1. Introduction

The optimal design of monetary policy is a

challenging task for central banks who always seek the ultimate objective of

price stabilization (Sliman, 2008, Sghaier and Abida, 2013; Hammami, 2016;

Turki and Lajnaf, 2024). Tunisia, like other countries, has known evolving

monetary policy conduct stages following special events such as the global

financial crisis. The most dramatic episode is the one following the transition

period, known as the 2011 revolution (Guizani, 2015). The economic situation

has been marked by a worsening of the current account and budget deficits, an

increase in the unemployment rate, and an economic recession with a fall in GDP

(Chtourou and Hammami, 2014). Price stability remains the main objective of the

monetary policy but there is no explicit nominal anchor. The Central Bank of

Tunisia (CBT) has taken steps toward a transition to inflation targeting

without real success (Zouhair and Younes, 2009; Kadria and Ben Aissa, 2014; End

et al., 2020; Trabelsi and Ben Khaled, 2023). Following the fall of the Ben Ali

regime, CBT applied an accommodative monetary policy. In 2012, monetary policy

tightened with an increase in key interest rates. In addition to the

depreciation of the dinar, inflation was fueled by the rise in oil prices and

wage increases. There was also a mismatch between supply and demand for goods

and services. Banks granted credit to potentially insolvent customers,

increasing non-performing loans (Charfi, 2016). The situation seems not to be

the best with the arrival of COVID-19, plunging the economy back into recession

and further uncertainty (Mansour and Ben Salem, 2020). The spread of the

epidemic and the need for short-, medium- and long-term visibility suggest that

viewers feared the worst, either a surge in expansion versus negative growth or

a circumstance of Stagflation with devastating financial and social

consequences. Pandemics, crises, and political instability are perturbing

events that generate global uncertainty (Gupta and Jooste, 2018). In this

regard, Cascaldi-Garcia et al. (2021) show that there has been a growing

emphasis among scholars, decision-makers, and economic agents on the impact of

risk and uncertainty on financial markets and economic expectations.

It is widely admitted that uncertainty shocks can

drive aggregate fluctuations and explain monetary policy transmission

mechanisms in modern business cycle research (Bloom, 2009; Basu and Bundick,

2017; Fernández-Villaverde and Guerrón-Quintana, 2020; Cho et al., 2021;

Bianchi et al., 2023) but the related measures are expansive and categorized

(Caldara et al., 2016; Kozeniauskas and Veldkamp, 2018; Cascaldi-Garcia et al.,

2021). We focus on global shocks related to economic, financial, pandemic, and

oil price uncertainties. We depart from the view that global and spillover

shocks have a larger impact on monetary policy and economic output than local

shocks (e.g., Bloom, 2009; Colombo, 2013; Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes, 2013; Handley, 2014; Handley and

Limao, 2015; Jones and Olson, 2015; Carriero et al., 2015; Cheng, 2017; Azad,

2022). Using a novel Bayesian VAR with time-varying coefficients, we

disentangle the response of the Tunisian monetary policy to multiple

uncertainty shocks. As Geraci and Gnabo (2018) put it, we create a statistical

framework based on the market that models the dynamic nature of connections

between financial institutions using Bayesian estimation of time-varying

parameter vector autoregressions (TVP-VAR). Unlike the classical approach,

which favors abrupt, frequently unjustified changes in interconnectedness, the

framework permits connections to evolve gradually over time. The approach

enables us to reconstruct a dynamic network of directed spillover and global

effects. As Fischer et al. (2023) claimed, the core of our estimation technique

is the specification of appropriate shrinkage priors that allow us to reduce

coefficients toward zero concerning effect modifiers that are not important.

Since the TVP-VARs depend linearly on the action modifiers, these priorities

allow combinations of multiple motion laws and can endogenously determine the

correct motion law for the parameters. The model examines factors affecting

parameter variation over time. Another flexible solution is to rely on Local

Projections (LPs). Jordà and Taylor (2024, p.1) stated that “Local

projections (or LPs) are a sequence of regressions where the outcome, dated at

increasingly distant horizons, is regressed on the intervention (directly, if

randomly assigned; or perhaps instrumented, if not), conditional on a set of

controls that include lags of both the outcome and the intervention, as well as

other exogenous or predetermined variables”. Our results indicate that

different uncertainty measures explain a statistically significant portion of

macroeconomic fluctuations, causing a decline in industrial production and a

rise in both the money market rate and consumer price index. Our approach is

inspired by Dery and Serletis (2021a, 2021b). We differ from their

contributions in three main aspects: We analyze a wide range of uncertainty

shocks, including real and monetary policy shocks, surpassing previous

literature that often focused on only one aspect of local uncertainty. We

assess the forecasting ability of

uncertainty shock measures for real economic activity and monetary policy,

identifying which measure has predictive power. We use Toda and Yamamoto's

(1995) Granger causality test to evaluate the relationship between uncertainty

measures and industrial production, the consumer price index, monetary

aggregates, the real effective exchange rate, and the money market rate. Third,

while risk can be a potential informative tool in explaining Tunisian monetary

policy, we discard the related measures as this goes beyond the scope of the

paper and is left for future investigation.

Our paper also takes an intriguing step to

highlight specific mechanisms that drive the impact of uncertainty on the real

economy and prices by calling the irreversibility theory. This theory suggests

that firms often delay investment and hiring during uncertain times. There are

two main ways in which uncertainty affects firms. First, the real option, given

the irreversibility of the investment, shows the importance of waiting and

being flexible when making investment decisions in response to uncertainty (Bernanke,

1983; Bertola and Caballero, 1994; Caballero and Pindyck, 1996). Second, during

periods of uncertainty, higher risk premiums increase the amount of money to

compensate borrowers for losses due to increased uncertainty (Bhatia and

Pratap, 2024). Therefore, when faced with high uncertainty, agents adopt more

strategic plans, which leads to reduced long-term investments. In our context,

this implies investigating the effectiveness of the money market rate as a

monetary policy instrument of CBT during high uncertainty times in a VECM where the interest rate interacts with

uncertainty variables. If the interest rate does not significantly impact the

relationship between uncertainty indices and the real economy and prices, it

indicates that the interest rate is a less influential tool, leading economic

agents to adopt a “wait and see” (precautionary) approach. This investigation

enhances the uniqueness of our research. Our contribution seeks to address a

significant research gap in the Tunisian context.

The layout of the paper is given as follows. In Section 2, we provide theoretical and empirical

arguments about transmitting channels of uncertainty shocks to emerging

countries, including Tunisia. Section 3

describes the process of data collection and empirical strategy. We expose and

discuss our findings in Section 4. Section 5 concludes with policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Monetary Policy and Global Uncertainty: Spillover Effects in Emerging Economies

The discourse on the impact of global uncertainty

on monetary policy is grounded in several theoretical frameworks. Frankel

(2010) delineated the distinguishing characteristics of developing countries

compared to industrialized nations, noting their heightened susceptibility to

supply shocks and diminished credibility regarding price stability. In

conjunction with this perspective, Castelnuovo (2023) examined the nonlinear

effects of uncertainty shocks and their pivotal role in driving business

cycles. Furthermore, the review by Fernández-Villaverde and Guerrón-Quintana

(2020) scrutinized various theoretical frameworks to elucidate the transmission

channels of uncertainty shocks within Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium

(DSGE) models. This analysis highlights the critical issues related to

communication and credibility that significantly influence monetary policy

decisions.

Survey studies conducted by Bloom (2014), Carriero

et al. (2021), and Castelnuovo (2023) have underlined the critical need for

further exploration of the macroeconomic effects of spillover and global

uncertainty. A common feature emerges: uncertainty plays a significant role as

a driver of the business cycle, necessitating a comprehensive analysis of its

nonlinear effects, particularly on financial frictions and policy interventions

(Lakdawala et al., 2021).

A substantial body of empirical research has sought

to elucidate the effects of global policy uncertainty on emerging markets. Azad

and Serletis (2022a) showed that US monetary policy uncertainty adversely

affects the macroeconomic and financial fundamentals of emerging economies.

Complementing these findings, Prabheesh et al. (2021) identified that

uncertainty arising from the COVID-19 pandemic attenuated the effectiveness of

monetary policy transmission to inflation. However, some economies succeeded in

stabilizing credit and output despite heightened uncertainty. The work of

Lastauskas and Nguyen (2024) further elucidated how US monetary policy shocks

instigated co-movements in international financial variables, thereby

contributing to a global financial cycle that interconnected diverse economic

landscapes.

This interconnectedness becomes particularly

salient when examining US monetary policy uncertainty and its substantial

repercussions for emerging markets (Bhattarai et al., 2017; Olanipekun and

Olasehinde-Williams, 2022). Aor et al. (2021) found that shocks stemming from

US monetary policy uncertainty had temporary negative effects on real equity

prices across both advanced and emerging economies. Additionally, Park and Kim

(2021) highlighted that the US monetary policy in the post-quantitative easing

era adversely affected the KRW/USD exchange rate in South Korea, while exerting

minimal influence on domestic macroeconomic variables such as output and

consumer prices. Anaya et al. (2017) observed that

emerging markets typically responded to unconventional US monetary policy

shocks by easing their monetary stances, with these shocks being transmitted

through international capital flows. Echoing this sentiment, Bhattarai et al. (2020) illustrated how US uncertainty

shocks resulted in reductions in output and consumer prices in emerging

markets, thus complicating monetary policy responses. This evidence points to a

negative effect of US monetary tightening brought on by a more hawkish policy

stance (Ahmed et al., 2021; De Leo et al., 2022). As a result, trade-offs are

likely to occur when inflation expectations are firmly anchored in emerging

economies.

The implications of world uncertainty for monetary

policy have also been explored across various contexts (see Canh et al., 2020).

Gu et al. (2021) investigated the effects of global economic policy

uncertainty, revealing its significant empirical impact on stock volatility in

nine emerging economies. This influence extended to Latin America, where Aytaç

and Saraç (2022) reported that economic policy uncertainty led to rising

inflation and interest rates in several countries. The adverse long-term

effects of economic policy uncertainty on economic expectations are further

depicted by Al-Thaqeb and Algharabali (2019), Al-Thaqeb

et al. (2022), and Ben Cheikh et al. (2023). Additionally, Montes and

Marcelino (2023) demonstrated that heightened economic policy uncertainty

amplified disagreement among economic agents regarding fiscal and monetary

policy, thereby complicating the navigation of uncertainty in policymaking (see

Athari et al., 2022; Anderl and Caporale, 2023; Pagliacci, 2023; Sengupta et

al., 2024).

The interconnected nature of global financial

systems is further reinforced by the influence of US financial stress on the

monetary policies of emerging markets. Financial stress pertains to

interruptions to normal economic activities and the ongoing volatility observed

in financial markets (Das et al., 2018; Choi and Shim, 2019; Polat, 2020; Jana

et al., 2022; Gosh et al., 2024). Tng and Kwek (2015) noted that increased

financial stress resulted in tighter credit conditions and diminished economic

activity across ASEAN countries, highlighting the necessity for targeted policy

measures to restore financial stability. This assertion was corroborated by

Ghosh et al. (2024), who elucidated how financial stress reflects disruptions

to regular economic activities, particularly during volatile regimes such as

the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, Fink and Shüler (2015) and Niepmann et al. (2021)

emphasized that US systemic financial stress shocks significantly drove

economic dynamics and fluctuations in emerging markets, reinforcing the

interconnectedness that shapes monetary policy responses. The result

complements previous studies such as Lown and Morgan (2006), Helbling et al. (2011), Baxa et al., 2013; Kalemli-Ozcan et al.

(2013), Hristov et al. (2012), Gilchrist et al. (2014), and Schüler

(2014). Moreover, Tobal and Menna (2020) contended that the interplay

between monetary policy and financial stress in emerging markets is inherently

complex. The authors advocated for the development of models capable of

capturing financial crises as endogenous phenomena, stemming from the accumulation

of financial imbalances. Such insights are pivotal for enhancing our

understanding of the broader economic implications of uncertainty in the

contemporary global landscape.

In this context, oil price uncertainty has emerged

as a critical factor with significant implications for monetary policy (Azad

and Serletis, 2022b). Ghosh et al. (2021) illustrated how oil prices, in

conjunction with financial volatility and economic policy uncertainty,

influenced inflation expectations in India. Chowdhury (2024) argued that oil

price uncertainty significantly contributed to inflation, particularly in

developing countries, while highlighting the importance of differentiating

between nominal and real uncertainty to better understand output growth.

Additionally, Abiad and Qureshi (2021) found that oil price uncertainty

negatively affects macroeconomic activity, particularly under zero lower-bound

constraints on monetary policy. Su et al. (2021) argued that oil price shocks

positively affect economic policy uncertainty when oil markets experience

supply shocks, a result supported by Shahbaz et al. (2023). Evidence about the

interaction of economic policy uncertainty and oil price is found in Sun et al.

(2020), Chen et al. (2020), and Lin and Bai (2021).

The literature

review highlights the complex relationship between global uncertainty,

spillover effects, and monetary policy in emerging markets. Insights from

theoretical frameworks and empirical studies highlight the challenges

policymakers encounter in managing uncertainty in the interconnected global

economy (Baharumshah et al., 2016).

2.2. Tunisia's Monetary Policy in the Face of Global and Domestic Shocks

The spillover effects of global uncertainty shocks

on Tunisia's monetary policy were the focus of extensive empirical research,

revealing the complex challenges faced by the CBT in stabilizing the economy.

Trabelsi and Ben Khaled (2023) demonstrated that global uncertainties, as

captured by the World Uncertainty Index, significantly contributed to

inflationary pressures in Tunisia, hindering the country's transition to an

inflation-targeting regime. They argued that adopting a flexible exchange rate

and increasing monetary policy transparency was crucial for overcoming these

barriers. In a complementary study, Turki and Gabsi

(2023) found that global uncertainty adversely affects aggregate demand and

economic activity, rendering conventional monetary tools insufficient during

periods of heightened risk. The domestic dimension of uncertainty was also

critical. Belhoula (2024) showed that local economic policy uncertainty

resulted in negative shifts in growth, consumption, and industrial output,

underscoring the need for consistent and coherent policy frameworks. Similarly,

Jallouli and Yalouli (2022) highlighted the

limitations of monetary policy when subjected to uncertainty shocks from

external crises, including pandemics, terrorism, and political unrest. Their

findings suggested that Tunisia's monetary policy needs refinement to withstand

such volatility. Moving toward a more structured approach, Guizani and Wierzbowska (2022) reported a shift toward

rule-based monetary frameworks in Tunisia and Morocco during the post-Arab

Spring period, a shift further supported by Mimoun et al. (2024), who advocated

for a rule-based inflation-targeting regime. They emphasized that supply-side

policies were necessary to promote growth and correct fiscal imbalances. In a

broader African context, Moyo and Phiri (2024) identified

that countries more responsive to U.S. monetary policy shocks tended to

experience lower inflation, suggesting that Tunisia could have benefited from

improved coordination with global monetary authorities. On the financial front,

Guenichi and Nejib (2022) explored the negative

impacts of pandemic-related uncertainty on Tunisia’s stock market, noting the

market's resilience in late 2021. Lastly, Neaime and

Gaysset (2022) underscored the vulnerability of Tunisia and other MENA

countries to external oil price shocks, recommending non-conventional monetary

tools to mitigate these risks. Trabelsi (2024) further

emphasized the role of uncertainty in driving Tunisia’s macroeconomic

fluctuations, reinforcing the importance of robust policy responses.

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Data Collection

We collect macroeconomic and financial data from

various databases (see Table 1). After a

cleaning process, we get a balanced sample of 90 observations running from

1997q1 to 2019q2, except for the variable (LOG(USFSI)) whose values end in

2016q4. The variables of interest comprise the Global Economic Policy

Uncertainty Index which is a GDP-weighted average of 21 national economic

policy uncertainty indices. There are two versions of the Index - one based on

current-price GDP measures (LOG(GEPUC)), and one based on PPP-adjusted GDP

(LOG(GEPUP)). To assess economic uncertainty linked to policy, Baker et al.

(2016) developed an index based on three key components. The first and most

adaptable component measures the frequency of policy-related economic

uncertainty in newspaper articles. The World Uncertainty Index (LOG(WUITUN1))

is constructed by Ahir et al. (2022). They created quarterly indices of

economic uncertainty for 143 countries starting in 1996, utilizing the

frequency of the term "uncertainty" (and its variations) in the

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) country reports. These reports cover

significant political and economic events in each nation, as well as analysis

and forecasts of political, policy, and economic conditions. We select the

index related to the Tunisian context. We also use the US Monetary Policy

Uncertainty Index (LOG(USMPUI)) from Baker et al. (2016). The authors

identified newspaper articles that meet specific E, P, U, and M criteria. This

involves flagging articles that contain at least one term from each of the

following categories:

⁻ E: economic, economy

⁻ P: congress, legislation, white house, regulation, federal reserve, deficit

⁻ U: uncertain, uncertainty

⁻ M: Federal Reserve, the Fed, money supply, open market operations, quantitative easing, monetary policy, fed funds rate, overnight lending rate, Bernanke, Volker, Greenspan, central bank, interest rates, fed chairman, fed chair, lender of last resort, discount window, European Central Bank, ECB, Bank of England, Bank of Japan, BOJ, Bank of China, Bundesbank, Bank of France, Bank of Italy.

The final indices are created using scaled

frequency counts of newspaper articles that mention monetary policy

uncertainty. The definition of "monetary policy uncertainty" differs

for each MPU index. "Scaling" is applied to account for variations in

the total number of articles across different newspapers and over time.

The US Financial Stress Indicator (LOG(USFSI)) is

developed by Püttmann (2018) using article titles from five major US

newspapers: the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street

Journal, and Washington Post. Püttmann (2018) follows a three-step process,

beginning by defining eleven topics related to financial markets, which are

identified through 120 specific keywords. In the second step, the sentiment of

these titles is assessed using four sentiment dictionaries, determining whether

each title has a net negative connotation. Finally, Püttmann (2018)

standardizes the monthly financial sentiment index to a mean of 100 with a unit

standard deviation, averaging across various newspaper-dictionary combinations

to create his quarterly FSI. All variables are transformed using the natural

logarithm. Finally, we consider the shocks from the Oil Price Uncertainty Index

(LOG(OILUI)) according to Abiad and Qureshi (2023). The method is analogous to

measuring economic policy uncertainty. The analysis focuses on a collection of

English-language articles containing a minimum of 100 words from 50 newspapers

globally. The selection process excludes non-standard news items, such as

sports articles, editorials, abstracts, advertisements, sponsored content,

blogs, opinion pieces, country profiles, transcripts, press releases, and

similar content.

Table 1.

Summary of variables.

Table 1.

Summary of variables.

| Variable |

Acronym |

Definition |

Source |

| Economic activity |

LOG(IPIT) |

Industrial production index, all items |

National Institute of Statistics (NIS) |

| Inflation |

LOG(CPI) |

Consumer price index, all items |

NIS |

| Monetary aggregate |

LOG(M2TND) |

Money supply converted from monthly data |

Central Bank of Tunisia (CBT) |

| Money Market rate |

TMM |

Money market rate converted from monthly data |

CBT |

| Real Effective Exchange rate |

LOG(TCER) |

Real effective exchange rate, convertedfrom monthly data. It is the Tunisian dinar against a basket of foreign currencies divided by price deflator. If TCER increases, it indicates an appreciation of local money. The latter has strengthened against foreign currencies. |

International Financial Statistics (IFS) |

| Global Economic Uncertainty |

LOG(GEPUC) |

Global Economic Policy Uncertainty index - based on current-price GDP developed by Baker et al. (2016), convertedfrom monthly data |

https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ |

| Global Economic Uncertainty |

LOG(GEPUP) |

Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index - based on PPP-adjusted GDP developed by Baker et al. (2016), convertedfrom monthly data |

https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ |

| World Uncertainty |

LOG(WUITUN1) |

World Uncertainty Index related to Tunisia developed by Ahir et al. (2022) |

https://www.worlduncertaintyindex.com/ |

| Monetary Policy Uncertainty |

LOG(USMPUI) |

US Monetary Policy Uncertainty convertedfrom monthly data |

https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ |

| Financial Stress |

LOG(USFSI) |

US Financial Stress Index |

https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ |

| |

|

|

|

| Oil uncertainty |

LOG(OILUI) |

Oil Price Uncertainty Index, convertedfrom monthly data |

https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ |

Summary statistics are available in Table 2. The mean values of the variable range

from 0.17 (LOG(WUITUN1)) to 10.25 (LOG(M2TND)), with LOG(M2TND) having the

highest average, indicating the importance of money supply in the dataset.

Standard deviations suggest moderate variability, with TMM (money market rates)

being the most volatile (0.97) and LOG(USFSI) the most stable (0.008). Skewness

values are generally close to zero, indicating relatively symmetric

distributions, although LOG(WUITUN1) is positively skewed (1.022). Kurtosis

values vary, with most variables being close to 3, indicating a normal

distribution shape, except for LOG(CPI) and LOG(M2TND), which have flatter

distributions. The results of the Jarque-Bera test indicate that LOG(IPIT) and

LOG(WUITUN1) are not normally distributed (p-value = 0.00396, p-value =

0.000388, respectively). Most other variables are closer to normality.

Observations are consistent across variables, with a slight decrease for

LOG(USFSI).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Statistics |

LOG(IPIT) |

LOG(CPI) |

LOG(M2TND) |

TMM |

LOG(TCER) |

LOG(GEPUC) |

LOG(GEPUP) |

LOG(WUITUN |

1)LOG(USMPUI) |

LOG(USFSI) |

LOG(OILUI) |

| Mean |

4.493770 |

4.556945 |

10.24873 |

5.275107 |

4.666892 |

4.672641 |

4.670963 |

0.165609 |

4.647079 |

4.617030 |

4.538725 |

| Median |

4.521680 |

4.524614 |

10.28769 |

5.000000 |

4.638794 |

4.683143 |

4.670338 |

0.106669 |

4.645387 |

4.617074 |

4.621765 |

| Maximum |

4.628232 |

5.038763 |

11.26710 |

7.840000 |

4.893060 |

5.520925 |

5.580722 |

0.703028 |

5.495236 |

4.647271 |

5.776230 |

| Minimum |

4.241714 |

4.204875 |

9.074444 |

3.236670 |

4.298770 |

4.014913 |

4.044697 |

0.000000 |

3.770833 |

4.604242 |

2.717981 |

| Std. Dev. |

0.093333 |

0.234030 |

0.656923 |

0.974519 |

0.160428 |

0.381576 |

0.388171 |

0.182125 |

0.368397 |

0.008561 |

0.650636 |

| Skewness |

-0.855104 |

0.347672 |

-0.171137 |

0.486475 |

-0.181783 |

0.240665 |

0.326950 |

1.022088 |

-0.017403 |

0.676738 |

-0.523287 |

| Kurtosis |

3.158268 |

1.976452 |

1.756898 |

2.788833 |

2.184759 |

2.274641 |

2.340432 |

3.099567 |

2.704734 |

3.695873 |

3.056681 |

| Jarque-Bera |

11.06197 |

5.741832 |

6.234205 |

3.717089 |

2.987991 |

2.841840 |

3.234809 |

15.70714 |

0.331475 |

7.720455 |

4.119487 |

| Probability |

0.003962 |

0.056647 |

0.044285 |

0.155899 |

0.224474 |

0.241492 |

0.198413 |

0.000388 |

0.847269 |

0.021063 |

0.127487 |

| Sum |

404.4393 |

410.1250 |

922.3858 |

474.7596 |

420.0203 |

420.5377 |

420.3866 |

14.90482 |

418.2371 |

369.3624 |

408.4852 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. |

0.775282 |

4.874528 |

38.40778 |

84.52223 |

2.290610 |

12.95840 |

13.41025 |

2.952091 |

12.07878 |

0.005790 |

37.67609 |

| Observations |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

80 |

90 |

The pairwise correlation analysis reveals several

key relationships among the economic and financial variables (see Table 3). Industrial production (LOG(IPIT))

shows strong positive correlations with both consumer price index (LOG(CPI),

0.79) and money supply (LOG(M2TND), 0.86), suggesting that higher industrial

activity is associated with inflation and increased money supply. LOG(CPI) and

LOG(M2TND) are almost perfectly correlated (0.99), reflecting a close link

between inflation and monetary expansion. In contrast, money market rates (TMM)

exhibit strong negative correlations with LOG(IPI) (-0.81), LOG(CPI) (-0.82),

and LOG(M2TND) (-0.87), highlighting the typical inverse relationship where

higher interest rates suppress industrial output and inflation.

Similarly, the real effective exchange rate

(LOG(TCER)) has strong negative correlations with LOG(CPI) (-0.95) and

LOG(M2TND) (-0.97), indicating that inflationary pressures and monetary

expansion may reduce energy consumption. Moderate positive correlations are

observed between global economic policy uncertainty (LOG(GEPUC)) and both

LOG(CPI) (0.62) and LOG(M2TND) (0.61), implying that uncertainty is associated

with rising inflation and monetary supply. Oil prices (LOG(OILUI)) also show a

moderate positive correlation with industrial production (0.58), suggesting

that higher oil prices tend to accompany economic growth.

In contrast, US monetary policy uncertainty

(LOG(USMPUI)) exhibits weak and insignificant correlations with other

variables. US financial stress (LOG(USFSI)), however, is negatively correlated

with LOG(CPI) (-0.62) and LOG(M2TND) (-0.58), suggesting that financial stress

tends to rise during periods of low inflation and money supply. Additionally,

LOG(USFSI) is positively correlated with TMM (0.50), signifying higher

financial stress during times of increased interest rates.

Table 3.

Pairwise correlation matrix.

Table 3.

Pairwise correlation matrix.

| Covariance Analysis: Ordinary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Date: 09/30/24 Time: 14:43 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sample: 1997Q1 2016Q4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Included observations: 80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Balanced sample (listwise missing value deletion) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Correlation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Probability |

LOG(IPI ) |

LOG(CPI) |

LOG(M2TND) |

TMM |

LOG(TCER) |

LOG(GEPUC) |

LOG(GEPUP) |

LOG(WUITUN1) |

LOG(USMPUI) |

LOG(USFSI) |

LOG(OILUI) |

| LOG(IPI ) |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(CPI) |

0.794720 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(M2TND) |

0.864751 |

0.985421 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TMM |

-0.805478 |

-0.815654 |

-0.870187 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(TCER) |

-0.850788 |

-0.951899 |

-0.972113 |

0.850318 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(GEPUC) |

0.440426 |

0.620187 |

0.610776 |

-0.492474 |

-0.539610 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(GEPUP) |

0.489974 |

0.667960 |

0.662053 |

-0.549543 |

-0.598008 |

0.994287 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

|

| |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(WUITUN1) |

0.406588 |

0.653235 |

0.644516 |

-0.617375 |

-0.628559 |

0.552352 |

0.577128 |

1.000000 |

|

|

|

| |

0.0002 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

----- |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(USMPUI) |

-0.031563 |

0.107769 |

0.053016 |

0.111063 |

0.021264 |

0.359261 |

0.317995 |

0.066827 |

1.000000 |

|

|

| |

0.7811 |

0.3413 |

0.6405 |

0.3267 |

0.8515 |

0.0011 |

0.0040 |

0.5559 |

----- |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(USFSI) |

-0.367922 |

-0.622911 |

-0.577258 |

0.500546 |

0.585996 |

-0.049338 |

-0.088998 |

-0.534577 |

-0.082806 |

1.000000 |

|

| |

0.0008 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.6638 |

0.4324 |

0.0000 |

0.4652 |

----- |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LOG(OILUI) |

0.577337 |

0.399850 |

0.475859 |

-0.536726 |

-0.444288 |

0.113824 |

0.154517 |

0.036029 |

0.015791 |

-0.138382 |

1.000000 |

| |

0.0000 |

0.0002 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.3147 |

0.1711 |

0.7510 |

0.8894 |

0.2209 |

----- |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Note: See details in Table 1 for definitions. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.2. Empirical Methodology

3.2.1. Bayesian TVC VAR

Standard Vector Autoregressive (VAR) models impose

the constraint that the coefficients are constant through time. This is often

not true of macroeconomic relationships (Sims, 1980). Consequently, in recent

years VAR estimators that allow coefficients to change have become popular (Chan and Eisenstat, 2018; Geraci and Gnabo, 2018; Kang

et al., 2019). The stochastic volatility of a shock is written as follows:

where

is a vector of time-varying intercepts,

is a matrix with (k,1) dimension, it is the vector

of our observed variables.

are matrices of time-varying coefficients

with

dimension, and

is the variance-covariance matrix of the error

terms with

dimension. Assuming a recursive model, we decompose

as follows:

t

be the stacked row vector of

and

is the stacked row vector of the bottom part of

the triangular matrix

. Further, we posit the log-volatilities vector

such that:

The time-varying parameters follow a random walk process

and are given by the following expressions:

We have, then, , for .

Equation (2) can be further modeled as follows. The

time-varying intercepts and the parameters associated with lagged variables are

included in a vector of dimension

:

,

,

,….,

. The time-varying coefficients that characterize

contemporaneous relationships between variables are contained in

. These are the free elements of

stacked by rows. Given that,

, Equation (1) can be rewritten as follows:

with and is a matrix of and has a dimension of .

The above equation can be further expressed as a

generic state space model:

where , and , which has the dimension . As Eisenstat et al. (2016) put it, this form

enables a smooth drawing sampler of and simultaneously instead of separately as made by

Primiceri (2005).

3.2.2. Local Projections (LPs)

Jordà and Taylor (2024) provide a simple dynamic

setting where

denotes the outcome variable, and

is a vector of exogenous or predetermined control

variables, which include lags of both the outcome variable and the policy

intervention, denoted as

. To assess the effect of a policy intervention at

the current time on the average future outcome, compared to what would happen

in the absence of such an intervention, we model the impulse response function

as follows:

Here, stands for the size of the shock. It is common to

set , for instance, a one standard deviation shift in a

variable. The subscript highlights the causal relationship between the

intervention and the outcome. The value of is not of much importance if linear

modeling is established. If the non-linear relationship is hypothesized, might affect the shock variable.

Similarly to Jordà (2005), the LP of an outcome

variable on a shock is a linear regression that is expressed below:

We can easily infer from Equation(3) that . We assume that is exogenous and thus . Equation (4) is then estimated by Ordinary Least

Squares (OLS).

The assumption of a linear relationship seems to be

narrow at first glance. However, Equation (4) is re-estimated for each

subsequent horizon , pertaining to a semi-parametric estimation of . Although are likely to be serially correlated up to

h lags, this anomaly does not have any consequences on the consistency of . Unlike VAR frameworks, Equation (4) is a single

equation rather than a system of equations.

As Jordà and Taylor (2024) stated, linearity

implies the following considerations:

Shocks

have symmetric effects on the outcome variable:

.

If 1% increases in a shock leads to a decline by

in

the outcome variable, then decreases in the former leads to a rise by

in

the latter variable.

The

impulse responses are independent to the current state of the controls:

.

The impulse responses are proportional to the size of the

shock:

.

When proceeding to the estimation of impulse

response functions, two issues arise: the persistence of data and long

horizons. Montiel Olea and Plagborg-Møller (2021) argued that lag augmentation

deals with both issues and offsets serial correlation in the residuals. For

this purpose, we use the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select the

optimal lag. In doing so, LPs encompass a robust inference compared to VAR.

4. Results and Discussion

3.3. Unit Root Test

An essential step to estimate VAR and its variants

is to check stationarity properties of the underlying time series.

There are mainly two popular tests: first, the

Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) proposed by Dickey and Fuller (1979). The authors

consider the following random walk

Dickey and Fuller (1979) apply the maximum

likelihood method to derive an estimator of .

Second, the Phillips-Perron (PP) test by Perron and

Phillips (1989) suggests a slight modification to Equation (5):

Further, the authors use a semi-parametric approach

to estimate .

In both tests, the null hypothesis postulates that is not stationary (has a unit root) if while the alternative hypothesis assumes stationary if . Table 4.a

displays the unit root results associated to ADF and PP for all assumptions

about the intercept and trend. All variables are stationary after taking the

first difference. They are integrated into order 1 (I(1)).

For robustness check, we also run a unit root test

with structural breaks (

). We use the Zivot-Andrews procedure for this

purpose. The test of Zivot and Andrews (2002) allows for endogenous breakpoints

and tests the null hypothesis of a unit root against the alternative that

is stationary with a structural break in

intercept, in trend, or both in trend and intercept. Equation (7) is identical

to Equation (5) but includes two dummies

:

The results are available in Table 4.b and suggest again that all variables

are stationary in the first difference (hence, integrated of order 1 (I(1)).

Based on these findings, both Bayesian TVC VAR and

LPs should be implemented on variables by taking their first differences.

3.4. Bayesian TVC VAR

We rely on AIC to select the optimal lag for the

model. The results for all VAR models including successive global and spillover

uncertainty measures are available in the supplementary file (see Tables S.1-S.6). To compute posterior estimates, we

draw 20000 samples after discarding the initial 1000 samples following Chan and Jeliazkov (2009). We further set .

Table 4.

a. Unit root test results (PP, ADF).

Table 4.

a. Unit root test results (PP, ADF).

| |

PP |

ADF |

PP |

ADF |

PP |

ADF |

|

PP |

ADF |

PP |

ADF |

PP |

ADF |

|

| |

With Constant |

With Constant & Trend |

Without Constant & Trend |

|

With Constant |

With Constant & Trend |

Without Constant & Trend |

|

| Level |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

First diffirence |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

t-Statistic |

|

| LOG(IPIT) |

-3.7541** |

-2.8165* |

-6.9377*** |

-0.4333 |

1.0610 |

2.0226 |

d(LOG(IPIT)) |

-57.6744*** |

-7.1762*** |

-81.5293*** |

-6.8185*** |

-50.1326*** |

-7.8624*** |

|

| LOG(CPI) |

5.8439 |

2.5732 |

3.2249 |

0.9780 |

16.6097 |

2.4372 |

d(LOG(CPI)) |

-13.9136*** |

-2.1000 |

-15.1952*** |

-0.5282* |

-8.1759*** |

-3.1631 |

|

| LOG(M2TND) |

-1.1892 |

-1.4069 |

-1.2087 |

-1.8450 |

15.1049 |

2.8422 |

d(LOG(M2TND)) |

-23.3846*** |

-3.4171** |

-22.9991*** |

-1.0244** |

-20.2210*** |

-3.6386 |

|

| TMM |

-2.6698* |

-2.6487* |

-1.8776* |

-1.9167 |

-1.3202 |

-1.3038 |

d(TMM) |

-13.9915** |

-13.8691*** |

-14.2226*** |

-13.8654*** |

-13.9899*** |

-14.2432*** |

|

| LOG(TCER) |

-0.9732 |

-0.9082 |

-1.3925 |

-1.4108 |

-1.4716 |

-1.4148 |

d(LOG(TCER)) |

-16.9860** |

-16.9264*** |

-16.9754*** |

-16.8497*** |

-16.9525*** |

-16.9160*** |

|

| LOG(GEPUC) |

-2.6411* |

-2.0721 |

-5.3591*** |

-5.5868*** |

0.6670 |

0.3085 |

d(LOG(GEPUC)) |

-29.0376*** |

-14.1465*** |

-28.9851*** |

-14.1532*** |

-28.5961*** |

-14.1246*** |

|

| LOG(GEPUP) |

-2.4898 |

-1.9388 |

-5.6911*** |

-5.6911*** |

0.7751* |

0.3388 |

d(LOG(GEPUP)) |

-30.7488*** |

-14.0114*** |

-30.7367*** |

-14.0165*** |

-29.8910*** |

-13.9895*** |

|

| LOG(WUITUN1) |

-6.9403*** |

-4.7282*** |

-7.0385*** |

-4.7454*** |

-2.7749*** |

-1.7372 |

d(LOG(WUITUN1)) |

-34.6848*** |

-14.9958*** |

-35.0112*** |

-15.0287*** |

-34.4107*** |

-14.9632*** |

|

| LOG(USMPUI) |

-11.2281*** |

-7.5443*** |

-12.0214*** |

-8.2664*** |

-0.4072 |

-0.3089 |

d(LOG(USMPUI)) |

-86.9210*** |

-14.5763*** |

-84.7686*** |

-14.5957*** |

-85.2785*** |

-14.5566*** |

|

| LOG(USFSI) |

-5.2392*** |

-3.6229*** |

-5.6685*** |

-4.0197*** |

-0.1890 |

-0.1260 |

d(LOG(USFSI)) |

-39.5189*** |

-16.6895*** |

-39.8447*** |

-16.7185*** |

-39.1002*** |

-16.6616*** |

|

| LOG(OILUI) |

-6.9148*** |

-3.7872*** |

-8.9824*** |

-5.3565*** |

-0.5299 |

-0.1653 |

d(LOG(OILUI)) |

-70.5183*** |

-13.1279*** |

-83.6227*** |

-13.1415*** |

-66.4084*** |

-13.1188*** |

|

Table 4.

b. Unit root test results (ZA).

Table 4.

b. Unit root test results (ZA).

| |

With Constant |

Break date |

Conclusion |

With Trend |

Break date |

Conclusion |

With Constant & Trend |

Break date |

Conclusion |

|

With Constant |

Break date |

Conclusion |

With Trend |

Break date |

Conclusion |

With Constant & Trend |

Break date |

Conclusion |

| Level |

t-Statistic |

|

|

t-Statistic |

|

|

t-Statistic |

|

|

First diffirence |

t-Statistic |

|

|

t-Statistic |

|

|

t-Statistic |

|

|

| LOG(IPIT) |

-3.021055 |

2006Q2 |

unit root |

-2.950350 |

2008Q |

unit root |

-4.584448 |

2007Q1 |

unit root |

d(LOG(IPIT)) |

-9.198574 |

2006Q2 |

stationary |

-8.977624 |

2001Q4 |

stationary |

-9.415592 |

2004Q1 |

stationary |

| LOG(CPI) |

0.290306 |

2004Q1 |

unit root |

-1.092325 |

2010Q4 |

unit root |

-1.110762 |

2011Q2 |

unit root |

d(LOG(CPI)) |

-4.548052 |

2004Q3 |

unit root |

-4.934924 |

2015Q4 |

stationary |

-5.365860 |

2015Q2 |

stationary |

| LOG(M2TND) |

-2.442948 |

2014Q4 |

unit root |

-2.634045 |

2010Q4 |

unit root |

-3.045702 |

2008Q1 |

unit root |

d(LOG(M2TND)) |

-9.489015 |

2011Q2 |

stationary |

-9.098713 |

2008Q1 |

stationary |

-9.551113 |

2001Q1 |

stationary |

| TMM |

-0.905921 |

2016Q1 |

unit root |

-3.071488 |

2016Q1 |

unit root |

-3.158296 |

2016Q1 |

unit root |

d(TMM) |

-5.948002 |

2007Q1 |

stationary |

-6.565202 |

2015Q4 |

stationary |

-6.772266 |

2015Q4 |

stationary |

| LOG(TCER) |

-2.083468 |

2011Q3 |

unit root |

-2.529216 |

2016Q1 |

unit root |

-4.164686 |

2015Q1 |

unit root |

d(LOG(TCER)) |

-9.412598 |

2015Q4 |

stationary |

-8.872301 |

2015Q2 |

stationary |

-9.244818 |

2014Q1 |

stationary |

| LOG(GEPUC) |

-4.760297 |

2003Q2 |

unit root at 1% and 5% |

-4.132822 |

2006Q1 |

unit root at 1% and 5% |

-4.728196 |

2003Q2 |

unit root |

d(LOG(GEPUC)) |

-8.667495 |

2003Q2 |

stationary |

-8.511604 |

2003Q4 |

stationary |

-8.616021 |

2003Q2 |

stationary |

| LOG(GEPUP) |

-4.642338 |

2003Q2 |

unit root at 1% and 5% |

-4.109994 |

2006Q1 |

unit root |

-4.607860 |

2003Q2 |

unit root |

d(LOG(GEPUP)) |

-8.477197 |

2003Q2 |

stationary |

-8.338515 |

2014Q2 |

stationary |

-8.456127 |

2012Q1 |

stationary |

| LOG(WUITUN1) |

-4.957170 |

2010Q3 |

unit root at 1% and 5% |

-3.263138 |

2013Q1 |

unit root |

-5.852233 |

2011Q1 |

stationary |

d(LOG(WUITUN1)) |

-7.895080 |

2013Q2 |

stationary |

-6.867825 |

2011Q2 |

stationary |

-8.337122 |

2013Q2 |

stationary |

| LOG(USMPUI) |

-6.708674 |

2003Q3 |

stationary |

-6.351941 |

2011Q2 |

stationary |

-6.825489 |

2003Q3 |

stationary |

d(LOG(USMPUI)) |

-6.893234 |

2003Q2 |

stationary |

-6.654978 |

2003Q4 |

stationary |

-6.839971 |

2009Q4 |

stationary |

| LOG(USFSI) |

-3.752368 |

2011Q4 |

unit root |

-3.174595 |

2009Q1 |

unit root |

-3.775881 |

2007Q3 |

unit root |

d(LOG(USFSI)) |

-9.660362 |

2009Q2 |

stationary |

-8.930478 |

2012Q4 |

stationary |

-9.742003 |

2009Q2 |

stationary |

| LOG(OILUI) |

-4.912595 |

2004Q2 |

unit root at 1% and 5% |

-5.729252 |

2005Q1 |

stationary |

-5.900665 |

2004Q2 |

stationary |

d(LOG(OILUI)) |

-9.409052 |

2000Q4 |

stationary |

-9.254111 |

2009Q3 |

stationary |

-9.409052 |

2000Q4 |

stationary |

3.4.1. Response of the Macroeconomic Variables to a Shock in Global Economic Uncertainty

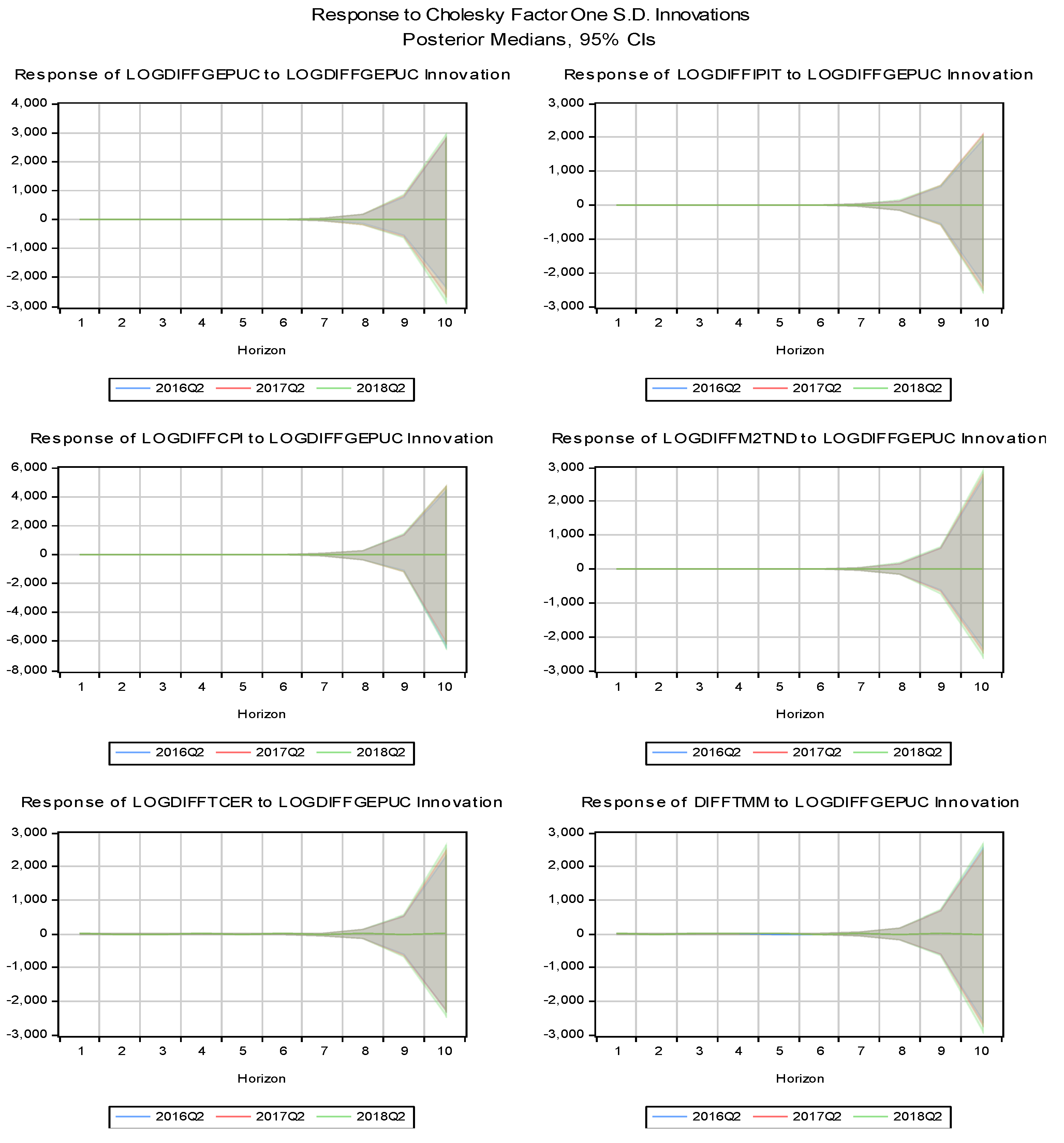

Figure 1 shows impulse response functions (IRFs) from a Bayesian TVC-VAR model. Specifically, these IRFs represent how the Tunisian macroeconomic variables respond to a one standard deviation shock in the global economic policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFGEPUC) over different time horizons (e.g., 4, 8, and 12 quarters) following Nakajima et al. (2011).

In the short term (0-4 quarters), the shock of global economic policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFGEPUC) leads to a decline in industrial production (LOGDIFFIPIT). The uncertainty could reduce external demand and investor confidence and lead to a decline in output. Medium-term (4-8 quarters): The effect remains negative but begins to stabilize, suggesting that industrial production is slowly adjusting to the uncertainty shock. In the longer term (8-12 quarters), the impact appears to fade as the economy recovers from the initial shock.

In the short term, the uncertainty shock (LOGDIFFGEPUC) initially causes prices to drop, possibly due to decreased demand or lower commodity prices. In the medium term, prices stabilize as the economy adjusts. There is little further impact on inflation in the long term, though the stabilization takes a while to become apparent.

In the short-term, a shock in global uncertainty (LOGDIFFGEPUC) leads to a temporary increase in money supply (LOGDIFFM2TND), as central banks may try to provide liquidity to counteract negative effects. In the medium term, the effect continues to rise as more liquidity is injected into the system. The effect stabilizes and eventually declines as monetary policy tightens or adjusts to the external uncertainty several quarters later.

Money market rates (DIFFTMM) rise in the short term as a result of the shock, reflecting either higher risk premiums or tighter credit conditions. Interest rates reach their peak and start to level off in the medium term. Rates become more neutral in the long run.

An uncertainty shock results in a short-term increase in the real exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER). This might be the result of decreased imports, which would strengthen the local currency, or capital inflows looking for safety. The real exchange rate stabilizes over the medium term. A few quarters after the initial capital inflows or adjustments normalize, there might be some reversion.

In summary, industrial production sharply declines in response to a shock in current global economic policy uncertainty, driven by immediate drops in external demand and increased investor uncertainty. This decline is most pronounced in the short term (0–4 quarters). Over the medium to long term (8–12 quarters), production begins to recover, though this recovery may be hindered by ineffective monetary policy tools like the money market rate. In response to uncertainty shocks, monetary authorities may temporarily increase the money supply to mitigate adverse effects. However, money market rates prove ineffective in stimulating industrial production. Higher risk premiums and tighter credit initially raise money market rates, but these do not significantly support production as financial markets adjust. This illustrates the limited impact of monetary policy during high uncertainty, particularly when businesses and consumers are risk-averse. Deflationary forces exert downward pressure on inflation in the short term, while prices stabilize over time. The real effective exchange rate rises sharply initially—likely due to reduced import demand and increased safe-haven capital inflows—before normalizing in the medium to long term. This highlights the challenges monetary policy faces in addressing uncertainty-driven disruptions.

The impact of LOGDIFFGEPUP leads to gradual and prolonged effects (

Figure 2). Industrial production (LOGDIFFIPIT) adjusts slowly, showing a delayed response to past uncertainties. The output contraction is prolonged, highlighting the lasting influence of previous uncertainty shocks. Inflation (LOGDIFFCPI) is experiencing a delayed decline amid rising deflationary pressures. The money supply expansion (LOGDIFFM2TND) in response to past uncertainties is more measured than for current uncertainties, reflecting a cautious monetary policy. The money market rate rises gradually, indicating that financial markets take longer to adjust to past uncertainties. This slow adjustment emphasizes the money market rate (potential) ineffectiveness in stimulating production during prolonged uncertainty, as businesses and consumers remain risk-averse and slow to respond to interest rate changes. The real effective exchange rate appreciates slowly as the economy adjusts to past uncertainties affecting trade and capital flows. Current uncertainty prompts swift responses, while past uncertainty leads to prolonged effects. This highlights differing transmission mechanisms, with the money market rate being less effective in mitigating the lasting impacts of past uncertainty on industrial production and economic dynamics.

3.4.2. Response of the Macroeconomic Variables to a Shock in World Uncertainty

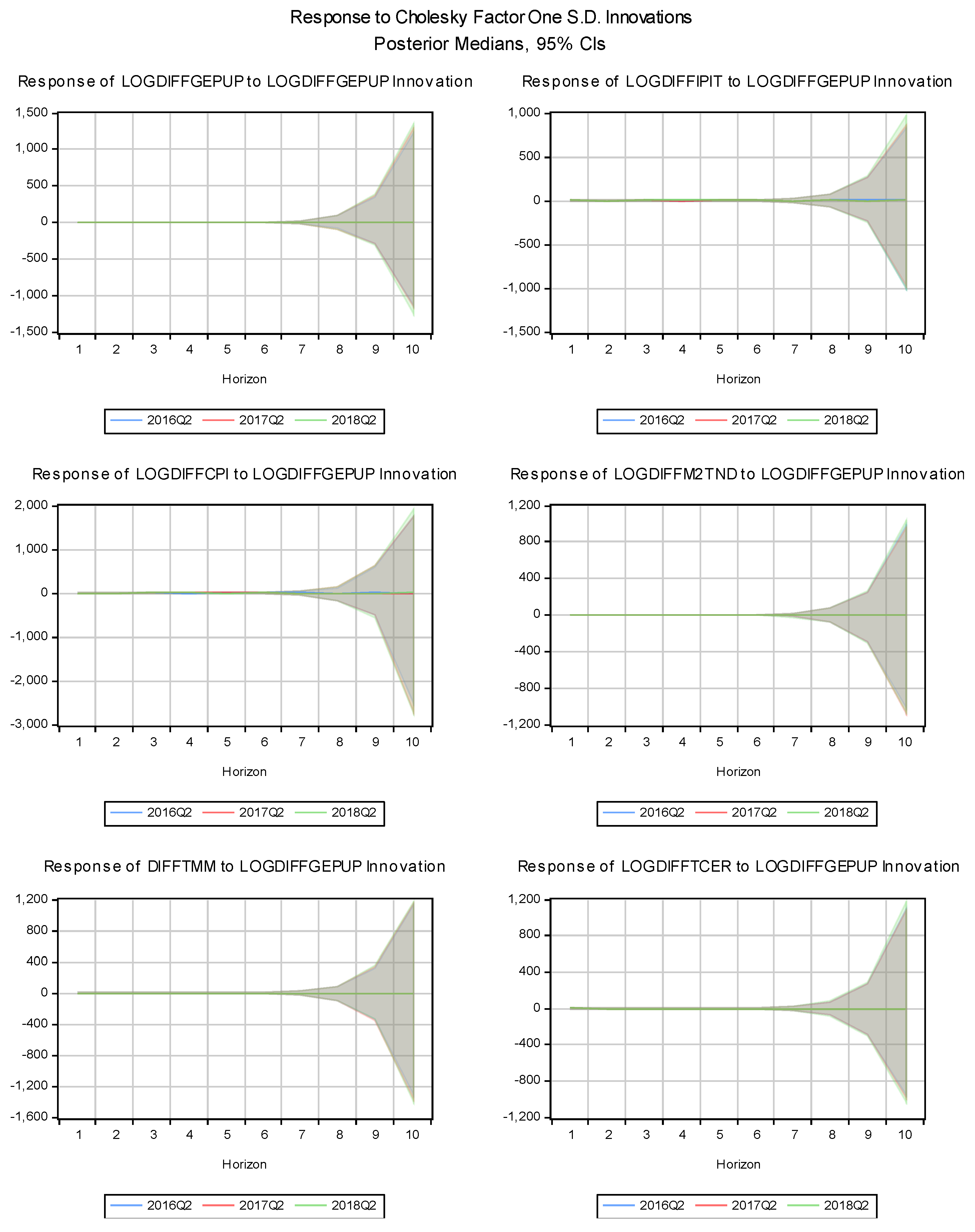

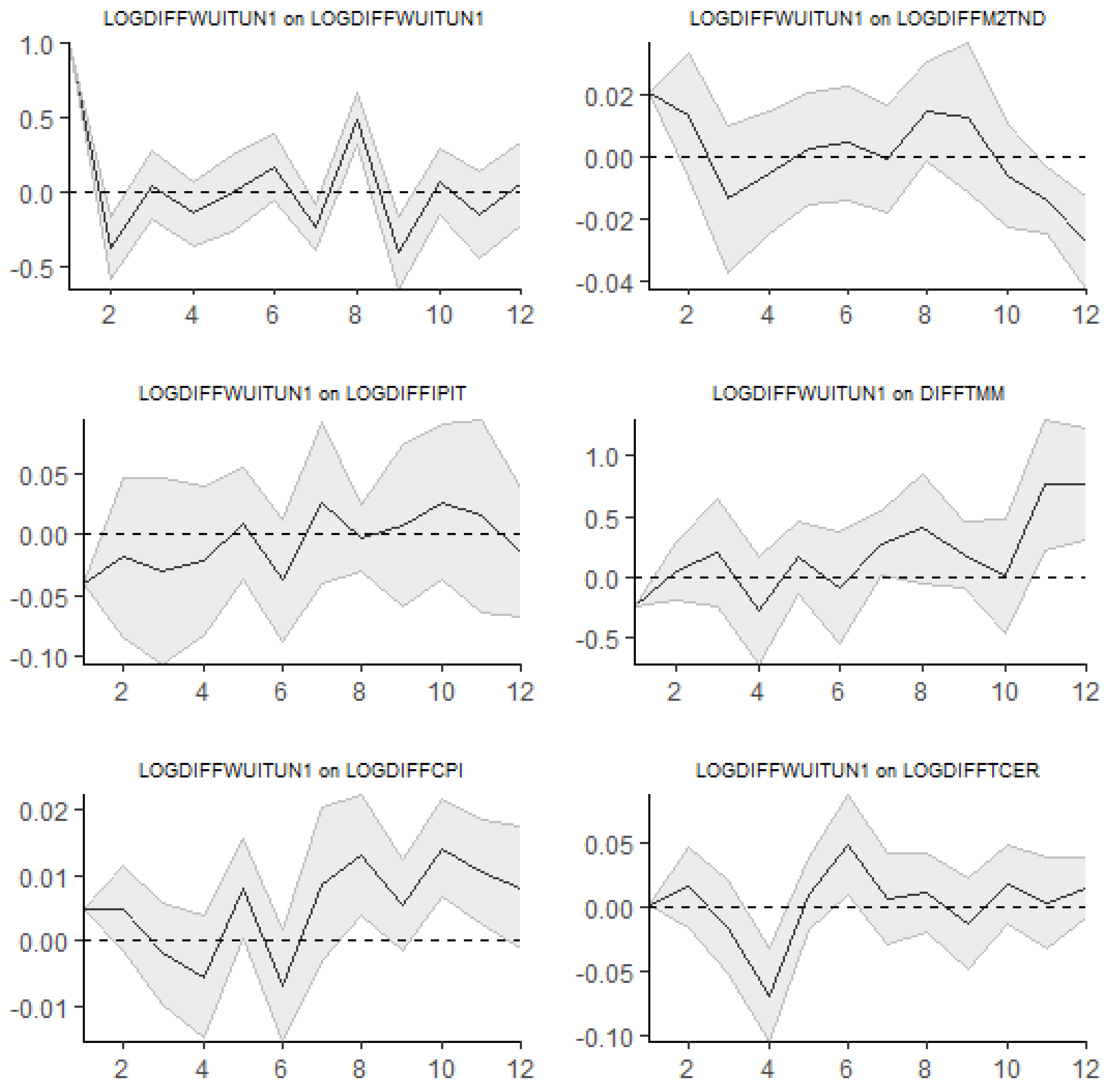

Figure 3 presents the IRFs from a Bayesian TVC-VAR model for Tunisia, where the same macroeconomic variables react to a shock in the World Uncertainty Index for Tunisia, denoted as LOGDIFFWUITUN1.

The industrial production index shows a delayed positive response to a shock in the Word uncertainty (LOGDIFFWUITUN1). Over different time horizons (4, 8, and 12 quarters), the reaction becomes more pronounced. At longer horizons (10 quarters), the confidence intervals widen, indicating more uncertainty about future outcomes.

The consumer price index (LOGDIFFCPI) exhibits an initially flat response but shows an increasingly positive response after 6 quarters. This suggests that higher world uncertainty (LOGDIFFWUITUN1) eventually leads to higher inflationary pressures in Tunisia. The expanding confidence bands highlight increasing uncertainty in price estimates over time.

The monetary aggregate (LOGDIFFM2TND) exhibits a slow initial response before gradually declining over eight to ten quarters. Possibly as a result of the central bank's attempts to lessen the effects of global uncertainty, this suggests a tightening of monetary conditions.

The money market rate (DIFFTMM) exhibits a slow initial response before progressively declining. Accordingly, there isn't likely to be a major change in monetary policy shortly, but as uncertainty (LOGDIFFWUITUN1) increases and economic activity slows, rates may eventually be reduced.

Over extended periods, the real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) responds negatively. This implies that increased uncertainty around the world causes the Tunisian dinar to depreciate. Around the 10-quarter horizon, the effect becomes more noticeable.

The IRFs show that the Tunisian economy is highly vulnerable to global uncertainty shocks from pandemics, crises, and wars. These shocks gradually and persistently affect long-term industrial production, inflation, monetary policy, and exchange rates, with initial effects being muted but intensifying over time. Industrial production often increases over time, possibly due to delayed global demand adjustments or government interventions. Inflation rises, likely from cost-push factors related to heightened uncertainty. Tightening money supply and exchange rate depreciation indicate potential central bank interventions to stabilize the economy during highly uncertain times.

The money market rate is a key monetary policy tool, with the central bank's interest rate adjustments crucial for economic management. However, muted initial responses and delayed effects suggest it may be less effective in stimulating production and stabilizing prices during significant uncertainty, as financial markets and economic agents need time to adjust.

The widening confidence intervals at longer time horizons highlight the growing unpredictability of economic outcomes, posing challenges for monetary policy in responding to prolonged global shocks.

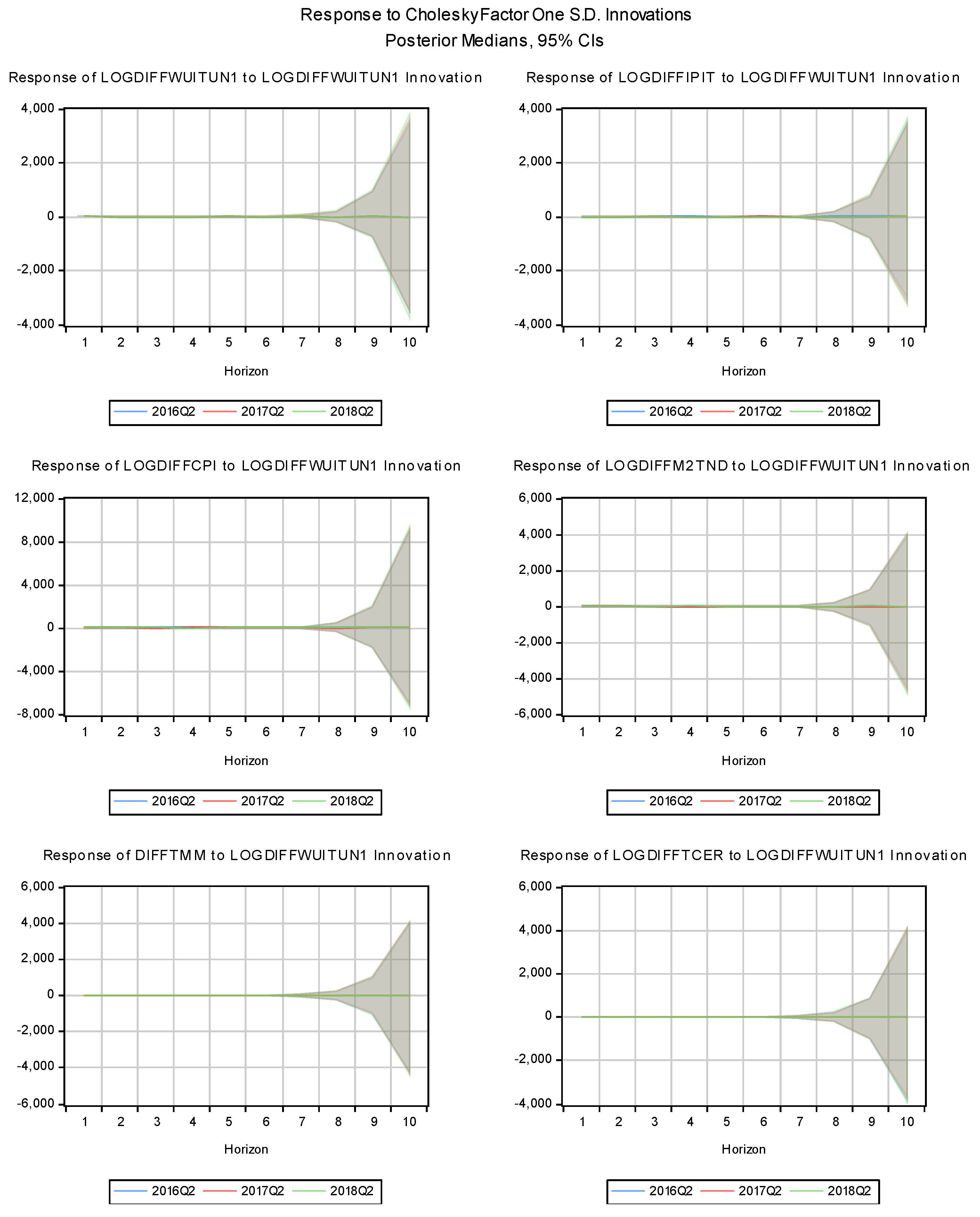

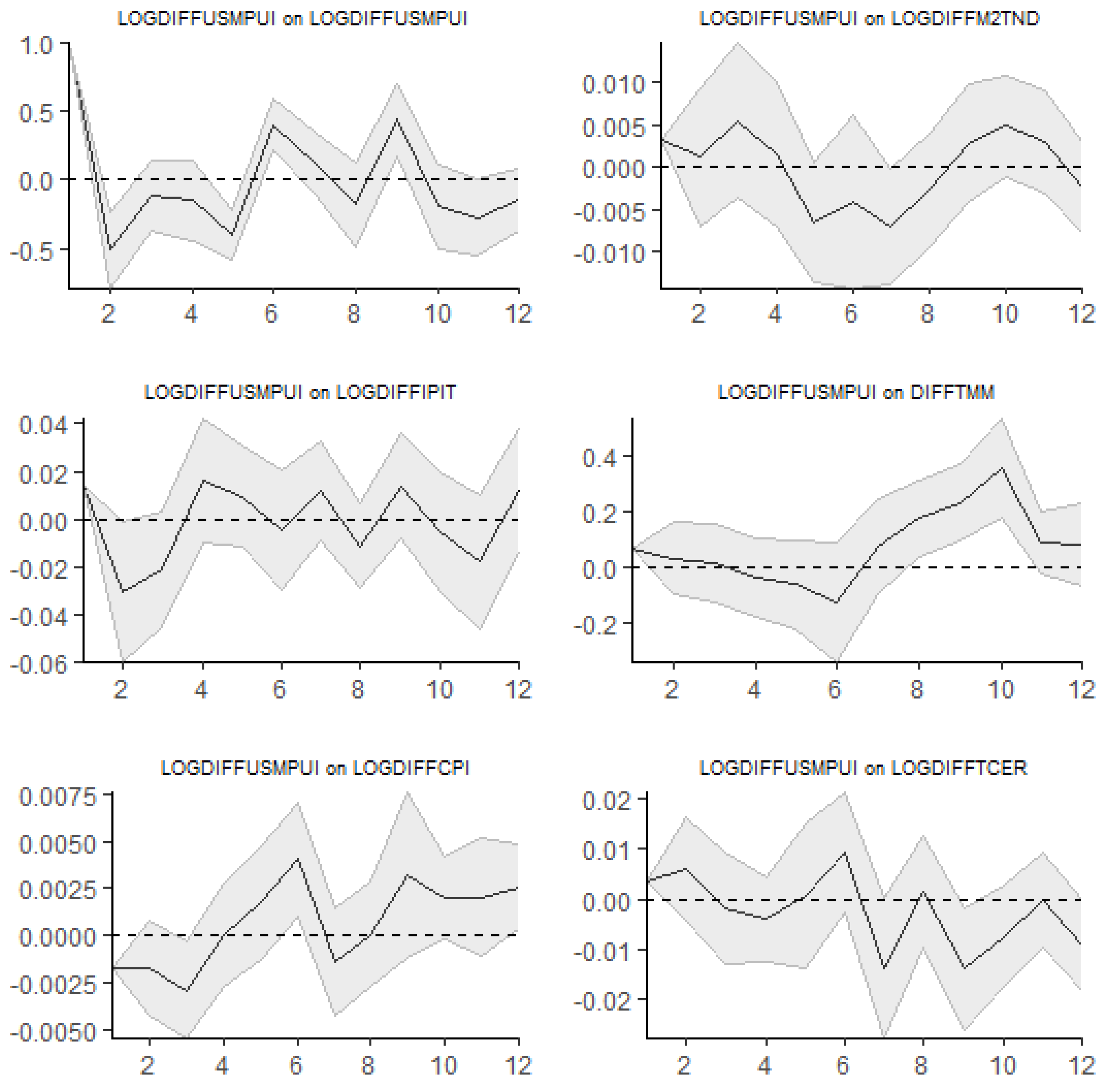

3.4.3. Response of Macroeconomic Variables to a Shock in US Monetary Policy Uncertainty

Figure 4 presents the IRFs from a Bayesian TVC-VAR model, showing how various Tunisian macroeconomic variables react to a shock in the US Monetary Policy Uncertainty Index (LOGDIFFUSMPUI). The responses are shown for several macroeconomic variables over different time horizons: 4, 8, and 12 quarters.

The industrial production index (LOGDIFFIPIT) in Tunisia shows an increasingly positive response to uncertainty in US monetary policy after about four to six quarters, suggesting that higher uncertainty in US monetary policy (LOGDIFFUSMPUI) could lead to an increase in industrial production in Tunisia in the medium term. This could be due to increased foreign investment or economic adjustments in response to changing external conditions.

The consumer price index (LOGDIFFCPI) shows a lagged but positive response to the shock, suggesting that US monetary policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI) may contribute to inflationary pressures in Tunisia over time. Confidence intervals are widening significantly, reflecting growing uncertainty about inflation outcomes over a longer period.

The monetary aggregate (LOFDIFFM2TND) reacts negatively after about 6-8 quarters, which may indicate that monetary conditions in Tunisia are tightening due to external monetary uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI). This tightening could be a response to easing inflationary pressures or stabilizing financial conditions.

The money market rate (DIFFTMM) is showing an upward movement after about six quarters, suggesting that Tunisia's interest rates are rising in response to U.S. monetary policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI). This could be due to central bank efforts to stabilize capital flows or prevent capital flight.

The real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) shows a negative reaction over the 8-10 quarter time horizon, suggesting that the Tunisian currency is depreciating in response to US monetary policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI). This could be due to capital outflows or declining confidence in the Tunisian economy as global conditions become more uncertain.

In summary, US monetary policy uncertainty significantly impacts Tunisia's economy with a delay. In the short to medium term, industrial production benefits from adjustments in global demand, while long-term effects include inflationary pressures and exchange rate depreciation due to persistent uncertainty. Tunisia's monetary policy, through money supply and interest rate adjustments, counters inflation and maintains financial stability. The money market rate is crucial for managing inflationary pressures, but its effectiveness is delayed by the slow response of financial markets to US monetary policy uncertainty.

US monetary uncertainty has mixed effects on Tunisia’s economy, providing short-term benefits to output while negatively impacting inflation and the exchange rate in the long term. Widening confidence intervals suggest increasing uncertainty about future economic outcomes, complicating Tunisia’s response to uncertainty.

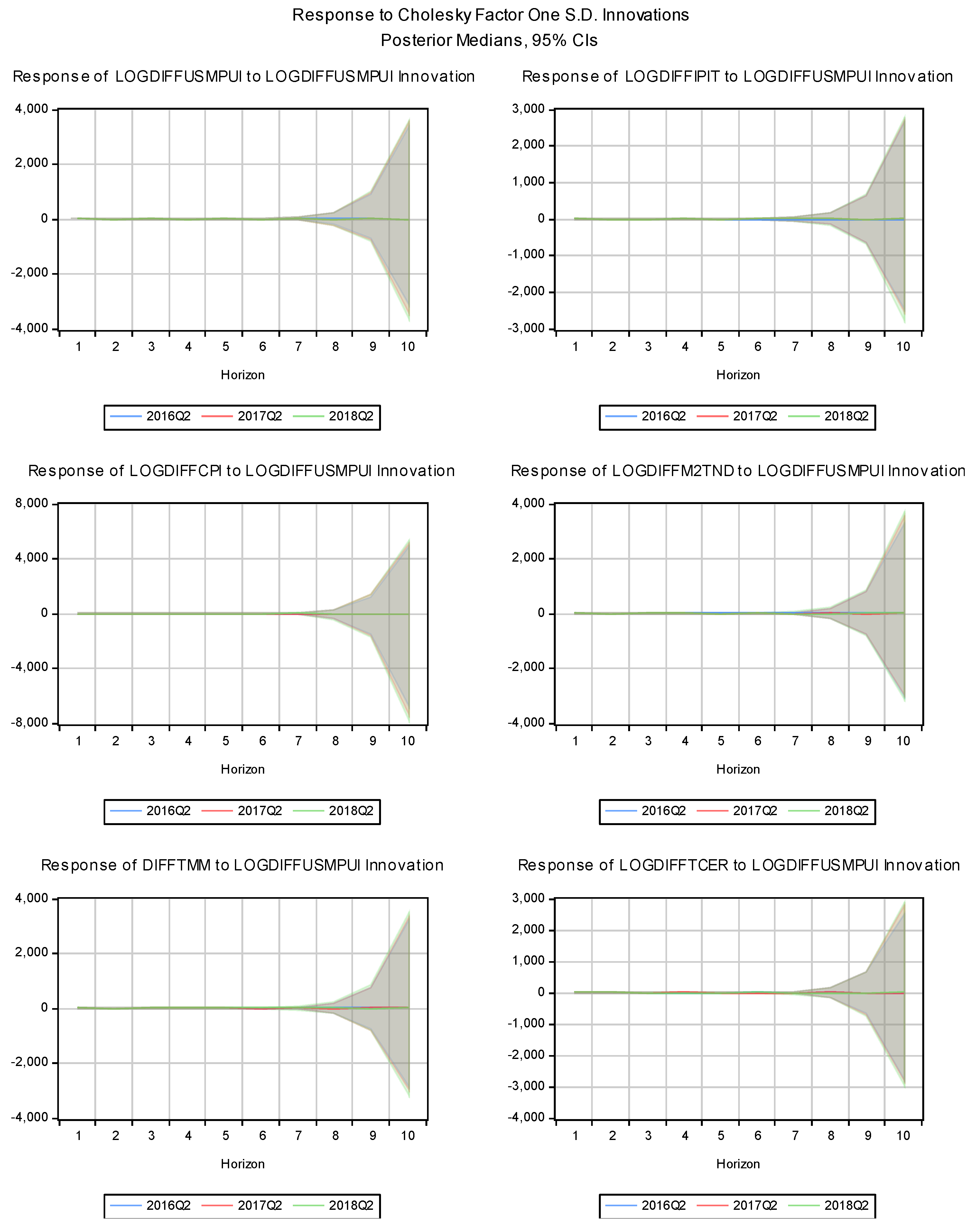

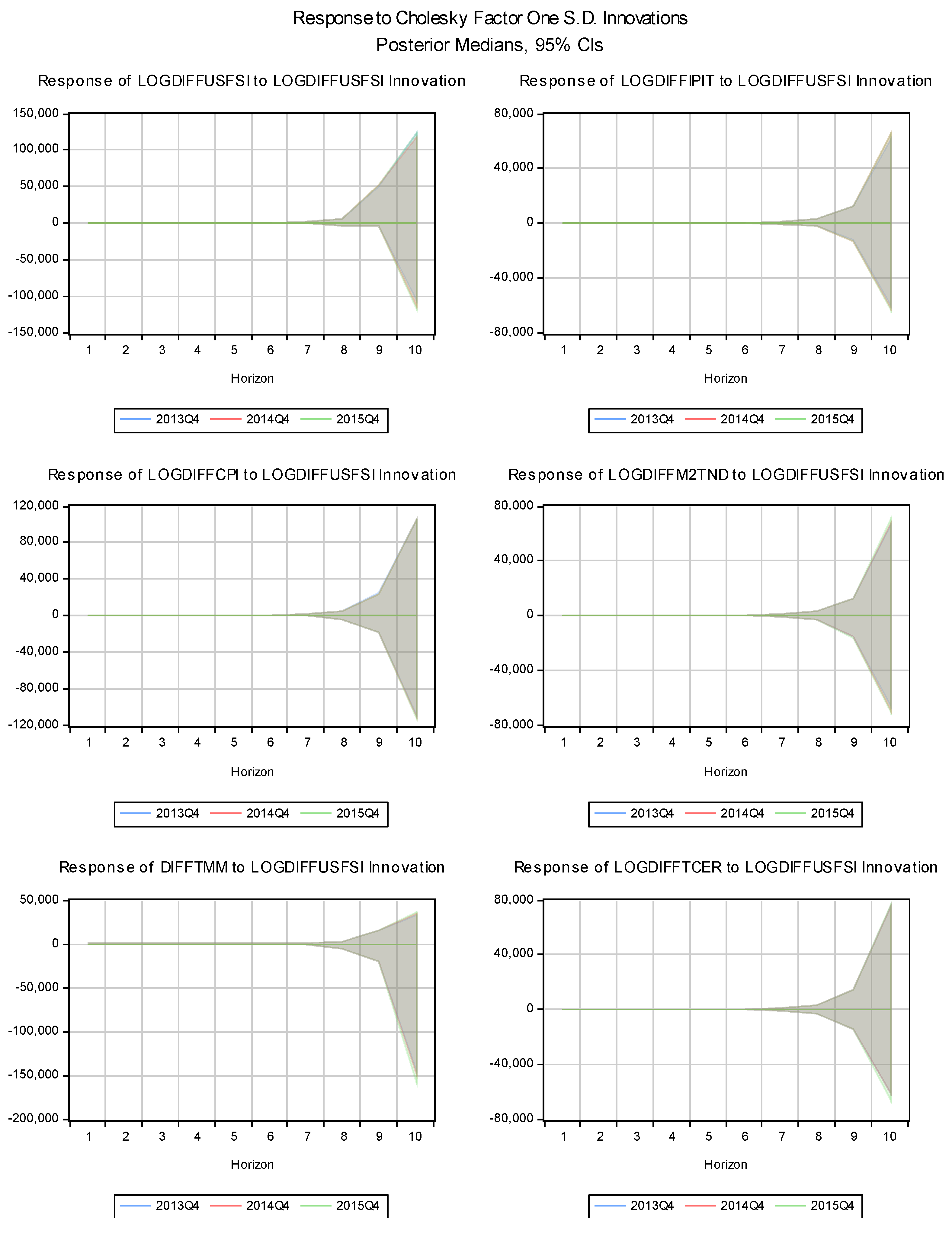

3.4.4. Response of Macroeconomic Variables to a Shock in US Financial Stress

Figure 5 displays the IRFs from a Bayesian TVC-VAR model, illustrating how Tunisia’s key macroeconomic variables react to a shock in the US Financial Stress Index (LOGDIFFUSFSI). The responses are tracked over different time horizons (4, 8, and 12 quarters), providing insights into Tunisia’s vulnerability to US financial stress.

Industrial production (LOGDIFFIPIT) reacts with a delay but increasingly to the shock, with a noticeable increase after 6 to 8 quarters. This suggests that the growing financial crisis in the US could have a positive impact on Tunisia's industrial production in the medium term, possibly driven by shifts in global capital flows or changes in external demand.

The consumer price index (LOGDIFFCPI) reacts positively, although with a slight delay. After about eight quarters, inflation begins to rise, suggesting that financial stress in the US (LOGDIFFUSFSI) is leading to inflationary pressures in Tunisia. This could be due to imported inflation or higher borrowing costs as global financial conditions tighten.

The monetary aggregate (LOGDIFFM2TND) shows an increasing response after six quarters, reflecting an increase in liquidity in the financial system. This could be due to domestic monetary policy adjustments to counteract the impact of external financial stresses by increasing liquidity to support economic activity.

The money market rate (DIFFTMM) remains relatively stable in the short term but shows an upward reaction over time. This suggests that interest rates in Tunisia are rising following the financial stress in the US (LOGDIFFUSFSI), likely due to a tightening of domestic monetary policy to prevent capital outflows or inflationary spirals.

The real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) experiences a long-term depreciation, which increases after 8 quarters. This suggests that financial stress in the US (LOGDIFFUSFSI) is weakening Tunisia's currency, possibly due to lower investor confidence or capital flight from emerging markets such as Tunisia.

A shock to the US financial stress index significantly and gradually affects the Tunisian economy. Initially, industrial production benefits due to global demand adjustments and delayed responses from the government or businesses. However, this stability is accompanied by rising inflation and increased liquidity as the central bank adjusts the money supply in response to external pressures.

While the initial economic boost may seem beneficial, the effectiveness of Tunisia's monetary policy tools, especially the money market rate, is evident. The central bank's adjustments to money supply and interest rates aim to stabilize the economy, but the money market rate struggles during external financial stress. Its delayed adjustment reflects its limited ability to respond quickly to US financial tensions, which led to higher domestic interest rates and a depreciation of the real effective exchange rate.

These responses highlight the interconnectedness of global financial markets and Tunisia’s vulnerability to external shocks. The money market rate, as a monetary policy tool, is less effective in mitigating external stress, particularly when financial markets are slow to adjust. The depreciation of the exchange rate and rising interest rates show how Tunisia’s monetary policy can be overwhelmed by external shocks, resulting in a misalignment between domestic measures and external economic realities.

Tunisia’s central bank can manage some immediate effects through liquidity adjustments; however, the broader economic impact of U.S. financial stress reveals the limitations of the money market rate in stabilizing the economy during high external volatility. This suggests that Tunisia may need to supplement traditional monetary policy with fiscal interventions or enhanced financial market actions to address prolonged external uncertainty.

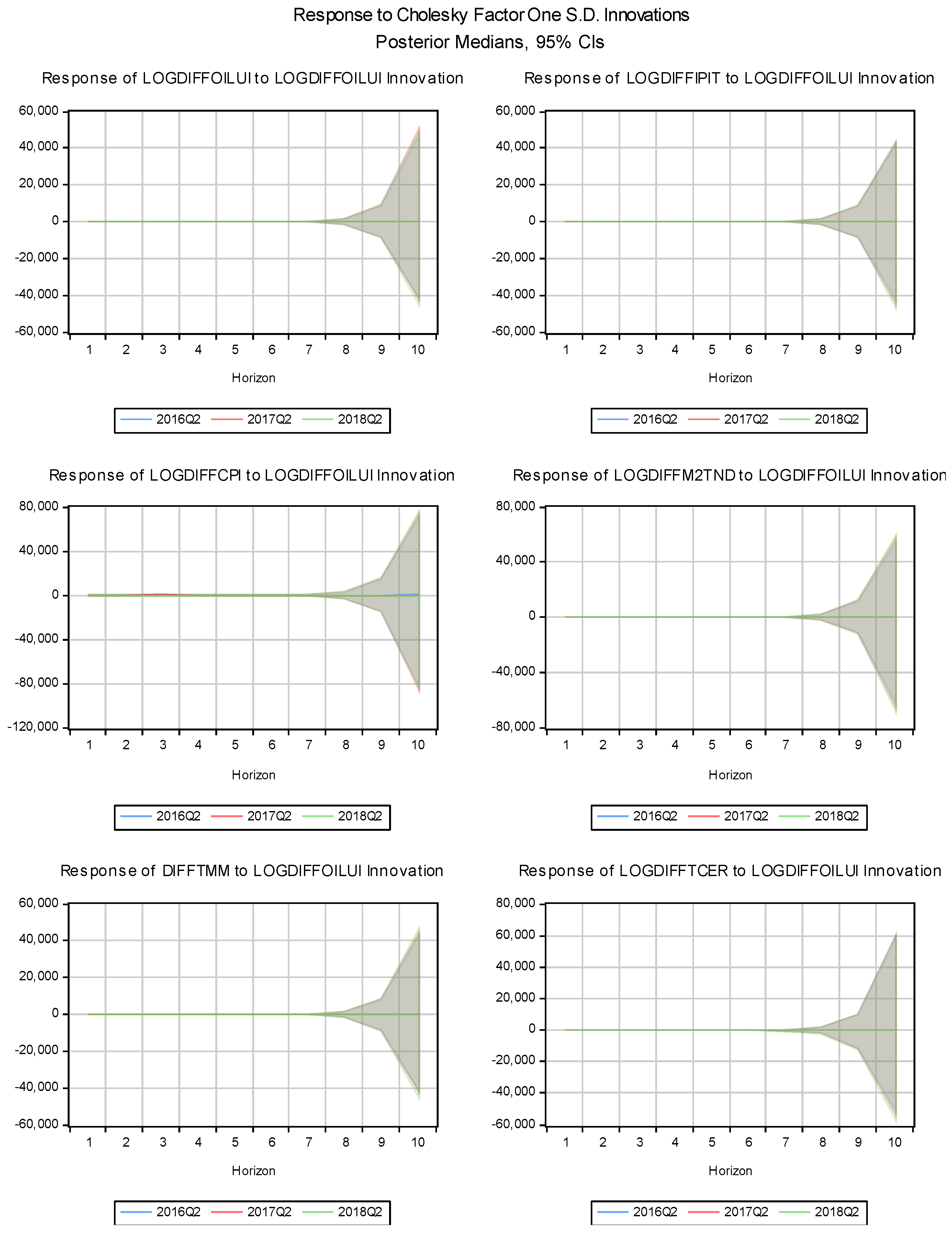

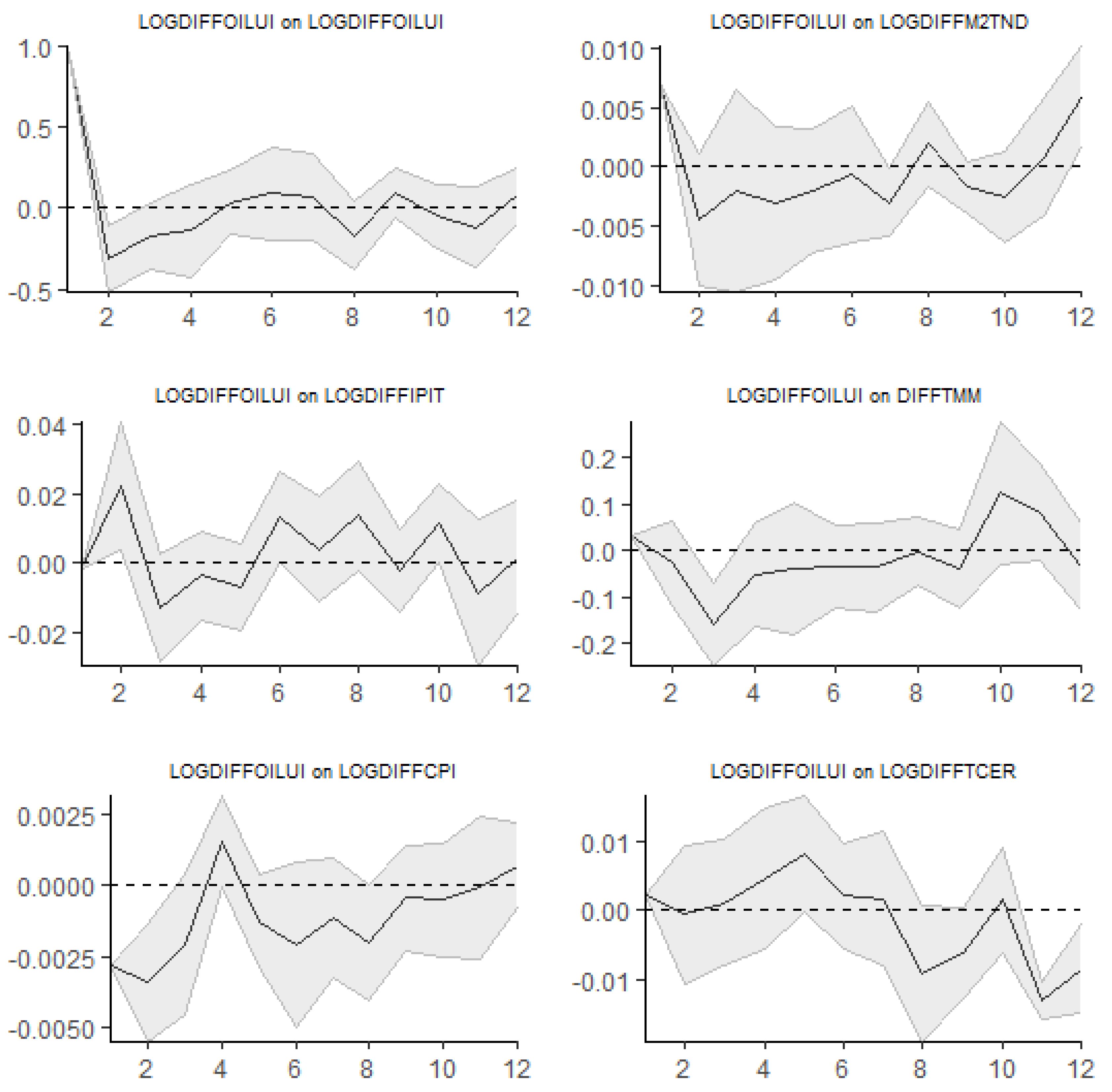

3.4.5. Response of Macroeconomic Variables to Oil Price Uncertainty

Figure 6 shows the impulse responses from a Bayesian TVC-VAR model, illustrating how different economic variables in Tunisia respond to a shock in the Oil price Uncertainty Index (LOGDIFFOILUI) over time. Each graph tracks these responses at different horizons (4, 8, and 12 quarters ahead).

The reaction of industrial production (LOGDIFFIPIT) is initially close to zero but becomes negative over time. This suggests that oil price uncertainty (LOGDIFFOILUI) is harming industrial production in Tunisia, with increasing impacts over the forecast period.

The consumer price (LOGDIFFCPI) also shows a lagged positive response to oil price uncertainty. This means that uncertainty about oil prices creates inflationary pressures, driving up consumer prices over time.

The money supply response (LOGDIFFM2TND) is initially slightly positive and increases over time, suggesting that monetary authorities may respond to oil price uncertainty by expanding the money supply.

The money market interest rate (DIFFTMM) shows a lagged negative response, suggesting that uncertainty in oil prices (LOGDIFFOILUI) may lead to lower interest rates as a monetary policy measure to support economic activity.

The exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) initially shows a minimal reaction. It eventually increases, suggesting that uncertainty about the oil price (LOGDIFFOILUI) could lead to a real increase in the value of the Tunisian currency over time.

To sum up, increased oil price uncertainty leads to a sustained decline in industrial production, highlighting its negative impact on economic activity. This downturn dampens business confidence, reduces investment, and disrupts production processes. The decline underscores the importance of energy costs in shaping industry competitiveness and operational efficiency, especially in Tunisia's economy, which is vulnerable to external shocks.

This uncertainty coincides with rising consumer prices, indicating inflationary pressures likely driven by higher energy import costs. The increase reflects the direct impact of expensive oil and heightened inflation expectations. As oil price volatility escalates, businesses and consumers may adjust their pricing behaviors, further exacerbating inflation. This illustrates how oil price uncertainty affects immediate production costs and alters broader economic expectations.

Monetary authorities are expanding the money supply to inject liquidity and mitigate the adverse effects of the oil price shock. This aims to counteract the contraction in industrial output and alleviate inflationary pressures from rising energy prices. However, the effectiveness of this policy is limited by the money market rate's ability to manage external shocks.

The decline in the money market rate indicates that the central bank is cutting interest rates to stimulate economic growth and investment. However, during periods of high uncertainty, financial markets may respond slowly to these changes. Investors may be cautious, and businesses may delay production expansion despite lower borrowing costs. Thus, the money market rate's ability to drive a timely recovery in industrial production may be limited, especially if oil price uncertainty persists.

The real effective exchange rate rises after the oil price shock, likely due to capital inflows into Tunisian assets or currency adjustments from global oil market volatility. This domestic currency depreciation may reflect a broader rebalancing of financial flows in response to oil price changes and global economic conditions.

Oil price uncertainty is dampening industrial production in Tunisia and fueling inflation. The slow adjustment of financial markets to policy changes reveals the money market rate's potential ineffectiveness in addressing oil price uncertainty.

3.5. Results of LPs

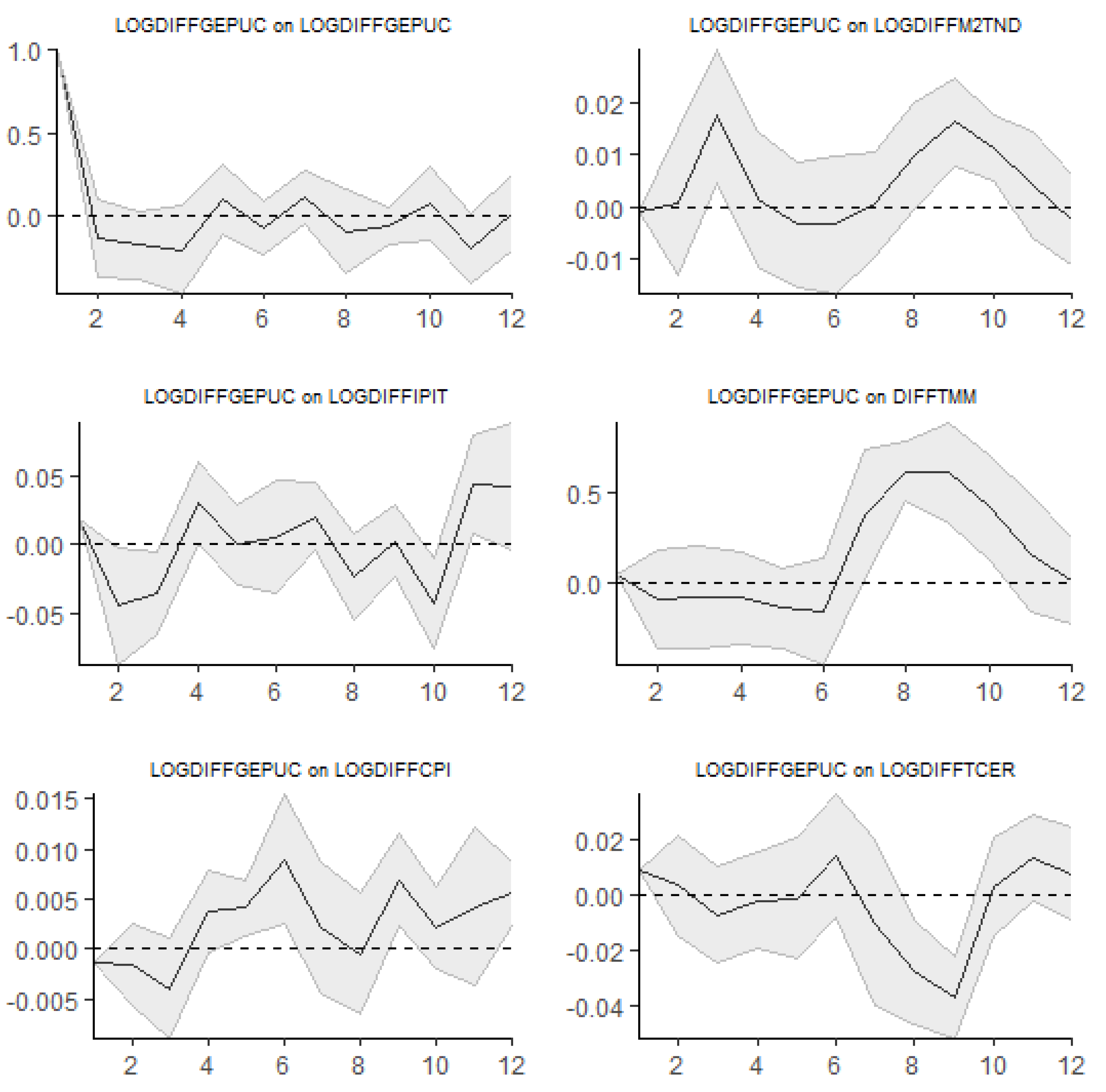

3.5.1. Impact of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Shocks on Macroeconomic Variables

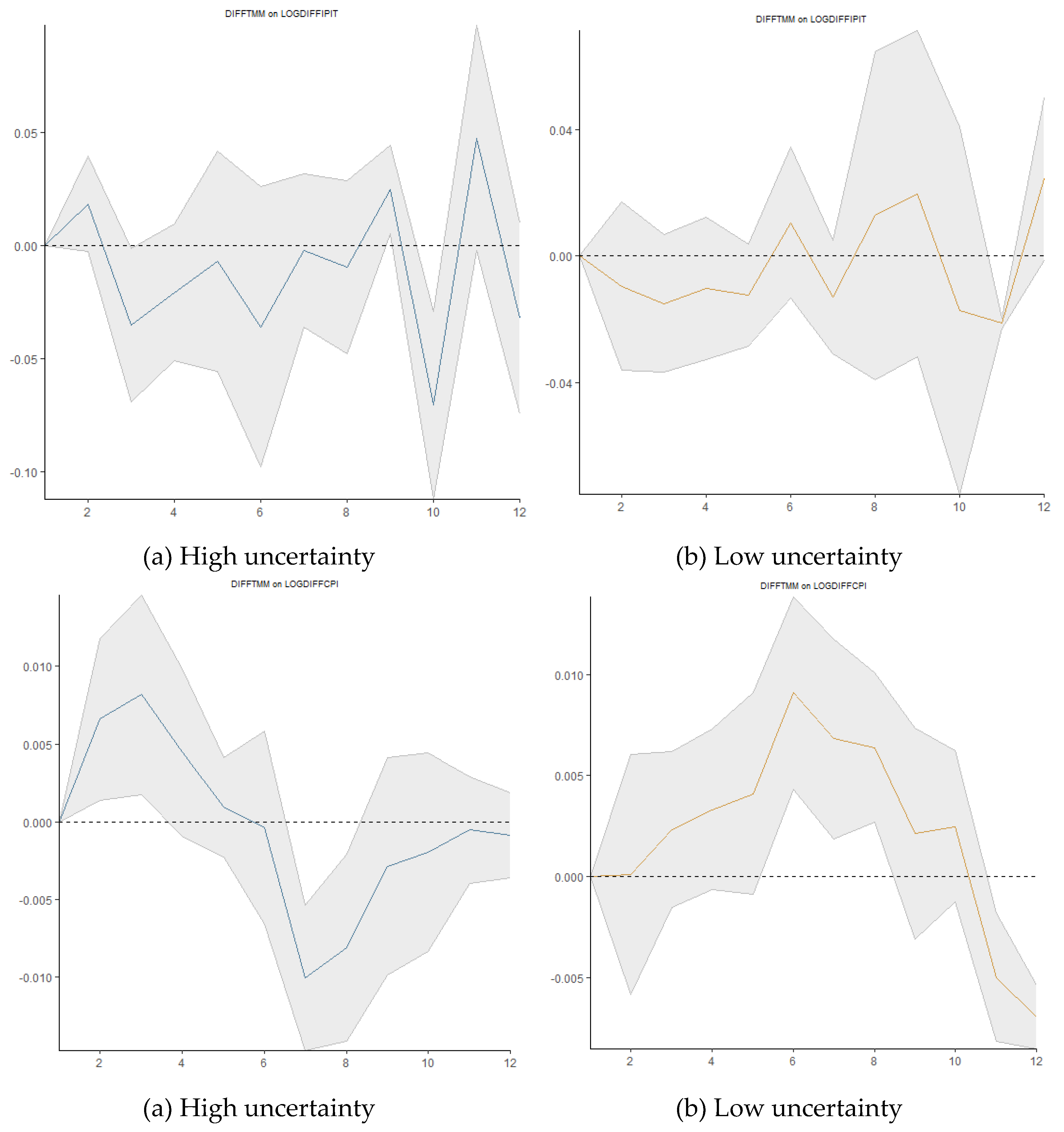

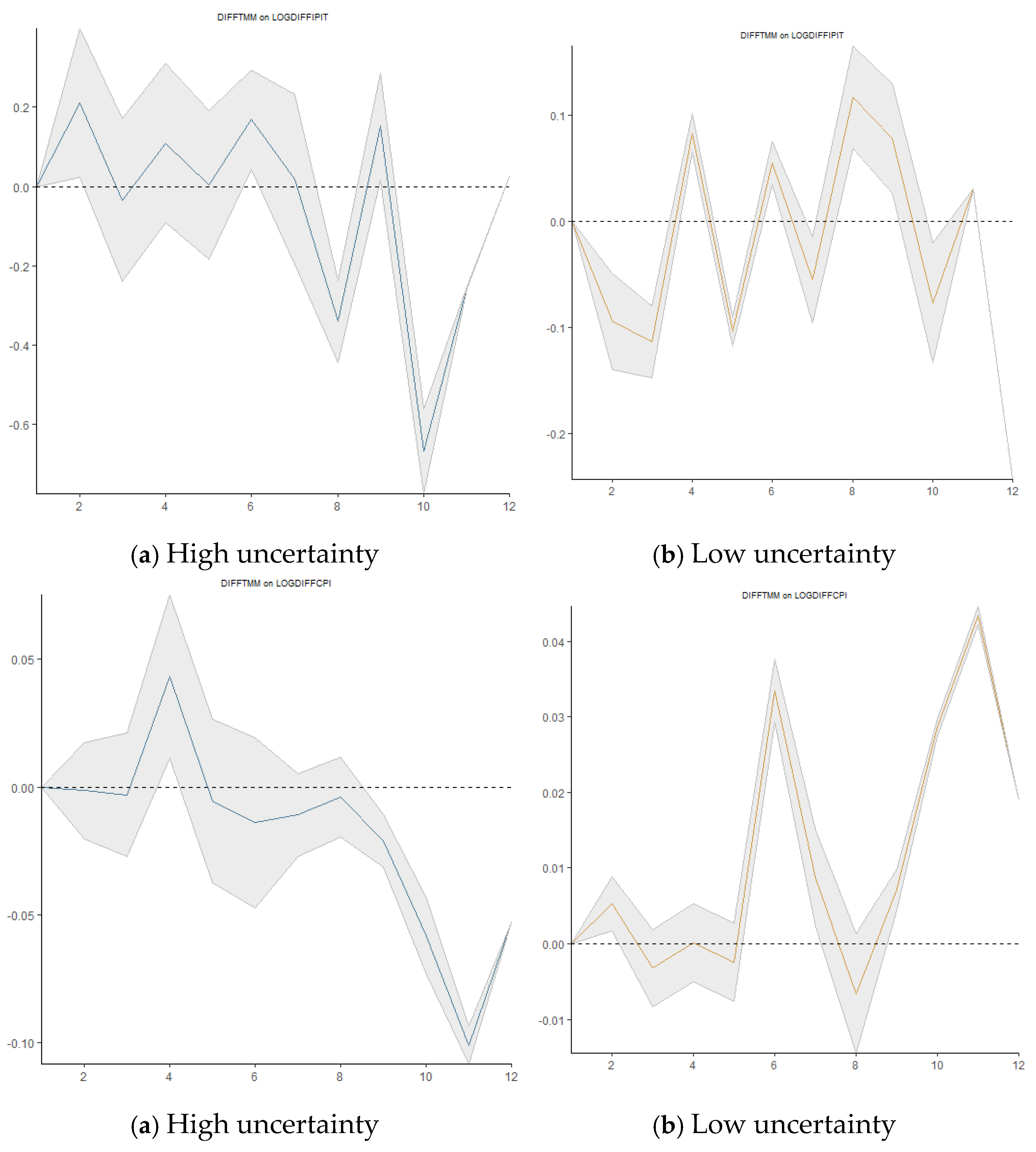

Figure 7 shows the impulse responses based on local linear projections, all identified with a standard Cholesky decomposition and the causal order (industrial production, consumer price index, money supply, money market rate, real exchange rate, and the global economic uncertainty variable). According to Trabelsi and Ben Khaled (2023). We use AIC to select the optimal delay (p) with a maximum set to 8. The solid line and the two thick lines show the responses from LPs and the corresponding Newey-West corrected two standard error bands. The LP response of industrial production (LOGDIFFIPIT) and inflation (LOGDIFFCPI) suggests a 0.025% increase to a shock in the GEPUC 12 quarters after the impact. The money supply's response to the increase in LOGDIFFGEPUC exhibits both positive and negative effects, remaining statistically insignificant over 12 quarters. The LPs show a negative initial money market reaction (DIFFTMM) with a dramatic increase around the seventh quarter. The response of the real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) to the global economic uncertainty shock is unstable but tends to decline 12 quarters later.

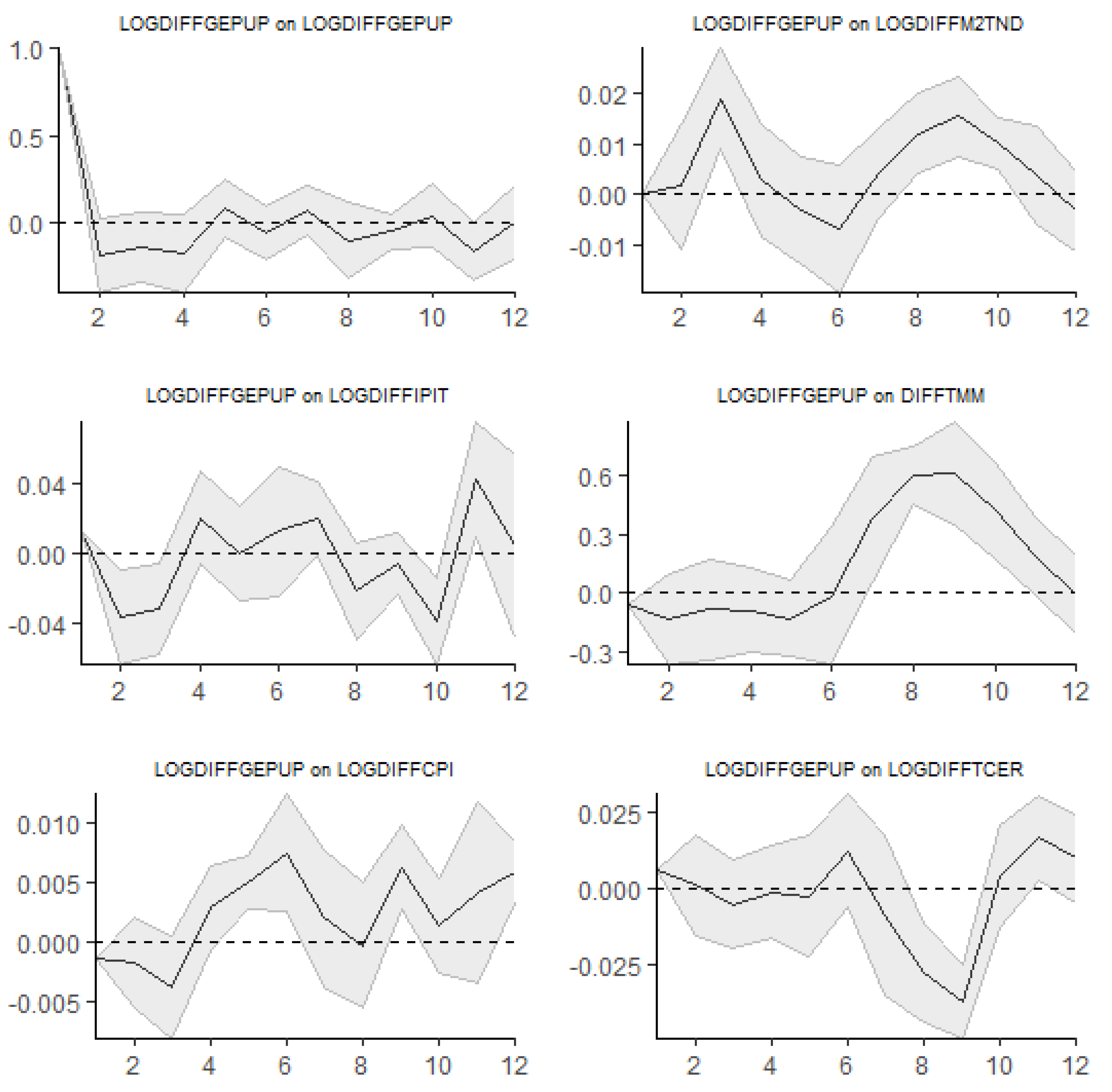

If we replace the uncertainty variable with LOGDIFFGEPUP, the results in

Figure 8 are almost identical to the previous ones. Global economic uncertainty can disrupt monetary policy transmission, affecting output and inflation, particularly when economic agents ignore central bank announcements.

3.5.2. Impact of the World Uncertainty Shocks on Macroeconomic Variables

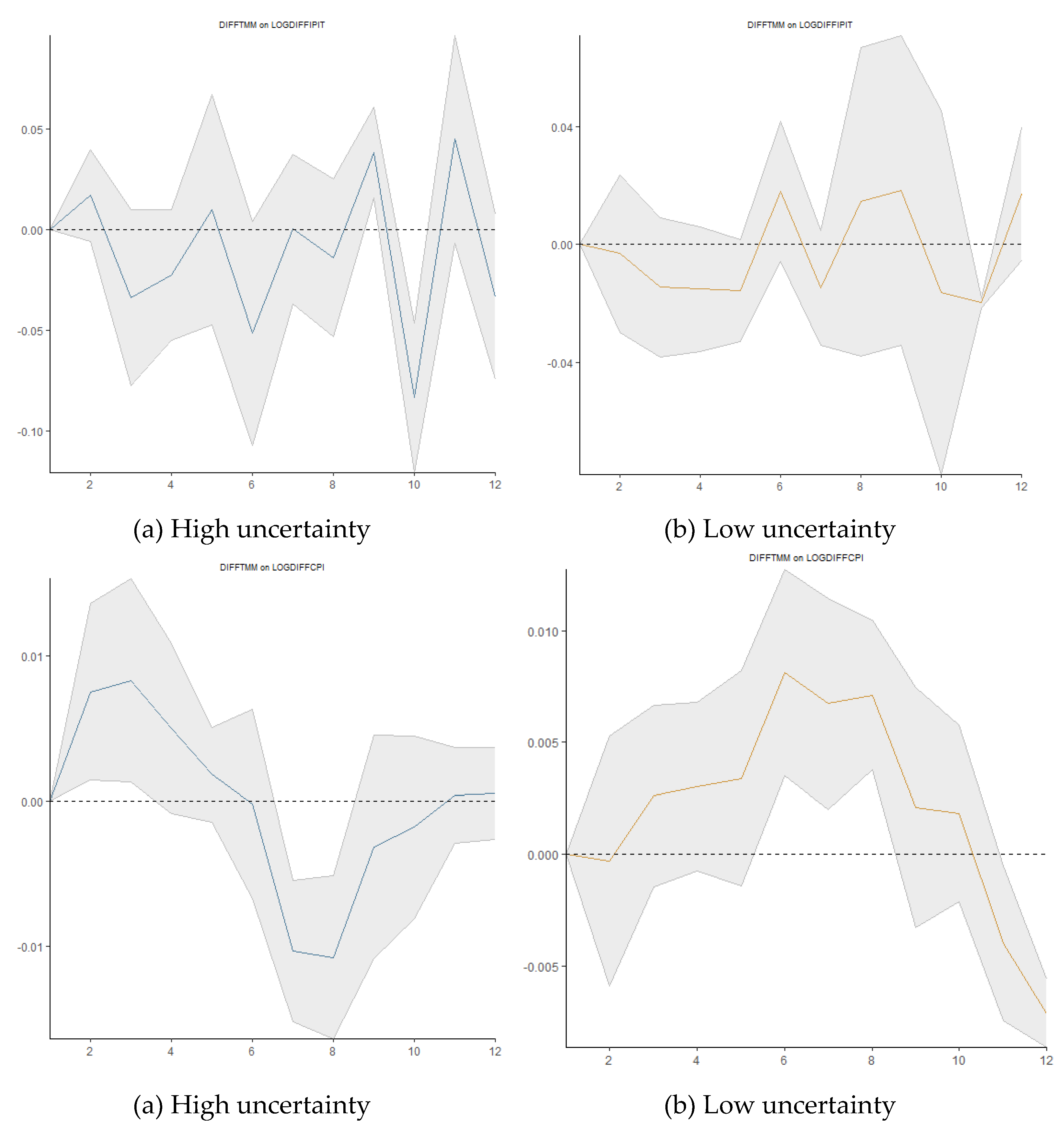

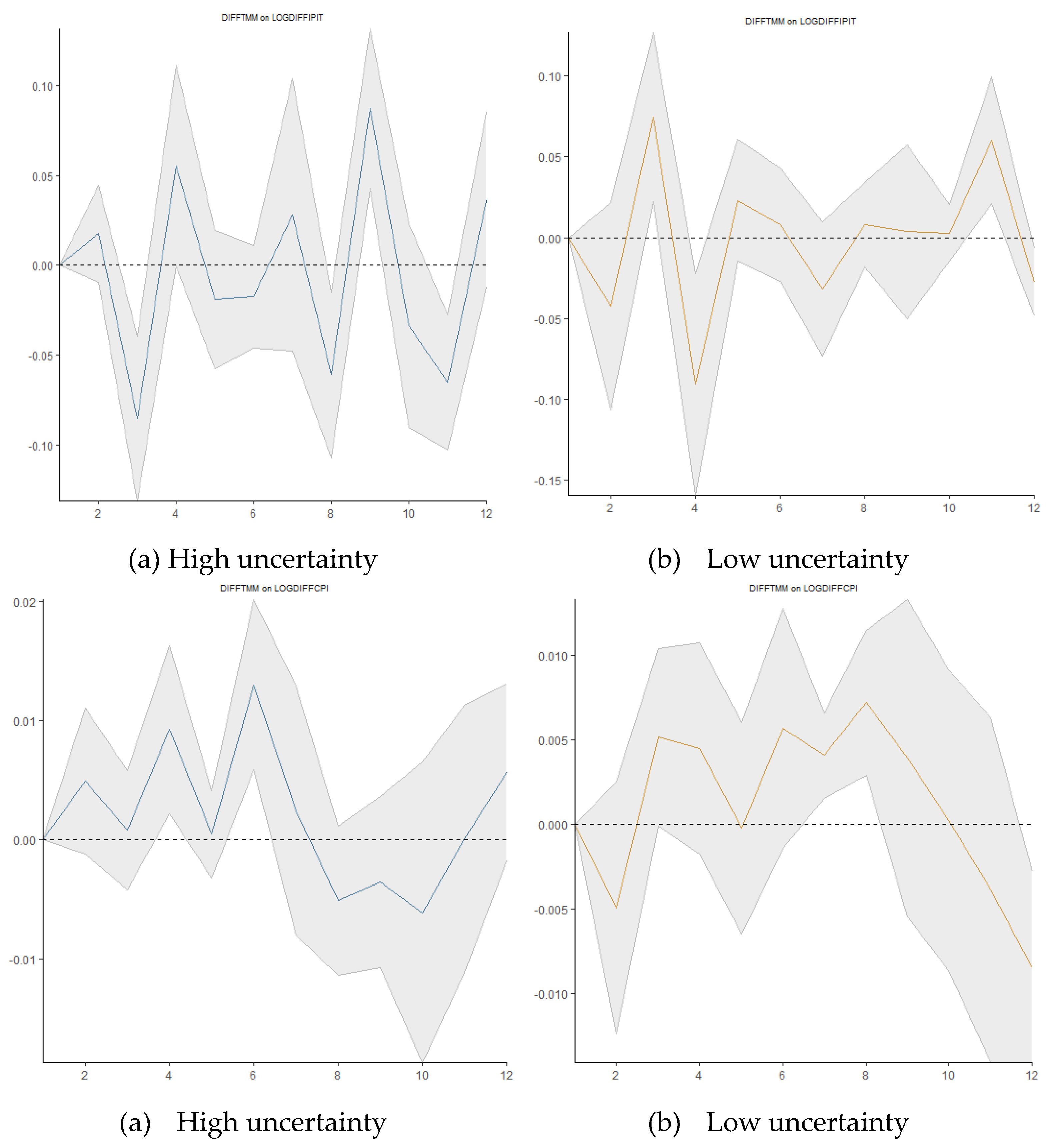

The money market rate and the real effective exchange rate have a positive correlation with an increase in the World Uncertainty Index shock starting in the seventh quarter. The money supply, inflation, and industrial production usually decrease twelve quarters later (

Figure 9). An industrial production contraction (LOGDIFFIPT) is usually the result of a shock to global uncertainty because of delayed investments, weakened global demand, and disrupted supply chains. Inflation (LOGDIFFCPI) also decreases as a result of less demand pushing down prices. The real exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) may also decline as a result of these shocks, increasing Tunisia's export competitiveness while also driving up import prices. The central bank of Tunisia frequently responds by increasing the money supply (LOGDIFFM2TND) to supply liquidity and lowering the money market rate (DIFFTMM) to encourage borrowing and boost the country's economy. Global uncertainty generally has a stabilizing effect on inflation but a destabilizing effect on output. Pandemic, war, and crisis-related uncertainty make investors fearful and increase their vigilance until they have more accurate information to react to changes in policy. This aligns with the opinions of Trabelsi and Serghini (2024), who compared the actions of the private sector before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.5.3. Impact of US Monetary Policy Uncertainty Shocks on Macroeconomic Variables

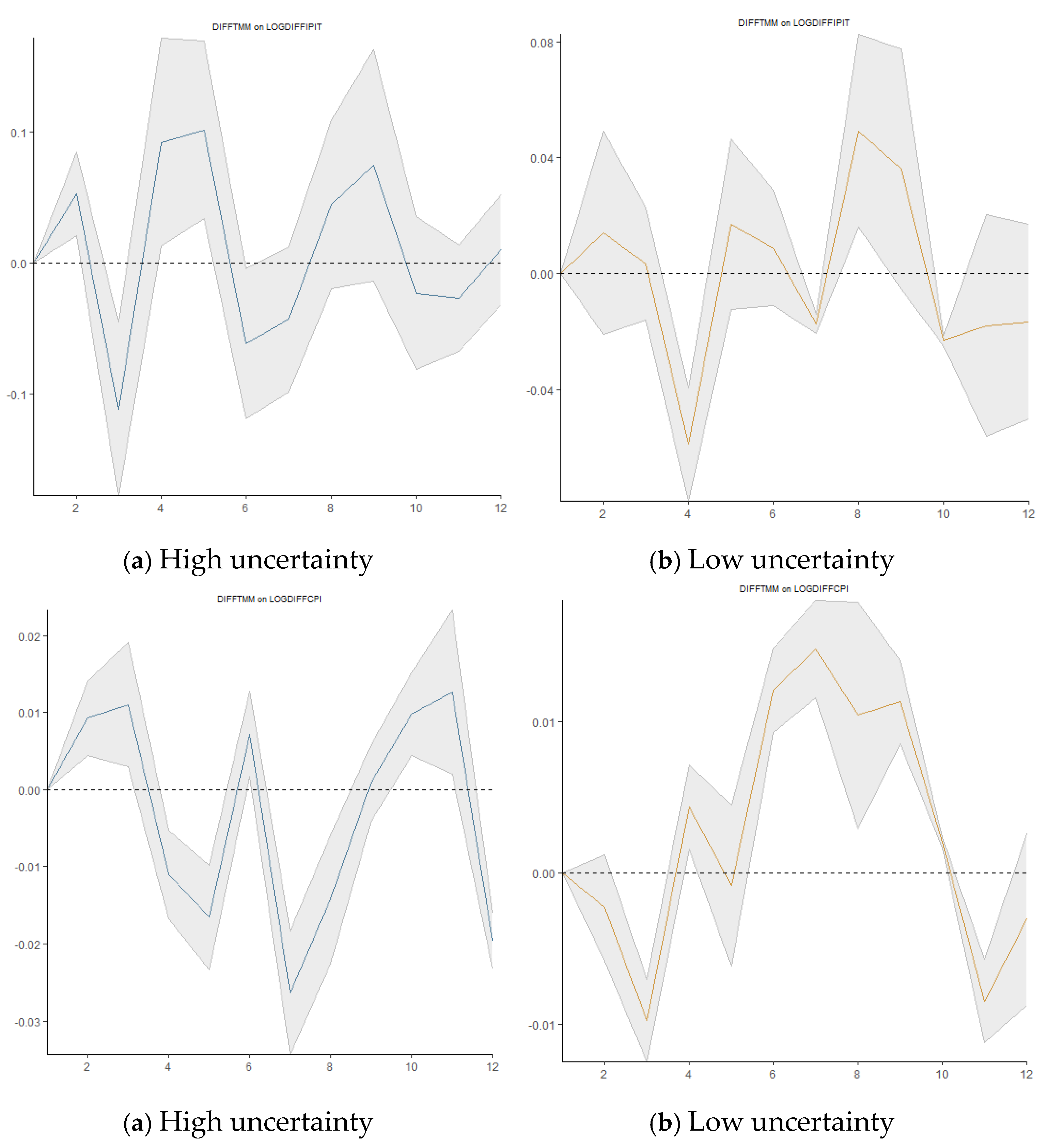

The impact of the same shock on the real effective exchange rate pertains to be negative over a long horizon. We are interested in how the same basket of variables reacts to a shock in the US monetary policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI), with a focus on spillover uncertainty shocks. The most noticeable effect is seen in the money market rate (DIFFTMM) and inflation (LOGDIFFCPI) responses, which after seven quarters show an upward trend albeit one that is unstable (

Figure 10). Twelve quarters after a shock to the US monetary policy, the money supply and industrial production respond less uncertainly. Over an extended period, the same shock is likely to hurt the real effective exchange rate.

3.5.4. Impact of US Financial Stress Shocks on Macroeconomic Variables

An increase in the US financial stress index causes a rise in the consumer price index (LOGDIFFCPI) from the eighth quarter and in the money supply seven quarters afterward before decreasing again in the remaining quarters. We observe a dramatic decline in the money market rate (DIFFTMM) due to the shock while the response of the real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) is downward but remains positive in the last quarters. There is an appreciation of the local money compared to the US dollars of about 1% (see

Figure 11).

The production and financial markets of Tunisia are particularly strained by the tighter global credit conditions brought on by US monetary policy uncertainty (LOGDIFFUSMPUI) and financial stress (LOGDIFFUSFSI). Interest rate reductions and monetary expansion that eventually become contraction are the CBT's responses to negative external effects. It takes time for economic agents to assimilate effective and transparent information regarding monetary policy positions.

3.5.5. Impact of Oil Price Uncertainty Shocks on Macroeconomic Variables

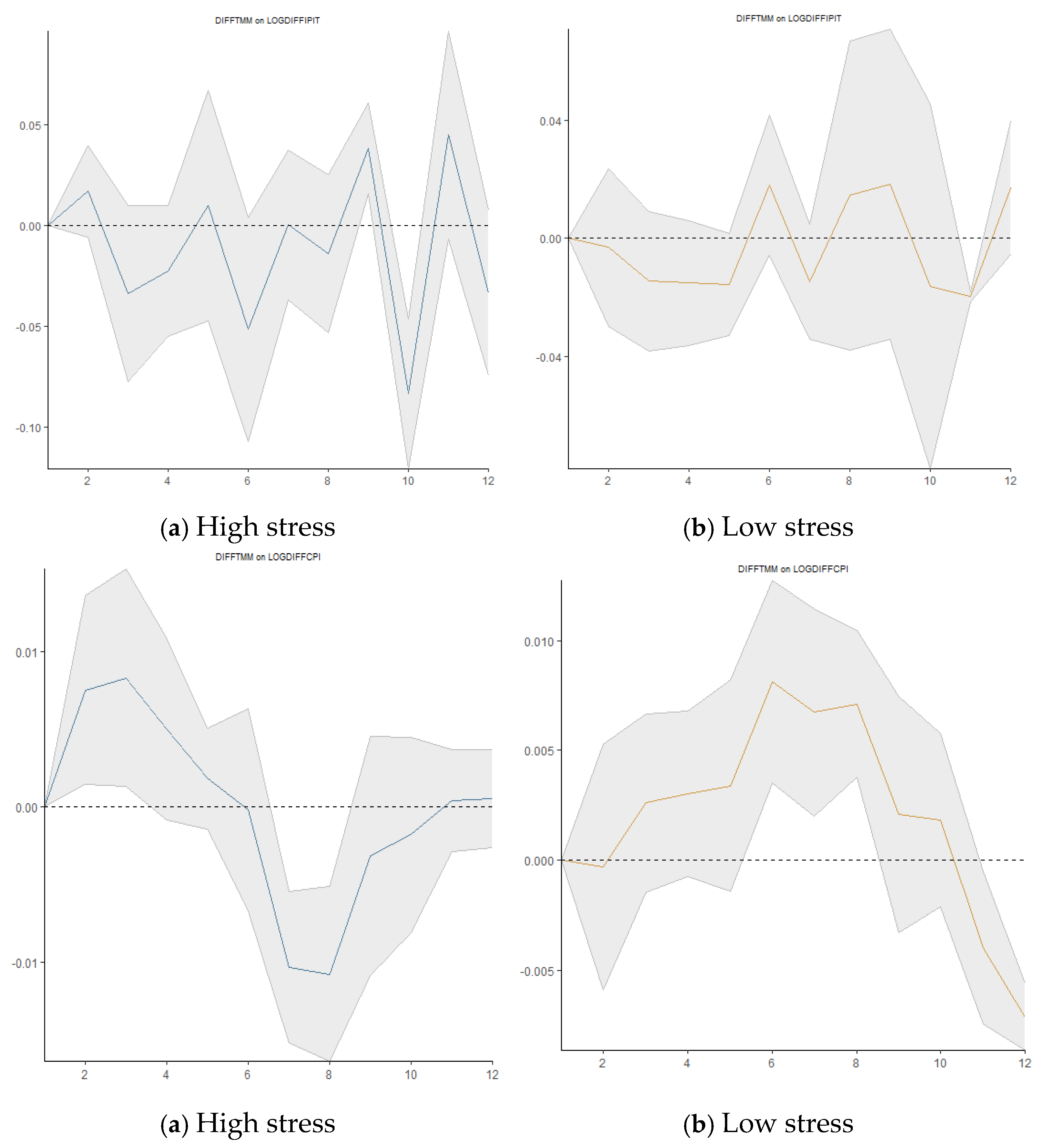

The consumer price index, money market rate, and money supply all rise in response to an oil price uncertainty shock (LOGDIFFOILU), particularly in the most recent quarters. The same shock causes the real effective exchange rate (LOGDIFFTCER) to drop precipitously in the tenth quarter before increasing gradually over the following quarters (see

Figure 12). Because Tunisia is more dependent on imported energy, oil price uncertainty (LOGDIFFOILUI) has a more direct inflationary effect. It may raise consumer prices, lower industrial output, and further devalue the currency. CBT's monetary policy eases restrictions to ensure economic stability.

3.6. Toda-Yamamoto Granger Causality

Recall that all variables are stationary after the first difference. They are integrated of order 1 (I(1)). We therefore follow the approach of Toda and Yamamoto (1995). The maximum choice of lag order (k) of the VAR for variables in levels is selected according to AIC (see Table S.7 in the supplementary file). We then keep the estimate of the VAR with lag=k+dmax=k+1 and perform the Wald test. We consider a bivariate system in the spirit of Siami-Namini (2017):

where

follow a normal distribution with mean 0. In the first part of equation (8), “X does not Granger cause Y if

”. In the second part of the same equation, “Y does not Granger cause X” if