Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

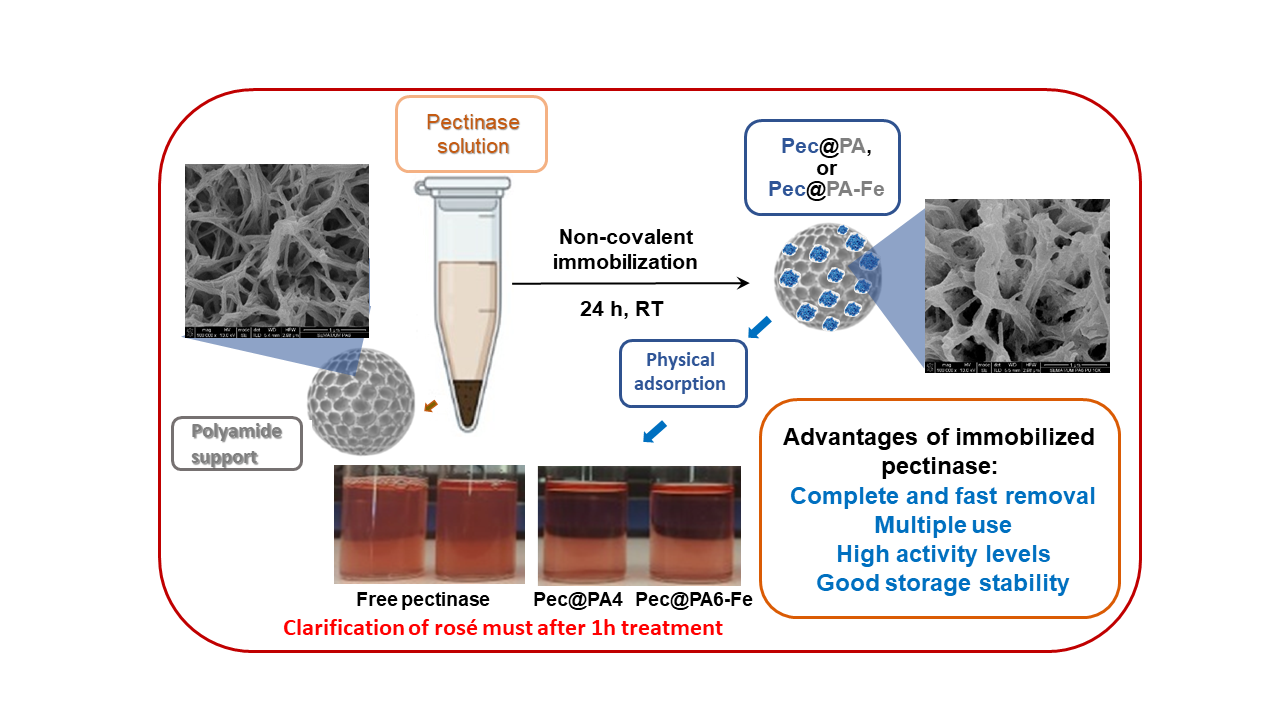

Free pectinase is commonly employed as a biocatalyst in wine clarification; however, its removal, recovery, and reuse are not feasible. To address these limitations, this study focuses on the immobilization of a commercial pectinolytic preparation (Pec) onto highly porous polymer microparticles (MP). Seven microparticulate polyamide (PA) supports, namely PA4, PA6, PA12 (with and without magnetic properties), and the copolymeric PA612 MP, were synthesized through activated anionic ring-opening polymerization of various lactams. Pectinase was noncovalently immobilized on these supports by adsorption, forming Pec@PA conjugates. Comparative activity and kinetic studies revealed that the Pec@PA12 conjugate exhibited more than twice the catalytic efficiency of the free enzyme, followed by Pec@PA6-Fe and Pec@PA4-Fe. All Pec@PA complexes were tested in the clarification of industrial rosé must, demonstrating similar or better performance compared to the free enzyme. Some immobilized biocatalysts supported up to seven consecutive reuse cycles, maintaining up to 50% of their initial activity and achieving complete clarification within 3-30 hours across three consecutive cycles of application. These findings highlight the potential for industrial application of noncovalently immobilized pectinase on various polyamide microparticles, with possibilities for customization of the conjugates' properties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of Different Polyamide MP

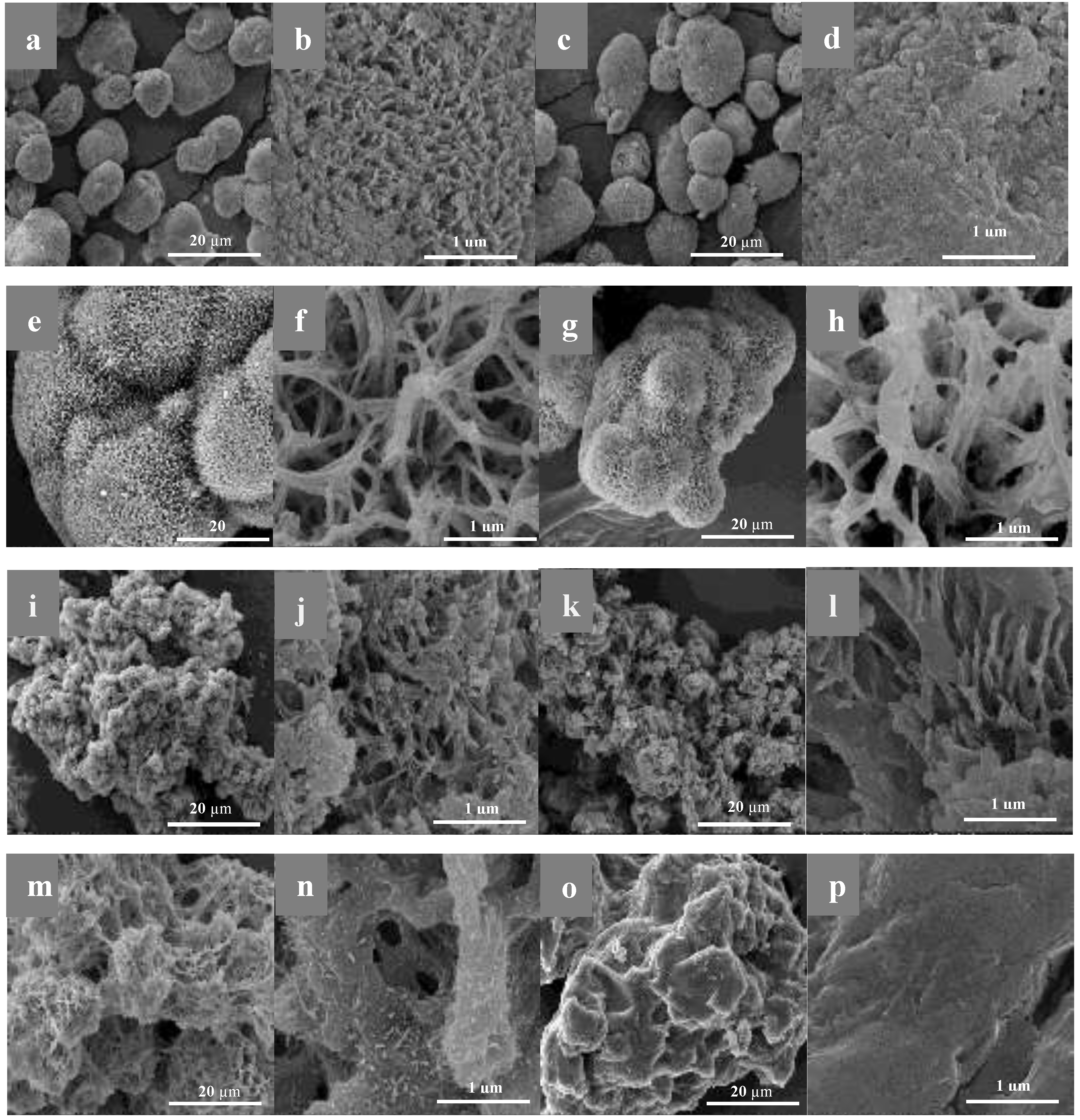

2.2. Morphological Studies by SEM

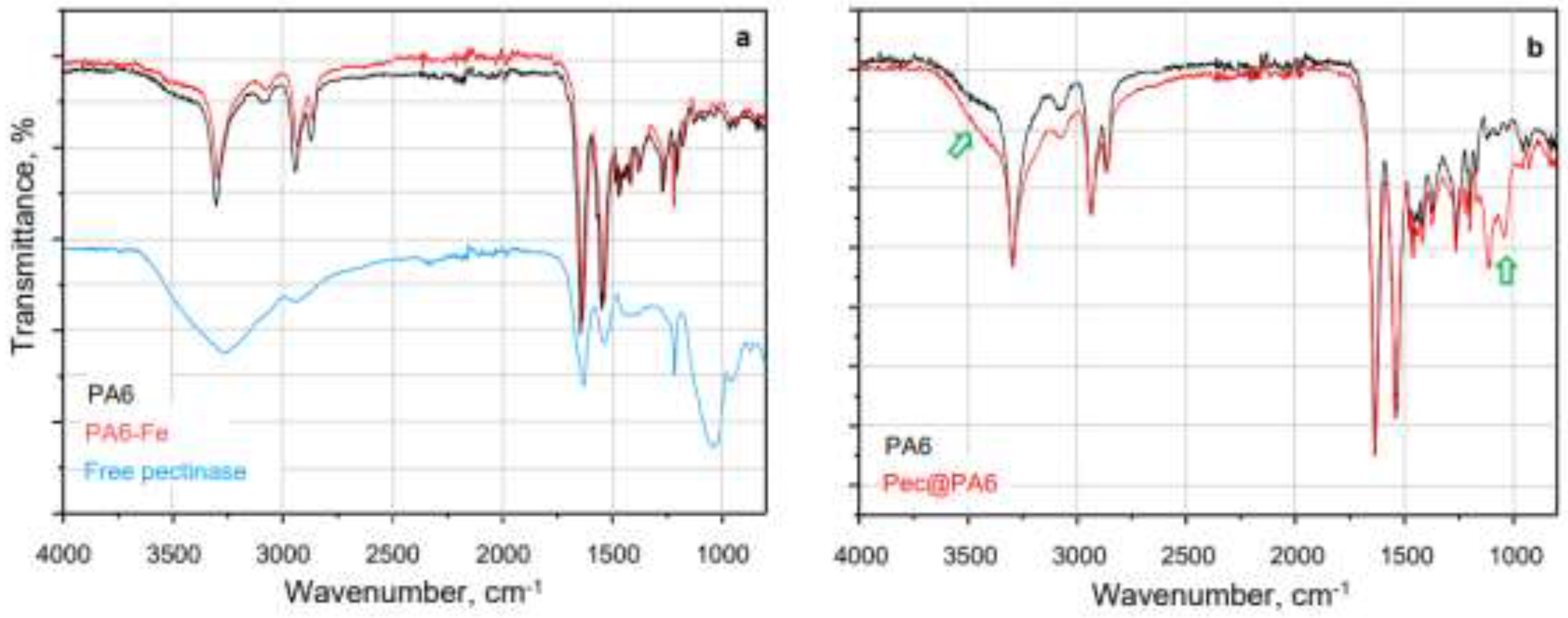

2.3. Noncovalent Immobilization of PEC on PA MP

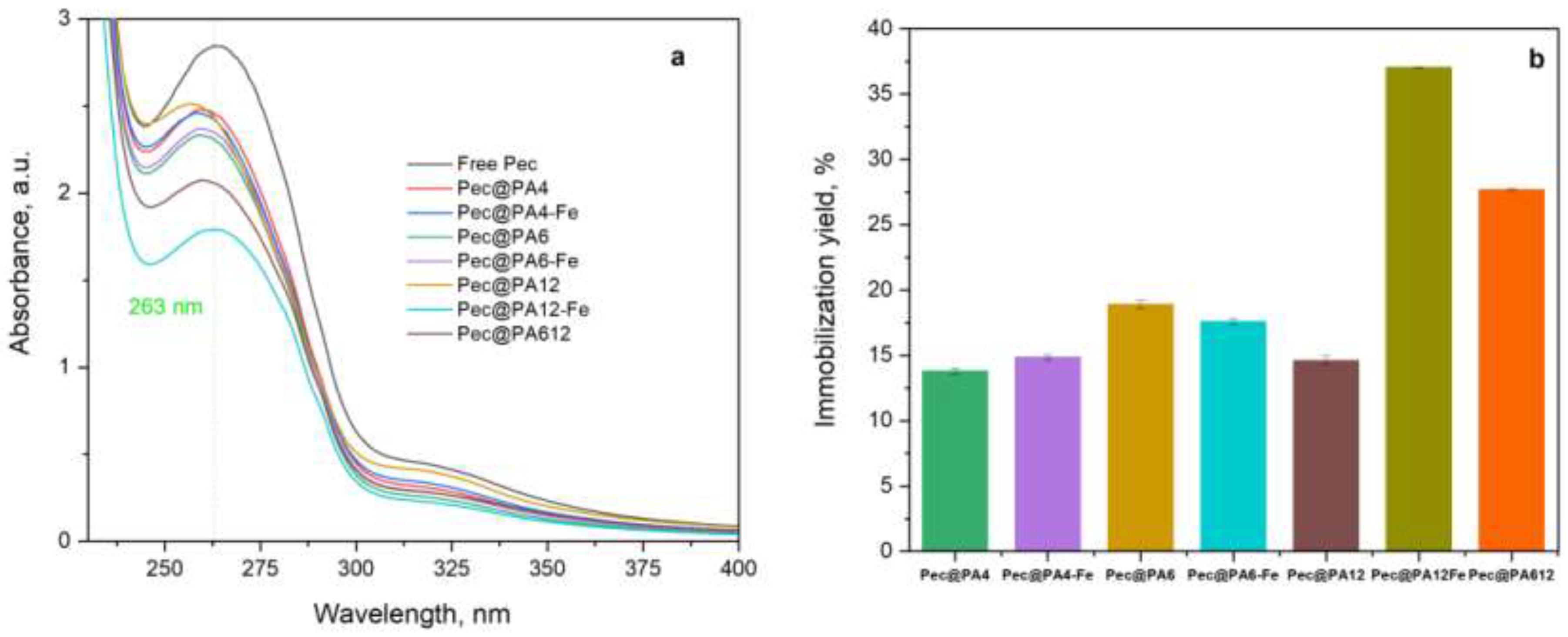

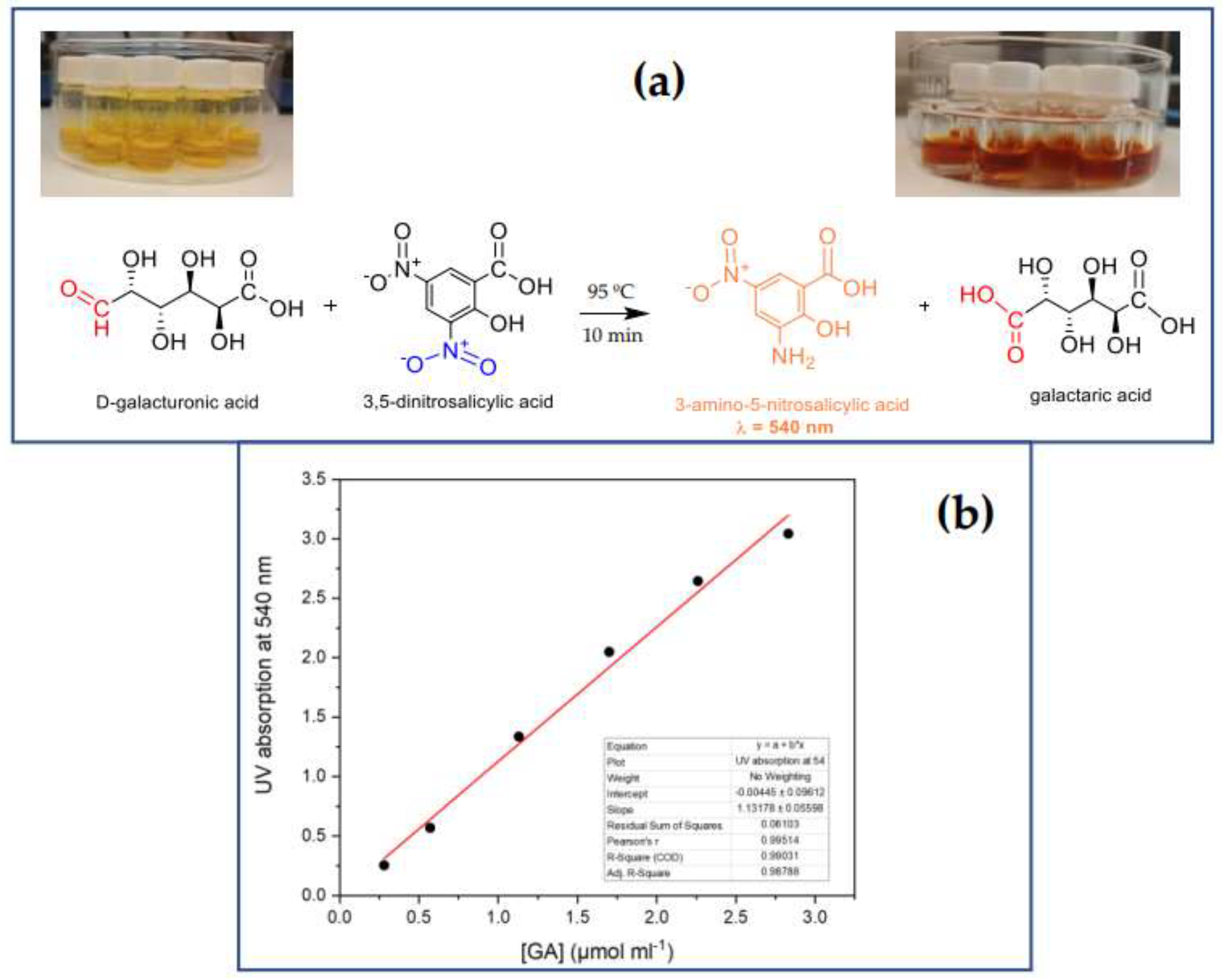

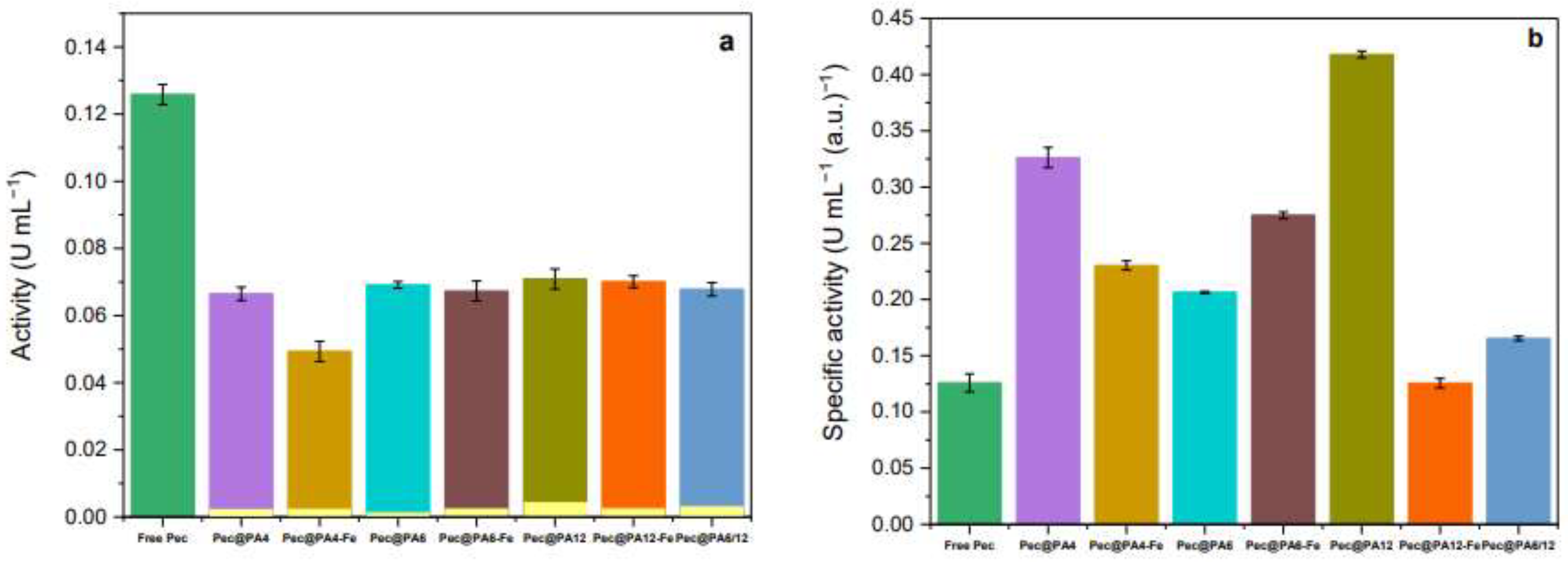

2.4. Activity by the DNS methods

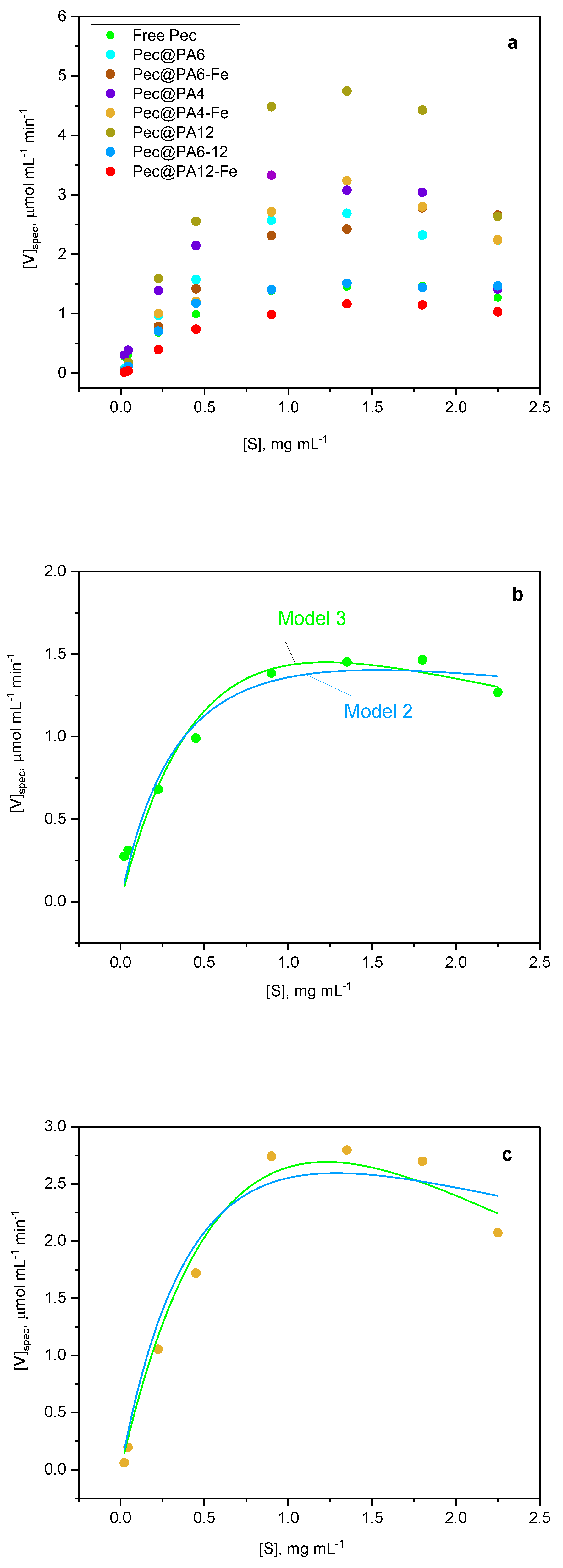

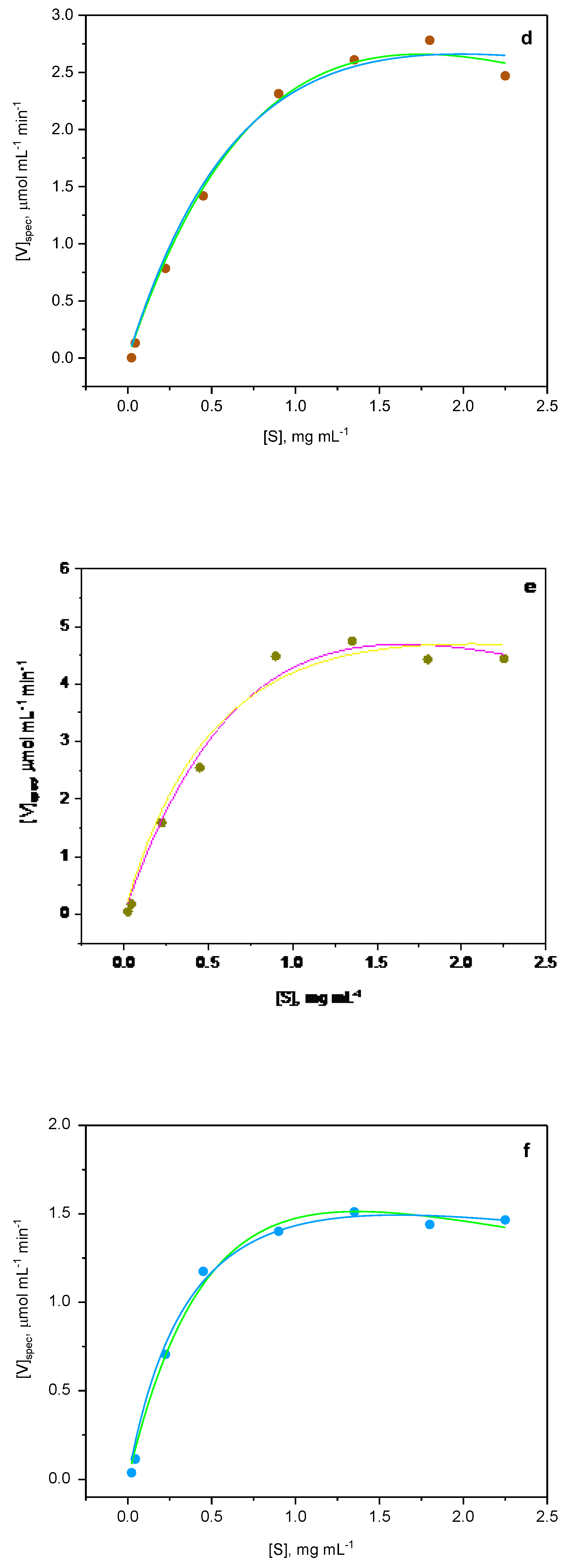

2.5. Kinetics Studies

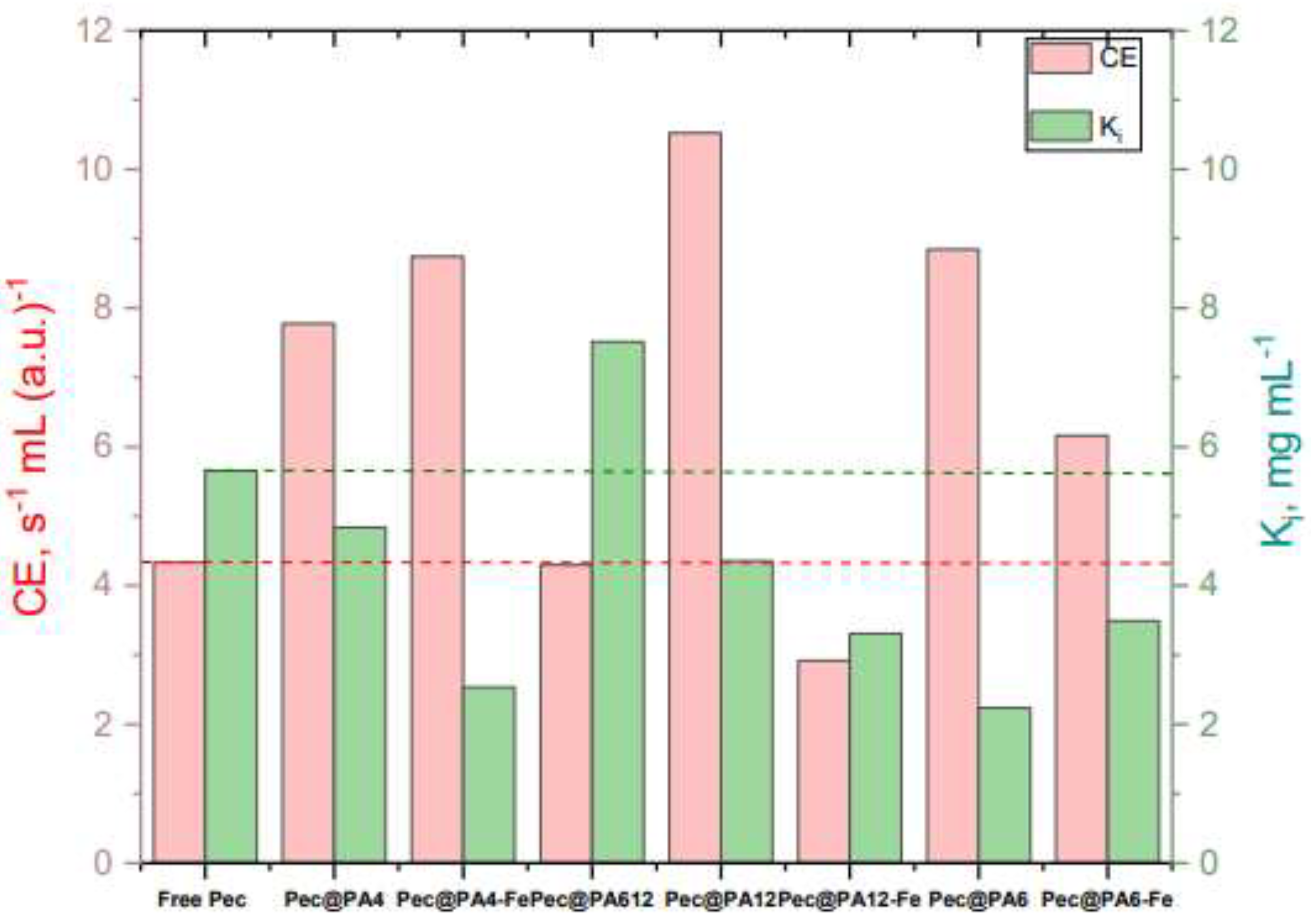

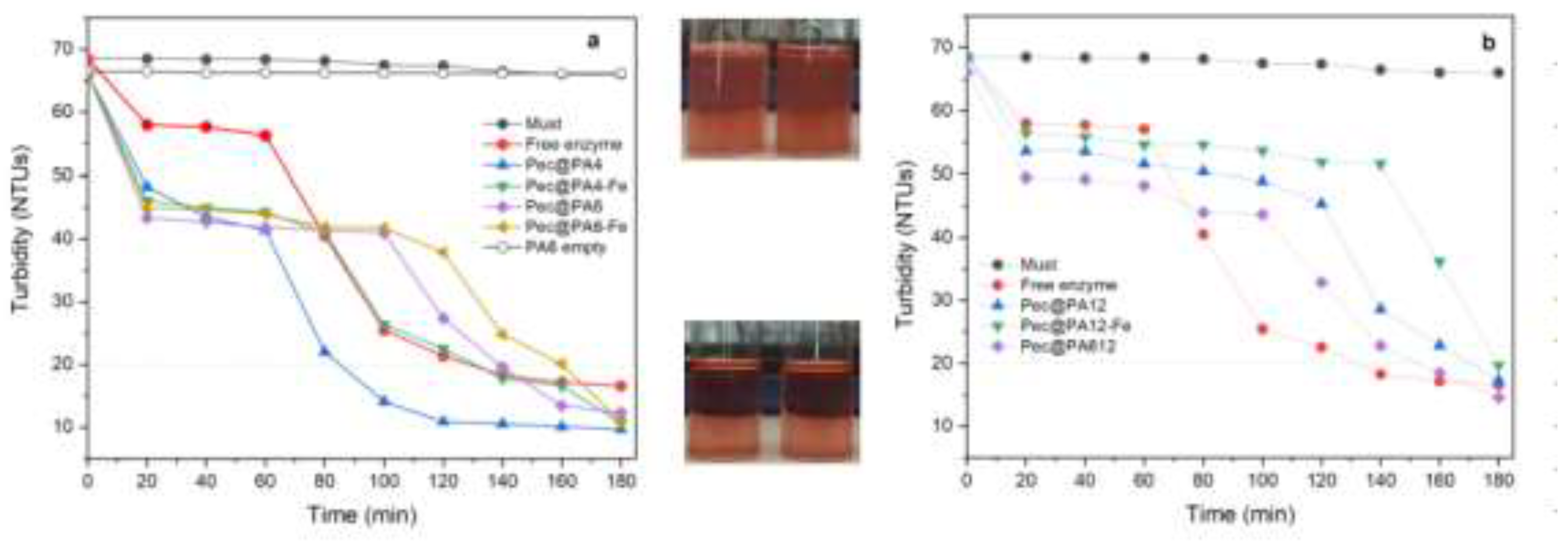

2.6. Rosé Must Clarification

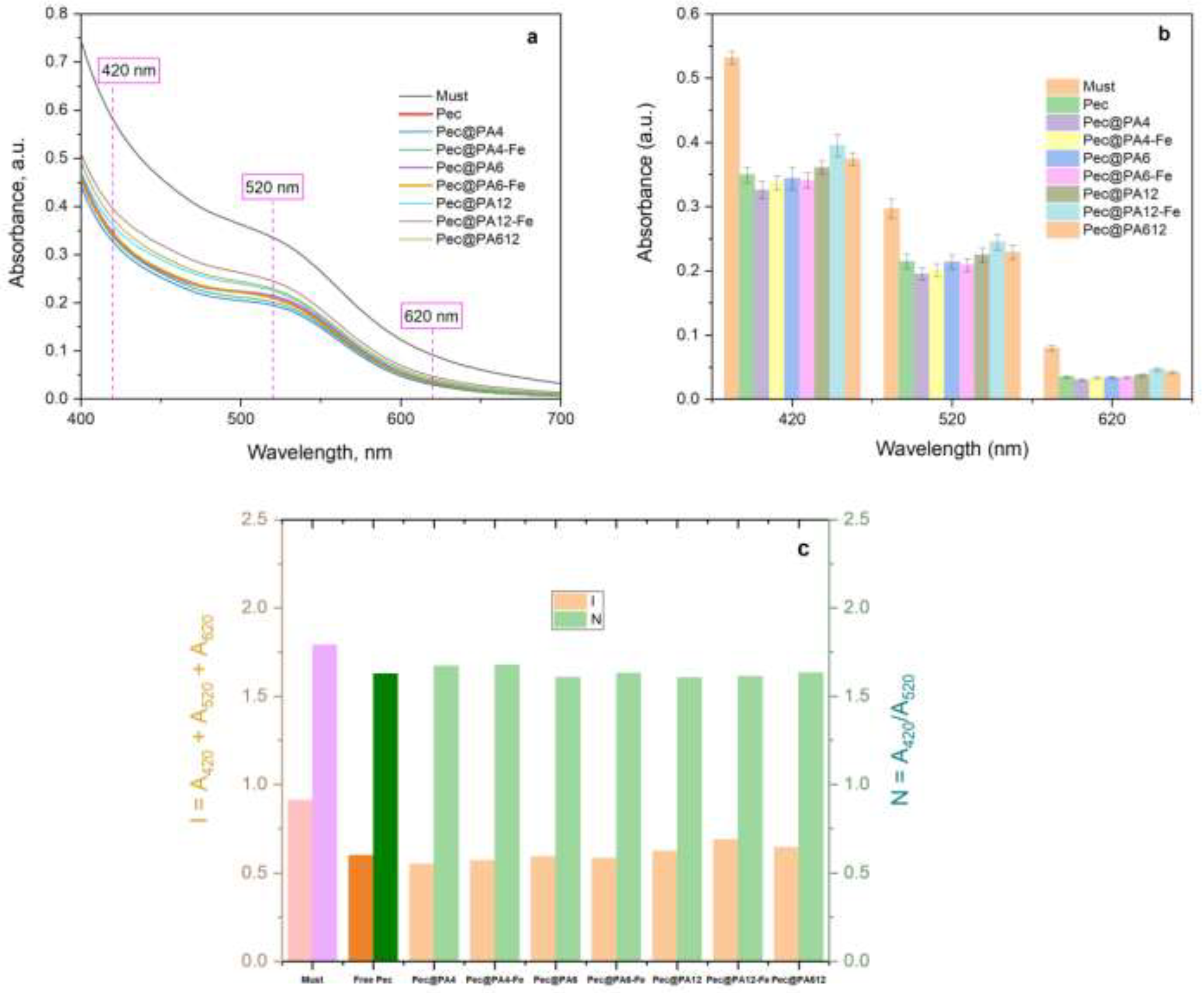

2.7.Color Retention After Clarification

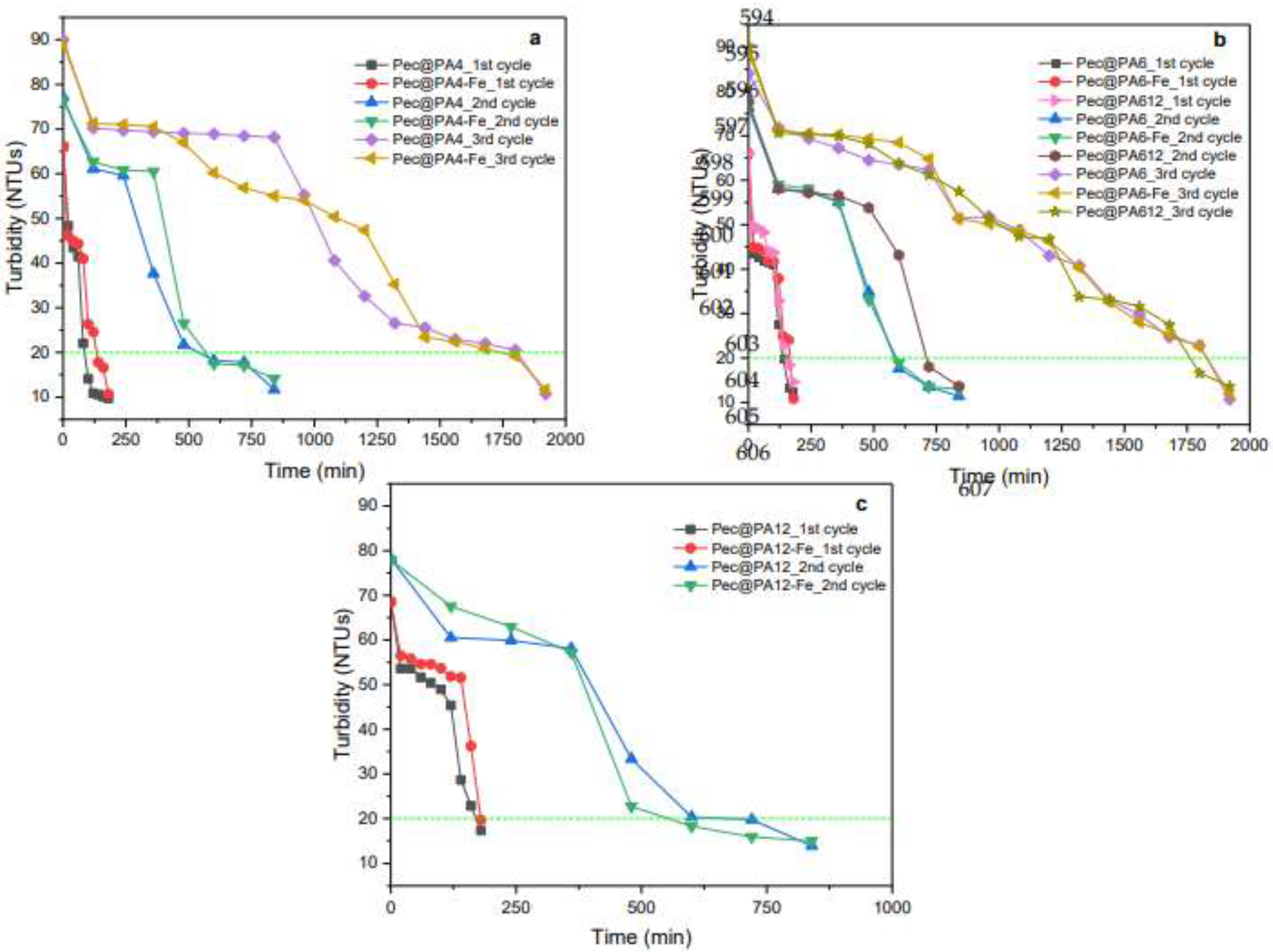

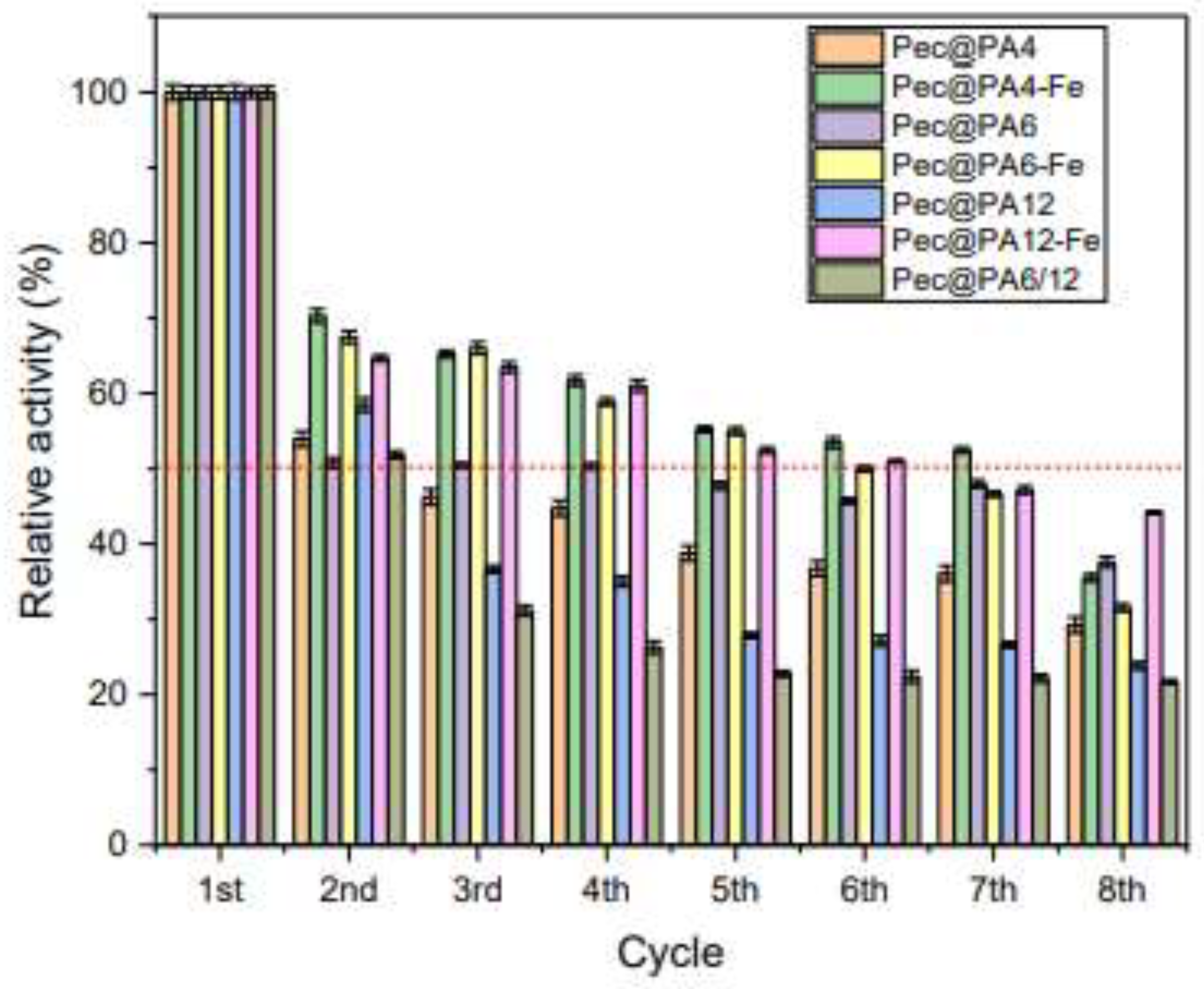

2.8. Multiple Use of Pec@PA Conjugates

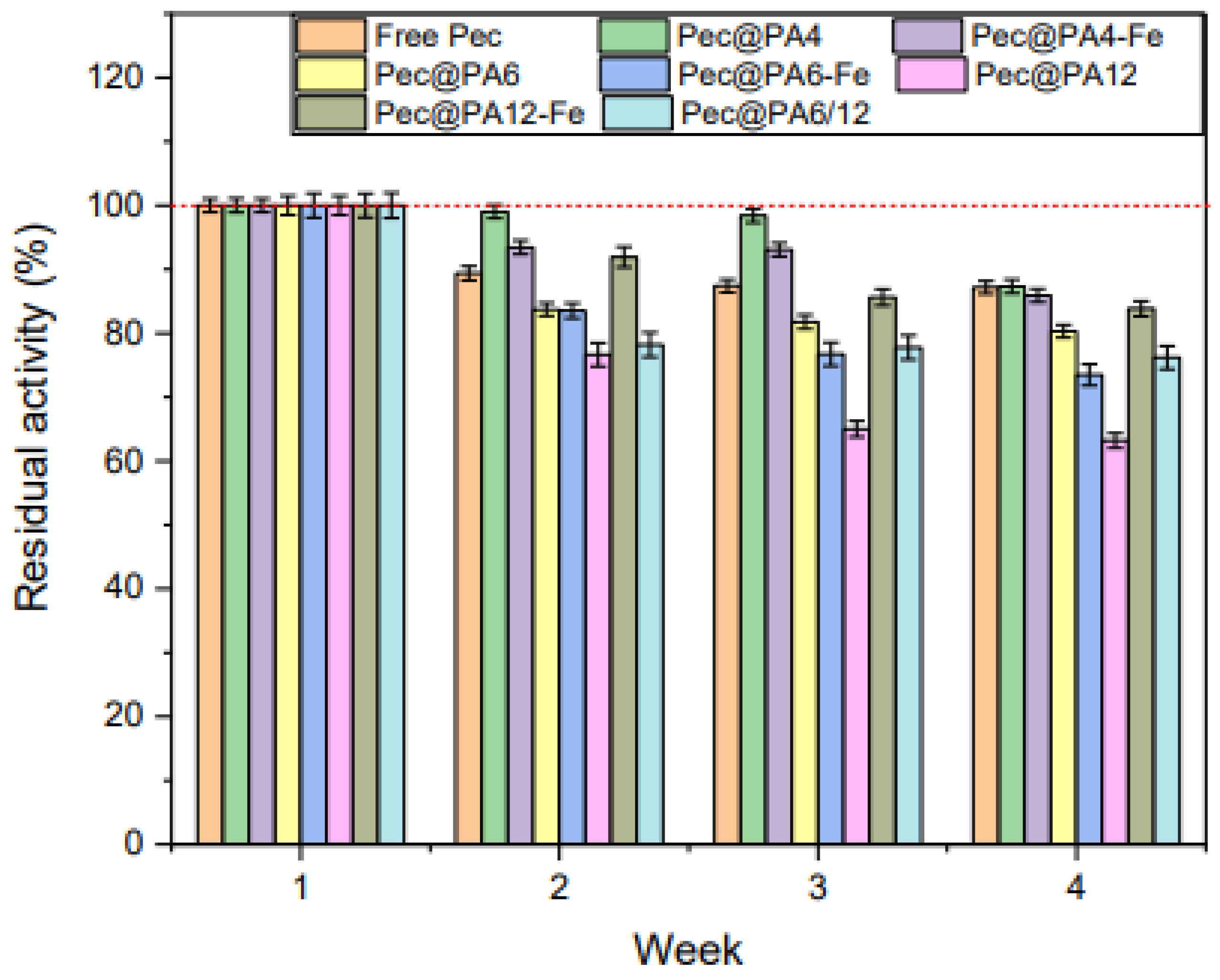

2.9. Storage Stability of Pec@PA Conjugates

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Characterization Methods

3.3. Synthesis of PA6 Microparticles

3.4 Immobilization of Pectinase by Physical Absorption

3.5 Determination of the Total Amount of Protein

3.6. Pectinase Activity Assay

3.7. Kinetics of Pectin Degradation

3.8. Application of Immobilized Pectinase for Rosé Must Clarification

3.9. Color Analyses

3.10. Reusability Studies

3.11. Storage Stability Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodicio, R.; Heinisch, J. Carbohydrate Metabolism in Wine Yeasts. In Biology of Microorganisms on Grapes, in Must and in Wine, 2nd ed.; Konig, H., Unden, G., Frohlich, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 189–214. [CrossRef]

- Ottone, C.; Romero, O.; Aburto, C.; Illanes, A.; Wilson, L. Biocatalysis in the winemaking industry: Challenges and opportunities for immobilized enzymes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 595–621. [CrossRef]

- Mojsoc, K. Use of enzymes in wine making: A review. Int. J. Mark. Technol. 2013, 3, 112–127.

- Pretorius, I.S. Tailoring wine yeast for the new millennium: Novel approaches to the ancient art of winemaking. Yeast. 2000, 16, 675–729. [CrossRef]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Donèche, B.; Lonvaud, A. White winemaking, chapter 13. In Handbook of Enology: The Microbiology of Wine and Vinifications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 421-429; 445-448.

- Espejo, F. Role of commercial enzymes in wine production: a critical review of recent research. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Kassara, S.; Li, S.; Smith, P.; Blando, F.; Bindon, K. Pectolytic enzyme reduces the concentration of colloidal particles in wine due to changes in polysaccharide structure and aggregation properties, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 546-555. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S.Q. Effects of pectinase treatment on the physicochemical and oenological properties of red dragon fruit wine fermented with Torulaspora delbrueckii, LWT 2020, 132, 109929. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.M.; Coutinho, P.; Delgadillo I.; Cardoso, A.D.; Coimbra, M.A. Effect of enzymatic aroma release on the volatile compounds of white wines presenting different aroma potentials, J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Jayani, R.S.; Saxena, S.; Gupta, R. Microbial pectinolytic enzymes: A review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 2931–2944. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.C.; López, O.V.; Ciolino, A.E.; Morata, V.I.; Villar, M.A.; Ninago, M.D. Immobilization of enological pectinase in calcium alginate hydrogels: A potential biocatalyst for winemaking. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101091. [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Lombardelli, C.; Cacciotti, I.; Liburdi, K.; Nanni, F.; Esti, M. Immobilized native plant cysteine proteases: Packed-bed reactor for white wine protein stabilization. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1130–1139. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Strategies for the one-step immobilization–purification of enzymes as industrial biocatalysts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 435–456. [CrossRef]

- Yushkova, E.D.; Nazarova, E.A.; Matyuhina, A.V.; Noskova, A.O.; Shavronskaya, D.O.; Vinogradov, V.V.; Skvortsova, N.N.; Krivoshapkina, E.F. Application of Immobilized Enzymes in Food Industry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11553–11567. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.S.; Khodaiyan, F.; E. Mousavi, S.M.; Kennedy, J.F.; Azimi, S.Z. A Health-Friendly Strategy for Covalent-Bonded Immobilization of Pectinase on the Functionalized Glass Beads. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 14, 177–186. [CrossRef]

- Behram, T.; Pervez, S.; Nawaz, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Jan, A.U.; Rehman, H.U.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, N.M.; Khan, F.A. Development of Pectinase Based Nanocatalyst by Immobilization of Pectinase on Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Using Glutaraldehyde as Crosslinking. Agent. Molecules 2023, 28, 404. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U.; Nawaz, M.A.; Pervez, S.; Jamal, M.; Attaullah, M.; Aman, A.; Qader, A.U. Encapsulation of pectinase within polyacrylamide gel: characterization of its catalytic properties for continuous industrial uses. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04578. [CrossRef]

- Rajdeo, K.; Harini, T.; Lavanya, K.; Fadnavis, N. W. Immobilization of pectinase on reusable polymer support for clarification of apple juice. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 99, 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.; Meng, L.; Huang, L., Ni, Y.; Chen, L. Immobilization and Characterization of Pectinase onto the Cationic Polystyrene Resin. ACS Omega. 2021, 6, 31683-31688. [CrossRef]

- Omelková, J.; Rexová-Benková, Ł.; Kubánek, V.; Veruovič, B. Endopolygalacturonase immobilized on a porous poly(6-caprolactame). Biotechnol Lett. 1985, 7, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Rexová-Benková, L.; Omelková, J.; Veruovič, B.; Kubánek, V. Mode of action of endopolygalacturonase immobilized by adsorption and by covalent binding via amino groups. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989, 34, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.K.; Saxena, S.; Thakur, J.; Gupta, R. Immobilization of polygalacturonase from Aspergillus Niger onto glutaraldehyde activated Nylon-6 and its application in apple juice clarification. Acta Aliment. 2010, 39, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Othman, S.; Rinken, T. Immobilization of Pectinolytic Enzymes on Nylon 6/6 Carriers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4591. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, P.; Manjón, A.; Iborra, J.L.; Gálvez, D.M. Characteristics of the immobilized pectin lyase activity from a commercial pectolytic enzyme preparation. Acta Biotechnol. 1990, 10, 531–539. [CrossRef]

- Diano, N.; Grimaldi, T.; Bianco, M.; Rossi, S.; Gabrovska, K.; Yordanova, G.; Godjevargova, T.; Grano, V.; Nicolucci, C.; Mita, L.; et al. Apple Juice Clarification by Immobilized Pectolytic Enzymes in Packed or Fluidized Bed Reactors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11471–11477. [CrossRef]

- Dencheva, N.; Denchev, Z.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Ezquerra, T.E. One-step in-situ synthesis of polyamide microcapsules with inorganic payload and their transformation into responsive thermoplastic composite materials. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2016, 301, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.C.; Dencheva, N.V.; Denchev, Z.Z. Immobilization of Enological Pectinase on Magnetic Sensitive Polyamide Microparticles for Wine Clarification. Foods 2024, 13, 420. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Chen, Y.-X. Completely Recyclable Biopolymers with Linear and Cyclic Topologies via Ring-Opening Polymerization of γ-Butyrolactone. Nature Chem, 2016, 8, 42-49. [CrossRef]

- Brêda, C.; Dencheva, N.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Denchev, Z. Preparation and properties of metal-containing polyamide hybrid composites via reactive microencapsulation. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 10534–10554. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Gummadi, S.N.; Panda, T. Analysis of Kinetic Data of Pectinases with Substrate Inhibition. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 13, 332–337.

- Haldane, J.B.S. Enzymes, Featured ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, USA, 1965; pp. 154-196.

- Edwards, V.H. Influence of high substrate concentration on microbial kinetics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1970, 27, 679-712. [CrossRef]

- Cleland W.W. Substrate Inhibition, chapter 20. In Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism – Part A: Initial Rate and Inhibition Methods. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976, volume 63, pp. 500-513.

- IOV (International Organization of Vine and Wine). Compendium of international methods of wine and must analysis - Chromatic Characteristics (Type-IV). OIV-MA-AS2-07B. 2022. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis (accessed on October 16, 2024).

- Faragó, P.; Gălătuș, R.; Hintea, S.; Boșca, A.B.; Feurdean, C.N.; Ilea, A. An Intra-Oral Optical Sensor for the Real-Time Identification and Assessment of Wine Intake. Sensors 2019, 19, 4719. [CrossRef]

- Dencheva, N.; Braz, J.; Nunes, T.G.; Oliveira, F.D.; Denchev, Z. One-pot low temperature synthesis and characterization of hybrid poly(2-pyrrolidone) microparticles suitable for protein immobilization. Polymer 2018, 145, 402–415. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Yield of poly- mer, % |

Oligo- mers1, wt.% |

Mη kDa2 |

Average particle size, µm | Average pore size, nm |

Fe content4, wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA4 | 59.4 | 4.4 | 26.4 | 10-25 | 50-120 | - |

| PA4-Fe | 61.2 | 5.9 | - 3 | 10-40 | 120-250 | 1.0 [1.6] |

| PA6 | 56.0 | 2.0 | 33.7 | 50-150 | 300-500 | - |

| PA6-Fe | 58.8 | 2.4 | - | 50-200 | 200-300 | 3.0 [5.6] |

| PA12 | 42.0 | 3.2 | 33.8 | 50-700 | 250-900 | - |

| PA12-Fe | 58.5 | 3.4 | - | 50-80 | 750-1500 | 2.0 [4.2] |

| PA612 | 77.0 | 2.1 | 28.9 | 100-150 | 250-2000 | - |

| Biocatalyst | Parameters a) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Pec |

Vmax Km Ki |

1.956 ± 0.024 | 2.182 ± 0.071 | 1.933 ± 0.001 |

| 0.423 ± 0.009 | 0.423 ± 0.043 | 0.446 ± 0.041 | ||

| ≈ 3.0 | 5.520 ± 0.850 | 5.656 ± 0.687 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.995 | 0.958 | 0.997 | |

| Pec@PA4 | Vmax | 5.672 ± 0.020 | 9.364 ± 0.014 | 5.592 ± 0.101 |

| Km | 0.752 ± 0.010 | 1.444 ± 0.035 | 0.720 ± 0.020 | |

| Ki | 2.5 - 3.0 | 1.920 ± 0.060 | 4.838 ± 0.304 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.989 | 0.965 | 0.994 | |

| Pec@PA4-Fe | Vmax | 4.193 ± 0.027 | 5.387 ± 0.015 | 5.981 ± 0.164 |

| Km | 0.662 ± 0.012 | 0.695 ± 0.012 | 0.684 ± 0.027 | |

| Ki | 2.0 - 3.0 | 2.390 ± 0.025 | 2.536 ± 0.100 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.977 | 0.981 | 0.985 | |

| Pec@PA6 | Vmax | 4.669 ± 0.020 | 5.568 ± 0.005 | 7.679 ± 0.170 |

| Km | 0.863 ± 0.009 | 0.887 ± 0.002 | 0.868 ± 0.050 | |

| Ki | ≈ 2.5 | 2.359 ± 0.021 | 2.236 ± 0.131 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 0.995 | |

| Pec@PA6-Fe | Vmax | 5.100 ± 0.020 | 6.136 ± 0.003 | 6.133 ± 0.644 |

| Km | 1.222 ± 0.008 | 1.297 ± 0.002 | 0.995 ± 0.020 | |

| Ki | ≈ 2.5 – 3.0 | 3.035 ± 0.060 | 3.491 ± 0.554 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.995 | 0.998 | 0.984 | |

| Pec@PA12 | Vmax | 8.666 ± 0.019 | 8.335 ± 0.016 | 8.408 ± 0.196 |

| Km | 1.010 ± 0.007 | 0.869 ± 0.032 | 0.799± 0.030 | |

| Ki | ≈ 2.5 | 5.323 ± 0.066 | 4.354 ± 0.226 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.990 | |

| Pec@PA12-Fe | Vmax | 1.872 ± 0.070 | 2.217 ± 0.040 | 2.395 ± 0.040 |

| Km | 0.820 ± 0.020 | 0.855 ± 0.030 | 0.821 ± 0.019 | |

| Ki | ≈ 2.5 | 3.737 ± 0.021 | 3.308 ± 0.167 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.976 | 0.993 | 0.994 | |

| Pec@PA612 | Vmax | 1.931 ± 0.043 | 2.254 ± 0.020 | 1.924 ± 0.020 |

| Km | 0.372 ± 0.022 | 0.454 ± 0.010 | 0.448 ± 0.020 | |

| Ki | ≈ 5.0 | 5.708 ± 0.083 | 7.516 ± 0.539 | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.966 | 0.990 | 0.993 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).