Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

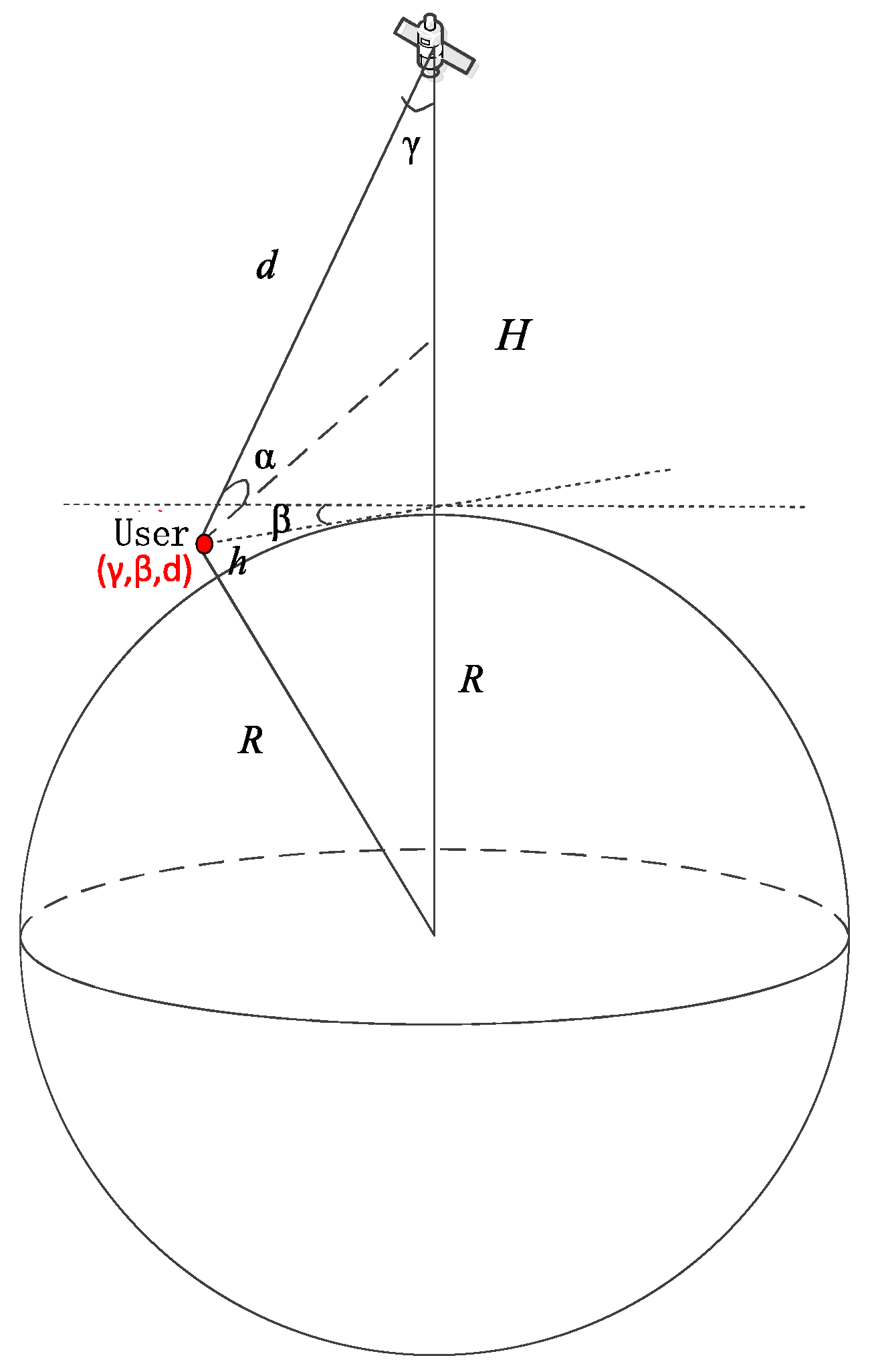

2.1. Multi-Beam Signal Power Observation Model

2.2. Power Perception Measurement Error Model

2.3. A System of Equations for Power Observations

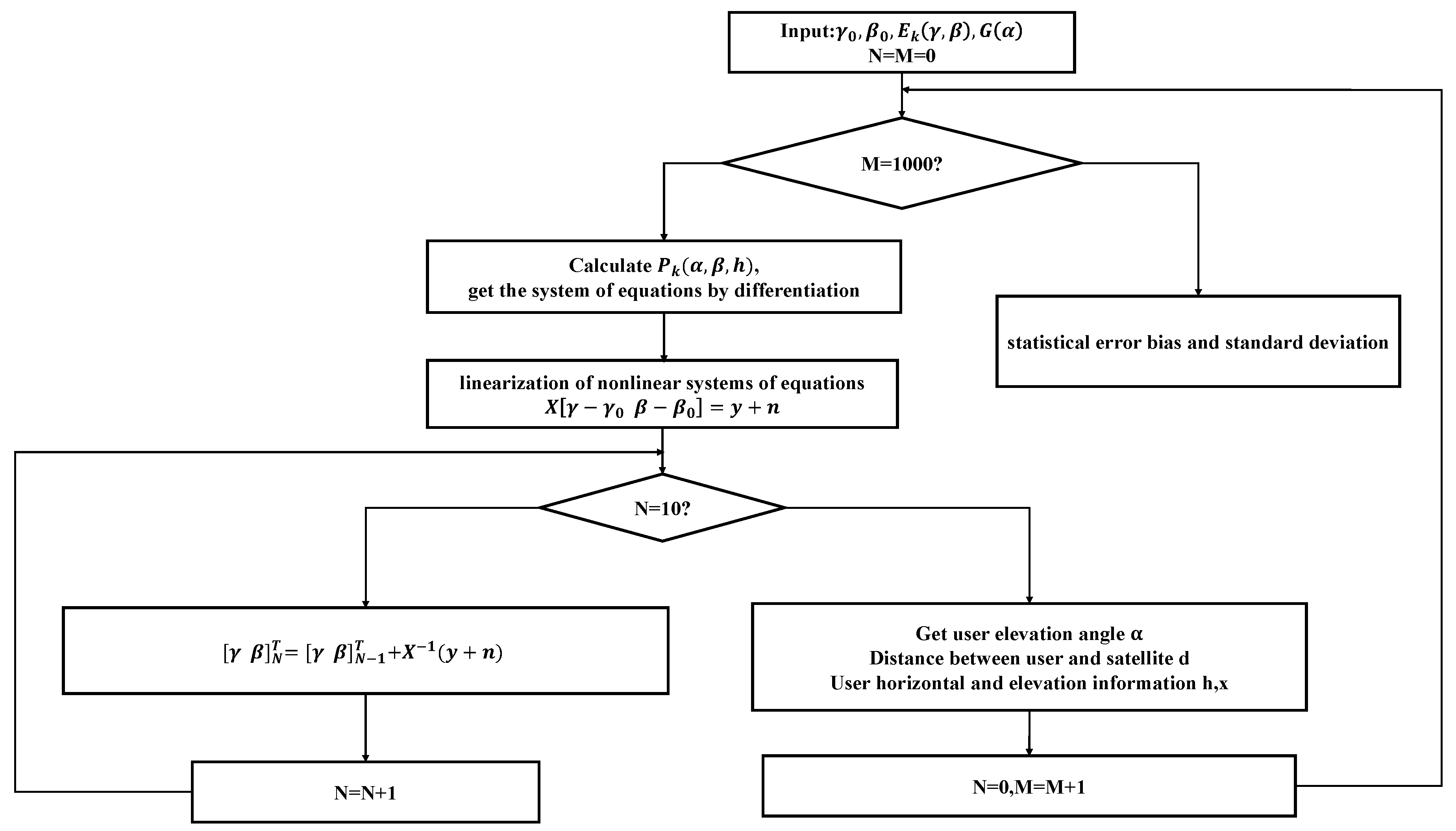

2.4. Power Positioning Algorithm Solution Process

3. Results

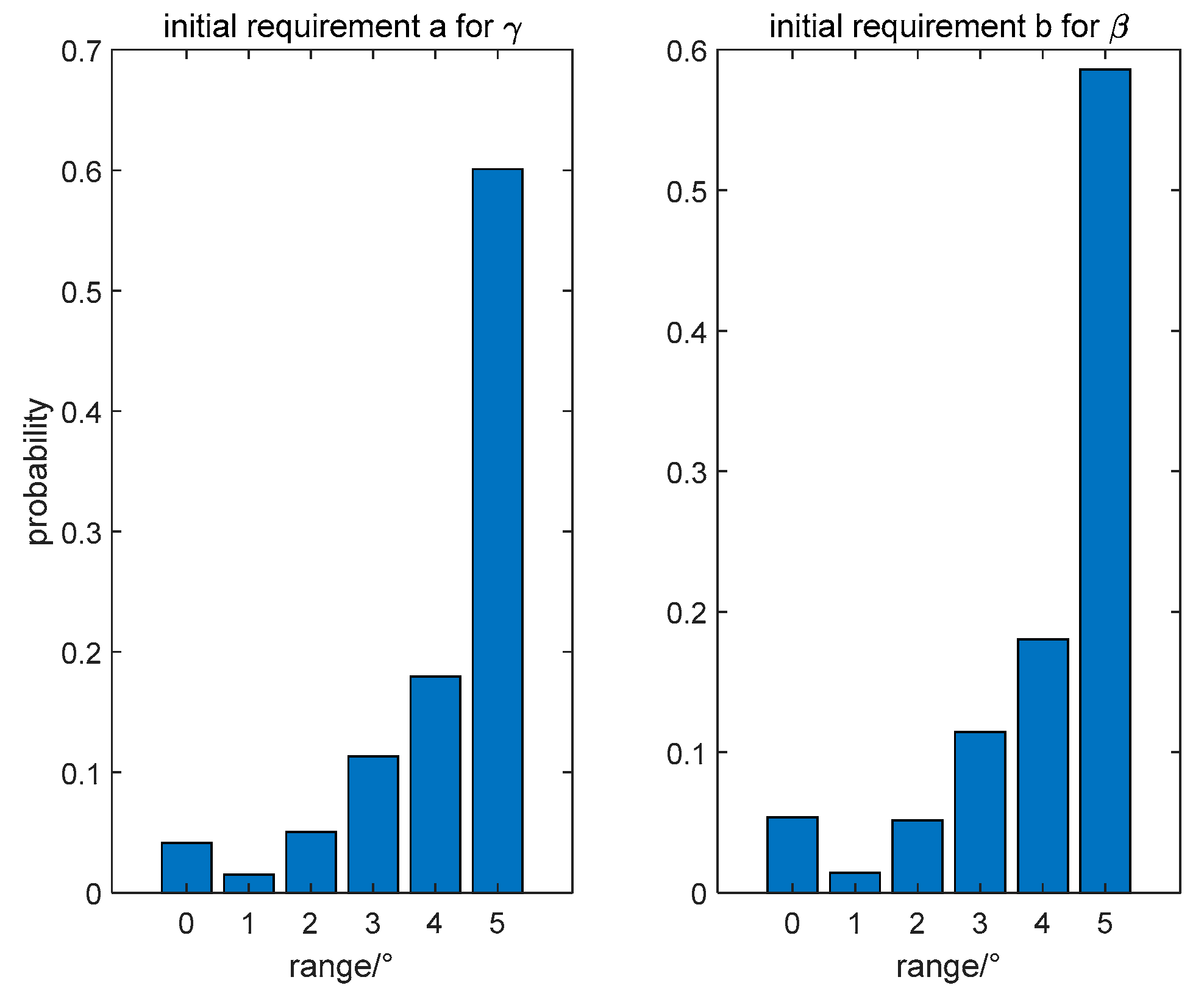

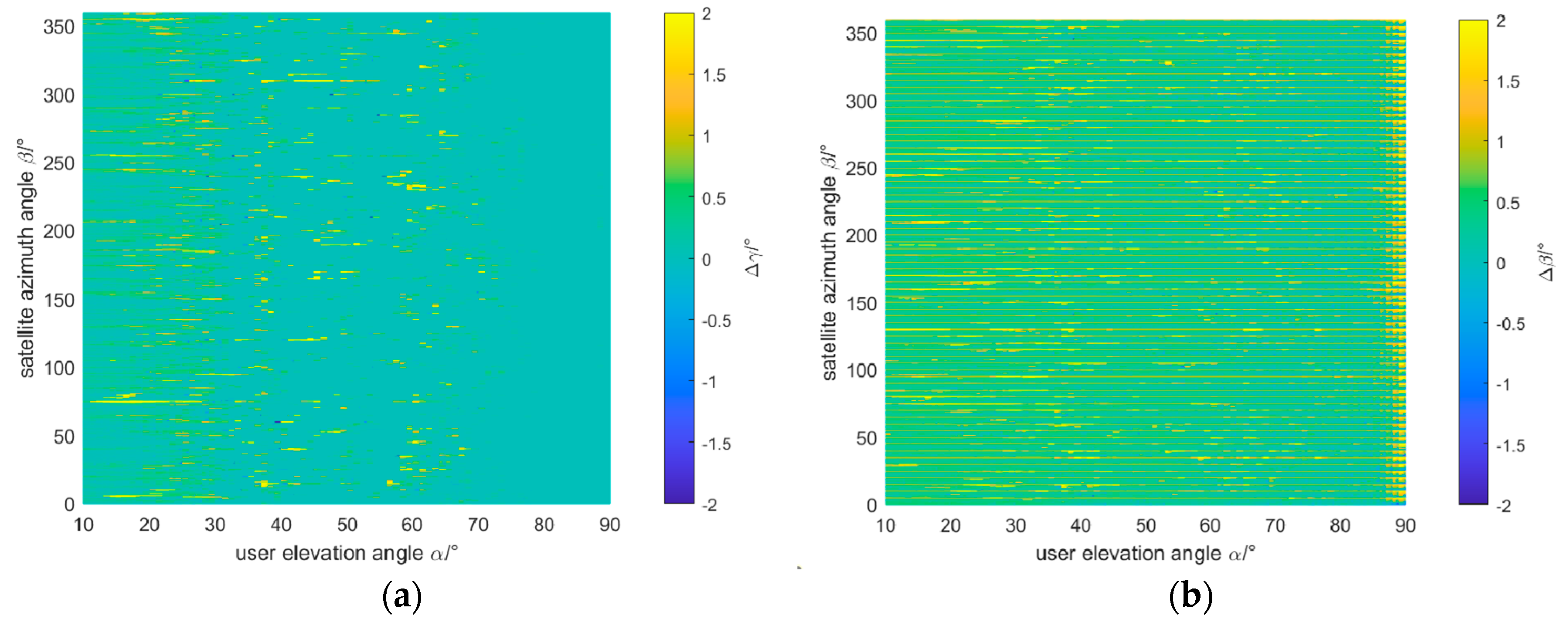

3.1. Least Squares Initial Value Requirements and Acquisition

3.1.1. Least Squares Solves the Initial Value Requirements

3.1.2. Initial Values of the Iteration by the Nearest Neighbor Algorithm Obtains

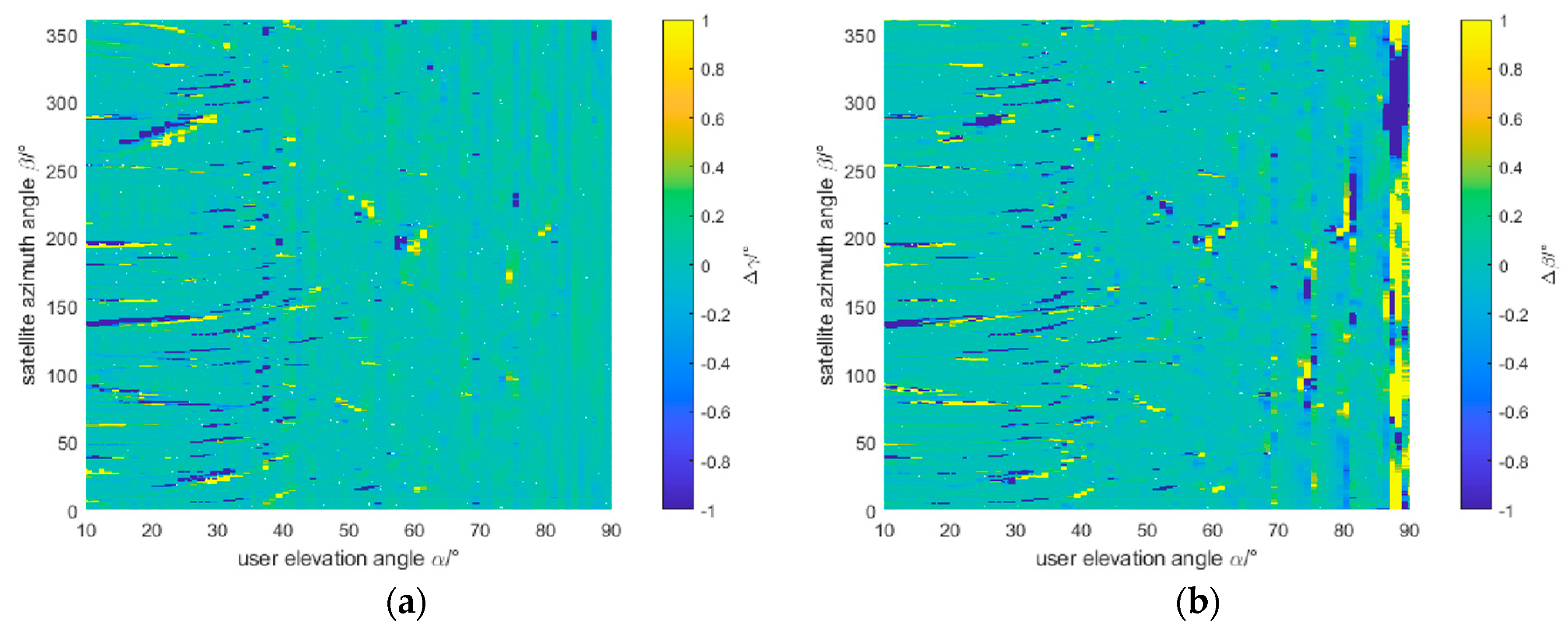

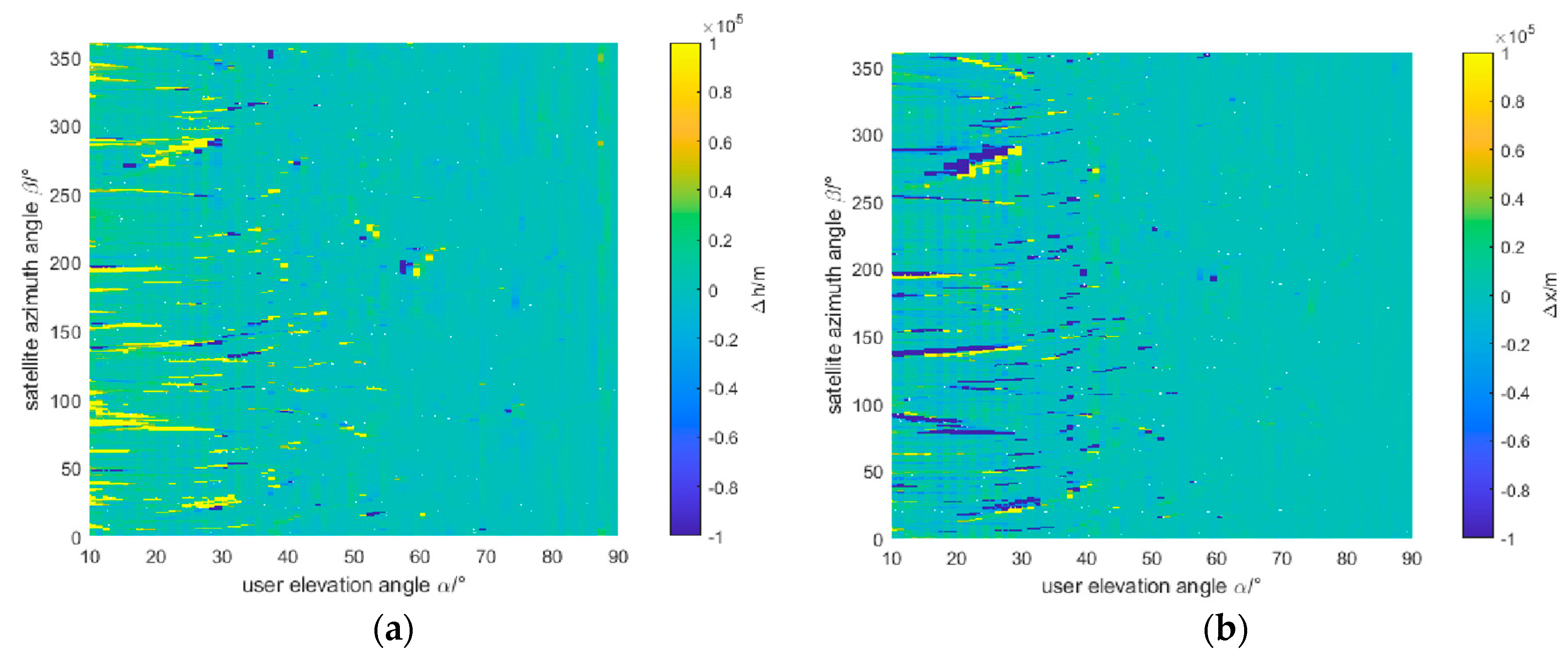

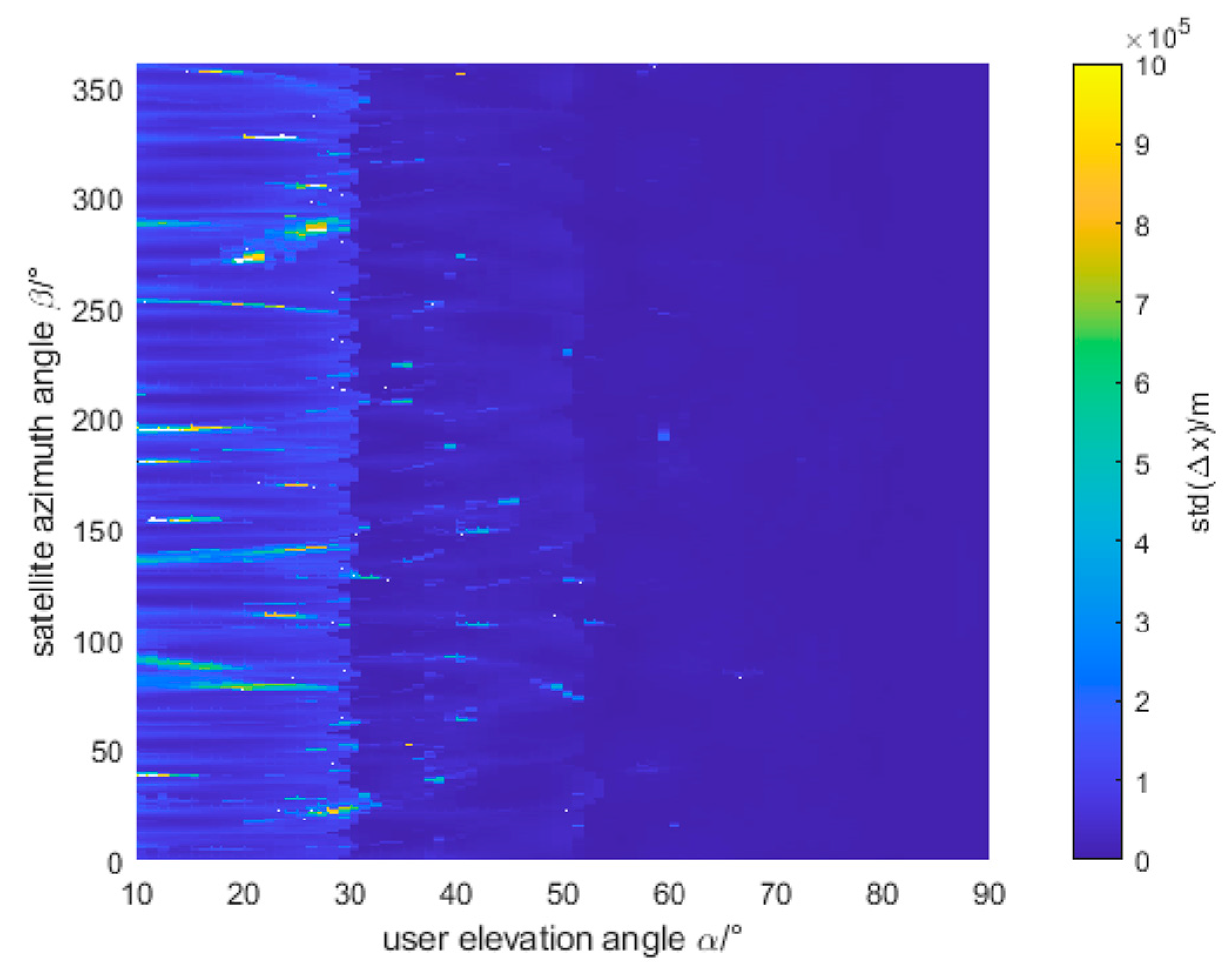

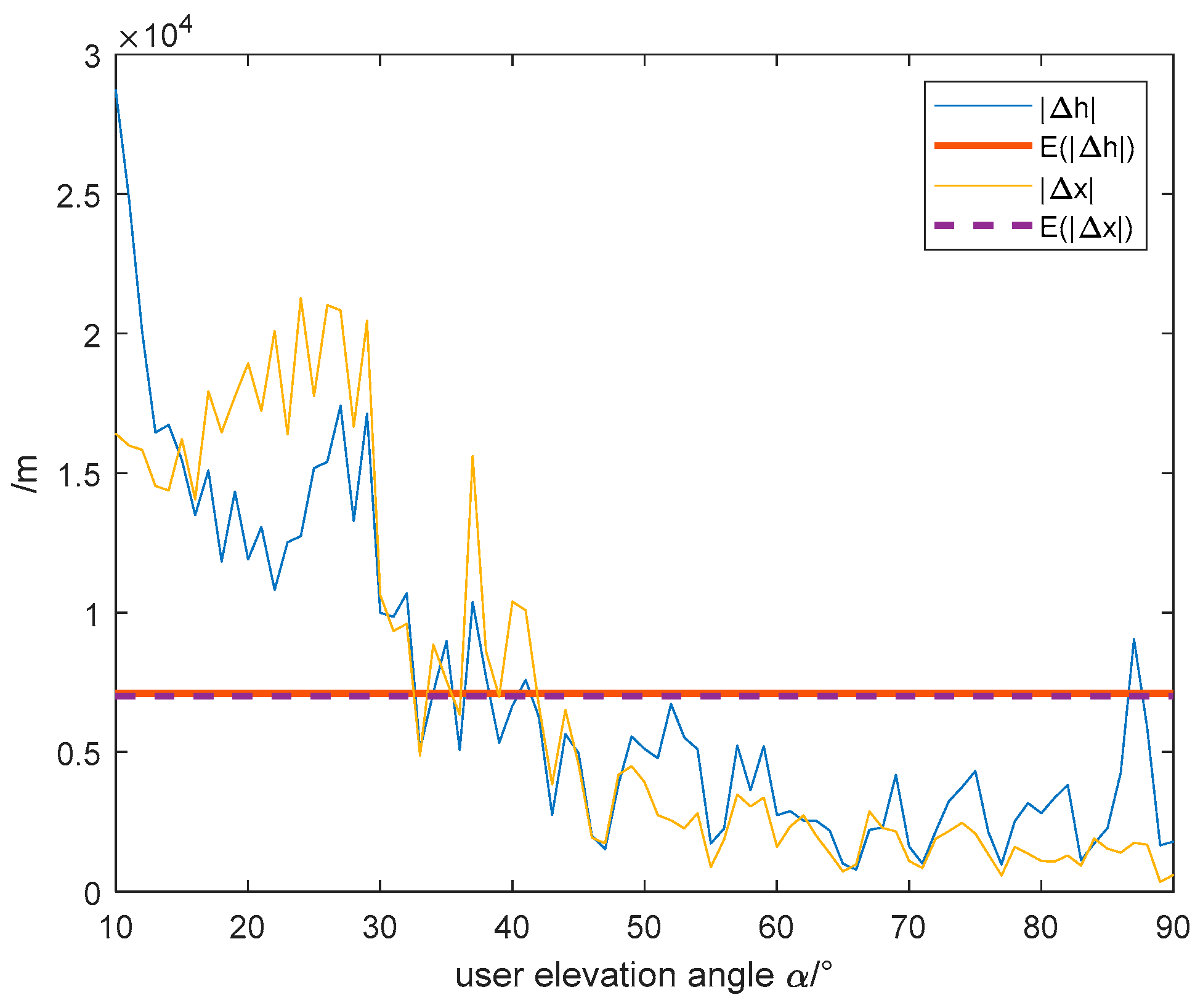

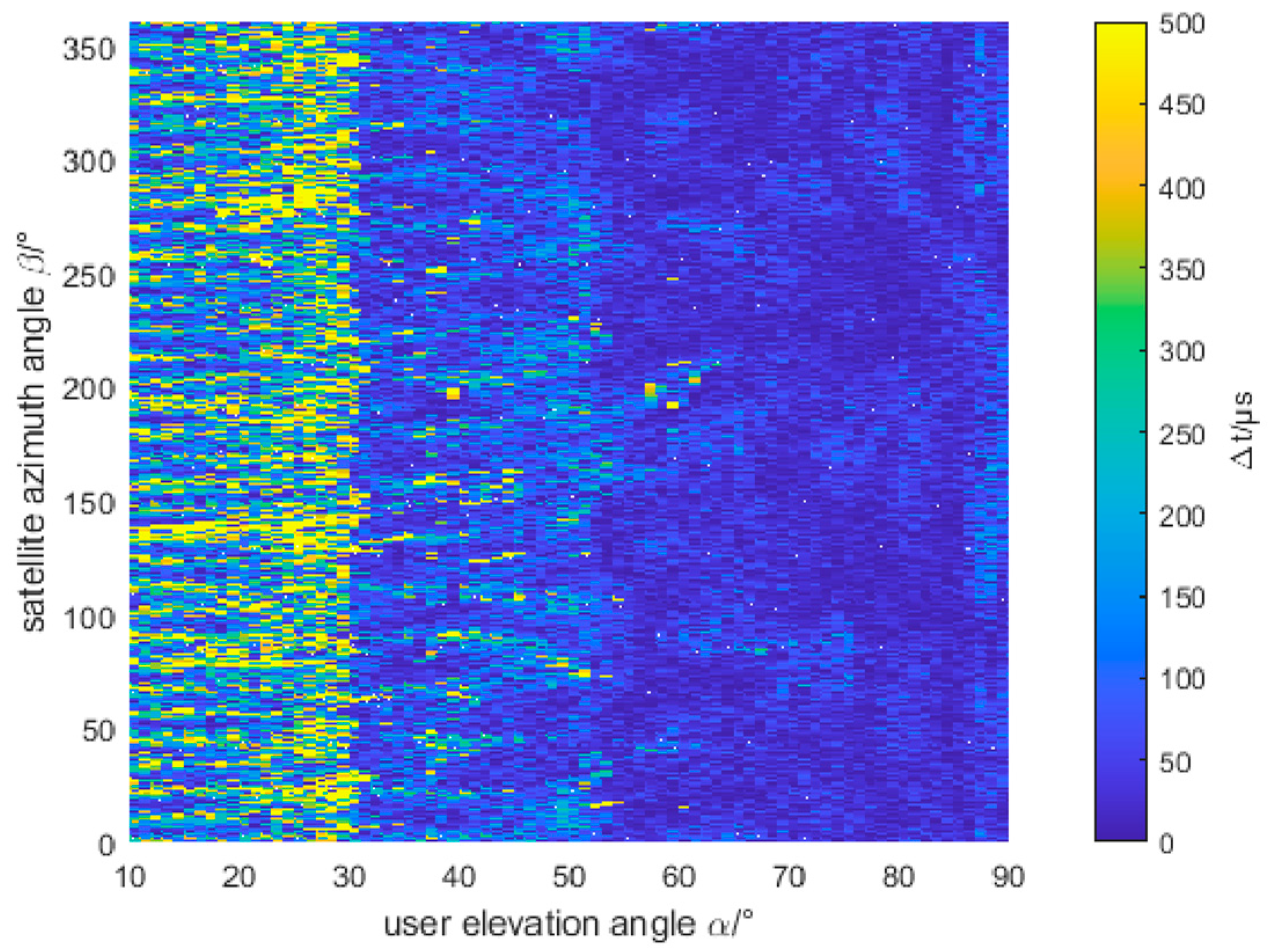

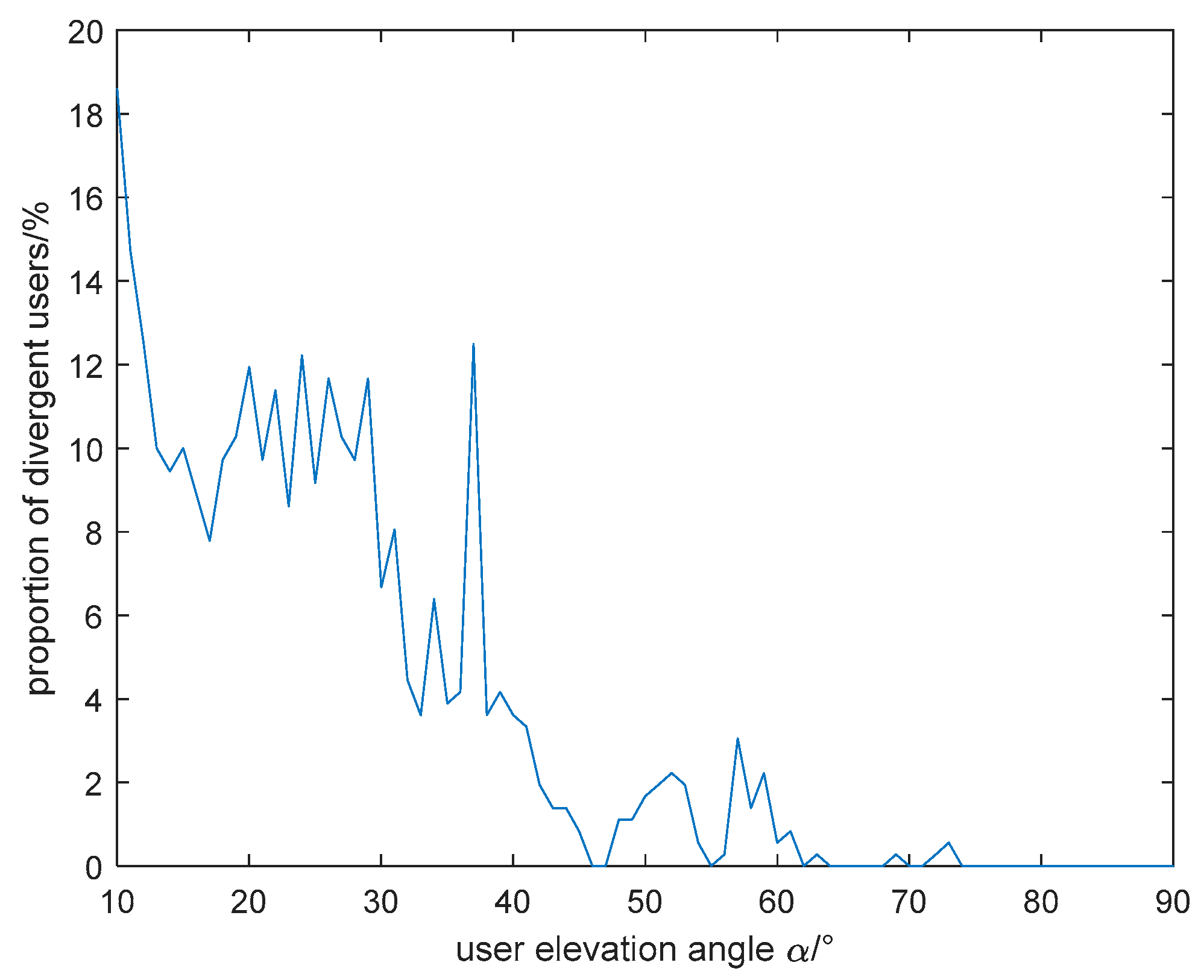

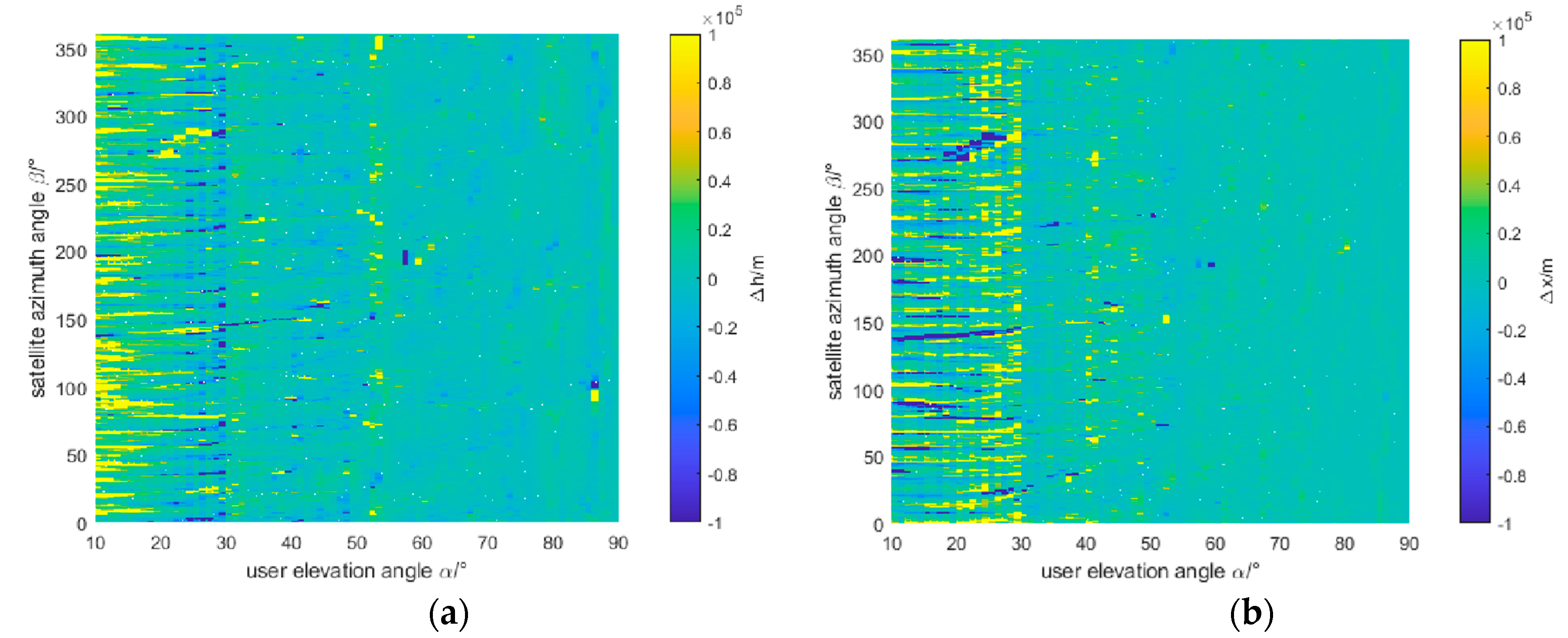

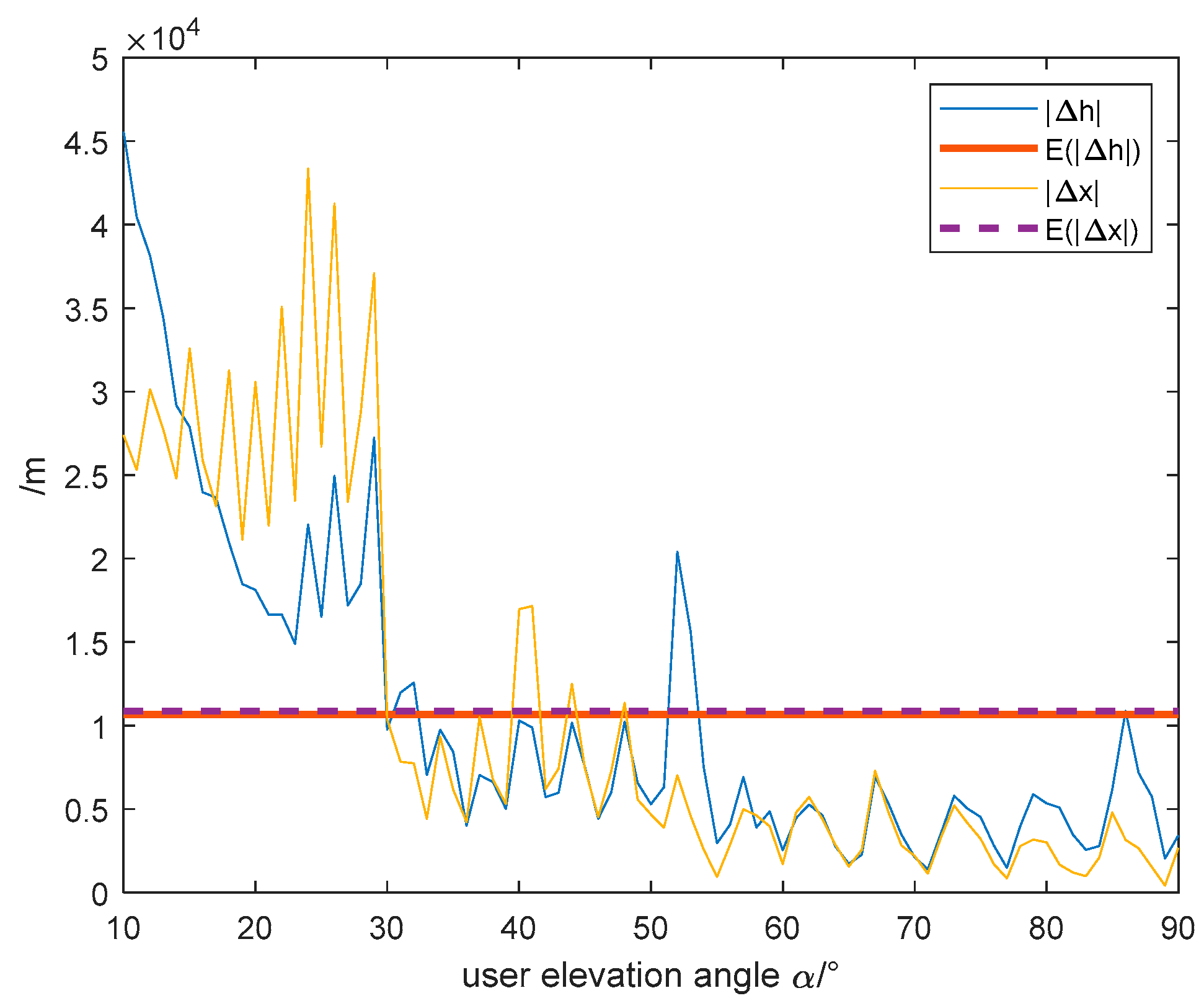

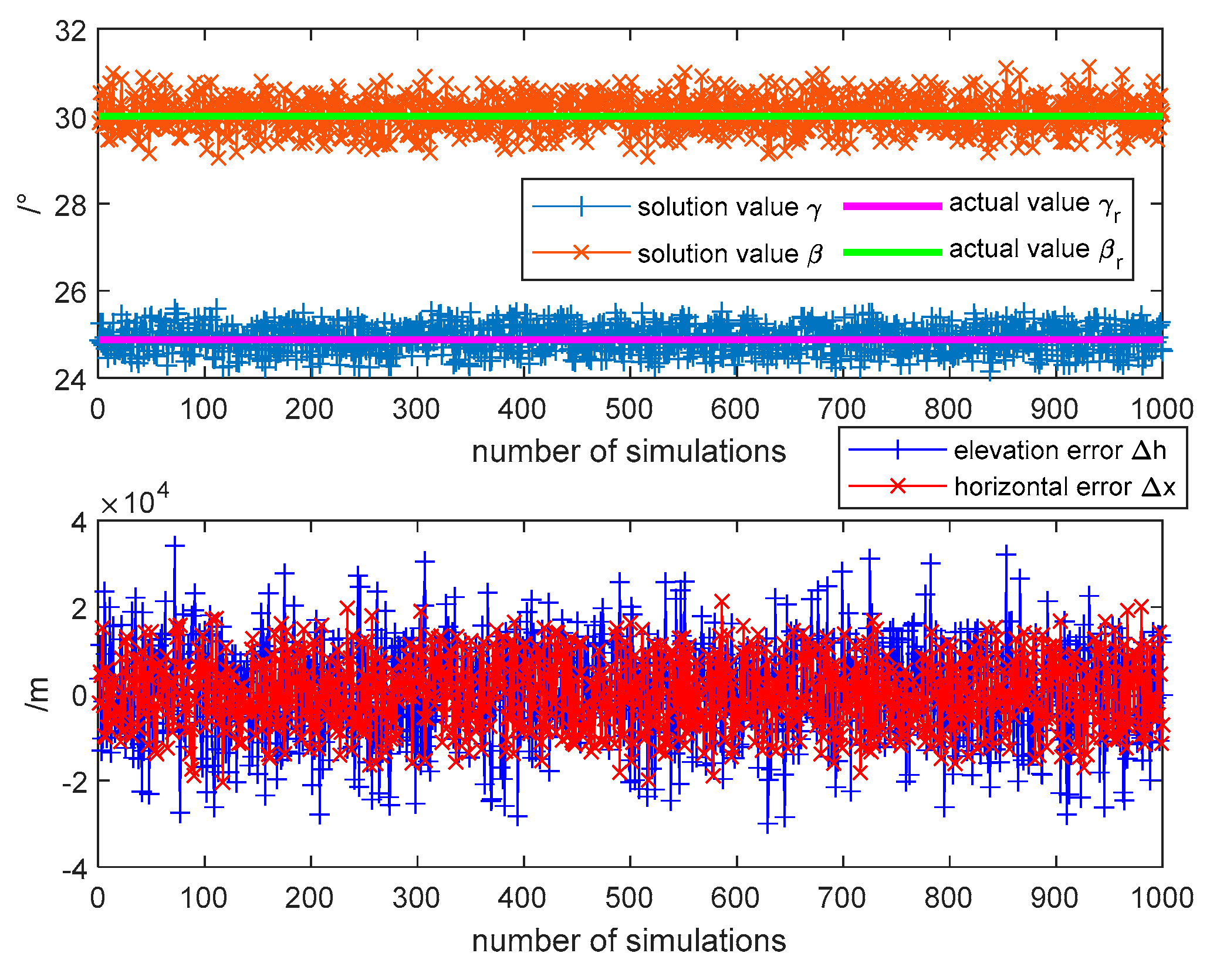

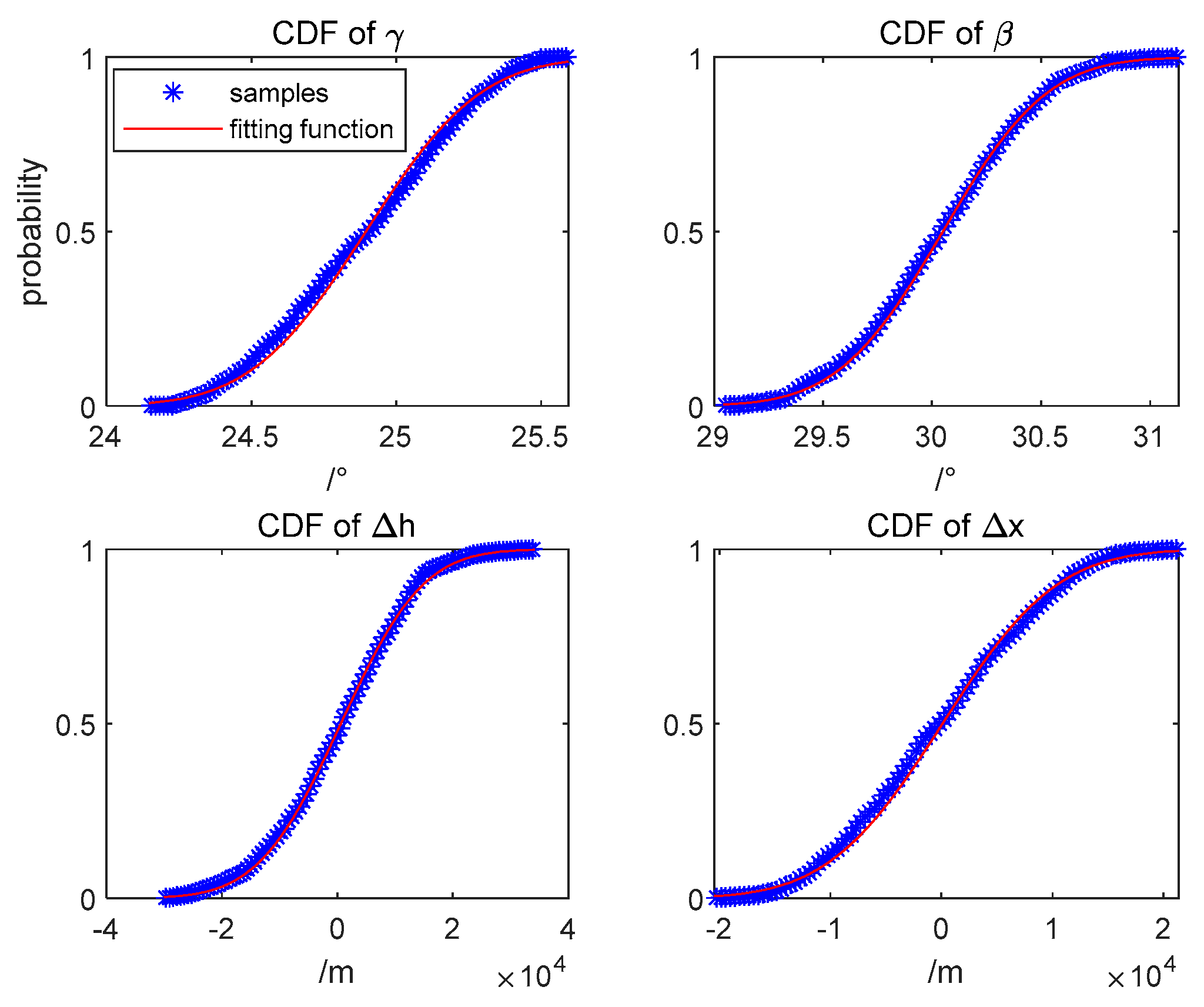

3.2. Analysis of Single-User Positioning Error

4. Discussion

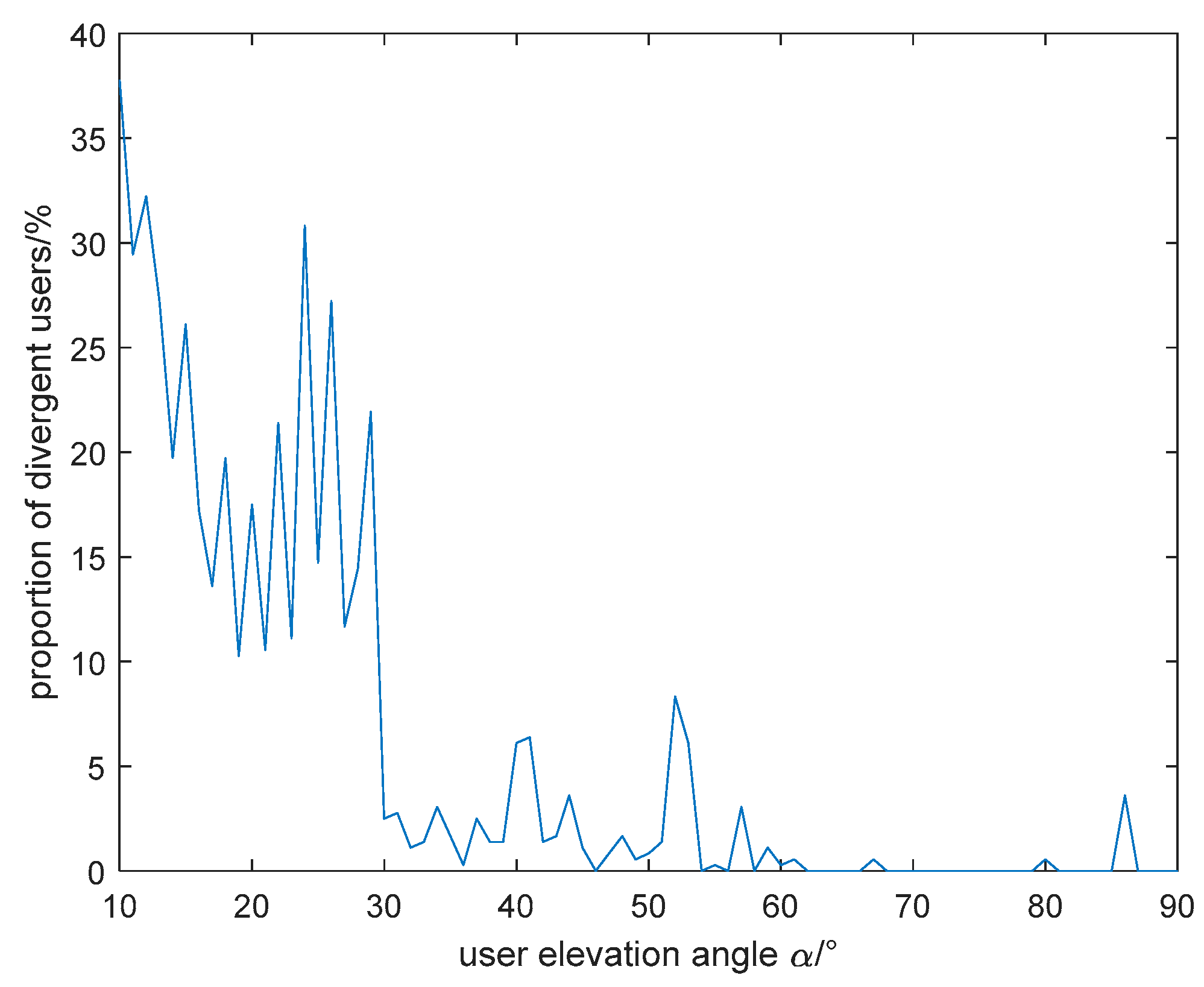

4.1. Different User Location

4.2. Received Power and Sensitivity

| User elevation angle range | Evaluation criteria | /m | /m | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10,90] | deviation | 0.1349 | 0.2028 | 10650 | 10869 |

| std | 0.3724 | 0.6374 | 28955 | 33410 | |

| [10,30] | deviation | 0.1639 | 0.1556 | 24052 | 28155 |

| std | 0.5325 | 0.4881 | 65283 | 90783 | |

| [30,90] | deviation | 0.1239 | 0.2177 | 6022.1 | 4910.3 |

| std | 0.3174 | 0.6847 | 16740 | 13961 |

5. Conclusions

References

- Yuanxi Yang; Yue Mao, et al. Demand and key technology for a LEO constellation as augmentation of satellite navigation systems. Satellite Navigation,2024, Vol.5(1): 1-9.

- Run Tian, Zhiying Cui, Shuangna Zhang, et al. Overview of the Development of Navigation Augmentation Technology Based on Low-orbit Communication Constellation. Navigation Positioning and Timing, 2021,8(1):66-81.

- Benzerrouk H, Nguyen Q, Fang X X, et al. 2019 26th Saint Petersburg International Conference on Integrated Navigation Systems (ICINS). St. Petersburg: IEEE,2019: 1.

- Xingxing Li; Yehao Zhao, et al. LEO real-time ambiguity-fixed precise orbit determination with onboard GPS/Galileo observations. GPS Solutions,2024, Vol.28(4).

- Morales-Ferre, R., Lohan, E. S., Falco, G., & Falletti, E. GDOP-based analysis of suitability of LEO constellations for future satellite-based positioning. In8th IEEE international conference on wireless for space and extreme environments (WiSEE), 2020, pp. 147–152.

- Psiaki, M. L. Navigation using carrier Doppler shift from a LEO constellation: TRANSIT on steroids. Navigation,2021,68(3), 621–641.

- Tan, Z., Qin, H., Cong, L., & Zhao, C. New method for positioning using Iridium satellite signals of opportunity. IEEE Access,2019, 7:83412–83423.

- Fei Guo; Yan Yang et al. Instantaneous velocity determination and positioning using Doppler shift from a LEO constellation. Satellite Navigation,2023.

- Sgammini, M., Cannas, A., Carchiolo, V., Giorgetti, G., & Veronesi, F. High-precision vehicular navigation using Doppler radars: A review and future directions. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics,2019, 17(1), 345-362.

- Ju Hong; Rui Tu, et al. GNSS rapid precise point positioning enhanced by low Earth orbit satellites. Satellite Navigation,2023, Vol.4(1): 1-13.

- Chuang Shi; Yulu Zhang, et al. Revisiting Doppler positioning performance with LEO satellites. GPS Solutions,2023, Vol.27(3).

- Jingxue Bi; Yunjia Wang, et al. Supplementary open dataset for WiFi indoor localization based on received signal strength [J]. Satellite Navigation,2022, Vol.3(1): 1-15.

- KAN C, DING G, WU Q, et al. Robust Relative Fingerprinting-Based Passive Source Localization via Data Cleansing [J]. IEEE Access,2018,6:19295-19269.

- Kaemarungsi, K., & Krishnamurthy, P. Modeling of indoor positioning systemsbased on location fingerprinting. In IEEE INFOCOM 2004, Vol. 2, pp. 1012–1022.

- Li, J., Gao, X., Hu, Z., et al. Indoor localization method based on regional division with IFCM. Electronics, 2019,8(5), 559.

- Feng, Y., Minghua, J., Jing, L., Xiao, Q., Ming, H., Tao, P., & Xinrong, H. Improved AdaBoost-based fingerprint algorithm for WiFi indoor localization. In 2014 IEEE 7th joint international information technology and artificial intelligence conference,2014, pp. 16–19.

- Li, Y., et al.Toward location-enabled IoT (LE-IoT): IoT positioning techniques, error sources, and error mitigation. IEEE Internet of Things Journal,2021,8(6), 4035–4062.

- Chen, G., Meng, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Tian, P., & Yang, H.Integrated WiFi/PDR/smartphone using an unscented Kalman filter algorithm for 3d indoor localization. Sensors,2015,15, 24595–24614.

- Bi, J., Wang, Y., Li, X., Cao, H., Qi, H., & Wang, Y. A novel method of adaptive weighted K-nearest neighbor fingerprint indoor positioning considering user’s orientation. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks,2018.

- Deng, Z., Fan, J., & Jiao, J. D-SVM fusion clustering algorithm based on indoor location.2018.

| Parameter type | Parameter value |

| Earth radius | 6371km |

| Satellite orbital altitude | 1200km |

| User elevation angle | [10,90] |

| Satellite elevation angle | can be calculated by |

| satellite azimuth angle | [,360] |

| Total number of satellite beams | 52 |

| User geodetic height | 0m |

| User gain | 0dB |

| Noise bandwidth | 1000Hz |

| Noise temperature | 290K |

| Least squares iterations | 10 |

| Number of power fingerprint bank beams | 10 |

| Receiver sensitivity | -160dBm, -190dBm |

| User elevation angle range | Evaluation criteria | /m | /m | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10,90] | deviation | 0.1038 | 0.1239 | 7093.5 | 7009.3 |

| std | 0.5016 | 1.1811 | 31720 | 53403 | |

| [10,30] | deviation | 0.1683 | 0.0996 | 15546 | 17180 |

| std | 0.9562 | 1.9617 | 74503 | 165260 | |

| [30,90] | deviation | 0.0817 | 0.1316 | 4231.2 | 3567.1 |

| std | 0.3455 | 0.8340 | 17385 | 15062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).