1. Introduction

In tumor surgery, extensive resections can be necessary to completely remove tumors. Additionally, necessary radiation therapy can result in (chronic) wounds, making defect reconstruction challenging. Alongside functionality, aesthetic outcomes are also important considerations. If standard methods along the reconstructive ladder like primary closure, free skin grafts, local flaps and pedicled flaps are unsuitable, new methods must be considered. For split- or full-thickness skin grafts for example, a vital wound ground is necessary. When the skull bone is exposed, these methods cannot be used and more complex reconstructions methods must be considered [

1,

2]. The more complex the reconstruction, the higher the perioperative risk, which should be evaluated critically, especially in elderly patients with relevant comorbidities. One relatively recent method is the use of dermal skin matrixes [

1].

There are several studies, that show promising results of using fish skin graft (FSG) in management of chronic wounds as a result of diabetes [

3], chronic venous insufficiency, peripheral arterial occlusive disease [

3] or burn wounds [

4,

5]. Recently our group presented a successful case of using FSG on a parietooccipital irradiated chronic wound with an exposed external table of the skull after several operations due to an squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Through FSG, it was possible to achieve granulation within one week and re-epithelialization after full-thickness-skin (FTSG) implantation [

6].

The FSG used in this study is a medical device derived from the Atlantic cod. The decellularized, lyophilized sterile fish skin provides a dermal matrix, very similar to human skin, which enables the ingrowth of dermal-/stem cells and angiogenesis to support granulation (3,7–9). In contrast to xenografts derived from bovine or porcine sources, there is no known risk of viral disease transmission and a higher acceptance in patients and clinicians due to less cultural or religious burden [

3,

7,

8].

The objective of this paper is to assess the effectiveness of FSG in achieving granulation and re-epithelialization in complex head and neck wound environments, particularly in pre-radiated regions with exposed skull bone. To further improve our implemented treatment regimen, we used FSG for the first time together with octenidine based products. This antiseptic has already demonstrated superior outcomes for split-thickness skin transplantation in high-risk patients [

9], as it not only prevents wound infections but also promotes vascularization. [

10]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Skin Graft

FSGs have emerged as a promising innovation in wound care, offering unique advantages over traditional wound dressings and graft materials. In 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a novel product, decellularized fish skin derived from the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) (Kerecis© Omega3 Wound™, Kerecis, Iceland). We used this medical device in our study. Unlike conventional options, such as porcine or bovine-derived matrices, FSGs retain their native structure and composition, including essential natural omega-3 fatty acids, without the need for antibiotics or virus-inactivating methods [

8].

2.2. Octenidine

For antiseptic treatment we used the medicinal product octenisept® (0.1% octenidine, 2% phenoxyethanol; Schülke & Mayr, Germany) for wound disinfection and octenilin® wound gel (octenidine, Hydroxyethylcellulose; Schülke & Mayr, Germany), a hydrogel to prevent FSG from dehydration. Both products contain the same well tolerated antiseptic active and are compatible with each other.

2.3. Wound Dressings & Suture Materials

Adaptic™ Touch Non-Adhering Silicone Dressing (Systagenix Wound Management, Gargrave, UK) is a flexible, non-adherent silicone wound contact layer used to protect wounds while minimizing trauma during dressing changes. The dressing's low-tack silicone design prevents adherence to the wound surface and allows atraumatic removal. Its open mesh structure supports fluid transfer to a secondary dressing, which reduces the risk of exudate pooling and subsequent maceration.[

11] 5-0 Monocryl suture was used for suturing. To ensure contact between the graft and the wound area a mattress suture with absorbable suture material was performed(4-0 Vicryl).

2.4. Patients

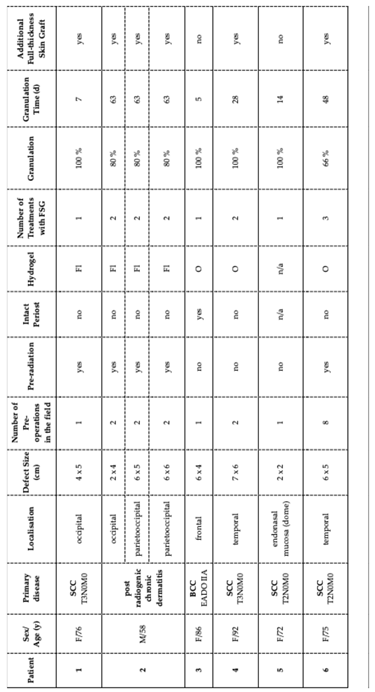

We describe eight defects on six patients (one male, 5 female), 58-92 years of age with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or post radiogenic chronic dermatitis as primary disease and therefore with indication for FSG. Three patients were treated with FSG using conventional protocol, for the others FSG was used in combination with an octendine-based hydrogel. Detailed demographics, wound aetiology, treatment locations, history of radiation, and outcomes are demonstrated in

Table 1. All patients gave their written and informed consent and the study was registered under researchregistry.org under UIN:researchregistry10815.

2.5. Treatment Protocol

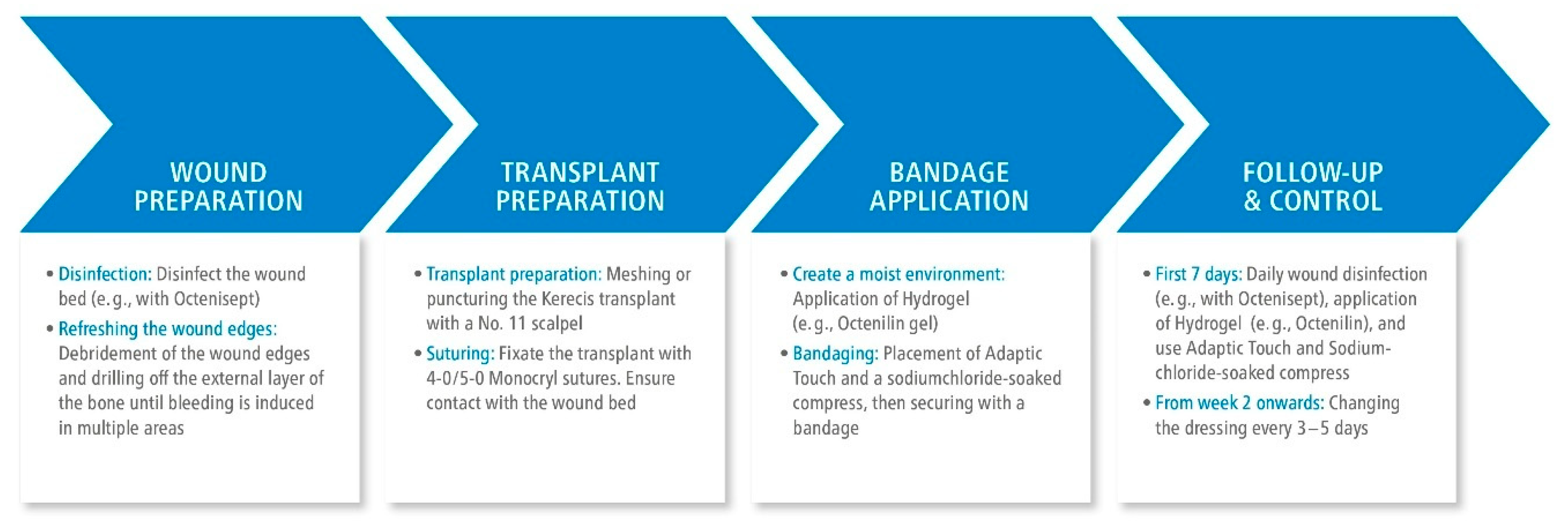

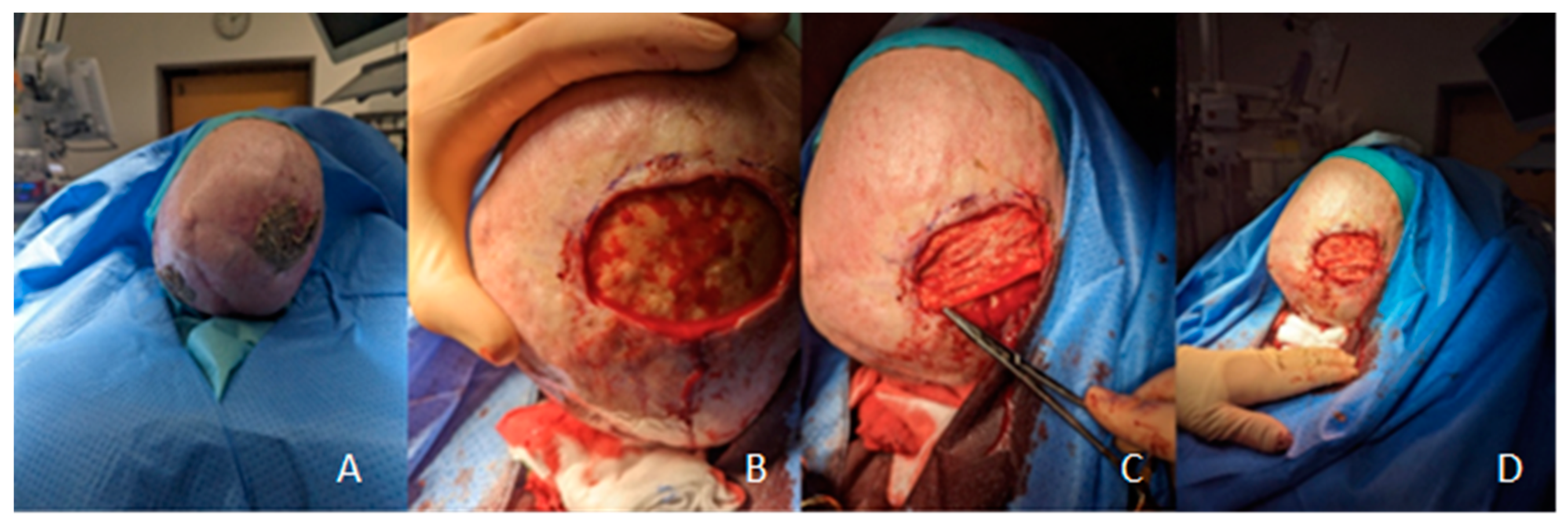

Depending on the underlying pathology, our regimen is based on following algorithm in

Figure 1 and additionally depicted in

Figure 2 showing

the preparation of wound area and grafting as well as the intraoperative procedure for one representative patient.

2.5.1. Exposed Skull

Firstly, necrotic tissue is resected, wound edges are freshened, and the external table is abraded extensively to the point of induced bleeding. To reduce possible bacterial colonization, the wound and surrounding skin is disinfected using the antiseptic solution. The FSG is then prepared, which means adapted according to the wound size and soaked in physiological saline solution for 3 minutes before it is meshed or punctured. 5-0 Monocryl suture is used for suing. The graft must be in contact with the wound ground, a plane relief must be achieved by drilling the external table. Afterwards, a moist environment is created using a hydrogel. The non-adherent wound dressing and a saline-soaked gauze is applied, followed by a compress dressing.

2.5.2. Mucosal Defects

The graft and the wound ground are prepared as described in

Section 2.5.1., 5-0 Monocryl suture is used for suturing. To ensure close contact between the FSG and the wound area we use a mattress suture with absorbable suture material (4-0 Vicryl). No hydrogel application is performed.

2.5.3. Postoperative Treatment

During the first week, dressing change is performed daily, according to the intraoperative protocol consisting of the hydrogel, a non-adherent wound dressing, a saline-soaked gauze on top which is finally fixed with a compress dressing. In the following week, the entire dressing is changed every two to five days. Two weeks after the transplantation, the wound is evaluated by the surgeon to determine if granulation tissue formation is adequate for secondary wound healing or, due to insufficient granulation, either another FSG is needed or full-thickness skin graft can be transplanted.

Hydration and sterility of the recipient site is important throughout the whole period, in order to prevent graft loss due to dehydration or infection. These specifications are guaranteed by using both octenidine containing products.

2.6. Statistics

Influence of pre-radiation on outcome and time to granulation is analyzed by performing Mann-Whitney U test.

3. Results

The included patients presented chronic wounds due to following primary diagnoses: four cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), one case of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and three defects (in one patient) due to post-radiogenic chronic dermatitis following complex BCC treatment. The locations were as following: two cases in the parietooccipital region, two in the occipital region, two in the temporal region, one in the frontal region, and one in the dome affecting the endonasal mucosa. The size of defects varied from 4x5 cm in the occipital region, 2x4 to 6x6 cm in the parietooccipital region, 6x4 cm in the frontal region, 2x2 cm endonasally in the dome and nasal mucosa to 6x5 to 7x6 cm in the temporal region. Four patients already underwent surgeries in the affected field prior to the here described protocol, with two even multiple procedures. Pre-radiation therapy was performed on three patients. Needed FSG treatments ranged from one to three applications across patients. Granulation levels varied, with four patients who achieved 100% and two achieved 66-80% within 5 to 63 days. Three patients required additional full-thickness-skin grafts (FTSG), whereas re-epithelization was achieved in two cases without FTSG transplantation. To evaluate any possible additional advantages, we modified the regimen by using the octenidine-based hydrogel in three consecutive patients.

In

Table 1 we summarize both the patients' anamnesis and treatment procedures as well as the follow up after FSG transplantation.

Patients who underwent radiation therapy experienced longer granulation times up to 63 days, achieved lower levels of granulation (66-80%) and required all additional FTSG transplantation.

Otherwise, in the here studied non-irradiated patients, time to granulation was typically faster, ranging from 5 to 28 days. The fastest time until full granulation within only 5 days was observed in a non-irradiated patient with intact periosteum, treated additionally with octenilin wound gel. Although all presented individuals were associated with poor prognosis for uncomplicated wound healing, both protocols – octenisept® and Flaminal® forte or octenisept® and octenilin® gel – achieved highly satisfying results when combined with FSG transplantation.

Time to granulation is compared between irradiated and non-irradiated tissues by perfoming a statistical analysis:

- -

Irradiated Tissue (n=5): Median granulation time was 48 days.

- -

Non-Irradiated Tissue (n=3): Granulation occurred with a median time of 14 days.

- -

Mann-Whitney U Test: U = 0.33, p = 0.083 (non-significant at p < 0.05).

Key findings show that irradiated wounds generally took longer to granulate (median = 48 days) compared to non-irradiated wounds (14 days). Two irradiated cases required secondary FSG grafting.

Qualitative Observations

Photographic documentation demonstrated that wound bed conditions improved significantly following FSG application. Patients treated with octenilin® gel showed favourable healing outcomes, including quicker granulation time, suggesting that octenidine may play a role in optimizing the wound environment and reducing the need for secondary procedures.

Figure 3.

Patient #3 defect after FSTG failure and following FSG implantation with intact periost and consecutive full-epithelization without contracture after 6 weeks in follow-up (A-E). (A): intraoperatively prior FSG implantation (B) intraoperative after FSG implantation, (C) 18 days after FSG implantation, (D) day 28, (E) six weeks postoperative without contracture and full epithelization .

Figure 3.

Patient #3 defect after FSTG failure and following FSG implantation with intact periost and consecutive full-epithelization without contracture after 6 weeks in follow-up (A-E). (A): intraoperatively prior FSG implantation (B) intraoperative after FSG implantation, (C) 18 days after FSG implantation, (D) day 28, (E) six weeks postoperative without contracture and full epithelization .

Figure 4.

Patient #1 without periost (intraoperatively A-C), presented full granulation after 7 days (D), received FSTG transplant (E) condition three months post surgery) and (F) one year postoperative [

1].

Figure 4.

Patient #1 without periost (intraoperatively A-C), presented full granulation after 7 days (D), received FSTG transplant (E) condition three months post surgery) and (F) one year postoperative [

1].

Figure 5.

Patient #4 with full granulation after 28 days and epithelisation after FTSG after 32 days (A-F). (A) temporal T3 SCC, (B) intraoperative after resection, (C) failure of first FSG due to a lack of hydrogel, (D) full granulation after second FSG after 28 days, (E) preoperative before FTSG implantation, (F) 32 days after second FSG transplantation and 4 days after FTSG implantation .

Figure 5.

Patient #4 with full granulation after 28 days and epithelisation after FTSG after 32 days (A-F). (A) temporal T3 SCC, (B) intraoperative after resection, (C) failure of first FSG due to a lack of hydrogel, (D) full granulation after second FSG after 28 days, (E) preoperative before FTSG implantation, (F) 32 days after second FSG transplantation and 4 days after FTSG implantation .

4. Discussion

Our study provides insights into the effectiveness of fish skin graft (FSG) transplantation combined with octenidine-based wound management in complex and chronic wounds in the head and neck region. We observed notable differences in wound healing outcomes between irradiated and non-irradiated tissues, with additional observations suggesting that the type of antiseptic regimen could influence granulation time and healing quality.

Since FSG is a new therapeutic option, there are no standardized or established treatment protocols regarding peri- and postoperative management available. Current studies primarily aim to assess the effectiveness of FSG rather than to develop an optimal treatment algorithm, and the methodology is often insufficiently described in literature. Variations, particularly in perioperative treatment, are therefore likely, making the outcome of different publications difficult to compare. Until now, particularly in the head and neck region, the use of FSG remains largely unexplored. Most experience for therapeutic advances with FSG has been gained in the treatment of chronic venous or diabetic ulcers. [

12,

13,

14,

15]

Tickner et al. recently provided general recommendations for FSG, based on expert consensus. They emphasize adequate wound bed preparation through specific debridement, avoiding graft application on untreated infections, and ensuring graft hydration with saline for optimal wound contact. FSG should be meshed to prevent seroma, fixed in place, and covered with a non-adherent dressing, with weekly outpatient evaluations recommended. Furthermore, these authors suggest FSG as bridge therapy for more complex wounds, while smaller wounds may heal using only FSG. FSG is also effective for wounds with exposed bone, and negative pressure wound therapy (75–125 mm Hg) is considered beneficial, even though it can be problematic in the head and neck region. [

16]

Dorweiler et al.’s multicenter report illustrates the lack of standardized protocols for FSG transplantation across hospitals. After initial debridement, FSG was used and protected with foam dressings or the additional application of negative pressure therapy. Dressing changes varied from 2-3 days to weekly. Promising results were reported, however with a wide range of matrices applied per patient.[

17] Similarly, Kim et al. used absorptive foam dressings on the FSG, but further details on the protocol were not provided. [

5]

This variation in protocols and lack of detailed reporting makes it challenging to assess the effectiveness of specific FSG steps of treatment. The integration of an octenidine-based hydrogel in the wound regimen yielded promising results as patients showed increased level of granulation and a reduced risk for another FSG procedure.

In the discipline of head and neck surgery, FSG is still uncommon, but Wang et al. [

18] recently documented its use for periocular reconstruction after tumor excision in six patients. Parts of their procedure—freshening wound edges, meshing the FSG and soaked in saline, suturing the graft—parallels our approach. In contrast, they used FSG for deep defects, securing them with a bolster for two weeks and prescribed the antibiotic erythromycin used as ointment for a month to protect the graft from infection. The authors found that FSG is an effective option for functional and cosmetic outcomes in this area. Even though not statistically significant our results indicate that non-irradiated wounds are associated with shortened time to granulation, [

19] an effect that was further improved when adding octenidine to the regimen. Beyond antiseptic efficacy, this molecule was recently associated with additional characteristics, like anti-inflammatory effects and a positive influence on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), both important factors especially in treatment of hard to heal wounds. [

20,

21]

For future studies, we recommend focussing on standardizing FSG treatment protocols, particularly in complex head and neck reconstruction, to allow comparison and improve clinical outcomes. Studies should further investigate the role of antiseptics used for wound bed preparation, and their effects on healing, especially in patients associated with different complication factors.

Another interesting aspect is the low level of wound contracture in secondary healing when FSG was used, which could be a relevant secondary end point in other studies. Additionally, exploring advanced wound assessment tools could be valuable. We aim to evaluate the different phases of healing in FSG-treated wounds using hyperspectral imaging analysis in an upcoming project, which may provide more objective insights into wound perfusion and progress of granulation. This approach could be useful for more tailored and responsive treatment strategies in the future.

5. Conclusions

In line with findings from Veitinger et al. from our study group and Wang et al., our study demonstrates promising results for using FSG in head and neck reconstruction. Some experts already propose to update the traditional reconstructive ladder and to include dermal matrices as an option before considering free or local flaps [

1].

Our study presents a novel treatment protocol including a modern antiseptic molecule for wound bed preparation. Octenidine seems to support granulation and reduces additionally needed interventions in non-irradiated patients.

Author Contributions

The main authors, Lukas S. Fiedler (LSF) and Greta Zweigart (GZ), were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study and took the lead in drafting the manuscript. Burkard M. Lippert (BML), Christoph Klaus (CK), and Michaela Plath (MP) contributed to the development of the study protocol, data analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript. The individual contributions of the authors are as follows: Conceptualization: L.S.F. and G.Z. Methodology: L.S.F. and G.Z. Validation: B.M.L., C.K., and M.P. Formal Analysis: L.S.F. Investigation: L.S.F., G.Z., and C.K. Resources: L.S.F. , G.Z. and B.M.L. Data Curation: C.K. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: L.S.F. and G.Z. Writing—Review & Editing: B.M.L., C.K., and M.P. Visualization: G.Z. Supervision: B.M.L. Project Administration: L.S.F. and G.Z. Funding Acquisition: Not applicable. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Authorship is limited to those who have made a substantial contribution to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and registered under researchregistry10815 within researchregistry.org.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed, individual consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Janis, J.E.; Kwon, R.K.; Attinger, C.E. The new reconstructive ladder: modifications to the traditional model. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011, 127 (Suppl.1), 205s–212s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braza, M.F., MP;, Split-Thickness Skin Grafts. 2023, StatPearls; reasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Dardari, D., et al., Intact Fish Skin Graft to Treat Deep Diabetic Foot Ulcers. NEJM Evid, 2024: p. EVIDoa2400171. [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.M.; et al. New Medical Device and Therapeutic Approvals in Otolaryngology: State of the Art Review of 2021. OTO Open 2022, 6, 2473974x221126495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; et al. The Utility of Novel Fish-Skin Derived Acellular Dermal Matrix (Kerecis) as a Wound Dressing Material. Journal of Wound Management and Research 2021, 17, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitinger, A.B.; Lippert, B.M.; Fiedler, L.S. Resolution of a chronic occipital wound with exposed skull bone with a fish skin graft: a successful treatment approach. BMJ Case Rep 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnússon, S.; et al. [Decellularized fish skin: characteristics that support tissue repair]. Laeknabladid 2015, 101, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; et al. Regenerative and Antibacterial Properties of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts and Human Amnion/Chorion Membrane: Implications for Tissue Preservation in Combat Casualty Care. Mil Med 2017, 182, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiasek, J., et al., Outcomes for split-thickness skin transplantation in high-risk patients using octenidine. J Wound Care, 2015, 24(6 Suppl): p. S8, s10-2. [CrossRef]

- Goertz, O.; et al. Influence of topically applied antimicrobial agents on muscular microcirculation. Ann Plast Surg 2011, 67, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, J.B., S., Pagnamenta, F., Russell, F., Stringfellow,S., Cooper P. , Consensus guidance for the use of Adaptic Touch® non-adherent dressing. Wounds UK, 2011. 7(3).

- Ibrahim, M.; et al. Fish Skin Grafts Versus Alternative Wound Dressings in Wound Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e36348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luze, H.; et al. The Use of Acellular Fish Skin Grafts in Burn Wound Management-A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, R., 2nd, et al. Comparison of Intact Fish Skin Graft and Allograft as Temporary Coverage for Full-Thickness Burns: A Non-Inferiority Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12(3). [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, T. and M. Blatti, Faster Than Projected Healing in Chronic Venous and Diabetic Foot Ulcers When Treated with Intact Fish Skin Grafts Compared to Expected Healing Times for Standard of Care: An Outcome-Based Model from a Swiss Hospital. Int J Low Extrem Wounds, 2022: p. 15347346221096205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tickner, A.; et al. Consensus recommendations for optimizing the use of intact fish skin graft in the management of acute and chronic lower extremity wounds. Wounds 2023, 35, E376–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorweiler, B.; et al. The marine Omega3 wound matrix for treatment of complicated wounds: A multicenter experience report. Gefasschirurgie 2018, 23 (Suppl. 2), 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; et al. Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Treatment of Periocular Skin Defects. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 40, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormand, E.L.; Banwell, P.E.; Goodacre, T.E. Radiotherapy and wound healing. Int Wound J 2005, 2, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiser, S.; et al. Octenidine-based hydrogel shows anti-inflammatory and protease-inhibitory capacities in wounded human skin. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiser, S.; et al. Comparative assessment of commercially available wound gels in ex vivo human skin reveals major differences in immune response-modulatory effects. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 17481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).