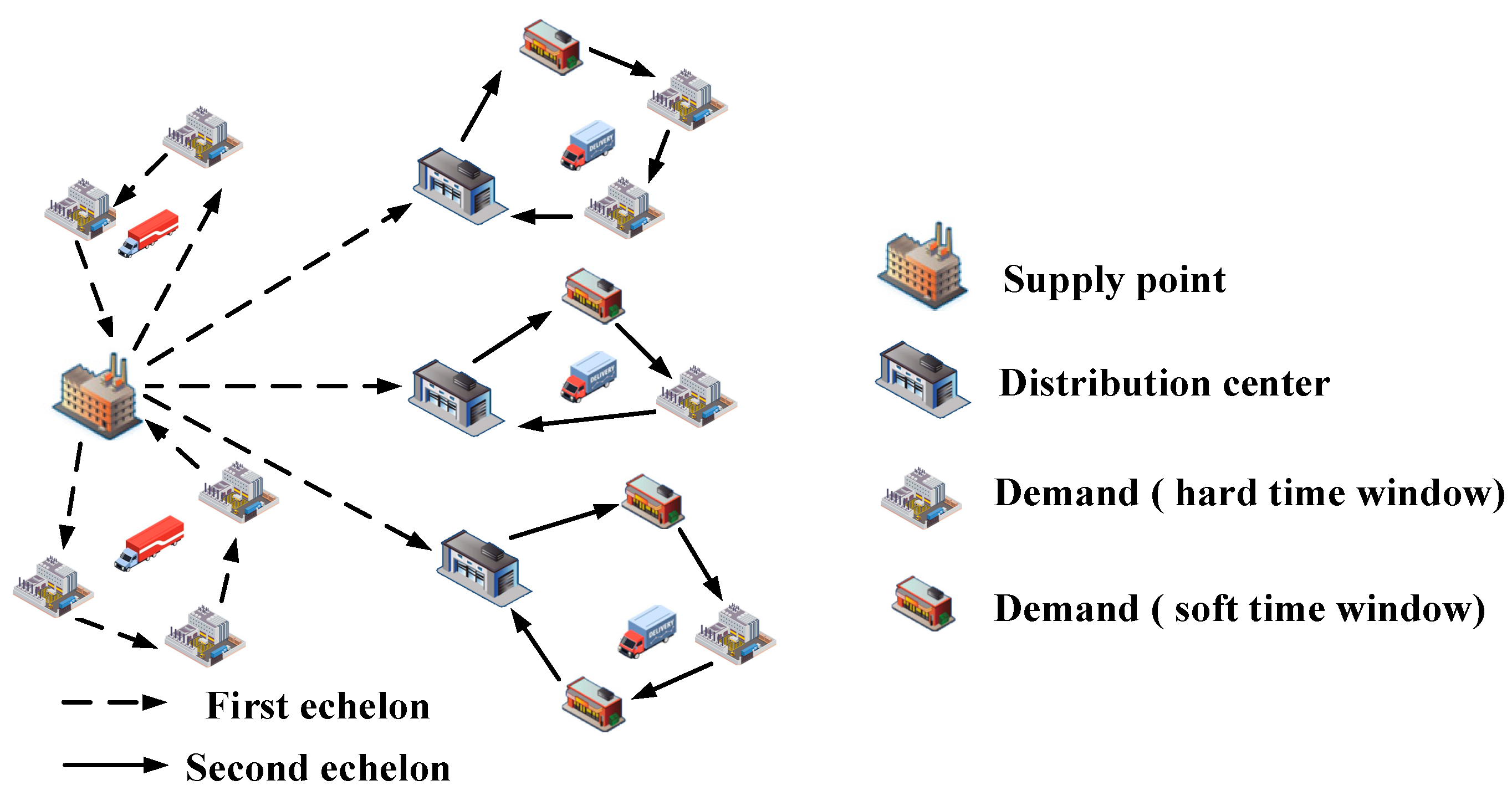

In the present study, a two-tier heuristic algorithm is employed to address the VRP for the joint distribution of perishable goods through one-echelon and two-echelon networks. This problem is characterized by its high model complexity and numerous constraints, classifying it as an NP-hard issue where exact algorithms struggle to find optimal solutions. Consequently, heuristic methods are utilized to derive solutions. For the problem at hand, a two-stage heuristic algorithm has been designed. In the first stage, the vehicle routing initial solution is obtained using the k-medoids clustering algorithm and a greedy algorithm. The k-medoids clustering algorithm is selected for its robustness, as it is not influenced by outliers and offers strong adaptability to different distributions. This algorithm also provides a relatively fast solution speed and accurate data set partitioning. Therefore, a time-space distance-based k-medoids clustering algorithm is applied to cluster the demand nodes. Following the clustering results, a greedy algorithm is employed to construct the initial route. Moreover, considering the impact of the initial clustering centers on the clustering outcome, the K-Means++ initialization method is utilized to select the initial clustering centers, thereby enhancing the quality and efficiency of the clustering. In the second stage, a hybrid approach that integrates the linear programming ideas of the Ortools solver with the flexibility and local search capabilities of the ALNS algorithm is proposed to optimize the initial routes. This approach leverages a linear-programming-enhanced ALNS algorithm, which offers a robust mechanism for addressing the complexities associated with the problem.

4.1. K-Center Clustering Algorithm Considering Spatio-Temporal Distance

In addressing routing optimization challenges within VRP, clustering algorithms are commonly employed, with distance serving as the primary factor. In this paper, it is argued that clustering demand nodes that are close geographically but have significant differences in their time windows can lead to unfeasible solutions or result in low transportation costs offset by high penalty costs related to time windows. Consequently, an approach that integrates both spatial and temporal distances has been adopted. The concept of "spatio-temporal distance" is introduced, and a k-center clustering algorithm based on this concept is proposed to cluster customers with similar spatio-temporal proximities, thereby preventing the aforementioned problems.

Spatio-temporal distance is calculated as a weighted average of the normalized spatial and temporal distances between customers. Considering both soft and hard time windows for customer demands, assume customers at nodes and have time windows()and(), respectively. It is assumed that, and vehiclearrives at node at time(). The arrival time of vehicle at node then falls within the interval, where, .

The temporal distance between points and is categorized as follows when point is subject to a hard time window:

(1) If , then the vehicle is considered to have arrived at demand node before the earliest acceptable service time. A penalty coefficient, , is applied, and the temporal distance between points i and j is determined as .

(2) If , then the vehicle is considered to have arrived after the latest acceptable service time at hard time window demand node j. A penalty coefficient, M, is applied, and the temporal distance is determined as .

(3) If or , then the vehicle's arrival time at demand node aligns with the expected time window. A deviation coefficient, , is applied, and the temporal distance is determined as .

(4) If , then the vehicle's arrival at demand node is considered to be perfectly within the desired time window, and the temporal distance is calculated as.

For customer point characterized by a soft time window, the following scenarios are considered:

(1) If , meaning the vehicle arrives before the earliest acceptable service time within the soft time window, a penalty coefficient M is applied. The temporal distance is calculated as.

(2) If , indicating that the vehicle arrives after the latest acceptable service time for a customer point with a soft time window, the penalty coefficient M is again applied. The temporal distance is calculated as.

(3) If , the vehicle's arrival time at customer point falls between the expected and acceptable time windows. A penalty coefficient is applied, and the temporal distance between points and is calculated as .

(4) If , the vehicle's arrival at customer point j also falls between the expected and acceptable time windows. A penalty coefficient is applied, and the temporal distance is calculated as .

(5) If or , the vehicle's arrival time at customer point coincides with the expected time window. A deviation coefficient is applied, and the temporal distance between points and is calculated as.

(6) If , the vehicle perfectly arrives within the expected time window at customer point , and the temporal distance is computed as .

In summary, when calculating the temporal distance between nodes

and

, with node

being a hard time window demand node, the formula for temporal distance is defined according to the aforementioned scenarios.

When calculating the temporal distance between demand nodes

and

, where node

has a hard time window requirement, the formula for temporal distance is as follows:

The spatial distance between demand nodesandis defined as.

Weights are assigned to spatial and temporal distances to derive the formula for spatio-temporal distance

as shown in Equation (39):

The specific implementation process of the k-center clustering algorithm is as follows:

Step 1: A random point from the demand nodes is selected as the first clustering center. The minimum spatio-temporal distance from each demand node to the nearest cluster center is calculated. The point with the maximum is chosen as the next cluster center. This process is repeated until three initial cluster centers are identified.

Step 2: The spatio-temporal distance from each demand node to the three cluster centers is calculated. According to the principle of nearest spatio-temporal distance, all demand nodes are assigned to the corresponding cluster center dataset, resulting in three clusters.

Step 3: For each cluster, the dataset is traversed assuming each data point as a cluster center. The sum of distances from all other points to this point is calculated, and the point with the smallest sum of distances is selected as the new cluster center.

Step 4: The spatio-temporal distance from each demand node to the new cluster center is recalculated, and the points are reassigned based on the nearest principle.

Step 5: After each reassignment, the cluster centers are updated until there are no changes in the cluster dataset. The distance from each cluster center to the distribution center is calculated. Each cluster is assigned to the nearest distribution center, and the clustering results are output.

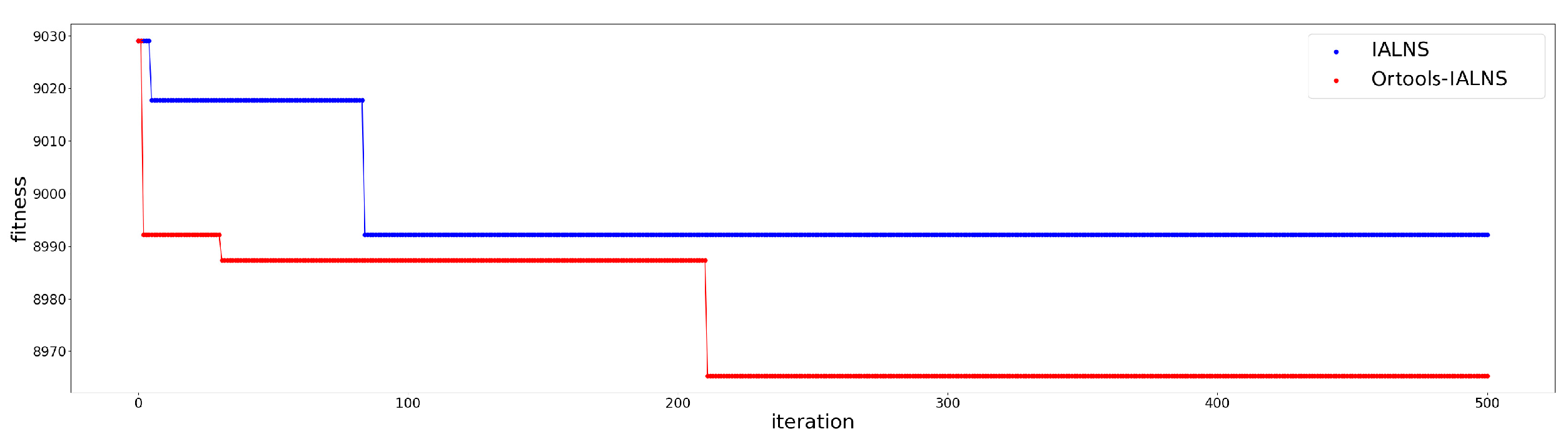

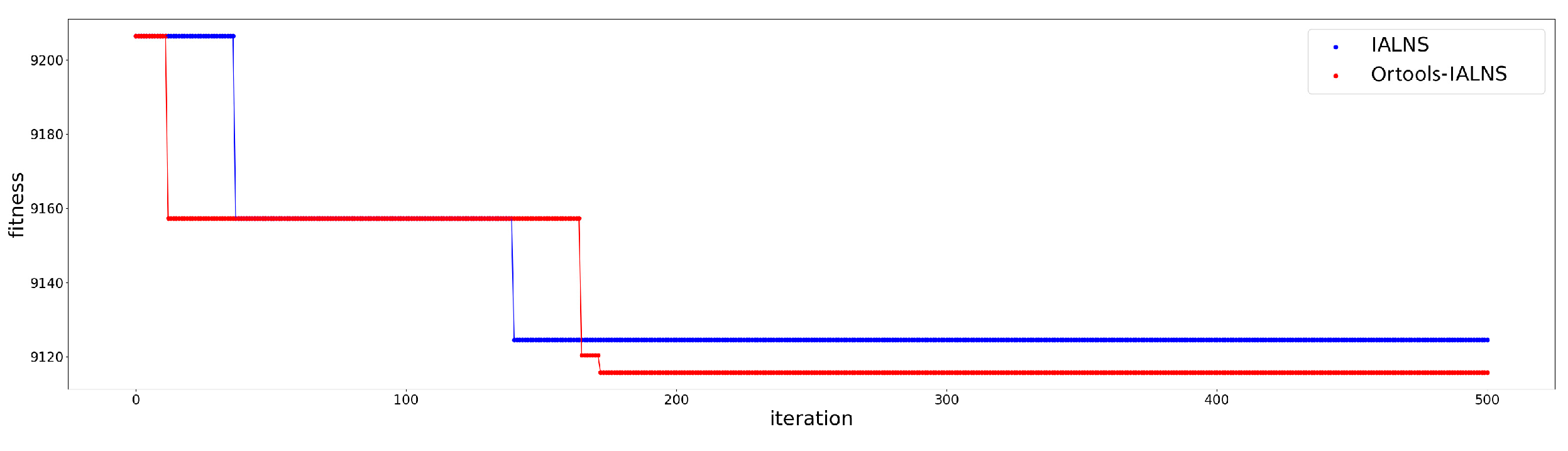

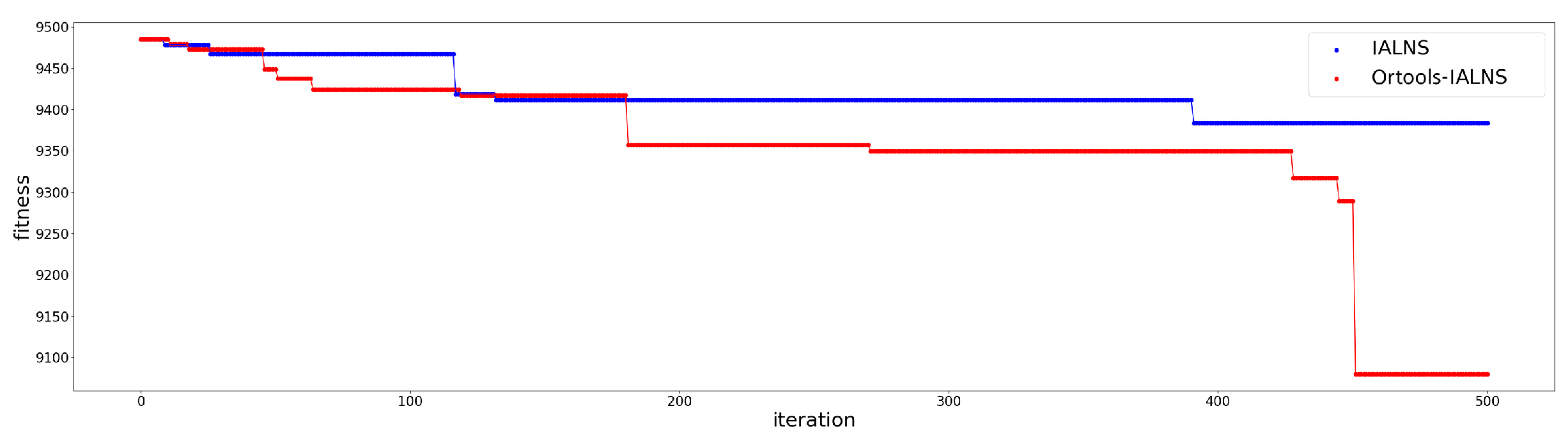

4.3. Enhanced ALNS Algorithm Based on Linear Programming

In comparison to the conventional ALNS algorithm, the enhanced version developed in this paper incorporates four types of deletion operators and three types of repair operators based on the classification of demand nodes, along with two swap operators to expand the search space. Rather than using a fixed scoring strategy for operators, operators are scored based on the objective value of each iteration, which assists in escaping local optima. It has been observed that updating operator weights at each iteration results in superior outcomes by effectively avoiding local optima, increasing operator randomness, enhancing the diversity of solutions, and broadening the search space. Hence, a strategy of updating weights with each iteration is adopted.

The enhanced ALNS algorithm, which integrates the linear programming solution approach of the Ortools solver, operates on the principle of storing updated solutions from each iteration in a set of sub-tour solutions. When the iteration count i modulo 30 equals zero, to increase the diversity of solutions, a set of 1000 random sub-tours is generated. The Ortools solver's linear programming framework is then applied to both the stored and the randomly generated sub-tours to determine the optimal sub-tour combination, which forms a new solution. This new solution is established as the current solution. If the termination criteria are not met, this current solution continues to be used in subsequent iterations of the ALNS algorithm until the termination conditions are fulfilled.

4.3.1. Destruction Operators

(1) Random Removal Operator

This operator randomly selects q demand nodes for deletion. While it may generate lower-quality solutions, it increases neighborhood diversity and expands the search space, assisting in escaping from local optima.

(2) Worst Cost Saving Removal Operator

This operator removes q demand nodes that offer the greatest cost savings. Cost savings refer to the reduction in the objective function value when a demand node is removed from the route. Demand nodes are ranked by their cost-saving potential, and the top q are removed, effectively reducing the total distribution cost.

(3) Route Deletion Operator

In this operator, a route with the fewest number of service demand nodes or the highest cost is selected randomly, and all demand nodes on this route are deleted. If the number of deleted demand nodes is less than q, another route is randomly selected until the total number exceeds or equals q. This operator can enhance vehicle utilization and reduce overall transportation costs.

(4) Worst Satisfaction Removal Operator

This operator sorts demand nodes with soft time windows by decreasing satisfaction of time constraints and removes the top q nodes with the lowest satisfaction. This effectively removes demand nodes with poor time satisfaction from the route, potentially improving overall route efficiency and customer satisfaction.

4.3.2. Repair Operators Based on Demand Node Types

(1) Cost-Considerate Greedy Insertion Operator Based on Demand Node Type

Demand nodes are categorized into three types: those with hard time windows deliverable only via one-echelon routes, those with soft time windows deliverable through either first-echelon or second-echelon routes, and the remainder with hard time windows.

Step 1: Calculate the optimal insertion node for each removed demand node to be reinserted into the route, aiming to minimize the increase in the objective function.

Step 2: Select the demand node with the lowest integration cost, and assess the type of demand node. Subject to vehicle capacity constraints and the satisfaction of the time windows, demand nodes with hard time windows that are restricted to one-echelon routes are reinserted into one-echelon distribution paths; otherwise, they are inserted into two-echelon routes.

Step 3: Update the integration costs of the remaining removed demand nodes and repeat Step 2 until all removed demand nodes are reinserted into the route.

(2) Random Insertion Operator Based on Demand Node Type

Removed demand nodes are randomly inserted into the current solution within the constraints. Demand nodes with hard time windows that must be serviced via first-echelon routes are inserted into first-echelon distribution paths, while other demand nodes are randomly integrated into second-echelon routes.

(3) New Vehicle Insertion Operator Based on Demand Node Type

Under the constraints, demand nodes are categorized for distribution. For those with hard time windows that can only be serviced via first-echelon routes, a new first-echelon vehicle is added to distribute them in a random order. Other demand nodes are serviced by adding a second-echelon vehicle also distributing in a random order.

(4) Best Timing Insertion Operator Based on Demand Node Type

Before adding demand node to a route, it is necessary to confirm that the service timing at this node falls within its acceptable time window. Additionally, the arrival times at subsequent nodes on the route must also meet their respective time windows. Based on these constraints, the time deviation is calculated. The demand node is then inserted into the position where is minimized.

4.3.3. Swap Operators

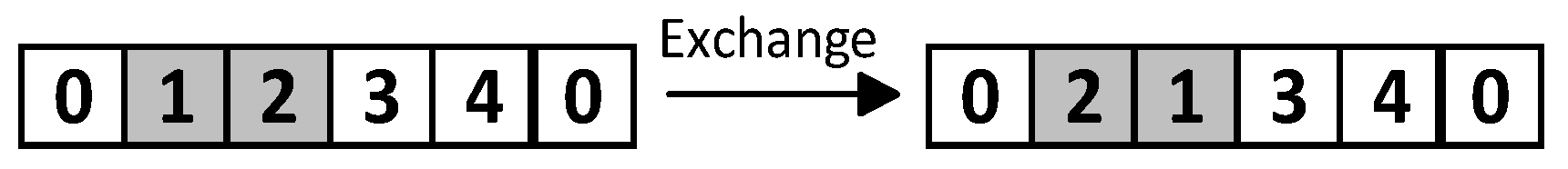

(1) Single-Vehicle Swap Operator

Randomly swap the order of demand nodes visited on a single vehicle's route to generate a new route, as depicted in the

Figure 2.

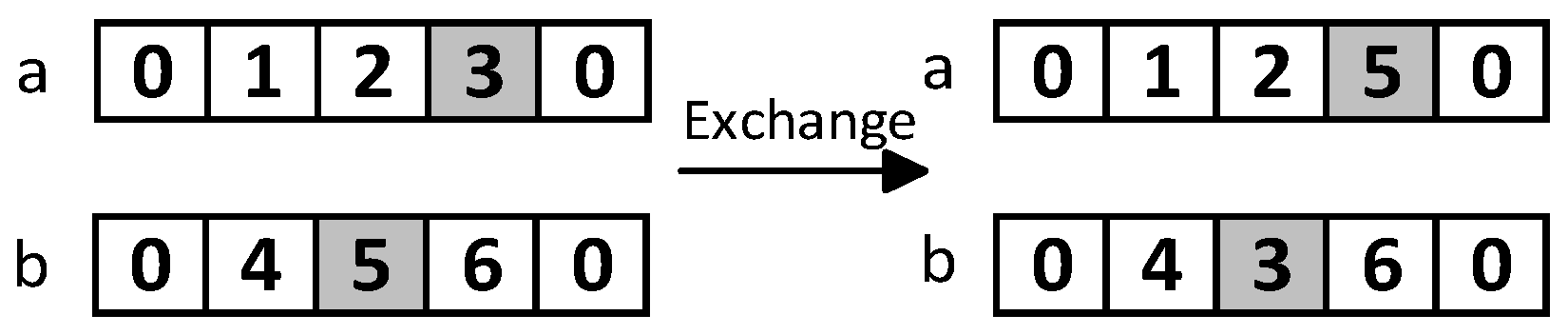

(2) Multi-Vehicle Swap Operator

Randomly perform a swap of demand nodes between two vehicles' routes to generate a new route configuration, as shown in the

Figure 3.

4.3.4. Acceptance Criteria, Operator Scoring Strategy, Operator Weight Update, and Termination Conditions

During the iterative process, non-improving solutions are accepted. These are updated solutions that are not superior to current solutions. Acceptance is based on the judgment criteria of the simulated annealing algorithm. This algorithm accepts solutions with a certain probability. In the presence of multiple deletion, repair, and exchange operators, a roulette wheel method is used for selection. Initially, all operators are assigned a weight of zero. Operator scores are updated in each iteration. Updates are based on the performance of deletion, repair, and exchange operators. Operators receive a score increment calculated as (1/objective function of this iteration)+a very small number. These increments allow for the updating of weights for deletion and repair operators based on the scores obtained.

where

represents the weight of the operator at iteration

,

is the weight update parameter,

is the total score of the operator at iteration

, and

represents the total number of times the operator has been used up to iteration

.

To prevent certain operators from being overlooked, a special method is used. High-weight operators are often repeatedly selected. This can reduce the search capabilities of the algorithm in its later stages. When operators with a weight of zero exist, they are preferentially selected. This selection is done using the roulette wheel method. In this research, the algorithm terminates when the maximum number of iterations is reached.

4.3.5. Two-Stage Heuristic Algorithm Basic Solving Process

Step 1: Construct initial route solutions using a space-time distance-based k-center algorithm and greedy algorithm.

Step 2: Set the initial solutions as the current and best solutions, and establish initial parameters, including initial scores and weights for the operators and the initial temperature for simulated annealing.

Step 3: Check if the termination conditions are met. If so, output the optimal solution; otherwise, proceed to Step 4.

Step 4: Update the weights of the destruction, repair, and swap operators.

Step 5: Select destruction, repair, and swap operators using the roulette wheel method to process the current solution and generate a new feasible solution, and proceed to Step 6.

Step 6: Compare the objective function value of the new feasible solution with that of the current solution. If the new solution improves the objective function, set this new solution as the current solution, then continue to Step 7; otherwise, proceed to Step 8.

Step 7: Compare the current solution with the best solution. If the current solution improves upon the best solution, set the current solution as the best solution, then proceed to Step 9.

Step 8: If a non-improving solution is generated, determine whether to accept this solution based on the simulated annealing criteria. If accepted, update the current solution; otherwise, maintain the original current solution, then proceed to Step 9.

Step 9: Update the scores of the destruction, repair, and swap operators in the operator score ledger.

Step 10: Check if the iteration number i modulo 30 equals zero; if so, consider using the Ortools solver's linear programming approach to solve for the optimal sub-route combination from a set of iteratively generated sub-route solutions and randomly generated sub-route solutions, set the newly obtained solution as the current solution and initialize the set of sub-route solutions; otherwise, return to Step 3.

The pseudocode for the Two-Stage Heuristic Algorithm is as follows:

| IALNS Based on Linear Programming |

| Input:demand data, model parameters |

| Output: optimal solution |

1 Cluster demand nodes using a spae-time distance-based k-center clustering

2 Construct initial solution S using a greedy algorithm |

3 Set Sbest = S, Scur = S

4 Repeat |

5 Select a set of destruction, repair, and exchange operators (d, r, c) using

the roulette wheel method |

| 6 Snew = c(r(d(s))) |

| 7 if accept (Snew , Scur) then |

| 8 Scur = Snew |

| 9 if f(Snew) < f(Sbest) then |

| 10 Sbest = Snew |

| 11 End if |

| 12 End if |

| 13 Store Snew in sub-loop combinations |

| 14 Update operator weights |

| 15 i = i +1 |

| 16 if i % 30 = 0 |

17 Use integer programming to solve the optimal sub-loop combinations and update neighborhood search Scur

Initialize sub-loop combinations |

| 18 End if |

| 19 Until the termination condition is met |

| 20 Return Sbest |