1. Introduction to CT Imaging in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Since the advent of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), imaging-based diagnosis of HCC has relied on three main modalities: CT, MRI, and conventional ultrasound. Based on the general principle that the liver is supplied by dual blood flow, with portal and arterial blood flows predominating in the liver parenchyma, whereas typical HCC derive their blood supply exclusively from the arteries, imaging techniques that visualize arterial and portal blood flow have been integral to HCC diagnosis since the early days of CT and MRI. Dynamic imaging studies, including the arterial and portal-dominant phases, have been performed using imaging over time after the injection of contrast media. The ultimate forms of CT arterial portography and CT hepatic arteriography have been developed, and several excellent studies have been conducted in Japan. These hemodynamic imaging techniques form the basis for HCC diagnosis.

Multi-detector row CT (MDCT) is currently in clinical use, dramatically reducing scanning time. Perfusion CT was once in the limelight as a diagnostic method for liver blood flow; however, it is not widely used for general examinations because of its complicated nature and the recent increase in X-ray exposure. With the exception of special imaging methods, such as perfusion CT, it is easy to separate the arterial and portal phases with MDCT with 64 or more rows, and post-contrast three-phase imaging is commonly used by adding an equilibrium phase to the arterial phase. In fact, because of the fast scan time, it is important to optimize the imaging timing after contrast injection and the injection method, such as the amount, concentration, and injection speed of the contrast agent, and implement an appropriate imaging protocol for the diagnosis of HCC. Recent technical topics in the CT diagnosis of HCC are discussed in other sections. This section highlights the fundamental principles and recent advancements in HCC differential diagnosis and the role of imaging in the pre- and post-treatment assessment of advanced HCC.

2. Diagnostic Efficacy of Dynamic CT in HCC

The diagnostic utility of dynamic CT/MRI for detecting HCC is well-established. The latest 2021 guidelines for HCC treatment [1] state that “Dynamic CT, dynamic MRI, or contrast-enhanced ultrasound is recommended for the diagnosis of typical HCC with EOB-MRI being recommended if either is feasible.” The statement “EOB-MRI is strongly recommended, grade A” leaves no doubt as to its usefulness, at least for the diagnosis of classic HCC. The guidelines recommend follow-up for high-risk patients, mainly for atypical tumors less than 1 cm in arterial phase that are not darkened by arterial phase and for other additional tests or biopsy if the tumor is 1.5 cm or larger but presents atypical imaging findings. These evidence-based guidelines make sense (Supplemental

Figure 1. A meta-analysis comparing the diagnostic performances of Gd-EOB-DTPA enhanced MRI (EOB-MRI), dynamic CT, and dynamic MRI revealed that the estimated sensitivities of EOB-MRI and CE-CT were 0.881 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.766, 0.944) and 0.713 (95% CI = 0.577, 0.577), respectively. .577, 0.819) and estimated specificity was 0.926 (95% CI = 0.829, 0.97) and 0.918 (95% CI = 0.829, 0.963), respectively. However, these differences were not statistically significant. However, when restricted to studies involving patients with small lesions, EOB-MRI was superior to CE-CT, with estimated sensitivities of 0.919 (95% CI = 0.834–0.962) and 0.637 (95% CI = 0.565–0.704) and an estimated specificity of 0.936 (95% CI = 0.882–0. 966) and 0.971 (95% CI = 0.937, 0.987), respectively [

2]. Another meta-analysis confirmed that EOB-MRI showed a significantly higher sensitivity than CT (0.85 vs. 0.68) and that the specificity did not differ between the two (0.94 vs. 0.93). (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve 0.79 vs. 0.46) [

3]. In our multicenter study of surgical cases, the sensitivity of EOB-MRI and dynamic MD-CT were 0.83 and 0.70, respectively, 0.58 and 0.28 for ≤1 cm, and 0.84 and 0.73 for 1–2 cm, all significantly superior to EOB-MRI, while for ≥2 cm, the sensitivity was 0.97 and 0.93 and 97 and 0.93, respectively, which were not statistically significant [

4] (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Although the detection sensitivity of CT for small HCC remains controversial, it has a high detection sensitivity for hypervascular classical hepatocellular carcinoma of 2 cm or larger, which is the main target of treatment, and almost 100% of HCC presenting typical findings with current dynamic CT or dynamic MRI can be diagnosed. This provides evidence that imaging of HCC with a focus on hemodynamics is extremely useful. MDCT is widely used in most facilities and has advantages over MRI, such as stable image quality and shorter examination time. Each scan was only a few seconds long and there was little deterioration in image quality, even in cases where respiratory arrest was not possible. Its diagnostic performance is comparable to that of MRI, except for small lesions. Dynamic computed tomography (CT) plays a significant role in diagnosing HCC.

3. Role of Dynamic CT/MRI in Differentiating Tumor Grades

Since the 1990s, studies have aimed at diagnosing early stage well-differentiated HCC, known as oligemic HCC. The evolution of contrast-enhanced MRI diagnoses has centered on the use of liver-specific MRI contrast agents such as Gd-EOB-DTPA6,7 and Gd-EOB-DTPA (oxide) [

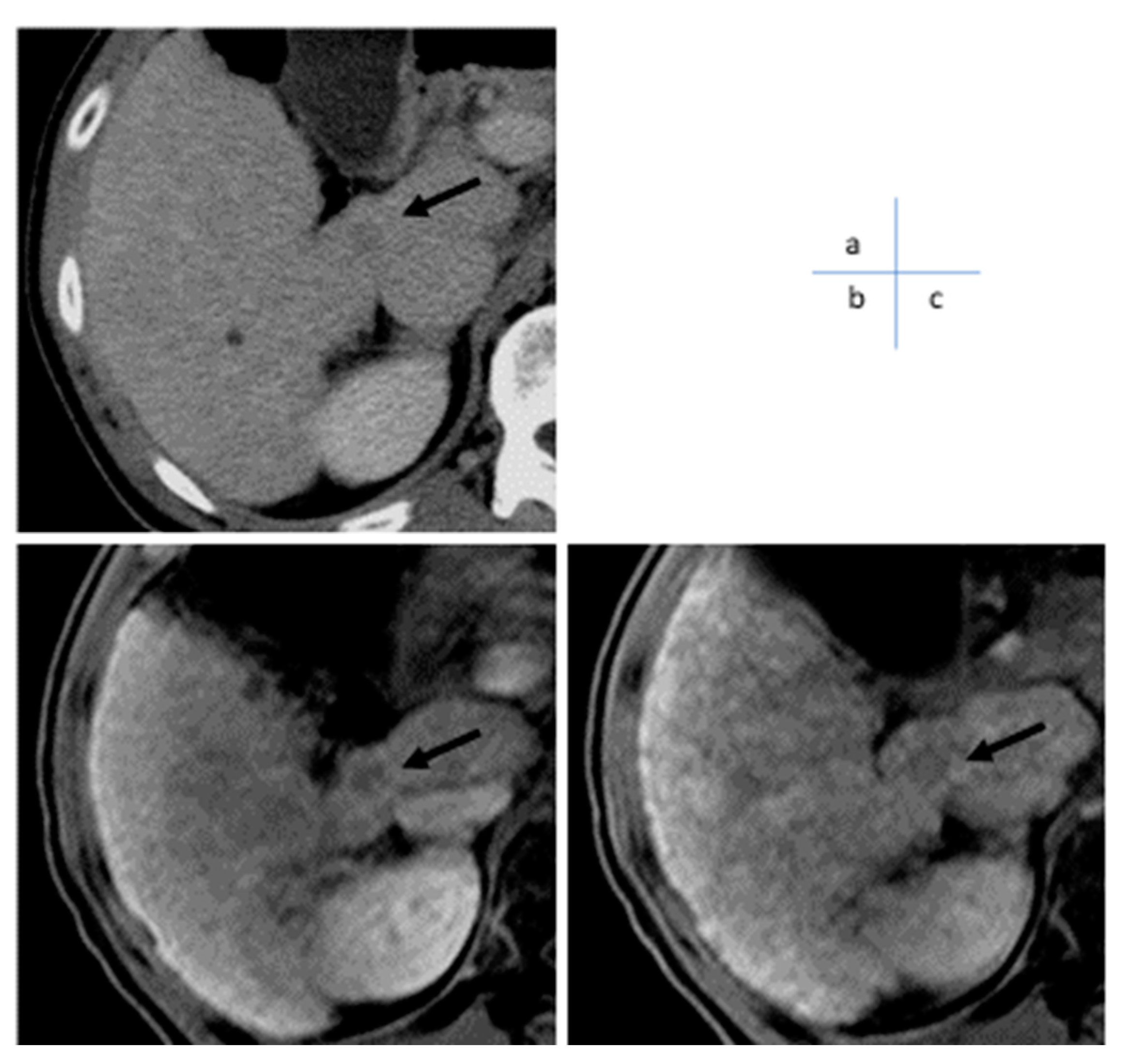

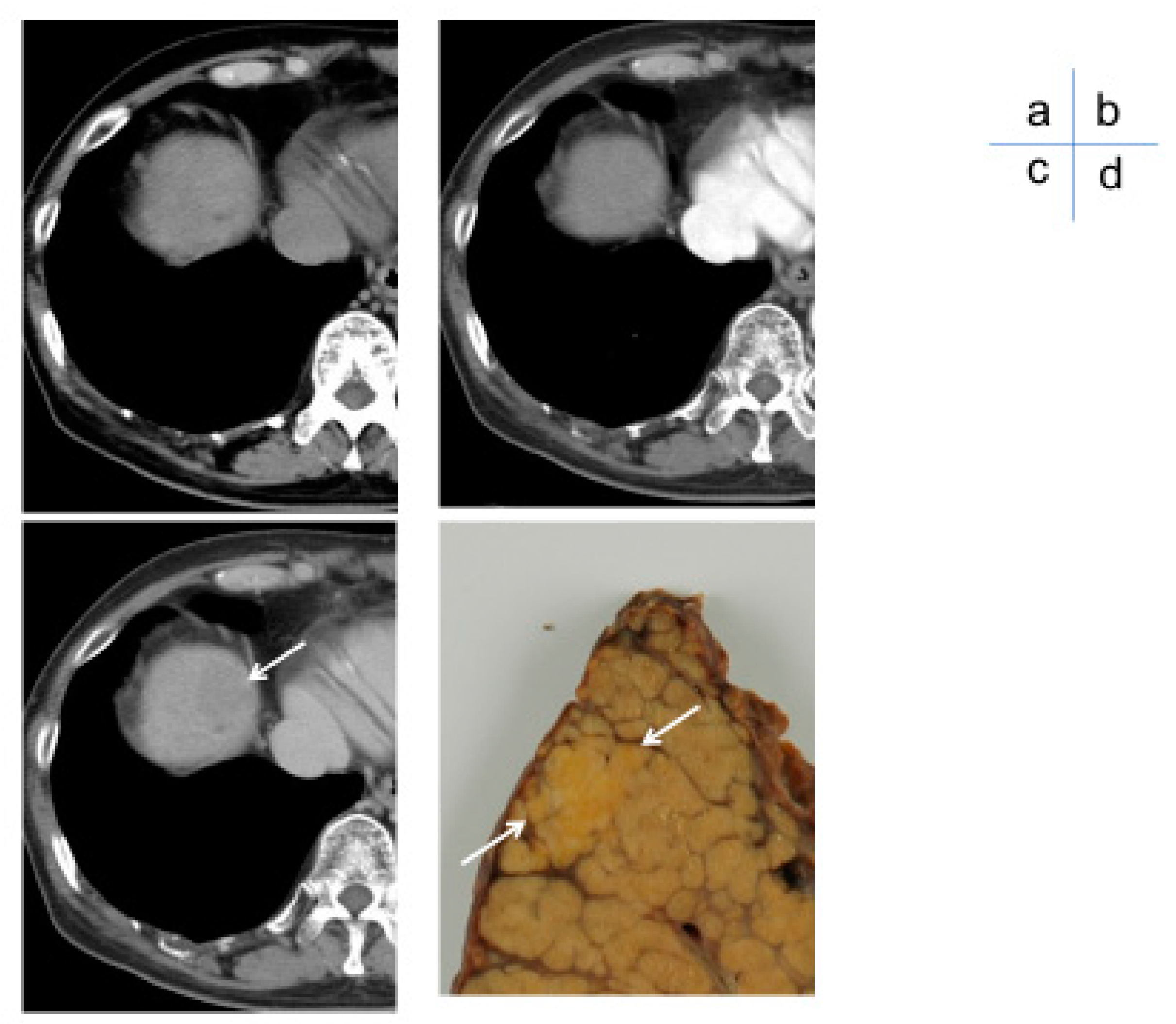

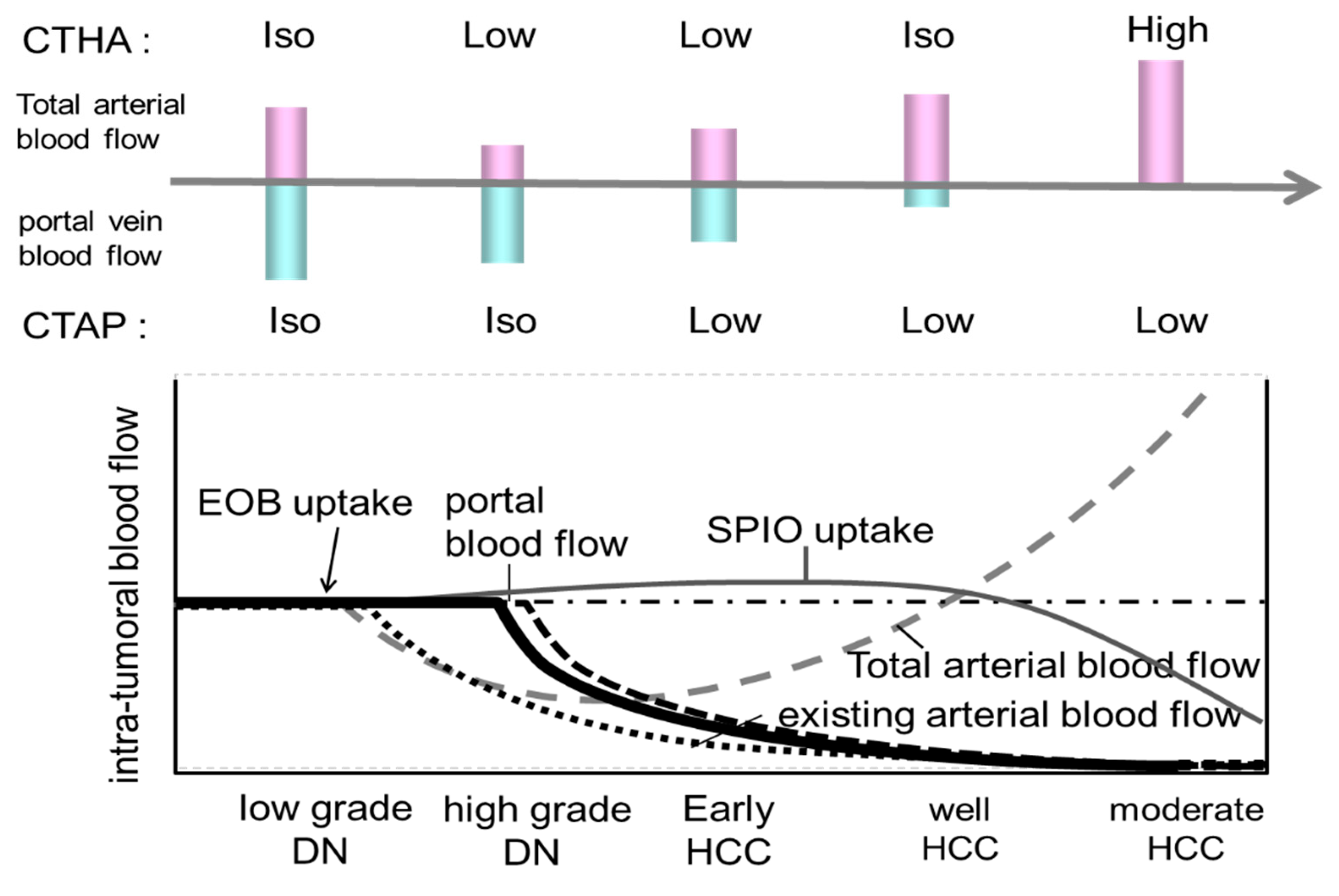

5]. When a small nodule is identified via ultrasound, intranodular blood flow is evaluated by dynamic CT/MRI, taking advantage of the difference in arterial and portal blood flow supply between the hepatic nodule and the surrounding liver parenchyma during the multistage development of HCC [

8] (

Figure 3). However, highly atypical nodules are those that partially show cell density more than twice that of the surrounding liver or have slight structural atypia. There is an overlap in the diagnosis of early-stage HCC and atypical nodules based on intra-nodular blood flow assessment, limiting differentiation by blood flow between the two. Therefore, at present, the diagnosis of borderline lesions and early HCC is limited to dynamic CT alone, as the diagnosis of oligo- (nonhemolytic) nodules in the hepatocellular phase of Gd-EOB-DTPA contrast-enhanced MRI best reflects differentiation [

6] (

Figure 4). Recently, however, it has been reported [

7] that among nonhypervascularized nodules showing low signal intensity in the hepatocellular phase, 44% are advanced HCC, 20% are early-stage HCC, 27.5% are highly differentiated nodules, and 8% are low-grade dysplastic and regenerative nodules; considerable overlap exists between these that should be noted. There is no clear evidence of the advantages and disadvantages of biopsy and treatment of non-hematopoietic lesions, including borderline lesions and early-stage HCC. According to recent expert opinions regarding the guidelines for the treatment of HCC [

1] and other carcinomas, biopsy at the initial presentation is undesirable in view of the balance between its invasiveness and the benefit obtained, and should be followed up with the addition of a second contrast scan or imaging studies.

A meta-analysis by Suh et al. found that in patients with chronic liver disease, the rate of polycythemia vera of non-polycythemia detected by EOB-MRI in the hepatocyte phase was 18% at 1 year, 25% at 2 years, and 30% at 3 years [

9]. Therefore, the cumulative hypervascularization rate of non-hypervascularized lesions is high and should not be neglected. Regular follow-up for hypervascularization, including dynamic CT/MRI, is important.

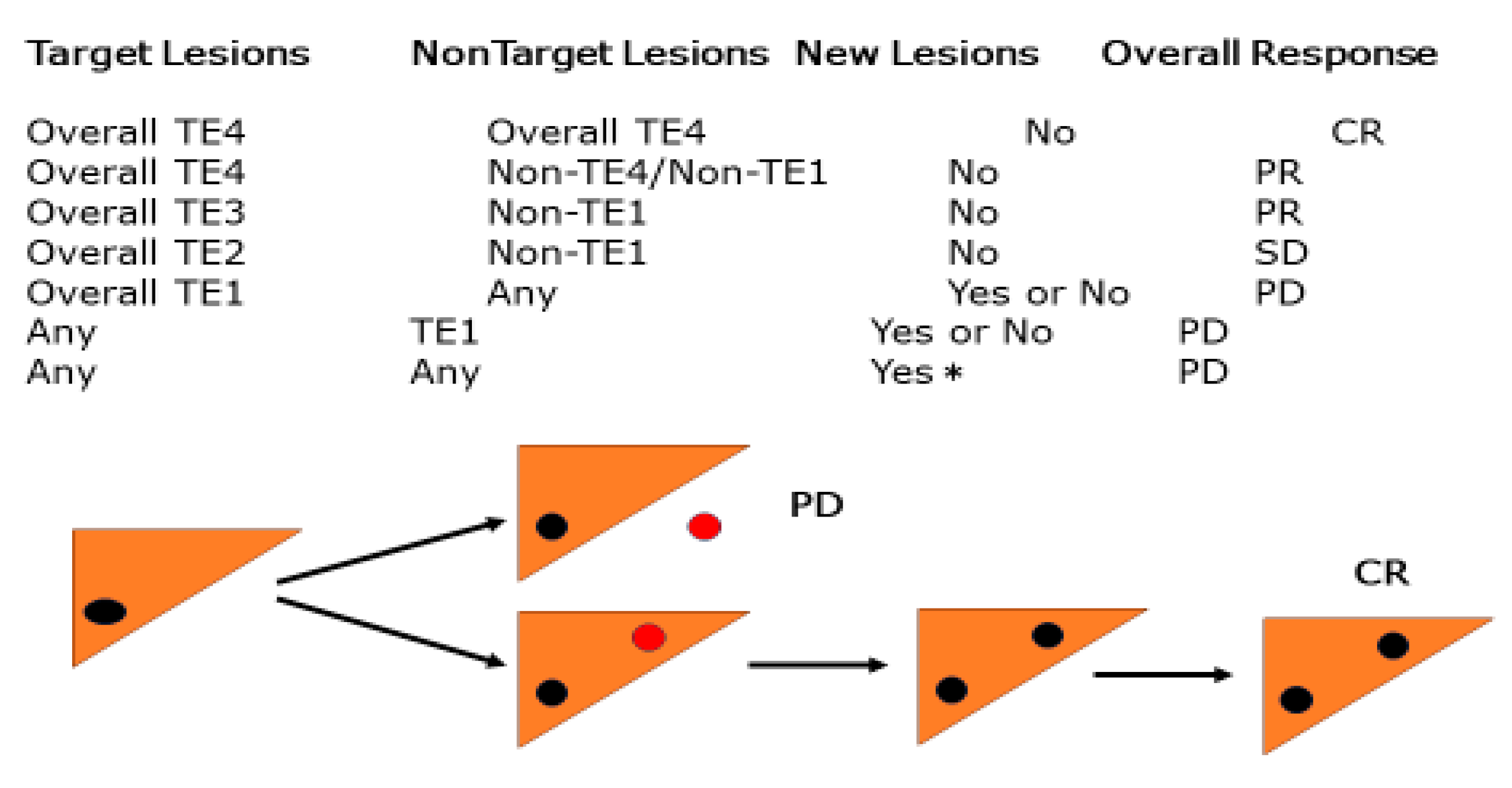

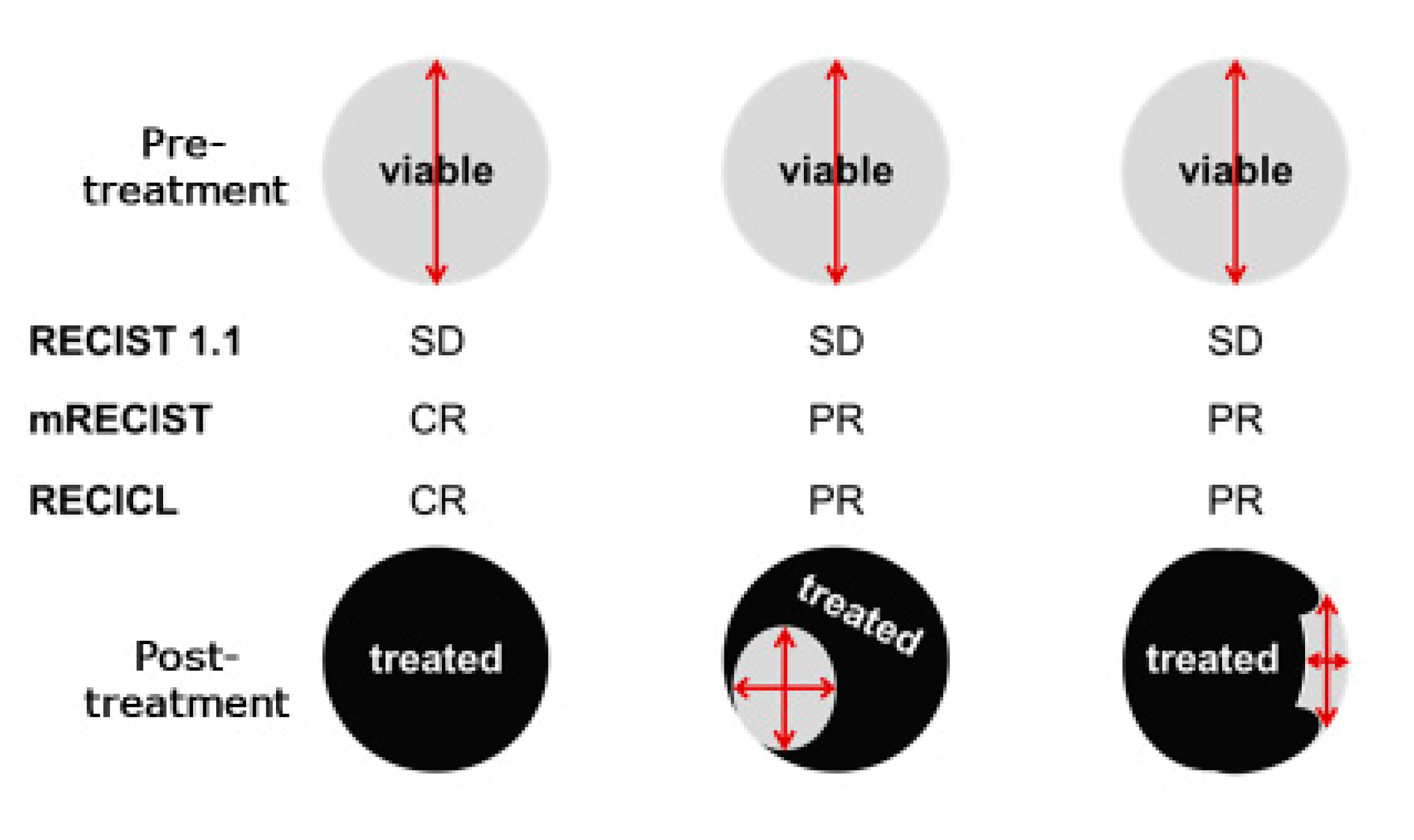

4. Treatment Response Assessment: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), Modified RECIST (mRECIST), and Liver Cancer Direct Effectiveness Criteria (RECICL) Criteria (Table 1)

In 2000, the RECIST guidelines were introduced as an alternative to the conventional WHO criteria for assessing treatment responses in solid tumors [

10]. RECIST primarily evaluates the treatment response by measuring changes in tumor length in one dimension. Owing to its simplicity and versatility, many clinical studies have used this criterion to evaluate outcomes, and it has now been further simplified and widely used in RECIST (version 1.1) [

11]. Although HCC and other types of liver cancer are carcinomas that can be treated with various local therapies to induce necrosis, RECIST does not consider such necrosis as “effective” but only tumor shrinkage as a measure of efficacy and is therefore considered inappropriate as a criterion for determining the efficacy of treatment for liver cancer. For example, studies have shown no correlation between tumor shrinkage (as measured by the WHO Health Organization criteria, RECIST) and pathological necrosis following transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) treatment; however, there is a discrepancy between the necrotic effect and effectiveness criteria for the local treatment characteristics of liver cancer, such as TACE. Furthermore, it is well known that classic HCC is stained in the arterial phase and has low absorption (washout) in the portal vein phase on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT. However, with the advent of molecular targeted therapeutic drugs that have recently been introduced, there have been cases in which tumor staining disappeared, while the tumor size did not change. In 2010, Lencioni et al. proposed the mRECIST, which evaluates the diameter of a darkened tumor area [

12]. The main idea was that in HCC, which is characterized by hypervascularity, the disappearance of tumor staining was considered the disappearance of a viable tumor. In the treatment of HCC, in which blood flow is important for evaluation, it seems appropriate to evaluate tumor staining, which has already been used as an efficacy criterion in many clinical trials and is increasingly used in daily practice.

Table 1.

Comparison of response evaluation criteria.

Table 1.

Comparison of response evaluation criteria.

| |

RECIST 1.1 |

mRECIST |

RECICL 2021 |

| target lesion |

target lesion

(five lesions, max two lesions per organ) |

target lesion

(10 lesions, maximum five lesions per organ) |

Maximum two lesions per organ

(but not more than three lesions in the liver)

Up to five lesions |

| Evaluation Method |

Unidirectional measurement

(Change in total longest diameter) |

Unidirectional measurement

(Change in total longest diameter. However, the indistinct area in contrast-enhanced CT is measured as necrosis.) |

Two-way measurement

(Change in the product of the longest diameter and the diameter perpendicular to it. Lipiodol deposition areas without stained areas or washout in CT are measured as necrosis.) |

| Comprehensive evaluation judgment method |

All targets before treatment.

The sum of the longest diameter of the lesion is

All targets after treatment

Sum and ratio of longest diameter of lesion

comparison |

All target diseases before treatment.

of the longest diameter of the non-necrotic part of the deformity.

sums for all post-treatment

Target lesion (non-necrotic area)

Sum of longest diameter vs. |

The sum of the products of the longest diameters of all target lesions and their orthogonal diameters before treatment is the baseline area sum. The sum of the products of the longest diameter and orthogonal diameters of necrotic/reduced lesions of all target lesions after treatment is the sum of area summation, and the difference from the baseline area summation is divided by the baseline area summation and expressed as “Overall TE” to contribute to the calculation of the overall evaluation judgment. |

| CR |

Disappearance of all target lesions

(Lymph nodes less than 10 mm in short diameter) |

Disappearance of all tumor staining |

100% necrosis effect or 100% shrinkage |

| PR |

Decreased by more than 30 |

Viable lesion diameter reduction of 30% or more |

Necrotic effect 50% to less than 100% or reduction of 50% to less than 100%. |

| SD |

PR, Effects other than PD |

PR, Effects other than PD |

PR, Effects other than PD |

| PD |

Increase of more than 20% or appearance of new lesions |

Increase in the sum of diameters of viable lesions by more than 20% or appearance of new lesions |

50% tumor growth (excluding necrotic areas due to treatment)

or appearance of new lesions |

Other criteria such as the RECICL of the Japanese Association for the Study of Liver Cancer and the Choi Criteria have been proposed to assess the therapeutic efficacy of imatinib for GIST [

13,

14,

15]. The basic concepts of RECICL, as described in a previous report [

16], are (1) concise and fully applicable in daily practice, (2) a criterion that can withstand international use, and (3) a criterion for determining therapeutic efficacy, mainly for local ablation therapy (ethanol injection therapy, microwave coagulation therapy, and radiofrequency ablation therapy) and transarterial catheterization. The effectiveness of tumor necrosis/reduction, as evaluated by mRECIST and RECICL, is based on local treatment, not systemic chemotherapy, and is routinely used in Japan. Therefore, it is important to evaluate tumor necrosis/shrinkage using such criteria, as has already been shown in many studies to correlate with prognosis, regardless of local or systemic chemotherapy [

17,

18,

19]. (

Figure 5).

In the evaluation of the overall response to locoregional therapy, the appearance of a new extrahepatic lesion was assessed as PD, whereas the appearance of only a new intrahepatic lesion was not assessed as PD, and the assessment was made after the next session of treatment. The overall response to the appearance of a new intrahepatic lesion after locoregional therapy may be tentatively described as new CR/PR/SD + intrahepatic lesions.

TE4, 100% tumor necrotizing effect or 100% tumor regression rate; TE4a: Necrotic area larger than the original tumor size; TE4b: Necrotic area as large as the original tumor size; TE3 Tumor necrosis rate < 50% and <100% OR tumor regression rate >50% and <100%; TE2

Effects between TE3 or TE1TE1 ≥50% increase in tumor size (excluding the area of treatment-induced necrosis)

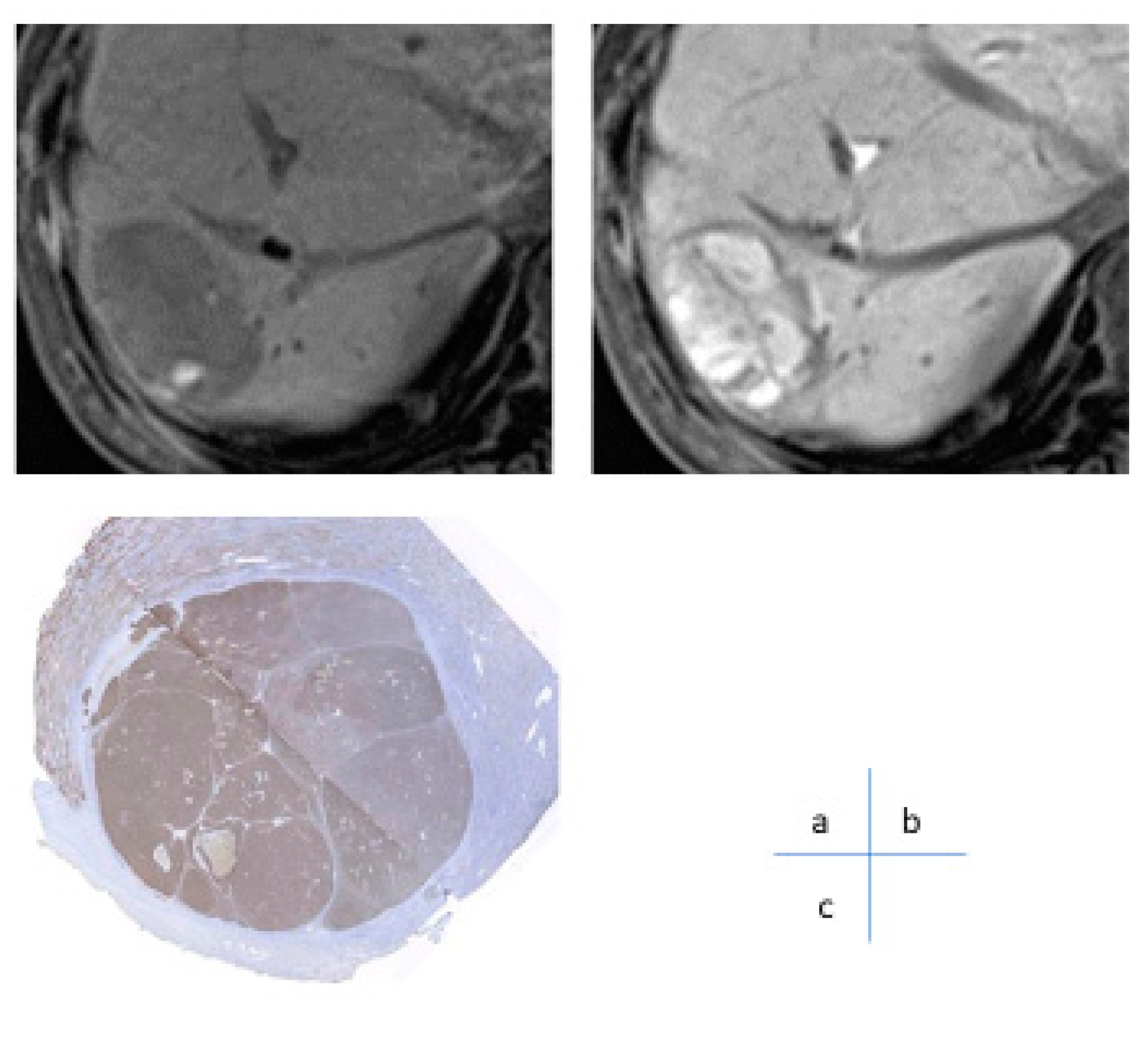

The RECICL criteria [

13] define “necrotic effect” as “an area of low staining seen after treatment on dynamic CT using the rapid intravenous infusion method” and “an area of low staining” means an area of low staining on dynamic CT using the rapid intravenous infusion method, both in the early and equilibrium phases, that is clearly lower than the surrounding liver parenchyma. In other words, the delta of low-density caused by rapid intravenous infusion was defined as the area where no increase in CT values was observed before and after contrast. Thus, dynamic CT with rapid intravenous infusion is the optimal imaging method for determining treatment efficacy. The first half of the dynamic phase (arterial-to-intermediate phase) of Gd-EOB-DTPA contrast-enhanced MRI is considered a secondary method. For determining treatment response in systemic chemotherapy with molecular-targeted drugs and recent immunotherapy, the latest guidelines for liver cancer treatment [

1] recommend the use of RECIST criteria or modified RECIST criteria for determining treatment response to drug therapy (strong recommendation, strength of evidence A). However, these guidelines do not mention imaging modalities. Furthermore, the aforementioned guideline for the treatment of liver cancer states that “dynamic CT/MRI is recommended for determining the efficacy of local puncture therapy (strong recommendation, strength of evidence B)”, “dynamic CT or dynamic MRI is recommended for determining the efficacy of TACE (strong recommendation, strength of evidence C)”, “dynamic CT or dynamic MRI is recommended for determining the efficacy of TACE (Strong recommendation, strength of evidence A)”, and “Dynamic CT or dynamic MRI is recommended for determining the efficacy of TACE (strong recommendation, strength of evidence B).” These guidelines describe the imaging modalities used to determine the efficacy of local therapy (

Figure 6).

The CT/MRI Treatment Response LI RADS

® in the American College of Radiology’s LI-RADS v2018 (The Liver Imaging Reporting And Data System) [

20] recommends radiofrequency ablation, ethanol injection, cryotherapy, and microwave ablation. The RADS is used to make treatment decisions for local therapies such as radiofrequency ablation, ethanol injection, cryotherapy, microwave ablation, conventional TACE, DEB-TACE, transarterial radioembolization (TARE; not approved in Japan), external-beam radiation therapy, and extracellular fluid contrast media (extracellular fluid) in high-risk patients, including patients with HCC scheduled for liver transplantation. Both pre- and post-extracellular contrast-enhanced CT and MRI or pre- and post-hepatobiliary excretory MRI are recommended for local therapies such as TARE and external radiation therapy in high-risk patients, including liver transplantation candidates.

Unlike RECIST, which is concerned only with changes in tumor size, treatment response criteria reflecting necrosis, such as mRECIST and RECICL, have begun to be widely used for HCC.

Blood flow imaging centered on dynamic CT has become indispensable not only for the qualitative diagnosis of tumors but also for determining treatment efficacy. In the future, it will be necessary to accumulate cases with issues in the evaluation of mRECIST and RECICL, and to discuss better criteria for determining efficacy, considering factors such as changes in tumor shape (internal necrosis), differences in efficacy between tumors, and the implications of dark staining. In addition, recently introduced immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma, which has recently been introduced, causes unique changes in tumor size and blood flow after treatment, and may require different efficacy criteria than conventional local therapy or molecular-targeted drugs. Therefore, it is necessary to establish different criteria for determining the efficacy of ICI therapy compared with conventional local therapies and molecular-targeted drugs.

6. Dynamic CT/MRI Imaging for Predicting Response to Systemic Chemotherapy in HCC

Sorafenib, a molecular targeted agent (MTA), was introduced as a first-line treatment for unresectable HCC in Japan in 2009. Despite numerous developments between 2009 and 2016, no new drugs have been approved.

Clinical trials fail at every turn. However, four drugs (regorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab) have been successfully tested in clinical trials since 2017: lenvatinib was approved in 2018 as a first-line treatment to replace sorafenib, followed by second-line treatment after sorafenib failure in June 2017; regorafenib and ramucirumab in June 2019; and cabozantinib in November 2020. These drugs prolong survival by maintaining stable disease or better; however, In September 2020, following the results of the IMbrave150 trial, atezolizumab, an anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, and in September 2020, the combination of atezolizumab, an PD-L1 antibody, and bevacizumab, a VEGF inhibitor, were approved [

21] and will become the first-line treatment for unresectable HCC by 2022.

Currently, there is no established biomarker for predicting the response to systemic chemotherapy in MTA exists because MTA has many targets beyond VEGF. Although perfusion MR/CT has been reported to be useful for predicting early response to treatment [

22,

23], it is not a common method for determining treatment response, and its clinical utility and impact have not been high.

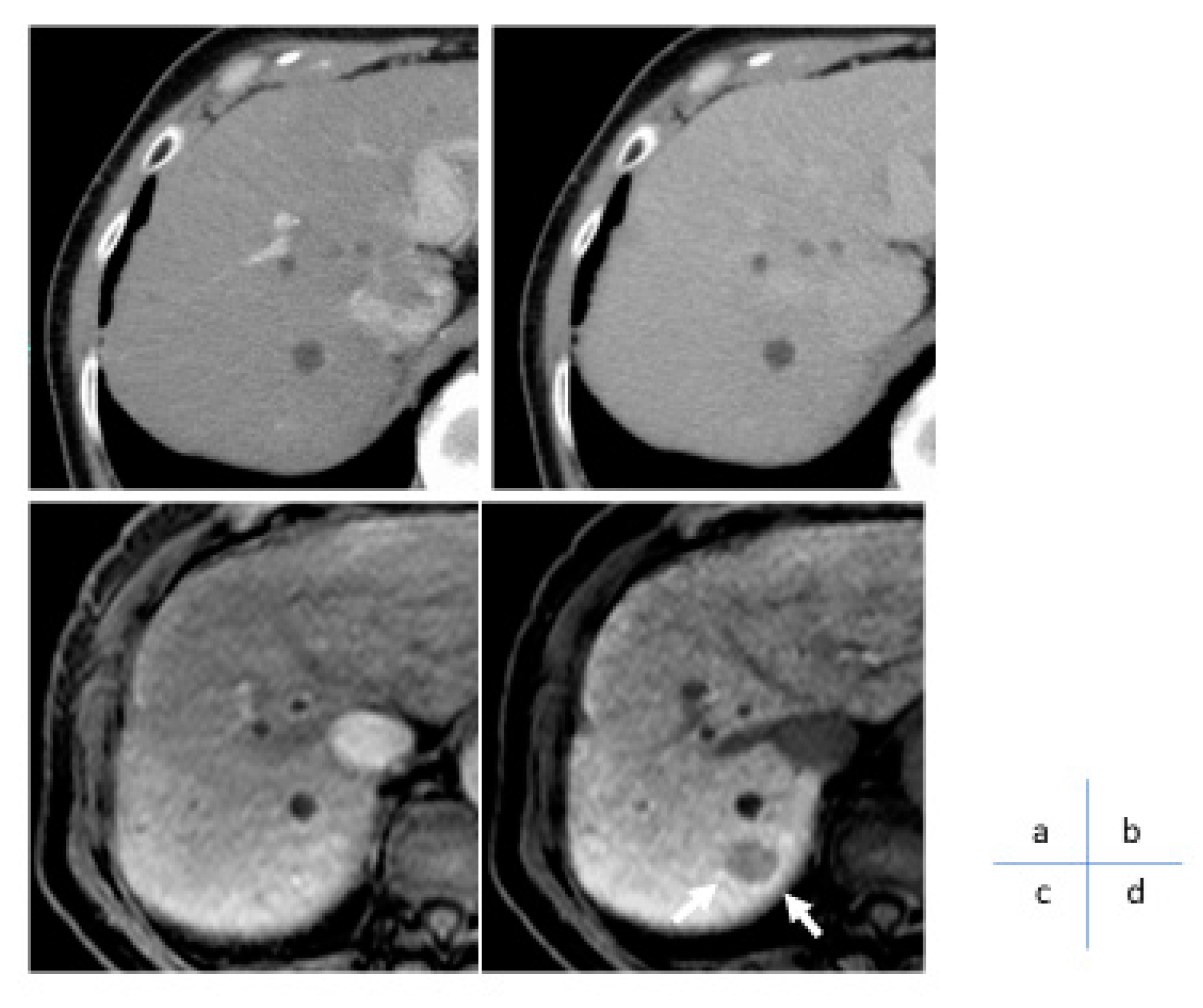

Gd-EOB-DTPA is a hepatocyte-specific contrast agent that is selectively taken up by hepatocytes via organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3), a plasma membrane transporter. Catenin gene mutations and OATP1B3 have shown a strong correlation, and it has been reported that Wnt/β-catenin activating mutations can be detected with a sensitivity of 78.9% and specificity of 81.7% using the EOB-MRI hepatocyte phase [

24]. Subsequent studies indicated that coactivation of Wnt/β-catenin mutations and their target gene, HNF4α, promotes the expression of OATP1B3 at the plasma membrane and depicts it as an iso to high signal nodule on EOB-MRI hepatocyte phase [

25]. Among HCC with Wnt/β-catenin activating mutations, nodules with HNF4α expression can be recognized by EOB-MRI hepatocellular phase, and EOB-MRI can discriminate HNF4α-positive hepatocellular carcinomas with good prognosis with little vascular invasion or distant metastasis (

Figure 7).

Furthermore, studies have indicated that HCCs with activated Wnt/β-catenin transmission pathways are resistant to first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapies. Our research group was the first to non-invasively identify HCC with Wnt/β-catenin activating mutations by EOB-MRI to predict therapeutic resistance to single ICI drugs [

26]. Specifically, nodules showing high signal intensity in the hepatocellular phase of EOB-MRI (nodules with Wnt/β-catenin gene mutations) had a lower response rate to ICI monotherapy and significantly higher tumor growth and recurrence rates.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1a. Algorithm for surveillance and diagnosis (Algorithm 1); Figure S1b. Surveillance and diagnostic algorithm (Algorithm 2).

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; contributed editing the tables and manuscript, K.S., T.M.; supervision, N.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hasegawa, K.; Takemura, N.; Yamashita, T.; Watadani, T.; Kaibori, M.; Kubo, S.; Shimada, M.; Nagano, H.; Hatano, E.; Aikata, H.; et al. Committee for Revision of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Tokyo, Japan. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma 2021 version (5th JSH-HCC guidelines). Hepatol Res; Vol. 53; The Japan Society of Hepatology, 2023; pp. 383–390. (Epub 2023 Mar 10). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, J.K.; Ma, N.; Vreugdenburg, T.D.; Cameron, A.L.; Maddern, G. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI for the characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017, 45, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Lei, L.; Yuan, G.; He, S. The diagnostic performance of gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and contrast-enhanced multi -detector computed tomography in detecting hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of eight prospective studies. Eur Radiol 2019, 29, 6519–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsurusaki, M.; Sofue, K.; Isoda, H.; Okada, M.; Kitajima, K.; Murakami, T. Comparison of gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and contrast-enhanced computed tomography with histopathological examinations for the identification of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter phase III study. J Gastroenterol 2016, 51, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Murakami, T.; Yoshida, S.; Nishikawa, M.; Ohsawa, M.; Tokunaga, K.; Murata, M.; Shibata, K.; Zushi, S.; Kurokawa, M.; et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance images of hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with histological grading. Hepatology 2000, 32, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Motosugi, U.; Sou, H.; Muhi, A.M.; Matsuda, M.; Nakano, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Nakazawa, T.; Asakawa, M.; et al. Imaging study of early hepatocellular carcinoma: usefulness of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 2011, 261, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, I.; Kim, S.Y.; Kang, T.W.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, B.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, J.I.; Lee, C.H.; Park, H.S.; Lee, K.; et al. Radiologic- pathologic correlation of hepatobiliary phase hypointense nodules without arterial phase hyperenhancement at gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI: a multicenter study. Radiology 2020, 296, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, O.; Kobayashi, S.; Sanada, J.; Kouda, W.; Ryu, Y.; Kozaka, K.; Kitao, A.; Nakamura, K.; Gabata, T. Hepatocelluar nodules in liver cirrhosis: hemodynamic evaluation (angiography-assisted CT) with special reference to multi-step hepatocarcinogenesis. Abdom Imaging 2011, 36, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.H.; Kim, K.W.; Pyo, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, S.H. Hypervascular transformation of hypovascular hypointense nodules in the hepatobiliary phase of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 209, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therasse, P.; Arbuck, S.G.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; Wanders, J.; Kaplan, R.S.; Rubinstein, L.; Verweij, J.; Van Glabbeke, M.; van Oosterom, A.T.; Christian, M.C.; et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000, 92, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer version 1.1 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R.; Josep, M.; Llovet, J.M. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Ikeda, M.; Ueshima, K.; Sakamoto, M.; Shiina, S.; Tateishi, R.; Nouso, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Furuse, J.; Miyayama, S.; et al. Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the liver version 6 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the Liver 2021 revised version). Hepatol Res 2022, 52, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H. Response evaluation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncologist 2008, 13, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacchiotti, S.; Collini, P.; Messina, A.; Morosi, C.; Barisella, M.; Bertulli, R.; Piovesan, C.; Dileo, P.; Torri, V.; Gronchi, A.; et al. High-grade soft-tissue sarcomas: tumor response assessment pilot study to assess the correlation between radiology. Radiology 2009, 251, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Kubo, S.; Takayasu, K.; Sakamoto, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ikai, I.; Furuse, J.; Nakamura, K.; Makuuchi, M.; Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (Committee for Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the Liver, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan). Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the Liver (RECICL) proposed by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (2009 Revised Version). Hepatol Res 2010, 40, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizumi, T.; Ueshima, K.; Takeda, H.; Osaki, Y.; Takita, M.; Inoue, T.; Kitai, S.; Yada, N.; Hagiwara, S.; Minami, Y.; et al. Comparison of systems for assessment of post-therapeutic response to sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2014, 49, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, B.; Di Maio, M.; Silletta, M.; D’Onofrio, L.; Spoto, C.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Daniele, G.; Comito, F.; Maci, E.; Bronte, G.; et al. Prognostic relevance of objective response according to the EASL criteria and mRECIST criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with loco-regional therapies: a literature-based meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0133488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R.; Montal, R.; Torres, F.; Park, J.W.; Decaens, T.; Raoul, J.L.; Kudo, M.; Chang, C.; Ríos, J.; Boige, V.; et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J Hepatol 2017, 66, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/CT/MRI LI-RADS®; Vol. 2018.

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med, The New England journal of medicine 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Kambadakone, A.; Kulkarni, N.M.; Zhu, A.X.; Sahani, D.V. Monitoring response to antiangiogenic treatment and predicting outcomes in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using image biomarkers, CT perfusion, tumor density, and tumor size (RECIST). Invest Radiol 2012, 47, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, S.; Thaiss, W.M.; Schulze, M.; Bitzer, M.; Lauer, U.; Nikolaou, K.; Horger, M. Prognostic value of perfusion CT in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment with sorafenib: comparison with mRECIST in longitudinal follow-up. Acta Radiol 2018, 59, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, A.; Masugi, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Komuta, M.; Effendi, K.; Tanami, Y.; Tsujikawa, H.; Tanimoto, A.; Okuda, S.; Itano, O.; et al. OATP1B3 expression is strongly associated with Wnt/beta-catenin signalling and represents the transporter of gadoxetic acid in hepatocellular carcinoma J Hepatol 2014, 61, 1080–1087. 61. [CrossRef]

- Kitao, A.; Matsui, O.; Yoneda, N.; Kozaka, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Koda, W.; Minami, T.; Inoue, D.; Yoshida, K.; Yamashita, T.; et al. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging reflects co-activation of beta-catenin and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2018, 48, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Nishida, N.; Ueshima, K.; Morita, M.; Chishina, H.; Takita, M.; Hagiwara, S.; Ida, H.; Minami, Y.; Yamada, A.; et al. Higher enhancement intrahepatic nodules on the hepatobiliary phase of Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI as a poor responsive marker of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2021, 10, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |