Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data Collection

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethnopharmacological Use, Phytochemistry and Toxicity

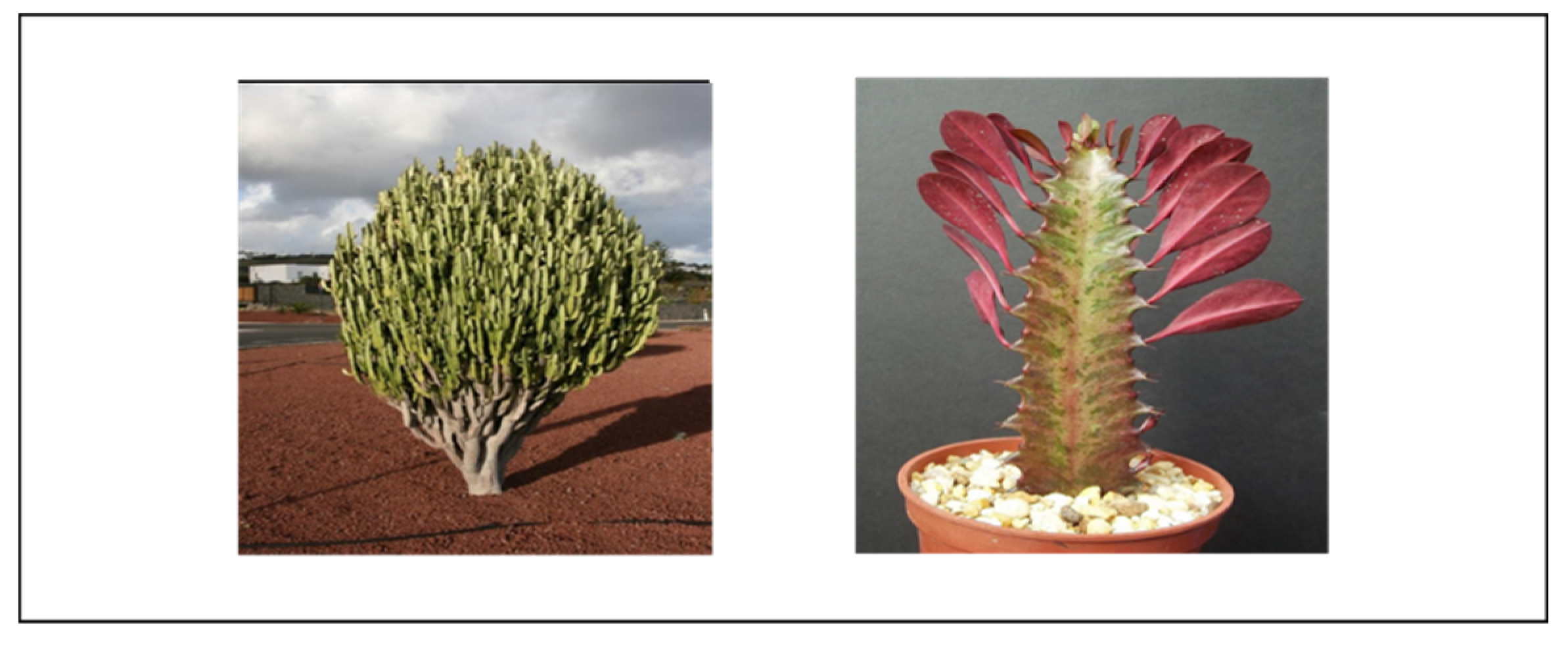

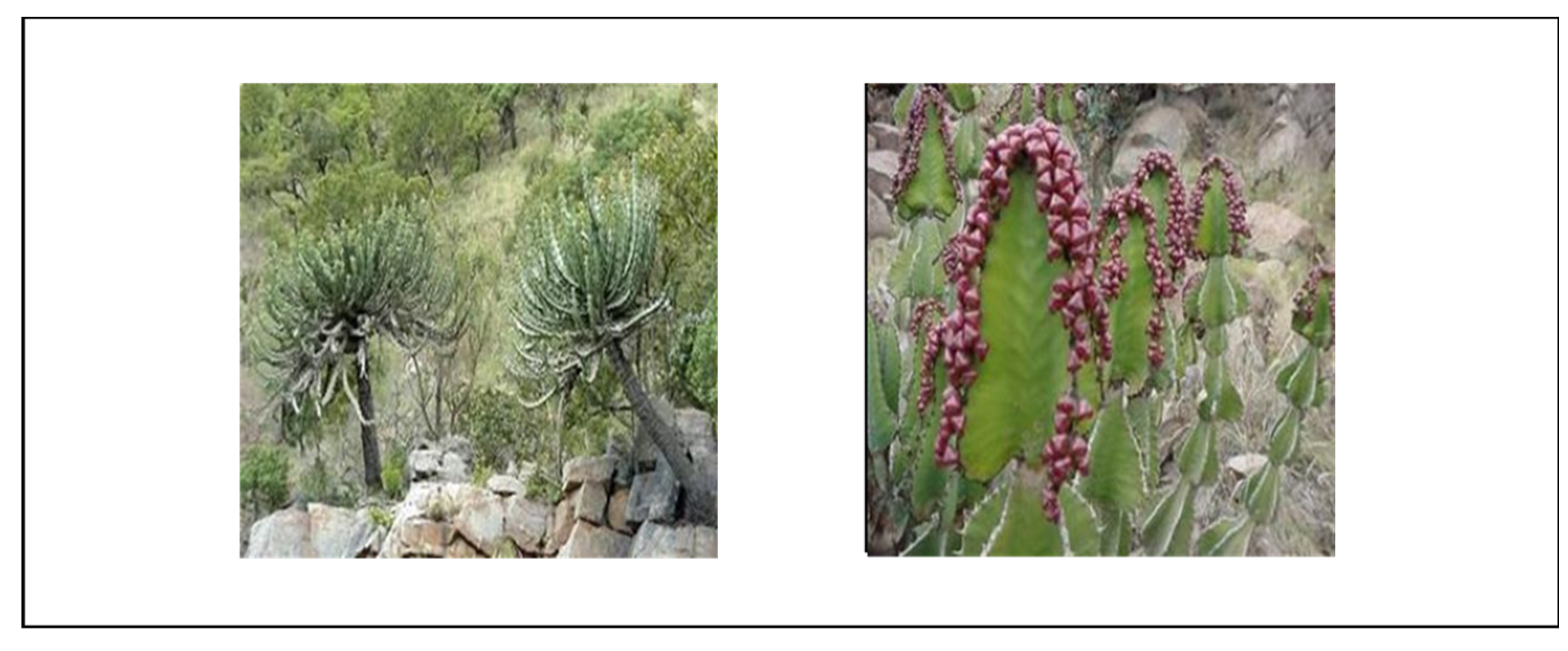

4.1.1. Euphorbia trigona

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

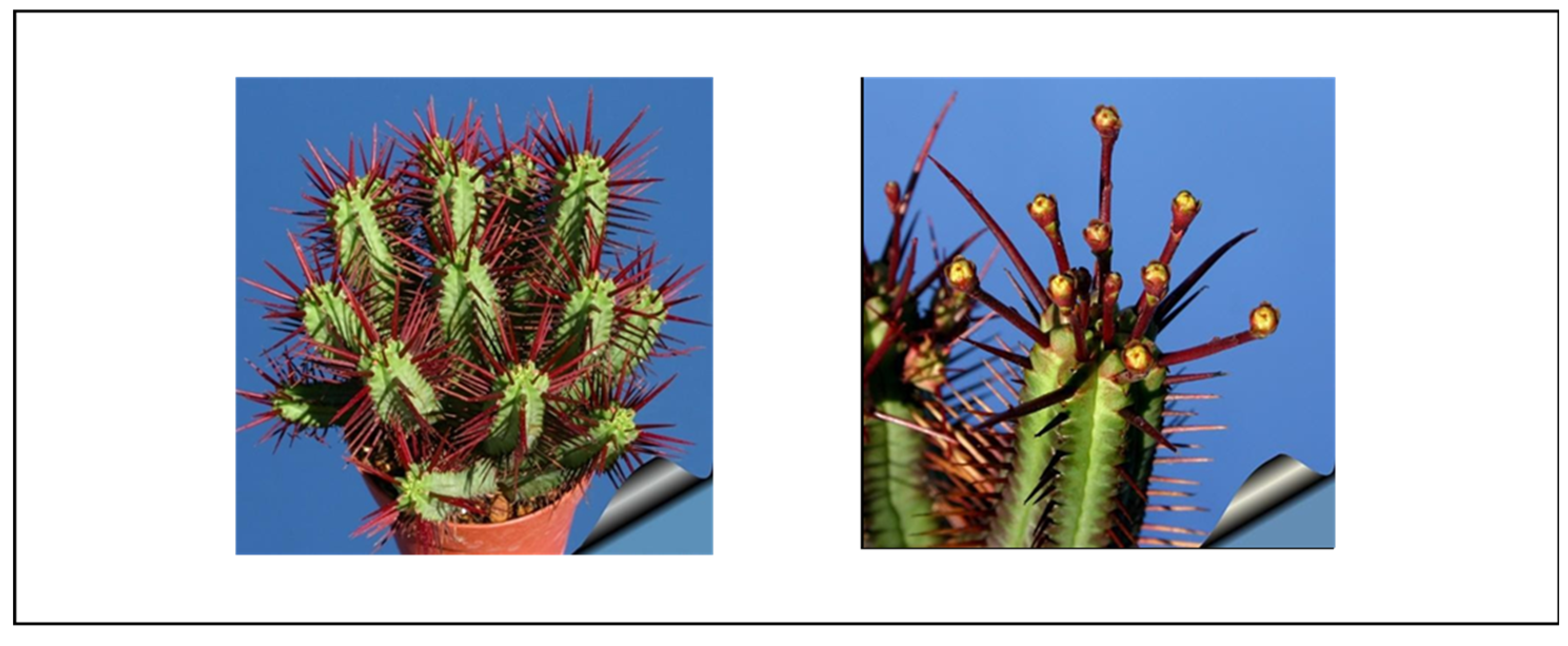

4.1.2. Euphorbia ledienii

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

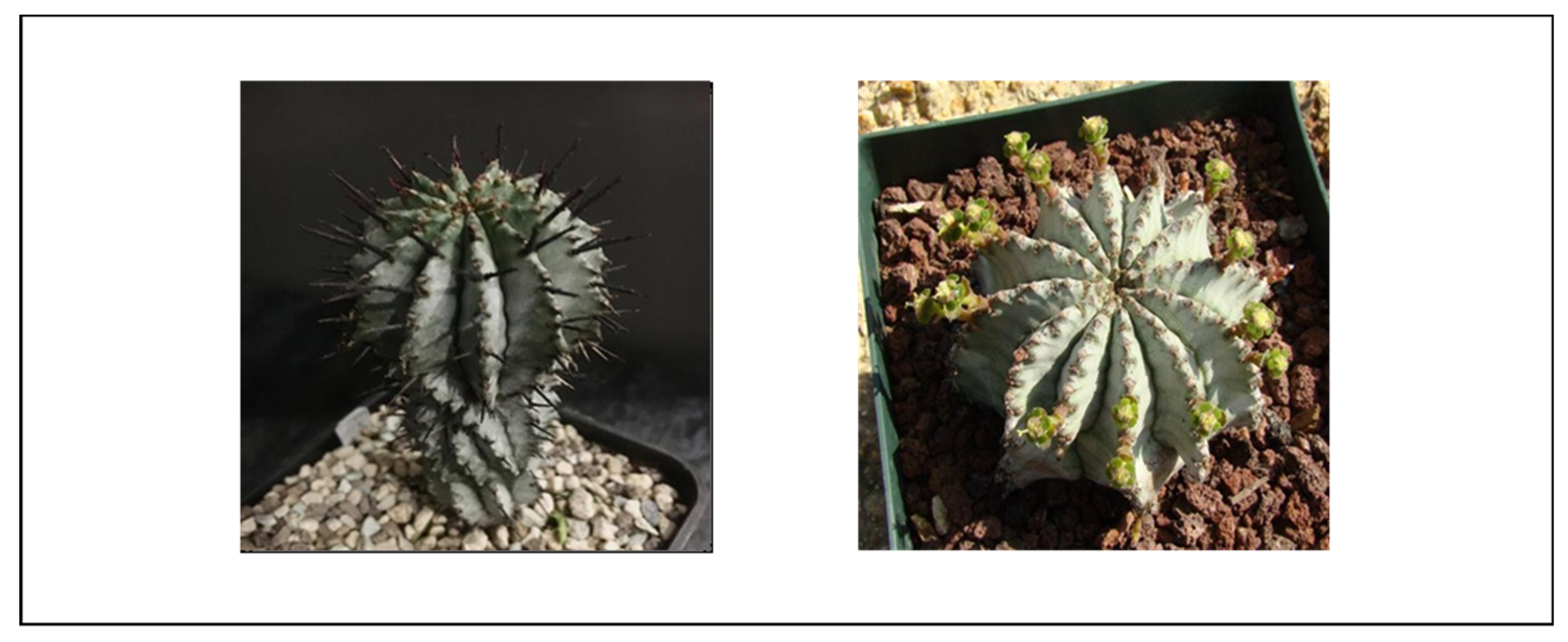

4.1.3. Euphorbia horrida

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.4. Euphorbia enopla

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

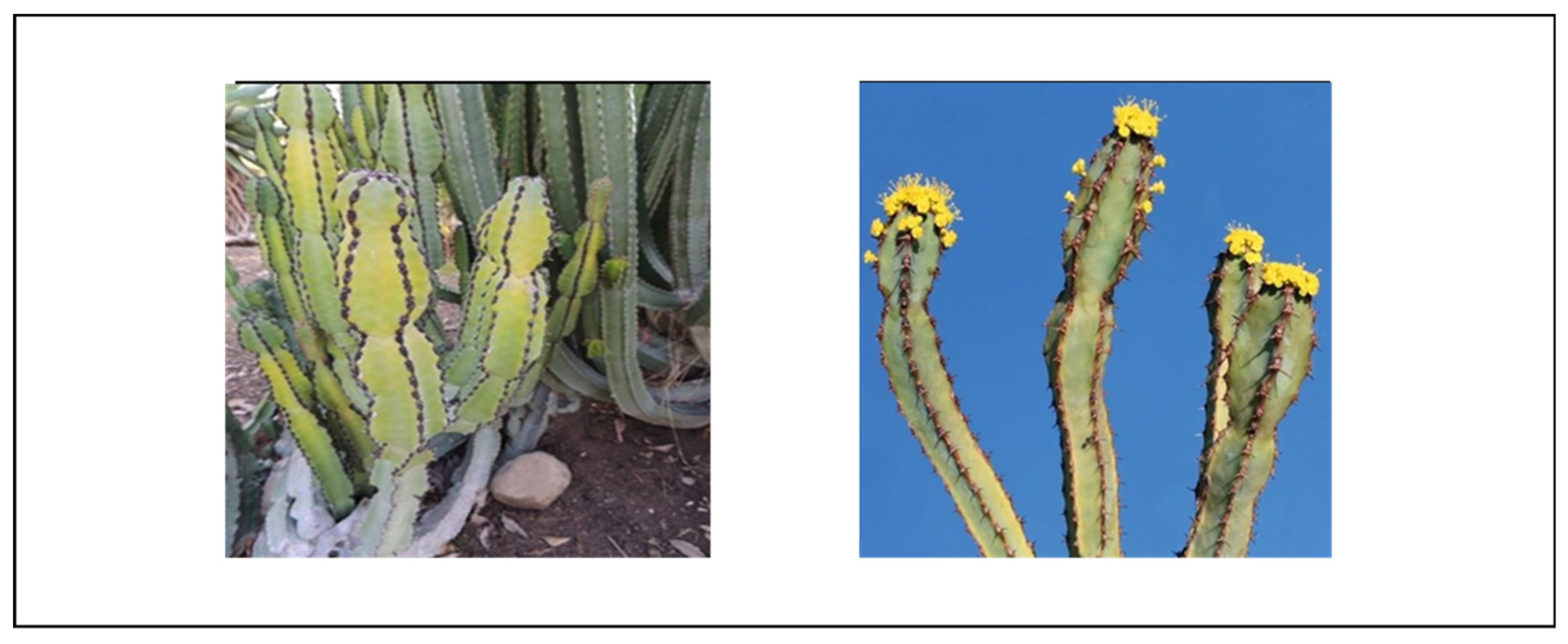

4.1.5. Euphorbia coerulescens

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

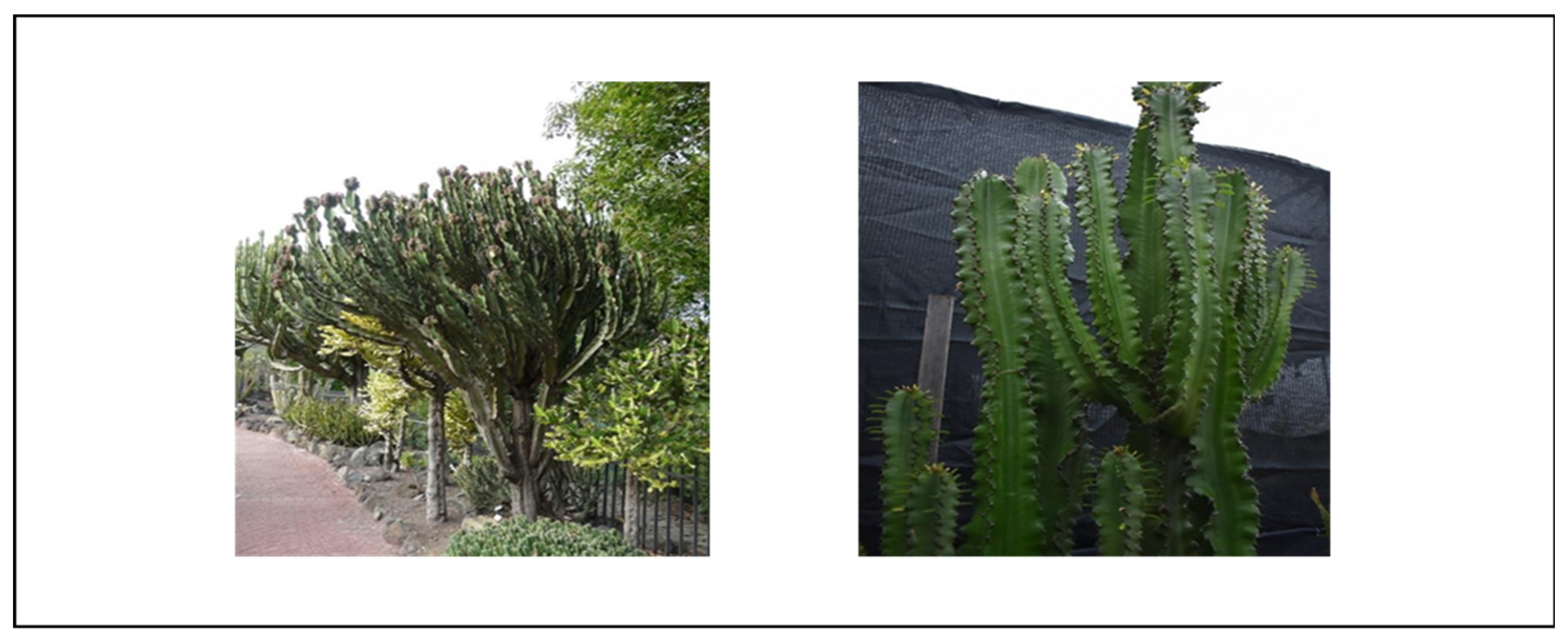

4.1.6. Euphorbia cooperi

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.7. Euphorbia tirucalli

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.8. Euphorbia ammak

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

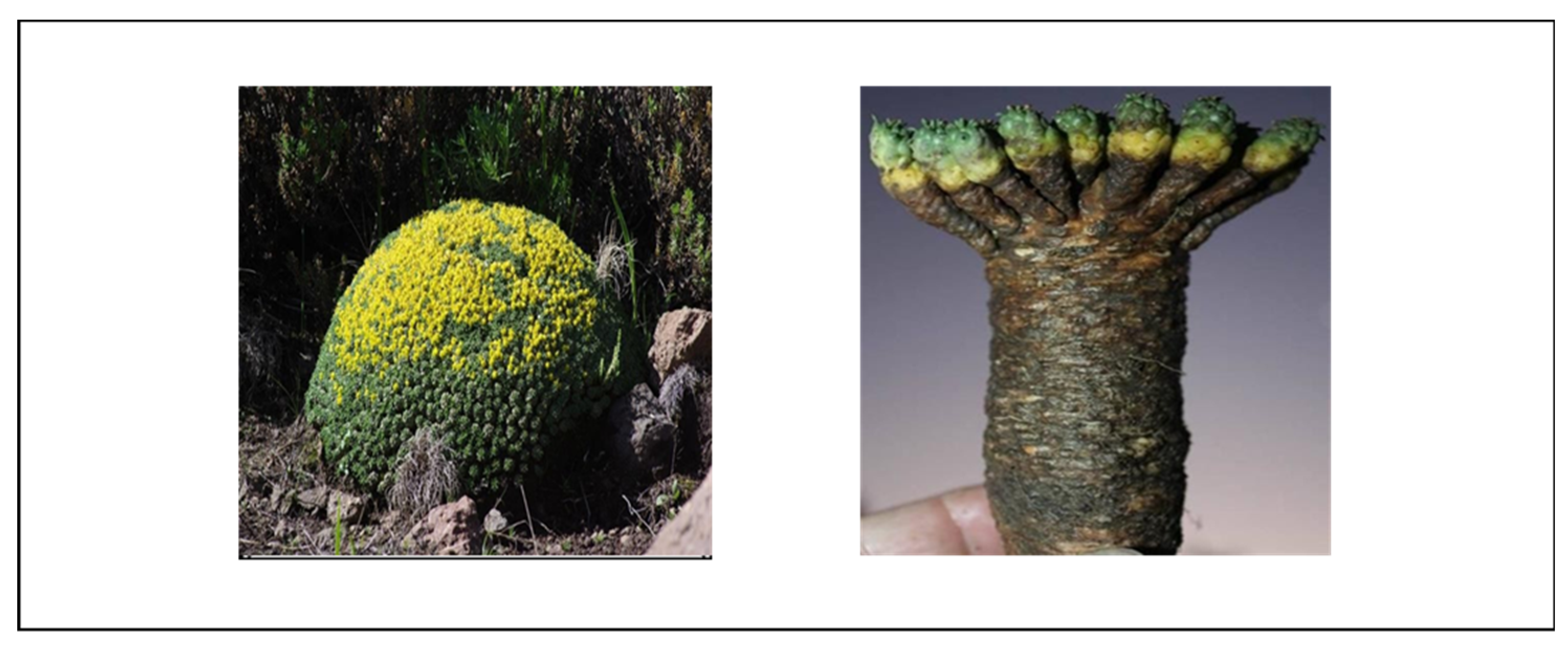

4.1.9. Euphorbia clavarioides

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.10. Euphorbia gorgonis

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

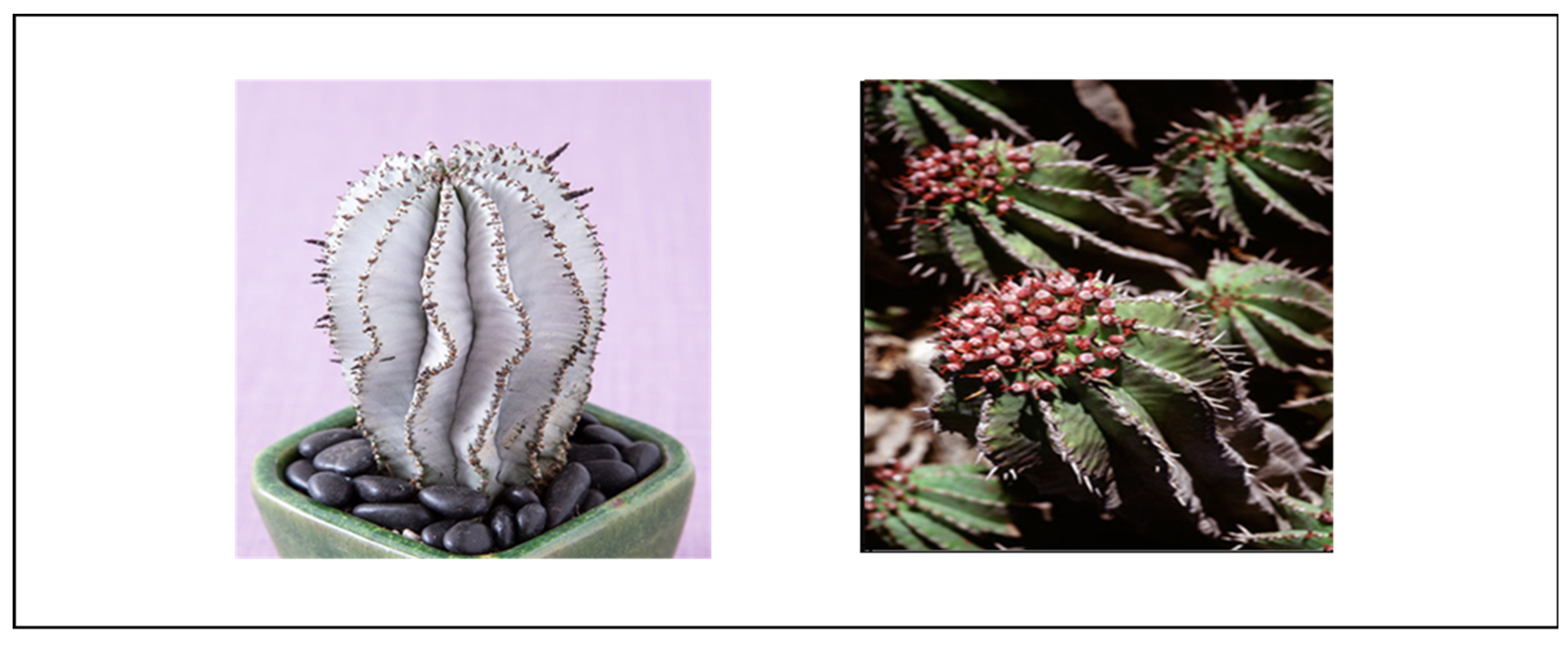

4.1.11. Euphorbia bupleurifolia

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.12. Euphorbia polygona

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.13. Euphorbia arabica

Phytochemistry

Toxicity

4.1.14. Euphorbia ferox

4.1.15. Euphorbia stellata

4.2. Pharmacological Activities

4.2.1. Flavonoids

4.2.2. Alkaloids

4.2.3. Saponins

4.2.4. Tannins

4.2.5. Glycosides

4.2.6. Anthraquinones

4.2.7. Terpenoids

4.2.7.1. Triterpenoids

4.2.8. Phytosterols

4.2.9. Other terpenoids

4.2.10. Phenolic Compounds

4.2.11. Fatty Acids

4.2.12. Miscellaneous

4.3. In Silico Evaluation of Selected Phytochemicals

4.3.1. Cell Line Cytotoxicity Tendency of Selected Compounds

4.3.2. Physicochemical and Drug-Like Properties

4.3.3. ADMET Properties of Top Compounds

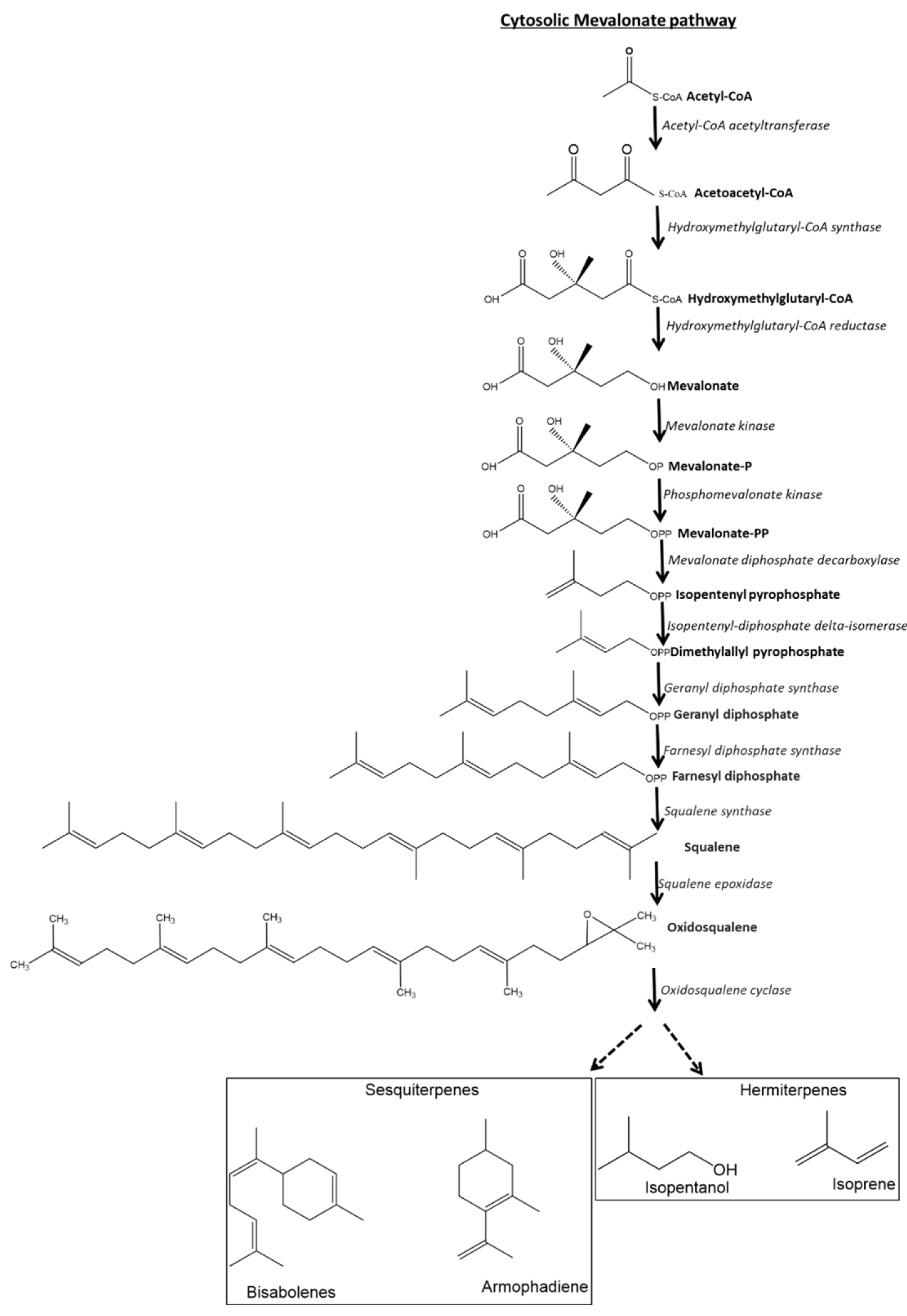

4.3.4. Biosynthesis of Tepernoid Class

5. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bijekar, S. R.; Gayatri, M. C. Ethanomedicinal Properties of Euphorbiaceae Family—A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Phytomedicine 2014, 6, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov, M.; Maksimova, V.; Koleva Gudeva, L. Review of the anticancer and cytotoxic activity of some species from genus Euphorbia. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2019, 84, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedapo, A. A.; Saba, A. B.; Dina, O. A.; Oladejo, G. M. A. Effects of dexamethasone on the infectivity of Trypanosoma vivax Y486 and the haematological changes in Nigerian domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus). Vet. Arhiv 2004, 74, 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, J.; Quirós, L. M.; Castañón, S. Purification and Partial Characterization of a Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from the Latex of Euphorbia Trigona Miller with Cytotoxic Activity toward Human Cancer Cell Lines. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancur-Galvis, L. A.; Morales, G. E.; Forero, J. E.; Roldan, J. Cytotoxic and antiviral activities of Colombian medicinal plant extracts of the Euphorbia genus. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2002, 97, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwine, T. J.; Damme, V. P. Why Do Euphorbiaceae Tick as Medicinal Plants? A Review of Euphorbiaceae Family and Its Medicinal Features. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fürstenberger, G.; Hecker, E. On the Active Principles of the Spurge Family (Euphorbiaceae) XI. The Skin Irritant and Tumor Promoting Diterpene Esters of Euphorbia tirucalli L. Originating from South Africa. Z. Naturforsch. C 1985, 40, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataluna, P.; Rates, S. M. K. The traditional use of the latex from Euphorbia tirucalli Linnaeus (Euphorbiaceae) in the treatment of cancer in South Brazil. In II WOCMAP congress medicinal and aromatic plants, part 2: pharmacognosy, pharmacology, phytomedicine, toxicology 1997, 501, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavundza, E. J.; Street, R.; Baijnath, H. A Review of the Ethnomedicinal, Pharmacology, Cytotoxicity, and Phytochemistry of the Genus Euphorbia in Southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 144, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; et al. Wearable health devices in health care: narrative systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 8, e18907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunin, A. A.; Dubovskaja, V. I.; Rudik, A. V.; Pogodin, P. V.; Druzhilovskiy, D. S.; Gloriozova, T. A.; Poroikov, V. V. CLC-Pred: A Freely Available Web-Service for In Silico Prediction of Human Cell Line Cytotoxicity for Drug-Like Compounds. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0191838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness, and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, D. E. V.; Blundell, T. L.; Ascher, D. B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetunji, J. A.; Ogunyemi, O. M.; Gyebi, G. A.; Adewumi, A. E.; Olaiya, C. O. Atomistic Simulations Suggest Dietary Flavonoids from Beta Vulgaris (Beet) as Promising Inhibitors of Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme and 2-Alpha-Adrenergic Receptors in Hypertension. Bioinform. Adv. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunyemi, O. M.; Gyebi, G. A.; Ibrahim, I. M.; Esan, A. M.; Olaiya, C. O.; Soliman, M. M.; Batiha, G. E.-S. Identification of Promising Multi-Targeting Inhibitors of Obesity from Vernonia Amygdalina through Computational Analysis. Mol. Divers. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Seki, H. Toxic Diterpenes from Euphorbia trigona (Saiunkaku: An Indoor Foliage Plant in Japan). Agric. Biol. Chem. 1989, 53, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashikkar, N.; Begde, D.; Bundale, S.; Mashitha, P.; Rudra, J.; Upadhyay, A. Evaluation of the Immunomodulatory Properties of Euphorbia trigona—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Inst. Pharm. Life Sci. 2012, 2, 88–105. [Google Scholar]

- Marathe, K.; Nashikkar, N.; Bundale, S.; Upadhyay, A. Analysis of Quorum Quenching Potential of Euphorbia trigona Mill. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 10, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, N. A.; da Silva, J. A. T.; Bari, M. A. Preservation of Indigenous Knowledge Regarding Important and Endangered Medicinal Plants in Rajshahi District of Bangladesh. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 5, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouquet, A. J. Natural products as an alternative remedy. 24th ed. Royal Botanic Garden Kew 1969, 166 -179. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242213547_Acute_effect_of_administration_of_ethanol_extracts_of_Ficus_exasperata_vahl_on_kidney_function_in_albino_rats.

- Lynn, K. R.; Clevette-Radford, N. A. Four serine proteases from the latex of Euphorbia tirucalli. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1985, 63, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luseba, D.; Van der Merwe, D. Ethnoveterinary medicine practices among Tsonga speaking people of South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2006, 73, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gildenhuys, S. The three most abundant tree Euphorbia species of the Transvaal (South Africa). Euphorbia World 2006, 2, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherei, M. M.; Islam, W. T.; El-Dine, R. S.; El-Toumy, S. A.; Ahmed, S. R. Phytochemical investigation of the cytotoxic latex of Euphorbia cooperi NE Br. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg, I.; Staugård, F. Traditional Medicinal Plants; Ipelegeng Publishers: 1989; Vol. 3.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874108004637.

- Gundidza, M.; Sorg, B.; Hecker, E. A skin irritant phorbol ester from Euphorbia cooperi NE Br. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 1992, 38, 444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Engi, H.; Vasas, A.; Redei, D.; Molnár, J.; Hohmann, J. New MDR Modulators and Apoptosis Inducers from Euphorbia Species. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 3451–3458. [Google Scholar]

- Morsi, S. R. A. Phytochemical and Biological Study of Certain Euphorbia Species Cultivated in Egypt. Doctoral Dissertation, Cairo University, 2015. http://erepository.cu.edu.eg/index.php/cutheses/article/view/5355.

- Carter, S. A preliminary classification of Euphorbia subgenus Euphorbia. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1994, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almehdar, H.; Abdallah, H. M.; Osman, A. M. M.; Abdel-Sattar, E. A. In vitro cytotoxic screening of selected Saudi medicinal plants. J. Nat. Med. 2012, 66, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M. M. A.; Al-Shamahy, H. A.; Alkhatib, B. Y.; Moharram, B. A. In vitro anti-leishmanial activity against cutaneous Leishmania parasites and preliminary phytochemical analysis of four Yemeni medicinal plants. Univ. J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 3, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyohara, H.; Ichino, C.; Kawamura, Y.; Nagai, T.; Sato, N.; Yamada, H.; et al. In vitro anti-influenza virus activity of a cardiotonic glycoside from Adenium obesum (Forssk. ). Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Sattar, E.; Maes, L.; Salama, M. M. In Vitro Activities of Plant Extracts from Saudi Arabia Against Malaria, Leishmaniasis, Sleeping Sickness, and Chagas Disease. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J. M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M. G. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa Being an Account of Their Medicinal and Other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal; Edn. 2, 1962. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19622704780.

- Baslas, R. K.; Gupta, N. C. Chemical constituents of the bark of Euphorbia tirucalli. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 1982. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Chemical%20constituents%20of%20the%20bark%20of%20<italic>Euphorbia</italic>%20tirucalli&publication_year=1982&author=R.K.%20Baslas&author=N.C.%20Gupta.

- Kajikawa, M.; Yamato, K. T.; Fukuzawa, H.; Sakai, Y.; Uchida, H.; Ohyama, K. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding β-amyrin synthase from petroleum plant Euphorbia tirucalli L. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivkumar, S. P. Ethnopharmacological Validation of Medicinal Plants Treating Skin Diseases in Hyderabad Karnataka Region. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/37479, 2015.

- Hargreaves, B. J. The spurges of Botswana. Botswana Notes Rec. 1991, 23, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, P. Studie van Euphorbia Tirucalli L.: Morfologie, Fysiologie, Teeltvoorwaarden; Doctoral Dissertation, Ghent University, 1989. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8551967. 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N.; Vishnoi, G.; Wal, A.; Wal, P. Medicinal value of Euphorbia tirucalli. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2013, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. E. Euphorbia Tirucalli L. (Euphorbiaceae). [Online] Available: http://pza.sanbi.org/Euphorbia-tirucalli. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- MacNeil, A.; Sumba, O. P.; Lutzke, M. L.; Moormann, A.; Rochford, R. Activation of the Epstein–Barr virus lytic cycle by the latex of the plant Euphorbia tirucalli. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 1566–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bosch, C.; Griffin, B. E.; Kazembe, P.; Dziweni, C.; Kadzamira, L. Are Plant Factors a Missing Link in the Evolution of Endemic Burkitt’s Lymphoma? Br. J. Cancer 1993, 68, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, M.; Yamato, K. T.; Fukuzawa, H.; Sakai, Y.; Uchida, H.; Ohyama, K. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding β-amyrin synthase from petroleum plant Euphorbia tirucalli L. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirio, L. G.; Hermano, M. L.; Fontanilla, M. Q. Antibacterial activity of medicinal plants from the Philippines. Pharm. Biol. 1998, 36, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Singh, P.; Singh, A. Toxicity of Euphorbia Tirucalli Plant against Freshwater Target and Non-Target Organisms. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Rezende, E. L.; Bozinovic, F.; Garland, T., Jr. Climatic Adaptation and the Evolution of Basal and Maximum Rates of Metabolism in Rodents. Evolution 2004, 58, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, J.; Chanda, S. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Phytochemical Analysis of Some Indian Medicinal Plants. Turk. J. Biol. 2007, 31, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Altamimi, M.; Jaradat, N.; Alham, S.; Al-Masri, M.; Bsharat, A.; Alsaleh, R.; Sabobeh, R. Antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of Euphorbia tirucalli L. bioRxiv 2019, 2019–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadares, M. C.; Carrucha, S. G.; Accorsi, W.; Queiroz, M. L. Euphorbia Tirucalli L. Modulates Myelopoiesis and Enhances the Resistance of Tumor-Bearing Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, V. A.; Rosa, M. N.; Miranda-Gonçalves, V.; Costa, A. M.; Tansini, A.; Evangelista, A. F. , et al. Euphol, a Tetracyclic Triterpene, from Euphorbia tirucalli Induces Autophagy and Sensitizes Temozolomide Cytotoxicity on Glioblastoma Cells. Invest. New Drugs 2019, 37, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, L. S.; Puziol, L. C.; Tosta, C. L.; Bittencourt, M. L.; Santa Ardisson, J.; et al. Analytical methods to access the chemical composition of an Euphorbia tirucalli anticancer latex from traditional Brazilian medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 237, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moteetee, A.; Moffett, R. O.; Seleteng-Kose, L. A Review of the Ethnobotany of the Basotho of Lesotho and the Free State Province of South Africa (South Sotho). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shale, T. L.; Stirk, W. A.; van Staden, J. Screening of Medicinal Plants Used in Lesotho for Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 67, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliehe, E. B. Medicinal plants and herbs of Lesotho. Mafeteng Development Project 1997. [CrossRef]

- Kose, L. S.; Moteetee, A.; Van Vuuren, S. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the Maseru district of Lesotho. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 170, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I. E.; Ndlovu, N.; Van Vuuren, S. F. The use of South African botanical species for the control of blood sugar. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 264, 113234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. CRC ethnobotany desk reference. CRC Press 2019. https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uTSoDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA2&dq=Johnson.

- Komoreng, L.; Thekisoe, O.; Lehasa, S.; Tiwani, T.; Mzizi, N.; Mokoena, N.; et al. An ethnobotanical survey of traditional medicinal plants used against lymphatic filariasis in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 111, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwani, T. Phytochemical Screening, Cytotoxicity, Antimicrobial and Anthelmintic Activity of Medical Plants Used in the Treatment of Lymphatic Filariasis in the Eastern Cape, South Africa; Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Free State, 2017.http://hdl.handle.net/11660/10002.

- Afolayan, A. J.; Grierson, D. S.; Mbeng, W. O. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the management of skin disorders among the Xhosa communities of the Amathole District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wyk, B. E.; Oudtshoorn, B. V.; Gericke, N. Medicinal Plants of South Africa; Briza, 1997.https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20006782435.

- Iwalewa, E. O.; McGaw, L. J.; Naidoo, V.; Eloff, J. N. Inflammation: The Foundation of Diseases and Disorders. A Review of Phytomedicines of South African Origin Used to Treat Pain and Inflammatory Conditions. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 2868–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, A.; Bahiru, A. Ethnoveterinary botanical survey of medicinal plants in Abergelle, Sekota and Lalibela districts of Amhara region, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 213, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mampa, S. T. M.; Mashele, S. S.; Sekhoacha, M. P. Applications of Chromatographic Techniques for Fingerprinting of Toxic and Non-toxic Euphorbia Species. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 23, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, F. J. The irritant toxins of Blue Euphorbia (Euphorbia coerulescens Haw.). Toxicon 1978, 16, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, N. A. Diversity of medicinal plants used in the treatment of skin diseases in Tabuk region, Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2017, 11, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shanwani, M. A. A. Al-nibatat al-mustakhdima fi al-tibb al-sha’abi al-Saudi [Plants used in Saudi folk medicine]. General Directorate of Research Grants Program, KACST, Riyadh 1996. scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Plants+Used+in+Saudi+Folk+Medicine&author=Al-Shanwani,+M.&.

- Abdel-Fattah, M. R. The Chemical Constituents and Economic Plants of the Euphorbiaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1987, 94, 293–326. [Google Scholar]

- Anjaneyulu, V.; Rao, G. S.; Connolly, J. D. Occurrence of 24-epimers of cycloart-25-ene-3β, 24-diols in the stems of Euphorbia trigona. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 1610–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P. E.; Nishimura, H.; Otvos, J. W.; Calvin, M. Plant Crops as a Source of Fuel and Hydrocarbon-Like Materials. Science 1977, 198, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popplewell, W. L.; Marais, E. A.; Brand, L.; Harvey, B. H.; Davies-Coleman, M. T. Euphorbias of South Africa: Two New Phorbol Esters from Euphorbia bothae. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2010, 63, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Rédei, D.; Forgo, P.; Hohmann, J. New Tigliane Diterpenes from Euphorbia grandicornis. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, F. J.; Kinghorn, A. D. A comparative phytochemical study of the diterpenes of some species of the genera Euphorbia and Elaeophorbia (Euphorbiaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1977, 74, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C. G.; Appel, M. H.; Coutinho, D. S.; Soares, I. P.; Fischer, S.; de Oliveira, B. C.; de Souza, L. M. Consumption of Latex from Euphorbia tirucalli L. Promotes a Reduction of Tumor Growth and Cachexia, and Immunomodulation in Walker 256 Tumor-Bearing Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 255, 112722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M. W.; Lin, A. S.; Wu, D. C.; Wang, S. S.; Chang, F. R.; Wu, Y. C.; Huang, Y. B. Euphol from Euphorbia tirucalli Selectively Inhibits Human Gastric Cancer Cell Growth through the Induction of ERK1/2-Mediated Apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 4333–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C.; Shen, C.; Yi, H.-M.; Chen, T.-H.; Hsueh, M.-L.; Lin, C.; Don, M. Euphorbiane: A Novel Triterpenoid with an Unprecedented Skeleton from Euphorbia tirucalli. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2012, 60, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, R. C.; da Silva, K. A. B. S.; Bento, A. F.; Marcon, R.; Paszcuk, A. F.; Meotti, F. C.; et al. Euphol, a tetracyclic triterpene produces antinociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain: The involvement of cannabinoid system. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Yokoyama, K. I.; Namba, O.; Okuda, T. Tannins and Related Polyphenols of Euphorbiaceous Plants. VII. Tirucallins A, B and Euphorbin F, Monomeric and Dimeric Ellagitannins from Euphorbia Tirucalli L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. Q.; Malik, A. A new macrocyclic diterpene ester from the latex of Euphorbia tirucalli. J. Nat. Prod. 1990, 53, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. Q.; Ahmed, Z.; Kazmi, N. U. H.; Malik, A.; Afza, N. The structure and absolute configuration of cyclotirucanenol, a new triterpene from Euphorbia tirucalli Linn. Z. Naturforsch. B 1988, 43, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. Q.; Rasheed, T.; Kazmi, S. N. U. H.; Ahmed, Z.; Malik, A. Cycloeuphordenol, a new triterpene from Euphorbia tirucalli. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2279–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Najam-ul-Hussain Kazmi; Malik, A. Further triterpenes from the stem bark of Euphorbia tirucalli. Planta Med. 1987, 53, 577–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Kazmi, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Malik, A. Euphorcinol: A new pentacyclic triterpene from Euphorbia tirucalli. Planta Med. 1989, 55, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, N.; Khan, A. Q.; Malik, A. A Taraxerane Type Triterpene from Euphorbia tirucalli. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1193–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslas, R. K.; Gupta, N. C. Constituents with potential effective agents from the latex of some Euphorbia species. Herba Hung. 1984. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Constituents%20with%20potential%20effective%20agents%20from%20the%20latex%20of%20some%20Euphorbia%20species&publication_year=1984&author=R.K.%20Baslas&author=N.C.%20Gupta.

- Yamamoto, Y.; Mizuguchi, R.; Yamada, Y. Chemical Constituents of Cultured Cells of Euphorbia Tirucalli and E. Millii. Plant Cell Rep. 1981, 1, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesboer, D. D.; Mahlberg, P. G. The effect of medium modification and selected precursors on sterol production by short-term callus cultures of Euphorbia tirucalli. J. Nat. Prod. 1979, 42, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P. E.; Nishimura, H.; Liang, Y.; Calvin, M. Steroids from Euphorbia and Other Latex-Bearing Plants. Phytochemistry 1979, 18, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, A. D. Characterization of an irritant 4-deoxyphorbol diester from Euphorbia tirucalli. J. Nat. Prod. 1979, 42, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürstenberger, G.; Hecker, E. New highly irritant Euphorbia factors from latex of Euphorbia tirucalli L. Experientia 1977, 33, 986–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. K.; Mahadevan, V. Chemical examination of the stems of Euphorbia tirucalli. Indian J. Pharm. 1967, 29, 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ponsinet, G.; Ourisson, G. Chemotaxonomic Studies in the Family Euphorbiaceae III: Distribution of Triterpenes in the Latexes of Euphorbia. Phytochemistry 1968, 7, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Sattar, E.; Abou-Hussein, D.; Petereit, F. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Euphorbia ammak growing in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacogn. Res. 2015, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlengwa, S. S. Isolation and characterisation of bioactive compounds from Antidesma venosum E. Mey. ex Tul. and Euphorbia cooperi NE Br. ex A. Berger. [Doctoral Dissertation] 2018, University of KwaZulu-Natal. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac. 1041. [Google Scholar]

- El-Toumy, S. A.; Salib, J. Y.; El-Kashak, W. A.; Marty, C.; Bedoux, G.; Bourgougnon, N. Antiviral effect of polyphenol rich plant extracts on herpes simplex virus type 1. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2018, 7, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwendt, M.; Becker, E. Tumor promoting compounds from Euphorbia triangularis: mono-and diesters of 12-desoxy-phorbol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 10, 3509–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hawary, S. S.; Mohammed, R.; Tawfike, A. F.; Lithy, N. M.; AbouZid, S. F.; Amin, M. N.; et al. Cytotoxic activity and metabolic profiling of fifteen Euphorbia Species. Metabolites 2020, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshara, O. A. A. Phytochemical Screening for Leaves, Cortex and Pith of the Cactus Euphorbia trigona L. [Doctoral Dissertation] 2014, University of Gezira.

- Kgosiemang, I. K.; Lefojane, R.; Direko, P.; Madlanga, Z.; Mashele, S.; Sekhoacha, M. Green synthesis of magnesium and cobalt oxide nanoparticles using Euphorbia tirucalli: Characterization and potential application for breast cancer inhibition. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2020, 50, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, L. E. S. Evaluation of commonly used medicinal plants of Maseru District in Lesotho for their ethnobotanical uses, antimicrobial properties and phytochemical compositions. [Doctoral Dissertation] 2017, University of Johannesburg (South Africa). https://hdl.handle.net/10210/243109.

- Silva, V. A.; Rosa, M. N.; Miranda-Gonçalves, V.; Costa, A. M.; Tansini, A.; Evangelista, A. F. , et al. Euphol, a Tetracyclic Triterpene, from Euphorbia tirucalli Induces Autophagy and Sensitizes Temozolomide Cytotoxicity on Glioblastoma Cells. Invest. New Drugs 2019, 37, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, K.; Akihisa, T.; Yoshida, Z. Y.; Takido, M. Inhibitory Effect of Euphol, a Triterpene Alcohol from the Roots of Euphorbia Kansui, on Tumor Promotion by 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-Acetate in Two-Stage Carcinogenesis in Mouse Skin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2000, 52, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heliawati, L.; Kurnia, D.; Apriyanti, E.; Adriansyah, P. N. A.; Ndruru, S. T. C. L. Natural Cycloartane Triterpenoids from Corypha utan Lamk. with Anticancer Activity towards P388 Cell Lines and their Predicted Interaction with FLT3. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2023, 26, 001–011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé-Abarca, L. F.; Gođevac, D.; Kim, M. S.; Hwang, G. S.; Park, S. C.; Jang, Y. P.; et al. The Instantaneous Multi-Pronged Defense System of Latex against General Plant Enemies. bioRxiv 2020, 2020–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawale, J. A.; Patel, J. R.; Kori, M. L. Antioxidant Properties of Cycloartenol Isolated from Euphorbia neriifolia Leaves. Indian J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Li, X.; Yang, A.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Cycloartenol Exerts Antiproliferative Effects on Glioma U87 Cells via Induction of Cell Cycle Arrest and p38 MAPK-Mediated Apoptosis. J. BUON 2018, 23, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. L.; Luo, Z. L.; Shi, H. W.; Zhang, L. X.; Ma, X. J. Research Advance of Functional Plant Pharmaceutical Cycloartenol about Pharmacological and Physiological Activity. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2017, 42, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare, S.; Ghaedi, M.; Heiling, S.; Asadollahi, M.; Baldwin, I. T.; Jassbi, A. R. Phytochemical Investigation on Euphorbia Macrostegia (Persian Wood Spurge). Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barla, A.; Birman, H.; Kültür, Ş.; Öksüz, S. Secondary metabolites from Euphorbia helioscopia and their vasodepressor activity. Turk. J. Chem. 2006, 30, 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. M.; Xu, H. G.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. J.; Sun, P. H.; Wu, X. M. , et al. Betulinic Acid and Its Derivatives as Potential Antitumor Agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35, 1127–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Kakkar, P. Lupeol prevents acetaminophen-induced in vivo hepatotoxicity by altering the Bax/Bcl-2 and oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial signaling cascade. Life Sci. 2012, 90, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgati, T. F.; Pereira, G. R.; Brandão, G. C.; Oliveira, A. B. D. Synthesis of triazol derivatives of lupeol with potential antimalarial activity. Orbital: Electron. J. Chem. 2012, 4, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, H. R.; Saleem, M. Beneficial Health Effects of Lupeol Triterpene: A Review of Preclinical Studies. Life Sci. 2011, 88, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M. B.; Sarachine, M. J. Biological Activities of Lupeol. Int. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 3, 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y. J.; Nam, N. H.; Kim, Y.; Bae, K. H.; Ahn, B. Z. Antiangiogenic Activity of Lupeol from Bombax Ceiba. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhahar, V.; Kumar, S. A.; Mythili, Y.; Varalakshmi, P. Remedial Effect of Lupeol and Its Ester Derivative on Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Oxidative and Inflammatory Stresses. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Gu, D.; Zeng, H. Antitumor Effects of Beta-Amyrin in Hep-G2 Liver Carcinoma Cells Are Mediated via Apoptosis Induction, Cell Cycle Disruption and Activation of JNK and P38 Signaling Pathways. J. BUON 2018, 23, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, K. W.; Huang, A. M.; Tu, H. Y.; Lee, L. Y.; Wu, C. C.; Hour, T. C.; et al. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory triterpenoid and phloroglucinol from guttiferaceous plants inhibit growth and induced apoptosis in human NTUB1 cells through a ROS-dependent mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, K.; Javaid, A.; Ahmad, E.; Athar, M. Antifungal compounds from Melia azedarach leaves for management of Ascochyta rabiei, the cause of chickpea blight. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, M. F.; Cheng, Y. D.; Shen, C. R.; Cherng, J. Y. A Molecular Pharmacology Study into the Anti-inflammatory Actions of Euphorbia hirta L. on the LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cells through Selective iNOS Protein Inhibition. J. Nat. Med. 2010, 64, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. B.; Yadav, D. K.; Maurya, R.; Srivastava, A. K. Antihyperglycaemic Activity of α-Amyrin Acetate in Rats and db/db Mice. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Monem, A. R.; Abdel-Sattar, E.; Harraz, F. M.; Petereit, F. Chemical Investigation of Euphorbia schimperi C. Presl. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2008. Available online: https://acgpubs.org/RNP/2008/Volume%202/Issue%201/RNP_0807_34.pdf.

- Johann, S.; Soldi, C.; Lyon, J. P.; Pizzolatti, M. G.; Resende, M. A. Antifungal activity of the amyrin derivatives and in vitro inhibition of Candida albicans adhesion to human epithelial cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M. M.; Apan, T. O. R.; Lazcano, M. E.; Bye, R. Anti-Inflammatory Active Compounds from the n-Hexane Extract of Euphorbia Hirta. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. /: (3–4), 103–105. https, 4754. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F. S.; Oliveira, P. J.; Duarte, M. F. Oleanolic, Ursolic, and Betulinic Acids as Food Supplements or Pharmaceutical Agents for Type 2 Diabetes: Promise or Illusion? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 2991–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, J. B.; Yazan, L. S.; Tor, Y. S.; Wibowo, A.; Ismail, N.; How, C. W.; et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by betulinic acid-rich fraction from Dillenia suffruticosa root in MCF-7 cells involved p53/p21 and mitochondrial signalling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damle, A. A.; Pawar, Y. P.; Narkar, A. A. Anticancer Activity of Betulinic Acid on MCF-7 Tumors in Nude Mice. 2013.

- Esposito, F.; Sanna, C.; Del Vecchio, C.; Cannas, V.; Venditti, A.; Corona, A.; et al. Hypericum hircinum L. components as new single-molecule inhibitors of both HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-associated DNA polymerase and ribonuclease H activities. Pathog. Dis. 2013, 68, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens-Talcott, S. U.; Noratto, G. D.; Li, X.; Angel-Morales, G.; Bertoldi, M. C.; Safe, S. Betulinic Acid Decreases ER-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo: Role of Sp Transcription Factors and microRNA-27a: ZBTB10. Mol. Carcinog. 2013, 52, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Prakash, O. Enzymes inhibition and antidiabetic effect of isolated constituents from Dillenia indica. Biomed Res. Int. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Alakurtti, S.; Mäkelä, T.; Koskimies, S.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J. Pharmacological properties of the ubiquitous natural product betulin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, C.; Chen, C. H. Betulinic acid derivatives as HIV-1 antivirals. Trends Mol. Med. 2005, 11, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P.; Scior, T.; Didier, B.; Hibert, M.; Berthon, J. Y. Ethnopharmacology and bioinformatic combination for leads discovery: application to phospholipase A2 inhibitors. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selzer, E.; Pimentel, E.; Wacheck, V.; Schlegel, W.; Pehamberger, H.; Jansen, B.; Kodym, R. Effects of Betulinic Acid Alone and in Combination with Irradiation in Human Melanoma Cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000, 114, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rahman, U.; Ali, S.; Khan, I.; Khan, M. A.; Arif, S. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Taraxerol Acetate. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 24, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, U. U.; Shah, J.; Khan, M. A.; Shah, M. R.; Khan, I. Molecular Docking of Taraxerol Acetate as a New COX Inhibitor. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Shi, H. L.; Ji, G.; Xie, J. Q. Effects of Taraxerol and Taraxerol Acetate on Cell Cycle and Apoptosis of Human Gastric Epithelial Cell Line AGS. J. Chin. Integr. Med. 2011, 9, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Biswas, K.; Ghosh, A.; Haldar, P. A pentacyclic triterpenoid possessing anti-inflammatory activity from the fruits of Dregea volubilis. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2009, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sahu, P. M.; Sharma, M. K. Anti-inflammatory and Antimicrobial Activities of Triterpenoids from Strobilanthes callosus Nees. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takasaki, M.; Konoshima, T.; Tokuda, K.; Masuda, K.; Arai, Y.; Shiojima, K.; Ageta, H. Anti-Carcinogenic Activity of Taraxacum Plant. II. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 22, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, S. Effect of β-sitosterol on the expression of HPV E6 and p53 in cervical carcinoma cells. Contemp. Oncol. (Pozn) 2015, 19, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmal, S. A.; Pal, S. C.; Mandal, S. C.; Patil, A. N. Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of β-Sitosterol Isolated from Nyctanthes arbortristis Leaves. Inflammopharmacology 2012, 20, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizou, S.; Lekakis, I.; Chrousos, G. P.; Moutsatsou, P. β-Sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fiky, F.; Asres, K.; Gibbons, S.; Hammoda, H.; Badr, J.; Umer, S. Phytochemical and antimicrobial investigation of latex from Euphorbia abyssinica Gmel. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Arche, A.; Saenz, M. T.; Arroyo, M.; De la Puerta, R.; Garcia, M. D. Topical anti-inflammatory effect of tirucallol, a triterpene isolated from Euphorbia lactea latex. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihisa, T.; Ogihara, J.; Kato, J.; Yasukawa, K.; Ukiya, M.; Yamanouchi, S.; Oishi, K. Inhibitory effects of triterpenoids and sterols on human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase. Lipids 2001, 36, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, P. Y.; Panchal, S. S. Euphorbia tirucalli L.: Review on morphology, medicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 7, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Shiraishi, A.; Hada, T.; Hirose, K.; Hamashima, H.; Shimada, J. The antibacterial effects of terpene alcohols on Staphylococcus aureus and their mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 237, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, A. P.; Abdjan, M. I.; Aminah, N. S.; Fahmi, M. Z.; Siswanto, I.; Kristanti, A. N.; Takaya, Y. 3,4,3′-Tri-O-Methylellagic Acid as an Anticancer Agent: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29884–29891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. K.; Xu, J. K.; Zhang, X. Q.; Yao, X. S.; Ye, W. C. Chemical Constituents with Antibacterial Activity from Euphorbia Sororia. Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 22, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, C. M.; Price, S. L.; Shirk, E. N.; Cunha, R. D.; Pianowski, L. F.; Clements, J. E.; Tanuri, A.; Gama, L. Dual role of novel ingenol derivatives from Euphorbia tirucalli in HIV replication: inhibition of de novo infection and activation of viral LTR. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wei, S. L.; Gao, K. Chemical constituents and antibacterial activities of compounds from Lentinus edodes. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hammed, M.; Bello, I. A.; Olajide, M.; Adedotun, I. O.; Afolabi, T. I.; Ibironke, A. A.; et al. Exploration of bioactive compounds from Mangifera indica (Mango) as probable inhibitors of thymidylate synthase and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-Κb) in colorectal cancer management. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Krstić, G.; Anđelković, B.; Choi, Y. H.; Vajs, V.; Stević, T.; Tešević, V.; Gođevac, D. Metabolic changes in Euphorbia palustris latex after fungal infection. Phytochemistry 2016, 131, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anju, V.; Rameshkumar, K. B. Phytochemical investigation of Euphorbia trigona. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunnusi, T. A.; Oso, B. A.; Dosumu, O. O. Isolation and Antibacterial Activity of Triterpenes from Euphorbia kamerunica Pax. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, G. F. D.; Soares, D. C. F.; Mussel, W. D. N.; Pompeu, N. F. E.; Silva, G. D. D. F.; Vieira Filho, S. A.; Duarte, L. P. Pentacyclic Triterpenes from Branches of Maytenus robusta and In Vitro Cytotoxic Property against 4T1 Cancer Cells. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fa, J.; Li, B. Apoptosis Induction of Epifriedelinol on Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosath, S.; Ott, H. H.; Hecker, E. Irritant Principles of the Spurge Family (Euphorbiaceae) XIII. Oligocyclic and Macrocyclic Diterpene Esters from Latices of Some Euphorbia Species Utilized as Source Plants of Honey. J. Nat. Prod. 1988, 51, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ourhzif, E. M.; Ricelli, A.; Stagni, V.; Cirigliano, A.; Rinaldi, T.; Bouissane, L. , et al. Antifungal and Cytotoxic Activity of Diterpenes and Bisnorsesquiterpenoides from the Latex of Euphorbia resinifera Berg. Molecules 2022, 27, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, C.; Blumberg, P. M. Regulation of cell apoptosis by protein kinase C δ. Apoptosis 2003, 8, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, S.; Sorg, B.; Hecker, E. Structure Activity Relations of Polyfunctional Diterpenes of the Tigliane Type, VI1. Planta Med. 1984, 50, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Xiong, G. L.; Jing, Y.; Xiao, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y. F. , et al. The Protein Kinase C Agonist Prostratin Induces Differentiation of Human Myeloid Leukemia Cells and Enhances Cellular Differentiation by Chemotherapeutic Agents. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, D.; Amara, S.; Johnson, T. L.; Tiriveedhi, V. Potential anticancer effect of prostratin through SIK3 inhibition. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3252–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J. Y.; Rédei, D.; Hohmann, J.; Wu, C. C. 12-Deoxyphorbol Esters Induce Growth Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Lung Cancer A549 Cells via Activation of PKC-δ/PKD/ERK Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, M.; Suttajit, M.; Suguri, H.; Endo, Y.; Shudo, K.; Wongchai; et al. A new tumor promoter from the seed oil of Jatropha curcas L., an intramolecular diester of 12-deoxy-16-hydroxyphorbol. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 5800–5804. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, R. C.; Claudino, R. F.; Bento, A. F.; Marcon, R.; Schmidt, E. C.; Bouzon, Z. L.; et al. Preventive and therapeutic euphol treatment attenuates experimental colitis in mice. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. S.; Lin, Y. M.; Haruna, M.; Pan, D. J.; Shingu, T.; Chen, Y. P.; et al. Antitumor Agents, 119. Kansuiphorins A and B, Two Novel Antileukemic Diterpene Esters from Euphorbia kansui. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatope, M. O.; Zeng, L.; Ohayaga, J. E.; Shi, G.; McLaughlin, J. L. Selectively cytotoxic diterpenes from Euphorbia poisonii. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, A. M.; Hammouda, F. M.; El-Missiry, M. M.; Radwan, H. M.; Evans, F. J. Biologically Active Diterpene Esters from Euphorbia peplus. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 1605–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, A. D.; Kinghorn, A. Cocarcinogenic irritant Euphorbiaceae. Toxic Plants. Columbia University Press, New York 1979, 137-160.

- Driedger, P. E.; Blumberg, P. M. Structure–Activity Relationships in Chick Embryo Fibroblasts for Phorbol-Related Diterpene Esters Showing Anomalous Activities In Vivo. Cancer Res. 1980, 40, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Priya, C. L.; Rao, K. V. B. A Review of Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile of Euphorbia tirucalli. Pharmacologyonline 2011, 2, 384–390. [Google Scholar]

- Adolf, W.; Hecker, E. On the Active Principles of the Spurge Family, X. Skin Irritants, Cocarcinogens, and Cryptic Cocarcinogens from the Latex of the Manchineel Tree. J. Nat. Prod. 1984, 47, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Monem, A. R.; Abdelrahman, E. H. New abietane diterpenes from Euphorbia pseudocactus berger (Euphorbiaceae) and their antimicrobial activity. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016, 12 (Suppl 3), S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wal, A.; Wal, P.; Gupta, N.; Vishnoi, G.; Srivastava, R. S. Medicinal Value of Euphorbia tirucalli. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ovesná, Z.; Vachálková, A.; Horváthová, K. Taraxasterol and β-Sitosterol: New Natural Compounds with Chemoprotective/Chemopreventive Effects. Neoplasma 2004, 51, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, B.; Singh, K. P.; Kumar, A. Ethno-Medicinal, Phytochemical, and Antimicrobial Studies of Euphorbia tirucalli L. J. Phytol. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, C.; Sathish, S. A Review on Euphorbia neriifolia Plant. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Res. 2017, 3, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. R.; Elsherei, M. M.; Salah El Dine, R.; Eltomy, S. Phytoconstituents, Hepatoprotective, and Antioxidant Activities of Euphorbia cooperi NE Br. Egypt. J. Chem. 2019, 62 Pt 2, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herawati, N.; Firdaus, F. 3,3′-Di-O-Methylellagic Acid, an Antioxidant Phenolic Compound from Sonneratia alba Bark. 2013, 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Vigbedor, B. Y.; Akoto, C. O.; Neglo, D. Isolation and Characterization of 3,3′-Di-O-Methyl Ellagic Acid from the Root Bark of Afzelia africana and Its Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities. Sci. Afr. 2022, 17, e01332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljubiri, S. M.; Mahmoud, K.; Mahgoub, S. A.; Almansour, A. I.; Shaker, K. H. Bioactive Compounds from Euphorbia schimperiana with Cytotoxic and Antibacterial Activities. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Han, L.; Bo, X.; Huang, C.; Ni, L. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of the acetone extracts of root of Euphorbia hylonoma and its ellagic acid derivatives. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 5584–5589. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, T.; Yokoyama, K. I.; Namba, O.; Okuda, T. Tannins and Related Polyphenols of Euphorbiaceous Plants. VII. Tirucallins A, B, and Euphorbin F, Monomeric and Dimeric Ellagitannins from Euphorbia tirucalli L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazoir, N.; Benharref, A.; Bailén, M.; Reina, M.; González-Coloma, A.; Martínez-Díaz, R. A. Antileishmanial and Antitrypanosomal Activity of Triterpene Derivatives from Latex of Two Euphorbia Species. Z. Naturforsch. C. [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, O. E.; Pretorius, E. Asthma, Euphorbia hirta and its anti-inflammatory properties: News and views. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2007, 103, 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vázquez, M.; Apan, T. O. R.; Lazcano, M. E.; Bye, R. Antiinflammatory Active Compounds from the n-Hexane Extract of Euphorbia hirta. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 1999, 43, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, A.; Hossain, M. J.; Kuddus, M. R.; Rashid, M. A.; Zahan, M. S.; Mitra, S. . Naina Mohamed, I. Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Toxicology, and Pharmacological Properties of Euphorbia neriifolia Linn. Against Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilabi, J.; Upadhyay, R. R. Adenoma Formation by Ingenol 3, 5, 20-Triacetate. Cancer Lett. 1983, 18, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsue, M.; Mori, Y.; Nagase, S.; Sugiyama, Y.; Hirano, R.; Ogai, K.; et al. Measuring the Antimicrobial Activity of Lauric Acid against Various Bacteria in Human Gut Microbiota Using a New Method. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1528–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J. Glutinol inhibits the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liang, C.; Kim, J. H.; Lee, Y. M.; Hyun, J. H.; Kang, H. K.; et al. Triterpene Compounds Isolated from Acer mandshuricum and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1528–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Jafri, M.; Kar, A.; Meheta, B. K. Thyroid Inhibitory, Antiperoxidative and Hypoglycemic Effects of Stigmasterol Isolated from Butea monosperma. Fitoterapia 2009, 80, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinala, M. M.; Siwe-Noundoub, X.; Augustyna, W.; Tembu, V. J. Metabolomics and phytochemicals of Euphorbia rowlandii with anticancer properties. The 2nd African Traditional and Natural Product Medicine Conference. Poster 6. 2022, University of Limpopo.

- Ahmed, S. R. Phytochemical and Biological Study of Certain Euphorbia Species Cultivated in Egypt. [Doctoral Theses] 2015. [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Yazdiniapour, Z.; Ghanadian, M.; Zolfaghari, B.; Lanzotti, V.; Mirsafaee, V. Obtusifoliol related steroids from Euphorbia sogdiana with cell growth inhibitory activity and apoptotic effects on breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB231). Steroids 2016, 115, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, B. , et al. Corilagin Inhibits Breast Cancer Growth via Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Apoptosis and Autophagy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 3795–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. Z.; Chen, L. H.; Liu, S. S.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, G. H.; Gu, Y.; Ming, Y. L. Bioguided Fraction and Isolation of the Antitumor Components from Phyllanthus niruri L. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 9729275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, G.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Tong, Q. Corilagin Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation by Inducing G2/M Phase Arrest. Cell Biol. Int. 2013, 37, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Pan, R.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. HPLC profile of longan (cv. Shixia) pericarp-sourced phenolics and their antioxidant and cytotoxic effects. Molecules 2019, 24, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, H.; Burmeister, A.; Trun, W.; Radtke, O. A.; Kiderlen, A. F.; Ito, H.; et al. Tannins and related compounds induce nitric oxide synthase and cytokines gene expressions in Leishmania major-infected macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 6470–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Y.; He, X. M.; Sun, J.; Li, C. B.; Li, L.; Sheng, J. F. , et al. Polyphenols and Alkaloids in Byproducts of Longan Fruits (Dimocarpus Longan Lour.) and Their Bioactivities. Molecules 2019, 24, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Cheng, D.; Tao, J. Y.; Zhang, S. L.; Pang, R.; Guo, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects of corilagin in a rat model of acute cholestasis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J. T.; Lin, T. C.; Hsu, F. L. Antihypertensive effect of corilagin in the rat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995, 73, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sultan, S. I.; Hussein, Y. A. Acute toxicity of Euphorbia heliscopia in rats. Pak. J. Nutr. 2006, 5, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, A. F. M. The Chemical Constituents and Economic Plants of the Euphorbiaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, P. L. Euphorbia Tirucalli for High Biomass Production. Combating Desertification with Plants 2001, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogg, G.; Mattes, E.; Rothenburger, J.; Hertkorn, N.; Achatz, S.; Sandermann Jr, H. Tumor Promoting Diterpenes from Euphorbia Leuconeura L. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlamovitz, G. Z.; Gupta, M.; Diaz, J. A. A Case of Acute Keratoconjunctivitis from Exposure to Latex of Euphorbia tirucalli (Pencil Cactus). J. Emerg. Med. 2009, 36, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytwala, S.; Günther, F.; Melzig, M. F. Lysozyme- and Chitinase Activity in Latex Bearing Plants of Genus Euphorbia–A Contribution to Plant Defense Mechanism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 95, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsalla, A.; Görick, C.; Melzig, M. F. Proteolytic Activity in Latex of the Genus Euphorbia – A Chemotaxonomic Marker? Pharmazie 2010, 65, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, K. R.; Clevette-Radford, N. A. Lectins from latices of Euphorbia and Elaeophorbia species. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H. J.; Gulumian, M. Pharmacopoeia of traditional medicine in Venda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1984, 12, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J. M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M. G. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa Being an Account of Their Medicinal and Other Uses, Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Effects and Toxicology in Man and Animal; Edn. 2, 1962.

- Waczuk, E. P.; Kamdem, J. P.; Abolaji, A. O.; Meinerz, D. F.; Caeran Bueno, D.; do Nascimento Gonzaga, T. K. S. , et al. Euphorbia Tirucalli Aqueous Extract Induces Cytotoxicity, Genotoxicity and Changes in Antioxidant Gene Expression in Human Leukocytes. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 4, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V. A. O.; Rosa, M. N.; Tansini, A.; Oliveira, R. J.; Martinho, O.; Lima, J. P. . Reis, R. M. In Vitro Screening of Cytotoxic Activity of Euphol from Euphorbia tirucalli on a Large Panel of Human Cancer-Derived Cell Lines. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letícia, M.; Victório, C. P.; Costa, H. B.; Romão, W.; Kuster, R. M.; Gattass, C. R. Antiproliferative activity of extracts of Euphorbia tirucalli L (Euphorbiaceae) from three regions of Brazil. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, R.; Furtado Teixeira, L. D.; Cristina, T. Analysis of in vitro activity of high dilutions of Euphorbia tirucalli L. in human melanoma cells. Int. J. High Dilution Res. 2021, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, A. M.; Hamed, M. B.; Salama, W. H.; Ali, M. M.; Fahmy, A. S.; Mohamed, S. A. Ficus carica, Ficus sycomorus and Euphorbia tirucalli latex extracts: Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, B.; Vuong, Q. V.; Chalmers, A. C.; Goldsmith, C. D.; Bowyer, M. C.; Scarlett, C. J. Phytochemical, Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties of Euphorbia tirucalli Methanolic and Aqueous Extracts. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillarmod, A. J. Flora of Lesotho (Basutoland); Cramer: Lehre, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Mbhele, N. Ethnobotanical Survey, Pharmacological Evaluation and Chemical Characterization of Selected Medicinal Plants Used in South Africa in the Management of Wounds. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Johannesburg (South Africa), 2021.

- Moteetee, A.; Moffett, R. O.; Seleteng-Kose, L. A Review of the Ethnobotany of the Basotho of Lesotho and the Free State Province of South Africa (South Sotho). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Li, L.; Huo, C.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Study on Natural Medicinal Chemistry and New Drug Development. Zhongcaoyao 2010, 41, 1583–1589, https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20113119759. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q. W.; Su, X. H.; Kiyota, H. Chemical and Pharmacological Research of the Plants in Genus Euphorbia. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4295–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, C. J.; Jing, S. X.; Luo, S. H.; Li, S. H. Chemical profile and defensive function of the latex of Euphorbia peplus. Phytochemistry 2017, 136, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, M.; Sadhan, K. R.; Jnanojjal, C. Euphorbia tirucalli L.: a review on its potential pharmacological use in chronic diseases. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 6, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M. M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapas, A. R.; Sakarkar, D. M.; Kakde, R. B. Flavonoids as Nutraceuticals: A Review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2008, 7, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hameed, E. S. S.; Bazaid, S. A.; Salman, M. S. Characterization of the phytochemical constituents of Taif rose and its antioxidant and anticancer activities. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Z. P.; Ni, G.; Liu, Y. F.; Li, L.; Shi, G. R.; Wang, X.; et al. Heliosterpenoids A and B, Two Novel Jatrophane-Derived Diterpenoids with a 5/6/4/6 Ring System from Euphorbia helioscopia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. G.; Jia, L. N.; Shen, Y.; Ohmura, A.; Kitanaka, S. Inhibitory Effects of Constituents from Euphorbia Lunulata on Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Cells and Nitric Oxide Production in RAW264.7 Cells. Molecules 2011, 16, 8305–8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleggiante, V.; De Santis, S.; Cavalcanti, E.; Scarano, A.; De Benedictis, M.; Serino, G.; et al. Dendritic cells modulate iron homeostasis and inflammatory abilities following quercetin exposure. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choene, M.; Motadi, L. Validation of the antiproliferative effects of Euphorbia tirucalli extracts in breast cancer cell lines. Mol. Biol. 2016, 50, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigler, D. S. Alkaloids Derived from Anthranilic Acid. Plant Second. Metab. 1998, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapingu, M. C.; Mbwambo, Z. H.; Moshi, M. J.; Magadula, J. J. Brine shrimp lethality of a glutarimide alkaloid from Croton sylvaticus Hochst. East Cent. Afr. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudiar, T.; Hichem, L.; Khalfallah, A.; Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z.; Brouard, I.; Bruneau, C. A new alkaloid and flavonoids from the aerial parts of Euphorbia guyoniana. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1934578X1000500109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndam, L. M.; Mih, A. M.; Tening, A. S.; Fongod, A. G. N.; Temenu, N. A.; Fujii, Y. Phytochemical Analysis, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Euphorbia golondrina L.C. Wheeler (Euphorbiaceae Juss.): An Unexplored Medicinal Herb Reported from Cameroon. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirkapu, M. J.; Yananli, H. R. Opium Alkaloids. Bioactive compounds in nutraceutical and functional food for good human health. 2020.

- Molyneux, R. J.; Nash, R. J.; Asano, N. Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives; Vol. 11, Pelletier, S. W., Ed.; 1996. [CrossRef]

- Bigoniya, P.; Rana, A. C. Radioprotective and in-vitro cytotoxic sapogenin from Euphorbia neriifolia (Euphorbiaceae) leaf. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2009, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannet, S. B.; Hymery, N.; Bourgou, S.; Jdey, A.; Lachaal, M.; Magné, C.; Ksouri, R. Antioxidant and selective anticancer activities of two Euphorbia species in human acute myeloid leukemia. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glauert, A. M.; Dingle, J. T.; Lucy, J. A. Action of saponin on biological cell membranes. Nature 1962, 196, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Izzi, A.; Benie, T.; Thieulant, M. L.; Le Men-Olivier, L.; Duval, J. Stimulation of LH release from cultured pituitary cells by saponins of Petersianthus macrocarpus: A permeabilizing effect. Planta Med. 1992, 58, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Kerem, Z.; Makkar, H. P.; Becker, K. The biological action of saponins in animal systems: a review. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H.; Bachran, D.; Panjideh, H.; Schellmann, N.; Weng, A.; Melzig, M. F.; et al. Saponins as tool for improved targeted tumor therapies. Curr. Drug Targets 2009, 10, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidi, G.; Correia, M.; Chauffert, B.; Beltramo, J. L.; Wagner, H.; Lacaille-Dubois, M. A. Saponins-mediated potentiation of cisplatin accumulation and cytotoxicity in human colon cancer cells. Planta Med. 2002, 68, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W. W. G.; Bu, X.; Philips, D.; Yan, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; et al. Rh2, a compound extracted from ginseng, hypersensitizes multidrug-resistant tumor cells to chemotherapy. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2004, 82, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Yi, Y. H.; Wang, Z. Z.; Tang, H. F.; Li, Y. Q.; Lin, H. W. A Cytotoxic Triterpene Saponin from the Root Bark of Aralia Dasyphylla. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1030–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattorusso, E.; Lanzotti, V.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Di Rosa, M.; Ianaro, A. Cytotoxic saponins from bulbs of Allium porrum L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3455–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Q. L.; Tezuka, Y.; Banskota, A. H.; Tran, Q. K.; Saiki, I.; Kadota, S. New Spirostanol Steroids and Steroidal Saponins from Roots and Rhizomes of Dracaena Angustifolia and Their Antiproliferative Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokosuka, A.; Mimaki, Y.; Sashida, Y. Spirostanol Saponins from the Rhizomes of Tacca Chantrieri and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Phytochemistry 2002, 61, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traore, F.; Faure, R.; Ollivier, E.; Gasquet, M.; Azas, N.; Debrauwer, L. , et al. Structure and Antiprotozoal Activity of Triterpenoid Saponins from Glinus Oppositifolius. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzi, M.; Lanzotti, V.; Ranalli, G.; De Marino, S.; Zollo, F. Antimicrobial furostanol saponins from the seeds of Capsicum annuum L. var. acuminatum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4310–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, M.; Maksimova, V.; Koleva Gudeva, L. Review of the anticancer and cytotoxic activity of some species from genus Euphorbia. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2019, 84, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga-Corral, M.; Otero, P.; Cassani, L.; Echave, J.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Carpena, M.; et al. Traditional applications of tannin rich extracts supported by scientific data: Chemical composition, bioavailability and bioaccessibility. Foods 2021, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K. T.; Wong, T. Y.; Wei, C. I.; Huang, Y. W.; Lin, Y. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 421–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarowicz, R.; Troszynska, A.; Barylko-Pikielna, N.; Shahidi, F. Polyphenolics extracts from legume seeds: correlations between total antioxidant activity, total phenolics content, tannins content and astringency. J. Food Lipids 2004, 11, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. L.; Yung, R. W. H.; Tsang, D. N. C.; Que, T. L.; Ho, M.; Seto; et al. Increasing resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones: results of a Hong Kong multicentre study in 2000. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzini, P.; Arapitsas, P.; Goretti, M.; Branda, E.; Turchetti, B.; Pinelli, P.; et al. Antimicrobial and antiviral activity of hydrolysable tannins. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleckar, V.; Kubikova, K.; Rehakova, Z.; Kuca, K.; Jun, D.; Jahodar, L.; Opletal, L. Condensed and hydrolysable tannins as antioxidants influencing the health. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinsembu, K. C. Coronaviruses and nature’s pharmacy for the relief of coronavirus disease 2019. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2020, 30, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mshvildadze, V.; Legault, J.; Lavoie, S.; Gauthier, C.; Pichette, A. Anticancer Diarylheptanoid Glycosides from the Inner Bark of Betula papyrifera. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tang, J. S.; Hu, M. J.; Liu, J.; Chen, H. F.; Gao, H.; et al. Antiproliferative cardiac glycosides from the latex of Antiaris toxicaria. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A. N.; Kour, D.; Rana, K. L.; Yadav, N.; Singh, B.; Chauhan, V. S. , et al. Metabolic Engineering to Synthetic Biology of Secondary Metabolites Production. New Future Dev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J. R. Natural Products: The Secondary Metabolites; Royal Society of Chemistry: 2003, 17. [CrossRef]

- Berdy, J. Bioactive microbial metabolites. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemboi, D.; Peter, X.; Langat, M.; Tembu, J. A review of the ethnomedicinal uses, biological activities, and triterpenoids of Euphorbia species. Molecules 2020, 25, 4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenheim, J. H. Higher plant terpenoids: a phytocentric overview of their ecological roles. J. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 20, 1223–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Pichersky, E.; Gershenzon, J. Biochemistry of Plant Volatiles. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, L.; Meng, K.; Tian, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z. , et al. Triterpenoids Manipulate a Broad Range of Virus-Host Fusion via Wrapping the HR2 Domain Prevalent in Viral Envelopes. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M. Lupeol, a Novel Anti-inflammatory and Anti-cancer Dietary Triterpene. Cancer Lett. 2009, 285, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erazo, S.; Rocco, G.; Zaldivar, M.; Delporte, C.; Backhouse, N.; Castro, C.; Belmonte, E.; Monache, F. D.; García, R. Active Metabolites from Dunalia spinosa Resinous Exudates. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2008, 63, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.; Iqbal Azhar, M. Two triterpenes lupanone and lupeol, isolated and identified from Tamarindus indica. Linn. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 20, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda, A. L. P.; Silva, J. R.; Rezende, C. M.; Neves, J. S.; Parrini, S. C.; Pinheiro, M. L.; et al. Antiinflammatory and analgesic activities of the latex containing triterpenes from Himatanthus sucuuba. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguemfo, E. L.; Dimo, T.; Dongmo, A. B.; Azebaze, A. G. B.; Alaoui, K.; Asongalem, A. E.; et al. Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Some Isolated Constituents from the Stem Bark of Allanblackia monticola Staner L. C. (Guttiferae). Inflammopharmacology 2009, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Sharma, A. K.; Sharma, M. C.; Dobhal, M. P.; Gupta, R. S. Evaluation of antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of lupeol in experimental hyperglycaemia. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhahar, V.; Kumar, S. A.; Mythili, Y.; Varalakshmi, P. Remedial Effect of Lupeol and Its Ester Derivative on Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Oxidative and Inflammatory Stresses. Nutr. Res. 2007, 27, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C. Y.; Cornelio, K. B. Triterpenes from Euphorbia hirta and Their Cytotoxicity. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 11, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriakhi, K.; Uadia, P. O.; Shaheen, F.; Jahan, H.; Ibeji, C. U.; Iqbal, C. M. Isolation, Characterization, and Hepatoprotective Properties of Betulinic Acid and Ricinine from Tetracarpidium conophorum Seeds (Euphorbiaceae). J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbeunkeu, A. B. D.; Azebaze, A. G. B.; Tala, M. F.; Teinkela, J. E. M.; Noundou, X. S.; Krause, R. W. M.; et al. Three New Pentacyclic Triterpenoids from Twigs of Manniophyton fulvum (Euphorbiaceae). Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzouzi, J. T.; Soh, P. N.; Ramos, S.; Toto, P.; Cavé, A.; Hemez, J.; Benoit-Vical, F. Samvisterin, a new natural antiplasmodial betulin derivative from Uapaca paludosa (Euphorbiaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhoacha, M.; Campbell, W.; Smith, P. In vitro and in vivo antimalarial activity of DCM extract of Agathosma betulina. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 6, 323–324. [Google Scholar]

- Tamamura, H.; Kobayakawa, T.; Ohashi, N. Springer Briefs in Pharmaceutical Science and Drug Development. Springer: Singapore, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P. K.; Saha, K.; Das, J.; Pal, M.; Saha, B. P. Studies on the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Rhizomes of Nelumbo nucifera. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 367–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigoniya, P.; Rana, A. A comprehensive phyto-pharmacological review of Euphorbia neriifolia Linn. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2008, 2, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedula, V. P.; Schilling, J. K.; Miller, J. S.; Andriantsiferana, R.; Rasamison, V. E.; Kingston, D. G. New cytotoxic terpenoids from the wood of Vepris punctata from the Madagascar Rainforest. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Brodie, P.; Miller, J. S.; Birkinshaw, C.; Rakotondrafara, A.; Andriantsiferana, R.; et al. Antiproliferative compounds of Helmiopsis sphaerocarpa from the Madagascar rainforest. Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 23, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csupor-Löffler, B.; Hajdú, Z.; Zupkó, I.; Molnár, J.; Forgo, P.; Vasas, A.; et al. Antiproliferative constituents of the roots of Conyza canadensis. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B. S.; Na, M. K.; Oh, S. R.; Ahn, K. S.; Jeong, G. S.; Li, G.; et al. New Furofuran and Butyrolactone Lignans with Antioxidant Activity from the Stem Bark of Styrax japonica. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1980–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, K. N.; Sujatha, S.; Muthusamy, V. S.; Anand, S.; Nithya, N.; Velmurugan, D.; Balakrishnan, A.; Lakshmi, B. S. 3β-Taraxerol of Mangifera indica, a PI3K-Dependent Dual Activator of Glucose Transport and Glycogen Synthesis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2010, 1800, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carréu, J. P. M. Bioactive terpenoids from Euphorbia pubescens: isolation and derivatization. [Masters Dissertation] 2020, University of Lisbon.

- Anju, V.; Singh, A.; Shilpa, G.; Kumar, B.; Priya, S.; Sabulal, B.; Rameshkumar, K. B. Terpenes and biological activities of Euphorbia tortilis. Lett. Org. Chem. 2018, 15, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneyulu, V.; Satyanarayana, P.; Viswanadham, K. N.; Jyothi, V. G.; Rao, K. N.; Radhika, P. Triterpenoids from Mangifera indica. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilahur, G.; Ben-Aicha, S.; Diaz-Riera, E.; Badimon, L.; Padró, T. Phytosterols and Inflammation. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 6724–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezza, T.; Canet, F.; de Marañón, A. M.; Bañuls, C.; Rocha, M.; Víctor, V. M. Phytosterols: Nutritional Health Players in the Management of Obesity and Its Related Disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazłowska, K.; Lin, H. T. V.; Chang, S. H.; Tsai, G. J. In vitro and in vivo anticancer effects of sterol fraction from red algae Porphyra dentata. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangsamaksin, T.; Chaithongyot, S.; Wootthichairangsan, C.; Hanchaina, R.; Tangshewinsirikul, C.; Svasti, J. Lupeol and stigmasterol suppress tumor angiogenesis and inhibit cholangiocarcinoma growth in mice via downregulation of tumor necrosis factor-α. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0189628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P. T.; Urones, J. G.; Marcos, I. S.; Basabe, P.; Cuadrado, M. S.; Moro, R. F. Triterpenes from Euphorbia broteri. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, S.; Gürek, F.; Lin, L. Z.; Gil, R. R.; Pezzuto, J. M.; Cordell, G. A. Aleppicatines A and B from Euphorbia aleppica. Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, S.; Ulubelen, A.; Barla, A.; Voelter, W. Terpenoids and Aromatic Compounds from Euphorbia heteradena. Turk. J. Chem. 2002, 26, 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, R. D. S.; de Jesus, B. D. S. M.; da Silva Luiz, S. R.; Viana, C. B.; Adao Malafaia, C. R.; Figueiredo, F. D. S.; Martins, R. C. C. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Natural Triterpenes—An Overview from 2006 to 2021. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 1459–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R.; Kasubuchi, K.; Kita, S.; Matsunaga, S. Obtusifoliol and Related Steroids from the Whole Herb of Euphorbia chamaesyce. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. “PubChem Compound Summary for CID 9932254, Glutinol.” PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Glutinol (accessed April 5, 2023).

- Chen, Y.; Li, J. Glutinol inhibits the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latansio de Oliveira, T.; Reder Custodio de Souza, A.; Dias Fontana, P.; Carvalho Carneiro, M.; Beltrame, F. L.; de Messias Reason, I. J.; Bavia, L. Bioactive secondary plant metabolites from Euphorbia umbellata (PAX) Bruyns (Euphorbiaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, T. L.; Munhoz, A. C. M.; Lemes, B. M.; Minozzo, B. R.; Nepel, A.; Barison, A.; et al. Antitumoral effect of Synadenium grantii Hook f. (Euphorbiaceae) latex. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M. W.; Lin, A. S.; Wu, D. C.; Wang, S. S.; Chang, F. R.; Wu, Y. C.; Huang, Y. B. Euphol from Euphorbia tirucalli selectively inhibits human gastric cancer cell growth through the induction of ERK1/2-mediated apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 4333–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. H.; Beniddir, M. A.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Nguyen, H. H.; Nguyen, D. P.; Mac, D. H.; et al. Further terpenoids from Euphorbia tirucalli. Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihisa, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Oinuma, H.; Kasahara, Y.; Yamanouchi, S.; Takido, M.; Tamura, T. Triterpene alcohols from the flowers of compositae and their anti-inflammatory effects. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. J.; Evans, F. J. Candletoxins A and B, 2 new aromatic esters of 12-deoxy-16-hydroxy-phorbol, from the irritant latex of Euphorbia poisonii Pax. Experientia 1977, 33, 1197–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, E. New toxic, irritant and cocarcinogenic diterpene esters from Euphorbiaceae and from Thymelaeaceae. Pure Appl. Chem. 1977, 49, 1423–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, K.; Kawazu, K.; Mitsui, T. Studies on a Piscicidal Constituent of Hura crepitans: Part II. Chemical Structure of Huratoxin. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1971, 35, 2113–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalai, C.; Wiriyachitra, P.; Sorg, B.; Hecker, E. Medicinal plants of Euphorbiaceae occurring and utilized in Thailand. V. Skin irritants of the daphnane and tigliane type in latex of Excoecaria bicolor and the uterotonic activity of the leaves of the tree. Phytother. Res. 1995, 9, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. H.; Baek, S. H.; Hwang, S. T.; Um, J. Y.; Ahn, K. S. Corilagin Exhibits Differential Anticancer Effects through the Modulation of STAT3/5 and MAPKs in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 2449–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wei, K. Constituents of tannins from Euphorbia prostrata Ait. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi = Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi = China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 1992, 17, 225–226. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. H.; Vasquez, Y.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I. A.; Khan, S. I. Constituents from Terminalia Species Increase PPARα and PPARγ Levels and Stimulate Glucose Uptake without Enhancing Adipocyte Differentiation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 149, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latté, K. P.; Kolodziej, H. Antifungal effects of hydrolysable tannins and related compounds on dermatophytes, mould fungi and yeasts. Z. Naturforsch. C 2000, 55, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notka, F.; Meier, G. R.; Wagner, R. Inhibition of Wild-Type Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor-Resistant Variants by Phyllanthus amarus. Antiviral Res. 2003, 58, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljubiri, S. M.; Elsalam, E. A.; Abd El Hady, F. K.; Radwan, M. O.; Almansour, A. I.; Shaker, K. H. In Vitro Acetylcholinesterase, Tyrosinase Inhibitory Potentials of Secondary Metabolites from Euphorbia schimperiana and Euphorbia balsamifera. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2023, 78, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y. H.; Yen, C. H.; Leu, Y. L. Chemical constituents from the aerial parts of Euphorbia formosana Hayata and their chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 88, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Cao, G.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B. , et al. Serum Metabolome and Gut Microbiome Alterations in Broiler Chickens Supplemented with Lauric Acid. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, I. B.; Baloch, M. K. Irritant and co-carcinogenic diterpene esters from the latex of Euphorbia cauducifolia L. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 12, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedei, N.; Lundberg, D. J.; Toth, A.; Welburn, P.; Garfield, S. H.; Blumberg, P. M. Characterization of the interaction of ingenol 3-angelate with protein kinase C. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 3243–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbourne, S. M.; Suhrbier, A.; Jones, B.; Cozzi, S. J.; Boyle, G. M.; Morris, M.; et al. Antitumor Activity of 3-Ingenyl Angelate: Plasma Membrane and Mitochondrial Disruption and Necrotic Cell Death. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2833–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampson, P.; Chahal, H.; Khanim, F.; Hayden, R.; Mulder, A.; Assi, L. K.; et al. PEP005, a selective small-molecule activator of protein kinase C, has potent antileukemic activity mediated via the delta isoform of PKC. Blood 2005, 106, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothias-Scaglia, L. F.; Pannecouque, C.; Renucci, F.; Delang, L.; Neyts, J.; Roussi, F.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Diterpene Esters on Chikungunya Virus and HIV Replication. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyebi, G.; Ogunyemi, O.; Ibrahim, I.; Afolabi, S.; Ojo, R.; Ejike, U.; Adebayo, J. Inhibitory Potentials of Phytocompounds from Ocimum Gratissimum against Anti-Apoptotic BCL-2 Proteins Associated with Cancer: An Integrated Computational Study. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 9, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C. A. Lead- and Drug-Like Compounds: The Rule-of-Five Revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. L. P-Glycoprotein Inhibition for Optimal Drug Delivery. Drug Target Insights 2013, 7, DTI.S12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. E. Role of ADME/PK in Drug Discovery, Safety Assessment, and Clinical Development. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry III; Chackalamannil, S., Rotella, D., Ward, S. E., Eds.; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Kratz, J. M.; Grienke, U.; Scheel, O.; Mann, S. A.; Rollinger, J. M. Natural Products Modulating the hERG Channel: Heartaches and Hope. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Botanical name Synonym in bold |

Vernacular name (E)= English; (S)= Sotho (Z)= Zulu; (X)= Xhosa; (A)=Afrikaans (N)= Ndebele (T)= Tsonga (Ts)= Tswana (V)= Venda |

Location | Growing condition | Traditional use |

Bioactive property | Toxicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Euphorbia trigona Euphorbia hermentiana Lem |

African milk tree (E) | West Africa, tropical Asia, India | Dry tropical forests and semiarid environment. Direct sunlight | Respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, gonorrhoea, tumors and warts, intestinal parasites, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis, inflammation, piles, constipation, epileptic attack. | Anticancer | Skin irritation | [16,17,18,19,20,21] |

|

Euphorbia cooperi E. cooperi var. cooperi E. cooperi var calidicola |

Candelabra Euphorbia (E), Umhlonhlo (N), Tshikondengala (V), Mokhoto (T) Mohlohlo (S) | South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal, Swaziland, North-West Province, Mpumalanga and Limpopo) Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana | Well-drained soil. Direct sunlight. | Sore stomach, bloatedness, paralysis, wound healing | Breast cancer inhibitor | Skin irritation, blindness, throat burning sensation | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Euphorbia ammak | African candelabra /Desert candelabra (E) | Saudi Arabia, Yemen peninsulaα | No data reported | No data reported | Anticancer Antileishmanial activity, (H1N1) influenza virus, MDCK cells, antiparasitic activity |

Skin and eye irritation. Normal melanocyte (HFB4). |

[29,30,31,32,33] |

|

Euphorbia tirucalli Euphorbia laro Drake |