1. Introduction

Laser devices are an intrinsic part of modern technology, being used in many industrial, military, and community settings. Most of us encounter lasers daily. After all, such devices are key components of daily life involved in everything from automatic doors, bar code scanners, surgical medical devices, to holiday home decorations. It is common then to have chance community exposures to laser light from such devices, and—while annoying—they typically cause no ocular damage [

1]. Perhaps the most ubiquitous lasers are in the form of laser pointers. These laser pointers are hung on keychains for personal use, used by teachers in classrooms, and can be found in many homes as toys for pets [

1,

2]. Unfortunately, they can then be used by pranksters—adult and children alike—to intentionally expose co-workers, friends, or classmates. These exposures can be more than annoying, as they can also induce fear and even anger [

3]. Some of this fear is rational, as the point source light from these lasers is focused by the anterior structures of the eye (i.e., cornea and lens) and absorbed by the retina [

4]. This results in a perceived brightness that far exceeds more common community exposures [

1,

3,

4]. There also seems to be a complex social or emotional component to these experiences [

3] which may be exacerbated in those with emotional or psychiatric disturbances [

2,

3,

5]. This creates both public health and personal medical concerns, as laser devices—easily purchased online and often unregulated—can make their way into the hands of both children and young adults [

2,

4,

5]. This commercial availability of laser pointers and other devices has preceded an increased incidence of retinal laser injuries [

6], with laser pointers responsible for many of these [

7].

An even greater health concern results from the at-home use of more powerful laser devices used for cosmetic purposes [

5,

8,

9]. Due to the worldwide popularity of tattoos [

10] and the desire of many to have them removed [

11], there is a need for a safe and effective technique that results in healthy skin and good cosmesis [

12,

13]. Unfortunately, in-office tattoo removal can be painful, expensive, time-consuming, and inconvenient [

14]. Patients often then turn to high-energy at home devices to self-perform these procedures [

14]. One such device is the at-home laser tattoo removal device, which is based on the current gold standard in-office yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) laser [

15]. These devices deliver short invisible infrared (IR; 1064 nm), high-energy pulses that target and remove pigment from under the skin. These lasers are also frequency-doubled, meaning they contain a second wavelength (i.e., 532 nm) which is visible to the human eye. Both wavelengths (i.e., 532 and 1064 nm) are transmitted by the cornea, lens, and vitreous body and are absorbed by the retina [

16]. As the goal of these tattoo removal lasers is to be absorbed by pigment, there is significant risk to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) or the choroid [

17]. This is particularly the case if the light is intentionally viewed [

18].

The following is a report of one such injury. An adult male experienced retinal damage while attempting tattoo removal with an at-home laser device. While he self-reported a childhood history of solar gazing, persistent questioning revealed a more recent history of a self-inflicted laser injury. These conditions (i.e., laser and solar retinopathy) can masquerade as each other, and thorough case history was essential to differentiating the two conditions [

3]. In addition, etiologically distinguishing characteristics of laser retinal damage were present, including foveal involvement, gray-white or yellow-white retinal lesions, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and/or photoreceptor disruption on optical coherence tomography (OCT). We present the patient history, clinical findings, imaging, and differentials used to arrive at the diagnosis.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Patient History

A 33-year-old male presented to the Eye and Vision Care Clinic at Rosenberg School of Optometry for a comprehensive eye examination. The chief complaint was mild blurry vision in both eyes (OU) at distance with two-year-old habitual spectacles. He also reported a constant "white spot” visually in the right eye (OD) which started two years ago. The patient was seen for an eye examination 16 months prior, during which he reported an ocular laser exposure to both eyes while self-removing a tattoo from his right temple for the purpose of employment. However, no significant retinal findings were recorded at that time. Present and pertinent medical history includes diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and schizophrenia. Quetiapine fumarate 300 mg, prazosin hydrochloride 1 mg, and risperidone 2 mg were all taken twice daily as prescribed for these conditions.

2.2. Clinical Findings

Entering visual acuities (VA) were 20/20 OD, 20/30-2 left eye (OS; 20/20-1 with pinhole) at distance. All other entrance testing (e.g., pupils, extraocular motilities, and confrontation fields via finger count) were within normal limits (WNL). Best-corrected visual acuities improved with refraction OS to 20/20-1. During the refraction, the patient stated that he was experiencing visual white spots both monocularly and binocularly. He further described intact central vision with scotomas to the left and right of fixation in each eye.

External examination revealed a large (1”x 3”) multi-colored scar on his right temple, which was consistent with the history of tattoo removal. Slit lamp examination (SLE) was WNL. Dilated fundus exam (DFE) revealed subtle epiretinal membranes (ERM) and pigment mottling of both maculae. Foveal light reflexes were present but faint, and small, single, yellow white parafoveal lesions were present in each eye. Optic nerve heads (ONH) were tilted in both eyes with mild temporal sectoral atrophy, but no retinal nerve fiber layer defects were noted clinically. Cup to disc ratios were 0.50 round OD and 0.55 round OS. During the DFE, the patient was asked about sun-gazing behaviors, and he reported that he did so as a child.

2.3. Advanced Imaging (OCT)

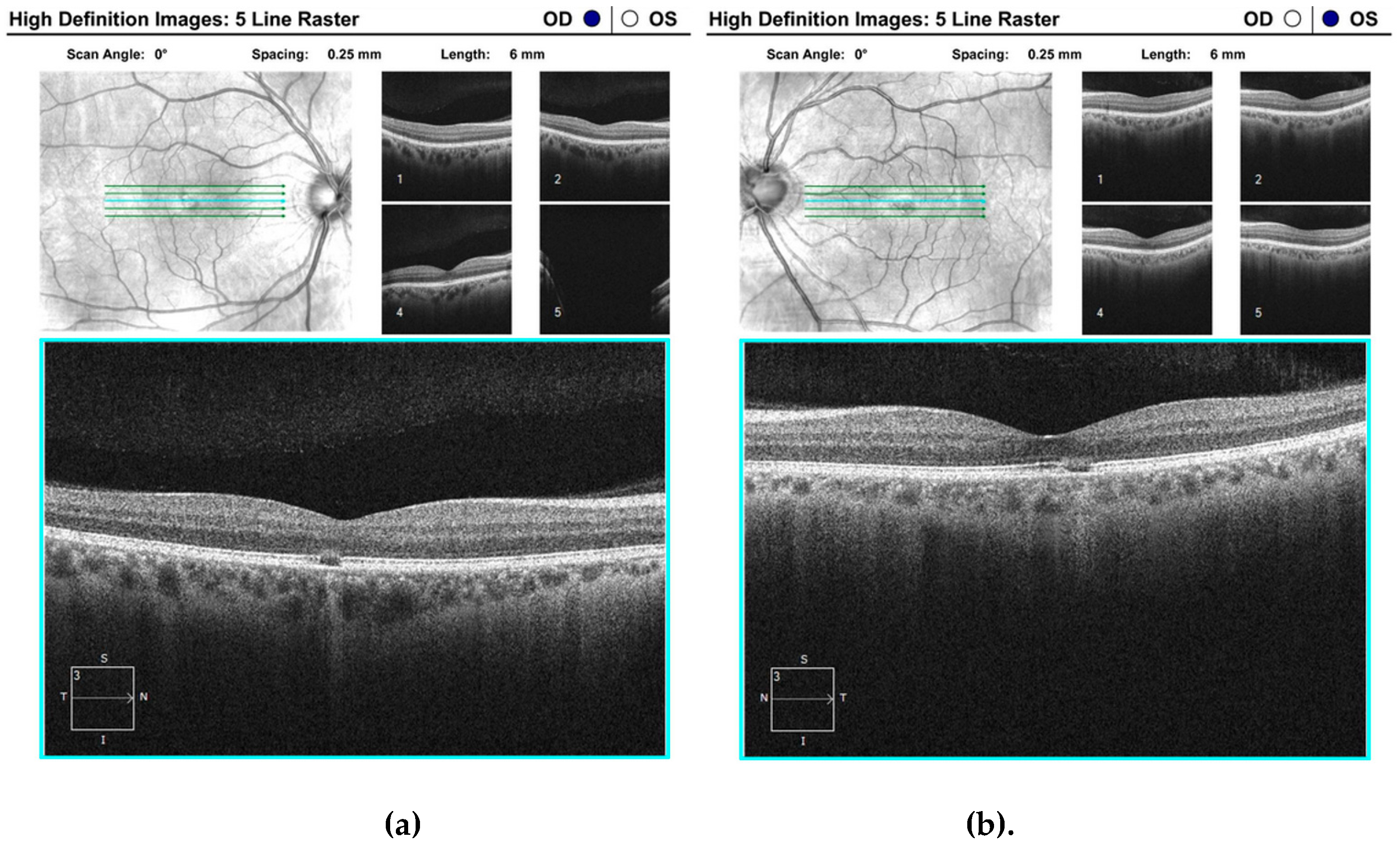

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the macula OU was ordered, and the results of the 5-line raster scan revealed parafoveal focal destruction of the RPE layer in each eye with disruption of the overlying photoreceptor outer segments (

Figure 1). The damage was superior temporal to the fovea in the right eye and inferior temporal in the left eye, which correlate with the patient's reports of bilateral fixation scotomas.

2.3. Differential Diagnoses

While laser retinopathy can lead to secondary full or partial thickness macular holes, neither were observed and—as traction forces were not observed on either retina—macular holes were ruled out in this case [

19]. Macular dystrophies such as Best and Stargardt disease were ruled out since best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was not significantly reduced, and elevated yellow lesions and/or bull’s eye maculopathy were not present in our case [

20]. Lastly, POHS was discounted since the present patient lesions were not choroidal in nature.

2.4. Diagnosis

Solar retinopathy was the initial working diagnosis due to the patient’s report of childhood sun-gazing and bilateral presentation of retinal trauma [

21,

22]. However, solar retinopathy characteristically presents with symmetrical on-foveal damage [

22]. The patient’s retinal damage was asymmetric, parafoveal, and presumably would have been reported during the previous exam had the damage been longstanding from childhood. As a result, the diagnosis of solar retinopathy was no longer appropriate. Upon further questioning regarding laser exposure, the patient admitted that he intentionally used a tattoo removal laser and inadvertently exposed his eyes during what he described as a “manic schizophrenic episode” two years prior. Subsequently, the patient was diagnosed with laser induced retinopathy OS>OD, without retinal breaks, holes, or choroidal neovascularization. To address the patient’s chief complaint of blurry vision, he was also diagnosed with compound myopic astigmatism OD and OS.

2.5. Plan

While the consequences here were relatively mild, self-injury would typically require a referral for behavioral management [

18]. However, he was already receiving that care with Veterans Affairs. Our plan for the laser retinopathy OU was to monitor for changes with annual exams and for the patient to return to clinic sooner with any change or increase in symptoms. As best-corrected visual acuity improved slightly with refraction, we also prescribed new spectacles.

3. Discussion

3.1. Case Summary

We present the findings of a case of self-inflicted laser retinopathy. The current case was clinically very subtle, and it was only confirmed after continuous and comprehensive history as well as advanced retinal imaging via optical coherence tomography (OCT). Causes of similar laser injury range from simple pranks, occupational exposures, curiosity, and carelessness to intentional exposures due to emotional or behavioral disturbances [

3,

23,

24]. Regardless of the cause of the injury, their assessment can challenge primary care physicians and eye care providers alike. We further briefly discuss laser mechanisms as well as an evidence-based approach to the diagnosis and considerations when managing laser injuries.

3.2. Notable Findings

The most common characteristics of laser retinopathy are unilateral or bilateral central or paracentral scotomas and decreased vision [

3]. The retina is particularly vulnerable to the photocoagulation damage produced by laser devices. Acute etiologies often present with a complaint of reduced visual acuity (VA) with a wide range of variability based on the power and length of exposure. Although testing with an Amsler grid could be used to screen any patient that presents with a recent laser incident for the presence of scotomas, OCT measurements of the macula, fundus appearance, and history of laser exposure should be used to establish final diagnosis. Laser damage to the retina can manifest with several different appearances from hypertrophy of the RPE to serous chorioretinopathy, as well as retinal hemorrhages, choroidal neovascularization, and macular holes [

25]. One notable difference between the present case and previous reports is that laser induced injuries are often focal with accidental laser exposures, while streak lesions are more often associated with self-inflicted traumas [

26,

27]. We would then have expected the lesions in our patient to be streak lesions, rather than the observed focal lesions in both eyes. However, our case is further

consistent with previous studies showing that 50% of intentional incidents involving individuals older than 16 years of age were in patients with co-existing mental disturbances or illnesses [

9].

3.3. Laser Summary

While brief laser exposures are not always vision-threatening [

28] and can even be classified as “safe” [

6], laser radiation can damage the retina through multiple mechanisms [

4,

29]. In this case, however, the patient used a pulse fired frequency-doubled 1064 nm (i.e., contains both visible 564 nm and IR 1064 nm light) Nd-YAG laser with the primary medical or cosmetic use of penetrating deep into skin to interact with melanocytes [

8]. Viewing the light from such devices correlates with a high risk for damage, particularly causing focal RPE destruction [

29]. After all, as such devices target the pigment molecules in tattoo ink, they also target the pigment in the RPE layer exciting the molecules and breaking down the cells [

3,

8]. Laser devices are regulated in the United States by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) and categorized based on characteristics such as power output, spot size, duration, and whether they are pulsed or continuous [

30,

31]. As a rule, Class I lasers are completely eye safe (regardless of the duration) and Class IV lasers should never be viewed (regardless of duration)—without eye protection that filters out the produced wavelengths. While the patient was not completely sure of the specific laser brand used, most tattoo removal lasers are Q-switched Class II lasers which are not usually harmful to ocular structures if the proper eye protection is worn or if the exposure is incidental [

32]. However, Q-switching refers to the technique that produces a pulsed-beam [33

]. Pulsed beams contain very high peak energy levels (compared to continuous laser output) that can cause ocular damage within 0.25 seconds (the well-established speed of the human blink reflex [

34]). Consequently, the output light from these devices should never be viewed intentionally, especially at close range.

3.4. Further Considerations

Self-inflicted cases of laser retinopathy are the most likely to cause legal blindness due to the lengthy exposure of intentional viewing [

5]. Fortunately, the current patient was only experiencing minimal visual acuity loss and other disturbances (i.e., “white spots”). However, he was at first reluctant to reveal that the injury was self-inflicted. This ties into the suggestion that laser injuries—particularly when self-inflicted—are oft unreported [

5]. Reasons for underreporting vary, but it is important to at least mention non-organic vision loss in the work-up of patients with alleged laser injuries. That is, patients may use lasers to injure themselves for financial gain [

35] or to simply assume a “sick role” [

26]. This does not appear to be the case in our patient who was ultimately forthcoming about the self-injury when questioned throughout the exam. There is applicability, though limited, of these concerns to the current case. However, as a review of functional vision loss is beyond the scope of the current report, we leave it to the reader to examine previous reports for further context and examination techniques in patients with non-organic vision loss [

3,

36,

37].

4. Conclusions

This case features the need for and value of an evidence-based (i.e., non-speculative) approach to the diagnosis of self-inflected laser retinopathy. Our approach specifically highlights the need for a thorough and continuous history throughout the examination as well as the need for detailed retinal imaging. While the patient mentioned paracentral visual loss or "white spots" as his chief complaint, his distance visual acuity was relatively normal. Upon additional detailed history and dilated fundus evaluation, more information was obtained regarding his specific laser exposure incident. Furthermore, high resolution OCT is extremely valuable in such cases to determine location and extent of damage in individuals who otherwise have minimal visual acuity impact. Lastly, this report highlights the need for both public health interventions and patient education in the areas of laser safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.S. and F.M.S.; resources, B.K.F.; data curation, J.R.S. and F.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.F. and F.M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.R.S., B.K.F., and F.M.S.; supervision, B.K.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Managing retinal injuries from lasers. Available online: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/managing-retinal-injuries-from-lasers (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Alsulaiman, S.M.; Ghazi, N.G. A case of recurrent, self-inflicted handheld laser retinopathy. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2016, 20, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainster, M.A.; Stuck, B.E.; Brown, J. Assessment of Alleged Retinal Laser Injuries. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2004, 122, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellerio, J. Light effects on the retina. In: Albert, D.M.; Jakobiec, F.A., eds. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Vol 1. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1994, 1326-1345.

- Simonett, J.M.; Shakoor, A.; Bernstein, P.S. Intentional retinal injury with handheld lasers is an underrecognized form of self-harm. J. Affect. Dis. 2021, 281, 503–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliney, D.H.; Dennis, J.E. Safety concerns about laser pointers. J. Laser Applications 1994, 6, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffendorf, J.E.; Hildebrand, G.D.; Downes, S.M. Handheld laser devices and laser-induced retinopathy (LIR) in children: an overview of the literature. Eye (Lond). 2019, 33, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, K.M.; Graber, E.M. Laser Tattoo Removal: A Review. Derm. Surg. 2012, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, K.V.; Michel, Z.; Greenwald, M.F.; Cunningham, E.T.; Freund, K.B. Retinal injury from hand-held lasers: A review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 66, 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, N.; Seite, S.; Taieb, C. The prevalence of tattooing and motivations in five major countries over the world. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol, 2019, 33, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klugl, I.; Hiller, K.A.; Landthaler, M.; Baumler, W. Incidence of health problems associated with tattooed skin: a nation-wide survey in German-speaking countries. Dermatology 2010, 221, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, W.; Breu, C.; Philipp, B.; Haslböck, B.; Berneburg, M.; Weiß, K.T. The efficacy and the adverse reactions of laser-assisted tattoo removal – a prospective split study using nanosecond and picosecond lasers. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, W.; Weiß, K.T. Laser assisted tattoo removal - state of the art and new developments. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, D.P.; Vineet, M.; Buckley, S. Keloidal scarring from the at-home use of intense pulsed light for tattoo removal. Derm. Surg. 2017, 43, 1112–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton Carlsen, K.; Esmann, J.; Serup, J. Tattoo removal by Q-switched yttrium aluminum garnet laser: client satisfaction. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boettner, E.A.; Wolter, J.R. Transmission of the ocular media. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1962, 1, 776–783. [Google Scholar]

- Barkana, Y.; Belkin, M. Laser eye injuries. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000, 44, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, N. Self-inflicted eye injuries: a review. Eye 2004, 18, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, M.; Wilkinson, M. EyeRounds.org: Laser pointer maculopathy. Available online: https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/311-laser-pointer-maculopathy.htm (accessed on Mar 23, 2023).

- Battaglia Parodi, M.; Iacono, P.; Romano, F.; Bolognesi, G.; Fasce, F.; Bandello, F. Optical Coherence Tomography in Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 27, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Jansen, M.E.; Andrade, J.; Chui, T.Y.P.; Do, A.T.; Rosen, R.B.; Deobhakta, A. Acute solar retinopathy imaged with adaptive optics, optical coherence tomography angiography, and en face optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.M.; Mostafa, E.M.; Anber, M.A.; El Saman, I.S.; Eldawla, M.E. Solar maculopathy: prognosis over one year follow up. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, B.E.; Zwick, H.; Lund, B.J.; Scales, D.K. Accidental human retinal injuries by laser exposure: Implications to laser safety. Int. Laser Safety Conference Proc. 1997, 3, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonett, J.M.; Scarinci, F.; Labriola, L.T.; Jampol, L.M.; Goldstein, D.A.; Fawzi, A.A. A case of recurrent, self-inflicted handheld laser retinopathy. J. AAPOS. 2016, 20, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba-Linero, C.; Rocha de Lossada, C.; Rodriguez Calvo de Mora, M.; Nieves de las Rivas, R.; Hernando Ayala, C. Laser light retinopathy. Romanian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 63, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiolo, A.; Sacconi, R.; Giuffrè, C.; Corbelli, E.; Carnevali, A.; Querques, L.; Sarraf, D.; Freund, K.B.; Sadda, S.; Bandello, F.; Querques, G. Self-inflicted laser handheld maculopathy: a novel ocular manifestation of factitious disorder. Retin. Cases Brief. Rep. 2018, 12, S46–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtel, J.; Harmening, W.M.; Krohne, T.U.; Holz, F.G.; Charbel Issa, P.; Herrmann, P. Retinal Injury Following Laser Pointer Exposure. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainster, M.A. Blinded by the light--not! Arch. Ophthalmol. 1999, 117, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glickman, R.D. Phototoxicity to the Retina: Mechanisms of Damage. Int. J. Toxicol. 2002, 21, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainster, M.A.; White, T.J.; Allen, R.G. Spectral dependence of retinal damage produced by intense light sources. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1970, 60, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainster, M.A. Decreasing retinal photocoagulation damage: principles and techniques. Semin. Ophthalmol. 1999, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/home-business-and-entertainment-products/laser-products-and-instruments (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Früngel, F.B.A. K – Light flash production from a capacitive energy storage. In: Früngel, F.B.A , ed. Optical Pulses - Lasers - Measuring Techniques. Academic Press. 1965, p. 192. [CrossRef]

- Zuclich, J.A.; Stolarski, D.J. Retinal damage induced by red diode laser. Health Phys. 2001, 81, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, J.L.; May, W.M.; Johnson, C.A.; Post, R.B. The California Syndrome: Functional visual complaints with potential economic impact. Ophthalmology 1985, 92, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahle, M.; Mohn, G. Assessment of visual function in suspected ocular malingering. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1989;73:651-654. [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.J. Threshold perimetry of each eye with both eyes open in patients with monocular functional (nonorganic) and organic vision loss. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 125, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).