Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

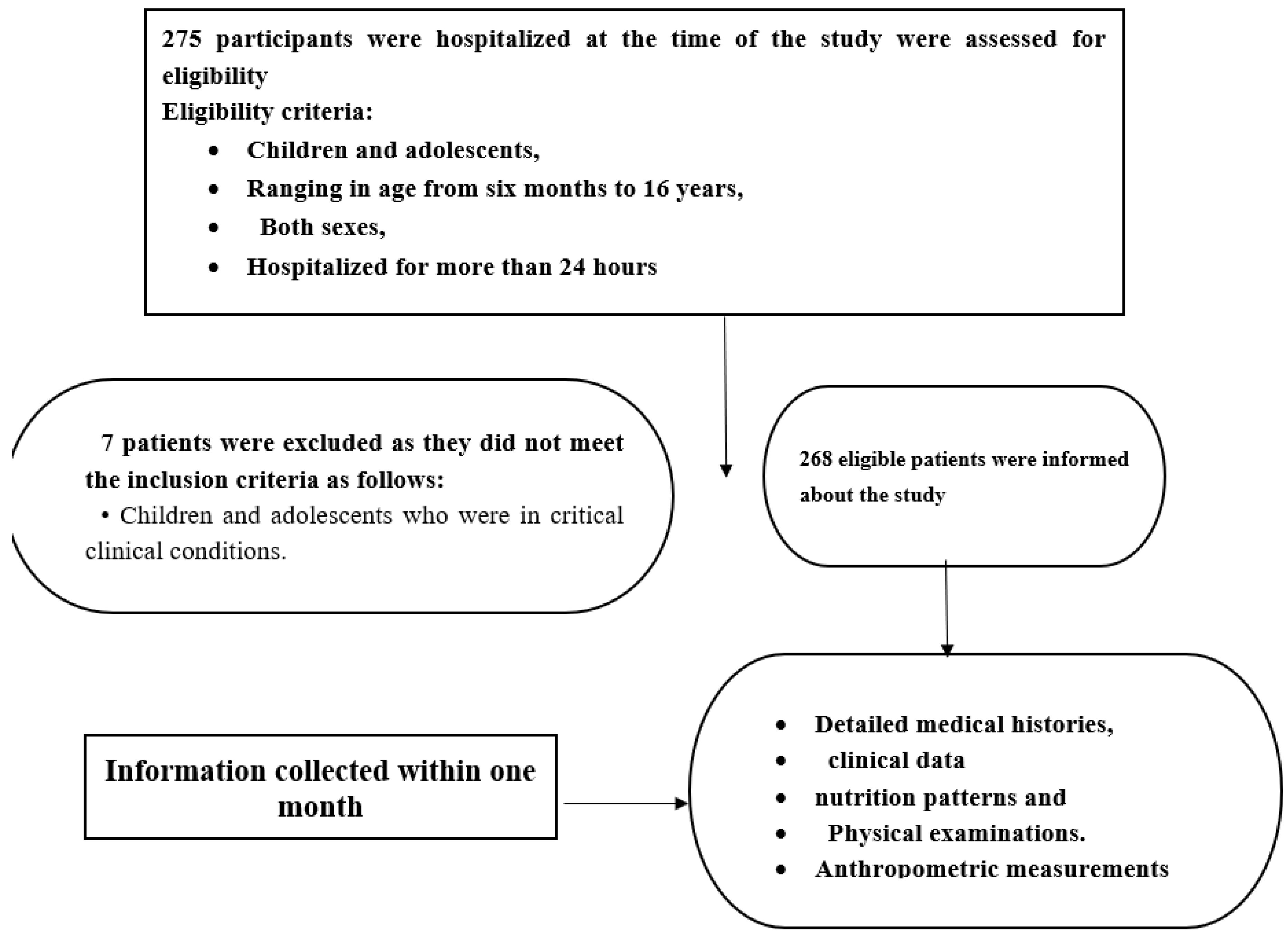

Background: Child development is multifaceted and depends on various elements including diet, genetic makeup, environmental conditions, and exposure to infections. Proper nutrition significantly impacts a child’s capacity to manage and recover from illness. Thus, evaluating nutritional health is a fundamental aspect of pediatric healthcare. Objective: The current study assesses the nutritional status of hospitalized children and adolescents by analyzing growth parameters related to age, weight, height, and gender, identifying disparities , and determining influencing risk factors. Methods: A single-center cross-sectional study was conducted at Mohamed El-Alamin Hamed Hospital for children in Khartoum-Sudan. The study focused on children and adolescents aged six months to 16 years who were hospitalized for over 24 hours, excluding those in critical conditions, selected by purposive sampling. Caregivers were interviewed after consent was obtained, with data collected through detailed medical histories, physical examination, and a specialized questionnaire. Results: Two hundred sixty-eight subjects were enrolled in this study. Among them, males accounted for 146 (54.5%), with a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1. A total of 199 (74.2%) of the subjects had a height/length for age >-2 z-score (normal), 49 (18.3%) had a <-3 z-score (severe stunting), whereas 20 (7.4%) had -3 to -2 z-score (moderate stunting). Sixteen (6.0%) children were classified as weighing 1+ to +2 SD (overweight), and 14 (5.2%) were >+3 SD (obese). Regarding nutrition status, 161 (60%) had normal malnutrition, 32 (11.9%) had moderate wasting, and 45 (16.8%) had severe wasting. Grade 2 edema was observed in four (8.9%) children, and only three (9.4%) had grade 3 edema. Malnutrition risk factors significantly correlated with the female gender, hospital admission rate, and the absence of exclusive breastfeeding (p<0.001). Conclusion: The study reveals critical insight into pediatric nutritional health. A notable prevalence of stunting and acute malnutrition was observed, particularly among the youngest age groups, with a higher frequency of stunting in males. Severe acute malnutrition and muscle wasting were more common among females, while overweight and obesity were prevalent in children aged 5-10 years. The findings underscore the importance of early nutritional interventions, especially considering the significant correlation found between malnutrition risk factors and variables such as age, gender, hospital admission rate, and exclusive breastfeeding.

Keywords:

Introduction

Importance of Nutritional Assessment and Growth Monitoring in Pediatric Care

Key indices and Their Implications for Assessing Child Nutrition

Role of Nutritional Intervention and a Balanced Diet in Pediatric Care

Study Rationale

Current Research Questions to Address the Gaps

- What is the prevalence of undernutrition among hospitalized children and adolescents?

- What specific growth charts are used in growth screening for pediatric nutritional assessment?

- What potential risk factors may affect the anthropometric measurements of hospitalized children and adolescents?

Aims and Objectives

Ethical Approval

Materials and methods

Study Setting

Study Criteria

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

Results

General Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Prevalence of stunting among hospitalized children and adolescents

Prevalence of Malnutrition Among Hospitalized Children and Adolescents Using MUAC Measurements

Gender Differences in Anthropometric Measurements

Relationship Between Child Health Variables and Malnutrition Risk Factors

Discussion

Prevalence of Stunting Among Hospitalized Children and Adolescents

Prevalence of Wasting and Overnutrition Among Hospitalized Children and Adolescents

Prevalence of Malnutrition Among Hospitalized Children And Adolescents Using MUAC Measurements

Relationship Between Child Health Variables and Malnutrition Risk Factors

Study Limitation

Conclusion

Funding

Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| URTI | Upper Respiratory Tract Infection |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| GAM | Global Acute Malnutrition |

| HAZ | Height-for-age Z-score |

| HIV | Human Immune Deficiency Virus |

| IRB | Institute Review Board |

| MAM | Moderate Acute Malnutrition |

| MDGs | Millennium Development Goals |

| MUAC | Mid-Upper Arm Circumference |

| SAM | Severe Acute Malnutrition |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund |

| WHZ | Weight-for-height Z-score |

Author’s contribution

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| Relevant studies↓ | Study setting | Study design | Country | Number of patients |

Stunting/ chronic malnutrition |

Wasting/ acute malnutrition |

MUAC | Overnutrition | |||||

|

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Overweight (%) |

Obesity (%) |

||||||

| Current study, Elgadal et al., 2023 (Unpublished) | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Sudan | 268 | 18.3 | 7.5 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 15.3 |

6.0 | 6.0 | 5.2 | |

| Choy C.C. et al., 2023 |

Ola Tuputupua’e “Growing Up” in Samoa project | Mixed longitudinal cohort study | Samoa | 437 | Overall stunting: 1.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Overall overweight/obesity: 36.2 | |||

| Fouad H.M. et al., 2023 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Egypt | 505 | Overall stunting: 3.0 | Overall wasting: 6.6 | NA | NA | 8.5 | 2.4 | |||

| Danso F. et al., 2023 | CWC | Cross-sectional study | Ghana | 240 | Overall stunting: 12.5 | Overall wasting: 27.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Habimana J.D. et al., 2023 | Rwanda CFSVA | Cross-sectional study | Rwanda |

817 | Overall stunting: 34.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Saengnipanthkul S. et al., 2023 | Hospital-based study | Prospective cohort study | Thailand | 816 | Overall stunting: 23.6 | Overall wasting: 14.3 | NA | NA | 11.3 | 3.8 | |||

| Relevant studies↓ | Study setting | Study design | Country | Number of patients |

Stunting/ chronic malnutrition |

Wasting/ acute malnutrition |

MUAC | Overnutrition | |||||

|

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Overweight (%) |

Obesity (%) |

||||||

| Current study, Elgadal et al., 2023 (Unpublished) | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Sudan | 268 | 18.3 | 7.5 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 15.3 |

6.0 | 6.0 | 5.2 | |

| Siddiqa M. et al., 2023 | PDHS | Cross-sectional study | Pakistan | 4226 | Overall stunting: 37.7 | Overall wasting: 8.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Mengesha, A. et al. | South Ethiopia | Overall stunting: 37.7 | |||||||||||

| Al-Waleedi A.A. et al., 2022 | Multi-center hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Yemen | 951 | Overall stunting: 41.3 | 6.2 | 15.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Inoue A. et al., 2022 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Nepal | 426 | 4.7 (at admission), 5.2 (at discharge) | 14.3 (at admission), 14.8 (at discharge) | 2.6 (at admission), 2.8 (at discharge) | 6.6 (at admission), 5.6 (at discharge) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Suryana Y.F. et al., 2021 | Community-based survey | Cross-sectional study | Indonesia | 81 | Overall stunting: 49.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Relevant studies↓ | Study setting | Study design | Country | Number of patients |

Stunting/ chronic malnutrition |

Wasting/ acute malnutrition |

MUAC | Overnutrition | |||||

|

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Overweight (%) |

Obesity (%) |

||||||

| Current study, Elgadal et al., 2023 (Unpublished) | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Sudan | 268 | 18.3 | 7.5 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 15.3 |

6.0 | 6.0 | 5.2 | |

| Chataut J. et al., 2020 | Community-based survey | Cross-sectional study | Nepal | 302 | Overall stunting: 37.5 | Overall wasting: 14.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Tekile A.K. et al., 2019 | EDHS | Cross-sectional study | Ethiopia | 9495 | Overall stunting: 38.3 | Overall wasting: 10.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Dehghani S.M. et al., 2018 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 430 | Overall stunting: 48.5 | Overall wasting: 47.0 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 10.0 | Obese: 16.0 Severe obese: 1.0 |

|||

| Lee W.S. et al., 2017 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Malaysia | 285 | Overall stunting: 14.0 | Overall wasting: 11.0 | 2.0 | 5.3 | NA | NA | |||

| Rachmi C.N. et al., 2016 | IFLS | Longitudinal survey | Indonesia | 4101 | Overall stunting: 1993 (wave 1): 2084 (50.8) 1997 (wave 2): 1994 (48.6) 2000 (wave 3): 1838 (44.8) 2007 (wave 4): 1506 (36.7) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | At risk of overweight and overweight/obese 1993 (wave 1): 423 (10.3) 1997 (wave 2): 435 (10.6) 2000 (wave 3): 480 (11.7) 2007 (wave 4): 677 (16.5) |

|||

| Relevant studies↓ | Study setting | Study design | Country | Number of patients |

Stunting/ chronic malnutrition |

Wasting/ acute malnutrition |

MUAC | Overnutrition | ||||||

|

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Overweight (%) |

Obesity (%) |

|||||||

| Current study, Elgadal et al., 2023 (Unpublished) | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Sudan | 268 | 18.3 | 7.5 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 15.3 |

6.0 | 6.0 | 5.2 | ||

| Veghari G. et al., 2016 | Community-based survey | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 7575 | Overall stunting: 1998: 32.8 2004: 13.4 2013: 15.7 |

NA | NA | NA | NA | 1998: 8.5 2004: 3.3 2013: 5.2 |

1998: 4.6 2004: 1.2 2013: 3.5 |

|||

| Juma O.A. et al., 2016 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Tanzania | 63237 | Overall stunting: 8.37 |

Overall wasting: 1.41 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Pileggi V.N. et al., 2016 | Hospital-based study | Cross-sectional study | Brazil | 292 | NA | NA | Overall wasting: 16.1 | NA | NA | 19.17 | NA | |||

| Laghari Z. A. et al., 2015 | Community-based survey | Cross-sectional study | Pakistan | 511 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.2 | 12.7 | NA | NA | ||

References

- Herrera Cuenca, M., Proaño, G. V., Blankenship, J., Cano-Gutierrez, C., Chew, S. T. H., Fracassi, P., Keller, H., Venkatesh Mannar, M. G., Mastrilli, V., Milewska, M., & Steiber, A. (2020). Building Global Nutrition Policies in health care: Insights for tackling malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2019 Global Nutrition Research and policy forum. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(8), 1407–1416. [CrossRef]

- Nutrition [Internet]. Who.int. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/topics/nutrition/en.

- Azzouz, J. Z., Safdar, O. Y., Awaleh, F. I., Khoja, A. A., Alattas, A. A., & Jawhari, A. A. (2021). Nutritional assessment and management in paediatric chronic kidney disease. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2021, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, H., Dixon, M., Crabtree, I., Eaton-Evans, M. J., & McNulty, H. (2012). The development and evaluation of the screening tool for the assessment of malnutrition in paediatrics (stamp©) for use by Healthcare staff. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 25(4), 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. J., Wiskin, A. E., Pearson, F., Beattie, R. M., & Leaf, A. A. (2014). How to use: Nutritional assessment in neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Education & Practice Edition, 100(3), 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Use and interpretation of the WHO and CDC Growth Charts for children from birth to 20 years in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106996.

- Sissaoui, S., De Luca, A., Piloquet, H., Guimber, D., Colomb, V., Peretti, N., Bouniol, A., Breton, A., Chouraqui, J.-P., Coste, M.-E., Djeddi, D., Dorigny, B., Goulet, O., Gottrand, F., Hermouet, P., Lambe, C., Leke, A., Leprince, S., Mas, E., … Hankard, R. (2013). Large scale nutritional status assessment in pediatric hospitals. E-SPEN Journal, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Fufa, D. A., & Laloto, T. D. (2021). Factors associated with undernutrition among children aged between 6–36 months in Semien Bench District, Ethiopia. Heliyon, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Larson-Nath, C., & Goday, P. (2019). Malnutrition in children with chronic disease. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 34(3), 349–358. [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V., Soliman, A., Alaaraj, N., Ahmed, S., Alyafei, F. ., & Hamed, N. (2021). Early and Long-term Consequences of Nutritional Stunting: From Childhood to Adulthood: Early and Long-term Consequences of Nutritional Stunting. Acta Biomedica Atenei Parmensis, 92(1), 11346. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, A., Hailu, S., Birhane, M., & Belay, M. M. (2021). The prevalence of stunting and associated factors among children under five years of age in southern Ethiopia: Community Based Cross-sectional study. Annals of Global Health, 87(1). [CrossRef]

- Beser, O. F., Cokugras, F. C., Erkan, T., Kutlu, T., Yagci, R. V., Ertem, D., Yaşöz, G., Yüksekkaya, H. A., Artan, R., Önal, Z., Coşkun, M. E., Aydoğan, A., Zorlu, P., Akçaboy, M., Tosun, M. S., Urgancı, N., Kaya, R. G., Satar, M., Yüce, A., … Kırbıyık, F. (2018). Evaluation of malnutrition development risk in hospitalized children. Nutrition, 48, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Imani, B., Nasab, M. H., Gholampour, Z., Abdollahpour, N., & Mehrbakhsh, Z. (2015). Assessment of malnutrition based on three nutritional risk scores in hospitalized Iranian children. Pediatrics, 135(Supplement_1). [CrossRef]

- Saengnipanthkul, S., Chongviriyaphan, N., Densupsoontorn, N., Apiraksakorn, A., Chaiyarit, J., Kunnangja, S., Wongpratoom, S., Papakhee, S., Det-amnatkul, W., Monwiratkul, J., Saengpanit, P., Limthongthang, P., & Panthongviriyakul, C. (2021). Hospital-acquired malnutrition in paediatric patients: A multicentre trial focusing on prevalence, risk factors, and impact on clinical outcomes. European Journal of Pediatrics, 180(6), 1761–1767. [CrossRef]

- Ong, S. H., & Chen, S. T. (2020). Validation of Paediatric Nutrition Screening Tool (PNST) among hospitalized Malaysian children. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 66(5), 461–469. [CrossRef]

- Giha, I. H., Shaddad, M. I., Yusuf, A., Paga, I. A., Noma, M., & Homeida, M. (2019). Nutritional Status and Its Related Factors in Khalwa Residents, Khartoum State, Sudan. [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, M., & Sibanda, M. (2020). A review of selected studies on the factors associated with the nutrition status of children under the age of five years in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7973. [CrossRef]

- Ekholuenetale, M., Tudeme, G., Onikan, A., & Ekholuenetale, C. E. (2020). Socioeconomic inequalities in hidden hunger, undernutrition, and overweight among under-five children in 35 sub-saharan Africa countries. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 95(1). [CrossRef]

- Gödecke, T., Stein, A. J., & Qaim, M. (2018). The global burden of chronic and hidden hunger: Trends and determinants. Global Food Security, 17, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Siwela, M., Pillay, K., Govender, L., Lottering, S., Mudau, F. N., Modi, A. T., & Mabhaudhi, T. (2020a). Biofortified crops for Combating hidden hunger in South Africa: Availability, acceptability, micronutrient retention and bioavailability. Foods, 9(6), 815. [CrossRef]

- Monzani, A., Ricotti, R., Caputo, M., Solito, A., Archero, F., Bellone, S., & Prodam, F. (2019). A systematic review of the Association of Skipping Breakfast with weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. what should we better investigate in the future? Nutrients, 11(2), 387. [CrossRef]

- Harding, K. L., Aguayo, V. M., & Webb, P. (2017). Hidden hunger in South Asia: A review of recent trends and persistent challenges. Public Health Nutrition, 21(4), 785–795. [CrossRef]

- Archero, F., Ricotti, R., Solito, A., Carrera, D., Civello, F., Di Bella, R., Bellone, S., & Prodam, F. (2018). Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among school children and adolescents living in northern Italy and unhealthy food behaviors associated to overweight. Nutrients, 10(9), 1322. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D. B., Bezerra, I. N., Pereira, R. A., & Sichieri, R. (2018). At-home and away-from-home dietary patterns and BMI z-scores in Brazilian adolescents. Appetite, 120, 374–380. [CrossRef]

- Rachmi, C. N., Jusril, H., Ariawan, I., Beal, T., & Sutrisna, A. (2020). Eating behaviour of Indonesian adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Public Health Nutrition, 24(S2). [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhu, H., Gutin, B., & Dong, Y. (2019). Race, gender, family structure, socioeconomic status, dietary patterns, and Cardiovascular Health in Adolescents. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(11). [CrossRef]

- Perez-Cueto, F. J. (2019). An umbrella review of systematic reviews on Food Choice and nutrition published between 2017 and-2019. Nutrients, 11(10), 2398. [CrossRef]

- Lage Barbosa, C., Brettschneider, A.-K., Haftenberger, M., Lehmann, F., Frank, M., Heide, K., Patelakis, E., Perlitz, H., Krause, L., Houben, R., Butschalowsky, H. G., Richter, A., Kamtsiuris, P., & Mensink, G. B. M. (2017). Comprehensive assessment of food and nutrient intake of children and adolescents in Germany: Eskimo II – The eating study as a Kiggs module. BMC Nutrition, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J. (2016). WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and United Nations Population Divisiontrends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015GENEVA: World Health Organization, 2015. Population and Development Review, 42(4), 726–726. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Manga, M., Al-Jawaldeh, A., Qureshi, A. B., Ali, A. M., Pizzol, D., & Dureab, F. (2021). Nutrition assessment of Under-five children in Sudan: Tracking the achievement of the Global Nutrition Targets. Children, 8(5), 363. [CrossRef]

- Lenters, L. (2016) Management of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in children, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 2). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361900/ (Accessed: 21 August 2024).

- (No date) Algorithm for managing malnutrition in adults. Available at: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Namibia%20flipchart%20algorithm%20adults_Sept2010.pdf (Accessed: 21 August 2024).

- Sudan (no date) Global Nutrition Report | Country Nutrition Profiles - Global Nutrition Report. Available at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/northern-africa/sudan/ (Accessed: 21 August 2024).

- Black, R. E., Allen, L. H., Bhutta, Z. A., Caulfield, L. E., de Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Mathers, C., & Rivera, J. (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet, 371(9608), 243–260. [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J. (2021). FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and whothe state of food security and nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for affordable healthy DIETSFAO, 2020, 320 p. Population and Development Review, 47(2), 558–558. [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M., Borghi, E., Arimond, M., Webb, P., Croft, T., Saha, K., De-Regil, L. M., Thuita, F., Heidkamp, R., Krasevec, J., Hayashi, C., & Flores-Ayala, R. (2018). Prevalence thresholds for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years. Public Health Nutrition, 22(1), 175–179. [CrossRef]

- Moges B, Feleke A, Meseret S, Doyore F. Magnitude of Stunting and Associated Factors Among 6–59 Months Old Children in Hossana Town. Southern Ethiopia J Clinic Res Bioeth. 2015;6:207. [CrossRef]

- Kasajja, M., Nabiwemba, E., Wamani, H. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting among children aged 6–59 months in Kabale district, Uganda. BMC Nutr 8, 79 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wamani H. Report on Nutrition and Food Security Assessment in Acholi Sub-region. 2012. (http://www.unr.ug).

- Yalew BM, Amsalu F, Bikes D. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Stunting, Underweight and Wasting: A Community Based Cross Sectional Study among Children Age 6-59 Months at Lalibela Town. Northern Ethiopia J Nutr Disorders Ther. 2014;4:147. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C. V., Dumith, S. C., & César, J. A. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and excess weight in children aged 0-5 years from the Brazilian semi-arid region. Jornal de Pediatria, 91(2), 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Jonah, C.M.P., Sambu, W.C. & May, J.D. A comparative analysis of socioeconomic inequities in stunting: a case of three middle-income African countries. Arch Public Health 76, 77 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wamani H, Astrom AN, Peterson S, et al. Boys are more stunted than girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:17. [CrossRef]

- Quamme, S. H., & Iversen, P. O. (2022). Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-Saharan africa and its risk factors. Clinical Nutrition Open Science, 42, 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Walker, S. P., Chang, S. M., Powell, C. A., Simonoff, E., & Grantham-McGregor, S. M. (2007). Early childhood stunting is associated with poor psychological functioning in late adolescence and effects are reduced by psychosocial stimulation. The Journal of Nutrition, 137(11), 2464–2469. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, O., Kim, R., Guerrero, S., Hasman, A., & Subramanian, S. V. (2022). Child wasting before and after age two years: A cross-sectional study of 94 countries. eClinicalMedicine, 46, 101353. [CrossRef]

- Al-Waleedi, A.A., Bin-Ghouth, A.S. Malnutrition among hospitalized children 12–59 months of age in Abyan and Lahj Governorates / Yemen. BMC Nutr 8, 78 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A., Dhoubhadel, B.G., Shrestha, D. et al. Risk factors for wasting among hospitalised children in Nepal. Trop Med Health 50, 68 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Juma OA, Enumah ZO, Wheatley H, et al. Prevalence and assessment of malnutrition among children attending the Reproductive and Child Health clinic at Bagamoyo District Hospital. Tanzania BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1094. [CrossRef]

- Groleau V, Thibault M, Doyon M, Brochu EE, Roy CC, Babakissa C. Malnutrition in hospitalized children: prevalence, impact, and management. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2014 Spring;75(1):29–34. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Baxter JA, Al-Madhaki FI, Zlotkin SH. Prevalence of malnutrition at the time of admission among patients admitted to a Canadian tertiary-care pediatric hospital. Pediatric Child Health. 2014;19(8):413–7. Return to ref 20 in article. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S., & Ahmad, Z. (2017). The prevalence of undernutrition upon hospitalization in children in a developing country: A single hospital study from Malaysia. Pediatrics & Neonatology, 58(5), 415–420. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Sehrish et al. “Stunting and associated factors in children of less than five years: A hospital-based study.” Pakistan journal of medical sciences vol. 36,3 (2020): 581–585. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Pileggi, V. N., Monteiro, J. P., Margutti, A. V. B., & Camelo Jr., J. S. (2016). Prevalence of child malnutrition at a University Hospital using the World Health Organization criteria and Bioelectrical Impedance Data. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 49(3). [CrossRef]

- Mărginean, O., Pitea, A. M., Voidăzan, S., & Mărginean, C. (2014). Prevalence and assessment of malnutrition risk among hospitalized children in Romania. Journal of health, population, and nutrition, 32(1), 97–102.

- Huong PT, Lam NT, Thu NN, Quyen TC, Lien DT, Anh NQ, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition in patients admitted to a major urban tertiary care hospital in Hanoi, Vietnam. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23(3):437-44.

- Danso, F., & Appiah, M. A. (2023). Prevalence and associated factors influencing stunting and wasting among children of Ages 1 to 5 years in Nkwanta South Municipality, Ghana. Nutrition, 110, 111996. [CrossRef]

- Welaga Miah, R., & Awingura Apanga, P. (2016). Risk factors for undernutrition in children under five years old: Evidence from the 2011 Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 7(7). [CrossRef]

- Darteh, E. K., Acquah, E., & Kumi-Kyereme, A. (2014). Correlates of stunting among children in Ghana. BMC Public Health, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Ocheke, I., John, C., & Puoane, T. (2014). Factors influencing the pattern of malnutrition among acutely ill children presenting in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics, 41(4), 326. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S., Hiremath, R., Ramakrishna, T., Chourey, N., & Ghodke, S. (2023). Prevalence of underweight, stunting, wasting and obesity among urban school going children – need for action. Medical Journal of Dr. D.Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, 16(7), 63. [CrossRef]

- Dukhi, N. (2020). Global prevalence of malnutrition: Evidence from literature. Malnutrition. [CrossRef]

- Sand A, Kumar R, Shaikh BT, Somrongthong R, Hafeez A, Rai D. (2018). Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among children under five years in a rural remote setting: A hospital-based study from district Tharparkar-Sindh. Pakistan Pak J Med Sci. 34(2):260-5. [CrossRef]

- Thurstans, S., Opondo, C., Seal, A., Wells, J., Khara, T., Dolan, C., Briend, A., Myatt, M., Garenne, M., Sear, R., & Kerac, M. (2020). Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: A systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Global Health, 5(12). [CrossRef]

- Danso, F., & Appiah, M. A. (2023). Prevalence and associated factors influencing stunting and wasting among children of Ages 1 to 5 years in Nkwanta South Municipality, Ghana. Nutrition, 110, 111996. [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, F., Das, S. K., Ahmed, S., Farzana, F. D., Latham, J. R., Chisti, M. J., Ud-Din, A. I., Azmi, I. J., Talukder, K. A., & Faruque, A. S. (2013). Severity of diarrhea and malnutrition among under five-year-old children in rural Bangladesh. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 89(2), 223–228. [CrossRef]

- Nouri Saeidlou, S., Babaei, F., & Ayremlou, P. (2014). Malnutrition, overweight, and obesity among urban and rural children in north of West Azerbijan, Iran. Journal of Obesity, 2014, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S. M., Javaherizadeh, H., Heidary, M., Honar, N., Ataollahi, M., Ilkanipour, H., & Moravej, H. (2018). Stunting, wasting, and Mid Upper Arm circumpherence status among children admitted to Nemazee Teaching Hospital. Nutrición Hospitalaria. [CrossRef]

- Veghari, G. (2015). The comparison of under-five-children’s nutrition status among ethnic groups in north of Iran, 1998 - 2013; results of a three stages cross-sectional study. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, 25(4). [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S., Fouladgar, M., Naeeni, M., Fakhri, M., Fatemi, S., Heidari, K., & Bagheri, S. (2014). Body mass index, weight-for-age, and stature-for-age indices in Iranian school children in relation to weight and growth disorders: A population-based survey. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 5(14), 133. [CrossRef]

- Saengnipanthkul, S., Apiraksakorn, A., Densupsoontorn, N., & Chongviriyaphan, N. (2023). Prevalence and risk factors for pediatric acute and chronic malnutrition: A multi-site tertiary medical center study in Thailand. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 32(1), 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Villares, J. M., Varea Calderón, V., Bousoño García, C., Lama Moré, R., Redecillas Ferreiro, S., Peña Quintana, L., & Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología (2013). Evaluación del estado nutricional de niños ingresados en el hospitalen en España; estudio DHOSPE (Desnutrición Hospitalaria en el Paciente Pediátrico en España) [Nutrition status on pediatric admissions in Spanish hospitals; DHOSPE study]. Nutricion hospitalaria, 28(3), 709–718. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa K. S. (2011). Socio-economic determinants of severe and moderate stunting among under-five children of rural Bangladesh. Malaysian journal of nutrition, 17(1), 105–118.

- Pal, A., Pari, A. K., Sinha, A., & Dhara, P. C. (2017). Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 4(1), 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Kaur S, Bains K, Kaur H Assessment of Stunting and Malnutrition among School-going Children from different Cultural Regions of Punjab, India. Indian J Ecol 2017;44: 898-903.

- Jakkula, R., Kamath, R., & Kumar, S. (2015). Nutritional status assessment of school children in Bellary District, Karnataka. Journal of Dr. NTR University of Health Sciences, 4(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T., & Heywood, P. (1991). Mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC) in relation to other indices of nutritional status in Papua New Guinea. Papua and New Guinea medical journal, 34(1), 26–34.

- Ubesie, A. C., Ibeziako, N. S., Ndiokwelu, C. I., Uzoka, C. M., & Nwafor, C. A. (2012). Under-five protein energy malnutrition admitted at the University of in Nigeria Teaching Hospital, enugu: A 10 Year Retrospective Review. Nutrition Journal, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Laghari, Z. A., Soomro, A. M., Tunio, S. A., Lashari, K., Baloach, F. G., Baig, N. M., & Bano, S. (2015). MALNUTRITION AMONG CHILDREN UNDER FIVE YEARS IN DISTRICT SANGHAR, SINDH, PAKISTAN. Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences, 13(1). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A418348521/AONE?u=anon~70b8ec03&sid=googleScholar&xid=67df5acd.

- Grellety, E., Krause, L. K., Shams Eldin, M., Porten, K., & Isanaka, S. (2015). Comparison of weight-for-height and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) in a therapeutic feeding programme in South Sudan: Is Muac alone a sufficient criterion for admission of children at high risk of mortality? Public Health Nutrition, 18(14), 2575–2581. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Responses | F (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of the participants | <12 months | 71 (26.5%) |

| 1 - <3 years | 40 (14.9%) | |

| 3 - <5 years | 22 (8.2%) | |

| 5 - 9 years | 21 (7.8%) | |

| >10 Years | 114 (42.5%) | |

| Gender | Males | 146 (54.5%) |

| Females | 122 (45.5%) | |

| Residence | Urban areas | 217 (81.0%) |

| Rural areas | 51 (19.0%) | |

| Reasons for hospital admission | Sickle cell anaemia | 54 (20.1%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infections (ARI) | 51 (19.0%) | |

| Epilepsy | 31 (11.6%) | |

| Urinary system diseases | 18 (6.7%) | |

| Other health problems | 21 (7.8%) | |

| Number of hospitalization | Hospitalized for the first time | 163 (60.8%) |

| Hospitalised for the second time | 59 (22.0%) | |

| Hospitalized more than twice within six months | 46 (17.2%) |

| Age groups | <-3 HAZ-score F (%) |

-3 to -2 HAZ-score F (%) |

Overall stunting F (%) |

>-2 HAZ-score F (%) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <12 months | 12 (16.9%) | 10 (14.1%)* | 22 (31.0%)* | 49 (69.0%) | 71 |

| 1 - <3 years | 8 (20.0%) | 4 (10.0%) | 12 (30.0%) | 28 (70.0%) | 40 |

| 3 - <5 years | 4 (18.2%) | 1 (4.5%) | 5 (22.7%) | 17 (77.3%)* | 22 |

| 5 - 9 years | 5 (23.8%)* | 1 (4.8%) | 6 (28.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | 21 |

| ≥10 years | 20 (17.5%) | 4 (3.5%) | 24 (21.1%) | 90 (78.9%) | 114 |

| Total | 49 | 20 | 69 | 199 | 268 |

| Age groups | <-3 WHZ-score F (%) |

-3 to -2 WHZ-score F (%) |

Overall wasting F (%) |

-2 to +1 WHZ-score F (%) |

+1 to +2 WHZ-score F (%) |

>+3 WHZ-score F (%) |

Overall overnutrition F (%) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <12 months | 12 (16.9%) | 13 (18.3%) | 25 (35.2%) | 39 (54.9%) | 4 (5.6%) |

3 (4.2%) |

7 (9.9%) |

71 |

| 1 - <3 years | 9 (22.5%) | 8 (20.0%)* | 17 (42.5%)* | 21 (52.5%) | 1 (2.5%) |

1 (2.5%) |

2 (5.0%) |

40 |

| 3 - <5 years | 5 (22.7%)* | 3 (13.6%) | 8 (36.4%) | 10 (45.5%) | 2 (9.1%) | 2 (9.1%) | 4 (18.2%) |

22 |

| 5 - 9 years | 2 (9.5%) | 4 (19.0%) | 6 (28.6%) |

6 (28.6%) | 5 (23.8%)* | 4 (19.0%)* | 9 (42.9%)* |

21 |

| ≥10 years | 17 (14.9%) | 4 (3.5%) |

21 (18.4%) | 85 (74.6%)* | 4 (3.5%) |

4 (3.5%) |

8 (7.0%) |

114 |

| Total | 45 | 32 | 77 | 161 | 16 | 14 | 30 | 268 |

| Age groups | F (%) | Malnutrition among age groups F(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <12 months (n=71) | |||

| <115 mm | Severe | 22 (31.0%)* | 29 (40.8%)* |

| 115 to 125 mm | Moderate | 7 (9.9%) | |

| >125 mm | Normal | 42 (59.2%) | - |

| 1 - <3 years (n=40) | |||

| <115 mm | Severe | 11 (27.5%) | 15 (37.5%) |

| 115 to 125 mm | Moderate | 4 (10.0%)* | |

| >125 mm | Normal | 25 (62.5%) | - |

| 3 - <5 years (n=22) | |||

| <115 mm | Severe | 2 (9.1%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| 115 to 125 mm | Moderate | 1 (4.5%) | |

| >125 mm | Normal | 19 (86.4%) | - |

| 5 - 9 years ( n=21) | |||

| <135 mm | Severe | 1 (4.8%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| 135 - 145 mm | Moderate | 1 (4.8%) | |

| >145 mm | Normal | 20 (95.2%)* | - |

| ≥10 years (n=114) | |||

| <160 mm | Severe | 5 (4.4%) | 8 (7.0%) |

| 160 - 185 mm | Moderate | 3 (2.6%) | |

| >185 mm | Normal | 106 (93.0%) | - |

| Overall malnutrition | 57 (21.3%) | ||

| Categories | All (N = 268 F (%) [95% CI] |

Males (N = 146) F (%) [95% CI] |

Females (N= 122) F (%) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting | |||

| Severe stunting (<-3 z-score) | 49 (18.3%) [13.6 - 22.9] |

28 (19.18%) [12.7 - 25.6] |

21 (17.2%) [11.5 - 24.9] |

| Moderate stunting (<-3 to -2 z-score) | 20 (7.4%) [4.9 - 11.2] |

12 (8.2%) [4.7 - 13.7] |

8 (6.6%) [3.4 - 12.4] |

| Normal height-for-age (>-2 z-score) | 199 (74.25%) [69 - 79.6] |

112 (76.71%) [76.5 - 83.6] |

87 (71.31%) [63.4 - 79.5] |

| MUAC | |||

| Severe malnutrition | 41 (15.33%) [11 - 19.6] |

19 (13.01%) [7.6 - 18.4] |

22 (18.03%) [11.1 - 24.9] |

| Moderate malnutrition | 16 (5.97%) [3.3 - 8.8] |

10 (6.85%) [2.7 - 10.9] |

6 (4.92%) [1.1 - 8.7] |

| Normal (no malnutrition) | 212 (79.1%) [74.2 - 83.9] |

101 (69.9%) [61.7 - 76.7] |

111 (91.8%) [86 - 96] |

| Wasting | |||

| Severe wasting (<-3 SD) | 45 (16.8%) [12.17 - 21.43] |

25 (17.1%) [10.0 - 24.2] |

20 (16.4%) [9.0 - 23.8] |

| Moderate wasting (-3 to -2 SD) | 32 (11.9%) [7.9 - 15.8] |

8 (5.5%) [3.1 - 7.9] |

24 (19.7%) [12.1 - 27.3] |

| Overnutrition | |||

| Overweight (+1 to +2 SD) | 16 (6.0%) [4.4 - 11.1] |

10 (6.8%) [3.8 - 9.8] |

6 (4.9%) [2.6 - 7.2] |

| Obesity (>+3 SD) | 14 (5.2%) [3.7 - 10.0] |

9 (6.1%) [3.5 - 8.9] |

5 (4.1%) [2.1 - 6.1] |

| Normal weight-for-height/length (-2 to +1 SD) | 161 (60.1%) [54.2 - 66.0] |

94 (64%) [56.6 - 72.2] |

67 (54.9%) [46 - 63.7] |

| Kendall’s tau_b Correlation Coefficient |

Age | Gender | Vaccination | Breast feeding | Weaning age | Weaning mechanism |

Admissions | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | -0.03 | -0.135** | 0.00 | -0.365** | 0.230** | 0.046 | 0.136** |

| Gender | -0.03 | 1 | 0.141* | 0.00 | -0.07 | 0.135 | 0.044 | -0.015 |

| Vaccination | -0.135** | 0.141* | 1 | 0.108 | 0.177** | -0.045 | -0.114* | -0.045 |

| Breast feeding | 0.00 | -0.001 | 0.108 | 1 | -0.03 | 0.011 | -0.121* | -0.015 |

| Weaning age | -0.365** | -0.071 | 0.177** | -0.03 | 1 | 0.257** | -0.03 | -0.066 |

| Weaning mechanism | 0.230** | 0.135 | -0.05 | 0.011 | 0.257** | 1 | -0.009 | 0.147* |

| Admissions | 0.046 | 0.044 | -0.114* | -0.121* | -0.03 | -0.009 | 1 | 0.096 |

| Diagnosis | 0.136** | -0.015 | -0.05 | -0.02 | -0.07 | 0.147* | 0.096 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).