Abstract : (1) Background: Healthcare workers (HCWs) are a well-known risk group for coronavirus infections with increased working hours in a potentially infectious environment. We evaluated both IgG and Neutralizing antibody levels, with IgG avidity index and persistence among health workers. (2) Methods: 1001 HCWs were tested for both IgG and Neutralizing antibodies. IgG avidity testing and one-year follow-up testing were done on selected HCWSs. (3) Results: COVID-19 IgG antibody levels were high among 299 (94.62%) HCWs with a history of COVID-19 infection (p <0.0001) compared with 479 (69.92%) HCWs who were not infected with COVID-19 during the first and second wave. A total of 899 (89.81%) HCWs had more than 50% neutralizing antibodies while the remaining 102 (10.19%) HCWs had less than 50% of Neutralizing antibodies. The avidity index was maintained at almost 40% (Gray zone). Both antibody levels were found markedly increased after one year when compared to initial results. (4) Conclusions: Healthcare workers are at a 2.29-fold higher risk of infection; Two folds higher IgG levels in HCWs involved in COVID-19 duty and their persistence for a longer time than in other groups signifies IgG antibody role in the prevention of severe disease in HCWs involved in Covid-19 patient care.

1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic posed the greatest global public health challenge in a century. The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) brought with it the rapid development of both molecular and serologic assays for identifying COVID-19 infections. As the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded, interest has grown in antibody testing as a way to measure how far the infection has spread and to identify individuals who may be immune [

1]. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are a well-known risk group for coronavirus infections, with increased working hours in a potentially infectious environment [

2,

3].

Despite more than 76 million people being infected worldwide and widespread ongoing transmissions, re-infections with SARS-CoV-2 have been increasingly reported, occurring mostly after mild or asymptomatic primary infection, which suggests immunity against re-infection [

4]. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection provides some immunity against re-infection in most people [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Few studies disclosed previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 might not guarantee total immunity in all cases [

10]. In addition, small-scale reports suggest that neutralizing antibodies may be associated with protection against infection. The neutralizing antibody is likely to be a key correlate of protection for COVID-19 and data on kinetics of virus-neutralizing antibody responses are needed.

Patients with COVID-19 infection develop detectable SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody responses with some having detectable antibodies at the end of the 1st week of illness, and almost all having neutralizing antibodies after 4 weeks of illness. The majority of clinical studies and validations of commercial tests have been performed, but only a few studies have investigated the antibody responses in pauci-symptomatic or asymptomatic persons [

12,

13]. We evaluated both IgG and Neutralizing antibodies including the avidity of IgG against SARS-CoV-2 whole cell antigen among health workers and the persistence of these protective antibody levels after one year period.

2. Materials and Methods

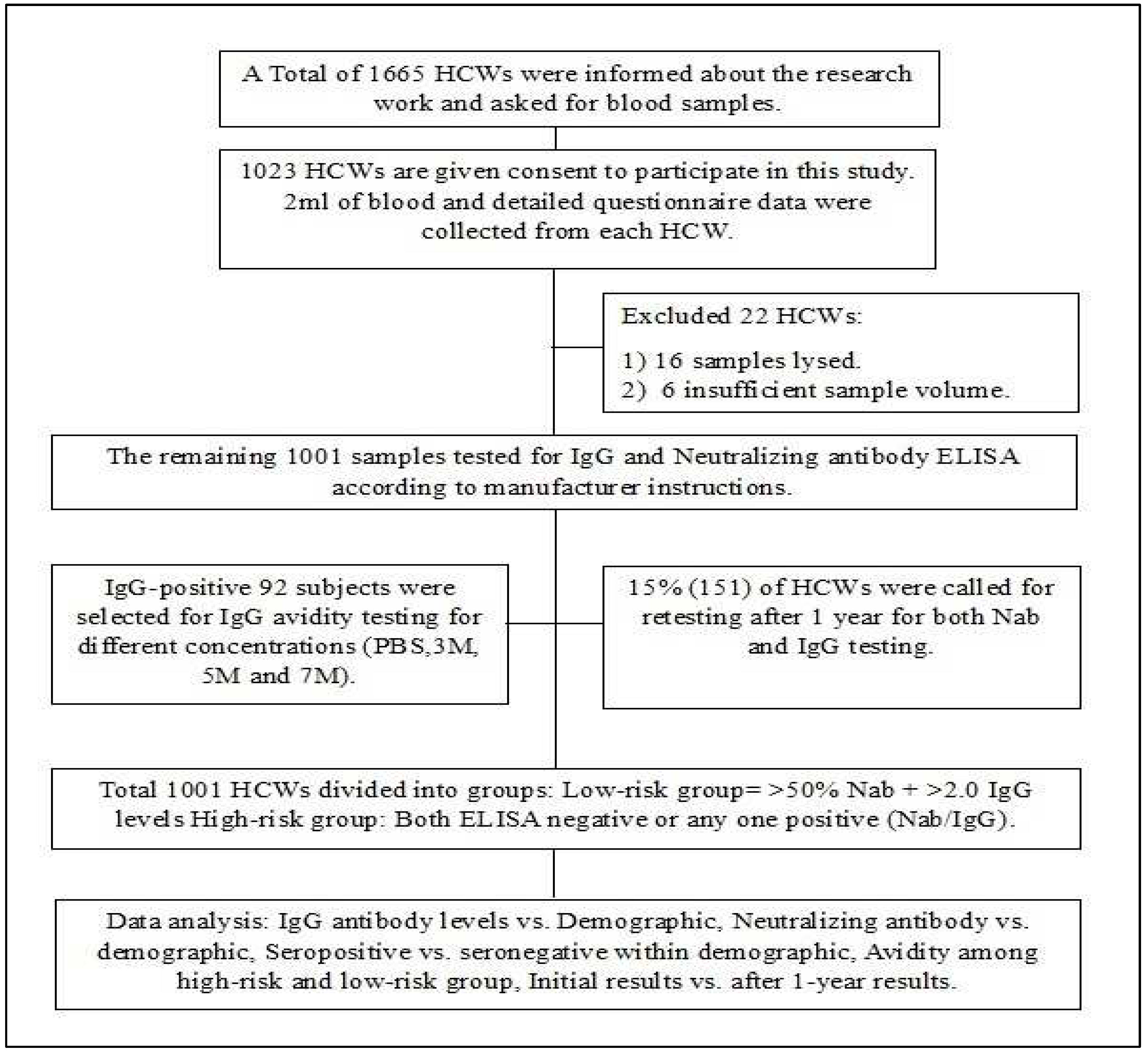

This study was conducted at the state-level virus research and diagnostic laboratory, SVIMS, Tirupati. A total of 1001 healthcare workers were included in the study from July 2021 to September 2021. 2 ml of blood was collected from each subject. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and the study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (IEC-1176). The study flow chart is presented in

Figure 1.

2.1. Demographic Data Collection

A cloud-based data collection tool was developed (Appsheet online software) to collect details for clinical and demographic data using a questionnaire. During follow-up visits, HCWs were asked for Covid positivity and severity of disease (supplymentary

Table S1)

2.2. Serology Assay

We used a commercially available kit (COVID KAWACH IgG MICROLISA antibody ELISA kit and COVID NEUTRALIZING ANTIBODY MICROLISA manufactured by J. Mitra & Co. Pvt) to examine the level of IgG against the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and Neutralization antibody levels in the serum samples. We followed the manufacturer’s instructions as recommended. IgG index value of more than 2.0 was considered positive. Neutrazation inhibition was calculated using the formula; Percentage inhibition = (1-Sample O.D/Negative control O.D) x 100%. Percentage Inhibition of 50% and above was considered positive for neutralizing antibody test.

2.3. Avidity testing

The avidity index of IgG antibodies was performed using a COVID KAWACH IgG MICROLISA ELISA kit with urea at 3M, 5M, and 7M concentrations [

14]. In brief, sera from selected subjects were incubated with three different concentrations of urea (3M, 5M, and 7M) along with PBS buffer. PBS results were considered as controls against which the results of the ELISA with three different concentrations of Urea were compared. Avidity index (AI) was calculated by using the following formula.

The sample was considered to contain IgG of “low-avidity” at AI ≤ 40%, “high-avidity” at AI ≥ 50%; “Gray zone” at AI 40–50%, adapted from Correa VA et al. [

15].

2.4. One-year follow-up

Of the 1001 subjects 15% (151) HCWs were retested for persistence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG and SARCOV-2 neutralizing antibodies after 1 year using the kits mentioned above.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data were arranged in Excel spreadsheets; The Normality of the data was assessed by the Shapiro Wilk test and visually by QQ plot. Based on involvement in COVID-19 patient care, data were divided into high and low-risk groups; HCWs who have Neutralising antibody percentage of more than 50% with an IgG index value of more than 2.0 were considered a low-risk group whereas, HCWs who have negative for both neutralizing antibody and IgG antibody or any one test is positive were considered as a high-risk group. The comparison between groups was done using the Wilcoxon singed-rank test, and Mann-Whitney U test to assess the changes in the antibody levels as appropriate. Two-tailed parametric t-test means with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% was used, P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using Jeffreys’s Amazing Statistics Program (JASP) version 0.16.2.

3. Results

A total of 1001 healthcare workers of SVIMS University, Tirupati were enrolled in the study of which 417 (41.66%) were males and females 584 (58.34%) were females. The most common age group was 21-30 years covering 37.36% of total study subjects. 94 HCWs had taken the Covaxin vaccine and 881 HCWs took the Covishield vaccine. Since the number of COVID-19 vaccinated individuals was much less, statistical analysis about the type of vaccine taken was not done.

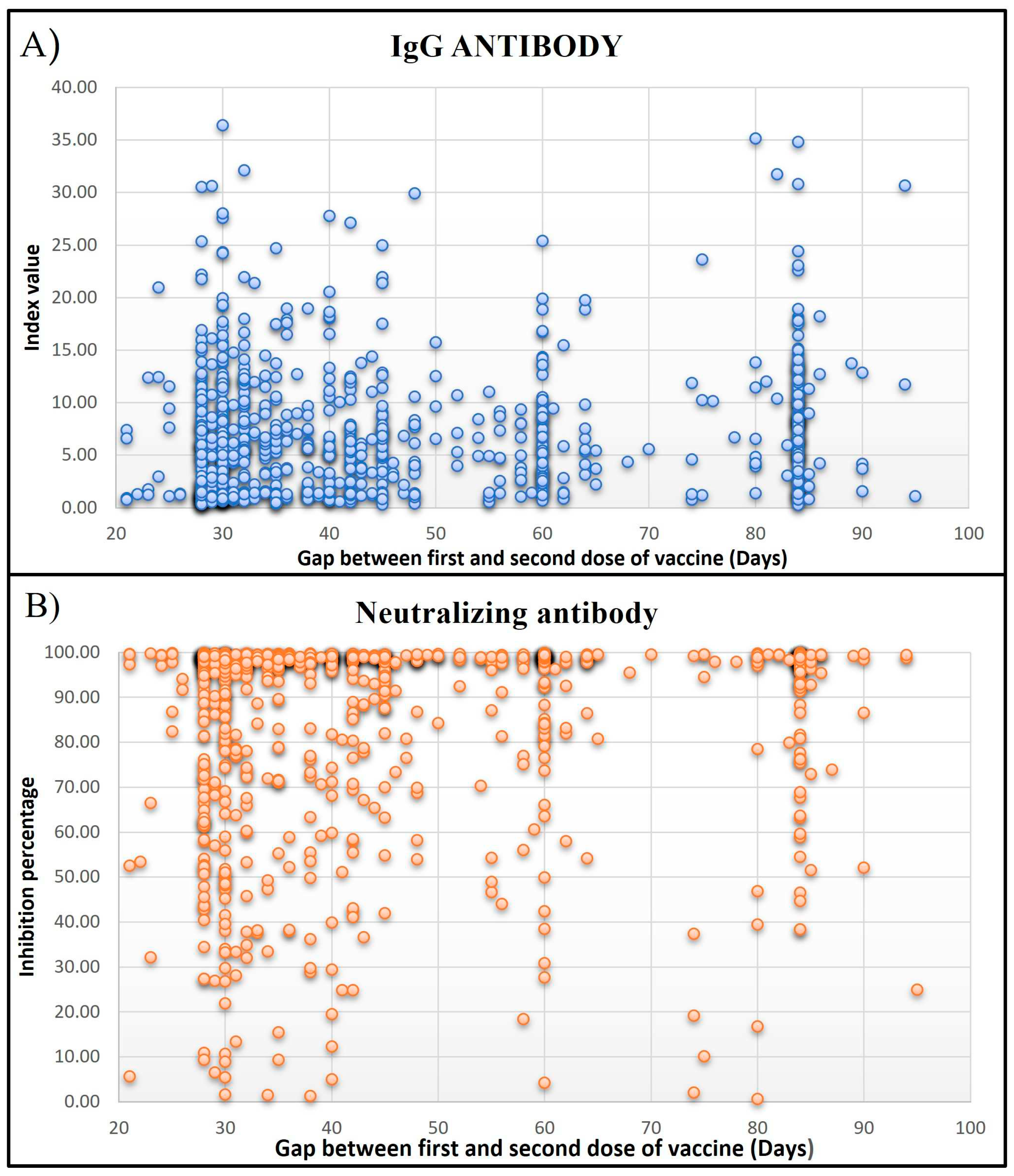

Of the 1001 HCWs, 316 (31.56%) workers had a history of COVID-19 infection. Among these asymptomatic to Mild infections comprised 75.63%, and Moderate to severe infections were 24.37%. The most common symptoms in HCWs infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection included Fever, Headache, Cold, Sore throat, and Myalgia. Five hundred and seventy-six (57.54%) HCWs were actively involved in COVID-19 patient care or sample handling while 425 (42.46%) were not involved in any COVID-19-related duty. Majority of healthcare workers were Doctors (16.88%), followed by Nurses (15.68%), Lab technicians (13.18%), Researchers (1.3%), Multipurpose workers (2.6%), supportive staff (10.1%), administrative staff (12.78%) and others (27.47%). The infection rate was observed to be 2.29-fold higher in HCWs involved in COVID-19 patient care (22%) as compared to HCWs with no Exposure history (9.6%), and it was statistically significant (p>0.0001). When compared to the gap between the first and second dose of vaccination, Subjects who had taken the second dose after 28 to 45 days of the first dose had higher levels of both types of antibodies (

Figure 2).

3.1. Serum IgG antibody levels in HCWs

Of the total 975 individuals were vaccinated and 26 were unvaccinated. Of the 975 vaccinated HCWs, a total of 764 (78.35%) had detectable IgG antibodies whereas 14 of 26(53.84%) nonvaccinated HCWs had detectable IgG antibodies. Of the 975 vaccinated HCWs, 211(21.64%) did not have detectable IgG antibodies in their serum whereas 12(46.15%) non-vaccinated HCWs did not have detectable IgG antibodies.

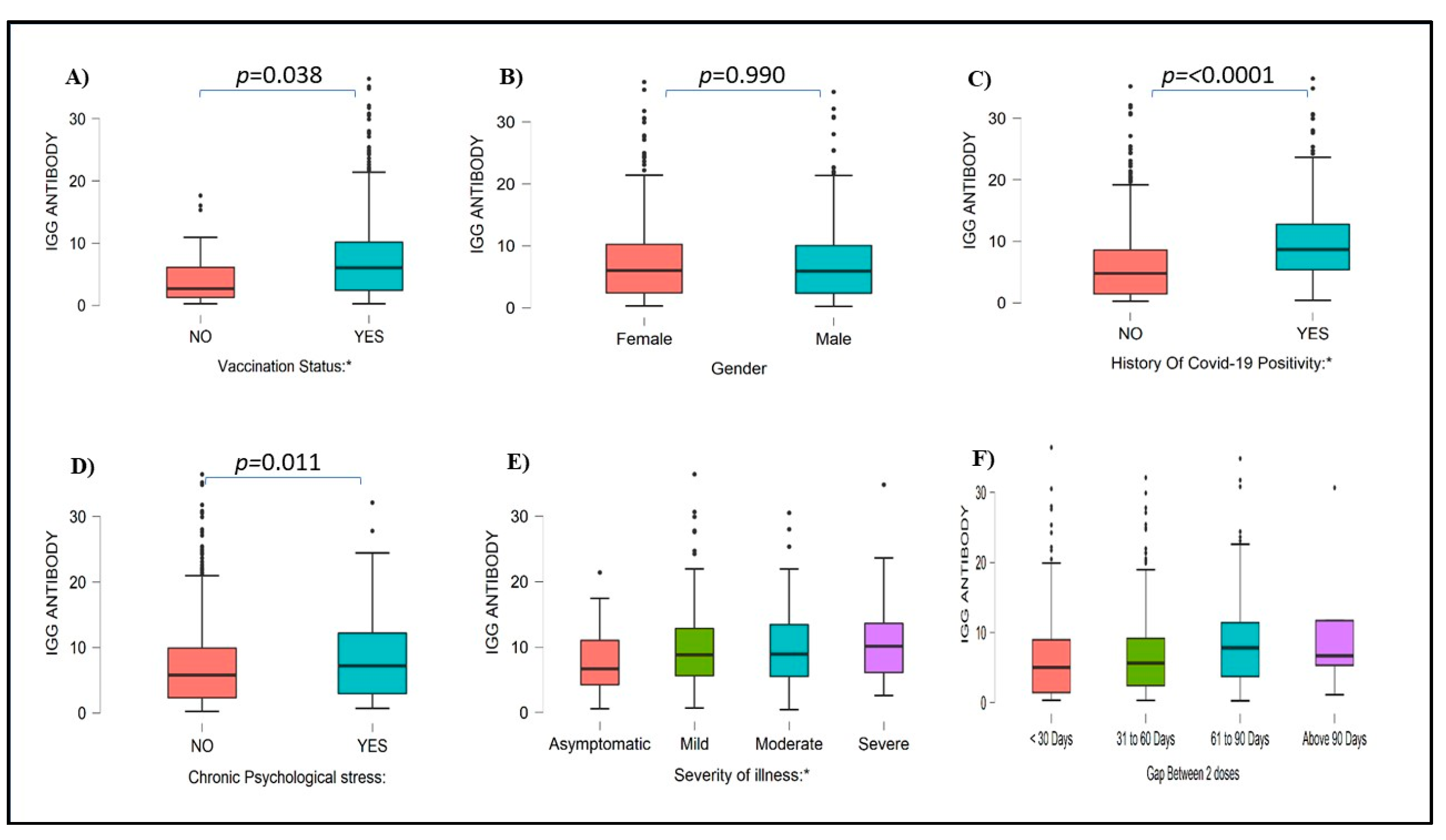

A higher number of females were positive for COVID-19 IgG antibody (45.2 %) as compared to males 32.4%. Of the 316, 299 (299/316) HCWs with a history of COVID-19 infection had higher IgG antibody levels (94.62%) (p <0.0001) as compared with 479 of 685 (69.92%) HCWs who were not infected with COVID-19 during the first and second wave (

Figure 3). Among 576 HCWs who were actively involved in COVID-19 duty, 79.52% of HCWs had detectable IgG antibody levels, whereas 21.48% of HCWs did not have IgG antibodies Similarly, 75.29% of HCWs who were not involved in any COVID-19 duty had IgG antibodies, and 24.71% of HCWs did not have IgG antibodies. Serum IgG index value compared with different blood groups, Rh Status, Sleeping pattern, and other health-related and environmental factors was mentioned in Supplementary Figures S1 to S3.

3.2. Serum Neutralizing Antibodies Levels in HCWs

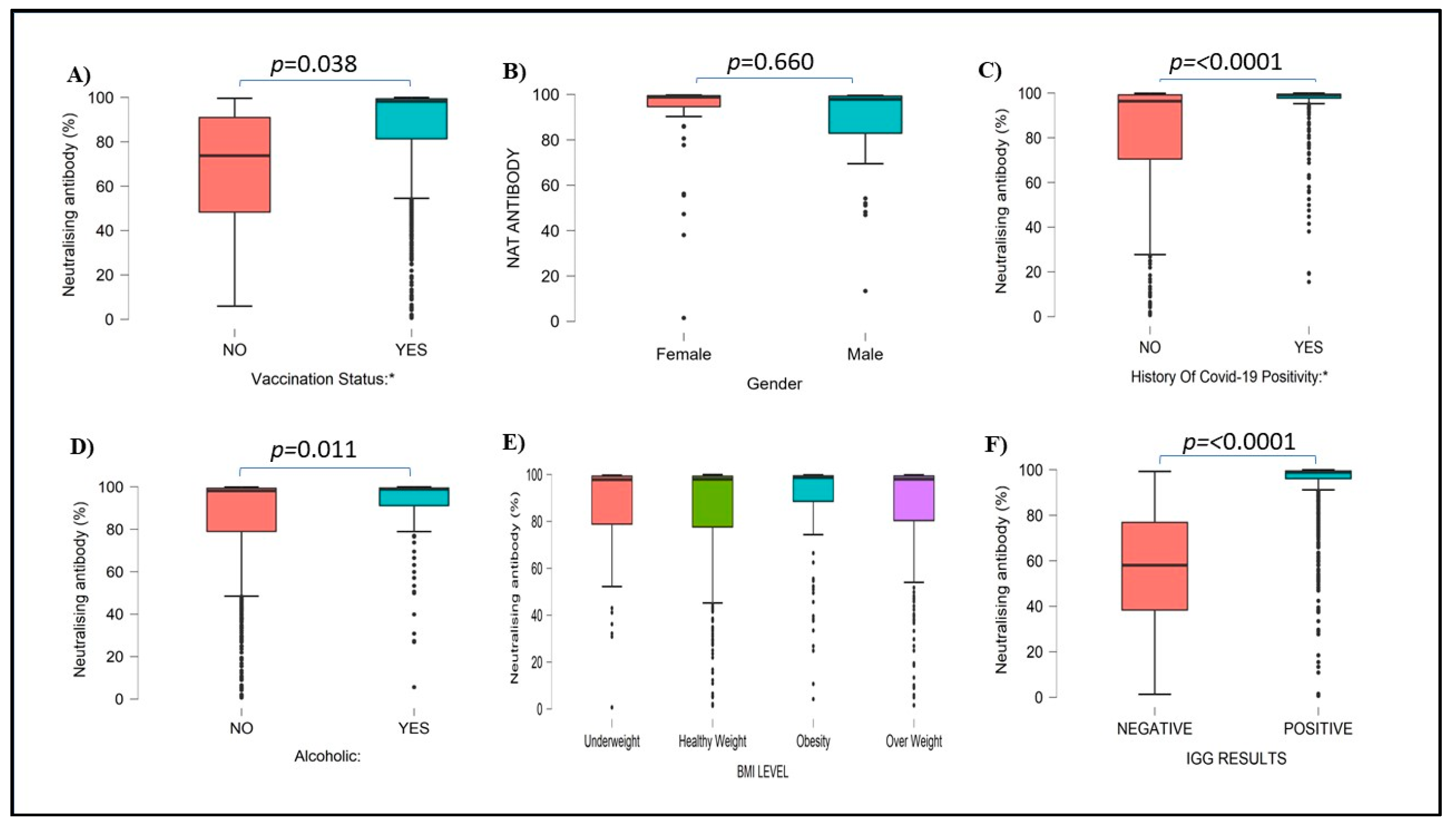

A total of 899 (89.81%) HCWs had more than 50% neutralizing antibodies, while the remaining 102 (10.19%) HCWs had less than 50% of Neutralizing antibodies. Of the vaccinated HCWs 98% had more than 50% neutralizing antibodies. A total of 52.3 % of females and 37.4% of males had neutralizing antibodies. A total of 880 healthcare vaccinated workers and 19 non-vaccinated HCWs had neutralizing antibodies. Neutralizing antibodies were not detected in 95 of vaccinated and 7 of nonvaccinated HCWs, the difference was statistically significant. Vaccinated individuals had significantly high neutralizing antibodies (p<0.001) compared to nonvaccinated HCWs. A total of 79 vaccinated and 7 nonvaccinated workers did not have either type of antibodies.

Like IgG antibodies, neutralizing antibodies were low in previously COVID-19-positive individuals (34.26%) in comparison to COVID-19-negative individuals (65.74%). There was a significant difference in neutralizing antibody levels (p<0.0001) in previously covid-positive versus covid-negative HCWs (

Figure 4). The levels of both IgG and Neutralizing antibodies were significantly high in HCWs with a history of COVID-19 infections as compared to subjects without a history of such infection (p<0.0001). Serum Neutralization inhibition percentages compared with different blood groups, Rh Status, Sleeping pattern, and other health-related and environmental factors were mentioned in supplementary figures S4 to S6.

3.3. High-Risk vs. Low-Risk

HCWs having 50% or below neutralizing antibody levels with below 2.0 index value IgG antibody levels were considered a High-risk group (239 (23.87%)) whereas HCWs with 50% and above neutralizing antibody levels and 2.0 index value IgG antibody levels were considered as Low-risk group (762 (76.12%)).

Most of the HCWs in the age group 31 to 40 years were Seropositive (low-risk group) (p=0.026). Based on occupations; Doctors (p<0.0001), nurses (p=0.005), lab technicians (p=0.031), and supportive staff (p=0.0002) were seropositive and others (Administrative staff, researchers, others, etc..) were seronegative (high-risk group). A comparison between Demographic information within the risk groups is shown in

Table 1.

When compared with other factors like Smoking, alcohol consumption, sleeping patterns, and stress showed no significant difference between high-risk and low-risk groups, data shown in

Table 2. We found that the majority of HCWs with a History of COVID-19 positivity are in the Low-risk group (p<0.0001).

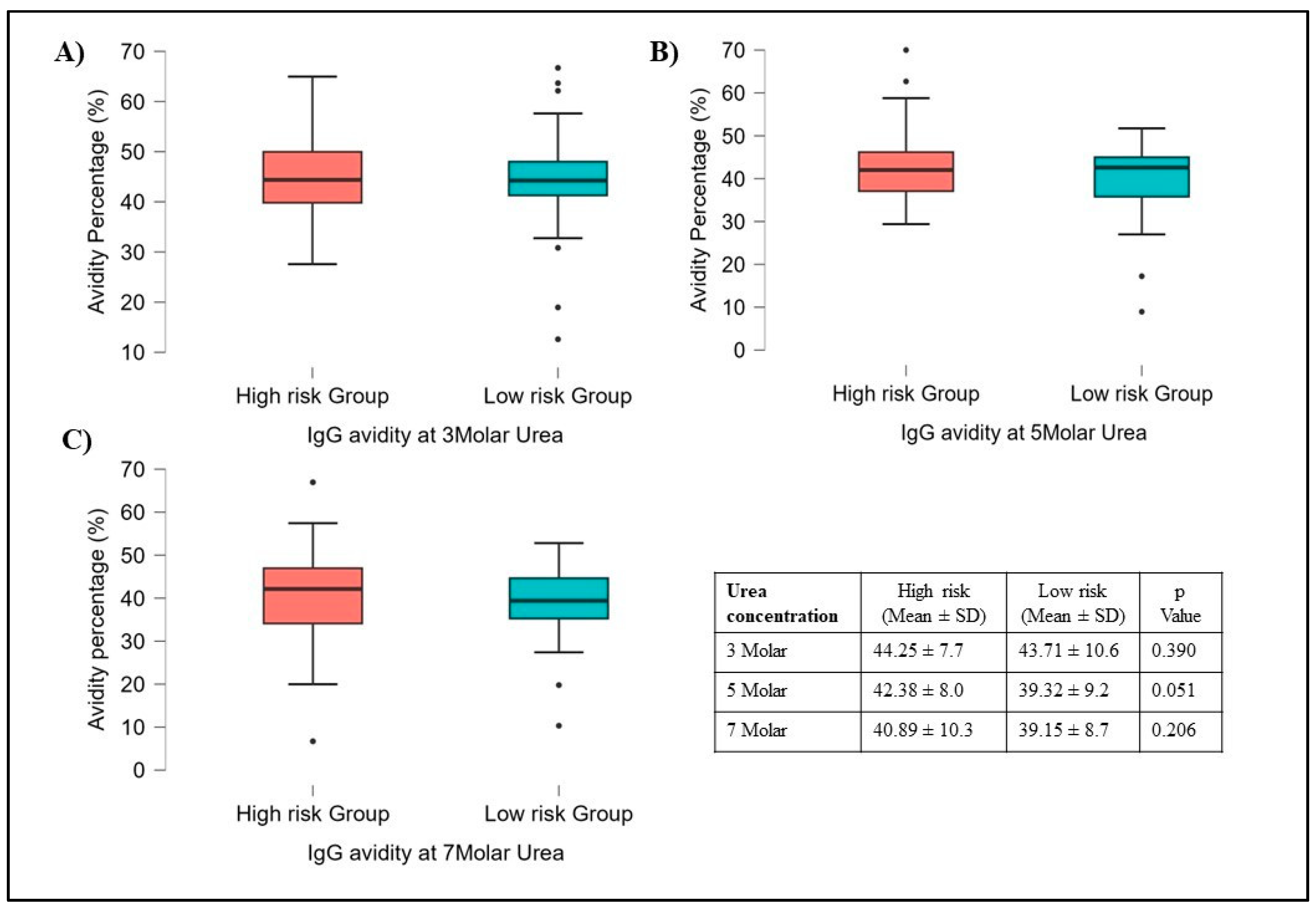

3.4. Avidity Results

Out of 1001 subjects, sera of 92 subjects were selected for avidity testing. Instead of testing with a Standard concentration of 7M urea, increasing concentrations of urea such as 3M, 5M, and 7M with PBS as a Control were used. The results showed no variation in avidity at different concentrations compared to avidity testing with PBS solution.

The avidity did not vary significantly concerning different Gender types, Smoking habits, Alcoholics, involvement in COVID-19 duty, Family size, etc. However, among risk and high-risk groups, the avidity was slightly high in High-risk groups compared to the Low-risk group but it was not statistically significant (

Figure 5). Interestingly the Avidity index was maintained at almost 40% (Gray zone) at all three concentrations (3M, 5M & 7M) of Urea in Both risk groups. High IgG Avidity was observed in HCWs who were vaccinated, had a history of COVID-19 infection, and were involved in COVID-19-related duty. We found significant differences between people who had a second dose of vaccination after 60 days of the first dose compared to less than 60 days. The avidity data comparison with COVID-19 positivity, Neutralization inhibition (>50%), and Gap between the first dose and second dose was shown in supplementary

Figures S7 to S9.

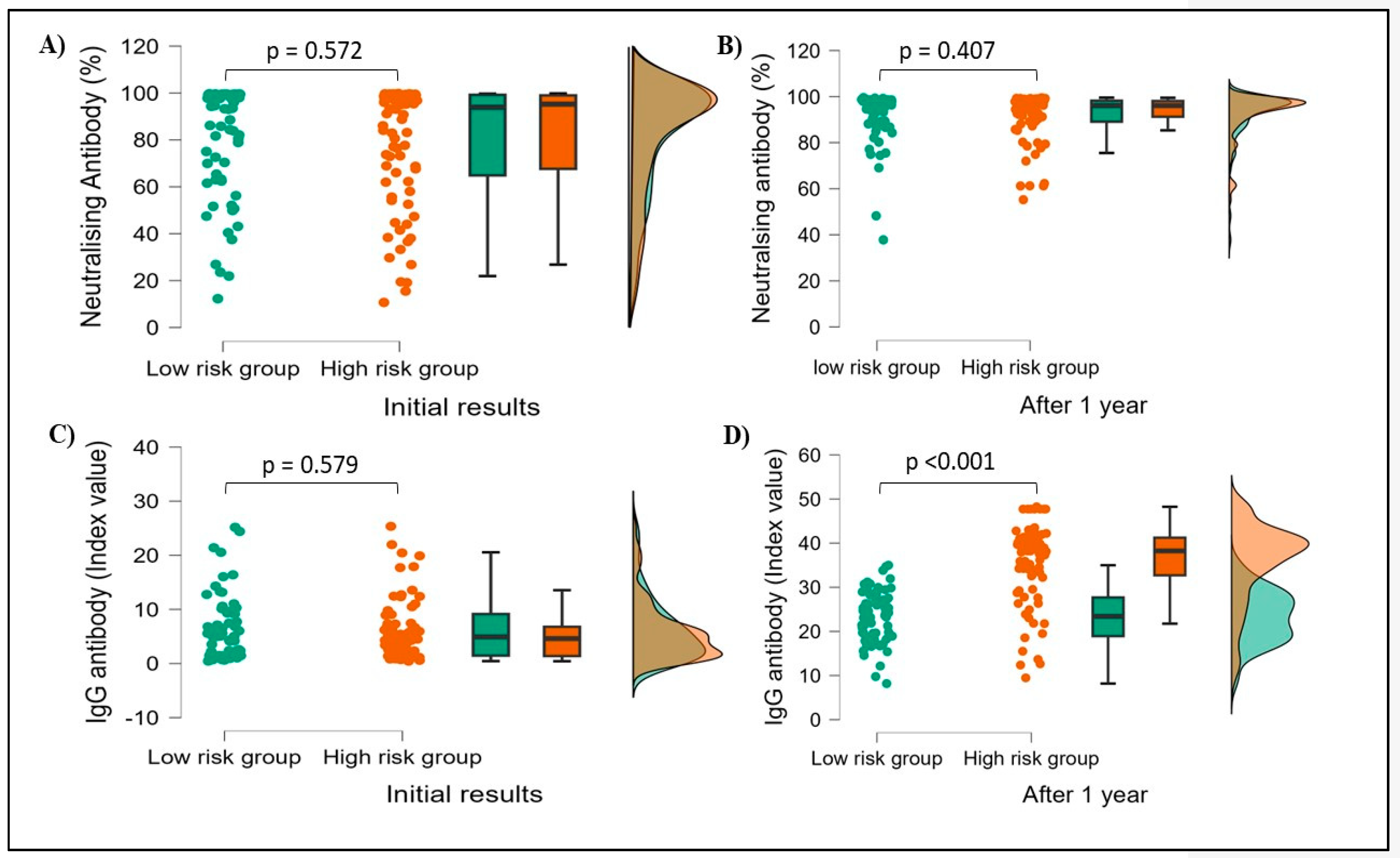

3.5. Initial results vs. 1-year follow-up results

Due to financial constraints, a total of 15% of subjects (151) were tested for both Neutralizing and IgG antibody levels after 1 year from the initial testing. Among 151 subjects, males were 81 and females were 70. 71 HCWs had confirmed previous history of COVID-19 infection whereas 80 HCWs had no such history. Both antibody levels were found markedly increased after one year when compared to initial results and the difference was statistically significant, with neutralizing antibodies p<0.001 (81.08 ± 24.1 vs 92.55 ± 8.9) and IgG antibodies p<0.001 (5.99 ± 5.6 vs 30.30 ±9.8). When compared with the history of COVID-19 infection, there were no significant differences in both neutralizing and IgG antibody levels after one year of initial testing.

Neutralizing antibody levels did not vary significantly results in both groups (low-risk p=0.572, high-risk p=0.407), while IgG antibody levels were found to increase significantly in the High-risk group (p<0.001) compared to the low-risk group (p=0.579) after 1 year (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, many countries experienced large numbers of hospitalizations, overwhelming their healthcare systems, and resulting in a lack of supply of personal protective equipment including N95 masks. Many HCWs were infected with COVID-19 and several of them succumbed [

16]. Several countries reported that the HCWs testing positive by RT-PCR ranged from 6% to 38% [

16,

17,

18]. Most of the infections among HCWs were community-acquired [

2].

Several studies indicated that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was associated with a significantly reduced risk of SARS-Cov-2 reinfection among HCWs up to 7 months and more after primary infection [

19,

20]. Similarly in our study reinfection after primary infection was noted only in 5 HCWs.HCWs treating SARS-CoV-2 infected patients were reported to be at 11.6-fold higher risk of developing COVID-19 infection compared to the General community [

3]. Our findings revealed that the seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and Neutralizing antibodies was higher in females in comparison to males (IgG: 45.2% vs. 32.4%, Neutralizing antibody; 52.3% vs. 37.4%). However, in contradiction to our study, several studies have reported seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to be higher in males compared to females [

21,

22,

23]. Few studies also reported higher seroprevalence in females compared to males which is in concordance with our study [

24].

Both IgG and Neutralizing antibody levels were higher in the age group of 21 to 40 years, representing young and middle-aged HCWs (

Table 1). The young aged HCWs were more active in health care services about the care of the COVID-19 patients and had an efficient immune system, and fewer co-morbidities compared to the older age group. A similar study from India reported that younger age group HCWs had higher zero-prevalence of COVID-19 compared to older age group [

23].

Almost 98% of HCWs enrolled in our study had completed their two doses of vaccination. Our doctors (p<0.0001), Nurses (p=0.0054), Lab technicians (p=0.031), and supportive staff (p=0.0002) were significantly seropositive. This can be justified by the long duty hours of duty in which they are exposed to COVID-19 patients/ samples for longer duration than other HCWs. A similar study showed that Seroprevalence is higher in physicians compared to other HCWs [

25].

HCWs staying with family (p=0.007) had higher antibody levels in comparison to students staying in hostels or rented rooms (p=0.01). These results suggest that household contacts may play a significant role in the development of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Few studies suggested, that reducing contact in households immediately is key to preventing onward transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [

26].

Compared to Vegetarians, Non-vegetarians were more in the low-risk group suggesting a higher level of protection. This may be due to the availability of high concentrations of Zinc and other compounds in meat and fish products, thus playing a role in antiviral immunity [

27,

28].

In the literature, a higher risk (up to 11.6-fold increased risk) of SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported among HCWs, compared to HCWs not involved actively in COVID-19 patient care or the general actively involved in COVID-19 patient care community [

3,

23]. In agreement with this, we found that the infection rate was 2.29-fold higher in HCWs involved in COVID-19 patient care (22%) than in HCWs with no such Exposure (9.6%), and it was statistically significant (p>0.0001).

The avidity of an antibody is considered an interaction between the antibody and the antigen and is a measure of the overall strength of the antibodies [

29]. The presence of low avidity IgG to RBD indicates a risk of developing COVID-19 in a severe form [

30]. In our study, high-risk group HCWs had high IgG avidity compared to the low-risk group, and IgG avidity percentage was well maintained at 40% or above at different urea concentrations (

Figure 5), which may be due to continuous exposure to COVID-19 patients with new SARS-CoV-2 variants or Vaccination. A study reported that high levels of IgG antibody and IgG avidity were significantly associated with high levels of neutralizing antibody titers [

31]. In our study also high IgG avidity was observed in subjects with high levels of neutralizing antibodies. We could not find any gender-related avidity differences in our study, thus matching previous studies in the literature [

32,

33].

A study conducted in the eastern part of India reported 6 months of persistence of RBD spike IgG antibodies after vaccination [

34]. In our study, both Neutralizing and IgG antibody levels were significantly (p<0.001) increased after 1 year. Our study corroborates several studies conducted on the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels after several months of SARS-CoV-2 Infection [

35,

36,

37]. When compared to disease severity; asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals were reported to have higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (69.0 to 91.4%) after 8 months of infection [

38].

When comparing risk and low-risk groups, among 151 subjects there were no changes in neutralizing antibody levels, but IgG antibody levels were found to be markedly increased among the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (p<0.001) (

Figure 4). This may be due to inapparent SARS-CoV-2 infection which went undiagnosed in a large number of HCWs involved in patient care. In our study overall 5.1 folds of IgG levels increased after 1 year compared to initial results. Among risk groups, 6.3 folds of IgG levels increased in the High-risk group but only 3.6 folds in the low-risk group, which means the high-risk group HCWs had high levels of protective antibodies and IgG antibodies persisted longer in them than the other group. Several studies showed concordance with our study, wherein they reported almost 5.0 to 7.0 times more rise in IgG antibody levels in HCWs who were involved in COVID-19 patient care [

2,

3,

39].

Despite the availability of vaccines against SAR-CoV-2, the pandemic has not been brought under control. New VOCs have rapidly outcompeted the preceding strain and spreading globally. Several studies found that neutralizing antibodies formed with earlier SARS-CoV-2 lineages are capable of neutralizing later emerged VOCs [

40]. It is evidence that IgG plays a major role in neutralization activity in blood and other body tissues with different SARS-CoV-2 lineages [

41]. During our study period, major lineages belonged to Delta (98.5%), Alpha (0.5%), and others (1.0%) from India [

42]. The Neutralizing and IgG antibodies which are formed during natural infection with delta and other sub-lineages of SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs with COVId-19 related duty summed up the immunity and develop cross protection against new emerging VOCs of SARS-Cov-2.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that several factors increase the SARS-CoV-2 IgG and Neutralizing antibody seropositivity. Healthcare workers who are involved in COVID-19 patient care are at a 2.29-fold higher risk of infection compared to those who are not actively involved. The IgG avidity is well maintained above 40% among healthcare workers which may be due to continuous exposure to COVID-19 patientsinfected with novel SARS-CoV-2 variants or vaccinations. Two folds higher IgG levels in HCWs involved in COVID-19 duty and their persistence for a longer time than in other groups signifies IgG antibody role in the prevention of severe disease in HCWs involved in COVID-19 patient care.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Table showing Complete HCWS demographic information with Neutralizing and IgG antibody results (both initial and one-year follow-up). Figure S1: Boxplot representing IgG antibody index value comparison in HCWs with the smoking habit (A), Family size (B), Alcoholic (B), and Acute psychological stress (D). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S2: Boxplot representing IgG index value comparison in HCWs with eating habits (E), Environmental factors (F), exercise (G), and Sleeping pattern (G). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S3: Boxplot representing IgG index value comparison in HCWs with different blood groups (I), Rh status (J), BMI level (K), and involved COVID-19-related duty (L). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S4: Boxplot representing Neutralizing antibody percentage comparison in HCWs with Acute psychological stress (A), Alcoholic (B), Chronic Psychological stress (C), and Smoking (D). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S5: Boxplot representing Neutralizing antibody percentage comparison in HCWs with different blood groups (E), Rh Status (F), Vaccination status (G), and severity of illness during COVID-19 infection (H). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S6: Boxplot representing Neutralizing antibody percentage comparison in HCWs with Eating habits (I), Family size (J), Exercise (K), and Environmental factors (L). p-value <0.05 indicates significant. Figure S7: Boxplot representing SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody avidity percentage compared with History of COVID-19 positivity by different graded Urea concentrations A) 3molar urea B) 5molar urea and C) 7 molar urea concentration, p-value calculated by using student t-test. Figure S8: Boxplot representing SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody avidity percentage compared with Neutralization inhibition percentage (>50%) by different Urea concentrations D) 3molar urea E) 5molar urea and F) 7 molar urea concentration, p-value calculated by using student t-test. Figure S9: Boxplot representing SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody avidity percentage compared with gap between the first and second dose of vaccination by different Uera concentrations G) 3molar urea H) 5molar urea and I) 7 molar urea concentration, p-value calculated by using student t-test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-original draft preparation, A.S; writing—review and editing M.N., K.S; methodology, P.P., N.U; supervision A.M, A,V.; project administration; U,K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee (IEC-1176).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge J Mitra & Co pvt limited for providing IgG and Neutralizing antibody ELISA kits for this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Petherick, A. Developing Antibody Tests for SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1101–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maskari, Z.; Al Blushi, A.; Khamis, F.; Al Tai, A.; Al Salmi, I.; Al Harthi, H.; Al Saadi, M.; Al Mughairy, A.; Gutierrez, R.; Al Blushi, Z. Characteristics of Healthcare Workers Infected with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Graham, M.S.; Joshi, A.D.; Guo, C.-G.; Ma, W.; Mehta, R.S.; Warner, E.T.; Sikavi, D.R.; Lo, C.-H.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 among Front-Line Health-Care Workers and the General Community: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e475–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Bhoyar, R.C.; Jain, A.; Srivastava, S.; Upadhayay, R.; Imran, M.; Jolly, B.; Divakar, M.K.; Sharma, D.; Sehgal, P.; et al. Asymptomatic Reinfection in 2 Healthcare Workers From India With Genetically Distinct Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, e2823–e2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.S.; Pritchard, E.; House, T.; Robotham, J.V.; Birrell, P.J.; Bell, I.; Bell, J.I.; Newton, J.N.; Farrar, J.; Diamond, I.; et al. Viral Load in Community SARS-CoV-2 Cases Varies Widely and Temporally 2020, 2020. 10.25.2021 9048.

- Mumoli, N.; Vitale, J.; Mazzone, A. Clinical Immunity in Discharged Medical Patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Lau, J.Y.-N.; Yang, L.; Ma, Z.-G. SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection in Two Patients Who Have Recovered from COVID-19. Precis. Clin. Med. 2020, 3, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousseff, M.; Penot, P.; Gallay, L.; Batisse, D.; Benech, N.; Bouiller, K.; Collarino, R.; Conrad, A.; Slama, D.; Joseph, C.; et al. Clinical Recurrences of COVID-19 Symptoms after Recovery: Viral Relapse, Reinfection or Inflammatory Rebound? J. Infect. 2020, 81, 816–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Threat Assessment Brief: Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: Considerations for Public Health Response. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/threat-assessment-brief-reinfection-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Tillett, R.L.; Sevinsky, J.R.; Hartley, P.D.; Kerwin, H.; Crawford, N.; Gorzalski, A.; Laverdure, C.; Verma, S.C.; Rossetto, C.C.; Jackson, D.; et al. Genomic Evidence for Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: A Case Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addetia, A.; Crawford, K.H.D.; Dingens, A.; Zhu, H.; Roychoudhury, P.; Huang, M.-L.; Jerome, K.R.; Bloom, J.D.; Greninger, A.L. Neutralizing Antibodies Correlate with Protection from SARS-CoV-2 in Humans during a Fishery Vessel Outbreak with a High Attack Rate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e02107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.-X.; Tang, X.-J.; Shi, Q.-L.; Li, Q.; Deng, H.-J.; Yuan, J.; Hu, J.-L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, F.-J.; et al. Clinical and Immunological Assessment of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzelak, L.; Temmam, S.; Planchais, C.; Demeret, C.; Huon, C.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Staropoli, I.; Chazal, M.; Dufloo, J.; Planas, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Serological Analysis of COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients, Pauci-Symptomatic Individuals and Blood Donors 2020, 2020.04.21.20068858.

- Vermont, C.; van den Dobbelsteen, G. Neisseria Meningitidis Serogroup B: Laboratory Correlates of Protection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, V.A.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Portilho, A.I.; Trzewikoswki de Lima, G.; De Gaspari, E. Modified ELISA for Antibody Avidity Evaluation: The Need for Standardization. Biomed. J. 2021, 44, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluytmans-van den Bergh, M.F.Q.; Buiting, A.G.M.; Pas, S.D.; Bentvelsen, R.G.; van den Bijllaardt, W.; van Oudheusden, A.J.G.; van Rijen, M.M.L.; Verweij, J.J.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W. Prevalence and Clinical Presentation of Health Care Workers With Symptoms of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in 2 Dutch Hospitals During an Early Phase of the Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e209673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-García, I.; Martínez de Aramayona López, M.J.; Sáez Vicente, A.; Lobo Abascal, P. SARS-CoV-2 Infection among Healthcare Workers in a Hospital in Madrid, Spain. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, A.J.; Evans, C.; Colton, H.; Ankcorn, M.; Cope, A.; State, A.; Bennett, T.; Giri, P.; de Silva, T.I.; Raza, M. Roll-out of SARS-CoV-2 Testing for Healthcare Workers at a Large NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, March 2020. Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Mal. Transm. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2020, 25, 2000433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, V.J.; Foulkes, S.; Charlett, A.; Atti, A.; Monk, E.J.M.; Simmons, R.; Wellington, E.; Cole, M.J.; Saei, A.; Oguti, B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Rates of Antibody-Positive Compared with Antibody-Negative Health-Care Workers in England: A Large, Multicentre, Prospective Cohort Study (SIREN). Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 397, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, S.F.; Wei, J.; O’Donnell, D.; Stoesser, N.E.; Matthews, P.C.; Howarth, A.; Hatch, S.B.; Marsden, B.D.; Cox, S.; James, T.; et al. The Duration, Dynamics, and Determinants of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Antibody Responses in Individual Healthcare Workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, e699–e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, A.; Nasrullah, S.M.; Tasnim, Z.; Hasan, M.K.; Hasan, M.M. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG Antibodies among Health Care Workers Prior to Vaccine Administration in Europe, the USA and East Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 33, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balou, H.A.; Yaghubi Kalurazi, T.; Joukar, F.; Hassanipour, S.; Shenagari, M.; Khoshsorour, M.; Mansour-Ghanaei, F. High Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)-Specific Antibodies among Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Guilan, Iran. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 2021, 9081491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, M.; Afzalpurkar, S.; Goenka, U.; Das, S.S.; Mukherjee, M.; Jajodia, S.; Shah, B.B.; Patil, V.U.; Rodge, G.; Khan, U.; et al. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 Amongst Health Care Workers in a Tertiary Care Hospital of a Metropolitan City from India. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2020, 68, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, O.; Solanki, B.; Sheth, J.; Makwana, G.; Kadam, M.; Vyas, S.; Shukla, A.; Pethani, J.; Tiwari, H. SARS-CoV2 IgG Antibody: Seroprevalence among Health Care Workers. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trieu, M.-C.; Bansal, A.; Madsen, A.; Zhou, F.; Sævik, M.; Vahokoski, J.; Brokstad, K.A.; Krammer, F.; Tøndel, C.; Mohn, K.G.I.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Responses in Norwegian Health Care Workers After the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Kissling, E.; Valenciano, M.; Dizdar, F.; Blažević, M.; Jogunčić, A.; Palo, M.; Merdrignac, L.; Pebody, R.; Jorgensen, P. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: A Prospective Observational Study in Bosnia and Herzegovina, August–December 2020. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 112, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddir, M.; Brito, A.; Dingeo, G.; Fernandez Del Campo, S.S.; Samouda, H.; La Frano, M.R.; Bohn, T. Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.A.; Obeid, S.; Ahlenstiel, C.; Ahlenstiel, G. The Role of Zinc in Antiviral Immunity. Adv. Nutr. Bethesda Md 2019, 10, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Maroto, C. Are IgG Antibody Avidity Assays Useful in the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases? A Review. Microbios 1996, 87, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Manuylov, V.; Burgasova, O.; Borisova, O.; Smetanina, S.; Vasina, D.; Grigoriev, I.; Kudryashova, A.; Semashko, M.; Cherepovich, B.; Kharchenko, O.; et al. Avidity of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 RBD as a Prognostic Factor for the Severity of COVID-19 Reinfection. Viruses 2022, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.R.; Chakraborty, I.; Yun, C.; Wu, A.H.B.; Lynch, K.L. Kinetics of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Antibody Avidity Maturation and Association with Disease Severity. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, e3095–e3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, W.E.; Trakhimets, O.; Andrade, D.V.; Dambrauskas, N.; Raappana, A.; Jiang, Y.; Houck, J.; Selman, W.; Yang, A.; Vigdorovich, V.; et al. Rapid Decline of Neutralizing Antibodies Is Associated with Decay of IgM in Adults Recovered from Mild COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, D.; Baumgartner, M.; Kimpel, J.; Rössler, A.; Riepler, L.; Bates, K.; Fleischer, V.; von Laer, D.; Borena, W.; Würzner, R. Marked Increase in Avidity of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies 7-8 Months After Infection Is Not Diminished in Old Age. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, G.C.; Subhadra, S.; Turuk, J.; Parai, D.; Rath, S.; Sabat, J.; Rout, U.K.; Kanungo, S.; Choudhary, H.R.; Nanda, R.R.; et al. Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 Infections among BBV-152 (COVAXIN®) and AZD1222 (COVISHIELDTM ) Recipients: Report from the Eastern State of India. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flehmig, B.; Schindler, M.; Ruetalo, N.; Businger, R.; Bayer, M.; Haage, A.; Kirchner, T.; Klingel, K.; Normann, A.; Pridzun, L.; et al. Persisting Neutralizing Activity to SARS-CoV-2 over Months in Sera of COVID-19 Patients. Viruses 2020, 12, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Norddahl, G.L.; Melsted, P.; Gunnarsdottir, K.; Holm, H.; Eythorsson, E.; Arnthorsson, A.O.; Helgason, D.; Bjarnadottir, K.; Ingvarsson, R.F.; et al. Humoral Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Lei, P.; Shen, G.; Yang, C. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2-Specific Antibodies in COVID-19 Patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, P.G.; Kim, K.-H.; Kang, C.K.; Suh, H.J.; Kang, E.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, N.J.; Yi, J.; Park, W.B.; Oh, M. Antibody Responses 8 Months after Asymptomatic or Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahto, M.; Banerjee, A.; Biswas, B.; Kumar, S.; Agarwal, N.; Singh, P.K. Seroprevalence of IgG against SARS-CoV-2 and Its Determinants among Healthcare Workers of a COVID-19 Dedicated Hospital of India. Am. J. Blood Res. 2021, 11, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pauvolid-Corrêa, A.; Caetano, B.C.; Machado, A.B.; Ferreira, M.A.; Valente, N.; Neves, T.K.; Geraldo, K.; Motta, F.; Dos Santos, V.G.V.; Grinsztejn, B.; et al. Sera of Patients Infected by Earlier Lineages of SARS-CoV-2 Are Capable to Neutralize Later Emerged Variants of Concern. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2022, 7, bpac021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Maeda, K.; Matsuda, K.; Takamatsu, Y.; Kinoshita, N.; Kutsuna, S.; Hayashida, T.; Gatanaga, H.; Ohmagari, N.; Oka, S.; et al. Neutralization Activity of IgG Antibody in COVID-19-convalescent Plasma against SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbe, S.; Buckland-Merrett, G. Data, Disease and Diplomacy: GISAID’s Innovative Contribution to Global Health. Glob. Chall. Hoboken NJ 2017, 1, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawana, A.; Teruya, K.; Kirikae, T.; Sekiguchi, J.; Kato, Y.; Kuroda, E.; Horii, K.; Saito, S.; Ohara, H.; Kuratsuji, T.; et al. “Syndromic Surveillance within a Hospital” for the Early Detection of a Nosocomial Outbreak of Acute Respiratory Infection. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 59, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The flow chart of the Study design.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of the Study design.

Figure 2.

IgG and neutralizing antibody levels compared to the gap between the first and second dose of vaccine (Days). (A) IgG antibody levels are mentioned as an index value, and (B) neutralizing antibody levels as inhibition percentages.

Figure 2.

IgG and neutralizing antibody levels compared to the gap between the first and second dose of vaccine (Days). (A) IgG antibody levels are mentioned as an index value, and (B) neutralizing antibody levels as inhibition percentages.

Figure 3.

IgG antibody levels among subjects with vaccination status (A), Gender (B), history of COVID-19 positivity (C), chronic psychological stress (D), Severity of illness (E), and Gap between 2 doses (F). IgG Values are mentioned as index values.

Figure 3.

IgG antibody levels among subjects with vaccination status (A), Gender (B), history of COVID-19 positivity (C), chronic psychological stress (D), Severity of illness (E), and Gap between 2 doses (F). IgG Values are mentioned as index values.

Figure 4.

Neutralising antibody percentages among subjects with vaccination status (A), Gender (B), history of COVID-19 positivity (C), alcoholic (D), BMI level (E), and IgG results (F). Neutralizing antibody values are mentioned in percentages.

Figure 4.

Neutralising antibody percentages among subjects with vaccination status (A), Gender (B), history of COVID-19 positivity (C), alcoholic (D), BMI level (E), and IgG results (F). Neutralizing antibody values are mentioned in percentages.

Figure 5.

Showing Avidity results of 92 subjects, compared within high and low-risk groups. A, B, and C show all samples processed for 3M, 5M, and 7M urea concentrations respectively. There are no differences observed between these two groups for all three different urea concentrations. Student t-tests were used for p-value calculation.

Figure 5.

Showing Avidity results of 92 subjects, compared within high and low-risk groups. A, B, and C show all samples processed for 3M, 5M, and 7M urea concentrations respectively. There are no differences observed between these two groups for all three different urea concentrations. Student t-tests were used for p-value calculation.

Figure 6.

Showing initial and after 1 year Neutralising and IgG antibody results. A& B showing Neutralising antibody percentages at initial and after 1-year results. C & D show IgG index value at the initial and after 1 year respectively. p-value calculated based on student t-test, p-value <0.05 indicates statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Showing initial and after 1 year Neutralising and IgG antibody results. A& B showing Neutralising antibody percentages at initial and after 1-year results. C & D show IgG index value at the initial and after 1 year respectively. p-value calculated based on student t-test, p-value <0.05 indicates statistically significant.

Table 1.

Demographic data among High-risk and low-risk groups compared to general factors and Vaccination. The χ2 test (associations between exposure groups and characteristics) determined the P value by using the Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

Table 1.

Demographic data among High-risk and low-risk groups compared to general factors and Vaccination. The χ2 test (associations between exposure groups and characteristics) determined the P value by using the Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

| Variables |

TOTAL (1001) |

High-risk group (239) |

Low-risk group (762) |

X2

|

P VALUE |

| AGE |

no. (%) |

no. (%) |

no. (%) |

|

|

| 19-20 |

8 (0.80) |

4 (1.67) |

4 (0.52) |

3.028 |

0.0409 |

| 21-30 |

374 (37.36) |

91 (38.08) |

283 (37.14) |

0.06 |

0.397 |

| 31-40 |

297 (29.67) |

59 (24.69) |

238 (31.23) |

3.738 |

0.0266 |

| 41-50 |

187 (18.68) |

47 (19.67) |

140 (18.37) |

0.2 |

0.3273 |

| 51-60 |

130 (12.99) |

37 (15.48) |

93 (12.20) |

1.728 |

0.0944 |

| 61-70 |

5 (0.50) |

1 (0.42) |

4 (0.52) |

0.04 |

0.4193 |

| SEX |

|

|

|

|

|

| MALE |

417 (41.66) |

96 (40.17) |

321 (42.13) |

0.2872 |

0.296 |

| FEMALE |

584 (58.34) |

143 (59.83) |

441 (57.87) |

0.2872 |

0.296 |

| OCCUPATION |

|

|

|

|

|

| DOCTOR |

169 (16.88) |

62 (25.94) |

107 (14.04) |

18.36 |

<0.00001 |

| NURSE |

157 (15.68) |

25 (10.46) |

132 (17.32) |

6.479 |

0.0054 |

| LAB TECHNICIAN |

132 (13.19) |

23 (9.62) |

109 (14.30) |

3.482 |

0.031 |

| RESEARCHERS |

13 (1.30) |

4 (1.67) |

9 (1.18) |

0.3443 |

0.2787 |

| SUPPORTIVE STAFF |

101 (10.09) |

10 (4.18) |

91 (11.94) |

12.07 |

0.0002 |

| ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF |

128 (12.79) |

33 (13.81) |

95 (12.47) |

0.2931 |

0.2941 |

| MULTIPURPOSE WORKERS |

26 (2.60) |

7 (2.93) |

19 (2.49) |

0.1363 |

0.356 |

| OTHERS |

275 (27.47) |

75 (31.38) |

200 (26.25) |

2.407 |

0.0604 |

| VACCINE STATUS |

|

|

|

|

|

| YES |

975 (97.40) |

227 (94.98) |

748 (98.16) |

7.289 |

0.0034 |

| NO |

26 (2.60) |

12 (5.02) |

14 (1.84) |

|

|

| HISTORY OF COVID +VE |

|

|

|

|

|

| YES |

316 (31.57) |

17 (7.11) |

299 (39.24) |

86.92 |

<0.00001 |

| NO |

685 (68.43) |

222 (92.89) |

463 (60.76) |

|

|

| GAP BETWEEN 2 DOSES |

|

|

|

|

|

| <30 |

275 (27.47) |

82 (34.31) |

193 (25.33) |

7.36 |

0.0033 |

| 31-60 |

443 (44.26) |

107 (44.77) |

336 (44.09) |

0.03 |

0.4272 |

| 61-90 |

183 (18.28) |

27 (11.30) |

156 (20.47) |

10.25 |

0.0006 |

| >90 |

8 (0.80) |

2 (0.84) |

6 (0.79) |

0.005 |

0.4702 |

|

SEVERITY OF ILLNESS(after +VE)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MILD |

194 (19.38) |

11 (4.60) |

183 (24.02) |

43.88 |

<0.00001 |

| MODERATE |

52 (5.19) |

4 (1.67) |

48 (6.30) |

7.904 |

0.0024 |

| SEVERE |

25 (2.50) |

0 (0.0) |

25 (3.28) |

8.042 |

0.0022 |

| ASYMPTOMATIC |

45 (4.50) |

2 (0.84) |

43 (5.64) |

9.789 |

0.0008 |

Table 2.

Demographic data among High-risk and low-risk groups compared to Health and Environmental factors. The χ2 test (associations between exposure groups and characteristics) determined the P-value by using the Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

Table 2.

Demographic data among High-risk and low-risk groups compared to Health and Environmental factors. The χ2 test (associations between exposure groups and characteristics) determined the P-value by using the Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

| Variables |

TOTAL (1001) |

High-risk group$$$(239) |

Low-risk group$$$(762) |

X2

|

P VALUE |

| INVOLVED IN COVID-19 DUTY |

no. (%) |

no. (%) |

no. (%) |

|

|

| YES (High-risk group) |

576 (57.54) |

127 (53.14) |

449 (58.92) |

2.493 |

0.05 |

| NO (Low-risk group) |

425 (42.46) |

112 (46.86) |

313 (41.08) |

|

|

| BMI (level) |

|

|

|

|

|

| UNDERWEIGHT (<18.5) |

57 (5.69) |

14 (5.86) |

43 (5.64) |

0.01 |

0.4503 |

| NORMAL WEIGHT (18.5 - 24.9) |

485 (48.48) |

120 (50.21) |

365 (47.90) |

0.388 |

0.2663 |

| OVERWEIGHT (25.0 - 29.9) |

330 (32.97) |

78 (32.64) |

252 (33.07) |

0.01 |

0.4503 |

| OBESITY (>=30) |

129 (12.89) |

27 (11.30) |

102 (13.39) |

0.707 |

0.2002 |

| SMOKING |

|

|

|

|

|

| YES |

18 (1.80) |

5 (2.09) |

13 (1.71) |

0.1535 |

0.3476 |

| NO |

983 (98.20) |

234 (97.91) |

749 (98.29) |

|

|

| ALCOHOL |

|

|

|

|

|

| YES |

98 (9.79) |

18 (7.53) |

80 (10.50) |

1.814 |

0.0891 |

| NO |

903 (90.21) |

221 (92.47) |

682 (89.50) |

|

|

| EXERCISE |

|

|

|

|

|

| DAILY |

384 (38.36) |

96 (40.17) |

288 (37.80) |

0.4329 |

0.255 |

| WEEKLY |

129 (12.89) |

33 (13.81) |

96 (12.60) |

0.2369 |

0.3132 |

| NONE |

488 (48.75) |

110 (46.03) |

378 (49.61) |

0.8361 |

0.1803 |

| SLEEPING HOURS |

|

|

|

|

|

| <7 HOURS |

526 (52.55) |

120 (50.21) |

406 (53.28) |

0.6884 |

0.2034 |

| 7-8 HOURS |

438 (43.76) |

108 (45.19) |

330 (43.31) |

0.2616 |

0.3045 |

| >8 HOURS |

37 (3.70) |

11 (4.60) |

26 (3.41) |

0.7243 |

0.1974 |

| ACUTE PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS |

|

|

|

|

| YES |

139 (13.89) |

33 (13.81) |

106 (13.91) |

0.0016 |

0.4839 |

| NO |

862 (86.11) |

206 (86.19) |

656 (86.09) |

|

|

| CHRONIC PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS |

|

|

|

|

| YES |

122 (12.19) |

25 (10.46) |

97 (12.73) |

0.8755 |

0.1747 |

| NO |

879 (87.81) |

214 (89.54) |

665 (87.27) |

|

|

| EATING HABITS |

|

|

|

|

|

| VEGETARIAN |

118 (11.79) |

37 (15.48) |

81 (10.63) |

4.118 |

0.0212 |

| NON-VEGETARIAN |

883 (88.21) |

202 (84.52) |

681 (89.37) |

|

|

| ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS |

|

|

|

|

|

| RURAL |

38 (3.80) |

9 (3.77) |

29 (3.81) |

0.0008 |

0.4887 |

| URBAN |

963 (96.20) |

230 (96.23) |

733 (96.19) |

|

|

| FAMILY SIZE |

|

|

|

|

|

| SINGLE |

211 (21.08) |

63 (26.36) |

148 (19.42) |

5.263 |

0.0108 |

| NUCLEAR |

785 (78.42) |

174 (72.80) |

611 (80.18) |

5.856 |

0.0077 |

| GAINT FAMILY |

5 (0.50) |

2 (0.84) |

3 (0.39) |

0.7188 |

0.1983 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).