Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

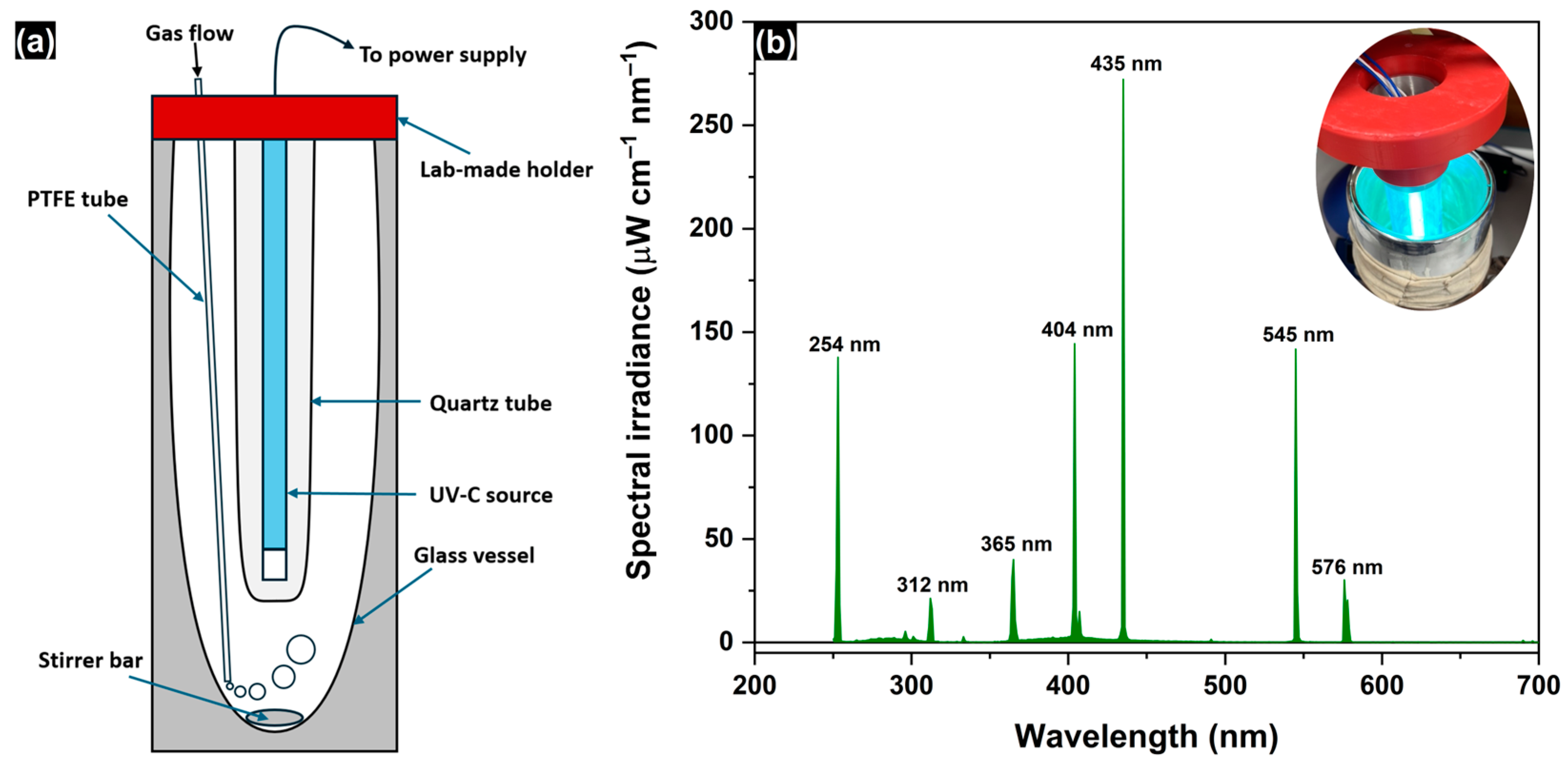

2. Results and Discussion

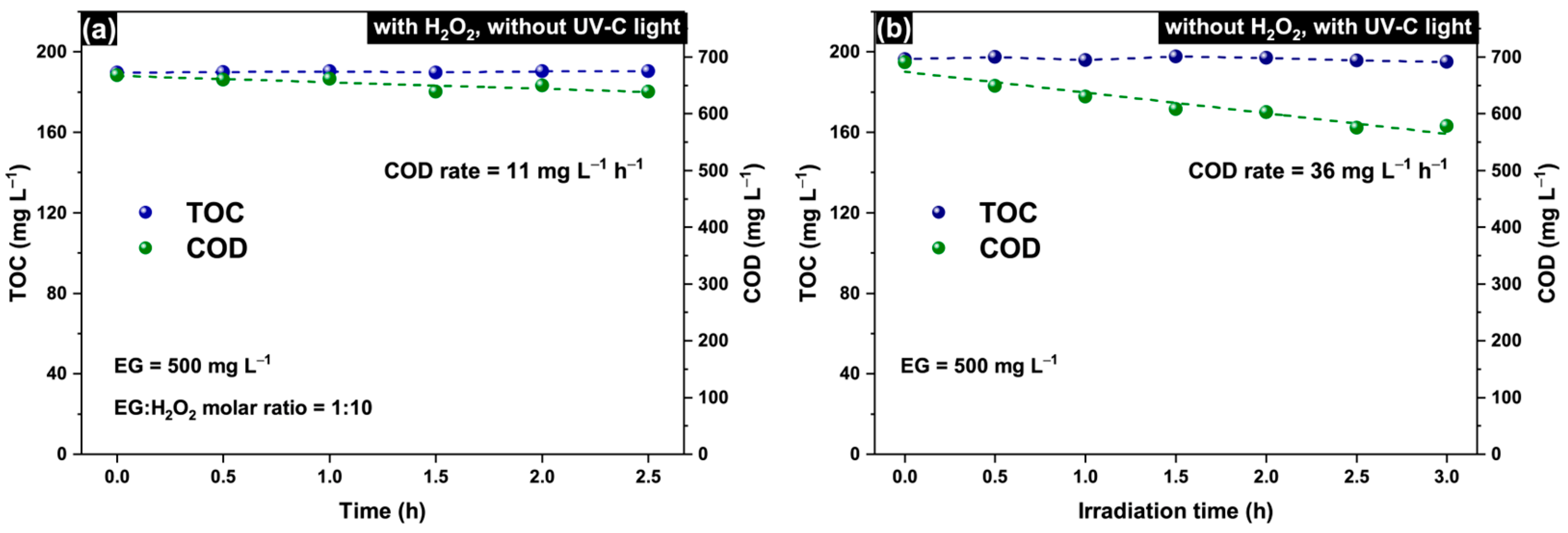

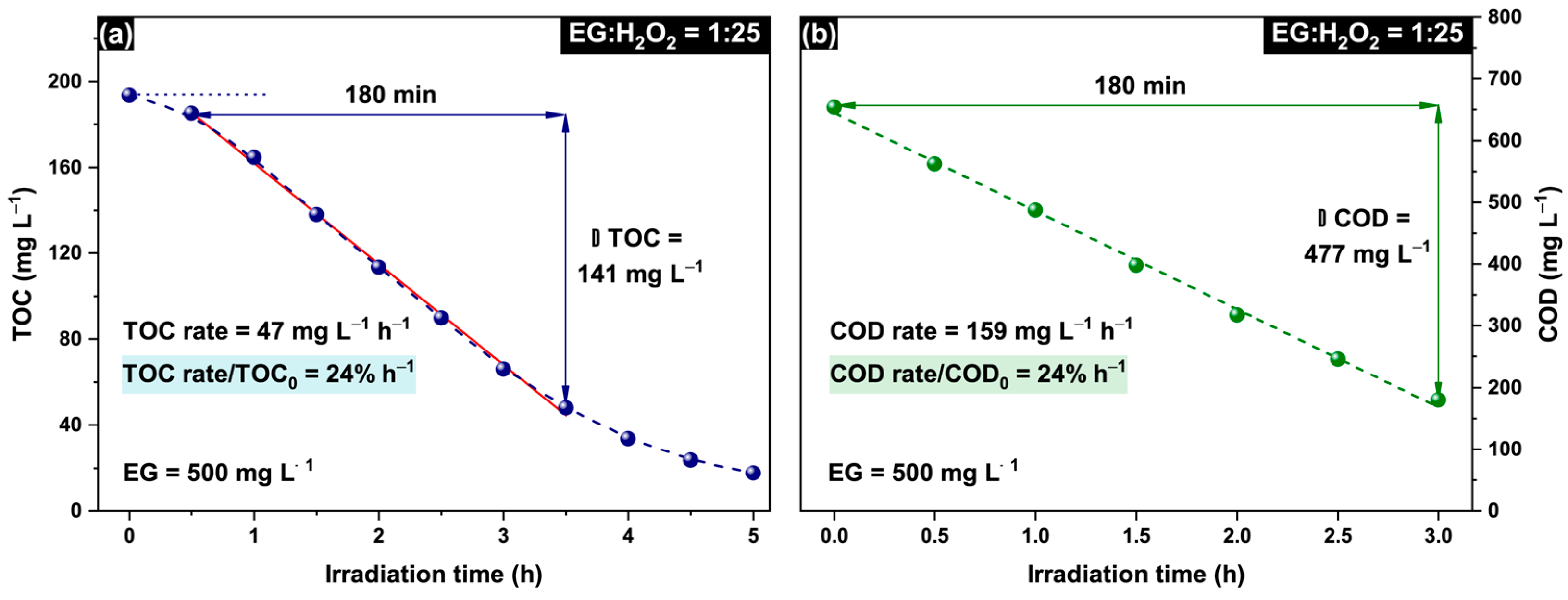

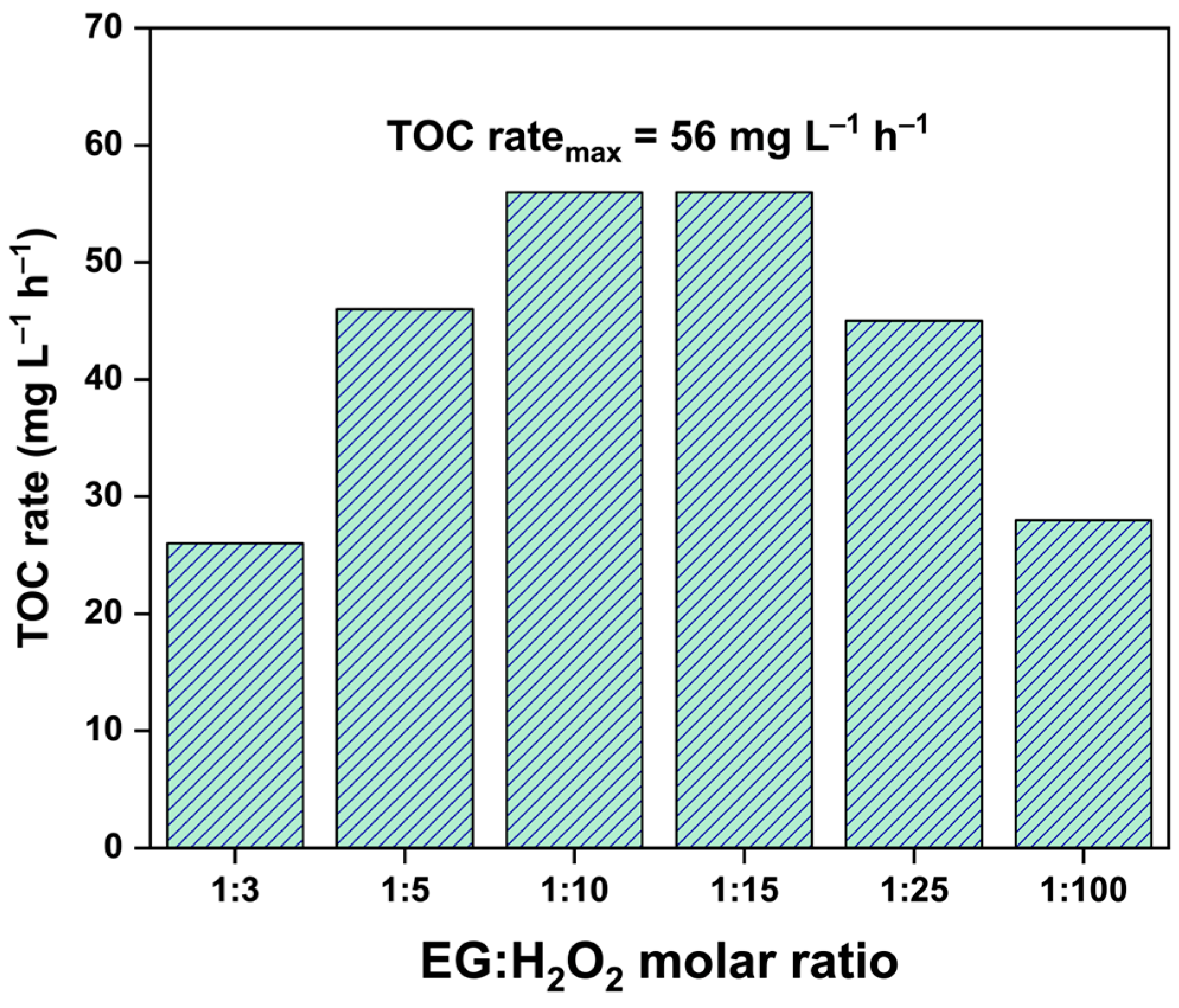

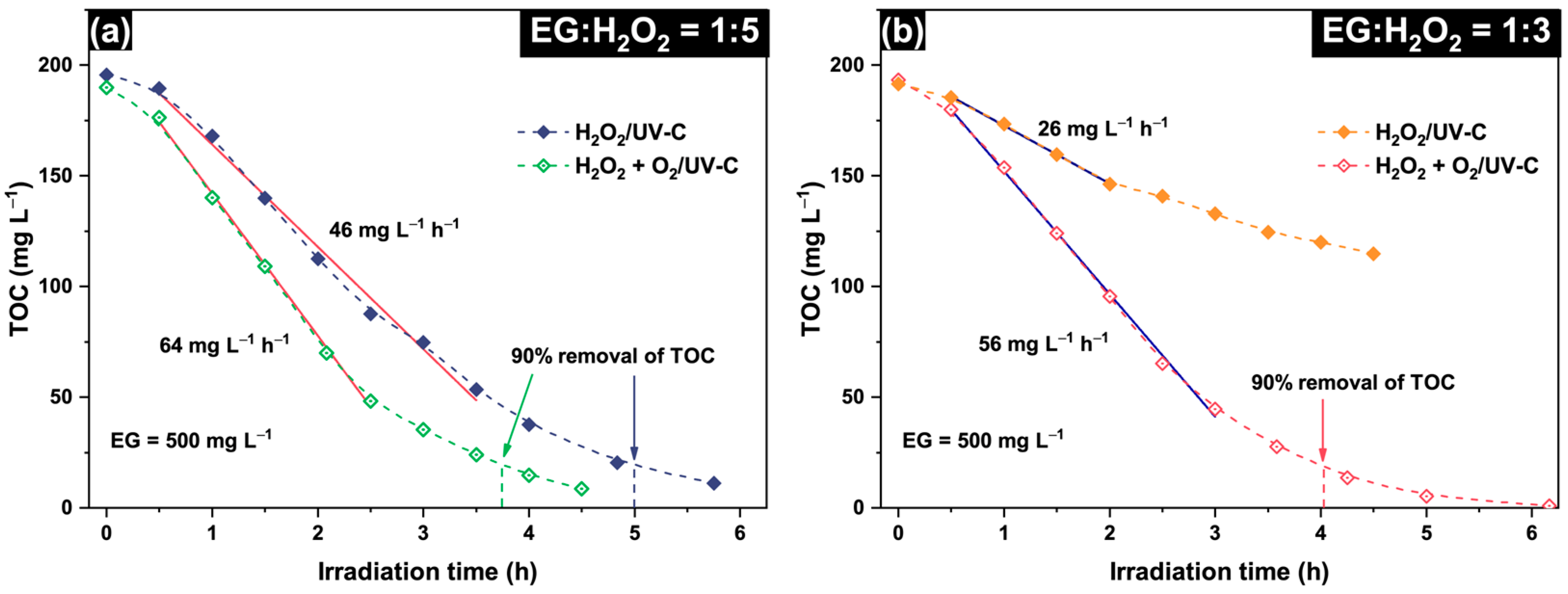

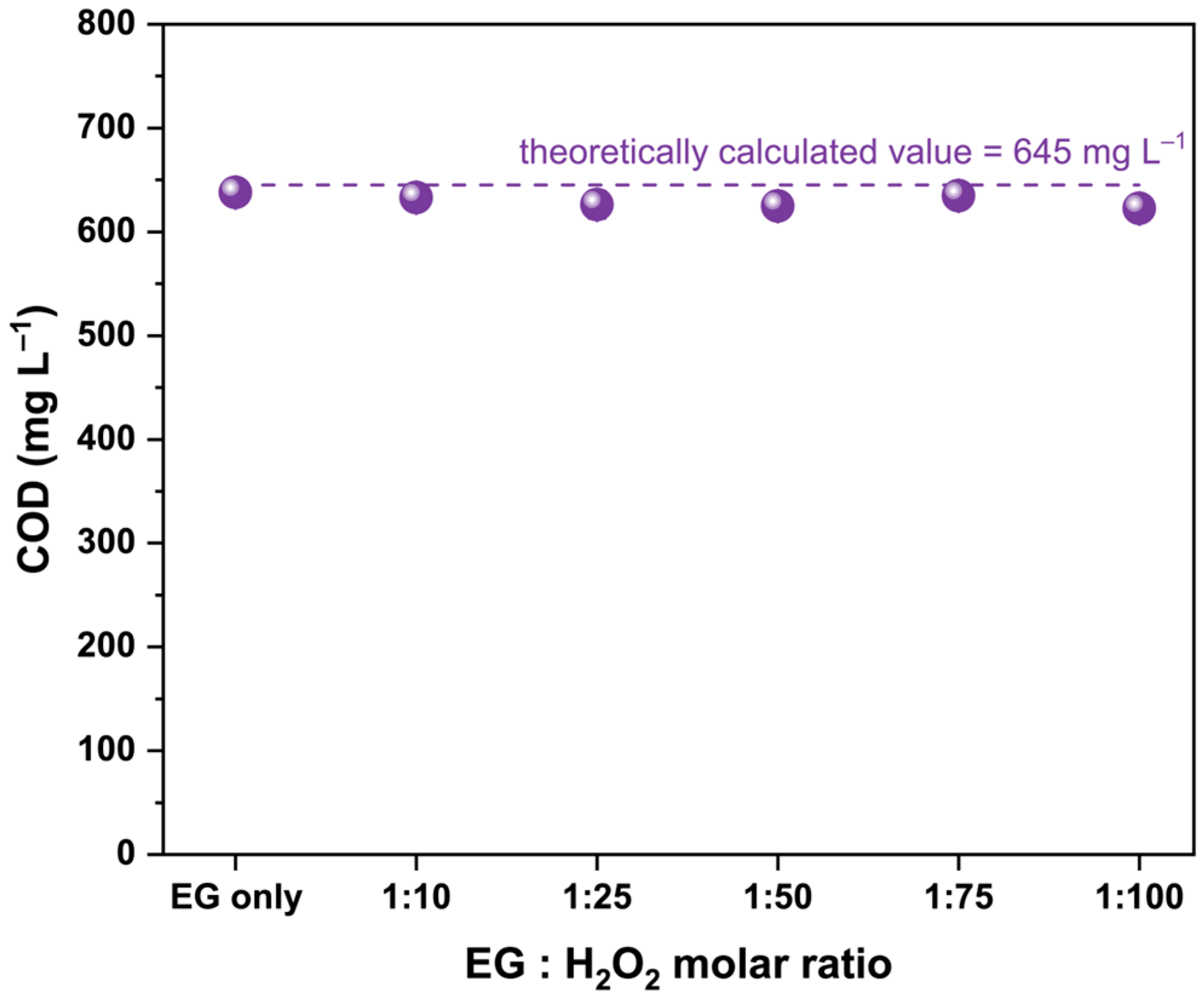

2.1. Effect of EG:H2O2 Molar Ratio

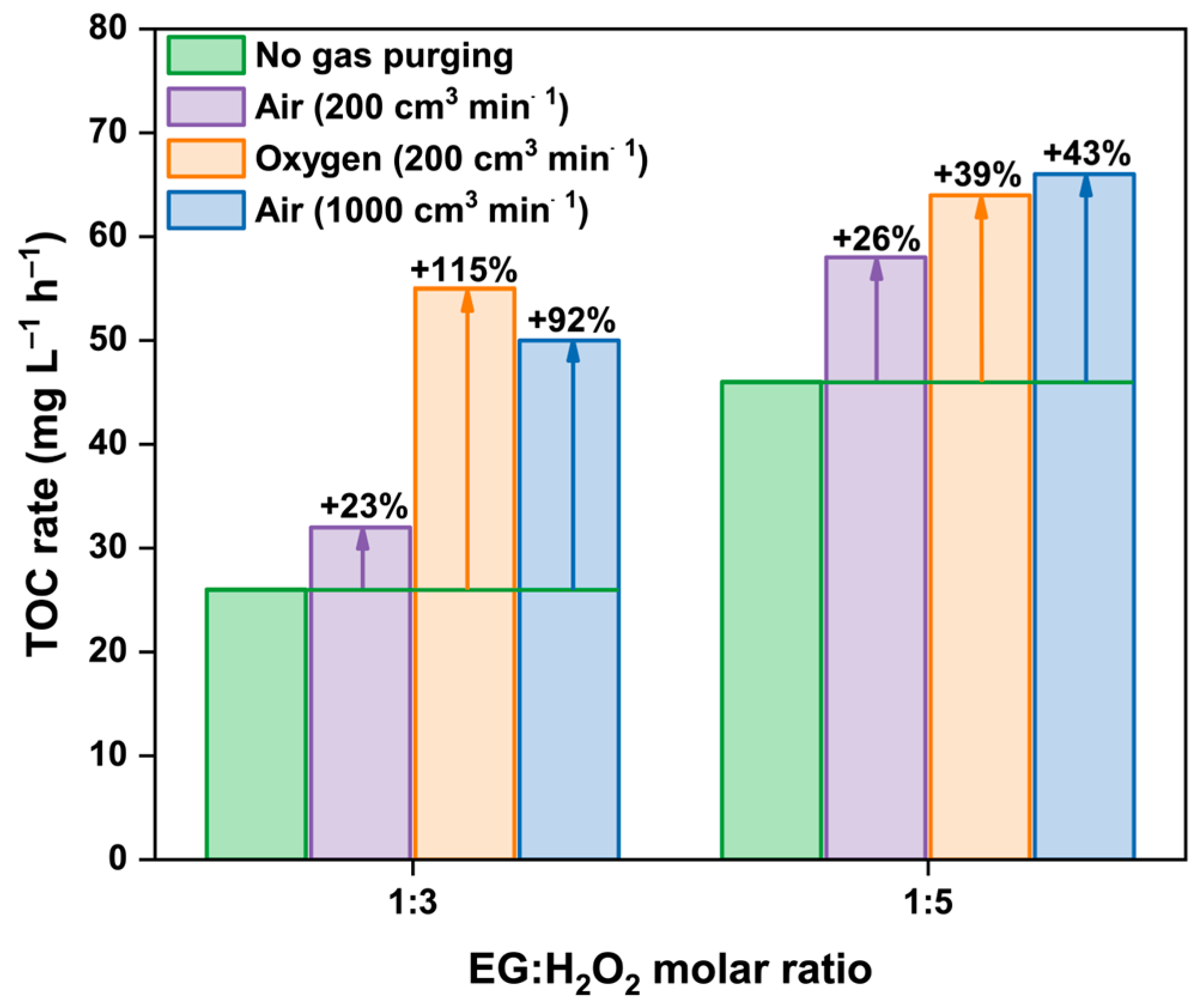

2.2. Intensification of Oxydation Process

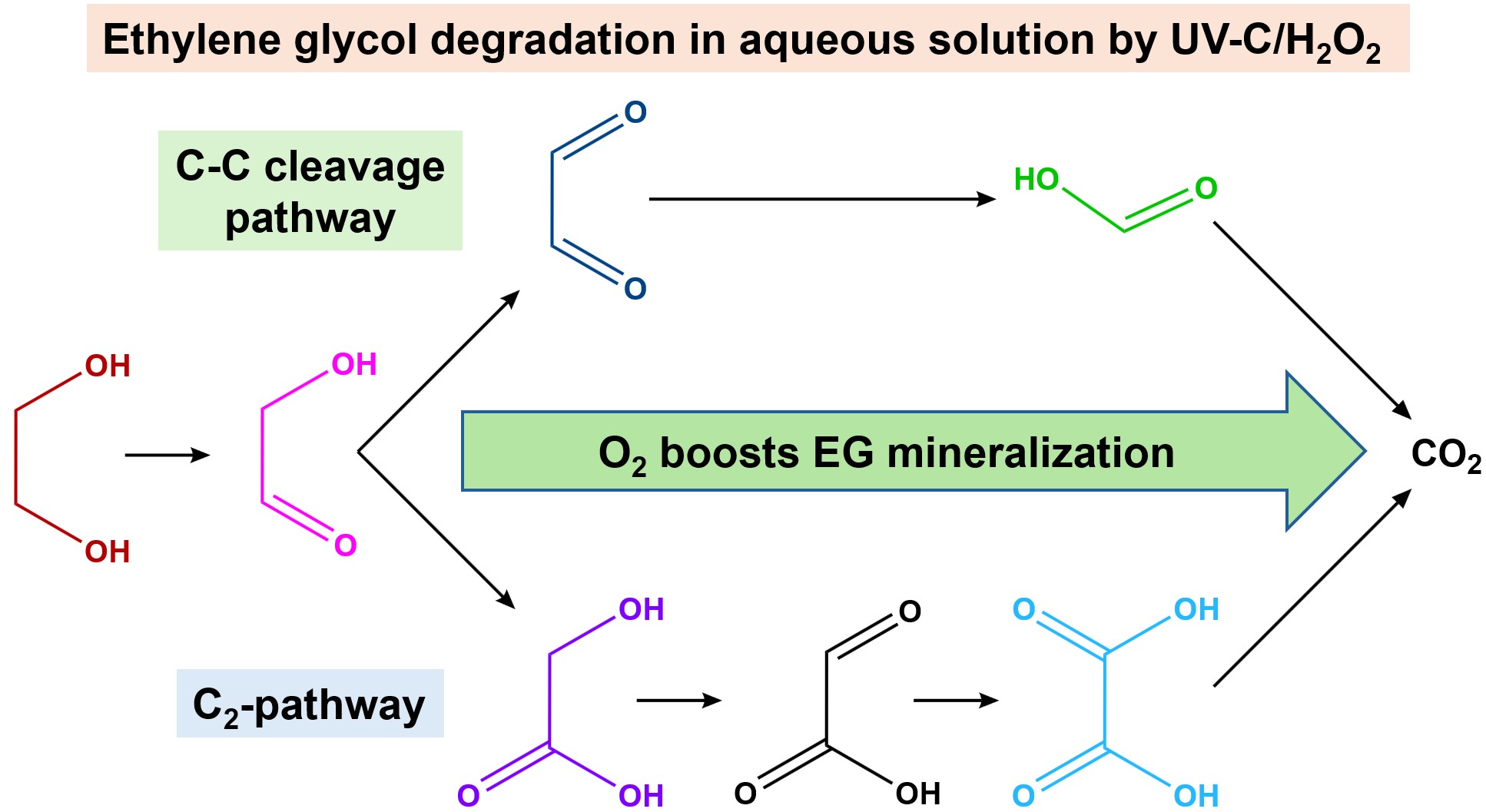

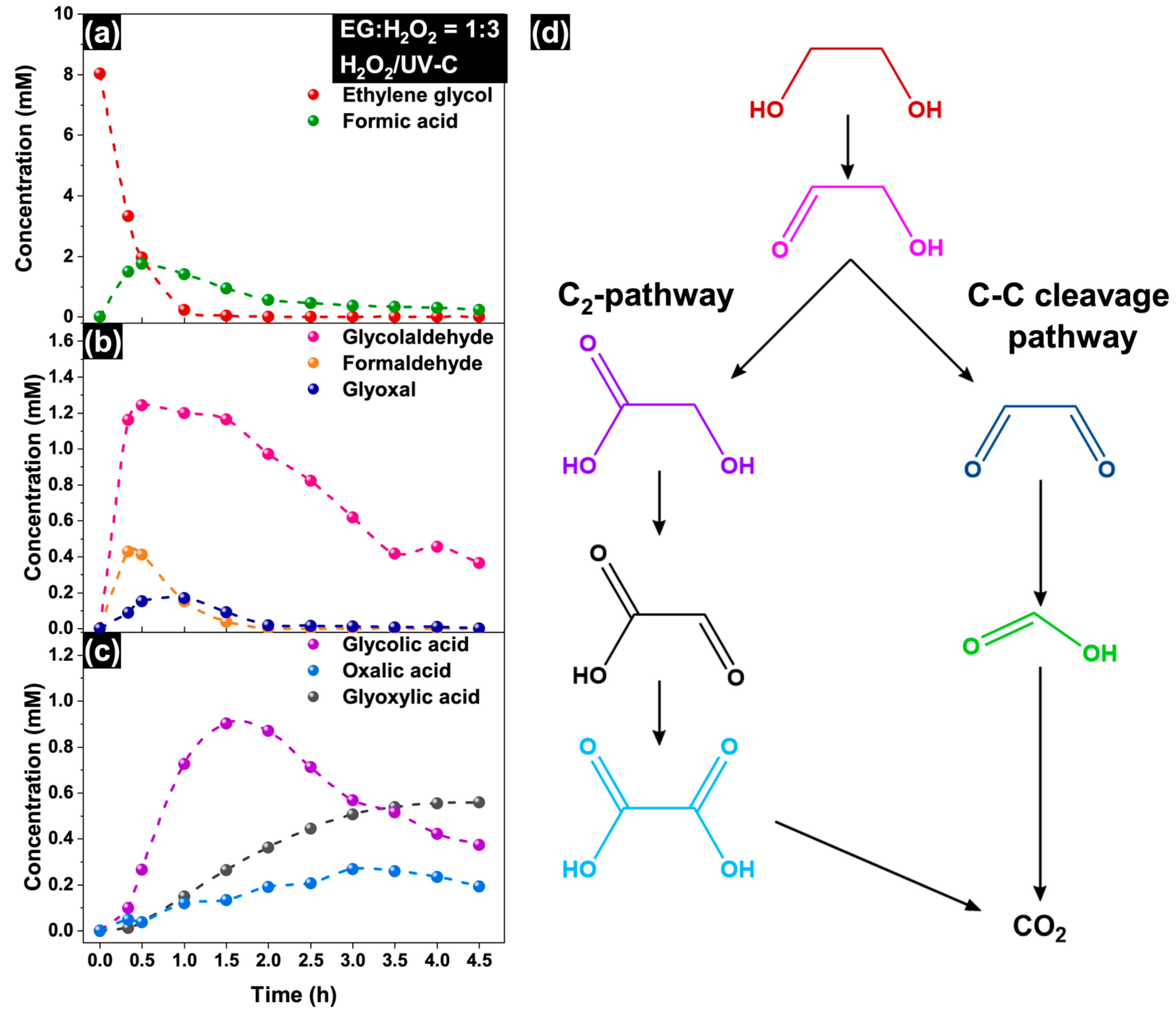

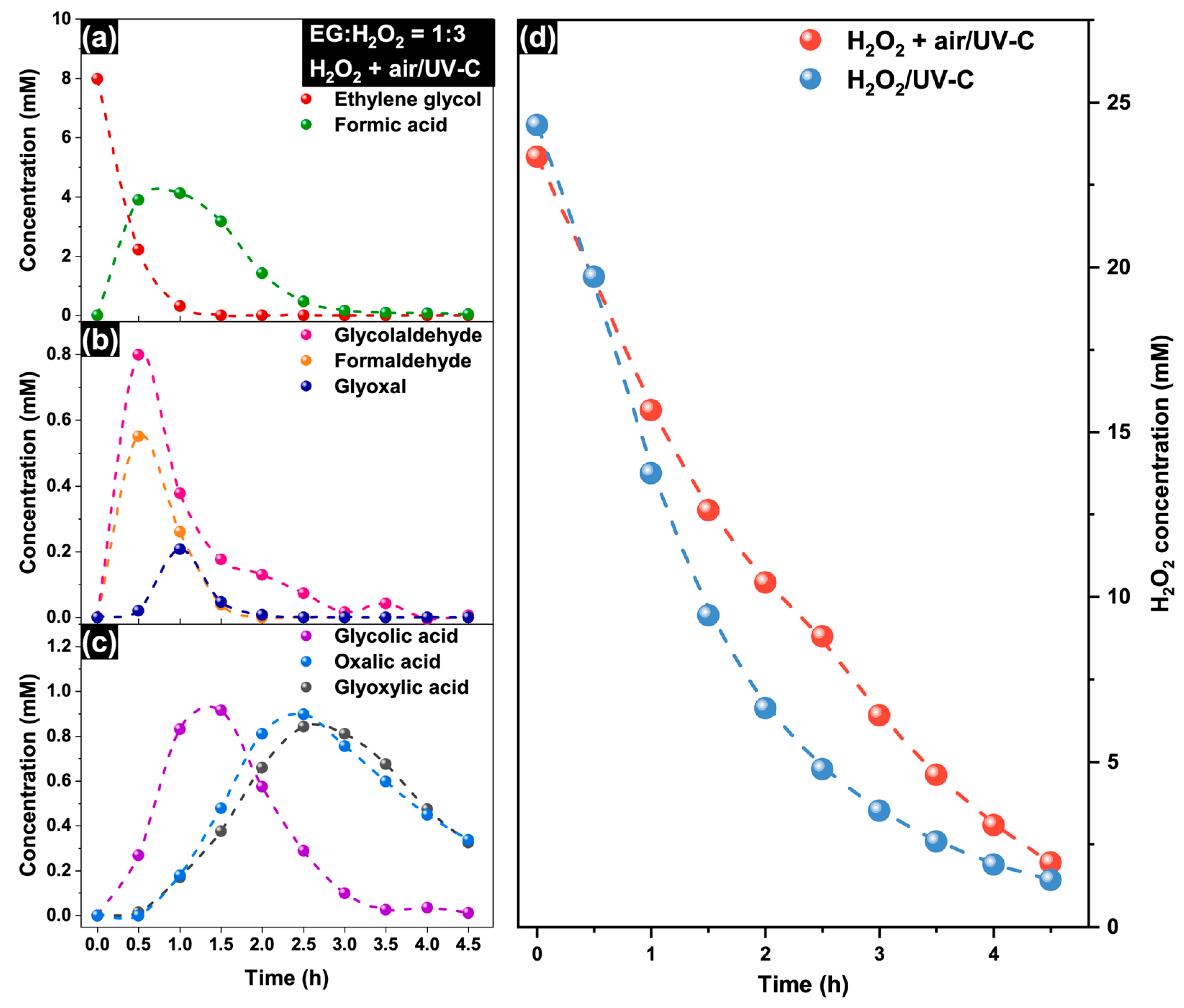

2.3. Mechanism of EG Degradation

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Air Passenger Traffic Evolution, 1980-2020 – Charts – Data & Statistics Available online:. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/world-air-passenger-traffic-evolution-1980-2020 (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Sulej, A.M.; Polkowska, Ż.; Namieśnik, J. Analysis of Airport Runoff Waters. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2011, 41, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Quilty, S.M.; Long, T.; Jayakaran, A.; Fay, L.; Xu, G. Managing Airport Stormwater Containing Deicers: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2017, 11, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMS1424S: Fluid, Aircraft Deicing/Anti-Icing, SAE Type I 2023.

- AMS1428L: Fluid, Aircraft Deicing/Anti-Icing, Non-Newtonian (Pseudoplastic), SAE Types II, III, and IV 2023.

- Environmental Impact and Benefit Assessment for the Final Effluent Limitation Guidelines and Standards for the Airport Deicing Category. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2012.

- Johnson, E.P. Aircraft De-Icer: Recycling Can Cut Carbon Emissions in Half. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2012, 32, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, S.; Covington, J.; Tamulonis, C. Preliminary Data Summary Airport Deicing Operations (Revised). United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington.

- Staples, C.A.; Williams, J.B.; Craig, G.R.; Roberts, K.M. Fate, Effects and Potential Environmental Risks of Ethylene Glycol: A Review. Chemosphere 2001, 43, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, S.I.; Jordahl, D.M.; Evans, J.E.; May, E.B. Toxicity of Aircraft De-icer and Anti-icer Solutions to Aquatic Organisms. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 1995, 14, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, M.K.; Baltz, D.M.; Chesney, E.J.; Tarr, M.A.; Kolok, A.S. Swimming Performance of Juvenile Florida Pompano Exposed to Ethylene Glycol. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 2002, 131, 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillard, D.A. Comparative Toxicity of Formulated Glycol Deicers and Pure Ethylene and Propylene Glycol to Ceriodaphnia Dubia and Pimephales Promelas. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 1995, 14, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, L.J.; Holtze, K.; Kent, R.A.; Jefferson, C.; Anderson, D. Acute Toxicity of Storm Water Associated with De-icing/Anti-icing Activities at Canadian Airports. 2000, 19, 1846–1855. [CrossRef]

- Corsi, S.R.; Geis, S.W.; Loyo-Rosales, J.E.; Rice, C.P. Aquatic Toxicity of Nine Aircraft Deicer and Anti-Icer Formulations and Relative Toxicity of Additive Package Ingredients Alkylphenol Ethoxylates and 4,5-Methyl-1H-Benzotriazoles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7409–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillard, D.A.; DuFresne, D.L. Toxicity of Formulated Glycol Deicers and Ethylene and Propylene Glycol to Lactuca Sativa, Lolium Perenne, Selenastrum Capricornutum, and Lemna Minor. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exton, B.; Hassard, F.; Medina-Vaya, A.; Grabowski, R.C. Undesirable River Biofilms: The Composition, Environmental Drivers, and Occurrence of Sewage Fungus. Ecological Indicators 2024, 161, 111949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exton, B.; Hassard, F.; Medina Vaya, A.; Grabowski, R.C. Polybacterial Shift in Benthic River Biofilms Attributed to Organic Pollution – a Prospect of a New Biosentinel? Hydrology Research 2023, 54, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, M.A.; Driscoll, H.E.; Takeda, M.; Vangala, M.; Corsi, S.R.; Tighe, S.W. Advanced biofilm analysis in streams receiving organic deicer runoff. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Tarun, P.K.; Shih, D.T.; Kim, S.B.; Chen, V.C.P.; Rosenberger, J.M.; Bergman, D. Data Mining Modeling on the Environmental Impact of Airport Deicing Activities. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 14899–14906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski, M. History, Processing, and Usage of Recycled Glycol for Aircraft Deicing and Anti-Icing. 2001.

- Stankevičienė, R.; Survilė, O.; Šaulys, V.; Bagdžiūnaitė-Litvinaitienė, L.; Litvinaitis, A. The Treatment and Handling Systems of de/Anti-Icing Contaminants Which Generated and Discharged into Surface Runoff from Airports Territories /. Journal of water security. 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, S.; Davis, L.C.; Erickson, L.E. Natural, Cost-effective, and Sustainable Alternatives for Treatment of Aircraft Deicing Fluid Waste. Environ. Prog. 2005, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Proceedings of Taal 2007 2008, 965–980. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg, T.; Veltman, S.; Switzenbaum, M. Kinetics of Anaerobic Degradation of Glycol-Based Type I Aircraft Deicing Fluids. Biodegradation 2001, 12, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.L.; Dameera, V.; Chowdhury, A.; Juvekar, V.A.; Sarkar, A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Ethylene Glycol in a Channel Flow Reactor. Catalysis Today 2018, 309, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardak, K.; Dirany, A.; Drogui, P.; El Khakani, M.A. Electrochemical Degradation of Ethylene Glycol in Antifreeze Liquids Using Boron Doped Diamond Anode. Separation and Purification Technology 2016, 168, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araña, J.; Ortega Méndez, J.A.; Herrera Melián, J.A.; Doña Rodríguez, J.M.; González Díaz, O.; Pérez Peña, J. Thermal Effect of Carboxylic Acids in the Degradation by Photo-Fenton of High Concentrations of Ethylene Glycol. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2012, 113–114, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan-Ertas, T.; Gurol, M.D. Oxidation of Diethylene Glycol with Ozone and Modified Fenton Processes. Chemosphere 2002, 47, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrick McGinnis, B.; Dean Adams, V.; Joe Middlebrooks, E. Degradation of Ethylene Glycol Using Fenton’s Reagent and UV. Chemosphere 2001, 45, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauson, D.; Preis, S. The Influence of Iron Ions on the Aqueous Photocatalytic Oxidation of Deicing Agents. International Journal of Photoenergy 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Hoffmann, M.R. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Degradation of Ethylene Glycol and Propylene Glycol. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 25, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimin, Yu.S.; Trukhanova, N.V.; Strel’tsova, I.V.; Komissarov, V.D. Kinetics of Polyol Oxidation by Ozone in Aqueous Solutions. Kinetics and Catalysis 2000, 41, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieyan, S.G.; Marahel, F.; Ghaedi, M.; Maleki, A. Degradation of Mono Ethylene Glycol Wastewater by Different Treatment Technologies for Reduction of COD Gas Refinery Effluent. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2024, 104, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Ahmad, A.; Das, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Dutta, B.K. Efficacious Degradation of Ethylene Glycol by Ultraviolet Activated Persulphate: Reaction Kinetics, Transformation Mechanisms, Energy Demand, and Toxicity Assessment. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 85071–85086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario-Ortiz, F.L.; Wert, E.C.; Snyder, S.A. Evaluation of UV/H2O2 Treatment for the Oxidation of Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater. Water Research 2010, 44, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, S.; Yoon, Y.; Jung, Y.; Hwang, T.-M.; Lee, J.; Kang, J.-W. Comparative Evaluation of Ibuprofen Removal by UV/H2O2 and UV/S2O82− Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 269, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.A.; Huie, R.E.; Koppenol, W.H.; Lymar, S.V.; Merényi, G.; Neta, P.; Ruscic, B.; Stanbury, D.M.; Steenken, S.; Wardman, P. Standard Electrode Potentials Involving Radicals in Aqueous Solution: Inorganic Radicals (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2015, 87, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendjelloul, R.; Bensmaili, A.; Berkani, M.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Vasseghian, Y.; Appasamy, D.; Kadmi, Y. Efficient H2O2 -Sonochemical Treatment of Penicillin G in Water: Optimization, DI-HRMS Ultra-Trace by-Products Analysis, and Degradation Pathways. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2024, 185, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.; He, X.; Shah, N.S.; Khan, H.M.; Hapeshi, E.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Dionysiou, D.D. Kinetic and Mechanism Investigation on the Photochemical Degradation of Atrazine with Activated H2O2, S2O82− and HSO5−. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 252, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokare, A.D.; Choi, W. Review of Iron-Free Fenton-like Systems for Activating H2O2 in Advanced Oxidation Processes. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2014, 275, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J.; Lodh, B.K.; Sharma, R.; Mahata, N.; Shah, M.P.; Mandal, S.; Ghanta, S.; Bhunia, B. Advanced Oxidation Process for the Treatment of Industrial Wastewater: A Review on Strategies, Mechanisms, Bottlenecks and Prospects. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, E.A.; Santos, G.M.; Marson, E.O.; Mbié, M.J.; Paniagua, C.E.S.; Ricardo, I.A.; Starling, M.C.V.M.; Pérez, J.A.S.; Trovó, A.G. Performance of Different Peroxide Sources and UV-C Radiation for the Degradation of Microcontaminants in Tertiary Effluent from a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharekar, M.A.; Kaplan, M.M. Ultraviolet Photo-Oxidation Of Ethylene Glycol Laser Coolant By Laser Flashlamp. OE 1982, 21, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeldt, E.J.; Linden, K.G.; Canonica, S.; von Gunten, U. Comparison of the Efficiency of OH Radical Formation during Ozonation and the Advanced Oxidation Processes O3/H2O2 and UV/H2O2. Water Research 2006, 40, 3695–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varank, G.; Can-Güven, E.; Yazici Guvenc, S.; Garazade, N.; Turk, O.K.; Demir, A.; Cakmakci, M. Oxidative Removal of Oxytetracycline by UV-C/Hydrogen Peroxide and UV-C/Peroxymonosulfate: Process Optimization, Kinetics, Influence of Co-Existing Ions, and Quenching Experiments. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 50, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dual Strategies to Enhance Mineralization Efficiency in Innovative Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes Using Natural Air Diffusion Electrode: Improving Both H2O2 Production and Utilization Efficiency. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 413, 127564. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J. Understanding and Modeling the Formation and Transformation of Hydrogen Peroxide in Water Irradiated by 254 Nm Ultraviolet (UV) and 185 Nm Vacuum UV (VUV): Effects of pH and Oxygen. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde, H.J.V.D.; Sonntag, C. v. The U.V. Photolysis (λ = 185nm) of Ethylene Glycol in Aqueous Solution. Photochemistry and Photobiology 1971, 13, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vel Leitner, N.K.; Dore, M. Hydroxyl Radical Induced Decomposition of Aliphatic Acids in Oxygenated and Deoxygenated Aqueous Solutions. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 1996, 99, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vel Leitner, N.K.; Doré, M. Mecanisme d’action Des Radicaux OH Sur Les Acides Glycolique, Glyoxylique, Acetique et Oxalique En Solution Aqueuse: Incidence Sur La Consammation de Peroxyde d’hydrogene Dans Les Systemes H2O2/UV et O3/H2O2. Water Research 1997, 31, 1383–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, A.G.; Turpin, B.J.; Altieri, K.E.; Seitzinger, S.; Reff, A.; Lim, H.-J.; Ervens, B. Atmospheric Oxalic Acid and SOA Production from Glyoxal: Results of Aqueous Photooxidation Experiments. Atmospheric Environment 2007, 41, 7588–7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristova, N.A.; Karpel Vel Leitner, N.; Piskarev, I.M. Degradation of Formic Acid in Different Oxidative Processes. High Energy Chemistry 2002, 36, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, X.-Y. Deciphering the Aqueous Chemistry of Glyoxal Oxidation with Hydrogen Peroxide Using Molecular Imaging. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 20357–20366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, M.J.; Seitzinger, S.; Turpin, B.J. Secondary Organic Aerosol Production from Aqueous Photooxidation of Glycolaldehyde: Laboratory Experiments. Atmospheric Environment 2009, 43, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6060:1989 Water Quality - Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand; 1989.

| Reagent | Model organism | Indicator | Concentration (mg L–1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene glycol | Ceriodaphnia dubia | 48-h LC50 | 34440 | [12] |

| IC25 | 12310 | |||

| Type I ADF | 48-h LC50 | 13140 | ||

| IC25 | 3960 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | Pimephales promelas | 48-h LC50 | 81950 | |

| IC25 | 22520 | |||

| Type I ADF | 48-h LC50 | 8540 | ||

| IC25 | 3660 | |||

| Type I ADF | Ceriodaphnia dubia | 48-h LC50 | 15700 | [14] |

| IC25 | 5470 | |||

| Type IV ADF | 48-h LC50 | 449 | ||

| IC25 | 113 | |||

| Type I ADF | Pimephales promelas | 96-h LC50 | 24700 | |

| IC25 | 4430 | |||

| Type IV ADF | 96-h LC50 | 371 | ||

| IC25 | 179 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | Selenastrum capricornutum | IC25 | 5340 | [15] |

| Type I ADF | 7610 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | Trachinotus carolinus | 24-h LC50 | >60000 | [11] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).