1. Introduction

Open-burning of agricultural residues is a common practice worldwide, whether for eliminating agriculture residues or to promote land clearing [

1]. In Portugal, this practice is particularly prevalent during the wet season, which usually runs from October to April. Typically, these fires involve pile burning of agricultural waste and shrubbery (e.g., pruning and cuttings), or deliberate burning of vegetation to promote the creation of pastures for livestock, control of invasive species and reduce wildfire hazard [

2,

3,

4,

5].

As single events, these burning practices are characterized by having small intensity and extents. However, the generalized practice of open burning of agriculture residues can have several negative environmental impacts. Biomass burning releases greenhouse gases [

6], contributing to climate change, and particulate matter and gaseous atmospheric pollutants [

7,

8,

9], impacting air quality and posing health risks to nearby communities. The cumulative effects on ecosystems are also significant, as frequent burning disrupts soil structure, depletes essential nutrients, and can hinder natural vegetation growth [

10]. Over time, these disturbances may reduce soil fertility, alter biodiversity, and weaken ecosystem resilience, potentially transforming land into degraded areas susceptible to erosion [

11] and invasive species [

12]. Furthermore, in certain conditions, open burning may inadvertently escalate into uncontrolled wildfires, intensifying the environmental impact and heightening risks to public safety.

While open-burning is typically an unregulated practice, often carried out by non-experts, prescribed fire differs greatly in many aspects, particularly in terms of safety, purpose, and environmental impacts [

13]. Prescribed fires are carefully controlled burns conducted by trained professionals to achieve specific management objectives like reducing wildfire fuel loads, enhancing wildlife habitats, and supporting native vegetation [

14,

15]. Prescribed fires are subject to legal regulations and follow a detailed plan that includes site mapping, weather monitoring, and safety protocols, ensuring that they benefit ecosystems while minimizing risks and impacts [

14].

The use of satellite remote sensing (RS) has been widely used to study fire phenomena. These approaches typically include active fire detections, through the detection of thermal anomalies. The detection of fire anomalies is usually carried through high temporal resolution satellites, equipped with optical multispectral sensors, which often operate in the long-wavelength infrared range (e.g., MODIS, VIIRS, Sentinel-3) [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Instead, post-fire analysis, such as the determination of burned extents or severity, often involves the use of higher spatial resolution satellites, which given the persistent effects of fires, are not constrained by high revisiting time requisites (e.g., Landsat series, Sentinel-2) [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Considering the environmental impacts of open burning of agricultural residues and the relatively unknown locations and timing of these events, remote sensing holds significant potential for providing valuable insights into these practices. However, the relatively low intensity and spatial extent of these fires, combined with the fact that they often occur during cloudy conditions, which severely hinder the operability of multispectral optical sensors, pose additional challenges for satellite-based RS analysis.

This paper aims to determine whether small-scale open burning of agriculture residues can be detected using RS. Moreover, it has the objective of identifying the best methods and products for systematic analysis and validation. To achieve this, a series of case studies will be analyzed, involving the testing of various satellite products and RS techniques. Additionally, the paper includes a comparison of RS products and methods against a comprehensive dataset of open-burning requests, serving as a 'best possible' validation reference.

2. Material and Methods

In order to verify the potential of analysis of small-scale open burning of agriculture residues through RS, this study focuses on several cases studies with varying spatial extents: two local scale analysis, which were validated on the field at ground level, and a systematic national scale analysis.

2.1. Case Studies

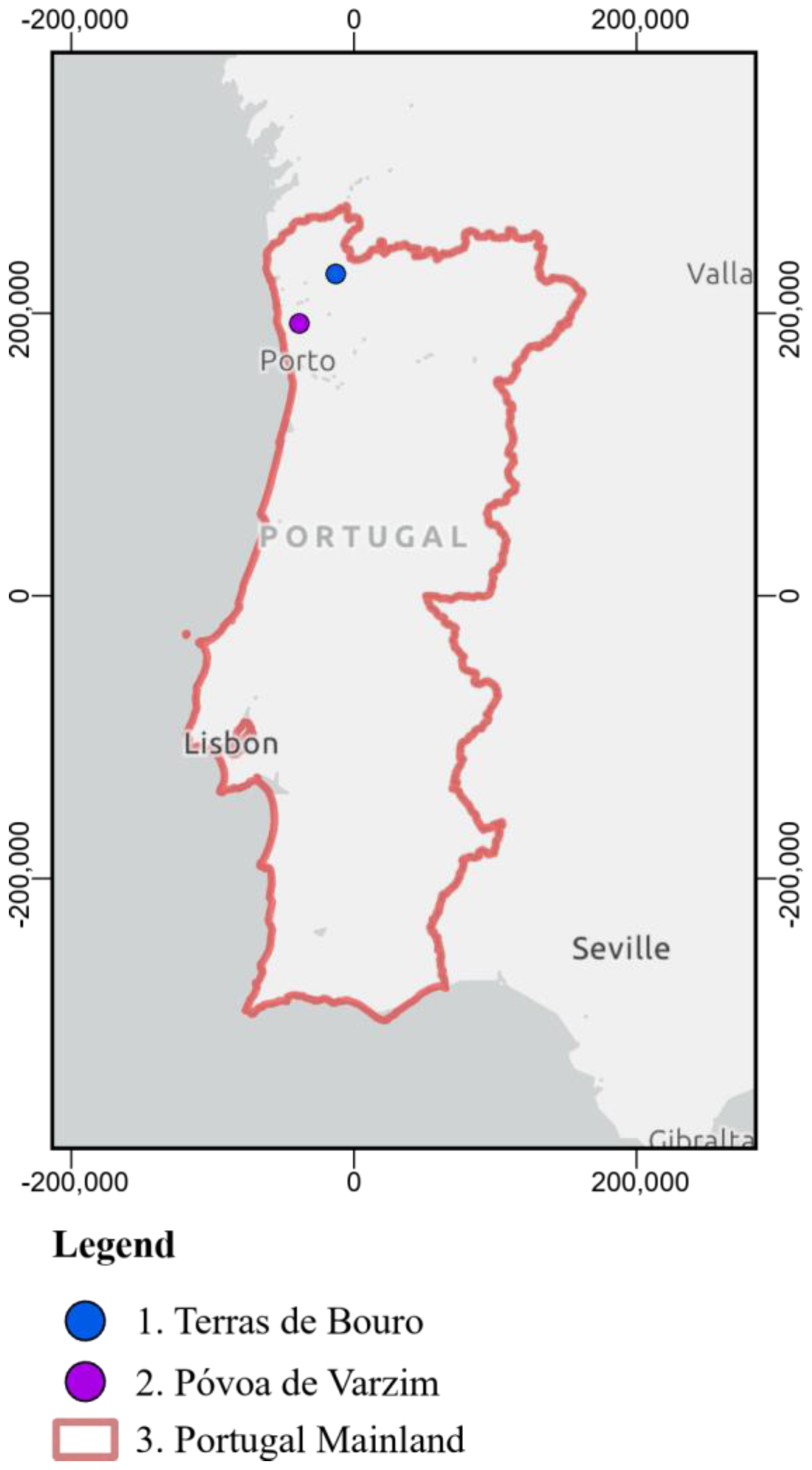

The two local scale analysis are located in the Northern Portugal mainland

Figure 1 and correspond to known events involving extensive controlled biomass burning (

Figure 1 – Terras de Bouro and Póvoa do Varzim). One of these events consists of a prescribed fire, which despite the differences from agriculture open burnings - particularly regarding potential impacts on soil and vegetation - was included to assess the capability of RS to monitor small-scale fires. The national level analysis consists of a systematic analysis for the Portugal Mainland, between 2019 and 2023 (

Figure 1 – Portugal Mainland).

2.1.1. Terras de Bouro

The first local case study corresponds to several agriculture extensive burnings taking place on nearby the Peneda-Gerês National Park, in Terras de Bouro (

Figure 1 – Terras de Bouro

Error! Reference source not found.). These occurrences are a common practice in this region, particularly for creating pastures [

24]. Some of these events were observed during February 16th, 2023, and likely led to significant local air quality degradation. While rural areas like this lack direct air quality monitoring data, existing literature on small-scale experimental field fires provides valuable insights into the potential air quality impacts of such activities, helping substantiate this assessment [

25,

26]. For example, [

25] measured dangerously high average particulate matter concentrations (> 1000 µg.m-3) near the source during a shrubland burn (< 1 hour). Similarly, [

26] demonstrated that firefighters are exposed to air pollutions levels exceeding the Occupational Exposure Standard limits, emphasizing the urgent need for preventive measures to mitigate these exposure risks. The cumulative evidence from these studies suggests that even controlled burns can lead to significant air quality degradation, reinforcing concerns about the local impacts of small-scale open-burning agriculture practices. Although prescribed burns in Portugal require permits, the regulations focus primarily on ambient conditions such as wind speed, relative humidity, and temperature to minimize wildfire risk, rather than specifically addressing air quality impacts, as is common practice in the United States of America (USA)[

27].

According to the official yearly database of burned areas by the Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests (ICNF) [

28], this region also experienced several other events from January 31st to February 24th ,2023. Among those, 2 occurrences corresponded to intentional fires for hunting and wildlife management, 2 involved negligent pile burning of forest or agriculture residues, 3 negligent burning of forest or agriculture residues, 24 corresponded to negligent burning for pasture management and 5 were arson fires (see

Section 3.1).

2.1.2. Póvoa de Varzim

The second local case study corresponds to two consecutive controlled prescribed fires occurred in a recent clearcut of a Eucalyptus plantation, which took place in Balazar, Póvoa de Varzim, on March 2nd and 4th, 2023 (

Figure 1 - Póvoa de Varzim

Error! Reference source not found.). This event was undertaken by the local Forest Association Portucalea in collaboration with Forestry sappers from Vila do Conde and the Volunteer firefighters of Póvoa de Varzim, firstly on March 2nd, as a very controlled and low intensity burning along a thin strip of about 30 x 100 m (

Figure 2), and on March 4th another larger section within the same clearcutting plot (see Section 3.2). The fire was conducted downslope, against the wind under a very low fire danger class. As with all prescribed fires, this case study is not accounted by the ICNF yearly burned areas database.

2.1.3. Portugal Mainland

Besides the local case studies, this study also includes a national level analysis of agriculture burning requests for Portugal mainland (

Figure 1 – Portugal mainland). For such analysis we have considered a national-level database of agricultural burning requests (ABR) for mainland Portugal, provided by ICNF. Such database results from the current legislation (DL 82/2021, from October 13), which states that agricultural residue burning is allowed between November 1st and May 31st on days when the fire danger is not classified among the highest risk levels, with only the requirement of notifying ICNF via an app or directly through local municipalities. The dataset includes 4 099 487 requests, covering the period from 2019/12/04 to 2023/11/30, containing information such as location (parish, municipality, district), geographical coordinates, and, in some cases, additional data like the type of burning, motive, burned area, and authorization status.

2.2. Fire Detection Methods

2.2.1. Active Fire Detections

The case studies have been analyzed in terms of active fire detections, initially by comparing Fire Radiative Products (FRP), obtained from different satellite platforms. The FRP represents the rate of outgoing thermal radiative energy, resulting from a burning fire, which is usually expressed in megawatts (MW) [

29].

Table 1 summarizes the FRP related products from Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), The Sea and Land Surface Temperature Radiometer (SLSTR), and Spinning Enhanced Visible Infra-Red Imager (SEVIRI), which were considered in this study.

Despite the high temporal resolution of the considered FRP products, one of the key limitations for detecting small fires is their limited spatial resolution. For this reason, in our study, we have also considered the Landsat 8 and 9 platforms, which together have a revisit time of 8 days. In both cases, these satellites are currently active and equipped with Thermal Infrared Sensors (respectively, TIRS and TIRS-2), which offer 100 m spatial resolution, which represents a significant improvement in respect to the FRP products of

Table 1. However, each of these satellites is also equipped with the Operational Land Imager (respectively OLI and OLI-2), which simultaneously image several multispectral bands, operating from the visible to shortwave-infrared range, at 30 m resolution [

33,

34]. The Landsat Active Fire and Thermal Anomalies product, produced by the joint NASA/USGS OLI sensors on Landsat 8 and 9, is based on the algorithm developed by [

18] and is currently available for the continental USA, southern Canada, and northern Mexico [

35]. Since our case studies (

Section 2) fall outside these regions, we directly implemented the [

18] algorithm to detect active fires in these locations at 30 m resolution. This algorithm has been found to effectively detect fires in both daytime and nighttime conditions, including small-scale events such as biomass burning, gas flares, and active volcanoes. Despite recognizing minimal spectral and radiometric differences between the OLI and OLI-2 sensors, we have implemented this algorithm with the same numerical conditional values for both Landsat 8 and 9 images.

2.2.2. Estimation of Burned Extents

Unlike active fire detections, which require high temporal resolution due to the need to capture the fire in progress, burned area estimation using satellite remote sensing is less demanding in this regard. For active fire detection, the fire must be burning at the exact time the satellite image acquisition, while cloud-cover free conditions are necessary for accurate detections [

36]. In contrast, post-burn analysis can take advantage of the lasting effects of fire—such as charred vegetation or burn scars—that persist for extended periods after the fire has been extinguished [

37]. This persistence reduces the urgency of capturing the event at a specific time, thus allowing for the use of satellites with higher spatial resolution but lower temporal frequency, as they are more likely to acquire clear imagery of the burned area after the fire event.

Post-fire analysis using remote sensing are a common practice in disaster management and environmental monitoring. The Copernicus Emergency Management Service often provides detailed mapping and assessments of disasters, including wildfires, on a global scale. However, for smaller-scale agricultural fires, which often don't trigger emergency protocols, alternative solutions are necessary.

The MINDED-FBA tool [

38], is a remote sensing based tool for determining flooded and burned extents. The tool incorporates Optical Multispectral (OMS) and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) modules, which allow performing automatic multi-index differencing threshold selection procedures aimed at image classification. The OMS module has been found to be particularly effective for determining burned area extents, which is useful for validating active fire detections and evaluating extensive biomass burning areas [

22,

39].

The implementation of the MINDED-FBA tool requires the input of both pre-event (

t0) and post-event (

t1) scenes, which are used to calculate a set of pre-defined indices, and single-index differences. The tool performs automatic thresholding of these index-difference scenes, followed by density slicing to classify pixels as ‘No Change’ (Nc), ‘Low Magnitude change’ (LMc), or ‘High Magnitude change’ (HMc). These classifications are then combined into an overall map with a pixel-by-pixel majority analysis. If no majority is found among the single-index difference classifications, that pixel is assigned with the ‘Mixed’ class [

22,

39].

The MINDED_FBA tool was implemented for both the Terras de Bouro and Póvoa de Varzim case studies, using the OMS module with Level-2 surface reflectance products derived from Landsat and Sentinel-2 data [

33,

34,

40] (

Table 2). All the available pre-processing procedures were selected, including cloud/cloud shadow masking, permanent water bodies masking (considering thematic data from [

41] as well as topographic correction (using ALOWS WORLD 3d - 30m, [

42]). Since the processing included Burned areas estimation, the resulting classifications (i.e., Nc, LMc, HMc and Mixed) should correspond to burned-related changes.

The ICNF releases the yearly burned area dataset, which consists of a multi-source survey, combining fieldwork and remote sensing interpretation. This dataset includes information about the starting and ending date, location, type (e.g., negligent or intentional) and cause of fire (e.g., accidental, arson, pile or extensive residue burnings). This official dataset represents the best ground-truth alternative for validating burned area extent estimations in Portugal [

38].

2.2.3. Active fire detections of agriculture residue open-burning

Besides the satellite active fire detections and post-burn analysis, this study has considered the ABR which was made available by ICNF for this study. Such dataset represents the best available register of agriculture residue burning occurrences in Portugal. However, it should be highlighted that neither all registered burns get to be executed, neither all burn activities are included in the ABR database. In many cases, these practices are not undertaken (at least on the requested date), due to unfavorable local weather conditions, which have a direct influence on the moisture level of the biomass residues, which must be dry enough to allow burning. On the other hand, not all agricultural burning requests are processed and integrated on the ICNF ABR dataset, as some municipalities are still not integrated into this system. Finally, despite the legal requirements for registering such practices, unauthorized burns remain widespread in Portugal.

To evaluate the capability of detecting open-burnings of agriculture residues through satellite RS, we used geospatial analysis tools (ArcGIS Pro, v3.2.2) to intersect the ABR database with the different RS fire detection products.

Beyond the direct intersection between both datasets, we implemented supplementary procedures to address potential spatial and temporal inconsistencies between them. In respect to the ABR database, we tested the application of distance buffers of 10 meters and 100 meters to account for Global Positioning System (GPS) inaccuracies, as well as temporal buffers from the reported request dates—including ±1 day and ±1 week. As for the FRP products, spatial buffers were implemented in respect to each pixel centroid considering the corresponding sensor spatial resolution (

Table 1). The analysis of the intersections according to different buffering considerations, will provide insights into the detection capabilities of different remote sensing products, the optimal time windows for detection, and the characteristics of various types of agricultural residue burning.

3. Results

3.1. Terras de Bouro

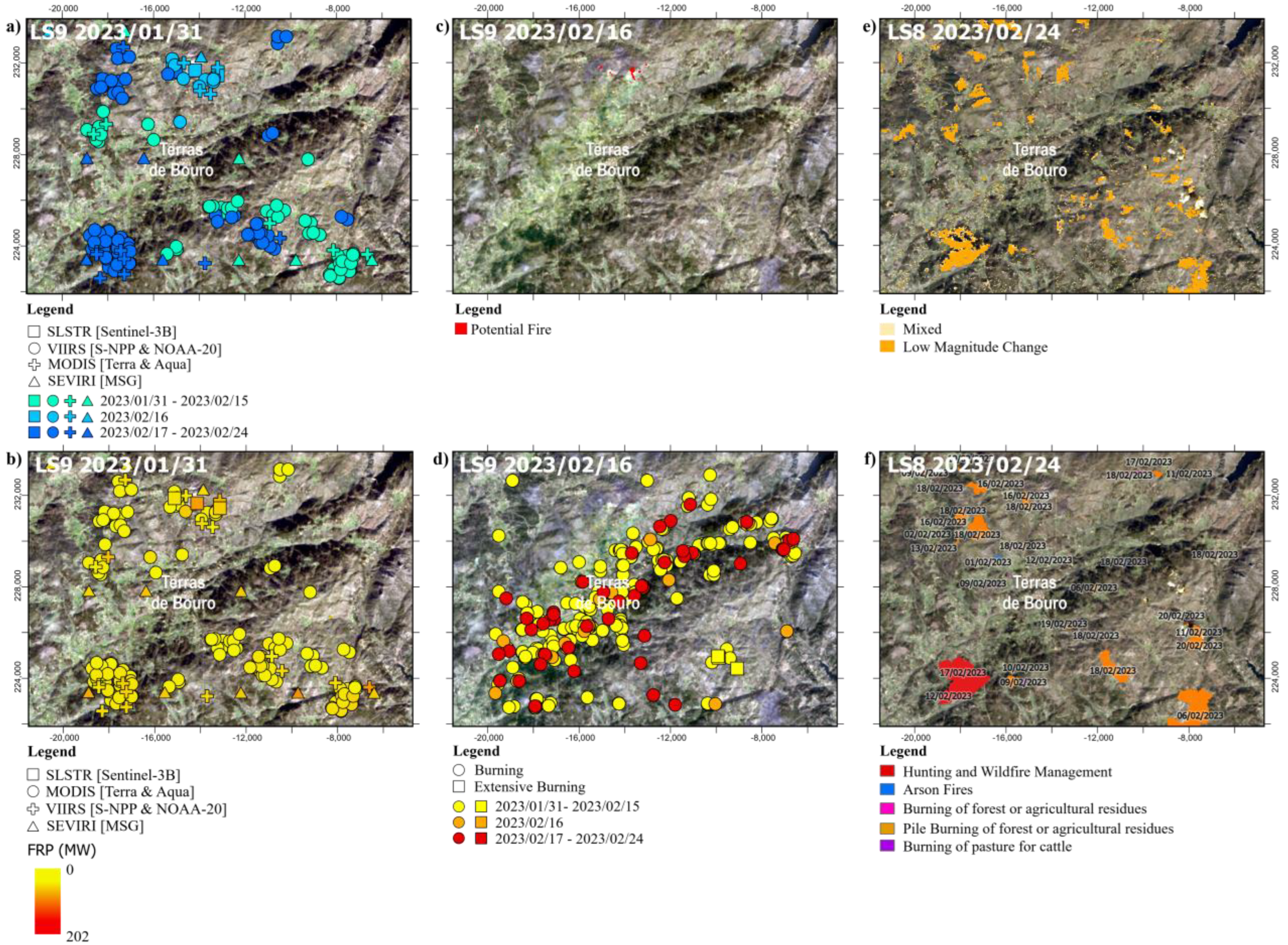

In

Table 3, we can find the available products used for detecting active fires in Terras de Bouro (as well as for the Póvoa de Varzim case study – Section 4.2). Regarding the FRP products, we have listed the initial and end time of acquisitions from VIIRS, MODIS and SLSTR, including those scenes resulting in positive and negative detections. As for SEVIRI, we have only listed the acquisition time for positive detections, since this platform is capable of producing FRP products every 15 min.

For the Terras do Bouro case study, we can verify that most FRP detections during February 16th, 2023, correspond to the SEVIRI, with a total of 21 scenes with positive detections, particularly concentrated within the 9:30-16:15 period. As for the remaining sensors, the VIIRS instruments included most detections, including one from S-NPP during early nighttime period, which was neither detected by VIIRS/NOAA-20 or MODIS/Aqua at around the same period. As for daytime detections, all satellites registered positive detections from 10:50 to 14:30. Using the Daytime Active Fire Detection Algorithm, we could also find positive detection for February 16th, using the Landsat 9 OLI-2 SR data.

In

Figure 3a, we can verify that all FRP acquisitions from February 16th have been detected northern to the Terras de Bouro village, corresponding to 14 detections for SEVIRI, 10 for VIIRS, 4 for MODIS and 3 for SLSRT. The most southern detection corresponds to the single nighttime detection provided by VIIRS/S-NPP (02:12-02-18, previously mentioned from the analysis of

Table 3), which recorded a relatively low magnitude FRP (4.9 MW) (

Figure 3 b). The improved spatial resolution of the Landsat 9 OLI-2 seems to indicate that 6 different active fires took place around 11h, which seems to demonstrate a good spatial correlation with the remaining lower resolution FRP products (

Figure 3c). The highest magnitude FRP detections were obtained from SEVIRI/MSG (74.4 MW) and SLSTR/Sentinel-3B (72.0 MW), MODIS/Terra (56.1 MW) and VIIRS/NOAA-20 (35.8 MW). For such higher magnitude FRP detections, the pixel centroids from VIIRS/NOAA-20 and MODIS/Aqua are located within less than 1 km in respect to the SLSTR/Sentinel-3B pixel centroid) (

Figure 3b).

Moreover, in

Figure 3a, we have also included every positive detection in terms of FRP for VIIRS, MODIS and SEVIRI, during the antecedent and following days to February 16th. For these periods (as well as for the subsequent national-level analysis in Section 4.3), we have not included the SLSTR/Sentinel-3 data, since we could not find any readily available catalog in archive mode (e.g., NETCDF). Within both periods, most detections were registered by SEVIRI (respectively 107 and 100), followed by VIIRS (51 and 74) and MODIS (5 and 9).

Regarding the MINDED-FBA map (

Figure 3f), which was produced for the whole January 31st to February 24th period, we can find several areas classified as Low Magnitude changes. Such areas seem to have a good spatial correlation with both FRP and DAFDA, as well as with the ICNF yearly burned area dataset. The few pixels classified as ‘Mixed’ resemble “salt-and-pepper” noise [

22,

39].

The analysis of the ABR dataset map (

Figure 3d), from January 31st to February 24th, indicates a total of 389 requests. Among these, there are only 3 records corresponding to extensive burning requests (all from February 7th), while the remaining correspond to burning requests for agriculture residues (31/01-15/02: 311; 16/02: 23; and 17/02-24/02: 52). When comparing the ABR database (

Figure 3d) with the remaining datasets, there are few apparent spatial correlations with either active fire detections (

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b) or post-burn extents (

Figure 3f and

Figure 3e). The few exceptions seem to correspond to a couple of extensive burning requests from 07/02/2023, which seem to have been detected by VIIRS. However, such detections have occurred on 06/02/2023 (from 2:01 to 2:49), which corresponds to a -1 day difference. However, when applying a distance buffer equivalent to each satellite instrument resolution (

Table 1), we found 156 intersections with SEVIRI, corresponding to 11 burning requests and 2 extensive burning requests. However, if we extent the temporal window to minus or plus 1 day, we find 358 intersections with SEVIRI, 2 with VIIRS and 1 with MODIS. Among these, correspond to 29 agriculture burning requests, and 2 extensive burnings. Likewise, if we consider a temporal window of minus or plus 1 week, we obtain 1565 intersections with SEVIRI, 6 with MODIS and 4 with VIIRS.

Regarding the Póvoa de Varzim case study, the analysis of

Table 3 includes one positive detection from VIIRS/NOAA during March 2nd, and two positives for March 4th, with both VIIRS (S-NPP and NOAA), all during the early afternoon period.

The analysis of

Error! Reference source not found. Figure 4a and

Figure 4b allows verifying that only one detection occurred on March 2nd, which registered the lowest magnitude of FRP (1.9 MW). For March 4th, VIIRS/S-NPP included another detection, which resulted in the overall maximum of FRP magnitude (16.9 MW), while NOAA-20 detected the other two points (with 4.1 and 4.2 MW). In the Sentinel-2B scene from March 3th (i.e., corresponding to the day in between the two controlled fire events) (

Figure 4c), it is possible to confirm the outline of the first fire from March 2th (

Figure 4a), which pixel centroid is located within circa 100 m (i.e., below the VIIRS spatial resolution size) from the fire perimeter of that day (

Figure 4e). As for March 4th, the other 3 points are also located within a distance under the VIIRS spatial resolution limit.

Regarding the MINDED-FBA results (

Figure 4d), we can verify the detection of both High Magnitude and Low Magnitude changes, which have a good spatial correlation with the overall fire perimeter. However, besides the Mixed pixels, which once again resemble ‘salt’-and-pepper’ noise, it is also possible to find other patches of Low Magnitude change pixels distributed around the Eucalyptus clear-cut plot. When comparing Sentinel-2 scenes from February 28th (

Figure 4a), and March 15th (

Figure 4d) (which corresponds to the t0 and t1 scenes used to implement the MINDED-FBA tool), it is possible to verify that such Low Magnitude change pixels seem to be related with land-use changes, particularly from plowing operations external to the study area.

Regarding the ABR dataset, we can find a single register for March 2nd, corresponding to a burning request, which has been located on the access pathway adjacent to the plantation plot, with approximately 100 m distance from the overall burned area (

Figure 4c).

3.3. Portugal Mainland

In addition to the two local case studies, we conducted a systematic comparison for mainland Portugal between remote sensing detections of active fires and ABR from 2019 to 2023.

Regarding the active fire detections, we have considered those FRP products which were readily available in archive catalogues within the considered period. These included VIIRS (S-NPP and NOAA-20), MODIS (Terra and Aqua), and SEVIRI (Meteosat Second Generation). After acquiring all available FRP products, we applied spatial buffers to account for the resolution of each product and performed direct spatial intersections with the ABR coordinates (

Table 4). This intersection resulted in 3,410 matches, including 3,044 from SEVIRI, 312 from MODIS, and 54 from VIIRS. In addition to assessing total number of intersections, we have also analyzed the number of unique burning requests that resulted in at least one detection using the FRP products (

Table 5). This analysis considered both types of agricultural burning requests, resulting in 1,239 standard burning requests and 132 extensive burning requests.

Table 4 also includes the total number of intersections when additional spatial buffers (10 m and 100 m) and temporal buffers (±1 day and ±1 week) are applied. The results indicate that the temporal buffers substantially increase the number of intersections compared to the spatial buffers. While the total number of intersections between the FRP products and the ABR dataset is 3,410, adding spatial buffers of 10m and 100m, results in an overall increase of 1% and 13%, respectively, compared to the origininal dataset. Instead, applying a temporal buffer of ±1 day, increases intersections by 171%, rising to 174% and 205% when combined with the spatial buffers of 10m and 100m, respectively. The effect of a temporal buffer of ±1 week is even more pronounces, increasing the intersections by 1302%, and respectively 1,314% and 1,438% when combined with both 10m and 100m spatial buffers. As for the individual sensors, this increase results even greater for SEVIRI, followed by VIIRS and MODIS.

As for the unique burning request analysis (

Table 5), we observe a similar effect from the different buffering parameters. Introducing 10m and 100m spatial buffers results in increases of 1% and 14%, respectively, while applying ±1 day and ±1 week temporal buffers alone leads to increases of 143% and 972%. When combining a 10m spatial buffer with ±1 day and ±1 week buffers, the increases reach 147% and 982%, respectively, whereas a 100m buffer combined with ±1 day and ±1 week rises to 173% and 1,077%. The impact of both spatial and temporal buffers is more pronounced for standard burnings than for extensive burnings, with maximum increases of 1,182% and 92%, respectively, under the ±1 week and 100m buffer configurations. Comparing

Table 4 with

Table 5 shows that the total number of detections is substantially higher than the unique number of requests.

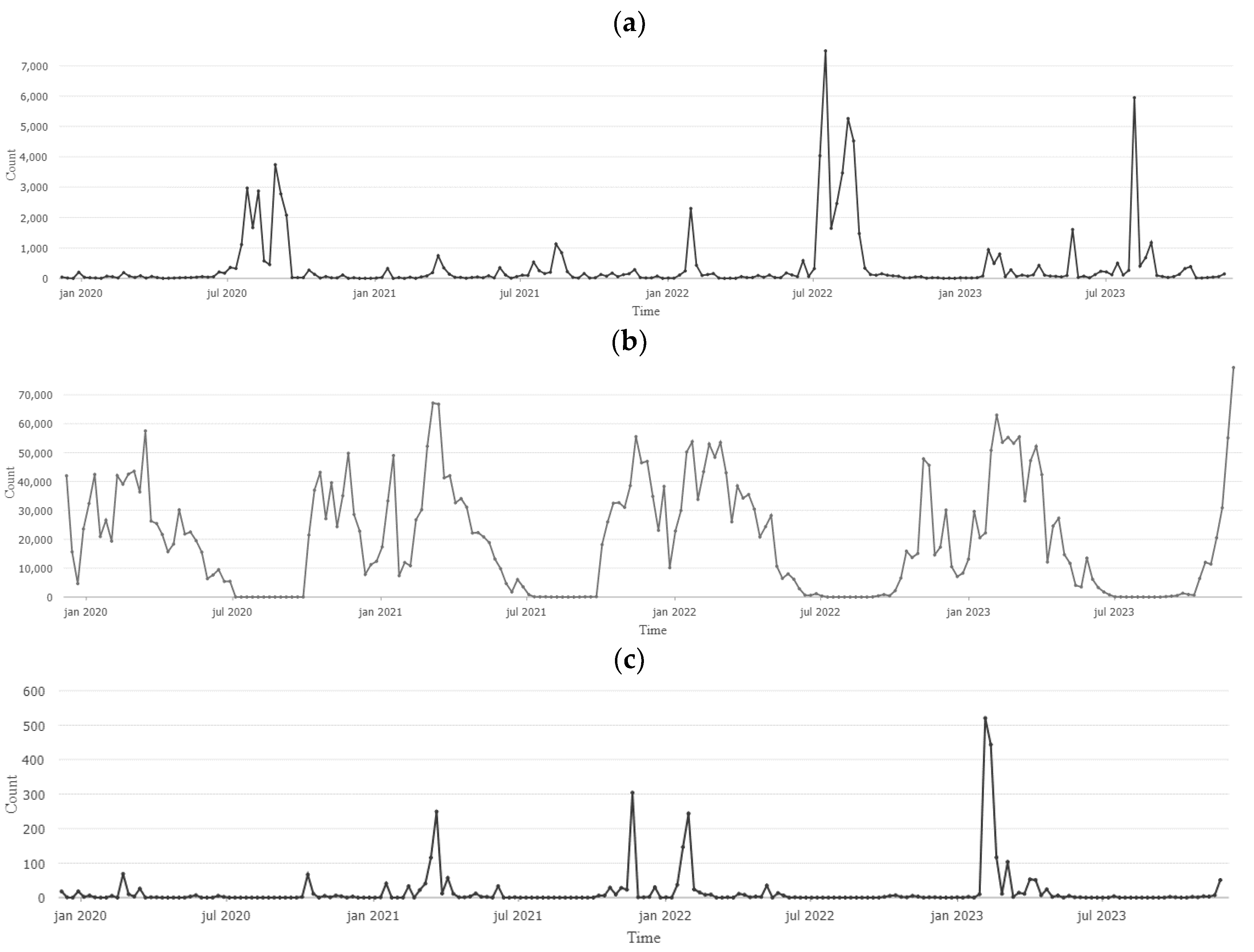

Figure 5 presents a comparison between the time series of Active Fire detections and the ABR database, highlighting their overall intersections (without any spatial or temporal buffers). From the analysis of

Figure 5a, we observe a significant number of fire detections during the summer months of 2023, 2020, and 2022 (mainly in July and August), as well as a secondary period of high frequency after January 2023. In contrast, in of

Figure 5b, the ABR data appears more evenly distributed, with peak activity occurring from late autumn to early spring (October to May). The overall intersections between both datasets (

Figure 5c) show significantly lower counts but tend to follow the same seasonal pattern as the ABR database, with peaks occurring from late autumn to spring. However, certain months with high ABR counts (e.g., November-December 2022), do not show a corresponding increase in the intersection series.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the different FRP instruments and times of day when intersections with the ABR occur (again without any buffers). Among VIIRS and MODIS, most detections occur from morning to early afternoon, corresponding to the acquisition times of most instruments. Another period of detection is observed during early dawn (02:00 to 03:30), particularly from NOAA-20 and S-NPP. For the remainder of the day, SEVIRI is the only instrument detecting active fires, with the highest detection period generally occurring between 16:00 and 23:30. In terms of FRP magnitude, SEVIRI records the highest values, followed by MODIS/Aqua and VIIRS (S-NPP amd NOAA-20).

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the capability of various remote sensing products to detect small-scale agricultural fires and prescribed fire interventions.

In the local-scale case study of Terras de Bouro, which involved multiple extensive agricultural burnings, we found a strong spatial correlation between FRP products from all instruments considered (VIIRS, MODIS, SLSTR, and SEVIRI) and the Daytime Active Fire Detection Algorithm applied to a Landsat 9 OLI-2 scene (at 30m spatial resolution). Despite implementing the [

18] algorithm to a Landsat 9 OLI-2 scene, using the same numerical conditional values originally indicated for Landsat 8 OLI, we were still successful in detecting a potential daytime active fire. Additionally, we observed a good correlation with post-fire analysis, including the MINDED-FBA results derived from surface reflectance products of Landsat 8 and 9 scenes (also at 30 m resolution). The extent of the burned areas was further confirmed by the official yearly burned area dataset from ICNF, which attributes most of these fires to negligent extensive burnings for pasture management. However, when comparing to the Agriculture Burning Request dataset, the correspondence was more limited and concentrated primarily in extensive burning requests.

For the Póvoa de Varzim case study, which focused on a smaller area with a low-intensity controlled prescribed fire for fuel management, carried out over two days, we found that only VIIRS (S-NPP and NOAA-20) detected active fires. This suggests that, despite the small scale of the event—especially on March 2, when the burned area was approximately 3,400 m²—VIIRS S-NPP successfully detected the fire, even though the event's size was several times smaller than the instrument's pixel resolution (375 m, corresponding to an area of over 140,000 m²). Other FRP products from MODIS, SLSTR, and SEVIRI failed to fire on either day, likely due to insufficient spatial resolution for such small events.

Although the ICNF yearly burned area dataset was unavailable for this case, fire-related changes were identified using the MINDED-FBA tool and Sentinel-2 imagery (with 20 m spatial resolution). Despite detecting several high-magnitude changes within the known burned area, these classification results are likely not indicative of high burn severity. Indeed, the small extent of the study area may exacerbate the weight of fire-related changes relative to the overall image statistics (hence affecting the results of automatic thresholding). Additionally, the MINDED-FBA outputs included also low-magnitude changes that should not be related to fires but are instead caused by land-use changes related to plowing. This indicates that, despite the pre-processing steps, the tool is still sensitive to producing false positives in such cases, which is anyway to be expected, as this is a non-supervised classification method. Nevertheless, the MINDED-FBA tool seems to effectively resolve much of the salt-and-pepper noise, as these pixels are classified as ‘Mixed.’

Regarding the Agriculture Burning Request database from ICNF, the Póvoa de Varzim case study only includes one record corresponding to this event. Such findings suggest that, as may be the case with many similar instances, these practices do not always occur at the exact requested locations and dates, whether due to unfavorable conditions or user-induced inconsistencies. Therefore, these findings justify the introduction of additional considerations in the subsequent systematic analysis of mainland Portugal.

This national-scale analysis of Portugal’s mainland was conducted for the period from 2019 to 2023. In this analysis, we identified a significant number of correspondences when intersecting the FRP and ABR databases (

Figure 5 and

Table 4). To account for potential spatial and temporal inaccuracies in the ABR dataset, we applied spatial buffers of 10m and 100m to the ABR coordinates, along with temporal buffers of ±1 day and ±1 week relative to the ABR entry dates. These assumptions resulted in a substantial increase in the number of intersections with the FRP products, with the temporal buffer yielding a much larger increase compared to the two spatial buffer scenarios. Nevertheless, the maximum total number of potentially detected individual requests—16,141 (with a 100m buffer and ±1 week)—remains significantly lower (less then 1%) than the total number of requests recorded in the ABR dataset for the 2019-2023 period (4,099,487). This discrepancy is likely due to the following conditions:

Not every request resulting into an actual burning;

Inconsistencies in the reported location coordinates and/or dates (extending beyond the considered spatial and temporal buffers);

Non-favorable cloudy conditions during the satellite image acquisition, which may prevent accurate or any FRP measurements;

Insufficient spatial and/or temporal resolutions of the acquiring sensors;

A combination of one or more of the above-mentioned conditions.

By considering the best available reference datasets for both agriculture burning requests and official yearly burned areas, both provided by INCF, the results of this study highlight the benefits and limitations of using remote sensing products for detecting small agriculture.

For example, it seems that for Portugal mainland, the current setup of satellites capable of producing FRP with sub-1 km spatial resolutions, is mostly concentrated during the daytime. The remaining periods are in some cases, only covered by SEVIRI, which includes the worst spatial resolution among the instruments considered (i.e., 3km). Despite their spatial resolution limitations, we found the lowest resolution sensors – SEVIRI and MODIS – resulted in the highest FRP magnitudes [MW].

For systematic analysis of small agricultural fires, such as the recurrent practices of burning in Portugal, FRP products seem to be particularly effective for detecting extensive burnings, such as those used for pasture creation. However, for smaller and low severity events, such as those observed in the Póvoa de Varzim case study, higher-resolution satellite data can progressively detect smaller fires. In particular, the VIIRS satellites offer the best compromise between temporal and spatial resolutions. Nevertheless, the Póvoa de Varzim prescribed fire is still considerably larger than many agriculture small-scale burning events, such as those involving pile burning of biomass residues, which are typically only a few meters wide.

As shown by [

18], such small-scale piles could, in theory, be detected with the Active Fire Detection Algorithm using OLI sensor images. However, the combined revisit time of Landsat 8 and 9 (8 days) is insufficient to consistently detect the majority of these events, as they tend to have small spatial extents and short durations. Nevertheless, including some detections may still represent an advance over current air quality models. In the future, it would be valuable to explore how FRP data could be used in conjunction with the ABR database to create prediction models for small-scale fire events. This would require systematic ground-level truth checking, improved temporal and spatial accuracy of the ABR database, and more detailed descriptions of each record.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the capabilities of various remote sensing products and approaches for detecting small-scale fires. The analysis of two local case studies shows that active fire detection products, specifically fire radiative power from VIIRS, MODIS, SLSTR, and SEVIRI, have strong spatial correlations with higher-resolution data, including both active fire detections and post-burned analysis from Landsat 8, Landsat 9, and Sentinel-2. However, limitations are also found, particularly in detecting small-scale agriculture fires. Fire radiative power products appear most effective for detecting extensive burnings, such as those used for land clearing and pasture creation. Additionally, this study analyzes two consecutive small-scale prescribed fires. Although these fires differ in purpose and typically occur under more controlled conditions, they further confirm that detecting smaller-scale active fires becomes progressively more dependent on the spatial resolution of each product. Among the tested products, VIIRS-equipped satellites offer the best compromise between temporal and spatial resolutions among the tested FRP products.

In addition to the local case studies, a systematic national-level analysis intersecting multiple active fire detection products with a national agricultural burning request database revealed limited correspondence. Such analysis included the application of spatial and temporal buffers to account for potential discrepancies in the agriculture burning request dataset, which significantly increased intersections, although they still represented less than 1% of the total unique request entries. Nevertheless, this agricultural burning request dataset, while the best available, does not represent actual ground-truth validation, as not all requests result in burnings, and many unregistered negligent burnings occur.

Despite these limitations, even partial detections have the potential to be valuable for multiple purposes, such as regulatory monitoring, wildfire risk management, and refining atmospheric emission estimates—ultimately leading to more accurate air quality assessments. Future efforts could explore how active fire detection products could be combined with agriculture burning request databases to develop predictive models for small-scale fire events. This would require systematic ground-level validation, improvements in the temporal and spatial precision of the request database, and more comprehensive descriptions of each entry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O. and C.G.; methodology, E.O., B.S. and C.G.; software, E.O. and B.S..; validation, E.O. and B.S.; formal analysis, E.O. and B.S.; investigation, E.O., B.S., D.L., S.C. and C.G.; resources, F.A., L.D. and C.G.; data curation, E.O., B.S. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O., B.S. and C.G.; writing—review and editing, E.O., B.S., D.L., S.C., F.A., L.D. and C.G.; visualization, E.O., B.S., C.G.; supervision, E.O., D.L., F.A., L.D. and C.G.; project administration, D.L. and C.G.; funding acquisition, D.L., S.C. and C.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through national funds within the projects PRUNING (DOI: 10.54499/2022.01045.PTDC) and FirEProd (DOI: 10.54499/PCIF/MOS/0071/2019), as well as the research contract granted to Carla Gama (DOI: 10.54499/2021.00732.CEECIND/CP1659/CT0006), and the CESAM Associated Laboratory (UIDP/50017/2020 + UIDB/50017/2020 + LA/P/0094/2020). The authors also acknowledge the support provided by the ERA Chair BESIDE project, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program under grant agreement No. 951389 (DOI: 10.3030/951389).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas (ICNF) for providing access to the national database of agricultural burning requests for mainland Portugal. The authors also thank RAIZ - Instituto da Floresta e Papel for the support in the establishment and trials monitoring, and Portucalea Forest Association for the support mainly related to providing the study area, for conducting the prescribed fire operation, and for their assistance in establishing, measuring, and maintaining the field experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Webb, J.; Hutchings, N.; Amon, B.; Nielsen, O.-K.; Phillips, R.; Dämmgen, U. Field Burning of Agricultural Residues. EMEP/EEA Emiss. Invent. Guideb. 2013 2013, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.E.B.; Pacheco, A.P.; Teixeira, J.G. Systematising Experts’ Understanding of Traditional Burning in Portugal: A Mental Model Approach. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2023, 32, 1558–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H. Fire Effects on Soils: The Human Dimension. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, J.; Palheiro, P.; Loureiro, C.; Ascoli, D.; Esposito, A.; Fernandes, P.M. Fire-Severity Mitigation by Prescribed Burning Assessed from Fire-Treatment Encounters in Maritime Pine Stands. Can. J. For. Res. 2019, 49, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, C.C.; Viegas, D.X.; Mendes, J.M.; Em, M.; Sociais, D.; Naturais, R.; Catedrático, P.; Auxiliar, P. Avaliação Do Risco de Incêndio Florestal No Concelho de Arganil. Silva Lusit. 2011, 19, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ye, J.; Zheng, J. Hourly Emissions of Air Pollutants and Greenhouse Gases from Open Biomass Burning in China during 2016–2020. Sci. Data 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Caravaca, A.; Vicente, E.D.; Figueiredo, D.; Evtyugina, M.; Nicolás, J.F.; Yubero, E.; Galindo, N.; Ryšavý, J.; Alves, C.A. Gaseous and Aerosol Emissions from Open Burning of Tree Pruning and Hedge Trimming Residues: Detailed Composition and Toxicity. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.A.; Vicente, E.D.; Evtyugina, M.; Vicente, A.; Pio, C.; Amado, M.F.; Mahía, P.L. Gaseous and Speciated Particulate Emissions from the Open Burning of Wastes from Tree Pruning. Atmos. Res. 2019, 226, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Evtyugina, M.; Alves, C.; Monteiro, C.; Pio, C.; Tomé, M. Organic Particulate Emissions from Field Burning of Garden and Agriculture Residues. Atmos. Res. 2011, 101, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P.; Bodin, S.; Gittelson, A.; Kinney, S.; McCarty, J.L.; Stevenson, G.; Albertengo, J. Fire in the Fields: Moving Beyond the Damage of Open Agricultural Burning on Communities, Soil, and the Cryosphere Fire in the Fields: Moving Beyond the Damage of Open Agricultural Burning on Communities, Soil, and the Cryosphere A CCAC Project Summary Report: Impacts and Reduction of Open Burning in the Andes, Himalayas-and Globally Co-Authors for ICCI: Fire in the Fields: Moving Beyond the Damage of Open Agricultural Burning on Communities, Soil, and the Cryosphere. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Girona-García, A.; Lopes, A.R.; Keizer, J.J.; Vieira, D.C.S. Prediction, Validation, and Uncertainties of a Nation-Wide Post-Fire Soil Erosion Risk Assessment in Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Raposo, M.A.M.; Meireles, C.I.R.; Gomes, C.J.P.; Ribeiro, N.M.C.A. The Impact of Rural Fires on the Development of Invasive Species: Analysis of a Case Study with Acacia Dealbata Link. in Casal Do Rei (Seia, Portugal). Environ. - MDPI 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Frey, G.E.; Sun, C. Regulation and Practice of Forest-Management Fires on Private Lands in the Southeast United States: Legal Open Burns versus Certified Prescribed Burns. J. For. 2020, 118, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Botelho, H.S. A Review of Prescribed Burning Effectiveness in Fire Hazard Reduction. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2003, 12, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmielowski, T.L.; Carter, S.K.; Spaul, H.; Helmers, D.P.; Radeloff, V.C.; Zedler, P.H. Prioritizing Land Management Efforts at a Landscape Scale: A Case Study Using Prescribed Fire in Wisconsin. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 26, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, M.A.; Chitale, V.S.; Murthy, M.S.R.; Uddin, K.; Bajracharya, B.; Pradhan, S. Understanding Forest Fire Patterns and Risk in Nepal Using Remote Sensing, Geographic Information System and Historical Fire Data. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2017, 26, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, W.; Oliva, P.; Giglio, L.; Csiszar, I.A. The New VIIRS 375m Active Fire Detection Data Product: Algorithm Description and Initial Assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 143, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, W.; Oliva, P.; Giglio, L.; Quayle, B.; Lorenz, E.; Morelli, F. Active Fire Detection Using Landsat-8/OLI Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, L.; Camia, A.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J. A Comparison of Remote Sensing Products and Forest Fire Statistics for Improving Fire Information in Mediterranean Europe. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 48, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavzoglu, T.; Erdemir, M.Y.; Tonbul, H. Evaluating Performances of Spectral Indices for Burned Area Mapping Using Object-Based Image Analysis. 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chuvieco, E.; Martín, M.P.; Palacios, A. Assessment of Different Spectral Indices in the Red-near-Infrared Spectral Domain for Burned Land Discrimination. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2002, 23, 5103–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.; Disperati, L.; Alves, F.L. A New Method ( MINDED-BA ) for Automatic Detection of Burned Areas Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanianfard, D.; Parente, J.; Gonzalez-Pelayo, O. ; Akli Benali Multidecadal Satellite-Derived Portuguese Burn Severity Atlas (1984-2022). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, E.; Colaço, M.C.; Fernandes, P.M.; Sequeira, A.C. Remains of Traditional Fire Use in Portugal: A Historical Analysis. Trees, For. People 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.H.; Valente, J.; Cascão, P.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Viegas, D.X.; Ottmar, R.; Miranda, A.I. Near-Source Grid-Based Measurement of CO and PM2.5 Concentration during a Full-Scale Fire Experiment in Southern European Shrubland. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 145, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.I.; Martins, V.; Cascão, P.; Amorim, J.H.; Valente, J.; Tavares, R.; Borrego, C.; Tchepel, O.; Ferreira, A.J.; Cordeiro, C.R.; et al. Monitoring of Firefighters Exposure to Smoke during Fire Experiments in Portugal. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.A.; O’Neill, S.M.; Larkin, N.K.; Holder, A.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Halofsky, J.E.; Rappold, A.G. Wildfire and Prescribed Burning Impacts on Air Quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 583–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF Cartografia Nacional de Áreas Ardidas Dos Anos 1975 à Data Atual Em Conformidade Com o Disposto No n.o 5 Do Art.o 2.o Do Decreto-Lei n.o 124/2006, de 28 de Junho, Na Redação Dada Pelo Decreto-Lei n.o 17/2009, de 14 de Janeiro Available online: https://sigservices.icnf.pt/server/rest/services/BDG/areas_ardidas/MapServer.

- Wooster, M.J.; Roberts, G.J.; Giglio, L.; Roy, D.; Freeborn, P.; Boschetti, L.; Justice, C.; Ichoku, C.; Schroeder, W.; Davies, D.; et al. Satellite Remote Sensing of Active Fires: History and Current Status, Applications and Future Requirements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 267, 112694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA NASA Active Fire Data Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/learn/find-data/near-real-time/firms/active-fire-data.

- ESA SLSTR Products Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/slstr-products#S3-SLSTR-Products-L2-FRP-Products.

- Eumetsat LSA SAF Available online: https://datalsasaf.lsasvcs.ipma.pt/PRODUCTS/MSG/FRP-PIXEL/HDF5/.

- USGS Landsat 8 Data Users Handbook. EROS 2019, 8, 106.

- USGS Landsat 9 Data Users Handbook Landsat 9 Data Users Handbook Version 1.0. 2022, 107.

- NASA Layer Information: LANDSAT OLI (8 & 9) Fire and Thermal Anomalies (Day | Night, 30 Meters) Available online: https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/descriptions/FIRMS_Landsat_Firehotspots.html.

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A Review on Early Forest Fire Detection Systems Using Optical Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.; Disperati, L.; Alves, F.L. A New Method (MINDED-BA) for Automatic Detection of Burned Areas Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.; Disperati, L.; Alves, F.L. MINDED-FBA: An Automatic Remote Sensing Tool for the Estimation of Flooded and Burned Areas. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.R.; Disperati, L.; Cenci, L.; Pereira, L.G.; Alves, F.L. Multi-Index Image Differencing Method (MINDED) for Flood Extent Estimations. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA Sentinel-2 User Handbook; 2015; Vol. Rev2.

- APA Surface Water Bodies Rivers of Mainland Portugal: SNIAmb Spatial Data Set Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/massas-de-agua-superficiais-rios-de-portugal-continental-conjunto-de-dados-geografico-sniamb?locale=en.

- JAXA ALOS Global Digital Surface Model “ALOS World 3D - 30m (AW3D30)”. Available online: https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/dataset/aw3d30/aw3d30_e.htm (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- USGS Earth Explorer. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Copernicus Copernicus Browser Available online: https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).