1. Introduction

The realization of smart cities has been intimately linked to the Internet of Things (IoT), especially with more complex services implemented using the incorporation of various IoT applications. Cross-domain or cross-vertical apps have been used to describe these prospective applications [

1]. As a result, a smart city can be seen as the combination of various standalone Internet of Things applications, where the cooperation of applications from other domains can make different complex circumstances simpler and more efficient. The cloud analytics layer, which is defined by vast computational and storage capability, serves as the foundation of all smart city activities. Here, all historical data are archived for various purposes.

The sensors and devices layers are made up of IoT appliances (like security cameras, traffic lights, and smart meters) that produce various application-specific data. Additionally, there is a need to add a fog layer between the devices and the cloud layers to test real-time responsiveness [

2]. A proposed technique for context-aware traffic scheduling is energy-efficient [

3,

4], which first classifies IoT applications according to their diverse traffic requirements before mapping them to different weighted quality classes. The term "delay-sensitive applications" refers to the shift in IoT applications over the past ten years from being primarily applications based on data collection to considerably more sophisticated applications utilizing advanced machine learning [

5,

6], frequently operating under time constraints from a delay perspective. In IoT environments, fog devices are commonly employed, and enough literature concentrates on managing fog layer energy. A genetic algorithm was employed in Reference [

7,

8] to reduce the number of failed nodes and energy usage in an IoT-based fog model.

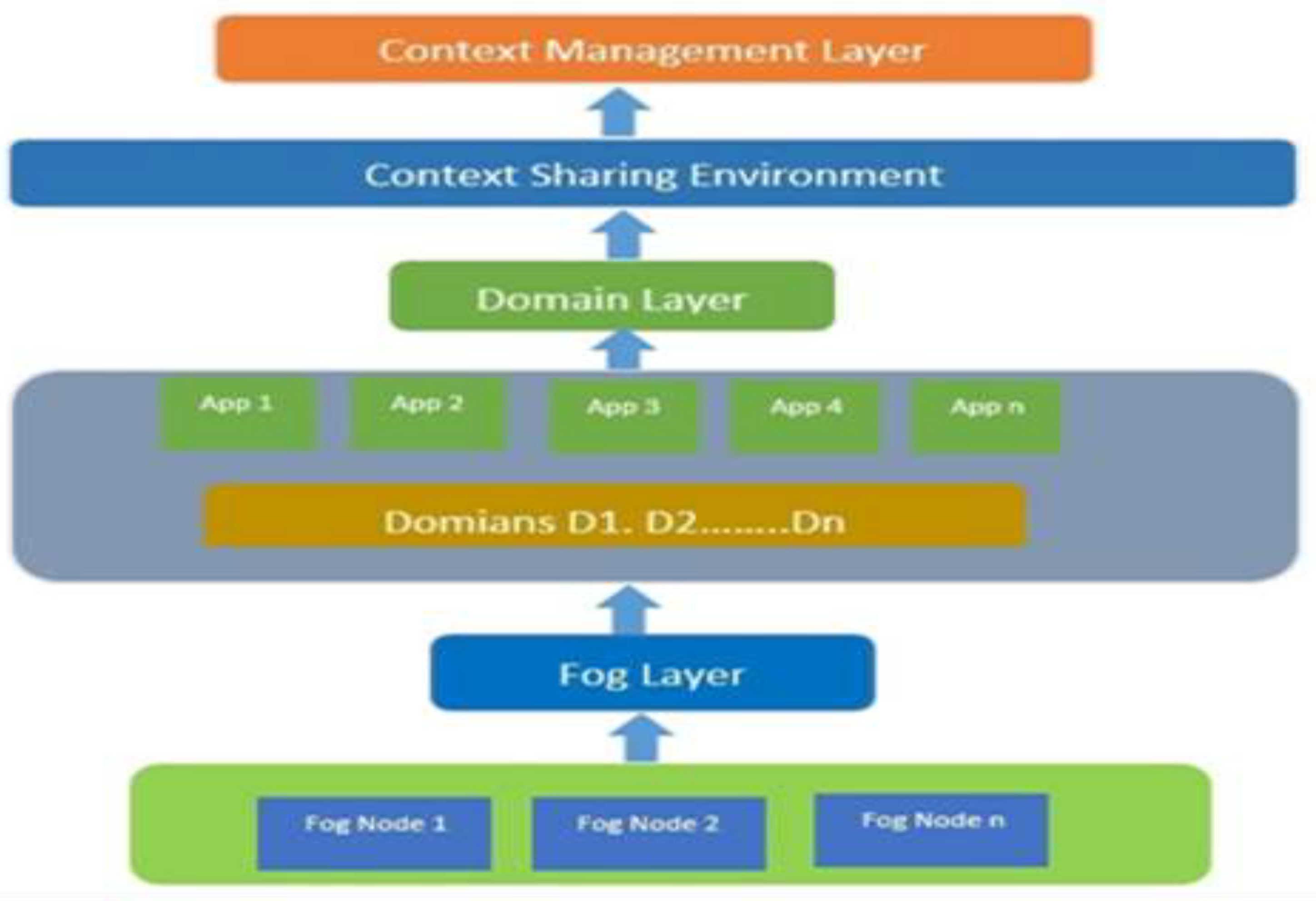

Figure 1 shows the general IoT context-aware architecture, where three layers have been described to represent the whole architecture of the IoT-based environment.

It should define the purpose of the work and its significance.

Similarly to this, there is enough research available that uses various optimization strategies to reduce energy use at the fog level. Fog layer developments in smart city research have just lately been recognized for their significance and research potential [

9,

10]. However, very few studies have truly dealt with energy reduction at the fog layer. Numerous researchers applied various optimization strategies to service placement at various levels to further increase its effectiveness [

11,

12]. The problem with IoT applications using fog resources for services was proposed by Skarlat et al. [

13] while taking into account the application and resource heterogeneity concerning QoS attributes.

Multi-objective optimization techniques are used in [

14] to handle the service placement problem across several platforms. Guerrero et al. work [

15] provides a comparison of various optimization strategies. In the research work published by Kaur [

16], the use of the genetic algorithm and artificial neural network to predict and forecast service scheduling. The remainder of this article is organized as follows: The background of the services offered by smart cities is briefly covered in

Section 2, along with how context-aware computing is used at the fog layer to deliver services. A discussion of optimization for the fog energy model is also included in section 3. The experimental setup for replicating various scenarios is presented in

Section 4.

Section 5 presents and analyses the experimental findings. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Background

Different services make up a smart city, and each of these services is given a priority number based on how much delay the application can handle while providing its services. Each fog node within its sensing range receives an "R" number of service requests from IoT devices, some of which are more than the fog node's computer power can handle. Furthermore, a fog node's available computational resources are not set at any given moment in time, making it challenging to anticipate upcoming request types and a deadline. These situations are regularly seen in smart city applications, and in these cases, it becomes quite challenging to continuously supply end customers with an efficient service given all of these limitations. We also need to think about whether there are enough context instances of the required type at the specified Fog node. In the lack of the required categories of context instances or a sufficient number of context instances, an efficient context-sharing or migration mechanism aids in reducing the burden at the fog node. [

17,

18].

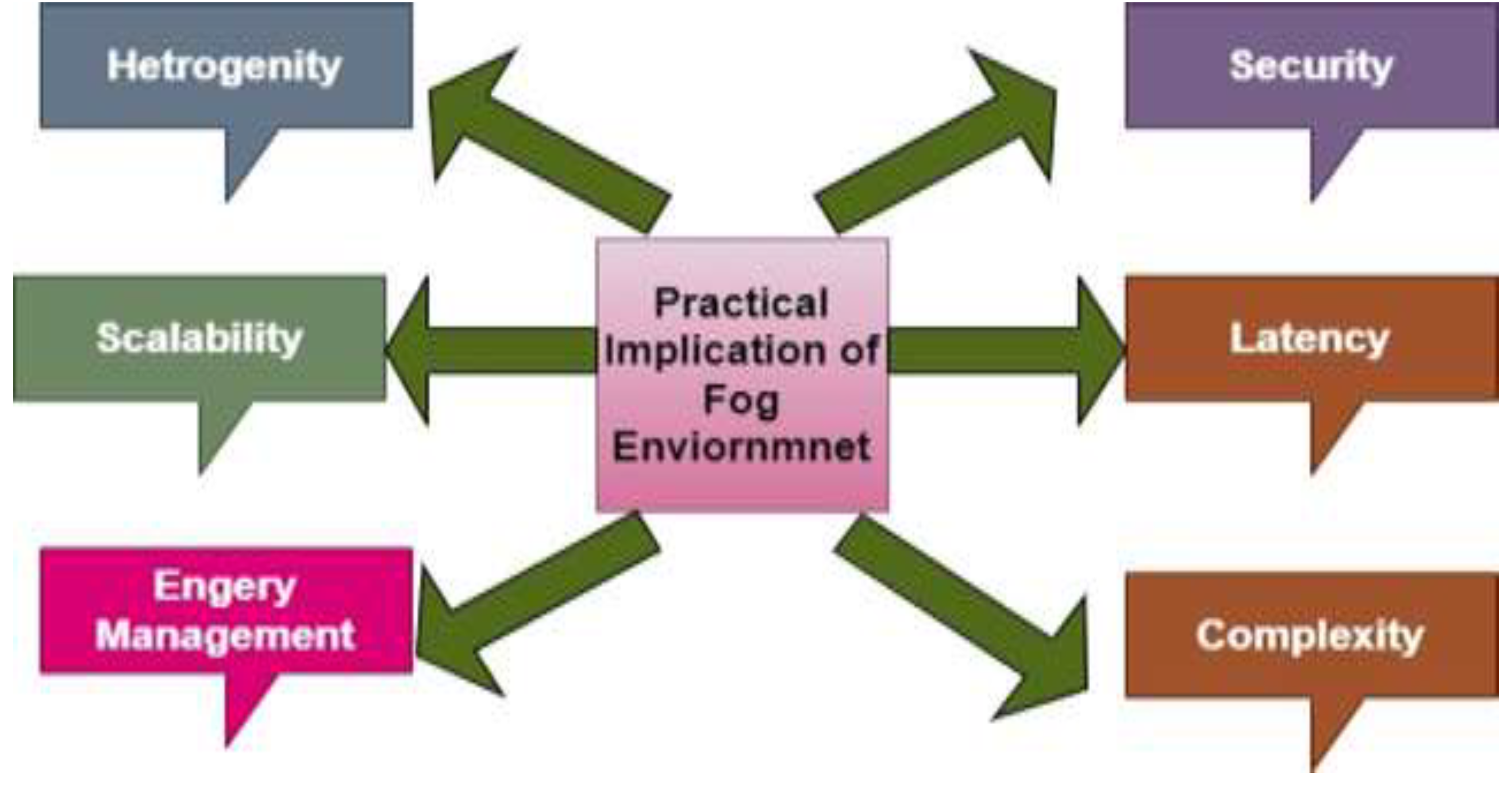

Figure 2 shows the practical implications of the IoT for the environment. Performance, security, and cost-effectiveness are all improved by the practical consequences of integrating fog computing into IoT systems. Leveraging fog computing will be crucial for tackling issues with latency, scalability, and energy management as IoT continues to spread across several industries and guaranteeing that strong security measures are in place.

Survey papers have been written about several facets of fog computing. Shi et al. [

18], for instance, have examined the crucial elements of fog computing for healthcare systems. Shi et al. [

19], for instance, looked at the crucial components of fog computing for healthcare systems. Additionally, Yi et al. study of fog computing included a discussion of different fog computing application scenarios and potential issues that might occur while putting these systems into place [

20]. Central Fog functions are housed in a software-defined resource management layer in the suggested architecture [

21]. This provides a middleware that runs in the cloud to prevent Fog colonies from behaving independently.

Fog cells are analyzed and controlled, and cloud-based middleware keeps track of them. In addition, Bonomi et al. [

22] discussed essential aspects of fog computing and how it extends and enhances cloud computing to investigate the integration of IoT with fog computing. A hierarchically distributed Fog design was also proposed. To evaluate the qualities of their design, they presented examples of a wind farm and an automated traffic signal system. A paradigm for comprehending, assessing, and modeling delays in IoT-Fog-Cloud systems was put forth by Yousefpour et al. [

23]. They suggested a delay-minimizing Fog nodes policy to reduce service delay for IoT nodes. By sharing the burden, the suggested approach employs communication amongst Fog to reduce service delays. For calculation offloading, the strategy takes into account not only queue lengths but also diverse request types with various processing times.

Furthermore, the authors developed a framework for the comprehensive analysis of service delays from the perspective of fog cloud structures and conducted substantial simulation tests to back up the framework and recommended regulations. The security and privacy concerns brought on by merging fog computing with the IoT were presented by Lee et al. [

24] [

25]. They claimed that implementing the IoT with fog creates several security risks. It was also underlined how important it is to create a secure Fog computing environment using different security methods.

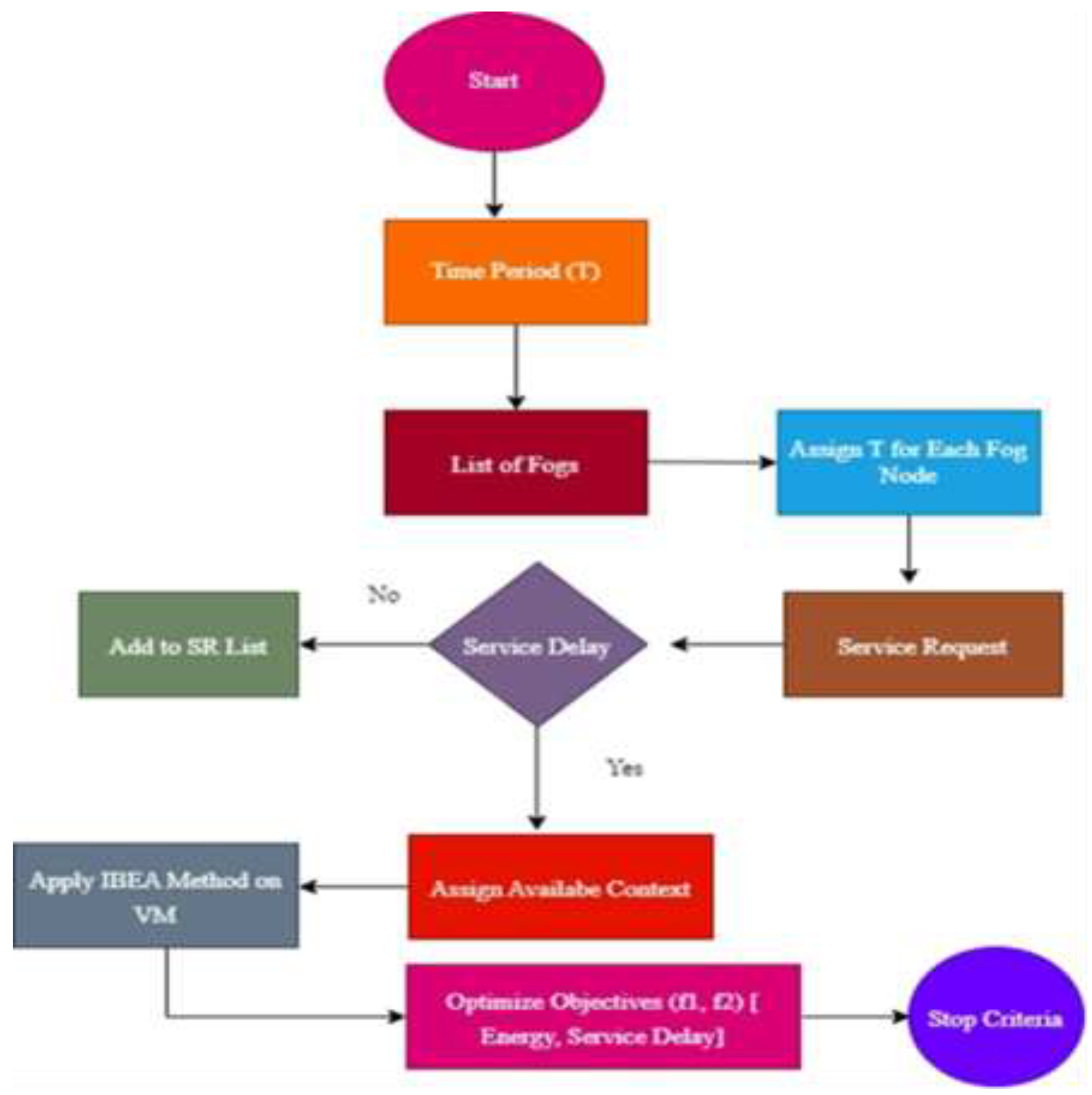

Figure 3 represents the application of evolutionary algorithms in the smart city context.

Using evolutionary algorithms in the context of smart cities is a transformative approach to governing and designing metropolitan areas. These algorithms can improve resource allocation, energy usage, traffic management, and other elements of smart city operations. These algorithms do this by imitating natural selection processes. Furthermore, by dynamically modifying power distribution in response to real-time demand data from Internet of Things sensors, these algorithms can improve energy efficiency while minimizing waste and expenses. Overall, the application of evolutionary algorithms to smart city settings not only simplifies processes but also promotes sustainable urban growth by enabling data-driven choices that improve the standard of living for citizens.

They also reviewed existing security methods that can be effective in securing the IoT with Fog. In addition, using a hierarchical computing design, Hong discussed that Mobile Fog (MF) distributes IoT applications over several devices, from the edge devices to the Cloud [

26]. The MF uses a dynamic node discovery process to join devices in parent-child associations, where data from child nodes is handled by parent nodes. MFs' capability to collect and analyze data locally on end-user devices offers several benefits for IoT applications. A taxonomy of the fog computing environment, as well as difficulties and characteristics, were described by Mahmud et al. and others [

27,

28,

29]. They highlighted the variations between mobile cloud computing, mobile edge computing, cloud computing, and fog computing. Their research explored networking setups, different Fog computing metrics, and Fog node settings.

Multi-objective optimization is used by IoT fog computing to improve system performance while addressing resource usage and energy efficiency [

30]. In applications like product lines and telehealth, where energy-efficient solutions are essential, this paradigm of multi-objective optimization is especially pertinent [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Hybrid algorithms and NSGA-II are two examples of multi-objective optimization approaches that help balance competing metrics like throughput, energy usage, and latency. The Hybrid Multi-objective Harris-Hawks and Moth-Flame Optimization Algorithm (HMHMFOA), for example, exhibits enhanced techniques for task offloading while maximizing resource utilization and reducing latency [

36]. Furthermore, in diverse contexts, frameworks such as Tof-NSGAII manage task offloading successfully, resulting in notable energy reductions with negligible latency increases [

37]. Deploying delay-sensitive Internet of Things applications in fog computing environments requires the integration of various optimization algorithms to provide the best possible optimal service placement and resource allocation [

38]. Though multi-objective optimization has many advantages, it also adds complexity to the process of balancing several performance measures, which can make decision-making more difficult in real-time systems.

One popular scalarization method in multi-objective optimization, especially for Pareto front optimization, is the epsilon-constraint method. Using this approach, a multi-objective issue is split up into many single-objective problems. One goal is chosen to optimize, and the other objectives are converted into constraints with epsilon (ε) limits. The main advantage of this strategy is that it may produce a wide range of Pareto optimum solutions, which enables decision-makers to properly consider trade-offs between conflicting objectives [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. By directing algorithms toward promising areas, epsilon-dominance improves the exploration of the solution space and guarantees a varied collection of solutions [

39]. By reducing the number of possibilities available to decision-makers, the epsilon constraint approach helps to provide a representative collection of solutions. Based on this technique, algorithms have demonstrated efficacy in preserving coverage and uniformity in the Pareto front representation [

40].

3. Problem Formulation

The two main objectives are optimized in this paper: a) first, to minimize the amount of energy used at the fog layer; b) second, to minimize the total service delays for time-sensitive applications.

3.1. Two Objective Functions Definitions

3.1.1. Minimize Energy Consumption at the Fog Layer (f1)

The first objective is to minimize the overall amount of energy that the fog nodes use while processing Internet of Things requests. This may be written in mathematical terms.

where:

3.1.2. Minimize Total Service Delays for Time-Sensitive Applications (f2)

The second objective is to minimize the overall service time delay that applications need timely responses. This can be shown as.

where:

Dj represents the service delay for application j,

M is the total number of time-sensitive applications

The Eq. (1) and (2) represents the definitions of the two objectives. The optimization problem can thus be framed as:

While subject to constraints relating to the fog computing environment, quality of service standards, network architecture, and resource availability need to be addressed. The aforementioned objectives seek to optimize energy efficiency while guaranteeing that vital applications fulfill their performance prerequisites.

IoT devices within the sensing range of a fog node Fi send requests for services. Let SR1, SR2, SR3,…, SRp are P number of service requests with the corresponding application information that are received at a fog node Fi. These services request all fall under several application kinds, such as A1, A2, A3,…, Ak. Each of these applications needs to process at least "m" context instances, and the exact number would be determined by the application’s paradigm. Incoming service requests are accepted by each fog node for a specific period. These service requests are subsequently handled at the receiving node or a nearby node, depending on the availability of context instances, computation, and the fog node's current load.

Figure 4 shows the methodology framework for two objective functions. This framework explains how two different objective functions, such as minimizing energy usage and minimizing service delay, are formulated to reflect competing objectives. The IBEA uses a population-based approach, wherein alternative solutions are assessed according to how well they perform in comparison to these objectives using certain indicators, such as the ε-epsilon technique, which directs the selection process. The proposed framework generates a collection of non-dominated solutions that show the optimal trade-offs between the two objectives after it runs for a predetermined number of generations or until a stopping requirement is satisfied.

To reduce the energy consumption of these fog nodes, the proposed IBEA algorithm uses a duty cycle technique to plan when the fog nodes will supply these services. The IBEA-based VM scheduling is utilized to balance the load during runtime and lower these VMs' energy usage.

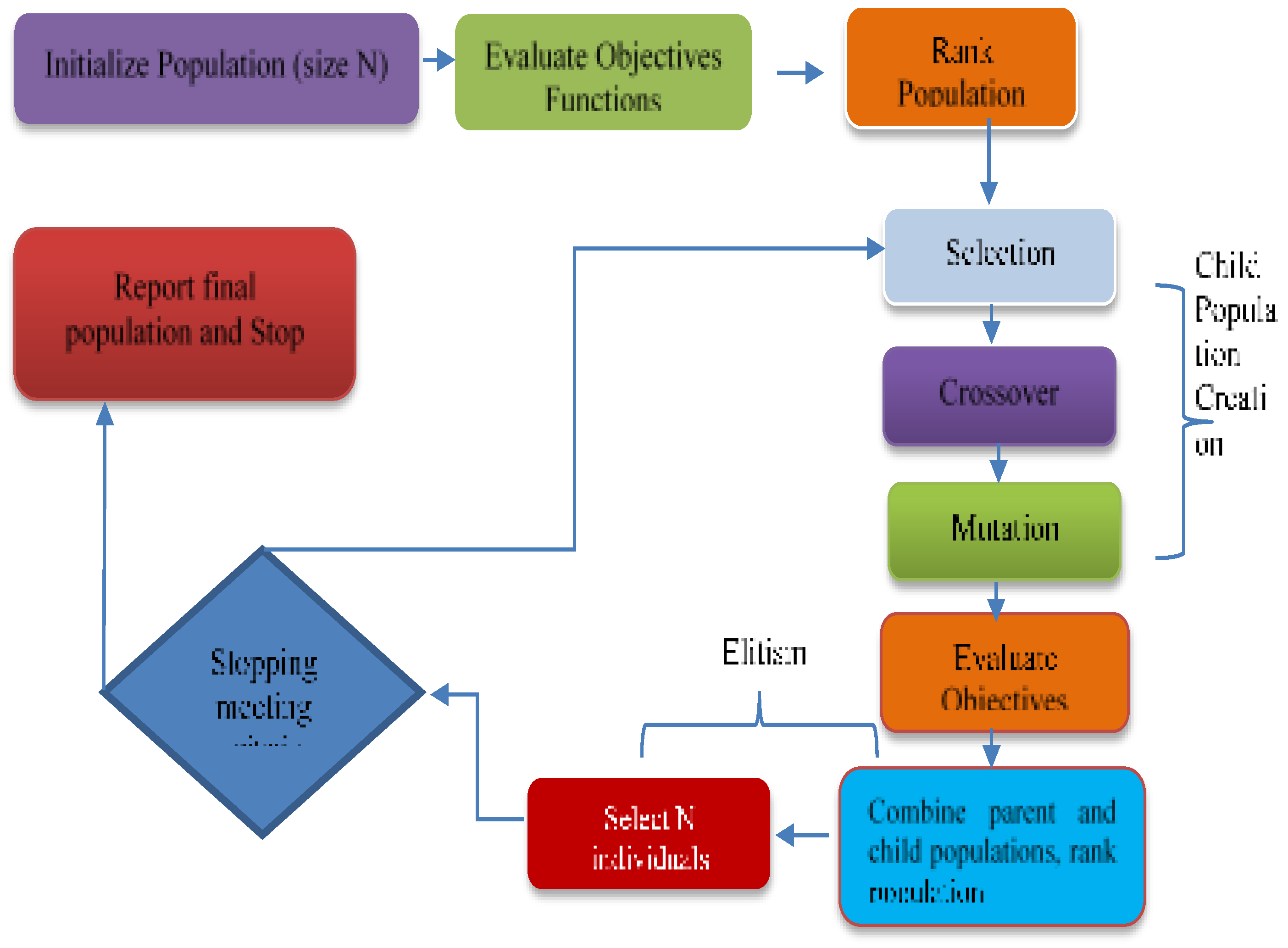

Figure 5 depicts the IBEA's work, and the algorithm's process is given in depth.

3.2. Solution Methodology

The IBEA algorithm must be used to solve the problem of efficient VM scheduling under constraints for a set of smart city tasks with certain restrictions. The ideal VM allocation is attempted via a metaheuristic approach due to its computational complexity. The available VMs with the necessary compute and contexts are given the queued service requests while forming the aforementioned problem as an optimization problem, different random assignments are taken into account as a chromosome. The chromosomes are generated depending on different parameters.

These chromosomes are considered to be the initial population. The total amount of energy used by these nodes is then used to evaluate these chromosomes. The proper selection and mutation activities are carried out and repeated to introduce randomness among the chromosomes. The specific parameters are taken into account while calculating the energy consumption of these fog nodes, as well as the formulas used to do so. Minimizing the overall execution time and the proportion of service requests that fail to finish their tasks are the two objectives of GA Optimizer. Up until all service requests are scheduled, crossover and mutation processes are used.

Table 1 shows pseudocode for IoT fog computing. The pseudocode for IoT Fog Computing describes how data is collected from IoT devices. Usually, it begins with setting up fog nodes and their connections to the cloud and Internet of Things devices. Evolutionary optimization is integrated into the fog computing paradigm in the pseudocode for IoT Fog Computing using IBEA. It starts by setting up a population of possible IoT data processing schemes and fog node configurations. Gathering data from IoT devices and using IBEA to optimize job scheduling and resource allocation comprise the main loop.

IBEA assesses and refines solutions using performance metrics including latency and energy consumption. The algorithm chooses parent solutions for each iteration, creates offspring by applying crossover and mutation operators, and compares and chooses the best solutions using a binary quality indicator (such as the ε-epsilon technique). The population is updated periodically based on real-time performance indicators, which enables the system to adjust to evolving IoT environments. In the fog-IoT environment, this strategy seeks to continually optimize the trade-off between local processing efficiency and overall system performance.

4. Experimental Setup and Validation

The IBEA-based approach for service request assignment in fog computing that incorporates the ε-constraint method has been experimentally validated and shows significant quantitative benefits. CloudSim-Plus framework [

30] with fog extensions was used in the experimental configuration, which included 200 IoT devices making service requests and 50 fog nodes with varying specs (CPU: 1.5-3.0 GHz, RAM: 2-8GB). The implementation of the ε-constraint approach involved using systematically varying ε values to control energy usage while taking response time as the primary objective.

The parameter values chosen for the experimental procedure are displayed in

Table 2. A number of crucial parameters are set up in the Indicator-Based Evolutionary Algorithm (IBEA) implementation for two-objective optimization in order to guarantee effective performance. The algorithm strikes a compromise between processing cost and exploration capabilities by maintaining a population size of 100 potential solutions every generation. While maintaining manageable computing needs, this modest population size guarantees adequate variety in the solution space. In order to give the algorithm enough time to converge for optimal solutions, it is programmed to run for 200 generations. The algorithm can fully search the solution space with this number of iterations, and it will halt either when these generations are finished or when additional stopping requirements are met.

The method uses a crossover probability of 0.7 (70%) for genetic operations, which indicates that there is a 70% chance that chosen parent solutions will undergo crossover operations to produce new offspring. Through the combination of features from many parent solutions, this high crossover rate facilitates efficient exploration of new solution spaces. The implementation of a mutation probability of 0.3 (30%), which gives each component of a solution a 30% chance of experiencing random mutation, complements the crossover procedures. This mutation rate keeps the population diverse and keeps the algorithm from prematurely convergent being trapped in local optima. In order to store and preserve the best non-dominated solutions found during the search process, the algorithm keeps the archive size at 100, which is purposefully bigger than the population size. This bigger archive applies elitism to the optimization process and preserves solution variety.

The algorithm's main objectives are to optimize energy usage and latency. One important indicator of system service quality is the delay objective, which calculates how long it takes for user requests to be processed. In order to guarantee optimal performance and user satisfaction, this delay must be minimized. The system's fog nodes' overall energy usage is measured by the second objective, energy consumption. This objective is essential for controlling operational costs and preserving system efficiency. Since reducing latency may necessitate using more energy, and vice versa, the algorithm seeks the optimal solutions that strike a compromise between these two objectives. IBEA efficiently looks for Pareto-optimal solutions that offer the optimum trade-offs between service quality and energy efficiency using these parameter settings and objective functions.

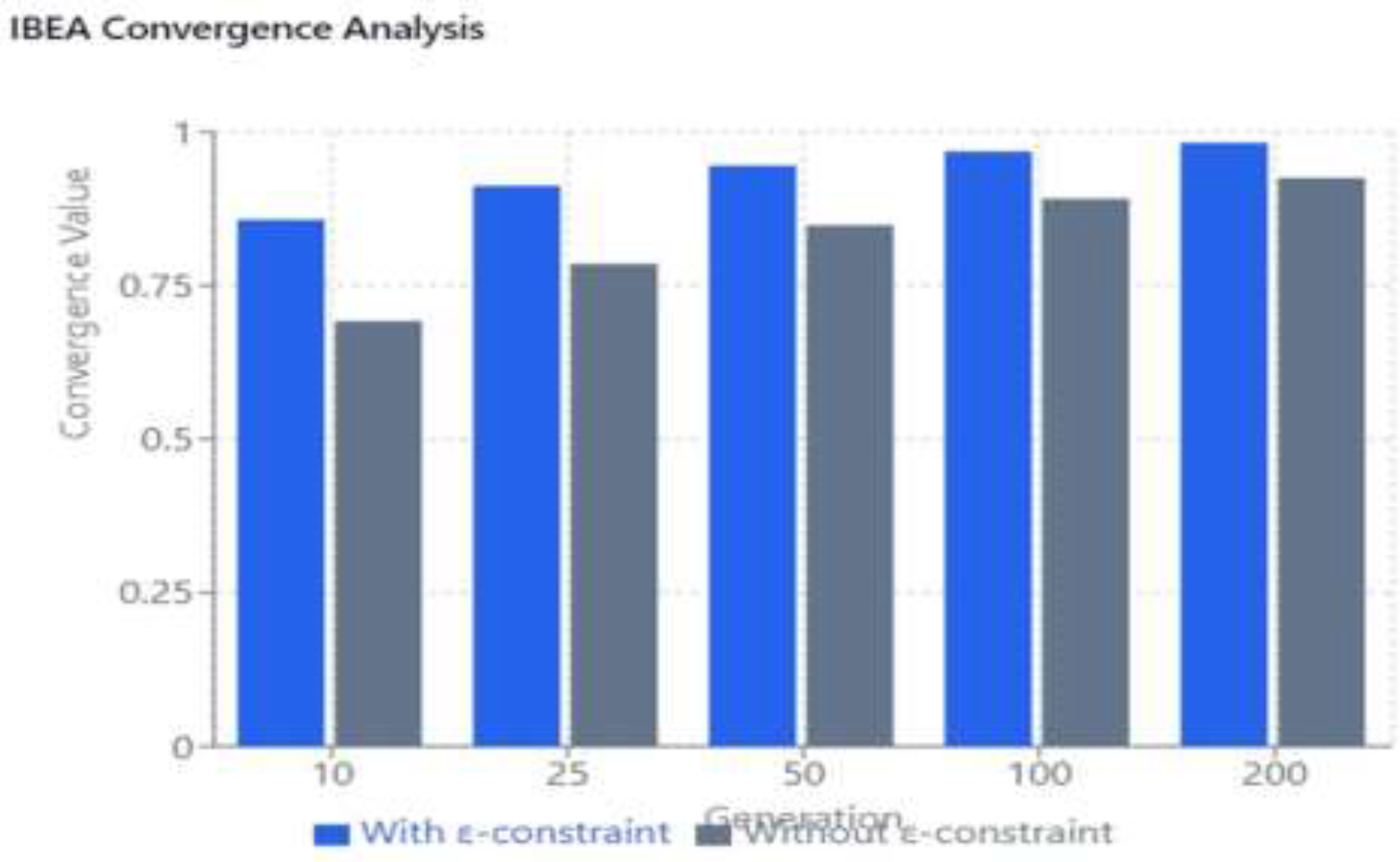

IBEA (Indicator-Based Evolutionary Algorithm) implementations with and without epsilon constraint integration for IoT fog computing optimization are compared for convergence values in

Table 3. It examined how IBEA optimization performed throughout generations and examined its convergence behavior in two scenarios: with and without ε-constraint integration. A thorough understanding of the optimization trajectory is provided by the study, which covers several generation checkpoints at 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 generations. The information provides strong evidence for how much ε-constraint integration improves IBEA's convergence properties.

The findings show that, as compared to the conventional IBEA implementation, applying the ε-constraint consistently produces better convergence values. With a noteworthy 23.8% improvement shown at generation 10, this increase is especially noticeable in the early phases of optimization. According to this, ε-constraint integration speeds up the first convergence stage, enabling the algorithm to find promising areas of the solution space more rapidly. While the relative improvement percentage steadily declines as optimization advances through consecutive generations, the improved version continues to outperform the standard implementation.

Interestingly, both strategies follow a same optimization pattern with declining results as the number of generations rises. Even in later generations, but with a reduced margin of improvement, the ε-constraint variant continuously retains improved convergence values. This consistent advantage suggests that the ε-constraint mechanism contributes to improved final solution quality in addition to accelerating early convergence. The data clearly shows that adding ε-constraint to IBEA improves the algorithm's performance, which is especially useful when quick convergence is required when computational resources are limited.

Figure 6 has been described as follows: distinct trends throughout several generational stages are revealed by the performance analysis. The system showed remarkable improvement rates in the early generation phase (10–25), ranging from 23.8% to 16.2%. The ε-constraint technique showed a notable advantage in first convergence. For the mid-generation period (50-100), both techniques showed consistent convergence patterns, and the improvement rate reduced to between 11.4% and 8.6%.

Both strategies reached their saturation thresholds, with the late generation phase (200) demonstrating a less significant but still noteworthy improvement of 6.2%. The main conclusions of this investigation show that the ε-constraint approach performed better in every generation. But as generations went by, there was a definite trend of declining returns in improvement. This implies that the ε-constraint method works best in the early stages of optimization, when it can take advantage of the greater potential for improvement.

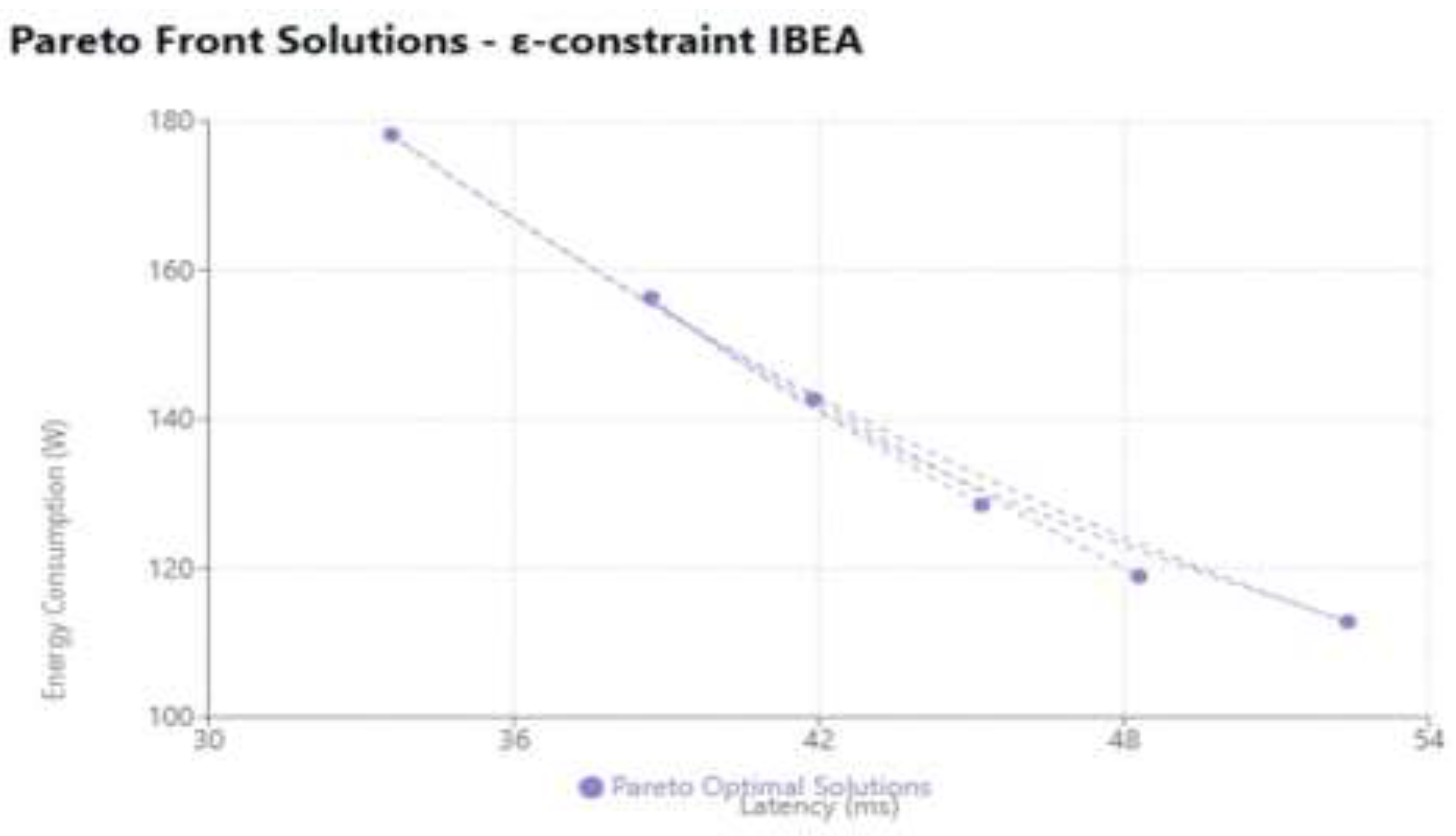

The Pareto-optimal solutions obtained by the ε-constraint IBEA method are displayed in

Table 4.

The table explains the following: For IoT fog computing systems, let's take a closer look at the Pareto-optimal solutions that the ε-constraint IBEA algorithm revealed. The basic trade-offs in fog computing resource management are illustrated by the solutions that are offered. When we examine Solution S4, we find that it has the lowest latency (33.6 ms), but it also uses the most energy (178.2 W). With five fog nodes and a high resource consumption of 88.5%, this solution has a "High" migration level, meaning that tasks are often redistributed among nodes to maintain optimal performance.

Solution S3, on the other hand, emphasizes energy efficiency and is at the other extreme of the spectrum. It has a greater latency of 52.4 ms and uses 112.8W of energy. This setup demonstrates how less system activity results in energy savings yet faster reaction times by using only three fog nodes, operating at a lower resource utilization of 68.9%, and maintaining a "Low" migration level. The middle-ground options (S1, S2, S5) exhibit trade-offs that are balanced. For example, Solution S5 uses four fog nodes and maintains 79.3% resource utilization with "Medium" migration, achieving moderate performance with 41.9ms latency and 142.7W energy usage. For situations when performance and energy efficiency are equally crucial, these systems provide attractive alternatives.

The connection between system setup and performance measures shows a distinct pattern. We observe a similar drop in latency but an increase in energy usage as the number of fog nodes rises from three to five. This makes sense since while more active nodes distribute processing more effectively, they also need more power. Likewise, greater latency performance is correlated with higher resource utilization percentages, albeit at the cost of increased energy consumption. The proposed methodology dynamic nature is revealed by the migration levels. Higher migration levels in solutions with more fog nodes suggest that tasks are redistributed more often to maintain peak performance. This demonstrates how the system actively distributes the load among the resources at its disposal, with the trade-off that greater migration levels often translate into increased energy consumption. No alternative solution is strictly superior in both objectives, as each Pareto front option reflects a non-dominated configuration. Whether system administrators need to balance energy efficiency and response time, or prioritize either, this provides them with a valuable options to select from.

Because of its interactive characteristics, the table's data presentation makes analysis simple. Sorting by any column makes it easier to see trends and connections among various data. While the alternating row improve readability when comparing different solutions, the accurate interpretation of the numbers is ensured by the clear presentation of units and consistent decimal formatting.

The scatter plot visualization that illustrates the Pareto front solutions for the optimization problem of the IoT fog computing system is explained in

Figure 7. The scatter plot efficiently illustrates the trade-off connection between two conflicting competing goals: energy consumption (measured in Watts) on the y-axis and system delay (measured in milliseconds) on the x-axis. The continuous Pareto front boundary is depicted by dotted lines connecting each point in the figure (S1 through S6), where each indicates a non-dominated solution discovered by the ε-constraint IBEA method.

While examining the extremes, Solution S4 is shown at the far left (33.6 ms, 178.2 W), indicating the highest energy usage but the best latency performance. Conversely, Solution S3, which has the most energy-efficient configuration but the worst latency, is located in the lower right section (52.4ms, 112.8W). The Pareto frontier, which is shown by the dotted line joining both locations, states that any improvement in one objective inevitably results in a decline in the other. Balanced solutions that provide various compromises between the two objectives, such as S2 (38.7ms, 156.3W), S5 (41.9ms, 142.7W), and S1 (45.2ms, 128.5W), are displayed in the center section of the plot. These points' distribution along the curve shows how the algorithm has discovered widely dispersed solutions throughout the objective space, giving system managers a variety of choices to suit various operational requirements.

The dotted connecting lines aid in visualizing the continuous character of the trade-off relationship, while the grid lines and axis labels offer distinct points of comparison for solutions. In order to clearly visualize the correlations between solutions, the chart's size and spacing have been improved. This makes it simple to spot patterns and make well-informed decisions regarding system configuration. The basic trade-off in fog computing systems is exemplified by the convex shape of the Pareto front, which is created by the dotted lines joining the solutions: improving latency performance invariably necessitates using more energy, and vice versa. Decision-makers may use this visualization as a valuable tool to comprehend the alternatives available and select configurations that best meet their unique needs for striking a balance between energy efficiency and performance.

5. Discussion about Results

The experiment outcomes are explained in this manner which makes it simple to discuss the selected algorithm. Remember that a multi-objective optimization solution is typically a collection of non-dominated solutions, as in the case of IBEA. The analysis is therefore taken into account concerning the optimization of two objectives as mentioned in section 3.

5.1. Justification about Selction of ε-epsilon Method

An advanced strategy for managing two-objective optimization in intricate distributed systems is the use of the ε-constraint method in combination with IBEA to optimize energy usage and service latency in fog computing. In distributed computing systems, this technique is especially efficient at striking a balance between the competing objectives of service performance and energy economy.

The inclusion of the ε-constraint technique is supported by its methodical approach to managing the inherent trade-offs between service delay and energy usage. Its strategic approach, which chooses energy consumption as the main optimization objective and turns service latency into a constraint with an ε parameter bound, is its main strength. This change keeps system performance within reasonable bounds while allowing for more accurate control over the optimization process. This method's effective constraint handling skills are one of its main advantages. By systematically varying ε values, the proposed approach allows for exact control over service latency and allows threshold modifications to meet varying QoS requirements. Finding and preserving ideal operating conditions is made simpler by the constraint transformation method, which gives more precise boundaries for feasible solutions.

The approach shows good fit with fog computing problems in the real world. The ε-constraint architecture successfully handles service delay restrictions, which are usually more clearly stated in SLAs than energy objectives. More aggressive energy optimization within preset delay limitations is made possible by this alignment, which reflects real-world operational requirements in fog computing settings.

The optimization process benefits greatly from the interaction with IBEA. The ε-constraint technique is enhanced by IBEA's indicator-based fitness assessment, which offers a more detailed analysis of solutions that fall inside the feasible region. Better solution space exploration is made possible by this combination, which also strictly adheres to delay limitations. In IBEA, the binary quality indicators are essential for preserving solution diversity while concentrating on energy optimization.

From the perspective of implementation, the method has a number of useful benefits. Systematic ε-epsilon method value change simplifies parameter tuning, and explicit violation detection procedures guarantee constraint compliance. The method is more appropriate for real-world applications since it exhibits lower computing complexity when compared to conventional multi-objective approaches. Through a number of methods, the technique greatly improves the quality of the solutions. Through systematic ε variation, it increases solution distribution along the Pareto front and focuses optimization efforts into viable regions to produce improved convergence characteristics. A more thorough optimization landscape is provided by the method's improved capacity to identify extreme solutions at different delay constraint levels.

From Operationally point of view, the approach has certain benefits in real-world deployment scenarios. It facilitates simpler integration with current service level agreements and offers direct translation to real-world fog computing applications where latency limitations are crucial. System administration and maintenance are made easier by the user-friendly parameter modification method. Setting baseline ε values based on proposed approach needs is the first step in the structured implementation process. This is followed by gradual modification to examine various trade-off points. While solution assessment employs binary indicators to guarantee constraint compliance, IBEA optimization concentrates on energy minimization inside each ε-epsilon method bound.

The approach shows strong performance in managing dynamic operational circumstances. Through adaptive ε-epsilon modification, it efficiently handles workload variations and preserves solution viability across a range of network scenarios. The method allows for systematic investigation of the complete set of efficient solutions and offers explicit violation metrics for constraint management. Key issues in fog computing optimization are successfully addressed by this proposed methodology, such as balancing competing objectives, upholding stringent service quality guarantees, adapting to changing operational conditions, and giving system administrators clear control mechanisms.

5.2. Novelty and Significant Innovation in the Methodology

Enough innovation is shown by the use of the Indicator-Based Evolutionary Algorithm (IBEA) for service request assignment in fog computing with two-objective optimization to tackle the intricate problems of resource allocation in fog environments. By moving compute and data storage closer to the network's edge, fog computing, an extension of cloud computing, lowers latency and enhances service quality for Internet of Things (IoT) applications [

41]. However, because fog nodes are diverse and IoT devices have dynamic demands, effectively allocating resources in fog computing is still a significant challenge. In contrast to conventional scheduling methods, the application of IBEA to this problem area provides a novel approach. Because fog computing resource allocation is multi-objective problem. Hence, IBEA can handle it better than simple heuristics or single-objective optimization techniques, optimizing for both resource use and minimal latency at the same time [

42]. In fog environments, where cost and performance must be balanced, this dual-objective approach is essential.

In this regard, IBEA's indicator-based selection process offers a distinct benefit. IBEA can more successfully negotiate the intricate trade-offs between resource efficiency and latency reduction by employing a quality indicator to direct the selection process. This is especially useful in fog computing, where a highly dimensional solution space is created by the variety of service requests and fog node capabilities [

43]. Additionally, IBEA's evolving nature enables it to adjust to the dynamic characteristics of fog computing environments. IBEA can adapt its solutions to changing circumstances and retain optimality as service requirements and resource availability change over time. Compared to static allocation techniques, which may easily become less effective in actual fog deployments, this flexibility is a major advantage [

35]. The ability of IBEA to integrate domain-specific knowledge into the optimization process further demonstrates the originality of its use in this application.

Researchers may encode fog computing-specific limitations and preferences, including giving priority to particular service types or taking energy usage into consideration in resource-constrained edge devices, by carefully crafting the indicator function [

44]. Furthermore, a variety of Pareto-optimal solutions may be discovered using IBEA's population-based methodology, giving system administrators a variety of trade-off choices. In fog computing, where various deployment scenarios may place varying priorities on latency or resource efficiency, this is particularly valuable [

45]. To sum up, using IBEA to allocate service requests in fog computing provides a novel and exciting way to tackle the difficult problems of resource distribution in these dispersed environments. IBEA is a comprehensive solution that may greatly improve the state of the art in fog computing resource management by utilizing its multi-objective optimization capabilities, adaptive nature, and flexibility in adding domain-specific information.

5.3 Practical Implications of Proposed Approch

The proposed technique of improving energy usage and service latency in fog computing service request assignment by combining the ε-constraint method with the Indicator-Based Evolutionary Algorithm (IBEA) has important practical implications.

Better Resource Utilization: This method makes fog computing systems run more effectively by reducing energy consumption and service latency at the same time. Practically speaking, this translates into improved use of scarce resources at the network's edge, which is essential for managing the growing needs of Internet of Things devices and applications.

Improved Quality of Service (QoS): End users will respond more quickly when service delays are kept to a minimum. This is especially crucial for latency-sensitive applications where even milliseconds of delay can have serious repercussions, including industrial control systems, augmented reality, and driverless cars.

Energy Efficiency: Reducing energy use is in line with the increased need for sustainable IT infrastructure and green computing. This can result in lower operating costs and a smaller carbon impact for businesses using fog computing technologies.

Adaptability to Dynamic settings: In fog computing settings, the IBEA algorithm can adjust to shifting conditions according to the ε-constraint technique. This is essential in real-world situations when user demands, network conditions, and resource availability all change often.

Scalability: This method's capacity to manage extensive optimization issues gains value as fog computing deployments get bigger and more sophisticated. It can effectively control the distribution of resources among a large network of edge devices and fog nodes.

System Administrator Decision Support: This method offers system administrators a variety of trade-off possibilities through the Pareto-optimal solutions it produces. This is especially helpful in real-world situations where performance and energy efficiency may be prioritized differently depending on the time of day, workload, or organizational goals.

Managing Complex restrictions: Complex restrictions pertaining to hardware limits, network topology, and service level agreements are frequently present in real-world fog computing systems. The ε-constraint technique successfully bridges the gap between theoretical models and real-world implementations by managing these restrictions.

Load Balancing: This method can improve load balancing across fog nodes by improving service request assignment. This has real-world effects on distributed computing environments' overall performance, fault tolerance, and system stability.

Cost Optimization: Cost optimization is implicitly addressed by the simultaneous emphasis on energy usage and service latency. While less service delay can result in higher customer satisfaction and possibly more income for service providers, less energy use decreases operating expenses.

Applicability to Emerging Technologies: This strategy works well for innovations like 5G and beyond, where fog computing integration is anticipated to be essential. It offers a structure for handling these next-generation networks' intricate trade-offs.

The mathematical computation of the problem (using IBEA and the ε-constraint approach) directly tackles practical problems in fog computing, demonstrating the relationship between theoretical elements and real-world implementations. The practical objectives of performance optimization and energy efficiency, which are crucial in real-world deployments, are addressed by using the theoretical underpinnings of multi-objective optimization. In conclusion, our method contributes significantly to the theoretical and applied facets of the area by addressing present fog computing challenges and establishing the foundation for next developments in distributed computing resource management

6. Conclusion and Future Work

Mostly, the IBEA algorithm generated the values of the optimization for the two objectives mentioned above. IBEA, however, achieved better outcomes in the service spread and network latency when the objectives were analyzed independently. Additionally, IBEA gained a larger solution space, giving the system administrator more freedom to choose a solution from the available ones by taking various factors or preferences into account.

The benefits of the IBEA required longer execution periods, both in terms of the number of generations and the duration of each generation's execution time. In conclusion, IBEA could generate optimal results concerning both objectives and generate varied solution space. The study of a hybrid optimization algorithm that runs different optimization algorithms at once and blends the different solution sets has provided new avenues for future research. It is also possible to research and contrast different metaheuristics, such as ant colony optimization (ACO), genetic algorithm (GA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO). Finally, it is interesting to observe how various fog organizations may apply analogous evolutionary strategies. The benefit of the epsilon-constraint approach, as demonstrated by our studies, is its adaptability to non-convex Pareto fronts, which can present difficulties for more conventional techniques like weighted sum approaches. Through the adjustment of the ε values, professionals may methodically investigate various areas of the Pareto front, guaranteeing that an extensive range of solutions are being evaluated.

The method's robustness has been further enhanced by recent improvements, such as the addition of surplus and slack variables, which solve problems by finding effective solutions and offer more adaptive constraint handling. Furthermore, to enhance efficiency in resolving intricate multi-objective problems, the epsilon-constraint technique has been effectively hybridized with evolutionary algorithms, such as cultured differential evolution. By combining the objectives of evolutionary approaches with mathematical programming, this integration enables iterative solution refining. Thus, the epsilon-constraint technique not only helps find the optimal solutions but also improves the general efficacy and efficiency of multi-objective optimization procedures in a variety of applications.

The performance of IBEA is greatly improved by the epsilon-constraint approach, which takes care of several important multi-objective optimization aspects. By providing explicit constraints on objective functions, it primarily enhances convergence qualities while preserving variety along the Pareto front. The approach ensures improved constraint management while offering fine-grained control over the search direction, enabling targeted investigation of certain regions of interest. Additionally, it improves the IBEA quality indicators, leading to more accurate convergence measurements and relevant solution comparisons. The epsilon-constraint method is especially useful for real-world optimization problems where effective resource use and clear trade-off visualization are crucial since it streamlines parameter adjustment and increases algorithm resilience in real-world implementations.

This proposed strategy successfully directs the search towards Pareto-optimal solutions by allowing the algorithm to concentrate on identifying solutions that not only satisfy but also exceed these thresholds. To make sure that the most important performance parameters are given priority, this feature enables more effective service placement and task scheduling in the context of IoT fog computing, where resources are frequently limited and requirements are constantly changing. The epsilon constraint method also enhances the diversity of solutions produced by IBEA. The technique promotes investigation of various areas of the solution space by methodically altering epsilon values, which results in a larger collection of viable solutions. This is especially helpful in fog computing situations where diverse application needs and heterogeneous resources call for flexible and adaptive optimization techniques. Thus, the IBEA and epsilon constraint method together not only enhance the quality of the solutions but also provide resilience to the uncertainties present in IoT contexts. Further study may focus on creating many objectives optimization using NSGA-III algorithms using hypervolume metric.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Methodology: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri; Experiments Design: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri; Validation: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri; Analysis and investigation: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri; Writing—review and editing: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri; Supervision: Muhammad Abid Jamil, Mohammed A. Al Ghamdi and Sultan H. Almotiri. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number: IFP22UQU4250002DSR216.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the datasets.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qiao, W.; Zhao, S.; Deng, H. Multi-Layer Semantic Middleware for Cross-Domain Internet of Things. 2021, 1993, 012028. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, L.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent Edge Computing for IoT-Based Energy Management in Smart Cities. IEEE Network 2019, 33, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Afzal, B.; Alvi, S.A.; Shah, G.A.; Mahmood, W. Energy Efficient Context Aware Traffic Scheduling for IoT Applications. 2017, 62, 101–115.

- Sajid, A.; Sonbul, O.; Rashid, M.; Zia, M.Y.I. A Hybrid Approach for Efficient and Secure Point Multiplication on Binary Edwards Curves. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 5799. [CrossRef]

- Bomnale, A.; Malgaonkar, S. Power optimization in wireless sensor networks. In2018 International conference on communication information and computing technology (ICCICT) 2018 Feb 2 (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Singh, J.; Kaur, R.; Singh, D. A Survey and Taxonomy on Energy Management Schemes in Wireless Sensor Networks. Journal of Systems Architecture 2020, 111, 101782.

- Ma, K.; Bagula, A.; Nyirenda, C.N.; Ajayi, O. An IoT-Based Fog Computing Model. Sensors 2019, 19, 2783.

- Rashid, M.; Hazzazi, M.M.; Khan, S.Z.; Alharbi, A.R.; Sajid, A.; Aljaedi, A. A Novel Low-Area Point Multiplication Architecture for Elliptic-Curve Cryptography. Electronics 2021, 10, 2698.

- Behera, R.K.; Reddy, K.H.; Roy, D.S. A novel context migration model for fog-enabled cross-vertical IoT applications. In International Confer,ence on Innovative Computing and Communications: Proceedings of ICICC 2019, Volume 2 2019 Nov 17 (pp. 287-295). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Reddy, K.H.K.; Behera, R.K.; Chakrabarty, A.; Roy, D.S. A Service Delay Minimization Scheme for QoS-Constrained, Context-Aware Unified IoT Applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 10527–10534. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, C.; Lera, I.; Juiz, C. Evaluation and Efficiency Comparison of Evolutionary Algorithms for Service Placement Optimization in Fog Architectures. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 97, 131–144. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Sood, S.K. Cloud-Fog Based Framework for Drought Prediction and Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2020, 32, 273–289. [CrossRef]

- Skarlat, O.; Nardelli, M.; Schulte, S.; Borkowski, M.; Leitner, P. Optimized IoT Service Placement in the Fog. 2017, 11, 427–443.

- Sun, Y.; Lin, F.; Xu, H. Multi-Objective Optimization of Resource Scheduling in Fog Computing Using an Improved NSGA-II. Wireless Personal Communications 2018, 102, 1369–1385.

- Guerrero, C.; Lera, I.; Juiz, C. Evaluation and Efficiency Comparison of Evolutionary Algorithms for Service Placement Optimization in Fog Architectures. Future Generation Computer Systems 2019, 97, 131–144.

- Kaur, A.; Sood, S.K. Artificial intelligence-based model for drought prediction and forecasting. The Computer Journal. 2020 Nov;63(11).

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, L.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent edge computing for IoT-based energy management in smart cities. IEEE network. 2019 Mar 27;33(2):111-7.

- Roy, D.S.; Behera, R.K.; Reddy, K.H.K.; Buyya, R. A Context-Aware Fog Enabled Scheme for Real-Time Cross-Vertical IoT Applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 2400–2412.

- Shi, Y.; Ding, G.; Wang, H.; Roman, H.E.; Lu S. The fog computing service for healthcare. In2015 2nd International symposium on future information and communication technologies for ubiquitous healthCare (Ubi-HealthTech) 2015 May 28 (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Yi, S.; Li, C.; Li, Q. A survey of fog computing: concepts, applications and issues. InProceedings of the 2015 workshop on mobile big data 2015 Jun 21 (pp. 37-42).

- Suárez-Albela, M.; Fernández-Caramés, T.M.; Fraga-Lamas, P.; Castedo, L. A Practical Evaluation of a High-Security Energy-Efficient Gateway for IoT Fog Computing Applications. Sensors 2017, 17, 1978.

- Bonomi, F.; Milito, R.; Natarajan, P.;, Zhu, J. Fog computing: A platform for internet of things and analytics. Big data and internet of things: A roadmap for smart environments. 2014:169-86.

- Yousefpour, A.; Ishigaki, G.; Jue, J.P. Fog computing: Towards minimizing delay in the internet of things. In2017 IEEE international conference on edge computing (EDGE), 2017 Jun 25 (pp. 17-24). IEEE.

- Lee, K.; Kim, D.; Ha, D.; Rajput, U.; Oh, H. On security and privacy issues of fog computing supported Internet of Things environment. In2015 6th International Conference on the Network of the Future (NOF), 2015 Sep 30 (pp. 1-3). IEEE.

- Alsuwat, E.; Solaiman, S.; Alsuwat, H. Concept Drift Analysis and Malware Attack Detection System Using Secure Adaptive Windowing. Cmc-computers Materials & Continua 2023, 75, 3743–3759. [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Lillethun, D.; Ramachandran, U.; Ottenwälder, B.; Koldehofe, B. Mobile fog: A programming model for large-scale applications on the internet of things. In Proceedings of the second ACM SIGCOMM workshop on Mobile cloud computing 2013 Aug 16 (pp. 15-20).

- Mahmud, R.; Kotagiri, R.; Buyya, R. Fog computing: A taxonomy, survey and future directions. Internet of everything: algorithms, methodologies, technologies and perspectives. 2018:103-30. [CorssRef].

- Sajid, A.; Sonbul, O.S.; Rashid, M.; Jafri, A.R.; Arif, M.; Zia, M.Y. A Crypto Accelerator of Binary Edward Curves for Securing Low-Resource Embedded Devices. Applied Sciences. 2023 Jul 26;13(15):8633. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, F.A.; Khan, I.; Zareei, M.; Zeb, A.; Waheed, A. Resource Allocation and Optimization in Device-to-Device Communication 5G Networks. Computers, Materials & Continua. 2021 Oct 1;69(1). [CrossRef]

- 8 May.

- Jamil, M.A.; Nour, M.K. Managing Software Testing Technical Debt Using Evolutionary Algorithms. Computers, Materials & Continua. 2022 Oct 1;73(1). [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.A.; Alsadie, D.; Nour, M.K.; Awang, Abu Bakar N.S. Maintain Optimal Configurations for Large Configurable Systems Using Multi-Objective Optimization. Computers, Materials & Continua. 2022 Nov 1;73(2). [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.A.; Nour, M.K.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Hussain; M.J.; Hussaini, S.M.; Naseer, A. Software Product Line Maintenance Using Multi-Objective Optimization Techniques. Applied Sciences. 2023 Aug 6;13(15):9010. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.A.; Nour, M.K.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Hussain; M.J.; Hussaini, S.M.; Naseer, A. Adaptive Test Suits Generation for Self-Adaptive Systems Using SPEA2 Algorithm. Applied Sciences. 2023 Oct 15;13(20):11324. [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, S.M.; Razak, T.A.; Jamil, M.A. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm to Optimize IoT Based Scheduling Problem Using (NSGA-II Algorithm). Journal of Intelligent Systems & Internet of Things. 2024 Jun 1;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Saranya, M.; Pabitha, P. Hybrid Multi-objective Harris-Hawks and Moth-Flame Optimization Algorithm for Efficient Task Offloading strategy in IoT-Based Fog Computing Applications. In2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS) 2024 Apr 18 (Vol. 1, pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mokni, I.; Yassa, S. A multi-objective approach for optimizing IoT applications offloading in fog–cloud environments with NSGA-II. The Journal of Supercomputing. 2024 Sep 25:1-39. [CrossRef]

- Apat, H.K.; Sahoo, B.; Goswami, V.; Barik, R.K. A hybrid meta-heuristic algorithm for multi-objective IoT service placement in fog computing environments. Decision Analytics Journal. 2024 Mar 1;10:100379. [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, J.F.; Gendreau, M.; Potvin, J.Y. An exact ϵ-constraint method for bi-objective combinatorial optimization problems: Application to the Traveling Salesman Problem with Profits. European journal of operational research. 2009 Apr 1;194(1):39-50.

- Mesquita-Cunha M.; Figueira, J.R.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P. New ϵ-constraint methods for multi-objective integer linear programming: A Pareto front representation approach. European Journal of Operational Research. 2023 Apr 1;306(1):286-307.

- Amoon, M.; Bahaa-Eldin, A.M.; El-Bahnasawy, N.A. Resource Allocation Strategy in Fog Computing: Task Scheduling in Fog Computing Systems. Journal of Communication Sciences and Information Technology. 2023 Jul 1;1(1):1-1. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chang, W.Y.; Chiu, T.L.; Chiang, M.C.; Tsai, C.W. SEFSD: an effective deployment algorithm for fog computing systems. Journal of Cloud Computing. 2023 Jul 15;12(1):105. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, C.; Zheng, A.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y. Fog computing resource-scheduling strategy in IoT based on artificial bee colony algorithm. Electronics. 2023 Mar 23;12(7):1511. [CrossRef]

- Binh, H.T.; Anh, T.T.; Son, D.B.; Duc, P.A.; Nguyen, B.M. An evolutionary algorithm for solving task scheduling problem in cloud-fog computing environment. InProceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, 2018, Dec 6 (pp. 397-404).

- Talavera, F.; Lera, I.; Juiz, C.; Guerrero, C. Optimizing fog colony layout and service placement through genetic algorithms and hierarchical clustering. Expert Systems with Applications. 2024 Jun 4:124372. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).