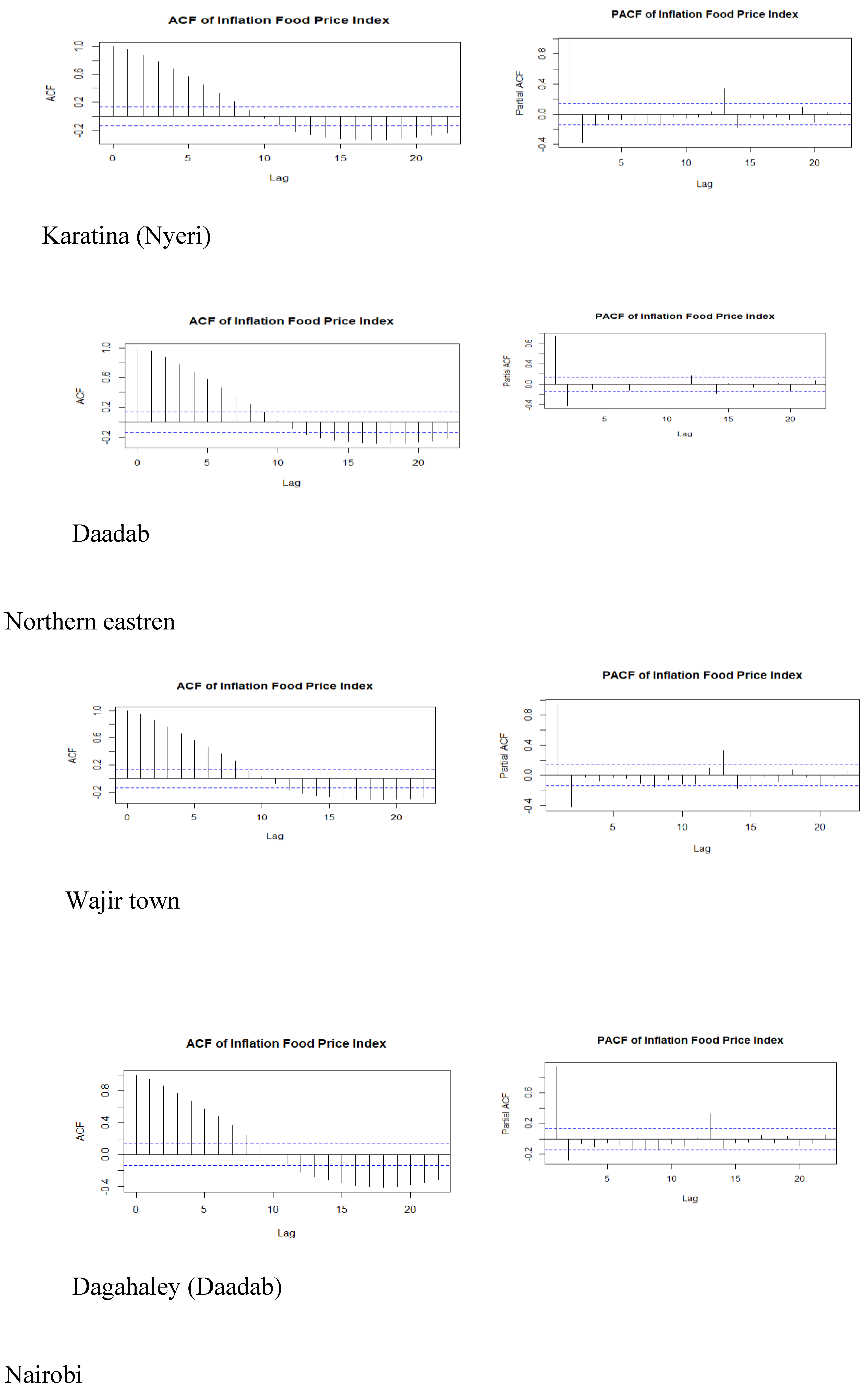

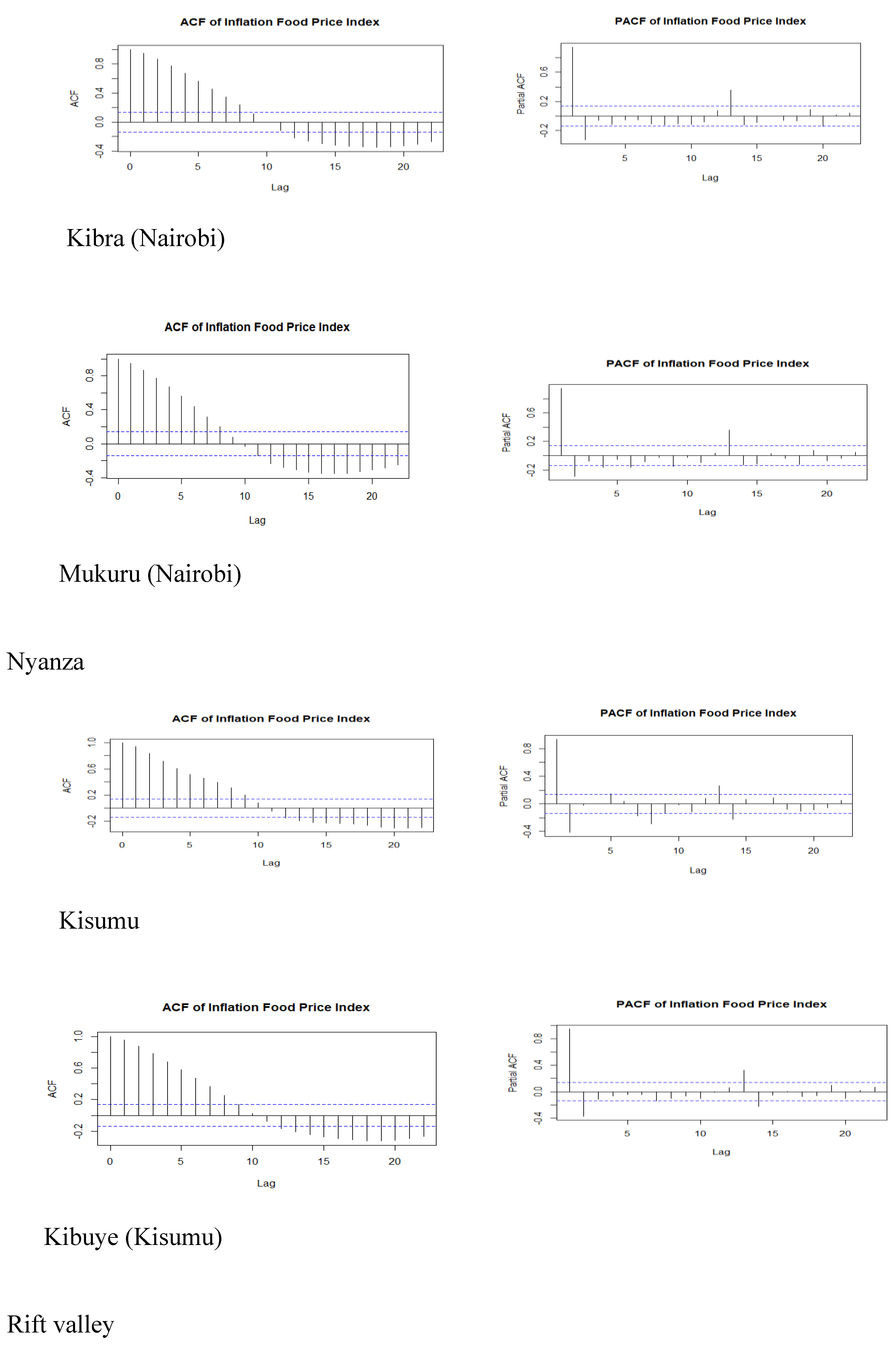

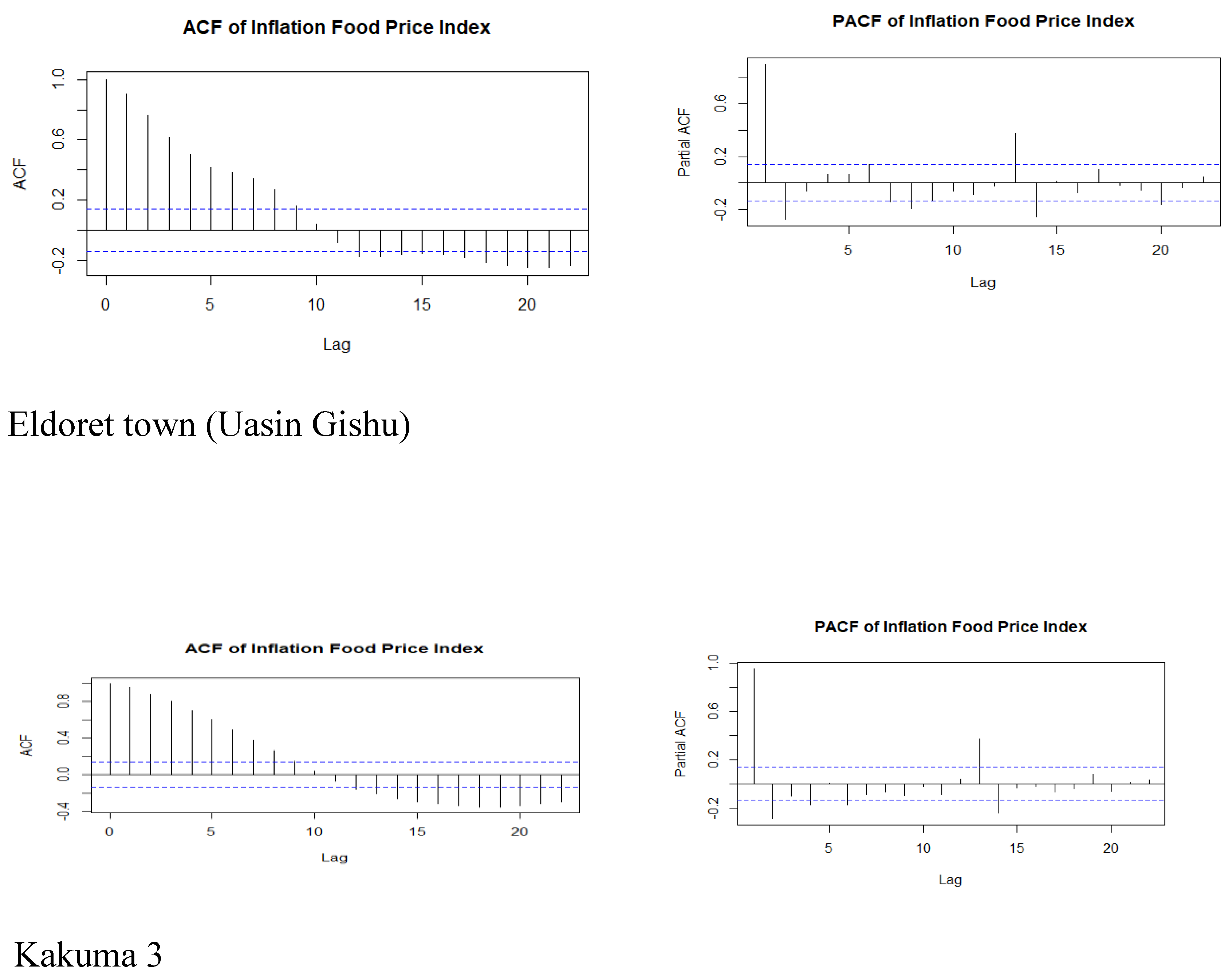

3.3. Autocorrelation (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Plots (PACF)

Plot Data

3.4. Autocorrelation (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Plots (PACF)

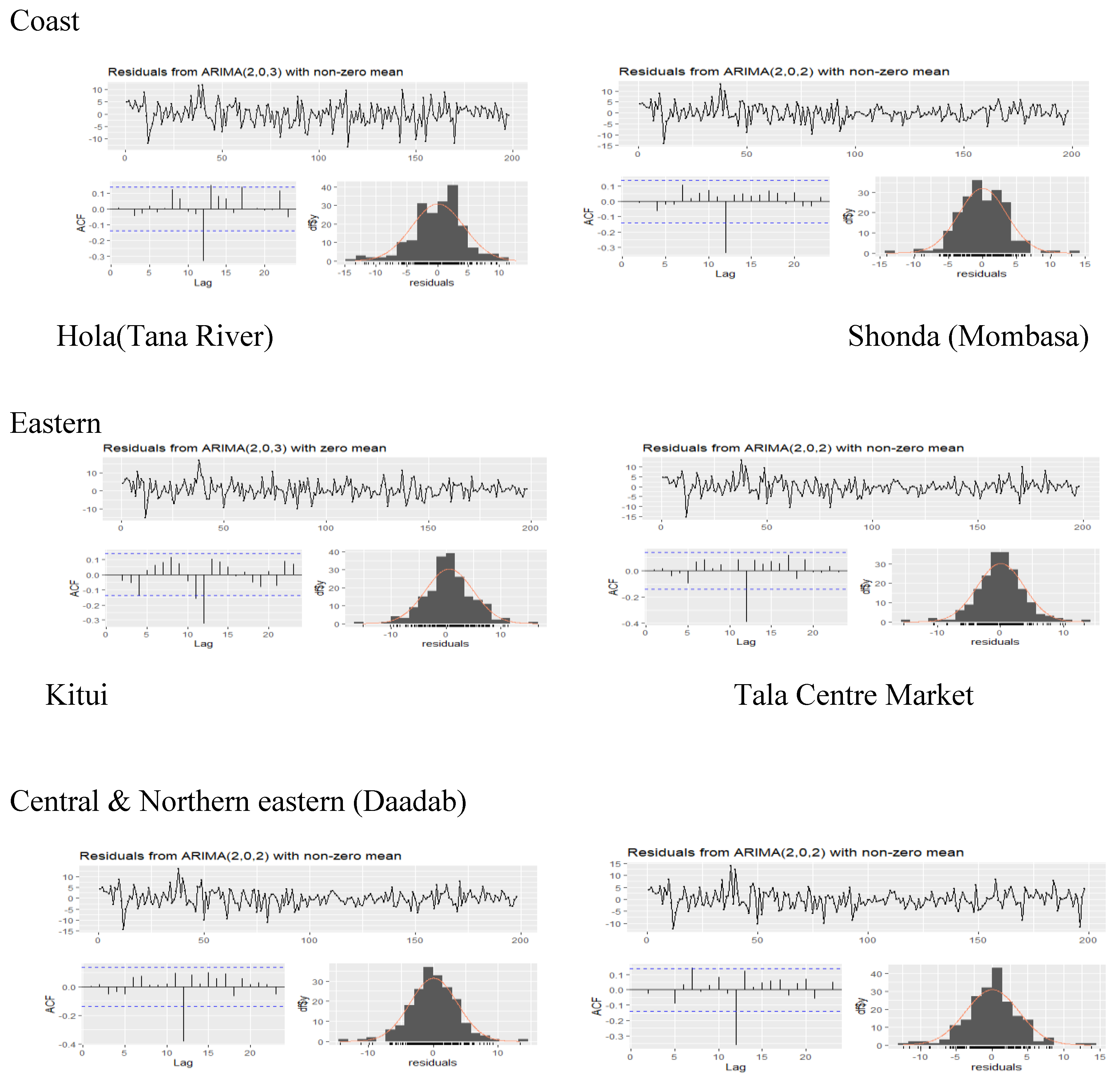

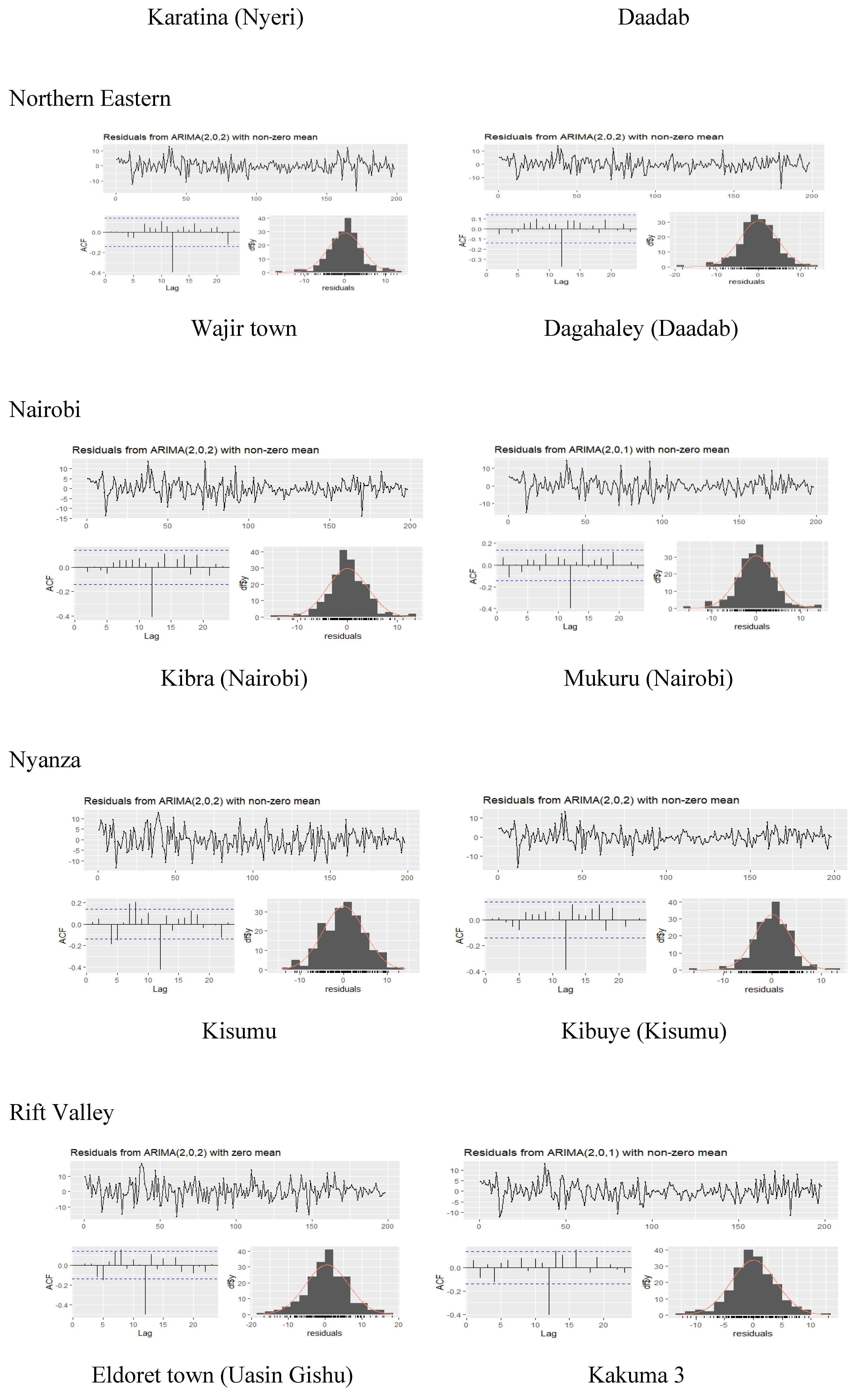

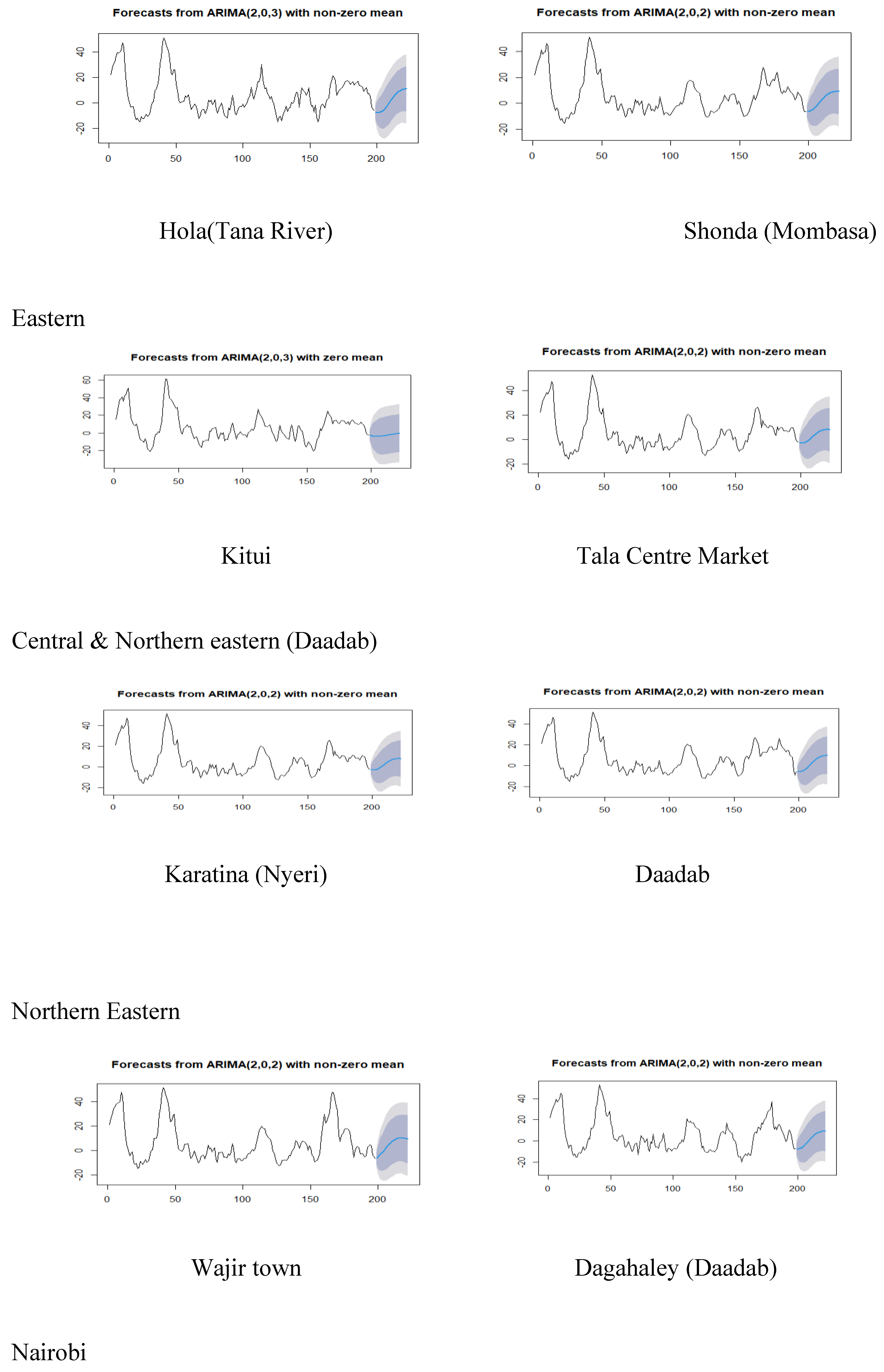

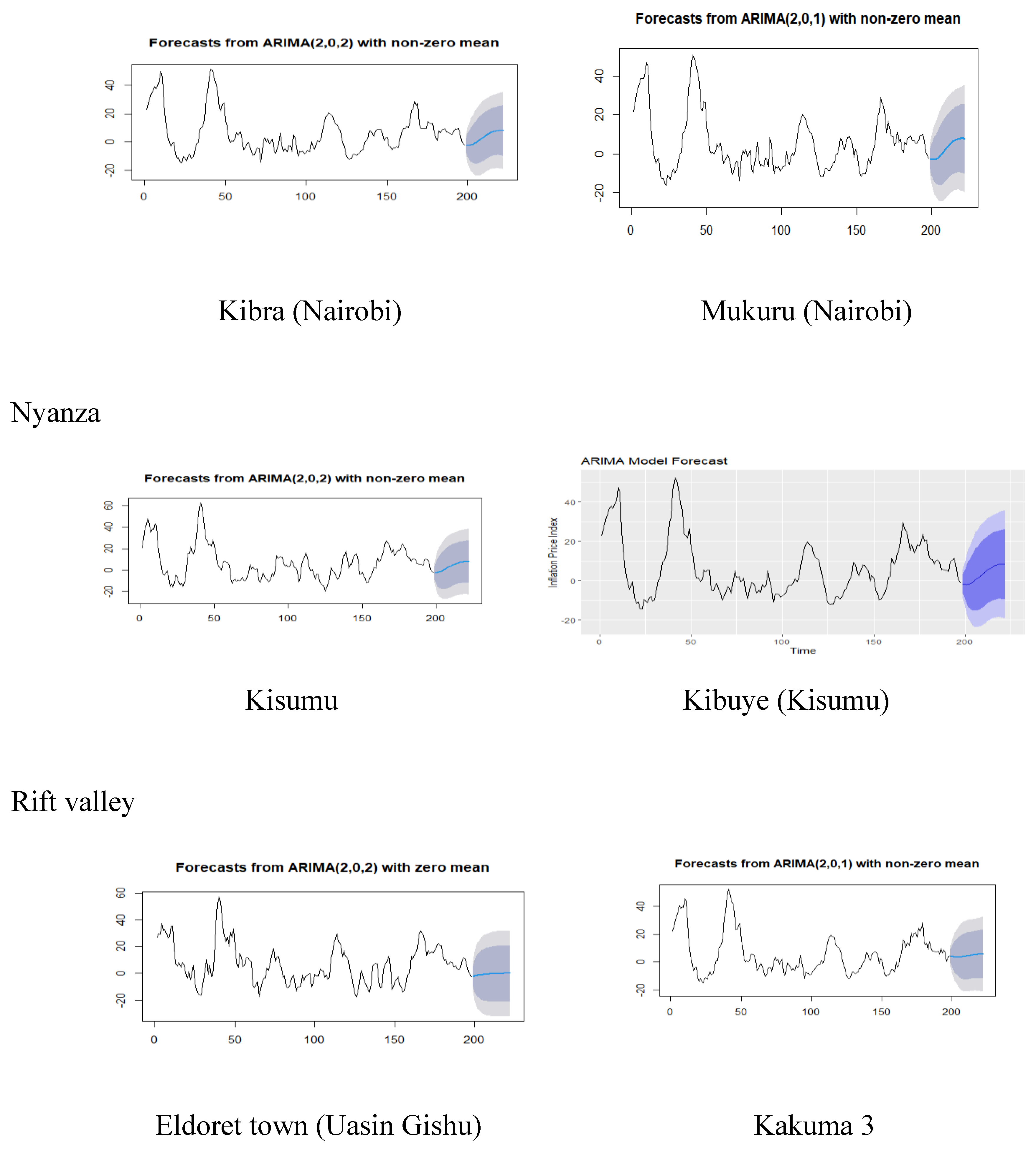

3.4. Comparison of the Forecasted and Actual Values at Various Response Levels Using the ITS-ARIMA Model from June 2018 to February 2021

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- P. Bonnet, M. Tibbo, A. Workalemahu, and M. Gau, “Rift Valley Fever an emerging threat to livestock trade and food security in the Horn of Africa : a review,” Proceedings of the 9th National Conference of the Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP). 30-31 August 2001. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Accessed: Oct. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/559463/.

- “Food Security in an Era of Economic Volatility - Naylor - 2010 - Population and Development Review - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00354.x.

- D. Manheim, M. Chamberlin, O. Osoba, R. Vardavas, and M. Moore, Improving Decision Support for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control: Aligning Models and Other Tools with Policymakers’ Needs. RAND Corporation, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Meyimdjui, “Food Price Shocks and Government Expenditure Composition: Evidence from African Countries.” Feb. 06, 2017. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01457366.

- M. O. Nanyingi et al., “A systematic review of Rift Valley Fever epidemiology 1931–2014,” Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Omosa, B. Bett, and B. Kiage, “Climate change and Rift Valley fever disease outbreak: implications for the food environment of pastoralists,” The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 6, p. S17, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Gerken et al., “Exploring potential risk pathways with high risk groups for urban Rift Valley fever virus introduction, transmission, and persistence in two urban centers of Kenya,” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, vol. 17, no. 1, p. e0010460, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Espinosa, D. Tago, and N. Treich, “Infectious Diseases and Meat Production,” Environ Resource Econ, vol. 76, no. 4, pp. 1019–1044, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- I.F. P. Research Institute (Ifpri), “2011 Global Hunger Index The Challenge of Hunger: Taming price spikes and excessive food price volatility,” International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, 2011. [CrossRef]

- “A SIMPLIFIED TIME-SERIES ANALYSIS FOR EVALUATING TREATMENT INTERVENTIONS - Tryon - 1982 - Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis - Wiley Online Library.” Accessed: Oct. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1901/jaba.1982.15-423.

- J. Kisabuli, J. Ong’ala, and E. Odero, “Intervention Time Series Modeling of Infant Mortality: Impact of Free Maternal Health Care,” AJPAS, pp. 38–47, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, X. Liu, X. Li, C. Xue, B. Zhang, and Y. Wang, “Interruption time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average model: evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the epidemic trend of gonorrhea in China,” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 2073, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Chitikela et al., “Artificial-Intelligence-Based Time-Series Intervention Models to Assess the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tomato Supply and Prices in Hyderabad, India,” Agronomy, vol. 11, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “MACROECONOMIC VARIABLES AND FOOD PRICE INFLATION IN NIGERIA (1980-2018).” Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/313621?v=pdf.

- C. Han, “Cross-validation for autoregressive models.,” University of Louisville, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ali, S. Bogarra, M. N. Riaz, P. P. Phyo, D. Flynn, and A. Taha, “From Time-Series to Hybrid Models: Advancements in Short-Term Load Forecasting Embracing Smart Grid Paradigm,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial | International Journal of Epidemiology | Oxford Academic.” Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/46/1/348/2622842.

- Y. K. Lee, E. Mammen, J. P. Nielsen, and B. U. Park, “Operational Time and in-Sample Density Forecasting,” The Annals of Statistics, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 1312–1341, 2017.

- D. G. Mayer and D. G. Butler, “Statistical validation,” Ecological Modelling, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 21–32, Jul. 1993. [CrossRef]

- A. Hall, “Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series With Pretest Data-Based Model Selection,” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 461–470, Oct. 1994. [CrossRef]

- .

- “Autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation functions to improve neural networks models on univariate time series forecasting.” Accessed: Oct. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6252470.

- T. M. Awan and F. Aslam, “Prediction of Daily Covid-19 Cases in European Countries Using Automatic Arima Model,” Journal of Public Health Research, vol. 9, no. 3, p. jphr.2020.1765, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Noordzij, M. van Diepen, F. C. Caskey, and K. J. Jager, “Relative risk versus absolute risk: one cannot be interpreted without the other,” Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, vol. 32, no. suppl_2, pp. ii13–ii18, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Gilmour, L. Degenhardt, W. Hall, and C. Day, “Using intervention time series analyses to assess the effects of imperfectly identifiable natural events: a general method and example,” BMC Med Res Methodol, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 16, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, X. Liu, X. Li, C. Xue, B. Zhang, and Y. Wang, “Interruption time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average model: evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the epidemic trend of gonorrhea in China,” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 2073, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

| Town | Min | 1st Qu | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dadaab town | -15.120 | -4.875 | 2.250 | 6.507 | 14.830 | 51.630 |

| Dagahaley (Daadab) | -19.980 | -6.782 | 1.705 | 5.347 | 13.033 | 53.540 |

| Eldoret town (Uasin Gishu) | -17.750 | -3.257 | 5.180 | 6.767 | 14.755 | 57.180 |

| Hola (Tana River) | -14.890 | -3.647 | 2.315 | 6.121 | 13.730 | 51.290 |

| Kakuma 3 | -14.590 | -5.140 | 1.430 | 5.807 | 12.643 | 52.200 |

| Karatina (Nyeri) | -16.090 | -4.780 | 1.965 | 5.597 | 10.883 | 52.160 |

| Kibra (Nairobi) | -14.970 | -4.527 | 2.475 | 6.014 | 10.742 | 51.450 |

| Kibuye (Kisumu) | -14.300 | -4.805 | 2.280 | 6.292 | 13.672 | 52.310 |

| Kisumu | -19.860 | -5.800 | 4.930 | 6.752 | 14.825 | 62.910 |

| kitui | -20.930 | -3.868 | 4.615 | 6.353 | 12.845 | 61.500 |

| Mukuru (Nairobi) | -16.000 | -5.000 | 1.865 | 5.412 | 10.360 | 50.870 |

| Shonda (Mombasa) | -15.670 | -4.870 | 1.900 | 5.698 | 12.170 | 51.420 |

| Tala Centre Market | -15.920 | -4.798 | 2.035 | 5.688 | 10.815 | 52.890 |

| Wajir town | -14.590 | -4.875 | 1.230 | 6.507 | 13.707 | 13.707 |

| Variables | Level constant and trend | Order of integration |

|---|---|---|

| Dadaab town | 3.9662 (0.01205) | I (0) |

| Dagahaley (Daadab) | 3.955 (0.0126) | I (0) |

| Eldoret town (Uasin Gishu) | 3.0076 (0.0542) | I (0) |

| Hola(Tana River) | 4.2242 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Kakuma 3 | 4.3431 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Karatina (Nyeri) | 4.3561 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Kibra (Nairobi) | 4.01 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Kibuye (Kisumu) | 3.9031 (0.01517) | I (0) |

| Kisumu | 3.0422 (0.0397) | I (0) |

| kitui | 3.8492 (0.01783) | I (0) |

| Mukuru (Nairobi) | 4.5872 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Shonda (Mombasa) | 4.1248 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Tala Centre Market | 4.1018 (0.01) | I (0) |

| Wajir town | 3.6841 (0.02688) | I (0) |

| Town | ARIMA model | AIC | AICc | BIC | log likelihood | ME | RMSE | MAE | MPE | MAPE | MASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dadaab town | (2,0,2) | 1096.370 | 1096.810 | 1116.100 | -542.180 | 0.026 | 3.711 | 2.740 | 91.702 | 152.494 | 0.893 |

| Dagahaley (Daadab) | (2,0,2) | 1174.44 | 1174.880 | 1194.170 | -581.220 | 0.042 | 4.523 | 3.409 | -14.849 | 93.261 | 0.938 |

| Eldoret town (Uasin Gishu) | (2,0,2) | 1273.590 | 1273.900 | 1290.030 | -631.790 | 0.543 | 5.850 | 4.395 | 168.852 | 236.118 | 0.940 |

| Hola (Tana River) | (2,0,3) | 1149.270 | 1149.860 | 1172.280 | -567.630 | 0.045 | 4.222 | 3.240 | 82.171 | 146.802 | 0.910 |

| Kakuma 3 | (2,0,1) | 1116.790 | 1117.000 | 1133.230 | -553.390 | 0.027 | 3.929 | 2.994 | 372.182 | 455.883 | 0.940 |

| karatina (Nyeri) | (2,0,2) | 1090.080 | 1090.520 | 1109.810 | -539.040 | 0.032 | 0.652 | 2.734 | -0.821 | 133.018 | 0.895 |

| Kibra (Nairobi) | (2,0,2) | 1131.120 | 1131.560 | 1150.850 | -559.560 | 0.038 | 4.054 | 2.942 | -189.803 | 372.409 | 0.910 |

| Kibuye (Kisumu) | (2,0,2) | 1100.320 | 1100.760 | 1120.050 | -544.160 | 0.021 | 3.749 | 2.808 | 42.283 | 124.218 | 0.916 |

| Kibuye | (2,0,2) | 1196.940 | 1197.380 | 1216.670 | -592.470 | 0.034 | 4.790 | 3.775 | -4.965 | 94.614 | 0.923 |

| kitui | (2,0,3) | 1163.470 | 1163.910 | 1183.200 | -575.730 | 0.561 | 4.398 | 3.323 | 16.768 | 90.581 | 0.872 |

| Mukuru (Nairobi) | (3,0,3) | 1142.450 | 1142.760 | 1158.890 | -566.220 | 0.039 | 4.193 | 3.127 | -Inf | Inf | 0.920 |

| Shonda (Mombasa) | (2,0,2) | 1074.370 | 1074.810 | 1094.100 | -531.190 | 0.027 | 3.509 | 2.682 | -119.254 | 204.903 | 0.875 |

| Tala Centre Market | (1,0,2) | 1096.380 | 1096.820 | 1116.110 | -542.190 | 0.030 | 3.711 | 2.724 | 5.992 | 83.252 | 0.894 |

| Wajir town | (2,0,2) | 1145.370 | 1145.810 | 1165.100 | -566.690 | 0.028 | 4.201 | 3.133 | 30.240 | 119.462 | 0.922 |

| Hola (Tana River) | Shonda (Mombasa) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -14.65 | -12.7492 | -1.90082 | 14.90934 | -10.47 | -11.8966 | 1.426618 | -11.9918 |

| Apr-19 | 0.3 | -13.1118 | 13.41177 | -102.288 | -0.66 | -12.426 | 11.76604 | -94.6886 |

| Nov-20 | -10.88 | -13.1118 | 2.231787 | -17.0212 | -9.34 | -12.4261 | 3.08612 | -24.8358 |

| Feb-21 | -2.83 | -13.1118 | 10.28179 | -78.4164 | -2.46 | -12.4261 | 9.96612 | -80.203 |

| Kitui | Tala Centre Market | |||||||

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -9.72 | -22.135 | 12.41497 | -56.0876 | -11.97 | -11.8966 | -0.07338 | 0.616827 |

| Apr-19 | -7 | -22.135 | 15.13497 | -68.3758 | -0.65 | -12.426 | 11.77604 | -94.769 |

| Nov-20 | -20.33 | -22.135 | 1.804968 | -8.15438 | 26.23 | -12.4261 | 38.65612 | -311.088 |

| Feb-21 | -7.36 | -22.135 | 14.77497 | -66.7494 | 9.45 | -12.4261 | 21.87612 | -176.049 |

| Karatina (Nyeri) | Daadab | |||||||

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute efect | Relative efect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolut effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -12.08 | -2.8956 | -9.1844 | 317.1844 | -11.89 | -13.741 | 1.850991 | -13.4706 |

| Apr-19 | -0.39 | 3.030979 | -3.42098 | -112.867 | -0.55 | -14.3007 | 13.75066 | -96.154 |

| Nov-20 | 25.65 | 5.521694 | 20.12831 | 364.5314 | -7.53 | -14.3008 | 6.770756 | -47.3454 |

| Feb-21 | 10.64 | 4.462524 | 6.177476 | 138.4301 | 5.2 | -14.3008 | 19.50076 | -136.362 |

| Wajir Town | Dagahaley (Daadab) | |||||||

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -11.23 | -13.5801 | 2.350065 | -17.3053 | -10.61 | -10.8507 | 0.240678 | -2.21809 |

| Apr-19 | -0.9 | -14.0976 | 13.19758 | -93.6159 | -2.17 | -10.9787 | 8.808729 | -80.2345 |

| Nov-20 | -7.86 | -14.0976 | 6.237631 | -44.246 | -19.98 | -10.9787 | -9.00127 | 81.98827 |

| Feb-21 | 9.87 | -14.0976 | 23.96763 | -170.012 | -12.39 | -10.9787 | -1.41127 | 12.85459 |

| Kibra (Nairobi) | Mukuru (Nairobi) | |||||||

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -11.46 | -2.30316 | -9.15684 | 397.5782 | -11.31 | -22.135 | 10.82497 | -48.9044 |

| Apr-19 | -0.57 | 3.717389 | -4.28739 | -115.333 | -0.36 | -22.135 | 21.77497 | -98.3736 |

| Nov-20 | -4.54 | 6.332951 | -10.873 | -171.689 | -10.27 | -22.135 | 11.86497 | -53.6028 |

| Feb-21 | 1.87 | 5.481701 | -3.6117 | -65.8865 | -2.5 | -22.135 | 19.63497 | -88.7057 |

| Kisumu | Kibuye (Kisumu) | |||||||

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -15.91 | -22.135 | 6.224968 | -28.1228 | -12.24 | -2.30316 | -9.93684 | 431.4447 |

| Apr-19 | 2.84 | -22.135 | 24.97497 | -112.83 | -0.56 | 3.717389 | -4.27739 | -115.064 |

| Nov-20 | -7.24 | -22.135 | 14.89497 | -67.2916 | -8.02 | 6.332951 | -14.353 | -226.639 |

| Feb-21 | 2.43 | -22.135 | 24.56497 | -110.978 | 11.47 | 5.481701 | 5.988299 | 109.2416 |

| Eldoret Town (Uasin Gishu) | Kakuma 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative effect (%) | True values | Predict values | Absolute effect | Relative efect (%) |

| Jun-18 | -17.75 | -15.848 | -1.90201 | 12.00155 | -11.03 | -12.7366 | 1.706641 | -13.3995 |

| Apr-19 | 4.9 | -15.8978 | 20.79778 | -130.822 | -1.05 | -13.3087 | 12.25874 | -92.1104 |

| Nov-20 | -14.01 | -15.8978 | 1.887776 | -11.8745 | -9.24 | -13.3088 | 4.068846 | -30.5725 |

| Feb-21 | -1.25 | -15.8978 | 14.64778 | -92.1373 | -5.21 | -13.3088 | 8.098846 | -60.8531 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).