Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

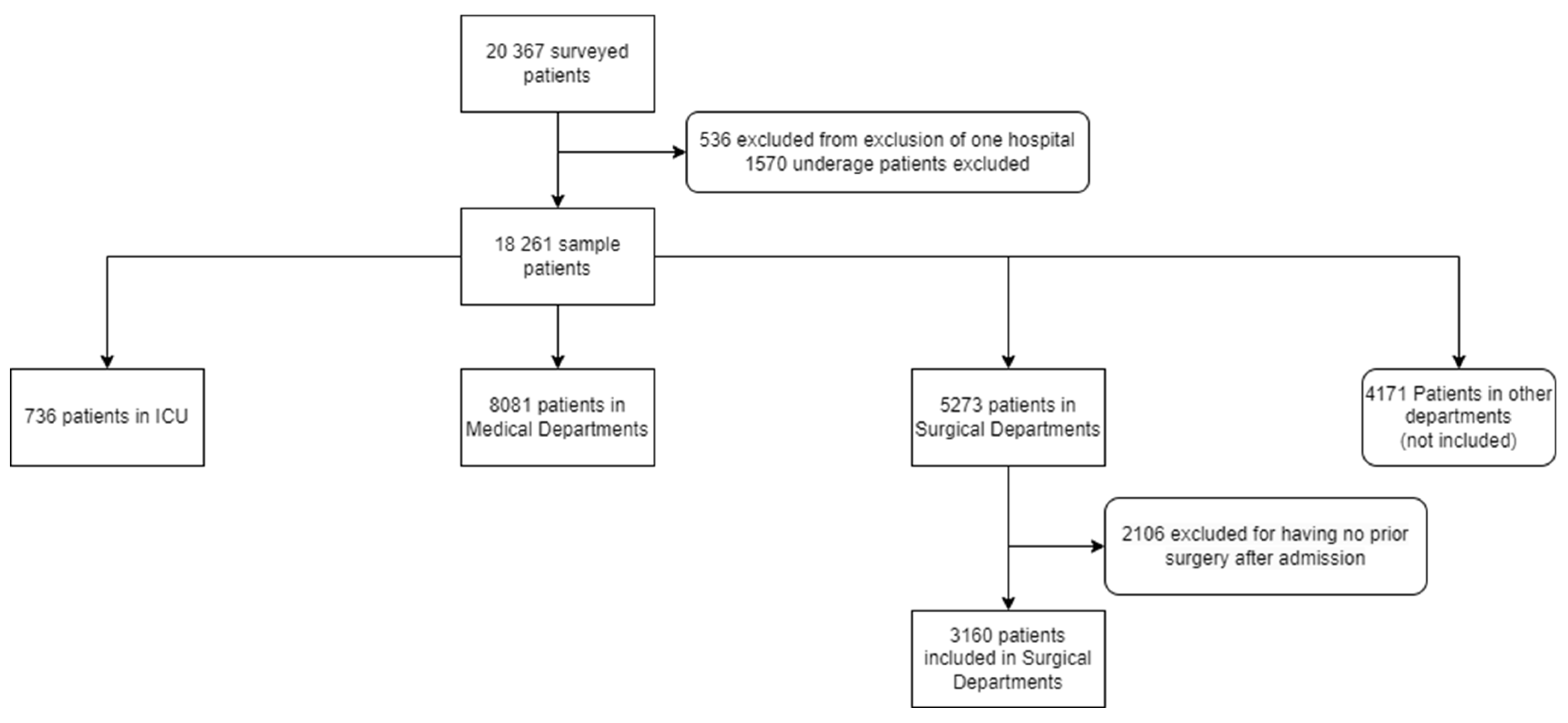

2. Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

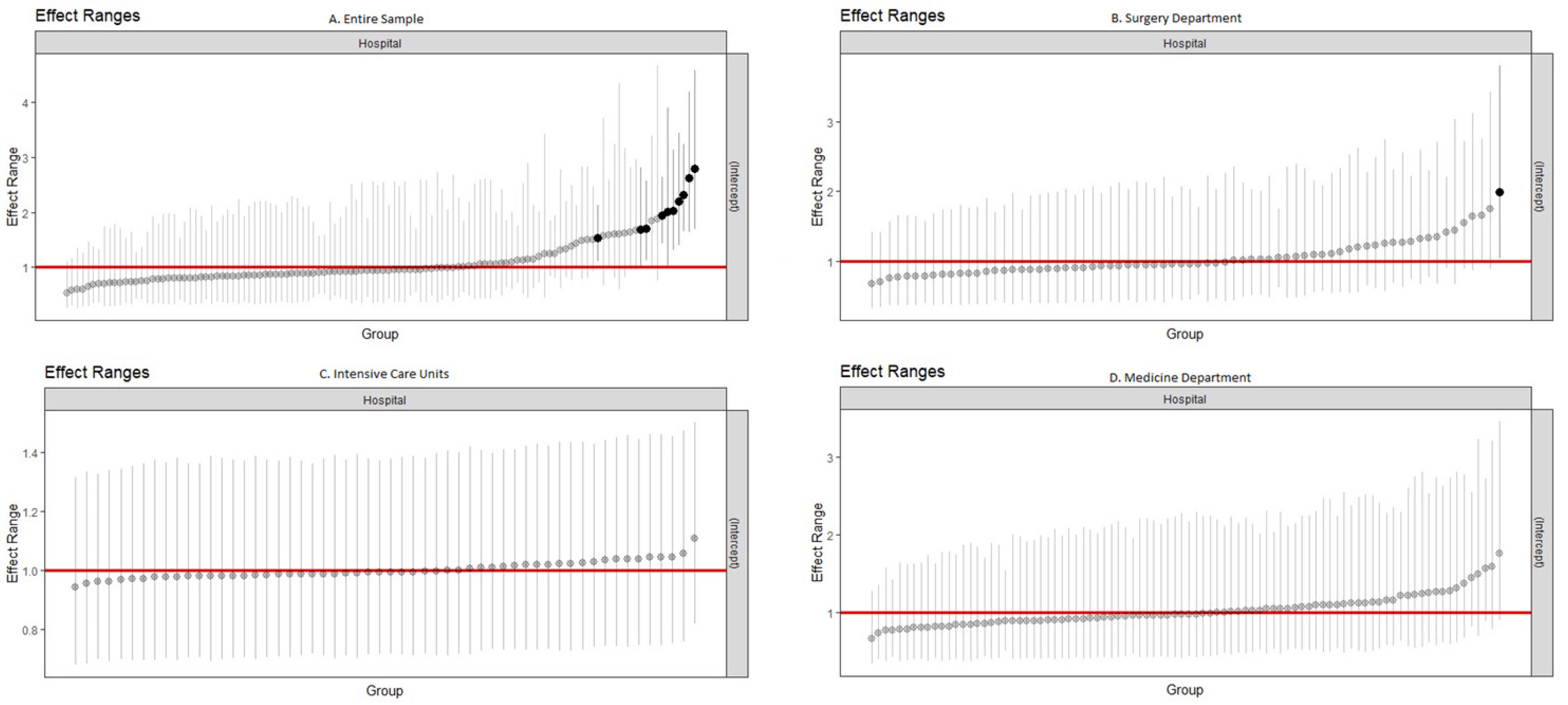

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Ethics Approval

Conflict of Interest

References

- Umscheid, C.A.; Mitchell, M.D.; Doshi, J.A.; Agarwal, R.; Williams, K.; Brennan, P.J. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, A.; Plachouras, D.; Eckmanns, T.; Abu Sin, M.; Blank, H.P.; Ducomble, T. , et al. Burden of Six Healthcare-Associated Infections on European Population Health: Estimating Incidence-Based Disability-Adjusted Life Years through a Population Prevalence-Based Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals; ECDC: Stockholm, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mouajou, V.; Adams, K.; DeLisle, G.; Quach, C. Hand hygiene compliance in the prevention of hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2022, 119, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop-Vicas, A.E.; Abad, C.; Baubie, K.; Osman, F.; Heise, C.; Safdar, N. Colorectal bundles for surgical site infection prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reviejo, R.; Tejada, S.; Jansson, M.; Ruiz-Spinelli, A.; Ramirez-Estrada, S.; Ege, D. , et al. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia through care bundles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Med. 2023, 3, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, U.; Okolie, O.J.; Ismail, S.U.; Adukwu, E. Effectiveness of infection prevention and control interventions in health care facilities in Africa: A systematic review. Am J Infect Control. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Schmid, M.N.; Parneix, P.; Lebowitz, D.; de Kraker, M.; Sauser, J. , et al. Impact of environmental hygiene interventions on healthcare-associated infections and patient colonization: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malheiro, R.; Peleteiro, B.; Correia, S. Beyond the operating room: do hospital characteristics have an impact on surgical site infections after colorectal surgery? A systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.; Shamliyan, T.; Mueller, C.; Duval, S.; Wilt, T. The Association of Registered Nurse Staffing Levels and Patient Outcomes. Medical Care. 2007, 45, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Yun, I.; Jang, S.Y.; Park, E.C.; Jang, S.I. Association between nurse staffing level in intensive care settings and hospital-acquired pneumonia among surgery patients: result from the Korea National Health Insurance cohort. Epidemiol Infect. 2024, 152, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1996. Milbank Q. 2005, 84, 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals – protocol version 6.1; ECDC: Stockholm, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2018; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of surgical site infections and prevention indicators in European hospitals - HAI-Net SSI protocol, version 2.2; ECDC: Stockholm, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zingg, W.; Metsini, A.; Balmelli, C.; Neofytos, D.; Behnke, M.; Gardiol, C. , et al. National point prevalence survey on healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals, Switzerland, 2017. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Monette, G. Generalized Collinearity Diagnostics. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1992, 87, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. Um desafio Gulbenkian 2018.

- Direção-Geral da Saúde, Stop Infeção Hospitalar 2.0. 20 September. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/em-destaque/stop-infecao-hospitalar-20.aspx.

- von Lengerke, T.; Lutze, B.; Graf, K.; Krauth, C.; Lange, K.; Schwadtke, L. ; et al. Psychosocial determinants of self-reported hand hygiene behaviour: a survey comparing physicians and nurses in intensive care units. J Hosp Infect. 2015, 91, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicentini, C.; Bussolino, R.; Gastaldo, C.; Castagnotto, M.; D’Ancona, F.P.; Zotti, C.M. , et al. Level of implementation of multimodal strategies for infection prevention and control interventions and prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in Northern Italy. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2024, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Traverson, L.; Chabrol, F.; Gautier, L.; de Araujo Oliveira, S.R.; David, P.M. , et al. Communication and Information Strategies Implemented by Four Hospitals in Brazil, Canada, and France to Deal with COVID-19 Healthcare-Associated Infections. Health Syst Reform. 2023, 9, 2223812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.G.; Hall, L.; White, N.; Barnett, A.G.; Halton, K.; Paterson, D.L. , et al. An environmental cleaning bundle and health-care-associated infections in hospitals (REACH): a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019, 19, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Park, J.E.; Hwang, S.; Kwon, K.T. Crucial role of temporary airborne infection isolation rooms in an intensive care unit: containing the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. Crit Care. 2020, 24, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Abraham, R.; Keller, N.; Szold, O.; Vardi, A.; Weinberg, M.; Barzilay, Z. , et al. Do isolation rooms reduce the rate of nosocomial infections in the pediatric intensive care unit? J Crit Care. 2002, 17, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, A.; Eisenring, M.C.; Troillet, N.; Kuster, S.P.; Widmer, A.; Zwahlen, M. , et al. Surveillance quality correlates with surgical site infection rates in knee and hip arthroplasty and colorectal surgeries: A call to action to adjust reporting of SSI rates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troillet, N.; Aghayev, E.; Eisenring, M.C.; Widmer, A.F.; Swissnoso, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. First Results of the Swiss National Surgical Site Infection Surveillance Program: Who Seeks Shall Find. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiopanos, K.; Krystallaki, D.; Mellou, K.; Kotoulas, P.; Kavakioti, C.A.; Vorre, S. , et al. Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in acute care hospitals in Greece, 2022, results of the third point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2024, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbadoro, P.; Dolcini, J.; Fortunato, C.; Mengarelli Detto Rinaldini, D.; Martini, E.; Gioia, M.G. , et al. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use and healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals: a comprehensive report from the Marche Region of Italy. J Hosp Infect. 2023, 141, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hospital Variables | All hospitals | ICU Department | Surgical Department | Medicine Department | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals n(%) |

Patients n(%) |

Hospitals n(%) |

Patients n(%) |

Hospitals n(%) |

Patients n(%) |

Hospitals n(%) |

Patients n(%) | |

| No. Hospitals | 119 | - | 56 | - | 72 | - | 90 | - |

| No. Patients | - | 18 261 | - | 736 | 3 160 | - | 8 081 | |

| No. Patients with HAI (Prevalence) | - | |||||||

| SSI | - | 261 (1.4) | - | - | - | 187 (5.9) | - | - |

| CLABSI | - | 38 (0.2) | - | 3 (0.4) | - | - | - | - |

| PAI | - | 72 (0.4) | - | 42 (5.7) | - | - | - | - |

| CAUTI | - | 277 (1.5) | - | 13 (1.8) | - | - | - | 138 (1.7) |

| No. HAI | - | 638 (3.5) | - | 58 (7.9) | - | 187 (5.9) | - | 138 (1.7) |

| No. Patients on antibiotic | - | 7 521 (41.1) | - | 456 (61.3) | 1 544 (48.9) | - | 3 464 (42.9) | |

| Age (median[IQR]) | - | 71 (56–82) | - | 67 (55–76) | - | 68 (56–78) | - | 76 (64–85) |

| Male Sex | - | 9 182 (50.3) | - | 455 (61.2) | - | 1 653 (52.3) | - | 4 184 (51.8) |

| McCabe Score | ||||||||

| Ultimately fatal | - | 4 068 (22.3) | - | 148 (19.9) | - | 524 (16.6) | - | 2 437 (30.1) |

| Rapidly fatal | - | 1 033 (5.7) | - | 72 (9.7) | - | 67 (2.1) | - | 648 (8.0) |

| Nonfatal | - | 12 943 (70.9) | - | 500 (67.2) | - | 2 531 (80.1) | - | 4 931 (61.0) |

| Unknown | - | 204 (1.1) | - | 16 (2.2) | - | 38 (1.2) | - | 65 (0.8) |

| Device Use | ||||||||

| CVC | - | 1 529 (8.4) | - | 461 (62.0) | - | 285 (9.0) | - | 506 (6.3) |

| Urinary catheter | - | 4 250 (23.3) | - | 585 (78.6) | - | 726 (23.0) | - | 1 906 (23.6) |

| Intubation | - | 461 (2.5) | - | 277 (37.2) | - | 50 (1.6) | - | 84 (1.0) |

| Has any device | - | 5 045 (27.6) | - | 608 (81.7) | - | 912 (29.2) | - | 2 309 (28.6) |

| No. Devices (median[IQR]) | - | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | - | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | - | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | - | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) |

| Surgery Since Admission | - | 5 315 (29.1) | - | 370 (49.7) | - | - | - | 518 (6.4) |

| Hospital bed size | ||||||||

| 0-250 | 83 (69.7) | 6 109 (28.0) | 21 (37.5) | 130 (17.5) | 11 (15.3) | 703 (22.2) | 54 (60.0) | 2 273 (28.1) |

| 251-500 | 24 (20.2) | 6 264 (34.3) | 24 (42.9) | 290 (39.0) | 24 (33.3) | 1 116 (35.3) | 24 (26.7) | 2 537 (31.4) |

| >500 | 12 (10.1) | 6 888 (37.7) | 11 (19.6) | 316 (52.5) | 37 (51.4) | 1 341 (42.4) | 12 (13.3) | 3 271 (40.5) |

| Hospital Type | ||||||||

| Primary | 28 (23.5) | 1 366 (7.5) | 5 (8.9) | 34 (4.6) | 7 (9.7) | 127 (4.0) | 18 (20.0) | 727 (9.0) |

| Secondary | 50 (42.0) | 7 248 (39.7) | 25 (44.6) | 233 (31.3) | 36 (50.0) | 930 (29.4) | 44 (48.9) | 3 585 (44.4) |

| Specialized | 11 (9.2) | 840 (4.6) | 2 (3.6) | 19 (2.6) | 4 (5.6) | 208 (6.6) | 3 (3.3) | 195 (2.4) |

| Tertiary | 30 25.2) | 8 807 (48.2) | 24 (42.9) | 450 (60.5) | 25 (34.7) | 1 895 (60.0) | 25 (27.8) | 3 574 (44.2) |

| Hospital Location | ||||||||

| Norte | 31 (26.1) | 6 146 (33.7) | 15 (26.8) | 311 (41.8) | 22 (30.6) | 1 221 (38.6) | 25 (27.8) | 2 319 (828.7) |

| Centro | 28 (23.5) | 3 488 (19.1) | 9 (16.1) | 88 (11.8) | 13 (18.1) | 633 (20.0) | 19 (21.1) | 1 461(18.1) |

| Lisbon | 40 (33.6) | 6 083 (33.3) | 22 (39.3) | 261 (35.1) | 24 (33.3) | 877 (27.8) | 30 (33.3) | 3 056 (37.8) |

| Other | 20 (16.8) | 2 544 (13.9) | 10 (17.9) | 76 (10.2) | 13 (18.1) | 429 (13.6) | 16 (17.8) | 1 245 (15.4) |

| No. Hospital Isolation Rooms | 0 (0–4) | 5 (1–10) | 4 (1–10) | 8 (2–14) | 2 (0–8) | 6 (1–8) | 1 (0–6) | 5 (1–8) |

| Clinical Tests Weekend | ||||||||

| Both days | 69 (58.0) | 10 140 (55.5) | 31 (55.4) | 463 (62.2) | 7 (9.7) | 314 (9.9) | 51 (56.7) | 4 390 (54.3) |

| One day only | 10 (8.4) | 2 329 (12.8) | 6 (10.7) | 48 (6.5) | 40 (55.6) | 1 851 (58.6) | 9 (10.0) | 1 394 (17.2) |

| Screening Tests Weekend | ||||||||

| Both days | 71 (59.7) | 10 567 (57.9) | 32 (57.1) | 470 (63.2) | 9 (12.5) | 492 (15.6) | 53 (58.9) | 4 610 (57.0) |

| One day only | 13 (10.9) | 3 079 (16.9) | 9 (16.1) | 77 (10.3) | 42 (58.3) | 1 927 (61.0) | 12 (13.3) | 1 604 (19.9) |

| IPC Doctors-to-acute-bed ratio (median[IQR]) | 0.1 (0.0-0.2) | - | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) | - | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) | - | 0.1 (0.0-0.2) | - |

| IPC Nurses-to-acute-bed-ratio (median[IQR]) | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | - | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | - | 0.5 (0.4-0.8) | - | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | - |

| AMS Consultants-to-acute-bed-ratio (median[IQR]) | 0.1 (0.0-0.1) | - | 0.1 (0.0-0.1) | - | 0.1 (0.0-0.1) | - | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | - |

| CEO Approved IPC Plan | 95 (80.5) | 14 890 (81.5) | 47 (83.9) | 630 (84.7) | 57 (79.0) | 2 572 (81.4) | 72 (80.0) | 6 560 (81.2) |

| CEO Approved IPC Report | 97 (82.2) | 15 669 (85.8) | 49 (87.5) | 670 (90.1) | 60 (83) | 2 781 (88.0) | 74 (82.2) | 6 855 (84.8) |

| Universal Masking | ||||||||

| Care | 53 (44.5) | 7 833 (42.9) | 25 (44.6) | 31 (43.1) | 1 471 (46.6) | 35 (38.9) | 3 169 (39.2) | |

| Always | 5 (4.2) | 412 (2.3) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (4.2) | 81 (2.6) | 4 (4.4) | 126 (1.6) | |

| Participation in Surveillance Networks | ||||||||

| Surgical site infection | 45 (37.8) | 8 597 (47.1) | - | - | 33 (45.8) | 1 604 (50.8) | - | - |

| HAI in intensive care units | 35 (29.4) | 9 171 (50.2) | 26 (46.4) | 418 (56.2) | - | - | - | - |

| Clostridium difficile | 19 (16.0) | 3 715 (20.3) | 8 (14.3) | 123 (16.5) | 12 (16.7) | 495 (15.7) | 16 (17.8) | 1 804 (22.3) |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | 56 (47.1) | 10 900 (59.7) | 28 (50.0) | 453 (60.9) | 37 (51.4) | 1 991 (63.0) | 47 (52.2) | 4 839 (59.9) |

| Antimicrobial Consumption | 53 (44.5) | 11 070 (60.6) | 25 (44.6) | 478 (64.2) | 34 (47.2) | 2 070 (65.5) | 45 (50.0) | 4 987 (61.7) |

| Multimodal Strategy Use | ||||||||

| System Change | ||||||||

| Element not included | 4 (3.4) | 104 (0.6) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.3) | 41 (0.5) |

| L1 | 20 (16.8) | 3 891 (21.3) | 10 (17.9) | 143 (19.4) | 12 (16.7) | 584 (18.5) | 18 (20.0) | 1 906 (23.6) |

| L2 | 63 (53.8) | 9 786 (53.6) | 29 (51.8) | 445 (60.5) | 40 (55.6) | 1 931 (61.1) | 47 (52.2) | 4 010 (49.6) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Education and training | ||||||||

| Element not included | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| L1 | 19 (16.0) | 2 185 (12.0) | 9 (16.1) | 57 (7.7) | 9 (12.5) | 310 (9.8) | 41 (15.6) | 867 (10.7) |

| L2 | 69 (57.9) | 11 596 (63.5) | 31 (55.4) | 535 (72.7) | 43 (59.7) | 2 205 (69.8) | 54 (60.0) | 5 090 (63.0) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Monitoring and feedback | ||||||||

| Element not included | 3 (2.5) | 40 (0.2) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (0.02) |

| L1 | 21 (17.6) | 3 194 (17.5) | 8 (14.3) | 175 (23.8) | 10 (13.9) | 557 (17.6) | 18 (20.0) | 1 426 (17.6) |

| L2 | 64 (53.8) | 10 547 (57.8) | 31 (55.4) | 412 (55.9) | 42 (58.3) | 1 958 (61.9) | 49 (54.4) | 4 529 (56.0) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Communications and reminders | ||||||||

| Element not included | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| L1 | 53 (44.5) | 8 267 (45.3) | 25 (44.6) | 365 (49.6) | 31 (43.1) | 1 554 (49.2) | 41 (15.6) | 3 504 (43.4) |

| L2 | 35 (29.4) | 5 514 (30.2) | 15 (26.8) | 227 (30.8) | 21 (29.2) | 961 (30.4) | 27 (30.0) | 2 453 (30.4) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Safety climate and culture change | ||||||||

| Element not included | 16 (13.4) | 2 702 (14.8) | 7 (12.5) | 80 (10.9) | 7 (9.7) | 413 (13.1) | 14 (15.6) | 1 336 (16.5) |

| L1 | 37 (31.1) | 5 322 (29.1) | 18 (32.1) | 222 (30.2) | 22 (30.6) | 899 (28.4) | 27 (30.0) | 2 442 (30.2) |

| L2 | 34 (28.6) | 5 685 (31.1) | 15 (26.8) | 290 (39.4) | 23 (31.9) | 1 203 (38.1) | 26 (28.9) | 2 125 (26.3) |

| Unknown | 32 (26.9) | 4 552 (24.9) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 23 (25.6) | 2 178 (26.6) |

| Is a multidisciplinary team used to implement IPC multimodal strategies | ||||||||

| Yes | 85 (71.4) | 12 620 (69.1) | 37 (66.1) | 535 (72.7) | 49 (68.1) | 2 265 (71.8) | 65 (72.2) | 5 350 (66.2) |

| No | 3 (2.5) | 1 161 (6.4) | 3 (5.4) | 57 (7.7) | 3 (4.2) | 250 (7.9) | 3 (3.3) | 607 (7.5) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Link to develop multimodal with colleagues | ||||||||

| Yes | 79 (66.4) | 11 210 (61.4) | 32 (57.1) | 496 (67.4) | 44 (61.1) | 1 981 (62.7) | 59 (65.6) | 4 723 (58.4) |

| No | 9 (7.6) | 2 571 (14.1) | 8 (14.3) | 96 (13.0) | 8 (11.1) | 534 (16.9) | 9 (10.0) | 1 234 (15.3) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| Bundles or checklists | ||||||||

| Yes | 83 (69.7) | 11 596 (63.5) | 38 (67.9) | 587 (79.8) | 50 (69.4) | 2 477 (78.4) | 64 (71.1) | 5 762 (71.3) |

| No | 5 (4.2) | 2 185 (12.0) | 2 (3.6) | 5 (0.68) | 2 (2.8) | 38 (1.2) | 4 (4.4) | 195 (2.4) |

| Unknown | 31 (26.1) | 4 480 (24.5) | 16 (28.6) | 144 (19.6) | 20 (27.8) | 645 (20.4) | 22 (24.4) | 2 124 (26.3) |

| All Hospitals | ICU | Surgery | Medicine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable | Univariate | Multivariable | Univariate | Multivariable | Univariate | Multivariable | |||||||||

| Patient variable | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value |

| Age | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | -0.01 | 0.573 | - | - | 0.00 | 0.393 | -6.32 | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Male Sex | 0.20 | 0.013 | 0.12 | 0.204 | 0.45 | 0.146 | 0.39 | 0.225 | 0.45 | 0.004 | 0.31 | 0.07900 | -0.19 | 0.274 | - | - |

| McCabe Score | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-Fatal | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| Rapidly Fatal | 0.25 | 0.138 | -0.24 | 0.227 | -0.04 | 0.940 | - | - | 0.94 | 0.0180 | 0.64 | 0.1600 | -0.12 | 0.73 | -0.30 | 0.445 |

| Ultimately Fatal | 0.45 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.163 | 0.30 | 0.381 | - | - | 0.91 | <0.001 | 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.09 | -0.12 | 0.618 |

| Device no. | 0.92 | <0.001 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 1.06 | <0.001 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.025 | 0.06 | 0.6970 | 1.14 | <0.001 | 1.49 | <0.001 |

| Hospital Variable | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value |

| Hospital Bed Size | ||||||||||||||||

| 0-250 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| 250-500 | 0.52 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.936 | -0.46 | 0.259 | - | - | 0.38 | 0.150 | -0.44 | 0.301 | 0.09 | 0.711 | - | - |

| >500 | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 0.257 | 0.09 | 0.810 | - | - | 0.68 | 0.013 | -0.73 | 0.342 | -0.09 | 0.704 | - | - |

| Hospital Type | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary | ref | Ref | Ref | ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||||

| Secondary | 0.20 | 0.416 | -0.12 | 0.666 | 0.29 | 0.706 | - | - | -0.25 | 0.571 | -0.19 | 0.823 | -0.09 | 0.794 | - | - |

| Specialized | 0.49 | 0.156 | -0.89 | 0.076 | -0.11 | 0.928 | - | - | 0.84 | 0.080 | 2.17 | 0.029 | 0.31 | 0.599 | - | - |

| Tertiary | 0.32 | 0.202 | -0.02 | 0.949 | 0.28 | 0.708 | - | - | 0.11 | 0.795 | 0.84 | 0.309 | -0.23 | 0.494 | - | - |

| Hospital Location | ||||||||||||||||

| Lisbon | Ref | - | - | Ref | ref | Ref | Ref | ref | ||||||||

| Centro | 0.02 | 0.918 | - | - | 0.82 | 0.060 | 0.03 | 0.963 | -0.13 | 0.667 | - | - | 0.09 | 0.765 | 0.29 | 0.534 |

| Norte | 0.13 | 0.481 | - | - | 0.39 | 0.263 | -0.42 | 0.517 | 0.07 | 0.763 | - | - | -0.08 | 0.766 | -0.65 | 0.156 |

| Other | 0.044 | 0.846 | - | - | 0.730 | 0.115 | -0.40 | 0.526 | -0.09 | 0.779 | - | - | 0.38 | 0.196 | 0.06 | 0.913 |

| No. Hospital Isolation Rooms | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st quartile | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| 2nd quartile | 0.48 | 0.006 | 0.07 | 0.745 | 0.31 | 0.433 | -0.23 | 0.684 | 0.64 | 0.014 | -0.65 | 0.188 | 0.19 | 0.49 | - | - |

| 3rd quartile | 0.43 | 0.044 | -0.30 | 0.244 | 0.50 | 0.193 | 0.04 | 0.936 | 0.65 | 0.029 | -0.36 | 0.531 | -0.27 | 0.393 | - | - |

| 4th quartile | 0.37 | 0.060 | -0.62 | 0.011 | -0.31 | 0.502 | -0.06 | 0.913 | 0.39 | 0.152 | -0.8 | 0.131 | -0.14 | 0.637 | - | - |

| Clinical Tests on Weekends | ||||||||||||||||

| One day only | -0.31 | 0.247 | 0.09 | 0.852 | -0.68 | 0.380 | - | - | -0.45 | 0.246 | - | - | -0.25 | 0.455 | 0.27 | 0.808 |

| Both days | -0.33 | 0.055 | 0.93 | 0.762 | 0.07 | 0.843 | - | - | -0.23 | 0.316 | - | - | -0.32 | 0.172 | 0.87 | 0.530 |

| Screening Tests on Weekends | ||||||||||||||||

| One day only | -0.13 | 0.603 | -0.78 | 0.026 | -0.44 | 0.475 | - | - | -0.29 | 0.410 | - | - | -0.55 | 0.104 | -0.56 | 0.468 |

| Both days | -0.30 | 0.104 | -0.93 | 0.220 | 0.09 | 0.800 | - | - | -0.21 | 0.420 | - | - | 0.42 | 0.089 | -1.55 | 0.243 |

| IPC Doctors-to-acute-bed ratio | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st quartile | Ref | Ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| 2nd quartile | -0.24 | 0.188 | 0.27 | 0.185 | -0.93 | 0.033 | -0.24 | 0.672 | 0.11 | 0.686 | 1.31 | 0.006 | -0.57 | 0.0531 | 0.12 | 0.797 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.08 | 0.673 | -0.03 | 0.909 | -0.59 | 0.132 | -0.03 | 0.958 | 0.41 | 0.147 | 0.99 | 0.048 | -0.14 | 0.6146 | 1.06 | 0.063 |

| 4th quartile | 0.29 | 0.145 | 0.50 | 0.031 | -0.06 | 0.862 | 0.75 | 0.293 | 0.33 | 0.256 | 0.80 | 0.089 | -0.14 | 0.6206 | 0.99 | 0.121 |

| IPC Nurses-to-acute-bed ratio | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st quartile | Ref | Ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| 2nd quartile | 0.27 | 0.118 | 0.62 | 0.028 | 0.27 | 0.531 | 0.33 | 0.557 | 0.48 | 0.071 | 2.44 | <0.001 | -0.13 | 0.666 | 0.09 | 0.848 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.70 | 0.007 | 0.53 | 0.189 | 0.68 | 0.255 | 0.52 | 0.052 | 2.20 | 0.004 | 0.42 | 0.104 | 0.55 | 0.167 |

| 4th quartile | 0.42 | 0.044 | 0.25 | 0.936 | 0.15 | 0.743 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.66 | 0.025 | 2.09 | 0.005 | -0.32 | 0.298 | -0.95 | 0.037 |

| AMS Consultants-to-acute-bed-ratio | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st quartile | Ref | - | - | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| 2nd quartile | -0.04 | 0.841 | - | - | -0.29 | 0.456 | - | - | -0.22 | 0.424 | - | - | 0.02 | 0.941 | 0.28 | 0.451 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.11 | 0.616 | - | - | -0.47 | 0.247 | - | - | 0.31 | 0.234 | - | - | -0.46 | 0.129 | -0.17 | 0.736 |

| 4th quartile | 0.23 | 0.269 | - | - | -0.13 | 0.724 | - | - | 0.28 | 0.302 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.978 | -0.30 | 0.572 |

| CEO Approved IPC Plan | 0.01 | 0.967 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.979 | - | - | 0.26 | 0.324 | - | - | -0.50 | 0.0294 | -0.70 | 0.206 |

| CEO Approved IPC Report | 0.18 | 0.39 | - | - | 0.59 | 0.337 | - | - | 0.22 | 0.472 | - | - | -0.242 | 0.382 | - | - |

| Participation in Surveillance Network | ||||||||||||||||

| SSI | 0.15 | 0.418 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 | 0.636 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ICU | 0.15 | 0.377 | - | - | 0.32 | 0.332 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CDI | 0.09 | 0.642 | - | - | -0.45 | 0.318 | - | - | 0.30 | 0.221 | - | - | 0.29 | 0.287 | - | - |

| AMR | 0.34 | 0.055 | 0.21 | 0.538 | -0.35 | 0.314 | - | - | 0.87 | 0.003 | 0.84 | 0.237 | 0.48 | 0.102 | -0.04 | 0.957 |

| AMC | 0.34 | 0.039 | 0.49 | 0.242 | -0.46 | 0.185 | -0.89 | 0.126 | 0.62 | 0.011 | 0.29 | 0.701 | 0.59 | 0.0354 | 1.10 | 0.15 |

| Universal Masking | ||||||||||||||||

| Care | 0.39 | 0.010 | 0.44 | 0.007 | 0.25 | 0.430 | - | - | 0.32 | 0.173 | 0.19 | 0.627 | 0.67 | 0.726 | - | - |

| Always | 0.73 | 0.039 | 1.34 | 0.012 | 0.38 | 0.728 | - | - | 0.80 | 0.119 | 1.03 | 0.401 | 0.78 | 0.248 | - | - |

| Multimodal Strategies | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value |

| System Change | ||||||||||||||||

| L2 vs L1 | 0.02 | 0.941 | - | - | 0.09 | 0.813 | - | - | 0.19 | 0.537 | - | - | -0.31 | 0.201 | - | - |

| Education & Training | ||||||||||||||||

| L2 vs L1 | -0.15 | 0.508 | - | - | 0.50 | 0.412 | - | - | -0.10 | 0.769 | - | - | -0.48 | 0.089 | 0.08 | 0.885 |

| Monitoring & Feedback | ||||||||||||||||

| L2 vs L1 | -0.06 | 0.795 | - | - | -0.18 | 0.578 | - | - | -0.31 | 0.295 | - | - | -0.30 | 0.255 | - | - |

| Communication | ||||||||||||||||

| L2 vs L1 | -0.37 | 0.048 | -0.46 | 0.006 | -0.34 | 0.293 | - | - | -0.03 | 0.912 | - | - | -0.24 | 0.33 | - | - |

| Safety Culture Change | ||||||||||||||||

| L1 | -0.35 | 0.154 | 0.52 | 0.065 | -0.43 | 0.375 | - | - | -0.31 | 0.385 | -0.87 | 0.175 | -0.61 | 0.0211 | -0.06 | 0.922 |

| L2 | -0.28 | 0.255 | 0.59 | 0.091 | 0.11 | 0.807 | - | - | -0.60 | 0.096 | -1.59 | 0.019 | -0.64 | 0.0223 | -0.01 | 0.987 |

| Multidisciplinary Team | -0.38 | 0.337 | - | - | -0.10 | 0.847 | - | - | -0.32 | 0.492 | - | - | -0.61 | 0.0879 | -0.43 | 0.561 |

| Link to develop strategies with colleagues | -0.52 | 0.025 | -0.42 | 0.151 | 0.17 | 0.749 | - | - | -0.57 | 0.052 | 0.89 | 0.168 | -0.24 | 0.397 | - | - |

| Bundles or Checklists | 0.33 | 0.530 | - | - | 0.24 | 0.526 | - | - | 0.81 | 0.464 | - | - | 0.24 | 0.731 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).