Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Acquisition Protocol

2.4. Data Analysis

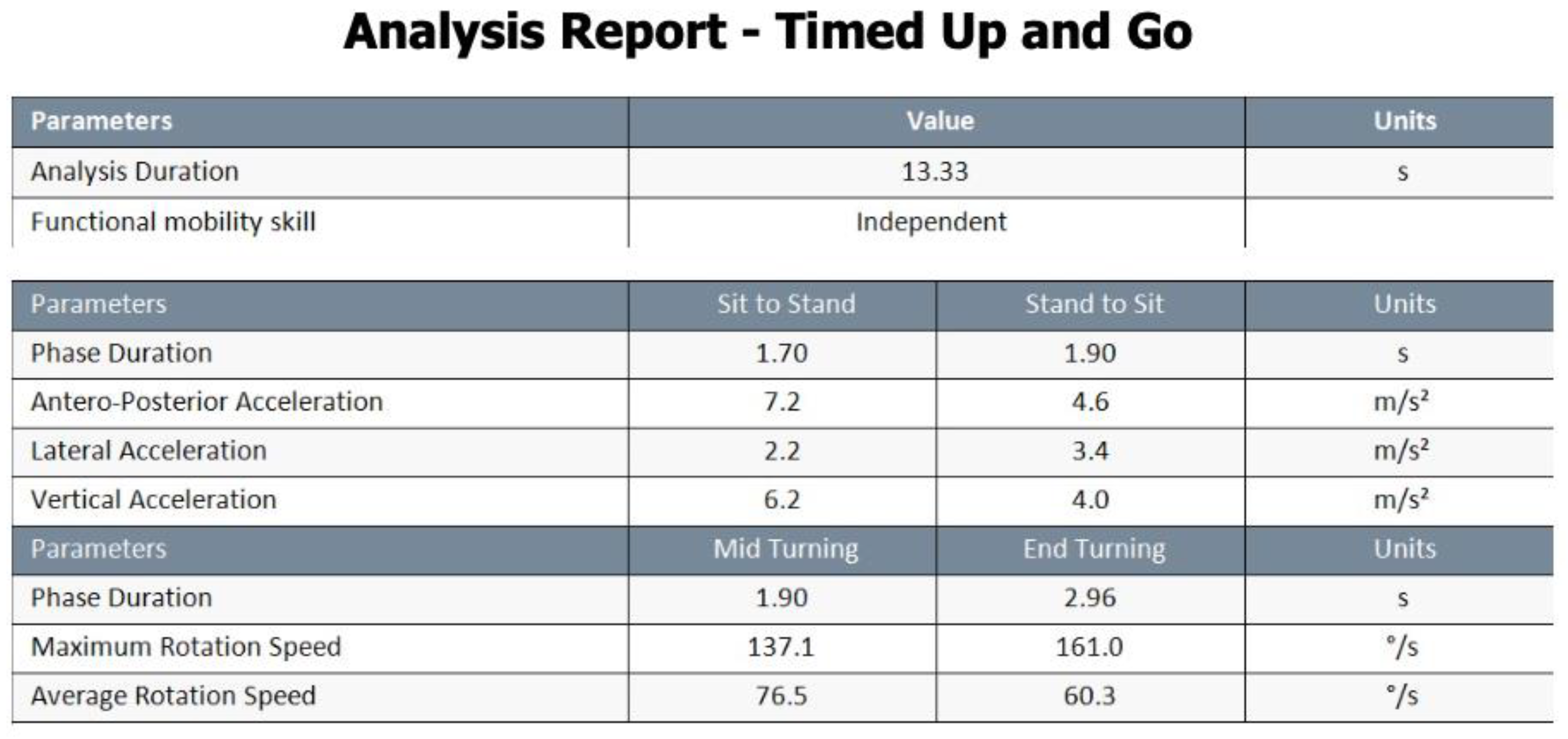

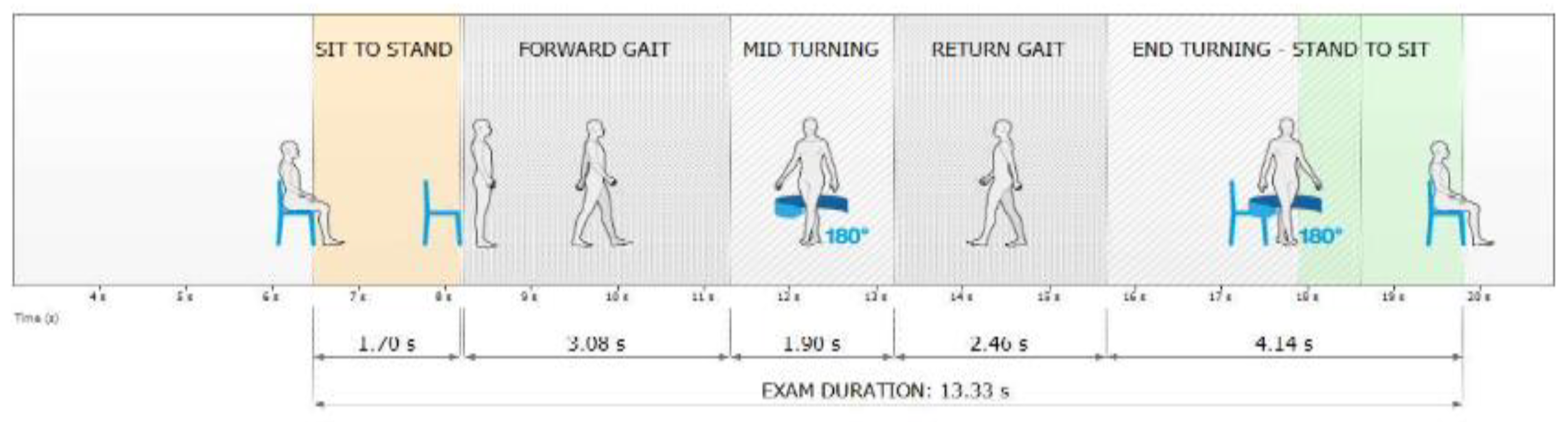

- Phase Duration, s: Indicated the average time interval for each movement in the respective phase.

- Antero-posterior Acceleration m/s²: Represented the average range of anteroposterior acceleration achieved during each assessed phase.

- Lateral Acceleration m/s²: Denoted the average range of medial-lateral acceleration observed during each assessed phase.

- Vertical Acceleration, m/s²: Captured the range of vertical acceleration experienced during each assessed phase.

- Phase Duration, sec: Represented the average temporal duration of each turn in the test.

- Maximum Rotation Speed, °/s: Indicated the maximum speed reached during each turn.

- Average Rotation Speed, °/s: Represented the average speed maintained throughout each turn.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Disclaimers and Acknowledgments

References

- Kowal, P. An Aging World: 2015. 2016. [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Lucchesi, L.R.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dingels, Z. V.; Fox, J.T.; Hamilton, E.B.; Henry, N.J.; Krohn, K.J.; Liu, Z.; et al. The Global Burden of Falls: Global, Regional and National Estimates of Morbidity and Mortality from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Injury Prevention 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Y.K.; Miller, G.F.; Kakara, R.; Florence, C.; Bergen, G.; Burns, E.R.; Atherly, A. Healthcare Spending for Non-Fatal Falls among Older Adults, USA. Inj Prev 2024, 30, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, J.L.; Truong, L.K.; Dhiman, K.; Beck, C. Osteoarthritis Year in Review 2020: Rehabilitation and Outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guccione, A.A.; Felson, D.T.; Anderson, J.J.; Anthony, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Kelly-Hayes, M.; Wolf, P.A.; Kreger, B.E.; Kannel, W.B. The Effects of Specific Medical Conditions on the Functional Limitations of Elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health 1994, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glyn-Jones, S.; Palmer, A.J.R.; Agricola, R.; Price, A.J.; Vincent, T.L.; Weinans, H.; Carr, A.J. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 2015, 386, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.X.; Fu, Z.Y.; Han, R.Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, P.; Hou, S.; Pan, H.F. Trends and Cross-Country Inequalities in the Global Burden of Osteoarthritis, 1990–2019: A Population-Based Study. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthritis Prevalence and Activity Limitations— United States, 1990. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1994, 272. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I.J.; Worthington, S.; Felson, D.T.; Jurmain, R.D.; Wren, K.T.; Maijanen, H.; Woods, R.J.; Lieberman, D.E. Knee Osteoarthritis Has Doubled in Prevalence since the Mid-20th Century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.T.; Tan, M.P. Osteoarthritis and Falls in the Older Person. Age Ageing 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Barker, A.; Soh, S.E. Falls Prevention and Osteoarthritis: Time for Awareness and Action. Disabil Rehabil 2023, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Scanaill, C.; Garattini, C.; Greene, B.R.; McGrath, M.J. Technology Innovation Enabling Falls Risk Assessment in a Community Setting. Ageing Int 2011, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisseret, F.; Catinus, L.; Grenard, R.; Jojczyk, L.; Fievez, D.; Barvaux, V.; Dierick, F. Timed up and Go and Six-Minute Walking Tests with Wearable Inertial Sensor: One Step Further for the Prediction of the Risk of Fall in Elderly Nursing Home People. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, T.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. Properties of the “Timed Up and Go” Test: More than Meets the Eye. Gerontology 2011, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drootin, M. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Herman, T.; Plotnik, M.; Brozgol, M.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. An Instrumented Timed up and Go: The Added Value of an Accelerometer for Identifying Fall Risk in Idiopathic Fallers. Physiol Meas 2011, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Mercant, A.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Clinical Frailty Syndrome Assessment Using Inertial Sensors Embedded in Smartphones. Physiol Meas 2015, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Mercant, A.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Differences in Trunk Accelerometry between Frail and Non-Frail Elderly Persons in Functional Tasks. BMC Res Notes 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Mirelman, A.; Giladi, N.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Hausdorff, J.M. Transition Between the Timed up and Go Turn to Sit Subtasks: Is Timing Everything? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.; Lou, N.; Liang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, G. A Novel Environment-Adaptive Timed up and Go Test System for Fall Risk Assessment with Wearable Inertial Sensors. IEEE Sens J 2021, 21, 18287–18297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Serpelloni, M.; Amici, C.; Gobbo, M.; Silvestro, C.; Buraschi, R.; Borboni, A.; Crovato, D.; Lopomo, N.F. Use of Wearable Inertial Sensor in the Assessment of Timed-Up-and-Go Test: Influence of Device Placement on Temporal Variable Estimation. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST; 2017; Volume 192. [Google Scholar]

- Wüest, S.; Massé, F.; Aminian, K.; Gonzenbach, R.; de Bruin, E.D. Reliability and Validity of the Inertial Sensor-Based Timed “Up and Go” Test in Individuals Affected by Stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev 2016, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, C.; Salarian, A.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; Horak, F.B. Assessing Mobility at Home in People with Early Parkinson’s Disease Using an Instrumented Timed Up and Go Test. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, G.R.A.; Valle, M.S.; Casabona, A.; Vagnini, A.; Cioni, M. Age-Related Changes in Mobility Evaluated by the Timed up and Go Test Instrumented through a Single Sensor. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasadzka, E.; Borowicz, A.M.; Roszak, M.; Pawlaczyk, M. Assessment of the Risk of Falling with the Use of Timed up and Go Test in the Elderly with Lower Extremity Osteoarthritis. Clin Interv Aging 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Beam, W.C. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport A 30-s Chair-Stand Test as a Measure of Lower Body Strength in Community-Residing Older Adults. shapeamerica.tandfonline.com 2013, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, N.; Osman, N.A.A.; Mokhtar, A.H.; Mehdikhani, M.; Abas, W.A.B.W. Balance and Risk of Fall in Individuals with Bilateral Mild and Moderate Knee Osteoarthritis. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli, R.E.; Beam, W.C. A 30-s Chair-Stand Test as a Measure of Lower Body Strength in Community-Residing Older Adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 1999, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc-Harkey, B.A.; Safran-Norton, C.E.; Mandl, L.A.; Katz, J.N.; Losina, E. Associations among Knee Muscle Strength, Structural Damage, and Pain and Mobility in Individuals with Osteoarthritis and Symptomatic Meniscal Tear. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batushansky, A.; Zhu, S.; Komaravolu, R.K.; South, S.; Mehta-D’souza, P.; Griffin, T.M. Fundamentals of OA. An Initiative of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. Obesity and Metabolic Factors in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A.; Stewart, C.; Postans, N.; Barlow, D.; Dodds, A.; Holt, C.; Whatling, G.; Roberts, A. Abnormal Loading of the Major Joints in Knee Osteoarthritis and the Response to Knee Replacement. Gait Posture 2013, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baets, L.; Matheve, T.; Timmermans, A. The Association between Fear of Movement, Pain Catastrophizing, Pain Anxiety, and Protective Motor Behavior in Persons with Peripheral Joint Conditions of a Musculoskeletal Origin: A Systematic Review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Brauer, S.; Woollacott, M. Predicting the Probability for Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using the Timed up and Go Test. Phys Ther 2000, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansai, J.H.; Farche, A.C.S.; Rossi, P.G.; De Andrade, L.P.; Nakagawa, T.H.; Takahashi, A.C.D.M. Performance of Different Timed Up and Go Subtasks in Frailty Syndrome. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 2019, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, E.; Hwang, H.; Woo, Y. Study of Acceleration of Center of Mass during Sit-to-Stand and Stand-to-Sit in Patients with Stroke. J Phys Ther Sci 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manckoundia, P.; Mourey, F.; Pfitzenmeyer, P.; Papaxanthis, C. Comparison of Motor Strategies in Sit-to-Stand and Back-to-Sit Motions between Healthy and Alzheimer’s Disease Elderly Subjects. Neuroscience 2006, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, S.D.M.; Radanovic, M.; Forlenza, O.V. Fear of Falling and Falls in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimers Disease. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Canning, C.G.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Falls in Parkinson’s Disease: A Complex and Evolving Picture. Movement Disorders 2017, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.D.; Khan, K.M.; McKay, H.A.; Petit, M.A.; Waterman, C.; Heinonen, A.; Janssen, P.A.; Donaldson, M.G.; Mallinson, A.; Riddell, L.; et al. Community-Based Exercise Program Reduces Risk Factors for Falls in 65- to 75-Year-Old Women with Osteoporosis: Randomized Controlled Trial. CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2002, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley, K.M.; Straus, S.E.; Inness, E.L.; Salbach, N.M.; Jaglal, S.B. Balance Assessment Practices and Use of Standardized Balance Measures among Ontario Physical Therapists. Phys Ther 2011, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.C.; Xiong, H.Y.; Zheng, J.J.; Wang, X.Q. Dance Movement Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverwood, V.; Blagojevic-Bucknall, M.; Jinks, C.; Jordan, J.L.; Protheroe, J.; Jordan, K.P. Current Evidence on Risk Factors for Knee Osteoarthritis in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteckova, S.; Horakova, H.; Polakova, K.; Krupicka, R.; Ruzicka, E.; Brozova, H. Agreement between the GAITRite R System and the Wearable Sensor BTS G-Walk R for Measurement of Gait Parameters in Healthy Adults and Parkinson’s Disease Patients. PeerJ 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkan-Yazici, M.; Çobanoğlu, G.; Yazici, G. Test-Retest Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change for Measures of Wearable Gait Analysis System (G-Walk) in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Turk J Med Sci 2022, 52, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All participants (n=39) | |||

|

Knee Osteoarthritis Patients (n=20) |

Healthy Controls (n=60) |

p-value | |

| Age (year) | 74.84 (6.694) | 72.25 (5.220) | 0.184 |

| Weight (kg) | 83.79 (16.788) | 78.60 (9.816) | 0.243 |

| Height (cm) | 165.74 (7.117) | 165.00 (8.784) | 0.776 |

| BMI | 30.46 (5.61) | 29.00 (3.83) | 0.335 |

| Shoe size (EU) | 39.68 (2.358) | 39.55 (2.502) | 0.864 |

| Gender, Male/Female, N(%) | 5(15.8) / 15(84.2) | 15(25.0)/45(75.0) | 0.695 |

| Knee Osteoarthritis Patients | Healthy Controls | p-value | |

| Analysis duration, s | 22.32±5.49 | 12.94±1.88 | <0.001 |

| Sit to Stand Phase Duration, s | 2.35±0.64 | 1.62±0.33 | <0.001 |

| Forward Gait Phase Duration, s | 5.65±2.45 | 2.96±0.83 | <0.001 |

| Return Gait Phase Duration, s | 5.58±2.46 | 3.03±0.72 | <0.001 |

| Stand to Sit Antero-Posterior Acceleration, m/s² | 3.07±1.64 | 4.06±1.53 | 0.060 |

| Sit to Stand Vertical Acceleration, m/s² | 2.83±1.01 | 4.02±1.07 | <0.001 |

| Stand to Sit Vertical Acceleration, m/s² | 4.95±2.70 | 6.17±2.57 | 0.156 |

| End Turning Phase Duration, sec | 3.35±0.92 | 1.84±0.56 | <0.001 |

| Mid Turning Maximum Rotation Speed, °/s | 116.70±33.78 | 149.60±27.83 | 0.002 |

| End Turning Maximum Rotation Speed, °/s | 106.14±29.27 | 168.02±35.48 | <0.001 |

| Mid Turning Average Rotation Speed, °/s | 56.94±20.12 | 88.29±20.48 | <0.001 |

| End Turning Average Rotation Speed, °/s | 50.59±14.95 | 91.29±22.76 | <0.001 |

| Median(IQR) | Median(IQR) | ||

| Stand to Sit Phase Duration, s | 2.30±0.90 | 1.90±0.75 | 0.017 |

| Sit to Stand Antero-Posterior Acceleration, m/s² | 2.00±1.20 | 3.10±0.92 | 0.002 |

| Sit to Stand Lateral Acceleration, m/s² | 1.40±0.60 | 1.70±0.38 | 0.002 |

| Stand to Sit Lateral Acceleration, m/s² | 3.10±1.50 | 3.65±0.92 | 0.086 |

| Mid Turning Phase Duration, s | 3.03±1.20 | 1.88±0.80 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).