Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

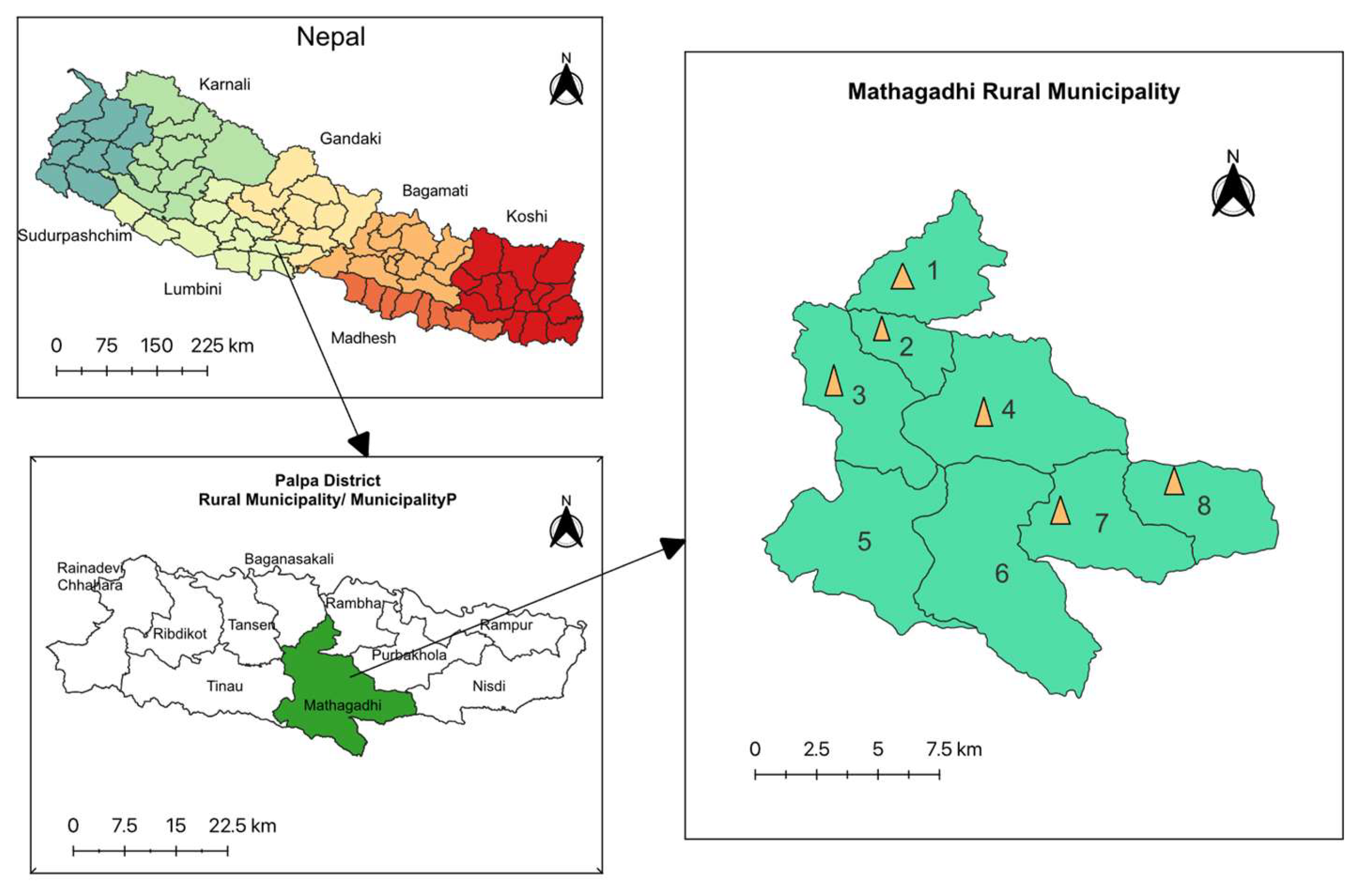

2.1. Study Site

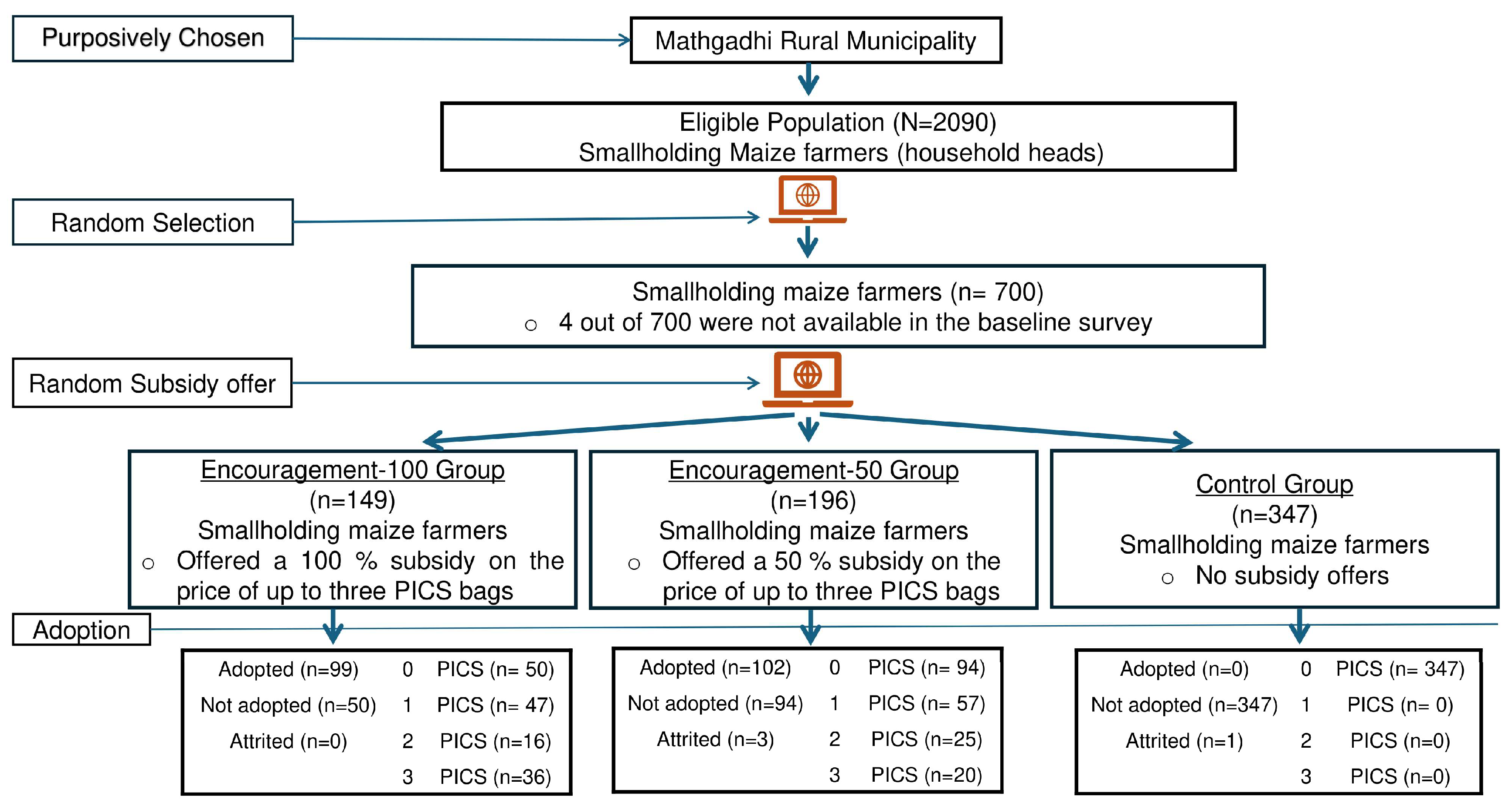

2.2. Data and Sampling Strategy

2.3. Summary statistics

2.4. Balance check

2.5. Experimental Design

2.5.1. Treatment variable:

2.5.2. Instrumental variables

2.5.3. Outcomes:

2.5.4. Compliance proportion:

2.6. Estimation strategy

3. Results

3.1. First stage the impact of subsidy offers on the PICS bag adoption

3.2. Impact of the PICS bags adoption on storage quantity

3.3. Impact of the PICS bags adoption on post-harvest storage losses

3.4. Impact on PICS bags adoption and outcomes of interest:100% vs 50% subsidy encouragement

3.5. Instrument Validity

3.6. Robustness Check:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Descriptions |

| Demographics | |

| Age | Age of respondents |

| Education (year) | Education year of respondents |

| Gender | Gender of respondents 1= male; 0= female |

| Family size | Total number of members in household |

| Economical (Income in thousands in Nepali Rupee-NPR) | |

| Family inocme | Average yearly income of household |

| Cereal income | Average yearly income of household from cereal crops |

| Cash crop income | Average yearly income of household from cash crops |

| Forest income | Average yearly income of household from forest |

| Off-farm income | Average yearly income of household from other sectors excluding agricuture |

| Livestock income | Average yearly income of household from livestock |

| Agricultural | |

| Agri-experience (year) | Experiences year of respondent in agriculture |

| Agri-land size (ropani) | Total area of agriculture land of household in ropani (1 ha= 19.66 ropani) |

| Maize production quantity (kg) | Total quantity of maize produced in the previous year. |

| Maize cultivated area (ropani) | Total area of maize cultivated land in the year 2023 in ropani (1 ha= 19.66 ropani) |

| Post-harvest management | |

| Storage period (month) | Storage period of maize in month |

| Insects (dummy) | Household having problem by insects such as weevil 1= Yes; 0= No |

| Moths (dummy) | Household having problem by insects such as moths 1= Yes; 0= No |

| Storage Loss (kg) | quantity of maize losses during the storage in Kg |

| New technology (dummy) | Famers who have experiences of new technology for storage 1 = Yes; 0= No |

| Outcome variables | |

| Storage quantity using PICS bag | Total quantity of maize stored in hermetic air- tight bags in kg. |

| Post-harvest storage losses | Total storage losses self-reported by households |

| Nos. of PICS bag | Control Group | Encouragement-100 Group | Encouragement-50 Group | |||

| Receive | Adopt | Receive | Adopt | Receive | Adopt | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| 0 | 347 | 347 | 12 | 50 | 39 | 94 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 47 | 26 | 57 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 16 | 31 | 25 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 73 | 36 | 100 | 20 |

| 100% Subsidy offer Encouragment-100 Vs Control Group |

50% Subsidy offer Encouragment-50 Vs Control Group |

100% Subsidy offer Encouragment-100 Vs Encouragment-50 |

|

| Weak Instruments test | |||

| F-statistic | 199.85 | 129.47 | 12.25 |

| F-probability | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 |

| Degree of Freedom | 490 | 537 | 339 |

| Partial R- Saqured | 0.2897 | 0.1943 | 0.0349 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIML | GMM | LIML | GMM | |

| Variables | Storage quantity using PICS bags | Storage quantity using PICS bags | Storage quantity using PICS bags | Storage quantity using PICS bags |

| Nos. of PICS bags | 42.86***(2.67) | 42.86*** (2.67) |

39.20*** (1.36) |

39.20*** (1.36) |

| Observations | 496 | 496 | 543 | 543 |

| R-squared | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Encouragement (subsidy offer) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| LIML | GMM | LIML | GMM | |

| Variables | Post-harvest storage loss (kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (kg) |

| Nos. of PICS bags | -10.02** (4.00) |

(4.00) | (7.12) | -9.37 (7.12) |

| Observations | 496 | 496 | 543 | 543 |

| R-squared | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Encouragement (subsidy offer) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% |

References

- FAO State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FOOD & AGRICULTURE ORG, 2019; ISBN 9789251317891.

- Delgado, L.; Schuster, M.; Torero, M. Food Losses in Agrifood System: What We Know. Annu Rev Resour Economics 2023, 15(41-62), doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-072722. [CrossRef]

- FAO How to Feed the World in 2050 Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/wsfs/docs/expert_paper/How_to_Feed_the_World_in_2050.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Godfray, H.C.J. The Challenge of Feeding 9-10 Billion People Equitably and Sustainably. In Proceedings of the Journal of Agricultural Science; Cambridge University Press, December 12 2014; Vol. 152, pp. S2–S8.

- Kumar, D.; Kalita, P. Reducing Postharvest Losses during Storage of Grain Crops to Strengthen Food Security in Developing Countries. Foods 2017, 6, 1–22, doi:10.3390/foods6010008. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Tirivayi, N. The Impacts of Postharvest Storage Innovations on Food Security and Welfare in Ethiopia. Food Policy 2018, 75, 52–67, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.01.004. [CrossRef]

- Brander, M.; Bernauer, T.; Huss, M. Improved On-Farm Storage Reduces Seasonal Food Insecurity of Smallholder Farmer Households – Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in Tanzania. Food Policy 2021, 98, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101891. [CrossRef]

- Omotilewa, O.J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Ainembabazi, J.H.; Shively, G.E. Does Improved Storage Technology Promote Modern Input Use and Food Security? Evidence from a Randomized Trial in Uganda. J Dev Econ 2018, 135, 176–198, doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.006. [CrossRef]

- Chegere, M.J. Post-Harvest Losses Reduction by Small-Scale Maize Farmers: The Role of Handling Practices. Food Policy 2018, 77, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.05.001. [CrossRef]

- Channa, H.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Feleke, S.; Abdoulaye, T. Overcoming Smallholder Farmers’ Post-Harvest Constraints through Harvest Loans and Storage Technology: Insights from a Randomized Controlled Trial in Tanzania. J Dev Econ 2022, 157, doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102851. [CrossRef]

- Murdock, L.L.; Margam, V.; Baoua, I.; Balfe, S.; Shade, R.E. Death by Desiccation: Effects of Hermetic Storage on Cowpea Bruchids. J Stored Prod Res 2012, 49, 166–170, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2012.01.002. [CrossRef]

- Abass, A.B.; Ndunguru, G.; Mamiro, P.; Alenkhe, B.; Mlingi, N.; Bekunda, M. Post-Harvest Food Losses in a Maize-Based Farming System of Semi-Arid Savannah Area of Tanzania. J Stored Prod Res 2014, 57, 49–57, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2013.12.004. [CrossRef]

- World Bank MISSING FOOD: The Case of Postharvest Grain Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa, Report No. 60371-AFR; Washington, DC 20433, 2011;

- Shiferaw, B.; Prasanna, B.M.; Hellin, J.; Bänziger, M. Crops That Feed the World 6. Past Successes and Future Challenges to the Role Played by Maize in Global Food Security. Food Secur 2011, 3, 307–327.

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global Maize Production, Consumption and Trade: Trends and R&D Implications. Food Secur 2022, 14, 1295–1319.

- Bhandari, G.; Achhami, B.B.; Karki, T.B.; Bhandari, B.; Bhandari, G. Survey on Maize Post-Harvest Losses and Its Management Practices in the Western Hills of Nepal. Journal of Maize Research and Development 2015, 1, 98–105, doi:10.5281/zenodo.34288. [CrossRef]

- MoALD Statistical Information on Nepalese Agriculture 2078/79 (202122); Shinhadarbar, Kathamandu, 2023;

- MoALD Selected Indicators of Nepalese Agriculture; Shinhadarbar Kathmandu, 2023;

- MOF Economic Survey Fiscal Year 2023-24; Sinhdurbar, Kathamandu, 2024;

- Timsina, K.P.; Ghimire, Y.N.; Lamichhane, J. Maize Production in Mid Hills of Nepal: From Food to Feed Security. Journal of Maize Research and Development 2016, 2, 20–29, doi:10.3126/jmrd.v2i1.16212. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, I.P.; Shrestha, K.B.; Shivakoti, G.P. RS3839_Existing Farmer Practices of Maize Storage in the Eastern and Mid-Western Hills of Nepal.; Khajura, Banke, 2002;

- Upadhayay IP; Shrestha KB; Shivakoti GP RS4182_A Literature Review On Post-Harvest Losses of Maize with Emphasis on Storage Losses..Pdf-1487049461; Khajura, Banke, 2002;

- Paneru, R.B.; Paudel, G.P.; Thapa, R.B. DETERMINANTS OF POST-HARVEST MAIZE LOSSES BY PESTS IN MID HILLS OF NEPAL. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch 2018, 3, 110–118.

- PMAMP Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project: Project Implementation Manual. Prime Minister Agriculture Modernization Project 2020.

- PMAMP Annual Program and Progress Report (Fiscal year 2022/23); 2024;

- MoAD Agriculture Development Strategy (ADS). Government of Nepal, Ministry of Agriculture Development 2015, 1.

- Flock, J.H. Purdue E-Pubs Factors That Influence the Adoption of Hermetic Storage, Evidence From Nepal; 2015;

- Kandel, P.; Kharel, K.; Njoroge, A.; Smith, B.W.; Díaz-Valderrama, J.R.; Timilsina, R.H.; Paudel, G.P.; Baributsa, D. On-Farm Grain Storage and Challenges in Bagmati Province, Nepal. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, doi:10.3390/su13147959. [CrossRef]

- Ndaghu, N.N.; Abdoulaye, T.; Mustapha, A.; Choumbou Raoul Fani, D.; Tabetando, R.; Udeme Henrietta, U.; Lucy Kamsang, S. Gender Differentiation on the Determinants and Intensity of Adoption of Purdue Improved Cowpea Storage (PICS) Bags in Northern Nigeria. Heliyon 2023, 9, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23026. [CrossRef]

- Benimana, G.U.; Ritho, C.; Irungu, P. Assessment of Factors Affecting the Decision of Smallholder Farmers to Use Alternative Maize Storage Technologies in Gatsibo District-Rwanda. Heliyon 2021, 7, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08235. [CrossRef]

- Alemu, G.T.; Nigussie, Z.; Haregeweyn, N.; Berhanie, Z.; Wondimagegnehu, B.A.; Ayalew, Z.; Molla, D.; Okoyo, E.N.; Baributsa, D. Cost-Benefit Analysis of on-Farm Grain Storage Hermetic Bags among Small-Scale Maize Growers in Northwestern Ethiopia. Crop Protection 2021, 143, doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105478. [CrossRef]

- Manda, J.; Feleke, S.; Mutungi, C.; Tufa, A.H.; Mateete, B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.D. Assessing the Speed of Improved Postharvest Technology Adoption in Tanzania: The Role of Social Learning and Agricultural Extension Services. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2024, 202, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123306. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Z.; Ma, W.; Valentinov, V. The Effect of Cooperative Membership on Agricultural Technology Adoption in Sichuan, China. China Economic Review 2020, 62, doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2019.101334. [CrossRef]

- Baributsa, D.; Njoroge, A.W. The Use and Profitability of Hermetic Technologies for Grain Storage among Smallholder Farmers in Eastern Kenya. J Stored Prod Res 2020, 87, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2020.101618. [CrossRef]

- Channa, H.; Chen, A.Z.; Pina, P.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Stein, D. What Drives Smallholder Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for a New Farm Technology? Evidence from an Experimental Auction in Kenya. Food Policy 2019, 85, 64–71, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.03.005. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.B.; Murdock, L.L.; Baributsa, D. Storage of Maize in Purdue Improved Crop Storage (PICS) Bags. PLoS One 2017, 12, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168624. [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Akrofi, G.; Maier, D.E.; White, W.S.; Akowuah, J.O.; Bartosik, R.; Cardoso, L. Effectiveness of Hermetic Bag Storage Technology to Preserve Physical Quality Attributes of Shea Nuts. J Stored Prod Res 2023, 101, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2023.102086. [CrossRef]

- Odjo, S.; Burgueño, J.; Rivers, A.; Verhulst, N. Hermetic Storage Technologies Reduce Maize Pest Damage in Smallholder Farming Systems in Mexico. J Stored Prod Res 2020, 88, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2020.101664. [CrossRef]

- Ng’ang’a, J.; Mutungi, C.; Imathiu, S.; Affognon, H. Effect of Triple-Layer Hermetic Bagging on Mould Infection and Aflatoxin Contamination of Maize during Multi-Month on-Farm Storage in Kenya. J Stored Prod Res 2016, 69, 119–128, doi:10.1016/j.jspr.2016.07.005. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Pullabhotla, H.K.; Baylis, K. The Economics of Reducing Food Losses: Experimental Evidence from Improved Storage Technology in India. Food Policy 2023, 117, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2023.102442. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Francis, E.; Robinson, J. Grain Today, Gain Tomorrow: Evidence from a Storage Experiment with Savings Clubs in Kenya. J Dev Econ 2018, 134, 1–15, doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.04.001. [CrossRef]

- Chegere, M.J.; Söderbom, M.; Eggert, H. The Effects of Storage Technology and Training on Post-Harvest Losses, Practices and Sales: Evidence from Small-Scale Farms in Tanzania. Econ Dev Cult Change 2022, 70, 729–761, doi:10.1086/713932. [CrossRef]

- Mendola, M. Agricultural Technology Adoption and Poverty Reduction: A Propensity-Score Matching Analysis for Rural Bangladesh. Food Policy 2007, 32, 372–393, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.07.003. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Adoption and Income Effects of New Agricultural Technology on Family Farms in China. PLoS One 2022, 17, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267101. [CrossRef]

- Negede, B.M.; De Groote, H.; Minten, B.; Voors, M. Does Access to Improved Grain Storage Technology Increase Farmers’ Welfare? Experimental Evidence from Maize Farming in Ethiopia. J Agric Econ 2023.

- Nindi, T.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Bauchet, J. Incentive Mechanisms to Exploit Intraseasonal Price Arbitrage Opportunities for Smallholder Farmers: Experimental Evidence from Malawi. Am J Agric Econ 2023, doi:10.1111/ajae.12376. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Imbens, G.W.; Rubin, D.B. Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables. J Am Stat Assoc 1996, 91, 444–455, doi:10.1080/01621459.1996.10476902. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mastering ’Metrics: The Path from Cause to Effect; 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 2014; ISBN 978-0-691-15284-4.

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricistís Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey, 2009;

- Imbens, G.W.; Angrist, J.D. Identification and Estimation of Local Average Treatment Effects. Econometrica 1994, 62, 467–475, doi:10.2307/2951620. [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office, G. of N. National Population and Housing Census 2021 Available online: https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/results/economic?province=5&district=52&municipality=9, (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Vu, H.T.; Tran, D.; Goto, D.; Kawata, K. Does Experience Sharing Affect Farmers’ pro-Environmental Behavior? A Randomized Controlled Trial in Vietnam. World Dev 2020, 136, doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105062. [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E.; Glennerster, R.; Kremer, M. Using Randomization in Development Economics Research: A Toolkit *; 2006;

- Mullally, C.; Boucher, S.; Carter, M. Encouraging Development: Randomized Encouragement Designs in Agriculture. Am J Agric Econ 2013, 95, 1352–1358, doi:10.1093/ajae/aat041. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Imbens, G.W. Two-Stage Least Squares Estimation of Average Causal Effects in Models With Variable Treatment Intensity. J Am Stat Assoc 1995, 90, 431–442, doi:10.1080/01621459.1995.10476535. [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, M.; Cheng, J.; Small, D.S. Instrumental Variable Methods for Causal Inference. Stat Med 2014, 33, 2297–2340, doi:10.1002/sim.6128. [CrossRef]

- Bastardoz, N.; Matthews, M.J.; Sajons, G.B.; Ransom, T.; Kelemen, T.K.; Matthews, S.H. Instrumental Variables Estimation: Assumptions, Pitfalls, and Guidelines. Leadership Quarterly 2023, 34, doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2022.101673. [CrossRef]

- Aizer, A.; Doyle, J.J. Juvenile Incarceration, Human Capital, and Future Crime: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges. Quarterly Journal of Economics 2015, 130, 759–804, doi:10.1093/qje/qjv003. [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Krueger, A.B. Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2001, 15, 69–85, doi:DOI: 10.1257/jep.15.4.69. [CrossRef]

- Sajons, G.B. Estimating the Causal Effect of Measured Endogenous Variables: A Tutorial on Experimentally Randomized Instrumental Variables. Leadership Quarterly 2020, 31, doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101348. [CrossRef]

- Omotilewa, O.J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Ainembabazi, J.H. Subsidies for Agricultural Technology Adoption: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment with Improved Grain Storage Bags in Uganda. Am J Agric Econ 2019, 101, 753–772, doi:10.1093/ajae/aay108. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Full Sample | Control | Encouragement-100 Group | Encouragement-50 Group | |||||||||||

| (n = 692) | (n = 347) | (100% subsidy offer) | (50% subsidy offer) | ||||||||||||

| (n = 149) | (n = 196) | ||||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| Panel A. Demographics | |||||||||||||||

| Age | 47.65 | 13.92 | 47.35 | 13.86 | 48.74 | 13.96 | 47.37 | 14.05 | |||||||

| Education (Year) | 6.08 | 3.71 | 6.16 | 3.57 | 6.09 | 3.94 | 5.93 | 3.78 | |||||||

| Gender | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.49 | |||||||

| Family size | 5.85 | 2.48 | 5.88 | 2.43 | 6.04 | 2.72 | 5.66 | 2.39 | |||||||

| Panel B. Economical (Income in thousands of Nepalese rupees -NPR) | |||||||||||||||

| Family income | 279.66 | 231.21 | 270.68 | 220.78 | 293.54 | 276.40 | 293.54 | 276.40 | |||||||

| Cereals income | 18.42 | 25.22 | 19.12 | 27.51 | 16.24 | 22.22 | 16.24 | 22.22 | |||||||

| Cash crop income | 8.85 | 28.60 | 10.86 | 37.57 | 6.82 | 14.54 | 6.82 | 14.54 | |||||||

| Forest income | 0.77 | 4.42 | 0.92 | 5.75 | 0.52 | 1.92 | 0.52 | 1.92 | |||||||

| Off-farm income | 217.69 | 225.68 | 205.08 | 214.82 | 234.65 | 264.38 | 234.65 | 264.38 | |||||||

| Livestock income | 26.77 | 32.01 | 27.66 | 37.13 | 27.73 | 32.19 | 27.73 | 32.19 | |||||||

| Panel C. Agricultural | |||||||||||||||

| Agri-experience (year) | 17.23 | 10.78 | 17.32 | 11.24 | 17.35 | 9.74 | 16.98 | 10.74 | |||||||

| Agri-land size (Ropani) | 9.14 | 6.15 | 9.01 | 6.06 | 9.43 | 6.57 | 9.14 | 6 | |||||||

| Maize Production Quantity (Kg) | 520 | 364 | 518 | 359.69 | 538.2 | 372.6 | 509.6 | 366.2 | |||||||

| Maize Plant Area (Ropani) | 5.63 | 3.86 | 5.59 | 3.84 | 5.81 | 3.91 | 5.57 | 3.89 | |||||||

| Panel D. Post-harvest management | |||||||||||||||

| Storage Period (month) | 8.67 | 2.92 | 8.63 | 2.91 | 8.77 | 2.8 | 8.64 | 3.05 | |||||||

| Insects (Dummy) | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 0.32 | |||||||

| Moths (Dummy) | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.46 | |||||||

| Storage Loss | 44.32 | 52.7 | 46.06 | 57.07 | 44.83 | 48.81 | 40.84 | 47.33 | |||||||

| New technology (Dummy) | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Variables | Encouragement-100 Vs. Control | Encouragement-50 Vs. Control | Encouragement-50 Vs. Encouragement-100 | ||||||

| Diff | S. E. | t-value | Diff | S. E. | t-value | Diff | S. E. | t-value | |

| Panel A. Demographics | |||||||||

| Age | -1.39 | 1.36 | -1.02 | -0.02 | 1.24 | -0.01 | -1.37 | 1.52 | -0.90 |

| Education (Year) | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.71 | -0.16 | 0.42 | -0.38 |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.29 | -0.04 | 0.05 | -0.83 |

| Family size | -0.16 | 0.25 | -0.65 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 1 | -0.38 | 0.28 | -1.37 |

| Panel B. Economical (Income in thousands of Nepali rupees (NPR) | |||||||||

| Family income | -22.87 | 23.39 | -0.98 | -14.32 | 19.43 | -0.73 | -8.54 | 26.25 | -0.33 |

| Cereals income | 2.88 | 2.55 | 1.13 | 0.28 | 2.32 | 0.12 | 2.61 | 2.47 | 1.06 |

| Cash crop income | 4.04 | 3.17 | 1.27 | 4.01 | 2.8 | 1.43 | 0.03 | 1.60 | 0.02 |

| Forest income | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.65 |

| Off-farm income | -29.57 | 22.60 | -1.31 | -22.03 | 19.10 | -1.15 | -7.54 | 25.65 | -0.29 |

| Livestock income | -0.07 | 3.50 | -0.02 | 3.17 | 2.86 | 1.11 | -3.24 | 2.81 | -1.15 |

| Panel C. Agricultural | |||||||||

| Agri-experience (year) | -0.03 | 1.06 | -0.03 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.34 | -0.37 | 1.12 | -0.33 |

| Agri-land size (Ropani) | -0.42 | 0.61 | -0.69 | -0.13 | 0.54 | -0.24 | -0.29 | 0.68 | -0.43 |

| Maize Production Quantity (Kg) | -20.18 | 35.61 | -0.57 | 8.38 | 32.35 | 0.26 | -28.56 | 40.11 | -0.71 |

| Maize Plant Area (Ropani) | -0.22 | 0.38 | -0.57 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.06 | -0.23 | 0.42 | -0.55 |

| Panel D. Post-harvest management | |||||||||

| Storage Period (month) | -0.14 | 0.28 | -0.49 | -0.004 | 0.26 | -0.02 | -0.13 | 0.32 | -0.42 |

| Insects (Dummy) | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.7 | -0.003 | 0.03 | -0.11 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.55 |

| Moths (Dummy) | -0.06 | 0.05 | -1.33 | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.54 | -0.04 | 0.05 | -0.76 |

| Storage Loss | 1.23 | 5.36 | 0.23 | 5.22 | 4.8 | 1.09 | -4.00 | 5.21 | -0.77 |

| New technology (earlier HST) (Dummy) | 0 | 0.02 | -0.25 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.57 | -0.02 | 0.01 | -1.68 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | Nos. of PICS bags | Nos. of PICS bags | Nos. of PICS bags | Nos. of PICS bags |

| 100% Subsidy offer | 0.76*** (0.08) |

0.76*** (0.08) |

||

| 50% Subsidy offer | 0.41*** (0.04) |

0.41*** (0.04) |

||

| Constant | 0.00***(0.00) | -0.21* (0.11) |

0.00 (0.00) |

-0.10* (0.06) |

| Observations | 496 | 496 | 543 | 543 |

| R-squared | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Covariates | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) |

| Nos. of PICS bags | 42.84*** (2.64) |

42.86*** (2.67) |

39.20*** (1.38) |

39.20*** (1.36) |

| Constant | -0.00*** (0.00) |

2.61 (5.41) |

0.00*** (0.00) |

0.97 (1.12) |

| Observations | 496 | 496 | 543 | 543 |

| R-squared | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Covariates | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | Post-harvest storage loss (Kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (Kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (Kg) | Post-harvest storage loss (Kg) |

| Nos. of PICS Hermetic bag | -10.05** (4.08) |

-10.02** (4.56) |

-11.93 (7.34) |

-9.37 (7.12) |

| Constant | 30.53*** (1.73) |

9.89 (7.50) |

30.67*** (1.75) |

5.61 (6.95) |

| Observations | 496 | 496 | 543 | 543 |

| R-squared | 0.02 | 0.05 | ||

| Covariates | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| First-stage | Second-stage | |||||

| Variables | No. of PICS bag | No. of PICS bag | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) | Storage quantity using PICS bag (kg) | Post-harvest storage losses (kg) | Post-harvest storage losses (kg) |

| 100% subsidy offer | 0.35*** (0.09) |

0.33*** (0.09) |

||||

| Nos. of PICS bag | 47.15*** (6.36) |

47.68*** (5.39) |

-8.24 (10.06) |

-10.94 (10.33) |

||

| Observations | 345 | 345 | 345 | 345 | 345 | 345 |

| R-squared | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||

| Covariates | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).