Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

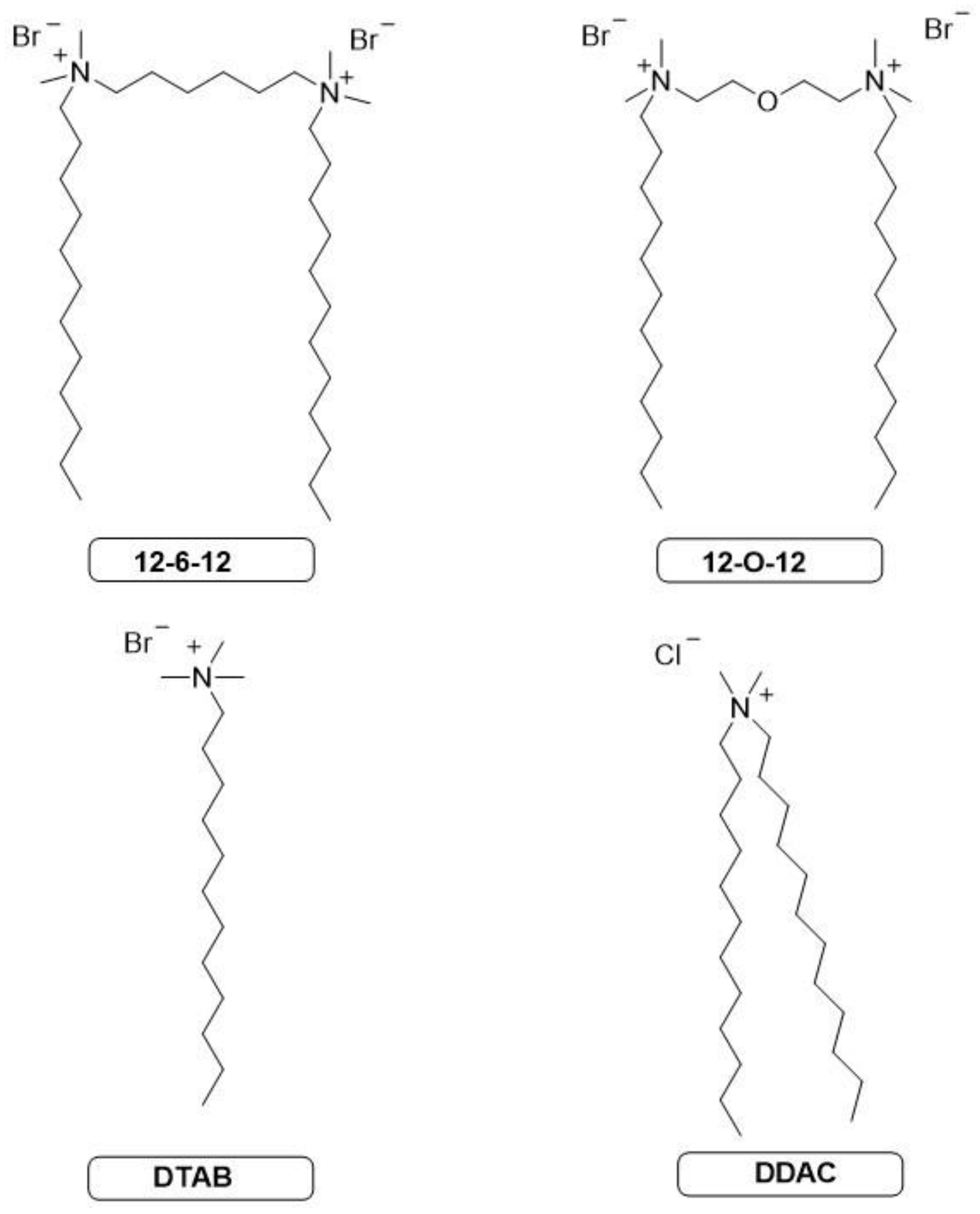

Cationic gemini surfactants are used due to their broad spectrum of activity, especially surface, anticorrosive and antimicrobial properties. Mixtures of cationic and anionic surfactants are also increasingly described. In order to investigate the effect of anionic additive on antimicrobial activity, experimental studies were carried out to obtain MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) against E. coli and S. aureus bacteria. Two gemini surfactants (12-6-12 and 12-O-12) and two single quaternary ammonium salts (DTAB and DDAC) were analyzed. The most commonly used commercial compounds of this class, i.e. SDS and SL, were used as anionic additives. In addition, computer quantum-mechanical studies were also carried out to confirm the relationship between the structure of the mixture and the activity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of Solutions of Catanionic Mixtures

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity

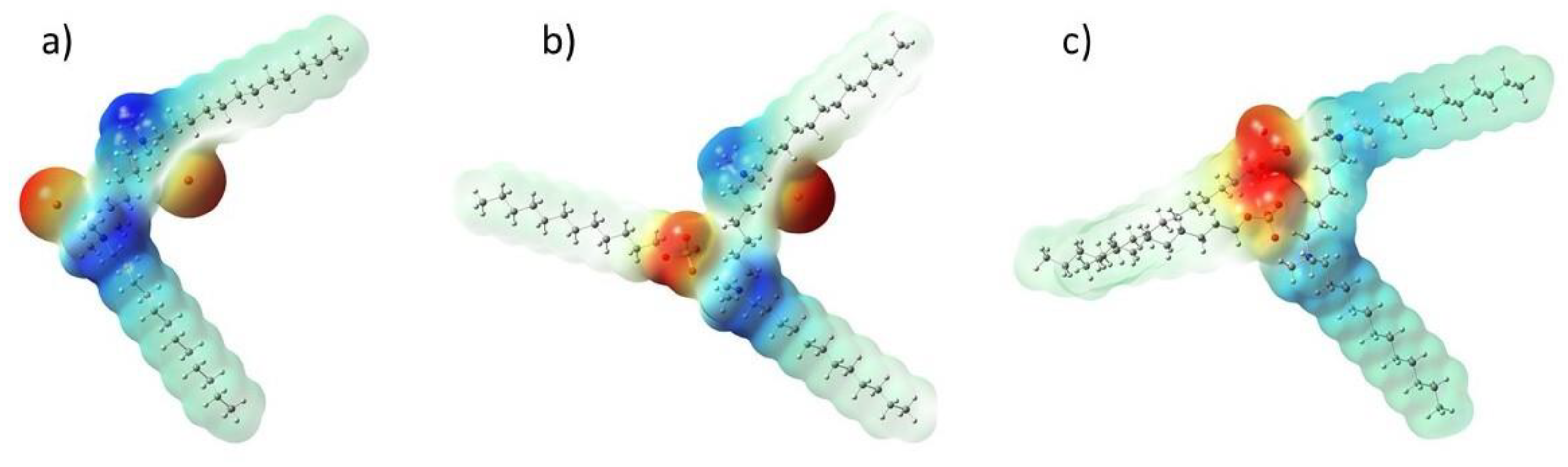

2.3. Quantum Mechanical Calculations

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

3.3. Computational Quantum Mechanical Modelling Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schramm, L.L.; Stasiuk, E.N.; Marangoni, D.G. 2 Surfactants and Their Applications. Annu Rep Prog Chem Sect C Phys Chem 2003, 99, 3–48. [CrossRef]

- Babajanzadeh, B.; Sherizadeh, S.; Hasan, R. Detergents and Surfactants: A Brief Review. Open Access J. Sci. 2019, 3, 94–99. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Antibacterial Surfaces: The Quest for a New Generation of Biomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 295–304. [CrossRef]

- Polarz, S.; Kunkel, M.; Donner, A.; Schlötter, M. Added-Value Surfactants. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18842–18856. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. A Review on the Biosurfactants: Properties, Types and Its Applications. J. Fundam. Renew. Energy Appl. 2018, 08. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, A.; Pramanik, N. Self-Assembly of Surfactants: An Overview on General Aspects of Amphiphiles. Biophys. Chem. 2020, 265, 106429. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Tyagi, R. Industrial Applications of Dimeric Surfactants: A Review. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2014, 35, 205–214. [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, M.; Machado, A.A. Surfactants as Biodegradable Sustainable Inhibitors for Corrosion Control in Diverse Media and Conditions: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168407. [CrossRef]

- Kralova, I.; Sjöblom, J. Surfactants Used in Food Industry: A Review. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2009, 30, 1363–1383. [CrossRef]

- Nazdrajic, S.; Bratovcic, A. The Role of Surfactants in Liquid Soaps and Its Antimicrobial Properties. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 7, 501–507. [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.; Szulc, A.; Brycka, J.; Kowalczyk, I. Properties and Applications of Quaternary Ammonium Gemini Surfactant 12-6-12: An Overview. Molecules 2023, 28, 6336. [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.M.; Keiper, J.S. Gemini Surfactants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1906–1920. [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.M.; Littau, C.A. Gemini-Surfactants: Synthesis and Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1451–1452. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.J.; Tracy, D.J. Gemini Surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 1998, 1, 547–554. [CrossRef]

- Alami, E.; Beinert, G.; Marie, P.; Zana, R. Alkanediyl-α,ω-Bis(Dimethylalkylammonium Bromide) Surfactants. 3. Behavior at the Air-Water Interface. Langmuir 1993, 9, 1465–1467. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Y. Aggregation Behavior of Gemini Surfactants and Their Interaction with Macromolecules in Aqueous Solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 1939–1956. [CrossRef]

- Mirgorodskaya, A.B.; Kudryavtseva, L.A.; Pankratov, V.A.; Lukashenko, S.S.; Rizvanova, L.Z.; Konovalov, A.I. Geminal Alkylammonium Surfactants: Aggregation Properties and Catalytic Activity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2006, 76, 1625–1631. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Gao, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Wei, W. Wettability and Adsorption of PTFE and Paraffin Surfaces by Aqueous Solutions of Biquaternary Ammonium Salt Gemini Surfactants with Hydroxyl. Colloids Surf. A 2016, 506, 416–424. [CrossRef]

- Pisárčik, M.; Jampílek, J.; Devínsky, F.; Drábiková, J.; Tkacz, J.; Opravil, T. Gemini Surfactants with Polymethylene Spacer: Supramolecular Structures at Solid Surface and Aggregation in Aqueous Solution. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 19, 477–486. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qiao, F.; Fan, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y. Interactions of Cationic/Anionic Mixed Surfactant Aggregates with Phospholipid Vesicles and Their Skin Penetration Ability. Laqngmuir 2017, 33, 2760–2769. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yan, H.; Ma, W.; Li, Y. Complex Formation between Cationic Gemini Surfactant and Sodium Carboxymethylcellulose in the Absence and Presence of Organic Salt. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 509, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cao, X.-L.; Guo, L.-L.; Xu, Z.-C.; Zhang, L.; Gong, Q.-T.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Effect of Molecular Structure of Catanionic Surfactant Mixtures on Their Interfacial Properties. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 509, 601–612. [CrossRef]

- Varade, D.; Carriere, D.; Arriaga, L.R.; Fameau, A.-L.; Rio, E.; Langevin, D.; Drenckhan, W. On the Origin of the Stability of Foams Made from Catanionic Surfactant Mixtures. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 6557. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Qi, W.; Ma, C.; Wu, T.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, S.; Qi, J.; Yan, Y.; Huang, J. The High-Concentration Stable Phase: The Breakthrough of Catanionic Surfactant Aqueous System. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129120. [CrossRef]

- Kaler, E.W.; Murthy, A.K.; Rodriguez, B.E.; Zasadzinski, J.A.N. Spontaneous Vesicle Formation in Aqueous Mixtures of Single-Tailed Surfactants. Science 1989, 245, 1371–1374. [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, E.; Uygur, N.; Topcu, G.; Lavrentovich, O.D.; Figueiredo Neto, A.M. Gemini Surfactant Behavior of Conventional Surfactant Dodecyltrimethylammonium Bromide with Anionic Azo Dye Sunset Yellow in Aqueous Solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119556. [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Geng, T. Synergistic Effects of Gemini Cationic Surfactants with Multiple Quaternary Ammonium Groups and Anionic Surfactants with Long EO Chains in the Mixed Systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 376, 121427. [CrossRef]

- Azum, N.; Rub, M.A.; Asiri, A.M.; Khan, A.A.P.; Khan, A. Physico-Chemical Investigations of Mixed Micelles of Cationic Gemini and Conventional Surfactants: A Conductometric Study. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2013, 16, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- La Mesa, C.; Risuleo, G. Surface Activity and Efficiency of Cat-Anionic Surfactant Mixtures. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 790873. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, A.; Pramanik, N.; Ambade, B. Can a Catanionic Surfactant Mixture Act as a Drug Delivery Vehicle? Comptes Rendus Chim. 2016, 19, 951–954. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, L.; He, D.; Lu, R.; Xie, Y.; Lai, L. Cationic-Anionic Surfactant Mixtures Based on Gemini Surfactant as a Candidate for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 677, 132297. [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.E.; Kowalczyk, I.H.; Szulc, A.; Kaczerewska, O.; Pakiet, M. Multifunctional Gemini Surfactants: Structure, Synthesis, Properties and Applications. In Application and Characterization of Surfactants; Najjar, R., Ed.; InTech, 2017 ISBN 978-953-51-3325-4.

- Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yin, J.; Hu, M. Antibacterial Mechanism of Octamethylene-1,8-Bis(Dodecyldimethylammonium Bromide) Against E. Coli. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2017, 20, 717–723. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.C.; Buttaro, B.A.; Minbiole, K.P.C.; Wuest, W.M. Bioorganic Investigation of Multicationic Antimicrobials to Combat QAC-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 304–309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ding, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Lei, Q.; Fang, W. Antibacterial Activity, in Vitro Cytotoxicity, and Cell Cycle Arrest of Gemini Quaternary Ammonium Surfactants. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12161–12169. [CrossRef]

- Kralova, K.; Kallova, J.; Loos, D.; Devinsky, F. Correlation between Biological Activity and the Structure of N,N’-Bis(Alkyldimethyl)-1,6-Hexanediammonium Dobromides. Antibacterial Activity and Inhibition of Photochemical Activity of Chloroplasts. Pharmazie 1994, 49, 857–858.

- Devínsky, F.; Kopecka-Leitmanová, A.; Šeršeň, F.; Balgavý, P. Cut-off Effect in Antimicrobial Activity and in Membrane Perturbation Efficiency of the Homologous Series of N,N-Dimethylalkylamine Oxides. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990, 42, 790–794. [CrossRef]

- Khodsiani, M.; Kianmehr, Z.; Brycki, B.; Szulc, A.; Mehrbod, P. Evaluation of the Antiviral Potential of Gemini Surfactants against Influenza Virus H1N1. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 184. [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.E.; Szulc, A.; Kowalczyk, I.; Koziróg, A.; Sobolewska, E. Antimicrobial Activity of Gemini Surfactants with Ether Group in the Spacer Part. Molecules 2021, 26, 5759. [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, L.Y.; Pashirova, T.N.; Doktorovova, S.; Fernandes, A.R.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Silva, A.M.; Souto, S.B.; Souto, E.B. Cationic Surfactants: Self-Assembly, Structure-Activity Correlation and Their Biological Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5534. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Ch.; Wang, Y. Structure–activity relationship of cationic surfactants as antimicrobial agents. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 2020, 45, 28–43. [CrossRef]

- Colomer, A.; Pinazo, A.; Manresa, M. A.; Vinardell, M. P.; Mitjans, M.; Infante, M. R.; Pérez L. Cationic Surfactants Derived from Lysine: Effects of Their Structure and Charge Type on Antimicrobial and Hemolytic Activities. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2011 54 (4), 989-1002. [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, A.R.; Hosseinzadeh, P., Solouk, A.; Akbari, S.;. Szulc, A.M.; Brycki, B.E. Cationic gemini surfactant properties, its potential as a promising bioapplication candidate, and strategies for improving its biocompatibility: A review. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2022, 299, 102581. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Vaiwala, R.; Parthasarathi, S.; Patil, N.; Verma, A.; Waskar, M.; Raut, J.S.; Basu, J.K. Ayappa. K.G. Interactions of Surfactants with the Bacterial Cell Wall and Inner Membrane: Revealing the Link between Aggregation and Antimicrobial Activity. Langmuir 2022, 38, 15714-15728. [CrossRef]

- Falk N.A., Surfactants as Antimicrobials: A Brief Overview of Microbial Interfacial Chemistry and Surfactant Antimicrobial Activity. J Surfact Deterg 2019, 22, 1119–1127. [CrossRef]

- Cserha´ti, T.; Forga´cs, E.; Oros G. Biological activity and environmental impact of anionic surfactants. Environment International 2002, 28, 337 – 348. [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B. Gemini Alkylammonium Salts as Biodeterioration Inhibitors. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 227–231. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; Pinazo, A.; Morán, M.C.; Pons, R. Aggregation Behavior, Antibacterial Activity and Biocompatibility of Catanionic Assemblies Based on Amino Acid-Derived Surfactants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8912. [CrossRef]

- Nagabalasubramanian, P.B.; Karabacak, M.; Periandy, S. Vibrational Frequencies, Structural Confirmation Stability and HOMO–LUMO Analysis of Nicotinic Acid Ethyl Ester with Experimental (FT-IR and FT-Raman) Techniques and Quantum Mechanical Calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2012, 1017, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kirishnamaline, G.; Magdaline, J.D.; Chithambarathanu, T.; Aruldhas, D.; Anuf, A.R. Theoretical Investigation of Structure, Anticancer Activity and Molecular Docking of Thiourea Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1225, 129118. [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Laurence, P.R.; Jayasuriya, K. Molecular Electrostatic Potentials: An Effective Tool for the Elucidation of Biochemical Phenomena. Environ. Health Perspect. 1985, 61, 191–202. [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.; Kowalczyk, I.; Kozirog, A. Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Spectral Properties and Antifungal Activity of Polymethylene-α,ω-Bis(N,N-Dimethyl-N-Dodecyloammonium Bromides). Molecules 2011, 16, 319–335. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01 2016.

- Austin, A.; Petersson, G.A.; Frisch, M.J.; Dobek, F.J.; Scalmani, G.; Throssell, K. A Density Functional with Spherical Atom Dispersion Terms. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 4989–5007. [CrossRef]

- Foresman, J.B.; Frisch, A. Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods, Third Ed; Gaussian, Inc: Wallingford, CT USA, 2015., 2015;

- Hehre, W.J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P. v R.; Pople, J.A. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; Wiley: New York, 1986; Vol. 7;.

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. [CrossRef]

| No | volume of solutions [ml] | molar ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A11 | B12 | H2O | A1/B1 | B1/A1 | |

| 0 | 25 | 0 | 75 | - | - |

| 1 | 25 | 1 | 74 | 25 | 0.04 |

| 2 | 25 | 2 | 73 | 12.5 | 0.08 |

| 3 | 25 | 5 | 70 | 5 | 0.2 |

| 4 | 25 | 10 | 65 | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 25 | 20 | 55 | 1.25 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 25 | 30 | 45 | 0.83 | 1.2 |

| 7 | 25 | 40 | 35 | 0.625 | 1.6 |

| 8 | 25 | 50 | 25 | 0.50 | 2 |

| 9 | 25 | 60 | 15 | 0.42 | 2.4 |

| 10 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 0.33 | 3 |

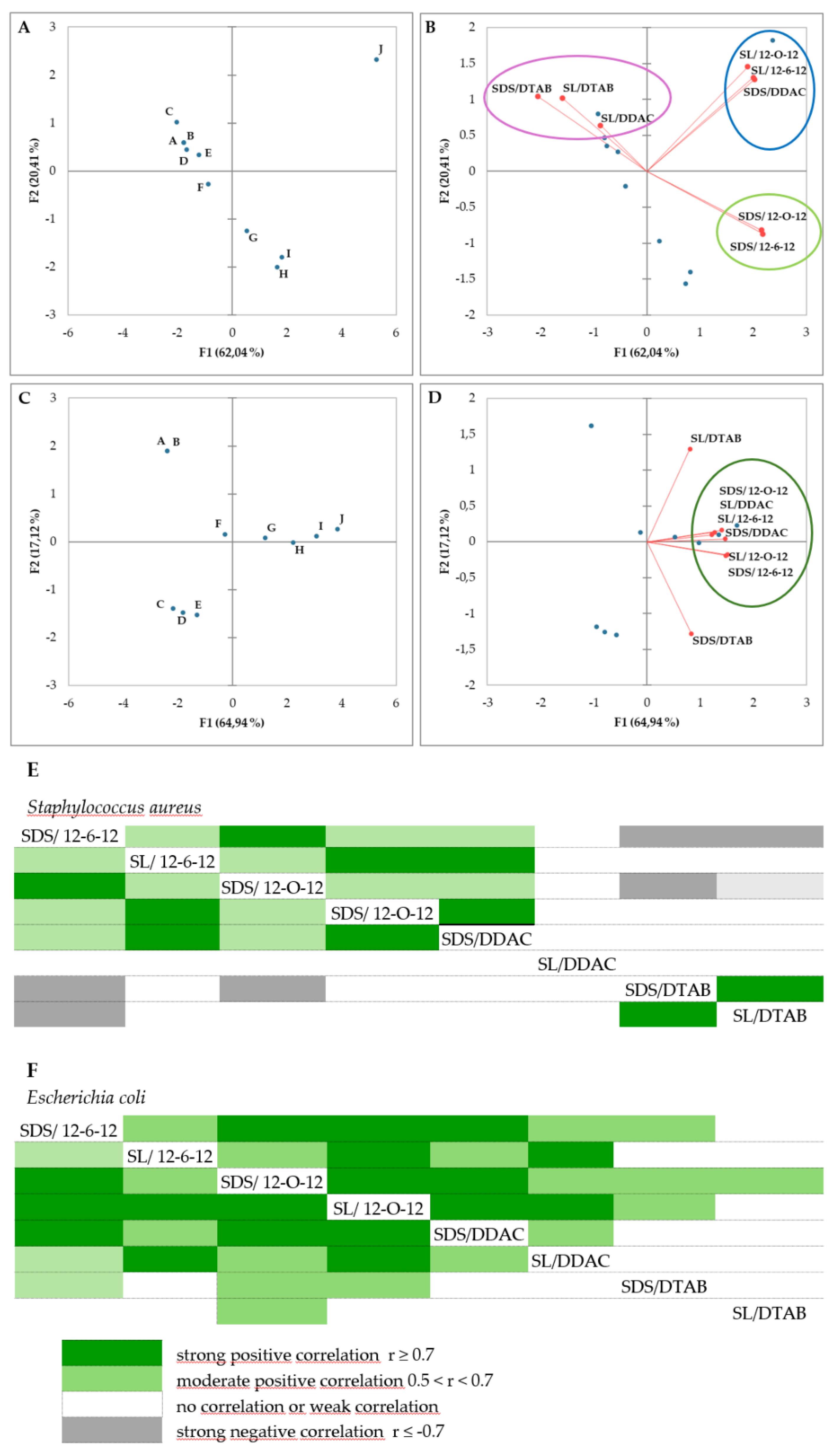

| No | SDS/ 12-6-12 | SL/ 12-6-12 | SDS/ 12-O-12 | SL/ 12-O-12 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | |

| 0 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 |

| 1/A | 0.007813 | 0.007813 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 |

| 2/B | 0.007813 | 0.007813 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 |

| 3/C | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 |

| 4/D | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 |

| 5/E | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 |

| 6/F | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.015625 | 0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 |

| 7/G | 0.03125 | 0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | >0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 |

| 8/H | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.03125 | 0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.0625 |

| 9/I | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.015625 | 0.03125 | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.007813 | 0.0625 |

| 10/J | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.0625 | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | >0.0625 | 0.03125 | >0.0625 |

| No | SDS/DDAC | SL/DDAC | SDS/DTAB | SL/DTAB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | S. aureus | E. coli | |

| 0 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 |

| 1/A | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 | 0.15625 | 0.625 |

| 2/B | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 | 0.15625 | 0.625 |

| 3/C | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.019531 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | >0.625 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 |

| 4/D | 0.004883 | 0.039063 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | >0.625 | 0.15625 | 0.3125 |

| 5/E | 0.019531 | 0.15625 | 0.019531 | 0.078125 | 0.15625 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | 0.3125 |

| 6/F | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.15625 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | 0.625 |

| 7/G | 0.019531 | 0.625 | 0.009766 | 0.078125 | 0.078125 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | 0.625 |

| 8/H | 0.019531 | >0.625 | 0.009766 | 0.039063 | 0.078125 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | >0.625 |

| 9/I | 0.019531 | >0.625 | 0.009766 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | >0.625 |

| 10/J | 0.15625 | >0.625 | 0.009766 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | >0.625 | 0.078125 | >0.625 |

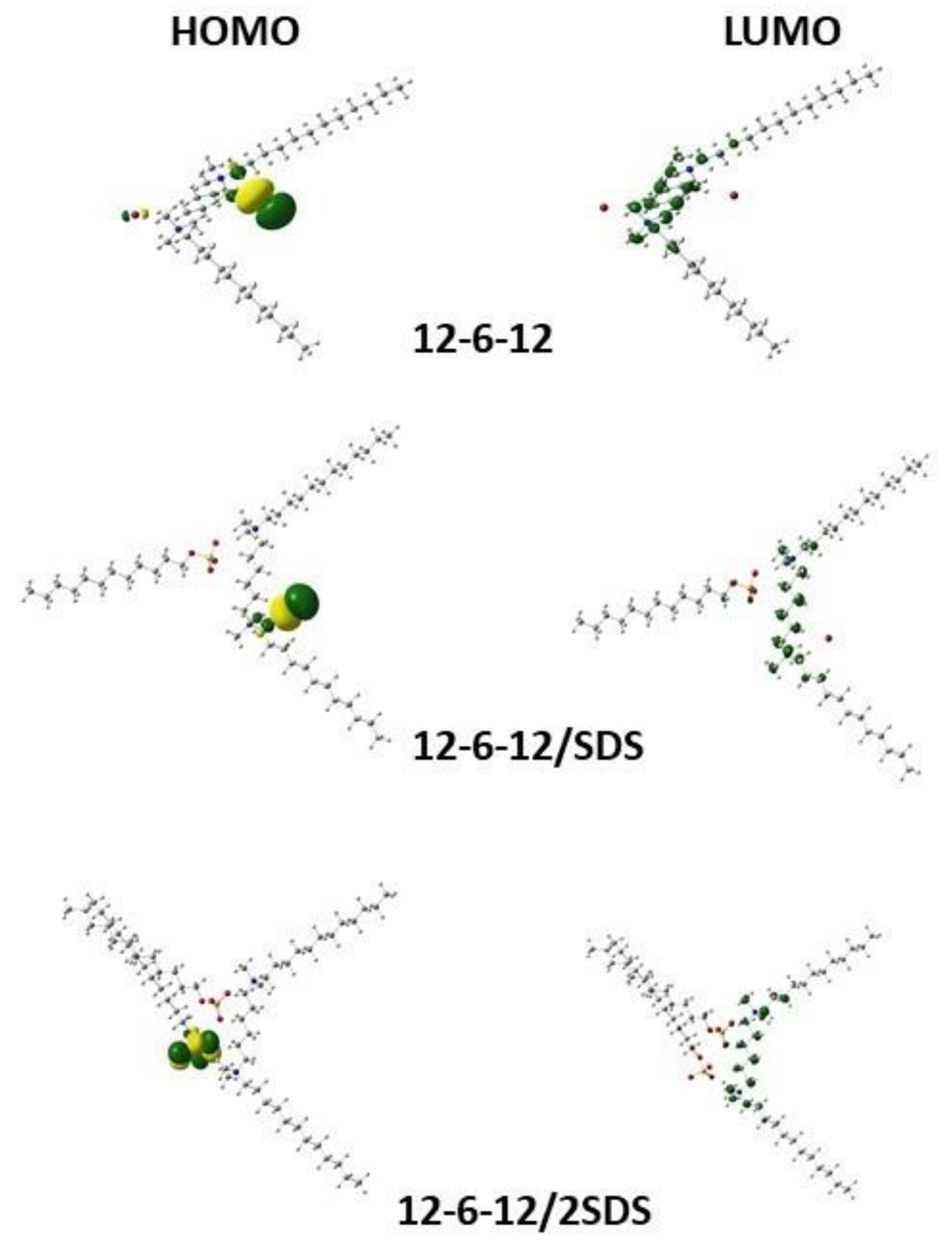

| Mixture | EHOMO [eV] | ELUMO [eV] | ΔEgap [eV] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12-6-12 | -6.5721 | -0.1355 | 6.4366 |

| 12-6-12/SDS | -6.5650 | -0.1268 | 6.4382 |

| 12-6-12/2SDS | -7.3441 | -0.1020 | 7.2420 |

| 12-6-12/SL | -6.3631 | -0.1268 | 6.2363 |

| 12-6-12/2SL | -6.3128 | -0.0952 | 6.2175 |

| 12-O-12 | -6.6418 | -0.1461 | 6.4956 |

| 12-O-12/SDS | -6.6208 | -0.1298 | 6.4910 |

| 12-O-12/2SDS | -7.4225 | -0.1094 | 7.3131 |

| 12-O-12/SL | -6.4162 | -0.1314 | 6.2847 |

| 12-O-12/2SL | -6.3729 | -0.1238 | 6.2491 |

| DDAC | -6.8790 | -0.0566 | 6.8224 |

| DDAC/SDS | -7.4777 | -0.0463 | 7.4314 |

| DDAC/2SDS | -7.4366 | -0.1902 | 7.2464 |

| DDAC/SL | -6.2970 | -0.0906 | 6.2064 |

| DDAC/2SL | -6.2769 | -0.1902 | 6.0866 |

| DTAB | -4.9987 | -0.9129 | 4.0858 |

| DTAB/SDS | -6.2788 | -0.7644 | 5.5144 |

| DTAB/2SDS | -7.1465 | -0.4874 | 6.6592 |

| DTAB/SL | -5.4806 | -0.6370 | 4.8436 |

| DTAB/2SL | -5.3759 | -1.2969 | 4.0790 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).