Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Generalized Entropy Metric Approach

2. The Model

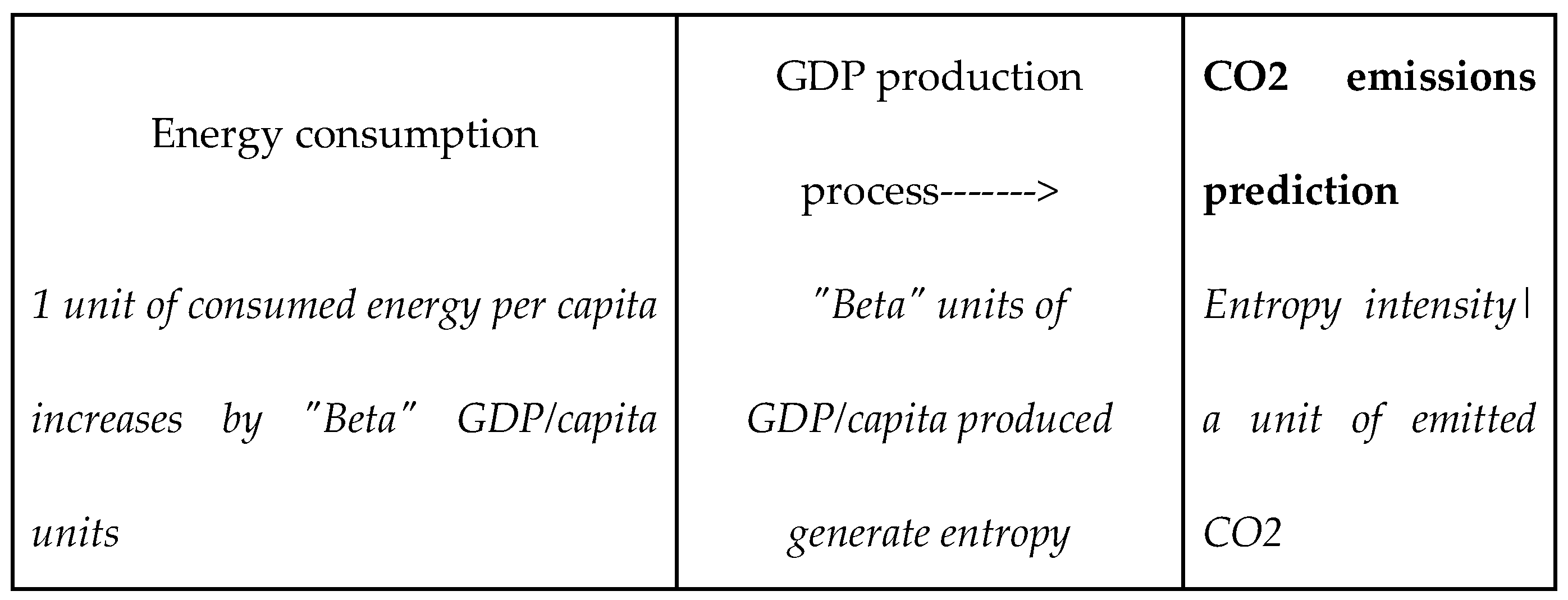

2.1. Energy, Economic Production and CO2 Emissions

2.2. The Power Law Based Entropy Model

3. Model Outputs and Discussion

3.1. Entropy-Based Model Outputs

3.2. Relationships between Entropy and CO2 Emissions

3.2. Limitations of the Study and Prospective Research Area

4. Concluding Remarks

References

- IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. 2006.

- Oda and al., et. The Open-source Data Inventory for Anthropogenic CO2, version 2016 (ODIAC2016). Earth System Science Data. 2018.

- Peters and Hertwich. ISO 14040 and 14044. Carbon Footprint of Nations. Environmental Science & Technology. 2009.

- Davis and Caldeira. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. PNAS. 2010.

- Wiedmann & Minx. A Definition of 'Carbon Footprint'. Ecological Economics Research Trends. 2008.

- Marland and al., et. Accounting for uncertainty in CO2 emissions. Nature Geoscience. 2009.

- Métayer and al., et. Uncertainty in spatially explicit CO2 emission models. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. 2012.

- Nordhaus. The DICE model: Background and structure of a dynamic integrated climate-economy model of the economics of global warming. 2013.

- Rolnick and al., et. Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning. arXiv:1906.05433. 2019.

- Wiedmann, T. and Minx, J. A Definition of Carbon Footprint. Ecological Economics Research Trends. 2008, Vol. 1, pp. 1-11.

- Majeau-Bettez, G. , Hawkins TR, TR and Strømman, AH. Life cycle environmental assessment of lithium-ion and nickel metal hydride batteries for plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicles. Environ Sci Technol. may 15, 2011, pp. 4548-54.

- Lenzen, M. Errors in Conventional and Input-Output—based Life—Cycle Inventories. Journal of Industrial Ecology. 4, 2000, pp. 127-148.

- Su, B.; Ang, B. Input–output analysis of CO2 emissions embodied in trade: The effects of spatial aggregation. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.P.; Hertwich, E.G. Post-Kyoto greenhouse gas inventories: production versus consumption. Clim. Chang. 2007, 86, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, Dawis. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. 107, Mars 8, 2010, Vol. 12, pp. 5687-5692.

- Ang,, B. W. Is the energy intensity a less useful indicator than the carbon factor in the study of climate change? Energy Policy. 27, 1999, Vol. 15, pp. 943-946.

- Rypdal,, Kristin and Wilfried, Winiwarter. Uncertainties in greenhouse gas emission inventories—evaluation, comparability and implications. Environmental Science & Policy. 4, 2001, Vols. 2-3, pp. 107-116.

- Acquaye, A.A.; Wiedmann, T.; Feng, K.; Crawford, R.H.; Barrett, J.; Kuylenstierna, J.; Duffy, A.P.; Koh, S.C.L.; McQueen-Mason, S. Identification of ‘Carbon Hot-Spots’ and Quantification of GHG Intensities in the Biodiesel Supply Chain Using Hybrid LCA and Structural Path Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 2471–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, R. Gurney,, et al. High Resolution Fossil Fuel Combustion CO2 Emission Fluxes for the United States 2009. Environmental Science & Technology. 43, 2009.

- Guan, and Dabo, et al.. The gigatonne gap in China’s carbon dioxide inventories. Nature Climate Change. 2, 2012, Vol. 9, pp. 672-675.

- Moss,, Richard H, et al.

- Tong,, C. J., et al. Microstructure characterization of Al x CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system with multiprincipal elements. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A,. 2005, Vol. 3, 36,, pp. 881-893.

- Georgescu-Roegen. The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. 1971.

- Ayres, R.U.; Warr, B. The Economic Growth Engine; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham Glos, United Kingdom, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Van Rysselberghe, P. Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1963, 110, 97C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M. , Niemes, H. and Stephan, G. Entropy, Environment, and Resources. 1987.

- Kümmel, R. The Second Law of Economics; Stern. 2011.

- The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics. Jakimowicz, Aleksander. 4, 2020, Entropy, Vol. 22, p. 452.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. 2021.

- Energy, aesthetics and knowledge in complex economic systems. Foster, John. 1, 2011, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. Volume 80, pp. 88-100.

- A Brief History of Energy Use in Human Societies. In: Revisiting the Energy-Development Link. SpringerBriefs in Economics. Springer, Cham. Bithas, K. and Kalimeris, P. 2016, Springer International Publishing.

- Blaug, Mark. Economic Theory in Retrospect (4th ed.). Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0521316446.

- Stigler, J. George. Essays in the History of Economics.. Chicago : University of Chicago Press., 1965.

- A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Solow, Robert. 56), Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 65-94. 19 February.

- Robert, M. Solow's Neoclassical Growth Model: An Influential Contribution to Economics. Edward C., C. Prescott. No. 1, s.l. : The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Mar., 1988, Vol. Vol. 90, pp. 7-12.

- ENDOCENOUS TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE. Romer, M. ENDOCENOUS TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE. Romer, M. Paul. Massachusetts : NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, 1989. Working Paper No. 3210.

- On the mechanics of economic development. Lucas, Lucas and Robert, E. s.l. : Journal of Monetary Economics, 1988, Vol. 22, pp. 3-42.

- Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth. Barro, RJ. Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogenous Growth. Barro, RJ. 1990, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, pp. 103-125.

- Rodrik, D. . One Economics Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth. Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Okrasa, W. , & Rozkrut, D.. The Time Use Data-based Measures of the Wellbeing Effect of Community Development: An Evaluative Approach. imsva91-ctp.trendmicro.com. [Online] Polish Institute of Statistics, 2018. https://imsva91-ctp.trendmicro.com:443/wis/clicktime/v1/query?url=https%3a%2f%2fnces.ed.gov%2fFCSM%2f2018%5fResear.

- Cierpial-Wolan, M. . The modelling of cross-border aspects of territorial development. Rzeszow : University of Rzeszow Publishing House, 2022.

- The relationship between energy consumption and economic growth: Evidence from non-Granger causality test. Faisal, Faisal, Turgut, Tursoy and Ercantan, Ozlem. s.l. : Procedia Computer Science, 2017, Vol. 120, pp. 671-675. ISSN 1877-0509.

- Economic Growth with Energy. Alam, M. Economic Growth with Energy. Alam, M. Shahid. Boston : MPRA Paper, Northeaster University, 2006.

- Causal Relationships between Energy Consumption and Economic Growth. Zhang, Zhixin and Ren, Xin. s.l. : Energy Procedia, 2011, Vol. 5, pp. 2065-2071. ISSN 1876-6102.

- The triangular relationship between energy consumption, trade openness and economic growth: new empirical evidence. Osei-Assibey, Bonsu and Wang, M. Y. 1, s.l. : Cogent Economics & Finance, 2022, Vol. 10. Article 2140520.

- Relationship between Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in European Countries: Evidence from Dynamic Panel Data Analysis. Topolewski, Łukasz. 12, s.l. : MDPI, 2021, Energies, Vol. 14. 3565.

- ENERGY–GDP RELATIONSHIP: A CAUSAL ANALYSIS FOR THE FIVE COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA. ASGHAR, Zahid. 1, s.l. : Applied Econometrics and International Development, 2008, Vol. 8.

- A survey of literature on energy consumption and economic growth. Sebabi, Geoffrey Mutumba, et al. s.l. : Energy Reports, 2021, Vol. 7, pp. 9150-9239.

- Grossman, G. and Krueger, A. Economic growth and the environment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1995, Vol. 110, pp. 353–77.

- Soumyananda, Dinda. Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis: A Survey. Ecological Economics. 2004, 49, pp. 431–455.

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve after 25 years. J. Bioeconomics 2017, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J. B. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, and output in France. [Online] 2007.

- Shahbaz, M.; Hye, Q.M.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Leitão, N.C. Economic growth, energy consumption, financial development, international trade and CO2 emissions in Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X. The Laws of Power in Economics and Finance. Washington : BER, 2008.

- Aggregate Fluctuations from Independent Sectoral Shocks: Self-organized Criticality in a Model of Production and Inventory Dynamics. Bak, et al. 1, s.l. : Ricerche Economiche, 1993, Vol. 47, pp. 3–30.

- Miziołek, T.; Filip, D. Market Concentration in the Polish Investment Fund Industry. Gospod. Nar. 2019, 300, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwanakare, S. Non-Extensive Entropy Econometrics for Low Frequency Series: National Accounts-Based Inverse Problems. Warsaw : De Gruyter Open Poland, 2018.

- Jakimowicz, A. The Material Entropy and the Fourth Law of Thermodynamics in the Evaluation of Energy Technologies of the Future. Energies 2023, 16, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4000-6351-2. [Google Scholar]

- Power Laws in Economics: An Introduction. Gabaix, Xavier. 1, s.l. : Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2016 (February), Vol. 30, pp. 185–206.

- Judge, George G., Miller, Douglas and Golan, Amos. Maximum Entropy Econometrics : Robust Estimation with Limited Data. s.l. : Chichester [England]: Wiley., 1996.

- Tsallis,, Constantino. Introduction to Nonextensive Statistical Mechanics, Approaching a Complex World. [ed.] Springer. NewYork : s.n., 09. 10.1007/978-0-387-85359-8. 20 January.

- A mathematical theory of evolution based on the conclusions of Dr. JC Willis FRS . Yule, G. U. no. A mathematical theory of evolution based on the conclusions of Dr. JC Willis FRS. Yule, G. U. no. 402–410, London : Royal Soc., , 1925, Phil. Trans.B, Vol. 213, pp. 21-87. 1 January.

- A Model of Income Distribution. Champernowne, D. G. A Model of Income Distribution. Champernowne, D. G. 1, s.l. : The Economic Journal, 1953, Vol. 63, pp. 318–351.

- On a class of skew distribution functions. Simon, H. A. On a class of skew distribution functions. Simon, H. A.. 3-4, s.l. : Biometrika, 1955, Vol. 42, pp. 425-440.

- Limit theorems for stochastic growth models. II. Kesten, H. Limit theorems for stochastic growth models. II. Kesten, H. 3, s.l. : Advances in Applied Probability, 1972, Vol. 4, pp. 393-428.

- Jessen, Anders Hedegaard and Mikosch, Thomas. Regularly Varying Functions. s.l. : Publications de l'Institut Mathématique, 2006. Vol. 80(94), 100, pp. 171-192.

- Bottazzi, G.; Cefis, E.; Dosi, G.; Secchi, A. Invariances and Diversities in the Patterns of Industrial Evolution: Some Evidence from Italian Manufacturing Industries. Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 29, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champernowne, D.G. A Model of Income Distribution. Econ. J. 1953, 63, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, (et al.) and Eugene, H. Power Law Scaling for a System of Interacting Units with Complex Internal Structure,. PHYS I CAL RE V I EW LETTERS,. , 1998. 16 February.

- Eurostat. Eurostat. [Online] EU, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ten00122/default/table?lang=en.

- Energy Efficiency Forecast as an Inverse Stochastic Problem: A Cross-Entropy Econometrics Approach. Bwanakare, S. s.l. Energy Efficiency Forecast as an Inverse Stochastic Problem: A Cross-Entropy Econometrics Approach. Bwanakare, S. s.l. : MDPI, 2023, Energies, Vol. 16.

- Moser, S. , Kainz, C. and Loy, C. Entropy as a measure for assessing the sustainability of production systems. Sustainability. 13, 2021, Vol. 4, 1761.

- Warr, B. and Ayres, R. U. Entropy, resources, and economic growth. Ecological Economics. 193, 2022, Vol. 107295.

- Feng, C. , et al. Exploring the entropy-emission nexus: Evidence from China's industrial sectors. Energy Economics. 109, 2022, Vol. 105992.

- Qin, Q. , Liu, Y. Energy Reports. 2021, 4769–4778. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, J. and Snäkin, J. P. Quantifying the relationship between energy consumption, CO2 emissions, and entropy metrics for chemical manufacturing processes. Journal of Cleaner Production,. 246, 2020, Vol. 119005.

- Casazza, M. and Manfren, M. The role of entropy in assessing the circularity of economic systems. Entropy. 24, 2022, Vol. 5, 600.

- Quesnay, Francois. Tableau Economique. London : MacMilian and Co and New York, 1894.

- Razzaqi, S.; Bilquees, F.; Sherbaz, S. .. Dynamic Relationship Between Energy and Economic Growth: Evidence from D8 Countries. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2022, 50, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KELSEY, JACK. How much do we know about the development impacts of energy infrastructure? Published on. Sustainable Energy for All,. [Online] MARCH 29, 2022. https://blogs.worldbank.org/energy/how-much-do-we-know-about-development-impacts-energy-infrastructure.

- Magazzino, C.; Schneider, N. The Causal Relationship between Primary Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in Israel: A Multivariate Approach. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 14, 417–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. and Tsallis, C. Nonextensive Entropy, Interdisciplinary Applications. New York, NY, USA : Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Nordhaus. The DICE model: Background and structure of a dynamic integrated climate-economy model of the economics of global warming. 2013.

- Stern, D. I. The role of energy in economic growth. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011.

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve after 25 years. J. Bioeconomics 2017, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soytas, U.; Sari, R. Energy consumption, economic growth, and carbon emissions: Challenges faced by an EU candidate member. 68, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicioglu and Ferda. An econometric study of CO2 emissions, energy consumption, income and foreign trade in Turkey. Energy Policy. 37, 09, Vol. 3, pp. 1156-1164. 20 March.

- A Brief History of Energy Use in Human Societies. In: Revisiting the Energy-Development Link. Springer Briefs in Economics. Springer, Cham. Bithas, K. and Kalimeris, P. 2016, Springer International Publishing.

| Country | Estimates | Model R^2 _equivalent |

Optimal entropy values |

|

| Beta | constant | |||

| Denmark | 5.443 | 1.335 | 0.876 | 0.435 |

| Belgium | 3.836 | 1 | 0.918 | 0.45 |

| Germany | 4.867 | 1.089 | 0.937 | 0.488 |

| Netherlands | 4.279 | 1.603 | 0.334 | 0.496 |

| Czechia | 2.963 | 0.872 | 0.955 | 0.52 |

| Ireland | 3.731 | 2.417 | 0.565 | 0.525 |

| France | 5.037 | 0.71 | 0.951 | 0.528 |

| Estonia | 2.204 | 0.832 | 0.943 | 0.552 |

| Poland | 3.065 | 0.742 | 0.982 | 0.552 |

| Bulgaria | 2.01 | 0.575 | 0.982 | 0.555 |

| countries | CO2\capita | Entropy intensity per a unit of CO2 per capita |

| Belgium | 9.949232 | 0.04523 |

| Bulgaria | 6.700354 | 0.082831 |

| Czechia | 11.26775 | 0.046149 |

| Denmark | 7.73826 | 0.056214 |

| Germany | 9.846759 | 0.049559 |

| Estonia | 14.65488 | 0.037667 |

| Ireland | 9.064644 | 0.057917 |

| France | 5.809483 | 0.090886 |

| Netherlands | 10.43629 | 0.047526 |

| Poland | 8.303462 | 0.066478 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).