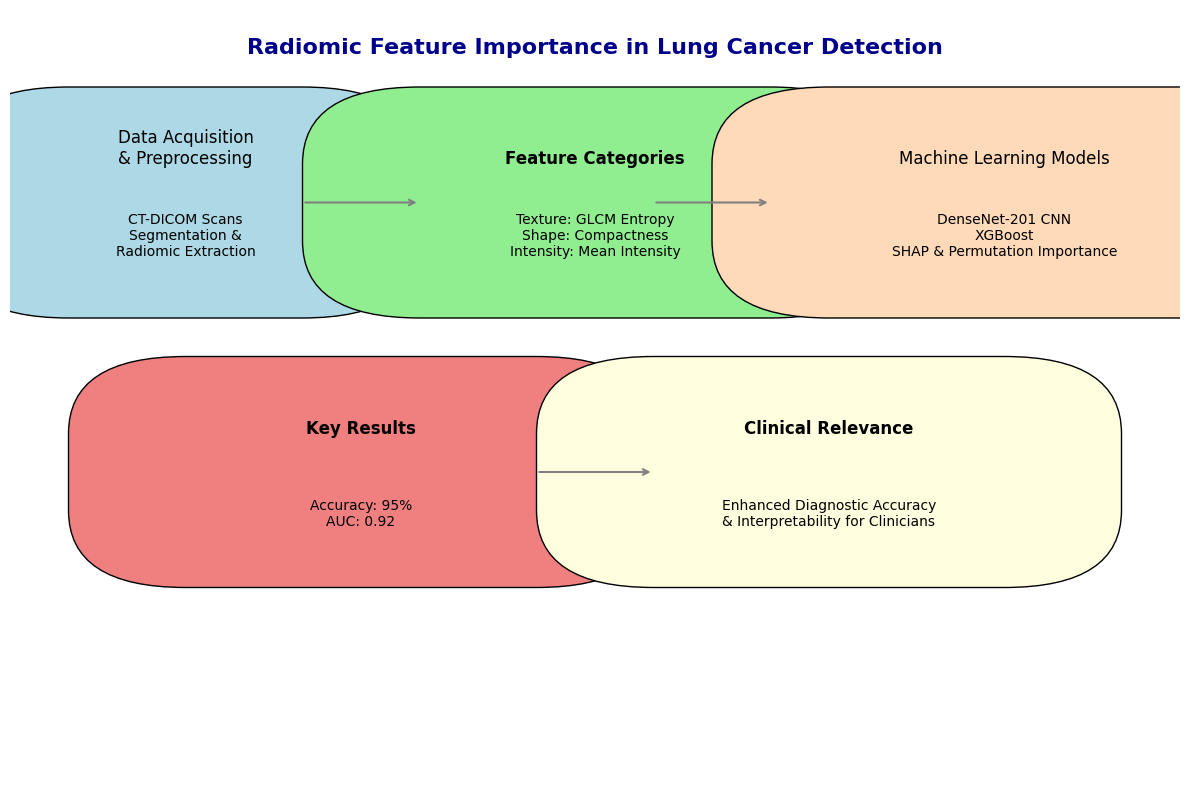

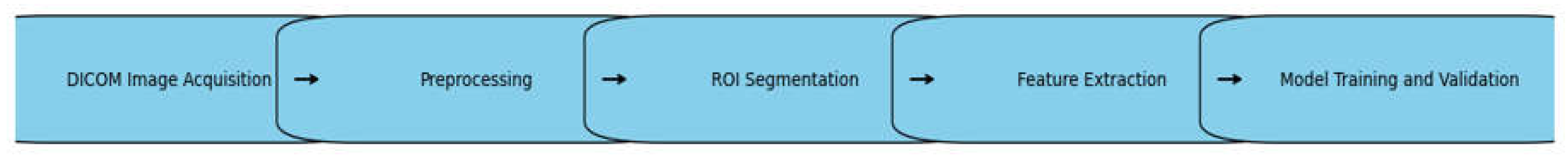

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

In the present work, one major and diverse CT-DICOM image dataset was considered, containing both verified lung cancer cases and normal controls. Altogether, this dataset was made up of 2,963 images relevant to lung cancer patients and 383 images relevant to healthy patients, derived from publicly available databases and clinical repositories from a medical center that collaborated with our laboratory

1, which included a diverse range of CT scans and radiographs of patients undergoing chest radiotherapy for various thoracic malignancies [

4,

6,

7]. Thereafter, the dataset was split into a validation set comprising 1,786 cancerous images and 337 healthy ones to ensure unbiased model performance across cohorts. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) provided some common parameters that can ensure the reproducibility and robustness of radiomic feature extraction [

8].

1 Laboratory: Medical Physics Department (MPD), The Medical Physics Department (MPD) at University Hospital, Larissa, Greece, is involved in clinical practice, research, and education. MPD offers clinical and research services related to patient diagnosis and treatment quality assurance programs, acceptance tests, and radiation protection issues.

It was taken as the guiding principle to establish the preprocessing pipeline. Besides, to ensure quality and eliminate all sorts of artifacts that may distort radiomic feature extraction, the images were carefully reviewed by qualified radiologists.

2.2. Radiomic Feature Extraction

In this paper, we describe the application of an intensive and standardized extraction using PyRadiomics, one of the most widely recognized and validated open-source software platforms developed specifically for radiomic analyses [

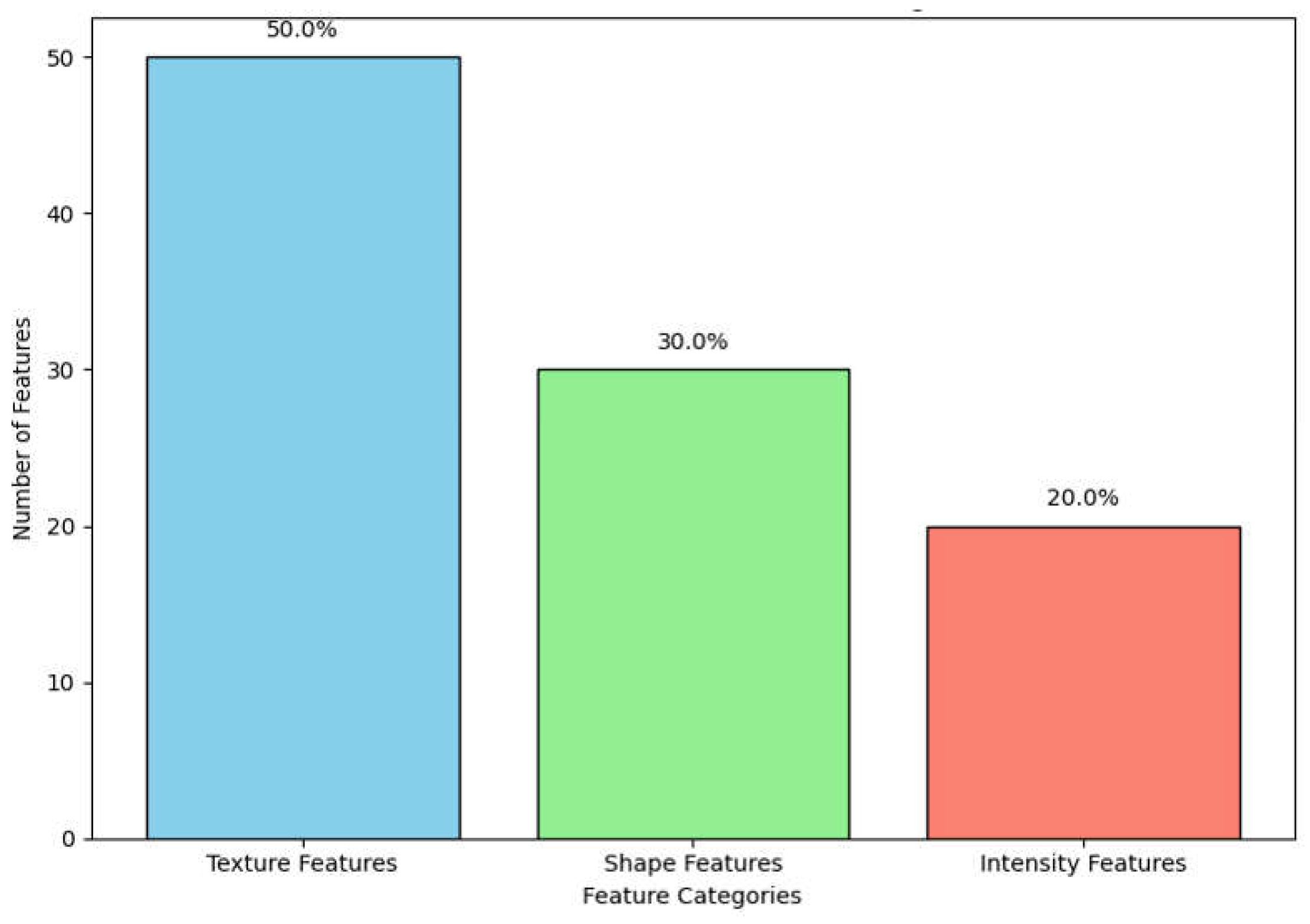

9]. In sum, completeness, following standardized protocols, flexibility, and open-source availability are the reasons why PyRadiomics was chosen. A total of 350 radiomic features will be extracted from each ROI (Region Of Interest) to process CT images in DICOM format. These features include first-order statistics, shape-based descriptors, and texture-based metrics. Features were selected based on how well they are able to represent some critical characteristics of the tumor, such as heterogeneity, complexity, and morphological structure. Carefully selected features ensured that the model had access to the most relevant data for the most accurate diagnosis of lung cancer [

10]. As shown in

Figure 2, texture features constitute the largest category within our dataset, followed by shape and intensity features. This distribution underscores the diverse information captured from DICOM images for a comprehensive tumor characterization.

2.2.1. First Order Statistics

First-order statistics describe the distribution of individual voxel intensities within the ROI and are hence utilized to summarize the intensity characteristics. These features convey the basic but highly fundamental understanding of the overall structure of the tumor and include:

Mean Intensity: The mean value of the voxels comprised within the ROI, reflecting to a great extent the average density of the tissue.

Skewness: Characterizes the asymmetry of the voxel intensity distribution and hence, the heterogeneity of the tumor.

Kurtosis: describing the property 'peakedness', in other words, whether a distribution of voxel intensities is bunched around or spread out from the mean.

Energy: This is the sum of the square of the voxel values, which may be related to the aggressiveness of the tumor or its metabolic activity.

These first-order features are simple but not worthless. They provide a view on the basic character of the tumor, especially from the early beginning of tumor development onward.

2.2.2. Shape-Based Features

Shape-based feature features are of immense importance in understanding the geometry of the tumor and thus provide knowledge of how a tumor grows and interacts with surrounding tissues. Lung cancer tumors have been found to be mostly irregularly shaped, which is sometimes not captured through traditional imaging assessments. Shape-based features included in the extraction study are:

Sphericity: A measure of how spherical (round) the tumor is, where values approaching 1 depict structures near perfectly spherical. Lower sphericity values indicate that highly aggressive and invasive tumors are more characteristic.

Compactness: Shows how much the shape of a tumor is spherical or elongated and can thus be an indication of its invasive power.

Surface Area to Volume Ratio: This measure compares the surface complexity of the tumor to its volume. The higher the ratio, the greater the chance for irregular growth patterns—often associated with malignancy.

Elongation: Measures the deviation in the tumor shape from a perfect sphere and may give clues of its infiltration into surrounding tissues.

Shape descriptors bear particular importance for late-stage tumors, as the growth patterns may lead to fundamental insights into the aggressiveness of the cancer and its metastasis potential. In light of this viewpoint, we make the assumption that shape-based features would become more significant as size increased due to structural deformations brought about by unchecked growth.

2.2.3. Texture-Based Features

These features are probably the most powerful descriptors of intratumoral heterogeneity, with tumor heterogeneity at both microscopic and macroscopic levels actually being one of the hallmark features of cancer. In fact, these provide a quantitative measurement of the variation in the intensities of voxels within a tumor that could unveil the underlying biological processes such as cell density, necrosis, and angiogenesis. The main features of texture extracted in this study included measures derived from:

GLCM: GLCM (Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix) features describe the frequency of pixel intensity pairs for a predefined spatial relationship. GLCM entropy may serve as an example and denotes the complexity of the variation in voxel intensities. The greater the values, the greater the heterogeneity, which is usually associated with malignancies. Other significant GLCM features include contrast, which describes the difference between high and low intensities, and correlation, which is the measure of linear dependencies between the intensity of voxels.

GLRLM: This matrix provides the length of consecutively sharing voxels with the same intensity value in a given direction. The related features to this are the GLRLM (Gray-Level Run Length Matrix) Short Run Emphasis, which manifests the presence of small homogeneous regions inside the tumor, while the GLRLM Long Run Emphasis gives information about the boundless homogeneous regions. These will be relevant for identifying the fibrotic regions or regions bearing necrosis inside the tumor.

Grayscale Level Size Zone Matrix: GLSZM is very similar to the GLRLM in that it quantifies regions of identical intensities; no directional information is taken into account, however. Important features are relying on this matrix: Zone Size Non-Uniformity and Large Zone Emphasis may be useful to detect the presence of large homogeneous areas, generally indicative of late disease stages.

Wavelet features: Refer to those signal features extracted through the application of wavelet filters on images for capturing texture at multiple resolutions. This multi-scale analysis is critical in order to detect subtle patterns both at fine and coarse details, thus offering a more nuanced understanding of tumor heterogeneity.

These features provide a fine-grained detail from the internal structure of the tumor, well beyond what is directly observable from the raw imaging data. In the cases of early-stage tumors, we postulated that the texture features would turn out to be more informative since early malignancies often manifest as small regions of heterogeneous intensity, which can be potentially detectable by advanced metrics of texture [

11].

2.2.4. Multi-Scale and Multi-Dimensional Feature Extraction

One of the novelties of this work was the inclusion of multi-scale and multi-dimensional feature extraction strategies. This combination of features derived from different resolutions and dimensions gave us a more robust dataset representative of both global and local tumor characteristics. This will be a way to ensure that machine learning models have access to the most complete representation of the tumor phenotype, thus allowing the detection of subtle yet clinically significant differences between malignant and benign regions.

2.2.5. Innovative Aspects of Feature Extraction

Manual and Semi-Automated Segmentation: The tumor ROIs were segmented using a great deal of care by manual delineation of expert radiologists combined with semi-automated algorithms to achieve the best precision together with reducing observer variability.

Standardization and Reproducibility: All extraction was carried out by strictly adhering to guidelines provided by the IBSI, with the aim of having all features reproducible across different imaging systems and acquisition protocols.

High-Throughput Feature Extraction: PyRadiomics thus enables the extraction of hundreds of features in one image effectively. High-throughput feature extraction in imaging data is of high importance to machine learning applications, especially in cases where the volume of data is immense.

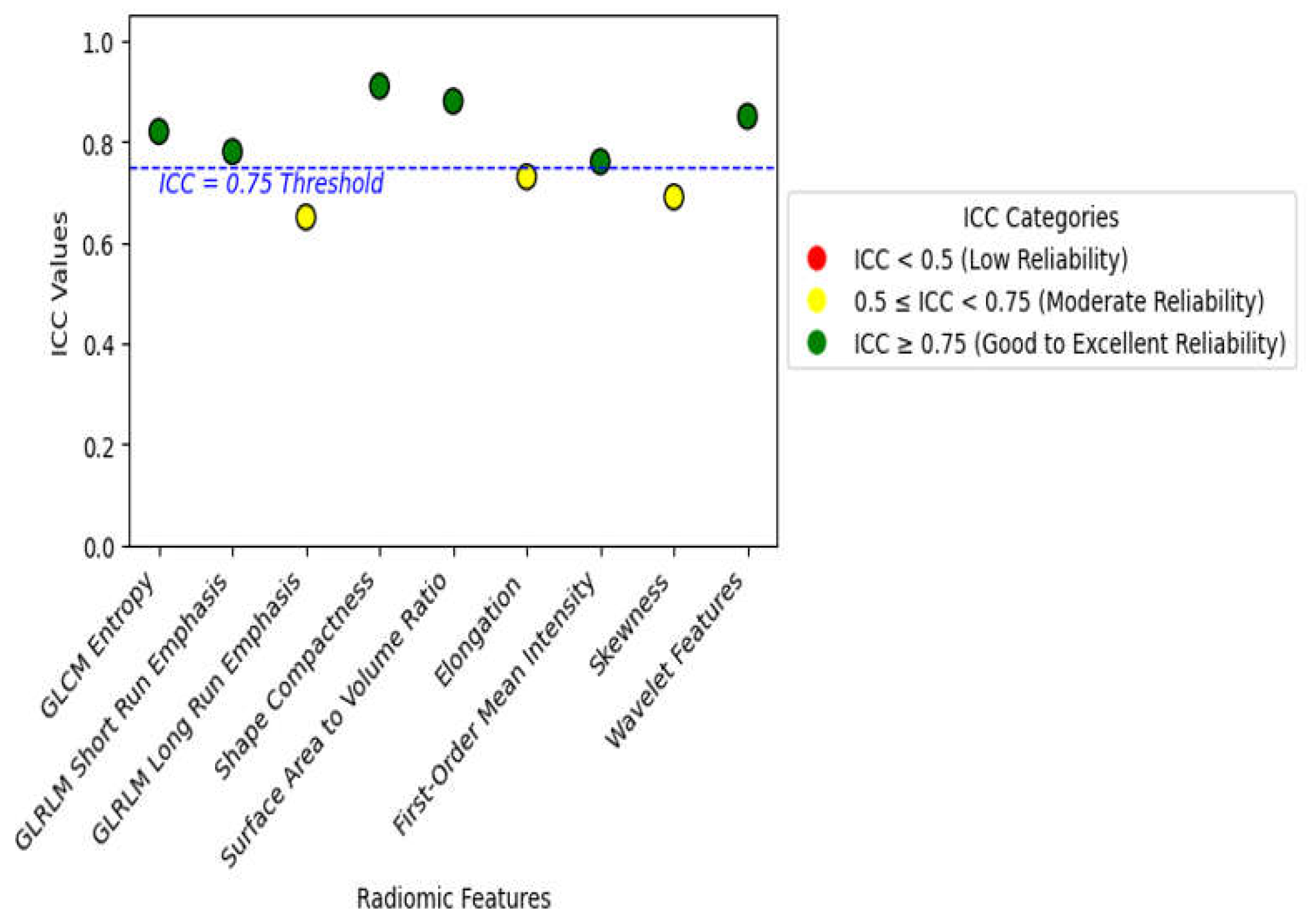

Finding the Best and Most Useful Features: Out of the 350 features that were collected, tests using forward stepwise correlation analysis and tests for test-retest variability were used to get rid of features that were duplicated or not relevant. We were able to minimize overfitting without reducing model accuracy by focusing the analysis on the most stable and informative features.

2.4. Machine Learning Model Development

An accurate machine learning model is the heart of radiomics-based cancer diagnosis, which allows conversion from high-dimensional feature space into clinically useful prediction. We focused on building a model to differentiate between malignant and benign tumors with the aid of features extracted from CT DICOM images (as described in

Section 2.2), which have been available for quite some time now. This could help us to extract the abstract heterogeneity of lung tumors through features derived from imaging, which were also very important in early detection and diagnosis.

2.4.1. Model Architecture and Choice

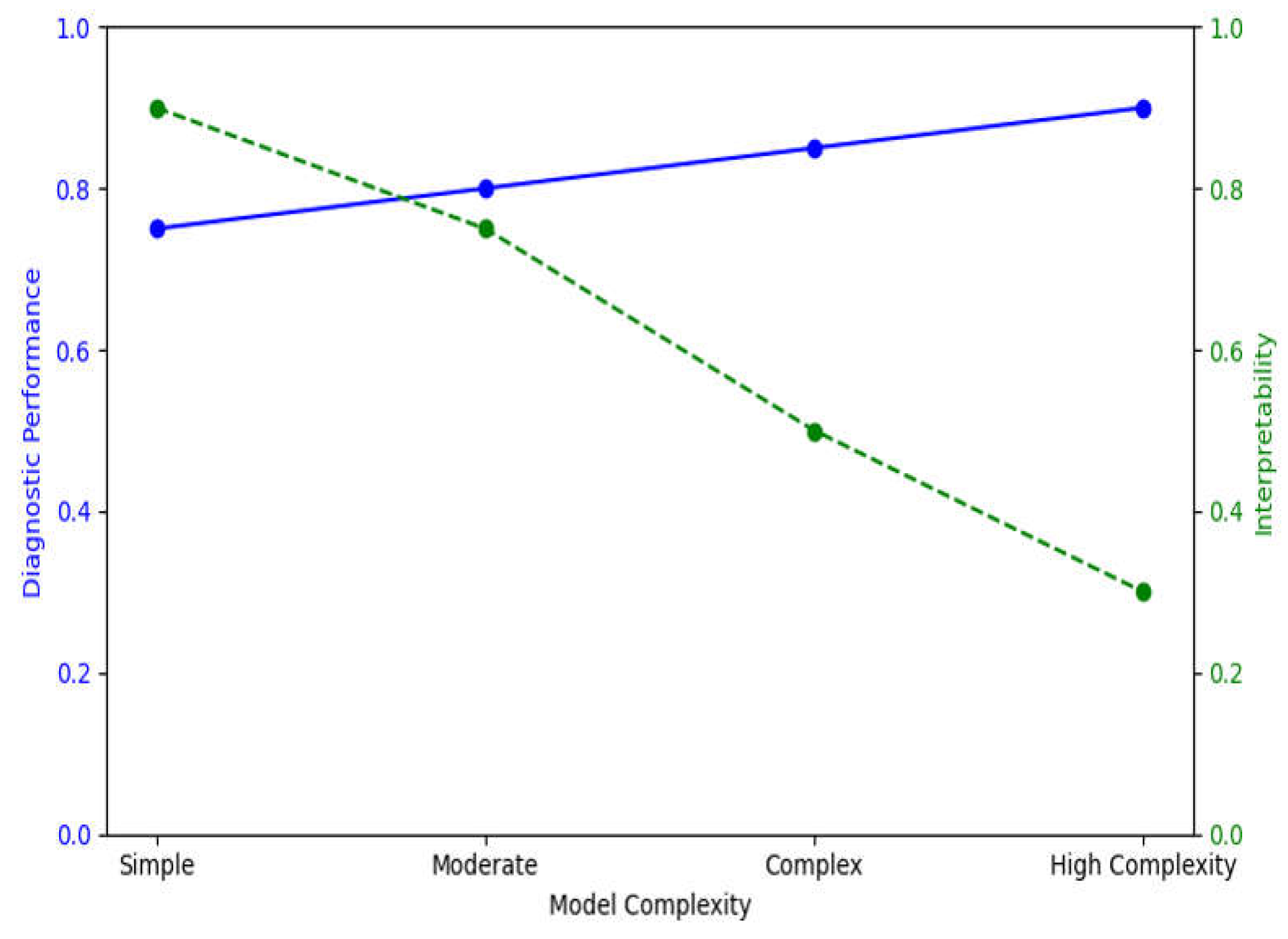

In this study, two main machine learning models were developed: a Convolution Neural Network (CNN) using the architecture of DenseNet-201 and an XGBoost algorithm. The chosen models thus had to cope well with the medical imaging data and radiomic feature complexity, providing a compromise between predictive power and model interpretability to allow for a hybrid diagnostic approach [

19].

• DenseNet-201 (CNN Model): DenseNet-201 is a popular CNN architecture that effectively performs image feature extraction through dense connections between layers. This dense connectivity mitigates the vanishing gradient problem by helping in reusing features across layers to learn more complex imaging tasks like detecting cancer. To this end, in our study we trained the DenseNet model separately on both raw CT images and feature maps to enable the network to learn from spatial patterns (raw images) as well as quantitative tumor characteristics (radiomics-driven features) [

20].

Although CNNs are often used on pixel-based data, we incorporated extracted features as extra input channels for the DenseNet model. That meant the CNN got to use high-level quantitative descriptors—things like shape, texture, and intensity histograms that helped it make its later decisions in addition to all of the raw image data. Here, we present a multi-modal input design to improve the model's diagnostic accuracy by integrating pixel-based and feature-based analysis.

• XGBoost (Gradient-Boosted Decision Tree Model): XGBoost is a powerful machine learning algorithm that is known to perform well on tabular data and has become very popular in the world of Kaggle competitions, where it generally reaches SOTA (State-Of-The-Art) scores. Because of its feature importance ranking and model interpretability, CNNs are not very good at being mean for image data. Training the XGBoost model on extracted features allowed us to test the importance that individual features hold in diagnostic tasks and thus infer about biological interpretability [

21]. The model was then trained on the entire set of extracted features, and feature importance was evaluated using SHAP values and permutation importance to rank these race predictors (explained in

Section 2.3).

2.4.2. Training Process and Cross-Validation

Accordingly, both models have been developed by using a five-fold cross-validation strategy in order to make sure that the results were generalizable and not overly influenced by the training data. Cross-validation, which is an essential step in ensuring that overfitting does not significantly reduce model performance on unseen data, is particularly important in medical imaging studies, as representative cases are limited.

1. Five-fold Cross-Validation: The dataset was divided into five equal sized subsets, and in each fold of the cross-validation, one subset played the role of a validation set while the other four subsets played the role of training sets. This was repeated five times in such a way that each subset once acted as the validation set. Averaging over five folds provides a robust estimate of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC-ROC for model performance.

2. Data Augmentation: For the training of the CNN to enhance generalization, the data augmentation techniques were used on the CT images. Then, several augmentation techniques—like random rotations, flipping, cropping, and scaling—were used to introduce patient positioning and variability in scanner settings, which will increase distortions and the diversity of the training.

3. Hyperparameter Tuning: These activities also involve the tuning of learning rate, batch size, and dropout rate by a grid search strategy. The early stopping in this CNN model stops the training when it observes that there is no more improvement in validation loss within five successive epochs to avoid overfitting and saving computational resources. Similarly, XGBoost hyperparameters, such as but not limited to those involving the maximum depth of trees, learning rate, and regularization parameters, have been tuned in a manner that predictive performance is maximized at the possible cost of overfitting.

2.4.3. Model Optimization and Loss Functions

Thanks to the combined loss functions, comprised of both segmentation and classification, we managed to maximize its performance. Specifically, the dice loss function has been used to address segmentation accuracy for tumor regions, while a binary cross-entropy has been utilized for the classification task with regard to malignant/benign nature determination in tumors. Dice loss is a largely used metric in medical image segmentation and calculates the overlap between the predicted and actual tumor masks. This metric came in handy, especially for the segmentation part of the CNN in delineating the tumor boundary accurately. The model improves the Dice coefficient, acting to better define the tumor region. To classify, the binary cross-entropy loss function penalizes the network for each wrong prediction made, thereby allowing the model to be directed toward a more correct classification. The use of the network with this loss function has further allowed it to learn just how to label correctly and effectively both cancerous and non-cancerous regions from the raw imagery data and the radiomic feature maps.

2.4.4. Performance Metrics

• Accuracy: It refers to the measure of the portion of properly classified images, thus giving the general performance of the model.

• Sensitivity (recall): It is the capability of the model to correctly identify malignant cases. High sensitivity is rather important in cancer diagnosis because it will reduce false negatives.

• Specificity: The percentage of healthy cases correct that this model should identify in order to avoid the misclassification of a benign case as malignant.

• AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): a metric that will provide the model performance for distinguishing malignant from benign cases across all possible classification thresholds. The high value of AUC-ROC means it would be unproblematic for this classification model to make good distinctions between the classes, even if there is a class imbalance in this dataset.

2.5. Feature Importance and Interpretability

Similar to any other area of medical imaging and machine learning based on radiomics, interpretability is just as important as predictive accuracy. If models are to be clinically actionable, then clinicians must understand the rationale behind each prediction. Then again, the contribution of each feature that has emerged with a view not only to identify but also interpret the model's prediction has been our focus in the present study. For this work, SHAP was selected because it has capabilities for both the explanation of individual predictions, a local interpretability, and the aggregation of the feature contributions across all the predictions—or global interpretability[

22].

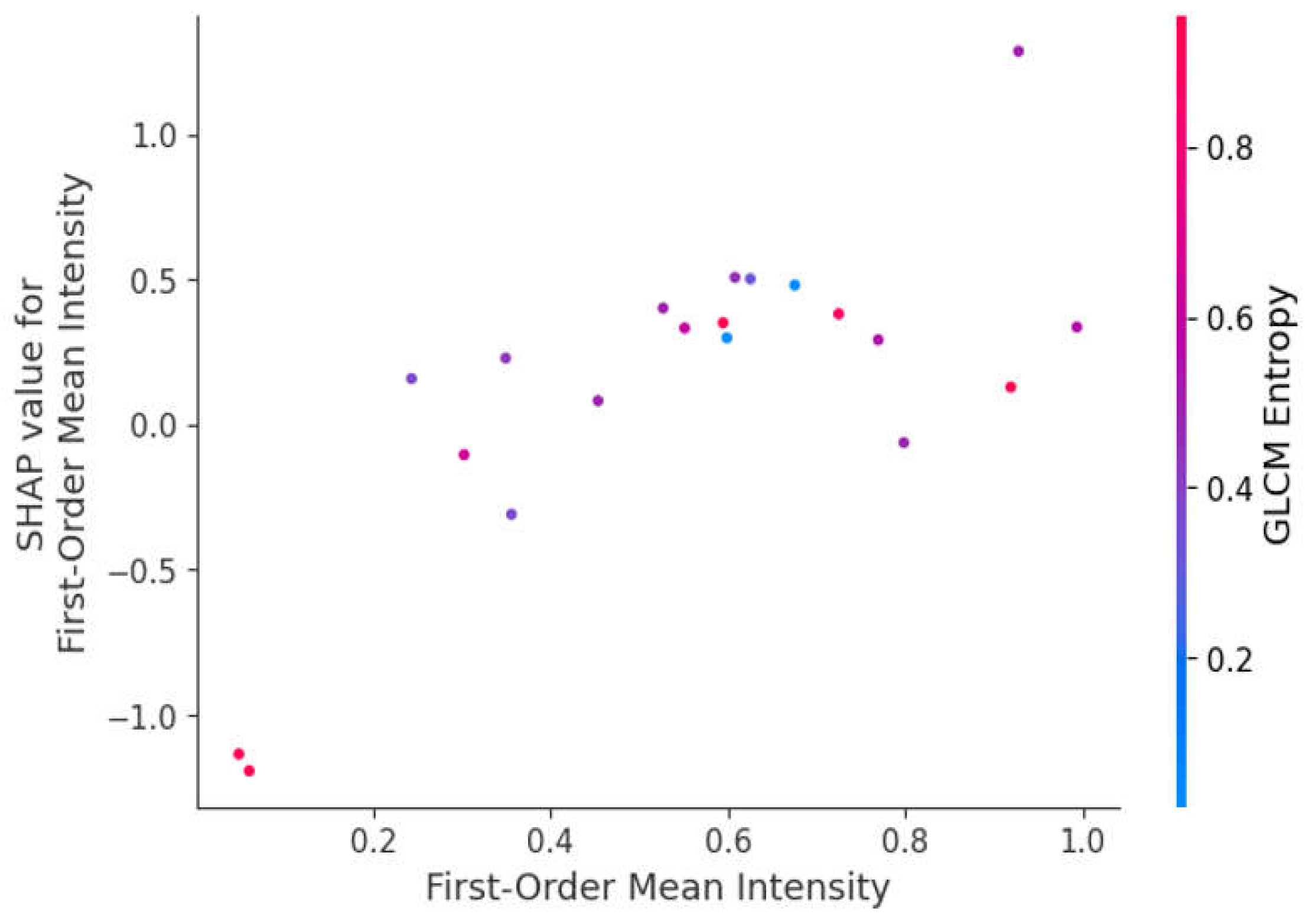

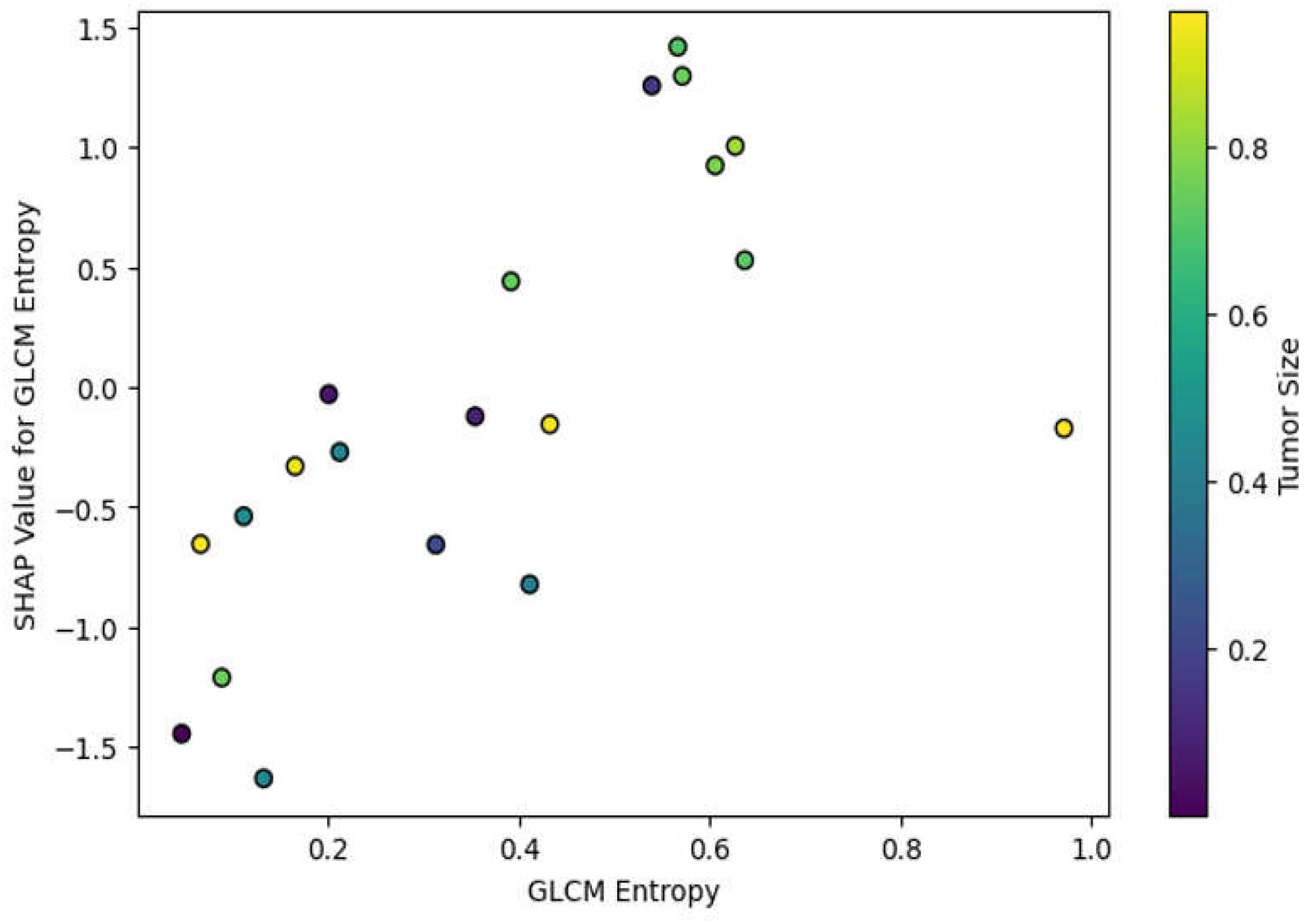

• Global SHAP Analysis: We averaged the SHAP values of every feature on the dataset and ranked the features by their general importance. Indeed, for every test we ran in this work, the features that ranked in the top places included GLCM Entropy and GLRLM Run Length Non-Uniformity; thus, our intuition about tumor heterogeneity being one of the key factors in malignant/benign tumor classification was legitimate.

• Local SHAP Analysis: SHAP also allowed us to drill into the contribution of features on a case-by-case basis. For example, in the specific cases of early-stage lung cancer, features related to first-order skewness, which reflects the asymmetry of voxel intensity distribution, have a high SHAP value and hence are critical for the right classification of small irregular tumors. That is very important for local interpretability in clinical applications, as it would tell the radiologists which features drove the model's decision for each given patient.

One interesting aspect of this study was the comparison of feature importance rankings obtained from the DenseNet-201 CNN model, which utilized both raw image data and features, with those given by the XGBoost model, utilizing only features. In this way, one can grasp how the integration of pixel-based and feature-based data impacts every single feature's importance. The CNN model considered the features as new input channels, together with the raw CT images. In this way, the network learned the complex patterns of the raw data, taking into consideration the quantitative features describing shape compactness and texture homogeneity. Feature importance rankings provided by both SHAP and permutation tests showed that even when presented with raw image data, the texture features still dominated. This therefore further underlines that features capture clinically significant information that may not easily be inferred from raw pixel data alone.

XGBoost, on its part, shows feature importance directly. Given that this model is trained only on radiomic features, GLCM Entropy and GLRLM Long Run Emphasis are the two most important features. This also goes as one would expect from the two metrics, which are really sensitive in bringing out malignant changes in tumor structure. Using only the radiomic data, XGBoost is more focused on how each feature contributes toward its final prediction. By comparing the results of both models, we were also able to confirm that the most important features were indeed the robust features, such as GLCM Entropy and GLRLM Non-Uniformity, across different learning paradigms.

One of the main goals with this study was to make sure that the machine learning model was interpretable and clinically actionable, not just accurate. SHAP values described why the model had made its prediction for a given patient, which is so crucial for the adoption of AI (Artificial Intelligence) models in healthcare. Besides, the clinical interpretability of the model was enriched by focusing on features with frank biological significance: As illustrated in

Figure 4, SHAP values highlight the global impact of selected radiomic features on model predictions, with GLCM Entropy and Shape Compactness emerging as key drivers of classification accuracy. Each point represents a SHAP value for a particular feature and sample, with color indicating feature value (red for high and blue for low).

2.6. Tumor-Specific Features Relevance

These features characterize tumors based on a wide range of aspects, which include shape, texture, and intensity; however, the importance of most of these features’ changes with changes in factors related to tumor size, stage, and location. In this work, our goal was to explore how much the importance of single features would change across different tumor phenotypes for insights into how heterogeneity impacts diagnostic accuracy. We explored the dynamic nature of these features by stratifying the tumors based on size and stage. Moreover, we accentuated the personalized diagnostic potential of radiomics in lung cancer. Tumor size represents an important attribute that modulates the relevance of radiomic features. Larger tumors usually show more geometrically complex and irregular shapes, whereas smaller tumors may only show subtle variations with respect to texture-based features. In this work, small-sized tumors were expected to rely more heavily on texture-based features due to the accentuation of intratumoral heterogeneity, while shape-based features were hypothesized to become more influential as the tumor increases in size and undertakes greater morphological distortion. To test this hypothesis, we stratified the tumors into three size categories based on the TNM ( Tumor-Nodes-Metastasis) system [

23]:

1. Small Tumors (< 2 cm): earlier-stage tumors, which, due to their small size, are often very hard to detect because they do not cause much morphological disruption. For these cases, we expected that texture-based features would convey the most information since these features capture the subtle heterogeneity in the tumor that might not be obvious to the naked eye from the raw images. This was indeed the case, as all texture features ranked higher in importance for smaller tumors, in keeping with our hypothesis that early malignancies are more micro-heterogeneous.

2. Medium-Sized Tumors (2–4 cm): In tumors of intermediate size, it was expected that both the texture and shape-based features had a balanced contribution. For such tumors, shape elongation and GLCM correlation were important features, for they extracted information on the change in geometry of the tumor during growth and more structured texture patterns within the tumor mass. This underlines the dual importance of texture and shape features within this size category in a way to hint at the necessity of comprehensive feature sets that express both aspects of tumor growth.

3. Large Tumors (> 4 cm): We expected that with the larger size and more advanced development of tumors, shape-based features such as surface area to volume ratio and compactness would turn out to be the most informative measures in distinguishing between malignant and benign status.

Our results confirmed this intuition: indeed, the more a tumor grows, the more significant its shape features become for classification. This may be because aggressive growth leads to increasing structural abnormalities. These size-based analyses indicate that radiomic models need to be tuned for tumor characteristics. While texture-based features can provide more accurate diagnoses in smaller tumors, shape-based features may become more critical in larger ones.

Another critical determinant in feature relevance is the tumor stage. As far as lung cancer is concerned, low-invasion and low-heterogeneity primary stages refer to the early stages of this cancer, corresponding to either Stage I or II, while the advanced stages of that tumor are usually categorized as Stage III or IV, showing clear morphological and textural changes due to a high growth in its malignancy, as well as tissue necrosis and vascularization. Knowledge of how feature importance evolves with the acquisition of cancer stages could be useful during the model training process in view of cancer detection at various points of its course[

24].

1. Early-Stage Tumors (Stage I-II): The critical contribution of texture-based features became more pronounced in low-stage tumors, which present with more subtle imaging characteristics. For example, GLCM contrast and GLRLM long-run emphasis constituted the most informative features for early-stage tumors, underscoring the importance of capturing those fine-grained textural variations arising from early intratumoral heterogeneity. These findings hint that texture features may be used as an early sign of malignancy, therefore opening perspectives towards earlier and more accurate detection.

2. Late-Stage Tumors (Stage III-IV): While advancing to the more advanced stages, tumor shapes become increasingly irregular due to invasive growth patterns. In late-stage tumors, shape-based features such as elongation, surface irregularity, and sphericity were most important. These features captured the complex structural deformations occurring with invasion into adjacent tissues and more pronounced morphological characteristics of these tumors. More than that, the texture features related to necrosis and heterogeneity remained salient at these stages and were probably related to the increased inner complexity of the advanced tumor.

This could also indicate that tumor stage-tailored models might lead to even higher diagnostic superiority. More importantly, this suggests that texture-based features were more critical at early-stage tumors, whereas the shape-based ones are more informative for the advanced stage of tumors given their structural complexity.

Another factor is the tumor location within the lung. Central tumors, which are near the bronchi and mediastinum, tend to have different patterns of growth compared with those that develop in the peripheral tissues of the lung. In this study, we investigated if specific features may be informative for tumors in certain anatomical locations and helped refine diagnostic accuracy based on tumor site.

1. Central tumors: Tumors around the central bronchi and mediastinum may, for instance, have more complex relationships with vessels and airways. For them, shape-based features such as convexity and elongation had greater relevance since the feature set was biased toward distinguishing irregular growth patterns that result from confinement imposed by surrounding anatomical structures. Besides, GLCM correlation performed really well in detecting tumor heterogeneity of central lung tumors that may show complex interaction with the surrounding tissues and thus exhibit variant intensity patterns in CT images.

2. Peripheral Tumors: Tumors that originate in peripheral lung tissues, away from the bronchi and mediastinum, grow more freely in most cases and adopt more rounded or nodular shapes. In such cases, texture-based features were of higher importance, reflecting heterogeneity and an irregular internal texture of the tumor. Moreover, surface area to volume ratio played an important role in the detection of an irregular tumor shape since peripheral tumors are less confined by structure compared with central tumors.

One of the key novelties of this work was investigating how tumor size, stage, and location interact in order to influence the feature relevance. Doing the combined analysis allowed us to highlight the concrete patterns of feature importance variation for several tumor characteristics. For example:

• Small early-stage peripheral tumors: These are best described by features of texture—for example, GLCM entropy, which captured the subtle heterogeneity within the tumor. Shape features are less important for this subgroup since these tumors have not adopted those irregular morphologies typical of more advanced cancers.

• Large, Late-Stage, Central Tumors: On the contrary, these larger tumors, located near the central part of the lungs, were more characterized by shape-based features, such as surface irregularity and elongation, describing the invasive and irregular growth of the tumor in an advanced stage of cancer.

The interaction between size, stage, and location imposes further complexity on radiomic analysis and calls for models capable of flexible adaptation to various phenotypes of tumors.