Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Cancer Transition, Stemness, Progression, and Ecological Evolution

1.1. Primary Drivers of EMT

1.1.1. ROS - Hypoxia Stress

1.1.2. Metabolic and Mitochondrial Stress

1.1.3. Inflammatory Stress and Role of TGFβ

1.1.4. Spatial Stress

1.1.5. Hypoxia - Metabolic – Inflammatory Stress and Cancer Immune Editing Loop

1.1.6. Therapeutic Interventions – Evolutionary Mutational Predator - Prey Game

1.2. Molecular Drivers of EMT

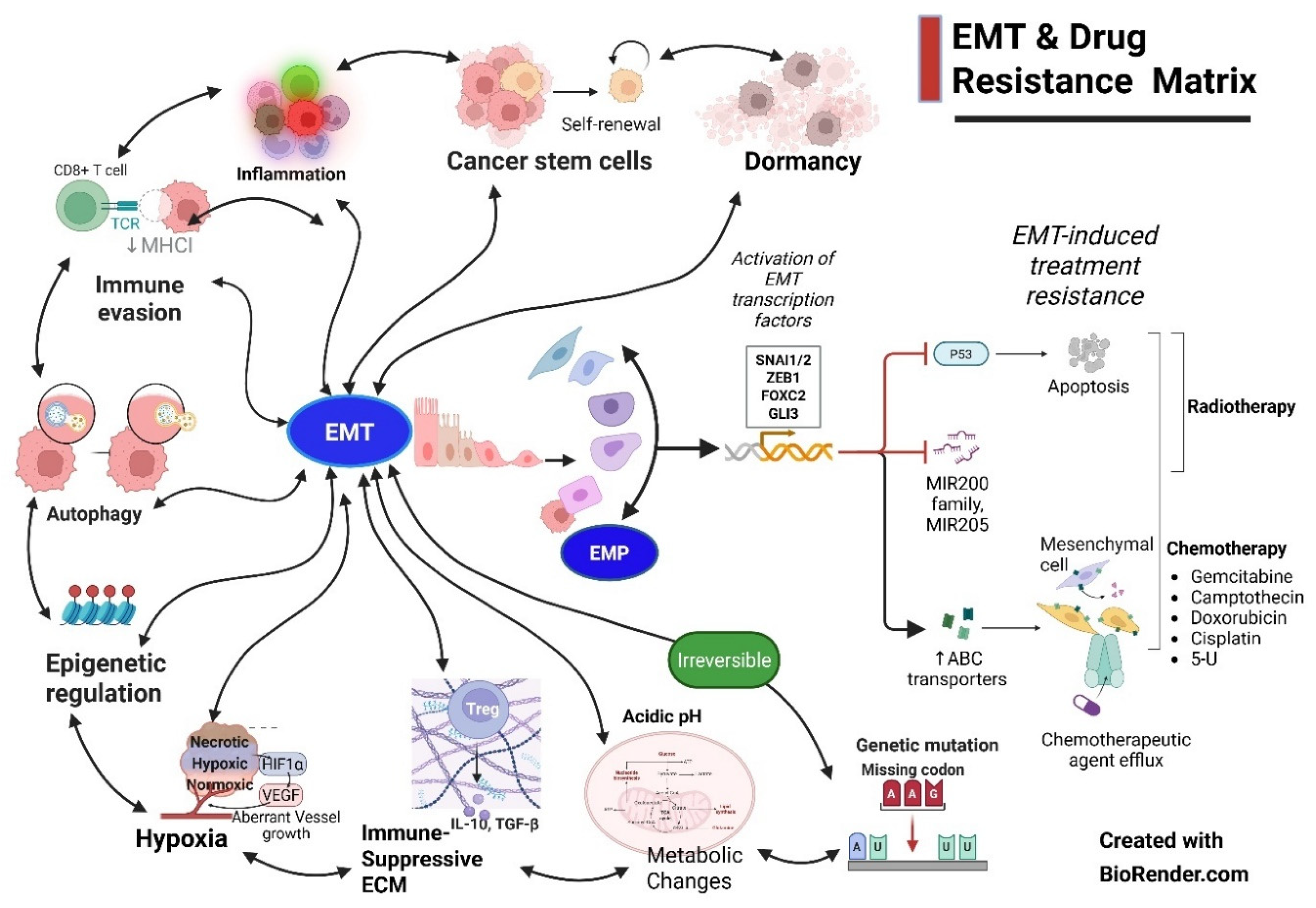

- 1.2.1 Key signaling pathways play critical roles in driving EMT processes. Among the most significant is the Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway, which is a well-established inducer of EMT in various cancer types. TGF-β activates Smad proteins that enter the nucleus and regulate the transcription of EMT-related genes, subsequently leading to cytoskeletal reorganization and increased cellular motility [34,35].

- 1.2.2 Transcription factors, particularly those categorized as EMT-TFs (transcription factors), are instrumental in orchestrating the EMT process. The Snail family (SNAI1 and SNAI2), ZEB family (ZEB1 and ZEB2), and TWIST1 are prominent transcriptional regulators that inhibit the expression of E-cadherin and promote mesenchymal gene expression [38,39]. These EMT-TFs initiate the transcriptional changes required for EMT and are subject to extensive post-translational modifications, which can alter their activity and stability, thereby influencing the efficiency and timing of the transition [40]. For example, phosphorylation and ubiquitination can modulate the activity of these factors, enhancing or repressing their role in EMT [41]. Created with BioRender.com.

- 1.2.3 Role of MicroRNA: MicroRNA-200c (miR-200c) is increasingly recognized as a crucial miRNA molecule that plays a spectrum of roles in all aspects of EMT and cancer cell evolution. It has context-dependent actions where, in certain situations, it enhances apoptosis, tumor inhibition, reduces cellular inflammation, suppresses pyroptosis, etc, and in other situations, it has a pivotal complex role in promoting EMT. It can also play a role in modulating TME by M2 phenotypic macrophage polarization, density of TILs, expression of PDL1, CTLs exhaustion, and cancer cell exosomal load. MiR-200c can thus act as both a biomarker and a therapeutic target [10,42,43].

2. Mechanisms of MET

3. EMT-MET Spectrum: Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity (EMP) Characterization

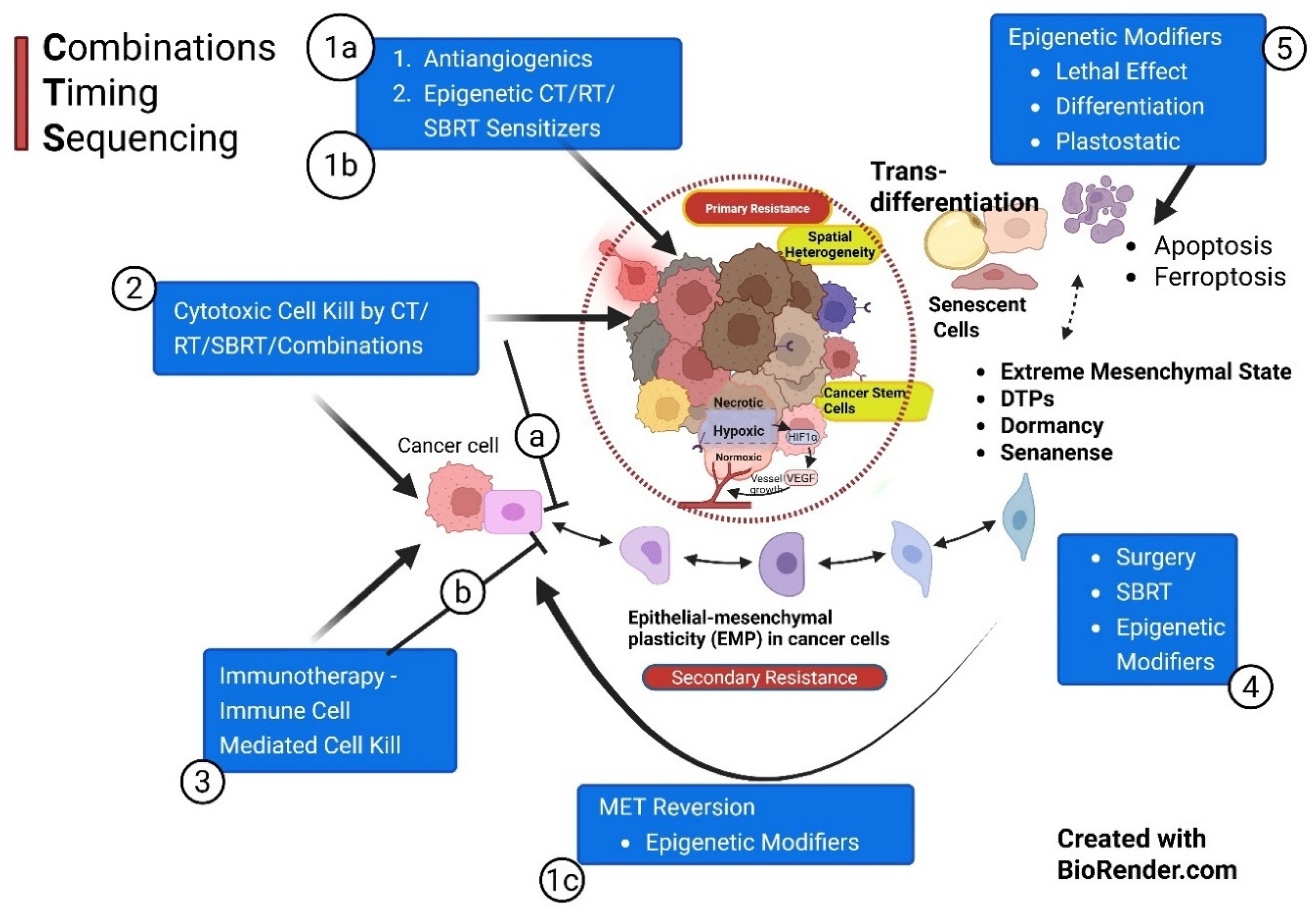

4. Targeting EMT-MET Double-Bind – Combinations, Timing and Sequencing (CTS) Strategy

4.1. Inducing Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition (MET) – Clinical Imperativeness and an Opportunity?

4.2. Epigenetic Modifiers

- Metformin improves insulin sensitivity, modulates metabolism, and inhibits EMT and reduces the metastatic potential of cervical cancer cells via inhibition of mTOR and TGF-β signaling [82].

-

Salinomycin reverses doxorubicin-induced EMT by downregulating mesenchymal markers and upregulating E-cadherin, and restores chemosensitivity [83].Salinomycin, an AMPK inhibitor, can cause mitochondrial dysfunction and induce autophagy to cause metabolic reprogramming and overcome CSCs' RT/CT resistance [84].

4.3. Two Concepts and One Strategy

4.4. A Unified Perspective: Combinations, Timing, and Sequencing (CTS) Strategy

4.5. Targeting Primary Mechanisms of EMP Resistance Network

4.6. Combinations, Timing, and Sequencing Strategy

5. Limitations

6. Summary

7. Future Research Directions to Unravel Complexities and Improve Therapeutic Strategies

References

- Kim-Fuchs C, Le C, Pimentel M, Shackleford D, Ferrari D, Angst E, et al. Chronic stress accelerates pancreatic cancer growth and invasion: a critical role for beta-adrenergic signaling in the pancreatic microenvironment. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;40:40-47. [CrossRef]

- Fong M, Zhou W, Liu L, Alontaga A, Chandra M, Ashby J, et al. Breast-cancer-secreted mir-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(2):183-194. [CrossRef]

- Al-bataineh M, Alzamora R, Ohmi K, Ho P, Marciszyn A, Gong F, et al. Aurora kinase a activates the vacuolar h+-atpase (v-atpase) in kidney carcinoma cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(11):F1216-F1228. [CrossRef]

- Gatenby RA, Brown JS. The Evolution and Ecology of Resistance in Cancer Therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020 Nov 2;10(11):a040972. [CrossRef]

- Lu W, Kang Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Dev Cell. 2019 May 6;49(3):361-374. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zhang Y, Wu X, Xu F, Ma H, Wu M, et al. Targeting ferroptosis pathway to combat therapy resistance and metastasis of cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:909821. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson R, Novosyadlyy R, Fierz Y, Alikhani N, Sun H, Yakar S, et al. Hyperinsulinemia enhances c-myc-mediated mammary tumor development and advances metastatic progression to the lung in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(1):R14. [CrossRef]

- Eslami-S Z, Cortés-Hernández L, Glogovitis I, Antunes-Ferreira M, D'Ambrosi S, Kurma K, et al. In vitro cross-talk between metastasis-competent circulating tumor cells and platelets in colon cancer: a malicious association during the harsh journey in the blood. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1209846. [CrossRef]

- Kogure A, Yoshioka Y, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles in cancer metastasis: potential as therapeutic targets and materials. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4463. [CrossRef]

- Gregory P, Bracken C, Smith E, Bert A, Wright J, Roslan S, et al. An autocrine tgf-β/zeb/mir-200 signaling network regulates establishment and maintenance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(10):1686-1698. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Du J, Mi Y, Li T, Gong Y, Ouyang H, et al. Long non-coding rnas contribute to the inhibition of proliferation and emt by pterostilbene in human breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:629. [CrossRef]

- Wei L, Li K, Pang X, Guo B, Min S, Huang Y, et al. Leptin promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer via the upregulation of pyruvate kinase M2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):148. [CrossRef]

- Feldker N, Ferrazzi F, Schuhwerk H, Widholz S, Guenther K, Frisch I, et al. Genome-wide cooperation of emt transcription factor zeb1 with yap and ap-1 in breast cancer. EMBO J. 2020;39(17):e103209. [CrossRef]

- G. Z. Qiu, M. Z. Jin, J. X. Dai, W. Sun, J. H. Feng, W. L. Jin, Tumorin the Hypoxic Niche: The Emerging Concept and Associated Therapeutic Strategies G. Z. Qiu, M. Z. Jin, J. X. Dai, W. Sun, J. H. Feng, W. L. Jin, Tumor in the Hypoxic Niche: The Emerging Concept and Associated Therapeutic Strategies, Trends Pharmacol Sci 38(8)(2017) 669–686. [CrossRef]

- Montemagno C and Pagès G (2020) Resistance to Antiangiogenic Therapies: A Mechanism Depending on the Time of Exposure to the Drugs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:584. [CrossRef]

- Kathrine S. R, Thomas H L Y, Michail S. Chemoradiotherapy in Cancer Treatment: Rationale and Clinical Applications. Anticancer Research Jan 2021, 41 (1) 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Clarke J M, Hurwitz H I. Understanding and targeting resistance to antiangiogenic therapies. J Gastrointest Oncol 2013;4(3):253-263. [CrossRef]

- Ye X, Weinberg R. Epithelial--mesenchymal plasticity: a central regulator of cancer progression. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(11):675-686. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Carmona M, Bourcy M, Lesage J, Leroi N, Syne L, Blacher S, et al. Soluble factors regulated by epithelial--mesenchymal transition mediate tumour angiogenesis and myeloid cell recruitment. J Pathol. 2015;236(4):491-504. [CrossRef]

- Haibe Y, Kreidieh M, El Hajj H et al. Resistance Mechanisms to Antiangiogenic Therapies in Cancer. Front. Oncol. (2020) 10:221. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub NM, Jaradat SK, Al-Shami KM, Alkhalifa AE. Targeting Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives of Novel Antiangiogenic Approaches. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Feb 25;13:838133. [CrossRef]

- Montemagno C and Pagès G (2020) Resistance to Antiangiogenic Therapies: A Mechanism Depending on the Time of Exposure to the Drugs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:584. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wegiel B, Vuerich M, Daneshmandi Sand Seth P (2018) Metabolic Switch in the Tumor Microenvironment Determi[nes Immune Responses to Anticancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. (2018) 8:284. [CrossRef]

- Weihua Wu, Shimin Zhao, Metabolic changes in Cancer: beyond the Warburg effect, Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica, Volume 45, Issue 1, January 2013, Pages 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):211-218. Erratum in: Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):287. Erratum in: Trends Biochem Sci. 2016 Mar;41(3):287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.004. [CrossRef]

- Liaghat M, Ferdousmakan S, Mortazavi SH, Yahyazadeh S, Irani A, Banihashemi S, Seyedi Asl FS, Akbari A, Farzam F, Aziziyan F, Bakhtiyari M, Arghavani MJ, Zalpoor H, Nabi-Afjadi M. The impact of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) induced by metabolic processes and intracellular signaling pathways on chemo-resistance, metastasis, and recurrence in solid tumors. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Dec 2;22(1):575. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is regulated at post-transcriptional levels by transforming growth factor-β signaling during tumor progression. Cancer Sci. 2015 May;106(5):481-8. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K., Karin, M. NF-κB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 309–324 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Horta CA, Doan K, Yang J. Mechanotransduction pathways in regulating epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2023 Dec;85:102245. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Yu X, Li J. Manipulation of immune‒vascular cross-talk: new strategies towards cancer treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020 Nov;10(11):2018-2036. [CrossRef]

- Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004 Aug;21(2):137-48. PMID: 15308095. [CrossRef]

- Sistigu A, Di Modugno F, Manic G, Nisticò P. Deciphering the loop of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, inflammatory cytokines and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017 Aug;36:67-77. [CrossRef]

- Romeo E, Caserta CA, Rumio C, Marcucci F. The Vicious Cross-Talk between Tumor Cells with an EMT Phenotype and Cells of the Immune System. Cells. 2019 May 15;8(5):460. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Zhu Y, Tan J, Meng X, Xie H, Wang R. Lysyl oxidase promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition during paraquat-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12(2):499-507. [CrossRef]

- Miyake Y, Nagaoka Y, Okamura K, Takeishi Y, Tamaoki S, Hatta M. SNAI2 is induced by transforming growth factor-β1, but is not essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. Exp Ther Med. 2021 Oct;22(4):1124. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh A, Vasaikar S, Tomczak K, Tripathi S, Hollander P, Arslan E, et al. Identification of emt signaling cross-talk and gene regulatory networks by single-cell rna sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(19):e2102050118. [CrossRef]

- Frey P, Devisme A, Schrempp M, Andrieux G, Boerries M, Hecht A. Canonical bmp signaling executes epithelial-mesenchymal transition downstream of snail1. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(4):1019. [CrossRef]

- Yi JH, Zhang ZC, Zhang MB, He X, Lin HR, Huang HW, Dai HB, Huang YW. Role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the pulmonary fibrosis induced by paraquat in rats. World J Emerg Med. 2021;12(3):214-220. [CrossRef]

- Wang JQ, Yan FQ, Wang LH, Yin WJ, Chang TY, Liu JP, Wu KJ. Identification of new hypoxia-regulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition marker genes labeled by H3K4 acetylation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2020 Feb;59(2):73-83. [CrossRef]

- Grasset EM, Dunworth M, Sharma G, Loth M, Tandurella J, Cimino-Mathews A, Gentz M, Bracht S, Haynes M, Fertig EJ, Ewald AJ. Triple-negative breast cancer metastasis involves complex epithelial-mesenchymal transition dynamics and requires vimentin. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Aug 3;14(656):eabn7571.

- Boareto M, Jolly M, Goldman A, Pietilä M, Mani S, Sengupta S, et al. Notch-jagged signalling can give rise to clusters of cells exhibiting a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype. J R Soc Interface. 2016;13(118):20151106. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, N.; Huang, T.; Shen, N. MicroRNA-200c in Cancer Generation, Invasion, and Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 710. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Hung GC, Meng S, Evans R, Xu J. LncRNA MALAT1 Regulates Hyperglycemia Induced EMT in Keratinocyte via miR-205. Noncoding RNA. 2023 Feb 11;9(1):14. [CrossRef]

- Chang H, Liu Y, Xue M, Liu H, Du S, Zhang L, et al. Synergistic action of master transcription factors controls epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(6):2514-2527. [CrossRef]

- Tong J, Shen Y, Zhang Z, Hu Y, Zhang X, Han L. Apigenin inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human colon cancer cells through nf-κb/snail signaling pathway. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(5):BSR20190452. [CrossRef]

- Subbalakshmi AR, Sahoo S, McMullen I, Saxena AN, Venugopal SK, Somarelli JA, Jolly MK. KLF4 Induces Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition (MET) by Suppressing Multiple EMT-Inducing Transcription Factors. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Oct 13;13(20):5135. [CrossRef]

- Johnson KS, Hussein S, Chakraborty P, Muruganantham A, Mikhail S, Gonzalez G, Song S, Jolly MK, Toneff MJ, Benton ML, Lin YC, Taube JH. CTCF Expression and Dynamic Motif Accessibility Modulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Gene Expression. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jan 1;14(1):209. [CrossRef]

- Škarková A, Bizzarri M, Janoštiak R, Mašek J, Rosel D, Brábek J. Educate, not kill: treating cancer without triggering its defenses. Trends Mol Med. 2024 Jul;30(7):673-685. [CrossRef]

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Historical Overview. Transl Oncol. 2020 Jun;13(6):100773. [CrossRef]

- Liao TT, Yang MH. Revisiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12096in cancer metastasis: the connection between epithelial plasticity and stemness. Mol Oncol. 2017 Jul;11(7):792-804. [CrossRef]

- Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, Ishi H, Beppu T, Nakamori S, Baba H, Mori M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer development and its clinical significance. Cancer Sci. 2010 Feb;101(2):293-9. [CrossRef]

- Moustakas A, de Herreros AG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Mol Oncol. 2017 Jul;11(7):715-717. [CrossRef]

- Pensotti A, Bizzarri M, Bertolaso M. The phenotypic reversion of cancer: Experimental evidences on cancer reversibility through epigenetic mechanisms (Review). Oncol Rep. 2024 Mar;51(3):48. [CrossRef]

- Williams ED, Gao D, Redfern A, Thompson EW. Controversies around epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019 Dec;19(12):716-732. [CrossRef]

- Addison JB, Voronkova MA, Fugett JH, Lin CC, Linville NC, Trinh B, Livengood RH, Smolkin MB, Schaller MD, Ruppert JM, Pugacheva EN, Creighton CJ, Ivanov AV. Functional Hierarchy and Cooperation of EMT Master Transcription Factors in Breast Cancer Metastasis. Mol Cancer Res. 2021 May;19(5):784-798. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Kuang LY, He F, Du LL, Li QL, Sun W, Zhou YM, Li XM, Li XY, Chen DJ. The Role and Molecular Mechanism of Long Nocoding RNA-MEG3 in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Reprod Sci. 2018 Dec;25(12):1619-1628. [CrossRef]

- Aiello NM, Maddipati R, Norgard RJ, Balli D, Li J, Yuan S, Yamazoe T, Black T, Sahmoud A, Furth EE, Bar-Sagi D, Stanger BZ. EMT Subtype Influences Epithelial Plasticity and Mode of Cell Migration. Dev Cell. 2018 Jun 18;45(6):681-695.e4. [CrossRef]

- Knutsen E, Das Sajib S, Fiskaa T, Lorens J, Gudjonsson T, Mælandsmo GM, Johansen SD, Seternes OM, Perander M. Identification of a core EMT signature that separates basal-like breast cancers into partial- and post-EMT subtypes. Front Oncol. 2023 Dec 4;13:1249895. [CrossRef]

- Puram SV, Tirosh I, Parikh AS, Patel AP, Yizhak K, Gillespie S, Rodman C, Luo CL, Mroz EA, Emerick KS, Deschler DG, Varvares MA, Mylvaganam R, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Rocco JW, Faquin WC, Lin DT, Regev A, Bernstein BE. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Primary and Metastatic Tumor Ecosystems in Head and Neck Cancer. Cell. 2017 Dec 14;171(7):1611-1624.e24. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso IIV, Rosa MN, Moreno DA, Tufi LMB, Ramos LP, Pereira LAB, Silva L, Galvão JMS, Tosi IC, Lengert AVH, Da Cruz MC, Teixeira SA, Reis RM, Lopes LF, Pinto MT. Cisplatin-resistant germ cell tumor models: An exploration of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulator SLUG. Mol Med Rep. 2024 Dec;30(6):228. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Skomorovska Y, Song J, Bowler E, Harris R, Ravasz M, Bai S, Ayati M, Tamai K, Koyuturk M, Yuan X, Wang Z, Wang Y, Ewing RM. ELF3 is an antagonist of oncogenic-signalling-induced expression of EMT-TF ZEB1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(1):90-100. [CrossRef]

- Sugandha Bhatia, James Monkman, Alan Kie Leong Toh, Shivashankar H. Nagaraj, Erik W. Thompson; Targeting epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity in cancer: clinical and preclinical advances in therapy and monitoring. Biochem J 1 October 2017; 474 (19): 3269–3306. [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo Martin Y, Park D, Ramachandran A, Ombrato L, Calvo F, Chakravarty P, Spencer-Dene B, Derzsi S, Hill CS, Sahai E, Malanchi I. Mesenchymal Cancer Cell-Stroma Crosstalk Promotes Niche Activation, Epithelial Reversion, and Metastatic Colonization. Cell Rep. 2015 Dec 22;13(11):2456-2469. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.W., Redfern, A.D., Brabletz, S. et al. EMT and cancer: what clinicians should know. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 22, 711–733 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Nezami, M. , Hager, S. and Garner, J. (2015) EMT and Anti-EMT Strategies in Cancer. Journal of Cancer Therapy, 6, 1013-1019. [CrossRef]

- Kwon M, Jung H, Nam GH, Kim IS. The right Timing, right combination, right sequence, and right delivery for Cancer immunotherapy. J Control Release. 2021 Mar 10;331:321-334. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tilló E, Lázaro A, Torrent R, et al. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and induces an EMT by recruiting the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1. Oncogene. 2010;29(24):3490–3500. [CrossRef]

- Connolly EP, Sun Y, Hei TK. Eribulin mesylate promotes a mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) and effectively radio-sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9 Suppl):P6-02-04. [CrossRef]

- Meidhof S, Brabletz S, Stemmler MP, et al. ZEB1-associated drug resistance in cancer cells is reversed by the class I HDAC inhibitor mocetinostat. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(6):832–847. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri M, Mohamed GA, Mohamed Saleem MA, Ognjenovic NB, Lu H, Kolling FW, Wilkins OM, Das S, LaCroix IS, Nagaraj SH, Muller KE, Gerber SA, Miller TW, Pattabiraman DR. Pharmacological induction of chromatin remodeling drives chemosensitization in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Apr 16;5(4):101504. [CrossRef]

- David CJ, Huang YH, Chen M, Su J, Zou Y, Bardeesy N, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Massagué J. TGF-β Tumor Suppression through a Lethal EMT. Cell. 2016 Feb 25;164(5):1015-30. [CrossRef]

- Ishay-Ronen D, Diepenbruck M, Kalathur RKR, Sugiyama N, Tiede S, Ivanek R, Bantug G, Morini MF, Wang J, Hess C, Christofori G. Gain Fat-Lose Metastasis: Converting Invasive Breast Cancer Cells into Adipocytes Inhibits Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2019 Jan 14;35(1):17-32.e6. [CrossRef]

- Voon DC, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. The EMT spectrum and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Oncol. 2017 Jul;11(7):878-891. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida T, Ozawa Y, Kimura T, et al. Eribulin mesilate suppresses experimental metastasis of breast cancer cells by reversing phenotype from EMT to MET. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(6):1497–1505.

- Lim HI, Yamamoto J, Inubushi S, Nishino H, Tashiro Y, Sugisawa N, Han Q, Sun YU, Choi HJ, Nam SJ, Kim MB, Lee JS, Hozumi C, Bouvet M, Singh SR, Hoffman RM. A Single Low Dose of Eribulin Regressed a Highly Aggressive Triple-negative Breast Cancer in a Patient-derived Orthotopic Xenograft Model. Anticancer Res. 2020 May;40(5):2481-2485. [CrossRef]

- Pensotti A, Bizzarri M, Bertolaso M. The phenotypic reversion of cancer: Experimental evidences on cancer reversibility through epigenetic mechanisms (Review). Oncol Rep. 2024 Mar;51(3):48. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tilló E, Lázaro A, Torrent R, et al. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and induces an EMT by recruiting the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1. Oncogene. 2010;29(24):3490–3500. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Shen GN, Jung YS, et al. Antitumor effect of novel small chemical inhibitors of Snail-p53 binding in K-Ras-mutated cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(32):4576–4587. [CrossRef]

- Vistain LF, Yamamoto N, Rathore R, Cha P, Meade TJ. Targeted Inhibition of Snail Activity in Breast Cancer Cells by Using a Co(III) -Ebox Conjugate. Chembiochem. 2015 Sep 21;16(14):2065-72. [CrossRef]

- Takemura, K.; Ikeda, K.; Miyake, H.; Sogame, Y.; Yasuda, H.; Okada, N.; Iwata, K.; Sakagami, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Itoh, Y.; et al. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Suppression by ML210 Enhances Gemcitabine Anti-Tumor Effects on PDAC Cells. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 70. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya AM, Sun Z, Ayat N, Schilb A, Liu X, Jiang H, Sun D, Scheidt J, Qian V, He S, Gilmore H, Schiemann WP, Lu ZR. Systemic Delivery of Tumor-Targeting siRNA Nanoparticles against an Oncogenic LncRNA Facilitates Effective Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2019 Mar 20;30(3):907-919. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Hao, M. Metformin Inhibits TGF-β1-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition via PKM2 Relative-mTOR/p70s6k Signaling Pathway in Cervical Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Liang C, Xue F, Chen W, Zhi X, Feng X, Bai X, Liang T. Salinomycin decreases doxorubicin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the β-catenin/TCF complex association via FOXO3a activation. Oncotarget. 2015 Apr 30;6(12):10350-65. [CrossRef]

- Lyakhovich A, Lleonart ME. Bypassing Mechanisms of Mitochondria-Mediated Cancer Stem Cells Resistance to Chemo- and Radiotherapy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:171634. [CrossRef]

- Cañadas I, Rojo F, Taus Á, Arpí O, Arumí-Uría M, Pijuan L, Menéndez S, Zazo S, Dómine M, Salido M, Mojal S, García de Herreros A, Rovira A, Albanell J, Arriola E. Targeting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition with Met inhibitors reverts chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 Feb 15;20(4):938-50. [CrossRef]

- Hill L, Browne G, Tulchinsky E. ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop: at the crossroads of signal transduction in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013 Feb 15;132(4):745-54. [CrossRef]

- Bhat GR, Sethi I, Sadida HQ, Rah B, Mir R, Algehainy N, Albalawi IA, Masoodi T, Subbaraj GK, Jamal F, Singh M, Kumar R, Macha MA, Uddin S, Akil ASA, Haris M, Bhat AA. Cancer cell plasticity: from cellular, molecular, and genetic mechanisms to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024 Mar;43(1):197-228. [CrossRef]

- Jiang M, Wang J, Li Y, Zhang K, Wang T, Bo Z, Lu S, Rodríguez RA, Wei R, Zhu M, Nicot C, Sethi G. EMT and cancer stem cells: Drivers of therapy resistance and promising therapeutic targets. Drug Resist Updat. 2025 Nov;83:101276. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Mainardi S, Lieftink C, Velds A, de Rink I, Yang C, Kuiken HJ, Morris B, Edwards F, Jochems F, van Tellingen O, Boeije M, Proost N, Jansen RA, Qin S, Jin H, Koen van der Mijn JC, Schepers A, Venkatesan S, Qin W, Beijersbergen RL, Wang L, Bernards R. Targeting of vulnerabilities of drug-tolerant persisters identified through functional genetics delays tumor relapse. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Mar 19;5(3):101471. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Hong W, Wei X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Sep 8;15(1):129. [CrossRef]

- Celià-Terrassa T, Kang Y. How important is EMT for cancer metastasis? PLoS Biol. 2024 Feb 7;22(2):e3002487. [CrossRef]

- Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Normalisation of the vasculature is needed to treat cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev. 2011 Jul;91(3):1071-121. [CrossRef]

- Jain RK. Normalisation of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005 Jan 7;307(5706):58-62. [CrossRef]

- Yang T, Xiao H, Liu X, Wang Z, Zhang Q, Wei N, Guo X. Vascular Normalization: A New Window Opened for Cancer Therapies. Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 12;11:719836. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Zhao Q, Zheng Z, Liu S, Meng L, Dong L, Jiang X. Vascular normalization in immunotherapy: A promising mechanisms combined with radiotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Jul;139:111607. [CrossRef]

- Magnussen AL, Mills IG. Vascular normalisation as the stepping stone into tumour microenvironment transformation. Br J Cancer. 2021 Aug;125(3):324-336. [CrossRef]

- Guo Z, Lei L, Zhang Z, Du M, Chen Z. The potential of vascular normalization for sensitization to radiotherapy. Heliyon. 2024 Jun 8;10(12):e32598. [CrossRef]

- Appleton, E.; Hassan, J.; Hak, C.C.W.; Sivamanoharan, N.; Wilkins, A.; Samson, A.; Ono, M.; Harrington, K.J.; Melcher, A.; Wennerberg, E. Kickstarting Immunity in Cold Tumours: Localised Tumour Therapy Combinations With Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 754436. [CrossRef]

- Shibamoto Y, Miyakawa A, Otsuka S, Iwata H. Radiobiology of hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy: what are the optimal fractionation schedules? J Radiat Res. 2016 Aug;57 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i76-i82. [CrossRef]

- Chen HHW, Kuo MT. Improving radiotherapy in cancer treatment: Promises and challenges. Oncotarget. 2017 Jun 8;8(37):62742-62758. [CrossRef]

- Heldin CH, Rubin K, Pietras K, Ostman A. High interstitial fluid pressure - an obstacle in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004 Oct;4(10):806-13. [CrossRef]

- Lecoultre M, Chliate S, Espinoza FI, Tankov S, Dutoit V, Walker PR. Radio-chemotherapy of glioblastoma cells promotes phagocytosis by macrophages in vitro. Radiother Oncol. 2024 Jan;190:110049. [CrossRef]

- Ura B, Di Lorenzo G, Romano F, Monasta L, Mirenda G, Scrimin F, Ricci G. Interstitial Fluid in Gynecologic Tumors and Its Possible Application in the Clinical Practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Dec 12;19(12):4018. [CrossRef]

- Feng K, Zhang X, Li J, Han M, Wang J, Chen F, Yi Z, Di L, Wang R. Neoantigens combined with in situ cancer vaccination induce personalized immunity and reshape the tumor microenvironment. Nat Commun. 2025 May 31;16(1):5074. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N., Wang, X., Wang, Z. et al. Nanomaterials-driven in situ vaccination: a novel frontier in tumor immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 18, 45 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kerr MD, McBride DA, Chumber AK, Shah NJ. Combining therapeutic vaccines with chemo- and immunotherapies in the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2021 Jan;16(1):89-99. [CrossRef]

- Bangarh R, Saini RV, Saini AK, Singh T, Joshi H, Ramniwas S, Shahwan M, Tuli HS. Dynamics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity driving cancer drug resistance. Cancer Pathog Ther. 2024 Jul 6;3(2):120-128. [CrossRef]

- Kurrey NK, Jalgaonkar SP, Joglekar AV, Ghanate AD, Chaskar PD, Doiphode RY, Bapat SA. Snail and slug mediate radioresistance and chemoresistance by antagonizing p53-mediated apoptosis and acquiring a stem-like phenotype in ovarian cancer cells. Stem Cells. 2009 Sep;27(9):2059-68. [CrossRef]

- Fontana R, Mestre-Farrera A, Yang J. Update on Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2024 Jan 24;19:133-156. [CrossRef]

- Maria L. Lotsberg. Decoding cancer’s camouflage: epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan D, Balakrishnan R, Chauhan A, Kumar J, Girija DM, Shrestha R, Shrestha R, Subbarayan R. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: Insights Into Therapeutic Targets and Clinical Implications. MedComm (2020). 2025 Aug 29;6(9):e70333. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Xue X, Pang M, Yu L, Qian J, Li X, Tian M, Lyu A, Lu C, Liu Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer: signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. MedComm (2020). 2024 Aug 1;5(8):e659. [CrossRef]

- Park J, Choi J, Cho I, Sheen YY. Radiotherapy-induced oxidative stress and fibrosis in breast cancer are suppressed by vactosertib, a novel, orally bioavailable TGF-β/ALK5 inhibitor. Sci Rep. 2022 Sep 27;12(1):16104. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Han Y, Jin Y, He Q, Wang Z. The Advances in Epigenetics for Cancer Radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 18;23(10):5654. [CrossRef]

- Sordo-Bahamonde, C.; Lorenzo-Herrero, S.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, A.P.; Martínez-Pérez, A.; Rodrigo, J.P.; García-Pedrero, J.M.; Gonzalez, S. Chemo-Immunotherapy: A New Trend in Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2023, 15, 2912. [CrossRef]

- Lussier, D.M.; Alspach, E.; Ward, J.P.; Miceli, A.P.; Runci, D.; White, J.M.; Mpoy, C.; Arthur, C.D.; Kohlmiller, H.N.; Jacks, T.; et al. Radiation-induced neoantigens broaden the immunotherapeutic window of cancers with low mutational loads. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2102611118. [CrossRef]

- Breen WG, Leventakos K, Dong H, Merrell KW. Radiation and immunotherapy: emerging mechanisms of synergy. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Nov;12(11):7011-7023. [CrossRef]

- He K, Barsoumian HB, Sezen D, Puebla-Osorio N, Hsu EY, Verma V, Abana CO, Chen D, Patel RR, Gu M, Cortez MA, Welsh JW. Pulsed Radiation Therapy to Improve Systemic Control of Metastatic Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 23;11:737425. [CrossRef]

- Spaas M, Lievens Y. Is the Combination of Immunotherapy and Radiotherapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer a Feasible and Effective Approach? Front Med (Lausanne). 2019 Nov 7;6:244. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, Weng L, Wu Q, Zhang J, Zhao P, Fang L, Shi Y, Wang P. Emerging phagocytosis checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Mar 7;8(1):104. [CrossRef]

- Joshi S, Durden DL. Combinatorial Approach to Improve Cancer Immunotherapy: Rational Drug Design Strategy to Simultaneously Hit Multiple Targets to Kill Tumor Cells and to Activate the Immune System. J Oncol. 2019 Feb 3;2019:5245034. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zhang B. Extracellular matrix stiffness: mechanisms in tumor progression and therapeutic potential in cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025 Apr 10;14(1):54. [CrossRef]

- Short S, Fielder E, Miwa S, von Zglinicki T. Senolytics and senostatics as adjuvant tumour therapy. EBioMedicine. 2019 Mar;41:683-692. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, V.J.; Saleh, T.; Gewirtz, D.A. Senolytics for Cancer Therapy: Is All that Glitters Really Gold? Cancers 2021, 13, 723. [CrossRef]

- Marino P, Mininni M, Deiana G, Marino G, Divella R, Bochicchio I, Giuliano A, Lapadula S, Lettini AR, Sanseverino F. Healthy Lifestyle and Cancer Risk: Modifiable Risk Factors to Prevent Cancer. Nutrients. 2024 Mar 11;16(6):800. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Jiang A, Tang F, Duan M, Li B. Drug-induced tolerant persisters in tumor: mechanism, vulnerability and perspective implication for clinical treatment. Mol Cancer. 2025 May 24;24(1):150. [CrossRef]

- Guo F, Kerrigan B, Yang D, Hu L, Shmulevich I, Sood A, et al. Post-transcriptional regulatory network of epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:19. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto M, Sakane K, Tominaga K, Gotoh N, Niwa T, Kikuchi Y, et al. Intratumoral bidirectional transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(6):1210-1222. [CrossRef]

- Chen T, You Y, Jiang H, Wang ZZ. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): A biological process in the development, stem cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2017 Dec;232(12):3261-3272. [CrossRef]

- Yeh YH, Wang SW, Yeh YC, Hsiao HF, Li TK. Rhapontigenin inhibits TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and is not associated with HIF-1α degradation. Oncol Rep. 2016 May;35(5):2887-95. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Escudero, J.; Berlana-Galán, P.; Guerra-Paes, E.; Torre-Cea, I.; Marcos-Zazo, L.; Carrera-Aguado, I.; Cáceres-Calle, D.; Sánchez-Juanes, F.; Muñoz-Félix, J.M. Vascular Disruption Therapy as a New Strategy for Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10085. [CrossRef]

- Sim HJ, Kim MR, Song MS, Lee SY. Kv3.4 regulates cell migration and invasion through TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in A549 cells. Sci Rep. 2024 Jan 28;14(1):2309. [CrossRef]

- Jia D, Jolly MK, Boareto M, Parsana P, Mooney SM, Pienta KJ, Levine H, Ben-Jacob E. OVOL guides the epithelial-hybrid-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2015 Jun 20;6(17):15436-48. [CrossRef]

- Mishra VK, Johnsen SA. Targeted therapy of epigenomic regulatory mechanisms controlling the epithelial to mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Cell Tissue Res. 2014 Jun;356(3):617-30. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Dai F, Feng L, Zou H, Feng L, Xu M. Communication Between Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity and Cancer Stem Cells: New Insights Into Cancer Progression. Front Oncol. 2021 Apr 21;11:617597. [CrossRef]

- Franssen L, Chaplain M. A mathematical multi-organ model for bidirectional epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in the metastatic spread of cancer. bioRxiv. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lin WH, Chang YW, Hong MX, Hsu TC, Lee KC, Lin C, Lee JL. STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727 and Tyr705 differentially regulates the EMT-MET switch and cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2021 Jan;40(4):791-805. [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.; Arakeri, G.; Basavalingaiah S, A. Combination, Timing, and Sequencing (CTS) Therapy Strategy for Unmasking Cancer for Immunotherapy. Preprints 2024, 2024111830. [CrossRef]

- Giordanengo, L.; Proment, A.; Botta, V.; Picca, F.; Munir, H.M.W.; Tao, J.; Olivero, M.; Taulli, R.; Bersani, F.; Sangiolo, D.; et al. Shifting Shapes: The Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition as a Driver for Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6353. [CrossRef]

| Phases in Sequence | Strategy & Mechanisms |

Timing | Objective | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I a |

Prepriming therapy Primarily Vascular Normalization a. With AAGs / Small molecules to initiate vascular normalization & hypoxia targeting (3 weeks on 3 weeks off) |

Start: Day 0 |

1. Normalization of vascular structure is Essential for effective subsequent chemo-immunotherapy delivery. It also improves sensitivity to RT/SBRT. 2. Improve by adding newer strategies/drugs for vascular normalization. |

Vascular Normalization: a. Goel S et al, 2011 [92] b. Jain RK et al 2005 [93] c. Ting Yang et al, 2021 [94] d. Zijing Liu, et al 2021 [95] e. Magnussen AL et al, 2021. [96] f. Zhili Guo, et al, 2024. [97] |

| Phase 1b |

Prepriming therapy: Primarily, Epigenetic Therapy as a CT/RT sensitizer a. With epigenetic modifiers for subsequent CT/ RT in Phase II. Eg. Eribulin b. Reducing Drug Efflux |

Starts in the 1st week of AAGs (> Day 2) |

1. Anticancer standard therapy has been RT and CT for decades, evolving with Maximum Tolerated Doses (MTD). EMs change the landscape by reversing epigenetic changes, sensitizing cancer cells for CT/RT. 2. EMs help achieve effective drug concentration in cancer cells 3. Prevent EMT transformation and ensuing stemness |

Epigenetic Modifiers: a. Guo H et al., 2025 [42]. b. Cardoso IIV et al. 2024 [60] c. Liu D et al, 2019 [61] d. Bagheri M et al., 2024 [70] b. Huang Y et al., 2022. [90] d. Connolly EP et al., 2015 [68] e. Meidhof S, et al., 2015 [69] f. Yoshida T et al., 2014, [74] g. HYE IN LIM et al., 2020, [75] |

| Phase 1c |

Prepriming therapy: Primarily, Epigenetic Therapy as MET Inducer – MET Reversion Push the cells to EMT cells to gain Epithelial features using the MET pathway |

Before the start of CT/RT – schedule to be optimized | This facilitates Mesenchymal cells to acquire more susceptible epithelial characteristics and reduce stemness.. |

MET Iducers .KLF4: Subbalakshmi A et al, 2021 [46] .E-cadherin & TGFβ: Johnson K, et al., 2022 [47] .Target EMT signaling: Ribatti et al, 2020 [49] |

| Phase II |

Priming therapy: Primarily, selective cancer cell kill and interstitial pressure reduction. a. MTD strategy: Cytotoxic therapy and activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes to “unmask” the cancer for concurrent or subsequent immunotherapy even in cold and PDL1-negative tumors. b. Professional Phagocytosis c. Decrease ISP d. Antigenicity & Adjuvanticity f. Lymphatic normalization g. In situ vaccination h. Nanoparticle therapy i. In vitro vaccine therapy j. Epigenetic therapy (ET) |

Start CT/RT (SBRT) in the 1st week of AAGs (> Day 2) | Cancer cell lysis (preferably by ICD); Create waves of neoantigen generation; Immune suppressive/exhausted cell depletion in TME; decrease ISP; enhanced vascularity (vascular promotion), improved lymphatic drainage for neoantigen presentation in the lymph nodes, and reinvigorating the Immunity cycle; enhanced fresh TME CTLs infiltration. | .EMP Prevention: Bhat R et al, 2024 [87] .RT/CT: Chen HW. 2017 [100] . Phagocytosis - Marc Lecoultre et al, 2024. [102] . ISP -Carl-Henrik Heldin, et al., 2004, [101] - Blendi Ura, et al., 2018 [103] . Lymphatic normalization Goel S et al, 2011 [92] . Antigenicity & Adjuvanticity -Appleton, E., et al 2021. [98] . In situ Vaccination: Feng K, et al, 2025, [104] . Nanoparticle therapy - Naimeng Liu, et al [105] .Vaccine therapy -Matthew D Kerr, et al., 2022, [106] . Epigenetic Therapy integration: -Bangarh R et al. 2024 [107] -Kurrey NK et al. 2009 [108] -Fotana R et al, 2024 [109] |

| Phase III |

Primary therapy Primarily Immune Modulation a. When Cancer Cells and TME are primed and Ready to initiate with immunotherapy. Additionally; b. Timed/Pulsed SBRT/SBRT Boost c. Immune adjuvants d. Phagocytosis checkpoints e. In situ vaccination f. Nanoparticle therapy g. Epigenetic therapy |

2 to 3 weeks after Neoadjuvant CT/RT (SBRT) Or after Surgery |

1. Optimize the immunotherapy schedule by starting immunotherapy when cancer cells are unmasked and CCME modulated for maximum response & least toxicity. 2. Integrated Boost/Pulsed SBRT for dynamic generation of contemporary neoantigen for in-situ vaccination effect and to improve memory cell pool. |

.Immunotherapy Optimization: -Sordo-Bahamonde et al., 2023, [115] -Lussier, DM et al., 2022 [116] . Timed SBRT: -Breen, WG et al., 2020 [117] -He K et al., 2021 [118]. - Mathieu Spaas, et al., 2019 [119] . Oxygenation: -Shibamoto, Y et al., 2016 [99] . In situ vaccination: -Feng K. et al, 2025; 104] -Kewen He. et al, 2021. [118] . Nanoparticle-Immunotherapy: - Naimeng Liu et al., 2025 [105] . Epigenetic therapy: Shweta Josh, et al., 2019. [121] |

| Phase IV |

Post-Primary therapy: Primarily about eliminating MRD/Dormancy/DTPs/ Senescence a. Consolidation Therapy of Immunotherapy Effects, Normalization of ECM and Immune Activated TILs. b. Anti-evolutionary resistance strategy & epigenetic modifiers, e.g., (BET) protein inhibitors c. Normalized soft ECM |

2 to 3 weeks After Primary Therapy. Maintenance Immunotherapy / Targeted therapy as per the guidelines |

1. Design the maintenance therapy with the least long-term side effects. 2. Develop anticancer/repurposed drugs suitable for long-term medications to prevent the recurrence/ eliminate dormant cells, like any other chronic disease. |

. Supple ECM: - Zhao Y, et al, 2020 [30] -Targeting TGFβ, Matrix metallo-proteinases, Integrins, etc.: -Meiling Zhang, et al, 2025 [122] .Targeting DTPs: -Wei Lu et al, 2019 [5] -Williams ED et al, 2019 [54] -BET inhibitors: - Chen M et al, 2024 [89] .Epigenetic Reversion -Pensotti A et al., 2024 [53] . Monitoring: -Nezami et al., 2015 [65] |

| Phase V |

Probative therapy: Primarily to abate inflammation and restore immune editing. Presently Exploratory – Evolutionary Therapy Strategy /EMP Intervention Strategy. Reprogramming of the ECM/Cancer reversion. Prevents late recurrences. Monitoring is done with epigenetic markers. |

Starts from the point when patients are apparently cured/ unacceptable toxicity/ Progression |

1. To keep the ECM supple. Secondly, to target HIF1-α and ROS to flip towards normalization of the ECM and eliminate dormant cells. 2. Reducing inflammation by maintenance therapy, senolytics, and lifestyle modifications or combinations thereof. 3. Evolutionary Infomed Therapy (EIT) or MTET strategy. |

.Reducing ROS/ HIF-1α: -Mengnuo Chen, et al 2024 [89] .Senescence: -Škarková A et al.,2024 [48] . Senolytics: -Susan Short, et al, 2019 [123] . Lifestyle: -Pasquale Marino. et al 2024 [125] -Shujie Liu, et al, 2025 [126] . Evolutionary Therapies: - Gatenby, et al, 2020 [4] - Nezami. et al., 2015. [65] - Škarková A, et al, 2024 [48] . Monitoring: -Nezami. Et al 2015 [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).