1. Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2, also known as COVID-19 expanded in late 2019 in China. The World Health Organization (WHO) labeled it a worldwide pandemic on March 11, 2020, as it was rapidly transmitted to other countries [

1]. In Kazakhstan, the number of cases reported by WHO has reached over 1.5 million people, with over 19000 deaths by the 24th March of 2024 [

2] Statistics of cases and deaths are informative, but there are knowledge gaps in the COVID-19 research topic. One of the major questions is the correlation between the antibody titers and level of protection from the reinfection. The durability of immune responses following infections, as well as the kinetics of immunological antibody production are not well-defined yet. Antibody level dynamics and durability provide valuable information as it is a key factor in developing immunity and preventing reinfection. Antibody data may be used to estimate the percentage of the people that is at risk of reinfection [

3]. According to WHO, as of November 26, 2023, over 12 million people have been vaccinated with at least one dose in Kazakhstan.

IgM antibody is among the first antibodies to emerge in response to a new infection, being a marker for either exposure to a certain disease but decrease as the infection resolves [

4]. IgG plays a more significant role in the first two to three weeks after an infection and forming long-term immune memory, which can last for several months or years [

5]. Increased IgG antibody levels signify a history of illness or vaccination and imply some level of COVID-19 immunity [

6].

Since the early phases of the pandemic one of the critical questions to clarify was the duration of immune protection. Initial data suggested that that immunity from a COVID-19 infection can last at least 8 months [

7], with a significant proportion of people retaining antibodies for up to a year [

8]. Other immune system components, such as memory B cells and T cells, may also contribute to lasting immunity even if antibody levels decline [

9]. While antibodies from previous infections provide some protection, the strength and duration of protection can vary depending on the strain of COVID-19. Some variants (e.g., Delta and Omicron) show partial immune escape, reducing antibody effectiveness but still generally retaining some level of protection against severe disease. Vaccine-induced antibodies can last for several months, with booster doses further extending antibody presence and enhancing immune response. Although antibody levels can decline after several months, the immune system retains a memory response. While waning antibody levels may increase susceptibility to mild or moderate reinfections, severe cases are less common due to cellular immunity. Studies show that reinfections tend to be milder in most cases, especially among vaccinated individuals. Differences in antibodies levels have been associated with age, linked to immunological memory or with a lower capacity to establish a strong defense against new antigenic attacks [

10]. The rise in comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity might be another explanation [

11]. It has also been reported a lower sero-prevalence in men than in women [

12].

This study will complement other studies already started that are investigating in different populations the prevalence of defined categories indicating previous COVID-19 exposure or vaccination and seroconversion in Kazakhstan. The aim of this longitudinal study is to understand the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 IgG over time alongside demographic and clinical factors. The objectives are to provide information regarding quantitative characteristics of IgG after previous infection considering participants’ clinical and demographic profiles among healthcare workers, and to identify factors affecting the changes in IgG antibody levels over time, including demographic characteristics, clinical features of COVID-19 infection, vaccination status, and occupational factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This prospective cohort study covers the adult population in Kazakhstan from November 2022 to September 2023. Participants 18 and older 18 were recruited among healthcare workers from University Medical Center (UMC) who have had COVID-19. The study was entirely voluntary and anonymous to participate in. Participants were informed of the characteristics of the study and after signing informed consent donated a blood sample, responded to a questionnaire and provided authorization to access their medical record. The exclusion criteria were: people with a life expectancy of less than 1 year; pregnant or breastfeeding women; any clinical condition or event that in the opinion of doctors or nurses may substantially increase the risk associated with study participation or compromise the study's scientific objectives and prospective follow-up, or that would make it unsafe for participants to provide blood samples; anticipated difficulty in being able to participate in the 6-month follow-up; no symptoms of a respiratory infection at the moment of recruitment (persistent, cough, nasal congestion, sore throat, fever).

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study exploited several quantitative data collection methods: clinical data, blood sample analysis for IgG and IgM specific antibodies related to COVID-19 and survey obtained in 2 moments of time, baseline and follow up. The baseline self-administered questionnaire comprised several sections: socio-demographic information, lifestyle questions, COVID-19, and vaccination history. Time from last infection and last vaccine was chosen as the latest date from all the dates of infection and vaccination history reported. Participants provided a blood sample for COVID-19 specific IgM and IgG antibodies and one tube for serum storage. 2 blood tubes were necessary for this analysis (a total of 18 mL of vein blood). All manipulations concerning blood collection will be conducted by trained healthcare personnel of UMC. Basic clinical information was obtained from Hospital Information Systems (HIS) medical records. Participants provided their identification, which was coded for any further analysis, and allowed to contact them for a follow-up visit after 6 months to provide a second blood test to count COVID-19 specific IgM/IgG.

Determination of IgG antibodies to the S-protein of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) in blood serum by enzyme immunoassay (ELISA). As it was recommended by the manufacturer, the antibodies level higher than 1.1 IU /ml was considered positive [

13].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The possible impact of the different variables of interest on IgG dynamics between baseline and follow up period will be estimated by the interaction between those variables and time analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA. The dynamic relationship between the antibody levels changes and sociodemographic or clinical factors was assessed by repeated measures ANOVA. It is a statistical method that measures the effect of two independent variables as “treatment” (in this case, socio-demographic or clinical factor) and time (from baseline to follow up) [

14]. Effect of “treatment” (any independent factor) assesses the differences across the groups of treatment regardless of time. Effect of time assesses the difference at two time points regardless of the treatment effect. The interaction between treatment and time shows that one independent variable's effect on a dependent variable’s change based on the level of another independent variable.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 18 (StataCorp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

2.4. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by Nazarbayev University Institutional Research Ethics Committee (NU IREC 571/12052022 on 20/06/2022) and University Medical Center (UMC 2023/001-006 on 15/6/2023).

3. Results

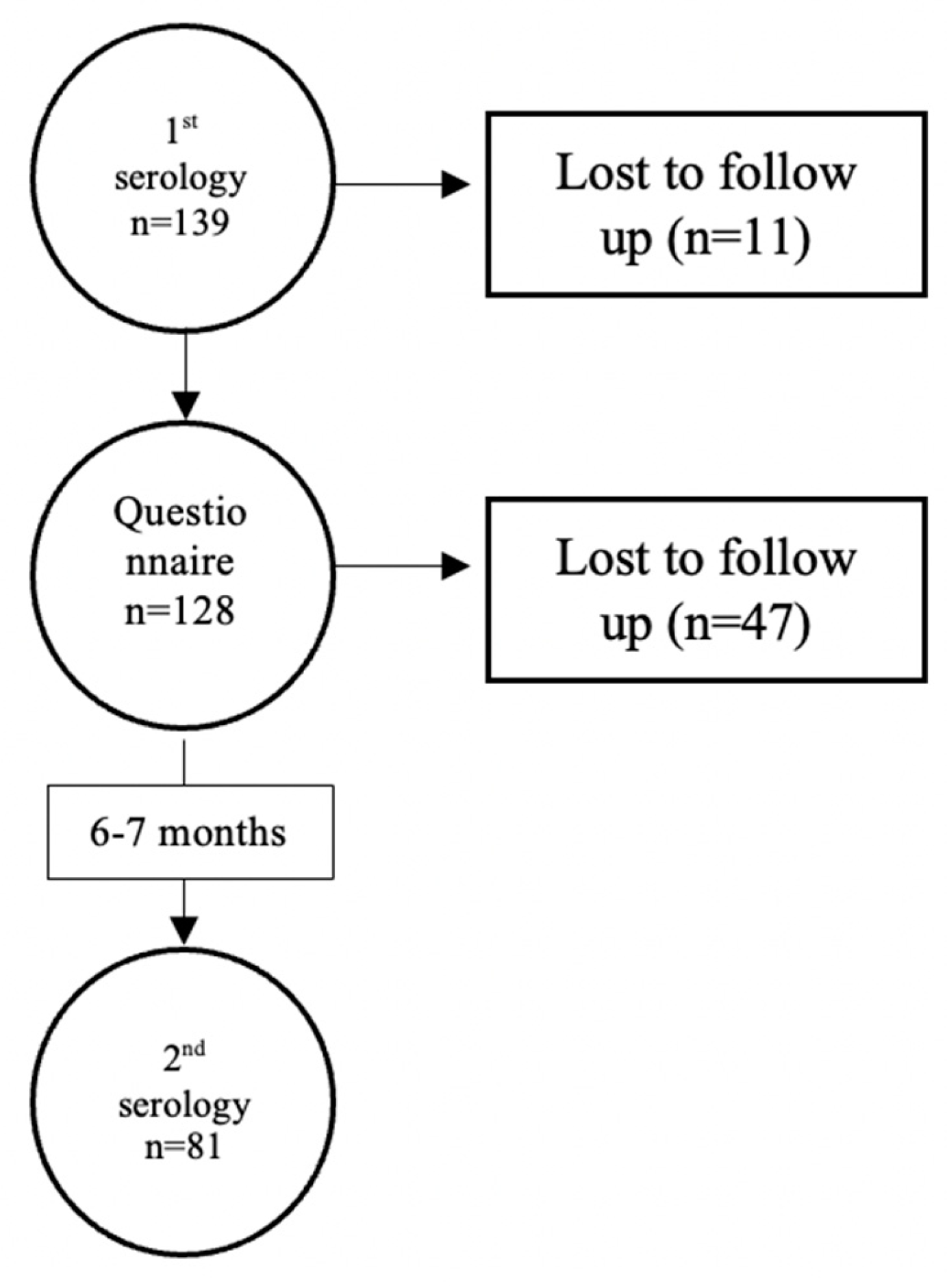

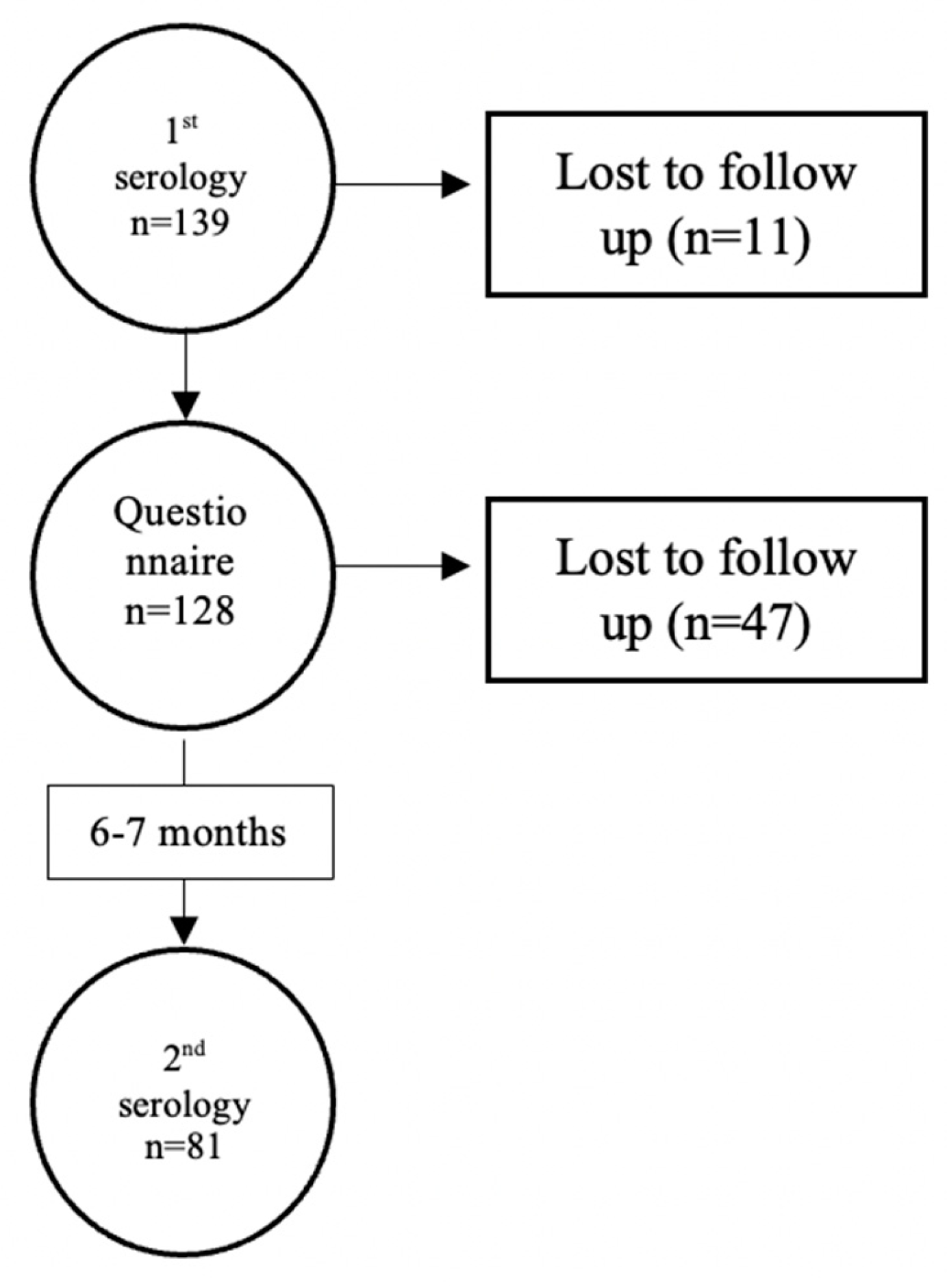

The flowchart of the study is shown at Figure 1. Out of 139 participants who provided their blood, 128 completed the questionnaire and 81 of them had measurements of antibodies both at baseline and follow up for the second blood collection.

Table 1 reports the main characteristics of the sample analyzed. In

Supplementary Table S1 there is a description of other comorbidities also reported by participants in the study

Table 2 reports the frequency of positive IgM antibodies, which typically develop within 1-3 weeks of infection and peak around 2-3 weeks after symptom onset, were positive in 4% of cases, both at baseline and follow up.

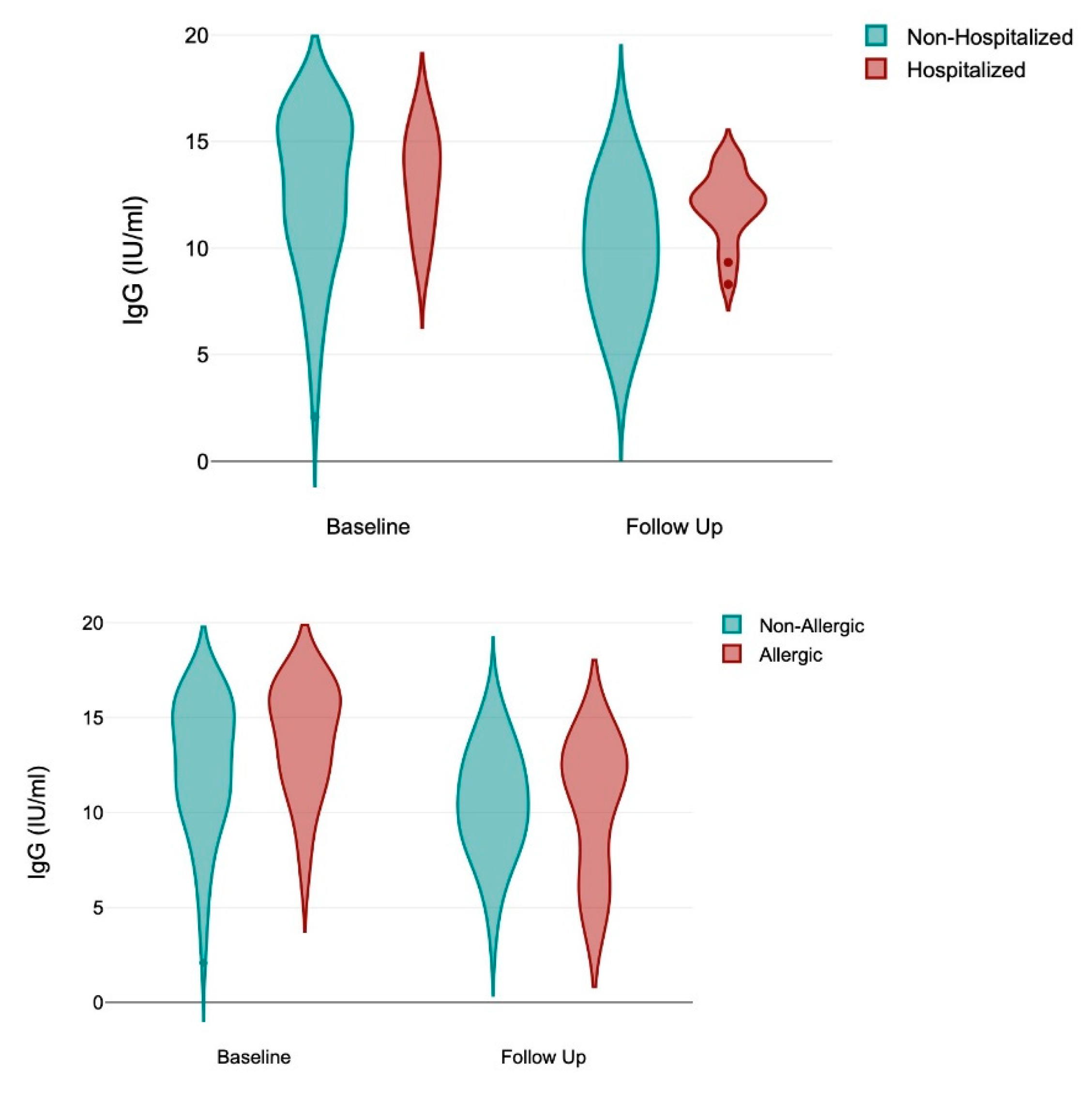

There was a significant decrease in IgG between baseline and follow up (12.95±3.304; 10.49±3.044; p < 0.0001). IgG antibodies, which are often associated with long-term immunity, persisting for several months, and with detectable levels for at least 6-12 months in most individuals, showed differences associated with exposure to SARS-CoV-2 antigens, either natural (hospitalization, ICU admission, positive IgM) as well as from immunization (number of vaccines, time since last vaccine). Allergy appeared with significant effect to elicit higher IgG levels.

Given the large number of participants with no data at follow up,

Supplementary Table S2 reports the mean values of IgG at baseline among those with and without data at follow up showing no differences in these groups.

Table 4 shows the results of a two-way repeated measures ANOVA to determine the effects of treatment, time, and their interaction on baseline and follow-up IgG levels among study participants. The change in IgG over time is different depending on the presence of these variables: allergy is significant (F = 4.69: p = 0.0337), while BMI and having a previous COVID-19 hospitalization were marginally significant (F = 2.99; p = 0.0882 and F = 3.18; p = 0.0794). In

Table 5 a multivariable analysis including the 3 variables the final model rent that hospitalization remained statistically significant (F = 7.23; p = 0.009) while allergy become only marginally significant (F = 2.99; p = 0.089) as well as the interaction between hospitalization, allergy and time (F = 2.89; p = 0.095). The R Squared of this model was 0.77, the adjusted R-squared was 0.52, and Huynh-Feldt epsilon was 1.0536 (p = 0.0214).

Given the Huynh-Feldt epsilon (

Table 5) close to 1 and a significant p-value, the results indicate a statistically significant effect without needing strong adjustments for sphericity.

Figure 2.

Violin graphs representing IgG at baseline and follow up for participants with allergy and hospitalization.

Figure 2.

Violin graphs representing IgG at baseline and follow up for participants with allergy and hospitalization.

4. Discussion

The findings of this longitudinal study indicate that anti-spike (anti-S) SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies remain detectable in 100% of participants for more than 12 months. The persistence of IgG antibodies over time has been previously described in studies where the follow-up period was 6–8 months. Still, studies have shown that humoral immunity persists for more than 12 months after the onset of symptoms. It is an important finding, as more than 30% of the sample here analyzed had the last vaccine more than 12 months ago, and 65% had the last registered COVID-19 infection more than 12 months ago. Also noteworthy is the decline in the mean IgG levels over time in this population, consistent with the previously reported biological rationale [

15]. The natural waning of antibody responses after first exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or vaccination is most likely the cause of this decline in IgG levels.

A second finding of this work is the presence of 4% cases with positive IgM at baseline and follow-up. This finding indicates that SARS-CoV-2 continues to circulate at the community level, but causes asymptomatic infections, mostly due to the hybrid immunity obtained both by vaccination and previous infections that prevent severe cases. The low number of participants who tested positive for IgM antibodies impeded the analysis of the possible characteristics of participants who tested positive for IgM, making subgroup analyses statistically underpowered compromising the validity and generalizability of these analyses. Despite these limitations, recognizing the presence of IgM antibodies in a subset of participants remains important for understanding the dynamics of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further studies with larger and more representative samples could explore the factors contributing to asymptomatic infection among IgM-positive cases.

A third finding of our study is the identification of two variables showing in the ANOVA repeated measures analysis interaction with time, reflecting significant differences between groups, and over time. In two-way ANOVA repeated measures, the interaction of these variables and time (treatment#time) determines whether the effect of one independent factor on the exposure variable (IgG levels in this case) varies with time. In our case, allergy demonstrated a significant independent interaction with time (p = 0.0337) as well as hospitalization in the multivariable model (p = 0.009), implying the significant effect that allergy and a previous hospitalization have on IgG level changes over time. Our results did not find interactions with time for any of the other variables included in this analysis that either consider individual characteristics (sex, age, occupation, BMI, ethnicity, allergy, or other comorbidities) or with variables related to antigenic exposure to COVID-19, either natural (Time since infection, number of infections, IgM at baseline or at follow up) or by vaccination (Time since vaccination, number of vaccines, or type of vaccine).

In this study, allergy appeared as a relevant variable associated with higher IgG titers as well as having an interaction with time in explaining their reduction. COVID-19 is a complex clinical syndrome. SARS-CoV-2 is originally a respiratory illness but curses also with a substantial inflammatory response with pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that stimulate a systemic inflammatory response. Allergic (including atopic) and other hypersensitivity disorders are inappropriate or exaggerated immune reactions to foreign antigens. Although the precise mechanisms are unknown, allergic conditions confer a greater risk of susceptibility to COVID-19 and worse clinical outcomes [

16] but also there is increasing evidence of the role of COVID-19 in increasing the incidence of allergic conditions [

17] and a strong association with long-COVID [

18,

19]. Additional research on this interaction may yield important information about disease susceptibility.

Furthermore, we found an association between hospitalization and changes in IgG levels. Previous findings found the significant association between severity of COVID-19 infection and increased IgG levels [

20]. In our case, we found a strong association between SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers in participants who had to be hospitalized [

21]. Severity of the previous infection remains a robust predictor of higher immune response even after more than 12 months of follow up.

Hybrid immunity benefits both the breadth of the antibody mediated response [

22] and produces greater total and neutralizing anti-S titers than natural infection or vaccination alone [

23]. Our study both supports and builds upon prior findings, as we show that SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies wane in SARS-CoV-2 infected people over time, but IgG were detectable in all our participants. What is the real attributable effect of post-infection or vaccination cannot be determined with our data [

24].

There are a few limitations in the study. This includes a small sample size (81 participants in follow-up), and missing data from the follow-up phase (47 people lost). Data was self-reported, including data from vaccination or previous infections. Participants were healthcare workers, who may have a different exposure profile to SARS-CoV_2 than the general population. This study cannot determine what may be the effect of possible previous asymptomatic infections before recruitment may have elicited higher IgG levels in infected persons. We had only 2 times measurements separated by a median of 8.4 months, a period considered usual for IgG decay. Differences due to the specific variants causing infections may be associated with differences in the immunological responses here identified. Delta was predominant roughly from mid-2021 to late 2021, while Omicron emerged in November 2021 and became predominant from late 2021 through 2022 with various sub-variants. In 2022, Delta had largely waned in prevalence since Omicron's emergence. The effect of specific types of vaccines is difficult to estimate as participants received a quite heterogeneous combination of vaccines [

25]. The first vaccine that was available in Kazakhstan was Sputnik V in 2021, but later many other vaccines were available. Participants reported a significant diversity of types of vaccines they received, including mRNA vaccines. The small number of cases and great diversity in vaccines and schedule of vaccination impede to analysis of the effect of vaccines. To address these limitations and offer a more thorough understanding of immune responses and disease outcomes, larger cohorts for future research are necessary [

26].

The strengths of the study include the longitudinal design of our study that offers important new information about the dynamics of IgG levels among medical professionals over time. We were able to identify subtle alterations in immunity by longitudinally monitoring IgG levels, which has improved our comprehension of immunological responses in work environments.

The dynamic relationship between the antibody level changes and sociodemographic or clinical factors was assessed by repeated measures ANOVA. It is a simple and easy-to-interpret method to analyze measurements taken from the same participants across time points. It provides straightforward F-tests for within-subject factors (e.g., time), making it easy to assess whether there are significant differences, in this case, in IgG level between baseline and follow-up. Because it accounts for within-subject correlations by modeling each subject as their won control, repeated measures ANOVA effectively reduces error variance due to individual differences, leading to greater statistical power to detect differences between time points. Corrections in the analysis, such as the Huynh-Feldt, provide robust estimates for violations of the sphericity assumption. This is a critical issue because ANOVA assumes sphericity, meaning homogeneity of variances of differences and normally distributed residuals. Although sphericity is less concerned with 2-time points, normality still matters. Another limitation is that repeated measures ANOVA is not well-suited to handle continuous covariates, so we used categorical variables here. Repeated measures ANOVA is designed primarily for comparisons of means across time points, but not individual variation in change rates, but this was not the objective of this work.

5. Conclusions

This work provides insight into the dynamics of immune responses in medical professionals after a prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our findings illustrate that although antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 of participants in the study exhibit a noteworthy decline in IgG, they retain noticeable positivity for anti-SARS-CoV-2 (S) antibodies, reflecting a sustained antibody-mediated humoral immune response among the cohort for long period, more than 12 months and that these antibodies could potentially contribute to milder reinfections. Our study cannot determine the possible effect of either reinfections or vaccination to enhance their ability to humoral immunity against SARS-CoV-2. Allergy and previous hospitalizations are associated with IgG dynamics over time. IgM levels were not included in the analysis because of their transient nature and limited applicability for public health interventions; however, the fact that they are present in a subset of participants indicates that immune activity is still ongoing, indicating the need for more research. Problems with sample size and missing data highlight the need for larger, diverse cohorts and more thorough data collection techniques in future research projects, which will be required to determine whether antibody levels elicited following natural infection or induced by vaccines could be long-lasting to sustain protective immunity.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Other comorbidities: number of cases, IgG at baseline and follow up, and F and p values of two-way Anova interaction with time. Table S2.

Table 2S. Mean values of IgG at baseline among those with and without data at follow up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y., K.S., T.K., S.Z., A.S.S. methodology, A.Y., A.G., A.S.S ; formal analysis, A.Y., A.S.S.; investigation, K.S., T.K., K.N.; data curation, A.Y., K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y., A.S.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S., T.K., K.N., A.G., S.Z., A.A., M.T.; supervision, A.S.S.; funding acquisition, A.A., A.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nazarbayev University (grant # NU 021220CRP0822).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Nazarbayev University Institutional Research Ethics Committee (NU IREC 571/12052022 on 20/06/2022) and University Medical Center (UMC 2023/001-006 on 15/6/2023).provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Di Gennaro, F., Pizzol, D., Marotta, C., Antunes, M., Racalbuto, V., Veronese, N., & Smıth, L. (2020). Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) Current status and Future Perspectives: A Narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2690. [CrossRef]

- WHO COVID-19 dashboard. (2024, April). WHO. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?m49=001&n=c.

- Metcalf, C. J. E., Farrar, J., Cutts, F., Basta, N. E., Graham, A. L., Lessler, J., Ferguson, N., Burke, D. S., & Grenfell, B. T. (2016). Use of serological surveys to generate key insights into the changing global landscape of infectious disease. Lancet, 388(10045), 728–730. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H. W., & Cavacini, L. A. (2010). Structure and function of immunoglobulins. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology/Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology/the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 125(2), S41–S52. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A., Henriques, A. R., Queirós, P., Rodrigues, J. F., Mendonça, N., Rodrigues, A. M., Canhão, H., De Sousa, G., Antúnes, F., & Guimarães, M. (2023b). Persistence of IgG COVID-19 antibodies: A longitudinal analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- De Greef, J., Scohy, A., Zech, F., Aboubakar, F., Pilette, C., Gérard, L., Pothen, L., Yıldız, H., Belkhir, L., & Yombi, J. C. (2021). Determinants of IgG antibodies kinetics after severe and critical COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology, 93(9), 5416–5424. [CrossRef]

- Choe PG, Kim KH, Kang CK, Suh HJ, Kang E, Lee SY, et al. Antibody responses 8 months after asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:928–31. [CrossRef]

- Feng C, Shi J, Fan Q, Wang Y, Huang H, Chen F, et al. Protective humoral and cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 persist up to 1 year after recovery. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:4984. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H., Rha, MS., Sa, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell memory is sustained in COVID-19 convalescent patients for 10 months with successful development of stem cell-like memory T cells. Nat Commun 12, 4043 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Costa, V., Racine-Brzostek, S., Acker, K. P., Yee, J., Chen, Z., Karbaschi, M., Zuk, R., Rand, S., Sukhu, A., Klasse, P. J., Cushing, M. M., Chadburn, A., & Zhao, Z. (2021). Association of age with SARS-COV-2 antibody response. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e214302. [CrossRef]

- Grifoni A, Alonzi T, Alter G, Noonan DM, Landay AL, Albini A, Goletti D. Impact of aging on immunity in the context of COVID-19, HIV, and tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 2023 May 24;14:1146704. [CrossRef]

- Kulimbet, M., Saliev, T., Алимбекoва, Г., Ospanova, D., Tobzhanova, K., Tanabayeva, D., Zhussupov, B., & Fakhradiyev, I. (2023). Study of seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Kazakhstan. Epidemiology and Infection, 151. [CrossRef]

- https://www.kdlolymp.kz/services/opredelenie-summarnyh-antitel-k-koronavirusu-sars-cov-2-covid-19.

- Langenberg, B., Helm, J. L., & Mayer, A. (2020). Repeated Measures ANOVA with Latent Variables to Analyze Interindividual Differences in Contrasts. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 57(1), 2–19. [CrossRef]

- Luo H, Camilleri D, Garitaonandia I, Djumanov D, Chen T, Lorch U, Täubel J, Wang D. Kinetics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody levels and potential influential factors in subjects with COVID-19: A 11-month follow-up study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021 Dec;101(4):115537. [CrossRef]

- Movsisyan, M., Truzyan, N., Kasparova, I. et al. Tracking the evolution of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and long-term humoral immunity within 2 years after COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep 14, 13417 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yang JM, Koh HY, Moon SY, Yoo IK, Ha EK, You S, Kim SY, Yon DK, Lee SW. Allergic disorders and susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19: A nationwide cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Oct;146(4):790-798. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., Lee, M., Kim, M., et al. Incident allergic diseases in post-COVID-19 condition: multinational cohort studies from South Korea, Japan and the UK. Nature Communications. [CrossRef]

- Wolff D, Drewitz KP, Ulrich A, Siegels D, Deckert S, Sprenger AA, Kuper PR, Schmitt J, Munblit D, Apfelbacher C. Allergic diseases as risk factors for Long-COVID symptoms: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023 Nov;53(11):1162-1176. [CrossRef]

- Dobaño, C., Ramírez-Morros, A., Alonso, S., Rubio, R., Ruiz-Olalla, G., Vidal-Alaball, J., Macià, D., Catalina, Q. M., Vidal, M., Casanovas, A. F., De La Torre, E. P., Barrios, D., Jiménez, A., Zanoncello, J., Melero, N. R., Carolis, C., Izquierdo, L., Aguilar, R., Moncunill, G., & Ruiz-Comellas, A. (2022). Sustained seropositivity up to 20.5 months after COVID-19. BMC Medicine, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H. et al. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer and the severity of COVID-19. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 55, 1094–1100 (2022).

- Olmstead AD, Nikiforuk AM, Schwartz S, Márquez AC, Valadbeigy T, Flores E, Saran M, Goldfarb DM, Hayden A, Masud S, Russell SL, Prystajecky N, Jassem AN, Morshed M, Sekirov I. Characterizing Longitudinal Antibody Responses in Recovered Individuals Following COVID-19 Infection and Single-Dose Vaccination: A Prospective Cohort Study. Viruses. 2022 Oct 31;14(11):2416. [CrossRef]

- Bates T.A., McBride S.K., Leier H.C., Guzman G., Lyski Z.L., Schoen D., Winders B., Lee J.-Y., Lee D.X., Messer W.B., et al. Vaccination before or after SARS-CoV-2 Infection Leads to Robust Humoral Response and Antibodies That Effectively Neutralize Variants. Sci. Immunol. 2022;7:eabn8014. [CrossRef]

- Movsisyan, M., Truzyan, N., Kasparova, I. et al. Tracking the evolution of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and long-term humoral immunity within 2 years after COVID-19 infection. Sci Rep 14, 13417 (2024). [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Forecasting Team. Past SARS-CoV-2 infection protection against re-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, Volume 401, Issue 10379, 833 - 842.

- Li, C., Ding, Y., Wu, X., Hong, L., Zhou, Z., Xie, Y., Li, T., Wu, J., Lu, F., Li, F., Mao, M., Lin, L., Guo, H., Yue, S., Wang, F., Yan, P., Hu, Y., Wang, Z., Yu, J.,Yang, X. (2021). Twelve-month specific IgG response to SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain among COVID-19 convalescent plasma donors in Wuhan. Nature Communications, 12(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).