3.2. Interpretation of Response Surface Methodology

3.2.1. Interpretation of Statistical Analysis

The effects of three independent processing variables such as particle size, heat treatment time, and extraction time on oil yield were investigated using response surface methodology (RSM). The study employed a face-centered central composite design (FCCD) to explore both the main effects and the interaction effects of these variables on the oil yield. This approach enabled a comprehensive analysis of how each factor individually and in combination influences the efficiency of oil extraction.

The highest actual oil yield (28.33%) was achieved with a particle size of 250 µm, a heat treatment time of 30 Min, and an extraction time of 7Hr. Conversely, the lowest yield (12.38%) was obtained with a particle size of 600 µm, a heat treatment time of 50 Min, and an extraction time of 3Hr.

Table 2 illustrates the result of analysis of variance.

The model's F-value of 461.80 indicates that the model is highly significant. P-values less than 0.0500 signify that the corresponding model terms are significant. In this case, the terms A (particle size), C (extraction time), AC (interaction between particle size and extraction time), and A² (the square of particle size) are significant. P-values greater than 0.1000 suggest that the model terms are not significant. If there are numerous insignificant terms (excluding those necessary to maintain model hierarchy), reducing the model could potentially improve its accuracy.

The Lack of Fit F-value of 3.41 suggests that the Lack of Fit is not significant relative to the pure error, with a 10.24% chance that a Lack of Fit F-value this large could be due to random noise. Therefore, particle size, extraction time, the interaction between particle size and extraction time, and the quadratic term of particle size significantly influence the yield of Garden cress seed oil.

Development of Regression Model Equation

The regression model equation that relates the oil yield (response) to the process variables in terms of actual values has been developed. The quality of the model can be assessed by examining the coefficients of correlation. A quadratic polynomial model was determined to be the most appropriate for describing the extraction of Garden cress seed oil using hexane as the solvent. This conclusion is supported by the adjusted R² value of the quadratic model, which is 0.9954 significantly higher than that of the linear (0.7801) and two-factor interaction (0.7322) models.The cubic model was found to be aliased and therefore unsuitable.

As a result, a second-order polynomial (quadratic) model was employed to express the oil yield as a function of the independent process variables. The equation for the model in terms of coded values is as follows:

Yield=25.19-6.85A-0.244B+0.848C- 0.146AB+0.351AC+0.0537BC-4.983A2+0.361B2+0.311C²

Where: A=Particle size

B=Heating time

C=Extraction time

Model Adequacy Check

The adequacy of the model was evaluated by examining the coefficient of determination (R²) and the adjusted coefficient of determination (R²_adj). The values obtained were 0.9976 and 0.9954, respectively, indicating an excellent fit of the estimated model with the experimental data. An R² value of 0.9976 implies that 99.76% of the total variation in the oil yield can be attributed to the experimental variables studied. According to Draper and Smith, (1998), for a model to be considered a good fit, the R² value should be at least 0.8. Since the obtained R² value (0.9976) is significantly higher than 0.8, it suggests that the regression model accurately explains the actual response.

Additionally, the predicted R² value of 0.9807 is in close agreement with the adjusted R² (0.9954), with a difference of less than 0.1, indicating that the model can be reliably used for interpolation. The figure below presents the normal plot and the graph of actual versus predicted oil yield, both of which display a linear relationship, further confirming the model's adequacy.

The Effect of Individual Factors on Oil Yield

The influence of individual independent process variables on the yield of Garden cress seed oil was investigated, focusing on particle size, heating time, and extraction time. The results are presented in the following sections.

Effect of Particle Size on Oil Yield

The highest oil yield (27.37%) was obtained with a particle size of 250 µm, while the lowest yield (12.85%) occurred with a particle size of 600 µm. The higher yield at smaller particle sizes is due to the larger surface area available for contact with the solvent, allowing oil to diffuse out more efficiently. In contrast, larger particle sizes have a reduced surface area, creating resistance to solvent penetration and making it more difficult for the oil to diffuse out.

However, it is important to note that if the particle size becomes too small, it can lead to agglomeration and the formation of a paste-like structure, which can reduce the solvent’s ability to effectively contact the particles' surface. This phenomenon aligns with findings from Nagy and Simándi, (2008),who studied the effect of particle size on the extraction efficiency of oil using the supercritical fluid extraction method and found that extraction efficiency was highest with particle sizes ranging between 100 and 700 µm.

Effect of heat treatment time on oil yield

A higher oil yield (26.01%) was achieved with a heat treatment time of 30 Min, while a lower yield (24.9%) was observed at a heat treatment time of 50 Min.

This finding is consistent with previous studies. For instance, (Uquiche et al., 2008), investigated the effect of microwave pretreatment on the mechanical extraction of oil from Chilean hazelnuts. They found that treating the nuts under 400W for 240 seconds resulted in a 45.3% oil yield, which was significantly higher than the yield from untreated samples (6.1%). Similarly, Moreau et al., (1999), studied the effect of heat pretreatment using a convection oven and reported a slight increase in oil yield, further supporting the notion that optimal heat treatment can enhance oil extraction efficiency.

Effect of extraction time on oil yield

The highest yield (26%) was achieved with an extraction time of 7Hr., while the lowest yield (24.81%) was observed with an extraction time of 3Hr. This suggests that extending the extraction time allows for more thorough extraction of the oil, likely due to increased contact time between the solvent and the seed particles, leading to a higher oil yield but Ntalikwa, (2021) reported that there was not significant increase on the oil yield after 7Hr. of extraction time.

Effect of the interaction of process variables on oil yield

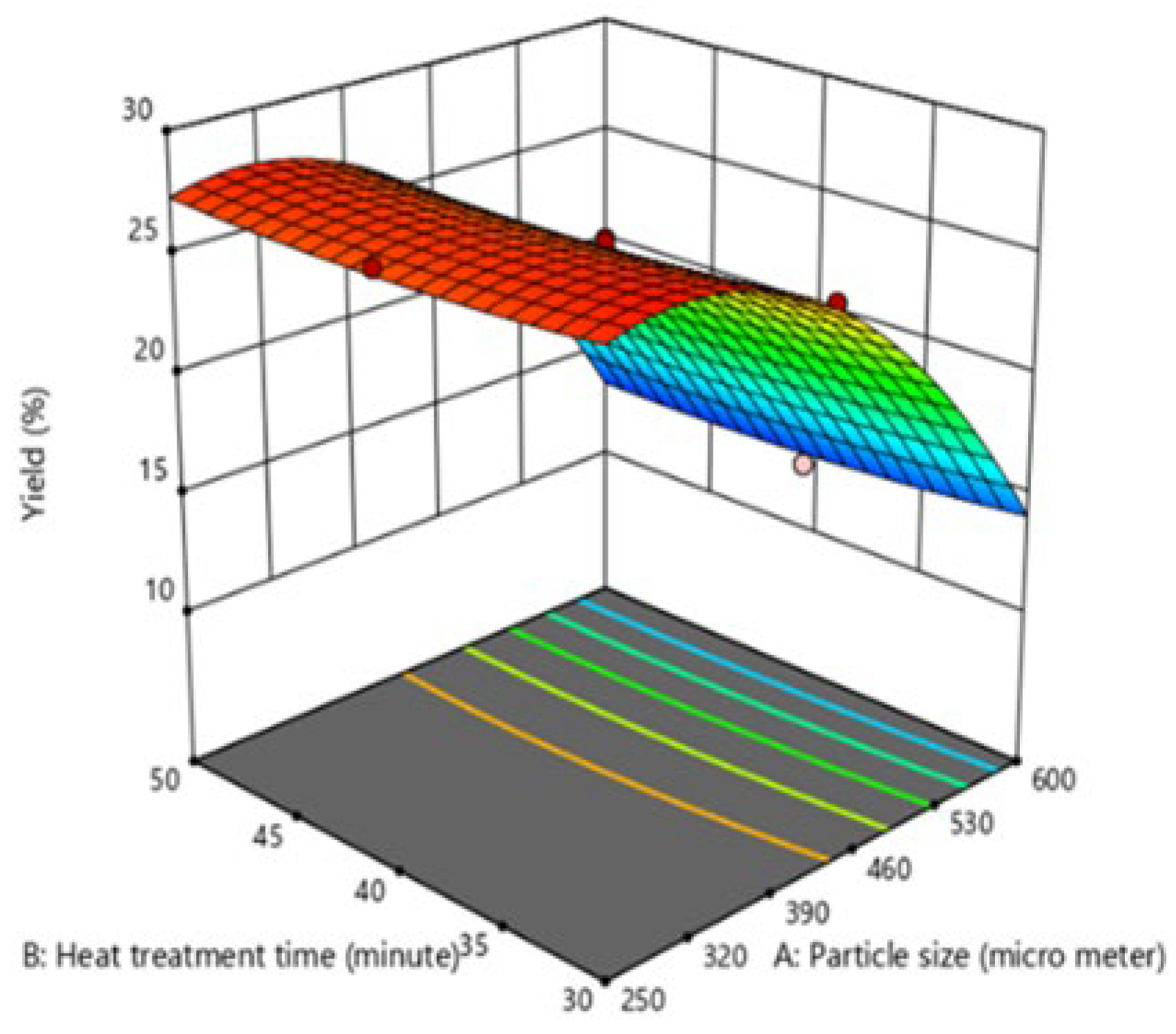

Based on the analysis of variance (ANOVA), the interaction between particle size (A) and heat treatment time (B) (

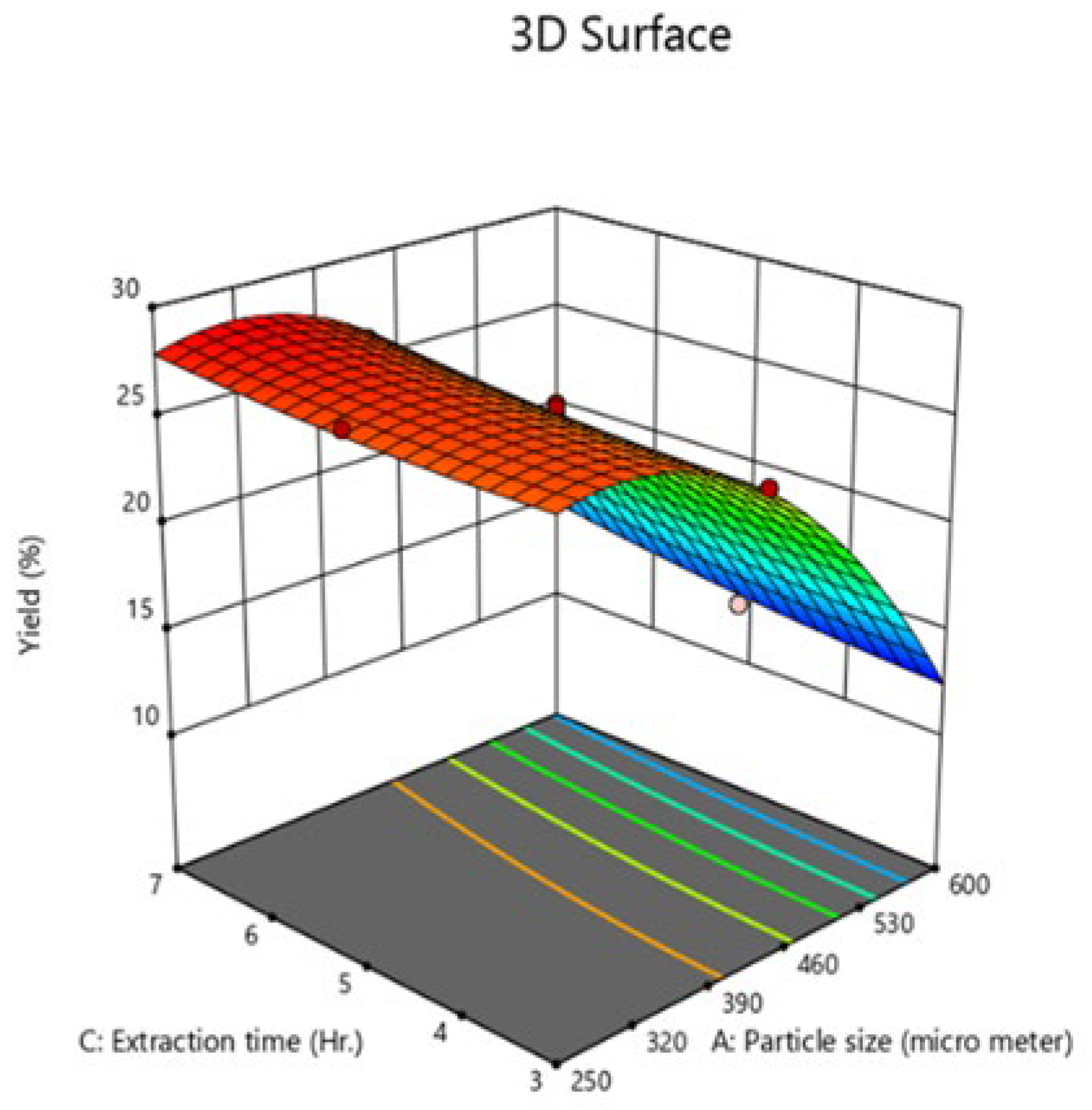

Figure 1) was found to be insignificant, with a p-value of 0.2957. Conversely, the interaction between particle size (A) and extraction time (C) (

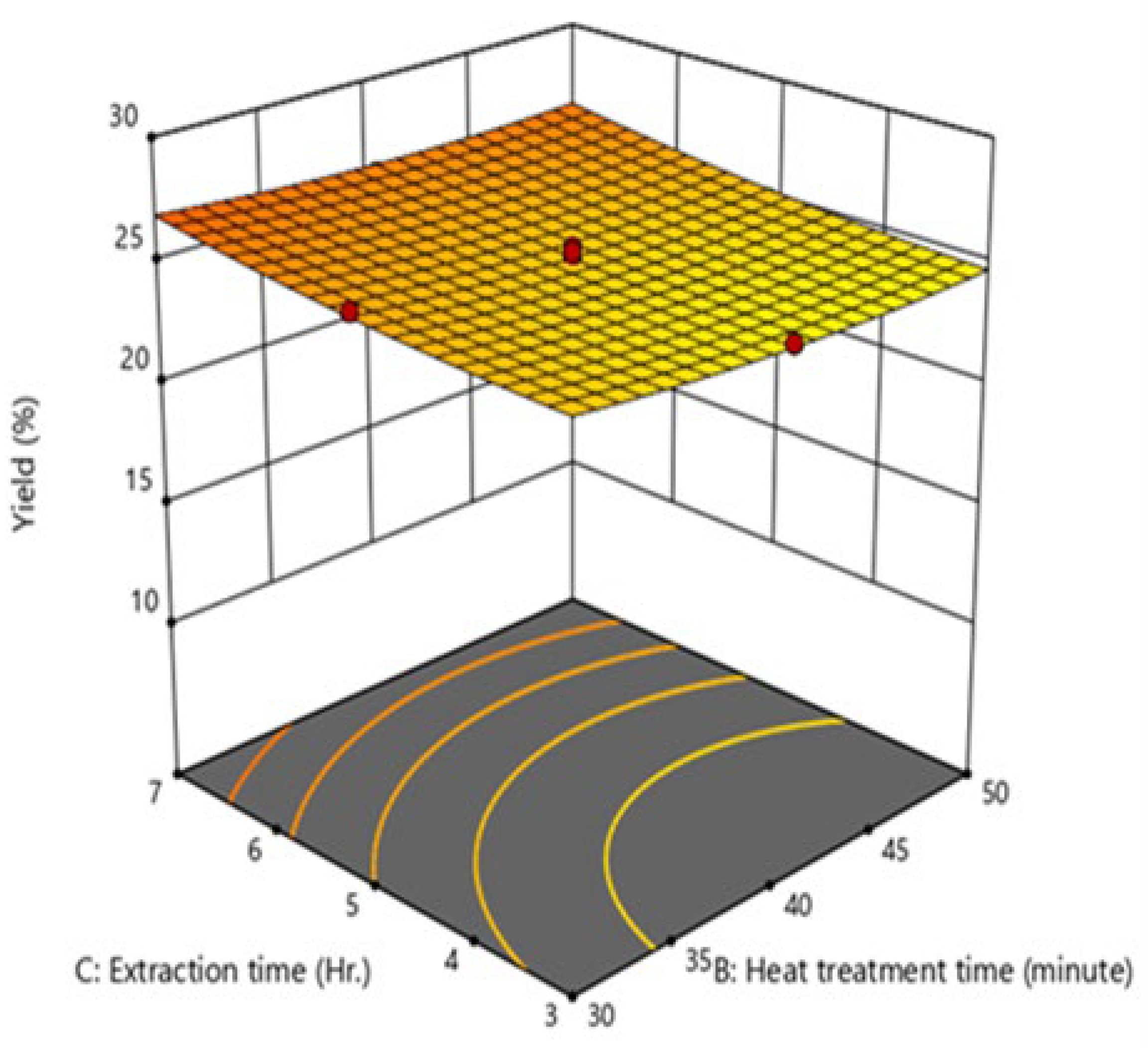

Figure 2) was significant, with a p-value of 0.0243, indicating that this combination of variables significantly influences oil yield. Lastly, the interaction between heat treatment time (B) and extraction time (C) ) was also found to be insignificant, with a p-value of 0.6936.

Optimal Process Variables for the Extraction of Garden Cress Seed Oil

After ensuring an accurate estimate of the true response through statistical analysis and diagnostic graphs, the optimization of process variables to achieve the highest oil yield was conducted. The predicted optimal combination of process variables included a particle size of 319.22 µm, a heat treatment time of 48.87 Min, and an extraction time of 6.99Hr., which resulted in a predicted oil yield of 28.65% with a desirability of 1.

To validate the model, Garden cress seed oil was extracted using hexane under the predicted optimal conditions three times, resulting in an average oil yield of 28.53%. The difference between the predicted and actual yields was minimal, at just 0.12%, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the model.

3.2.2. Physical Properties of Garden Cress Seed Oil

Density of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The density of Garden cress seed oil was measured to be 700kg/m³. In comparison, Sachin et al., (2020), reported densities of 900 kg/m³ for oil extracted using hexane solvent and 1010 kg/m³ for oil extracted with petroleum ether solvent. Musara et al., (2020) reported densities of 900 kg/m³ and 910 kg/m³ for oil extracted by solvent extraction and cold press methods, respectively. These values are higher than the density of Garden cress seed oil obtained in this study. The differences in density values reported by different researchers and the value obtained in this study may be attributed to factors such as the extraction method, seed variety, soil type, and climatic conditions in which the seeds were grown. However, the obtained density of 700 kg/m³ falls within the typical range of densities for most edible oils, which generally range from 700 kg/m³ to 950 kg/m³.

Kinematic Viscosity of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The kinematic viscosity of Garden cress seed oil was found to be 67.85mm²/s. Diwakar et al., (2010) reported a viscosity of 64.3 mm²/s, which is lower than the value obtained in this study. Sachin et al., (2020) also reported viscosities of 52.9 mm²/s and 50.1 mm²/s for oil extracted using hexane and petroleum ether, respectively. These values are also lower than the value found in this study. The variation in viscosity values may be due to differences in the methods used for determining viscosity, the extraction methods, seed species, climatic conditions, and the harvest time of the seeds.

Refractive Index of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The refractive index of Garden cress seed oil at 20℃ was found to be 1.473. Musara et al., (2020) reported a similar refractive index of 1.47, which aligns closely with the results of this study. Sachin et al., (2020) found refractive indices of 1.25 and 1.3 for oil extracted using hexane and petroleum ether solvents, respectively. Another study by Diwakar et al., (2010) and by Rezig et al., (2022a) also reported a refractive index of 1.47, consistent with the results of this study.

The physical properties of Garden cress seed oil, such as refractive index, viscosity, and density, are crucial in determining various properties of food products developed from this oil (Musara et al., 2020). For instance, the refractive index serves as an indicator of unsaturation and the presence of unusual components, such as hydroxyl groups, in Garden cress seed oil (Sachin et al., 2020). Therefore, the higher refractive index of 1.47 falls within the range of typical of edible oils and indicates potential use for food fortification (Musara et al., 2020).

3.2.3. Chemical Properties of Garden Cress Seed Oil

Free Fatty Acid Value of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The free fatty acid (FFA) value of Garden cress seed oil (GCSO), expressed as a percentage of oleic acid, was found to be 0.64%. Various studies have reported differing FFA values for GCSO. For example, Musara et al., (2020) reported FFA values of 0.28%, 0.39%, and 1.52% for GCSO extracted using cold press, Soxhlet, and supercritical CO₂ extraction methods, respectively. Sachin et al., (2020) found FFA values of 0.41% and 0.37% for GCSO extracted using hexane and petroleum ether, respectively. The FFA value obtained in this study is close to those reported in the literature, although slight differences exist, likely due to variations in the determination methods, seed species, extraction temperature, and solvents used.

Peroxide Value of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The peroxide value of GCSO was determined to be 3.59 meq.kg⁻¹. Musara et al., (2020) reported peroxide values of 2.63 meq.kg⁻¹ for oil extracted using supercritical CO₂ extraction and 1.27 meq.kg⁻¹ for oil extracted using solvent extraction. Additionally, they reported a peroxide value range of 2.53–4.09 meq.kg⁻¹ for oil extracted using the Soxhlet method. Sachin et al., (2020) reported peroxide values of 4.03 and 3.9 meq.kg⁻¹ for oil extracted using hexane and petroleum ether, respectively, while Diwakar et al., (2010) found a peroxide value of 4.09 meq.kg⁻¹ for oil extracted using the Soxhlet method and 2.4 meq.kg⁻¹ was reported by Rezig et al., (2022a). Although there are slight differences in the peroxide values reported in this study and by other authors, the values are all within the range expected for fresh oils, which should have peroxide values below 10 meq.kg⁻¹.

Iodine Value of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The iodine value obtained in this study was 127g I₂ absorbed/100 g. This value is consistent with those reported by other researchers. For example, Sachin et al., (2020) reported iodine values of 125 and 122 g I₂ absorbed/100 g for GCSO extracted using hexane and petroleum ether, respectively. Diwakar et al., (2010) reported iodine values of 122, 131, and 123 g I₂ absorbed/100g for GCSO extracted using cold press, Soxhlet, and supercritical CO₂ extraction methods, respectively. Rezig et al., (2022a) reported iodine value of 165 (gI2/100g).

Saponification Value of Garden Cress Seed Oil

The saponification value of GCSO was found to be 183.84mg KOH/g. Diwakar et al., (2010) reported saponification values of 178.85 mg KOH/g for GCSO extracted using the cold press method, and 182.23 mg KOH/g and 174 mg KOH/g for oil extracted using Soxhlet and supercritical CO₂ extraction methods, respectively. Sachin et al., (2020) reported saponification values of 182.5 mg KOH/g and 170.2 mg KOH/g for oil extracted using hexane and petroleum ether, respectively. Rezig et al., (2022a) reported a saponification value of 179 (mg KOH/g oil).The physicochemical properties of GCSO are summarized in

Table 3.

3.2.4. FTIR Analysis of GCSO

The significance of IR spectroscopy in identifying molecular structures lies in its rich information content and its ability to assign specific absorption bands to functional groups. In the spectra of fats and oils, most bands and shoulders can be attributed to distinct functional groups (Rezig et al., 2022). The IR spectral analysis of Garden Cress Seed Oil (GCSO) confirms the presence of several functional groups in the sample:

Saturated Ester (C=O Stretch): A peak at 1743.16 cm⁻¹, within the characteristic range of 1750-1730 cm⁻¹, indicates the presence of C=O stretching vibrations of saturated esters, suggesting ester groups in the oil, likely contributing to its triglyceride content.

Aliphatic Functional Groups: Peaks at 2853.35 cm⁻¹ and 2922.39 cm⁻¹ correspond to CH₂ absorption within the ranges of 2870-2840 cm⁻¹ and near 2930 cm⁻¹, respectively. These indicate the presence of aliphatic chains, typical of the long hydrocarbon chains found in fatty acids. Additionally, a peak at 1459.84 cm⁻¹, within the range of 1470-1440 cm⁻¹, suggests the presence of CH₃ asymmetric deformation vibrations, indicating methyl groups (-CH₃) within the fatty acid chains. A further peak at 1372.82 cm⁻¹, within the range of 1390-1370 cm⁻¹, confirms symmetric CH₃ vibration splitting, suggesting branched chains. The peak at 1158.74 cm⁻¹, associated with isopropyl group vibrations (1170-1145 cm⁻¹), points to the presence of isopropyl groups, hinting at a more complex structure in the fatty acid chains or other minor components in the oil.

Olefinic Functional Groups: A peak at 3008.53 cm⁻¹, within the range typically associated with C-H stretching vibrations in olefinic compounds, indicates the presence of C-H stretching in olefinic (C=C) bonds. This suggests unsaturated components in GCSO, likely due to unsaturated fatty acids such as oleic or linoleic acid, which contain double bonds (C=C) in their hydrocarbon chains.

(CH₂)_n- Rocking Absorption: A peak at 719.55 cm⁻¹, near 720 cm⁻¹, is typical of long methylene (-CH₂-) chains in fatty acids. This absorption suggests the presence of long-chain fatty acids, which are common in many vegetable oils. This finding is consistent with the finding by Rezig et al., (2022).The FTIR analysis of GCSO was supported with the

Figure 4 below.

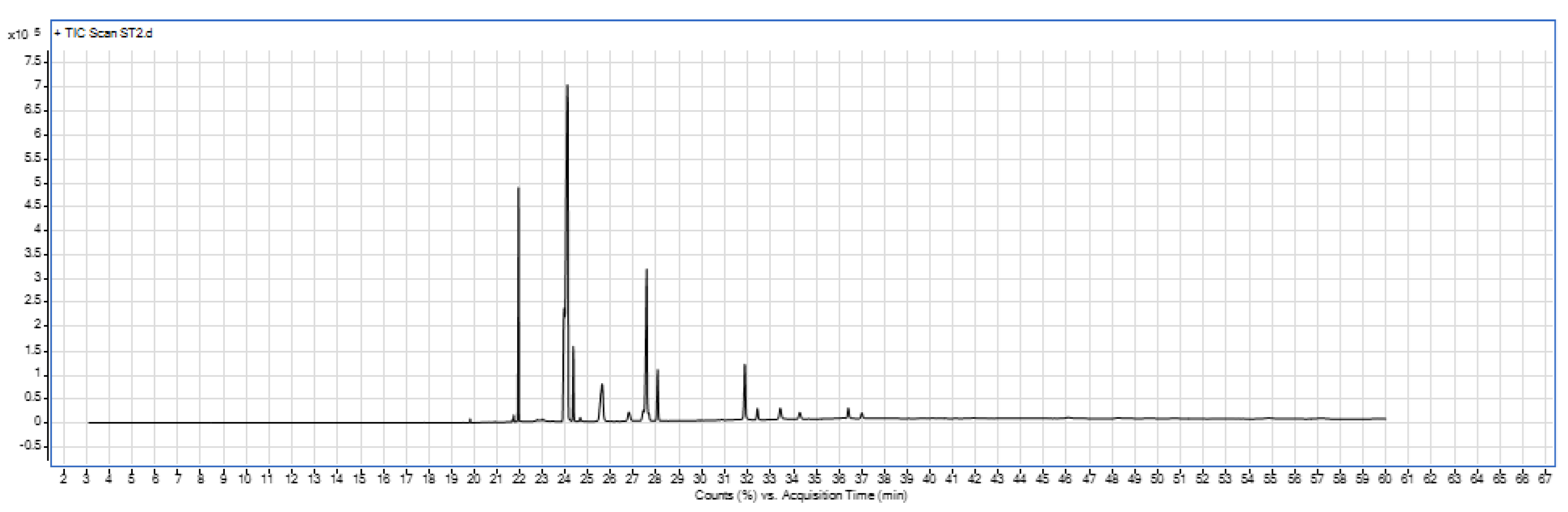

3.2.5. Fatty acid Composition of Garden Cress Seed Oil.

The GC-MS analysis of garden cress seed oil (GCSO) extracted using hexane revealed the presence of sixteen different fatty acids. The oil comprises approximately 47.81% monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), 14.26% saturated fatty acids (SFA), and 37.88% polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). The study's finding of 14.26% saturated fatty acids is close to 14.93% which was reported by Rezig et al., (2022a) and 17.51% reported by Ghazal et al., (2017). Another study by Singh & Paswan, (2017) reported slightly different values, with PUFA at 46.8% and MUFA at 37.6%. The study conducted by Rezig et al., (2022a) reported PUFA of 46.48% and MUFA of 38.59%. The discrepancies between these results and those in the current study could be attributed to factors such as soil type, climatic conditions, and the specific species of garden cress used.

Saturated fatty acids

This study identified eight saturated fatty acids. Based on their peak areas, the saturated fatty acids identified were palmitic acid, stearic acid, behenic acid, arachidic acid, and lignoceric acid, with percentage compositions of 6.47%, 2.50%, 1.49%, 2.59%, and 1.00%, respectively. The remaining three fatty acids, caprylic acid, myristic acid, and azelaic acid, were present only in trace amounts. According to Singh & Paswan, (2017), the saturated fatty acids found in Garden Cress Seed Oil (GCSO) were arachidic acid, stearic acid, and palmitic acid, with percentage compositions of 2.10%, 1.90%, and 10.30%, respectively. The study conducted by Rezig et al., (2022a), identified saturated fatty acids such as stearic acid , arachidic fatty acid, palmitic acid with percentage composition of 2.38, 3.1 and 9.45%. The palmitic acid composition (6.47%) in this study was notably different from the 10.30% which was reported by Singh & Paswan, (2017) and 9.45% reported by Rezig et al., (2022a). The stearic acid composition 2.50% also varied slightly from the 1.90% and 2.38% which was reported by Singh & Paswan, (2017) and Rezig et al., (2022a) respectively and the arachidic acid composition 2.59% was somewhat different from the 2.10% and 3.1% which was reported by Singh & Paswan, (2017) and Rezig et al., (2022a) respectively. Additionally, Ghazal et al., (2017) reported saturated fatty acids in GCSO, including palmitic acid, stearic acid, behenic acid, and arachidic acid, with percentages of 8.27%, 3.09%, 2.14%, and 4.01%, respectively.

Monounsaturated Fatty Acids

This study identified five monounsaturated fatty acids in garden cress seeds, accounting for a total of 47.81% of the fatty acids. Oleic acid was the most prevalent, making up about 28.13%. Other monounsaturated fatty acids present included erucic acid (8.01%), gondoic acid (9.95%), and nervonic acid (1.63%). The percentage composition of palmitoleic acid was present in only in trace amounts. According to Ghazal et al., (2017), the monounsaturated fatty acids found in Garden Cress Seed Oil (GCSO) included oleic acid, erucic acid, and palmitoleic acid, with abundances of 20.53%, 5.79%, and 0.19%, respectively. Singh & Paswan, (2017) reported that GCSO contained oleic acid and palmitoleic acid with percentages of 30.50% and 0.70%, respectively. Rezig et al., (2022a) reported oleic acid of 21.14%, erucic acid of 3.7% and nervonic acid of 3.45 and gondoic acid of 10.3%.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

In garden cress seeds, only two polyunsaturated fatty acids were identified: linoleic acid and linolenic acid, with abundances of approximately 6.82% and 31.05%, respectively. Ghazal et al., (2017) reported linoleic and linolenic acids with compositions of 31.29% and 11.04%, respectively. Additionally, Singh & Paswan, (2017) reported linoleic and linolenic acids with percentages of 8.60% and 32.18%, respectively. Linoleic and linolenic fatty acids had percentage abundance of 10.89 and 35.59% respectively as reported by Rezig et al., (2022a).The fatty acid composition of garden cress seed oil, as determined by GC-MS analysis, is summarized in the

Table 4 below.

Where; SFA= saturated fatty acids, MUFAs= Monounsaturated fatty acids and PUFAs =Polyunsaturated fatty acids. The percent composition of fatty acids was shown in the figure below that have values greater than 1.00 %. Garden cress seed oil contains highest amount of mono unsaturated fatty acids in which the major mono unsaturated fatty acid was oleic acid. Poly unsaturated fatty acids were present in minor quantity in GCSO. The GC-MS analysis of garden cress seed oil was provided in the

Figure 5 below.