Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Understanding Hyponatremia in Older Adults

-

Overview of Sodium Balance and Regulation in the BodySerum sodium is vital for maintaining fluid balance, regulating nerve and muscle cell function, and facilitating the transport of substrate across membranes.[7] Its critical roles influence hyponatremia's acute and chronic manifestations. A rapid decrease in serum sodium within 48 hours can lead to symptoms such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, and potentially progress to seizures and coma.[1] Chronic hyponatremia can manifest as fatigue, cognitive impairment, and gait deficits, leading to falls, osteoporotic fractures, and many associated symptoms.[12,13,14,15,16]

-

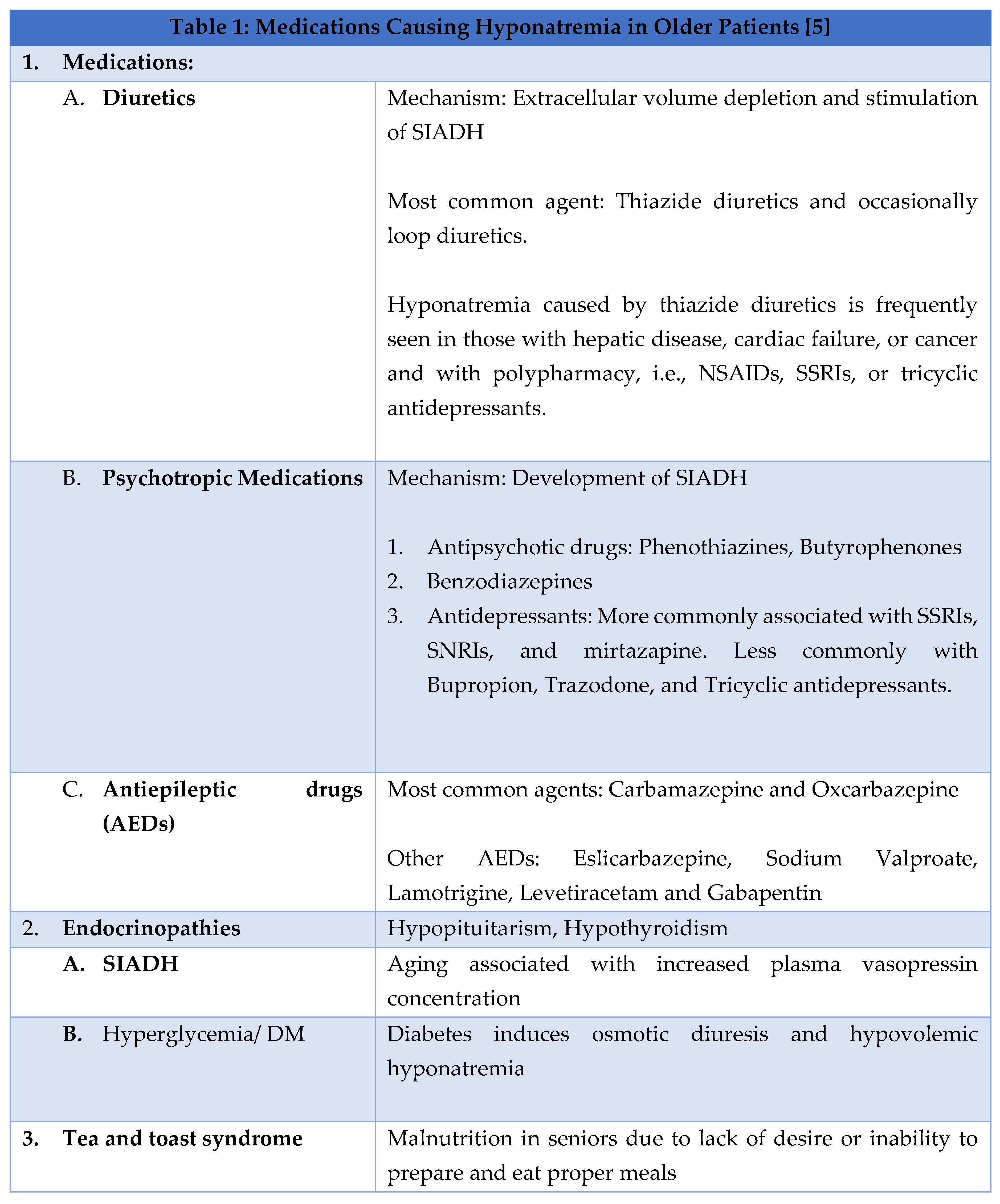

Factors Contributing to Hyponatremia in the older adultAge is an independent risk factor for hyponatremia in older adults, often due to medications, endocrinopathies, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and malnutrition, and at times leading to the development of 'tea and toast' syndrome.[1] Some common causes of hyponatremia are given in Table 1.

-

“Tea and Toast” HyponatremiaOne notable example of a dietary habit leading to malnutrition and hyponatremia in older adults is the “tea and toast” syndrome. Tea and toast are typically deficient in sodium, protein, and other vital nutrients. Older individuals whose primary diet consists of such a diet increase their risk of developing hyponatremia. [17] Such a dietary pattern is often seen in older adults with poor appetite, difficulty preparing meals, or limited access to diverse food sources. A “tea and toast” diet results in sodium depletion. This in combination with excessive water intake, results in dilution of sodium levels in the blood, creating fluid imbalance, causing hyponatremia. Additionally, protein deficiency in such diets exacerbates malnutrition, contributing further to sarcopenia and frailty.[18,19]

-

Hyponatremia and FallsHyponatremia that is symptomatic is readily diagnosed and managed. Mild chronic hyponatremia presents a more significant challenge because of its links to adverse outcomes. Hyponatremia increases the risks of falls by contributing to neurocognitive impairment, which can cause gait instability and decreased attention span.[20] This has substantial implications for geriatric care, as falls are a common medical concern among older adults.[21] Falls affect 30-60% of older adults living independently in the community yearly.[22] The outcomes of such falls in older adults can include hip fractures, hospitalizations, head injuries, and the need for admission to long-term care facilities.[21] Furthermore, prospective data from the Rotterdam Study demonstrated a significant association between baseline mild hyponatremia and recent falls, as well as both vertebral and incidental non-vertebral fractures.[12] Epidemiological and experimental evidence has shown that chronic mild hyponatremia is an independent risk factor for osteoporosis, as it increases bone osteoclastic activity in a hyponatremic environment.[23] Chronic mild hyponatremia is associated with extended hospital stays, functional independence, and increased mortality in individuals with chronic disease and those admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) settings.[12,23,24,25]

- 2.

- The Role of Dietary Habits in Hyponatremia

-

The Impact of Low Sodium Diets on Older AdultsLower dietary sodium intake amongst community-dwelling older adults was associated with poorer cognitive function, especially in those over 80. [27] . Cognitive impairments may affect executive functions, potentially impacting intermediate activities of daily living such as financial management. Given the risk of cognitive decline in older adults, even minor changes in cognitive ability because of low sodium intake could have significant health implications. Despite the known benefits of reducing dietary sodium for hypertension, the impact of hyponatremia on cognitive function underscores the need for further investigation.[28,29] Low nutritional sodium levels may negatively influence insulin regulation and the renin-angiotensin and sympathetic systems, potentially affecting cognitive function.[30,31,32] A recent study found a J-shaped relationship between sodium intake, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Individuals consuming more than 6 g of sodium per day and those consuming less than 3 g daily were found to have an increased risk of death and cardiovascular events.[33] Although further research is required, previous studies indicate a potential J-shaped relationship between sodium intake and cognitive function in older adults.[34,35,36] In a recent study involving older adults (average age 70 +- 12 years), adding a low-dose diuretic to angiotensin II receptor blockers for hypertension management significantly lowered serum sodium levels in individuals with low dietary salt intake.[37] As a result reducing dietary sodium intake to low levels may impair an individual's ability to maintain homeostasis, which could result in cognitive changes. This is especially concerning for older adults on medications that effect sodium levels. Reduced sodium intake has also been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events and mortality, regardless of blood pressure levels.[23,38]

-

Sodium-Rich Foods and Their Effects on HyponatremiaIncreased sodium intake elevates intra-glomerular pressure, which can contribute to or worsen chronic kidney damage, heightening the risk of progressive kidney disease.[39] High sodium intake is a recognized risk factor for developing such conditions. Specifically, in postmenopausal women in Korea,[36,38] excessive sodium intake (>2000 mg) was found to lead to increased urinary excretion (> 2 g/day), resulting in hypercalciuria and raising the risk of osteoporosis.[40] Additionally, excessive salt consumption has been linked to the development of hypertension[41,42] and, consequently, to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, particularly in individuals with hypertension and older adults.[23] Lowering sodium intake has been shown to reduce both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, especially in hypertensive and normotensive individuals.[41]

-

The Role of Ultra-Processed Foods in Sodium IntakeThe increased availability and consumption of ultra-processed foods has contributed to higher sodium intake in the general population. This increase is beyond the recommended dietary intake of sodium. Ultra-processed foods include packaged snacks, ready-to-eat meals, processed meats, instant noodles, and fast foods. These often contain high levels of added sodium to enhance the flavor and prolong shelf life. [43] This trend is concerning for older adults who have multiple chronic conditions (MCC), as excessive sodium intake from these foods can exacerbate hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and renal impairment.

- 3.

-

Nutritional Deficiencies and HyponatremiaAs people age, their metabolic and organ reserves universally decline. A diet that may be suitable for a young adult could become harmful for the same individual later in life. Failure to adjust diet and lifestyle accordingly can result in maladaptation, where the body struggles to compensate, leading to the development of various chronic conditions common in older adults, such as hypertension (HTN), diabetes (DM), cardiovascular disease (CVS), and chronic kidney disease (CKD).[44] According to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC), nearly half of all American adults, approximately 117 million individuals, have one or more chronic diseases that could be prevented with dietary improvements.[45] In an aging population, diet-induced health problems have a more significant impact due to reduced adaptability from age-related metabolic capacity and organ function declines. This contributes to the increased prevalence of chronic conditions like HTN, atherosclerotic vascular diseases, and CKD in older adults. Poor diets are the primary driver of the chronic disease burden in the United States. Currently, only 1% of Americans meet the criteria for ideal CVS health; 46% have HTN, around 50% have prediabetes or DM, and approximately 14% have CKD. Adjusting nutrient intake in the modern diet can mitigate risks of maladaptation, such as acid accumulation, excessive salt intake, potassium (K+) and fiber deficiency, and dehydration, significantly improving overall health.[44]

-

Protein Energy Malnutrition and Hyponatremia in the ElderlySarcopenia is an age-related decline in skeletal muscle mass and function.[28] The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) characterizes sarcopenia as a "progressive and widespread skeletal muscle condition linked to a higher risk of undesirable consequences, such as falls, fractures, physical impairment, and mortality.[57] Sarcopenia has an estimated prevalence of 9 to 18% in people aged sixty-five and older, increasing to 50% in those aged over eighty. Moreover, it has been postulated that beyond 50 years of age, muscle mass is lost at an approximate rate of 1-2% per year.[58] Some of the risk factors for sarcopenia include age, female sex, history of smoking, little to no exercise, particularly endurance training, and specific nutritional deficiencies.[57]

- b.

-

Hyponatremia-Related DeficienciesElectrolyte abnormalities are observed in a considerable percentage of hyponatremic patients independent of the cause of hyponatremia. In one study, more than half of patients with diuretic-induced hyponatremia exhibited at least one additional electrolyte abnormality.[62] Chronic diuretic usage is frequently associated with hyponatremia, which may also be linked to reduced intracellular potassium reserves. In a small group of patients with chronic congestive heart failure, magnesium replacement alone was sufficient to correct this hyponatremia.[63] The most common disorders associated with hyponatremia include hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia.

- 4.

-

Assessing adequate fluid intake in older adultsThere is no simple or universally accepted method for measuring hydration levels in older adults.[64] For example, HF patients may need to check daily weight, along with daily fluid intake and output, to ensure they are not retaining excess fluid. Similarly, individuals with chronic kidney stones must monitor their hydration levels to prevent stone formation, aiming for a daily urine output of 2.5 liters in adults.

- 5.

-

Broader Risk Factors and Consideration for Hyponatremia in Older AdultsAge-related physiological changes and dietary factors are key to the development of hyponatremia in older adults. Other significant factors that include hydration status, physical activity, chronic disease, socioeconomic status, healthcare coverage, and education levels.[1] Inadequate hydration can lead to hypernatremia, while excessive fluid intake may cause dilutional hyponatremia, especially in individuals with impaired kidney function or HF. It is important for older adults with impaired renal function or those taking medications that affect fluid balance to maintain a balance between fluid intake and sodium levels.[65]

- 6.

- Screening, Diagnosis, and Management of Hyponatremia in Older Adults

3. Results

4. Discussion: Recommendations for Managing Hyponatremia in Older Adults

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Filippatos TD, Makri A, Elisaf MS, Liamis G. Hyponatremia in the elderly: challenges and solutions. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1957-1965. [CrossRef]

- United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights. World Population Ageing.

- 2019: Highlights. 2019;ST/ESA/SER.A/430.

- Zhang X, Li XY. Prevalence of hyponatremia among older inpatients in a general hospital. Eur Geriatr Med. Aug 2020;11(4):685-692. [CrossRef]

- Soriano TA, DeCherrie LV, Thomas DC. Falls in the community-dwelling older adult: a review for primary-care providers. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(4):545-54. [CrossRef]

- Rondon H, Badireddy M. Hyponatremia. StatPearls. 2022.

- Peri A. Management of hyponatremia: causes, clinical aspects, differential diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. Jan 2019;14(1):13-21. [CrossRef]

- Strazzullo P, Leclercq C. Sodium. Adv Nutr. Mar 1 2014;5(2):188-90. [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake R, Oldmeadow C, McEvoy M, et al. Mild hyponatremia is associated with impaired cognition and falls in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. Oct 2013;61(10):1838-9. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC, et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing. Sep 2 2022;51(9)doi:10.1093/ageing/afac205.

- Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Epidemiology of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol. May 2009;29(3):227-38. [CrossRef]

- Soiza RL, Cumming K, Clarke JM, Wood KM, Myint PK. Hyponatremia: Special Considerations in Older Patients. J Clin Med. Aug 18 2014;3(3):944-58. [CrossRef]

- Renneboog B, Sattar L, Decaux G. Attention and postural balance are much more affected in older than in younger adults with mild or moderate chronic hyponatremia. Eur J Intern Med. Jun 2017;41:e25-e26. [CrossRef]

- Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X, Manto MU, Decaux G. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med. Jan 2006;119(1):71 e1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hoorn EJ, Rivadeneira F, van Meurs JB, et al. Mild hyponatremia as a risk factor for fractures: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. Aug 2011;26(8):1822-8. [CrossRef]

- Hoorn EJ, Liamis G, Zietse R, Zillikens MC. Hyponatremia and bone: an emerging relationship. Nat Rev Endocrinol. Oct 25 2011;8(1):33-9. [CrossRef]

- Gosch M, Joosten-Gstrein B, Heppner HJ, Lechleitner M. Hyponatremia in geriatric inhospital patients: effects on results of a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Gerontology. 2012;58(5):430-40. [CrossRef]

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. Oct 2013;126(10 Suppl 1):S1-42. [CrossRef]

- Robinson S, Granic A, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. The role of nutrition in the prevention of sarcopenia. Am J Clin Nutr. Nov 2023;118(5):852-864. [CrossRef]

- Robinson S, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Nutrition and sarcopenia: a review of the evidence and implications for preventive strategies. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:510801. [CrossRef]

- Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. Mar 2013;12(2):719-36. [CrossRef]

- McIntire KL, Hoffman AR. The endocrine system and sarcopenia: potential therapeutic benefits. Curr Aging Sci. Dec 2011;4(3):298-305. [CrossRef]

- Jo E, Lee SR, Park BS, Kim JS. Potential mechanisms underlying the role of chronic inflammation in age-related muscle wasting. Aging Clin Exp Res. Oct 2012;24(5):412-22. [CrossRef]

- (WHO) WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health. 2015.

- Lang T, Streeper T, Cawthon P, Baldwin K, Taaffe DR, Harris TB. Sarcopenia: etiology, clinical consequences, intervention, and assessment. Osteoporos Int. Apr 2010;21(4):543-59. [CrossRef]

- Kowal P, Chatterji S, Naidoo N, et al. Data resource profile: the World Health Organization Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Int J Epidemiol. Dec 2012;41(6):1639-49. [CrossRef]

- Adminstration USFD. Sodium in Your Diet. Accessed 10/10/2024, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/sodium-your-diet.

- Beaudart C, Zaaria M, Pasleau F, Reginster JY, Bruyere O. Health Outcomes of Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169548. [CrossRef]

- Stamler J. The INTERSALT Study: background, methods, findings, and implications. Am J Clin Nutr. Feb 1997;65(2 Suppl):626S-642S. [CrossRef]

- Cook NR. Salt intake, blood pressure and clinical outcomes. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. May 2008;17(3):310-4. [CrossRef]

- Patel SM, Cobb P, Saydah S, Zhang X, de Jesus JM, Cogswell ME. Dietary sodium reduction does not affect circulating glucose concentrations in fasting children or adults: findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr. Mar 2015;145(3):505-13. [CrossRef]

- Grassi G, Dell'Oro R, Seravalle G, Foglia G, Trevano FQ, Mancia G. Short- and long-term neuroadrenergic effects of moderate dietary sodium restriction in essential hypertension. Circulation. Oct 8 2002;106(15):1957-61. [CrossRef]

- Alderman MH, Madhavan S, Ooi WL, Cohen H, Sealey JE, Laragh JH. Association of the renin-sodium profile with the risk of myocardial infarction in patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med. Apr 18 1991;324(16):1098-104. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. Aug 14 2014;371(7):612-23. [CrossRef]

- Haring B, Wu C, Coker LH, et al. Hypertension, Dietary Sodium, and Cognitive Decline: Results From the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. Am J Hypertens. Feb 2016;29(2):202-16. [CrossRef]

- Fiocco AJ, Shatenstein B, Ferland G, et al. Sodium intake and physical activity impact cognitive maintenance in older adults: the NuAge Study. Neurobiol Aging. Apr 2012;33(4):829 e21-8. [CrossRef]

- Afsar B. The relationship between cognitive function, depressive behaviour and sleep quality with 24-h urinary sodium excretion in patients with essential hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. Mar 2013;20(1):19-24. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama M, Tomiyama H, Kuwajima I, et al. Low salt intake and changes in serum sodium levels in the combination therapy of low-dose hydrochlorothiazide and angiotensin II receptor blocker. Circ J. 2013;77(10):2567-72. [CrossRef]

- Park SM, Joung JY, Cho YY, et al. Effect of high dietary sodium on bone turnover markers and urinary calcium excretion in Korean postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Eur J Clin Nutr. Mar 2015;69(3):361-6. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki H, Takenaka T, Kanno Y, Ohno Y, Saruta T. Sodium and kidney disease. Contrib Nephrol. 2007;155:90-101. [CrossRef]

- Kim SW, Jeon JH, Choi YK, et al. Association of urinary sodium/creatinine ratio with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: KNHANES 2008-2011. Endocrine. Aug 2015;49(3):791-9. [CrossRef]

- Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Sacco RL, et al. Sodium, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease: further evidence supporting the American Heart Association sodium reduction recommendations. Circulation. Dec 11 2012;126(24):2880-9. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell M, Mente A, Yusuf S. Sodium intake and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. Mar 13 2015;116(6):1046-57. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Perez-Cueto FJA, Santos QD, et al. A Systematic Review of Behavioural Interventions Promoting Healthy Eating among Older People. Nutrients. Jan 26 2018;10(2). [CrossRef]

- Qian Q. Dietary Influence on Body Fluid Acid-Base and Volume Balance: The Deleterious "Norm" Furthers and Cloaks Subclinical Pathophysiology. Nutrients. Jun 16 2018;10(6). [CrossRef]

- Committee DGA. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. 2015.

- Millen BE, Abrams S, Adams-Campbell L, et al. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report: Development and Major Conclusions. Adv Nutr. May 2016;7(3):438-44. [CrossRef]

- Qian Q. Inflammation: A Key Contributor to the Genesis and Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Contrib Nephrol. 2017;191:72-83. [CrossRef]

- Maughan RJ. Impact of mild dehydration on wellness and on exercise performance. Eur J Clin Nutr. Dec 2003;57 Suppl 2:S19-23. [CrossRef]

- Siener R, Hesse A. Fluid intake and epidemiology of urolithiasis. Eur J Clin Nutr. Dec 2003;57 Suppl 2:S47-51. [CrossRef]

- Wang CJ, Grantham JJ, Wetmore JB. The medicinal use of water in renal disease. Kidney Int. Jul 2013;84(1):45-53. [CrossRef]

- Thornton SN. Increased Hydration Can Be Associated with Weight Loss. Front Nutr. 2016;3:18. [CrossRef]

- Leenders M, Boshuizen HC, Ferrari P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and cause-specific mortality in the EPIC study. Eur J Epidemiol. Sep 2014;29(9):639-52. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen B, Bauman A, Gale J, Banks E, Kritharides L, Ding D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause mortality: evidence from a large Australian cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. Jan 25 2016;13:9. [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, et al. Food Groups and Risk of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv Nutr. Nov 2017;8(6):793-803. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. Jul 29 2014;349:g4490. [CrossRef]

- Aaron KJ, Sanders PW. Role of dietary salt and potassium intake in cardiovascular health and disease: a review of the evidence. Mayo Clin Proc. Sep 2013;88(9):987-95. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. Jul 1 2019;48(4):601. [CrossRef]

- Karakousis ND, Kostakopoulos NA. Hyponatremia in the frail. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. Dec 2021;6(4):241-245. [CrossRef]

- Walston JD. Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. Nov 2012;24(6):623-7. [CrossRef]

- Bertini V, Nicoletti C, Beker BM, Musso CG. Sarcopenia as a potential cause of chronic hyponatremia in the elderly. Med Hypotheses. Jun 2019;127:46-48. [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa C, Umegaki H, Sugimoto T, et al. Mild hyponatremia is associated with low skeletal muscle mass, physical function impairment, and depressive mood in the elderly. BMC Geriatr. Jan 6 2021;21(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Liamis G, Mitrogianni Z, Liberopoulos EN, Tsimihodimos V, Elisaf M. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with hyponatremia. Intern Med. 2007;46(11):685-90. [CrossRef]

- Solomon R. The relationship between disorders of K+ and Mg+ homeostasis. Semin Nephrol. Sep 1987;7(3):253-62.

- Cohen R, Fernie G, Roshan Fekr A. Fluid Intake Monitoring Systems for the Elderly: A Review of the Literature. Nutrients. Jun 19 2021;13(6). [CrossRef]

- Verbalis JG. Managing hyponatremia in patients with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. J Hosp Med. Jul-Aug 2010;5 Suppl 3:S18-26. [CrossRef]

- Mo Y, Zhou Y, Chan H, Evans C, Maddocks M. The association between sedentary behaviour and sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. Dec 20 2023;23(1):877. [CrossRef]

- Costanti-Nascimento AC B-AL, Bragança-Jardim E, Pereira WO, Camara NOS, Amano MT. Physical exercise as a friend not a foe in acute kidney diseases through immune system modulation. Front Immunol. 2023;14(octo 20). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O, Smith ML. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front Public Health. 2020;8:231. [CrossRef]

- Chesser AK, Keene Woods N, Smothers K, Rogers N. Health Literacy and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. Jan-Dec 2016;2:2333721416630492. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).