1. Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ES cells) possess the unique ability of self-renewal and differentiation into various cell types, a characteristic termed pluripotency. The orchestration of pluripotency is governed by intricate networks of transcription factors, signaling pathways and epigenetic complexes [

1]. Notably, PML (Promyelocytic Leukemia protein) and its associated nuclear bodies (PML-NB) have emerged as essential regulators of these cellular processes. PML has been shown to safeguard the naive pluripotency state by promoting cell cycle progression and inhibiting the onset of primed pluripotency [

2], a role distinct from its well-known function as a tumor suppressor. The diversity of cellular processes regulated by PML-NBs is driven by variations in the client proteins associated with PML across different cell types or in response to specific stimuli. Intriguingly, PML bodies are reportedly involved in the regulation of numerous, often contrasting cellular processes, including transcription, apoptosis, genome stability, cell cycle control, senescence, stress response, oncogenesis and stem cell pluripotency [

3,

4].

PML's ability to regulate transcription is quite complex and not completely explored. PML bodies can both activate and repress transcription by modulating the activity of coactivators or corepressors [

5]. Another mechanism involves the relocation of specific gene loci close to PML bodies for transcriptional activation [

6]. and the establishment of gene activation memory [

7]. Recently, a new mechanism was reported for PML bodies in the activation of a gene cluster in Y chromosome by prohibiting the access of Dnmt3a and DNA methylation [

8]. An alternative PML-mediated way to regulate gene expression and cell physiology is by interactions and/or posttranslational modifications (such as phosphorylation, acetylation and sumoylation) of a large group of proteins collectively named as PML–NB clients.

Although several studies have reported transcriptomic changes in embryonic stem cells following the ablation of PML [

2,

8,

9] no information exists regarding the proteomic landscape. To explore this area, we undertook here the analysis of the changes in ES cell proteome that are imposed by PML loss. Considering the critical role of post-translational modifications in protein function, we aimed to complement our proteomic studies with the examination of PML-dependent changes in sumoylation, an important modification that is particularly controlled by PML-NBs [

3]

PML protein functions are accomplished following its sumoylation-dependent assembly into PML NBs, that allows the subsequent recruitment of client proteins via association with their SUMO Interacting Motifs (SIM) [

10,

11]. Moreover, sumoylation of chromatin proteins was reported to play a significant role in the maintenance of cell identity by inhibiting cell state conversions between somatic and pluripotent stem cells [

12]. Despite the recognized importance of PML in stem cell biology, the role and number of proteins sumoylated in a PML–dependent way is not completely explored.

In this study, we report the comprehensive characterization of the PML-dependent proteome and SUMOylome in embryonic stem (ES) cells. By integrating these data with biochemical analyses, we sought to identify novel protein factors and modifications supported by PML within the context of self-renewing pluripotent stem cells. Our results demonstrate that PML is positively regulating the abundance of proteins required for self-renewal whereas is exerts a negative effect on proteins that are related with translation and proteasome. PML is necessary for the sumoylation of many critical cellular factors that are required for pluripotency maintenance, chromatin organization and cell cycle progression. Among them, we singled out SALL1 and CDCA8, which play crucial roles in maintaining the undifferentiated state by promoting the Wnt pathway and facilitating cell cycle progression, respectively. These newly identified PML-dependent sumoylation targets broaden our understanding of the diverse molecular mechanisms by which PML regulates ES cell identity.

2. Results

2.1. PML Regulates the Expression of Proteins Involved in ES Cell Self-Renewal, Translation and Proteasome Activities

We have shown earlier that PML is essential for the maintenance of ESC naïve pluripotency by regulating the transcription of a large number of genes [

2]. The changes in the ES cell proteome caused by the absence of PML are not known. For this, we sought to analyze the proteome differences between PML Knock Down (KD) and Wild Type (WT) CGR8 cells.

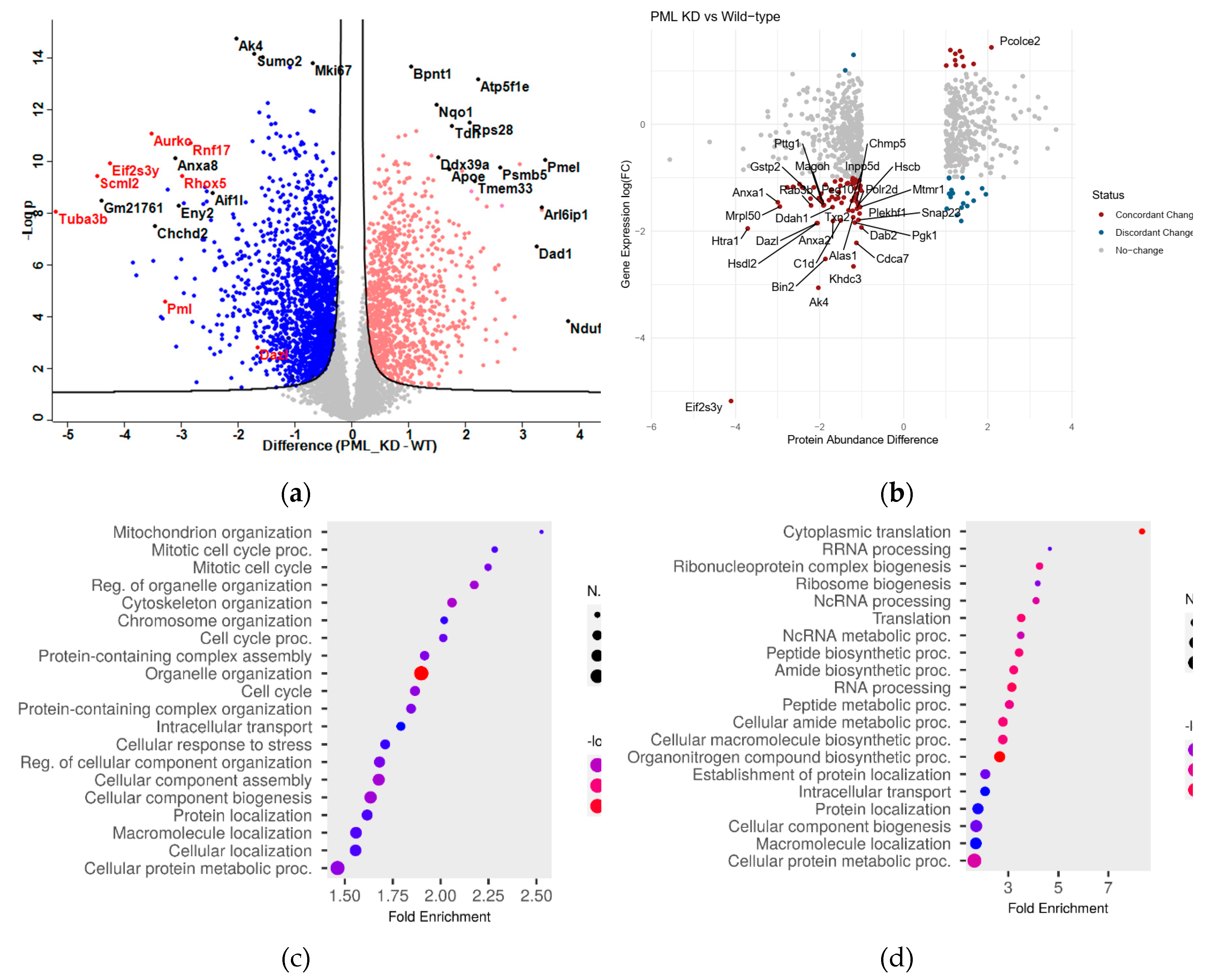

As shown in

Table S1 a total of 6420 proteins were identified. In the absence of PML (PML KD), the number of down-regulated proteins was greater than that of the up-regulated ones, 1468 vs 929 at the threshold of absolute log2-difference >0.5 and p-values <0.05. (

Table S1). In

Figure 1a proteins that are down (blue) or up (red) regulated in the absence of PML (PML KD vs WT) are depicted. Proteins that were repressed in the absence of PML included Dazl, Scml2, Tuba3b, Eif2s3y, Rnf17, Rhox5, Aurkc (

Figure 1a, marked in red along with PML) which are related to the regulation of spermatogenesis [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The link between PML and spermatogenesis needs further investigation. In the category of upregulated proteins, notable examples included proteasome (Psmb5) and mitochondrial (Atp5f1e, Ndufa1) proteins.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the biological processes regulated by PML we compared the PML dependent proteome with our previously published transcriptomic data [

2]. We observed an overall bias for down-regulation at both the RNA and protein levels when comparing PML KD with the WT (

Figure S1a), suggestive of a general trend of congruence between transcription and translation levels.

The overall positive correlation of RNA and peptide abundance changes was evident among a core of 96 genes, selected with strict criteria for both differential RNA and protein levels (|log2 difference|>1 and p<0.05) (

Figure 1b). Out of those, we identified 77 highly significant genes with concordant changes (same direction of expression/abundance change in RNA/protein level), compared to 19 with discordant change (different direction of expression/abundance change (

Table S2). Concordantly, suppressed genes (i.e.decreased at both RNA and protein levels) in the absence of PML were functionally enriched for association with RNA PolII transcription (

Figure S1b), highlighting the role of PML in gene transcription.

A functional analysis of the PML dependent proteome was performed focusing on biological processes, employing ShinyGO 0.80

http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/. As shown in

Figure 1c, mitotic cell cycle process along with organelle and chromatin organization are the top down-regulated pathways in PML KD cells in agreement with a growth promoting role of PML in this cell context [

2]. Top up regulated molecular pathways include translation, ribonucleoprotein and ribosome biogenesis (

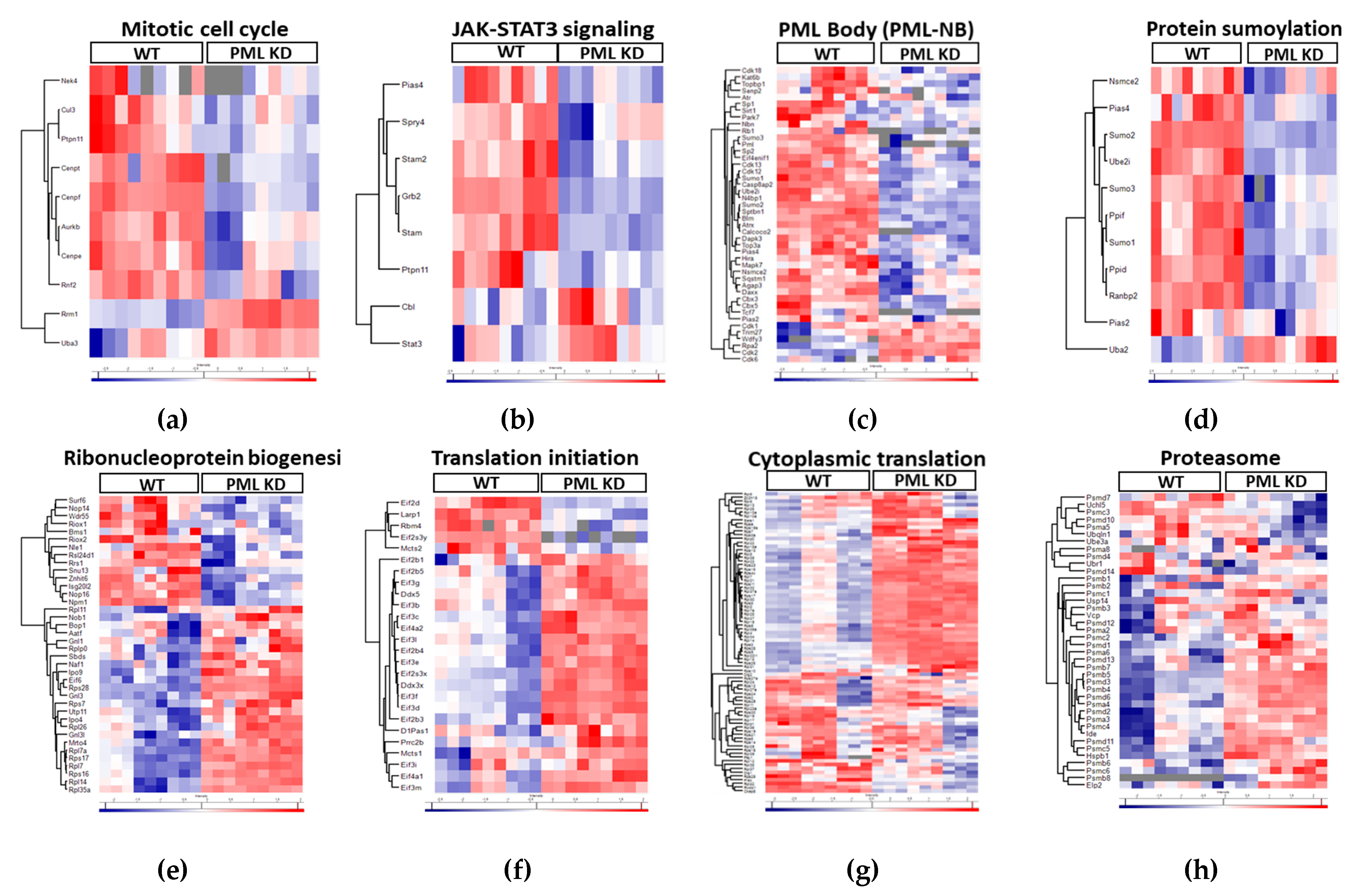

Figure 1d). A detailed hierarchical analysis comparing relative levels of proteins related to mitotic cell cycle and the JAK/STAT pathway, show strong suppression in PML KD cells (

Figure 2a,b) in line with the described role of PML as cell cycle progression factor and STAT3 activator in ES cells [

2]. Remarkably, a large group of known PML body residents are positively regulated by PML (

Figure 2c). Moreover, further functional analysis of the ES proteome, revealed a group of sumoylation-process related proteins (

Figure 2d) to be suppressed in PML KD cells in agreement with the importance of PML Nuclear Bodies for sumoylation [

6]. In the group of up-regulated proteins we observed an enrichment of functions related to ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis, translation initiation, cytoplasmic translation and proteasome (

Figure 2e, 2f, 2g, 2h respectively). These data correlate with the global translational rate and ribosomal biogenesis increase which is observed when cells initiate differentiation [

17]. The upregulation of proteasome subunit proteins may indicate a need to balance the increased translation rates, thereby supporting cellular homeostasis.

Collectively PML loss causes a decrease in the expression levels of proteins associated with embryonic stem cell self-renewal including the mitotic cell cycle and JAK-STAT3 processes, PML nuclear body (PML-NB) assembly and sumoylation. Conversely, it leads to an increase in the expression levels of proteins involved in cellular translation, ribosome biogenesis and proteasome function.

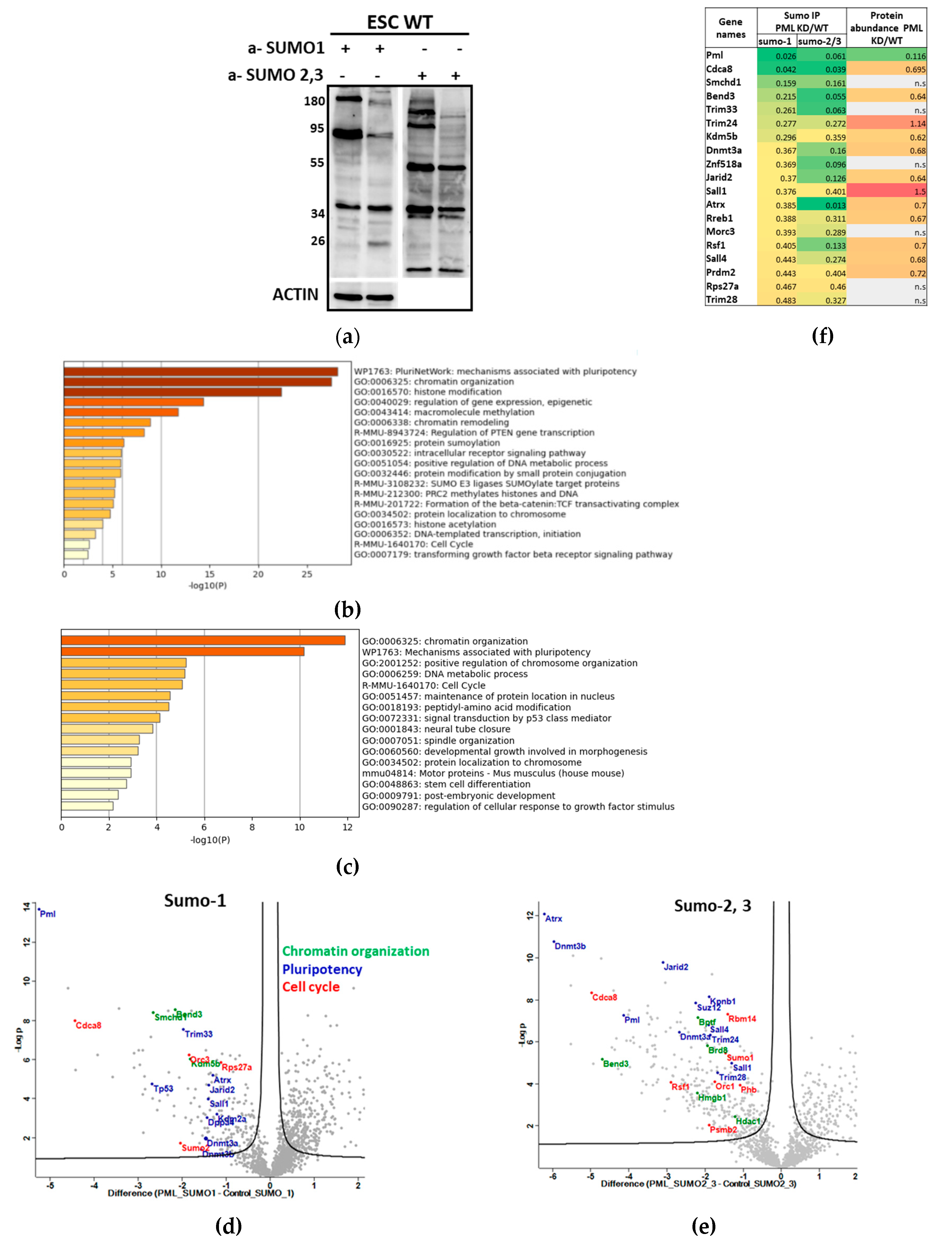

2.2. PML Promotes the Sumoylation of Key Regulators Involved in ES Cell Pluripotency

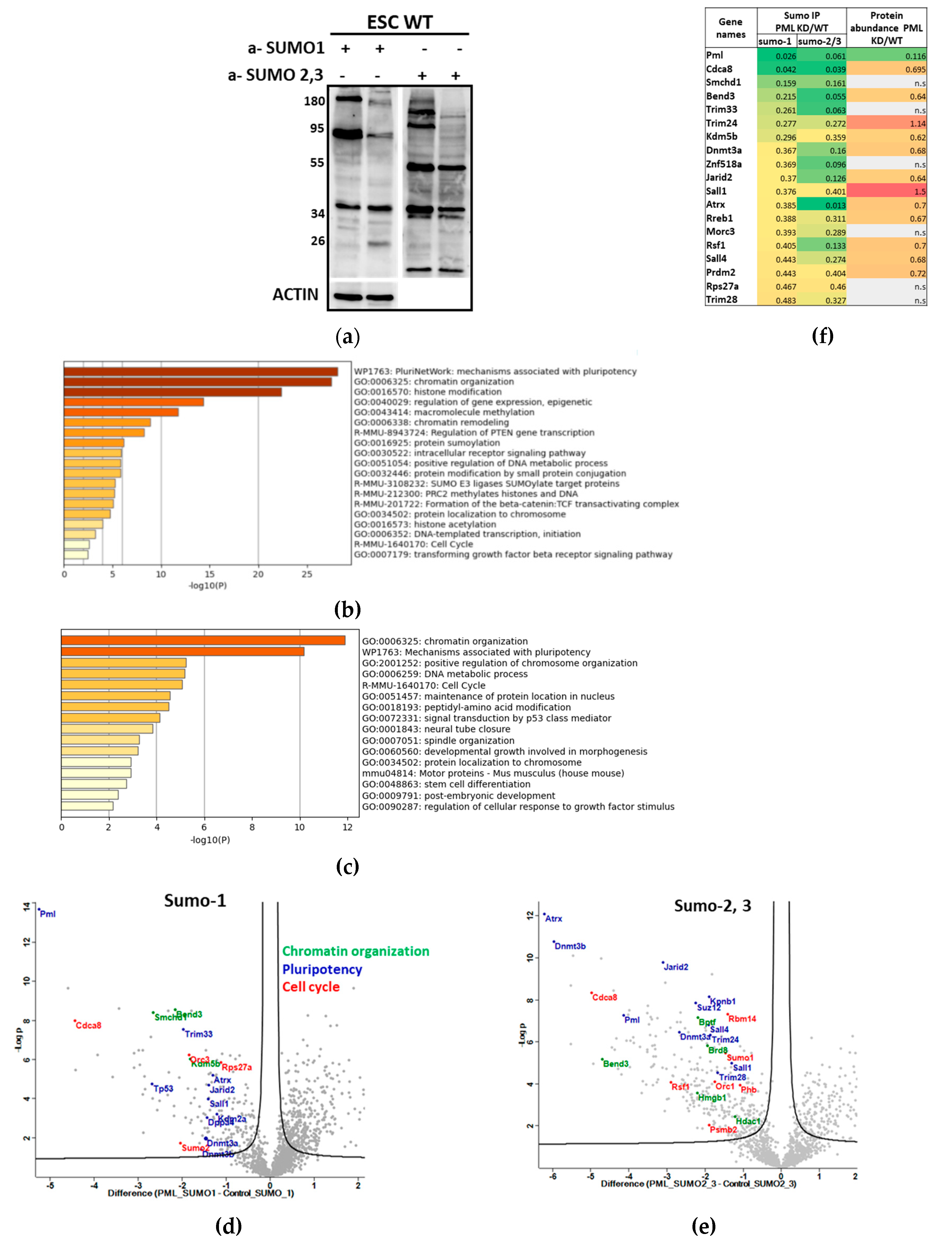

To confirm our earlier finding that silencing PML results in the downregulation of sumoylation-process related proteins (

Figure 2d), we investigated whether this silencing also influences global sumoylation levels. Using protein extracts from PML KD ES cells we detected reduced amounts of SUMO modified proteins by either SUMO1 or SUMO2/3 compared to the WT cells (

Figure 3a), showing the importance of PML for this modification.

Due to our previous observation and because sumoylation is closely associated with the assembly and functions of PML nuclear bodies [

6], we chose to identify changes of the SUMOylome between control and PML knockdown (KD) cells. Sumoylated proteins from the two cell lines were immunoprecipitated using beads coupled with SUMO-1, SUMO-2/3 or IgG (control). Eluted proteins were subjected to proteomic analysis using LC-MS/MS. A complete list of SUMO-1 or SUMO-2, 3 target proteins in both cell types is shown in

Table S3. Applying a 2fold cutoff for PML KD against the WT difference we detected 155 SUMO-1 and 166 SUMO 2,3 target proteins (

Table S4).

We next performed a functional enrichment analysis of the PML-dependent SUMOylome using Metascape [

18]. Down-sumoylated proteins for both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 in PML KD cells included genes primarily related with Pluripotency, Chromatin Organization/Histone Modifications and cell cycle (

Figure 3b,c). Proteins showing strong sumoylation variability in the absence of PML are indicated in

Figure 3d and

Figure 3e. While down-sumoylated proteins were enriched in the processes mentioned above those found to be over-sumoylated in PML KD cells were related with mRNA processing mechanisms and diverse functional groups at lower significance levels (

Figure S2a).

In order to test whether sumoylated proteins are associated with PML-NB we compared the groups of SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 target proteins (

Table S4) with a recently reported list of PML interacting proteins in mouse ES cells using Turbo-ID [

19] (Dataset EV2). We observed that the majority of proteins that are strongly sumoylated in PML expressing cells are PML-NB clients (

Figure S2b, 57% of Sumo-1 and 67% of Sumo-2,3 targets) indicating that these proteins are sumoylated upon their association with PML-NB.

In

Figure 3f we display proteins that were under-sumoylated by both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 in the absence of PML, indicating sumoylation and protein abundance difference of the PML KD against the WT. The majority of them are proteins related with pluripotency and chromatin organization. We next validated the changes in SUMOylation status in WT CGR8 as opposed to the PML KD cells using SUMO-immunoprecipitation combined with immunoblotting (

Figure S3a,b). We confirmed the reduction of sumoylation in PML KD compared to WT cells of selected proteins from

Figure 3f, ATRX, SALL1, SALL4, TRIM24 and CDCA8 (Borealin). The reduction of sumoylation was not due to changes in their corresponding protein expression levels (

Figure S3a and S3b for SUMO1 and SUMO-2/3, respectively). Thus, as mentioned before and observed by a total comparison between the proteome and the SUMOylome (not shown), global protein abundance differences are not sufficient to explain the full extent of sumoylation divergence between control and PML KD cells.

In conclusion, the capacity of PML to enhance the self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem (ES) cells may be attributed to the sumoylation of important factors that are involved in these processes. Therefore, we decided to investigate mechanistically the effects of sumoylation on the functions of two distinct factors, SALL1 and CDCA8, which are functionally associated with pluripotency and cell cycle, respectively.

2.3. Sumoylation Increases the Stability and Wnt Pathway Potentiation Activity of SALL1

The Spalt Homology 1 (SALL1) protein is responsible for causing Townes–Brocks Syndrome (TBS) leading to a combination of anal, renal, limb and ear anomalies [

20] through molecular mechanisms that involve its function as a transcription factor and its role in regulating primary cilia functions [

21]. SALL1, a member of the pluripotency network of ES cells [

20] was reported to promote ESC pluripotency [

21] and contribute to reprogramming into pluripotency [

22].

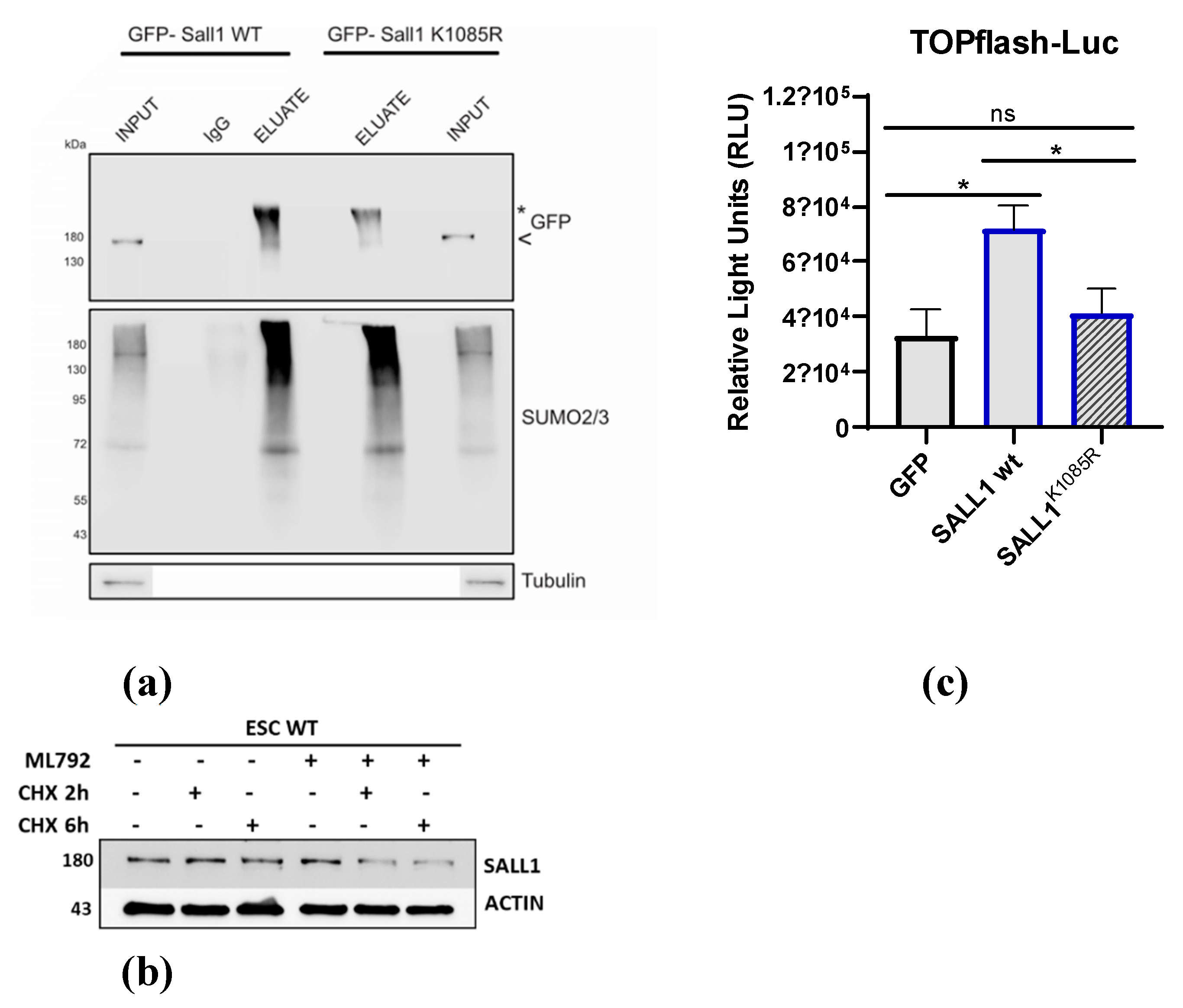

In vitro sumoylation of human SALL1 by UBE2I at lysine 1086 has been reported [

22] and confirmed by later SUMO proteomic analyzes [

23] but the functional consequences of this modification in ES cells were not studied. To examine the role of SALL1 sumoylation, we mutated lysine 1085 that was reported to be the major sumoylation site in ES cells [

24]to Arginine. We confirmed that sumoylation is severely reduced in this mutant (more than 50%) compared to the WT (

Figure 4a). We next employed the SAE inhibitor ML-792 in combination with cyclohexamide to test if sumoylation regulates the stability of SALL1.

Figure 4b shows that inhibition of sumoylation reduces the protein’s half-life. SALL11 is a well characterized activator of the Wnt pathway . [

25] which is essential for maintaining the pluripotency of embryonic stem (ES) cells. Thus, we next tested the consequence of SALL11 sumoylation on the activation of Wnt pathway.We used the TOPflash luciferase reporter that measures TCF/LEF transcriptional activity in the Wnt signaling pathway. As shown in

Figure 4c, co-transfection with plasmids expressing SALL1, showed that SALL1 WT potentiated luciferase activity to much higher level relative to the K1085R mutant protein. Thus, sumoylation is a molecular mechanism that regulates both the turnover and the transcriptional activity of SALL1 in ES cells.

2.4. Sumoylation Regulates the Stability and the Cell Cycle Progression Activity of CDCA8

The cell division regulator and component of the chromosomal passenger complex CDCA8/Borealin is strongly expressed in undifferentiated ES cells and plays essential role in the mouse embryonic development [

26,

27].CDCA8 is one of the most important PML-dependent sumoylation targets (

Figure 3c,d) and a PML interacting protein in ES cells [

19]. Therefore, we hypothesized that CDCA8 sumoylation [

28] could play a role in influencing the cell cycle progression activity of PML in (ES) cells.

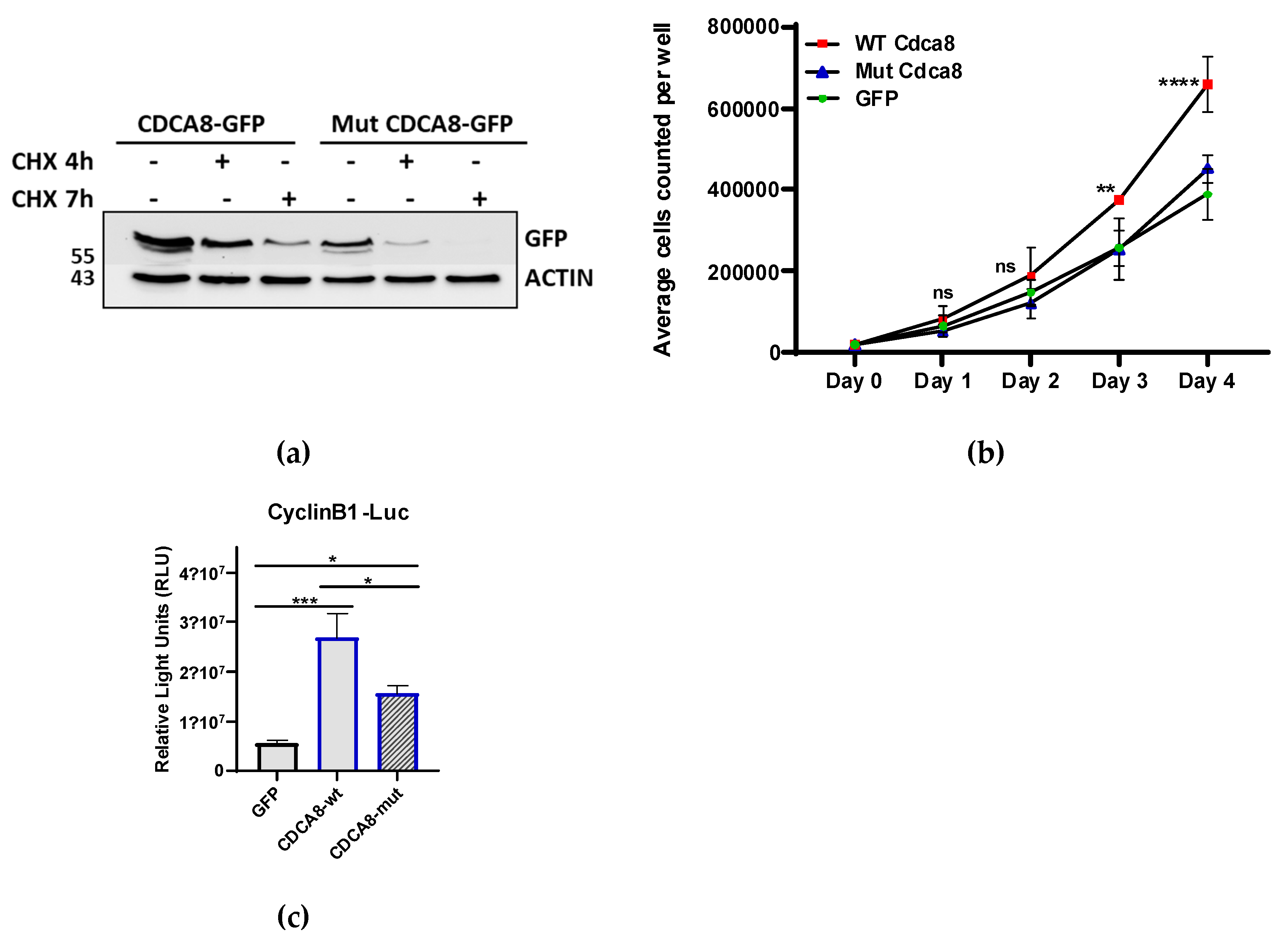

We mutated all 5 lysine residues (63;88;109;124;192) that were reported to be sumoylated in mouse ES cells[

24] and expressed both WT and sumoylation-mutant (MUT) proteins as GFP fusions creating stable cell lines. These cell lines were than treated with cycloheximide in order to determine the respective turnover rates of the WT and the sumoylation-mutant proteins. Immunodetection revealed that sumoylation increases the stability of CDCA8 protein since mutant protein has a shorter half-life compared with the wild type (

Figure 5a). Considering the importance of CDCA8 for mitotic progression we measured growth curves for the above-mentioned cell lines. In analogy with its role in cancer [

29] overexpression of CDCA8 WT caused a higher cell proliferation rate compared with the control (GFP) whereas the sumoylation mutant had lost this ability (

Figure 5b). CDCA8 was reported to stimulate tumor development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) via potentiation of cell cycle progression factors such as cyclins, Ki 67 and PCNA[

29,

30]. To test whether sumoylation could be involved in this activity, we used a Cyclin B1 promoter luciferase reporter. As shown in

Figure 5c, the addition of the CDCA8 WT stimulates the activity of cyclin B promoter whereas the sumoylation mutant protein cannot. Thus, we conclude that sumoylation is important for the cell cycle progression regulation of CDCA8.

3. Discussion

PML nuclear bodies (PML-NB) are dynamic intranuclear hubs that regulate numerus cellular processes including transcription, apoptosis, stress response, cell cycle progression, antiviral responses, and genome stability [

3]. The biochemical mechanisms that mediate the effect of PML on these processes are not easy to dissect since they involve, in addition to different PML isoforms, divergent sets of client proteins dependent on the cell type and genetic background. Although the role of PML in oncogenesis is well clarified, the elucidation of PML functions in cell fate decisions is far from complete. The PML-dependent transcriptome in ES cells has been reported by our [

2] and other labs [

8,

9], however a proteomic or in depth post-translational modification analysis is still missing. Especially sumoylation has emerged as major player of orchestrating networks of proteins that determine cell fate [

12]. To bridge this gap, we have conducted an investigation of the proteomic and sumoylation changes in embryonic stem (ES) cells in the absence of PML.

Our proteomic analysis revealed that proteins that are suppressed in the absence of PML were related with mitotic nuclear division, mitotic cell cycle and JAK/STAT signaling, pathways that we have previously shown to be stimulated by PML in naïve pluripotent stem cells [

2]. Comparing our proteomic with previous transcriptomic data revealed a positive correlation that affects mainly the genes that are down regulated at both the RNA and protein level. Among these genes we noticed the occurrence of those related with RNA PolI II transcription. Thus, PML behaves mostly as a gene activator in ES cells. Interestingly, PML-NB of embryonic stem cells were reported to localize close to gene loci with features of active transcription such as open chromatin structure, enrichment of active and depletion of repressive histone modification marks [

8]. Moreover, we observed that a group of proteins associated with PML-NB, including ATRX, HIRA, DAXX and SP1 [

6] were expressed in a PML dependent way, the majority of them being repressed in absence of PML. These data point to a hub role of PML-ΝΒ in the regulation of multiple client and non-client genes at the RNA and/or protein levels. Another group of proteins that were strongly repressed in the absence of PML were associated with spermatogenesis (

Figure 1a). This observation indicates a potential role for PML in spermatogenesis, warranting further investigation. In accordance with this hypothesis, PML was recognized among the central regulators for the upregulated genes during mouse spermatogonial stem cell commitment during development [

31].

Proteins that were upregulated in PML knockdown (KD) cells were associated with ribosome assembly, translation and proteasome. An increase in translation rates has been linked to the initiation of embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation [

17]. Our previous research demonstrated that the ablation of PML facilitates the transition of ES cells from a naïve state to an epiblast pluripotency state [

2]. Therefore, the upregulation of proteins related with translation and proteasome may represent a compensatory mechanism aimed at sustaining cellular growth and protein synthesis as cells transition out of the undifferentiated state in the absence of PML. Together these results suggest that PML mediated regulation of protein synthesis may contribute to the maintenance of the stemness.

Repression of a group of proteins related to sumoylation in PML KD cells, led us to further study the PML dependent SUMOylome. By applying an unbiased SUMO-IP approach we were able to identify 155 SUMO-1 and 166 SUMO-2,3 proteins that show significant changes in their modification levels in presence of PML (

Table S4). In a similar study employing His/SUMO-2 over-expression strategy, the authors identified 77 PML-dependent SUMO-2,3 target proteins. They reported that sumoylation of KAP1 and DPPA2 proteins impedes ES cell transition to a 2C state [

9]. Comparing their list with our data, we found 18 common with our SUMO-2, 3 proteins and also 7 common with our SUMO-1 list. We consider that our unbiased approach allowed a higher number of SUMO-2, 3 target proteins.

Functional enrichment analysis of the PML dependent SUMOylome revealed that PML promotes the modification by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 of proteins that are related with pluripotency, chromatin organization and cell cycle regulation. Therefore, sumoylation is another molecular mechanism employed by PML for the potentiation of stem cell pluripotency [

2] Interestingly, more than 50% of these proteins are PML interactors indicating that they probably become sumoylated following their association with PML-NB. Our data are in agreement with a previous publication showing that sumoylation of epigenetic and chromatin regulators maintains the pluripotent stem cell state by inhibiting differentiation [

24].

We report here that SALL1 and CDCA8 are two novel PML SUMO targets that promote the undifferentiated state and cell cycle progression respectively. SALL1 is involved in the regulation of stem cell pluripotency by inhibiting the expression of differentiation related genes and synergizing with NANOG for transcription activation [

32]. We show here that sumoylation of SALL1 protein increases its stability and potentiates the ability of SALL1 to activate the Wnt pathway [

25] that sustains the ES cell undifferentiated state [

33]. This function may be partly due to the binding and sequestration of the Wnt negative regulators TLE and DACH1 that were reported to interact with sumoylated SALL1 in a recent study using the SUMO-ID technology [

34]. Therefore, it is likely that SALL1 SUMOylation plays a role in the protein's capacity to inhibit the differentiation of embryonic stem cells [

32].

PML ablation in ES cells triggers a series of molecular events that promote the exit from naïve pluripotency and entry into the primed state. The latter is characterized by a cell cycle extension [

2]. CDCA8 is an essential regulator of mitosis and cell division [

35] that orchestrates proper chromosome segregation and cytokinesis [

36]. CDCA8 is reported to be a PML-NB client, specifically in ES cells but not in MEFs [

19]. Here we show that sumoylation not only stabilizes CDCA8 but also potentiates its function to promote cell proliferation. We suggest that the role of PML in regulating cell cycle progression in embryonic stem (ES) cells may be partly attributed to the sumoylation of CDCA8.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Antibodies

ML-792 (Selleckchem S8697) was used at 1-2 μM. Cycloheximide (CHX, Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 50-150μg/ml. Antibodies used were: anti-PML (1:1000, Millipore 05-718), anti-Sumo-1 (1:500, sc-5308), Sumo-2, 3 (1:500, sc-393144, Proteintech), anti-β actin (1.500, sc-69879), anti-GFP (1:500, sc-9996), Sox2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling #2748), Sall1(1:100, Affinity DF13458), Sall4 (1:500, sc-101147) Atrx (1:500, sc-55584), CDCA8/Borealin (1:500, sc-376635), anti-tubulin (1:1000, DHSB).

4.2. Plasmids, Mutagenesis

GFP/Sall1 construct was described earlier [

32] and used as template for the construction of the K1085R using side directed mutagenesis. Mouse Cdca8 cDNA (aa1 to 289) was produced by RT-PCR using the primers FOR: 5’-ATGGCTCCCAAGAAACGCAGC-3’, REV: 5’-TCATCGGCCCGTCCGTATGC-3’ and cloned first in pBS (SmaI) and finally in EGFP-C2 (EcoPI-BamH1). Mutant Cdca8 (K63R, K88R, K109R, K124R, K192R) cDNA was from Eurofins Genomics (Germany GmbH) and cloned in EGFP-C2 using the same restriction sites as for the WT. For the production of lentiviruses WT and MUT Cdca8 cDNAs were cloned in pLenti CMV GFP Puro (658-5) that was a gift from Eric Campeau & Paul Kaufman (Addgene plasmid # 17448 [

37]. Lentiviral supernatants were collected following co-transfection of pLenti plasmids with psPAX2 (Addgene#12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene#12259) gifts from Didier Trono [

37]. The TOPflash (TCF Reporter) was from Sigma-Aldrich (21-170). The Cyclin B1-luc reporter was constructed by inserting 484 bp of human cyclin B1 promoter (-367 to +117) in front of pGL3 basic vector (Promega). The primers used were: CyclB1-prom-for: TTGCTGCTACCGTAGAAATG and CyclB1-prom-rev: AGCCAAGGACCTACAACCAG

4.3. Cell Culture, Cell Transfections, Generation of Stable Cell Lines

Feeder-independent CGR8 murine ESCs were cultured on 0.2% gelatin in DMEM medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 15% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (GIBCO), 0.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Applichem), 2 mM L-glutamine (GIBCO), 1× MEM nonessential amino acids (GIBCO), and 500 U/ml LIF (ESGRO/Millipore). HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (GIBCO), 2mM GlutaMax (GIBCO) and 50μg/ml Gentamicin (GIBCO). Cell transfections were performed using the calcium phosphate and Lipofectamine™ 2000 (ThermoFisher). Stable cell line expressing Lenti/GFP CDCA8 WT and Lenti/GFP CDCA8 Mut were generated by selection with puromycin following 3 days following

4.4. Proteomic Data and Analysis

Protein extraction from the two cell lines (PML KD and WT) was performed using a lysis buffer consisting of 4% SDS, 0.1M DTT, 0.1M Tris pH 7.4. The samples were subjected to heating for 3 min at 99

oC, an incubation for 30 min in water bath-mediated sonication, followed by a centrifugation step for 15 min at 17000xg. Proteomic sample preparation was performed using the single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation Sp3 protocol [

38]. 20 ug of beads (1:1 mixture of hydrophilic and hydrophobic SeraMag carboxylate-modified beads, GE Life Sciences) were added to each sample in 50% ethanol. The protein extract was collected and processed using magnetic beads including an alkylation step in the dark for 15 min in 10 mg/ml iodoacetamide. The proteins were allowed to bind to the beads for 15 min followed by repeated steps of protein clean-up using a magnetic rack. The beads were washed two times with 80% ethanol and once with 100% acetonitrile (Fisher Chemical). The, captured on beads, proteins were digested overnight at 37

o C under vigorous shaking (1200 rpm, Eppendorf Thermomixer) with 0.5 ug Trypsin/LysC (MS grade, Promega) prepared in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Next day, the supernatants were collected and the peptides were purified using a modified Sp3 clean up protocol and finally solubilized in the mobile phase A (2% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water), sonicated and the peptide concentration was determined through absorbance at 280 nm measurement using a nanodrop instrument. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were included in the final dataset.

Orbitrap raw data was analyzed in DIA-NN 1.8.1 software (Data-Independent Acquisition by Neural Networks) [

39] through searching against the

Mus musculus spectral library containing 21946 proteins derived from the library-free mode of the software and allowing up to two tryptic missed cleavages. A spectral library was created from the DIA runs and used to reanalyze them. DIA-NN default settings have been used with oxidation of methionine residues and acetylation of the protein N-termini set as variable modifications and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues as fixed modification. N-terminal methionine excision was also enabled. The match between runs (MBR) feature was used for all analyses and the output (precursor) was filtered at 0.01 FDR and finally the protein inference was performed on the level of genes using only proteotypic peptides. The generated results were processed statistically and visualized in the Perseus software (1.6.15.0) [

40]. Intensity values were log (2) transformed, a threshold of 70% of valid values in at least one group was applied and the missing values were replaced from normal distribution (Width: 0.3, Down shift: 1.8). For statistical analysis, Student’s t-test was performed and permutation-based FDR was calculated using a 5% threshold.

4.5. Transcriptome vs Proteome Comparison

Processed, quantified transcriptome data were obtained from [

2](GEO: GSE93922) corresponding to a set of 24408 protein coding genes. Proteomics data were derived from this publication and resulted in a set of 6047 proteins using proteotypic peptides. We went on to compare the two lists and their accompanying fold change values, using the gene name as common identifier for both data types. Standard thresholds of absolute log2-Fold-change above 1 and adjusted p-values below 0.05 were applied to identify differentially expressed genes and differentially abundant proteins. 5483 genes/proteins were shared between the two lists. Correlation between relative expression values was calculated with Pearson’s correlation coefficient, for the entire dataset, a set of 3608 genes which were shared between the transcriptome list and the set of peptides with significantly altered abundance level (at an absolute cut-off value of 0.5) and an even more restricted set of 741 shared genes/peptides significantly at an absolute cut-off value of 1.

4.6. SUMO Immunoprecipitations (SUMO-IPs)

For the SUMO-IPs we used a previously established protocol [

41,

42]. Briefly, ESC (CGR8) and ESC -PLM cells (#23) were lysed using a denaturing lysis buffer containing 1%SDS. The cell lysate was then diluted to RIPA buffer conditions. 5 milligrams of total protein lysates from each cell line were incubated with mouse IgG, monoclonal anti-SUMO1 or anti-SUMO2/3 antibody (SUMO1 21C7 and SUMO2 8A2) coupled beads overnight, at 4 °C. SUMO conjugates were eluted with an excess of SUMO epitope spanning peptides as previously described [

41,

42,

43]. The experiment was performed in two biological replicates. INPUTS (input protein lysate) and eluted proteins from the two experiments were either analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies or send for proteomic analysis.

4.7. SUMO-IP Analysis

LC-MS/MS: Nano-liquid chromatography mediated separation of the resulting tryptic peptide mixture was carried out using a Ultimate3000 RSLC system. The volume needed for 500ng of peptides was loaded directly on a pepsep 25-cm long nano column (1.9μm3 beads, 75 µm ID). The peptide separation was achieved in 60 minutes using 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid in acetonitrile (ACN) (mobile phase B), starting with a gradient of 7% Buffer B to 35% Buffer B for 40 min and followed by an increase to 45% in 5 min and a second increase to 99% in 0.5min for 5.5 min and then kept constant for equilibration at 7% Buffer B for 4.5 min. The gradient flow rate was set to 400 nL/min in the first 10 minutes of the gradient and 250 nL/min in the main gradient.

The data acquisition was performed in positive mode using an Q Exactive HF-X Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). MS data were acquired in a data-dependent (DDA) strategy selecting up to top 12 precursors based on precursor abundance in the survey scan (m/z 350–1500). The resolution of the survey scan was 120,000 (at m/z 200) with a target value of 3 × 10E6 ions and a maximum injection time of 100 ms. HCD MS/MS spectra were acquired with a target value of 1x10E5 and resolution of 15,000 (at m/z 200) using an NCE of 28. The maximum injection time for MS/MS was 22 ms. Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 30s after one MS/MS spectra acquisition. Peptide match was set as preferred. The isolation window for MS/MS fragmentation was set to 1.2 m/z. Lock mass of m/z 445.12003 was used throughout the analysis. Three technical replicas were acquired per biological replicate.

4.8. Western Blot (WB)

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1%NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with protease phosphatase inhibitors inhibitor cocktail (Complete EDTA Free; Roche Applied Science). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Equal amounts of proteins (20 µg) were subjected to SDS/PAGE. Samples were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Hybond), blocked with 5% BSA in TBST, followed by immunoblotting. The SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo) was used to detect signal by ChemiDoc Imaging System (Biorad).

4.9. Protein Turnover Measurements

Cycloheximide (CHX, Sigma) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 150μg/ml. At various times of CHX treatment, cells were harvested and lysed. Equal amounts of total proteins were subjected to WB analysis.

4.10. Luciferase Assays

The TOPflash and Cyclin B1-luc reporter were transfected along with SALL1 1 or CDCA8 expressing plasmids in HEK293 cell lines using the Calcium Phosphate or Lipofectamine™ 2000 (ThermoFisher). 48 h after transfection, luciferase activities were measured from cell extracts using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

4.11. Luciferase Assays

All graphs and statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software. All graphs represent values as mean and the standard deviation (mean ± SD) or the standard error of the mean (mean ± SEM), as indicated in the figure legends. The p-value<0.05 was considered significant difference, determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA comparisons, as indicated in the figure legends. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, n.s (not significant).

5. Conclusions

Integrating our proteomics and sumoylomic data we demonstrate that PML maintains the pluripotency of ES cells by two mechanisms: 1. it increases the protein abundance levels of genes involved in cell cycle progression and self-renewal and 2. It activates the sumoylation of key regulators involved in pluripotency, chromatin and cell cycle by increasing the availability and accessibility of sumoylation-mediators to these targets.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Materials including Figure S1: Comparison between the PML-dependent transcriptome and proteome, Figure S2: The majority of PML sumoylation targets are PML-NB associated proteins, Figure S3: PML favors protein sumoylation in ES cells, Table S1: Whole Proteome Comparison PML KD vs WT, Table S2: PML Transriptome vs Proteome, Table S3: SUMO_IPs PML KD vs WT, Table S4_ Significant enriched proteins SUMO1 and SUMO 2, 3 -IP PML KD vs WT.

Author Contributions

SS designed and performed experiments, performed data analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TM, CF and GD performed experiments and helped with figures design. GS performed proteomic analyses. CN performed computational analyses and data visualization. MS supervised proteomic analyses and assisted with the interpretation of proteomics data. GC supervised the SUMO-IP experiments and assisted with data analysis and manuscript writing. JP designed experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. AK designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (Greece) GSRT Program RESEARCH CREATE-INNOVATE (project code: T1EDK-03186, Acronym: DINNESMIN, ΚA10186) and IMBB Internal Funding to AK. MS acknowledges support by the project “The Greek Research Infrastructure for Personalised Medicine (pMED-GR)” (MIS 5002802 under the Action “Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructure”, funded by the Operational Programme "Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation" (NSRF 2014-2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data deposition: The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD058024.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD058024.

Reviewer access details: Log in to the PRIDE website using the following details: Project accession: PXD058024. Token: qIUQTkMffKQT. Alternatively, reviewer can access the dataset by logging in to the PRIDE website using the following account details: Username: reviewer_pxd058024@ebi.ac.uk. Password: ZS4eEPfYaFN1

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Stathis Fantidis and Stella Bartzioka for their valuable help with some experiments. We thank Yorgos Vretzos for excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaenisch, R.; Young, R. Stem Cells, the Molecular Circuitry of Pluripotency and Nuclear Reprogramming. Cell 2008, 132, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjimichael, C.; Chanoumidou, K.; Nikolaou, C.; Klonizakis, A.; Theodosi, G.-I.; Makatounakis, T.; Papamatheakis, J.; Kretsovali, A. Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein Is an Essential Regulator of Stem Cell Pluripotency and Somatic Cell Reprogramming. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 8, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K. S.; Kao, H. Y. PML: and multRegulation ifaceted function beyond tumor suppression. Cell Biosci 2018, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzoglou, A.P.; Moretto, F.; Makkou, M.; Papamatheakis, J.; Kretsovali, A. Promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) and stem cells: from cancer to pluripotency. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 66, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Salomoni, P.; Pandolfi, P.P. The transcriptional role of PML and the nuclear body. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, E85–E90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpet, A.; Kleijwegt, C.; Roubille, S.; Juillard, F.; Jacquet, K.; Texier, P.; Lomonte, P. PML nuclear bodies and chromatin dynamics: catch me if you can! Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 11890–11912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gialitakis, M.; Arampatzi, P.; Makatounakis, T.; Papamatheakis, J. Gamma Interferon-Dependent Transcriptional Memory via Relocalization of a Gene Locus to PML Nuclear Bodies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 2046–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, M.; Kato, K.; Sanbo, C.; Shigenobu, S.; Ohkawa, Y.; Fuchigami, T.; Miyanari, Y. Genomic Profiling by ALaP-Seq Reveals Transcriptional Regulation by PML Bodies through DNMT3A Exclusion. Mol Cell 2020, 78, pp. 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, S.; Ferhi, O.; Geoffroy, M.-C.; González-Prieto, R.; Canat, A.; Quentin, S.; Pla, M.; Niwa-Kawakita, M.; Bercier, P.; Rérolle, D.; et al. Exploration of nuclear body-enhanced sumoylation reveals that PML represses 2-cell features of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.H.; Lin, H.-K.; Scaglioni, P.P.; Yung, T.M.; Pandolfi, P.P. The Mechanisms of PML-Nuclear Body Formation. Mol. Cell 2006, 24, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Ghali, M.; Lallemand-Breitenbach, V. PML Nuclear bodies: the cancer connection and beyond. Nucleus 2024, 15, 2321265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossec, J.-C.; Theurillat, I.; Chica, C.; Aguín, S.B.; Gaume, X.; Andrieux, A.; Iturbide, A.; Jouvion, G.; Li, H.; Bossis, G.; et al. SUMO Safeguards Somatic and Pluripotent Cell Identities by Enforcing Distinct Chromatin States. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 742–757.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Peng, S.; Hua, J. Eif2s3y regulates the proliferation of spermatogonial stem cells via Wnt6/-catenin signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, 118790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannarella, R.; Condorelli, R.A.; Mongioì, L.M.; La Vignera, S.; Calogero, A.E. Molecular Biology of Spermatogenesis: Novel Targets of Apparently Idiopathic Male Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.S.; Hada, M.; Shikata, D.; Watanabe, G.; Ogura, A.; Matoba, S. CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic screen of SCNT-reprogramming resistant genes identifies critical genes for male germ cell development in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maezawa, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Alavattam, K.G.; Funakoshi, M.; Sato, T.; Barski, A.; Namekawa, S.H. SCML2 promotes heterochromatin organization in late spermatogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs.217125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, J.A.; Liakath-Ali, K.; Green, R.; Watt, F.M. Translational control of stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Yan, K.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Q.C.; Lin, Y.; Xi, Q. Recruitment of TRIM33 to cell-context specific PML nuclear bodies regulates nodal signaling in mESCs. EMBO J. 2022, 42, e112058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlhase, J.; Wischermann, A.; Reichenbach, H.; Froster, U.; Engel, W. Mutations in the SALL1 putative transcription factor gene cause Townes-Brocks syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozal-Basterra, L.; Martín-Ruíz, I.; Pirone, L.; Liang, Y.; Sigurðsson, J.O.; Gonzalez-Santamarta, M.; Giordano, I.; Gabicagogeascoa, E.; de Luca, A.; Rodríguez, J.A.; et al. Truncated SALL1 Impedes Primary Cilia Function in Townes-Brocks Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzer, C.; Bohlander, S.K.; Rieger, L.; Müller, S.; Kohlhase, J. Interaction of the developmental regulator SALL1 with UBE2I and SUMO-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 296, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks I., A.; Vertegaal, A. C. O. A high-yield double-purification proteomics strategy for the identification of SUMO sites. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1630–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theurillat, I.; Hendriks, I.A.; Cossec, J.-C.; Andrieux, A.; Nielsen, M.L.; Dejean, A. Extensive SUMO Modification of Repressive Chromatin Factors Distinguishes Pluripotent from Somatic Cells (vol 32, pg 108146, 2020). Cell Rep. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, A.; Kishida, S.; Tanaka, T.; Kikuchi, A.; Kodama, T.; Asashima, M.; Nishinakamura, R. Sall1, a causative gene for Townes-Brocks syndrome, enhances the canonical Wnt signaling by localizing to heterochromatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 319, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Walker, E.; Tamplin, O.J.; Rossant, J.; Stanford, W.L.; Hughes, T.R. Borealin is differentially expressed in ES cells and is essential for the early development of embryonic cells. Mol Biol Rep 2009, 36, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, Y.; Heike, T.; Kumada, T.; Shibata, M.; Takaoka, Y.; Kitano, A.; Shiraishi, K.; Kato, T.; Nagato, M.; Okawa, K.; et al. Loss of Borealin/DasraB leads to defective cell proliferation, p53 accumulation and early embryonic lethality. Mech. Dev. 2008, 125, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, U. R.; Haindl, M.; Nigg, E. A.; Muller, S. RanBP2 and SENP3 function in a mitotic SUMO2/3 conjugation-deconjugation cycle on Borealin. Mol Biol Cell 2009, 20, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jiang, N. CDCA8 Facilitates Tumor Proliferation and Predicts a Poor Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2024, 196, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Peng, Q.; Li, R.; Lyu, X.; Zhu, C.; Qin, X. Cell division cycle associated 8: A novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 11097–11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisakhtnezhad, S. In silico analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data from 3 and 7 days old mouse spermatogonial stem cells to identify their differentially expressed genes and transcriptional regulators. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 7556–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantzali, E.; Lekakis, V.; Ioannou, M.; Hadjimichael, C.; Papamatheakis, J.; Kretsovali, A. Sall1 Regulates Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation in Association with Nanog. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusse, R. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Gomila, O.; Trulsson, F.; Muratore, V.; Canosa, I.; Merino-Cacho, L.; Cortazar, A.R.; Pérez, C.; Azkargorta, M.; Iloro, I.; Carracedo, A.; et al. Identification of proximal SUMO-dependent interactors using SUMO-ID. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, R. Borealin: a novel chromosomal passenger required for stability of the bipolar mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol 2004, 166, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Lee, S.H. The chromosomal passenger complex (CPC) as a key orchestrator of orderly mitotic exit and cytokinesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 14–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campeau, E.; Ruhl, V.E.; Rodier, F.; Smith, C.L.; Rahmberg, B.L.; Fuss, J.O.; Campisi, J.; Yaswen, P.; Cooper, P.K.; Kaufman, P.D. A Versatile Viral System for Expression and Depletion of Proteins in Mammalian Cells. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e6529–e6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.S.; Moggridge, S.; Müller, T.; Sorensen, P.H.; Morin, G.B.; Krijgsveld, J. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods 2019, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barysch, S. V.; Dittner, C.; Flotho, A.; Becker, J.; Melchior, F. Identification and analysis of endogenous SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 targets in mammalian cells and tissues using monoclonal antibodies. Nat Protoc 2014, 9, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.; Barysch, S.V.; Karaca, S.; Dittner, C.; Hsiao, H.-H.; Berriel Diaz, M.; Herzig, S.; Urlaub, H.; Melchior, F. Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chachami, G.; Stankovic-Valentin, N.; Karagiota, A.; Basagianni, A.; Plessmann, U.; Urlaub, H.; Melchior, F.; Simos, G. Hypoxia-induced Changes in SUMO Conjugation Affect Transcriptional Regulation Under Low Oxygen. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2019, 18, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The PML dependent proteome of ES cells. Comparison with the transcriptome. (a) Volcano plot representation of the proteins that are under- or over-abundant in the absence of PML (PML KD) (at an absolute cut-off value of 0.5). Highly deregulated proteins are annotated. PML and spermatogenesis-related proteins are colored in red. (b) Scatter plot showing the gene expression and protein abundance relative values for 741 genes/peptides with absolute change >1 at protein level. Correlation between gene expression and protein changes was r=0.23 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p<=10-10). Red dots mark genes with concordant changes, blue dots mark genes with discordant changes. The top 30 most divergent genes are annotated. (c, d) ShinyGO 0.8 representation of GO categories linked to down (C) or up (D) regulated proteins in PML KD cells at the <-0.5 and/or >0.5 cutoff.

Figure 1.

The PML dependent proteome of ES cells. Comparison with the transcriptome. (a) Volcano plot representation of the proteins that are under- or over-abundant in the absence of PML (PML KD) (at an absolute cut-off value of 0.5). Highly deregulated proteins are annotated. PML and spermatogenesis-related proteins are colored in red. (b) Scatter plot showing the gene expression and protein abundance relative values for 741 genes/peptides with absolute change >1 at protein level. Correlation between gene expression and protein changes was r=0.23 (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p<=10-10). Red dots mark genes with concordant changes, blue dots mark genes with discordant changes. The top 30 most divergent genes are annotated. (c, d) ShinyGO 0.8 representation of GO categories linked to down (C) or up (D) regulated proteins in PML KD cells at the <-0.5 and/or >0.5 cutoff.

Figure 2.

PML regulates the expression of proteins involved in ES cell self-renewal, translation and proteasome. Hierarchical analysis (Heatmaps) of z-scores for protein abundances in Biological Processes (GOBP) that are either down- or up- regulated in PML KD cells in comparison with the WT. (a) Mitotic Cell cycle, (b) JAK-STAT3 signaling, (c) PML body, (d) Protein sumoylation, (e) Ribonucleoprotein biogenesis, (f) Translation initiation, (g) Cytoplasmic translation, (h) Proteasome. Color key indicates protein expression value (blue: lowest; red: highest). Each column represents a biological replicate (n=3) for WT or PML KD ESC. Proteins were clustered using the Perseus software.

Figure 2.

PML regulates the expression of proteins involved in ES cell self-renewal, translation and proteasome. Hierarchical analysis (Heatmaps) of z-scores for protein abundances in Biological Processes (GOBP) that are either down- or up- regulated in PML KD cells in comparison with the WT. (a) Mitotic Cell cycle, (b) JAK-STAT3 signaling, (c) PML body, (d) Protein sumoylation, (e) Ribonucleoprotein biogenesis, (f) Translation initiation, (g) Cytoplasmic translation, (h) Proteasome. Color key indicates protein expression value (blue: lowest; red: highest). Each column represents a biological replicate (n=3) for WT or PML KD ESC. Proteins were clustered using the Perseus software.

Figure 3.

PML promotes the sumoylation of key regulators involved in ES cell pluripotency. (a) immuno-detection of bulk SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 modified proteins in WT and PML KD cells. WB using anti-SUMO1 and SUMO-2, 3 antibodies. (b, c) Enriched terms across genes coding for proteins under-sumoylated in PML KD cells. B. SUMO-1, C. SUMO-2,3 (Metascape). (d, e) Volcano plots displaying the log2 fold change (x axis) against the t test–derived −log10 statistical P value (y axis) for proteins proteins that are strongly under-sumoylated in PML KD cells, regarding chromatin organization (green), pluripotency (blue) and cell cycle (red), by Perseus software (n = 3, FDR=0.05). Down-regulated proteins are displayed on the left (negative log2 fold change values) and up-regulated proteins on the right (positive log2 fold change values). (d) SUMO-1 (e) SUMO-2,3. (f) Heatmap presenting common SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 target proteins that are under-sumoylated in PML KD showing the abundances of SUMO IP in PML KD against WT and the corresponding protein abundances.

Figure 3.

PML promotes the sumoylation of key regulators involved in ES cell pluripotency. (a) immuno-detection of bulk SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 modified proteins in WT and PML KD cells. WB using anti-SUMO1 and SUMO-2, 3 antibodies. (b, c) Enriched terms across genes coding for proteins under-sumoylated in PML KD cells. B. SUMO-1, C. SUMO-2,3 (Metascape). (d, e) Volcano plots displaying the log2 fold change (x axis) against the t test–derived −log10 statistical P value (y axis) for proteins proteins that are strongly under-sumoylated in PML KD cells, regarding chromatin organization (green), pluripotency (blue) and cell cycle (red), by Perseus software (n = 3, FDR=0.05). Down-regulated proteins are displayed on the left (negative log2 fold change values) and up-regulated proteins on the right (positive log2 fold change values). (d) SUMO-1 (e) SUMO-2,3. (f) Heatmap presenting common SUMO-1 and SUMO-2,3 target proteins that are under-sumoylated in PML KD showing the abundances of SUMO IP in PML KD against WT and the corresponding protein abundances.

Figure 4.

Sumoylation increases the stability and Wnt-pathway enhancement activity of SALL1. (a) K1085R mutant SALL1 shows decreased sumoylation levels when compared with the WT. SUMO co-IP followed by WB analysis using a-GFP, a-SUMO-1 or a-SUMO-2,3 antibodies (b) The half-life of SALL11 was measured after the addition of 150μg/ml CHX for the indicated points in the absence or presence of ML-792 (1μM) for 24 hrs. Protein extracts from control or treated cells were subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. (c) Luciferase assay using extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with the TOPFlash-luc reporter in the presence of SALL1 WT or K1086R mutant expressing constructs. Graph represents mean values ± SEM (n=4, * p≤0.0176; Two-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Sumoylation increases the stability and Wnt-pathway enhancement activity of SALL1. (a) K1085R mutant SALL1 shows decreased sumoylation levels when compared with the WT. SUMO co-IP followed by WB analysis using a-GFP, a-SUMO-1 or a-SUMO-2,3 antibodies (b) The half-life of SALL11 was measured after the addition of 150μg/ml CHX for the indicated points in the absence or presence of ML-792 (1μM) for 24 hrs. Protein extracts from control or treated cells were subjected to WB with the indicated antibodies. (c) Luciferase assay using extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with the TOPFlash-luc reporter in the presence of SALL1 WT or K1086R mutant expressing constructs. Graph represents mean values ± SEM (n=4, * p≤0.0176; Two-way ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Sumoylation regulates the stability and the cell cycle progression activity of CDCA8. (a) Half-life of CDCA8 following the addition of CHX for 4 and 7 hrs on HEK293 stable cell lines expressing GFP/CDCA8 WT and Sumoylation mutant (Mut). Cell extracts were subjected to WB using a-GFP antibody. (b) Growth curve of GFP, GFP/CDCA8 WT and GFP/CDCA8 MUT expressing cell lines. (n=3, ** p≤0.0044, *** p<0.0001; Two-way ANOVA) (c) Luciferase assay using extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with the CyclinB1-luc reporter in the presence of CDCA8 WT or sumoylation mutant expressing constructs. Graph represents mean values ± SEM (n=5, * p≤0.0487, *** p=0.0007; Two-way ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Sumoylation regulates the stability and the cell cycle progression activity of CDCA8. (a) Half-life of CDCA8 following the addition of CHX for 4 and 7 hrs on HEK293 stable cell lines expressing GFP/CDCA8 WT and Sumoylation mutant (Mut). Cell extracts were subjected to WB using a-GFP antibody. (b) Growth curve of GFP, GFP/CDCA8 WT and GFP/CDCA8 MUT expressing cell lines. (n=3, ** p≤0.0044, *** p<0.0001; Two-way ANOVA) (c) Luciferase assay using extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with the CyclinB1-luc reporter in the presence of CDCA8 WT or sumoylation mutant expressing constructs. Graph represents mean values ± SEM (n=5, * p≤0.0487, *** p=0.0007; Two-way ANOVA).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).