1. Introduction

Due to the high greenhouse gas emissions of fossil fuels, they are disadvantageous for electricity generation as they contribute to acid rain and especially global warming [

1]. The transition to renewable and low-carbon energy systems has accelerated worldwide. As a result, interest in geothermal energy is increasing [

2]. Geothermal energy is a renewable and reliable energy source [

3]. It is thermal energy obtained by utilizing the Earth’s internal heat. The source temperature determines the application areas of geothermal energy. According to the literature, geothermal resources are classified as high, medium, and low-temperature geothermal resources. Generally, sources with temperatures of 90°C and above are used for electricity generation [

4]. Different designs and optimization studies are required to generate electricity from geothermal sources with varying temperatures. Optimization involves analyzing the efficiency, cost analysis, and environmental impacts of the plants. By optimizing the use of geothermal resources for electricity generation, efficient and effective designs can be achieved [

5].

One of the main challenges in the optimization of power plants is solving nonlinear problems. Moreover, numerous calculations must be performed on a large number of plant equipment and parameters. These calculations are inherently lengthy, exhausting, and may lead to human errors. To prevent this, methods such as artificial neural networks and genetic algorithms, which have proven reliable predictive capabilities in the literature, stand out. The optimization of geothermal power plants using both methods has been explained [

6]. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are innovative approaches that process data by using connections between multiple inputs and outputs. ANNs are developed by taking inspiration from the human brain’s data processing mechanism [

7]. This method interprets data through machine learning, classification by labeling, and clustering of raw inputs. By establishing relationships between inputs and outputs, ANNs reveal the features among the data, thereby creating a model that can establish relationships similar to nonlinear classification and regression analyses [

8]. The computational model created for the ANN method uses three basic layers: input, hidden, and output layers. The number of neurons, or in other words, the functional computational units interconnected in the hidden layers, varies depending on the number of data points and the complexity of the calculation model. The sensitivity of the method also varies depending on the number of neurons and the number of layers. Another important aspect is determining the transfer and activation functions used in the neurons functional calculations. While proven functions from the literature can be used, new functions can also be developed for efficient improvements in the method [

6].

Another optimization method, genetic algorithms, are mathematical models based on Darwin’s theory of evolution, which are built on the survival of the fittest. The philosophy of the model is designed to create a design community adapted by a certain population and then allow the adaptation to develop. In this context, we can describe the individuals within the populations that achieve the best results for the generated data. Genetic algorithms fundamentally produce possible solutions by mathematically modeling evolutionary processes such as selection and reproduction, parent characteristics, and genetic mutation. In the literature, genetic algorithms are especially used for the optimization of thermal power systems [

9].

In many optimization methods such as parametric optimization, some goals or other results may be sacrificed to achieve a desired result. One of the most important challenges in optimization problems is finding the desired data that should be simultaneously at its lowest and highest values. Genetic algorithms are an important tool in solving this optimization problem, particularly encountered in operational processes [

10]. Genetic algorithms primarily perform operations based on the fitness function. The fitness function is a mathematical tool that determines which individuals, in other words, which data, can survive. Thanks to the fitness function, which is the most important function of the genetic algorithm model, a precise and suitable model for the design can be created. The success of genetic algorithms is significantly related to the appropriate selection of the fitness function for the problem. Therefore, in the optimization of geothermal energy systems, the selection of the fitness function in the modeling of genetic algorithms determines the performance of the model [

11].

2. Cycles and Optimization Methods Used in Geothermal Power Plants

Geothermal power plants use thermal energy obtained by transporting geothermal fluid in liquid or gas phase from the Earth’s crust to the surface. This fluid is passed through a cycle to convert thermal energy into electrical energy, and then it is reinjected underground to complete the cycle. Geothermal power plants primarily consist of turbines, pumps, evaporators, and condensers [

12]. Geothermal energy systems can be classified into three main types based on their cycles: dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle plants. Additionally, theoretical models such as the Kalina cycle, which currently have limited application, are also studied in the literature. Maximizing the efficient use of geothermal resources with new technologies is a significant area of research [

13].

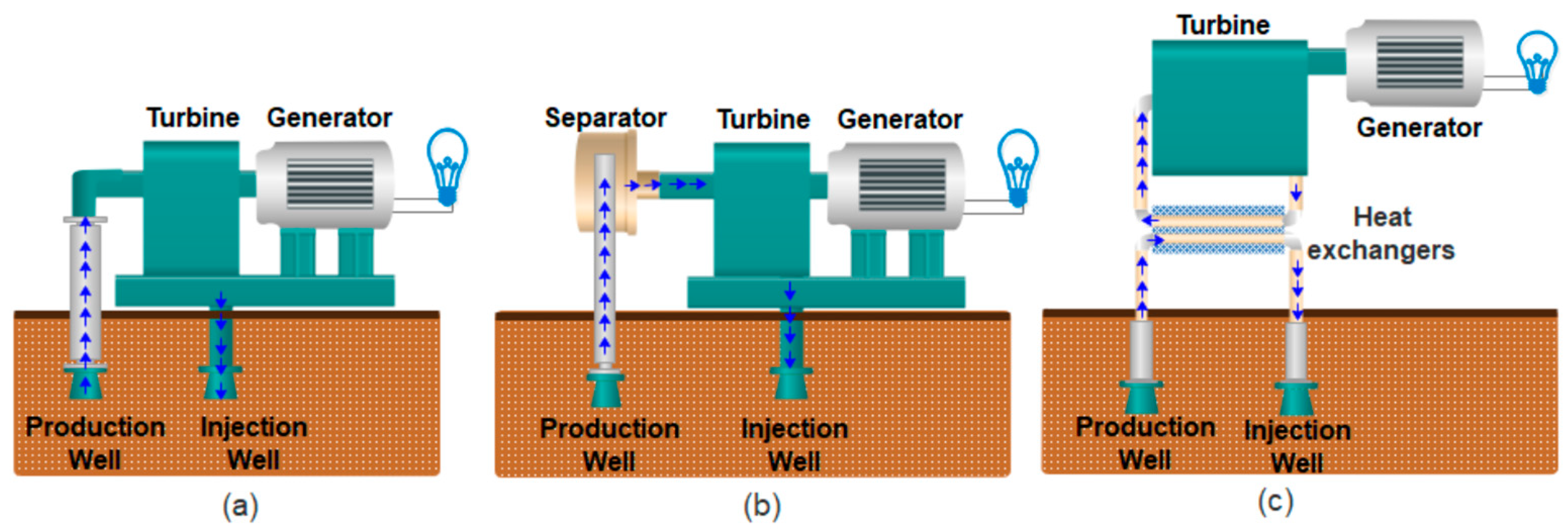

2.1. Dry Steam Cycle

Dry steam cycles generate electricity by directing steam obtained from steam-dominant geothermal sources directly to the turbine. This is the simplest type of geothermal power plant. The steam from the geothermal source drives the turbine to produce electricity and is then condensed and reinjected underground to complete the cycle [

13]. It is one of the oldest methods for geothermal power plants. There are two types: one without condensation, which is open to the atmosphere, and another that uses a cooling method to condense the steam. Plants without condensation are environmentally disadvantageous as the steam is released directly into the atmosphere, and their efficiency depends on atmospheric pressure. More environment friendly and efficient types have been developed using different condensation technologies [

14].

2.2. Single and Double Flash Steam Cycles

Geothermal resources are generally in liquid phase under high pressure and temperature beneath the Earth’s crust. As the geothermal fluid (brine) is brought to the surface through production wells, its pressure decreases and it vaporizes upon reaching the atmosphere. At this point, the fluid in a saturated liquid-vapor mixture is separated into liquid and vapor phases using a separator and sent to the plant through different pipelines. If sufficient steam flow and temperature are available, the vapor phase fluid is passed through a turbine to generate electricity. In single-flash plants, steam is separated in one step to produce electricity. However, for fluids with suitable thermophysical properties, a second separator can be used to obtain steam at lower pressure and temperature, which is then sent to the turbine in different stages to generate electricity. This allows for the design of plants that are approximately 20-25% more efficient than single-flash cycles. It is understood that double-flash plants will have higher initial investment costs due to the additional equipment. Therefore, cost analysis and investment return periods should be considered in plant design [

13].

2.3. Binary Cycle Systems

The characteristics of geothermal resources vary regionally. Binary cycle systems have been developed for electricity generation from low- and medium-temperature geothermal resources. In these geothermal fields, due to insufficient steam phase, the thermal energy of the geothermal fluid is transferred to a secondary fluid to generate electricity. These plants typically use organic fluids as the secondary fluid and operate in geothermal resources ranging from 85-170°C. The selection of the secondary fluid and the cooling method are crucial parameters affecting the plant’s efficiency. Additionally, proper design and operation parameters significantly impact the utilization of geothermal resources. [

13,

15].

Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram of dry steam, flash steam, and binary cycle geothermal power plants [

47].

2.4. Optimization Methods Used in Geothermal Power Plants

Optimization, by definition, can be described as the process of finding the best solution under certain conditions for one or more independent variables in the examined problem [

16]. Optimization methods can be classified in various ways. In the literature, they are categorized into seven types: artificial intelligence (heuristic), multi-objective approach, analytical method, iterative method, probabilistic approach, graphical structure method, and various computer software [

17]. Traditional optimization methods like analytical, iterative, probabilistic approaches, and graphical structure methods are not preferred due to slow convergence rates, long and laborious computation times, and the difficulty in accounting for dynamic changes in parameters [

18].

Different analytical methods can be used to overcome these problems. Recent studies frequently employ artificial neural networks and genetic algorithm optimization methods. Optimization methods, used individually or in combination, are important tools for modeling and analyzing geothermal systems. They allow for the examination and analysis of operating plants in a much shorter time and with dynamic interaction. Efficient operating parameters can be identified based on the analyses, allowing geothermal resources to be managed more consistently [

19].

Innovative optimization methods, such as the multi-objective approach, allow for comprehensive evaluation by considering multiple criteria like cost and energy efficiency. Although this enables optimization for multiple desired outcomes, it is a complex and time-consuming method due to its computational length and complexity. Small changes in parameter adjustments can significantly impact results [

20]. Analytical methods provide quicker results through simple applications but are generally more consistent for small-scale systems, limiting their use in complex systems like geothermal power plants [

21]. Iterative methods are essential for accuracy and consistency in optimization, repeatedly calculating to find the optimal solution of the objective function. Despite their high accuracy, iterative methods require significant processing power and time for large datasets and complex models and may necessitate additional analysis to avoid local optima, requiring more expertise and experience [

22,

23].

The probabilistic approach in the literature allows for comprehensive analysis by including possible outcomes rather than a single scenario, effectively examining resource variability and operational uncertainties. It is crucial for analyzing changes in operating conditions and optimizing performance in geothermal plants. However, the computational model can be complex and time-consuming, requiring substantial data and variations [

24,

25,

26]. The graphical structure method is important for quick evaluations by presenting data and analysis results graphically, making it easier to visualize complex data. However, detailed analysis of complex models on a graph can be challenging and may require more extensive work [

22]. The use of computer-aided design tools or software is also a common method, but it requires significant investment and continuous funding for updates, along with technical knowledge and experience [

27].

Heuristic approaches like genetic algorithms and artificial neural networks solve complex problems quickly and flexibly, searching a wide solution space for optimal results. These methods can be combined with other optimization techniques to form hybrid methods, providing more detailed analysis. They can quickly adapt to site variables in geothermal plants, examining specific conditions and offering various solutions. However, they require precise parameter tuning and significant datasets, which is common in most optimization methods. Recent research favors heuristic methods due to their ability to hybridize with other optimization methods, eliminating certain disadvantages, and producing faster, more consistent, and accurate results [

28,

29,

30].

3. Artificial Neural Networks and Genetic Algorithms

3.1. Artificial Neural Networks

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by the human brain. They can model the connections between inputs and outputs in a problem mathematically. The human brain establishes these connections through neurons, and ANNs have processing units similar to neurons. ANNs are massively parallel distributed processors made up of simple processing units that have a natural propensity for learning and using knowledge. They acquire knowledge through a learning process and store it as synaptic weights and biases, analogous to the brain’s structure [

31]. Regression and classification models with fixed basis functions have useful analytical and computational properties. However, for solving high-dimensional problems and applying complex models in practical applications, it is essential to adapt the basis functions significantly to the data. ANNs are one of the best applicable analytical methods in this context [

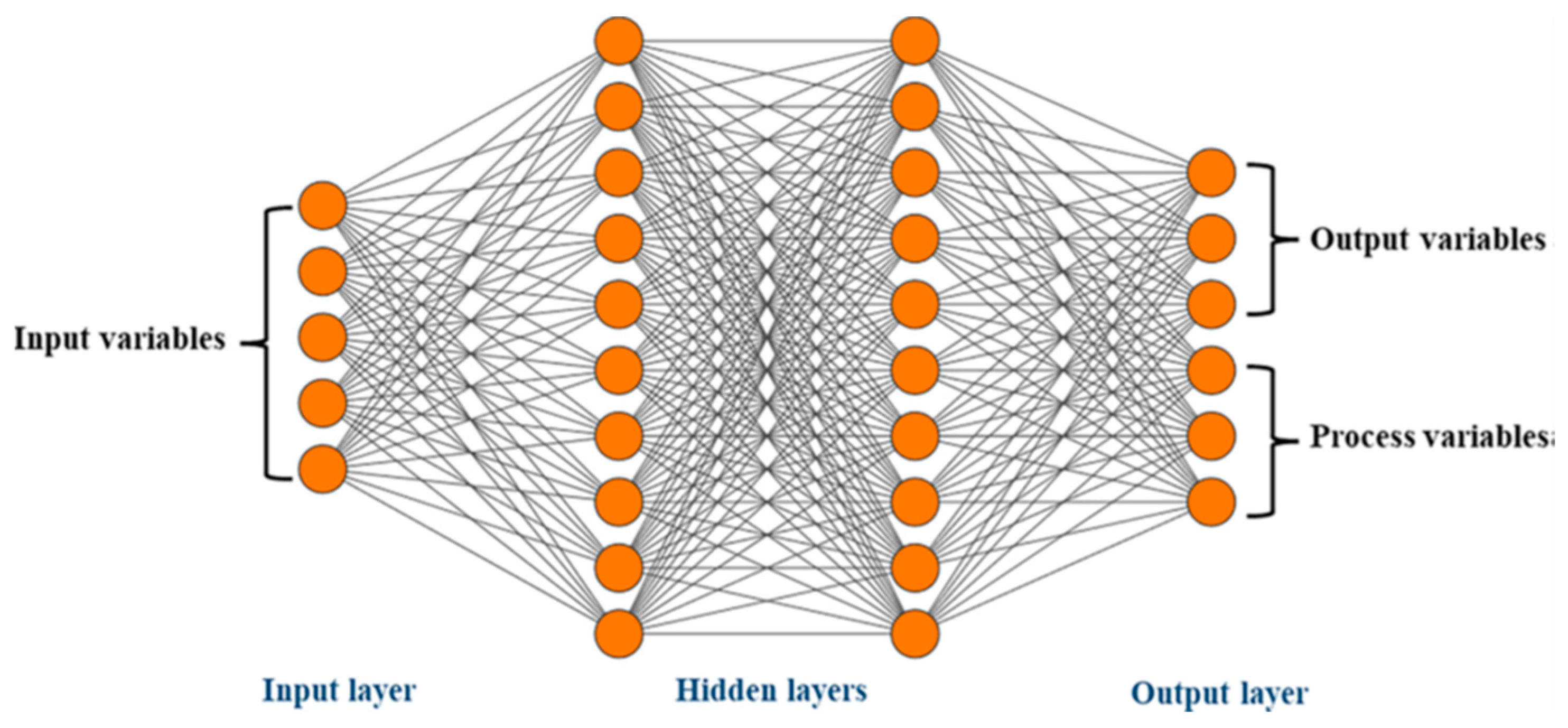

32]. ANNs typically consist of three layers: input, hidden, and output. The input layer contains the input data for the problem, the hidden layer(s) contain neurons that form the ANN model with one or more layers connected in parallel, and the output layer contains the desired output data [

6,

31].

Figure 2 shows the schematic model of an artificial neural network [

34].

As shown in the diagram, artificial neural networks (ANNs) can contain multiple hidden layers. Each neuron, or mathematical processing unit, in one layer is connected to neurons in the subsequent layer, forming a network. This structure allows for the development and analysis of the ANN model [

31,

32]. The mathematical modeling of neurons, the smallest unit in ANNs, was developed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957.

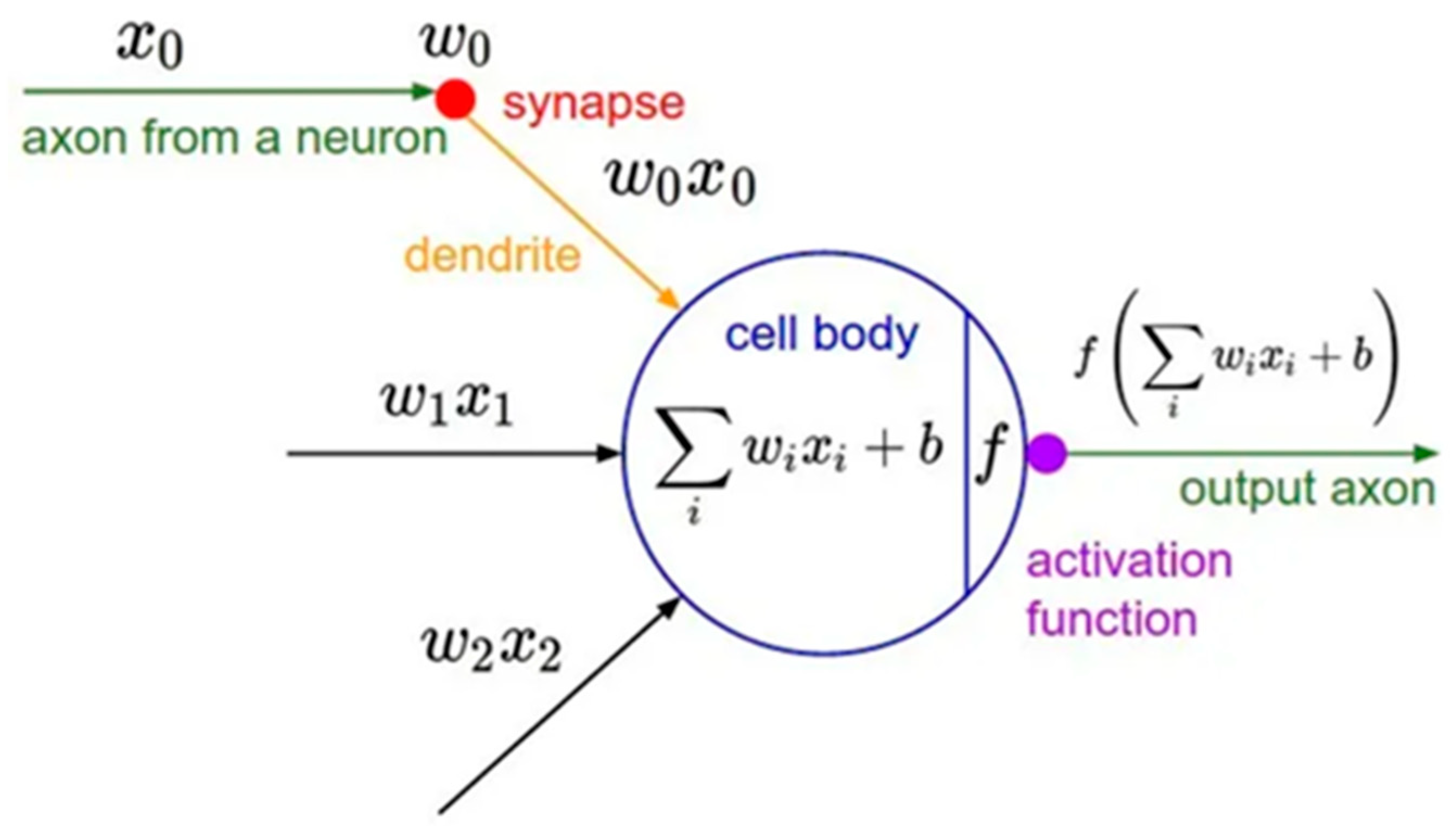

Figure 3 schematically shows the mathematical structure of a neuron [

35].

Neurons are represented using the following linear equation.

In the equation,

y is the dependent variable representing the output related to the input. The independent variable and input data are denoted by

x. The weight and bias are represented by

w and

b, respectively. The modeling of artificial neural networks is based on determining the weight and bias parameters to produce the best possible output. In other words, the effect of neurons on other neurons and the overall artificial neural network (ANN) architecture is calculated using these parameters. ANNs continuously update their weight and bias values to achieve the best results. At this stage, the optimal ANN function is determined as the loss function approaches zero [

31,

36]. Parameters such as the number of neurons, the number of layers, and the selection of the activation function significantly affect the performance of the output data. The initial determination of weight and bias values also influences model performance. Thus, the performance of an ANN is determined by the minimization of the loss function [

31,

33,

36].

ANNs reveal relationships in problems through deep learning. While many problems can be solved using fixed algorithms, complex problems requiring heuristic solutions, such as the optimization of geothermal power plants, are addressed by deep ANNs. Deep ANNs consist of multiple layers and thousands of neurons, depending on the problem. Significant amounts of data must be collected and processed for these models. The hardware’s memory capacity and processing time are critical based on data size and model complexity. Current hardware developments allow for analyses with these models beyond academia [

33,

37].To achieve desired results in ANNs, it is intended to restart and make changes based on a series of calculations. This involves re-determining weight values and continuing the model analysis forward. To do this, the derivative of all functions backward according to the chain rule must be taken. Iterations continue until the difference between the expected result and the actual result is minimized. Thus, the ANN model tries to calculate the relationships between inputs and outputs as desired [

33,

35,

36]. After creating the model, ANNs start the computation process to establish connections between data based on selected functions and parameter settings. Initially, determining weights and biases is necessary. Typically, weights are initialized as small random numbers, and biases are set to zero. Then, forward propagation is initiated. Each neuron receives an input signal

x, and a weighted sum is applied.

In a neuron, the above equation is input into a selected activation function, transforming the linear equation into a nonlinear one. This enables the model to handle more complex and real-world problems. Activation functions also constrain the neuron’s output within a specific range, preventing the emergence of excessively large or small weight values. Additionally, the activation functions used in backpropagation must be differentiable. Common activation functions in the literature include Sigmoid, ReLU, and Tanh. The results obtained from the output layer are compared with the desired results, typically using the mean squared error function to measure proximity to the target outcome.

Subsequently, backpropagation begins. The gradient descent algorithm is used to update weights and biases by calculating the gradient of all functions according to the chain rule. The forward and backward propagation processes continue until the loss function, or mean squared error, reaches a certain value. In the literature, this can also be done through a specific number of iterations. Artificial neural networks are an important and powerful tool for solving complex and difficult-to-understand problems [

31,

32,

33].

3.2. Genetic Algorithm

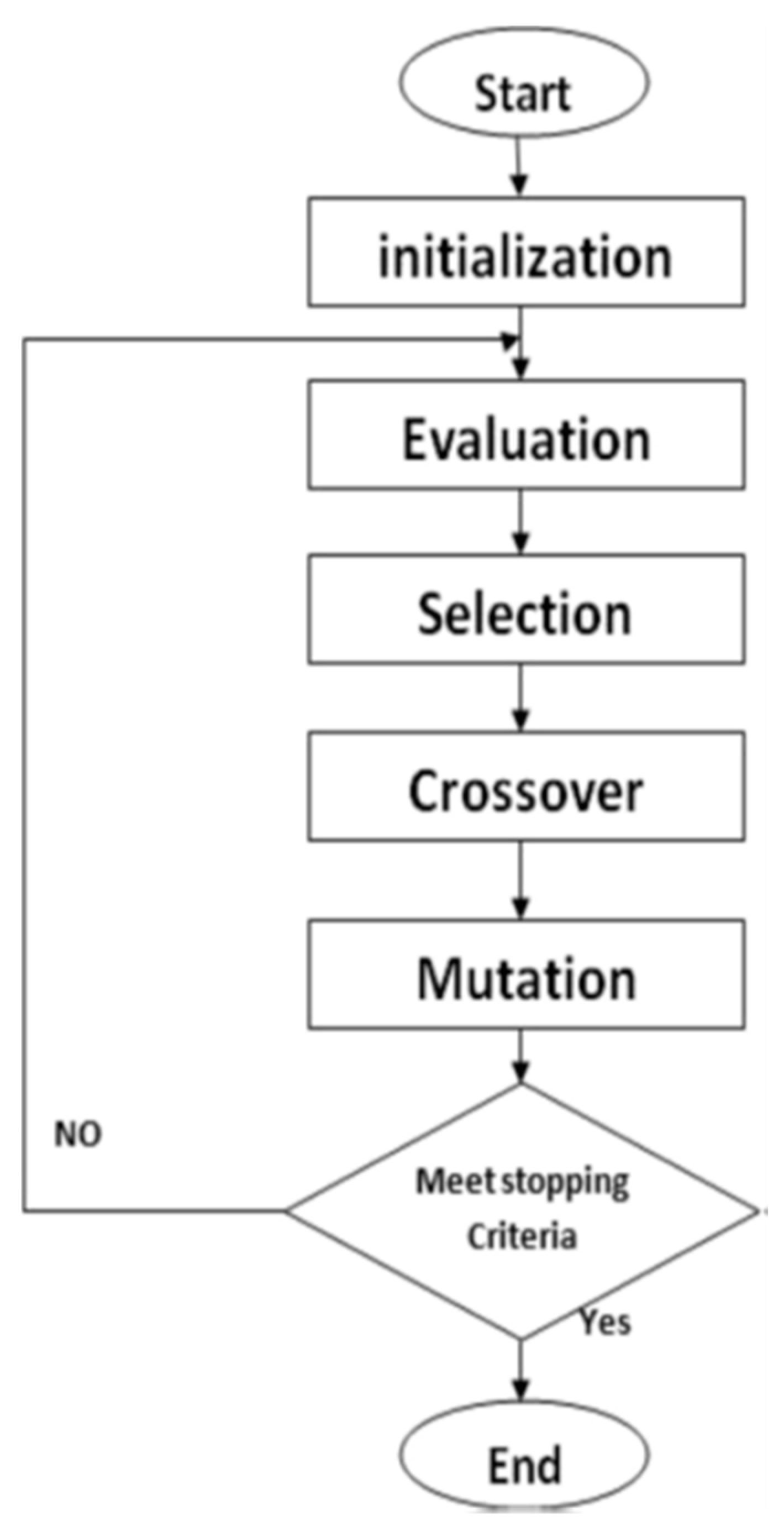

Genetic algorithms are algorithms used for optimization and data generation, utilizing mathematical models of natural selection, mutation, and evolutionary principles. They are crucial for solving complex and multidimensional problems [

38]. Instead of a single solution, genetic algorithms can create a set of potential solutions. These potential solutions can then be analyzed for their suitability to the desired outcomes. The success of genetic algorithms largely depends on how potential solutions (individuals) are defined and the choice of the fitness function. For example, in geothermal power plants, individuals can be defined by operating parameters and represented as vectors. The genetic algorithm methodology is then applied to these vectors to produce results [

39,

40,

41].

In genetic algorithms, mechanisms that ensure genetic diversity, such as crossover and mutation, must be mathematically determined. Different potential solutions are generated through crossover and mutation. The algorithm concludes once fitness values reach a certain level or after a specified number of iterations [

40,

41]. One significant advantage of genetic algorithms is their ability to find global optimum solutions rather than local maxima and minima [

39]. The general diagram of a genetic algorithm is shown in

Figure 4 [

42].

There is no single standard model for genetic algorithms; they can be selected or designed to be problem-specific or for general applications. Genetic algorithms can generate desired outcomes and create a model to determine the most suitable one. This makes them applicable for optimization problems requiring the analysis of multiple parameters, such as geothermal power plants [

43].

Genetic algorithms are used in the literature for optimizing geothermal power plants. Different studies show variations in the parameters of genetic algorithms based on the geothermal system being analyzed and the available data set. Results indicate that operating conditions for geothermal power plants are determined and optimized. For example, Farjollahi et al. identified operational parameters for the lowest operating costs and high thermal efficiency using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithms. The combination of genetic algorithms and neural networks with other optimization methods is common in the literature [

44].

In the optimization of geothermal plants, genetic algorithms can model the characteristics of the expected fluid from the geothermal source. This modeling aims for high energy efficiency and low entropy production as the objective function. Subsequently, the geothermal plant is analyzed based on flow rate, well depth, and well temperature as inputs, with thermal efficiency and net power outputs being maximized [

45]. Using genetic algorithms to generate potential solution sets for complex issues like geothermal resource management, power plant design, and optimization is significant for engineering studies. It is also a comprehensive method for modeling geothermal production wells as used in the literature [

46].

4. Optimization of Geothermal Power Plants Using Genetic Algorithms and Artificial Neural Networks

Optimizing geothermal energy systems is inherently a complex and multidimensional problem due to the nature of geothermal fields and system design. Each component of geothermal energy systems requires configuration solutions that designers must address. These configurations are primarily made by identifying system parameters. The optimization of design and operational parameters in complex systems like geothermal energy systems is a multidimensional problem. Safety, environmental factors, efficiency, and cost calculations are essential in the design of plant equipment. Furthermore, determining the optimum operating conditions of the plant is necessary for detailed calculations. However, designing equipment for a plant operating under optimal conditions can be expensive. Optimization requires working with numerous parameters to achieve the best results. The biggest challenge in optimizing geothermal energy systems is the continuous variation of parameters until optimal values necessary for system design are reached. For each altered parameter, lengthy and exhaustive calculations, such as thermodynamic analyses and equipment design analyses, must be performed. Unlike deterministic approaches, optimization studies using genetic algorithms and artificial neural networks can quickly and reliably reach the best results by selecting the best solutions from potential solution sets [

38,

48]. These algorithms can also create models that account for the variability of geothermal resources and operational periods, allowing for more efficient use of geothermal resources [

46].

Innovative optimization approaches are modeled in the literature using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithms, either alone or in combination. This allows for faster, more reliable dynamic data analysis, particularly of operational parameters [

34,

37,

48]. Today, artificial neural networks, genetic algorithms, deep neural networks, machine learning, and their subfields are used alone or together as alternatives to traditional methods in various fields. In their study, Özkaraca et al. modeled the Sinem Geothermal Power Plant using the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) neural network. The exergy efficiency was set as the objective function to be maximized. The artificial neural network algorithm was inspired by the foraging behavior of bee colonies. Data were modeled using nonlinear computations starting from the initial data. By conducting classical and advanced exergy analyses and comparing them with the results of the ABC method, exergy efficiencies were found to be 39.1%, 43.1%, and 42.8%, respectively. The results of the advanced exergy and ABC neural network model were very close, showing that applying the optimal operating conditions obtained from this model in the plant could yield an exergy gain of 2102 kW [

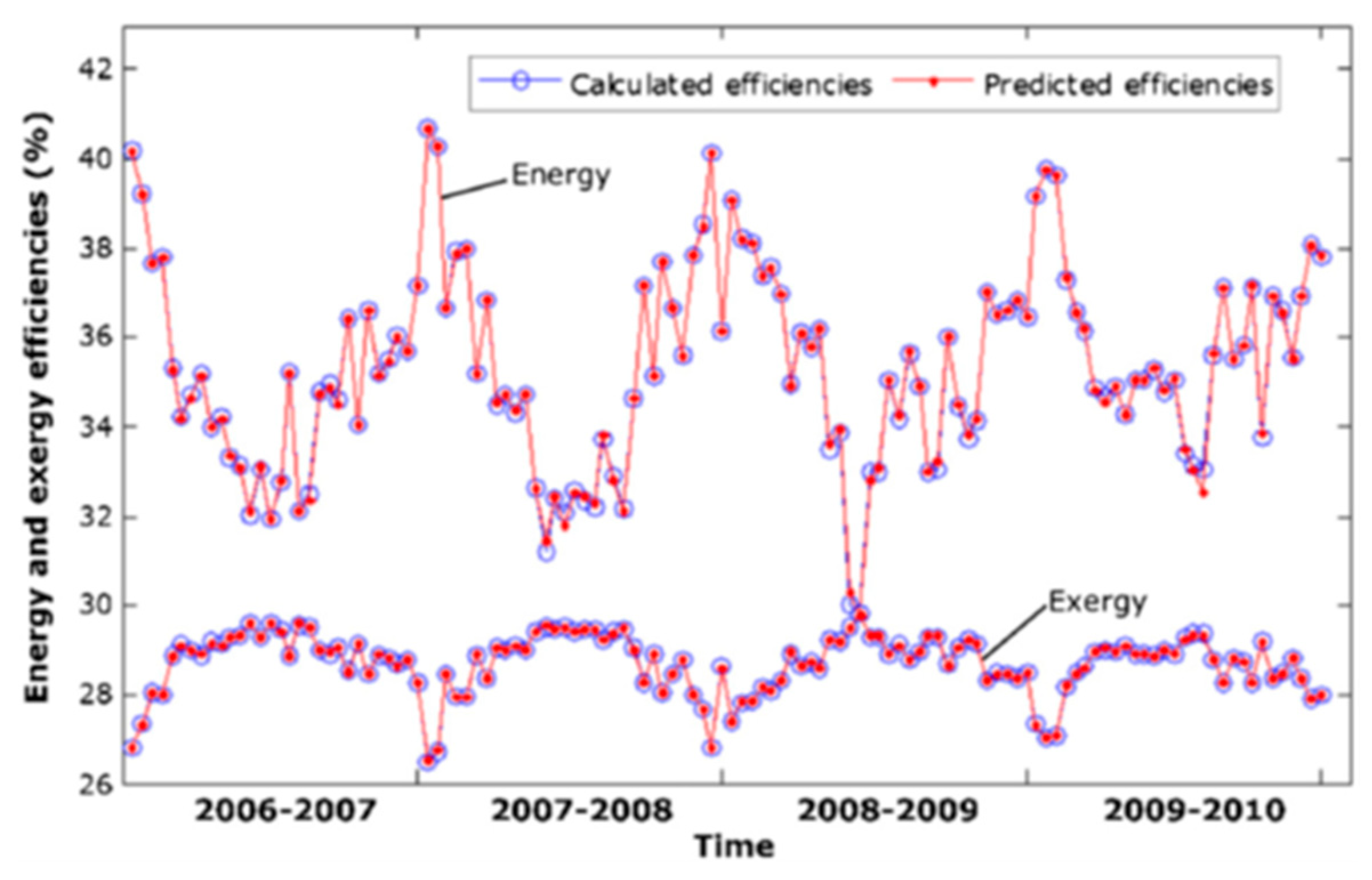

50]. The Afyonkarahisar geothermal district heating system was modeled using neural network tools available in MATLAB by Keçebaş et al. Thermodynamic analysis results were compared with the neural network results, and energy efficiencies were found to be 35.38% and 35.39%, respectively.

The analysis results indicate that artificial neural networks (ANNs) can also be used to monitor system performance.

Figure 5 compares findings from ANNs with actual data, demonstrating the consistency of ANN models in system modeling [

6]. In addition to ANNs, genetic algorithms (GAs) are preferred for their ability to generate potential solution sets for complex problems. He et al. used a GA in their study, where the fitness function, determining the survival of individuals (solution sets), was selected as the ratio of input heat to the work obtained. This function aimed to ensure the survival of individuals that enhance efficiency, resulting in a 16.18% increase in energy efficiency. GAs offer a different approach to geothermal plant optimization compared to traditional methods [

50]. The fitness function is a crucial detail in GA modeling and can be defined using thermodynamic relations, various functions from the literature, or a newly developed function. It can also be written in vector form if one or more parameters are used [

51]. GAs operate for a specified number of iterations to produce solution sets, which can vary by problem. Rudiyanto et al. found that general exergy efficiencies stabilized at 20, 50, and 100 iterations, allowing for shorter computation times without needing further iterations [

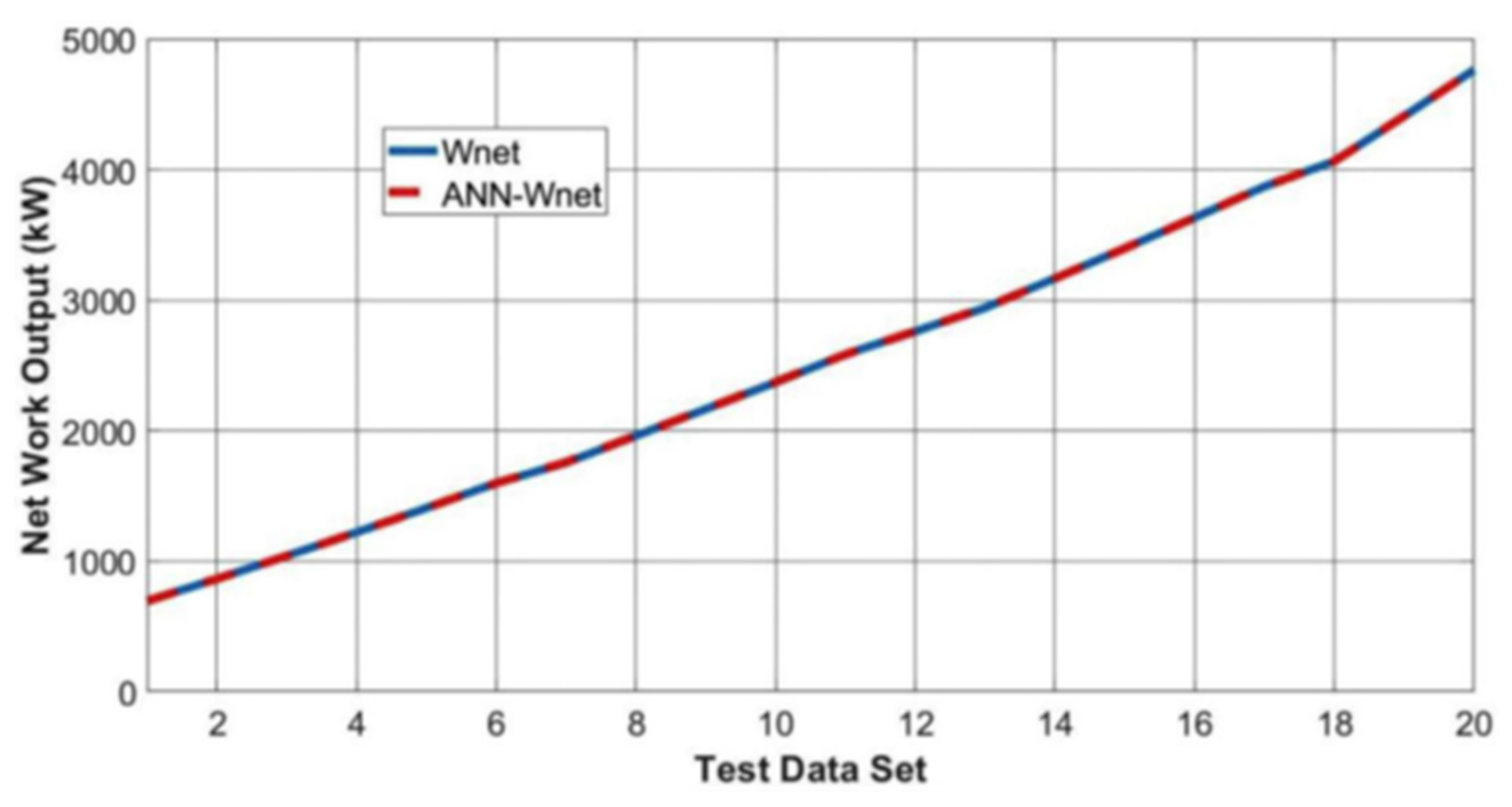

28]. Yılmaz et al. analyzed a complex hybrid geothermal and solar energy system using both GAs and ANNs.

Figure 6 shows the net power output from actual data compared to the computation model.

The hybrid computational model developed using artificial neural networks (ANNs) and genetic algorithms (GAs) demonstrates applicability by accurately predicting real data [

43]. GAs can test various operational parameters in geothermal power plant optimization, identifying the best one. Traditional methods like analytical and iterative approaches have slow convergence rates and struggle with dynamic parameter changes, leading researchers to prefer heuristic methods for their speed and consistency. ANNs and GAs, either together or separately, are crucial tools for optimizing geothermal power plants [

18].

5. Materials and Methods

A calculation method has been developed using real-time data obtained from a geothermal power plant located in the Seferihisar region of Izmir, Turkey. Initially, a thermodynamic analysis of the plant’s design and operational parameters was conducted. Subsequently, the operational parameters obtained from the developed method were compared with the actual plant data to investigate the consistency of the method. Finally, the potential optimal operating parameters were derived from the calculation method and presented. Certain assumptions were made for the thermodynamic analyses, which are listed below:

All processes are in thermodynamic equilibrium.

Differences in kinetic and potential energy are negligible.

Heat transfer to the environment from all equipment is negligible.

Air is assumed to be an ideal gas.

Cycles are considered to have balanced and steady flows.

The amount of NCG (non-condensable gases) is negligible.

It is assumed that all steam entering the plant condenses upon exiting.

For exergy analyses, the annual average temperature of the region is taken as the dead state. According to meteorological data, this value is 17°C. Additionally, the dead state pressure is taken as the ambient pressure, which is 1 bar.

Brine values are taken as water values.

The mechanical efficiency of the turbine is assumed to be 99%.

The mechanical efficiencies of the pump and fan are assumed to be 95%.

The turbine exit pressure is assumed to be 0.2 bar higher than the condenser pressure.

The Refprop program was used for the properties of the geothermal fluid and the secondary fluid in the thermodynamic analyses. The following thermodynamic formulas were used for the energy and exergy analyses.

A computational model within the scope of this research was developed using the Python programming language, version 2.14.0, via Google Colab. The aim was to create an innovative analysis method using a genetic algorithm optimization method that employs deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function. Numerous libraries were utilized within the Python program. Particularly, the TensorFlow and Keras libraries, which are frequently used in the literature for artificial neural networks and genetic algorithms, were also employed in this study. Additionally, the Pandas, NumPy, and Matplotlib libraries were preferred to facilitate mathematical operations and data analyses within the model. The method developed for the optimization of the geothermal power plant requires data recorded by the plant’s SCADA system. The inputs and outputs of the method were generated using data obtained from this source. By optimizing the wells and the turbine, where power generation occurs, based on the available data, the operational conditions can be determined. Consequently, a comparative thermodynamic analysis can be conducted with the obtained values, allowing for a reorganization of the plant’s operations to achieve efficient performance.

In March 2022, a confidentiality agreement was signed with the management of an operational geothermal power plant located in the Izmir province for use within the scope of this research. According to this agreement, the plant data were agreed to be used for the development of the calculation method and for the publication of analyses academically, while keeping the company name confidential. The geothermal power plant is designed to produce a gross power output of 12.24 MWe. N-butane was chosen as the secondary fluid. The plant uses Exergy brand turbines and has a dual-pressure staged heat exchanger and turbine design. The condensation system is designed to be air-cooled.

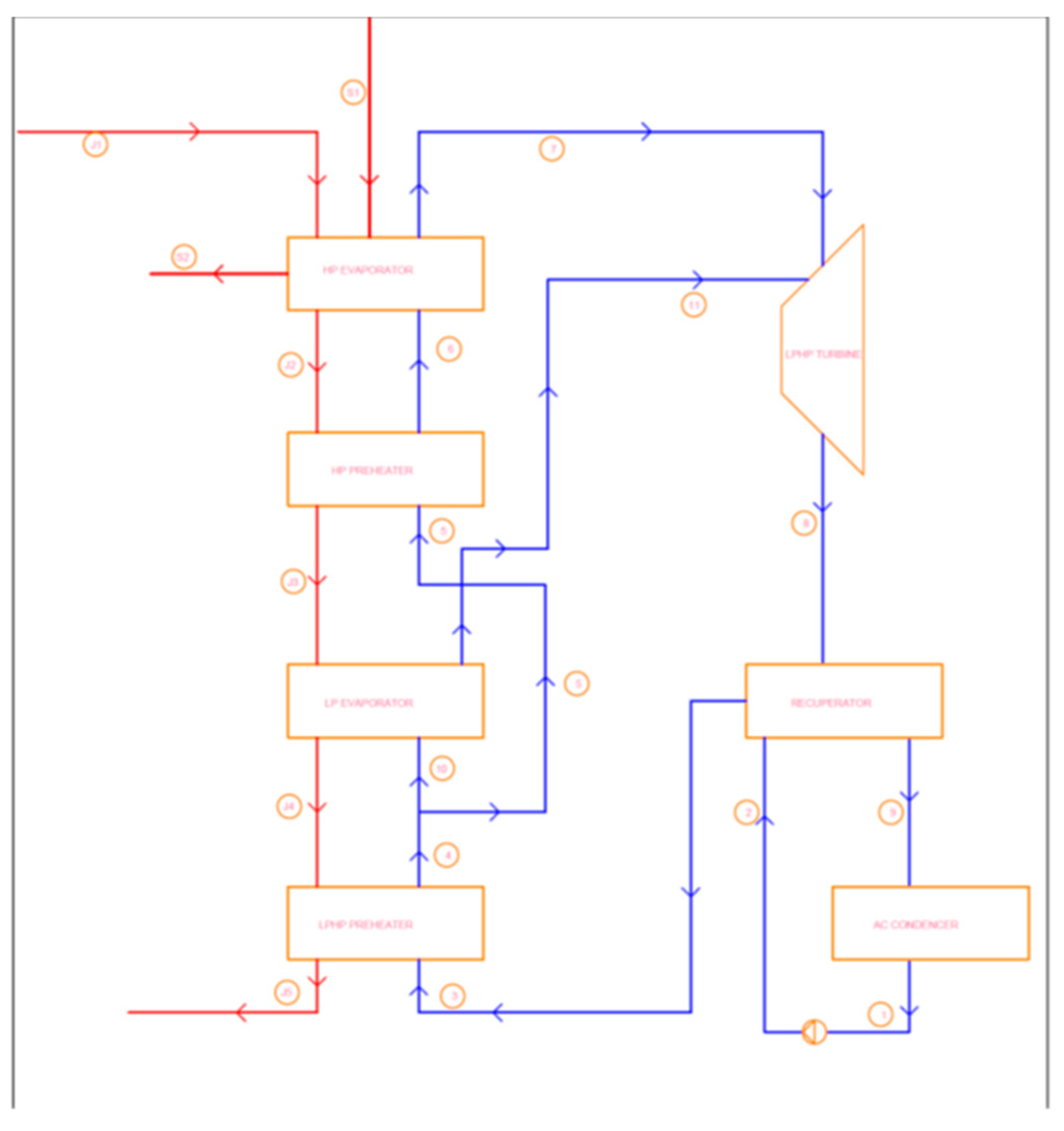

Understanding the design operation of the geothermal power plant allows the researcher to comparatively interpret the analysis results. In this plant, the liquid phase (brine) and the vapor phase of the geothermal fluid enter the high-pressure (HP) evaporator, which has different pipelines and heat exchanger surfaces. The steam separates from the HP evaporator and is transferred to a condensation tank before being sent to reinjection wells. Subsequently, the brine exiting the HP evaporator enters the HP preheater. In the dual-pressure staged plant, the brine transfers some thermal energy to the low-pressure (LP) evaporator after exiting the HP evaporator. At the point where the organic fluid section of the plant has not yet split into HP or LP, the brine proceeds to two preheater exchangers and finally exits the plant to be pumped underground via reinjection wells. In the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC), the n-butane working fluid pressurized by feed pumps first receives some thermal energy from the recuperator and then enters two preheaters. Then, using an actuator-controlled valve, it is divided into HP and LP stages; a portion enters the LP evaporator and expands as superheated vapor in the LP section of the turbine. The working fluid going to the HP section passes through the HP preheater and evaporator before expanding in the HP section of the turbine. The fluids from both pressure stages exit the turbine at the same temperature and pressure and transition to the liquid phase in the air-cooled condenser, completing the cycle. The specially designed turbine integrates high and low-pressure stages into a single turbine, aiming to produce more energy with lower investment and operating costs. The heat and mass diagram using the design values of the plant is shown in

Figure 7. In the diagram, the states represented by J, S, and numbers correspond to the states of brine, steam, and butane working fluid, respectively. Thermodynamic analyses were performed using SCADA screen images taken from the plant on 11.06.2024 at 15:30, along with all data obtained from manual indicators installed during the plant’s setup, which could not be obtained electronically.

The artificial neural network model used in the calculation method is a multilayer deep artificial neural network. The architecture of the model comprises a total of 8 layers: 1 input layer, 6 hidden layers, and 1 output layer. The input layer consists of 38 neurons, which correspond to the number of input data. Similarly, the output layer contains a total of 2 neurons representing the objective functions of the deep artificial neural network: gross power generation and net power consumption. The hidden layers collectively contain 2464 neurons. Each layer in the artificial neural network model has defined functions and properties, including activation functions, regularizers, and dropout codes. The activation function allows the multilayer deep artificial neural network to form meaningful correlations from the data and produce the desired function. In this study, the ReLU (rectified linear unit) function was used. The sigmoid function was used in the output layer to allow negative values as output.

In the model, the coefficients in the smallest unit of the neural cell, referred to as weights, are readjusted after a certain calculation cycle to ensure that the model predicts the outputs in the best possible way. The mechanism for rechecking during these specific calculation cycles is defined by the ‘batch_size’ command in the model. In this study, the batch_size value was set to 32.

In general, the basis of learning is performed using predetermined numbers and formulas through an algorithm. The deep artificial neural network model is automatically implemented using the TensorFlow coding available within the Python programming language’s library. To facilitate learning and the testing of learned values with the specified parameters and algorithms, it is necessary to determine what portion of the plant data will be used separately for learning and testing. In the literature, it is typically common to use 80% of the data for learning and 20% for testing. Researchers can determine different ratios specific to their studies.

By modeling the deep artificial neural network, a function that can establish correlations between inputs and outputs using the data obtained from the plant is obtained. This function can then be used as the fitness function in the genetic algorithm. Through this method, it is aimed to develop a more consistent and innovative calculation method by using the plant’s own operational data for the fitness function, which is the most important function of the genetic algorithm.

In the genetic algorithm, each piece of data is referred to as a gene, and the rows are referred to as individuals. These individuals, or data rows, represent the operating conditions. By using the generated data, a mathematical algorithm model is created to predict the plant’s working conditions and optimal operating parameters. In the genetic algorithm, which is the fundamental working method of the calculation model, the generated individuals are evaluated through the fitness function to obtain a fitness value. As mentioned earlier, these fitness values are determined using the function created by the deep artificial neural network trained with actual data. The fitness function is critically important for the consistent formation of individuals. The higher the fitness value an individual obtains, the greater its chance of survival and passing on to subsequent generations. This process is repeated until the data to be optimized reaches the best possible outcome.

Another important aspect to determine is the mathematical modeling of survival threshold, mutation probability threshold, and crossing over tools used in the genetic algorithm, due to its inherent nature. Each tool is modeled by adding factors with Gaussian distribution to increase randomness. The aim here is to reach data that can create different conditions and to develop a model that can analyze the best possible outcome. In the literature, different values are found for these tools. Although there is no optimal value, the coding language within the Python program is used for crossing over.

Subsequently, a random multiplier is assigned to each value within the obtained individuals, i.e., rows, by examining them one by one. This randomness is determined using the Gaussian distribution method. If the new value obtained with the assigned multiplier is greater than the mutation probability, it is modified by multiplying it with another mutation multiplier determined by the Gaussian distribution, meaning the genes undergo mutation. There is no optimal value for determining mutation probability in the literature. Therefore, through empirical methods, the best results in this study were achieved with a value of 0.95. In other words, if the number obtained from the above process is greater than 0.95, it will undergo mutation. In the genetic algorithm, physical limits are applied to mutation and survival thresholds to prevent outcomes that are impossible to implement but thermodynamically feasible.

Different values for the survival threshold are used in the literature. Since there is no optimal value, the researcher determined this value through empirical methods. In this study, a value of 0.85 was found to be optimal. A very high survival threshold prevents the formation of new variations by causing most individuals to die. Conversely, a very low threshold results in the production of individuals that are very similar to previous ones, reducing diversity and hindering optimization. All values were determined empirically based on the data obtained from the plant and the duration of the research. It should be noted that these values may vary depending on the data and fieldwork conducted by the researchers.

At the end of all these processes, the best individuals, or in other words, the data in the rows, are printed and organized. The optimal results from the selected rows are then evaluated by the researcher. All the results analyzed by the model are exported as an Excel file. Subsequently, the researcher will examine the data with the best net power outputs to find the optimal result and verify the accuracy of the results using thermodynamic calculation methods.

A genetic algorithm optimization method using deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function has been developed as an innovative calculation method. This method aims to identify the optimal operating conditions for geothermal power plants in operation. Additionally, it allows for the rapid and accurate calculation of the plant’s optimal working parameters, taking into account changes in external conditions and geothermal fluids throughout the year, thus significantly reducing the time and effort required for extensive and exhaustive engineering studies.

6. Results

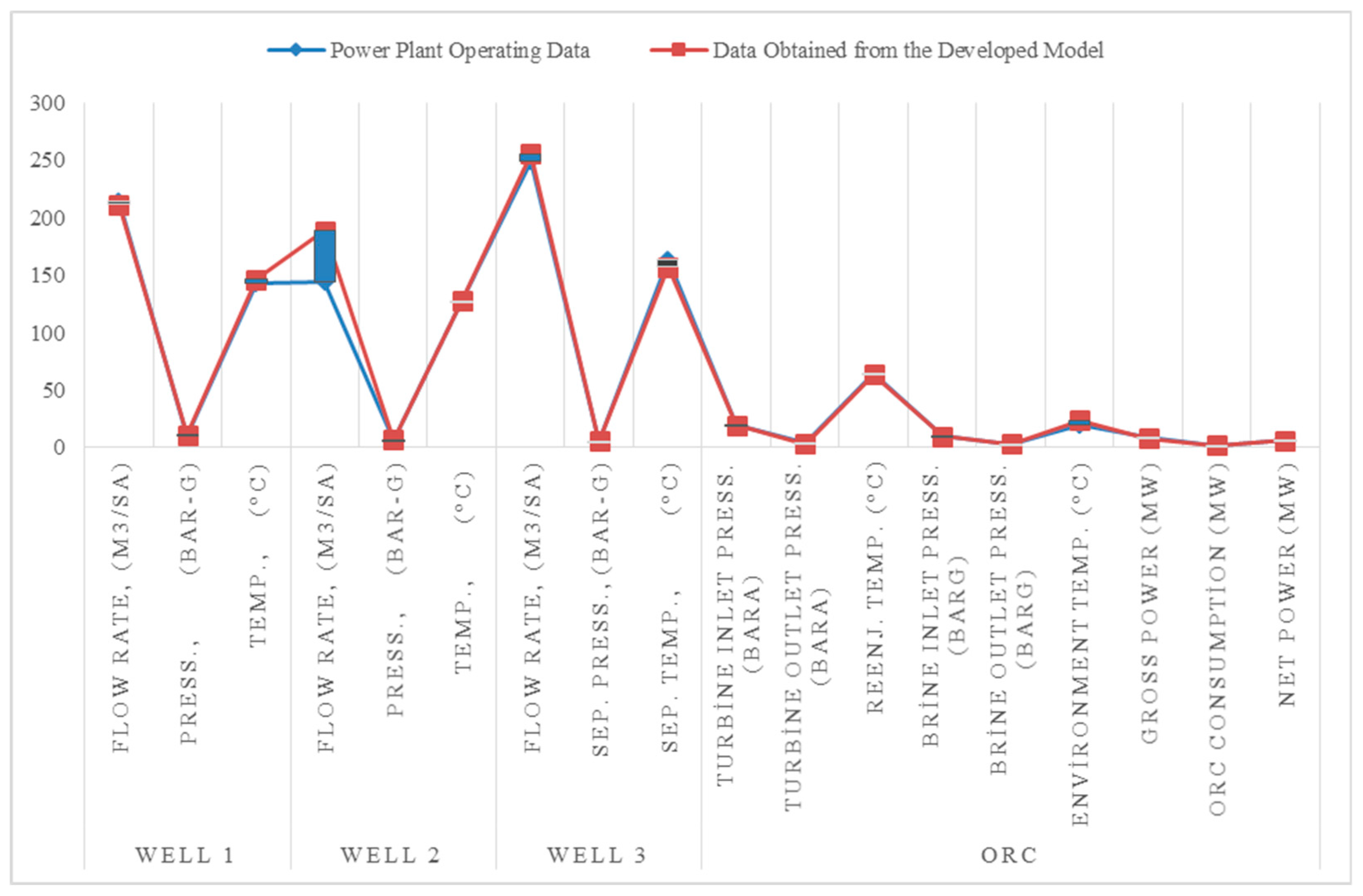

Analyses were conducted using a genetic algorithm that employs deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function to model an operational geothermal power plant and determine its optimal operating conditions. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether geothermal power plants can be modeled and their optimal operating conditions predicted using a genetic algorithm with deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function. According to the analysis results, data generated very close to the plant’s actual data could be repeatedly obtained.

Figure 8 presents a comparative graph of the data obtained from the plant and the data derived from the calculation method. This graph demonstrates that the plant calculation method was modeled with minimal error, closely matching the operational data.

A large number of models representing the operational periods of the plant, similar to

Figure 7, could be produced from the data obtained through the calculation method. It is understood that the innovative calculation method can dynamically model the plant’s different operating conditions and produce results with very low error rates. In this context, analyses can be performed using data from different geothermal plants with the applied method. By adjusting the number of inputs and outputs in the data definition section of the developed method, geothermal power plants can be modeled and optimization studies can be conducted. The thermodynamic properties of the design parameters of the examined plant are shown in

Table 1.

The design parameters are important for indicating the physical limits of the plant. In this context,

Table 2 presents the energy and exergy analyses of all equipment based on the plant’s design parameters.

To interpret the thermodynamic analyses of operational parameters and optimal conditions, the results of the analysis conducted with the plant’s design parameters should be compared. This comparison allows for the investigation of whether the theoretically obtained optimization results are feasible.

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the thermodynamic properties and analysis results of the operational parameters.

According to the thermodynamic analysis of the operational parameters, the net exergy and energy efficiencies of the plant are significantly lower than the design values. It is observed that the operational conditions differ from the design parameters, particularly with the flow rates of brine and steam being significantly lower than the design values. Therefore, a loss of efficiency in the plant is expected. However, when the ORC equipment is analyzed in more detail according to the operational parameters, it is found that the exergy efficiency of the high-pressure preheater is particularly low. Additionally, the low-pressure turbine operates with a lower than expected exergy efficiency. The high-pressure preheater, which operates at an exergy efficiency of 93.24% according to the design parameters, has dropped to 57.85% under operational conditions. Moreover, it is observed that approximately 22% of the butane fluid evaporates before entering the high-pressure evaporator according to the operational parameters. As a result, the heat transfer is not distributed as desired, leading to exergy losses.

While the plant operates under similar conditions, more optimal operating parameters can be established by making changes in the flow rate, pressure, and temperature on the butane side. At this stage, the optimal data obtained from the calculation method using deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function were selected by the researcher and analyzed by establishing thermodynamic equilibrium under the same external and geothermal fluid conditions. In this way, significant increases in exergy and energy efficiency were achieved in the plant. The thermodynamic properties and analysis results of the obtained optimal operating conditions are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

The developed calculation method optimized the operating conditions under the same environmental conditions. As a result of the analyses, the net power produced by the plant increased from 3,748 kW to 5,225 kW. Under optimal operating conditions, the reinjection temperature was reduced from 72.6°C to 70.33°C, allowing for greater energy and exergy input. Additionally, the flow rate and pressure of butane were increased to make the system more efficient. Due to these increases, the internal consumption of the ORC also increased. However, the amount of increase in gross energy obtained was much greater than the increase in internal consumption. This resulted in a net power increase of 1,477 kW. Under optimal operating conditions, the temperatures and pressures at the equipment’s inlet and outlet were balanced, reducing thermal stresses during operation. Simultaneously, the exergy destruction in the equipment was significantly reduced. Specifically, the exergy efficiency of the high-pressure preheater increased from 57.85% to 89.82%. The exergy efficiencies of all equipment improved after optimization. Consequently, the overall plant exergy and energy efficiencies became 34.62% and 8.62%, respectively. The gross power increase was 34%, while the increase in internal consumption was 17%. When comparing the design parameters with the optimal operating conditions, the equipment’s exergy efficiencies were found to be close to the design values.

This ensured that the operation was optimized within the design limits. The optimal operating conditions were established using the data obtained from the developed calculation method. A thermodynamic balance was established, and a comparison with the design parameters showed a net power increase of 39.41%. By integrating the calculation method with the SCADA algorithm that controls the plant’s operation, continuous thermodynamic monitoring of the plant can be achieved. This enables the creation of more efficient operating conditions that can quickly adapt to changes in environmental conditions and geothermal fluid. In addition to modeling renewable energy sources, the developed calculation method identified more optimal operating conditions under the same environmental conditions.

7. Discussion

In this study, methods used in optimizing geothermal power plants were examined. The use of heuristic approaches in optimization methods was discussed with examples from the literature. The challenges of optimizing geothermal power plants and the application of artificial neural networks (ANNs) and genetic algorithms (GAs) were explained. The modeling, structure, and process steps of ANNs and GAs were described. Optimizing geothermal power plants is a complex, multidimensional problem requiring extensive computations and analysis of dynamic variables encountered during operation. The advantages and disadvantages of traditional methods were discussed, and the reasons for using heuristic methods were explored. An innovative optimization method has been developed using a genetic algorithm with deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function. The modeling and optimization of an ORC geothermal power plant, from which operational data were obtained, have been conducted and the findings have been presented. Some findings from the research are summarized below:

Traditional methods are limited in optimizing geothermal power plants due to difficulty in data analysis and slow response to dynamic data.

Heuristic methods such as ANNs and GAs can create more effective optimization models, either separately or together.

Innovative heuristic methods still rely on linear functions and regression analyses used in traditional methods.

Models can be customized for different plants and problems, creating problem-specific algorithms.

Heuristic methods can predict geothermal plant performance accurately, enabling dynamic monitoring and optimization.

Modeling geothermal resources and wells with heuristic methods can develop plant operation strategies.

GAs can work with large parametric data sets, creating potential solution sets and analyzing the most efficient operational parameters.

Hybrid models developed using heuristic methods can produce fast, reliable, and consistent results for more complex problems.

An innovative optimization method using a genetic algorithm with deep artificial neural networks as the fitness function has been developed.

With the optimal operating conditions obtained through the developed innovative calculation method, a net power increase of 1,477 kW was achieved. This resulted in a net power increase of 39.41% for the examined geothermal plant.

By optimizing the operating conditions with the calculation method, the reinjection temperature was reduced to 70.33°C, close to the design value, allowing for greater energy and exergy input to the plant.

The exergy efficiencies of the equipment operating with low exergy efficiency under operational conditions were increased after optimization, resulting in overall plant exergy and energy efficiencies of 34.62% and 8.62%, respectively.

As a result of the optimization, more efficient and balanced operating parameters were calculated under similar external and geothermal fluid conditions.

Non-traditional methods can model and optimize geothermal energy systems based on operational parameters. Using hybrid analysis methods created with a more innovative approach in future research can provide faster and more reliable engineering solutions for the design and operation of geothermal plants. The use of heuristic methods is likely to increase in the optimization of geothermal power plants, as in many other fields. Combining different methods can yield better and more consistent optimal analysis results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ö.Ö. and H.K.Ö.; methodology, Ö.Ö.; software, Ö.Ö.; validation, Ö.Ö.; formal analysis, Ö.Ö.; writing—original draft preparation, Ö.Ö.; writing—review and editing, H.K.Ö.; supervision, H.K.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- R. Loni, O. Mahian, G. Najafi, A. Z. Sahin, F. Rajaee, A. Kasaeian, M. Mehrpooya, E. Bellos, W. G. le Roux, A critical review of power generation using geothermal-driven organic Rankine cycle, Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 25 (2021) 101028. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Barasa Kabeyi, O. A. Olanrewaju, Geothermal wellhead technology power plants in grid electricity generation: A review, Energy Strategy Reviews 39 (2022) 100735. [CrossRef]

- E. T. Karagöl, İ. Kavaz, Dünyada Ve Türkiyede Yenilenebilir Enerji, Siyaset, Analiz 197 (2017) 1-32.

- H. D. M. Hettiarachchi, M. Golubovic, W. M. Worek, Y. Ikegami, Optimum design criteria for an Organic Rankine cycle using lowtemperature geothermal heat sources, Energy 32 (2007) 1698-1706. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, F. Witte, I. Tuschy, O. Kolditz, H. Shao, Parametric optimization and comparative study of an organic Rankine cycle power plant for two-phase geothermal sources, Energy 252 (2022) 123910. [CrossRef]

- C. Yılmaz, I. Koyuncu, Thermoeconomic modeling and artificial neural network optimization of Afyon geothermal power plant, Renewable Energy 163 (2021) 1166-1181. [CrossRef]

- A. Keçebaş, I. Yabanova, Thermal monitoring and optimization of geothermal district heating systems using artificial neural network: A case stud, Energy and Buildings 50 (2012) 339-346. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Khalil, A. M Barhoom, B. S. Abu-Nasser, M. M. Musleh, S. S. Abu-Naser, Energy Efficiency Predicting using Artificial Neural Network, International Journal of Academic Pedagogical Research 3 9 (2019) 1-1.

- J. Clarke, L. McLay, J. T. McLeskey, Comparison of genetic algorithm to particle swarm for constrained simulation-based optimization of a geothermal power plant”, Advanced Engineering Informatics, 28 1 (2014) 81-90. [CrossRef]

- A. Behzadi, E. Gholamian, P. Ahmadi, A. Habibollahzade, M. Ashjaee, Energy, exergy and exergoeconomic (3E) analyses and multi-objective optimization of a solar and geothermal based integrated energy syste, Applied Thermal Engineering 143 (2018) 1011-1022. [CrossRef]

- T. V. Avdeenko, Serdyukov, K. E. Tsydenov, Z. B. Tsydenov, Formulation and research of new fitness function in the genetic algorithm for maximum code coverage, Procedia Computer Science 186 (2021) 713-720. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Lund, T. L., Boyd, Direct utilization of geothermal energy 2015 worldwide review, Geothermics 60 (2016) 66-93. [CrossRef]

- R. Dipippo, Geothermal Power Plants: Principles, Applications, Case Studies and Environmental Impact, Third Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, (2012).

- M. Kanoğlu, Jeotermal Elektrik Üretim Sistemleri Ve Kojenerasyon, 7.Ulusal Tesisat Mühendisliği Kongresi, (2005) 289-299.

- D. C. Bandean, S. Smolen, J. T. Cieslinski, Working fluid selection for Organic Rankine Cycle applied to heat recovery systems, World Renewable Energy Congress (2011) 772-779. [CrossRef]

- P. Erdoğmus, M. Toz, Heuristic optimization algorithms in robotics. Serial and Parallel Robot Manipulators-Kinematics, Dynamics, Control and Optimization, InTechOpen (2012) 311–338.

- A. Chauhan, R. P. Saini, A review on Integrated Renewable Energy System based power generation for stand-alone applications: Configurations, storage options, sizing methodologies and control, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 38 (2014) 99-120. Get rights and content. [CrossRef]

- S. Ayan, Sezgi̇sel Opti̇mi̇zasyon Algori̇tmasi Kullanilara Hi̇bri̇t (Fotovoltai̇k-Rüzgar) Enerji Si̇stemi İçi̇n Boyut Opti̇mi̇zasyonu, M.Sc. Thesis, Kırklareli University (2019).

- K. M. Yashawantha, A. V. Vinod, ANN modelling and experimental investigation on effective thermal conductivity of ethylene glycol:water nanofluids, Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 145 2 (2020) 609-630. [CrossRef]

- F. Yılmaz, An innovative study on a geothermal based multigeneration plant with transcritical CO2 cycle: Thermodynamic evaluation and multi-objective optimization, Process Safety and Environmental Protection 185 (2024) 127-142. [CrossRef]

- S. Halilovic, F. Böttcher, K. Zosseder, T. Hamacher, Optimization approaches for the design and operation of open-loop shallow geothermal systems, Advances in Geosciences 62 (2023) 57-66. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, A. M. Abed, S. Y. Eldin, Y. Aryanfar, J. L. G. Alcaraz, Exergy analyses and optimization of a single flash geothermal power plant combined with a trans-critical CO2 cycle using genetic algorithm and Nelder–Mead simplex method, Geothermal Energy 11 1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Haghighi, M. R. Pakathcian, M. E. H. Assad, V. N. Duy, M. A. Nazari, A review on geothermal Organic Rankine cycles: modeling and optimization, Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 144 5 (2020) 1799-1814. [CrossRef]

- J. J. C. Barros, M. L. Coira, M. P. D. L. C. Lopez, A. D. C. Gochi, I Soares, Probabilistic multicriteria environmental assessment of power plants: A global approach, Applied Energy 260 (2020) 114344. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Ciriaco, M. H. Uribe, S. J. Zarrouk, T. Downward, J. B. Omagbon, J. J. C. Austria, D. M. Yglopaz, Probabilistic geothermal resource assessment using experimental design and response surface methodology: The Leyte geothermal production field, Geothermics 103 (2022) 102426. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, C. Xiao, W. Yang, X. Liang, L. Zhang, X. Wang, Probabilistic Geothermal resources assessment using machine learning: Bayesian correction framework based on Gaussian process regression, Geothermics 114 (2023) 102787. [CrossRef]

- Y. V. Pehlivanoglu, Optimizasyon: Temel kavramlar ve yöntemler, Ankara (2017).

- B. Rudiyanto, M. S. Birri, Widjonarko, C. Avian, D. M. Kamal, M. Hijriawan, A Genetic Algorithm approach for optimization of geothermal power plant production: Case studies of direct steam cycle in Kamojang, South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 45 164 (2023) 1-9. [CrossRef]

- S. Podlasek, M. Jankowski, P. Bałazy, K. Lalik, R. Figaj, Application of ANN control algorithm for optimizing performance of a hybrid ORC power plant, Energy (2024) 132082. [CrossRef]

- J. Ullah, H. Li, P. Soupios, M. Ehsan, Optimizing geothermal reservoir modeling: A unified bayesian PSO and BiGRU approach for precise history matching under uncertainty, Geothermics 119 (2024) 102958. [CrossRef]

- S. Haykin, Neural networks and Learning Machines, Third Edition, Pearson New jersey (2008).

- C. M. Bishop, Pattern recognition and machine learning, Springer Cambridge, (2006).

- I. Goodfellow, Y. Bengio, A. Courville, Deep Learning, MIT Press, (2016).

- W. Ling, Y. Liu, R. Young, T. T. Cladouhos, B. Jafarpour, Efficient data-driven models for prediction and optimization of geothermal power plant operations, Geothermics 119 (2024) 102924.

- F. F. Li, J. Johnson, S. Young, CS231 n: Convolutional neural networks for visual recognation, Stanford University, (2019). http://cs231n.github.io/neural-networks-1/.

- M. A. Kızrak, Video görüntülerinde kalabalık analizi, PhD Thesis, Yıldız Technical University (2021).

- E. Alpaydın, Yapay öğrenme, İstanbul Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayınevi, (2018).

- V. A. Cicirello, Evolutionary Computation: Theories, Techniques, and Applications, Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 14 6 (2024) 4-9. [CrossRef]

- M. Mitchell, An introduction to genetic algorithms, MIT press, London, (1998).

- D. E. Goldberg, Genetic algorithm: in search, optimization and machine learning, Addison-Wesley, (1989).

- M. A. Kızrak, Akut lenfosit löseminin çekirdek sağrı regresyonu yöntemiyle tanınması, M.Sc. Thesis, Haliç University, (2011).

- A. A. AbdulHamed, M. A. Tawfeek, A. E. Keshk, A genetic algorithm for service flow management with budget constraint in heterogeneous computing, Future Computing and Informatics Journal 3 2 (2018) 341-347. [CrossRef]

- C. Yılmaz, O. Sen, Thermoeconomic analysis and artificial neural network based genetic algorithm optimization of geothermal and solar energy assisted hydrogen and power generation, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 47 37 (2022) 16424-16439. [CrossRef]

- A. Farajollahi, M. Baharvand, H. R. Takleh, Modeling and optimization of hybrid geothermal-solar energy plant using coupled artificial neural network and genetic algorithm, Process Safety and Environmental Protection 186 (2024) 348-360. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ehyaei, A. Ahmadi, M. A. Rosen, A. Davarpanah, Thermodynamic optimization of a geothermal power plant with a genetic algorithm in two stages, Processes 8 10 (2020) 1-16. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, G. Lui, S. Liao, Probing dominant flow paths in enhanced geothermal systems with a genetic algorithm inversion model, Applied Energy 360 (2024). [CrossRef]

- O. Özkaraca, A Review on Usage of Optimization Methods in Geothermal Power Generation, Mugla Journal of Science and Technology 4 1 (2018) 130-136. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Popescu, C. Popescu, Geothermal Plant Design Optimization By Genetic Algorithms, Antalya, World Geothermal Congress 5 (2003) 13-20.

- O. Özkaraca, A. Keçebaş, C. Demircan, Comparative thermodynamic evaluation of a geothermal power plant by using the advanced exergy and artificial bee colony methods, Energy 156 (2018) 169-180. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, H. Xi, T. Ding, J. Wang, Z. Li, Energy efficiency optimization of an integrated heat pipe cooling system in data center based on genetic algorithm, Applied Thermal Engineering, 182 (2021) 115800. [CrossRef]

- N. H. Mokarram, A. H. Mosaffa, A comparative study and optimization of enhanced integrated geothermal flash and Kalina cycles: A thermoeconomic, Energy 162 (2018) 111-125. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).