Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What preference handling techniques have been used in the military UAV path planning literature?

- RQ2: For each of the identified methods: What are the advantages and disadvantages of using these methods?

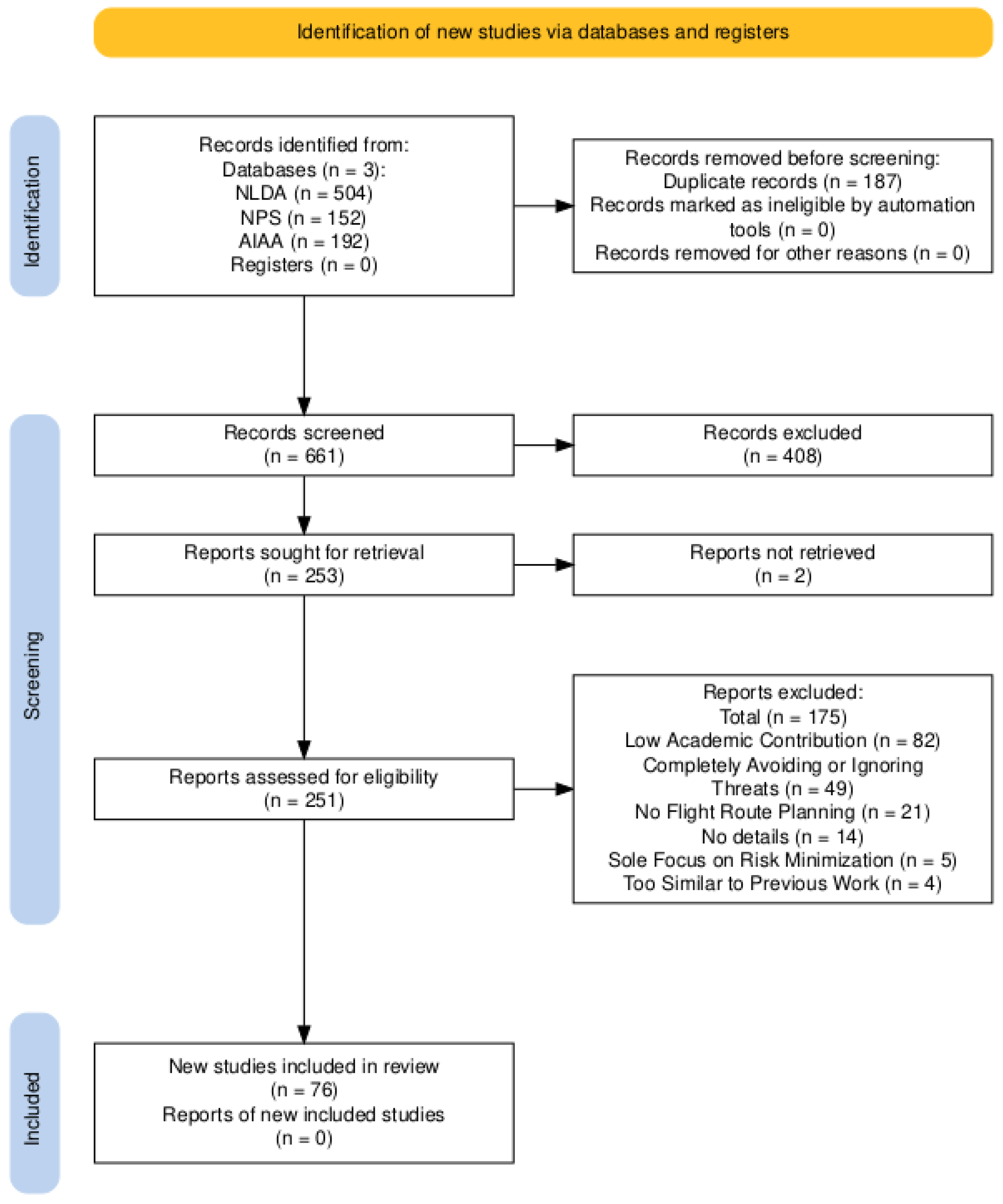

2. Methodology

- ("Route planning" OR "Path planning") AND (hostile OR threat) AND (radar OR missile)

3. Preference Handling in the UAV Route Planning Literature

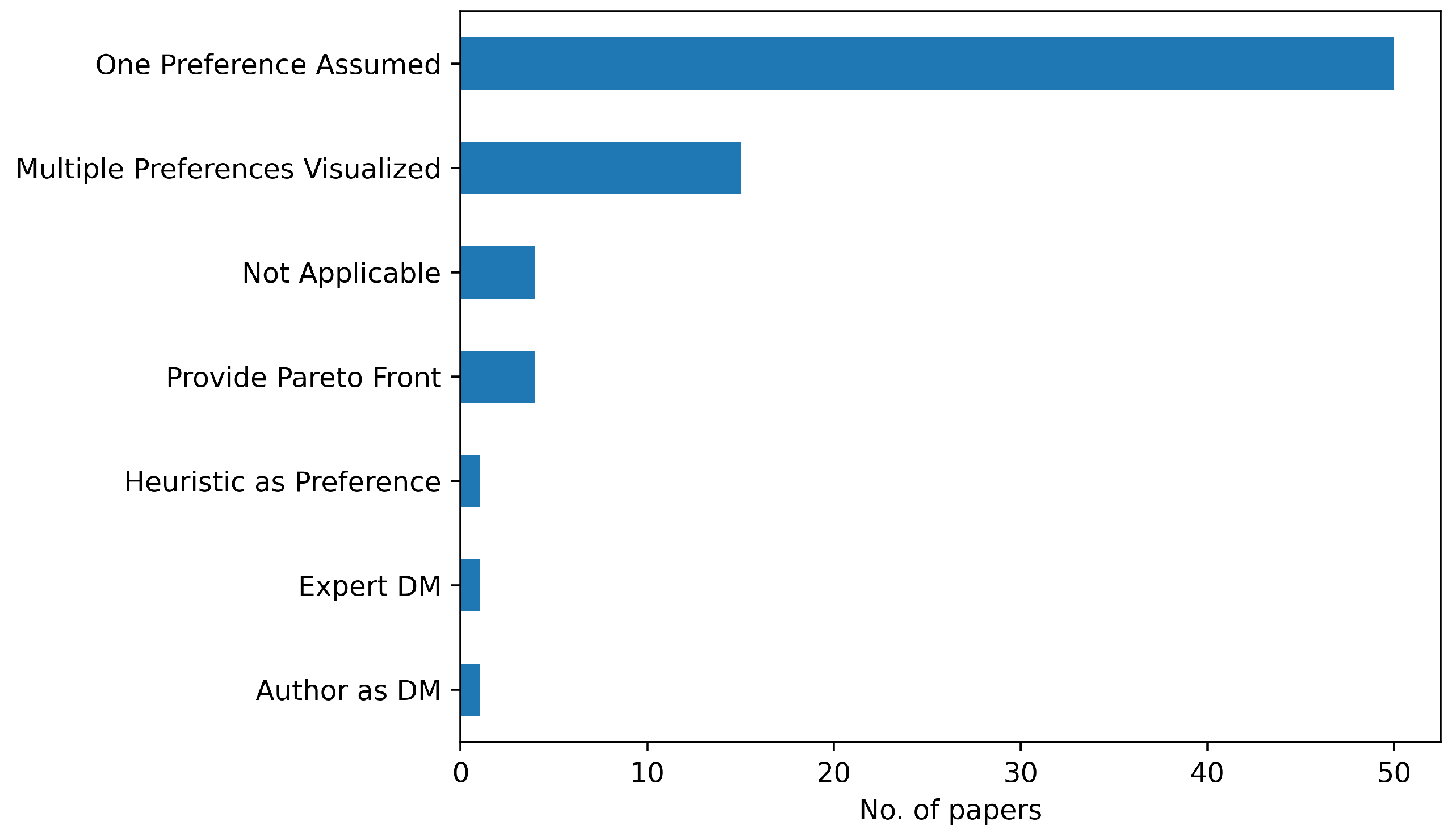

-

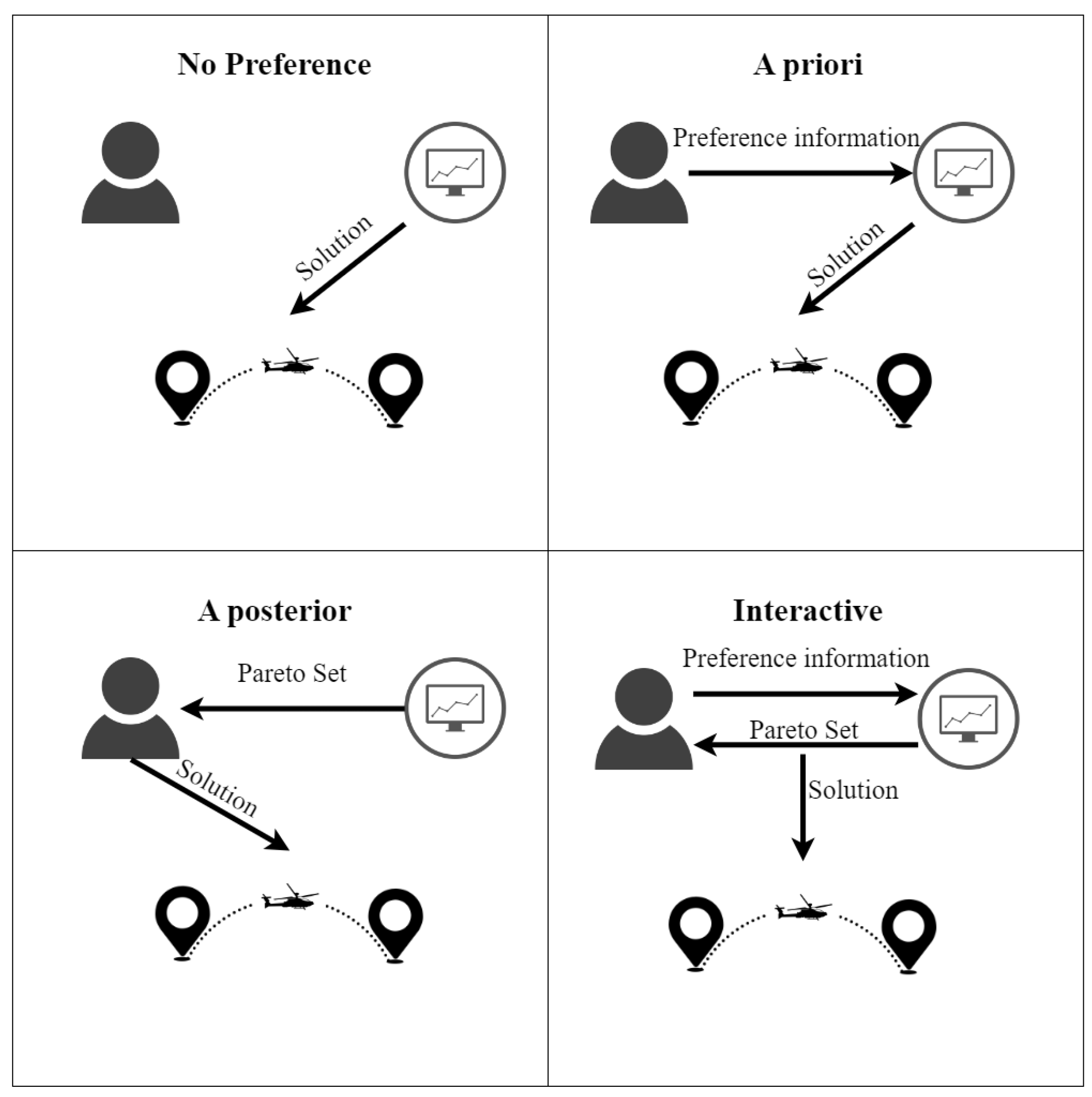

No-preference Preference HandlingFirstly, in no-preference methods, the DM is not involved in the process. Instead, a solution which is a neutral compromise between all objectives is identified. This method is commonly used when no DM is present and it usually constructs a scalar composite objective function .

-

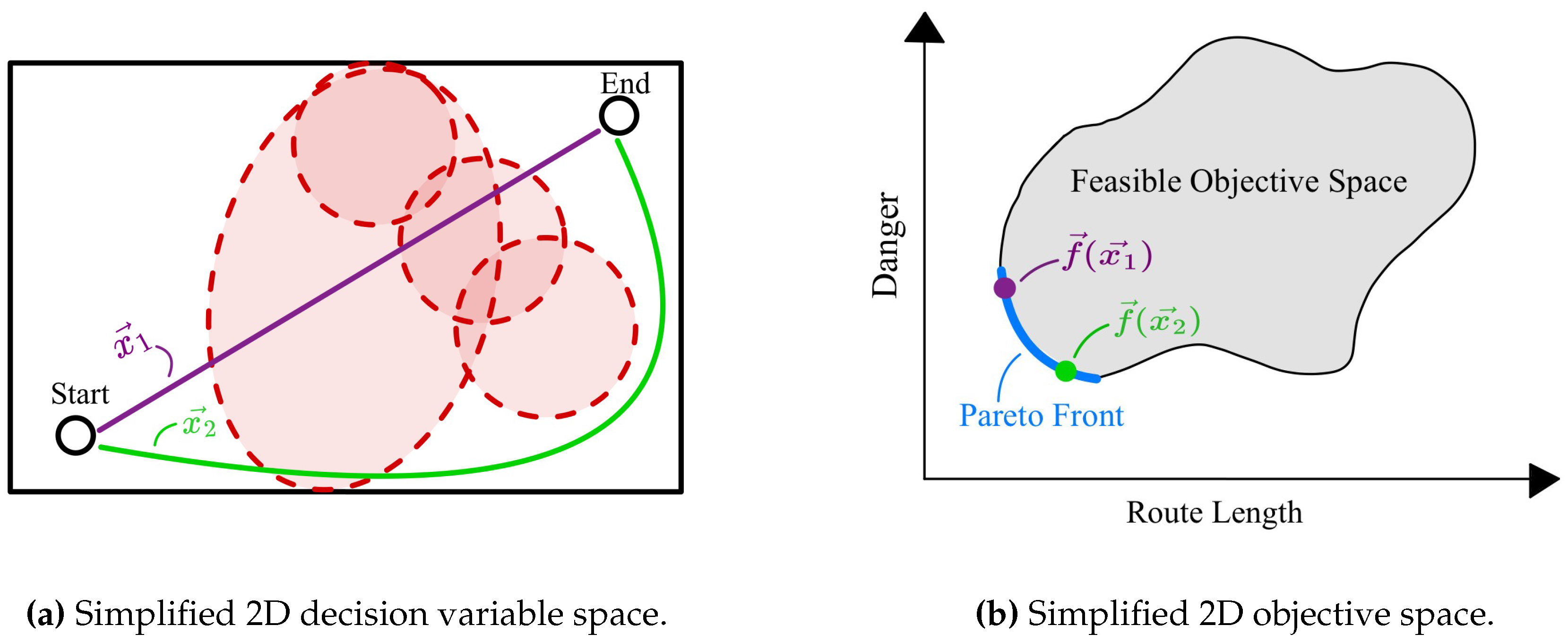

a-priori Preference HandlingSecondly, in a-priori methods, a DM specifies their preference information before the optimization process is started. Most commonly, the preference information is used to construct a scalar composite objective function . This has the advantage that the problem is simplified into a single-objective optimization problem. As a result existing single-objective optimization algorithms can be used. The main limitation is that the DM has limited knowledge of the problem beforehand, which can result in inaccurate and misleading preferences [18,19]. Intuitively, asking the DM to specify their preferences before the optimization corresponds to asking them to select a point on the Pareto Front (e.g. by specifying objective weights) before knowing what the actual Pareto Front and its corresponding tradeoffs look like. Consequently, a set of preferences specified a-priori might lead to solution x, whereas the DM might have preferred y when presented with both options.

-

a-posterior Preference HandlingAlternatively, a-posterior methods can be used. These methods include the DM’s preferences after the optimization process. First, they approximate the Pareto Front and then allow the DM to choose a solution from said front. The main advantage is that the DM can elicit their preferences on the basis of the information provided by the Pareto Front. The DM has a better idea of the tradeoffs present in the problem and can thus make a better-informed choice. Furthermore, it can provide the DM with several alternatives rather than a single solution. The disadvantage of this class of methods is the large computational complexity of generating an entire set of Pareto optimal solutions [20]. Additionally, when the Pareto Front is high-dimensional, the large amount of information can cognitively overload and complicate the decision of the DM [18].

-

Interactive Preference HandlingFinally, interactive preference elicitation attempts to overcome the limitations of the a-priori and a-posterior classes by actively involving the DM in the optimization process. As opposed to the sequential views of a-priori and a-posterior methods, the optimization process is an iterative cycle. Optimization is alternated with preference elicitation to iteratively update a preference model of the DM and to quickly identify regions of the Pareto Front that are preferred. Undesired parts of the Pareto Front need not be generated, which saves computational resources. Instead, these resources can be spent on better approximating the preferred regions, improving their approximation quality [21]. Lastly, being embedded in the optimization process helps the DM build trust in the model and a better understanding of the problem, the tradeoffs involved, and the feasibility of their preferences [22,23,24]. One challenge of interactive methods is that the interaction needs to be explicit enough to build an expressive and informative model of the DM’s preferences whilst also being simple enough for the DM to not cognitively overload them.

4. Preference Handling Methods and Their Implications

4.1. No Preference - Preference Handling

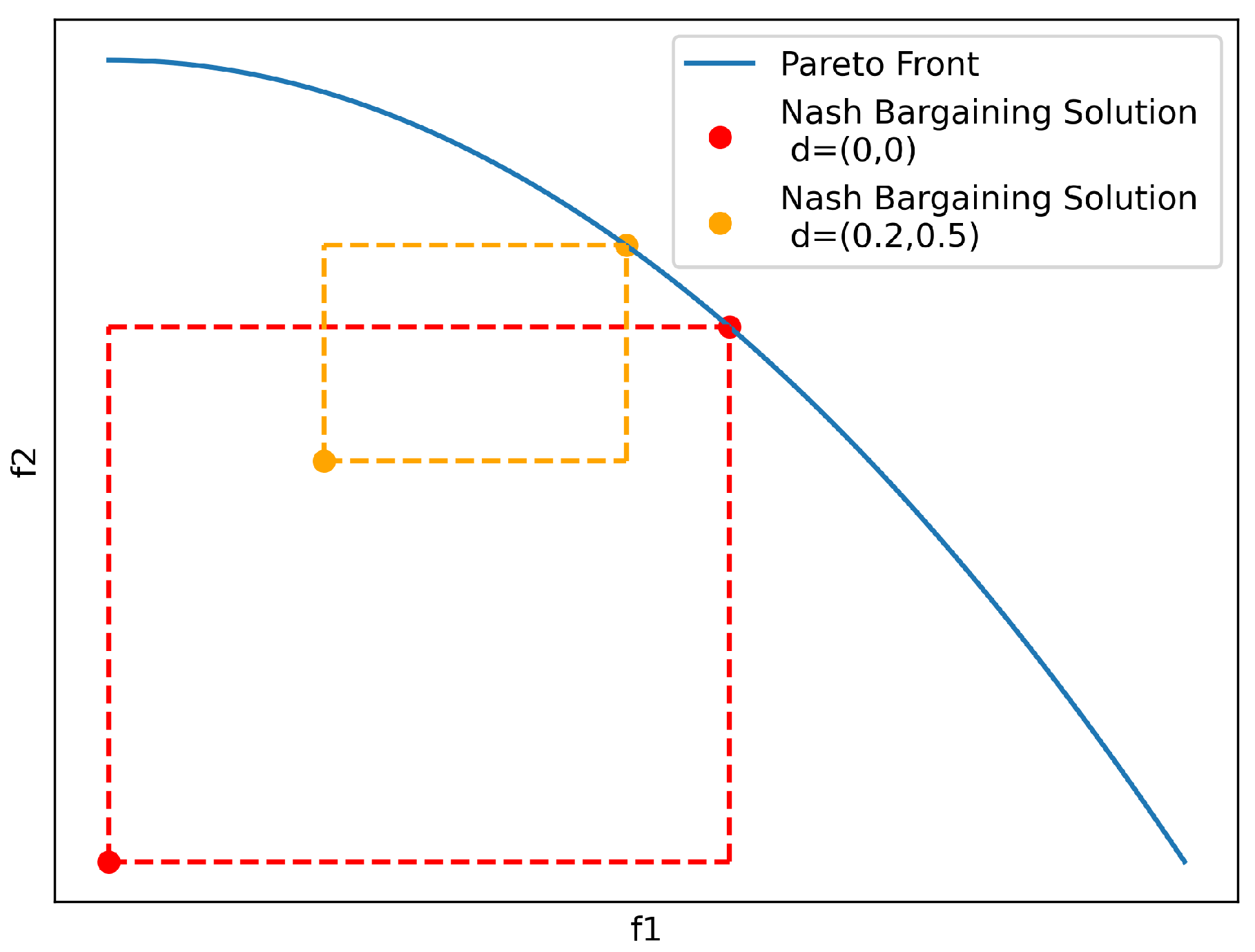

4.1.1. Nash Product

-

Pareto Optimality - EfficiencyThe identified Nash Bargaining Solution is a Pareto-optimal solution [32], which, of course, is a desirable property.

-

Symmetry - FairnessWhen the game is symmetric, which is the case for the Nash Bargaining Solution defined in Equation 3, the solution does not favor any objective but returns a fair solution [35]. The concept of Nash Bargaining can be extended to include asymmetric games by introducing weights to the problem, as in Equation (4). These weights can be determined by the DM, where they correspond to the preferences with respect to certain objectives [36]. This extends the Nash Bargaining Solution from a no-preference method to an a-priori method.

-

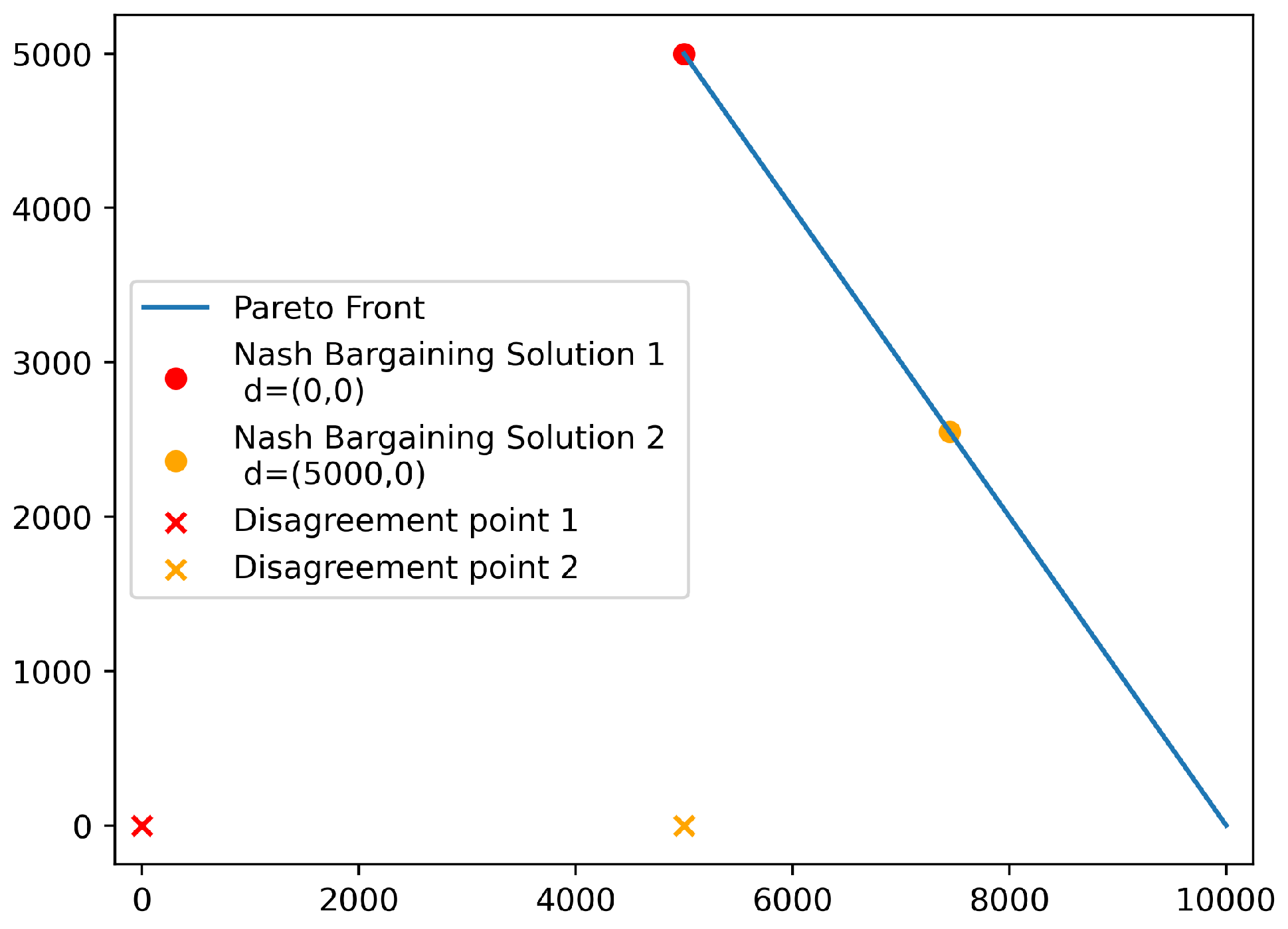

Scale Invariance - No NormalizationMathematically, this property means that any positive affine transformation of the objectives does not influence the decision-theoretic properties of the optimization problem. Intuitively, this means that the Nash Bargaining Solution is independent of the unit of the objectives. It does not matter whether one is measuring route length in kilometers or miles. Instead of comparing units of improvement in one objective to units of degradation in another objective, ratios are compared. For example, a route twice as dangerous but half as long as another route is equally good in this view. One important implication of this is that there is no need to normalize the objectives before optimizing.

-

Independence of Irrelevant AttributesThis axiom states that removing any feasible alternative other than the optimal Nash bargaining solution does not influence the optimal solution. This axiom has often been critiqued [37], but in the rational optimization context, it makes sense. Removing a nonoptimal solution, should not change what the optimal solution is.

4.2. a-priori Preference Handling

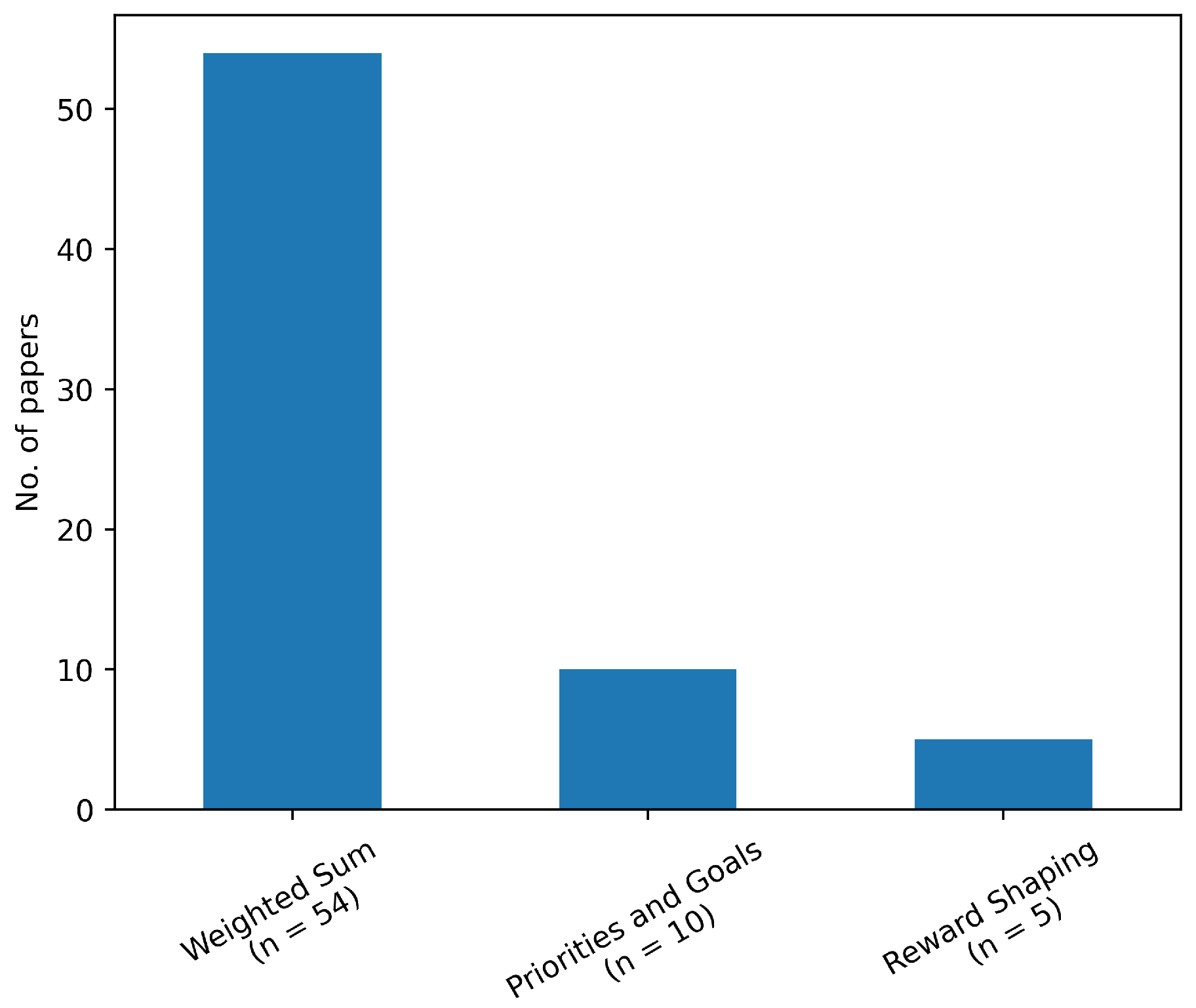

4.2.1. Weighted Sum Method

-

Constraints - Normalization and Weakly Dominated PointsThe first constraint: does not impose any constraints on the optimization problem. Any weight vector could be normalized to satisfy the constraint. However, restricting the DM to choose weights according to this constraint can cause unnecessary complications. Generally, the weight vector is interpreted to reflect the relative importance of the objectives [40]. In the case where one objective is five times more important than the other, it would be much easier for a DM to set the weights as than . This becomes especially troublesome when there are many objectives, hindering the interpretability of the weight vector. Therefore, it is better to normalize the weights automatically after weight specification rather than restricting the DM in their weight selection.The second constraint can pose a problem when one of the objective weights is equal to 0. When setting to 0, a solution with objective values is equivalent to . The equivalence of these two objective vectors introduces weakly-dominated points (i.e. points like x for which a single objective can be improved without any deterioration in another objective) to the Pareto Front. When the DM truly does not care about this is not a problem, however, when one would still prefer y over x, one could set the weight of to a very small value instead of 0 [41]. This allows the method to differentiate between and using the third objective , removing weakly dominated points from the Pareto front.

-

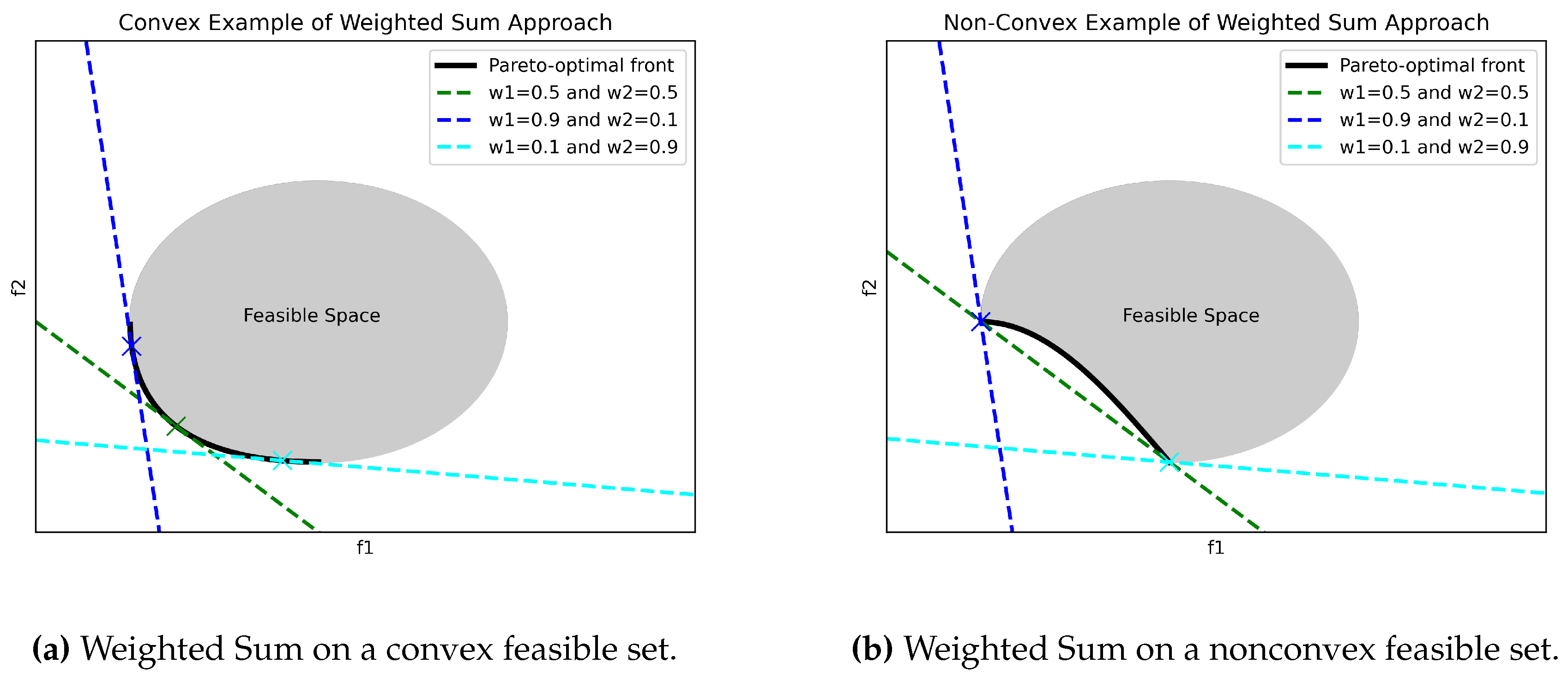

Mathematical Form - Imposing LinearityThe mathematical form of the equation refers to the functional composition of the composite objective function. In all papers identified, a linear combination of objective functions, as defined in Equation (5), has been employed. However, there is no reason, besides simplicity, why the equation has to be a simple linear combination. In fact, because Equation (5) is a linear combination of the objectives, it imposes a linear structure on the composite objective function. Preferences, on the other hand, generally follow a nonlinear relationship [42]. A DM might approve a 20km detour to reduce the probability of detection from 0.2 to 0 but might be less willing to do so to reduce the probability of detection from 1 to 0.8. Furthermore, imposing a linear structure on the preferences leads to favoring extreme solutions whereas DMs generally favor balanced solutions [40]. This is particularly troublesome when the feasible objective space is non-convex, as can be seen in Figure 9 (compare Figure 9a to Figure 9b). The linear weighted sum is not able to find any solution between the two extremes. Points on this non-convex section of the Pareto Front cannot be identified by a linear weighted sum. In discrete cases, it has been shown that up to 95% of the points can remain undetected [43].

-

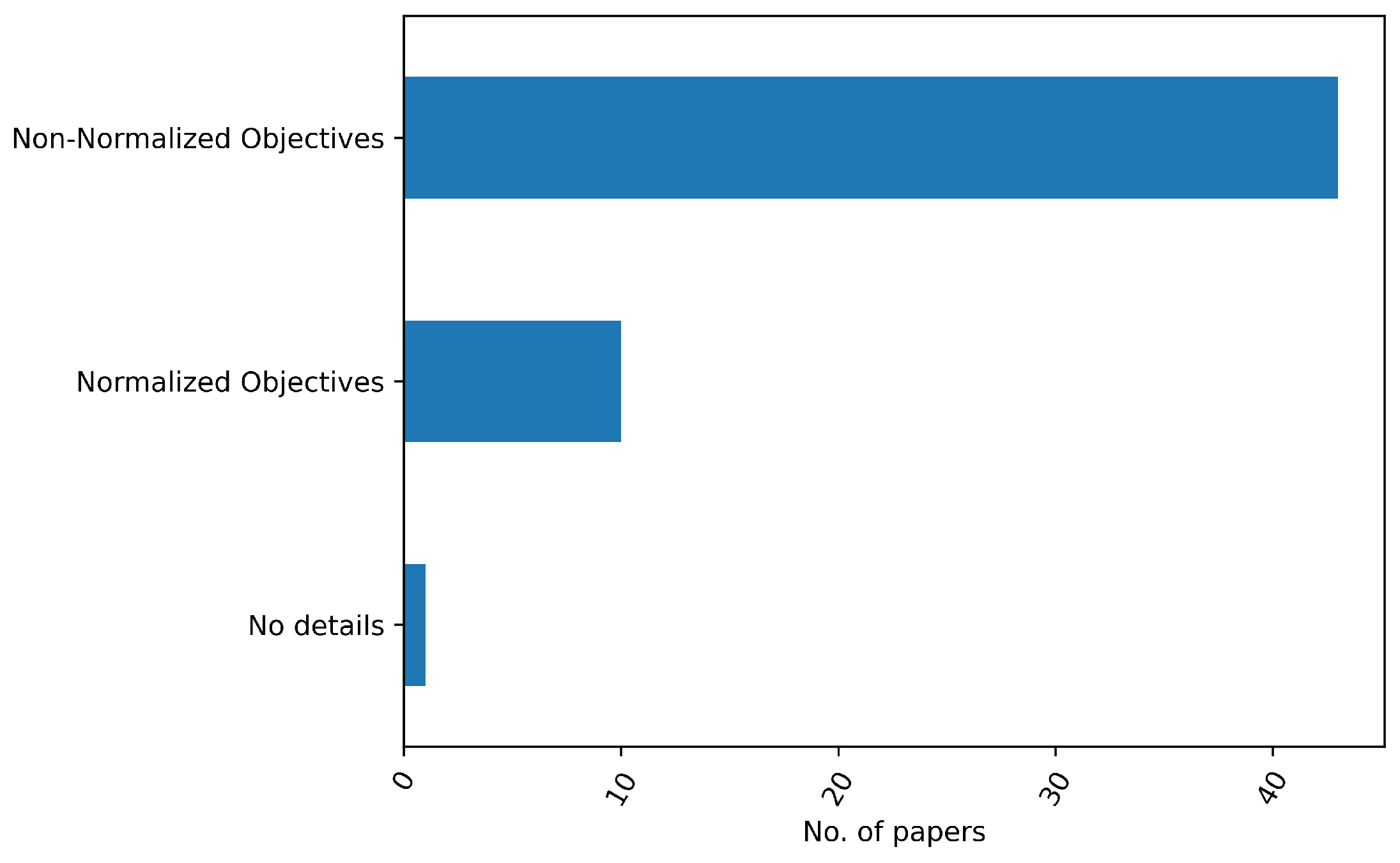

Weight vector - Relative Importance of ObjectivesThis very simple method poses a not-so-simple question: how does one determine the weights? There is no unique answer to this, as the weight vector needs to be determined by the DM and it differs per scenario. The most common interpretation of the weights is to assign them based on the relative importance of the individual objectives. For example, in a bi-objective problem case, setting and assumes that objective 2 is twice as important. However, as shown by Marler & Arora [40] the value of a weight is significant relative to both the weights of the other objectives and all the objective function’s ranges. In particular, if objective 1’s range is much higher than objective 2’s range, objective 1 will still dominate regardless of the weight set. Therefore, normalizing the objectives is necessary. Although the normalization of objectives is a necessary precondition to interpret weights as relative importance, only a very small portion () of the literature has done so, as can be seen in Figure 10. Alternatively, one can interpret the ratio of the weights as the slope of the line crossing the mathematical optimum on the Pareto Front. By changing the slope, one can identify other points on the Pareto front. However, as one does not know the shape of the Pareto front a-priori, it is hard to relate the slope of the line to the final MPS. For example, in Figure 9b, a ratio of 1 does not actually result in a balanced solution.Additionally, it is hard for a DM to set the weights before having information about the possible trade-offs. Why should the weight vector be chosen? Why not ? How much would the solution and its objective values change when slightly changing the weights? These questions are important, as in a practical setting a DM will need to trust that the weights set lead to the most preferred solution and that that solution is robust to a small weight change.

4.2.2. Reward Shaping

4.2.3. Decision-Making Based on Goals and Priorities

-

Priorities - Lexicographic OrderingCategorizing objectives into priorities imposes an absolute ordering on the objectives. Even an infinitely small improvement in a higher-priority objective is preferred over an infinitely large improvement in a lower-priority objective. This ordering is called a lexicographic ordering and its sequential optimization process is called lexicographic optimization [8]. First, the highest priority is optimized. Only when there are ties or when all goals are achieved, subsequent priority levels are considered. For each lower priority level, one thus need more ties or more achieved goals, making it less likely to even reach the lower priority levels. Indeed, the presence of an excessive amount of priority levels, causes low-level priorities to be ignored [64]. Moreover, even when only two priority levels are used, such a strong lexicographic ordering has strong implications. It makes sense when a clear natural ordering is available. For example, satisfying a UAV’s flight constraints is always preferred to optimizing an objective, as a route that cannot be flown is always worse than a route that can be flown. However, for optimization objectives, this is usually not the case. It is hard to argue that there is no trade-off possible between criteria. Surely, a huge decrease in the route length warrants a tiny increase in the probability of detection. Therefore, when setting priority levels, objectives should only be categorized differently when one is infinitely more important than the other.

-

Goals - Satisficing vs OptimizingSetting goals has a profound impact on the resulting final solution – it can have as large an impact, if not more, as the mathematical definition of the objective functions themselves [65]. In fact, the entire underlying philosophy of the optimization process can change when a goal is set to an attainable value versus an unattainable value. When the goals are set at attainable values, goal programming essentially follows a satisficing philosophy. This philosophy, named after the combination of the verbs to satisfy and to suffice, introduced by Simon [66], argues that a decision-maker wants to reach a set of goals, and when they are reached this suffices for them and hence they are satisfied [67]. Mathematically, this means that objectives are optimized until they reach a goal value. Any further improvements are indifferent to the DM. For constraints, this makes sense, satisfying the goals imposed by a UAV flight constraints suffices. There is no need to make even tighter turns than the turn constraint imposes. For optimization objectives, however, this contradicts the entire concept of optimizing, for which "less is always better" (i.e. a monotonic belief). Even when the goal value for the danger levels is satisfied, a solution that has less danger is preferred. Note that this does not align with the principle of Pareto-optimality and can thus result in dominated solutions. This is precisely the main disadvantage of setting goals for optimization objectives. Indeed imposing attainable goals on monotonic optimization objectives should not be done. Instead, for monotonic objectives, goals should be set to unattainable values [68] to ensure the optimization process optimizes rather than satisfices. Alternatively Pareto-dominance restoration techniques can be used (e.g. see Jones & Tamiz [69]). Finally, when objectives in the same priority level all have goals, the objective will be to minimize the sum of unwanted deviations from the goals. For this sum to weigh objectives equally, objectives need to be on the same order of magnitude (i.e. commensurable). Therefore, when they are incommensurable, the objectives need to be normalized [64].Clearly, setting goals properly is of the utmost importance. So, how would one reliably set goals? To determine whether a goal value is realistic and attainable, one needs information regarding the ranges of the objective functions as well as the trade-offs in objective space, and the beliefs of the DM about the objectives (e.g. is it a monotonic objective?). a-priori, such information is not present. Therefore, setting goals is usually not done a-priori, but rather it is an iterative (i.e. interactive) process.

4.3. A-Posterior Preference Handling

-

Optimization: Generating the Pareto frontTo generate the entire Pareto front, the UAV route planning literature has used two distinct methods. In two papers [70,71], the Pareto front is approximated directly using metaheuristics, in particular, evolutionary algorithms. These optimization algorithms use an iterative population-based optimization process to get an approximation of the Pareto front. As the scope of the paper is on preference handling techniques, evolutionary algorithms will not be discussed. Instead, they are extensively covered in existing surveys identified in Table 1 as well as by Yahia & Mohammed [72] and Jiang et al. [73]. The two other papers: Dasdemir et al. [74] and Tezcaner et al. [75] reformulated the problem using the -constraint method. This method is a general technique that reformulates the problem into a series of single-objective optimization problems. Although it is not directly a preference handling method, it is a general method to deal with multiple criteria and can be combined with any optimization algorithm. Therefore, it is covered in Section 4.3.1.

-

Preference Handling: Selecting the most preferred solutionNone of the identified papers that generate the entire Pareto front cover the preference handling stage after the optimization. Instead, they simply assume that the DM can choose their most preferred solution based on the Pareto front. However, as explained at the start of Section 3, choosing a solution from the Pareto front is not a straightforward task. For example, when the Pareto front is high dimensional, the DM will face cognitive overload. One paper [70] addresses this by first linearly aggregating multiple objectives into two composite objective functions to lower the dimensionality. Afterwards, the authors assume that the DM can choose their most preferred solution from the two-dimensional Pareto front. However, to linearly aggregate the objectives, the method requires a-priori preference information (i.e. a weight vector), thereby, introducing the same challenges of a-priori preference handling and in particular of the weighted sum. Clearly, the focus of the aforementioned papers is on the optimization process and on the creation of a Pareto front. The subsequent step of selecting the MPS, however, is neglected. The DM is not aided in this process, which hinders the usability of the method. In particular, the decision-aid aspect of optimization is neglected.

4.3.1. -Constraint Method

-

Constraint Introduction - Problem ComplexityThe introduction of constraints can greatly complicate the structure of the optimization problem. In particular, for the shortest path problem, introducing constraints changes the complexity of the problem from polynomially solvable to NP-complete [76]. Therefore, for larger problem instances, an exact -constraint method for the UAV route planning problem is not possible. Instead, for example, metaheuristics can be used to solve the formulated single-objective optimization problem.

-

Weakly Dominated PointsThe -constraint method can generate weakly dominated points. In particular, the method will generate all points that satisfy the constraint on and for which is at its minimum. When there is no unique solution (i.e. multiple solutions x for which is at its minimum), all of these solutions can be generated. Of course, in this case, one would prefer to only keep the solution with minimal . Therefore, one could add a second optimization problem that optimizes w.r.t. given the optimal value. Note that this is lexicographic optimization [77]. Alternatively, one could eliminate these weakly efficient solutions by modifying the objective function slightly. In particular, in the augmented -constraint method, the problem is reformulated to include a small term meant to differentiate between weakly efficient and efficient solutions [41]. For example, in the bi-objective case, we add the factor to get Equation (9). When is sufficiently small to only differentiate between solutions with equal , we remove weakly efficient solutions from the equation. Note that this happens without the need for the formulation and solving of additional optimization problems, thereby saving computational resources. Alternative solutions to remove weakly efficient solutions are available (e.g. Mavrotas [78]).

-

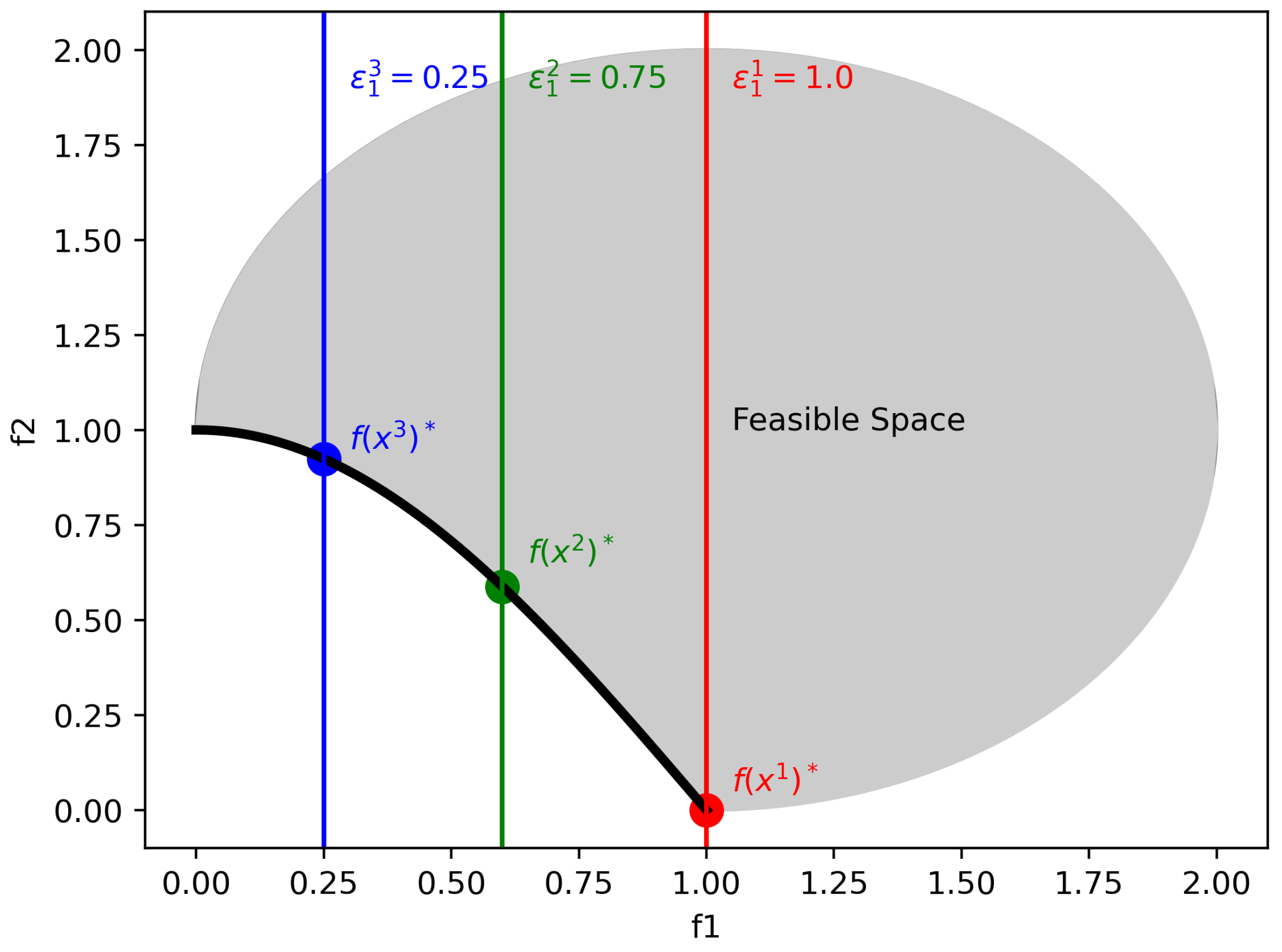

Start and End Points of Tightening - Objective RangeIn order to get the full Pareto front, one needs to know where to start systematically tightening the bound and when to stop tightening the bound. In particular, the loose bound (starting point) is the nadir point. The ending point of the method is when the bound is at its tightest and only one solution remains. This is at the ideal point, the point with the best possible objective values of points on the Pareto front. The ideal point is easy to estimate; one simply needs to solve a single-objective minimization problem for each objective i and the resulting optimal objective value will be the ideal point of dimension i [8]. For the nadir point, one can take the worst objective values found by solving the series of single-objective optimization problems. In the bi-objective case, this will find the exact nadir point. However, when there are more than two objectives, this can greatly over- or under-estimate the nadir point [8,78]. Many different estimation methods exist (for a survey see Deb & Miettinen [79]) but no efficient general method is known [8].

-

Systematically Tightening the WeightsOriginally, the epsilon constraint method tightens the bounds of each constraint i by a value . The value of relative to the range of the objectives determines how detailed the generated Pareto front will be. A large results in a coarse Pareto front, whereas a small results in a fine-grained Pareto front. In particular, this can be seen as the stepsize of the method. Increasing it makes bigger steps, leading to a coarser Pareto front. At the same time, it decreases the computational complexity. A bigger stepsize, reduces the amount of steps needed to reach the ideal point, hence fewer optimization problems need to be solved. Therefore, needs to be fine enough to get a good approximation of the Pareto front but coarse enough to prevent a lot of redundant computational effort [80]. Alternatively, one can tighten the weights adaptively. When the bound is at a non-Pareto efficient part of the objective space, larger steps can be taken, whereas when the bound is at a Pareto efficient point, small steps can be taken. An example of this can be found in Laumans et al. [80].

4.4. Interactive Preference Handling

4.4.1. Interactive Reference Point-Based Methods

-

Preference Information - Reference pointPreference information is supplied by means of a reference point. Providing reference points is a cognitively valid way of providing preference information [84], as DMs do not have to learn to use other concepts. Instead, they can simply work in the objective space, which they are familiar with. However, as discussed in Section 4.2.3, using goals can result in dominated solutions due to the satisficing philosophy. Therefore, it is important to handle dominated solutions when using interactive reference point-based methods. Dasdemir et al. [83] prevent dominated solutions by keeping track of a set of nondominated solutions throughout the entire optimization process. After the optimization is done, the set of nondominated points that are closest to the reference point are returned as the ROI. Therefore, assuming the evolutionary algorithm has found nondominated solutions, only nondominated solutions will be returned.Additionally, when achieving one goal is more important than achieving another goal, it can be difficult to represent this with a reference vector. Therefore, a weighted variant [85] exists that introduces relative importance weights in the distance function (see preference model below). Note that although this gives the DM the possibility to include preferences regarding the importance of achieving certain goals, specifying weights is not a trivial task (as described in Section 4.2.1).

-

Preference Model - Distance FunctionBased on the provided reference point, a preference model is constructed. The preference model captures the subjective preferences of the DM and uses them to identify the ROI on the Pareto front. In interactive reference point-based methods, the preference model is usually fully determined by the combination of a scalar distance function and the reference point [85,86]. This distance function is sometimes called an Achievement Scalarizing Function, which essentially does distance minimization [87]. The choice of distance function has an influence on the chosen ROI. For example, by using a quadratic distance function, points far away from the reference point are punished more than by using a linear function. Moreover, by choosing a nonlinear distance function, one introduces nonlinearity, alleviating the issues of the weighted sum methods, described in Section 4.2.1. In Dasdemir et al. [83] the distance function is the normalized euclidean distance (which is nonlinear) to the reference point. The solution closest to the reference point will be ranked 1, the second closest will be ranked 2, etc. Whichever solution is closer (based on the chosen distance function) to the reference point is thus preferred by the DM.Instead of finding a single most preferred solution, interactive reference point-based methods aim to identify an ROI. To identify this ROI, one needs to balance specificity and diversity. In particular, the ROI should not collapse into a single point because it is too specific, but it should also not be too diverse such that it is spread around the entire Pareto front. Therefore, to tune the spread of the ROI, an -niching method is commonly used [81] (e.g. in R-NSGA-II [88] and RPSO-SS [89]). Dasdemir et al. [83] also employ such an -niching method. In particular, one representative is constructed and all solutions within an -ball to the representative are removed. Subsequently, the next representative outside of the -ball is created and the process repeats. By increasing , more solutions will be deemed equal and the ROI will be wider and vice versa. Setting this design parameter, however, is not trivial [81]. For example, in the exploration phase a DM could want a more diverse spread of the ROI compared to when the DM tries to find the final most preferred solution. Therefore, adaptively changing the based on whether the DM is exploring or selecting his MPS might be useful.

-

Feedback to the DM - Pareto Front InformationOne of the main advantages of using interactive optimization methods is that the DM can learn from the possibilities and limitations of the problem at hand by receiving feedback from the optimization process. Based on the learned information, a DM can better identify the ROI of the Pareto front. The feedback provided to the DM can take many forms. For example, possible trade-off information or a general approximation of the Pareto front can be provided. For an interactive system to work correctly, it is vital that the interaction is not too cognitively demanding for the DM (i.e. cognitive overload). At the same time, the information needs to be rich enough to provide the DM with the necessary capabilities to correctly identify their ROI. Moreover, different DMs have different skillsets and affinities with optimization, therefore, interaction should be designed in close collaboration with the relevant DMs.In Dasdemir et al. [83], the feedback provided to the DM is a general approximation of the Pareto front (although no guarantees are given that the provided points are actually nondominated points). In the bi-objective case they evaluate, this is a cognitively valid way of information communication, but when the Pareto front becomes higher dimensional it can cognitively overload the DM [90]. Therefore, alternative visualization methods exist (e.g. Talukder et al. [91]). Besides that, the interaction is not designed nor evaluated with the relevant DMs, therefore, it is hard to say whether, in this context, Pareto front information is an appropriate way to communicate information to the DM.

-

Interaction Pattern - During or After a RunFinally, when designing an interactive optimization method, one needs to decide at what point the DM is allowed to provide preference information. In particular Xin et al. [81] have identified two interaction patterns: Interaction After a complete Run (IAR) and Interaction During a Run (IDR). Reference-point based methods generally follow the IAR method. IDR methods, on the other hand, give the DM more chances to guide the search process, thereby making it more DM-centric. Alternatively, one could allow the DM to intervene at will, either waiting for a complete run or stopping the run. Most importantly, there needs to be balance between requesting preference information and optimization. We do not want to strain the DMs too much by asking them to provide a lot of preference information, but at the same time we need to be able to build an accurate preference model and allow the DM to be in control.

5. Conclusion and Future Research

-

Aligning the mathematical optimum with the MPSThe goal of the route planning problem is to aid the decision-maker in finding their MPS. Currently much of the research is focused on improving optimization algorithms. No doubt, it is important to ensure that a mathematical optimum can be found. However, when this mathematical optimum does not result in the DM’s MPS, the optimization is useless. Therefore, more effort should be put on aligning the mathematical optimum with the DM’s MPS. In order to do so, accurate representations of the DM’s preferences are needed. Additionally, the DM should be able to correctly formulate and provide their preference information.

-

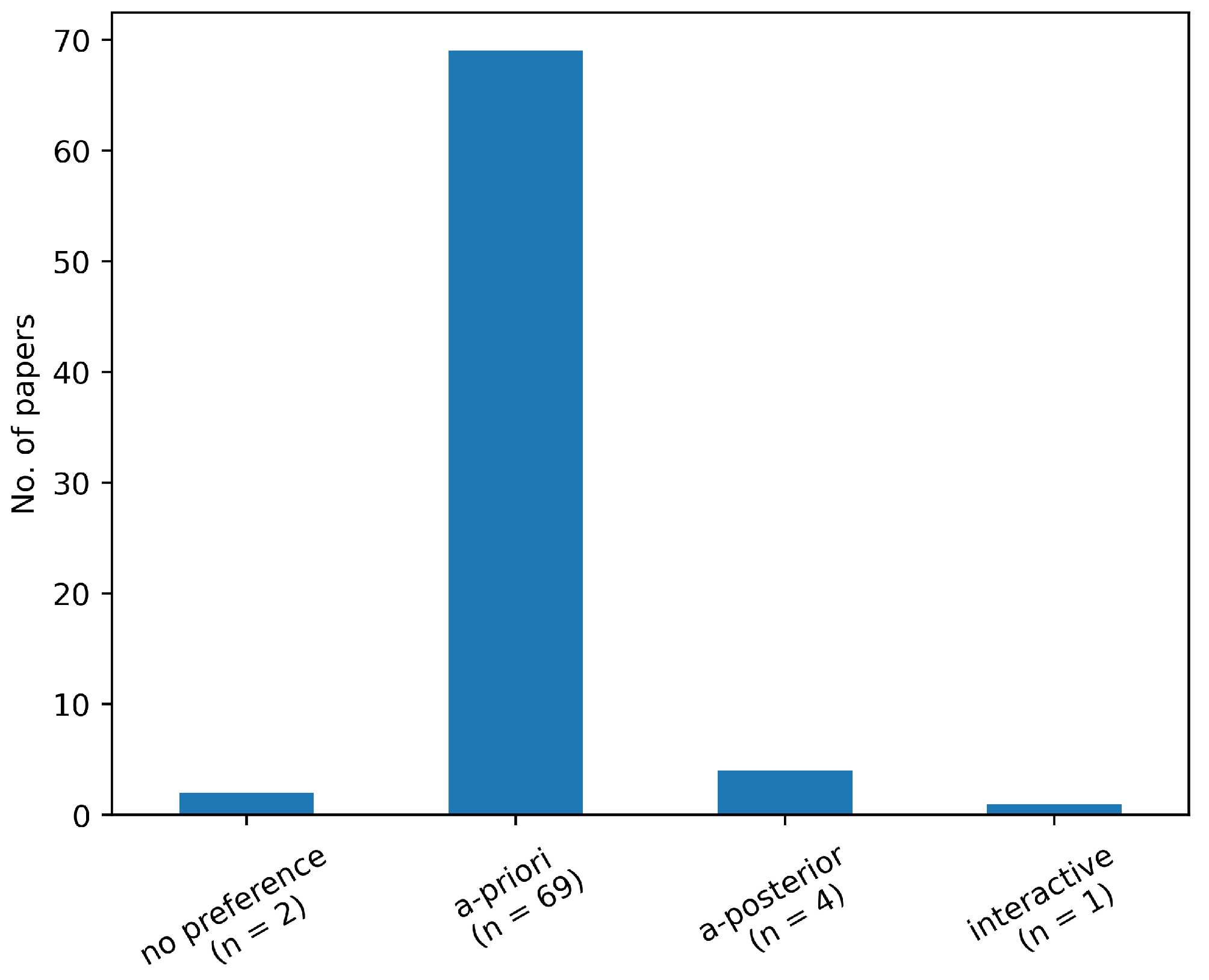

a-posterior and interactive preference handlingSpecifying one’s preferences before any knowledge of the possibilities and limitations of the problem is an almost impossible task and can result in an inferior result. However, as our literature has shown, nearly 90% of the papers employs a-priori preference handling. Therefore, it would be interesting to further investigate a-posterior and interactive preference handling techniques.

-

DM-centric evaluationFinally, as the goal of the route planning problem is to help DMs arrive at their MPS, the performance should be evaluated in this regard as well. In particular, methods should be evaluated based on their decision-aid capabilities and not just on algorithmic performance. Therefore, evaluation with expert DMs is an interesting direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Durc Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| EW | Electronic Warfare |

| DM | Decision-Maker |

| MPS | Most Preferred Solution |

| RQ | Research Question |

| NLDA | Netherlands Defence Academy |

| NPS | Naval Postgraduate School |

| AIAA | American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics |

| MOO | Multi Objective Optimization |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| IAR | Interaction After complete Run |

| IDR | Interaction During Run |

Appendix A

| Reference | Class | Method | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flint et al. [26] | No Preference | Nash Product | Not Applicable |

| Kim & Hespanha [92] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Misovec et al. [93] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Dogan [60] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Chaudhry et al. [61] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Qu et al. [94] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| McLain & Beard [95] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Ogren & Winstrand [62] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Preference Assumed |

| Changwen et al. [96] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Weiss et al. [97] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Foo et al. [98] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Ogren et al. [57] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Preference Assumed |

| Kabamba et al. [58] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Not Applicable |

| Zabarankin et al. [63] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Zhang et al. [99] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Lamont et al. [70] | a-posterior | L-WS, Pareto Front | Provide Pareto Front |

| Zhenhua et al. [71] | a-posterior | Pareto Front | Provide Pareto Front |

| de la Cruz et al. [55] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Preference Assumed |

| Xia et al. [100] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Tulum et al. [101] | a-priori | L-WS | Heuristic approximation |

| Qianzhi & Xiujuan [102] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wang et al. [103] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhang et al. [104] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Besada-Portas et al. [56] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Preference Assumed |

| Xin Yang et al. [105] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Yong Bao et al. [106] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Kan et al. [107] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Lei & Shiru [108] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhou et al. [109] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Holub et al. [110] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Chen et al. [111] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Li et al. [112] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wallar et al. [113] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Yang et al. [54] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Preference Assumed |

| Qu et al. [114] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Duan et al. [115] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Chen & Chen [111] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wang et al. [116] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Xiaowei & Xiaoguang [117] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wen et al. [118] | a-priori | L-WS | Expert DM |

| Zhang et al. [119] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Erlandsson [44] | a-priori | reward shaping | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Humphreys et al. [120] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Tianzhu et al. [121] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wang & Zhang [122] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Jing-Lin et al. [123] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Savkin & Huang [59] | a-priori | Goals and Priorities | Not Applicable |

| Zhang et al. [124] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Maoquan et al. [125] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Danacier et al. [126] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Chen & Wang [127] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhang & Zhang [128] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Patley et al. [129] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Ma et al. [130] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Dasdemir et al. [83] | interactive | Reference Point-based | Author as DM |

| Zhang et al. [131] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Wu et al. [132] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Xiong et al. [133] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhang et al. [134] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Yan et al. [45] | a-priori | reward shaping | Preference Assumed |

| Abhishek et al. [27] | no preference | Nash product | Not Applicable |

| Zhou et al. [135] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhang et al. [136] | a-priori | L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Xu et al. [137] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Huan et al. [138] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Leng & Sun [139] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

| Yuksek et al. [46] | a-priori | reward shaping | Preference Assumed |

| Woo et al. [140] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Lu et al. [141] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Zhang et al. [142] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Alpdemir [47] | a-priori | reward shaping | Preference Assumed |

| Dasdemir et al. [74] | a-posterior | Pareto Front | Provide Pareto Front |

| Zhao et al. [48] | a-priori | reward shaping | Preference Assumed |

| Tezcaner et al. [75] | a-posterior | Pareto Front | Provide Pareto Front |

| Zhang et al. [143] | a-priori | L-WS | Preference Assumed |

| Luo et al. [144] | a-priori | N-L-WS | Multiple preferences visualized |

References

- Buckley, J. Air Power in the Age of Total War, 1 ed.; Routledge, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Imperial War Museums. A Brief History of Drones.

- Central Intelligence Agency. Remotely Piloted Vehicles in the Third World: A New Military Capability, 1986.

- Lambeth, B.S. Moscow’s Lessons from the 1982 Lebanon Air War. Technical report, RAND, 1984.

- Zafra, M.; Hunder, M.; Rao, A.; Kiyada, S. How drone combat in Ukraine is changing warfare, 2024.

- Watling, J.; Reynolds, N. Meatgrinder: Russian Tactics in the Second Year of Its Invasion of Ukraine Special Report. Technical report, Royal United Services Institute, 2023.

- Milley, M.A.; Schmidt, E. America Isn’t Ready for the Wars of the Future, 2024.

- Ehrgott, M. Multicriteria Optimization, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2005; p. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Path planning techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: A review, solutions, and challenges. Computer Communications 2020, 149, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Djahel, S.; Welsh, K. Path-Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles with Environment Complexity Considerations: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravankar, A.; Ravankar, A.A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hoshino, Y.; Peng, C.C. Path Smoothing Techniques in Robot Navigation: State-of-the-Art, Current and Future Challenges. Sensors 2018, 18, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Qi, G.; Xu, L. A Survey of Three-Dimensional Flight Path Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC). IEEE, 6 2019, pp. 5010–5015. [CrossRef]

- Ait Saadi, A.; Soukane, A.; Meraihi, Y.; Benmessaoud Gabis, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. UAV Path Planning Using Optimization Approaches: A Survey. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2022, 29, 4233–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y. Survey on computational-intelligence-based UAV path planning. Knowledge-Based Systems 2018, 158, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, K. Nonlinear Multiobjective Optimization; Vol. 12, International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, L.; Miettinen, K.; Korhonen, P.J.; Molina, J. A Preference-Based Evolutionary Algorithm for Multi-Objective Optimization. Evolutionary Computation 2009, 17, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Olhofer, M.; Jin, Y. A mini-review on preference modeling and articulation in multi-objective optimization: current status and challenges. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2017, 3, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcaner, D.; Köksalan, M. An Interactive Algorithm for Multi-objective Route Planning. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 2011, 150, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, S.; Huber, S. Objectives and methods in multi-objective routing problems: a survey and classification scheme. European Journal of Operational Research 2021, 290, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Miettinen, K.; Ruiz, F. Assessing the Performance of Interactive Multiobjective Optimization Methods. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 54, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, V.; Branke, J.; Eskelinen, P.; Greco, S.; Molina, J.; Ruiz, F.; Słowiński, R. Interactive Multiobjective Optimization from a Learning Perspective. In Multiobjective optimization: Interactive and evolutionary approaches; Branke, J.; Miettinen, K.; Slowinski, R., Eds.; Theoretical Computer Science and General, 2008; Vol. 5252, pp. 405–433. [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.L. Review of Empirical Studies in Multiobjective Mathematical Programming: Subject Reflection of Nonlinear Utility and Learning. Decision Sciences 1992, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaira, A.; Dwivedi, R. A State of the Art Review of Analytical Hierarchy Process. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 4029–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, M.; Fernandez-Gaucherand, E.; Polycarpou, M. Cooperative control for UAV’s searching risky environments for targets. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Decision and Control (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37475). IEEE, 2003, pp. 3567–3572. [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, B.; Ranjit, S.; Shankar, T.; Eappen, G.; Sivasankar, P.; Rajesh, A. Hybrid PSO-HSA and PSO-GA algorithm for 3D path planning in autonomous UAVs. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.F. The Bargaining Problem. Econometrica 1950, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.; Nakamura, K. The Nash Social Welfare Function. Econometrica 1979, 47, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, J.N. Moral Implications of Rational Choice Theories. In Handbook of the Philosophical Foundations of Business Ethics; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp. 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brânzei, S.; Gkatzelis, V.; Mehta, R. Nash Social Welfare Approximation for Strategic Agents. Operations Research 2022, 70, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhgard, H.; Keshanian, K.; Esmaeilbeigi, R.; Charkhgard, P. The magic of Nash social welfare in optimization: Do not sum, just multiply! ANZIAM Journal 2022, 64, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narahari, Y. Cooperative Game Theory; The Two Person Bargaining Problem, 2012.

- Zhou, L. The Nash Bargaining Theory with Non-Convex Problems. Econometrica 1997, 65, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D. Bargaining games : a comparison of Nash’s solution with the Coco-value, 2016.

- Binmore, K.; Rubinstein, A.; Wolinsky, A. The Nash Bargaining Solution in Economic Modelling. The RAND Journal of Economics 1986, 17, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, N.; Volij, O.; Winter, E. A characterization of the Nash bargaining solution. Social Choice and Welfare 2002, 19, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Multi-Objective Optimization. In Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 197–211. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Deb, K. Multi-objective Optimization. In Search Methodologies; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2014; chapter 15; pp. 403–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, R.T.; Arora, J.S. The weighted sum method for multi-objective optimization: new insights. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 2010, 41, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, R.E. Multiple criteria optimization; theory, computation, and application; John Wiley, 1986; p. 425.

- Kaim, A.; Cord, A.F.; Volk, M. A review of multi-criteria optimization techniques for agricultural land use allocation. Environmental Modelling & Software 2018, 105, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, I.; Lokman, B.; Köksalan, M. Representing the nondominated set in multi-objective mixed-integer programs. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 296, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, T. Route planning for air missions in hostile environments. The Journal of Defense Modeling and Simulation: Applications, Methodology, Technology 2015, 12, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Xiang, X.; Wang, C. Towards Real-Time Path Planning through Deep Reinforcement Learning for a UAV in Dynamic Environments. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2020, 98, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksek, B.; Demirezen, U.M.; Inalhan, G. Development of UCAV Fleet Autonomy by Reinforcement Learning in a Wargame Simulation Environment. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2021 Forum, Reston, Virginia, 1 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alpdemir, M.N. Tactical UAV path optimization under radar threat using deep reinforcement learning. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 5649–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, M.; Yue, L. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Dual-UAV Reconnaissance Mission Planning. Electronics 2022, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.F.; Rădulescu, R.; Bargiacchi, E.; Källström, J.; Macfarlane, M.; Reymond, M.; Verstraeten, T.; Zintgraf, L.M.; Dazeley, R.; Heintz, F.; et al. A practical guide to multi-objective reinforcement learning and planning. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2022, 36, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffaert, K.V.; Nowé, A. Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning using Sets of Pareto Dominating Policies. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 3663–3692. [Google Scholar]

- Vamplew, P.; Yearwood, J.; Dazeley, R.; Berry, A. On the Limitations of Scalarisation for Multi-objective Reinforcement Learning of Pareto Fronts. In AI 2008: Advances in Artificial Intelligence; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008; Vol. 5360, pp. 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, N.D.; Vamplew, P.; Nahavandi, S.; Dazeley, R.; Lim, C.P. A multi-objective deep reinforcement learning framework. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 96, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Fleming, P. Multiobjective optimization and multiple constraint handling with evolutionary algorithms. I. A unified formulation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part A: Systems and Humans 1998, 28, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Tang, K.; Lozano, J.A. Estimation of Distribution Algorithms based Unmanned Aerial Vehicle path planner using a new coordinate system. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE, 7 2014, pp. 1469–1476. [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, J.M.; Besada-Portas, E.; Torre-Cubillo, L.; Andres-Toro, B.; Lopez-Orozco, J.A. Evolutionary path planner for UAVs in realistic environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 10th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, New York, NY, USA, 7 2008; pp. 1477–1484. [CrossRef]

- Besada-Portas, E.; de la Torre, L.; de la Cruz, J.M.; de Andres-Toro, B. Evolutionary Trajectory Planner for Multiple UAVs in Realistic Scenarios. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2010, 26, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogren, P.; Backlund, A.; Harryson, T.; Kristensson, L.; Stensson, P. Autonomous UCAV Strike Missions Using Behavior Control Lyapunov Functions. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference and Exhibit, Reston, Virigina, 8 2006. [CrossRef]

- Kabamba, P.T.; Meerkov, S.M.; Zeitz, F.H. Optimal Path Planning for Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles to Defeat Radar Tracking. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2006, 29, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savkin, A.V.; Huang, H. Optimal Aircraft Planar Navigation in Static Threat Environments. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2017, 53, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A. Probabilistic Path Planning for UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2nd AIAA "Unmanned Unlimited" Conf. and Workshop & Exhibit, Reston, Virigina, 9 2003. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.; Misovec, K.; D’Andrea, R. Low observability path planning for an unmanned air vehicle using mixed integer linear programming. In Proceedings of the 2004 43rd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37601). IEEE, 2004, pp. 3823–3829. [CrossRef]

- Ogren, P.; Winstrand, M. Combining Path Planning and Target Assignment to Minimize Risk in SEAD Missions. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference and Exhibit, Reston, Virigina, 8 2005. [CrossRef]

- Zabarankin, M.; Uryasev, S.; Murphey, R. Aircraft routing under the risk of detection. Naval Research Logistics (NRL) 2006, 53, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C. Handbook of Critical Issues in Goal Programming, 1 ed.; Elsevier, 2014.

- Simon, H.A. On the Concept of Organizational Goal. Administrative Science Quarterly 1964, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review 1956, 63, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Tamiz, M. Practical Goal Programming; Vol. 141, International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, E.L. An assessment of some criticisms of goal programming. Computers & Operations Research 1985, 12, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Tamiz, M. Detection and Restoration of Pareto Inefficiency. In Practical Goal Programming; Hillier, F.S., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2010; Vol. 141, International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, G.B.; Slear, J.N.; Melendez, K. UAV Swarm Mission Planning and Routing using Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Multi-Criteria Decision-Making. IEEE, 4 2007, pp. 10–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhenhua, W.; Weiguo, Z.; Jingping, S.; Ying, H. UAV route planning using Multiobjective Ant Colony System. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems. IEEE, 9 2008, pp. 797–800. [CrossRef]

- Yahia, H.S.; Mohammed, A.S. Path planning optimization in unmanned aerial vehicles using meta-heuristic algorithms: a systematic review. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, X.X.; Zheng, M.Y.; Zhan, Z.H. Evolutionary computation for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning: a survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasdemir, E.; Batta, R.; Köksalan, M.; Tezcaner Öztürk, D. UAV routing for reconnaissance mission: A multi-objective orienteering problem with time-dependent prizes and multiple connections. Computers & Operations Research 2022, 145, 105882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcaner Öztürk, D.; Köksalan, M. Biobjective route planning of an unmanned air vehicle in continuous space. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2023, 168, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, G.Y.; Zang, I. A dual algorithm for the constrained shortest path problem. Networks 1980, 10, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Aguado, J.; Trandafir, P.C. Variants of the ϵ -constraint method for biobjective integer programming problems: application to p-median-cover problems. Mathematical Methods of Operations Research 2018, 87, 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrotas, G. Effective implementation of the ϵ-constraint method in Multi-Objective Mathematical Programming problems. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2009, 213, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Miettinen, K. A Review of Nadir Point Estimation Procedures Using Evolutionary Approaches: A Tale of Dimensionality Reduction. Technical report, 2009.

- Laumanns, M.; Thiele, L.; Zitzler, E. An efficient, adaptive parameter variation scheme for metaheuristics based on the epsilon-constraint method. European Journal of Operational Research 2006, 169, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Ishibuchi, H.; Hirota, K.; Liu, B. Interactive Multiobjective Optimization: A Review of the State-of-the-Art. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 41256–41279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, K.; Ruiz, F.; Wierzbicki, A.P.; Jaszkiewicz, A.; Słowiński, R. Introduction to Multiobjective Optimization: Interactive Approaches. In Multiobjective Optimization, LNCS 5252; Springer-Verlag, 2008; pp. 27–57.

- Dasdemir, E.; Köksalan, M.; Tezcaner Öztürk, D. A flexible reference point-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm: An application to the UAV route planning problem. Computers & Operations Research 2020, 114, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larichev, O.I. Cognitive validity in design of decision-aiding techniques. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis 1992, 1, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, M.; Miettinen, K.; Eskelinen, P.; Ruiz, F. Incorporating preference information in interactive reference point methods for multiobjective optimization. Omega 2009, 37, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechikh, S.; Kessentini, M.; Said, L.B.; Ghédira, K. Preference Incorporation in Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization; 2015; pp. 141–207. [CrossRef]

- Nikulin, Y.; Miettinen, K.; Mäkelä, M.M. A new achievement scalarizing function based on parameterization in multiobjective optimization. OR Spectrum 2012, 34, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Sundar, J. Reference point based multi-objective optimization using evolutionary algorithms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation, New York, NY, USA, 7 2006; pp. 635–642. [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, R.; Li, X.; Branke, J. Reference Point-Based Particle Swarm Optimization Using a Steady-State Approach. In Proceedings of the Simulated Evolution and Learning, 2008, pp. 200–209. [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An Evolutionary Many-Objective Optimization Algorithm Using Reference-Point-Based Nondominated Sorting Approach, Part I: Solving Problems With Box Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2014, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, A.K.A.; Deb, K. PaletteViz: A Visualization Method for Functional Understanding of High-Dimensional Pareto-Optimal Data-Sets to Aid Multi-Criteria Decision Making. IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine 2020, 15, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongrae Kim.; Hespanha, J. Discrete approximations to continuous shortest-path: application to minimum-risk path planning for groups of UAVs. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Decision and Control (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37475). IEEE, 2003, Vol. 2, pp. 1734–1740. [CrossRef]

- Misovec, K.; Inanc, T.; Wohletz, J.; Murray, R. Low-observable nonlinear trajectory generation for unmanned air vehicles. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE International Conference on Decision and Control (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37475). IEEE, 2003, Vol. 3, pp. 3103–3110. [CrossRef]

- Yao-hong Qu.; Quan Pan.; Jian-guo Yan. Flight path planning of UAV based on heuristically search and genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2005. IECON 2005. IEEE, 2005, p. 5 pp. [CrossRef]

- McLain, T.W.; Beard, R.W. Coordination Variables, Coordination Functions, and Cooperative Timing Missions. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2005, 28, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, L.; Xu, F..; Sun, F.; Ding, M. Evolutionary route planner for unmanned air vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2005, 21, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.; Naderhirn, M.; del Re, L. Global real-time path planning for UAVs in uncertain environment. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Computer Aided Control System Design, 2006 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications, 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control. IEEE, 10 2006, pp. 2725–2730. [CrossRef]

- Foo, J.L.; Knutzon, J.; Oliver, J.; Winer, E. Three-Dimensional Path Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Using Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 11th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, Reston, Virigina, 9 2006. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zheng, C.; Yan, P. Route Planning for Unmanned Air Vehicles with Multiple Missions Using an Evolutionary Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Natural Computation (ICNC 2007). IEEE, 2007, pp. 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Jun, X.; Manyi, C.; Ming, X.; Zhike, W. Path planning for UAV based on improved heuristic A∗ algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2009 9th International Conference on Electronic Measurement & Instruments. IEEE, 8 2009, pp. 3–488. [CrossRef]

- Tulum, K.; Durak, U.; Yder, S.K. Situation aware UAV mission route planning. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Aerospace conference. IEEE, 3 2009, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Qianzhi Ma.; Xiujuan Lei. Application of artificial fish school algorithm in UCAV path planning. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Fifth International Conference on Bio-Inspired Computing: Theories and Applications (BIC-TA). IEEE, 9 2010, pp. 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Guo, L. Multiple UAVs Routes Planning Based on Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Symposium on Information Engineering and Electronic Commerce. IEEE, 7 2010, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Chao Zhang.; Zhen, Z.; Daobo Wang.; Meng Li. UAV path planning method based on ant colony optimization. In Proceedings of the 2010 Chinese Control and Decision Conference. IEEE, 5 2010, pp. 3790–3792. [CrossRef]

- Xin Yang.; Ming-yue Ding.; Cheng-ping Zhou. Fast Marine Route Planning for UAV Using Improved Sparse A* Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 Fourth International Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computing. IEEE, 12 2010, pp. 190–193. [CrossRef]

- Yong Bao.; Xiaowei Fu.; Xiaoguang Gao. Path planning for reconnaissance UAV based on Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2010 Second International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Natural Computing. IEEE, 9 2010, pp. 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Kan, E.M.; Lim, M.H.; Yeo, S.P.; Ho, J.S.; Shao, Z. Contour Based Path Planning with B-Spline Trajectory Generation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) over Hostile Terrain. Journal of Intelligent Learning Systems and Applications 2011, 03, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Shiru, Q. Path Planning For Unmanned Air Vehicles Using An Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st Chinese Control Conference, Hefei, China, 2012; pp. 2486–2491.

- Zhou, S.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y. Route Planning for Unmanned Aircraft Based on Ant Colony Optimization and Voronoi Diagram. In Proceedings of the 2012 Second International Conference on Intelligent System Design and Engineering Application. IEEE, 1 2012, pp. 732–735. [CrossRef]

- Holub, J.; Foo, J.L.; Kalivarapu, V.; Winer, E. Three Dimensional Multi-Objective UAV Path Planning Using Digital Pheromone Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference <BR> 20th AIAA/ASME/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference <BR> 14th AIAA, Reston, Virigina, 4 2012. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Wu, W.Y.; Rd, Y.T. Cooperative Electronic Attack for Groups of Unmanned Air Vehicles based on Multi-agent Simulation and Evaluation. International Journal of Computer Science Issues 2012, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Gong, L.; Zhao, C. Unmanned combat aerial vehicles path planning using a novel probability density model based on Artificial Bee Colony algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2013 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Control and Information Processing (ICICIP). IEEE, 6 2013, pp. 620–625. [CrossRef]

- Wallar, A.; Plaku, E.; Sofge, D.A. A planner for autonomous risk-sensitive coverage (PARCov) by a team of unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Swarm Intelligence. IEEE, 12 2014, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Optimal flight path planning for UAVs in 3-D threat environment. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS). IEEE, 5 2014, pp. 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Ji, X.; Li, M.; Li, Y. Route planning method design for UAV under radar ECM scenario. In Proceedings of the 2014 12th International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP). IEEE, 10 2014, pp. 108–114. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, A.; Qi, L. Three-dimensional path planning for UAV based on improved PSO algorithm. In Proceedings of the The 26th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (2014 CCDC). IEEE, 5 2014, pp. 3981–3985. [CrossRef]

- Xiaowei, F.; Xiaoguang, G. Effective Real-Time Unmanned Air Vehicle Path Planning in Presence of Threat Netting. Journal of Aerospace Information Systems 2014, 11, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Zhao, L.; Su, X.; Ma, P. UAV online path planning algorithm in a low altitude dangerous environment. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2015, 2, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xian, Y.; Li, J.; Lei, G.; Chang, Y. UAV Path Planning Based on Chaos Ant Colony Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computer Science and Mechanical Automation (CSMA). IEEE, 10 2015, pp. 81–85. [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, C.; Cobb, R.; Jacques, D.; Reeger, J. Optimal Mission Path for the Uninhabited Loyal Wingman. In Proceedings of the 16th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, Reston, Virginia, 6 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ren Tianzhu.; Zhou Rui.; Xia Jie.; Dong Zhuoning. Three-dimensional path planning of UAV based on an improved A* algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Chinese Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference (CGNCC). IEEE, 8 2016, pp. 140–145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, J. MPC and TGFC for UAV real-time route planning. In Proceedings of the 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC). IEEE, 7 2017, pp. 6847–6850. [CrossRef]

- Jing-Lin, H.; Xiu-Xia, S.; Ri, L.; Xiong-Feng, D.; Mao-Long, L. UAV real-time route planning based on multi-optimized RRT algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2017 29th Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC). IEEE, 5 2017, pp. 837–842. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y. Quantitative Evaluation of Voronoi Graph Search Algorithm in UAV Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS). IEEE, 11 2018, pp. 563–567. [CrossRef]

- Maoquan, L.; Yunfei, Z.; Shihao, L. The Gradational Route Planning for Aircraft Stealth Penetration Based on Genetic Algorithm and Sparse A-Star Algorithm. MATEC Web of Conferences 2018, 151, 04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danancier, K.; Ruvio, D.; Sung, I.; Nielsen, P. Comparison of Path Planning Algorithms for an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Deployment Under Threats. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 1978–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S. Flight Parameter Model Based Route Planning Method of UAV Using Stepped-Adaptive Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics (ICCAR). IEEE, 4 2019, pp. 524–530. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. Improvement of UAV Track Trajectory Algorithm Based on Ant Colony Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data & Smart City (ICITBS). IEEE, 1 2019, pp. 28–31. [CrossRef]

- Patley, A.; Bhatt, A.; Maity, A.; Das, K.; Ranjan Kumar, S. Modified Particle Swarm Optimization based Path Planning for Multi-Uav Formation. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, Reston, Virginia, 1 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H. A Fast path re-planning method for UAV based on improved A* algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE, 11 2020, pp. 462–467. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. A Novel Real-Time Penetration Path Planning Algorithm for Stealth UAV in 3D Complex Dynamic Environment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 122757–122771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, X.; Luo, Y.; Leng, S. An Improved Fast Convergent Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning in Battlefield Environment. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Control & Automation (ICCA). IEEE, 10 2020, pp. 360–365. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xin, B.; Guo, M.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H. Multi-UAV 3D Path Planning in Simultaneous Attack. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Control & Automation (ICCA). IEEE, 10 2020, pp. 500–505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. Rapid Penetration Path Planning Method for Stealth UAV in Complex Environment with BB Threats. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2020, 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gao, F.; Fang, X.; Lan, Z. Improved Bat Algorithm for UAV Path Planning in Three-Dimensional Space. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 20100–20116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Zhang, D.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X. Multi-UAV cooperative Route planning based on decision variables and improved genetic algorithm. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1941, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, A. Path Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Using a Mix-Strategy-Based Gravitational Search Algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 57033–57045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, L.; Ning, Z.; Qiang, L. UAV Path Planning Based on an Improved Ant Colony Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems (ICoIAS). IEEE, 5 2021, pp. 357–360. [CrossRef]

- Leng, S.; Sun, H. UAV Path Planning in 3D Complex Environments Using Genetic Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC). IEEE, 5 2021, pp. 1324–1330. [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.W.; Choi, Y.S.; An, J.Y.; Kim, C.J. An Approach to Air-to-Surface Mission Planner on 3D Environments for an Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle. Drones 2022, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Dai, J.; Ying, J. Distributed multi-UAV cooperation for path planning by an NTVPSO-ADE algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 41st Chinese Control Conference (CCC). IEEE, 7 2022, pp. 5973–5978. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Dai, J.; He, C. Optimal path planning with modified A-Star algorithm for stealth unmanned aerial vehicles in 3D network radar environment. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2022, 236, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X. Efficient and optimal penetration path planning for stealth unmanned aerial vehicle using minimal radar cross-section tactics and modified A-Star algorithm. ISA Transactions 2023, 134, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Liang, Q.; Li, H. UAV penetration mission path planning based on improved holonic particle swarm optimization. Journal of Systems Engineering and Electronics 2023, 34, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Year | OA | RR | OM | C | PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al. [14] | 2018 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Song et al. [12] | 2019 | ✓ | ∼ | ∼ | ∼ | ∼ |

| Aggarwal & Kumar [9] | 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Saadi et al. [13] | 2022 | ✓ | ✗ | ∼ | ∼ | ✗ |

| Jones et al. [10] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Significant contribution to research ( Average yearly citations ≥ 1) |

Low academic impact (Average yearly citations < 1) |

| Threat as optimization objective | Completely avoid or ignore threats |

| Handle multiple objectives | Sole Focus on Threat or Distance minimization |

| Route planning in the flight domain | No route planning or different domain |

| Sufficient explanation of methodology | No details |

| Propose novel work | Minor change from existing work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).